Introduction

Epithelia form intelligent, dynamic barriers between the external environment and an organism's interior. Intercellular cadherin-based adhesions adapt and respond to mechanical forces and cell density, while tight junctions flexibly control diffusion both within the plasma membrane and between adjacent cells. Epithelial integrity and homeostasis are of central importance to survival, and mechanisms have evolved to ensure these processes are maintained during growth and in response to damage. For instance, cell competition surveys the fitness of cells within epithelia and removes the less fit; extrusion or delamination can remove apoptotic or defective cells from the epithelial sheet, and can restore homeostasis when an epithelial layer become too crowded; spindle orientation ensures two-dimensional growth in simple epithelia and controls stratification in complex epithelia; and transition to a mesenchymal phenotype enables active escape from an epithelial layer. This review will discuss these mechanisms and consider how they are subverted in disease.

Introduction

Epithelia extend in size during embryogenesis, self-organize into structures such as tubes or villi, and maintain homeostasis once they have attained their adult dimensions by actively adapting to the environment – a characteristic of intelligent or “smart” materials. Exactly how individual epithelial cells function together as a tissue is of intrinsic scientific interest, and – because most human cancers arise from epithelia – is also of great medical importance. This review considers the multiple mechanisms through which epithelia adapt to their environment, and respond to instructive signals to create the multiple tissues that comprise much of the animal body plan.

However, we should briefly consider first where epithelia come from. Most in vitro studies use clonal populations of epithelial cells that divide indefinitely in culture. However, in vivo many - though not all - epithelia arise from local populations of stem cells, which generate highly proliferative progenitors. These progenitors in turn give rise to fully differentiated epithelial cells that often cease proliferation, but in some tissues continue to divide, or do so in response to specific changes in the environment so as to maintain homeostasis. Because of this developmental mechanism, epithelial cell lines grown in culture might often be more representative of the progenitor/transit amplifying cell-type than of the fully differentiated epithelial cell-type. It is not immediately obvious why the tissue stem cell mechanism has evolved, but one likely factor is the continuous exposure of many epithelia to genotoxic agents present in the environment (chemicals, radiation, viruses). A protected pool of stem cells can replace damaged tissues with new, undamaged cells in a way that would not be possible if all the cells in an epithelium had an equal chance of proliferating. The functions of some highly differentiated epithelial cells might also be incompatible with cell division.

Epithelial Proliferation and Collective Behavior

Localized cell proliferation, cell movement, and apoptosis all contribute to tissue architecture during development, and a key question is how such processes are instructed. How are collective decisions made by an epithelial sheet? Emphasis has traditionally been placed on pre-existing gradients of soluble factors (morphogens) that provide the necessary positional and temporal information. However, there are many examples of self-organization that occur in the presence of homogeneous external signals, such as the development of enteroids or mini-guts from single stem cells in 3D cultures [1]. In vivo, the development of the epithelial wing imaginal discs of Drosophila was thought to require an instructive gradient of secreted Wnt, but flies expressing a membrane-tethered form of the ligand are able to develop normally [2]. Intrinsic cues for self-organization include local signaling, apical/basal polarity, planar cell polarity (PCP), and mechanical forces generated by neighboring cells or by attachment to the extracellular matrix. Examples of local signaling include the activation of Notch by Delta and Ephrin/Eph bidirectional signaling between adjacent cells. Short-range signaling through Hedgehog can also have local effects.

PCP organizes epithelial cells with respect to an extrinsic axis of symmetry, and provides the clearest example of tissue organization through collective behavior. Two sets of genes drive PCP in Drosophila, the Dachsous (Ds)/Fat (Ft) system and the Frizzled (Fz)/Flamingo (Fmi) system, which can interact with one another [3, 4]. Ds, Ft and Fmi are cadherins, while Fz is a receptor for Wnts. Both systems involve local signaling through morphogen gradients that are interpreted by intercellular associations, either of Ds-Ft or Fmi-Fmi, which polarize the cells in particular directions. Structural asymmetries are important in orienting features such as bristles, while asymmetric cell movements shape organs for example during axis elongation in Drosophila [5], gastrulation, neural tube closure, and many other developmental processes. Apical/basal polarity proteins contribute to PCP [6], and can also contribute to super-cellular organization of tissues through apical contraction, which bends the epithelial sheet.

A key signaling pathway involved in PCP, downstream of the Ds/Ft system is the Hippo pathway, first identified in Drosophila but conserved in vertebrates [4]. Hippo controls cell proliferation, and its output is executed through the transcription factor Yorkie (YAP and TAZ in mammals). Interestingly, however, YAP/TAZ also respond, independently of Hippo, to mechanical cues [7]. Stretching of epithelial cells or increasing ECM stiffness, for example, increases cytoskeletal contractility, which activates YAP/TAZ signaling and induces cell proliferation (Figure 1A) [7]. Exactly how this works at a molecular level remains unclear, but tension transduction through α-catenin might play a key role [8]. Stretching forces act on E-cadherin to induce a conformational change in α-catenin that recruits vinculin, stabilizing the α-catenin through links to actin (Figure 1B). Because YAP/TAZ can bind to α-catenin [9] we speculate that this mechanism might be important in regulating its activity. Notably, while important for normal morphogenesis, this response to mechanical forces becomes problematic in carcinomas, where transformed cells generate stiff, high-collagen environments that promote proliferation.

Figure 1.

Effects of intercellular tension on epithelial homeostasis. A. Cell stretching reduces intercellular tension and activates proliferation through YAP/TAZ signaling (YAP marked green, showing nuclear localization in stretched cells). B. A speculative model for YAP/TAZ activation in which stretched adherens junctions bind vinculin (pink rectangles) and actin (purple lines) and release YAP. C. At the edges of epithelial sheets there is less compression, resulting in nuclear YAP and cell proliferation. D. Compressive forces trigger cell extrusion.

Expansion of epithelial sheets requires that the cells must divide, even while retaining contact with one another so as to preserve the integrity of the sheet. Thus, at low density, epithelial cells must be able to ignore or circumvent contact inhibition (Figure 1C). However, as the cells become more crowded, actin capping and severing proteins disassemble stress fibers, adherens junctions become more flexible, and the YAP/TAZ transcription factors are inactivated, blocking cell proliferation. In addition, intercellular engagement of E-cadherin triggers YAP phosphorylation and inactivation [10]. Other inhibitory mechanisms include the sequestration of cell cycle proteins at the tight junctions [11].

Strikingly, compression of epithelial cells, as might occur through over-proliferation or through mechanical deformations, can result in active extrusion and apoptosis, as is discussed in the next section (Figure 1D). Epithelial sheets can respond, therefore, through proliferation, migration, planar polarization, quiescence or extrusion to changes in mechanical forces or to environmental cues, so as self-organize into specific structures, to grow to the correct size, and to maintain homeostasis.

Cell Extrusion from Epithelial Sheets

Epithelial integrity is essential to prevent the unregulated leakage of materials across the barrier created by intercellular adhesions and junctions between epithelial cells. Because epithelia are constantly being damaged by environmental insults or intrinsic defects, robust mechanisms have evolved to eliminate the damaged cells while maintaining this barrier. We can imagine two distinct mechanisms for elimination of damaged cells by their neighbors: extrusion or engulfment. However, although there is some evidence ([12] now disputed; [13]) that engulfment drives the process of cell competition, extrusion appears to be the more common process in epithelial homeostasis. Extrusion is employed to reduce crowding in an epithelial layer and during normal morphogenesis. In these cases the cells are still alive when extruded. Extrusion also occurs at areas of high cell density at fin edges of zebrafish, and at the tips of intestinal villi [14]. Extrusion is apical in these two examples, but embryonic neuroepithelial cells in Drosophila larvae delaminate in a basal direction to generate neuroblast stem cells, and epithelial cells also extrude basally during dorsal closure of the embryo [14, 15].

Why extrusion is preferred over engulfment is unknown. Additionally, it is unclear how the polarity of extrusion is chosen, although the signaling pathways involved are beginning to be uncovered. Using MDCK epithelial cells (Madin Darby canine kidney) in 2D cultures, Rosenblatt and colleagues showed that early apoptotic cells produce and release the bioactive lipid sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) [16], which activates actomyosin contraction in neighboring cells through Gα 12/13 coupled receptors (Figure 2). It is not yet known how apoptotic signals trigger release of the S1P. The S1P receptors stimulate Rho-GTP formation through the exchange factor p115 RhoGEF, with consequent activation of ROCK and phosphorylation of myosin light chain [17]. Microtubules direct the p115 RhoGEF to the basal region of the epithelial cells, to activate actomyosin contraction and induce apical extrusion. The adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein, which binds to and stabilizes the plus ends of microtubules, is required for basal actomyosin contraction [18]. Expression of a truncated, oncogenic form of APC disrupts this polarity, resulting in basal extrusion.

Figure 2.

Signaling involved in the extrusion of apoptotic cells. Cells undergoing apoptosis release sphingosine-1-phosphate, which activates Rho/ROCK signaling in neighboring cells, resulting in basal actomyosin contraction and apical extrusion.

Recently, live cell extrusion from epithelial sheets has been observed in situations of overcrowding both in vitro and in vivo [19]. A stretch-activated ion channel, Piezo1, generates the signal responsible for extrusion, again mediated through S1P, Rho/ROCK, and actomyosin contraction in neighboring cells. However, the link between Piezo1 and S1P remains unknown. In a separate study, using the Drosophila notum as a model of cellular overcrowding, Marinari et al. recently demonstrated that transiently overcrowded cells are stochastically delaminated basally along the midline [20]. Perturbations that either enhance or reduce the activity of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway confirmed that cell growth and density profoundly influences cell delamination. Furthermore, a mathematical model comprising compressibility, junctional tension and contractility, successfully simulated effects on cell density to cause cell delamination from the epithelium as seen in vivo. Additionally, cellular anisotropy also promotes delamination. Cell extrusions under these circumstances are thought to occur independently of cell death; however, mechanical stress on the extruding cells might activate JNK, which could trigger apoptosis [19, 21].

Cell shedding seems to be a conserved feature of multicellular animals, as highlighted by its recent discovery in the nematode, C. elegans [22]. A subset of cells that are developmentally programmed for cell death can be extruded and subsequently undergo apoptosis in the absence of all caspases, through a pathway that requires the polarity protein Par4. The mammalian homologue of Par4 is LKB1, an important tumor suppressor that functions as a master kinase. One downstream target of Par4/LKB1 is AMPK, which controls cell metabolism and is also required for cell extrusion [22]. What proteins act downstream of AMPK is not yet known, and whether other organisms than the worm possess this back-up system for removal of unwanted cells also remains to be determined. Of potential importance is the recent discovery that the Hippo pathway is negatively regulated by LKB1, but through the Par1 proteins kinases downstream of LKB1, rather than through AMPK [23].

Is cell extrusion connected to tumorigenesis? If the transformed cells are resistant to apoptosis, extrusion could in principle provide a mechanism for escape from the epithelium without the cells underdoing an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Second, might extrusion itself contribute to the transformed phenotype? – does the environment within the epithelial sheet restrict cell behavior, forcing the cells to conform to the needs of the tissue in which they are embedded? Concerning this latter idea, an interesting experiment would be to block caspase activation in epithelial cells that are destined to be shed during development, hence blocking their apoptosis. Would such cells, released from the constraints of the epithelial sheet, begin to hyper-proliferate, or lose epithelial character? The experiments described in the next section, on the formation of mesenchymal-like masses from cells that have escaped the epithelium by spindle misorientation, suggest that this fate is quite likely, and that cell death through anoikis is crucial to preventing this dangerous occurrence. As for the extrusion of tumor cells, it is known that when MDCK cells expressing oncogenic Ras are mixed with wild type cells in vitro, the Ras-transformed cells are either apically extruded or – more frequently - generate basal protrusions and invade the underlying ECM [24]. Basal extrusion appears to be triggered by Ras-dependent, autophagy-driven destruction of S1P [25], which blocks the apical pathway. However, extrusion has not yet been demonstrated to occur during cancer initiation in vivo.

Spindle Orientation in Epithelia

Mitotic spindle orientation dictates the cell division plane, which is critical to the morphogenesis of many tissues. For an epithelial sheet, division along each of the three orthogonal axes will have different consequences. Division on the z axis, perpendicular to the sheet, will generate multiple cell layers, while division along the x axis or y axis, parallel to the sheet, with lengthen or widen the sheet, relative to the overall body axis (Figure 3A). For example, cell divisions of the zebrafish dorsal ectoderm are oriented at gastrulation so as to elongate the body axis [26]. If the sheet is rolled into a tube, longitudinal (x) or axial divisions (y) will lengthen the tube - as occurs during renal tubule development [27] or increase its diameter, respectively (Figure 3B). These directionalities are controlled by different systems: z axis division by the apico-basal polarity machinery, and x/y parallel divisions by the PCP machinery.

Figure 3.

Consequences of different mitotic spindle orientations in epithelial tissues. A. Divisions perpendicular to the epithelial sheet generate multilayering; those parallel to the sheet extend the surface area of the sheet. B. In ducts, divisions in the X plane will increase the diameter of the duct, while those in the Y plane will increase its length. C. Convergent extension through cell intercalation alters the shape of epithelial sheets in the absence of oriented divisions. D. Relocation of cells by migration and insertion can restore single layering of epithelial sheets.

It is important to note, however, that alternative mechanisms involving random division planes can in principle generate the same outcomes as would oriented cell divisions. For example, the lengthening of an epithelial sheet can occur through cell intercalation - a process called convergent extension [28], which occurs during gastrulation (Figure 3C). Likewise, extension of a single-layered epithelial sheet does not in principle require parallel divisions – although random orientation of mitosis in the z axis would create multiple cell layers, this could be resolved by migration of the upper, out-of-plane daughters back into the original layer (Figure 3D). This is not so easy to accomplish, because when an epithelial cell divides in the perpendicular direction only the upper daughter will inherit an apical surface. If an upper cell integrates itself fully into the existing layer, the lower daughter will become exposed to the environment, and must create a new apical cortex de novo. An alternative scenario is that a new lumen, lined by apical membrane, forms between the upper and lower daughter cell prior to re-integration, but the upper daughter will then have 2 apical domains initially, at opposite poles of the cell, and these will have to be amalgamated into one in order for the cell to integrate fully into the epithelial sheet. One remarkable example of re-integration has been observed during kidney development, in which cells at the tip of the ureteric bud partially delaminate from the epithelium into the lumen of the bud, where they divide [29]. One daughter remains attached to the basement membrane by a stalk, and quickly reinserts after mitosis; but the other, unattached daughter also reinserts into the epithelium, several cell diameters away from its sibling. In this situation, therefore, mitotic spindle orientation plays no role in epithelial expansion. We do not know if similar mechanisms occur in other tissues or why some tissues choose to use spindle orientation during morphogenesis while others do not.

How is the plane of cell division determined? The process must involve a link between the mitotic apparatus and specific domains of the cell cortex – to the lateral domains of cells undergoing divisions in the plane of the epithelial sheet, or to the anterior/posterior or left/right domains in divisions controlled by the PCP machinery. The astral microtubule (MT) array, which emanates from the spindle poles such that the MT + ends can attach to the cell cortex, fulfills this requirement [30]. Because the mitotic apparatus acts as a rigid body, these MT tethers can hold the apparatus in a particular orientation. Motors such as kinesins or dynein could additionally apply force so as to rotate and hold the apparatus under tension in the correct orientation.

Is this in fact how the plane of cell division is controlled? Much of the early work on mitotic spindle orientation was performed on the C. elegans zygote [31], and on Drosophila stem cells – embryonic neuroblasts and sensory organ precursor (SOP) cells [32]. During the first cell division of the C. elegans embryo the mitotic spindle apparatus undergoes a stereotypical rocking motion and moves towards the posterior end of the cell, so that cytokinesis results in two unequally sized cells with different cell fates [33]. Laser ablation experiments to sever microtubules demonstrated that the mitotic spindle in the one-cell C. elegans embryo is positioned by unequal forces pulling on astral microtubules, with more force generators at the posterior relative to the anterior aster [34]. An unexpected discovery was the involvement of G-protein α subunits in spindle positioning. Gα is associated with the plasma membrane, and becomes enriched at the posterior end of the cell during anaphase. It recruits two proteins, GPR-1/2 and LIN-5, which couple astral MTs to the Gα subunit. The actin cytoskeleton helps anchor this complex at the cortex, and dynein provides the pulling force that positions the spindle. Elegant in vitro studies have demonstrated that dynein captures the MT+ ends and triggers MT shrinkage, which generates the pulling force [35].

This G-protein based complex is conserved throughout the animal kingdom. The Drosophila homologues for GPR and LIN-5 are Pins (Partner of Inscuteable) and Mud, respectively, while in mammals the homologues are LGN and NuMA [36, 37]. GPR, Pins and LGN possess similar domain structures, with C-terminal GoLoco motifs that bind to Gα-GDP, and N-terminal TPR motifs that interact with LIN-5, Mud or NuMA (Figure 4A). The level of similarity between LIN-5, Mud and NuMA is very low at the amino acid level and was unrecognized for several years. Nonetheless the proteins are functionally conserved. Both Mud and NuMA can bind to MTs directly as well as to dynein, and enhance MT polymerization (Figure 4A). They also associate with centrosomes and play a role in spindle pole organization, possibly through a distinct protein complex that includes calmodulin and the Asp/ASPM-1 protein [38].

Figure 4.

The molecular basis for spindle orientation. A. The LGN protein and its homologues consists of 2 domains connected by a hinge. The N-terminal TPR motifs bind to NuMA and to Inscuteable; the C-terminal GoLoCo domains bind to Gα-GDP subunits. NuMA is a very large protein with multiple C-terminal motifs that bind multiple proteins involved in spindle orientation. B. Schematic showing the location of spindle orientation proteins at different phases of the cell cycle. C. In metaphase, LGN undergoes a conformational switch. In the open state it binds both to Gα at the cell cortex, and to NuMA and dynein. In anaphase LGN is replaced by the cytoskeletal protein 4.1R.

During interphase the Pins/LGN protein is in a closed conformation that has only a low affinity for Gα, and is distributed diffusely in the cytoplasm [39]. Mud/NuMA on the other hand is sequestered in the nucleus (Figure 4B). Breakdown of the nuclear envelope at the beginning of mitosis enables Mud/NuMA to associate with Pins/LGN, triggering a conformational switch to an open conformation that can bind Gα [39]. This co-operative interaction drives recruitment of the complex to the cell cortex, where it can tether astral MTs (Figure 4C). Exactly how tethering is established remains to be fully understood, because the binding site on NuMA for MTs overlaps with that for LGN and binding is mutually exclusive [40]. Dynein binding, both to NuMA and to LGN [41], and NuMA oligomerization, might both play roles in tethering.

Several recent studies have identified an important and unexpected switch in the NuMA complex that occurs during the transition from metaphase to anaphase, which functions both to center and to elongate the spindle [42-44]. This switch promotes both NuMA and dynein accumulation at the cell cortex. NuMA binds to the 4.1 G/R cytoskeletal protein at the cortex, independently of LGN (Figure 4B). Moreover, during metaphase, NuMA is phosphorylated by CDK1/2 on T2055, which negatively regulates cortical attachment, and is desphosphorylated in anaphase, driving increased attachment, presumably through 4.1G/R, though also possibly through other mechanisms. It remains unclear exactly how and why NuMA is dissociated from the LGN complex at the end of metaphase.

NuMA is also phosphorylated during mitosis by the Abl1 tyrosine kinase, on Y1774 (a residue absent from Mud and LIN-5) [45]. This modification is important for maintenance of the cortical attachment of NuMA during metaphase, and disruption of Abl1 function causes spindle orientation defects. However, the molecular basis for cortical attachment remains unclear, especially as Y1774 phosphorylation does not seem to alter LGN binding to NuMA.

Polo-like kinase (Plk1), which is localized to the spindle poles, also regulates spindle orientation, by inhibiting the interaction between NuMA/LGN and dyneindynactin [46], but the target of Plk1 is not yet known. Additionally, high RanGTP levels in the vicinity of the chromosomes displace NuMA from the cortex, helping to generate an asymmetric distribution of NuMA around the periphery of the mitotic cell [46].

Inhibition of Abl1 causes spindle orientation defects in mammalian epidermal cells, but whether these other mechanisms function in determining spindle orientation within epithelial sheets in vivo remains to be established. So far, different factors appear to predominate. Simple epithelial tissues expand by division in the plane of the sheet, so a key requirement is to accumulate the LGN-NuMA complex on the lateral cortex and exclude it from the apical and basal domains. Multiple mechanisms appear to be involved in this process, that are context-dependent. In mammalian epithelia, two complementary processes appear to be involved, one negative and one positive. Both involve the phosphorylation of LGN by atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) or other kinases. Atypical PKC is a component of the conserved PAR polarity complex, and localizes to the apical cortex in epithelial cells throughout the animal kingdom. A key function of the kinase is to exclude non-apical proteins from this domain. One of these proteins is LGN (or Pins), which can be phosphorylated by aPKC in the central linker region that couples the N-terminal TPR motifs to the C-terminal GoLoCo domains [47]. This phosphorylation is recognized by the 14-3-3 protein, the binding of which probably induces a conformational switch, disassociating LGN from Gα. In this way, LGN is removed from the apical surface. The positive arm of this mechanism involves recognition of the phosphorylated LGN by Discs Large (Dlg) on the lateral cell cortex. Strikingly, the GK (guanylate kinase) domain within this protein has evolved a novel function, losing its kinase activity and gaining the ability to recognize and bind to phosphorylated LGN/Pins [48, 49]. The interaction of Pins with Dlg is particularly important for control of spindle orientation in the Drosophila follicular epithelium [50]. However, in this tissue aPKC is not required, and it is conceivable that another kinase, perhaps Aurora A, performs the same function of phosphorylating Pins, as has been reported for fly S2 cells [51]. However, mutation of the known AuroraA/aPKC phosphorylation Ser residue does not appear to disrupt spindle orientation, so perhaps a different type of interaction with Dlg is involved. Finally, we note that spindle orientation in the chick neuroepithelium is also aPKC independent, but still depends on the formation of a lateral belt of LGN and NuMA [52]. How this belt is organized remains mysterious.

So far we have discussed the control of the plane of cell division in simple epithelia. The formation of stratified epithelium, for example in the epidermis, is more complicated, however, as it derives from a progenitor layer (basal cells) that must both self-renew and give rise to multiple layers of differentiated epithelial cells. In principle there are multiple alternative mechanisms that might enable this process; for example basal cells might occasionally be delaminated or might crawl out of the basal layer and differentiate. Alternatively, they might use a spindle orientation mechanism, dividing horizontally to self-renew but vertically to generate the outer stratified layers. The skin uses this last mechanism, in which vertical divisions are asymmetric such that the lower daughter remains a basal cell and the upper daughter becomes a keratinocyte [53]. Notably, this switch in orientation requires LGN but additionally involves an LGN/Pins binding protein called Inscuteable, which was first discovered in studies of the Drosophila neuroblast [54]. These embryonic stem cells arise by delamination from the neuroectoderm and must divide asymmetrically to generate neurons. An apical crescent in the neuroblast containing the Par3 polarity protein recruits Insc to the cortex, together with Pins and Mud. This complex orients the mitotic spindle vertically, so as to create daughter cells with different fates. Similarly, a related protein in mammals, called mInsc, is required for the vertical orientation of spindles in epidermal basal cells [53]. Interestingly, Insc and NuMA bind to the same region of LGN/Pins in a mutually exclusive fashion [55], so how the Insc/Pins complex can attach to astral microtubules during mitosis remains unclear.

What are the biological consequences of defects in mitotic orientation? Given the high level of conservation of the spindle orientation machinery throughout the animal kingdom, and the importance of spindle orientation in stem cell function and epithelial tissue organization, one might have predicted that deletion of LGN or Insc would be embryonic lethal in mice. Yet these deletions have remarkably little effect on embryogenesis. Neuroepithelial divisions become randomized but without effecting neuronal production rates [56]. Similarly, a mInsc knockout is viable, although it presents defects in planar asymmetry of the cochlea hair cells and in lineage specification of cortical progenitors [57, 58]. One explanation might be that related proteins (AGS3 and mInsc2) can compensate for the loss of LGN or mInsc. Alternatively, back-up systems might exist in vivo that can rescue the correct spindle orientation during mitosis. It will be important to address these issues in the future, and to determine if loss of epithelial spindle orientation is involved in tumorigenesis. Exciting experiments in the imaginal disks of Drosophila indicate that cell polarity mutations that disrupt spindle orientation enable the escape of epithelial cells from the tissue through spindle misorientation, but the escaped cells die – possibly through anoikis, a form of apoptosis triggered by loss of attachment to the ECM [59]. However, if cell death is blocked by inhibiting caspases, the escaped cells lose their epithelial character and proliferate to form an extra-epithelial cell mass. Whether this overgrowth occurs in mammals and is a common early step towards cancer remains to be tested.

The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a genetic program characterized by the loss of both tight and apical junctions, loss of apical-basal polarity, and loss of expression of epithelial proteins such as E-cadherin, with a reciprocal increase in the expression of mesenchymal markers such as Vimentin. The mesenchymal cells can escape the epithelium and migrate to distant sites within the organism. EMT and the reverse transition (MET) are well-conserved mechanisms that are essential for tissue remodeling and progenitor cell dissemination during development. However, the loss of epithelial character is also associated with an invasive and aggressive type of cancer cell arising from epithelial tissues [60].

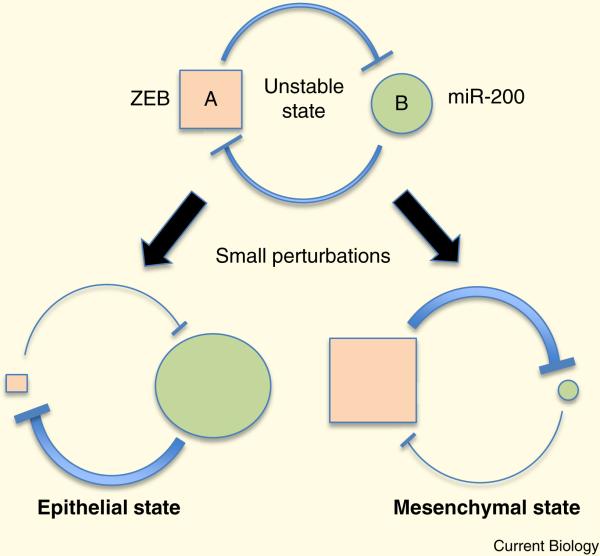

A confusing aspect of EMT is the plethora of factors that induce it. PRRX1, ZEB, TWIST, SNAIL, GATA6, and SOX4 transcription factors all act by directly blocking the expression of crucial components of epithelial identity, including polarity proteins such as Crumbs, Lgl, Patj, and E-cadherin, while driving expression of a mesenchymal gene signature [61]. In turn, these factors both suppress and are suppressed by multiple miRNAs. For example, ZEB and SNAIL inhibit the expression of the miR200 micro-RNA family, which promote epithelialization. Through a double-negative feedback loop, miR200 also suppresses ZEB expression. Double-negative circuits are bi-stable since they will tend to remain in one state (off or on) until perturbed when, in the absence of any stabilizing influence, they can flip to the other state (Figure 5). For instance, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ⍰, which induces expression of the ZEB, SNAIL, TWIST and SOX4 families, can be generated in an autocrine loop to stabilize the mesenchymal state (low miR200) [62].

Figure 5.

Mutually inhibitory circuits are inherently unstable but in response to small perturbations to the concentration of one of the two factors (A and B) can switch to one of 2 stable states. This type of circuit might control the decision by cells to become either mesenchymal or epithelial.

TGFβ is a well-known driver of EMT in the context of cancer progression and metastasis. Whereas the canonical pathway downstream of the TGFβ receptor modulates gene expression through phosphorylation of the Smad transcription factors, there is an additional pathway that acts through the Par polarity proteins to alter cell behavior. Ligand engagement of the TGFβ⍰receptor 2 (TβRII) promotes binding to TβRI and phosphorylation of Par6 on a conserved serine residue, S345 [63]. This phosphorylation can recruit an E3 ubiquitin ligase, Smurf1, to the PAR6 complex, to promote degradation of the RhoA GTPase and disintegration of the tight junctions. However, the canonical Smad pathway also induces a micro-RNA which targets RhoA, miR-155 [64].

How frequently is EMT induced during the dissemination of epithelial cancers? This is a difficult question to answer and a contentious issue among cancer biologists. Mouse models suggest that Snail is sufficient to induce EMT in primary tumor cells and can promote mammary tumor recurrence, associated with loss of E-cadherin [65]. Moreover, many human invasive breast cancers express the collagen receptor DDR2, which stabilizes Snail and thereby perhaps promote invasive behavior [66]. There are clear differences in cell morphology and behavior at the invasive edges as compared to the body of carcinomas, for instance in a loss of cortical E-cadherin localization, suggesting that interactions with the micro-environment can drive a partial EMT response [67]. In support of this idea, a mouse model of pancreatic cancer showed that inflammatory stroma can induce a partial EMT in the tumor cells (high Zeb1 but also E-cadherin) and rapid dissemination to the liver [68]. However, among human carcinomas, there is no clear association of the EMT master regulators (Zeb, Snail, Twist) with clinical outcome [69]; and using invasive breast cancer as a specific example, some researchers find no consistent differences in expression of EMT regulators between cells located at the invasion front and the center of a tumor [70]. Additionally, Twist expression can induce the dissemination of primary mammary cells without loss of E-cadherin, and silencing of E-cadherin strongly inhibits Twist-mediated dissemination [71].

A loss of epithelial identity can actually suppress the formation of tumor-initiating cells [72], and acts as a limiting factor for metastatic colonization in mouse models [73, 74]. Moreover, primary human breast cancer cells grown in 3D collagen matrices migrate not as single mesenchymal cells but collectively, as clusters of epithelial-like cells [75]. Loss of the Par3 polarity protein can promote dissemination of epithelial mammary tumors in mice, induced by expression of the Notch oncogene, without any overt EMT, and these cells also migrate collectively [76]. Even circulating cancer cells from patients with breast cancer are often epithelial in character, and sometimes occur in clusters [77].

Overall, we conclude that EMT is undoubtedly important in some forms of cancer, and can contribute to dissemination and metastasis, but that there are other mechanisms of cancer cell dissemination that do not involve loss of the epithelial phenotype. An interesting experiment would be to induce EMT in isolated cells within an epithelial monolayer and ask if they are able to escape from the tissue, if they extrude basally or apically, or if they are eliminated, as described below, by cell competition.

Cell Competition

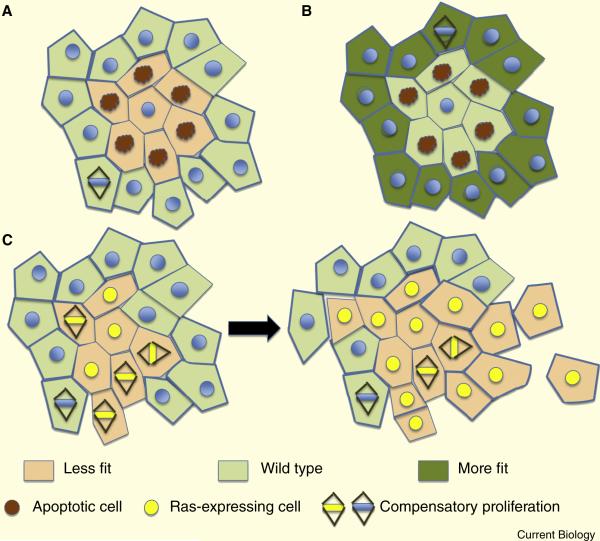

The term “cell competition” was coined in 1975 by Morata and Ripoll, when they observed that clonal patches of cells deficient for ribosomal proteins (known as Minute clones) were overgrown by surrounding cells and eventually eliminated by apoptosis [78]. It was later shown that this remarkable process depended on close-range interactions between the mutant cells and surrounding wild-type tissue. The key feature of cell competition is that interactions between more fit “winner” and less fit “loser” cells induces elimination of the latter, suggesting that it functions as a form of quality control to remove suboptimal cells (Figure 6A). Importantly, less fit cells can remain viable if they do not encounter stronger neighbors, as evidenced by their ability to form whole functional organs in the absence of competitive interactions [78, 79]. Moreover, cells in the interior of suboptimal clones survive while those at boundaries with more fit neighbors are eliminated (Figure 6A), supporting the idea that for this type of competition cell contact is needed to assess relative fitness. For other competition drivers, such as the dMyc proto-oncogene, effects occur over several cell diameters [80, 81], suggesting that secreted factors might be involved [81].

Figure 6.

Cell competition. A. The schematic shows the consequences when a clone of less fit cells (pink), for instance that is mutant for a polarity protein, is surrounded by wild type cells (pale green). The less fit cells at the boundary undergo apoptosis (red nuclei), and are replaced by the more fit cells through compensatory proliferation. B. The cells sense relative fitness, such that a clone of wild type cells will be eliminated by “supercompetitor” neighbors (dark green). C. Expression of an oncogene such as Ras (yellow nuclei), which would by itself cause hyperproliferation but not invasive outgrowth, can drive invasion in the context of a polarity mutation. The polarity mutant cells (pink) would normally be induced to undergo apoptosis by their more fit neighbors (as in A) but the oncogene subverts the apoptotic signaling into a proliferative state that can drive invasive tumorigenesis.

Exactly how “fitness” is defined and assessed remains rather vague, despite intensive research, and seems to differ with the type of defect in the loser cells [82], but competition often selects cells with greater proliferative ability. This effect is illustrated by dMyc in wing imaginal discs. Although total loss of this gene is lethal, flies suffering hypomorphic mutations are viable, displaying only minor defects. However, if clonal patches of hypomorphic cells are generated within a wild-type imaginal disc, the surrounding cells induce the hypomorphic cells to apoptose. Conversely, if a clone of dMyc over-expressors is generated, it will outcompete neighboring normal cells (Figure 6B) [83]. Such over-expressing cells are termed “supercompetitors” [80], and demonstrate that the measure of fitness between neighboring cells is relative rather than absolute (Figure 7).

A similar mechanism monitors for defects in genes that control epithelial cell structure. For example, Scribble is a highly conserved regulator of apical-basal polarity in fly epithelial tissues that also behaves as a tumor suppressor [84]. Larvae carrying homozygous mutations for this gene develop normally as long as the maternal supply of Scrib is maintained, but upon depletion, the epithelial tissues lose polarity and become insensitive to size control [84]. Similar effects have been reported for mutations of another polarity gene/tumor suppressor, Lethal giant larvae (Lgl). The cells overgrow, and the larvae die as large masses of poorly differentiated tissue. If, however, clones of cells deficient for Scrib are generated in wing imaginal discs, interactions with surrounding wild-type cells and circulating hemocytes eliminate the compromised cells through a complicated network of signals that requires TNFα-mediated JNK activation and JAK/STAT signaling in the normal neighbors, and Hippo signaling and JNK-mediated apoptosis in the defective cells [85-87]. Interestingly, JNK activation in the surrounding normal cells promotes the engulfment of their Scrib-defective neighbors [88]. These findings indicate that cell competition acts to eliminate cells that threaten normal tissue integrity or have tumorigenic potential.

Cell competition can also eliminate clones that express activated oncogenes. Cells with aberrant activation of dSrc signaling (via dominant negative mutations in Csk, a kinase that inhibits dSrc) form viable, though overgrown tissues when uniformly expressed in the eye and wing disc. However, when mosaic expression is induced in the wing, the transformed cells are extruded basally. This extrusion involves relocalization of E-cadherin and p120 catenin within cells, depends upon JNK activity, and is associated with JNK-dependent apoptosis [89]. Notably, only cells in close approximation to wild-type cells undergo apoptosis and delamination. The same authors demonstrated that a similar phenotype is observed at the interface between human squamous cell carcinomas and the surrounding normal tissue, albeit without determining the mechanism involved [67]. However, cells expressing oncogenic Ras are not eliminated but are hyper-proliferative, and in the context of a Scrib mutation become super-competitors that form invasive tumors, through subversion of the same signaling pathways that would normally trigger apoptosis in the Scrib-defective cells (Figure 6C) [86, 90-92]. Different oncogenic proteins can, therefore, exert very different effects depending on the cellular context.

Mammalian cell cultures have also been observed to detect and react to transformed cells. When MDCK cells expressing constitutively active Ras are surrounded by wild-type cells, some of the transformed cells are extruded apically from the epithelial sheet in a process that depends upon myosin-II activation and actin polymerization [24], but the majority invade the basal matrix in a manner reminiscent of Csk-deficient Drosophila cells. This choice of direction appears to be controlled by S1P, which, as described above also determines extrusion of apoptotic cells. Ras transformation promotes autophagy, resulting in the destruction of both S1P and its receptor, S1P2, which are required for apical extrusion . However, this directionality is not generalizable to all oncogenes, as Src- MDCK cells surrounded by wild-type counterparts are extruded only apically.

Does classical cell competition occur between mammalian cells? In two-dimensional culture, MDCK cells that are deficient for either the polarity gene Scrib or Mahjong, which interacts with the polarity regulator Lgl, undergo apoptosis when surrounded by wild-type neighbors [93, 94]. Moreover, while these cells are extruded from the cell monolayer via myosin contractions, the apoptosis observed is not dependent upon extrusion. Cell death and extrusion are not observed in homogenously transformed cells. While these findings have yet to be demonstrated in vivo in mammalian tissue, they do show that mammalian epithelia appear capable of competing in a way that is analogous to Drosophila tissues.

There is limited in vivo evidence for cell competition in mammals, albeit not in mature epithelial compartments. In elegant studies utilizing p53 heterozygous mutant mice, Bondar and Medzhitov showed that cells expressing lower levels of p53 outcompete their wild-type counterparts in mice when repopulating lethally irradiated hematopoietic compartments [95]. This competition, however, was distinct from that seen in Drosophila epithelium because it involved senescence rather than apoptosis of loser cells. Two recent papers have also reported competition between pluripotent stem cells in the inner cell mass of mouse embryos that closely resembles competition seen in flies [96, 97]. This competition involves sensing of differential cMyc expression in adjacent cells, with loser cells undergoing apoptosis.

Finally, an interesting concept is that some genes might not promote cell competition but actually suppress it, to prevent exploitive overgrowth during embryogenesis by a minority of super-competitors. A genome-wide screen in induced pluripotent stem cells has in fact detected such genes [98]. Olfactory receptors, p53, and topoisomerase 1 were identified as central players that when down-regulated enabled out-competition with wild type cells in the mouse embryo, without perturbing normal development. It remains unclear, however, whether these genes normally suppress competition or work through a distinct mechanism.

Definitive studies of epithelial cell competition in mammalian models await the development of genetic tools and in vivo imaging methods to establish and monitor winner and loser clones in mouse tissues. However, the current evidence leads us to speculate that cell competition is a highly conserved mechanism for maximizing tissue fitness, and might contribute to epithelial integrity. It will be of great interest to determine if sphingosine signaling plays any role in classical cell competition both in Drosophila and in mammals.

Conclusions

Recent work has deepened our understanding of epithelial homeostasis and revealed unexpectedly high degrees of control by physical forces acting on epithelial cells. The discoveries that crowding can induce extrusion while reduced tension promotes proliferation are likely to provide new insights into tissue morphogenesis. Spindle orientation is also important in morphogenesis and stem cell function, and likely plays a role in cancer initiation. Many signaling pathways impinge on spindle orientation and much remains to be learned about its control. Similarly, the signaling mechanisms underlying cell competition are still something of a mystery, and it will be important to investigate possible links between competition and other mechanisms of epithelial homeostasis, both mechanical and biological. We foresee eventual applications of this knowledge in the bioengineering of epithelial tissues for regenerative medicine, in addition to deepening our understanding of tumorigenesis.

Abbreviations

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (a genetic program that triggers loss of epithelial character, loss of cell-cell adhesion, and increases cell motility)

- MET

mesenchymal-epithelial transition

- PCP

planar cell polarity (tissue polarization with respect to a body axis)

- Apical/basal polarity

cell autonomous polarization perpendicular to the epithelial sheet

- Convergent extension

an embryonic process in which cell movements and/or reorganization drive a reduction in width and an increase in length of a tissue, for example during gastrulation.

- Anoikis

a form of apoptosis, driven by loss of attachment of epithelial cells to the extracellular matrix.

References

- 1.Sato T, Clevers H. Growing self-organizing mini-guts from a single intestinal stem cell: mechanism and applications. Science. 2013;340:1190–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1234852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandre C, Baena-Lopez A, Vincent JP. Patterning and growth control by membrane-tethered Wingless. Nature. 2014;505:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature12879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matis M, Axelrod JD. Regulation of PCP by the Fat signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2207–2220. doi: 10.1101/gad.228098.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence PA, Casal J. The mechanisms of planar cell polarity, growth and the Hippo pathway: some known unknowns. Dev Biol. 2013;377:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simoes Sde M, Blankenship JT, Weitz O, Farrell DL, Tamada M, Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Zallen JA. Rho-kinase directs Bazooka/Par-3 planar polarity during Drosophila axis elongation. Dev Cell. 2010;19:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djiane A, Yogev S, Mlodzik M. The apical determinants aPKC and dPatj regulate Frizzled-dependent planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 2005;121:621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, Giulitti S, Michielin F, Elvassore N, Dupont S, Piccolo S. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yonemura S, Wada Y, Watanabe T, Nagafuchi A, Shibata M. alpha-Catenin as a tension transducer that induces adherens junction development. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:533–542. doi: 10.1038/ncb2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silvis MR, Kreger BT, Lien WH, Klezovitch O, Rudakova GM, Camargo FD, Lantz DM, Seykora JT, Vasioukhin V. {alpha}-Catenin Is a Tumor Suppressor That Controls Cell Accumulation by Regulating the Localization and Activity of the Transcriptional Coactivator Yap1. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra33. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim NG, Koh E, Chen X, Gumbiner BM. E-cadherin mediates contact inhibition of proliferation through Hippo signaling-pathway components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11930–11935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103345108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balda MS, Garrett MD, Matter K. The ZO-1-associated Y-box factor ZONAB regulates epithelial cell proliferation and cell density. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:423–432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Baker NE. Engulfment is required for cell competition. Cell. 2007;129:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lolo FN, Casas-Tinto S, Moreno E. Cell competition time line: winners kill losers, which are extruded and engulfed by hemocytes. Cell reports. 2012;2:526–539. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Y, Rosenblatt J. New emerging roles for epithelial cell extrusion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:865–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homem CC, Knoblich JA. Drosophila neuroblasts: a model for stem cell biology. Development. 2012;139:4297–4310. doi: 10.1242/dev.080515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu Y, Forostyan T, Sabbadini R, Rosenblatt J. Epithelial cell extrusion requires the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 pathway. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:667–676. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slattum G, McGee KM, Rosenblatt J. P115 RhoGEF and microtubules decide the direction apoptotic cells extrude from an epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:693–702. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall TW, Lloyd IE, Delalande JM, Nathke I, Rosenblatt J. The tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli controls the direction in which a cell extrudes from an epithelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:3962–3970. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhoffer GT, Loftus PD, Yoshigi M, Otsuna H, Chien CB, Morcos PA, Rosenblatt J. Crowding induces live cell extrusion to maintain homeostatic cell numbers in epithelia. Nature. 2012;484:546–549. doi: 10.1038/nature10999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marinari E, Mehonic A, Curran S, Gale J, Duke T, Baum B. Live-cell delamination counterbalances epithelial growth to limit tissue overcrowding. Nature. 2012;484:542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature10984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson MC, Perrimon N. Extrusion and death of DPP/BMPcompromised epithelial cells in the developing Drosophila wing. Science. 2005;307:1785–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1104751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denning DP, Hatch V, Horvitz HR. Programmed elimination of cells by caspase-independent cell extrusion in C. elegans. Nature. 2012;488:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohseni M, Sun J, Lau A, Curtis S, Goldsmith J, Fox VL, Wei C, Frazier M, Samson O, Wong KK, et al. A genetic screen identifies an LKB1-MARK signalling axis controlling the Hippo-YAP pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:108–117. doi: 10.1038/ncb2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan C, Dupre-Crochet S, Norman M, Kajita M, Zimmermann C, Pelling AE, Piddini E, Baena-Lopez LA, Vincent JP, Itoh Y, et al. Characterization of the interface between normal and transformed epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:460–467. doi: 10.1038/ncb1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slattum G, Gu Y, Sabbadini R, Rosenblatt J. Autophagy in oncogenic K-Ras promotes basal extrusion of epithelial cells by degrading S1P. Curr Biol. 2014;24:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong Y, Mo C, Fraser SE. Planar cell polarity signalling controls cell division orientation during zebrafish gastrulation. Nature. 2004;430:689–693. doi: 10.1038/nature02796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, Nato F, Nicolas JF, Torres V, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller R. Shaping the vertebrate body plan by polarized embryonic cell movements. Science. 2002;298:1950–1954. doi: 10.1126/science.1079478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Packard A, Georgas K, Michos O, Riccio P, Cebrian C, Combes AN, Ju A, Ferrer-Vaquer A, Hadjantonakis AK, Zong H, et al. Luminal mitosis drives epithelial cell dispersal within the branching ureteric bud. Dev Cell. 2013;27:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang N, Marshall WF. Centrosome positioning in vertebrate development. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4951–4961. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowerman B, Shelton CA. Cell polarity in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:390–395. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siller KH, Doe CQ. Spindle orientation during asymmetric cell division. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:365–374. doi: 10.1038/ncb0409-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cowan CR, Hyman AA. Asymmetric cell division in C. elegans: cortical polarity and spindle positioning. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:427–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.113823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grill SW, Howard J, Schaffer E, Stelzer EH, Hyman AA. The distribution of active force generators controls mitotic spindle position. Science. 2003;301:518–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1086560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laan L, Pavin N, Husson J, Romet-Lemonne G, van Duijn M, Lopez MP, Vale RD, Julicher F, Reck-Peterson SL, Dogterom M. Cortical dynein controls microtubule dynamics to generate pulling forces that position microtubule asters. Cell. 2012;148:502–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergstralh DT, Haack T, St Johnston D. Epithelial polarity and spindle orientation: intersecting pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20130291. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein B, Macara IG. The PAR proteins: fundamental players in animal cell polarization. Dev Cell. 2007;13:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Voet M, Berends CW, Perreault A, Nguyen-Ngoc T, Gonczy P, Vidal M, Boxem M, van den Heuvel S. NuMA-related LIN-5, ASPM-1, calmodulin and dynein promote meiotic spindle rotation independently of cortical LIN-5/GPR/Galpha. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:269–277. doi: 10.1038/ncb1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du Q, Macara IG. Mammalian Pins is a conformational switch that links NuMA to heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell. 2004;119:503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du Q, Taylor L, Compton DA, Macara IG. LGN blocks the ability of NuMA to bind and stabilize microtubules. A mechanism for mitotic spindle assembly regulation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1928–1933. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng Z, Wan Q, Meixiong G, Du Q. Cell cycle-regulated membrane binding of NuMA contributes to efficient anaphase chromosome separation. Mol Biol Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-08-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiyomitsu T, Cheeseman IM. Cortical dynein and asymmetric membrane elongation coordinately position the spindle in anaphase. Cell. 2013;154:391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kotak S, Busso C, Gonczy P. NuMA phosphorylation by CDK1 couples mitotic progression with cortical dynein function. Embo J. 2013;32:2517–2529. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seldin L, Poulson ND, Foote HP, Lechler T. NuMA localization, stability, and function in spindle orientation involve 4.1 and Cdk1 interactions. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:3651–3662. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-05-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumura S, Hamasaki M, Yamamoto T, Ebisuya M, Sato M, Nishida E, Toyoshima F. ABL1 regulates spindle orientation in adherent cells and mammalian skin. Nature communications. 2012;3:626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiyomitsu T, Cheeseman IM. Chromosome- and spindle-polederived signals generate an intrinsic code for spindle position and orientation. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:311–317. doi: 10.1038/ncb2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao Y, Du Q, Chen X, Zheng Z, Balsbaugh JL, Maitra S, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Macara IG. Par3 controls epithelial spindle orientation by aPKC-mediated phosphorylation of apical Pins. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1809–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu J, Shang Y, Xia C, Wang W, Wen W, Zhang M. Guanylate kinase domains of the MAGUK family scaffold proteins as specific phosphoprotein-binding modules. Embo J. 2011;30:4986–4997. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston CA, Doe CQ, Prehoda KE. Structure of an enzymederived phosphoprotein recognition domain. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergstralh DT, Lovegrove HE, St Johnston D. Discs large links spindle orientation to apical-basal polarity in Drosophila epithelia. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1707–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnston CA, Hirono K, Prehoda KE, Doe CQ. Identification of an Aurora-A/PinsLINKER/Dlg spindle orientation pathway using induced cell polarity in S2 cells. Cell. 2009;138:1150–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peyre E, Jaouen F, Saadaoui M, Haren L, Merdes A, Durbec P, Morin X. A lateral belt of cortical LGN and NuMA guides mitotic spindle movements and planar division in neuroepithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:141–154. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lechler T, Fuchs E. Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature. 2005;437:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nature03922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kraut R, Chia W, Jan LY, Jan YN, Knoblich JA. Role of inscuteable in orienting asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila. Nature. 1996;383:50–55. doi: 10.1038/383050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu J, Wen W, Zheng Z, Shang Y, Wei Z, Xiao Z, Pan Z, Du Q, Wang W, Zhang M. LGN/mInsc and LGN/NuMA complex structures suggest distinct functions in asymmetric cell division for the Par3/mInsc/LGN and Galphai/LGN/NuMA pathways. Mol Cell. 2011;43:418–431. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Konno D, Shioi G, Shitamukai A, Mori A, Kiyonari H, Miyata T, Matsuzaki F. Neuroepithelial progenitors undergo LGN-dependent planar divisions to maintain self-renewability during mammalian neurogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:93–101. doi: 10.1038/ncb1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Postiglione MP, Juschke C, Xie Y, Haas GA, Charalambous C, Knoblich JA. Mouse inscuteable induces apical-basal spindle orientation to facilitate intermediate progenitor generation in the developing neocortex. Neuron. 2011;72:269–284. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tarchini B, Jolicoeur C, Cayouette M. A molecular blueprint at the apical surface establishes planar asymmetry in cochlear hair cells. Dev Cell. 2013;27:88–102. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakajima Y, Meyer EJ, Kroesen A, McKinney SA, Gibson MC. Epithelial junctions maintain tissue architecture by directing planar spindle orientation. Nature. 2013;500:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nature12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim J, Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: insights from development. Development. 2012;139:3471–3486. doi: 10.1242/dev.071209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular Mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peinado H, Quintanilla M, Cano A. Transforming growth factor beta-1 induces snail transcription factor in epithelial cell lines: mechanisms for epithelial mesenchymal transitions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21113–21123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ozdamar B, Bose R, Barrios-Rodiles M, Wang HR, Zhang Y, Wrana JL. Regulation of the polarity protein Par6 by TGFbeta receptors controls epithelial cell plasticity. Science. 2005;307:1603–1609. doi: 10.1126/science.1105718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kong W, Yang H, He L, Zhao JJ, Coppola D, Dalton WS, Cheng JQ. MicroRNA-155 is regulated by the transforming growth factor beta/Smad pathway and contributes to epithelial cell plasticity by targeting RhoA. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6773–6784. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00941-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moody SE, Perez D, Pan TC, Sarkisian CJ, Portocarrero CP, Sterner CJ, Notorfrancesco KL, Cardiff RD, Chodosh LA. The transcriptional repressor Snail promotes mammary tumor recurrence. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang K, Corsa CA, Ponik SM, Prior JL, Piwnica-Worms D, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ, Longmore GD. The collagen receptor discoidin domain receptor 2 stabilizes SNAIL1 to facilitate breast cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:677–687. doi: 10.1038/ncb2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vidal M, Salavaggione L, Ylagan L, Wilkins M, Watson M, Weilbaecher K, Cagan R. A role for the epithelial microenvironment at tumor boundaries: evidence from Drosophila and human squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:3007–3014. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, Maitra A, Bailey JM, McAllister F, Reichert M, Beatty GL, Rustgi AK, Vonderheide RH, et al. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012;148:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taube JH, Herschkowitz JI, Komurov K, Zhou AY, Gupta S, Yang J, Hartwell K, Onder TT, Gupta PB, Evans KW, et al. Core epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition interactome gene-expression signature is associated with claudin-low and metaplastic breast cancer subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15449–15454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alkatout I, Wiedermann M, Bauer M, Wenners A, Jonat W, Klapper W. Transcription factors associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells in the tumor centre and margin of invasive breast cancer. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2013;94:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shamir ER, Pappalardo E, Jorgens DM, Coutinho K, Tsai WT, Aziz K, Auer M, Tran PT, Bader JS, Ewald AJ. Twist1-induced dissemination preserves epithelial identity and requires E-cadherin. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:839–856. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Celia-Terrassa T, Meca-Cortes O, Mateo F, de Paz AM, Rubio N, Arnal-Estape A, Ell BJ, Bermudo R, Diaz A, Guerra-Rebollo M, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition can suppress major attributes of human epithelial tumor-initiating cells. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1849–1868. doi: 10.1172/JCI59218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Korpal M, Ell BJ, Buffa FM, Ibrahim T, Blanco MA, Celia-Terrassa T, Mercatali L, Khan Z, Goodarzi H, Hua Y, et al. Direct targeting of Sec23a by miR-200s influences cancer cell secretome and promotes metastatic colonization. Nat Med. 2011;17:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nm.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ocana OH, Corcoles R, Fabra A, Moreno-Bueno G, Acloque H, Vega S, Barrallo-Gimeno A, Cano A, Nieto MA. Metastatic colonization requires the repression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer Prrx1. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:709–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheung KJ, Gabrielson E, Werb Z, Ewald AJ. Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell. 2013;155:1639–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCaffrey LM, Montalbano J, Mihai C, Macara IG. Loss of the Par3 polarity protein promotes breast tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:601–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, Stott SL, Smas ME, Ting DT, Isakoff SJ, Ciciliano JC, Wells MN, Shah AM, et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 2013;339:580–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1228522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morata G, Lawrence PA. Control of compartment development by the engrailed gene in Drosophila. Nature. 1975;255:614–617. doi: 10.1038/255614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnston LA, Prober DA, Edgar BA, Eisenman RN, Gallant P. Drosophila myc regulates cellular growth during development. Cell. 1999;98:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81512-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.de la Cova C, Abril M, Bellosta P, Gallant P, Johnston LA. Drosophila myc regulates organ size by inducing cell competition. Cell. 2004;117:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Senoo-Matsuda N, Johnston LA. Soluble factors mediate competitive and cooperative interactions between cells expressing different levels of Drosophila Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18543–18548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709021104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vincent JP, Fletcher AG, Baena-Lopez LA. Mechanisms and mechanics of cell competition in epithelia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:581–591. doi: 10.1038/nrm3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moreno E, Basler K. dMyc transforms cells into supercompetitors. Cell. 2004;117:117–129. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bilder D, Li M, Perrimon N. Cooperative regulation of cell polarity and growth by Drosophila tumor suppressors. Science. 2000;289:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Igaki T, Pagliarini RA, Xu T. Loss of cell polarity drives tumor growth and invasion through JNK activation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wu M, Pastor-Pareja JC, Xu T. Interaction between Ras(V12) and scribbled clones induces tumour growth and invasion. Nature. 2010;463:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature08702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen CL, Schroeder MC, Kango-Singh M, Tao C, Halder G. Tumor suppression by cell competition through regulation of the Hippo pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:484–489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113882109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ohsawa S, Sugimura K, Takino K, Xu T, Miyawaki A, Igaki T. Elimination of oncogenic neighbors by JNK-mediated engulfment in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2011;20:315–328. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vidal M, Larson DE, Cagan RL. Csk-deficient boundary cells are eliminated from normal Drosophila epithelia by exclusion, migration, and apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2006;10:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brumby AM, Richardson HE. scribble mutants cooperate with oncogenic Ras or Notch to cause neoplastic overgrowth in Drosophila. Embo J. 2003;22:5769–5779. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Froldi F, Ziosi M, Garoia F, Pession A, Grzeschik NA, Bellosta P, Strand D, Richardson HE, Pession A, Grifoni D. The lethal giant larvae tumour suppressor mutation requires dMyc oncoprotein to promote clonal malignancy. BMC Biol. 2010;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brumby AM, Goulding KR, Schlosser T, Loi S, Galea R, Khoo P, Bolden JE, Aigaki T, Humbert PO, Richardson HE. Identification of novel Ras-cooperating oncogenes in Drosophila melanogaster: a RhoGEF/Rho-family/JNK pathway is a central driver of tumorigenesis. Genetics. 2011;188:105–125. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.127910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tamori Y, Bialucha CU, Tian AG, Kajita M, Huang YC, Norman M, Harrison N, Poulton J, Ivanovitch K, Disch L, et al. Involvement of Lgl and Mahjong/VprBP in cell competition. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Norman M, Wisniewska KA, Lawrenson K, Garcia-Miranda P, Tada M, Kajita M, Mano H, Ishikawa S, Ikegawa M, Shimada T, et al. Loss of Scribble causes cell competition in mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:59–66. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bondar T, Medzhitov R. p53-mediated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell competition. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Claveria C, Giovinazzo G, Sierra R, Torres M. Myc-driven endogenous cell competition in the early mammalian embryo. Nature. 2013;500:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sancho M, Di-Gregorio A, George N, Pozzi S, Sanchez JM, Pernaute B, Rodriguez TA. Competitive interactions eliminate unfit embryonic stem cells at the onset of differentiation. Dev Cell. 2013;26:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dejosez M, Ura H, Brandt VL, Zwaka TP. Safeguards for cell cooperation in mouse embryogenesis shown by genome-wide cheater screen. Science. 2013;341:1511–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.1241628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]