Abstract

Fast synaptic inhibitory transmission in the CNS is mediated by γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors. They belong to the ligand-gated ion channel receptor superfamily, and are constituted of five subunits surrounding a chloride channel. Their clinical interest is highlighted by the number of therapeutic drugs that act on them. It is well established that the subunit composition of a receptor subtype determines its pharmacological properties. We have investigated positional effects of two different α-subunit isoforms, α1 and α6, in a single pentamer. For this purpose, we used concatenated subunit receptors in which subunit arrangement is predefined. The resulting receptors were expressed in Xenopus oocytes and analyzed by using the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique. Thus, we have characterized γ2β2α1β2α1, γ2β2α6β2α6, γ2β2α1β2α6, and γ2β2α6β2α1 GABAA receptors. We investigated their response to the agonist GABA, to the partial agonist piperidine-4-sulfonic acid, to the noncompetitive inhibitor furosemide and to the positive allosteric modulator diazepam. Each receptor isoform is characterized by a specific set of properties. In this case, subunit positioning provides a functional signature to the receptor. We furthermore show that a single α6-subunit is sufficient to confer high furosemide sensitivity, and that the diazepam efficacy is determined exclusively by the α-subunit neighboring the γ2-subunit. By using this diagnostic tool, it should become possible to determine the subunit arrangement of receptors expressed in vivo that contain α1- and α6-subunits. This method may also be applied to the study of other ion channels.

The γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors are the major inhibitory neuronal receptors in the mammalian brain. They belong to the family of pentameric Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channels that includes nicotinic acetylcholine, glycine, and serotonin type 3 receptors. In human, several GABAA receptor subunit isoforms have been cloned: α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, π, and θ (1–7). Subunit composition of a GABAA receptor determines its pharmacological properties (8). The five subunits are arranged pseudosymmetrically around a central Cl--selective channel (1). The major receptor subtype of the GABAA receptor in the brain most probably consists of α1-, β2-, and γ2-subunits (1, 2, 9–11). The most likely stoichiometry is two α subunits, two β-subunits, and one γ-subunit (12–16). Previous studies (16, 17) on the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor have shown that the subunit arrangement of a functional receptor is γβαβα, counterclockwise when viewed from the synaptic cleft.

A specific GABAA receptor subtype is only then defined properly when it is known where each subunit is positioned in the receptor pentamer. For the characterization of the pharmacological properties of a specific GABAA receptor subtype, it is desirable to be able to specifically locate subunit isoforms. In addition, it is useful to be able to target point mutations to only one of two identical subunits. However, receptor configuration is difficult to control. If a mixture of wild-type and mutant subunits or a mixture of different subunit isoforms are coexpressed, a receptor mixture will be result in either case. To add to the complexity, equal ratios of cRNA coding for α1-, β2-, and γ2-subunits injected in Xenopus oocytes or cDNA coding for α1, β2 and γ2 cotransfected in HEK293 cells have been shown to result in both cases in a mixed population of α1β2 and α1β2γ2 receptors (18, 19). With concatenated subunits, subunit arrangement and stoichiometry are both defined, providing only one type of defined functional receptors (16, 17).

Here, we deal with the question of how receptors perform that contain both the α1- and the α6-subunit. The α1-subunit-containing receptors differ in their pharmacological profile from α6-subunit-containing receptors. These subunit isoforms also differ in their expression pattern. Whereas the α1-subunit is widely expressed in the CNS, expression of the α6-subunit is restricted to cerebellar granule cells and cochlear nuclei. Within cerebellar granule cells, extrasynaptically located α6β2/3δ receptors have been suggested to mediate tonic inhibition, whereas synaptically located α1β2γ2, α6β2γ2, and α1α6β2γ2 receptors are thought to mediate phasic inhibition (20). This suggestion was based on subunit distribution studies by using immunocytochemical techniques with subcellular resolution. In immunobiochemical studies, it has been found that a substantial fraction of α1- and α6-subunits are colocalized in the same pentamer (21–24). Functional evidence for the coexistence of α1- and α6-subunits in the same pentamer has also been presented for receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes (25, 26). By using concatenated receptors, we have expressed defined receptor configurations, γβα1βα1, γβα6βα6, γβα1βα6, and γβα6βα1, and we describe here their pharmacological features. Because all four types of receptor differ in their properties, we provide a diagnostic tool to differentiate them.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Receptor Subunits. The cDNAs coding for the α1-, α6-, β2-, and γ2S-subunits of the GABAA receptor channel have been described elsewhere (16, 27–30). The tandem construct β2-23-α1 (β-α1) and triple construct γ2-26-β2-23-α1 (γ-β-α1) have been described earlier (16, 17). The tandem construct β2-26-α6 (β-α6) and the triple constructs γ2-26-β2-26-α6 (γ-β-α6) were made analogously.

Expression of Linked Constructs in Xenopus Oocytes. Capped cRNAs were synthesized (Ambion, Austin, TX) from the linearized pCMV vectors containing the different single subunits, the tandem or triple constructs, respectively. A poly(A) tail of ≈400 residues was added to each transcript by using yeast poly(A) polymerase (United States Biochemical/Amersham Biosciences, Otelfingen, Switzerland). The concentration of the cRNA was quantified on a formaldehyde agarose gel by using Radiant red stain (Bio-Rad) for visualization of the RNA with known concentrations of RNA ladder (GIBCO/BRL) as standard on the same gel. The cRNAs were dissolved in water and stored at -80°C. Isolation of oocytes from the frogs, culturing of the oocytes, injection of cRNA, and defolliculation were performed as described (31). cRNA coding for one triple concatemer (γ-β-α1 or γ-β-α6) was coinjected in oocytes with cRNA coding for one double concatemer (β-α1 or β-α6), resulting in a total of four concatenated receptor subtypes. Oocytes were injected with 50 nl of the cRNA solution. For cRNA combinations of the triple constructs with the tandem construct, ratios of 10:10 nM were used. The combination of wild type α1-, β2-, and γ2- or α6-, β2-, and γ2-subunits were expressed at a ratio of 10:10:50 nM (18). The combination of wild-type α1β2-subunits was expressed at a ratio of 75:75 nM. The injected oocytes were incubated in modified Barth's solution [10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/88 mM NaCl/1 mM KCl/2.4 mM NaHCO3/0.82 mM MgSO4/0.34 mM Ca(NO3)2/0.41 mM CaCl2/100 units/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin] at 18°C for at least 24 h before the measurements.

Two-Electrode Voltage-Clamp Measurements. All measurements were performed in medium containing 90 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 at a holding potential of -80 mV. GABA (Fluka) was applied for 15–30 sec. The perfusion solution (6 ml/min) was applied through a glass capillary with an inner diameter of 1.35 mm, the mouth of which was placed ≈0.4 mm from the surface of the oocyte. The rate of solution change under our conditions has been estimated 70% within <0.5 sec. Concentration response curves for GABA were fitted with the equation I(c) = Imax/[1 + (EC50/c)n], where c is the concentration of GABA, EC50 the concentration of GABA eliciting half-maximal current amplitude, Imax is the maximal current amplitude, I the current amplitude, and n is the Hill coefficient. Relative current stimulation by diazepam was determined at a GABA concentration evoking 2–5% of the maximal current amplitude in combination with various concentrations of diazepam (DZ; Roche Pharma, Reinach, Switzerland) and expressed as {[I(GABA+DZ)/I(GABA)] - 1}·100. Inhibition curves for furosemide were fitted with the equation I(c) = I (0)/[1 + (IC50/c)n], where I (0) is the control current in the absence of furosemide standardized to 100%, I is the relative current amplitude, c is the concentration of furosemide, IC50 the concentration of furosemide causing 50% inhibition of the current, and n the Hill coefficient. Concentration response curves for piperidine-4-sulfonic acid (P4S) were fitted as those obtained with GABA. Current amplitudes were normalized to the current elicited by 3 mM GABA in the same oocyte.

Data are given as mean ± SD (number of experiments for at least two batches of oocytes). The perfusion system was cleaned between drug applications by washing with 100% DMSO to avoid contamination.

Results

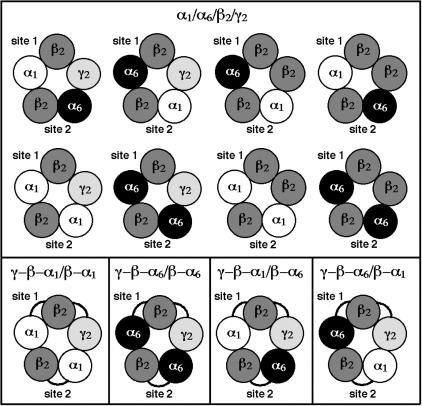

Expression of Receptor Composed of Loose or Concatenated Subunits. Double and triple concatemers were prepared to express γβα1βα1, γβα6βα6, γβα1βα6, and γβα6βα1 receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Thus, the α1- and α6-subunits were linked with β2 to form dual subunit concatemers (β-α1 and β-α6), and the γ2-subunit was linked to the dual subunit concatemers to form the triple subunit concatemers (γ-β-α1 and γ-β-α6). Fig. 1 illustrates the variety of GABAA receptor subtypes with its two agonist-binding sites (site 1 and site 2) that may be expressed in Xenopus oocytes upon coinjection of cRNA coding for loose α1-, α6-, β2-, and γ2-subunits (Upper). Coinjection of loose subunits may lead to expression of eight different receptor subtypes, each of which could display a different set of properties. Previous work on mixed α1/α6 receptors subtypes performed with loose subunits (25, 26) has given evidence that pentameric receptors can contain both α1 and α6 and was difficult to interpret due to the complex receptor mixture. Further complexity will be caused by the fact that the γ2-subunit may or may not be incorporated in the pentamer (18, 19). In contrast to this complexity, coinjection of cRNA coding for specific double and triple concatemers provides the forced expression of a single and defined receptor subtype (Lower) (16, 17). This finding allows physiological and pharmacological studies dissecting the influence of subunit positioning in the pentamer.

Fig. 1.

Possible subunit arrangements of functionally expressed receptors in Xenopus oocytes, resulting from loose (Upper) and concatenated (Lower) α1-, α6-, β2-, and γ2-subunits. Only the γβαβα- or ββαβα-subunit combinations (read anticlockwise) can provide functional GABAA receptors. Eight different receptors can theoretically form upon coinjection of cRNA coding for α1-, α6-, β2-, and γ2-subunits into an oocyte, whereas only one receptor type is formed each upon coinjection of cRNA coding for a defined dual in combination with a defined triple concatenated subunit.

Pharmacology of α1/α6 GABAA Receptor Subtypes. Two-electrode voltage-clamp studies were performed in Xenopus oocytes expressing four different combinations of concatemers, γ-β-α1/β-α1, γ-β-α6/β-α6, γ-β-α1/β-α6, and γ-β-α6/β-α1. The agonist-binding site 1 is formed by the triple subunit concatemer and the agonist-binding site 2 is formed by the double subunit concatemer (Fig. 1).

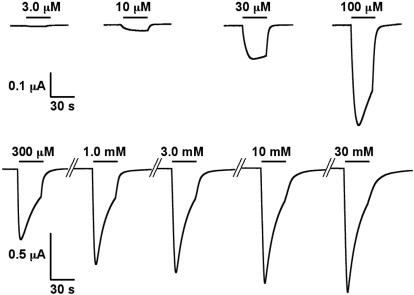

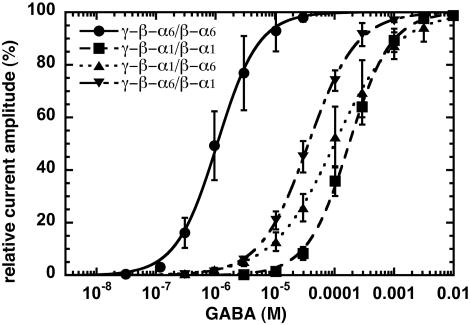

Current traces of the determination of a GABA concentration–response curve in oocytes expressing γ-β-α1/β-α1 is shown in Fig. 2. Averaged GABA concentration–response curves for γ-β-α6/β-α6, γ-β-α1/β-α1, γ-β-α6/β-α1, and γ-β-α1/β-α6 receptors are shown in Fig. 3. A complete evaluation of the data are given in Table 1. Comparison between concatenated (γ-β-α1/β-α1 and γ-β-α6/β-α6) and loose subunit receptors (α1/β2/γ2 and α6/β2/γ2) reveals that the corresponding EC50 for GABA are similar in the case of α6-subunit-containing receptors, whereas in case of the α1-subunit, apparent GABA affinity is ≈4-fold lower for concatenated than for loose subunits (Table 1). Possible reasons for this discrepancy between loose and concatenated α1 receptors will be discussed below. Receptors containing two α6-subunits (γ-β-α6/β-α6) show a >100-fold higher apparent affinity for GABA gating as compared with the receptors containing two α1-subunits (γ-β-α1/β-α1). The two receptor subtypes containing both α1- and α6-subunits (γ-β-α1/β-α6 and γ-β-α6/β-α1) show intermediate apparent affinities but are closer to receptors containing two α1-subunits (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Determination of a GABA concentration–response curve obtained from an oocyte expressing γ-β-α1/β-α1 receptors. The bars indicate the time period of GABA perfusion. GABA concentrations are indicated above the bars.

Fig. 3.

GABA concentration–response curves of γ-β-α6/β-α6 (•), γ-β-α1/β-α1 (▪), γ-β-α6/β-α1 (▪), and γ-β-α1/β-α6 (▴) receptors. Individual curves were first normalized to the observed maximal current amplitude and were subsequently averaged. Mean values ± SD from three to five oocytes from two batches for each subunit combination are shown.

Table 1. Pharmacological properties of receptors composed of concatenated or loose α1-, α6-, β2-, and γ2-subunits.

| GABA

|

P4S

|

Furosemide

|

Diazepam

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50, μM | Hill coefficient | n | EC50, μM | Hill coefficient | Emax, % | n | IC50, μM | Hill coefficient | n | Stimulation, % | n | |

| γ-β-α1/β-α1 | 183 ± 40 | 1.20 ± 0.18 | 3 | 107 ± 8 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 5 ± 1 | 3 | 12,400 ± 6,240 | -1* | 5 | 373 ± 48 | 4 |

| γ-β-α6/β-α6 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.28 ± 0.13 | 4 | 8.3 ± 0.7 | 1.12 ± 0.02 | 44 ± 3 | 3 | 31 ± 5 | -1.31 ± 0.08 | 4 | 5 ± 5 | 3 |

| γ-β-α1/β-α6 | 94 ± 38 | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 4 | 56 ± 4 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 15 ± 4 | 3 | 26 ± 8 | -0.74 ± 0.02 | 4 | 4 ± 6 | 3 |

| γ-β-α6/β-α1 | 42 ± 14 | 1.05 ± 0.10 | 5 | 42 ± 21 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 11 ± 3 | 3 | 37 ± 12 | -0.98 ± 0.05 | 4 | 307 ± 43 | 6 |

| α1/β2 | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | 3† | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 32 ± 3 | 3 | ND | ND | ‡ | ||

| α1/β2/γ2 | 41 ± 18 | 1.39 ± 0.04 | 4† | 57 ± 1 | 1.12 ± 0.02 | 12 ± 4 | 3 | 5,610 ± 2,035 | -1* | 5† | 241 ± 75 | 5§ |

| α6/β2/γ2 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.12 ± 0.19 | 6 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 51 ± 1 | 3 | 38 ± 4 | -1* | 4† | ‡ | |

Summarized are results obtained from GABA and P4S concentration-response curves, furosemide concentration-inhibition curves, and current stimulation by diazepam. P4S Emax, % is the maximal current amplitude elicited by P4S, normalized to the maximal current amplitude elicited by GABA. n, no. of oocytes (from two different batches) ND, not determined. Bold and underlined values point out the key properties of GABAA receptors containing either α1 or α6 or both subunit isoforms in different positions.

Data are fitted with Hill coefficient preset to -1.0

Data are from Sigel and Baur (25)

Lack of benzodiazepine-binding site

Data are from Baumann et al. (17)

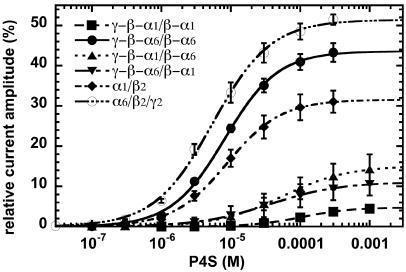

P4S is a partial GABA agonist, its efficacy depending on the receptor subunit isoform composition (26, 32, 33). Efficacy is defined here as maximal current amplitude elicited by P4S as compared with GABA. As in all observations made in Xenopus oocytes, rapid phases of desensitization are missed (see Discussion) and only apparent maximal current amplitudes and therefore apparent efficacies may be determined. Nevertheless, these data may be compared with other data obtained in Xenopus oocytes. Concentration–response curves were performed on concatenated receptor subtypes. Results show that P4S displays high apparent efficacy at γ-β-α6/β-α6 receptors. P4S shows also high apparent efficacy at loose subunit α6/β2/γ2 receptors (Fig. 4), whereas loose α1/β2/γ2 receptors display a low apparent efficacy (Table 1). The lowest apparent efficacy is observed for linked α1-subunit receptors (γ-β-α1/β-α1) that display also the lowest potency. In contrast, loose α1/β2-subunit receptors display a higher apparent efficacy and potency than the loose α1/β2/γ2- and linked α1-subunit receptors (Fig. 4 and Table 1). This observation is interesting in view of the fact that artificial expression of αβγ receptors always results in additional formation of αβ receptors. We observed in our experiments similar relative shifts in EC50 between different receptor subtypes for P4S as those for GABA as agonist. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 4.

P4S concentration–response curves of concatenated γ-β-α6/β-α6 (•), γ-β-α1/β-α1 (▪), γ-β-α6/β-α1 (▪), and γ-β-α1/β-α6 (▴) receptors, and loose α6/β2/γ2 (○) and α1/β2 (♦) receptors. Mean values ± SD from three oocytes from two batches for each subunit combination are shown.

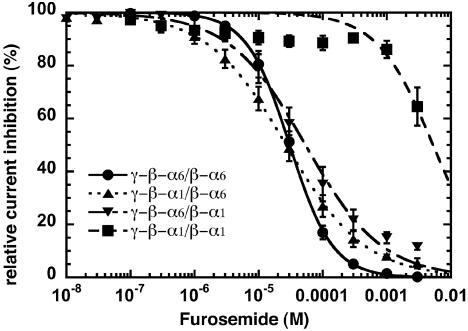

Furosemide is a selective noncompetitive antagonist for α6-containing receptors (34). It leads to an inhibition of currents elicited by GABA with an IC50 in a similar range for the three concatenated receptor subtypes containing one or two α6-subunits (γ-β-α6/β-α6, γ-β-α1/β-α6, and γ-β-α6/β-α1; Fig. 5). The IC50 for furosemide of receptors containing two concatenated α1-subunits (γ-β-α1/β-α1)is ≈400-fold higher than for the three other concatenated receptor subtypes. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 5.

Furosemide concentration–inhibition curves of concatenated γ-β-α6/β-α6 (•), γ-β-α1/β-α1 (▪), γ-β-α6/β-α1 (▪), and γ-β-α1/β-α6 (▴) receptors. Mean values ± SD from four to five oocytes from two batches for each subunit combination are shown.

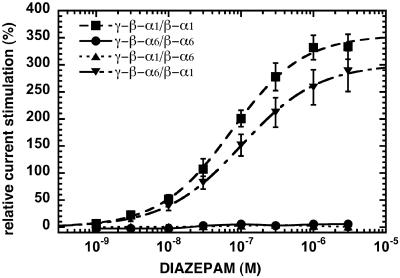

The positive allosteric modulator diazepam, acting at the benzodiazepine-binding site, exclusively stimulated currents elicited by GABA at γ-β-α1/β-α1 and γ-β-α6/β-α1 receptors (Fig. 6). Receptors containing two concatenated α6-subunits (γ-β-α6/β- α6) were insensitive to diazepam as were the receptors containing both α1- and α6-subunits when α6 is neighbored to the γ2-subunit (γ-β-α1/β-α6). The results are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 6.

Diazepam concentration–stimulation curves of concatenated γ-β-α6/β-α6 (•), γ-β-α1/β-α1 (▪), γ-β-α6/β-α1 (▪), and γ-β-α1/β-α6 (▴) receptors. Mean values ± SD from three to six oocytes for each subunit combination are shown.

Model. A model similar to the one presented by Baumann et al. (35) was used to fit the data. Fitting predicted a higher affinity of GABA for site 2 in α6-subunit-containing receptors, as previously observed for α1-subunit-containing receptors. Whereas this preference was ≈3-fold in α1-subunit-containing receptors, it is ≈6-fold in α6-subunit-containing receptors (data not shown).

Discussion

Analysis of concatenated subunit receptors provides a powerful model to elucidate functional properties of defined Cys-loop superfamily ligand-gated ion channel receptors. It allows for example the forced expression of two different subunit isoforms in specified positions. This work shows for the first time, to our knowledge, that the positioning of two different α-subunit isoforms in the pentameric GABAA receptor confers specific pharmacological properties to the receptor. Thus, our results show clearly a functional signature for each γβα1βα6, γβα6βα1, γβα1βα1, and γβα6βα6 GABAA receptor subtypes. We show in addition that a single α6-subunit in the pentamer is enough to confer high furosemide sensitivity, and that the α-subunit isoform neighboring the γ-subunit is the only determinant of the diazepam sensitivity.

First, we evaluated the effect of subunit linkage on receptor function. We observed that the pharmacological profile of the linked α6-subunit receptors (γ-β-α6/β-α6) is very similar to those of the loose α6-subunit receptors (α6/β2/γ2; Table 1). Some discrepancies are observed between the concatenated α1-subunit receptors (γ-β-α1/β-α1) and the loose α1-subunit receptors (α1/β2/γ2). This discrepancy may at least be partially due to a contamination of the α1/β2/γ2-subunit receptors by the α1/β2-subunit receptors that are expressed in oocytes coinjected with cRNA coding for α1-, β2-, and γ2-subunits (18). α1/β2/γ2 receptors display a lower affinity for GABA than α1/β2 receptors (Table 1). Any contamination of α/β/γ receptors with α/β receptors would thus lead to an underestimate of the EC50 for GABA. cRNA coding for concatenated α1-subunits (γ-β-α1/β- α1) coinjected in oocytes avoids this contamination. This discrepancy is not observed with α6-subunit-containing receptors (α6/β2/γ2 and γ-β-α6/β-α6). Injection of cRNA coding for α6- and β2-subunits results in a negligible current expression (25).

Concatenated subunit receptors were also investigated for their response for the partial agonist P4S (Fig. 4). As mentioned in Results, in all observations made in Xenopus oocytes, only apparent maximal current amplitudes and therefore efficacies may be determined. Nevertheless, comparison with other oocyte data is possible. Our results show that γ-β-α6/β-α6 receptors have a higher apparent efficacy than the three other linked receptors, amounting to ≈44%. The two α1α6-concatenated receptors (γ-β-α1/β-α6 and γ-β-α6/β-α1) have a similar apparent efficacy of ≈15% and 11%, whereas the γ-β-α1/β-α1 receptor subtype displays a low apparent efficacy amounting to ≈5%. The latter result is in contradiction with previous studies (26, 33) that reported a higher apparent efficacy for receptors α1/β2/γ2 amounting to 38%. As mentioned above, coexpression of equal ratios of cRNA coding for α1-, β2-, and γ2-subunits in Xenopus oocytes and corresponding cDNAs in HEK293 cells result in a mixed population of α1/β2 and α1/β2/γ2 receptors (18, 19). Thus, it is likely that the high apparent efficacy observed by Ebert et al. (33) and Hansen et al. (26) is due to a substantial contamination of α1/β2/γ2 receptors by α1/β2 receptors, because these receptors showed high apparent P4S efficacy amounting to ≈32%. From our data it may be estimated that even upon expression in Xenopus oocytes of loose α1-, β2-, and γ2-subunits at a ratio of 1:1:5 ≈25% of the expressed current amplitude is mediated by α1/β2 receptors.

We also studied inhibition of the four linked receptor types by furosemide. It has been reported that α6 confers high furosemide sensitivity (34), and that this sensitivity is mainly due to an isoleucine in position 228 of transmembrane domain M1 of this subunit (36). All of the others subunit isoforms (α, β, γ, and δ) except α6 have a threonine in the homologous position. Fig. 5 and Table 1 show that a single isoleucine residue carried by an α6-subunit, irrespective of its position in the pentamer, is sufficient to confer to the receptor a high furosemide sensitivity.

Stimulation by the positive allosteric modulator diazepam was also investigated. Fig. 6 shows that whereas currents elicited by GABA in γβα1βα1 and γβα6βα1 receptors display a large stimulation by diazepam, currents mediated by γβα6βα6 and γβα1βα6 receptors are insensitive to diazepam. This is the first time, again to our knowledge, that it is demonstrated that the benzodiazepine sensitivity of GABAA receptors depends exclusively on the nature of the α-subunit neighboring the γ2-subunit. This observation is relevant for studies in transgenic mice, where one α-subunit isoform is made diazepam-insensitive (37). The respective stimulation observed in the case of loose α1-, β2-, and γ2-subunits again suggests a substantial contribution of channels composed of α1- and β2-subunits only.

It might be hypothesized that linked subunits are being proteolysed during expression. Such an event would complicate interpretation of the results in case the newly liberated subunits retain the ability to reassemble to form functional channels. We consider proteolysis of subunits and subsequent assembly of the proteolytic fragments to form functional ion channels for reasons stated elsewhere (16, 17, 35) and below to be unlikely. For concatenated receptors containing the α6-subunit, lack of proteolysis and reassembly have not been directly shown. The fact that receptors expressed from concatenated subunits γ-β-α1 and β-α6 are completely diazepam-insensitive indicates that they do not reassemble to give γβα1βα1 and γβα6βα1 receptors that are both diazepam-sensitive. On the other hand, receptors expressed from concatenated subunits γ-β-α6 and β-α1 have a similar sensitivity to diazepam as γβα1βα1 receptors, indicating lack of formation of a substantial amount of diazepam-insensitive receptors in this case. Also, we failed to observe biphasic curves in our experiments, as would be expected in the presence of different receptor subtypes. An exception may be inhibition by furosemide, where in one case it might be possible to interpret data as to predict presence of a small second component. In summary, functional considerations exclude major proteolysis followed by reassembly to form functional channels.

It is theoretically possible that one or several subunit(s) of a multisubunit construct do not participate in the formation of the receptor pentamer, but hang out of the receptor. Such a phenomenon would severely complicate the interpretation of the present findings. Evidence for such receptors has been obtained at the structural level in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, but only if tandem constructs were expressed alone. In this case, formation of pentameric receptors is impossible. In addition these receptors were predominantly retained in intracellular compartments (38). We also have observations at the functional level that make formation of such receptors unlikely. As mentioned above, we failed to observe biphasic curves in our experiments, as would be expected in the presence of different receptor subtypes. Also, receptors expressed from concatenated subunits γ-β-α1 and β-α6 are completely diazepam-insensitive and do not rearrange to give γβα1βα1 and γβα6βα1 receptors that are both diazepam-sensitive.

Can our results contribute to an understanding of the role of GABAA receptors in cerebellar granule cells? Based on subcellular immunocytochemistry studies, it has been proposed that phasic neuronal inhibition in these cells may be due to synaptic α1β2γ2, α6β2γ2, and α1α6β2γ2 receptors, whereas the tonic inhibition might be provided predominantly by extrasynaptic α6β2δ receptors (20). Electrophysiological studies on ectopic α6-subunit expressed in hippocampal pyramidal neurons confirm that receptors containing this subunit are involved in tonic neuronal inhibition (39). Different studies have tried to determine the electrophysiological properties of currents measured in cerebellar granule cells (26, 40–43) or in fibroblasts expressing putative cerebellar granule cell receptors (44). Leao et al. (45) have reported that at least after long-term culture, the tonic current component is stimulated ≈85% by flunitrazepam. Because a γ-subunit is required for benzodiazepine sensitivity, it may be estimated from our data that α1-subunit-containing receptors γβα1βα1 or γβα6βα1 contribute to tonic inhibitory current to ≈25%. Because this current component has been reported to be responsive to inhibition by furosemide (42), we propose that this current component is due to γβα6βα1 receptors. There is contradictory information about the effect of 100 μM furosemide on spontaneous synaptic current events in mature granule cells. Tia et al. (46) reported an ≈33% decrease of the spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents, while Wall (42) observed little effect. According to our data, it would have to be postulated in the latter case that phasic inhibition is exclusively mediated by receptors lacking an α6-subunit, i.e., γβα1βα1 receptors. This result is somewhat surprising because immunobiochemical analysis indicates that ≈60% of all cerebellar receptors contain the α6-subunit (24). More work seems required to dissect phasic and tonic inhibitory currents in cerebellar granule cells.

The present study shows that each receptor conformation γβα1βα6, γβα6βα1, γβα1βα1, and γβα6βα6, has its own pharmacological signature. These functional properties are highlighted in Table 1 (bold and underlined values). This study provides a diagnostic tool that may be applied to results of in vivo studies. Concatenated receptors may also be prepared analogously with other GABAA receptor subunits to establish the pharmacological profile for defined pentamers, providing a diagnostic tool for GABAA receptor subtypes of interest. This method may also be applied to study the other members of the Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel receptors that includes nicotinic acetylcholine (47), glycine, and serotonin type 3 receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. V. Niggli for carefully reading the manuscript. This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 3100-064789.01/1.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GABAA, GABA type A; P4S, piperidine-4-sulfonic acid.

References

- 1.Macdonald, R. L. & Olsen, R. W. (1994) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 569-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabow, L. E., Russek, S. J. & Farb, D. H. (1995) Synapse 21, 189-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies, P. A., Hanna, M. C., Hales, T. G. & Kirkness, E. F. (1997) Nature 385, 820-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiting, P. J., McAllister, G., Vassilatis, D., Bonnert, T. P., Heavens, R. P., Smith, D. W., Hewson, L., O'Donnell, R., Rigby, M. R., Sirinathsinghji, D. J., et al. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 5027-5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedblom, E. & Kirkness, E. F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15346-15350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiting, P. J., Bonnert, T. P., McKernan, R. M., Farrar, S., Le Bourdelles, B., Heavens, R. P., Smith, D. W., Hewson, L., Rigby, M. R., Sirinathsinghji, D. J., et al. (1999) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 868, 645-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnard, E. A., Skolnick, P., Olsen, R. W., Möhler, H., Sieghart, W., Biggio, G., Braestrup, C., Bateson, A. N. & Langer, S. Z. (1998) Pharmacol. Rev. 50, 291-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieghart W. & Sperk G. (2002) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2, 795-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurie, D. J., Seeburg, P. H. & Wisden, W. (1992) J. Neurosci. 12, 1063-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benke, D., Fritschy, J. M., Trzeciak, A., Bannwarth, W. & Möhler, H. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 27100-27107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKernan, R. M. & Whiting, P. J. (1996) Trends Neurosci. 19, 139-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backus, K. H., Arigoni, M., Drescher, U., Scheurer, L., Malherbe, P., Möhler, H. & Benson, J. A. (1993) NeuroReport 5, 285-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang, Y., Wang, R., Barot, S. & Weiss, D. S. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 5415-5424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tretter, V., Ehya, N., Fuchs, K. & Sieghart, W. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 2728-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrar, S. J., Whiting, P. J., Bonnert, T. P. & McKernan, R. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10100-10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumann, S. W., Baur, R. & Sigel, E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36275-36280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann, S. W., Baur, R. & Sigel, E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46020-46025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boileau, A. J., Baur, R., Sharkey, L. M., Sigel, E. & Czajkowski, C. (2002) Neuropharmacology 43, 695-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boileau, A. J., Li, T., Benkwitz, C., Czajkowski, C. & Pearce, R. A. (2003) Neuropharmacology 44, 1003-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nusser, Z., Sieghart, W. & Somogyi, P. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 1693-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollard, S., Thompson, C. L. & Stephenson, F. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21285-21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan, Z. U., Gutierrez, A. & De Blas, A. L. (1996) J. Neurochem. 66, 685-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jechlinger, M., Pelz, R., Tretter, V., Klausberger, T. & Sieghart, W. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 2449-2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pöltl, A., Hauer, B., Fuchs, K., Tretter, V. & Sieghart, V. (2003) J. Neurochem. 87, 1444-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigel, E. & Baur, R. (2000) J. Neurochem. 74, 2590-2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen, S. L., Ebert, B., Fjalland, B. & Kristiansen, U. (2001) Br. J. Pharmacol. 133, 539-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lolait S. J., O'Carroll A.-M., Kusano K., Muller J.-M., Brownstein M. J. & Mahan L. C. (1989) FEBS Lett. 246, 145-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lüddens, H., Pritchett, D. B., Kohler, M., Killisch, I., Keinanen, K., Monyer, H., Sprengel, R. & Seeburg, P. H. (1990) Nature 346, 648-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malherbe, P., Draguhn, A., Multhaup, G., Beyreuther, K. & Möhler, H. (1990) Mol. Brain Res. 8, 199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malherbe, P., Sigel, E., Baur, R., Persohn, E., Richards, J. G. & Möhler, H. (1990) J. Neurosci. 10, 2330-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sigel, E. (1987) J. Physiol. (London) 386, 73-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebert, B., Wafford, K. A., Whiting, P. J., Krogsgaard-Larsen, P. & Kemp, J. A. (1994) Mol. Pharmacol. 46, 957-963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebert, B., Thompson, S. A., Saounatsou, K., McKernan, R., Krogsgaard-Larsen, P. & Wafford, K. A. (1997) Mol. Pharmacol. 52, 1150-1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korpi, E. R., Kuner, T., Seeburg, P. H. & Lüddens, H. (1995) Mol. Pharmacol. 47, 283-289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumann, S. W., Baur, R. & Sigel, E. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 11058-11066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson, S. A., Arden, S. A., Marshall, G., Wingrove, P. B., Whiting, P. J. & Wafford, K. A. (1999) Mol. Pharmacol. 55, 993-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudolph, U., Crestani, F. & Mohler, H. (2001) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 22, 188-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou, Y., Nelson, M. E., Kuryatov, A., Choi, C., Cooper, J. & Lindstrom, J. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 9004-9015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wisden, W., Cope, D., Klausberger, T., Hauer, B., Sinkkonen, S. T., Tretter, V., Lujan, R., Jones, A., Korpi, E. R., Mody, I., et al. (2002) Neuropharmacology 43, 530-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathews, C., Bolos-Sy, A. M., Holland, K. D., Isenberg, K. E., Covey, D. F., Ferrendelli, J. A. & Rothman, S. M. (1994) Neuron 13, 149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hevers, H. & Lüddens, H. (2002) Neuropharmacology 42, 34-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wall, M. J. (2002) Neuropharmacology 43, 737-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wall, M. J. (2003) Neuropharmacology 44, 56-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saxena, N. C. & Macdonald, R. L. (1996) Mol. Pharmacol. 49, 567-579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leao, R. M., Mellor, J. R. & Randall, A. D. (2000) Neuropharmacology 39, 990-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tia, S., Wang, J. F., Kotchabhakdi, N. & Vicini, S. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 3630-3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlin, A. (2002) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 102-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]