Abstract

The mechanisms underlying aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder have been poorly understood. The present study has investigated the associations among TNF gene expressions, functional brain activations under the frustrative non-reward task, and aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Baseline gene expressions and aggressive tendencies were measured with the RNA-sequencing and Brief Rating of Aggression by Children and Adolescents (BRACHA), respectively. Our results show that activity levels of left subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (ACG) right amygdala, left Brodmann area 10 (orbitofrontal cortex), and right thalamus were inversely correlated with BRACHA scores and were activated with frustrative non-reward during the affective Posner Task. In addition, eleven TNF related gene expressions were significantly correlated with activation of amygdala or ACG during the affective Posner task. Three TNF gene expressions were inversely correlated with BRACHA score while one TNF gene (TNFAIP3) expression was positively correlated with BRACHA score. Therefore, TNF-related inflammatory cytokine genes may play a role in neural activity associated with frustrative non-reward and aggressive behaviors in pediatric bipolar disorder.

Keywords: tumor necrosis factor, frustrative non-reward, anterior cingulate gyrus, amygdale, prefrontal cortex, RNA-sequencing

1. Introduction

Pediatric-onset bipolar disorder, which is characterized by mood episodes, often initially presents in adolescents (Perlis et al., 2009) and is frequently associated with irritability, impulsiveness, and aggression. A longitudinal prospective study found that episodic irritability in early adolescence (13.8 ± 2.6 years) predicted the emergence of mania in mid-adolescence (16.2 ± 2.8 years)(Leibenluft et al., 2006). Regardless of the severity of identified mood symptoms, pediatric aggression is a common and major public health problem that increases the risks of drug and alcohol abuse, violence in adulthood, suicide, and incarceration while also facing the reiterative path of being both the target and eventual source of abusive parenting (Tremblay et al., 2004). Developing a better understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms underlying aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder may provide novel avenues for developing intervention strategies to reduce aggression.

Inflammatory cytokines have been associated with various psychiatric conditions. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), a cytokine involved in both systemic inflammation and the acute phase reaction, may influence neuronal and neurochemical processes associated with aggression in preclinical and clinical studies (Patel et al., 2010; Suarez et al., 2002). In comparison to mice without mutations, mice with combined deletions of TNF receptor type 1 (TNF-R1) and type 2 (TNF-R2) did not exhibit aggression during a task that typically elicits physical aggression in mice (Patel et al., 2010). A study of 62 healthy men (18 to 45 years old) suggests that hostility and aggression is correlated with the level of expression of TNFα (Suarez et al., 2002). In the latter study, peripheral blood monocyte TNFα expression was measured after stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a general activator of the immune system. LPS-stimulated TNFα expression was positively correlated with physical aggression, verbal aggression, and hostility. In other studies, LPS-induced increases in TNFα correlated with stress-induced emotion arousal,(Moons et al., 2010; Suarez et al., 2006) and interferon-induced labile anger (Lotrich et al., 2010).

Despite the association between TNFα and aggression, to our knowledge, little is known about the relationship between TNFα and aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Serum TNFα levels are found to be higher overall in children than in adults and increase with age between 3 and 14 years old, peak at age 13 to 14 years old, and then significantly decrease in adulthood (Sack et al., 1997). Therefore, research on the link between TNFα and aggression in adolescents needs to factor in age-dependent effects of TNFα levels. Moreover, meta-analysis studies have consistently reported higher concentrations of TNFα in individuals with bipolar disorder (Modabbernia et al., 2013; Munkholm et al., 2013b). Taken together, these findings suggest that TNFα may also play a role in linking aggression and pediatric bipolar disorder.

Prior evidence has suggested that TNFα may mediate the neuroinflammatory process involved in bipolar disorder (Munkholm et al., 2013a). TNFα has been found to be involved in neuroinflammation in several brain regions associated with emotion regulation or impulse control, including amygdala (McAlpine et al., 2009), and prefrontal cortex (Dargahi et al., 2011). Additionally, TNFα may enhance synaptic transmission through increased neurotransmitter release in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a structure in the limbic system associated with impulse control (Jia et al., 2007). With these considerations in mind, we proposed to investigate associations among TNF family gene expressions, functional brain activity in response to frustrative non-reward (i.e., amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and ACC), and aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Our primary hypothesis is that the TNF gene expression of non-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) would correlate with both aggression and brain activations in corticolimbic circuits (with a focus on amygdala, anterior cingulate gyrus (ACG), and orbitofrontal cortex) in adolescents with bipolar disorder.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Ten adolescents aged 12-17 years (15±1 years) (five female/five male) with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder, type I, (DSM-IV-TR criteria) were recruited as part of a larger study examining genetic predisposition in children with bipolar disorder. Clinical diagnoses were confirmed with the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS). The WASH-U-KSADS has established diagnostic and symptom reliability (diagnostic kappa=0.94) (DelBello et al., 2001). Written and informed assent and consent was obtained from the participants and their respective guardians. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC).

2.2. Assessments of aggressive tendencies

The Brief Rating of Aggression by Children and Adolescents (BRACHA) is a valid and reliable 14-item instrument for predicting pediatric inpatient aggression in the psychiatric units (Barzman et al., 2012; Barzman et al., 2011). The BRACHA, which includes assessment items for previous aggression and current impulsiveness, was completed on each study participant. Each of the 14 BRACHA items has a range of scores from 0 (negative for the risk factor) to 1 (positive for the risk factor).

2.3. Neuroimaging

Following the screening, all subjects underwent brain scans with a 4.0 Tesla Varian Unity INOVA Whole Body MRI/MRS system (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA) located at the Center for Imaging Research at the University of Cincinnati. To provide anatomical localization for activation maps, a high-resolution, T1 -weighted, 3-D brain scan was obtained using a modified driven equilibrium Fourier transform (MDEFT) sequence after which a multi-echo reference scan was obtained (Lee et al., 1995). A midsagittal localizer scan was acquired to place 30 contiguous 5 mm axial slices to encompass the entire brain. Next, a multi-echo reference scan was obtained to correct for ghost and geometric distortions (Schmithorst et al., 2001). Subjects completed the fMRI session in which whole-brain images (volumes) were acquired every 2 seconds while performing the continuous processing affective Posner task (described below) (Rich et al., 2011) using a T2-weighted gradient-echo echoplanar imaging (EPI) pulse sequence. Visual stimuli were presented using high-resolution video goggles (Resonance Technologies, Inc., Northridge, California).

2.4. General image processing

The fMRI data were evaluated using Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI) (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni(Cox, 1996; Cox and Hyde, 1997) Magnetic resonance images were reconstructed to convert raw scanner data into AFNI format. Structural and echo-planar (functional) images were co-registered based upon scanner coordinates. Subject motion was determined in six directions of rotation and translation, and the maximum motion of any analyzed subject was <5 mm. Additionally, each volume was inspected for signal artifacts using a semi-automated algorithm in AFNI and excluded from further analysis if uncorrectable head movement occurred. Anatomical and functional maps were transformed into stereotactic Talairach space using the International Consortium for Brain Mapping 452 template (Laboratory of NeuroImaging, University of California-Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California).

2.5. Voxel-Wise Analyses

Individual voxel-wise event-related activation maps were created following standard AFNI procedures using an algorithm that compares the actual hemodynamic response to a canonical hemodynamic response function. Event-related response functions were calculated. Cubes provided the baseline against which hemodynamic responses were assessed. A voxel-wise statistical analysis was performed to identify regions that exhibited significant interactions.

2.6. Frustrative non-reward task: affective Posner task

During the fMRI scan, participants performed a spatial selective attention task modified to provoke negative emotions. This affective “Posner task” was designed to induce frustration by the use of rigged negative performance feedback. The affective Posner task has been used to study irritability, a marker of reactive aggression by adolescents with bipolar disorder (Leibenluft et al., 2003; Rich et al., 2011). Our version of the task was designed based on these prior publications. The task is divided into three parts, with 50 trials in part 1 (sincere feedback, no monetary reward), 50 trials in part 2 (sincere feedback, monetary reward for correct performance, monetary punishment for errors), and 50 trials in part 3 (rigged feedback). An individual trial is comprised of several events. First a black fixation cross appears in the center of the computer screen flanked by two empty boxes outlined in black, which alerts the subject to the beginning of a trial. Next either the left or right box is momentarily flashed with interior blue interior. Following this peripheral box-brightening cue, a black circle appears momentarily in either the left or right box. The subject's task is to press a button in response to the position of the circle on the left or right. Performance feedback is presented following the response on each trial. Participants respond by pressing the left or right button on a button box held in the right hand using the index or middle finger, respectively. After a variable delay performance feedback is provided. Performance feedback is systematically manipulated over the course of the three runs to increase arousal and induce frustration. In part 1, feedback consists of the word “correct” after accurate responses and “incorrect” after errors or responses that were longer than a certain amount of msec. In part 2 the words “correct” and “incorrect” were accompanied by a monetary reward or punishment (+ or − $0.10) with the objective of inducing arousal about performance. At the end of part 2 subjects were told that they had responded too slowly and would have to repeat part 2. In fact, we then conducted part 3, and rigged the feedback to induce frustration in addition to arousal. In part 3 ∼50% of correct trials received “correct” feedback and a reward of +$0.10. The other roughly 50% of correct trials received “too slow” as feedback and a monetary penalty of −$0.10. All response errors received “incorrect” and a penalty of $0.10. Responses that were slower than a certain amount of msec received “too slow” and a monetary penalty.

During practice and performance of the task, participants were told to work as quickly and accurately as possible and that the computer would inform them that their answers were either “correct” or “incorrect.” In addition they were told that they would be paid according to their performance. In addition, participants were asked to rate their subjective emotions using a self-assessment manikin (SAM) method (Bradley and Lang, 1994). The SAM process was conducted before and after each part of the fMRI task. The SAM ratings are based on personal assessment of one's feelings relative to three different visual scales. The scales are not explicitly described to the subject, but they have graphical representations of emotional states. The subject places a cursor in a position relative to the range of emotions displayed that best represents how they are feeling. The positions of the cursor placements are recorded in order to assess arousal and frustration levels before and after each part of the fMRI task. Participants received compensation of 50 U.S. dollars regardless of their performance during the task but participants did not know this during the tasks.

2.7. Gene expression analysis

Blood samples were collected before the fMRI under frustration non-reward tasks. The mRNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). mRNA was extracted from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells using the Invitrogen ™ Ribopure kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. The purpose of RNA-seq here is to investigate the correlation between baseline gene expression levels and baseline aggressive tendencies (measured with the BRACHA score) as well as brain activities in response to frustrative non-reward. RNA-seq consisted of three primary steps as follows:

RNA-Seq library construction: Using TruSeq RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina), total RNA with RNA integrity number (RIN, Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer) ≥7.0 was converted into a library of template molecules suitable for subsequent cluster generation and sequencing by Illumina HiSeq. Briefly, poly-A mRNA was extracted and fragmented into smaller pieces (∼140 nt). The cleaved RNA fragments were converted to first strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers, followed by second strand synthesis using polymerase I and RNAse H. The cDNA fragments then went through end repair, addition of a single ‘A’ base, ligation of adapters and indexed individually. The products were purified and enriched by PCR to create the final cDNA library. The generated library was validated and quantified by using Kapa Library Quantification kit (Kapabiosystem).

Cluster Generation and HiSeq Sequencing: Six individually indexed cDNA libraries were equal amount pooled for clustering in cBot system (Illumina). Libraries were clustered onto a flow cell using Illumina's TruSeq SR Cluster Kit v3, and sequenced for 50 cycles using TruSeq SBS kit on Illumina HiSeq system.

Bioinformatic analysis: Sequence reads were aligned to the genome by using standard Illumina sequence analysis pipeline, which were analyzed by the Statistical Genomics and Systems Biology core in the University of Cincinnati. All gene expression level in RNA samples were presented as normalized fold changes. Fold changes of mRNA were measured using the target mRNA levels compared to the reference genome.

RNA sequencing: We evaluated the impact of baseline TNF family gene expressions on aggressive tendencies and brain activity in response to frustrative non-reward. We used a linear regression model with relative mRNA level as the independent variable and BRACHA score/brain activity level as the dependent variable. Two-sided alpha values were adopted to evaluate the significance level corresponding to the genetic effect on aggression tendencies and brain activity. Since this is an exploratory study, we did not implement multi-testing corrections to identify significant association findings. Prior studies have suggested that an inflated familywise error rate (FWER) due to a lack of multi-testing corrections may be acceptable in an exploratory study, since the hypothesis would need to be addressed a priori and cannot be discerned by any a posteriori analysis (Goeman and Solari, 2014; Stacey et al., 2012).

3. Results

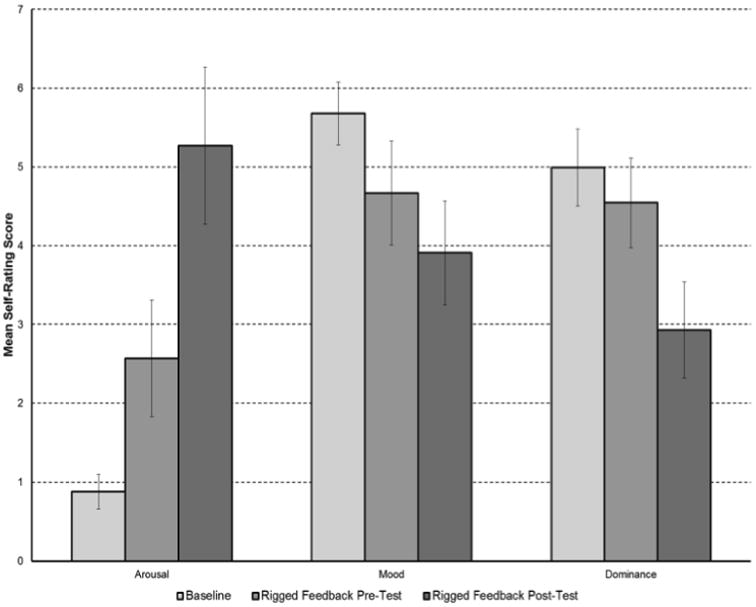

BRACHA scores for participants ranged from 3.5-12 with an average score of 6.55. Most of the 14 questions on the BRACHA were related to affective aggression while only two questions were related to predatory aggression. Fig 1 indicated the affective Posner task significantly increased arousal (frustration) while significantly decreasing emotion arousal (valence) and dominance (control) based on self-ratings – the three constructs of emotion measurements are based on the method proposed by Bradley and Lang (Bradley and Lang, 1994).

Figure 1. Changes in Arousal, Mood, and Dominance with the Affective Posner Task based on Self-Ratings.

The voxel-wise analysis revealed increased activation of the left superior anterior cingulate gyrus (p=0.028) and the right superior anterior cingulate gyrus (p = 0.05), during part 3 (rigged feedback post-test with frustrative non-reward) relative to baseline. The BRACHA scores were inversely correlated with activation in the left subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (p = 0.024) during part 3 (rigged feedback post-test with frustrative non-reward) relative to baseline. The BRACHA scores were inversely correlated with the following regions when subtracting part 2 (rigged feedback pre-test with incentive to win money) from part 3 (rigged feedback post-test with frustrative non-reward): right amygdala (p=0.025), left Brodmann area 10 (p = 0.029), and the right thalamus (p = 0.039). This subtraction isolates the frustration component since part 2 and part 3 differ by the level of frustration.

Increased activation of the right amygdala (p =0.047) occurred during part 2 when participants were rewarded with money. We identified several significant association findings between activations of amygdala or ACG and TNF gene expressions (p < 0.05) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Correlations between TNF Gene Expression Levels and Functional Brain Activations during the Affective Posner Task.

| Gene | Brain Region | p Level |

|---|---|---|

| TNFRSF21 | Left Amygdala | p = 0.008 |

| TNFRSF25 | Left Amygdala | p = 0.022 |

| TNFSF13B | Left Amygdala | p = 0.031 |

| TNFAIP1 | Left Amygdala | P = 0.034 |

| TNFRSF | Right Subgenual ACG | p = 0.022 |

| TNFAIP3 | Right Anterior ACG | P = 0.027 |

| TNFSF15 | Right Anterior ACG | p = 0.047 |

| TNFRSF4 | Left Anterior ACG | p = 0.004 |

| TNFRSF10B | Left Anterior ACG | p = 0.018 |

| TNFAIP2 | Left Anterior ACG | p = 0.045 |

| TNFSF12 | Left Anterior ACG | p = 0.048 |

Table 2. Correlations between TNF Gene Expression Levels and BRACHA scores.

| Gene | Slope | p Level |

|---|---|---|

| TNFSF12 | -2.02 | p = 0.008 |

| TNFSF13 | -12.55 | p = 0.009 |

| TNFAIP8L2 | -0.55 | p = 0.018 |

| TNFAIP3 | 16.95 | P = 0.049 |

4. Discussion

Our findings are consistent with previous evidence that suggests that amygdala, ACG, and orbitofrontal cortex, are involved in the pathway to aggression (Goyer et al., 1994, Gregg and Siegel, 2001, Harmon-Jones and Sigelman, 2001, Leibenluft et al., 2003, Wozniak et al., 2012). The present study provides preliminary evidence in support our hypothesis that the TNF pathway gene expression correlates with both brain activations in amygdala, ACG, and orbitofrontal cortex and aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the TNF pathway and the neural circuitry related to aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Our results indicate that activity of left subgenual ACG, right amygdala, left Brodmann area 10 (from the orbitofrontal cortex), and right thalamus were inversely correlated with BRACHA scores and were activated with frustrative non-reward during the affective Posner Task. In addition, eleven TNF related gene expressions were significantly correlated with activation of amygdala or ACG during the affective Posner task. Three TNF gene expressions were inversely correlated with the BRACHA score while one TNF gene (TNFAIP3) expression was positively correlated with BRACHA score. Interestingly, TNFAIP3 was the only gene with expression that was both significantly correlated to both the BRACHA score and one of the regions of interest (right anterior ACG) during the affective Posner task. TNFAIP3 has been found to exert an anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effect in response to neuroinflammation (Yu et al., 2006). Our findings also suggest other pro-inflammatory TNF family genes were more highly expressed in individuals with higher aggression tendencies. Taken together, our preliminary evidence suggests that TNF family genes that encode either anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory cytokines may serve as biomarkers for aggressive tendencies.

One of the limitations of the current study is the limited sample size, which causes our limited capacity to address the multi-testing issue due to the small sample size. However, multi-testing corrections might lead to false negatives under a small sample size and highly correlated predictors (i.e., genes in the same pathway and brain structure in the associated circuit). We, therefore, did not employ multi-testing corrections to adjust the type-I errors for the imaging or genetic results in this exploratory study. Although we have used RNA-seq to investigate gene expressions, our goal is to take advantage of the information derived from the next-generation sequenced data while focusing on a few candidate genes according to our a priori hypothesis. Therefore, as the a priori probabilities of the TNF gene expressions associated with our target phenotypes might be greater than other genes, we assume that an unadjusted p-value may appropriately help us prioritize the candidate genes in the TNF pathway based on our exploratory findings.

Another limitation of this study is the source of gene expressions. mRNA levels derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) might not correlate with gene expressions in the central nervous system. However, one study reports that 19 inflammatory gene mRNA levels from PBMCs could distinguish patients with bipolar disorder from controls (Padmos et al., 2008) and clinical features or treatment responses in some neurological diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (Hong et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2007). Therefore, we speculate that PBMC inflammatory gene expressions might serve as systemic biomarkers for behavioral traits such as aggression.

In conclusion, our results establish the feasibility of evaluating the relationships among neural circuitry under frustrative non-reward tasks, TNF pathway expression, and aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Our findings are consistent with the role of TNF alpha in aggression and encourage larger follow-up studies to further elucidate the relationships between the TNF pathway, corticolimbic circuit activation, and aggression in adolescents with bipolar disorder. The findings may elucidate biomarkers that identify aggressive tendencies in adolescents with bipolar disorder, and help to identify the molecular and central mechanisms underlying aggression.

Research Highlights.

Cortico-limbic system activities under frustrations were associated with aggressive levels.

TNF-related gene pathway was correlated with amygdale activities under frustrations.

TNF-related gene pathway was also correlated with aggressive levels.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by Oxley Foundation (D.B. and P.L.), Center of Clinical and Translational Science Training (CCTST) of University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and National Institute of Health (NIH). Specifically, the study was supported by NIH grants, including NIMH R01 MH080973 (M.D.), NIMH R34 MH083924 (R.N.), and NIMH R01 MH078043 (C.A.). We greatly appreciate the patients who participated in the study. None of the co-authors have any financial disclosures to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barzman D, Mossman D, Sonnier L, Sorter M. Brief Rating of Aggression by Children and Adolescents (BRACHA): a reliability study. The journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2012;40:374–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzman DH, Brackenbury L, Sonnier L, Schnell B, Cassedy A, Salisbury S, Sorter M, Mossman D. Brief Rating of Aggression by Children and Adolescents (BRACHA): development of a tool for assessing risk of inpatients' aggressive behavior. The journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2011;39:170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Measuring emotion: the Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and biomedical research, an international journal. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Hyde JS. Software tools for analysis and visualization of fMRI data. NMR in biomedicine. 1997;10:171–178. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199706/08)10:4/5<171::aid-nbm453>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargahi L, Nasiraei-Moghadam S, Abdi A, Khalaj L, Moradi F, Ahmadiani A. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 activity precedes the COX-2 induction in Abeta-induced neuroinflammation. Journal of molecular neuroscience: MN. 2011;45:10–21. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Soutullo CA, Hendricks W, Niemeier RT, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM. Prior stimulant treatment in adolescents with bipolar disorder: association with age at onset. Bipolar disorders. 2001;3:53–57. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeman JJ, Solari A. Tutorial in biostatistics: multiple hypothesis testing in genomics. Statistics in medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/sim.6082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Zang YC, Hutton G, Rivera VM, Zhang JZ. Gene expression profiling of relevant biomarkers for treatment evaluation in multiple sclerosis. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2004;152:126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Gao GD, Liu Y, He SM, Zhang XN, Zhang YF, Zhao MG. TNF-alpha involves in altered prefrontal synaptic transmission in mice with persistent inflammatory pain. Neuroscience letters. 2007;415:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Garwood M, Menon R, Adriany G, Andersen P, Truwit CL, Ugurbil K. High contrast and fast three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging at high fields. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34:308–312. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Blair RJ, Charney DS, Pine DS. Irritability in pediatric mania and other childhood psychopathology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1008:201–218. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Cohen P, Gorrindo T, Brook JS, Pine DS. Chronic versus episodic irritability in youth: a community-based, longitudinal study of clinical and diagnostic associations. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2006;16:456–466. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrich FE, Ferrell RE, Rabinovitz M, Pollock BG. Labile anger during interferon alfa treatment is associated with a polymorphism in tumor necrosis factor alpha. Clinical neuropharmacology. 2010;33:191–197. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181de8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine FE, Lee JK, Harms AS, Ruhn KA, Blurton-Jones M, Hong J, Das P, Golde TE, LaFerla FM, Oddo S, et al. Inhibition of soluble TNF signaling in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease prevents pre-plaque amyloid-associated neuropathology. Neurobiology of disease. 2009;34:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modabbernia A, Taslimi S, Brietzke E, Ashrafi M. Cytokine alterations in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of 30 studies. Biological psychiatry. 2013;74:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons WG, Eisenberger NI, Taylor SE. Anger and fear responses to stress have different biological profiles. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2010;24:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkholm K, Brauner JV, Kessing LV, Vinberg M. Cytokines in bipolar disorder vs. healthy control subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of psychiatric research. 2013a;47:1119–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkholm K, Vinberg M, Vedel Kessing L. Cytokines in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders. 2013b;144:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmos RC, Hillegers MH, Knijff EM, Vonk R, Bouvy A, Staal FJ, de Ridder D, Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Drexhage HA. A discriminating messenger RNA signature for bipolar disorder formed by an aberrant expression of inflammatory genes in monocytes. Archives of general psychiatry. 2008;65:395–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, Siegel A, Zalcman SS. Lack of aggression and anxiolytic-like behavior in TNF receptor (TNF-R1 and TNF-R2) deficient mice. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2010;24:1276–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Dennehy EB, Miklowitz DJ, Delbello MP, Ostacher M, Calabrese JR, Ametrano RM, Wisniewski SR, Bowden CL, Thase ME, et al. Retrospective age at onset of bipolar disorder and outcome during two-year follow-up: results from the STEP-BD study. Bipolar disorders. 2009;11:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich BA, Carver FW, Holroyd T, Rosen HR, Mendoza JK, Cornwell BR, Fox NA, Pine DS, Coppola R, Leibenluft E. Different neural pathways to negative affect in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. Journal of psychiatric research. 2011;45:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MK, Scott TF, LaFramboise WA, Hu FZ, Post JC, Ehrlich GD. Gene expression changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from multiple sclerosis patients undergoing beta-interferon therapy. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2007;258:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey AW, Pouly S, Czyz CN. An analysis of the use of multiple comparison corrections in ophthalmology research. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2012;53:1830–1834. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez EC, Boyle SH, Lewis JG, Hall RP, Young KH. Increases in stimulated secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by blood monocytes following arousal of negative affect: the role of insulin resistance as moderator. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2006;20:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez EC, Lewis JG, Kuhn C. The relation of aggression, hostility, and anger to lipopolysaccharide-stimulated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha by blood monocytes from normal men. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2002;16:675–684. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Seguin JR, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo PD, Boivin M, Perusse D, Japel C. Physical aggression during early childhood: trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e43–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Miao H, Hou Y, Zhang B, Guo L. Neuroprotective effect of A20 on TNF-induced postischemic apoptosis. Neurochemical research. 2006;31:21–32. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-9004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]