Abstract

Hippocampal adult neurogenesis contributes to key functions of the dentate gyrus, including contextual discrimination. This is due, at least in part, to the unique form of plasticity new neurons display at a specific stage of their development compared to surrounding principal neurons. In addition, the contribution newborn neurons make to dentate function can be enhanced by an increase in their numbers induced by a stimulating environment. However, signaling mechanisms that regulate these properties of newborn neurons are poorly understood. Here we show that Ras-GRF2 (GRF2), a calcium-regulated exchange factor that can activate Ras and Rac GTPases, contributes to both of these properties of newborn neurons. Using Ras-GRF2 knockout mice and wild-type mice stereotactically injected with retrovirus containing shRNA against the exchange factor, we demonstrate that GRF2 promotes the survival of newborn neurons of the dentate gyrus at ∼ 1-2 weeks after their birth. GRF2 also controls the distinct form of LTP that is characteristic of new neurons of the hippocampus through its effector Erk Map kinase. Moreover, the enhancement of neuron survival that occurs after mice are exposed to an enriched environment also involves GRF2 function. Consistent with these observations, GRF2 knockout mice display defective contextual discrimination. Overall, these findings indicate that GRF2 regulates both the basal and environmentally-induced increase in newborn neuron survival, as well as in the induction of a distinct form of synaptic plasticity of newborn neurons that contributes to distinct features of hippocampus–derived learning and memory.

Keywords: synaptic plasticity, Erk Map kinase, Ras, adult neurogenesis, LTP

Introduction

New neurons are continually generated throughout adulthood in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (Altman and Das, 1965; Altman and Das, 1967; Alvarez-Buylla and Lim, 2004). Newborn cells derived from stem cells first proliferate then differentiate over a period of ∼ 6-8 weeks. However, before they fully mature, new neurons display a period of enhanced excitability that can be measured as a distinct form of LTP that is thought to contribute unique features to the circuit containing fully developed neurons (Schmidt-Hieber et al., 2004; Snyder et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2000). As such, it contributes to the well-known contribution of adult neurogenesis to an animal's ability to perform pattern separation, which is involved in contextual discrimination learning (Aimone and Gage, 2011; Clelland et al., 2009; Kheirbek et al., 2012a; Sahay et al., 2011b).

The rate of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus can be regulated by altering either the proliferation rate of neural precursor stem cells or the survival of partially differentiated cells. For example, antidepressants enhance the rate of neurogenesis, which is hypothesized to be one of their mechanisms to enhance mood (Santarelli et al., 2003); (Sahay and Hen, 2007). In addition, an enriched environment can enhance proliferation and survival of new neurons (van Praag et al., 2000); Tashiro et al., 2007), which improves pattern separation (Sahay et al., 2011a).

The biochemical regulators for each of the phases of adult neurogenesis are not completely defined. Ras-GRF1(GRF1) and Ras-GRF2(GRF2) constitute a family of calcium-activated guanine nucleotide exchange factors that are expressed in neurons throughout the central nervous system and have the capacity to activate both RAS and RAC GTPases (Feig, 2011). They regulate synaptic plasticity in the CA1 hippocampus in an age-dependent manner (Tian and Feig, 2006; Tian et al., 2004). In particular, beginning at ∼1-month of age, when the hippocampus first begins to contribute to learning and memory, GRF1 mediates LTD in the CA1 hippocampus that is induced by NMDA-type glutamate receptors (NMDA-Rs) containing NR2B regulatory subunits. In contrast, GRF2 mediates LTP in the CA1 hippocampus that is induced by NMDA-Rs that contain NR2A regulatory subunits through its ability to activate Erk Map kinase (Li et al., 2006); (Jin and Feig, 2010; Li et al., 2006). At 2-months of age, GRF1 begins to contribute to LTP mediated by calcium-permeable AMPA receptors (CP-AMPA-Rs) in the CA1 region through its ability to activate p38 Map kinase (Jin et al., 2013). GRF1 has also been shown to promote adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus beginning at 2-months of age by promoting cell survival (Darcy et al., 2013). Together, these two functions of GRF1 likely contribute its role in promoting contextual discrimination (Giese et al.,. 2001; Jin et al., 2013).

In this study, we show that GRF2 also contributes to the function of the dentate gyrus by promoting the late stage survival of new hippocampal neurons during adult neurogenesis, but in a way that is different than GRF1. GRF2 also mediates the induction of the distinct form of LTP that occurs in young neurons and the enhancement of neurogenesis induced by an enriched environment. These functions likely explain at least in part, the observation that GRF2-KO mice display impaired contextual discrimination.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Ras-Grf2 homozygous knockout ( Grf2 KO) mice and WT littermate mice, generated previously ((Giese et al., 2001)(Tian et al., 2004) and backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background for more than 10 generations, were used in this study. All mice were housed in a temperature and light-controlled colony room (12-h light/dark cycle) with food and water ad libitum.

Materials

The following antibodies were used: Doublecortin (Santa Cruz; sc-8066; 1:500), BrdU (Accurate Chemical and Scientific; OBT0030; 1:400), Ki-67 (BioCare Medical; CRM325A; 1:500), GFP (Abcam; ab13970; 1:1000), pERK 42/44 (Cell Signaling; 9106S; 1:1000). DAPI (Sigma; D9542; 1:10,000) or Nuclear Fast Red (Vector Labs; H3403) were used to counterstain for nuclei. 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma; B9285) was used for labeling newborn neurons. 3-3′-diaminobenzadine (DAB)-based staining kits were purchased from Vector Labs (Elite ABC Kit, PK-7100; Peroxidase Substrate Kit; SK-4100). The plasmid encoding for GRF2 miRNA (pSM2c) and the MSCV-based retrovirus vector was purchased from Open Biosystems (cat # EAV 4679). Retro-X Concentrator reagent was purchased from Clontech (cat # 631455).

BrdU injections

For cell survival experiments, 1-month (young adult; WT n = 13 and Grf2 KO n=10) or 2-month (adult; WT n = 10 and Grf2 KO n=12) old mice received two intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections (50 mg/kg in 0.9% NaCl,8 hours apart) over 3 days. Animals were perfused at either 1 week (early survival; 1mo+1week: WT n = 6 and GRF2-KO n = 5; 2mo+1week: WT n = 5 and Grf2 KO n = 5) or 4 weeks (long term survival; 1mo+4weeks: WT n = 7 and Grf2-KO n = 5; 2mo+4weeks: WT n = 5 and Grf2 KO n = 7) after the last BrdU injection.

Environmental enrichment

2-month old wild-type or GRF2 KO mice (N=5 per cage) were injected with BrdU as described above and exposed to an enriched environment (EE) consisting of various length tubes, housing toys, and a running wheel(See Figure 5A). The effects of EE on new neuron survival was assessed as previously described (Tashiro et al., 2007). Briefly, following BrdU injections, all mice were kept in their home cage for one week. Enriched mice were placed into the EE cage for an additional week and then returned to a home cage for an additional 2 weeks before being sacrificed and brains processed for BrdU immunohistochemistry as described.

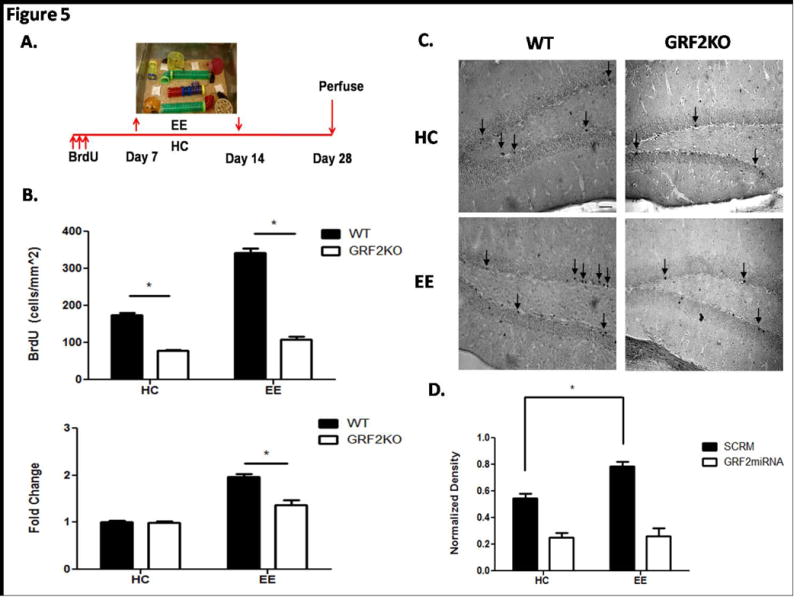

Figure 5. Enhanced survival of newborn cells from environmental enrichment is blocked in GRF2-KO mice.

A. 2-month old wild-type and Grf2-KO mice were injected with BrdU and placed into an enriched environment 1 week after injection. Animals were allowed 1 week of exposure to the enriched environment and placed back in their home cage for an additional 2 weeks for a total time of 4 weeks after BrdU injection. The experimental design for enrichment is based on a previous study describing a critical period for enrichment-induced survival (Tashiro et al., 2007). B. Top: Quantification of BrdU labeled cells reveals a significant increase in cell survival in enriched wild-type mice compared to enriched Grf2-KO mice (Genotype × Condition, F1,16 = 72.55, p < 0.0001; EE, t = 20.37, p < 0.001). Bottom: Cell survival is enhanced 1.96 fold in wild-type enriched mice compared to 1.37 fold in Grf2-KO mice (Genotype × Condition, F1,16 = 19.72, p < 0.001; EE, t = 6.28, p < 0.001). Graphs show mean ± s.e.m. C. Representative images of BrdU positive cells for WT or Grf2-KO mice in homecage (HC) or enriched environment (EE) conditions. Scale bar = 50μm D. Intrinsic knockdown of GRF2 in newborn cells blocks enrichment-induced survival. Retroviral injections of either SCRM or GRF2miRNA into the DG of 2-month old wild-type mice followed by the enrichment protocol revealed a defect in survival enhancement with GRF2 knockdown but not with a scrambled miRNA (Virus × Condition, F1,12 = 6.9, p < 0.5, SCRM HC vs EE, t = 4.91, p < 0.05; GRF2miRNA HC vs EE, t = 0.84, p = 0.44).

Tissue preparation and sectioning

All mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA 4%) dissolved in PB 0.1M. Brains were extracted and post-fixed in PFA 4% for 24 h. Brains were transferred to 30% sucrose for 48–72 h before slicing 30 μm coronal sections through the extent of the hippocampus using a cryostat. Sections were stored in cryoprotectant at -20°C until use.

Retrovirus preparation, stereotactic injection, and analysis

Preparation

An MSCV-based, VSV-G pseudotyped, LTR-driven retrovirus containing an internal IRES site for expression of GFP (LMP-GFP, Open Biosystems) was prepared as previously described (Tashiro et al., 2006b) with minor modifications. For the creation of the retroviruses encoding for GRF2miRNA (LMP-GRF2mi-GFP) or the scrambled miRNA (SCRM), the hairpin sequence (GRF2 miRNA: 5′ TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGCGCTGATCAATATCTACAGAAATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATTTCTGTAGATATTGATCAGCTTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA 3′, sense in bold, SCRM: 5′ TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGCGACTAATCGCCGAATAATTAATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATTAATTATTCGGCGATTAGTCGCTTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA 3′ was cut from the pSM2c vector and inserted into the cloning site of LMP-GFP using EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites according to manufacturer's instructions. Following retrovirus production; collection, amplification, and purification of the virus was performed using Retro-X Concentrator reagent according to manufacturer's instructions. In brief, viral supernatant was collected at 48 and 72 hours after transfection. Supernatant was centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min and filtered through a 0.45μm low protein binding PVDF membrane. 1 volume Retro-X Concentrator reagent was added to 3 volumes viral supernatant and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the sample was centrifuged for 45 minutes at 1,500 × g at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 1:100 of the original supernatant volume using sterile PBS. Titering was performed as described (Tashiro et al., 2006b). Retroviral stocks used for in vivo experiments were similarly concentrated at 1e7 units/mL.

Stereotactic Injection

2-month old male C57Bl/6J mice housed under standard conditions were used for stereotactic injections of retrovirus into the dentate gyrus (DG) region of the hippocampus as described (Gu et al., 2011). DG was targeted (anterioposterior = -2.0 mm from bregma; lateral = ± 1.6mm; ventral = -2.5mm; anterioposterior = -3.0mm from bregma; lateral = ±2.5mm; ventral = -3.2mm) using a stereotaxic frame (BENCHmark). LMP-GFP and LMP-GRF2mi-GFP viruses (1.5ul per site, 0.25ul/min of rate) were injected in the left and right DG, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Free-floating sections were rinsed extensively in Phosphate Buffer Saline with 0.25% Triton X-100 (PBS-T). Sections were blocked for 1h at room temperature in PBS-T with 5% normal goat serum (or 3% donkey serum for DCX). For each marker every 12th section (360um spacing) was processed through the rostrocaudal extent of the dentate gyrus.

DCX

Primary antibodies were diluted in the blocking solution, incubated overnight at 4°C, and rinsed 3 times for 15 minutes in PBS-T before application of secondary antibodies (AlexaFluor 594, Invitrogen)

Ki-67

Sections were incubated overnight in primary antibody followed by incubation in appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies (Vector Labs, 1:400-1:1000) for 90 minutes, rinsed in PBST before incubating in avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex solution for an additional 90 minutes. Sections were rinsed in PBST and developed for 10 min in DAB solution, rinsed in PBST-Azide to stop the reaction, and mounted on slides. Slides were taken through a series of dehydration washes, counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red and coverslipped.

BrdU

Sections were denatured in 2N HCl for 50 minutes at room temperature and then neutralized twice in 0.1M borate buffer, pH 8.5, rinsed again in PBST, blocked in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBST for 1 hour, and incubated overnight at 4°c in a mixture of rat anti-BrdU antibody in PBST + 5% normal serum. The following day, sections were incubated for 1.5h at room temperature in secondary reagents (Jackson ImmunoResearch): goat anti-rat Cy3 (1:2000)in PBST + 5% normal serum. Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped using DAPI mounting media to label cell nuclei and stored at 4°C. BrdU-NeuN-S100. Sections were denatured in 2N HCl for 50 minutes at room temperature and then neutralized twice in 0.1M borate buffer, pH 8.5, rinsed again in PBST, blocked in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBST for 1 hour, and incubated overnight at 4°c in a mixture of rat anti-BrdU antibody in PBST + 5% normal serum. The following day, sections were incubated for 1.5h at room temperature in a mixture of secondary reagents (Jackson ImmunoResearch): goat anti-rat Cy3 (1:2000), goat anti-mouse 647 (1:500), and goat anti-rabbit DyLight 488 (1:1000) in PBST + 5% normal serum. Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped using DAPI mounting media to label cell nuclei and stored at 4°C. BrdU-NeuN-S100. Sections were denatured in 2N HCl for 50 minutes at room temperature and then neutralized twice in 0.1M borate buffer, pH 8.5, rinsed again in PBST, blocked in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBST for 1 hour, and incubated overnight at 4°c in a mixture of rat anti-BrdU antibody in PBST + 5% normal serum. The following day, sections were incubated for 1.5h at room temperature in a mixture of secondary reagents (Jackson ImmunoResearch): goat anti-rat Cy3 (1:2000), goat anti-mouse 647 (1:500), and goat anti-rabbit DyLight 488 (1:1000) in PBST + 5% normal serum. Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped using DAPI mounting media to label cell nuclei and stored at 4°C.

BrdU-NeuN-S100

Sections were denatured in 2N HCl for 50 minutes at room temperature and then neutralized twice in 0.1M borate buffer, pH 8.5, rinsed again in PBST, blocked in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBST for 1 hour, and incubated overnight at 4°c in a mixture of rat anti-BrdU antibody in PBST + 5% normal serum. The following day, sections were incubated for 1.5h at room temperature in a mixture of secondary reagents (Jackson ImmunoResearch): goat anti-rat Cy3 (1:2000), goat anti-mouse 647 (1:500), and goat anti-rabbit DyLight 488 (1:1000) in PBST + 5% normal serum. Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped using DAPI mounting media to label cell nuclei and stored at 4°C.

GFP

Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody followed by incubation in goat anti-chicken DyLight 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:1000) at room temperature in PBST + 5% normal serum for 90 minutes. Slices were rinsed in PBST, mounted with DAPI, and coverslipped.

Quantification and Image analysis

All cell quantifications were conducted from a 1-in-12 series (1- in 6 series if not enough cells found for phenotypic quantification) of labeled sections spanning the rostrocaudal extent of the dentate gyrus. Cell quantifications of labeled-cells were conducted by an experimenter blind to the experimental conditions. Quantification is displayed as a density rather than in absolute numbers as Grf2-KO mice have a significantly lower dentate gyrus volume at 2 and 3 months compared to age-matched wild-type mice (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of measurements in wild-type and GRF2-KO mice.

Detailed quantification results of Ki-67, DCX, BrdU, and BrdU phenotyped cells in the dentate gyrus of wildtype and Grf2-KO mice. Reference volumes of the dentate gyrus are significantly reduced in Grf2-KO mice compared to wild-type after 1-month of age (Two-Way ANOVA, Genotype effect,F1,39 = 24.97, p < 0.0001; 2-month, t = 4.85, p < 0.001; 3-month, t = 2.65, p < 0.05). Table shows means ± s.e.m.

| Genotype | Age at time of BrdU injection | Density of Ki67+ cells | Density of BrdU+ cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “age +1 week” | “age +4weeks” | “age +1week” | “age +4weeks” | |||

|

|

||||||

| 1mo-old | 326 ± 48.0 N=6 | 235 ± 31.9 N=6 | 845 ± 90.2 N=6 | 344 ± 16.2 N=7 | ||

|

|

||||||

| WT | 2mo-old | 183 ± 15.2 N=4 | 433 ± 28.4 N=5 | 142 ± 13.6 N=5 | ||

|

|

||||||

| 1mo-old | 286 ± 79.5 N=4 | 270 ± 9.2 N=6 | 960 ± 59.7 N=5 | 128 ± 9.8 N=5* | ||

|

|

||||||

| Grf2-KO | 2mo-old | 141 ± 23.1 N=7 | 382 ± 29.6 N=8 | 73 ± 3.8 N=11* | ||

|

| ||||||

| DCX signal intensity | Reference Volume (mm3) | |||||

| 1mo-old | 2mo-old | 3mo-old | 1mo-old | 2mo-old | 3mo-old | |

|

|

||||||

| 251050 ± 23089 | 188440 ± 9871.7 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| WT | 291975 ± 8789.5 N=11 | N=8 | N=7 | 0.23 ± 0.007 | 0.25 ± 0.009 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

|

|

||||||

| 160765 ± 8232 | 128525 ± 8846.8 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Grf2-KO | 274945 ± 11084.5 N=20 | N=19* | N=16* | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.01* | 0.2 ± 0.02* |

|

| ||||||

| Density of Phenotyped cells | ||||||

| BrdU+ | BrdU+/NeuN+ | BrdU+/S100+ | ||||

|

|

||||||

| WT | 4.6 ± 0.7 N=5 | 111 ± 16.8 N=5 | 4.2 ± 0.6 N=5 | |||

|

|

||||||

| Grf2-KO | 3.9 ± 1.1 N=4 | 50.2 ± 2.8 N=4* | 4.3 ± 1.4 N=4 | |||

= significantly different than wild-type

Ki67+

Ki-67+ cells were counted using a Nikon 80i microscope with ×40 objective. The surface area of the granule cell layer (GCL) was outlined and measured using ImageJ software. The reference volume of the GCL was calculated as the sum of the traced areas multiplied by the distance between sampled sections (360μm). The total number of cells was calculated as previously described (Trouche et al., 2009).

BrdU+ nuclei quantification

A Nikon A1R confocal laser-scanning microscope was used for BrdU+ nuclei quantification. The settings for PMT, laser power, gain and offset were identical between experimental groups. Each BrdU+ cell within the granular cell layer (GCL) and, adjacent subgranular zone (SGZ) defined as a 2-cell body wide zone was analyzed for colocalization with each marker by collection of an image stack at 2μm step intervals over the entire z-axis using a ×40 objective. The reference volume of the GCL was calculated and the total number of BrdU+ cells was determined.

DCX+ quantification

DCX+ cell quantification was performed in essentially the same manner. Cell bodies of DCX+ cells were quantified within the entire DG of each slice. The reference volume of the GCL was calculated as the sum of the traced areas multiplied by the distance between sampled sections (360μm).

Determination of cell phenotype

To determine the mean percentage of BrdU+ cells co-expressing either NeuN (postmitotic neurons) or S100 (as mainly an astrocytic marker), four randomly selected animals were sampled for each genotype. A minimum of 30 BrdU+ cells per mouse were randomly chosen for analysis. Colocalization was confirmed by performing z-stack acquisitions using ImageJ software. The mean number of cells for each phenotype was obtained by multiplying the average fraction for each phenotype by the individual BrdU+ cell count for each animal.

Quantification of GFP immunoreactive cell (GFP+)

GFP+ cells were counted using a Nikon 80i fluorescent microscope with ×40 objective. To measure the density of new cells, GFP+ cells were totaled and divided by the number of sections containing any GFP+ cells. Although reliable infection rates were seen between mice using the same retroviral stock, absolute numbers of GFP+ cells could vary. To reduce this variability, densities recorded at 4 weeks were normalized to the densities recorded at 7 days as previously described (Tashiro et al., 2006a).

Slice electrophysiology and pERK activation

3-month old wild-type and Grf2-KO mice, aged 3 months, were used to generate transverse hippocampal slices (400μm) for evoked field potential recordings from newborn neurons as previously described (Kheirbek et al., 2012b). Briefly, transverse hippocampal slices were incubated at 32°C in an interface chamber and perfused with oxygenated ACSF (in mM: 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 26.2 HaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 11 glucose) and allowed to equilibrate for at least 2 hours. Stimulation of the medial prefrontal path (MPP) was performed using a bipolar electrode and evoked field potentials were recorded from the molecular layer of the DG using a glass capillary microelectrode filled with ACSF. After 10 min of stable baseline recordings (once every 20s), LTP was induced with four trains of 1s each, 100Hz within the train, repeated every 15s. Responses were recorded every 20s for 50 minutes after LTP induction.

p-Erk activation

Detection of a phosphorlyated form of Erk (T202/Y204) was performed on hippocampal slices after stimulation of the DG using the ACSF conditions described above with an increased current intensity of 140μA (Dudek and Fields, 2001; Jin et al., 2013). 5 min after stimulation, slices were immersed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C followed by immersion in 30% sucrose for 48 hours. Thin sections (18μm) were prepared from a cryostat and adhered directly to a slide in preparation for immunostaining. Upon extensive washing with PBST, slices were blocked in PBST + 5% NGS followed by incubation with pErk antibody overnight at room temperature. The next day, slices were incubated in goat anti-mouse 488 secondary antibody for 90 minutes, washed, and counterstained with DAPI before being coverslipped.

Inhibitors

Inhibitors to NMDA receptor subunits NR2A (PEAQX, 0.5μM or 4μM), NR2B (Ifenprodil, 3μM), and total NMDA (APV, 100μM) were used to assess the ability to prevent ACSF-LTP and/or inhibit the activation of Erk. The MEK inhibitor U0126 (30 μM) was used to inhibit the activation of LTP. Inhibitors for CP-AMPAR (IEM-1460, 30 μM) and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (Scopolamine, 30μM) were used for the assessment of Erk activation. Inhibitors were added to the ACSF solution 60 min prior to stimulation.

Quantification of pERK activation

Stimulation of the MPP to elicit activation of ERK in the DG was confined to a small area of the DG granule cell layer (GCL). For each condition, the region of interest (ROI) was constructed using the entire GCL as the height and the pERK+ stained cells as the width using ImageJ. The total number of pERK+ cells was counted first using the Cell Counter function followed by overlaying the ROI onto the DAPI image where the total cell count was measured using the Analyze Particles function. Cell counts are displayed as the percentage of pERK+ cells within the population.

Contextual Discrimination

Behavioral performance in the contextual discrimination assay was performed as described previously (Giese et al., 2001; Jin and Feig 2013) on 2-3 month old (WT n=8 and Grf2-KO n=8) mice. The mice were trained to discriminate between two contexts, one being the chamber itself in which they were shocked and a similar context in which the walls of the chamber were changed to alternating white and black bars but retained the metal grid floor, in which they were not. The first day, mice were pre-exposed to both contexts for 10 minutes. On days 2 and 3, the mice were shocked in one context (paired); after 148 s, a 2-s shock (0.75mA) was delivered, and the mice remained for another 30s in the context. After 3 hrs., the mice were exposed to the other context (unpaired) and received no shock over the 180s time period. On day 4, the mice were tested for their freezing behavior over the duration of 3 minutes in each of the two contexts.

Quantification of freezing

Freezing behavior was measured using a digital camera connected to a computer with Actimetrics FreezeFrame software. The bout length was 1 s and the threshold for freezing behavior was determined by an experimenter blind to experimental conditions and animal group.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Prism5 software was used for data analysis. Differences between groups were assessed by ANOVAs or unpaired t-tests. Posthoc multiple comparisons using Bonferroni's correction were performed unless otherwise indicated. For all comparisons, values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

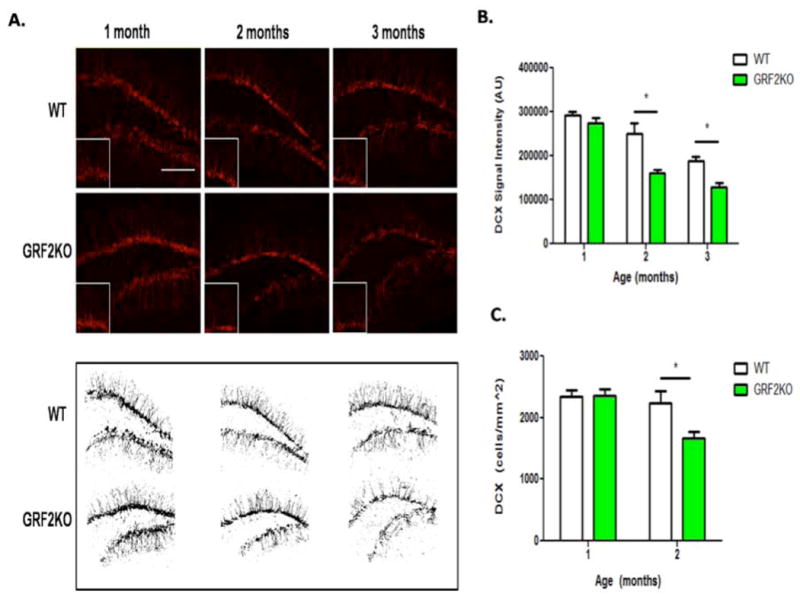

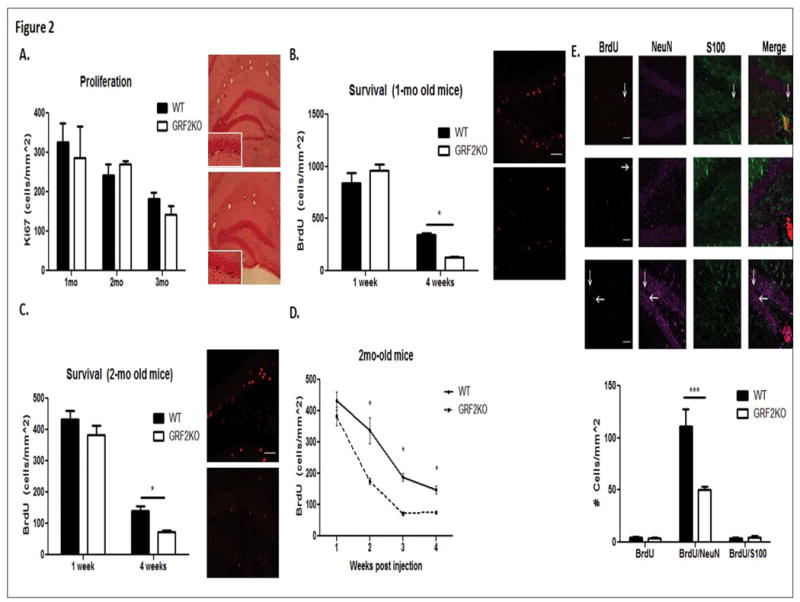

GRF2 promotes the late survival of newborn neurons in the dentate gyrus

To evaluate whether GRF2 plays a role in adult hippocampal neurogenesis, we examined levels of doublecortin (DCX) immunostaining, a known marker of new neurons at an intermediate stage of development, in 1, 2 and 3 month-old wild-type and Grf2-KO mice. We observed a significant reduction in DCX staining intensity and cell number in Grf2-KO mice compared to control mice at 2 months of age (Fig. 1). In order to assess whether this reduction in net neurogenesis was due to a difference in proliferative capacity and/or in survival, we quantified newborn cell proliferation by labeling cells with Ki-67 and by birth-dating cells with 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU). As shown in figure 2A, the density of Ki-67 labeled cells was similar between Grf2-KO and wild-type mice at any age tested. A “pulse-chase” paradigm, consisting of a 1 and 4-week chase after injection of BrdU was performed to examine the early and late critical windows for survival in newborn neurons, respectively (reviewed in Ming and Song, 2011). Figures 2B and 2C show that in both 1-month and 2-month old injected animals, 1-week survival of neurons was similar in both wild-type and Grf2-KO mice. In contrast, in both 1-month and 2-month-old injected mice, survival of newborn neurons 4-weeks after birth in Grf2-KO mice was substantially reduced compared to those in control mice. We confirmed the survival defect is neuron-specific by triple labeling 2-month old wild-type and Grf2-KO tissue for BrdU, S100 (astrocytes) and NeuN (neurons) and quantified the results (Fig. 2E).

Figure 1. Grf2-KO mice have reduced neurogenesis after 1 month of age.

A. Top: Doublecortin (DCX) immunostaining in the dentate gyrus from 1, 2 and 3 month old wild-type and Grf2-KO mice. Bottom: Representative images of anatomically matched slices highlighting overall DCX signal intensity in WT and Grf2-KO mice at 1, 2, and 3 months of age. Scale bar = 50μm. B. The DCX signal intensity in the DG decreases at 2-months of age in Grf2-KO mice compared to WT mice (n =7-20 slices, Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test, Genotype × Age, F2,75 = 4.99, p < 0.01; 2-month; t =5.12, p < 0.001; 3 month, t = 3.16, p < 0.01). C. DCX+ cells are reduced in Grf2-KO mice at 2 months of age (Two-Way ANOVA, Genotype × Age, F1,12 = 4.96, p < 0.05; 2mo-WT vs. 2mo-Grf2-KO, t = 3.07, p < 0.05). Graphs show mean ± s.e.m.

Figure 2. Cell loss in Grf2-KO mice is restricted to late-stage survival of newborn neurons 1 week after birth in young and adult mice.

A. Quantification of Ki-67 labeled cells at 5 (1-month + 1 week), 9 (2-months + 1 week), or 12 weeks of age reveals no difference in proliferation rates between wild-type and Grf2-KO mice (N = 4-7 mice per genotype/age; Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test, 5 weeks, t = 0.68, p > 0.05; 9 weeks, t = 0.55, p > 0.05; 12 weeks, t = 0.73, p > 0.05). B. No difference in BrdU-labeled cells is seen between 1-month old wild-type and Grf2-KO mice injected with BrdU and sacrificed 1 week later but are significantly reduced in 1-month old Grf2-KO animals injected with BrdU and sacrificed 4 weeks later compared to wild-type (N = 5-7 mice per genotype/time point, Genotype × Time, F1,19 = 8.98, p < 0.01; 1-week t = 1.45, p > 0.05; 4-weeks, t = 2.39, p < 0.05). C. Similarly, a significant decrease in BrdU-labeled cells is seen between 2-month old Grf2-KO mice injected with BrdU and sacrificed 4 weeks after injection compared to wild-type, but not 1 week after injection (N = 5-11 mice/genotype, Genotype effect, F1, 31 = 10.88, p < 0.01; Time effect, F1, 31 = 257.85, p < 0.0001; 1-week, t = 1.71, p > 0.05; 4-weeks, t = 3.21, p < 0.01). D. GRF2 affects survival of newborn cells between 1 and 2 weeks after birth (1-week, t = 1.73, p > 0.05; 2-weeks, t = 4.99, p < 0.001; 3-weeks, t = 3.35, p < 0.01; 4-weeks, t = 3.24, p < 0.01). E. Loss of cells in Grf2-KO mice is neuron-specific. Top: Triple labeling for NeuN (neurons), S100 (astrocytes) and BrdU was used to determine the phenotype of newborn cells. Scale bars = 50μm.Bottom: Quantification of the phenotype of BrdU-labeled cells revealed a significant reduction in BrdU/NeuN labeled cells, but not BrdU/S100 labeled or BrdU single labeled cells (2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc, Genotype × Cell Type, F2,21 = 9.87, p < 0.001; BrdU alone, t = 0.07, p > 0.05; BrdU/NeuN, t = 5.47, p < 0.001; BrdU/S100, t = 0.01, p> 0.05. Graphs show mean ± s.e.m.

To more precisely determine the timing of the survival defect in GRF2 knockout mice, we compared BrdU-labeled cells in wild-type and Grf2-KO mice 2 and 3 weeks after injection. We found the defect begins between 1 and 2 weeks after their birth (Fig. 2D). A detailed description of the results are depicted in Table 1.

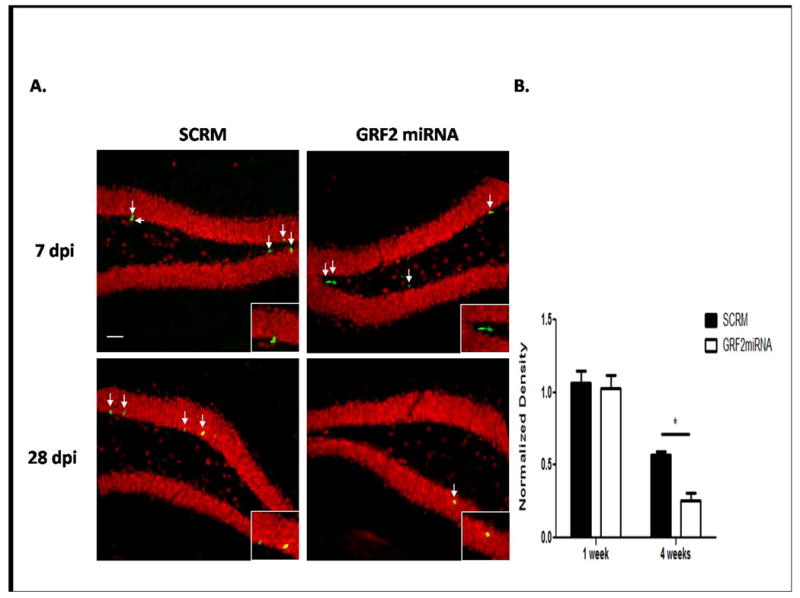

RasGRF2 contributes to newborn neuron survival in a cell-autonomous manner

Since the mice used in the previous experiments lacked GRF2 in all neurons, we tested whether the survival defect observed was due, at least in part, to the loss of GRF2 in new neurons by suppressing GRF2 expression only in new-born neurons. To this end, we produced GFP encoding retroviruses, which infect only dividing cells, along with the expression of an shRNA shown previously to specifically target GRF2 (GRF2 miRNA, (Jin et al., 2013) or a scrambled shRNA (SCRM) and injected them into the left or right dentate gyrus of 2-month old wild-type mice, respectively. GFP cells in the dentate gyrus were then counted 7 days or 28 days later. No difference was observed between the number of cells expressing SCRM-miRNA or GRF2-miRNA viruses 7 days after injections. However, GRF2-miRNA-expressing cells were significantly reduced compared to SCRM-miRNA expressing cells 28 days after injection. Since these results mimicked those obtained with GRF2 knockout mice, GRF2 acts, at least in part, in a cell autonomous manner to regulate survival of newborn cells.

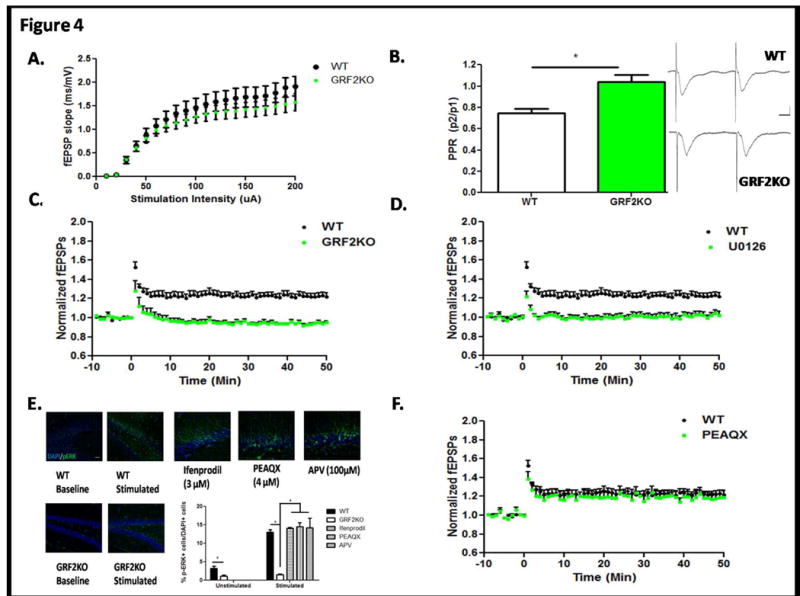

GRF2 contributes to synaptic plasticity unique to newborn neurons by activating the ERK Map Kinase pathway

Newborn neurons between 4 and 6 weeks of age make unique contributions to the circuitry of the dentate because they are more excitable than their fully mature neighboring counterparts (Ge et al., 2007). As such, LTP can be induced more easily in them even in absence of inhibitors of GABA receptors (referred to as ACSF-LTP) that are normally required for LTP induction in mature granule cells. To test whether GRF2 contributes to LTP specifically in new neurons, the dentate gyrus in hippocampal brain slices from 3 month-old wild-type and Grf2-KO mice were stimulated with ACSF-LTP. No difference in the input/output relationship was observed (Figure 4A), however, we did observe a reduced paired pulse ratio of fEPSPs in Grf2-KO slices compared to typical paired pulse depression seen in wild-type slices (Figure 4B). Figure 4C shows that ACSF-LTP was completely blocked in Gfr2-KO mice (WT, 123 ± 3.5%; Grf2-KO, 96 ± 2.3%; N = 7 slices/group).

Figure 4. Synaptic plasticity of newborn neurons requires GRF2 and is mediated by ERK Map Kinase.

A. Baseline synaptic transmission is normal in Grf2-KO mice (n = 8 slices/genotype). Input/output relationships were determined by applying sequentially increasing stimuli strengths to the MPP and recording the resulting fEPSPs B. Paired-pulse ratio reveals a reduction of paired-pulse depression of the MPP in Grf2-KO slices compared to WT mice (Student's t-test, t = 3.64, p < 0.01). EPSPs were recorded using a stimulation of 60uA at an ISI of 50ms to compare the amplitude of the second EPSP peak as a ratio to the first EPSP. Inset: Representation of the trace average for WT and Grf2-KO paired-pulse EPSPs. Calibration: Horizontal = 10ms, Vertical = 0.5mV. C. ACSF-LTP induction is blocked in Grf2-KO mice compared to wild-type (Repeated Measures ANOVA, F59,708 = 10.28, p < 0.0001). D. Erk inhibitor U0126 (30μM) completely blocks ACSF-LTP induction in wild-type mice (WT, 123 ± 3.5%; U0126, 101 ± 2.6%; (Repeated Measures ANOVA, Genotype × Time, F59,708 = 8.78, p < 0.0001). E. Activation of Erk MAP Kinase during ACSF-LTP is mediated by Ras-GRF2. Representative images of phospho-ERK immunostaining in unstimulated WT or Grf2-KO slices and representative images of phospho-ERK immunostaining after ACSF-LTP inducing stimulation in WT slices pre-incubated with ifenprodil (3μM), PEAQX (4μM), or APV (100μM). Scale bar = 50μm. Quantification of p-ERK+ cells within the area of activation of the DG reveals activated Erk is ablated in Grf2-KO slices, but not by NMDA inhibition of WT slices (Unpaired t-test, Unstimulated WT vs Grf2-KO slices, t = 3.86, p = 0.0084; Stimulated slices, One-way ANOVA F4,20 = 13, p <0.0001; Bonferroni post hoc, WT vs Grf2-KO, t = 6.20, p < 0.05; WT vs. Ifenprodil, t =0.59, p > 0.05; WT vs. PEAQX, t = 0.83, p >0.05; WT vs. APV, t = 0.72, p > 0.05) F. The NR2A inhibitor PEAQX (0.5μM) has no effect on ASCF-LTP (WT, 123 ± 3.5%; PEAQX, 120 ± 5.2%, F59,590 = 0.49, p = 0.99).

We found previously that GRF2 contributes to NMDA-R mediated LTP in the CA1 hippocampus of mice older than 3 weeks by activating Erk MAP kinase (Need Tian et al., 2004 here?). Thus, to test whether ACSF-LTP in new neurons also involves Erk MAP kinase, brain slices were pretreated with the MEK inhibitor UO126 or buffer control before stimulation. Figure 4D shows that LTP was severely inhibited to levels similar to that found in Grf2-KO mice (WT, 123 ± 3.5%; U0126, 101 ± 2.6%; N = 7 slices). To test whether ACSF-LTP leads to Erk activation in a Grf2-dependent manner, control and stimulated brain slices from wild-type and Grf2-KO mice were stained with phospho-specific antibodies to activated Erk. Figure 4E shows that ACSF-LTP induced robust Erk activation in a small fraction of dentate neurons in wild-type mice. However, in G rf2- KO mice baseline levels of activated Erk were reduced compared to control mice and no detectable increase was observed upon stimulation. Together these findings imply that GRF2 contributes to new neuron LTP via its ability to mediate Erk activation.

Previous studies have shown that ACSF-LTP involves NR2B subunit-containing NMDA-Rs (Snyder et al., 2001, Ge et al, 2007, Kheirbek et al., 2012b), suggesting that in this region of the hippocampus NR2B NMDA-Rs may signal through GRF2 to promote Erk activation that is required for LTP in new neurons. To test this hypothesis, hippocampal slices were pretreated with ifenprodil, an inhibitor of NR2B receptors, and then tested for ACSF-LTP. As shown previously, LTP was blocked (data not shown). However, Erk activation was not inhibited (Fig. 4E), indicating that although NR2B NMDA-Rs do regulate new neuron LTP, it is not through GRF2 and Erk. Next we tested for the involvement of NR2A-containing NMDAR-s by applying the NR2A inhibitor NVP-AAM077 (PEAQX). At a dose where PEAQX has at least a 5-fold preference for NR2A over NR2B (Frizelle et al., 2006);(Vasuta et al., 2007) it also did not block ACSF-LTP (Figure 4F). Even at a high dose (4μM) where it likely also blocks NR2B receptors, it did not block Erk activation (Figure 4E). Finally we tested the general NMDA-R inhibitor APV. It also did not block stimulus-induced Erk (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that ACSF-LTP in new neurons is driven by two parallel pathways, one via NR2B receptors through an unknown effector protein and another via a non-NMDA-R pathway that activates Erk through GRF2.

Previously, we showed that GRF2 can mediate Erk activation by calcium permeable AMPA receptors (CP-AMPARs, Tian et al., 2006). However, the CP-AMPAR inhibitor IEM-1460 did not block ACSF-LTP (WT, 123 ± 3.5%; IEM, 115 ± 1.7%, Two-Way ANOVA, Drug effect F1,472 = 2.18, p = 0.18). Previous studies have also implicated GRFs in mediating muscarinic acetylcholine receptor activation of Erk in tissue culture cells (Mattingly and Macara, 1996), but scopolamine, an inhibitor of this type of receptor also did not block stimulus induced activation of Erk (data not shown). Finally, we found that inhibiting all of these potential activators of GRF2 i.e., AVP, IEM and scopolamine, together also did not block stimulus-induced Erk activation (data not shown). Thus, the synaptic receptor that contributes to ACSF-LTP through the activation of Erk by GRF2 remains to be determined.

GRF2 in new neurons contributes to their enhanced survival after environmental enrichment

Neurogenesis is responsive to a number of environmental and physiological influences. Environmental enrichment has been shown to induce an increase in survival of newborn neurons and is associated with the reversal of behavioral phenotypes observed after negative influences, such as stress. The signaling molecules that mediate this effect are poorly understood. The effect on survival from enrichment has been shown to occur within a critical window 1-2 weeks after the birth of new neurons, a stage where we show GRF2 first contributes to new neuron survival (Fig. 2D). Thus, to test for a role for GRF2 in this process, Grf2-KO and wild-type mice were exposed to this enrichment paradigm (Fig. 5A). A significant suppression of enhanced survival was observed in Grf2-KO mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 5B, top, 5C). In particular, an approximate 2-fold (1.96) increase in survival was observed in wild-type mice compared to their home cage counterparts, significantly greater than the 1.37 fold increase that was observed in enriched Grf2-KO mice. (Fig. 5B, bottom).

To test whether GRF2 in new neurons themselves is required for enhancement of survival after environmental enrichment, the previous experiment was repeated with wild-type mice infected with either GFP plus SCRM or GFP plus shRNA against GRF2-expressing retrovirus in the dentate gyrus.Fig. 5D shows that even when GRF2 expression is inhibited only in new neurons, the effects of EE are suppressed, indicating that GRF2 in new neurons but not surrounding neurons is responsible for this function.

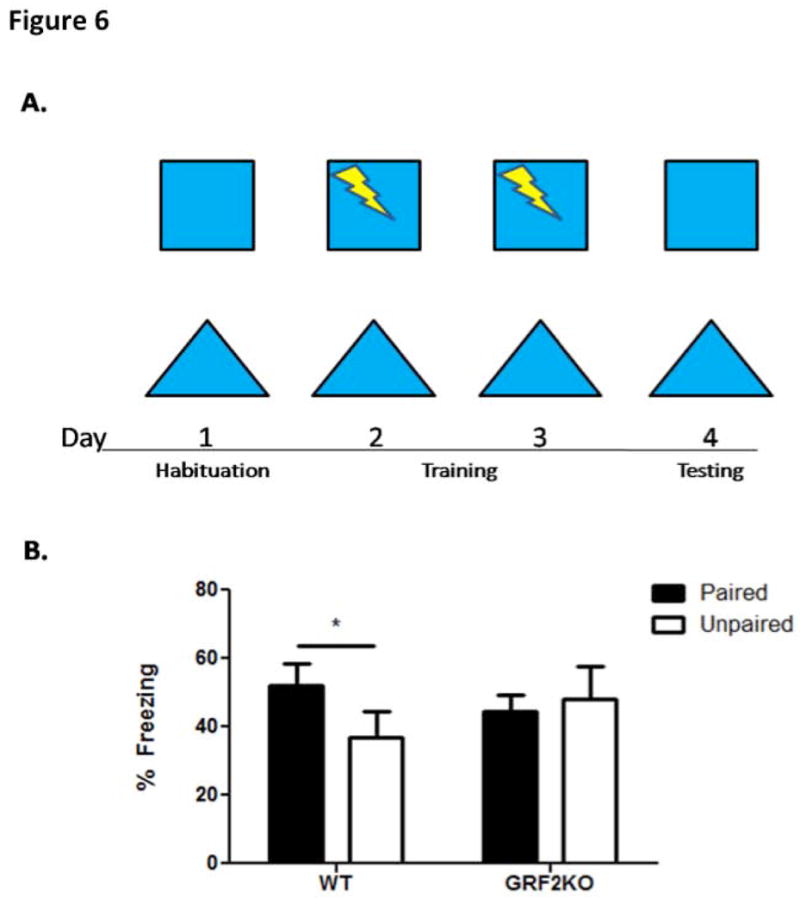

GRF2-KO mice display a defect in contextual discrimination learning

Newborn neurons derived from adult neurogenesis have been shown to contribute to pattern separation that contributes to the ability to discriminate between two closely related contexts (Clelland et al., 2009; Creer et al., 2010); Sahay et al., 2011b; (Kheirbek et al., 2012b; Sahay et al., 2011b, 2012b) a predominate function of the dentate gyrus in new memory formation (McHugh et al., 2007; Aimone et al., 2011). To examine whether the defect in neurogenesis detected in GRF2 mice could be significant enough to induce a learning/memory deficit, Grf2-KO mice were tested in a contextual discrimination paradigm (Giese et al., 2001,Jin et al, 2013,Fig. 6A) in which mice were trained in a context and given a shock (paired) or placed in a similar context but not given a shock (unpaired) and then tested for their ability to distinguish between them. As expected, wild-type mice froze significantly less in the unpaired context. However, Grf2-KO mice froze equally in both contexts (Fig. 6B). Thus, Grf2-KO mice display a learning deficit consistent with a significant defect in adult neurogenesis.

Figure 6. Mice lacking GRF2 display impaired contextual discrimination learning.

A. Experimental design for contextual discrimination learning. Wild-type and Grf2-KO animals were habituated to both contexts on day 1. On days 2 and 3, animals received a shock in one context (paired) while receiving no shock in the other, similar context (unpaired). Animals were tested for freezing behavior on day 4 to assess their discrimination ability. B. Wild-type mice discriminate between the shock-paired context and the unpaired context (WT, N=8, t = 3.47, p < 0.05) whereas Grf2-KO mice do not ( Grf2-KO, N=8, t = 0.33, p = 0.75). Graph shows mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

This paper defines a key calcium sensor, GRF2, as an important mediator of multiple key aspects of adult neurogenesis. First, we show that GRF2 is required for adult neurogenesis to contribute to plasticity of the hippocampus. GRF2 is necessary for not only the basal rate of new neuron production through its promotion of late stage cell survival, but also for environmental enhancement of this process by exposure of mice to an enriched environment. Second, it contributes to the distinct form of LTP that occurs in newborn neurons. This reflects what is considered their most important property, enhanced excitability. Hyper-excitability allows new neurons to make unique contributions to the neuronal circuits of the dentate gyrus that are required for its distinct role in learning and memory (Ge et al., 2006; Ge et al., 2008; Massa et al., 2011). Moreover, while previous studies have implicated NMDA-Rs in promoting this form of LTP, we show here that GRF2 through its effector, Erk Map kinase, is part of a different signaling pathway that is also crucial. Consistent with these ideas is our finding that GRF2 mice are deficient in contextual discrimination, a behavior known to require this property of new neurons (Kheirbek et al., 2012b; Sahay et al., 2011b).

The production of new neurons in the hippocampus involves multiple phases, each of which is regulated. The first phase is proliferation of stem cells and early progenitors. This is followed by differentiation including sprouting of dendrites, and the beginning of integration into the network with fully developed principal neurons of the subgranular zone of the dentate. Finally, full maturation occurs when new neurons are indistinguishable from their surrounding principal neurons. More neurons are produced than those that ultimately survive, and it is new neurons that compete with each other for synaptic activity, which is required for survival (Tashiro et al., 2006a; Trouche et al., 2009). There are two critical windows during adult neurogenesis when survival appears to be regulated. The first is days 1 to 4 of their life, during the transition from amplifying neuroprogenitors to neuroblasts (Sierra et al., 2010). The second is between 1-3 weeks, when cells first begin to integrate into the circuit and compete for activity-dependent survival.

Grf2-KO mice show no defects in the proliferative phase of the process as assessed by both Ki-67 staining of proliferating cells and BrdU dating of new neurons. Rather, the loss of new neurons is first observed between 7-14 days after birth during the second window at the immature neuron stage, when cells first begin to integrate into the circuit and compete for activity-dependent survival. During this time, new neurons exhibit enhanced excitability compared to older granule cells (Wang et al., 2000); (Snyder et al., 2001); (Esposito et al., 2005) and appear particularly sensitive to modifications by experience (Gould et al., 1999; Leuner et al., 2004, 2006; Epp et al., 2007; Kee et al., 2007; Tashiro et al., 2007; Trouche et al., 2009; Tronel et al., 2010, Epp et al 2011).

GRF2 is expressed in neurons throughout the CNS. Therefore, defects in neurogenesis detected in Grf2-KO could have been due to the loss of the protein in the surrounding principal cells of the dentate gyrus through its regulation of the production of extrinsic factors that are known to promote neuronal survival such as BDNF and FGF-2. However, we could mimic the phenotype of GRF2 knockout mice by suppressing GRF2 expression only in new neurons via infection of these neurons with retroviruses expressing shRNA shown previously to be specific for GRF2. Thus, GRF2 functions in new neurons to promote cell survival. Interestingly, we showed recently that the related calcium regulated exchange factor, GRF1 is also required for new neuron survival (Darcy et al., 2013). However it acts later in development, between 2-3 weeks after new neuron birth suggesting GRF1 and GRF2 participate in different differentiation stages of new neuron function. Moreover, GRF2 begins to contribute to new neuron survival earlier in postnatal mouse development than GRF1, as Grf2 but not Grf1-KO mice influence new neuron survival in mice as young as 1-month of age.

In addition to participating in the basal rate of new neuron production, GRF2 also contributes to the ability of an enriched environment to increase the number of new neurons through increased survival. Similar to its effects on the basal levels of new neuron survival described above, GRF2 contribution to the enhancement of survival is due, at least in part, to GRF2 in new neurons, because the phenotype observed when GRF2 expression was suppressed only in new neurons was the same as that in the Grf2-KOmice. These finding are consistent with the observations that the critical window in which this environmental stimulus functions, 1-2 weeks after birth of new neurons (Bruel-Jungerman et al., 2005) is within the same time window that GRF2 was shown to influence the basal rate of neuron survival. This reasoning may also explain why we found previously that GRF1 does not contribute to the effects of enriched environment, since its effect on survival occur after this critical period for enrichment-enhanced survival (data not shown). An enriched environment may increase some types of memory formation through an enhancement of adult neurogenesis (Bruel-Jungerman et al., 2005; Sahay et al., 2011a). This implicates GRF2 function in this important form of environmentally induced brain plasticity that may influence the magnitude of specific forms of learning and memory and suggests it may be involved in others as well.

This study also revealed that GRF2 is critical for new neurons to display their distinct form of LTP (ACSF-LTP), since it is completely blocked in Grf2-KO mice.

At 4-6 weeks after birth, when new neurons are integrating into the circuitry of the dentate gyrus, they display enhanced excitability compared to surrounding fully mature neurons that are at least 8 weeks of age (Ge et al., 2007). This distinct property allows LTP in these cells to be induced even when inhibitory GABA signaling is not blocked, a necessary step for LTP to be induced in highly inhibited, fully mature neurons. This novel property is thought to be important for a key function of the dentate gyrus, pattern separation and other forms of contextual memory (Kheirbek et al., 2012b)(Saxe et al., 2006). The loss of newborn neurons seen in Grf2-KO mice could explain why there is a lack of ACSF-LTP, however, not all mechanisms that lead to decreased new neuron survival influence this special form of LTP. For example, Grf1-KO mice display quantitatively similar loss of new neuron survival as Grf2-KO mice but display normal ACSF-LTP (data not shown and Darcy et al., 2013). We did observe a lack of paired pulse depression (PPD) in Grf2-KO slices compared to wild-type, thus no synaptic weakening occurs after initial stimulation in Grf2-KO mice. This feature could possibly be due to differences in release probability as synapses recover from depression (Schneggenburger et al., 2002) or from altered mGluR activity (Brown and Reymann, 1995). We cannot exclude the possibility that this property leads to blockade of ACSF-LTP for newborn neurons in Grf2-KO mice, but one might predict that enhanced not reduced PPD would interfere with LTP. Finally, LTP in the entire dentate gyrus, as assayed in the presence of the GABA inhibitor bicuculline, is also impaired in Grf2-KO mice (data not shown). Thus, the overall circuitry associated with LTP in the dentate gyrus as well as newborn neurons is defective in mice lacking GRF2.

Signaling pathways that regulate ACSF-LTP in newborn neurons are poorly defined. At the level of receptors that could function through GRF proteins, NMDA-Rs containing NR2B subunits have been implicated (Ge et al., 2007); (Kheirbek et al., 2012b), however no downstream targets have been identified other than the transcription factor Kruppel-like factor 9 (Scobie et al., 2009). Here we show GRF2 and its downstream target Erk Map kinase as additional contributors, since inhibition of either blocks ACSF-LTP and ACSF-LTP activates Erk Map kinase in a GRF2-dependent manner. We showed previously that GRF2 couples NMDA-Rs containing NR2A, but not NR2B, receptors to LTP through Erk Map kinase in the CA1 hippocampus. However, using an inhibitor of NR2A NMDA-Rs we found that this was not the case in these neurons. NR2B NMDAR-s were also not involved because even though we found that an NR2B inhibitor blocked ACSF-LTP, as previously reported, it did not block Erk activation associated with it. Neither did the broad NMDA receptor inhibitor APV, or inhibitors of other known upstream regulators of GRF proteins such as CP-AMPA receptors or muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Thus, these experiments define a parallel pathway distinct from NMDARs that contributes to a key function of new neurons through GRF2 and Erk, but the upstream activator of this pathway remains to be identified.

In conclusion, this study implicates GRF2 in mediating multiple properties of adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, a novel form of brain plasticity that is critical for hippocampus to perform pattern separation that is needed for animals to distinguish between closely related contexts.

Figure 3. The survival defect in Grf2-KO mice is cell-autonomous.

A. Representative images for GFP+ cells after injection of a retrovirus expressing either a scrambled miRNA (SCRM, left) or a miRNA targeting GRF2 (GRF2miRNA, right) into the left and right hemisphere of the DG, respectively of a wild-type mouse at 7 days (top) or 28 days (bottom) post injection. Dentate granule neuronal cells identified by NeuN (red) reveal GFP+ cells colocalize with NeuN at 28dpi but not 7dpi, as expected. Insets: Magnified images of GFP+ cells in the SGZ. Scale bar = 50μm. B. Quantification of the results in (A) reveals an effect that mimics the result seen in GRF2 knockout mice (Virus × Time, F1,12 = 4.75, p < 0.05; SCRM vs. GRF2-miRNA 28d, t = 3.49, p < 0.01). Graphs show mean ± s.e.m.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 MH083324 (to L. A. F.) and Grant P30 NS047243 through the Tufts Center for Neuroscience Research. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Aimone JB, Gage FH. Modeling new neuron function: a history of using computational neuroscience to study adult neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33(6):1160–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Post-natal origin of microneurones in the rat brain. Nature. 1965;207(5000):953–6. doi: 10.1038/207953a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Postnatal neurogenesis in the guinea-pig. Nature. 1967;214(5093):1098–101. doi: 10.1038/2141098a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA. For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron. 2004;41(5):683–6. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Reymann KG. Metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists reduce paired-pulse depression in the dentate gyrus of the rat in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1995;196(1-2):17–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11825-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel-Jungerman E, Laroche S, Rampon C. New neurons in the dentate gyrus are involved in the expression of enhanced long-term memory following environmental enrichment. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21(2):513–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clelland CD, Choi M, Romberg C, Clemenson GD, Jr, Fragniere A, Tyers P, Jessberger S, Saksida LM, Barker RA, Gage FH, et al. A functional role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in spatial pattern separation. Science. 2009;325(5937):210–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1173215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creer DJ, Romberg C, Saksida LM, van Praag H, Bussey TJ. Running enhances spatial pattern separation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(5):2367–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911725107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito MS, Piatti VC, Laplagne DA, Morgenstern NA, Ferrari CC, Pitossi FJ, Schinder AF. Neuronal differentiation in the adult hippocampus recapitulates embryonic development. J Neurosci. 2005;25(44):10074–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3114-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig LA. Regulation of Neuronal Function by Ras-GRF Exchange Factors. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(3):306–19. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frizelle PA, Chen PE, Wyllie DJ. Equilibrium constants for (R)-[(S)-1-(4-bromo-phenyl)-ethylamino]-(2,3-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoxalin-5-yl)-methyl]-phosphonic acid (NVP-AAM077) acting at recombinant NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors: Implications for studies of synaptic transmission. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(3):1022–32. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.024042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Goh EL, Sailor KA, Kitabatake Y, Ming GL, Song H. GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature. 2006;439(7076):589–93. doi: 10.1038/nature04404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Sailor KA, Ming GL, Song H. Synaptic integration and plasticity of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Physiol. 2008;586(16):3759–65. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Yang CH, Hsu KS, Ming GL, Song H. A critical period for enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated neurons of the adult brain. Neuron. 2007;54(4):559–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese KP, Friedman E, Telliez JB, Fedorov NB, Wines M, Feig LA, Silva AJ. Hippocampus-dependent learning and memory is impaired in mice lacking the Ras-guanine-nucleotide releasing factor 1 (Ras-GRF1) Neuropharmacology. 2001;41(6):791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Janoschka S, Ge S. Studying the integration of adult-born neurons. J Vis Exp. 2011;(49) doi: 10.3791/2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SX, Arai J, Tian X, Kumar-Singh R, Feig LA. Acquisition of Contextual Discrimination Involves the Appearance of a Ras-GRF1/p38 Map Kinase-Mediated Signaling Pathway that Promotes LTP. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.471904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SX, Feig LA. Long-term potentiation in the CA1 hippocampus induced by NR2A subunit-containing NMDA glutamate receptors is mediated by Ras-GRF2/Erk map kinase signaling. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirbek MA, Klemenhagen KC, Sahay A, Hen R. Neurogenesis and generalization: a new approach to stratify and treat anxiety disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2012a;15(12):1613–20. doi: 10.1038/nn.3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirbek MA, Tannenholz L, Hen R. NR2B-dependent plasticity of adult-born granule cells is necessary for context discrimination. J Neurosci. 2012b;32(25):8696–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1692-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Tian X, Hartley DM, Feig LA. Distinct roles for Ras-guanine nucleotide-releasing factor 1 (Ras-GRF1) and Ras-GRF2 in the induction of long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2006;26(6):1721–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3990-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa F, Koehl M, Wiesner T, Grosjean N, Revest JM, Piazza PV, Abrous DN, Oliet SH. Conditional reduction of adult neurogenesis impairs bidirectional hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(16):6644–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016928108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly RR, Macara IG. Phosphorylation-dependent activation of the Ras-GRF/CDC25Mm exchange factor by muscarinic receptors and G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;382:268–272. doi: 10.1038/382268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(9):1110–5. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A, Scobie KN, Hill AS, O'Carroll CM, Kheirbek MA, Burghardt NS, Fenton AA, Dranovsky A, Hen R. Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to improve pattern separation. Nature. 2011a;472(7344):466–70. doi: 10.1038/nature09817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A, Wilson DA, Hen R. Pattern separation: a common function for new neurons in hippocampus and olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2011b;70(4):582–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, Weisstaub N, Lee J, Duman R, Arancio O, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301(5634):805–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe MD, Battaglia F, Wang JW, Malleret G, David DJ, Monckton JE, Garcia AD, Sofroniew MV, Kandel ER, Santarelli L, et al. Ablation of hippocampal neurogenesis impairs contextual fear conditioning and synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(46):17501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607207103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Hieber C, Jonas P, Bischofberger J. Enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated granule cells of the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2004;429(6988):184–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Sakaba T, Neher E. Vesicle pools and short-term synaptic depression: lessons from a large synapse. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(4):206–12. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A, Encinas JM, Deudero JJ, Chancey JH, Enikolopov G, Overstreet-Wadiche LS, Tsirka SE, Maletic-Savatic M. Microglia shape adult hippocampal neurogenesis through apoptosis-coupled phagocytosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(4):483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JS, Kee N, Wojtowicz JM. Effects of adult neurogenesis on synaptic plasticity in the rat dentate gyrus. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85(6):2423–31. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Makino H, Gage FH. Experience-specific functional modification of the dentate gyrus through adult neurogenesis: a critical period during an immature stage. J Neurosci. 2007;27(12):3252–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4941-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Sandler VM, Toni N, Zhao C, Gage FH. NMDA-receptor-mediated, cell-specific integration of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus. Nature. 2006a;442(7105):929–33. doi: 10.1038/nature05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Zhao C, Gage FH. Retrovirus-mediated single-cell gene knockout technique in adult newborn neurons in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2006b;1(6):3049–55. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Feig LA. Age-dependent participation of Ras-GRF proteins in coupling calcium permeable AMPA-type glutamate receptors to Ras/Erk signaling in cortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Gotoh T, Tsuji K, Lo EH, Huang S, Feig LA. Developmentally regulated role for Ras-GRFs in coupling NMDA glutamate receptors to Ras, Erk and CREB. Embo J. 2004;23(7):1567–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouche S, Bontempi B, Roullet P, Rampon C. Recruitment of adult-generated neurons into functional hippocampal networks contributes to updating and strengthening of spatial memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(14):5919–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811054106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1(3):191–8. doi: 10.1038/35044558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasuta C, Caunt C, James R, Samadi S, Schibuk E, Kannangara T, Titterness AK, Christie BR. Effects of exercise on NMDA receptor subunit contributions to bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the mouse dentate gyrus. Hippocampus. 2007;17(12):1201–8. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Scott BW, Wojtowicz JM. Heterogenous properties of dentate granule neurons in the adult rat. J Neurobiol. 2000;42(2):248–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]