Abstract

The ability to sense and respond to thermal stimuli at varied environmental temperatures is essential for survival in seasonal areas. In this study, we show that mice respond similarly to ramping changes in temperature from a wide range of baseline temperatures. Further investigation suggests that this ability to adapt to different ambient environments is based on rapid adjustments made to a dynamic temperature setpoint. The adjustment of this setpoint requires TRPM8 but not TRPA1 and is regulated by phospholipase C (PLC) activity. Overall, our findings suggest that temperature response thresholds in mice are dynamic, and that this ability to adapt to environmental temperature seems to mirror the in vitro findings that PLC-mediated hydrolysis of phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate modulates TRPM8 activity and thereby regulates the response thresholds to cold stimuli.

Introduction

The ability to adapt to environmental temperature conditions is crucial for survival. Species that live in areas with significant seasonal temperature shifts need to sense threatening or rewarding temperature changes across many environmental settings. For example, mice living in seasonal areas must detect cold stimuli during both summer and winter, when ambient temperatures can vary by over 100°F, and approach or evade when appropriate.

Recent work has revealed a crucial role of the Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) family of ion channels in transduction and amplification of sensory stimuli. TRPV1-4 are essential for heat responses [4,19,24,26,39], TRPA1 is crucial for full responses to some nociceptive[16,17,21,22,25,27,33,35,40,41], pruriceptive [21,35,40,41], and possibly cold stimuli[1,12,16,33,39,44], and TRPM8 is important for normal responses to cold stimuli[2,5,7,8,10,14,15,23,42]. While much effort has been expended studying responses to thermal stimuli at room temperature and in testing precipitous changes in temperature, relatively little work has explored how organisms maintain thermal sensitivity when environmental temperatures change.

Early studies recording from cold-responsive fibers in primates showed that cold stimuli initially increased the number of action potentials fired, but that this response quickly adapted as the stimulus continued [18,20,29,30,32]. More recent work has shown in vitro that phospholipase C (PLC) modulation of phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) levels affects TRPM8 activity [6,31], and that dorsal root ganglion neurons isolated from TrpM8-KO mice did not adjust their temperature thresholds in response to varied ambient temperatures [9]. The same study also showed that changes in PIP2 concentration affected in vitro cold threshold adjustments. Evidence also suggests that the PIP2-binding protein Pirt modulates TRPM8 activity, further highlighting a key role for PIP2 in regulating cold sensitivity [34] in vitro.

While temperature adaptation has been characterized in vitro, this effect has been little studied at all in vivo. In this study, we test the cold responses of mice at a variety of baseline temperatures to assess how mice adapt to these temperatures. These studies demonstrate for the first time in vivo that TRPM8 is required for adaptation to cold stimuli, likely via a PIP2-dependent mechanism.

Methods

Animals

All mouse protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis, MO) and were in accord with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Experiments were carried out with in-house bred C57BL/6 mice originally acquired from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME), TrpM8-KO mice on a mixed C57/FVB background, TrpA1-KO mice on a pure C57BL/6 background, and TrpA1-TrpM8 dKO mice bred on a mixed C57/FVB background in-house from the single knockout strains. All mice used were male and 6–9 weeks old unless specifically noted. Mice were housed on a 12/12 hour light/dark cycle with the light cycle beginning at 6am. All mice had ad libitum access to rodent chow and water. Cage bedding was changed once a week, always allowing at least 48 hours after a bedding change before behavioral testing was carried out.

Behavioral analysis

All behavioral tests and analyses were conducted by an experimenter blinded to treatment and/or genotype. Behavioral tests were performed between 12pm and 5pm.

extended Cold Plantar Assay (eCPA)

The eCPA is described in detail elsewhere (Brenner et. al in submission). Briefly, .125”, .1875”, and .25” thick pyrex borosilicate float glass was purchased from Stemmerich Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Transparent plastic enclosures (4” × 4” × 11”) separated by opaque black dividers were arranged in one line along the center of a glass plate. The glass temperature was monitored with an IT-24P T-type filament thermocouple probe from Physitemp Instruments, Inc. (Clifton, NJ) that was secured in the middle of the plate with laboratory tape. Plate temperature data were collected from the thermocouple using an EA15 Data-Logging Dual Input Thermometer from Extech Instruments (Waltham, MA). Dry ice or wet ice was placed in aluminum boxes on either side of the enclosures to uniformly cool the glass plate. The ice was contained either in packets made of heavy-gauge aluminum foil, or in custom-built aluminum boxes. The boxes are the same length as the glass plate, 4.5 inches wide and 3 inches tall with a lid. The glass temperature can be adjusted by moving the ice containers closer to or further from the plastic enclosures. After the plate reached the desired temperature, mice were acclimated in the enclosures for 3 hours before testing. White noise was used to decrease noise disturbances.

To cool the glass plate to 17°C, the aluminum boxes were positioned approximately .25” away from the animal enclosures on either side, and filled with wet ice. After approximately 60 minutes the plate cooled to 17°C and remained at that temperature as long as the boxes were refilled with wet ice roughly every 90 minutes and excess water was drained.

To cool the glass plate to 12°C, the aluminum boxes were positioned roughly 1.25” away from the animal enclosures on either side and filled with dry ice pellets. After approximately 20 minutes, the plate cooled to 12°C and remained at that temperature as long as the boxes were refilled with dry ice roughly every 90 minutes.

To warm the glass plate up to 30°C, the aluminum boxes were positioned .125” away from the animal enclosures on either side. Water circulators set to warm the water to 48°C were positioned on either side of the glass plate. Each circulator emptied hot water into one of the aluminum boxes. Water drained directly back into the circulator reservoir via the side drains to be reheated and pumped back into the boxes. After approximately 80 minutes, the plate warmed to 30°C and remained at that temperature as long as the circulators were active.

The cold probe was generated as we have previously described[3]. Briefly, powdered dry ice was compressed against a flat surface in a 3mL BD syringe (Franklin Lakes, NJ) with the top cut off until it reached a dense, uniform consistency. Awake mice were tested by extending the tip of the dry ice pellet past the end of the syringe and pressing it against the glass underneath the hindpaw with light pressure using the syringe plunger. The center of the hindpaw was targeted, avoiding the distal joints, and ensuring that the paw itself was touching the glass surface.

The latency to withdrawal of the hindpaw was measured with a stopwatch. Withdrawal was defined as any action to move the paw vertically or horizontally away from the cold glass. Trials on separate paws on the same animal were separated by 7 minutes, and at least 15 minutes separated trials on any single paw. At least 3 trials per paw per mouse were recorded unless otherwise noted.

Hargreaves radiant heat assay

Mice were acclimated on a Hargreaves apparatus from IITC Life Sciences (Woodland Hills, CA) in transparent plastic enclosures (4” × 4” × 11”) separated by opaque black dividers for 3 hours. White noise was used to decrease noise disturbances. The heated testing plate of the Hargraves apparatus was replaced with the pyrex eCPA plate, and the cooling protocol was carried out as described above. The Hargreaves apparatus starting temperature and active intensity were varied as described in the text below, and the resting intensity was set to 2%. The resting intensity was used to target the beam to the center of the hindpaw while avoiding distal joints and ensuring that the mouse paw was fully in contact with the glass surface. Once the beam was targeted, the active intensity (AI) level was applied and the built-in timer was used to measure the withdrawal latency. Low Intensity is defined as AI=12, Moderate Intensity is defined as AI=17, and High Intensity is defined as AI=23. Unless otherwise noted, Moderate Intensity (AI=17) was used for all stimuli.

Glass temperature measurements

Temperature values between the paw and glass were measured using an IT-24P filament T-type thermocouple probe from Physitemp Instruments Inc. (Clifton, NJ). A mouse was anesthetized using a cocktail of Ketamine (Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge IA), Xylazine (Lloyd Labs Lloyd Labs Shenandoah, IA), Acepromazine (Butler Schein Animal Health Dublin, OH). The filament thermocouple was secured flush to the glass surface with the tip exposed. The anesthetized animal’s paw was taped to the glass surface over the filament thermocouple tip and allowed to reach a stable equilibrium temperature. An eCPA pellet or Hargreaves light stimulus was applied to the secured paw over the thermocouple as described below.

During the stimuli described above, data were collected using an EA15 Data-Logging Dual Input Thermometer from Extech Instruments (Waltham, MA). The data were output into CSV files which were loaded into Microsoft Excel files and analyzed using Graphpad Prism from Graphpad Software (La Jolla, CA).

PLC inhibition experiments

The PLC inhibitor U73122 and its inactive control U73343 (Tocris Bioscience, UK) were diluted in DMSO to a concentration of 320µM. Aliquots of this stock solution were kept frozen at −20°C. On experimental days, baseline eCPA latencies for the right hindpaw were measured starting at 11am. Once baseline measurements were concluded, aliquots of the drugs were defrosted and diluted with saline to a working concentration of 50µM (final solutions were 80% saline, 20%DMSO). 10µL of this solution was injected into the right hindpaw for an effective dose of 0.5 nanomoles, a dose that has been used previously to inhibit PLC activity in vivo [43]. Immediately after the injections, aluminum boxes filled with dry ice were place on the glass plate in the configuration shown in Figure 1D labeled “Glass temperature 12°C”. eCPA latencies were measured on the right hindpaw between 20–30 minutes after injection, as the glass plate was being cooled.

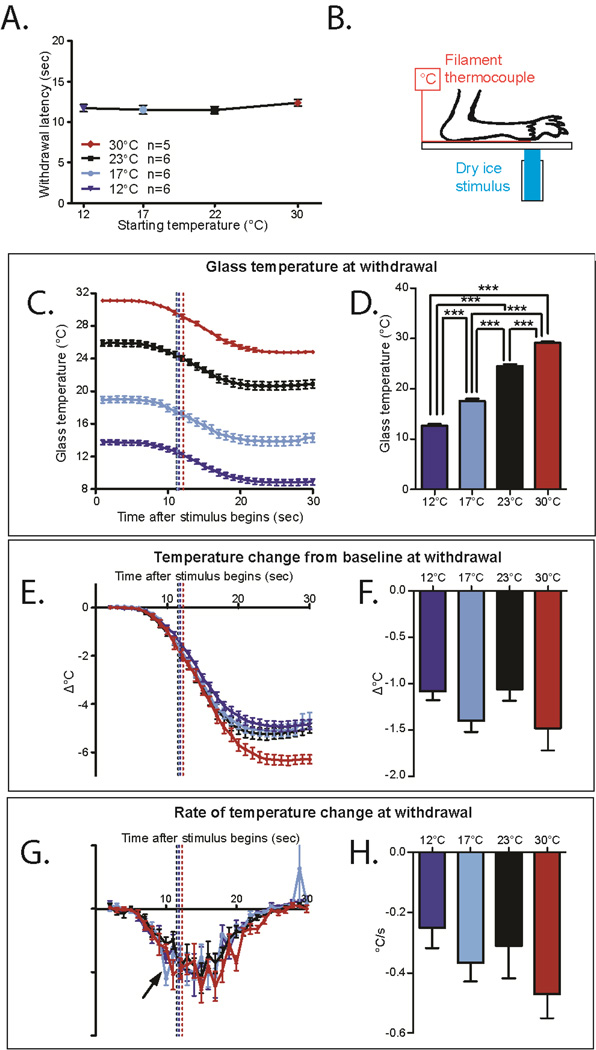

Figure 1. Mice adapt to the ambient temperature in the eCPA.

A. The withdrawal latency is unchanged at all 4 starting temperatures (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, n=6 for 30°C, n=16 for 23°C , 17°C , and 12°C not significant).

B. Schematic for measuring the cold stimulus on the eCPA. The anesthetized mouse paw is held to the glass on top of a thin filament thermocouple using laboratory tape. The dry ice stimulus is placed on the underside of the glass under the paw/thermocouple.

C. Temperatures at the glass/hindpaw interface generated by the eCPA using starting plate temperatures of 23°C, 17°C, and 12°C. The tracings start slightly higher than the overall plate temperature due to local plate warming by the mouse paw. Dotted lines represent average withdrawal latency of mice under each condition. n=5 for 30°C, n=6 for the other three conditions.

D. Temperature at the glass/hindpaw interface average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 1C at the dotted lines). The temperature at withdrawal is significantly different in each condition (1-way ANOVA main effect p=4.84×10−11 with Bonferroni post hoc test 12°C vs 17°C p=1.1×10−5, 12°Cvs 23°C p=6.0×10−10, 12°C vs 30°C p<2×10−16, 17°C vs 23°C p=2.7×10−7, 17°C vs 30°C p=1.1×10−13, 23°C vs 30°C p=6.9×107,1df n=5 for 30 °C, n=6 for the other groups)

E. Temperature change from baseline (TCFB) temperature through the course of the eCPA stimulus. The dotted line indicates the TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=5 for 30°C , n=6 for other groups.

F. TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 1E at the dotted line). The TCFB at withdrawal is not significantly different between the conditions (1-way ANOVA not significant n=5 for 30 °C , n=6 for other groups)

G. Rate of change (ROTC) of temperature through the course of the eCPA stimulus. The dotted line marks the ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=5 for 30 °C , n=6 for other groups.

H. ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 1G at the dotted line). The ROTC at withdrawal is not significantly different between the conditions (1-way ANOVA not significant n=5 for 30°C, n=6 for other groups). All data presented are mean±standard error.

L4 Spinal nerve ligation (SNL) model

The L4 spinal nerve ligation surgery was performed as described previously[13,38]. For all behavior tests, the experimenter was blinded to the surgical procedure that each mouse received. No mice were excluded from analysis. Briefly, baseline measurements of withdrawal latency in the eCPA were made on all mice at 22°C, 17°C, and 12°C. The mice were then deeply anesthetized with vaporized isofluorane. In all mice, the paraspinal muscles were bluntly dissected to expose the L5 transverse process. Mice receiving the full ligation procedure also had the L5 process removed, the L4 spinal nerve tightly ligated with silk suture (6-0, Ethicon; Cornelia, GA) and the nerve was transected distal to the ligation. Mice receiving the sham procedure had the L5 transverse process exposed but not removed, and the nerve was untouched. eCPA latencies at 22°C, 17°C, and 12°C were then measured at 2, 4, and 6 days after surgery, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All data presented are mean±standard error of the error. Analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism (La Jolla, CA) and The R Project for Statistical Computing (http://www.r-project.org/). For tests comparing a single group of animals under several conditions, a 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to measure overall effect as well as pairwise comparisons. The only exception for this was in Figure 6, where a Dunnett’s post-hoc test was substituted in order to compare all columns to the baseline condition.

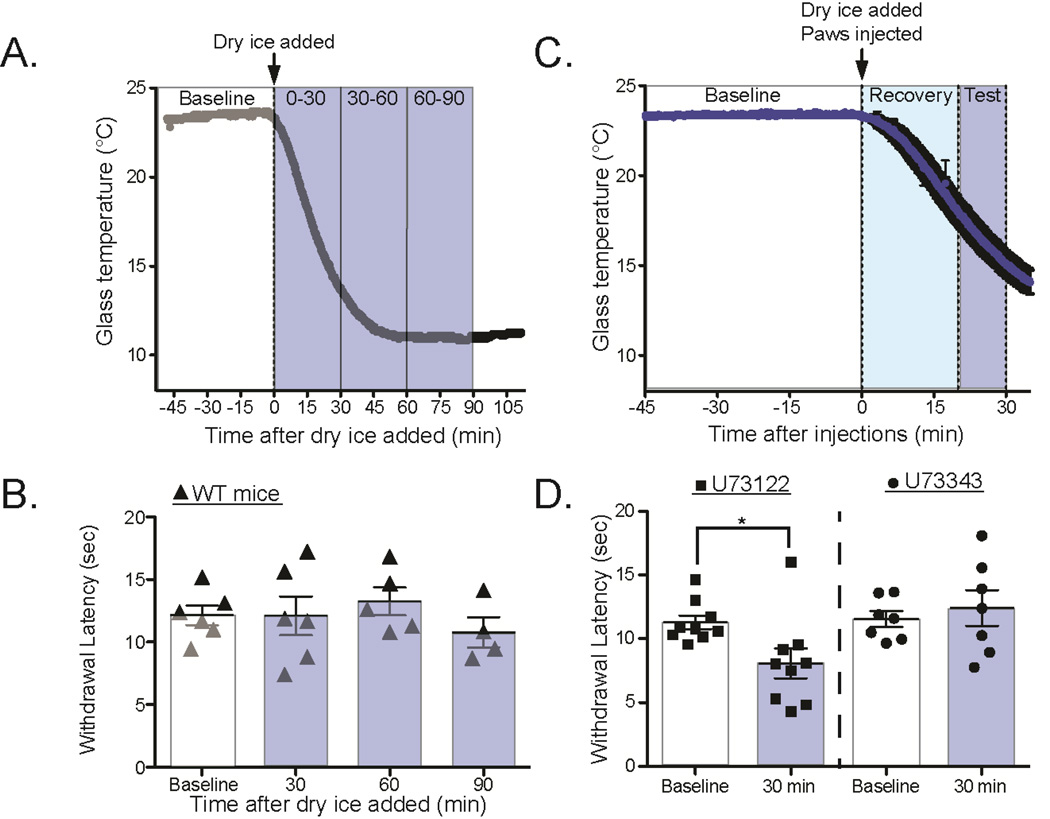

Figure 6. PLC inhibition transiently inhibits cold adaptation.

A. Mice were acclimated at room temperature, and baseline withdrawal latency was measured on the right hindpaw. At t=0 min, either .5nmol U73122 (PLC inhibitor) or .5nmol U73343 (inactive control) was injected into the right hindpaw. Immediately after injections, dry ice was added to the glass plate and eCPA latencies were measured as the glass cooled.

B. Mice injected with U73122 (square markers) have significantly decreased withdrawal latencies at 30min compared to baseline or later timepoint (baseline=11.3s±.5s, 30min =8.1s±.1.2s; 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test, main effect p=0.02, individual baseline vs. 30min p=.02; df=1 n=9). Mice injected with U73343 (circle markers) had unchanged latencies at 30 minutes compared to baseline or any other timepoint (baseline=11.6s±.6s, 30min=12.2±1.4s; 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test, no main effect n=7). All data presented are mean±standard error.

For experiments comparing more than one group of animals under several conditions, a 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to measure overall effect as well as pairwise comparisons. Statistical significance in each case was denoted as follows * or # p<0.05; ** or ## p<0.01; *** or ### p<0.001.

Results

Cold adaptation to environmental temperature changes

We found that the average withdrawal latency of wild-type mice to the cold plantar assay stimulus at room temperature is roughly 11 seconds. Surprisingly, this withdrawal latency was unchanged by major alterations of the starting temperature of the plate (Figure 1A, 30°C = 12.3s±.4, 23°C=11.5s±.5, 17°C=11.5s±.6, 12°C=11.7°C ±.4, 1-way ANOVA not significant, n=6 for 30°C,n=16 for 23°C, 17°C, and 12°C). In order to measure the temperatures generated at the glass-skin interface, we anesthetized mice and held the hind paw on top of a filament thermocouple attached to the glass surface using laboratory tape (Figure 1B). This arrangement allowed us to measure the temperature generated at the glass-skin interface during dry ice. Although ketamine anesthesia is known to depress core body temperature, positioning the anesthetized mice over the thermocouple warmed the baseline glass temperature from 22°C to 25°C (Figure 1C), suggesting that it is a reasonable approximation of a mouse at rest on the glass surface. As the starting temperature of the plate decreased, the temperature at which the mice responded also decreased (Figure 1C, dotted lines represent average withdrawal latency of mice under each condition). The average withdrawal threshold with the glass starting at 30°C was 29.2°C±.3°C while the average thresholds with the glass plate starting at 23 °C, 17°C, and 12°C were, 24.5°C±.4°C, 17.6°C±.5°C and 12.7°C±.3°C, respectively (in some cases the average withdrawal temperatures are higher than the overall glass temperature due to the body heat of the animals warming the glass underneath the paws, Figure 1D, 1-way ANOVA p=4.84×10−11 with Bonferroni post hoc test 12°C vs 17°C p=1.1×10−5, 12°Cvs 23 °C p=6.0×10−10, 12°C vs 30 °C p<2×10−16, 17°C vs 23°C p=2.7×10−7, 17°C vs 30°C p=1.1×10−13, 23°C vs 30°C p=6.9×10−7,1df n=5 for 30°C, n=6 for the other groups). This demonstrates that between ambient temperatures of 12 and 30°C, murine temperature sensation is dynamic. Although the temperature of the dry ice stimulation is constant, the withdrawal threshold is dynamic when the ambient temperature is changed.

We hypothesized that withdrawal may be initiated by one of two other parameters: the relative change of temperature from baseline (Figure 1E) or the rate of change of temperature (Figure 1G). At all three initial glass temperatures, there was a temperature change from baseline (TCFB) at withdrawal, suggesting that TCFB could be the factor that prompts withdrawal (Figure 1E–F, dotted lines represent average withdrawal latency of mice under each condition, 12°=−1.1°C±.1, 17°=−1.4°C±.1, 23°=−1.0°C±.1, 30°C=−1.4°C±.2, 1-way ANOVA not significant). Likewise the rate of temperature change (ROTC) was similar at withdrawal in all three conditions, suggesting that ROTC could also be the factor that prompts withdrawal from cold stimuli (Figure 1G–H, dotted lines represent average withdrawal latency of mice under each condition, 12°=−.3°C/s±.1, 17°=−.4°C/s±.1, 23°=−.3°C/s±.1, 30°C=−.5°C/s±.1, 1-way ANOVA not significant).

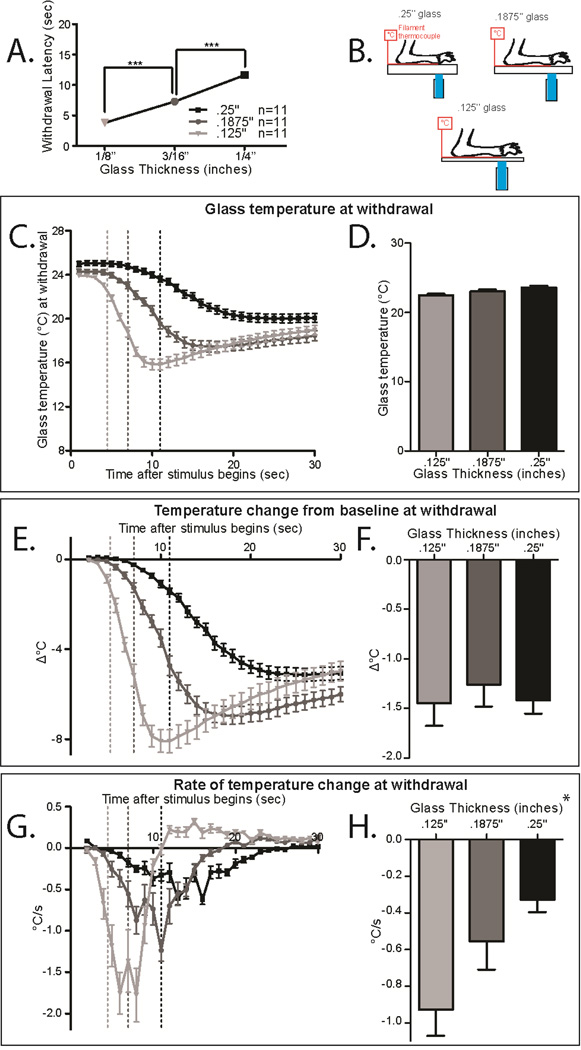

To assess whether temperature change from baseline (TCFB) or rate of temperature change (ROTC) prompts withdrawal from cold stimuli, we measured the cold ramp delivered by a dry ice pellet using 3 thicknesses of glass (Figure 2B: .125”, .1875”, and .25”). Our previous work has demonstrated that the rate of cooling has an inverse relationship with the glass thickness [3]. Under these conditions, we measured the withdrawal latency (Figure 2A), the raw temperature (Figure 2C–D), the TCFB (Figure 2E–F) and the ROTC (Figure 2G–H). As the glass thickness decreased, the withdrawal latency significantly decreased (Figure 2A 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; main effect p<2.8×10−16, .125” vs. .1875” p=5.3×10−10, .125” vs. .25” p<2.10−16, .1875” vs. .25” p=2.4×10−12; df=2, n=12 per group). The TCFB at withdrawal on the different glass thicknesses is roughly the same, suggesting that the mice could be responding to a consistent TCFB (Figure 2E–F dotted lines represent average withdrawal latency of mice under each condition, .125”=−1.5°C±.2, .1875”=−1.3°C±.3, .25”=−1.4°C±.2, 1-way ANOVA not significant n=11 per condition). In contrast, the ROTC at withdrawal on the different glass thicknesses is significantly different (Figure 2G–H dotted lines represent average withdrawal latency of mice under each condition, .125”=−.9°C/s±.2, .1875”=−.6°C±.3, .25”=−.3°C±.1, 1-way ANOVA main effect *p=0.01 n=11 per condition). These results suggest that the temperature change from baseline (TCFB) is the determining factor for withdrawal responses to cold stimuli.

Figure 2. Withdrawal from cold may depend on change from baseline or rate of cooling.

A. Withdrawal latency in the CPA using different thicknesses of glass. Mice on the thicker plates have significantly longer withdrawal latencies (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; main effect p<2.8×10−16, .125” vs. .1875” p=5.3×10−10, .125” vs. .25” p<2.10−16, .1875” vs. .25” p=2.4×10−12; df=2, n=12 per group)

B. Schematic for measuring the cold stimulus on the CPA. The anesthetized mouse paw is held to the glass on top of a thin filament thermocouple using laboratory tape. The dry ice stimulus is placed on the underside of the glass under the paw/thermocouple.

C. Temperatures generated by the CPA using .125”, .1875”, and .25” glass plates. Dotted lines mark the temperature at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=11 per group.

D. Glass temperature at the average withdrawal latency for each glass thickness (marked in 2C at the dotted lines). The temperature at withdrawal is not significantly different in each condition (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test not significant n=11 per condition)

E. Temperature change from baseline (TCFB) temperature through the course of the CPA stimulus. The dotted line indicates the TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=11 per group.

F. TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 2E at the dotted line). The TCFB at withdrawal is not significantly different between the conditions (1-way ANOVA not significant n=11 per condition)

G. Rate of change (ROTC) of temperature through the course of the CPA stimulus. The dotted lines mark the ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=11 per group.

H. ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 2G at the dotted line). The ROTC at withdrawal is significantly different between the conditions (1-way ANOVA main effect *p=0.01 n=1 per condition). All data presented are mean±standard error.

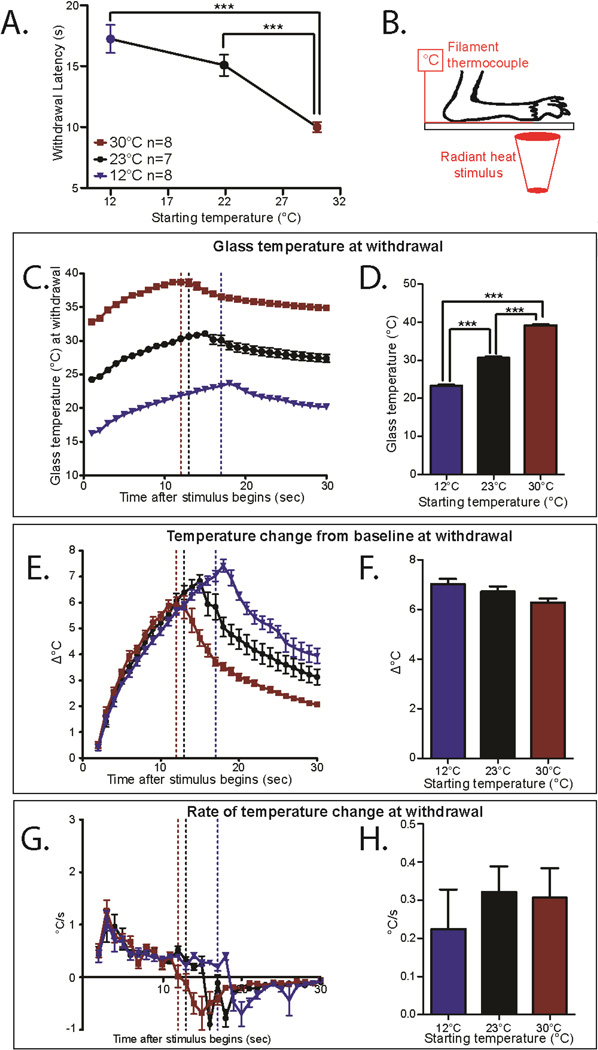

Heat adaptation to environmental temperature changes

We hypothesized that adaptation to ambient temperatures would also occur with responses to heat stimuli. In order to test this hypothesis, we used the Hargreaves radiant-heat assay. First we tested a group of mice at different starting temperatures including 12°C, 23°C, and 30°(Figure 3A). In contrast to the the eCPA, we found that changing the starting temperature did have a significant effect on the withdrawal latency (Figure 3A, 12°C=17.2s±1.2 n=6, 23°C=15.1s±.9 n=6, 30°C=10.0±.4 n=9, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test; main effect p=.0007, 12°C vs 30°C p=.0007, 23°C vs. 30°C p=.005, df=3 n=5). Compared to Figure 1A, this suggests that heat withdrawal latencies is influenced by ambient temperature.

Figure 3. Mice adapt to ambient temperatures with the Hargreaves radiant heat assay.

A. Withdrawal latency in the Hargreaves assay with different starting temperatures. Blue (12°C) and Black (23 °C) points were performed using the pyrex eCPA glass plate, and Red (30 °C) were performed using the typical Hargreaves heated plate. Mice tested at these different temperatures have different withdrawal latencies (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test; main effect p=.0007, 12°C vs 30°C p=.0007, RT-pyrex vs. 30°C p=.005; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, df=3 n=5)

B. Schematic for measuring the heat stimulus temperature on the Hargreaves apparatus. The mouse paw is taped to the glass on top of a thin filament thermocouple. The light stimulus is very briefly targeted on the paw/thermocouple with a low resting intensity before the active intensity is triggered.

C. Temperatures at the glass/hindpaw interface generated by the Hargreaves with different starting temperatures. Dotted lines mark the temperature at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C.

D. Glass temperature at the average withdrawal latency for thickness (marked in 3C at the dotted lines). The temperature at withdrawal is significantly different in each condition (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test; main effect p=8.3×10−10, 12°C vs. 23°C p=.002, 12°C vs. 30°C p=1.2×10−9, 23°C vs 30°C p=6.5×10−9; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, df=2 n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C)

E. Temperature change from baseline (TCFB) temperature through the course of the Hargreaves stimulus. The dotted lines indicate the TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=8 for 12°C and 30 °C n=7 for 23 °C.

F. TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 3E at the dotted lines). The TCFB at withdrawal is not significantly different between the conditions (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test not significant; n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C)

G. Rate of temperature change (ROTC) of temperature through the course of the Hargreaves stimulus. The dotted lines mark the ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C. There is no significant difference between the ROTC in these conditions, but the peak ROTC is long reached long before the average withdrawal (dotted lines).

H. ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 3G at the dotted line). The ROTC at withdrawal is not significantly different between the conditions (1-way ANOVA not significant; n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C). All data presented are mean±standard error.

However, when we measured the heat ramps that were being applied to the footpads, the stimulation temperature that induced withdrawal still varied significantly between the three starting temperatures (Figure 3C–D, 12°C =23.3 °±.3, 23°C=30.6°±.3, 30°C=39.2°±.3, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test; main effect p=8.3×10−10 12°C vs. 30°C p=.002, 12°C vs. 23°C p=1.2×10−9, 23°C vs 30°C p=6.5×10−9, df=2 n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C). This suggests that adaptation to environmental conditions occurs with heat sensation as well as with cold sensation.

Since there is not a constant temperature withdrawal threshold thermal stimuli, we hypothesized that either a discrete temperature change from baseline (TCFB) or rate of temperature change (ROTC) causes withdrawal responses in the Hargreaves assay. At all three starting temperatures, the TCFB was the same at the withdrawal point, suggesting that change in temperature from baseline could be the determining response factor (Figure 3E–F, 12°C=7.0°±.2, 23°C=6.7°±.2, 30°C=6.3°±.2, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test not significant, n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C). At all three starting temperatures, there was a similar rate of temperature change (ROTC) at withdrawal (Figure 3G–H, 12°C=.2°/s±.1, 23°C=.3°/s±.1, 30°C=.3°/s±.1, 1-way ANOVA not significant n=8 for 12°C and 30°C n=7 for 23°C). However, the peak ROTC occurs after roughly 2 seconds, while average withdrawal latency ranged between 10–17 seconds. Since withdrawal does not occur at the peak ROTC of the stimulus, it is very unlikely that ROTC is the definitive factor that induces withdrawal from heat stimuli.

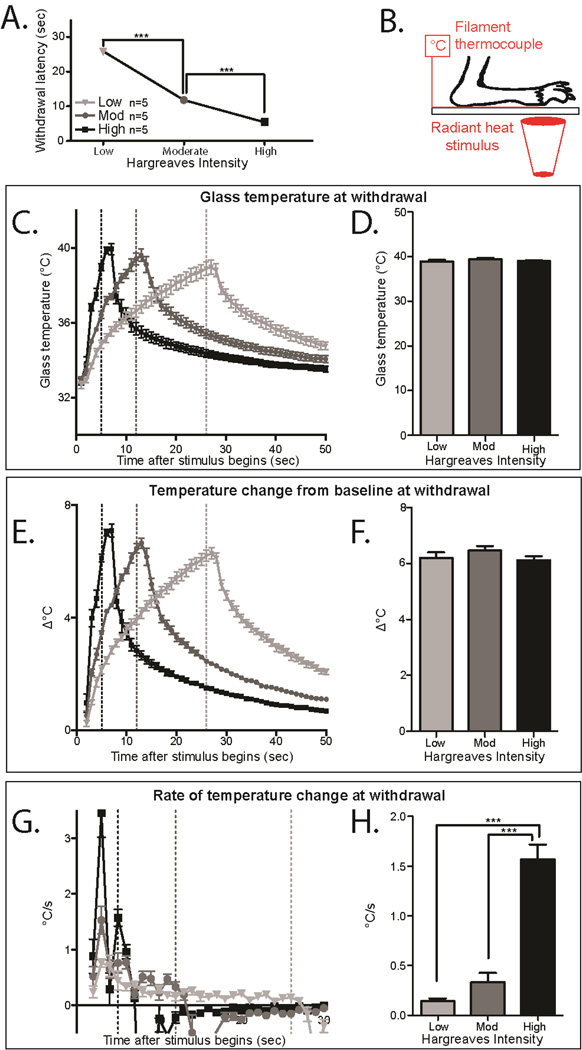

To confirm this finding, we also measured the temperatures generated by a Hargreaves stimulus utilizing 3 different active intensities (Low, Moderate, and High), which allows us to investigate the effects of changing the rate of heating. Under these conditions, we measured the withdrawal latency (Figure 4A), the temperature of withdrawal (Figure 4C–D), the TCFB (Figure 4E–F) and the ROTC (Figure 4G–H). At all three active intensities, the maximal TCFB occurred at the respective withdrawal points, suggesting that change in temperature from baseline could be the determining response factor (Figure 4E–F, Low Intensity=6.2°±.2, Moderate Intensity=6.5°±.2, High Intensity=6.1 °±.1, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test not significant n=5 per condition). The ROTC generated by the different active intensities was very different, and as before, the peak ROTC occurs within the first 2–3 seconds in all conditions, which does not correspond to the average withdrawal latencies of the mice under those conditions (Figure 4G–H, Low Intensity=.1°/s±.03, Moderate Intensity=.3°/s±.1, High Intensity=1.6°/s±.2, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; main effect p=7.7×10−7, Low vs. High p=1.3×10−6, Moderate vs. High p=6.0×10−6, df=2, n=5 per condition). This confirms the results from Figure 3, and strongly suggests that responses in the Hargreaves radiant heat assay are provoked by an increase of roughly 6.3°C from a dynamic set point.

Figure 4. Heat responses in mice are prompted by an increase in temperature from an adjustable baseline.

A. Withdrawal latency in the Hargreaves assay with different active intensities. Mice tested using Low, Moderate, or High active intensities have different withdrawal latencies (1-way ANOVA main effect p=9.8×10−15, Low vs. Moderate p=2.1×10−13, Low vs. High p<2×10−16, Moderate vs High p=1.1×10−6; ***p<0.001, df=1, n=9 per group)

B. Schematic for measuring the heat stimulus on the Hargreaves apparatus. The mouse paw is held to the glass on top of a thin filament thermocouple using laboratory tape.

C. Temperatures generated at the glass/hindpaw interface by the Hargreaves with different active intensities. Dotted lines mark the temperature at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=5 per group.

D. Glass temperature at the average withdrawal latency for the active intensities (marked in 4C at the dotted lines). The temperature at withdrawal is not significantly different in each condition (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test not significant n=5 per group)

E. Temperature change from baseline (TCFB) temperature through the course of the Hargreaves stimulus. The dotted line indicates the TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=5 per group.

F. TCFB at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 4E at the dotted lines). The TCFB at withdrawal is not significantly different between the conditions (1 -way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test not significant n=5 per group)

G. Rate of temperature change (ROTC) of temperature through the course of the Hargreaves stimulus. The dotted lines mark the ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for wild-type mice under that condition. n=5 per group. There is no significant difference between the ROTC in these conditions, but the peak ROTC is reached long before the average withdrawal (dotted lines).

H. ROTC at the average withdrawal latency for each condition (marked in 4G at the dotted lines). The ROTC at withdrawal is not significantly different between the conditions (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; main effect p=7.7×107, Low vs. High p=1.3×10−6, Moderate vs. High p=6.0×106, df=2, n=5 per condition). All data presented are mean±standard error.

Environmental temperature adjustment is dependent on TRP channels

To test the hypothesis that thermo-TRP channels allow mice to adjust the dynamic range of temperature sensation, we used the eCPA to test TrpA1-KO, TrpM8-KO, and TrpA1-TrpM8 double KO (dKO) mice.

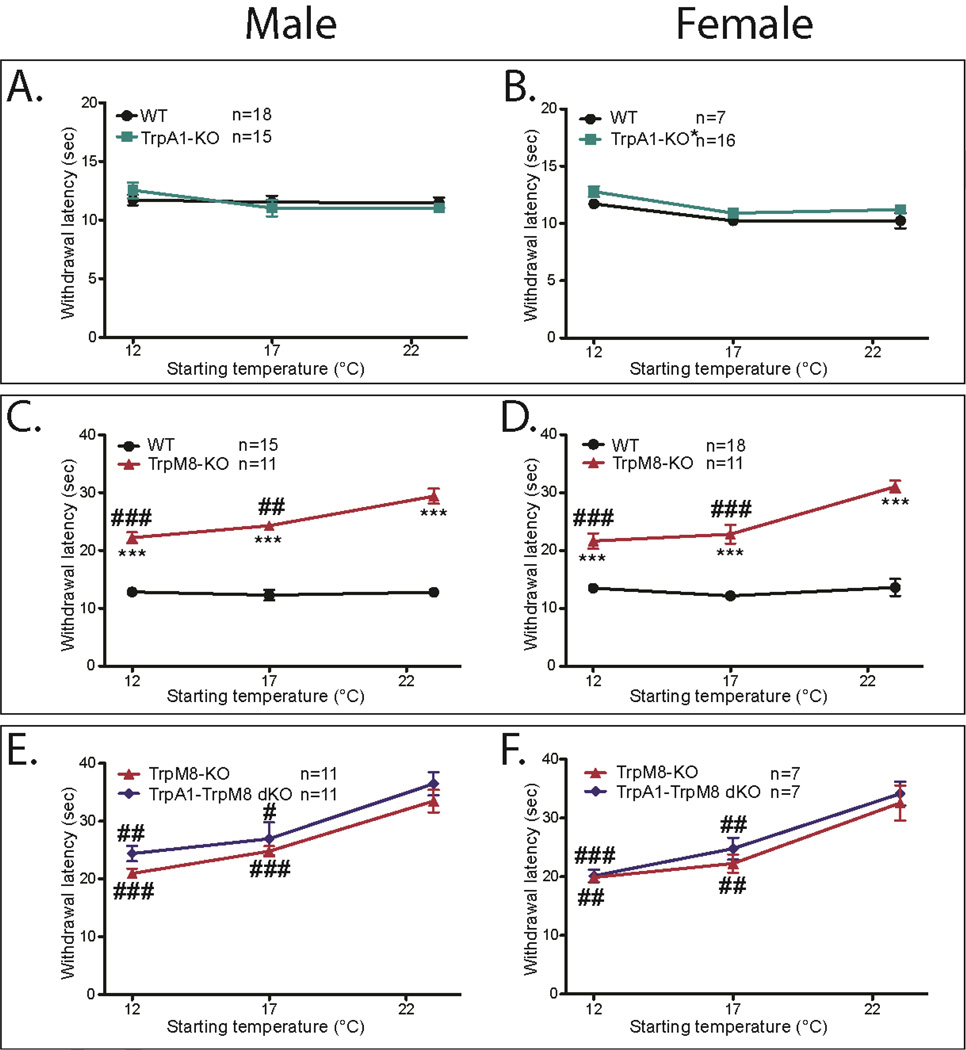

Male TrpA1-KO had similar withdrawal latencies to wild-type littermates (Figure 5A), while female TrpA1-KO had a small but statistically significant increase in withdrawal latency compared to their wild-type littermates at all starting temperatures measured (Figure 5B, TrpA1-KO 23 °C=11.2s±.4, 17°C= 10.9s±.4, 12°C=12.8s±.5, WT 23°C=10.2s±0.7, 17°C=10.2s±-.4, 12°C=11.7s±0.3; 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p=0.05, no individual points significant; df=1, n=6 WT and 15 KO).

Figure 5. TrpM8-KO mice have prolonged eCPA withdrawal latencies, while TrpA1-KO mice have normal eCPA latencies.

A. There is no difference between TrpA1-KO and WT male littermates at any of the temperature ranges tested (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, not significant n=18WT and 15KO)

B. TrpA1-KO females have slightly but significantly increased withdrawal latencies compared with their WT littermates(2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p=.05, no individual points significant; *p<0.01, df=1, n=6WT and 15KO)

C. TrpM8-KO males have significantly increased withdrawal latencies compared with their WT littermates at all starting temperatures (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p<2×10−16, 12°C p=1.1×10−9, 17°C p=6.9×10−10, 23°C p=7.38×10−12; ***p<0.001 df=1, n=15WT and 11KO). TrpM8-KO males exhibit shorter withdrawal latencies as the starting temperature of the glass decreases (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p=1.5×10−5, 12°C vs. 23°C p=6×105, 17°C vs. 23°C p=.004; ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 df=1 n=15WT and 11KO)

D. TrpM8-KO females have significantly increased withdrawal latencies compared with their WT littermates at all starting temperatures (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p<2×10−16, 12°C p=4.2×10−6, 17°C p=4.6×10−8, 23°C p=3.4×10−9; ***p<0.001 df=1, n=18WT and 11KO). TrpM8-KO males exhibit shorter withdrawal latencies as the starting temperature of the glass decreases (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p=3.6×10−5 12°C vs. 23°C p=9.25×105, 17°C vs. 23°C p=.0005; ###p<0.001 df=1, n=11 males and 11 females)

E. TrpA1-M8 dKO males have no significant increase in withdrawal latency compared with their WT littermates at all starting temperatures (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, not signficant). Both dKO and TrpM8-KO males exhibit shorter withdrawal latencies as the starting temperature the glass decreases (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, Male TrpM8-KO main effect=2.9×10−7, 12°C vs. 23°C p=1×10−6 17 vs 23°C p=0.0002 df=1 n=10; Male dKO main effect p=0.0007, 12°C vs 23°C p=0.003, 17°C vs 23°C p=.04; df=1 n=10 ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001)

F. TrpA1-M8 dKO females have no significant increase in withdrawal latency compared to their WT littermates at all starting temperatures (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, not signficant). Both dKO and TrpM8-KO females exhibit shorter withdrawal latencies as the starting temperature of the glass decreases (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect=.0005, 12°C vs 23°C p=0.002, 17°C vs 23°C p=.01; df=1 n=6; main effect=7.7×107, 12°C vs. 17°C p=.03, 12°C vs. 23°C p=4.7×106, 17°C vs. 23°C p=0.0008; df=1 n=6 ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001). All data presented are mean±standard error.

Both male and female TrpM8-KO had significantly increased withdrawal latencies at all temperature ranges compared to their wild-type littermates (Figure 5C–D Males TrpM8-KO 23°C=29.4s±1.3, 17°C=24.3s±0.7, 12°C=22.2s±0.9, WT 23°C=12.8s±0.7, 17°C=12.3s±0.9, 12°C=12.8s±0.5 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test main effect p<2×10−16, 12°C p=1.1×10−9, 17°C p=6.9×10−10, 23°C p=7.38×1012; df=1, n=15WT and 11KO. Females TrpM8-KO 23°C=30.9s±1.0, 17°C=22.8s±1.6, 12°C=21.6s±1.4, WT 23°C=13.6s±1.5, 17°C=12.2s±0.5, 12°C=13.5s±0.8; 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test main effect p<2×10−16, 12°C p=4.2×10−6, 17°C p=4.6×10−−8, 23°C p=3.4×10—9; df=1, n=18WT and 11KO). At 12°C or 17°C starting temperatures, TrpM8-KO mice withdrew significantly more quickly compared with the 23°C starting temperature, but still had significantly increased withdrawal latencies compared with their wild-type littermates. (Figure 5C–D, 1-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test; males main effect p=1.5×10−5 , 12°C vs. 23°C p=6×105, 17°C vs. 23°C p=0.004; females main effect p=3.6×10−5 12 °C vs. 23°C p=9.25×10−5, 17°C vs. 23°C p=0.0005; df=1, n=11 males and 11 females)

Since studies suggest that TRPA1 activates at lower temperatures than TRPM8, it is possible that intact TRPM8 signaling could mask a phenotype in the TrpA1-KO mice. To address this issue, we generated a TrpA1-TrpM8 double knockout mouse line, and tested the dKO mice along with their single TrpM8-KO littermates. For both male and female mice, the withdrawal latencies were not significantly different between dKO mice and TrpM8-KO mice (Figure 5E–F Males TrpA1-M8 dKO 23°C=36.5s±2.0, 17°C=29.9s±2.9, 12°C=24.4s±1.3, TrpM8-KO 23°C=33.5s±1.9, 17°C=24.8s±0.9, 12°C=20.9s±0.9; 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test; Females TrpA1-M8 dKO 23°C=34.2s±1.9, 17°C=24.8s±1.9, 12°C=20.2s±1.1, TrpM8-KO 23°C=32.6s±2.9, 17°C=22.3s±1.5, 12°C=19.9s±0.8; 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test). As seen in previous experiments, both the single TrpM8-KO and the TrpA1-TrpM8 dKO mice had lower withdrawal latencies at colder starting temperatures, suggesting impaired environmental adaptation (Figure 5E–F, 1-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test Male TrpM8-KO main effect=2.9×107, 12°C vs. 23°C p=1×10−6, 17 vs 23°C p=0.0002, df=1 n=10; Male dKO main effect p=0.0007, 12°C vs 23°C p=0.003, 17°C vs 23°C p=.04, df=1 n=10; Female |TrpM8-KO main effect=.0005, 12°C vs 23°C p=0.002, 17°C vs 23°C p=.01, df=1 n=6; Female dKO main effect=7.7×10−7, 12°C vs. 17°C p=.03, 12°C vs. 23°C p=4.7×10−6, 17°C vs. 23 °C p=0.0008, df=1 n=6). These results suggest that TRPA1 may not play a central role in baseline cold responsiveness or adaptation, and that TRPM8 is crucial to both normal cold responsiveness and cold adaptation.

Environmental temperature adjustment requires PLC activity

Previous work in vitro has suggested that depletion of membrane PIP2 by Ca2+-activated phospholipase C δ (PLCδ) leads to decreased TRPM8 sensitivity, and that this process is critical in adaptation of cold temperature responses [6,9,31]. To test whether this hypothesis is supported in vivo, we modified the eCPA procedure to allow testing cold thresholds during the adaptation process, as the plate is cooling. Briefly, mice are acclimated and withdrawal latencies are tested at room temperature (Figure 6A). After the baseline measurements, the dry ice-filled aluminum containers are placed on the glass and withdrawal latencies are measured as the glass cools in order to assess cold responsiveness as cold adaptation is occurring. Under normal conditions, mice adapted to the cooling ambient temperature of the eCPA faster than could be measured with this protocol, showing no change in withdrawal latency as the plate cooled (Figure 6B, 0 min=12.13s±0.8, 30 min=12.1s±1.6, 60 min=13.2s±1.1, 90 min=10.8s±1.2 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test p>0.05, n=6)

Then, to assess whether PLC activity was required for rapid adaptation to cooling ambient temperature, we injected the PLC inhibitor U73122, or an inactive analog U73343 into the hindpaw while the glass was cooling. We utilized a concentration of U73122 that has previously been used to locally inhibit intraplantar PLC in vivo [43].

The intraplantar injections of U73122 or U73343 were administered before the ambient temperature was cooled in order to inhibit the local PLC before the cold-induced hydrolysis of PIP2 began (Figure 6C). Once the glass plate cooling was started, the eCPA withdrawal latency was frequently measured in order to assess whether inhibiting intraplantar PLC would affect cold adaptation as it happened (Figure 6D). The mice that were given intraplantar injections of 0.5 nmol U73122 had significantly lower withdrawal latencies at the 30min timepoint compared with baseline, suggesting impairment of the adaptation process (Figure 6D, baseline=11.29s±.53s, 30min=8.09s±.1.17s; 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test, main effect p=0.02, individual baseline vs. 30min p=.02; df=1, n=9). In contrast, mice that received intraplantar injections of the control compound U73343 had no change in withdrawal latency at 30min (Figure 6D , baseline=11.56s±.62s, 30min=12.242±1.40s; 1-wav ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test, no main effect n=7). Taken together, these data suggest that TrpM8-dependent cold adaptation in vivo is at least partially dependent on PLC activity.

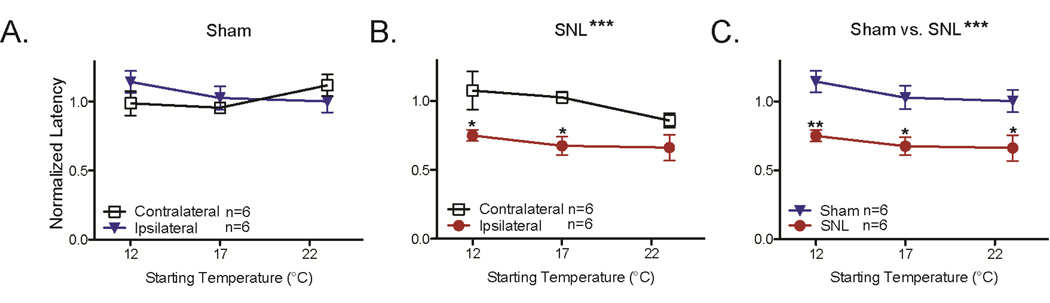

Spinal nerve ligation (SNL)-induced cold hypersensitivity does not affect cold adaptation

The mechanisms of cold hypersensitivity are not fully understood. One possibility is that neuropathic injuries such as the Spinal Nerve Ligation (SNL) procedure compromise the ability to adapt to ambient temperatures, resulting in increased cold sensitivity during cold stimuli. To test this hypothesis, we measured the eCPA withdrawal latencies at three temperatures (12°C, 17°C, 23°C) before and after performing the spinal nerve ligation (SNL) procedure. Animals that underwent the sham procedure had no change in withdrawal latency between the contralateral and ipsilateral paws (Figure 7A, 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test 12°C Ipsi=1.1±.08 Contra=0.99±.09, 17°C Ipsi=1.03±.09 Contra=.96±.02, 23°C Ipsi=1.0±.08 Contra=1.1±.08). Animals that underwent the SNL procedure had decreased withdrawal latencies on the SNL paw compared to the contralateral paw (Figure 7B, 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test main effect ***p=0.0003, 12°C Ipsi=.75±.04 Contra=1.07±.14 *p<0.05, 17°C Ipsi=.68±.06 Contra=1.03±.04 *p<0.05, 23°C Ipsi=.66±.09 Contra=.86±.05 p>0.05). Although robust cold hypersensitivity was observed after the SNL procedure, there was no effect of changing the ambient temperature on the cold hypersensitivity (Figure 7B, 2-way ANOVA, p>0.05 for glass plate temperature). This suggests that SNL-induced cold hypersensitivity does not affect the ability to adapt to cold ambient temperatures.

Figure 7. SNL hypersensitivity is unaffected by changes in ambient temperature.

A. Mice were tested at 12°C, 17°C, and 23°C before and after the sham procedure. Post-surgical withdrawal latencies were normalized to the baseline values. There was no significant change in withdrawal latency for either ipsilateral or contralateral paws after the sham surgical procedure (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, n=6 per group)

B. Mice were tested at 12°C, 17°C, and 23°C before and after the SNL procedure. Postsurgical withdrawal latencies were normalized to the baseline values. The ipsilateral paws had significantly lower withdrawal latencies than the contralateral paws (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test main effect ***p=0.0003, 12°C Ipsi=.75±.04 Contra=1.07±.14 *p<0.05, 17°C Ipsi=.68±.06 Contra=1.03±.04 *p<0.05, 23°C Ipsi=.66±.09 Contra=.86±.05 p>0.05). Changing the starting temperature of the glass plate had no impact on the withdrawal latency of either the ipsilateral or contralateral paws (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p>0.05).

C. Direct comparison of the ipsilateral paws of mice that received Sham or SNL procedures. Mice were tested at 12°C, 17°C, and 23°C before and after the surgical procedure. Post-surgical withdrawal latencies were normalized to the baseline values. The SNL mice had significantly lower withdrawal latencies than the Sham mice (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test main effect ***p<0.0001, 12°C Sham=1.1±.08 SNL=.75±.04 **p<0.01, 17°C Sham=1.03±.09 SNL=.68±.06 *p<0.05, 23°C Sham=1.0±.08 SNL=.66±.09 p>0.05). Changing the starting temperature of the glass plate had no impact on the withdrawal latency of either the sham or SNL mice (2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test, main effect p>0.05). All data presented are mean±standard error.

Discussion

Temperature adaptation is a necessary daily function for mammals. Mice in the wild need to sense cold stimuli in a variety of environmental settings, so as to be able to seek out cooler areas in the hot summer and to avoid dangerously colder areas in the winter. While climate control has made this less of a struggle of life and death for humans, aberrant temperature adaptation could lead to inappropriate thermal pain or an inability to detect dangerous thermal stimuli.

We find that wild-type mice quickly adapt their response latency to cold stimuli when environmental temperature changes. This finding is consistent with early microneurography studies, which showed that sustained cold stimuli provoked a rapid burst of activity followed by quick adaptation and decreased firing [18,29,30]. In our efforts to further characterize this phenomenon, we found that mouse responses to both warm and cold stimuli depend on changes from a dynamic temperature ‘set-point’. Animals are able to adjust this ‘set-point’ in response to changes in the ambient temperature, which maintains their ability to detect subtle changes in temperature across a wide range of conditions. This is one of the first demonstrations and quantifications in vivo that thermal response thresholds are not based on a specific temperatures, despite early hints that this might be the case [36,37]. Regarding heat sensation, we present strong evidence that mice respond to an increase of roughly 6.3°C from this dynamic ‘set-point’. With regard to cold sensation we show that that mice are responding to a 1.2°C decrease from a dynamic ‘set-point’ which can be modulated by environmental conditions. These results are also consistent with recent work by Hoon et. al suggesting that temperature responsiveness is reliant on aversive and attractive cues from both warm- and cold-sensitive neurons [28]. Modulating the dynamic ‘set-points’ of each population separately or in tandem may be essential to maintaining the balance between the populations and preserving thermal sensitivity and adaptability.

Previous work has demonstrated that TRPM8 is essential for adaptation of cold-induced currents in dissociated dorsal root ganglion cultures [9]. Our findings demonstrate for the first time in vivo that TRPM8 is essential for full adaptation to colder ambient conditions. Both male and female TrpM8-KO mice showed a significantly impaired ability to adjust their cold response thresholds in response to environmental temperature changes. Despite the obvious deficits in both cold sensation and adaptation to environmental stimuli, TrpM8-KO and TrpA1-TrpM8 dKO mice had consistent and robust responses to the eCPA stimuli in all conditions. This suggests the existence of other, possibly non-Trp channel mediators of cold responsiveness.

There have been conflicting reports on the role of TRPA1 in cold sensation in the literature [2,12,14,33]. Interestingly, male TrpA1-KO mice show no deficit in cold responses at any ambient temperature range, while the female TrpA1-KO mice exhibit a small but significant increase in withdrawal latency at all temperature ranges. This is consistent with some previous findings that female but not male TrpA1-KO mice had more significant deficits in cold responsiveness to the acetone test [17] compared to male TrpA1-KO mice, although other reports have found no sex-dependent difference [2].

Neither the male nor female TrpA1-TrpM8 dKO mice had significantly higher withdrawal latencies than their TrpM8-KO littermates at any ambient temperature condition. Given the small but significant trend in the TrpA1-KO females, it is difficult to make definitive conclusions on the role of TrpA1 in cold sensation based on these data. However, the TrpA1-TrpM8 dKO mice also show impaired cold adaptation as was seen with TrpM8-KO mice, confirming that TRPM8 plays an essential role in this process.

Previous work in vitro has suggested that the hydrolysis of PIP2 during cold adaptation leads to changes in TRPM8 activity [6,9,31]. Our findings in this study suggest that PLC activity is important for the modulation of this dynamic set-point in vivo that governs adaptation to environmental cold responses. Although U73122 has been shown to have non-PLC mediated effects [11], our results are consistent with the in vitro model this set-point is controlled through PIP2 modulation of TRPM8. Although additional adaptation of cold responsiveness may occur spinally or supra-spinally, our results are the first in vivo evidence that as the ambient temperature decreases, PLC-mediated hydrolysis of membrane PIP2 modulates cold responsiveness in DRG neurons [6,9].

Summary.

We measure the rapid adaptation of mice to changing environmental conditions that preserves temperature responsiveness. This process is TRPM8 dependent, and mediated by Phospholipase C.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge contributions from the entire Gereau Lab, especially Bryan Copits, and Daniel O’Brien. This work is supported by NINDS fund 1F31NS078852 to DSB, NINDS fund NS042595 to RG, and an NIH Director’s Transformative Research award (R01NS081707) to RG.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributions: DSB and RWG planned all experiments and wrote the manuscript, DSB and JPG performed all experiments, SKV managed mouse colonies, AD and GMS provided transgenic mice, and all authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bang S, Kim KY, Yoo S, Kim YG, Hwang SW. Transient receptor potential A1 mediates acetaldehyde-evoked pain sensation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26:2516–2523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bautista DM, Siemens J, Glazer JM, Tsuruda PR, Basbaum AI, Stucky CL, Jordt SE, Julius D. The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature. 2007;448:204–208. doi: 10.1038/nature05910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner DS, Golden JP, Gereau RW. A Novel Behavioral Assay for Measuring Cold Sensation in Mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caterina MJ, Rosen TA, Tominaga M, Brake AJ, Julius D. A capsaicin-receptor homologue witha high threshold for noxious heat. Nature. 1999;398:436–441. doi: 10.1038/18906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colburn RW, Lubin ML, Stone DJ, Jr, Wang Y, Lawrence D, D’Andrea MR, Brandt MR, Liu Y, Flores CM, Qin N. Attenuated cold sensitivity in TRPM8 null mice. Neuron. 2007;54:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels RL, Takashima Y, McKemy DD. Activity of the neuronal cold sensor TRPM8 is regulated by phospholipase C via the phospholipid phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:1570–1582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807270200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhaka A, Murray AN, Mathur J, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, Patapoutian A. TRPM8 is required for cold sensation in mice. Neuron. 2007;54:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez JA, Skryma R, Bidaux G, Magleby KL, Scholfield CN, McGeown JG, Prevarskaya N, Zholos AV. Voltage- and cold-dependent gating of single TRPM8 ion channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2011;137:173–195. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita F, Uchida K, Takaishi M, Sokabe T, Tominaga M. Ambient Temperature Affects the Temperature Threshold for TRPM8 Activation through Interaction of Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:6154–6159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5672-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauchan P, Andoh T, Kato A, Kuraishi Y. Involvement of increased expression of transient receptor potential melastatin 8 in oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;458:93–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollywood Ma, Sergeant GP, Thornbury KD, McHale NG. The PI-PLC inhibitor U-73122 is a potent inhibitor of the SERCA pump in smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160:1293–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karashima Y, Talavera K, Everaerts W, Janssens A, Kwan KY, Vennekens R, Nilius B, Voets T. TRPA1 acts as a cold sensor in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:1273–1278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808487106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowlton WM, Bifolck-Fisher A, Bautista DM, McKemy DD. TRPM8, but not TRPA1, is required for neural and behavioral responses to acute noxious cold temperatures and cold-mimetics in vivo. Pain. 2010;150:340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knowlton WM, Palkar R, Lippoldt EK, McCoy DD, Baluch F, Chen J, McKemy DD. A Sensory-Labeled Line for Cold: TRPM8-Expressing Sensory Neurons Define the Cellular Basis for Cold, Cold Pain, and Cooling-Mediated Analgesia. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:2837–2848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1943-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kremeyer B, Lopera F, Cox JJ, Momin A, Rugiero F, Marsh S, Woods CG, Jones NG, Paterson KJ, Fricker FR, Villegas A, Acosta N, Pineda-Trujillo NG, Ramirez JD, Zea J, Burley MW, Bedoya G, Bennett DL, Wood JN, Ruiz-Linares A. A gain-of-function mutation in TRPA1 causes familial episodic pain syndrome. Neuron. 2010;66:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwan KY, Allchorne AJ, Vollrath MA, Christensen AP, Zhang DS, Woolf CJ, Corey DP. TRPA1 contributes to cold, mechanical, and chemical nociception but is not essential for hair-cell transduction. Neuron. 2006;50:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaMotte RH, Thalhammer JG. Response properties of high-threshold cutaneous cold receptors in the primate. Brain Res. 1982;244:279–287. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90086-5. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7116176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee H, Iida T, Mizuno A, Suzuki M, Caterina MJ. Altered thermal selection behavior in mice lacking transient receptor potential vanilloid 4. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:1304–1310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4745.04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leem JW, Willis WD, Chung JM. Cutaneous sensory receptors in the rat foot. J. Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1684–1699. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu T, Ji RR. Oxidative stress induces itch via activation of transient receptor potential subtype ankyrin 1 in mice. Neurosci. Bull. 2012;28:145–154. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macpherson LJ, Xiao B, Kwan KY, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Hwang S, Cravatt B, Corey DP, Patapoutian A. An ion channel essential for sensing chemical damage. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:11412–11415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3600-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madrid R, Donovan-Rodriguez T, Meseguer V, Acosta MC, Belmonte C, Viana F. Contribution of TRPM8 channels to cold transduction in primary sensory neurons and peripheral nerve terminals. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:12512–12525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3752-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandadi S, Sokabe T, Shibasaki K, Katanosaka K, Mizuno A, Moqrich A, Patapoutian A, Fukumi-Tominaga T, Mizumura K, Tominaga M. TRPV3 in keratinocytes transmits temperature information to sensory neurons via ATP. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:1093–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNamara CR, Mandel-Brehm J, Bautista DM, Siemens J, Deranian KL, Zhao M, Hayward NJ, Chong JA, Julius D, Moran MM, Fanger CM. TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:13525–13530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705924104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moqrich A, Hwang SW, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, Murray AN, Spencer KS, Andahazy M, Story GM, Patapoutian A. Impaired thermosensation in mice lacking TRPV3, a heat and camphor sensor in the skin. Science (80-. ) 2005;307:1468–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1108609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrus M, Peier AM, Bandell M, Hwang SW, Huynh T, Olney N, Jegla T, Patapoutian A. A role of TRPA1 in mechanical hyperalgesia is revealed by pharmacological inhibition. Mol. Pain. 2007;3:40. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pogorzala LA, Mishra SK, Hoon MA. The cellular code for Mammalian thermosensation. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:5533–5541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5788-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulos DA, Lende RA. Response of Trigeminal Ganglion Neurons to Thermal Stimulation of Oral-Facial Regions I. Steady-state Response. J. Neurophysiol. 1970;33:508–517. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poulos DA, Lende RA. Response of Trigeminal Ganglion Neurons to Thermal Stimulation of Oral-Facial Regions II. Temperature Change Response. J. Neurophysiol. 1970;33:518–526. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Michailidis I, Logothetis DE. PI(4,5)P2 regulates the activation and desensitization of TRPM8 channels through the TRP domain. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:626–634. doi: 10.1038/nn1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simone Da, Kajander KC. Responses of cutaneous A-fiber nociceptors to noxious cold. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2049–2060. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.2049. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9114254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Story GM, Peier AM, Reeve AJ, Eid SR, Mosbacher J, Hrici TR, Earley TJ, Hergarden AC, Andersson DA, Hwang SW, McIntyre P, Jegla T, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. ANKTM1, a TRP-like channel expressed in Nociceptive Neurons, is activated by Cold Temperatures. Cell. 2003;112:819–829. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Z, Kim A, Masuch T, Park K, Weng H, Wetzel C, Dong X. Pirt functions as an endogenous regulator of TRPM8. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2179. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Than JY-XL, Li L, Hasan R, Zhang X. Excitation and modulation of TrpA1, TrpV1, and TrpM8 channel-expressing neurons by the pruritogen chloropquine. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.450072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tillman D, Treede R, Meyer RA, Campbell JN. Response of C fibre nociceptors in the anaesthetized monkey to heat stimuli- estimates of receptor depth and threshold. J. Physiol. 1995;485:753–765. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tillman D, Treede R, Meyer RA, Campbell JN. Response of C fibre nociceptors in the anaesthetized monkey to heat stimuli-correlation with pain threshold in humans. J. Physiol. 1995;485:767–774. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vilceanu D, Honore P, Hogan QH, Stucky CL. Spinal nerve ligation in mouse upregulates TRPV1 heat function in injured IB4-positive nociceptors. J. Pain. 2010;11:588–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voets T, Droogmans G, Wissenbach U, Janssens A, Flockerzi V, Nilius B. The principle of temperature-dependent gating in cold- and heat-sensitive TRP channels. Nature. 2004;430:748–754. doi: 10.1038/nature02732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson SR, Gerhold KA, Bifolck-Fisher A, Liu Q, Patel KN, Dong X, Bautista DM. TRPA1 is required for histamine-independent, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor-mediated itch. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nn.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson SR, Nelson AM, Batia L, Morita T, Estandian D, Owens DM, Lumpkin EA, Bautista DM. The ion channel TRPA1 is required for chronic itch. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:9283–9294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5318-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xing H, Chen M, Ling J, Tan W, Gu JG. TRPM8 mechanism of cold allodynia after chronic nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:13680–13690. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2203-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H, Cang C-L, Kawasaki Y, Liang L-L, Zhang Y-Q, Ji R-R, Zhao Z-Q. Neurokinin-1 receptor enhances TRPV1 activity in primary sensory neurons via PKCepsilon: a novel pathway for heat hyperalgesia. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:12067–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao M, Isami K, Nakamura S, Shirakawa H, Nakagawa T, Kaneko S. Acute cold hypersensitivity characteristically induced by oxaliplatin is caused by the enhanced responsiveness of TrpA1 in mice. Mol. Pain. 2012;8 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]