Abstract

Background

Despite growing interest in depression in young children, little is known about which variables predict the onset of depression in early childhood. We examined a range of predictors of the onset of depression diagnoses in a multi-method, multi-informant longitudinal study of a large community sample of young children from age 3 to 6.

Methods

Predictors of the onset of depression at age 6 were drawn from five domains assessed when children were 3 years old: child psychopathology (assessed using a parent diagnostic interview), observed child temperament, teacher ratings of peer functioning, parental psychopathology (assessed using a diagnostic interview), and psychosocial environment (observed parental hostility, parent reported family stressors, parental education).

Results

A number of variables predicted the onset of depression by age 6, including child history of anxiety disorders, child temperamental low inhibitory control, poor peer functioning, parental history of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders, early and recent stressful life events, and less parental education.

Conclusions

Predictors of the onset of depression in early childhood tend to be similar to those identified in older youth and adults, and support the feasibility of identifying children in greatest need for early interventio

Keywords: Early childhood, depression, predictors

Introduction

Depression in early childhood was first examined systematically using rating scales by Kashani and colleagues over 25 years ago (Kashani & Carlson, 1985; Kashani, Holcomb, & Orvaschel, 1986). They reported that although depression could be diagnosed in preschoolers, it was either extremely rare or inadequately captured by existing diagnostic criteria. More recently, Luby and colleagues identified a group of children who, by parent interview, met modified criteria for depression (e.g., relaxing the two-week duration criterion). These children were more likely to have a family history of mood disorders, greater cortisol reactivity to laboratory stress, and significant impairment compared to non-depressed peers, and also had a high rate of recurrence over a two-year follow-up (Luby et al., 2002; 2003; 2009a; 2009b).

These data indicate that depression can be diagnosed in early childhood. However, little is known about factors that prospectively predict the onset of the disorder during this developmental period, and whether the predictors are similar to those in other stages of development. The most robust predictors of depression in adolescents and adults include female gender, history of anxiety disorders, family history of mood disorders, and life stress (e.g., Eaton et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2013; Shanahan, Copeland, Costello, & Angold, 2011).

A few studies have examined predictors of depressive symptoms in early childhood. In a large birth cohort, Najman and colleagues (2005) found that low socioeconomic status, maternal health problems in pregnancy, marital instability and conflict, maternal anxiety, poor child health, and less positive maternal attitudes toward caregiving, generally assessed six months after childbirth, predicted children's depressive symptoms at age 5. Côté et al. (2009) reported that difficult temperament, maternal history of major depressive disorder (MDD), family dysfunction, and low parental self-efficacy assessed when the child was six months old predicted a high and increasing trajectory of internalizing symptoms from ages 1½-5. In a sample of 3-6 year-old children, Luby and colleagues (Luby, Belden, & Spitznagel, 2006) reported that family history of mood disorders and number of stressful life events predicted depressive symptoms six months later. Of these studies, only Luby and colleagues used a diagnostic interview to assess depression. Moreover, these studies all examined predictors of increases in depressive symptoms, rather than predictors of the onset of depressive disorders in young children.

We report a multi-method (interviews, laboratory assessments, and questionnaires), multi-informant (mother, father, and teacher report, and behavioral observation) longitudinal study of predictors of the onset of depressive disorders in a large community sample of young children. Efforts to delineate an early childhood depressive phenotype are relatively recent (Luby et al., 2002). In this study, we defined the phenotype as meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for MDD as developmentally modified by Luby et al. (2002), dysthymic disorder, or depression not otherwise specified (DNOS) with clinically significant impairment. Following DSM-IV-TR, either distress or impairment was required for MDD and dysthymia. However, as DNOS is a more amorphous category, we required impairment for the diagnosis. Consistent with a developmental psychopathology framework (Cicchetti & Toth, 2009) and research in older youth and adults (Eaton et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2013), we hypothesized that the onset of depressive disorder at age 6 would be predicted by variables from multiple domains, including child non-mood psychopathology, dysfunctional temperament traits, poor peer functioning, parental psychopathology, and psychosocial stressors.

Method

Participants

Families with a 3-year-old child living within 20 miles of Stony Brook, NY were identified using commercial mailing lists. Children with at least one biological parent and without significant medical disorders or developmental disabilities were eligible. 541 parents were interviewed regarding their 3-year-old child (time 1; M age=3.6, SD=0.3 years), and 456 of these parents (84.3%) were interviewed again when their child turned 6 (time 2; M age=6.1, SD=0.4 years). Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the sample. The study was approved by the Stony Brook University Institutional Review Board and families were compensated. Research staff conducting each assessment were blind to other variables in both assessments.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Demographic Variable | Age 3 assessment | Age 6 assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Child mean age: years (SD) | 3.6 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.4) |

| Child sex: female % (n) | 46.3 (211) | |

| Child race/ethnicity: % (n) | ||

| White/non-Hispanic | 86.6 (395) | |

| Non-White or Hispanic | 13.4 (61) | |

| Biological parents' marital status: % (n) | ||

| Married | 94.5 (431) | 89.7 (409) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 1.8(8) | 6.8 (31) |

| Never married | 3.7 (17) | 3.5 (16) |

| Parents' education: % graduated college (n)a | ||

| Mother | 57.2 (257) | 59.9 (244) |

| Father | 46.6 (206) | 47.8 (192) |

Note: N = 456.

At the age 3 assessment, 1.5% (n = 7) of the mothers and 3.1% (n = 14) of the fathers did not indicate their education level. At the age 6 assessment, 10.7% (n = 49) of the mothers and 11.8% (n = 54) of the fathers did not indicate their education level.

Six children (1.1%) met criteria for a PAPA depression diagnosis (MDD, dysthymia, or DNOS) at age 3 (none of whom met criteria again at age 6); these children were excluded from the analyses to preserve temporal precedence of the predictor variables to depression at age 6.

Measures

Child Psychopathology

The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA; Egger, Ascher, & Angold, 1999) is a reliable, developmentally sensitive interview designed to assess DSM-IV-TR disorders. The PAPA uses a structured format and an interviewer-based approach, applying a priori guidelines for rating symptoms using a detailed glossary. Diagnoses are derived using algorithms. A 3-month primary period is used to enhance recall. Although the PAPA was designed for 2-5-year-olds, it has been used to assess depression in children as old as 8 years (Luby et al., 2009b). We used the PAPA at both age 3 and 6 to maintain comparability across assessments, and because children had just turned 6 at the follow-up.

Disorders included MDD with modified criteria (Luby et al., 2002), dysthymia, DNOS, anxiety disorders (specific phobia, separation anxiety, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, selective mutism), and behavioral disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD] and oppositional defiant disorder [ODD]) as implemented in the PAPA. Interviews were conducted with the primary caregiver by telephone at age 3 (97.6% mothers) and in person at age 6 (92.1% mothers; see Bufferd, Dougherty, Carlson, Rose, & Klein, 2012 for rates of specific disorders and details about both assessments). At age 6, 33 children (7.24%) met criteria for a depression diagnosis (MDD, dysthymia, or DNOS).

To examine interrater reliability at age 3, a second rater from the pool of interviewers independently rated 21 audiotapes of PAPA interviews. Kappa was 1.00 for all diagnoses, including specific phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia, separation anxiety, GAD, ADHD, and ODD. At age 6, kappa for depressive disorders was 0.64 (35 audiotapes). Given the small number of cases (n=5), kappa may underestimate agreement; using an intraclass correlation (ICC) for the summed depression symptom scale, agreement was .95.

Child Temperament

Temperament was assessed at age 3 using the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB; Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, 1995). Each child participated in a standardized set of 12 tasks designed to elicit temperament-relevant expressions of positive and negative affectivity and inhibitory control. Low positive affect, high negative affect, and poor inhibitory control are associated with risk for depression (Caspi, Moffitt, Newman, & Silva, 1996; Clark & Watson, 1991; Durbin, Klein, Hayden, Buckley, & Moerk, 2005; Laceulle et al., 2013). Examples of episodes included “Popping Bubbles” in which the child and experimenter played with a bubble-shooting toy (to elicit positive affect); “Box Empty” in which the child was given a wrapped box to open under the impression that a toy was inside for the child to keep (to elicit sadness and anger); “Stranger Approach” in which the child was briefly left alone in the room before a male accomplice entered and slowly approached (to elicit fear); and “Snack Delay” in which the child was told to wait for the experimenter to ring a bell before eating a snack, and the delay was systematically increased (to assess inhibitory control).

Each task was videotaped in the laboratory and later coded on many variables. Coefficient alphas for the individual variables ranged from .50 to .87 (median = .70) and ICCs for interrater reliability ranged from .40 to .92 (median = .75, n = 35). Principal components analysis was used to reduce the number of variables (see Dougherty et al., 2011 for details). The components, and the items that loaded most strongly on them, included dysphoria (sadness, anger), fear/inhibition (behavioral inhibition, fear), exuberance (positive affect, interest), and low inhibitory control (impulsivity, noncompliance).

Peer functioning

Teachers provided ratings of children's social competence and popularity at age 3. These measures were available for a subset of the sample (n=185-192), largely because many children were not in a formal school or daycare program at this age. Children's social competence (7 items; M=11.74, SD=4.77, α=.87) was measured using the Ratings of Children's Behaviors scale (Eisenberg et al., 1996). Children's popularity (3 items; M=11.93, SD=2.87, α=.81) was assessed with the Teacher's Estimation of Child's Peer Status measure (Lemerise & Dodge, 1988). Given the high correlation between these variables in our sample (r=−.79), the scores were standardized then combined (children's popularity was reverse scored) to reflect an overall teacher rating of peer functioning (higher scores indicate poorer functioning).

Parental Psychopathology

When children were 3 years old, their biological parents were interviewed by telephone using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV non-patient version (SCID-NP; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1996), a widely used semi-structured diagnostic interview for adults with well-established reliability and validity. SCIDs were completed by M.A.-level psychologists, and were obtained from 452 (99.1%) mothers and 380 (83.3%) fathers. When parents were unavailable, family history interviews (Andreasen, Endicott, Spitzer, & Winokur, 1977) were conducted with the co-parent; family history data were obtained for one (0.2%) mother and 69 (15.1%) fathers. Interrater reliability (kappa) of SCID lifetime mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders were .93, .91, and 1.00, respectively (n=30). Rates of lifetime mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders were 32.9%, 32.9%, and 22.6% in mothers and 15.4%, 18.4%, and 33.3% in fathers, respectively. These rates are generally similar to the National Comorbidity Study-Replication (NCS-R) rates for this age group (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). For the analyses, parental psychopathology was coded as neither parent has the diagnosis or at least one parent has the diagnosis.

Psychosocial Environment

When children were age 3, observed parental hostility (e.g., expressions of anger, frustration, criticism toward the child) was assessed in the laboratory using a modified version of the Teaching Tasks battery (Egeland et al., 1995). 452 (99.1%) children and one parent (92.8% mothers) participated in six standardized interaction tasks (book-reading, naming things with wheels, block-building, matching game, maze completion, and playtime). Interactions were videotaped and coded for parental hostility on a five-point scale and ratings were averaged across tasks. The hostility scale (M=1.20, SD=0.35) showed good internal consistency (α=.76) and interrater reliability (ICC=.83, n=55). However, it was highly skewed; more than half of parents displayed no hostility (n=239, 52.4%). Hence, this variable was dichotomized (0=no displays of hostility; 1=hostility displayed).

Stressful life events involving the child and immediate family members, such as illness, injury, loss of a loved one, and extended separations, were assessed using the PAPA. We used two measures of life events: early life stressors from the time the child was born until the age 3 interview (M=4.05, SD=2.74, Range 0-15; interrater ICC=1.00) and proximal life stressors in the 12 months prior to the age 6 interview (M=2.30, SD=1.76, Range 0-10; interrater ICC=.90). Finally, parental education was assessed when children were 3 years old and included as an index of socioeconomic status (in 70.2% of the families at least one parent graduated college; see Table 1).

Data Analysis

Predictors included variables from each of five domains: child psychopathology (age 3 anxiety and behavior disorders), observed child temperament (age 3 dysphoria, fear/inhibition, exuberance, and low inhibitory control), age 3 teacher ratings of peer functioning, parental psychopathology (parental history of depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders from the age 3 assessment), and the psychosocial environment (age 3 observed parental hostility, life stressors through age 3, life stressors in the 12 months prior to the age 6 assessment, and parental education).

First, bivariate correlations were computed between predictors. Next, we conducted logistic regression analyses between each predictor and depression diagnosis at age 6. Exploratory analyses examined interactions of gender, parental psychopathology, and child temperament with early and recent stressors. Continuous variables were centered and cross-product terms were created to test interaction effects. Finally, variables with significant associations were entered into a final multiple logistic regression model to determine which predictors had unique effects1. Child race/ethnicity and sex were included as covariates in all logistic regression models. Data from teachers were excluded from the multivariate analysis due to the reduced sample size.

Results

Correlation and individual logistic regression analyses

Bivariate correlations between predictors are presented in Table 2. Results from the logistic regressions are presented in Table 3. Significant predictors of a depression diagnosis at age 6 included age 3 anxiety disorders; temperamental low inhibitory control; teacher-rated poor peer functioning; parental depression, anxiety, and substance disorders; early stressors; and stressors in the year before the age 6 assessment; and less parental education.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Between Independent Variables

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Sex | .00 | −.04 | −.07 | −.06 | .14* | .04 | −.29* | −.12 | .12* | −.01 | .08 | −.08 | .04 | .13* | −.05 | |

| 2. Race/ethnicity | -- | −.11* | −.02 | −.05 | .01 | .08 | −.12* | .00 | −.08 | −.07 | .07 | −.06 | −.13* | .01 | .08 | |

| Age 3 Dx | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 Anxiety | -- | .04 | .06 | .12* | −.19* | .03 | .03 | .05 | .02 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .02 | .08 | ||

| 4 ADHD or ODD | -- | .01 | −.06 | −.03 | .19* | .32* | .08 | .12* | .02 | .15* | .14* | .04 | .00 | |||

| Age 3 Temp | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 Dysphoria | -- | .24* | −.03 | .33* | .12 | .10* | −.01 | .00 | .00 | .06 | .02 | −.07 | ||||

| 6 Fear/ Inhibition | -- | −.08 | −.03 | −.09 | .14* | .03 | .07 | −.04 | .00 | −.01 | .04 | |||||

| 7 Exuberance | -- | −.06 | −.01 | −.06 | .01 | .02 | −.02 | −.03 | −.05 | −.10* | ||||||

| 8 Low inhibitory control | -- | .22* | .03 | .04 | −.12* | .14* | −.05 | −.02 | −.05 | |||||||

| Teacher Rating | ||||||||||||||||

| 9 Low Age 3 Peer Functioning | -- | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | .19* | .09 | .02 | −.06 | ||||||||

| Parental Dx History | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 Mood | -- | .31* | .15* | −.04 | .13* | .15* | −.03 | |||||||||

| 11 Anxiety | -- | .12* | −.04 | .05 | .13* | −.06 | ||||||||||

| 12 Substance | -- | .02 | .17* | .09 | .02 | |||||||||||

| Psychosocial Environment | ||||||||||||||||

| 13 Parental Hostility | -- | .06 | .04 | .06 | ||||||||||||

| 14 Early Stressors | -- | .18* | .03 | |||||||||||||

| 15 Recent Stressors | -- | −.07 | ||||||||||||||

| 16 Parental Education | -- | |||||||||||||||

Note.

p < .05. Tau-b correlations were computed for dichotomous variables. Sex 0=male;1=female. Race/ethnicity 0=white,non-Hispanic;1=non-white and/or Hispanic. Parental Education 0=no college degree;1=college degree. Temp=Temperament. Dx=diagnosis.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models for Each Predictor of Age 6 PAPA Depression Diagnosis

| Descriptives | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 3 Predictors | Non-depressed (n=423) | Depressed (n=33) | OR | 95% CI |

| Covariates | ||||

| Sex, % female | 45.6 | 54.5 | 1.43 | 0.70-2.91 |

| Race/ethnicity, % white | 87.7 | 72.7 | 0.37* | 0.17-0.85 |

| Child Psychopathology | ||||

| PAPA Anxiety disorder, % | 17.5 | 33.3 | 2.19* | 1.00-4.78 |

| PAPA Behavioral disorder, % | 9.7 | 18.2 | 2.15 | 0.82-5.59 |

| Child Temperament | ||||

| Dysphoria, M(SD) | −.01(.81) | .17(1.05) | 1.26 | 0.84-1.89 |

| Fear/inhibition, M(SD) | −.01(.98) | .07(1.11) | 1.06 | 0.73-1.53 |

| Exuberance, M(SD) | .04(.96) | −.01(.78) | 0.98 | 0.68-1.43 |

| Low inhibitory control, M(SD) | −.05(.96) | .39(1.27) | 1.58** | 1.12-2.21 |

| Peer Functioning | ||||

| Teacher rated poor peer functioning, M(SD) | −.16(1.77) | 1.98(2.49) | 1.63*** | 1.25-2.13 |

| Parental Psychopathology | ||||

| Parental depression, % | 39.7 | 60.6 | 2.14* | 1.02-4.47 |

| Parental anxiety, % | 41.6 | 69.7 | 3.10** | 1.43-6.71 |

| Parental substance use, % | 46.8 | 63.6 | 2.12* | 1.00-4.48 |

| Psychosocial Environment | ||||

| Parental hostility, % | 46.1 | 11.8 | 1.60 | 0.75-3.38 |

| Early stressors, M(SD) | 3.88(2.61) | 6.15(3.37) | 1.26*** | 1.12-1.42 |

| Recent stressors, M(SD) | 2.23(1.73) | 3.12(2.03) | 1.26** | 1.06-1.49 |

| One parent graduated college,% | 72.0 | 51.5 | 0.45* | 0.22-0.92 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Note. OR=Odds Ratio; 95% CI=Confidence Interval.

Interactions between diatheses and stressors

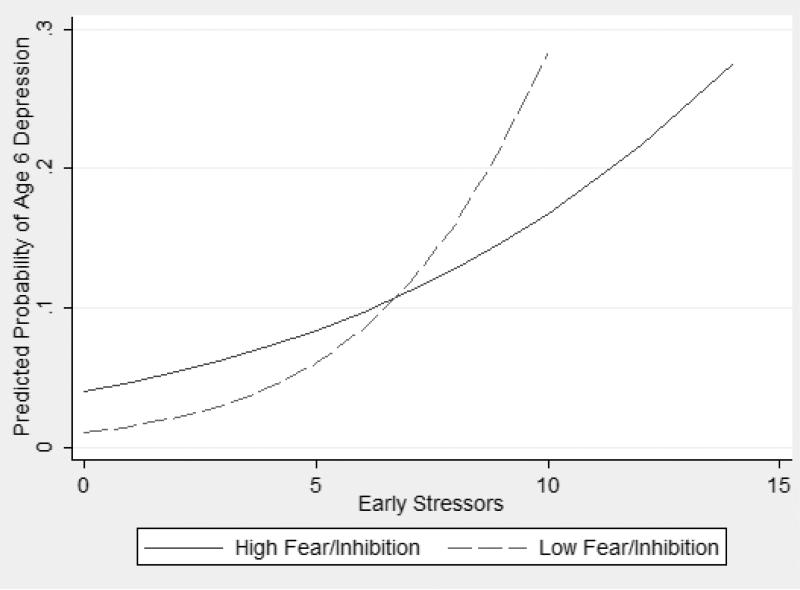

Interactions were examined between the potential diatheses of gender, parental psychopathology, and child temperament with early and recent stressors. There was a significant interaction between temperamental fear/inhibition and early stressors in predicting the onset of depression (Figure 1), OR=0.90, 95%CI=0.80-1.00, p=.05. Early stressors were significantly associated with the onset of depression when temperamental fear was low (B=.35, SE=.09, OR = 1.42, 95%CI=1.21-1.68, p<.001) whereas when temperamental fear was high, there was no association between early stressors and depression (B=.13, SE=.07, OR = 1.14, 95%CI=0.99-1.32, p=.07).

Figure 1.

Interaction between temperamental fear/inhibition and early stressors in predicting the onset of any depressive diagnosis at age 6.

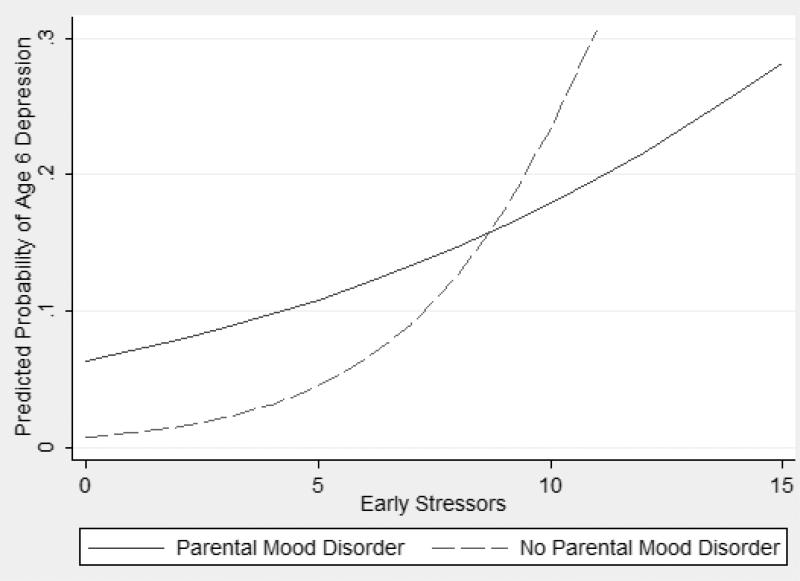

There was also a significant interaction between parental mood disorder and early stressors in predicting the onset of depression in children (Figure 2), OR=0.75, 95%CI=0.59-0.95, p<.05. Early stressors predicted the onset of depression in children when parents did not have a history of mood disorder (B=0.37, SE=.09, OR=1.45, 95%CI=1.22-1.72, p<.001), but did not have a significant effect when parents had a history of mood disorder (B=0.09, SE=.08, OR=1.09, 95%CI=0.93-1.28, p=.31).

Figure 2.

Interaction between parental history of mood disorder and early stressors in predicting the onset of any depressive diagnosis at age 6.

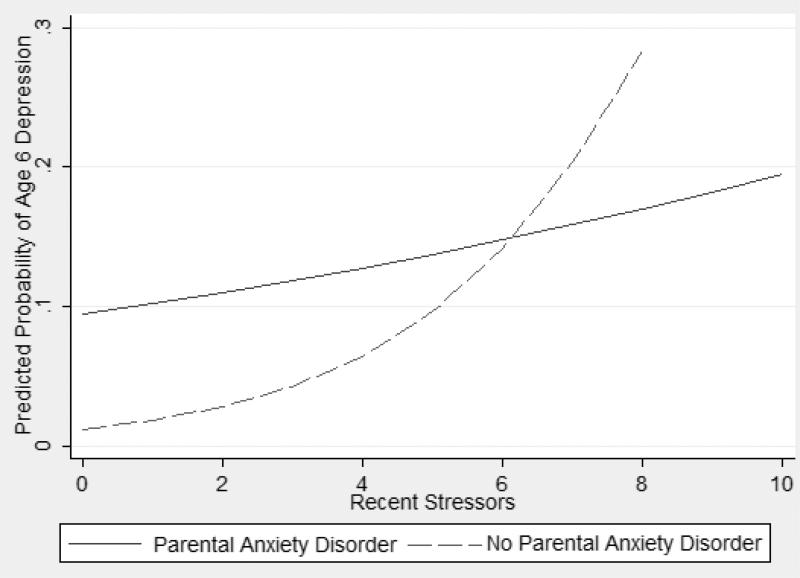

Finally, there was a significant interaction between parental anxiety disorder and recent stressors in predicting the onset of depression in children (Figure 3), OR=0.68, 95%CI=0.48-0.98, p<.05. Recent stressors predicted the onset of depression when parents did not have a history of anxiety disorder (B=0.44, SE=.15, OR=1.57, 95%CI=1.17-2.09, p<.01), but had no effect when parents had a history of an anxiety disorder (B=0.07, SE=.11, OR=1.07, 95%CI=0.86-1.34, p=.55).

Figure 3.

Interaction between parental history of anxiety disorder and recent stressors in predicting the onset of any depressive diagnosis at age 6.

Final logistic regression model

When the significant predictors above were entered into a multivariate logistic regression, temperamental low inhibitory control (OR=1.67, 95%CI=1.14-2.44,p<.01), parental anxiety disorders (OR=2.50, 95%CI=1.05-5.96,p<.05), and early stressors (OR=1.28,95%CI=1.12-1.47, p<.001), made significant unique contributions2. However, the main effects involving parental anxiety and early stressors were qualified by significant interactions: the effects of parental mood disorder by early stressors (OR=0.74,95%CI=0.57-0.95,p<.05) and parental anxiety disorder by recent stressors (OR=0.60,95%CI=0.39-0.91,p<.05) remained significant in the multivariate model. The interaction between temperamental fear/inhibition and early stressors was not significant in this model (OR=0.93,95%CI=0.84-1.03,p=.17).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively examine predictors of the onset of depressive disorders in early childhood. Using multiple methods, multiple informants, and a large community sample, we identified a number of predictors of the onset of depression at age 6, including child anxiety disorders and temperamental low inhibitory control, difficulties with peers, parental psychopathology, life stressors, and less parental education. In addition, interactions of temperamental fear/inhibition and parental mood and anxiety disorders with life stress predicted depression onset. We also examined the unique contributions of these predictors in a multivariate model. Child temperamental low inhibitory control, parental anxiety disorders, and early stressors uniquely predicted the onset of depression. In addition, interactions of parental mood and anxiety disorders with early and recent life stressors, respectively, contributed unique variance in the multivariate model. The inclusion of children with other diagnoses (i.e., anxiety and behavioral diagnoses) in the comparison group for the dependent variable (i.e., depressed at age 6 versus all other children) was a particularly conservative approach. A supplemental table (see online Table S1) is available with data on the predictors across three groups: depressed at age 6, children with other disorders at age 6, and healthy children (i.e., children who did not meet criteria for a diagnosis at age 3 or age 6).

Many of these variables have been previously reported to predict internalizing (and sometimes externalizing) symptoms in early childhood (Côté et al., 2009; Najman et al., 2005). Moreover, most predictors in the individual analyses and final multivariate model have also been reported to predict the onset of depression in older youth and adults (e.g., Eaton et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2013; Shanahan et al., 2011). As the factors influencing the onset of depression across the lifespan appear to be relatively similar, these data contribute to the evidence of continuity between depression in early childhood and older youth and adults (Luby et al., 2006; Shanahan et al., 2011).

We observed significant interactions of temperamental fear/inhibition and parental mood disorder with early stressors, as well as an interaction between parental anxiety disorder with recent life stressors, on the onset of depression in children. Early stressors in the family impacted the onset of depression only in the context of low temperamental fear/inhibition in the laboratory; in children who showed high temperamental fear/inhibition, exposure to early stressors did not appear to further increase risk. Similarly, among children of parents without a history of mood or anxiety disorder, levels of family stressors between the child's birth and age 3 and in the 12 months prior to the age 6 assessment, respectively, were associated with a greater risk of depression. In contrast, among children of parents with a history of mood or anxiety disorder, life stressors were not related to onset of depression. Notably, the pattern in each of these interactions differs from the classic diathesis-stress model, where the combination of the vulnerability factor and high stress is associated with increased risk. Instead, these data suggest that there are several different pathways to the onset of depression in young children: one pathway appears driven primarily by stress, and the other by a temperamental or familial diathesis for internalizing psychopathology.

The association of early anxiety with later depression is consistent with studies in older youth and adults (e.g., Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009; Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003). It is unclear whether this heterotypic continuity reflects causal effects, shared risk factors, or developmentally varying expressions of a single underlying process (Klein & Riso, 1993). This effect was one of the weaker of the significant effects in this study, and did not persist in the multivariate model.

Laboratory observations of low temperamental exuberance and high dysphoria at age 3 did not predict onset of depression at age 6; the relatively small number of children who developed depression may have limited our power to detect an association. However, temperamental fearfulness, a facet of negative affectivity, predicted depression among children with low levels of early stressors. In addition, low inhibitory control at age 3 predicted the onset of depression at age 6, a finding that persisted in the multivariate model. Low inhibitory control is a key component of effortful control (Rothbart et al., 2001), which has been shown to predict the onset of depression in adolescents (Laceulle et al., 2013), as well as poor outcomes on a wide range of psychosocial variables (Moffitt et al., 2011).

The finding that peer difficulties predicted the onset of depression is consistent with work suggesting that social withdrawal, peer rejection, and limited social skills contribute to the development of depression in youth (Rudolph, 2009). However, it is noteworthy that peer difficulties at such an early age predicted later depression. In addition, these findings indicate that poor peer functioning precedes depression onset and is not simply a correlate or consequence of depressive symptoms.

Our findings that parental histories of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders predict the onset of depression in young children are consistent with a previous study reporting familial aggregation of depression in preschoolers (Luby et al., 2006), and extend the literature indicating that familial liabilities for depression and anxiety disorders overlap (Merikangas, Dierker, & Szatmari, 1998; Middeldorp, Cath, Van Dyck, & Boomsma, 2005) to an even younger population. Our results are also consistent with evidence that parental substance use disorder is associated with depression in youth (Merikangas et al., 1998). Parental psychopathology may reflect greater genetic susceptibility, as well comprise an environmental stressor that contributes to child emotional and behavioral problems (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Importantly, the main effect for parental anxiety, and the interactions of parental mood and anxiety disorders with life stressors persisted in the multivariate models.

Psychosocial Environment

We found that early and recent life stressors were associated with the onset of depression, and both continued to contribute unique variance as main effects or moderators in the multivariate model. Our findings are consistent with past research finding that life events predict depressive symptoms in preschool-aged children (Luby et al., 2006) and the onset of depressive disorders in adolescents and adults (Monroe, Slavich, & Georgiades, 2009). Finally, less parental education predicted the onset of depression, possibly reflecting the link between social disadvantage and emotional and behavioral problems in children (Costello, Keeler, & Angold, 2001).

Strengths of this study include a large community sample, the use of multiple informants, including mothers, fathers, teachers, and experimenters; and multiple methods, including structured observations, structured interviews, and questionnaires. However, the study also had a number of limitations. First, the relatively small number of cases (n=33) of first onset depression limits the power to detect differences.

Second, we used modified criteria for MDD that were developed for preschoolers. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether young children who meet modified criteria for depression subsequently qualify for standard diagnoses of depression.

Third, the PAPA assesses symptoms occurring within the previous three months. Hence, we cannot be certain that children did not have episodes of disorders that remitted prior to the three months before the age 3 assessment, or between the age 3 assessment and the three months prior to the age 6 assessment. Therefore, it is conceivable that we missed some cases of mood, anxiety, and behavior disorders before age 3 and some depression diagnoses before age 6.

Fourth, we cannot date the onset of recent life events in relation to the onset of depression, although the longer window for the former (stressors in the previous 12 months) compared to the latter (depression in the previous three months) suggests that the stressors may have preceded onset. Given the young age of the sample and the fact that most stressors concerned parents and the family, rather than the individual child, it is unlikely that the child's depression caused the stressors.

Fifth, significant effects could reflect type 1 errors given that we conducted multiple tests without correcting for the number of comparisons. However, considering the small number of depressed cases, we were concerned that corrections would generate type 2 errors.

Finally, the sample was predominantly White and middle class; research with more diverse participants is necessary to generalize the results.

Conclusion

A range of variables assessed at age 3 predicted diagnoses of depression at age 6 in a large community sample of children. In particular, temperamental low inhibitory control, peer difficulties, parental anxiety disorders, and early stressors, and interactions of parental mood and anxiety disorders with stress had unique influences on the onset of depression. Similar predictors have been identified in older youth and adults. If replicated, future research should explore using these predictors to target children for prevention programs. Further, given that early depression may lead to multiple psychopathological outcomes later in development, continued follow-up of early childhood depression into adulthood is needed to trace its natural history and developmental course.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Although depression can be diagnosed in early childhood, little is known about factors that predict the onset of the disorder during this developmental period.

Using multiple methods and informants and a prospective longitudinal design, we found that child anxiety disorders, low inhibitory control, difficulties with peers, parental psychopathology, life stressors, and less parental education predicted the onset of depression in young children. In addition, temperamental fearfulness and parental mood and anxiety disorders interacted with life stressors to predict onset. Of these, low inhibitory control, parental anxiety disorders, and early stressors, and interactions of parental mood and anxiety disorders with life stressors uniquely predicted depression onset.

Predictors of the onset of depression in early childhood are relatively similar to those identified in older youth and adults.

Acknowledgments

G.C. has received funding from Glaxo Smith Kline, Bristol Myers Squibb/Otsuka, Pfizer, Schering-Plough/Merck, NIMH, and the Weyerheuser Foundation. This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants F31 MH084444 (Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award; Bufferd) and R01 MH069942 (Klein); and General Clinical Research Center grant M01 RR10710 (Stony Brook University, National Center for Research Resources).

Portions of this work were presented at the meetings of the Society for Research in Psychopathology, Boston, MA, September 22-25, 2011, and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, San Francisco, CA, October 23-28, 2012.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest statement: See acknowledgments.

A Mahalanobis distance analysis indicated three outliers (none with a depression diagnosis). However, Cook's distance indicated that the outliers did not influence the model. Nonetheless, when the outliers were dropped, the results were identical except that p values for significant effects for parental substance use disorder and the interaction between temperamental fear/inhibition and early stressors were reduced to p=.05 and p=.07, respectively.

Although teacher-rated poor peer functioning was excluded from this analysis due to the reduced sample size, when peer functioning was entered into the model it was significant (OR=1.68, 95%CI=1.19-2.37,p<.01), and all other significant effects remained.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information is provided along with the online version of this article.

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth edition text revision American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1977;43:1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;32:483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson GA, Rose SR, Klein DN. Preschool psychopathology: Continuity from age 3 to 6. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:1157–1164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: The coming of age of a discipline. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Keeler GP, Angold A. Poverty, race/ethnicity, and psychiatric disorder: A study of rural children. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1494–1498. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté SM, Boivin M, Liu X, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, Tremblay RE. Depression and anxiety symptoms: Onset, developmental course and risk factors during early childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1201–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Bufferd SJ, Carlson GA, Dyson MW, Olino TM, Klein DN. Preschoolers' observed temperament and psychiatric disorders assessed with a parent diagnostic interview. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:295–306. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE, Klein DN, Hayden EP, Buckley ME, Moerk KC. Temperamental emotionality in preschoolers and parental mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, Lee BH, Bienvenu J, Zandi P. Population-based study of first onset and chronicity in major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:513–520. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Weinfield N, Hiester M, Lawrence C, Pierce S, Chippendale K. Teaching tasks administration and scoring manual. University of Minnesota; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Holmgren R, Suh K. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Ascher BH, Angold A. The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment: Version 1.1. Center for Developmental Epidemiology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center; Durham, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders: Non-patient edition (SCID-I, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lemery KS, Longley S, Prescott A. Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery: Preschool version. 1995 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashani JH, Carlson GA. Major depressive disorder in a preschooler. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1985;24:490–494. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashani JH, Holcomb WR, Orvaschel H. Depression and depressive symptoms in preschool children from the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143:1138–1143. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DK, Glenn CR, Kosty DB, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM. Predictors of first lifetime onset of major depressive disorder in young adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:1–6. doi: 10.1037/a0029567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Riso LP. Psychiatric disorders: Problems of boundaries and comorbidity. In: Costello CG, editor. Basic issues in psychopathology. Guildford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 19–66. [Google Scholar]

- Laceulle O, Ormel H, Vollebergh W, van Aken M, Nederhof E. A Test of the Vulnerability model: Temperament and temperament change as predictors of future mental disorders: The TRAILS study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12141. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise E, Dodge KA. Teacher simulation of peer sociometric status. Vanderbilt University; Nashville, TN.: 1988. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Belden AC, Pautsch J, Si X, Spitznagel E. The clinical significance of preschool depression: impairment in functioning and clinical markers of the disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009a;112:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Belden A, Spitznagel E. Risk factors for preschool depression: The mediating role of early stressful life events. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1292–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Heffelfinger AK, Mrakotsky C, Hessler MJ, Brown KM, Hildebrand T. Preschool major depressive disorder: Preliminary validation for developmentally modified DSM-IV criteria. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:928–937. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, Brown K, Hessler M, Spitznagel E. Alterations in stress cortisol reactivity in depressed preschoolers relative to psychiatric and no-disorder comparison groups. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:1248–1255. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Si X, Belden AC, Tandon M, Spitznagel E. Preschool depression: Homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009b;66:897–905. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Dierker LC, Szatmari P. Psychopathology among offspring of parents with substance abuse and/or anxiety disorders: a high-risk study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:711–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp CM, Cath DC, Van Dyck R, Boomsma DI. The co-morbidity of anxiety and depression in the perspective of genetic epidemiology: a review of twin and family studies. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:611–624. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400412x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington HL, Caspi A. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010076108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Georgiades K. The social environment and depression: The importance of life stress. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. 2nd Guilford Press; New York: 2009. pp. 340–360. [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Hallam D, Bor W, O'Callaghan M, Williams GM, Shuttlewood G. Predictors of depression in very young children: A prospective study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph K. The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescents. Taylor and Francis Group; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 377–418. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, Copeland WE, Costello EJ, Angold A. Child-, adolescent- and young adult-onset depressions: Differential risk factors in development? Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:2265–2274. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.