ABSTRACT

A 4-year and 2-month-old male capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma on the buttocks after chronic recurrent dermatosis. The capybara was euthanized, examined by computed tomography and necropsied; the tumor was examined histologically. Computed tomography showed a dense soft tissue mass with indistinct borders at the buttocks. Histological examination of the tumor revealed islands of invasive squamous epithelial tumor cells with a severe desmoplastic reaction. Based on the pathological findings, the mass was diagnosed as a squamous cell carcinoma. This is the first study to report squamous cell carcinoma in a capybara.

Keywords: capybara, computed tomography, Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris, squamous cell carcinoma

The capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), the world’s largest rodent, is a member of the order Rodentia, family Caviidae, and inhabits the eastern Amazon basin in South America [14]. Although many capybaras are maintained in zoos, aquariums and breeding farms worldwide, few studies have investigated capybaras diseases [6, 12]. Moreover, only 1 study has reported a spontaneous tumor in a capybara [19], and previous literature had not listed reports of tumors in this species [5, 13]. Guinea pigs, another member of the family Caviidae, are closely related to capybaras [14] and are frequently used experimentally. Their diseases are the most examined in the family Caviidae; however, spontaneous tumors are reportedly rare in guinea pigs [8, 9]. Therefore, spontaneous tumors in the family Caviidae have not been studied in detail.

Virtopsy (a virtual autopsy) [2] employs computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for forensic investigation; The technique is also used for conventional autopsy or to guide conventional necropsy [11, 15, 20]. In general, necropsy requires opening the body for examination. However, with CT or MRI virtopsy, there is no need to open the body. In addition, comparing postmortem CT or MRI data with necropsy and histopathological findings may be useful to investigate biological traits including anatomical structures [15]. This may be advantageous in autopsies requiring non-invasiveness, such as those of humans and endangered wildlife. Several studies have examined virtopsy in human medicine [2], but few studies have reported the use of virtopsy in veterinary medicine; virtopsy used to identify a neoplasm in a zoo animal has not been reported [11, 15, 20]. Therefore, the utility of virtopsy in veterinary medicine must be evaluated.

Squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor commonly encountered in numerous species, such as dogs, cats, horses and cattle [7]. In general, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma locally infiltrates and infrequently metastasizes to the lymph node [1, 7, 10]. In the mouse, a member of the order Rodentia, spontaneous cutaneous squamous cell tumors are rare [10]. Murine cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma can arise from a pre-existing keratoacanthoma or ulcer [1, 10]. Murine squamous cell carcinoma is histologically subdivided into well-differentiated, poorly-differentiated and anaplastic types. Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by polymorphic squamous tumor cells with intercellular bridges, distinct cell boundaries, inflammatory changes and desmoplastic reaction. In poorly-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, individual keratinized squamous tumor cells are observed. Anaplastic squamous cell carcinoma is difficult to be distinguished from mesenchymal tumor due to its spindle shape [1, 10]. In humans, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is histologically subdivided into numerous subtypes [3, 17].

This report describes a rare spontaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a captive capybara along with the clinical course, CT findings and pathological findings.

The 4-year and 2-month-old male capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) was born in an aquarium in Nagasaki and maintained in an aquarium in Gifu, Japan. Approximately 1 year before the gluteal mass was discovered, the capybara was diagnosed with dermatosis; the entire body was covered by abnormal keratinization characterized by adherent, dry and rough excess keratinous hyperplasia, as well as crusting and scaling. Alopecia secondary to the keratinous hyperplasia was present on the entire body, especially the limbs. Bacterial dermatitis was suspected; therefore, cefaclor [10.8 mg/kg, per os (PO), ter in die (t.i.d.)] was administered empirically. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion resolved. However, 1 month after remission, a similar lesion recurred. Ofloxiacin (4.3 mg/kg, PO, t.i.d.) was then administered to treat a resistant bacterial infection. The lesion resolved following antibiotic therapy, but once again, the lesion recurred 1 month after remission. This cycle repeated 4 times over 10 months of antibiotic therapy including sultamicillin [16.2 mg/kg, PO, bis in die (b.i.d.)], cefpodoxime proxetil (4.3 mg/kg, PO, b.i.d.) and doxycycline hydrochloride (4.3 mg/kg, PO, semel in die). With each recurrence, a different antibiotic was prescribed.

One and one half months after the last remission, a 3 cm wide mass was found in haired regions of the left buttock near the anus. The mass initially appeared hemorrhagic and encrusted. Surrounding areas including subepidermal tissue relatively maintain the same width. Recurrence of the abnormal keratinization was a concern, and therefore, gentamicin sulfate was applied topically onto the lesion twice daily. However, the mass continued to rise and infiltrate the surrounding tissue over approximately 6 months, and it appeared alopecic and ulcerated. The growth was mainly exophytic, gradually endophytic, cauliflower-shaped and fibrous granulomatous.

A surgical biopsy sample was obtained, fixed in 10% formalin and evaluated by the Laboratory of Veterinary Pathology at Gifu University. The tissue was then embedded in paraffin, cut into 3 to 4 µm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E); it was ultimately diagnosed as a squamous cell carcinoma. Since the tumor had conglutinated the rectum, the prognosis was poor. In addition, the capybara exhibited constipation and was consequently euthanized.

A postmortem virtopsy comprising a whole-body cavity CT (Asteion Super 4, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) was performed at a 2.0 mm slice thickness for the thorax and 1.0 mm for the rest of the body. A complete necropsy was then performed, and the organs and tissues were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The tissue samples were sectioned and stained with H&E as described above. An immunohistochemical evaluation was performed, beginning by immersing the deparaffinized sections in a Target Retrieval Solution (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, 1:10) and heating them for 15 min at 121°C in an autoclave. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubation with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 20 min at room temperature. To avoid the nonspecific antibody binding, each section was treated with Protein Block Serum-Free (Dako) for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were incubated with the primary antibody Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (monoclonal mouse; Dako, 1:50) overnight at 4°C and then counterstained with hematoxylin.

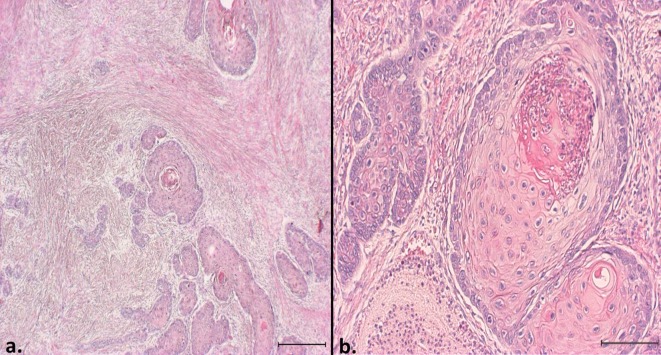

The CT showed an irregular mass with rough outside at the left side of the buttock near the rectum with a soft tissue density (63.0 Hounsfield Unit). The mass border was difficult to delineate and was highly invasive into the surrounding areas (Fig. 1). Therefore, endophytic evaluation was difficult on CT. Calcified foci were observed surrounding the mass, but metastasis and osteolysis were not detected.

Fig. 1.

Coronal section CT of a gluteal mass (circle) in a capybara, which was highly invasive, of soft tissue density, and had an indistinct border, the femur (arrows) and calcification-like lesions (arrowheads).

On necropsy, a large mass measuring approximately 20 × 10 × 9.5 cm in diameter was found at the buttocks (Fig. 2). The surface was ulcerated and hemorrhagic. Variously- sized multiple masses were found between the ventral anus and the inguinal region. The lesions mainly exist in the left side of the rectum and anus. The mass infiltrated near the rectum and into the surrounding muscle. A desmoplastic reaction was observed macroscopically on the cut surface of the mass and interrupted the surrounding muscle. The inguinal lymph nodes were markedly enlarged, and discolored multifocal yellowish mottles were found on the cut surface. There was a large amount of feces in the rectum.

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic photographs of a capybara diagnosed with a squamous cell carcinoma on the buttocks. A large mass is present on the buttocks and can be correlated to the mass identified on CT.

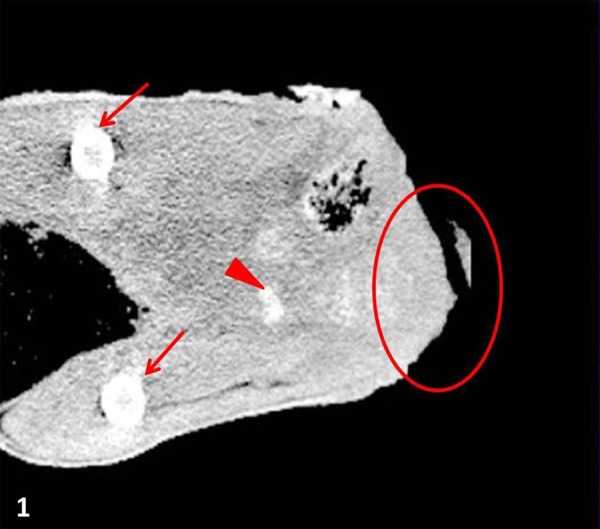

On histological examination, the cutaneous mass mostly comprised islands or cords of infiltrating squamous epithelial tumor cell layers (Fig. 3). The tumor cells possessed large nuclei with marked atypia, 1 or 2 prominent nucleoli, a moderate-to-abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell boundaries. There was an average of 3 to 4 mitotic figures per 10 fields (400×). The cells showed various degrees of keratinization with keratin pearls in the cell islands. Inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils and lymphocytes, frequently infiltrated the keratin pearls. The tumor cells were highly invasive and were accompanied by a severe desmoplastic reaction of surrounding reactive fibroblasts (Fig. 3). The neoplastic tissue infiltrated the muscle layer, which had a particularly severe desmoplastic reaction. Metastasis was present and replaced nearly the entire inguinal lymph node. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cytoplasm was intensely positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, confirming the cell origin as being epithelial.

Fig. 3.

Histopathological features of a squamous cell carcinoma in a capybara. HE. a) The lesion comprised islands of invasive squamous epithelial tumor cells with a severe desmoplastic reaction. Bar=500 µm. b) The tumor cells showed various degrees of keratinization with keratin pearls. Inflammatory cells frequently infiltrated many of the keratin pearls. Bar=200 µm.

Very few studies have investigated the diseases of capybara [6, 19]. Scabies, ticks in the genus Amlyomma, helminthes, coccidia, trypanosomiasis, brucellosis and sanitary management in breeding farms are mainly reported [6], while studies of noninfectious diseases, particularly neoplasia, are scarce [6, 19]. This is the first known report of squamous cell carcinoma in a capybara. The only similar previous report described a fibrosarcoma in an 8-year-old capybara [19], far older than the capybara presently reported. Capybaras live for 8 to 10 years [4], and in guinea pigs, which are closely related to capybaras, tumors are more prevalent in older animals [9]. Therefore, an external factor other than age may have contributed to tumor development in the juvenile of the present case. There are several factors known to spur squamous cell carcinoma development. Ultraviolet light, keratoacanthoma, viruses, hyperplasia and chronic inflammation can all progress or induce cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in mice [1, 10]. In the present case, the tumor arose mostly above the skin surface initially, and therefore, it may not have arisen from a pre-existing keratoacanthoma [1]. Notably, the patient experienced intermittent chronic episodes of abnormal keratinization remission and recurrence that predated the present tumor; this abnormal keratinization may have been related to neoplastic development. Bacterial dermatitis was initially suspected as the underlying etiology; therefore, antibiotics were administered, and the lesion temporarily responded. However, the actual cause of the dermal lesions was not diagnosed; therefore, clear causality cannot be established. Yet, the recurrent abnormal keratinization may have been an inciting factor in the tumor, based on the similar pattern of keratinization in both the dermal lesions and the mass itself.

In the present case, the tumor was diagnosed as a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma based on murine histological classification [1, 10] and had several remarkable characteristics. The desmoplastic reaction was severe, and tumor cells surrounded by reactive fibroblasts had infiltrated the muscle. The desmoplastic reaction of squamous cell carcinoma accompanies tumor infiltration. Human desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma, which is a stroma-rich squamous cell carcinoma, metastasizes and locally infiltrates more often than does the common squamous cell carcinoma [3, 17]. Similarly, in the present case, metastasis was observed at the regional lymph nodes. Based on these pathological features, the present case may represent a characteristic histological squamous cell carcinoma subtype similar to human desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma. Unlike human lesions, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in animals is not differentiated into complex subtypes [1, 7, 10]. Additional investigation may reveal that highly-aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in capybara is accompanied by a more severe desmoplastic reaction.

As reported previously [11], CT-based virtopsy was a useful guide for necropsy in the present case. The postmortem CT provided valuable information in the present case by revealing the absence of osteolysis. In addition, the histological and CT findings were correlated to a degree. A severe desmoplastic reaction found histologically may be correlated to the soft tissue density on CT [16]. However, metastasis was not detected on CT; this may be due to the unavailability of a contrast medium, which provides information about metastasis and tumor characteristics [18]. A contrast medium could not be used, because the CT was performed after euthanasia. More investigations about the filming condition are needed to use CT scans as virtopsy.

This report presents the clinical course and pathological findings of a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a capybara. Postmortem CT-based virtopsy revealed that the mass was invasive and of soft tissue density with no metastasis detected. However, on histological analysis, metastasis was found in the regional lymph nodes. These differences between virtopsy and histological analysis may resolve by little contrivance. Histologically, the mass showed features similar to a murine well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Additional reports could further characterize tumors in capybara and the family Caviidae.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogovski P.1994. Skin. pp. 1–23. In: Pathology of Tumours in Laboratory Animals. vol. II. Tumours of the Mouse, 2nd ed. (Turusov, V. S. and Mohr, U. eds.), International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolliger S. A., Thali M. J., Ross S., Buck U., Naether S., Vock P.2008. Virtual autopsy using imaging: bridge radiologic and forensic sciences. A review of the virtopsy and similar projects. Eur. Radiol. 18: 273–282. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0737-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breuninger H., Schaumbrug-Lever G., Holzschuh J., Horny H. P.1997. Desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma of skin and vermillion surface. Cancer 79: 915–919. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton M., Burton R.2002. Capybara. pp. 382–384. In: International Wildlife Encyclopedia, 3rd ed. (Cooke, T. ed.), Marshall Cavendish Corporation, Tarrytown. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark J. D., Loew F. M., Olfert E. D.1978. Rodents. pp. 457–477. In: Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine (Fowler, M. E. ed.), WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cueto G. R.2013. Diseases of Capybara. pp. 169–184. In: Capybara: Biology, Use and Conservation of an Exceptional Neotropical Species (Moreira, J. R., Ferraz, K. M. P. M. B., Herrera, E. A. and Macdonald, D. W. eds.), Springer Science + Business Media, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldschmidt M. H., Hendrick M.J.2002. Tumors of the skin and soft tissues. pp. 45–117. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, 4th ed. (Meuten, D.J. ed.), Iowa State Press, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harkness J. E., Turner P. V., Woude S. V., Wheler C. L.2010. Specific diseases and conditions. pp. 249–396. In: Harkness and Wagner’s Biology and Medicine of Rabbits and Rodents, 5th ed., Blackwell Publishing, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jelínek F.2003. Spontaneous tumours in guinea pigs. Acta Vet. (Brno) 72: 221–228. doi: 10.2754/avb200372020221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John C. P., Heider K.1999. Skin and subcutis. pp. 513–613. In: Pathology of the mouse, 1st ed. (Maronpot, R. R. ed.), Cache River Press, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee K.J., Sakaki M., Miyauchi A., Kishimoto M., Shimizu J., Iwasaki T., Miyake Y., Yamada K.2011. Virtopsy in a red kangaroo with oral osteomyelitis. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 42: 128–130. doi: 10.1638/2010-0015.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meireles M. V., Soares R. M., Bonello F., Gennari S. M.2007. Natural infection with zoonotic subtype of Cryptosporidium parvum in capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) from Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 147: 166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller R. E., Fowler M. E.2012. Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine Current Therapy, vol. 7, Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mones A., Ojasti J.1986. Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris. Mamm. Species 264: 1–7. doi: 10.2307/3503784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okeson D. M., Coke R. L., Kochunow P., Davis M. D.2008. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in a red kangaroo (Macropus rufus) with otitis. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 39: 667–670. doi: 10.1638/2008-0020.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantongrag-Brown L., Buetow P. C., Carr N. J., Lichtenstein J. E., Buck J. L.1995. Calcification and fibrosis in mesenteric carcinoid tumor: CT findings and pathologic correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 164: 387–391. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.2.7839976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petter G., Haustein U. F.2000. Histologic subtyping and malignancy assessment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol. Surg. 26: 521–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi F., Patsikas M., Wisner E. R.2011. Abdominal lymph nodes and lymphatic collecting system. pp. 371–379 In: Veterinary Computed Tomography, 1st ed. (Schwarz, T. and Saunders, J. eds.), Wiley-Blackwell, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoffregen D. A., Prowten A. W., Steinberg H., Anderson W. I.1993. A fibrosarcoma in the skeletal muscle of a capybara. J. Wildl. Dis. 29: 345–348. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-29.2.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thali M. J., Kneubuehi B. P., Bolliger S. A., Christe A., Koenigsdorfer U., Ozdoba C., Spielvogel E., Dirnhofer R.2007. Forensic veterinary radiology: ballistic-radiological 3D computer tomographic reconstruction of an illegal lynx shooting in Switzerland. Forensic Sci. Int. 171: 63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]