Interleukin 1 (IL-1) is a pleiotropic cytokine that regulates immune and inflammatory responses by inducing the expression of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. IL-1 exerts its pro-inflammatory effects primarily by activating nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs).1 After binding to its receptor complex, IL-1R, IL-1 recruits the cytosolic adaptor MyD88 via the Toll–IL-1R domain of IL-1R.2 MyD88 subsequently recruits the IRAK4 and IRAK1 kinases, resulting in the hyperphosphorylation of IRAK1 by IRAK4.3 This leads to binding and activation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6, which contains a ubiquitination-mediating RING ligase domain.4 TRAF6 conjugates K63-linked polyubiquitin chains both to itself and to IRAK1, promoting recruitment of the TAK1 kinase, the TAK1-binding proteins TAB2 and TAB3, and the linear ubiquitin assembly complex. Linear ubiquitin assembly complex subsequently generates linear polyubiquitin chains that recruit the kinase IKK (‘inhibitor of NF-κB kinase') complex.5 Subsequently, TRAF6 mediates the attachment to IKKγ (a regulatory subunit of the IKK complex) and TAK1 of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, which leads to the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs.6,7,8

IRF1, IRF3, IRF5 and IRF7 mediate critical Toll-like receptor- and cell-specific regulation of type I interferons.9,10 While IL-1 is known to induce expression of IRF1, the roles of IRF1 in IL-1-mediated immune and inflammatory responses, and the mechanisms by which it is activated, remain unknown.

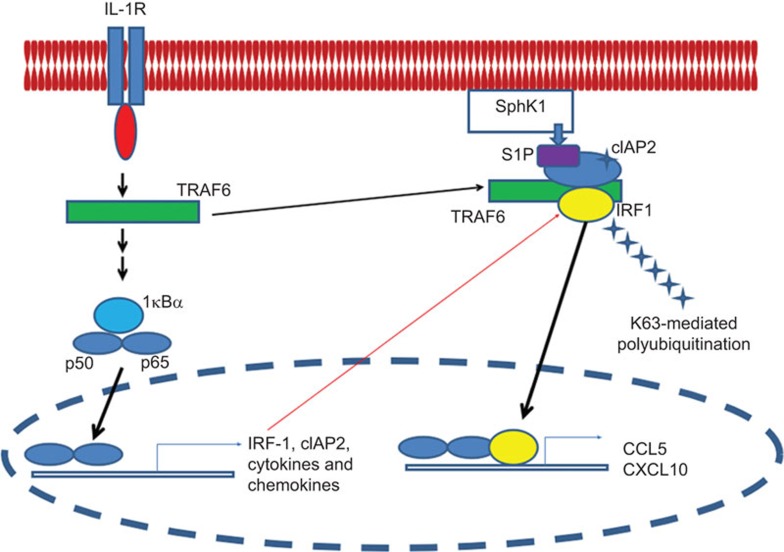

In a recent issue of Nature Immunology, Harikumar et al.11 demonstrate that IRF1 plays a key role in IL-1-mediated regulation of the expression of the chemokine genes CXCL10 and CCL5, which are ‘delayed' IL-1-responsive genes important for sterile inflammation. This cascade requires K63-linked polyubiquitination of IRF1, which is synthesized in response to IL-1. Moreover, the authors showed that the apoptosis inhibitor cIAP2, and the bioactive sphingolipid mediator S1P, are essential for K63-linked polyubiquitination of IRF1. Collectively, these findings identified a new signaling pathway of IL-1 that complements the well-documented NF-κB activation pathways, and which is important for sterile inflammation.

Firstly, the authors demonstrated that in both human and mouse astrocytes, IL-1 induced the expression of CXCL10, CCL5 and IRF1 mRNA, as well as levels of IRF1 protein, which subsequently accumulated in the nuclei of these cells. They proceeded to demonstrate that IL-1 induction of CXCL10 and CCL5 mRNA was almost completely eliminated in IRF1 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), indicating a pivotal role for IRF1 in IL-1 induction of these chemokine genes. Consonant with this, in vivo induction of these chemokines by intraperitoneal administration of IL-1 was abrogated in Irf1−/− mice. Interestingly, the same study showed that effective recruitment of mononuclear cells to sites of sterile inflammation required IRF1-dependent expression of CXCL10 and CCL5.

The authors next asked whether activation of IRF1 by IL-1 involved K63-linked polyubiquitination, which had been previously shown to be required for activation of IRF3, IRF5 and IRF7. Transfection experiments using IRF1 combined with wild-type, K63- or K48-linked ubiquitin, indicated that IL-1 stimulation specifically enhanced K63- but not K48-linked polyubiquitination of IRF1, which targets IRF1 for degradation. The authors then identified the E3 ubiquitin ligase that mediated IL-1-induced K63-linked polyubiquitination of IRF1 as cIAP2, an IL-1 activated E3 ligase whose expression is induced by NF-κB. The authors showed that cIAP2 efficiently polyubiquitinated IRF1 in the presence of S1P, a cofactor for the E3 ligase activity of TRAF2, which mediates K63-linked polyubiquitination of RIP1, a signaling mediator in the TNF-initiated pathway.12 The authors found that in contrast, co-incubation of IRF1 with ubiquitin and the ubiquitin-activating enzymes E1 and E2, together with TRAF2, TRAF6 or cIAP1, failed to generate polyubiquitinated IRF1 in vitro. In addition, S1P, but not structurally related phospholipids, stimulated both total and K63-linked polyubiquitination of IRF1, but not K48-linked polyubiquitination of IRF1, indicating that its stimulatory effect was specific.

To identify the sites of polyubiquitination, the authors next compared induction of an IFN-β reporter gene by a panel of IRF1 K→R mutants and identified K75, K78, K95 and K101 as candidate polyubiquitination residues that were important for IRF1 function. Moreover, IL-1 enhanced ubiquitination of cIAP2 indicated that it activated cIAP2. Based on these results, the authors concluded that K63-linked polyubiquitination was required for activation of IRF1, and that this was mediated by cIAP2 in the presence of S1P.

The authors proceeded to investigate whether cIAP2 and S1P were linked to IL-1-induced signaling, or to activation of IRFs by IL-1R or Toll-like receptors. They found that cIAP2 and SphK1, a sphingosine kinase whose phosphorylation results in local production of S1P, were recruited to IL-1-induced signaling complexes. Moreover, they showed that cIAP2 was specifically recruited by IL-1-activated TRAF6, suggesting that IL-1-induced activation of TRAF6 leads to the recruitment of both cIAP2 and SphK1. The authors further demonstrated that IL-1 stimulated the interaction of cIAP2 with IRF1, suggesting that IRF1 was also recruited to that complex. In concert, these results indicated that IL-1 signaling resulted in recruitment of both SphK1 and cIAP2, which may be important for IRF1 activation. Further studies showed that both SphK1 and cIAP2 were required for IL-1 induction of chemokine-encoding genes. Adding weight to this was the observation that SKI-1, a highly specific small-molecule inhibitor of SphK1,13 abolished IL-1-induction of CCL5 and CXCL10 at the mRNA and protein levels. Induction of CXCL10 and CCL5 by IL-1, but not IL-6, was abrogated in Sphk1−/− mice, and induction of these genes by IL-1 was similarly compromised in cIAP2-deficient (Birc3−/−) MEFs. By showing that both basal and IL-1-induced polyubiquitination of IRF1 was blocked by SMAC, a mimetic of the caspase activator Smac that effects degradation of both cIAP1 and cIAP2,14 the authors demonstrated that cIAP2 was required for IL-1-induced polyubiquitination of IRF1. In addition, in showing that IL-1-induced polyubiquitination of IRF1 in wild-type MEFs was lost in Birc3−/− MEFs, they confirmed the role of cIAP2 in polyubiquitination of IRF1. Collectively, these results suggested that polyubiquitination of IRF1 was mediated by cIAP2 and resulted in the activation of IRF1 and IRF1-dependent gene expression.

The authors proceeded to demonstrate that S1P bound cIAP2 and promoted K63-mediated polyubiquitination of IRF1. Next, they used immunoprecipitation analysis in tandem with liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry to demonstrate that S1P bound to cIAP2 but not to IRF1, an observation confirmed by the binding of 32P-labeled S1P to recombinant cIAP2. Molecular modeling of the binding of S1P to cIAP2 suggested that S1P binds to a groove in the RING domain of cIAP2. These results were supported by the observations that, compared with wild-type cIAP2, the cIAP2 RING-domain mutants T594A, I595A and K596A exhibited reduced binding to S1P and had reduced in vitro E3 ligase activity toward IRF1.

Taken together, the results of this study identify a previously unrecognized IL-1/IL-1R signaling cascade that mediates activation of newly synthesized IRF1 and subsequent induction of IRF1-dependent genes in sterile inflammation. Moreover, the study provides evidence that activation of IRF1 requires its K63-linked polyubiquitination, which is mediated by cIAP2, and is dependent upon the production of S1P by SphK1 (Figure 1). The novel pathway identified by this study differs from Toll-like receptor, which activate IRF3 and/or IRF7 and recruit inflammatory cells to sites of infection. Given the important role played by IRF1 in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases,15 this newly defined cascade may serve as a novel therapeutic target in such disorders.

Figure 1.

An IL-1-induced signaling pathway is mediated by K63-linked polyubiquitination of IRF1. Upon stimulation by IL-1, IL-1R recruits MyD88 adapter, IRAK4, IRAK1, MEKK3 and TRAF6. This results in recruitment of a series of signaling molecules and consequent activation of MAPKs, followed by translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus where it induces the expression of genes encoding IRF1, cIAP2 and a variety of cytokines. Newly synthesized IRF1 undergoes K63 polyubiquitination with TRAF6-associated cIAP2. This K63-linked polyubiquitination is regulated by S1P, which is generated by SphK1 upon activation of IL-1. Subsequently, IRF1 translocates to the nucleus and activates expression of IRF1-dependent genes, including those encoding chemokines such as CCL5 and CXCL10. MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB.

References

- Arend WP. The balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra in disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:323–340. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens S, Beyaert R. A universal role for MyD88 in TLR/IL-1R-mediated signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:474–482. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Staschke K, Bulek K, Yao J, Peters K, Oh KH, et al. A critical role for IRAK4 kinase activity in Toll-like receptor-mediated innate immunity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1025–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J, Gohda J, Akiyama T. Characteristics and biological functions of TRAF6. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;597:72–79. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-70630-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerich CH, Ordureau A, Strickson S, Arthur JS, Pedrioli PG, Komander D, et al. Activation of the canonical IKK complex by K63/M1-linked hybrid ubiquitin chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:15247–15252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314715110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–765. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, et al. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell. 2000;103:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conze DB, Wu CJ, Thomas JA, Landstrom A, Ashwell JD. Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of IRAK-1 is required for interleukin-1 receptor- and Toll-like receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3538–3547. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02098-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K, Sasaki I, Sugiyama T, Yano T, Yamazaki C, Yasui T, et al. Critical role of IkappaB Kinase alpha in TLR7/9-induced type I IFN production by conventional dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3341–3345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkhi MY, Fitzgerald KA, Pitha PM. Functional regulation of MyD88-activated interferon regulatory factor 5 by K63-linked polyubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:7296–7308. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00662-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikumar KB, Yester JW, Surace MJ, Oyeniran C, Price MM, Huang WC, et al. K63-linked polyubiquitination of transcription factor IRF1 is essential for IL-1-induced production of chemokines CXCL10 and CCL5. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:231–238. doi: 10.1038/ni.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez SE, Harikumar KB, Hait NC, Allegood J, Strub GM, Kim EY, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a missing cofactor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF2. Nature. 2010;465:1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/nature09128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paugh SW, Paugh BS, Rahmani M, Kapitonov D, Almenara JA, Kordula T, et al. A selective sphingosine kinase 1 inhibitor integrates multiple molecular therapeutic targets in human leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:1382–1391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen SL, Wang L, Yalcin-Chin A, Li L, Peyton M, Minna J, et al. Autocrine TNFalpha signaling renders human cancer cells susceptible to Smac-mimetic-induced apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada Y, Ho A, Matsuyama T, Mak TW. Reduced incidence and severity of antigen-induced autoimmune diseases in mice lacking interferon regulatory factor-1. J Exp Med. 1997;185:231–238. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]