Abstract

Embryos express paternal antigens that are foreign to the mother, but the mother provides a special immune milieu at the fetal–maternal interface to permit rather than reject the embryo growth in the uterus until parturition by establishing precise crosstalk between the mother and the fetus. There are unanswered questions in the maintenance of pregnancy, including the poorly understood phenomenon of maternal tolerance to the allogeneic conceptus, and the remarkable biological roles of placental trophoblasts that invade the uterine wall. Chemokines are multifunctional molecules initially described as having a role in leukocyte trafficking and later found to participate in developmental processes such as differentiation and directed migration. It is increasingly evident that the gestational uterine microenvironment is characterized, at least in part, by the differential expression and secretion of chemokines that induce selective trafficking of leukocyte subsets to the maternal–fetal interface and regulate multiple events that are closely associated with normal pregnancy. Here, we review the expression and function of chemokines and their receptors at the maternal–fetal interface, with a special focus on chemokine as a key component in trophoblast invasiveness and placental angiogenesis, recruitment and instruction of immune cells so as to form a fetus-supporting milieu during pregnancy. The chemokine network is also involved in pregnancy complications.

Keywords: chemokine, decidua, pregnancy, pregnant complications, trophoblast

Introduction

The intimate association between maternal and placental tissues elicits an interesting immunological paradox. Placental tissue contains paternal antigens, but under normal circumstances, the allogeneic fetus and placenta are not attacked by the maternal immune system. Interestingly, this tolerance to fetal antigens occurs in the presence of a large number of maternal leukocytes, almost all of which are members of the innate immune system. There is a delicate crosstalk and collaboration between fetus-derived trophoblast cells and maternally-derived cells during normal pregnancy to establish a unique maternal–fetal immune milieu that contributes to embryo survival and development in the uterus until parturition. Dysfunction in the interactions of trophoblasts and maternally-derived cells and dysregulation of maternal–fetal immune tolerance are highly linked to some pregnancy failures, such as miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction and so on. The chemokine/chemokine receptor interactions play roles in almost all facets of maternal–fetal crosstalk. In this review, we highlight the contribution of chemokines and their receptors at the maternal–fetal interface to the maintenance of normal pregnancy, especially to maternal–fetal tolerance and to placentation. Since normal pregnancy is a model of natural immune tolerance, pregnancy research may assist in the broader understanding of tumor immunology and of transplantation immunology.

The chemokine family

The chemokines constitute a superfamily of small chemotactic cytokines. More than 50 chemokines and at least 20 chemokine receptors have been identified.1,2 Chemokines exert their effects through G protein-coupled receptors.2 Based on their structural motif, including the number and position of two conserved cysteine residues, chemokines are classified into subfamilies: the CXC, CC, CX3C and C groups or the α, β, γ and δ subfamilies. Chemokine receptors are also divided into four corresponding groups.3 One or three amino acids separate the first and second cysteines in the CXC and CX3C chemokines, respectively, the two cysteines are adjoining in the CC subfamily, and the C subfamily lacks the first and pairing third conserved cystein residues. The fifth receptor subfamily, CX, reported only in zebrafish lacks the two N-terminal residues, but retains the third and fourth residues.4 The CXC family can be further subdivided by the presence or absence of a conserved ‘Glu-Leu-Arg' (ELR) subsequence at the NH2 terminus. The ELR+ family is involved in angiogenesis and the ELR− family is involved in angiostatic activity.5

The primary functions of chemokines are the directional stimulation of immune-cell adhesion and migration into the infected or inflamed tissue to initiate effective immune responses. However, chemokine functions are not restricted to chemotaxis but serve many other immune purposes such as dendritic cell (DC) maturation,6 B-cell antibody class switching,7 and T-cell activation and differentiation.8 Chemokines are also potent mediators of neoangiogenesis and tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis,9,10 and play a pivotal role in embryogenesis and organ transplantation.11

More recently, chemokine receptors with structural features that are inconsistent with a signalling function have been described. When ligated, these ‘silent' (non-signalling) chemokine receptors do not elicit migration or conventional signalling responses, but regulate inflammatory and immune reactions in different ways, such as acting as decoys or scavengers. The availability of chemokines is regulated by three non-signalling decoy receptors: chemokine decoy receptor (D6), Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) and chemocentryx decoy receptor (CCX CKR). The expression of decoy receptors is mainly restricted in placental cells and endothelial cells of lymphatic afferent vessels in skin, gut and lung.12,13,14

The chemokine network at the maternal–fetal interface

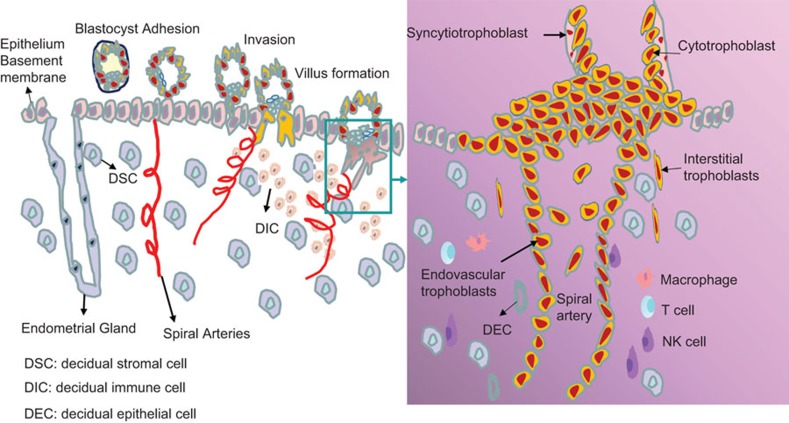

After the blastocyst hatches from the zona pellucida and adheres to the endometrium during the onset of the implantation window, trophoblast cells proliferate and differentiate into cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast, resulting in the formation of anchoring chorionic villous. Highly invasive cytotrophoblasts invade into the luminal epithelium and subsequently the myometrial stroma as interstitial trophoblast, which then migrate and infiltrate the endothelium, and remodel the maternal spiral arteries. At the maternal side is located by decidual cells including around 70% of decidual stromal cells (DSCs) and the infiltrated dedual immune cells (DICs) at the site of implantation. The DICs are comprised of natural killer (NK) cells (70%), macrophages (15%), T (15%) cells and very little of other types of immune cells. Thus, fetal trophoblasts, maternal DSCs and DICs are the main components at the maternal–fetal interface. Figure 1 describes the dynamic formation process of maternal–fetal interface in early human pregnancy. Functional chemokines and their receptors are widely expressed at the maternal–fetal interface, and play a pivotal role in this intercellular communication. Through Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) assay, our group systematically analyzed the expression of 18 chemokine receptors at the maternal–fetal interface disclosing general and differential expression patterns. In primary trophoblast, we found high levels of CXCR4 and CXCR6 mRNA, moderate expression of CCR1, CCR3, CCR5, CCR8, CCR9, CXCR1, CXCR4, CXCR6, XCR1 and CX3CR1 and no expression of CCR2, CCR6, CCR7, CCR10 and CXCR5.15 In contrast, in human DSCs, CCR2, CCR5 and CCRl0 are highly expressed while CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, CCR6, CCR8-9, CXCRl, CXCR4, CXCR6, XCR1 and CX3CRl are moderately expressed. CCL2 and CCLl3, the ligands of CCR2, and CCL28, the ligand of CCRl0, are also expressed highly in decidua and DSCs.16 Further studies have shown that primary trophoblasts secrete high levels of CXCL12 and CXCL16, while DSCs produce abundant CCL2.15,16,17 In addition, trophoblasts secrete CCL24, whereas DSCs express its receptor, CCR3.18 These data suggest that a complicated chemokine/chemokine receptor network is present at maternal–fetal interface.

Figure 1.

The dynamic process of formation of the maternal–fetal interface in early pregnancy. The embryo arrives at the uterus about 6–7 days after fertilization. At first, the free floating blastocyst is surrounded by its zona pellucida in utero, then the blastocyst hatches from the zona pellucida and adheres to the endometrium during the implantation window. Adhesion induces trophoblast cells to differentiate into inner cytotrophoblast and outer syncytiotrophoblast, resulting in formation of anchoring chorionic villous. Then the syncytiotrophoblast layor is penetrated by proliferative trophoblast cell columns. The columns give rise to highly invasive extravillous trophoblasts that invade into the decidua and subsequently the myometrial stroma as interstitial trophoblast. Interstitial trophoblast can migrate to infiltrate vascular smooth muscle walls and endothelium and remodel the maternal spiral arteries. On the maternal side, decidual stromal cells accounting for 70% of decidual cells, and dedual immune cells including NK (70%) cells, macrophages (15%) and T (15%) cells. About 5 weeks after implantation, the placenta forms from the trophoblast and decidua. So the fetal trophoblasts, maternal decidual stromal cells and decidual immune cells constitute the maternal–fetal interface. DECs, decidual epithelial cells; DICs, decidual immune cells; DSCs, decidual stromal cells; NK, natural killer.

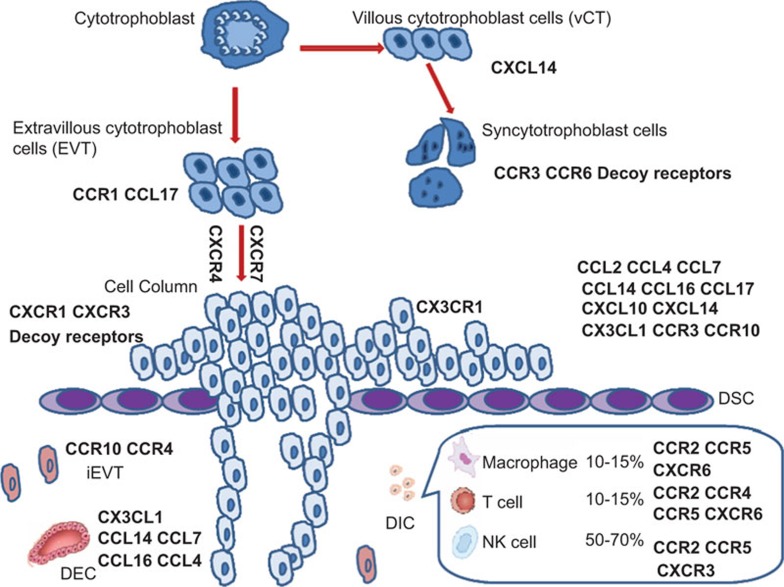

CXCL14 is a relatively newly-identified chemokine with an unidentified receptor and undefined function. CXCL14 is selectively expressed in early villous cytotrophoblasts and DSCs.19 When villous cytotrophoblasts differentiates into syncytiotrophoblast cells, CCR3 and CCR6 become highly expressed.20 CCR1 and CCL17 are localized on extravillous cytotrophoblast cells (EVTs).21,22 CXCR4 and CXCR7 are expressed during the differentiation process of cytotrophoblasts towards the invasive phenotype,23 and their ligand CXCL12 is widely expressed in multiple cell types at the maternal–fetal interface.22 Invasive EVTs express CX3CR1.24 As for the maternal side of the interface, there is widespread expression of chemokines. On DSCs, these include the ligands CCL2, CCL4, CCL7, CCL14, CCL16, CCL17, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL14 and CX3CL1 and the receptors CCR2, CCR3, CCR10, CXCR3 and CXCR4.25,26,27 In addition, CCL2, CCL28 and CX3CL1 are also immunolocalized on the decidual epithelial cells (DECs).28,29 CCR3 and CCR4 are expressed on the invading interstitial EVTs.30,31 In addition to trophoblasts and DSCs, chemokine receptors are expressed on decidual immune cells. CCR2, CCR5 and CXCR4 are present on most of CD45+ cell types. CXCR6 localizes on decidual T cells, NK T cells and macrophages, but not on NK cells.32 Decidual T cells also express CCR4, while most of the NK cells express CXCR3.22,33 Decoy receptors (DARC, D6 and CCX CKR) and ligands are expressed at the maternal–fetal interface, especially by invading trophoblast cells and on the apical side of syncytiotrophoblast cells. The dysregulation of decoy receptors often occurs at sites of fetal arrest.14,34,35 Presented in Figure 2 is a summary of the expression of chemokines and their receptors at the maternal–fetal interface in early human pregnancy.

Figure 2.

The expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors at the human maternal–fetal interface in mid to late first trimester. The expression of chemokines and their receptors in trophoblasts and decidual cells at the maternal–fetal interface in early (from weeks 6–14) human pregnancy is summarized. DEC, decidual epithelial cell; DICs, decidual immune cells; DSCs, decidual stromal cells; iEVT: interstitial extravillous cytotrophoblast cell; NK, natural killer.

The role of chemokines in maternal–fetal crosstalk

During pregnancy, the maternal immune system is in direct contact with fetal alloantigens. Reproductive success depends on the ability to remain tolerant to the fetus and to protect it from infection.36 To achieve this goal, complex molecular dialogues take place at the fetal-maternal interface. Chemokines are multifunctional molecules involved in intercellular communication and signal transduction. They play important physiological and pathological roles not only in the regulation of DIC recruitment and function, but also in embryo implantation and trophoblast invasion.

Enrichment of immune cells in decidua during pregnancy

During decidualization, uterine leukocytes dramatically increase in numbers and account for at least 15% of all cells in the decidua early pregnancy through term. Moreover, they have an unusual composition distinct from blood because the large majority (70%) is CD56brightCD16− NK cells and monocytes (15%), while T cells (10%–15%) represent the minority of the immune cells. The origin of uterine leukocytes remains unclear. One possibility is that they are recruited from peripheral blood and/or other tissues. Because chemokine/chemokine receptor interactions dominate the trafficking of leukocytes, the mechanisms underlying the recruitment and maintenance of DICs most likely involve the expression and secretion of chemokines at the maternal–fetal interface (Table 1).

Table 1. The involvement of chemokine and chemokine receptor signaling in the recruitment of decidual immune cell subtypes.

| Decidual immune cell subtypes | Chemokine-chemokine receptor pairs | Decidual immun cell subtypes | Chemokine-chemokine receptor pairs |

|---|---|---|---|

| NK | CCR1–CCL3 | Mφ | CCR1–CCL3, CCL5 |

| CCR2–CCL2 | CCR2–CCL2 | ||

| CXCR1–CXCL8 | CXCR6–CXCL16 | ||

| CXCR3–CXCL10, CXCL11 | Th2 | CCR4–CCL17 | |

| CXCR4–CXCL12 | |||

| CX3CR1–CX3CL1 | |||

| DC | CCR1–CCL5 | Treg | CCR2–CCL2 |

| CCR2–CCL2 | CCR4–CCL17, CCL22 | ||

| CCR3–CCL7 | CCR5–CCL4 | ||

| CCR5–CCL4 | CCR6–CCL20 | ||

| CCR6–CCL20 | CCR7–CCL19 | ||

| CCR7–CCL21 | CXCR4–CXCL12 |

Abbreviations: DC: dentritic cell; Mφ, macrophage; NK, natural killer; Th2: T helper 2 cell; Treg: regulatory T cell.

Recruitment of NK cells

CD56bright CD16− NK cells are the most abundant immune cells in the decidua.37 Therefore, the chemokines related to the recruitment of decidual NK cells have been the topic of many studies. Several studies have examined which chemotactic factors are potentially involved in the control of CD56bright NK cell accumulation in the uterus.

By screening chemokine receptors on NK cells, Wu et al. have revealed that CD56brightCD16− NK cells express high levels of CXCR4. Through receptor and ligand interactions, placental trophoblasts actively recruit maternal CD56+NK cells into the decidua through the secretion of CXCL12.38 Cytotrophoblasts can also attract CD56bright NK cells by producing macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α (CCL3).39 However, endometrial cells attract CXCR3+NK cell via CXCL10 and CXCL11. Progesterone can enhance CXCL10 and CXCL11 expression in endometrial cells, thus increasing CXCR3+ NK cell numbers in endometrium.40,41 Croy et al.42 reported that, in contrast to human pregnancy, murine NK cell homing to the decidua was independent of CXCR3 and of additional chemokine receptors, such as CCR2.

Decidual cells produce various types of chemokines, such as CCL2, CXCL8, CX3CL1, CXCL10 and CXCL12, at significant levels. These chemokines are differently involved in the migration of peripheral NK (pNK) and decidual NK (dNK) cells into the decidua.28,43,44 Interestingly, CXCL12 and CX3CL1 preferentially attract CD16+ pNK cells, while CXCL10 is essential for the recruitment of CD56highCD16− pNK cells.33,45 Uterine expression of CXCL14 may also play a role in uterine NK-cell recruitment during the early pregnancy.46 However, a clear picture of the effects of CXCL14 on uterine NK-cell recruitment in the context of the uterus is still vague, since a report using knockout models indicates opposite effects of its chemoattractant roles on many types of leukocytes.47 These studies suggest that NK cells use more than one type of receptor-ligand pairing to enter the uterus, and these chemokines may act sequentially or in combination to contribute to the accumulation of NK cells in the decidual tissues.

Recruitment of antigen-presenting cells (macrophages and DCs)

As initial responders to external pathogens and alloantigens, antigen-presenting cells play a central role in the delicate balance between protective immunity and tolerance. Macrophages are the most abundant antigen-presenting cell in the decidua (DCs only account for 1% of the leukocytes).48 Microarray-based gene expression analysis indicates that macrophages isolated from decidua during the first trimester adopt an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, with upregulation of CCL18, CD209 (DC-SIGN), mannose receptor C type-1, fibronectin 1 and insulin-like growth factor-1.49 CCL2, CCL3 and regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (CCL5) are possible factors involved in the recruitment and functionality of decidual macrophages.50,51,52 It was also shown that trophoblast cells regulate monocyte migration through the production of CCL3 and CCL2.39,50 Our previous study has demonstrated that DSC-secreted CCL2 and trophoblast-secreted CXCL16 contribute to the recruitment of peripheral monocyte to the decidua.32,53 Furthermore, decidual macrophages secrete high level of CCL2 that recruit additional macrophages into the decidua.54

DCs are considered to be the immune ‘guardians' in the uterine-mucosa, capable of inducing tolerance under normal physiological conditions.55 DCs in the decidua produce less IL-12 than do peripheral blood DCs, and decidual myeloid DCs induce a higher percentage of T-helper type 2 (Th2) lymphocytes than do peripheral blood DCs.56 CCL2 and CCL5 secreted by the first trimester decidua are responsible for the accumulation of DCs in the decidua.57

Recruitment of T cells

Compared with CD56brightCD16−NK cells and macrophages, T cells are less abundant at the maternal–fetal interface, but have been proposed to play an important role in immune regulation. It has long been accepted that T-cell activity at the fetal-maternal interface is skewed toward Th2-like bias, thus contributing to a pregnancy-protecting environment that may be disturbed in recurrent abortions,37,58 Recently, more subsets of CD4+ T cells have been characterized at the maternal–fetal interface. There is a balance between the Th1 and Th2 cells, as well as Th17 and regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the first-trimester human decidua.59

Chemokine receptors are differentially expressed on polarized Th cells. Typically, CXCR3 and CCR5 are preferentially expressed on polarized Th1 cells, whereas CCR3, CCR4 and CCR8 are associated with the Th2 phenotype.60 The possibility that Th2 cells are preferentially recruited by uterine cells through chemokine secretion has been proposed. CCL17, a Th2 chemokine, is produced by trophoblasts and endometrial gland cells, and regulates the infiltration of CCR4+ T lymphocytes into human decidua during the early pregnancy.61 Previously, we confirmed that decidual DCs instructed by trophoblasts produce high levels of IL-10 and CCL17, inducing a Th2 bias at the maternal–fetal interface.62 Aggressive CCR6+ Th1 cells are much less frequent in decidua as compared with blood.63 CXCL9, the Th1/Tc1-attracting chemokine is silenced in decidua, thus restricting Th1 cell recruitment to the maternal–fetal interface.64

Tregs have been identified during pregnancy in both humans and mice, and are thought to play a role in maternal immunotolerance.65,66,67 In human pregnancy, CD4+CD25high Tregs localize preferentially to the decidua compared to peripheral blood, constituting approximately 22% and 6.5% of leukocytes, respectively.68,69 CCL19, a major chemokine generated by glandular and luminal epithelial cells, acts through CCR7 and mediates the recruitment of Tregs from the circulation into the uterus.70 Expression of CCL2, CCL22, CCL17, CCL4 and CCL20 in the uterus may selectively recruit Tregs from peripheral tissues.71,72,73 Lin et al.74 have demonstrated that CXCL12 produced by trophoblast enhances exogenous CD4+CD25+ T-cell migration and prevents embryo loss in non-obese diabetic mice. Therefore, through interactions of chemokines and their receptors, the maternal–fetal interface recruits immune-regulatory Th2 and Treg cells, helping to form an immune tolerant microenvironment.

Chemokine instruction to decidual immune cells

A distinctive immune tolerance-promoting environment develops at the maternal–fetal interface to avoid rejection of the embryo by the maternal immune system. DICs have special features in local cytokine production, downregulation of cytotoxicity and promotion of placental development that pace the progression of a healthy pregnancy.75 How the distinct DICs develop has received intense attention. Increasing data indicate that the local environment drives them into functionally different subsets.76,77,78 Chemokine may be the key to regulation of DIC function.

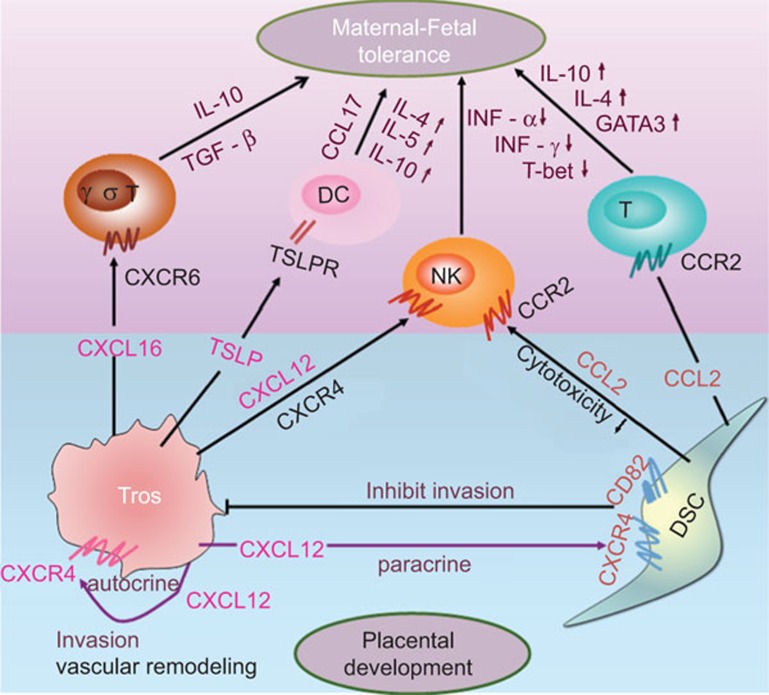

NK cells, the dominant immune cell type in the decidua during early pregnancy, are critical in maintaining maternal–fetal tolerance and regulating placental vascular remodeling owing to their unique phenotype.79 Decidual NK cells are recruited from peripheral blood via chemokine/chemokine receptor interactions. Coculture of pNK cells and trophoblast cells results in significant downregulation of CCR1, CCR5, CXCR1, CXCR4 and CX3CR1, while CXCR3 is upregulated.33 This suggests that pNK cells undergo reprogramming of their chemokine receptor profile once exposed to the uterine microenvironment. Interestingly, the chemokine receptor profile of pNK cells instructed by trophoblast cells closely resembles that of dNK cells. CXCL12 is required for NK development in addition to recruitment, suggesting that the high CXCL12 levels in the decidual environment might contribute to the unique phenotype and function of dNK cells.80 Our unpublished data indeed demonstrate that trophoblasts instruct NK cell phenotype and function via CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling. Additionally, CCL2 secreted by DSC inhibits NK cells cytotoxicity by upregulation of SOCS3.81

CCL2 and DSC-derived supernatant can promote Th2 cytokine production while inhibiting Th1 cytokines production by DICs, suggesting that DSCs induce a decidual Th2 bias via CCL2 secretion. This modulation may occur by affecting the expression of the Th1/Th2-specific transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3, thus, contributing to the Th2 bias at the maternal–fetal interface. Th2 cytokines can also promote CCL2 secretion by DSCs, further promoting this bias in the decidua,16,53 which suggests a positive regulatory loop. Furthermore, CXCL12 produced by trophoblast also contributes to Th2 bias at the maternal–fetal interface.82 Although the exact mechanism is not known, CXCL12 may associate with signal transducers and activator of transcription-6.83,84 Huang and Fan reported that γδT cells recruited into the decidua via CXCL16/CXCR6 interaction play an important role in the Th2 bias at the maternal–fetal interface and in the development and progression of the placenta by producing high levels of IL-10 and TGF-β.32,85 Therefore, trophoblasts and DSCs appear to induce the differentiation of immune cells into an embryo-supporting phenotype.

Regulation of chemokines on trophoblast invasiveness and placental angiogenesis

During human placental development, cytotrophoblasts differentiate to form the syncytium or invade the decidual wall to breach maternal vessels and establish blood flow to the intervillous space. Trophoblast migration within the decidualized endometrium and uterine vasculature is essential for normal placental and fetal development.86,87

Chemokines have roles in key aspects of placentation, including cytotrophoblast differentiation, and proliferation, as well as in recruitment of immune cells into the decidua.88 The placenta is a rich source of CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4.89 We found that first-trimester human trophoblasts promote their own invasiveness and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity through co-expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4.90 Furthermore, CXCL12 promotes the crosstalk between trophoblasts and DSCs in human first-trimester pregnancy. This crosstalk enhances trophoblast invasiveness by amplifying MMP-9 and MMP-2 secretion from trophoblast and DSCs,90 but also limits over-invasiveness of trophoblasts by upregulating CD82 (tumor metastasis suppressor gene) expression in a paracrine manner.91 CXCL12 promotes human trophoblast proliferation and invasion via epithelial growth factor receptor and extracellular signal regulated kinase activation.92 CXCL12 can also activate NF-κB, and induce p65 nuclear translocation,93 inhibiting trophoblast invasion by enhancing transcription of CD82.

CXCL16 secreted by trophoblasts can induce invasive growth of trophoblasts in an autocrine manner.94 CCR1 is present on the surface of EVTs grown from chorionic villous explants. CCL5 and CCL2, the ligands of CCR1, are expressed by decidual tissue and promote the migration of the EVTs from the explant cultures in vitro.95 These studies suggest that decidual cells regulate trophoblast invasiveness via interactions of CCR1 and its ligands. Furthermore, decidual epithelial cells promote villous cytotrophoblast survival and EVT migration via production of CXCL8, CXCL10 and CXCL11 that bind to CXCR1 and CXCR3 on trophoblast cells.96,97,98 CCL5 secreted by decidual tissue is a chemoattractant for human invading trophoblasts and blastocysts. However, some chemokines, such as CXCL14 and CXCL6, inhibit trophoblast invasive growth through downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity.19,99 DECs promote CCL17 expression by decidual macrophage with alternative activation that controls trophoblast invasion induced by NK cells.100 These results suggest that the chemokine-mediated crosstalk between decidual cells and trophoblasts at the maternal–fetal interface is essential for proper trophoblast invasion and placental development.

During placentation, invasive trophoblasts interact with arteries rather than veins, which has been a mystery for a long time. Recent progress demonstrates that ephrin signaling is critical for the preferential remodeling of arterioles by trophoblasts. This process is mediated through limiting CXCL12-induced migration of arterial endothelial cells into veins.101 In addition, human endometrial microvascular endothelial cells produce CXCL9 and CXCL10,102 which stimulate the proliferation of myofibroblast-like renal perivascular cells, and display angiostatic activity through a protein kinase A-mediated inhibition of m-calpain.103,104

It is postulated that extensive crosstalk between placental trophoblasts and DICs, produces angiogenic factors near maternal spiral arteries.58 Maternal DICs, especially dNK cells and also DCs, play an important role in the immune regulation of trophoblast invasion and uterine spiral arteries remodeling.105 Although this process is still not well understood, chemokines and their receptors are likely involved in guiding cytotrophoblasts to the decidua and maternal vessels and in attracting immunocompetent cells to the implantation site by either recruitment of VEGF-expressing macrophages or direct stimulation of chemokine receptors on the endothelium.106,107,108

By producing CXCL8 and CXCL10, dNK cells promote trophoblast invasion toward the spiral arteries via interactions of these chemokines and their receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR3.109,110 Decidual CD56brightCD16− NK cells are the main source of IFN-γ at the maternal–fetal interface. IFN-γ can upregulate the production of CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL8, and CCL5. The release of these cytokines enhances trophoblast invasion and promotes vascular remodeling. Besides IFN-γ, uterine NK cells secrete other angiogenic factors, including VEGF, angiopoietin-2 and placental growth factor.111,112,113

DCs are associated with vascular growth during the early gestation.58,105 CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling is important in the regulation of decidual angiogenesis by DCs. Blocking CXCR4+ DC homing during the early gestation results in disorganized decidual vasculature with impaired spiral artery remodeling later in gestation. In mice, adoptive transfer of CXCR4+ DC promotes adequate remodeling of the spiral arteries in the decidua, thus rescuing early pregnancy.114

Involvement of chemokines in pregnancy complications

The expression of chemokines and their receptors at the maternal–fetal interface has important implications for understanding the role of chemokines in the regulation of placental growth and development, and in maternal–fetal tolerance. The abnormal expression of chemokines is related to pathological pregnancy, such as miscarriage, pre-eclampsia and preterm labour.

Miscarriage is the most common complication of pregnancy. One well-accepted cause of miscarriage is related to an abnormal shift towards the Th1 type response. CXCR3 and CCR5 are expressed preferentially on Th1-type cells, while CCR3 and CCR4 are expressed on Th2-type cells.60 In a mouse model of miscarriage, CCR3 expression on peripheral blood CD4+ T cells is significantly decreased, while the expression of CCR5 and CXCR3 is markedly increased. This is also observed in humans. Furthermore, paternal leukocyte immunization of women who have experienced three or more spontaneous abortions increased levels of Th2-related CCR4 expression on CD4+ T cells and improved pregnancy outcome.115

Fetal loss in animals and humans is frequently associated with inflammatory conditions. D6 is a promiscuous chemokine receptor with a decoy function that degrades most inflammatory CC chemokines.116 Treatment of D6-deficient pregnant mice with LPS or antiphospholipid autoantibody results in fetal loss with higher levels of inflammatory CC chemokines and increased leukocyte infiltrate in the placenta. Interestingly, blocking inflammatory chemokines rescues the fetal loss.35 These results indicate a critical role of D6 in the protection from fetal loss induced by systemic inflammation and antiphospholipid antibodies.

Pre-eclampsia affects at least 5% of pregnancies globally and is a leading cause of both maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, even in developed countries.117 The expression of CCL2 and CCL5 is increased in pre-eclampsia as is CCL2 and CCL5 expression by first-trimester decidual cells may account for the accumulation of macrophages and DCs in pre-eclamptic decidua.52,57 Serum levels of CXCL10 and CXCL8 are also elevated during pre-eclampsia compared with healthy pregnancies, resulting in an overall pro-inflammatory systemic environment.118,119 Increased CXCL10 and CCL2 concentrations in pre-eclamptic patients significantly correlate with blood pressure values, and renal and liver function parameters.52 These chemokines and their underlying signaling molecules are potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets for pre-eclampsia management.

Appreciating changes in chemokine expression helps our understanding of their roles during the inflammatory response that is associated with spontaneous preterm labour. The search for markers of preterm labour has identified increased expression of CXCL8 in cervical mucus, and CCL2 and MIF in maternal serum or amniotic fluid.120,121,122 The presence of CCL8, CCL5, CCL20, CXCL5 and CCL7 in amniotic fluid is associated with microbial invasion and amniotic cavity inflammation during preterm labour.123,124,125,126 CXCL11 level is increased in amniotic fluid during second trimester in women who subsequently developed preterm labour.127 Increased levels of the CCR6 ligand CCL20 in amniotic fluid was associated with prematurity.128 Elevated CXCL10 puts patients at risk for spontaneous preterm delivery after 32 weeks of gestation.129

As discussed above, chemokines are involved in pregnancy complications, and some are key players in pathological conditions. Therefore, chemokine/chemokine receptor interactions should be targeted as a therapeutic option to treat specific pregnancy complications. For example, the pattern of CXCR4 (specific receptor for CXCL12) expression on peripheral blood NK cells was analyzed and NK-cell migration was demonstrated in vitro and in vivo by migratory assays. Furthermore, CXCL12 is produced by murine trophoblast cells and the recruitment of peripheral CXCR4-expressing ITGA2CISG20C NK cells into pregnant uteri can prevent embryo loss in non-obese diabetic mice.130 However, whether this is clinically relevant still requires further investigation.

Though we previously stated that an anti-inflammatory microenvironment is necessary for a successful pregnancy, additional studies report that local injury of the endometrium triggers an inflammatory response characterized by an influx of macrophages/DCs and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines that actually facilitates successful implantation in patients using assisted reproductive technologies.131,132 In a controlled clinical study, analysis of cytokines in endometrial samples recovered from the biopsy-treated patients revealed increased CCL4 expression, which in turn recruits macrophages/DCs to the site of implantation. The abundance of these cells and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines positively correlate with pregnancy outcomes.133 The increased CCL4 expression could possibly serve as a predictor of implantation competence and may also be used to clinically predict pregnancy outcomes.

Conclusions

Successful pregnancy requires an optimal interaction between maternal and fetal cells for mutual tolerance and prevention of excessive inflammation. The mammalian fetus has been perceived, paradoxically, as a successful allograft, successful tumor, or a successful parasite. Local suppression of maternal immune responses at the maternal–fetal interface is necessary, while systemic immune reactions to allogeneic tissue or infection must remain undisturbed. Chemokines regulate multiple events that are closely associated with normal pregnancy including fetal protection and placental development by modulation of homeostasis and functions of immune and trophoblast cells in a paracrine or autocrine manner (Figure 3). Chemokines also participate in many pathological conditions, and are poised in a central switchboard position when immune surveillance and reciprocal tolerance are needed. Our understanding of how the chemokine–chemokine receptor network orchestrates crucial events during normal pregnancy, as well as during pregnancy complications, remains incomplete. Nevertheless, recent advances in molecular biology have dramatically enhanced our knowledge of the immunobiology of the maternal–fetal interface. Further research in these areas will give us more avenues for preventing pregnancy complication related to deficient trophoblast biological function and faulty maternal–fetal immune interactions.

Figure 3.

Regulation of maternal–fetal tolerance and placental development via chemokine/chemokine receptor interactions. The interaction of trophoblast-derived CXCL12 with CXCR4 promotes trophoblast invasiveness in an autocrine manner, and prevents excessive trophoblast invasion by enhancing CD82 expression on DSCs in a paracrine manner. Additionally, CXCL12 recruit and instruct NK cells. Trophoblast-derived CXCL16 and DSC-derived CCL2 bind to CXCR6+ T cells and CCR2+ T cells, respectively, contributing to decidual T-cell accumulation and Th2 bias at the maternal–fetal interface. Trophoblasts actively secrete TSLP inducing a classic Th2 bias at the maternal–fetal interface by instructing decidual DCs to produce high levels of CCL17. ↑: upregulation; ↓: downregulation. DSC: decidual stromal cell; dNK, decidual natural killer; Tros, trophoblasts; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Key Project of Shanghai Basic Research from Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission (STCSM) (12JC1401600 to DJL); the Key Project of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (MECSM) (14ZZ013 to MRD) and Nature Science Foundation from National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (NSFC31270969 to DJL; NSFC81070537, NSFC31171437 and NSFC81370770 to MRD).

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johrer K, Pleyer L, Olivier A, Maizner E, Zelle-Rieser C, Greil R. Tumour-immune cell interactions modulated by chemokines. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:269–290. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-Gaspar M, Billing JS, Spriewald BM, Wood KJ. Chemokine gene expression during allograft rejection: comparison of two quantitative PCR techniques. J Immunol Methods. 2005;301:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomiyama H, Hieshima K, Osada N, Kato-Unoki Y, Otsuka-Ono K, Takegawa S, et al. Extensive expansion and diversification of the chemokine gene family in zebrafish: identification of a novel chemokine subfamily CX. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:222. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Gomperts BN, Belperio JA, Keane MP. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:593–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britschgi MR, Favre S, Luther SA. CCL21 is sufficient to mediate DC migration, maturation and function in the absence of CCL19. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1266–1271. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L, Fukata M, Thirunarayanan N, Martin AP, Arnaboldi P, Maussang D, et al. Toll-like receptor signaling in small intestinal epithelium promotes B-cell recruitment and IgA production in lamina propria. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:529–538. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurachi M, Kurachi J, Suenaga F, Tsukui T, Abe J, Ueha S, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR3 facilitates CD8+ T cell differentiation into short-lived effector cells leading to memory degeneration. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1605–1620. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augsten M, Hagglof C, Olsson E, Stolz C, Tsagozis P, Levchenko T, et al. CXCL14 is an autocrine growth factor for fibroblasts and acts as a multi-modal stimulator of prostate tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3414–3419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813144106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facciabene A, Peng X, Hagemann IS, Balint K, Barchetti A, Wang LP, et al. Tumour hypoxia promotes tolerance and angiogenesis via CCL28 and Treg cells. Nature. 2011;475:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung E, Cho JL, Sparwasser T, Medoff BD, Luster AD. Inhibiting CXCR3-dependent CD8+ T cell trafficking enhances tolerance induction in a mouse model of lung rejection. J Immunol. 2011;186:6830–6838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroni EM, Bonecchi R, Buracchi C, Savino B, Mantovani A, Locati M. Chemokine decoy receptors: new players in reproductive immunology. Immunol Invest. 2008;37:483–497. doi: 10.1080/08820130802191318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew AL, Tan WY, Khoo BY. Potential combinatorial effects of recombinant atypical chemokine receptors in breast cancer cell invasion: a research perspective. Biomed Rep. 2013;1:185–192. doi: 10.3892/br.2013.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels JM, Linton NF, van den Heuvel MJ, Cnossen SA, Edwards AK, Croy BA, et al. Expression of chemokine decoy receptors and their ligands at the porcine maternal–fetal interface. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:304–313. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li DJ, Yuan MM, Zhu Y, Wang MY. The expression of CXCR4/CXCL12 in first-trimester human trophoblast cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1877–1885. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YY, Du MR, Guo PF, He XJ, Zhou WH, Zhu XY, et al. Regulation of C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 and its receptor in human decidual stromal cells by pregnancy-associated hormones in early gestation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2733–2742. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhu XY, Du MR, Wu X, Wang MY, Li DJ. Chemokine CXCL16, a scavenger receptor, induces proliferation and invasion of first-trimester human trophoblast cells in an autocrine manner. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1083–1091. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Huang YH, Li MQ, Meng YH, Chen X, et al. Trophoblasts-derived chemokine CCL24 promotes the proliferation, growth and apoptosis of decidual stromal cells in human early pregnancy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:1028–1037. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang H, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Peng H, Ning L, et al. The cytokine gene CXCL14 restricts human trophoblast cell invasion by suppressing gelatinase activity. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5596–5605. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas GC, Thirkill TL. Chemokine receptor expression by human syncytiotrophoblast—a review. Placenta. 2001;22 Suppl A:S24–S28. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Higuchi T, Sato Y, Nishioka Y, Zeng BX, Yoshioka S, et al. Regulation of human extravillous trophoblast function by membrane-bound peptidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1751:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Red-Horse K, Drake PM, Fisher SJ. Human pregnancy: the role of chemokine networks at the fetal–maternal interface. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2004;6:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1462399404007720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanz A, Baston-Bust D, Krussel JS, Heiss C, Janni W, Hess AP. CXCR7 and syndecan-4 are potential receptors for CXCL12 in human cytotrophoblasts. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;89:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake PM, Red-Horse K, Fisher SJ. Reciprocal chemokine receptor and ligand expression in the human placenta: implications for cytotrophoblast differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:877–885. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Red-Horse K, Drake PM, Gunn MD, Fisher SJ. Chemokine ligand and receptor expression in the pregnant uterus: reciprocal patterns in complementary cell subsets suggest functional roles. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2199–2213. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63071-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake PM, Red-Horse K, Fisher SJ. Chemokine expression and function at the human maternal–fetal interface. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2002;3:159–165. doi: 10.1023/a:1015463130306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arck PC, Hecher K. Fetomaternal immune cross-talk and its consequences for maternal and offspring's health. Nat Med. 2013;19:548–556. doi: 10.1038/nm.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlino C, Stabile H, Morrone S, Bulla R, Soriani A, Agostinis C, et al. Recruitment of circulating NK cells through decidual tissues: a possible mechanism controlling NK cell accumulation in the uterus during early pregnancy. Blood. 2008;111:3108–3115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Zhang YY, Tang CL, Wang SC, Piao HL, Tao Y, et al. Chemokine CCL28 induces apoptosis of decidual stromal cells via binding CCR3/CCR10 in human spontaneous abortion. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013;19:676–686. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan NJ, Jones RL, White CA, Salamonsen LA. The chemokines, CX3CL1, CCL14, and CCL4, promote human trophoblast migration at the feto-maternal interface. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:896–904. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CM, Hou L, Zhang H, Zhang WY.CCL17 induces trophoblast migration and invasion by regulating matrix metalloproteinase and integrin expression in human first-trimester placenta Reprod Sci 2014. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huang Y, Zhu XY, Du MR, Li DJ. Human trophoblasts recruited T lymphocytes and monocytes into decidua by secretion of chemokine CXCL16 and interaction with CXCR6 in the first-trimester pregnancy. J Immunol. 2008;180:2367–2375. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlino C, Stabile H, Morrone S, Bulla R, Soriani A, Agostinis C, et al. Recruitment of circulating NK cells through decidual tissues: a possible mechanism controlling NK cell accumulation in the uterus during early pregnancy. Blood. 2008;111:3108–3115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroni EM, Bonecchi R, Buracchi C, Savino B, Mantovani A, Locati M. Chemokine decoy receptors: new players in reproductive immunology. Immunol Invest. 2008;37:483–497. doi: 10.1080/08820130802191318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez DL, Buracchi C, Borroni EM, Dupor J, Bonecchi R, Nebuloni M, et al. Protection against inflammation- and autoantibody-caused fetal loss by the chemokine decoy receptor D6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2319–2324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607514104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warning JC, McCracken SA, Morris JM. A balancing act: mechanisms by which the fetus avoids rejection by the maternal immune system. Reproduction. 2011;141:715–724. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima A, Shima T, Inada K, Ito M, Saito S. The balance of the immune system between T cells and NK cells in miscarriage. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67:304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2012.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Jin LP, Yuan MM, Zhu Y, Wang MY, Li DJ. Human first-trimester trophoblast cells recruit CD56brightCD16− NK cells into decidua by way of expressing and secreting of CXCL12/stromal cell-derived factor 1. J Immunol. 2005;175:61–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake PM, Gunn MD, Charo IF, Tsou CL, Zhou Y, Huang L, et al. Human placental cytotrophoblasts attract monocytes and CD56bright natural killer cells via the actions of monocyte inflammatory protein 1alpha. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1199–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.10.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabrane-Ferrat N, Siewiera J. The up side of decidual natural killer cells: new developments in immunology of pregnancy. Immunology. 2014;141:490–497. doi: 10.1111/imm.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentman CL, Meadows SK, Wira CR, Eriksson M. Recruitment of uterine NK cells: induction of CXC chemokine ligands 10 and 11 in human endometrium by estradiol and progesterone. J Immunol. 2004;173:6760–6766. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Kang Z, Anderson LN, He H, Lu B, Croy BA. Analysis of the contributions of L-selectin and CXCR3 in mediating leukocyte homing to pregnant mouse uterus. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;53:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JJ, Qin S, Unutmaz D, Soler D, Murphy KE, Hodge MR, et al. Unique subpopulations of CD56+ NK and NK-T peripheral blood lymphocytes identified by chemokine receptor expression repertoire. J Immunol. 2001;166:6477–6482. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoni A, Carlino C, Gismondi A. Uterine NK cell development, migration and function. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16:202–210. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Wald O, Goldman-Wohl D, Prus D, Markel G, Gazit R, et al. CXCL12 expression by invasive trophoblasts induces the specific migration of CD16− human natural killer cells. Blood. 2003;102:1569–1577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starnes T, Rasila KK, Robertson MJ, Brahmi Z, Dahl R, Christopherson K, et al. The chemokine CXCL14 (BRAK) stimulates activated NK cell migration: implications for the downregulation of CXCL14 in malignancy. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1101–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuter S, Schaerli P, Roos RS, Brandau O, Bosl MR, von Andrian UH, et al. Murine CXCL14 is dispensable for dendritic cell function and localization within peripheral tissues. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:983–992. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01648-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban YL, Kong BH, Qu X, Yang QF, Ma YY. BDCA-1+, BDCA-2+ and BDCA-3+ dendritic cells in early human pregnancy decidua. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;151:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C, Mjosberg J, Matussek A, Geffers R, Matthiesen L, Berg G, et al. Gene expression profiling of human decidual macrophages: evidence for immunosuppressive phenotype. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams VM, Visintin I, Aldo PB, Guller S, Romero R, Mor G. A role for TLRs in the regulation of immune cell migration by first trimester trophoblast cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:8096–8104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake PM, Gunn MD, Charo IF, Tsou CL, Zhou Y, Huang L, et al. Human placental cytotrophoblasts attract monocytes and CD56bright natural killer cells via the actions of monocyte inflammatory protein 1alpha. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1199–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.10.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood CJ, Matta P, Krikun G, Koopman LA, Masch R, Toti P, et al. Regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta in first trimester human decidual cells: implications for preeclampsia. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:445–452. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YY, He XJ, Guo PF, Du MR, Shao J, Li MQ, et al. The decidual stromal cells-secreted CCL2 induces and maintains decidual leukocytes into Th2 bias in human early pregnancy. Clin Immunol. 2012;145:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozner AE, Dambaeva SV, Drenzek JG, Durning M, Golos TG. Modulation of cytokine and chemokine secretions in rhesus monkey trophoblast co-culture with decidual but not peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:115–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blois SM, Kammerer U, Alba SC, Tometten MC, Shaikly V, Barrientos G, et al. Dendritic cells: key to fetal tolerance. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:590–598. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.060632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S, Tsuda H, Sakai M, Hori S, Sasaki Y, Futatani T, et al. Predominance of Th2-promoting dendritic cells in early human pregnancy decidua. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:514–522. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1102566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Wu ZM, Yang H, Huang SJ. NFkappaB and JNK/MAPK activation mediates the production of major macrophage- or dendritic cell-recruiting chemokine in human first trimester decidual cells in response to proinflammatory stimuli. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2502–2511. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton NF, Wessels JM, Cnossen SA, van den Heuvel MJ, Croy BA, Tayade C. Angiogenic DC-SIGN+ cells are present at the attachment sites of epitheliochorial placentae. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:63–71. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Kim JY, Lee M, Gilman-Sachs A, Kwak-Kim J. Th17 and regulatory T cells in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2012.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrbe U, Siveke J, Hamann A. Th1/Th2 subsets: distinct differences in homing and chemokine receptor expression. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1999;21:263–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00812257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H, Michimata T, Hayakawa S, Tanebe K, Sakai M, Fujimura M, et al. A Th2 chemokine, TARC, produced by trophoblasts and endometrial gland cells, regulates the infiltration of CCR4+ T lymphocytes into human decidua at early pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2002;48:1–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2002.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo PF, Du MR, Wu HX, Lin Y, Jin LP, Li DJ. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin from trophoblasts induces dendritic cell-mediated regulatory TH2 bias in the decidua during early gestation in humans. Blood. 2010;116:2061–2069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjosberg J, Berg G, Jenmalm MC, Ernerudh J. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and T helper 1, T helper 2, and T helper 17 cells in human early pregnancy decidua. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:698–705. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancy P, Tagliani E, Tay CS, Asp P, Levy DE, Erlebacher A. Chemokine gene silencing in decidual stromal cells limits T cell access to the maternal–fetal interface. Science. 2012;336:1317–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.1220030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuere C, Zenclussen ML, Schumacher A, Langwisch S, Schulte-Wrede U, Teles A, et al. Kinetics of regulatory T cells during murine pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58:514–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alijotas-Reig J, Melnychuk T, Gris JM.Regulatory T cells, maternal-foetal immune tolerance and recurrent miscarriage: new therapeutic challenging opportunities Med Clin (Barc) 2014. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Sakai M, Miyazaki S, Higuma S, Shiozaki A, Saito S. Decidual and peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in early pregnancy subjects and spontaneous abortion cases. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:347–353. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen J, Mottonen M, Alanen A, Lassila O. Phenotypic characterization of regulatory T cells in the human decidua. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:373–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin LR, Moldenhauer LM, Prins JR, Bromfield JJ, Hayball JD, Robertson SA. Seminal fluid regulates accumulation of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the preimplantation mouse uterus through expanding the FOXP3+ cell pool and CCL19-mediated recruitment. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:397–408. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallikourdis M, Andersen KG, Welch KA, Betz AG. Alloantigen-enhanced accumulation of CCR5+ ‘effector' regulatory T cells in the gravid uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:594–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604268104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin LR, Prins JR, Robertson SA. Regulatory T-cells and immune tolerance in pregnancy: a new target for infertility treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:517–535. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrasse-Jeze G, Klatzmann D, Charlotte F, Salomon BL, Cohen JL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory/suppressor T cells prevent allogeneic fetus rejection in mice. Immunol Lett. 2006;102:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Xu L, Jin H, Zhong Y, Di J, Lin QD. CXCL12 enhances exogenous CD4+CD25+ T cell migration and prevents embryo loss in non-obese diabetic mice. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2687–2696. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arck PC, Hecher K. Fetomaternal immune cross-talk and its consequences for maternal and offspring's health. Nat Med. 2013;19:548–556. doi: 10.1038/nm.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres-Bartho J. Progesterone-mediated immunomodulation in pregnancy: its relevance to leukocyte immunotherapy of recurrent miscarriage. Immunotherapy. 2009;1:873–882. doi: 10.2217/imt.09.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redzovic A, Laskarin G, Dominovic M, Haller H, Rukavina D. Mucins help to avoid alloreactivity at the maternal fetal interface. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:542152. doi: 10.1155/2013/542152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlebacher A. Mechanisms of T cell tolerance towards the allogeneic fetus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:23–33. doi: 10.1038/nri3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacca P, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Natural killer cells in human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;97:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M, Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T, Oishi S, Fujii N, Nagasawa T. CXCL12–CXCR4 chemokine signaling is essential for NK-cell development in adult mice. Blood. 2011;117:451–458. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Wang Q, Deng B, Wang H, Dong Z, Qu X, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 secreted by decidual stromal cells inhibits NK cells cytotoxicity by up-regulating expression of SOCS3. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao HL, Tao Y, Zhu R, Wang SC, Tang CL, Fu Q, et al. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is involved in the maintenance of Th2 bias at the maternal/fetal interface in early human pregnancy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:423–430. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Gunst KV, Sarvetnick N. STAT4/6-dependent differential regulation of chemokine receptors. Clin Immunol. 2006;118:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao HL, Tao Y, Zhu R, Wang SC, Tang CL, Fu Q, et al. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is involved in the maintenance of Th2 bias at the maternal/fetal interface in early human pregnancy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:423–430. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan DX, Duan J, Li MQ, Xu B, Li DJ, Jin LP. The decidual gamma-delta T cells up-regulate the biological functions of trophoblasts via IL-10 secretion in early human pregnancy. Clin Immunol. 2011;141:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier M. Decidualisation and angiogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Hanssens M. The uterine spiral arteries in human pregnancy: facts and controversies. Placenta. 2006;27:939–958. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan NJ, Salamonsen LA. Role of chemokines in the endometrium and in embryo implantation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:266–272. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328133885f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li DJ, Yuan MM, Zhu Y, Wang MY. The expression of CXCR4/CXCL12 in first-trimester human trophoblast cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1877–1885. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou WH, Du MR, Dong L, Yu J, Li DJ. Chemokine CXCL12 promotes the cross-talk between trophoblasts and decidual stromal cells in human first-trimester pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2669–2679. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MQ, Tang CL, Du MR, Fan DX, Zhao HB, Xu B, et al. CXCL12 controls over-invasion of trophoblasts via upregulating CD82 expression in DSCs at maternal–fetal interface of human early pregnancy in a paracrine manner. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4:276–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB, Tang CL, Hou YL, Xue LR, Li MQ, Du MR, et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 axis triggers the activation of EGF receptor and ERK signaling pathway in CsA-induced proliferation of human trophoblast cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R, Galvez BG, Pusterla T, de Marchis F, Cossu G, Marcu KB, et al. Cells migrating to sites of tissue damage in response to the danger signal HMGB1 require NF-kappaB activation. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:33–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhu XY, Du MR, Wu X, Wang MY, Li DJ. Chemokine CXCL16, a scavenger receptor, induces proliferation and invasion of first-trimester human trophoblast cells in an autocrine manner. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1083–1091. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Higuchi T, Yoshioka S, Tatsumi K, Fujiwara H, Fujii S. Trophoblasts acquire a chemokine receptor, CCR1, as they differentiate towards invasive phenotype. Development. 2003;130:5519–5532. doi: 10.1242/dev.00729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Osuga Y, Koga K, Yoshino O, Hirata T, Morimoto C, et al. The expression and possible roles of chemokine CXCL11 and its receptor CXCR3 in the human endometrium. J Immunol. 2006;177:8813–8821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka K, Nojima H, Watanabe F, Chang KT, Christenson RK, Sakai S, et al. Regulation of blastocyst migration, apposition, and initial adhesion by a chemokine, interferon gamma-inducible protein 10 kDa (IP-10), during early gestation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29048–29056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Osuga Y, Hasegawa A, Kodama A, Tajima T, Hamasaki K, et al. Interleukin (IL)-1beta stimulates migration and survival of first-trimester villous cytotrophoblast cells through endometrial epithelial cell-derived IL-8. Endocrinology. 2009;150:350–356. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Hou L, Li CM, Zhang WY. The chemokine CXCL6 restricts human trophoblast cell migration and invasion by suppressing MMP-2 activity in the first trimester. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2350–2362. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskarin G, Medancic SS, Redzovic A, Duric D, Rukavina D. Specific decidual CD14+ cells hamper cognate NK cell proliferation and cytolytic mediator expression after mucin 1 treatment in vitro. J Reprod Immunol. 2012;95:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Red-Horse K, Kapidzic M, Zhou Y, Feng KT, Singh H, Fisher SJ. EPHB4 regulates chemokine-evoked trophoblast responses: a mechanism for incorporating the human placenta into the maternal circulation. Development. 2005;132:4097–4106. doi: 10.1242/dev.01971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaya K, Nakayama T, Daikoku N, Fushiki S, Honjo H. Spatial and temporal expression of ligands for CXCR3 and CXCR4 in human endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2470–2476. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacchi A, Romagnani P, Romanelli RG, Efsen E, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, et al. Signal transduction by the chemokine receptor CXCR3: activation of Ras/ERK, Src, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt controls cell migration and proliferation in human vascular pericytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9945–9954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar RJ, Yates CC, Wells A. IP-10 blocks vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell motility and tube formation via inhibition of calpain. Circ Res. 2006;98:617–625. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000209968.66606.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blois SM, Klapp BF, Barrientos G. Decidualization and angiogenesis in early pregnancy: unravelling the functions of DC and NK cells. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;88:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CE, Liu T, Montel V, Hsiao G, Lester RD, Subramaniam S, et al. Chemoattractant signaling between tumor cells and macrophages regulates cancer cell migration, metastasis and neovascularization. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong KH, Ryu J, Han KH. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-induced angiogenesis is mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A. Blood. 2005;105:1405–1407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Mostarica-Stojkovic M, Andjelkovic AV. CCL2 regulates angiogenesis via activation of Ets-1 transcription factor. J Immunol. 2006;177:2651–2661. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bouteiller P, Tabiasco J. Killers become builders during pregnancy. Nat Med. 2006;12:991–992. doi: 10.1038/nm0906-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bouteiller P, Piccinni MP. Human NK cells in pregnant uterus: why there. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:401–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayade C, Hilchie D, He H, Fang Y, Moons L, Carmeliet P, et al. Genetic deletion of placenta growth factor in mice alters uterine NK cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4267–4275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash GE, Schiessl B, Kirkley M, Innes BA, Cooper A, Searle RF, et al. Expression of angiogenic growth factors by uterine natural killer cells during early pregnancy. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:572–580. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, et al. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal–maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos G, Tirado-Gonzalez I, Freitag N, Kobelt P, Moschansky P, Klapp BF, et al. CXCR4+ dendritic cells promote angiogenesis during embryo implantation in mice. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:417–427. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheshtchin N, Gharagozloo M, Andalib A, Ghahiri A, Maracy MR, Rezaei A. The expression of Th1- and Th2-related chemokine receptors in women with recurrent miscarriage: the impact of lymphocyte immunotherapy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;64:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels JM, Linton NF, van den Heuvel MJ, Cnossen SA, Edwards AK, Croy BA, et al. Expression of chemokine decoy receptors and their ligands at the porcine maternal–fetal interface. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:304–313. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toldi G, Rigo JJ, Stenczer B, Vasarhelyi B, Molvarec A. Increased prevalence of IL-17-producing peripheral blood lymphocytes in pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szarka A, Rigo JJ, Lazar L, Beko G, Molvarec A. Circulating cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia determined by multiplex suspension array. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotsch F, Romero R, Friel L, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Erez O, et al. CXCL10/IP-10: a missing link between inflammation and anti-angiogenesis in preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:777–792. doi: 10.1080/14767050701483298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai M, Sasaki Y, Yoneda S, Kasahara T, Arai T, Okada M, et al. Elevated interleukin-8 in cervical mucus as an indicator for treatment to prevent premature birth and preterm, pre-labor rupture of membranes: a prospective study. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:220–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esplin MS, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Edwin S, Gomez R, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 is increased in the amniotic fluid of women who deliver preterm in the presence or absence of intra-amniotic infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17:365–373. doi: 10.1080/14767050500141329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce BD, Garvin SE, Grove J, Bonney EA, Dudley DJ, Schendel DE, et al. Serum macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the prediction of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappas M. Nuclear factor-kappaB mediates placental growth factor induced pro-labour mediators in human placenta. Mol Hum Reprod. 2012;18:354–361. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gas007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SA, Tower CL, Jones RL. Identification of chemokines associated with the recruitment of decidual leukocytes in human labour: potential novel targets for preterm labour. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua R, Pease JE, Sooranna SR, Viney JM, Nelson SM, Myatt L, et al. Stretch and inflammatory cytokines drive myometrial chemokine expression via NF-kappaB activation. Endocrinology. 2012;153:481–491. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson B, Holst RM, Andersson B, Hagberg H. Monocyte chemotactic protein-2 and -3 in amniotic fluid: relationship to microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity, intra-amniotic inflammation and preterm delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:566–571. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamitsi-Puchner A, Vrachnis N, Samoli E, Baka S, Iliodromiti Z, Puchner KP, et al. Possible early prediction of preterm birth by determination of novel proinflammatory factors in midtrimester amniotic fluid. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1092:440–449. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill N, Romero R, Gotsch F, Kusanovic JP, Edwin S, Erez O, et al. Exodus-1 (CCL20): evidence for the participation of this chemokine in spontaneous labor at term, preterm labor, and intrauterine infection. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:217–227. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervasi MT, Romero R, Bracalente G, Erez O, Dong Z, Hassan SS, et al. Midtrimester amniotic fluid concentrations of interleukin-6 and interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10: evidence for heterogeneity of intra-amniotic inflammation and associations with spontaneous early (<32 weeks) and late (>32 weeks) preterm delivery. J Perinat Med. 2012;40:329–343. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Wang H, Wang W, Zeng S, Zhong Y, Li DJ. Prevention of embryo loss in non-obese diabetic mice using adoptive ITGA2+ISG20+ natural killer-cell transfer. Reproduction. 2009;137:943–955. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raziel A, Schachter M, Strassburger D, Bern O, Ron-El R, Friedler S. Favorable influence of local injury to the endometrium in intracytoplasmic sperm injection patients with high-order implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Li R, Wang R, Huang HX, Zhong K. Local injury to the endometrium in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation cycles improves implantation rates. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1166–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Aldo PB, Barash A, Or, Schechtman YE, et al. Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2030–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]