Abstract

Background

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynaecologic malignancy. Despite progresses in chemotherapy and ultra-radical surgeries, this locally metastatic disease presents a high rate of local recurrence advocating for the role of a peritoneal niche. For several years, it was believed that tumor initiation, progression and metastasis were merely due to the changes in the neoplastic cell population and the adjacent non-neoplastic tissues were regarded as bystanders. The importance of the tumor microenvironment and its cellular component emerged from studies on the histopathological sequence of changes at the interface between putative tumor cells and the surrounding non-neoplastic tissues during carcinogenesis.

Method

In this review we aimed to describe the pro-tumoral crosstalk between ovarian cancer and mesenchymal stem cells. A PubMed search was performed for articles published pertaining to mesenchymal stem cells and specific to ovarian cancer.

Results

Mesenchymal stem cells participate to an elaborate crosstalk through direct and paracrine interaction with ovarian cancer cells. They play a role at different stages of the disease: survival and peritoneal infiltration at early stage, proliferation in distant sites, chemoresistance and recurrence at later stage.

Conclusion

The dialogue between ovarian and mesenchymal stem cells induces the constitution of a pro-tumoral mesencrine niche. Understanding the dynamics of such interaction in a clinical setting might propose new therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Ovarian cancer, Crosstalk, Phenotypic modulation, Dissemination, Chemoresistance

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic malignancy in developed countries, responsible for 5.8% of cancer related deaths [1]. The mainstay of treatment involves cytoreductive surgery associated with platinium and taxane-based chemotherapy [2]. Despite tremendous progresses in surgical practice and the broad range of chemotherapy or targeted therapy available, only low improvement has been achieved in survival outcomes these past 10 years [3-11]. Patients’ clinical course remains unpredictable, although most of them are optimally treated, with no residual disease after surgical debulking: 60% of women presenting with advanced-stage at baseline will recur within 5 years [12,13]. Therefore, 5-year overall survival remains low (around 45% including all stages) mainly due to peritoneal recurrences, suggesting the existence of occult sanctuaries where cancer cells are protected against treatment. Several authors have determined tumor autonomous parameters associated with treatment resistance [14,15]. Moreover, heterogeneity of ovarian cancers between and within subtypes has been illustrated by transcriptomic and genetic profiling [16]. Finally copy number variation analysis has revealed significant differences between matched primary ovarian tumor and peritoneal metastases [17]. Beyond these cell autonomous features, tumor environment may also contribute to the development of clinical relapse.

Tissues are comprised of different cell types that communicate to maintain homeostasis [18]. While architecture of normal tissue is lost in cancer, tumor cells maintain many interactions with surrounding non-malignant cells and extra-cellular matrix (ECM) to create a specific tumor contexture [19]. Both primary and metastatic lesions get infiltrated by diverse stromal cell types, including endothelial cells (ECs), immune cells, fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived cells such as macrophages, mast cells and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [20]. Stromal cells contribute to cancer growth and metastasis, through modulation of different pathways [21-27]. The interactions between cancer and stromal cells are thus primordial for tumor biology as the corresponding crosstalk induces phenotype changes resulting in stromal “activation” and tumor promotion in both primary and metastatic sites [28,29]. Therefore, the microenvironment plays a major role in cancer spread, beyond tumor cell autonomous mechanisms [30] and might have clinical consequences [31].

Understanding the mechanisms governing the relationship between cancer and stromal cells is thus essential to target tumor progression. Among the different peritoneal cells, MSCs are a cornerstone for cancer spread through their participation in the establishment of the pre-metastatic niche and the induction of metastatic and chemo-resistant phenotypes [21,22,25,32-34]. Here we review the complex role of mesenchymal cells in ovarian cancer progression and subsequently illustrate the constitution of a multi-parameter “mesencrine” niche.

Mesenchymal stem cells: a multipotent partner

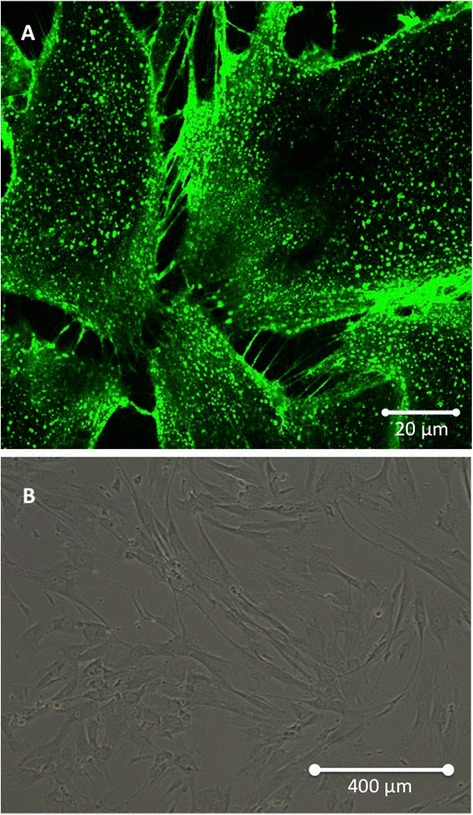

Although they were initially described in the bone marrow [35-38], MSCs may participate to the constitution of the blood vessel walls and thus be ubiquitous cells, belonging to virtually all organs [39-41]. As a subset of pericytes, they can potentially originate from a perivascular niche [42-46]. MSCs are adherent cells that have a fibroblastic morphology (Figure 1). They are capable of forming colonies (termed colony-forming unit fibroblastic) when selected by adhering to plastic surfaces [38]. Their identification is based on diverse surface markers, including CD105, CD73, CD90, CD166, CD44 and CD29.

Figure 1.

Morphological aspect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) cultivated in vitro. (A) Confocal microscopy showing intercellular interaction through Tunneling Nanotubes. (B) Optical microscopy illustrating the classical fibroblast-like shape of MSCs (×10).

MSCs play a major role in tissue homeostasis through the following characteristics: stemness, self-renewal and multipotence [47]. Their participation in tissue repair has been suggested by their capacity to differentiate in different cell types including osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes [38,48-50]. However, they usually do not differentiate into resident cell types of injured tissue as supported by the therapeutic value of their conditioned media [51]. Furthermore they exhibit low and transient engraftment in the damaged organs [52]. Their reparative function may thus operate through paracrine (“mesencrine”) factors [53].

MSCs also serve as niche cells for other cell types, by regulating regenerative processes. Indeed, they participate to both hematopoietic cells expansion and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) regulation [54-57]. In particular, they contribute to self-renewal and differentiation of HSCs through their regulation of the osteogenic niche [58-61].

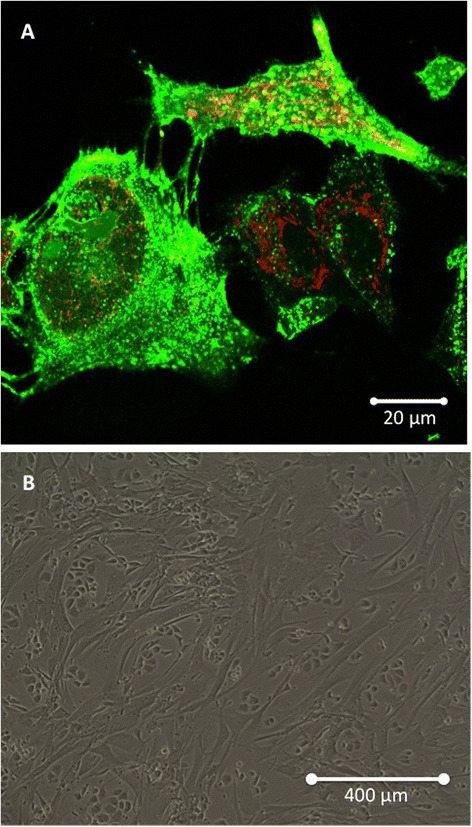

MSCs have a primordial role in immune tolerance [42,62]. Their immunosuppressive effect on T lymphocytes and dendritic cells may prevent self-responses in both physiological and pathological conditions [63,64]. In addition to their regenerative and immunomodulatory properties, MSCs contribute to tissue healing through many trophic abilities, such as: (i) inhibition of apoptosis and fibrosis; (ii) stimulation of angiogenesis; (iii) recruitment and regulation (proliferation and differentiation) of stem and progenitor cells; (iv) attenuation of oxidative stress [65]. Therefore, they display a wide range of functions, including cell regeneration, immunomodulation and stimulation of angiogenesis. Considering their diverse abilities, MSCs may thus constitute a key cell in the neoplastic niche, as supported by their incorporation into the stroma of solid tumors [66-68] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) co-cultivated in vitro with Ovarian Cancer Cells (OCCs). (A) Confocal microscopy: eGFP-MSCs (green) interact with PKH26-OCCs (red). (B) Optical microscopy showing how cancer and mesenchymal cells organize in vitro (×10).

MSCs engraftment into tumoral stroma leads to pro-tumoral crosstalk

Recruitment of cancer-associated MSCs

Bone marrow-derived MSCs are mobilized in blood circulation of patients presenting with advanced-stage ovarian cancer [34]. Interestingly, they normalize after complete cyto-reductive surgery. Such observation indicates a potential role for the interactions between ovarian cancer cells (OCCs) and MSCs during tumorigenesis.

Indeed, tumors act as unhealed wounds producing a continuous source of inflammatory mediators [69], resulting in the recruitment of other cell types, including MSCs [70-72]. Cancer cells hijack the cytokine machinery to acquire phenotypic advantages in proliferation [73], angiogenesis [74] and invasive and migratory properties [75-77]. The cytokine machinery is thus widely deregulated in advanced ovarian cancer, as supported by the amplification of many genes encoding cytokines in OCCs [17,78]. Such deregulation leads to bone marrow-derived and resident-tissue MSCs engraftment into tumor stroma through increased release of chemo-attractant soluble factors [79]. Many cytokines are involved in their recruitment, including IL-6, SDF1 (stroma derived factor 1), prostaglandine E2 (PGE2), PDGF and LL-37 (leucine, leucine-37) [21,80].

Educating MSCs to build a permissive tumoral environment

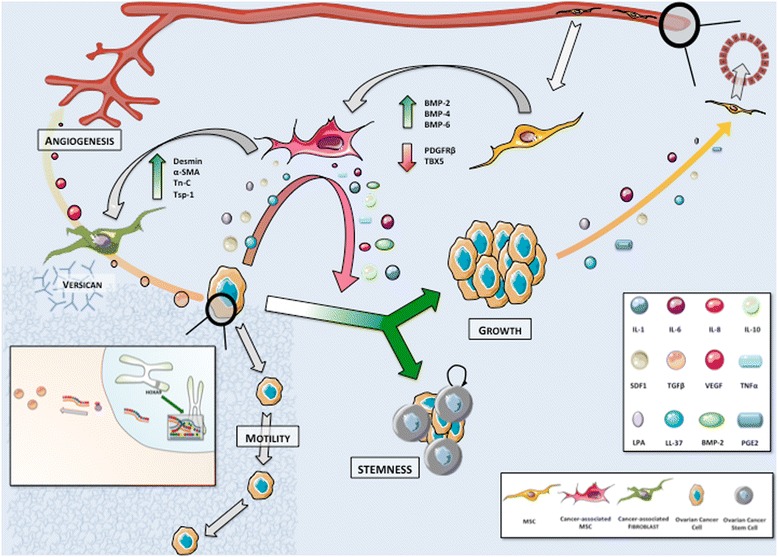

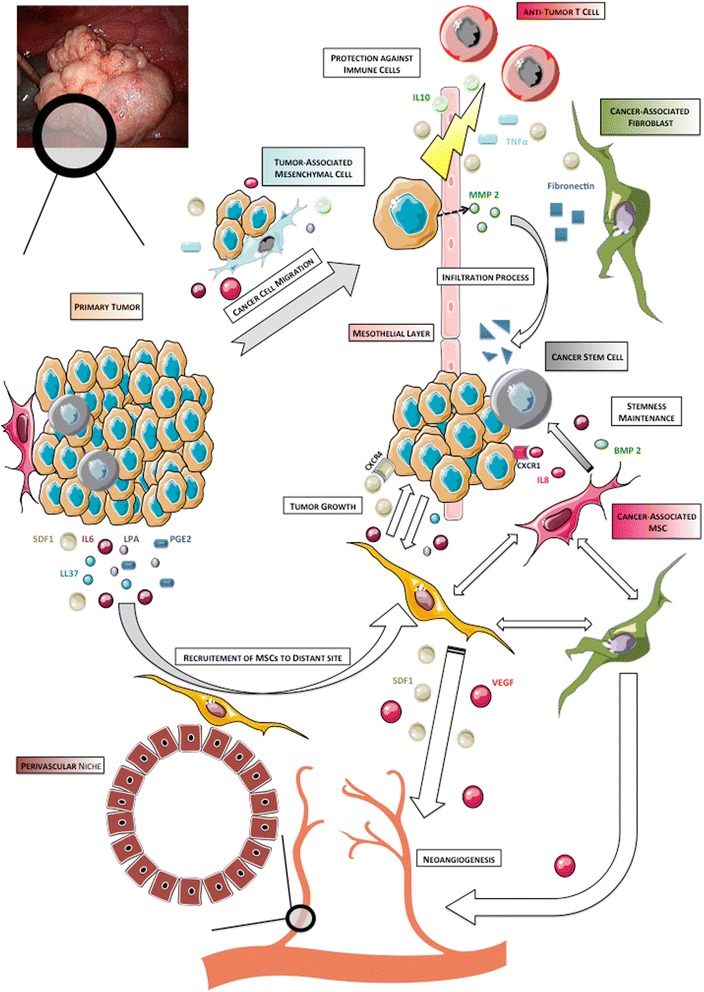

In ovarian cancer, the crosstalk between tumor and stromal cells leads to bilateral phenotype modulation. Indeed, besides OCCs phenotypic modifications, the phenotype of cancer-associated MSCs will evolve. Although it may differ from a cancer type to another, the shift in MSCs phenotype after their integration into tumor stroma mostly results in tumorigenesis promotion (Figure 3). For instance, breast cancer cells induce MSCs de novo CCL5 (RANTES) secretion which then acts as a paracrine mediator of increased motility, invasion and metastatic abilities of the tumor cells [68]. Once they engraft in ovarian neoplastic microenvironment, cancer-associated MSCs display an expression profile distinct from bone marrow MSCs, with an increased expression of BMP-2, BMP-4 and BMP-6, and a significant downregulation of PDGFRβ and TBX5 [81]. This pro-tumoral shift in phenotype is mediated, at least partially, by tumor-derived secreted factors.

Figure 3.

The cytokine-mediated crosstalk between Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and Ovarian Cancer Cells (OCCs) leads to a shift in MSCs phenotype resulting in tumorigenesis promotion. MSCs are recruited to tumor stroma from a peri-vascular niche. Their engraftment is associated with phenotypic modulations in response to tumor-derived secreted factors. Primed MSCs support tumor growth and self-renewal. Their differentiation in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) contributes to stromal modifications suitable for tumor expansion and stimulates angiogenesis. We highlight the role of HOXA9 expression that results in transcriptional activation of the gene encoding TGFβ2 inducing in turn CAFs expression VEGF.

LL-37 enhances MSCs secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and TNFα while diminishing the secretion of IL-12 [82], with a positive impact on tumor growth. MSCs exposed to LL-37 stimulate endothelial cell tubule formation in vitro suggesting concomitant increased production of pro-angiogenic molecules. They also migrate around endothelial structures and acquire a pericyte-like differentiation [82]. Lysophosphatidique acid (LPA) is a small bioactive phospholipid produced by OCCs that stimulates differentiation of MSCs in myofibroblast-like cells [83-85]. These activated fibroblasts, also termed cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), are a cornerstone in the establishment of tumor environment. MSCs incorporation into tumor stroma is thus associated with a morphological shift toward CAF-like phenotype, including expression of myofibroblast-like cell markers (α-SMA, desmin, VEGF), proteins involved in the regulation of ECM structure (Tn-C, Tsp-1, SL-1) and tumor promoting factors [22]. The underlying mechanism governing this differentiation process may also involve exosomes secreted by the tumor [86]. Interestingly, exosomes from different ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCAR-3 and SKOV-3) activate different MSCs signaling pathways (SMAD and AKT, respectively), suggesting that exosome content may vary according to cancer cell phenotype and thus modulate the tumor stroma differently. A genomic approach also correlates OCCs ability to induce CAFs features in MSCs with the expression of HOXA9, a Mullerian-patterning gene [87]. HOXA9 expression results in transcriptional activation of the gene encoding TGFβ2 that induces MSCs expression of IL-6, VEGF-A and SDF1. Schauer et al. have described a circuit whereby OCCs secrete IL-1β instructing a CAFs niche through p53 inhibition [31]. In return, the CAFs niche secretes IL-8, growth regulated oncogene-alpha (GRO-α), IL-6 and VEGF. Therefore, the modulation of MSCs phenotype contributes to generate a cytokine mediated inflammatory contexture suitable for tumor progression.

Once MSCs differentiate into CAFs they participate in the formation of fibrovascular networks within the tumor [22,88]. CAFs contribute to the perivascular matrix through the production of desmin and α-SMA [22]. CAFs secrete versican, a large ECM proteoglycan which production is up regulated by TGFβ via TGFβ-RII and SMAD signaling [89]. Up regulated versican then promotes OCCs motility. Their expression of the metalloprotease MMP-3 also participates in ECM regulation [22]. The resulting stromal modifications (increased vessel stability and matrix degradation) are compatible with tumor expansion, stimulated simultaneously by CAFs release of tumor-supportive growth factors, including HGF, EGF, IL-6 and SDF1 [88]. Ovarian tumors display increased expression of SDF1 in both CAFs and OCCs. SDF1 actively participates in the development of tumor environment and promotes tumor growth through complex mechanisms. First, it reduces local immunity and protects cancer cells by increased recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors resulting in poor anti-tumoral T cell activation through local overexpression of IL-10 and TNFα [90,91]. SDF1 also induces a dose-dependent proliferation of OCCs by its specific interaction with the receptor CXCR4, leading to transactivation of EGFR [92]. It participates as well in adhesion and trans-endothelial migration of cancer cells through MAP and Akt kinase regulation [93,94]. SDF1 promotes angiogenesis at tumor sites: hypoxia synchronously stimulates tumor SDF1 and VEGF production resulting in synergistic induction of angiogenesis [95]. SDF1 also acts as a chemo attractant for endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) CXCR4 + [96].

Noteworthy, direct intercellular interaction participates in phenotypic and environmental changes. Indeed, we have shown in a co-culture setting that MSCs triggered pro-metastatic properties in OCCs, including adherence, invasion and migration through the modification of cancer cells transcriptomic profile [32].

Induction of tumor plasticity: the cancer stem cell (CSC) theory

The CSC theory if clinically confirmed may represent be an extreme form of cancer cell phenotypic plasticity. CSCs are defined with the following criteria: (i) self renewal, (ii) reproducible tumor phenotype, (iii) restricted to a minority among entire cell population, (iv) differentiation into non-tumorigenic cells, (v) expression of distinct cell markers allowing their isolation [97-100]. CSCs have been identified in many solid cancers, including ovarian malignancies [101-109]. The identification of ovarian CSCs is based on CD117 (c-kit), CD44, CD133 and ALDH markers as well as PKH67/PKH26 dyes [99,102,110-112]. According to Silva et al., dual positivity of CD133 and ALDH defines an effective cell population of ovarian CSCs [111]. In limited dilution assays, a small number of these cells are sufficient to initiate tumors. Furthermore, they exhibit an increased angiogenic ability compared to regular OCCs. In the clinical setting, the presence of CSCs in ovarian tumors portends poor survival outcomes, leading to increased tumor burden and chemoresistance [113,114]. Their persistence within a residual niche may therefore contribute to disease recurrences.

We have recently reviewed the role of the microenvironment in ovarian CSCs maintenance [115]. Among the diverse stromal actors, cancer-associated MSCs are determinant for the regulation of CSCs self-renewal via increased expression of BMP-2 [81]. MacLean et al. reported a 4- to 8-fold increase in the percentage of ovarian CSCs in the presence of cancer-associated MSCs. Interestingly, tumor stemness was only partially blocked by the BMP inhibitor Noggin, suggesting the existence of other redundant pathways. MSCs-derived IL-6 and IL-8, whose production is stimulated by LPA, participate in CSCs promotion: IL-6 contributes to self-renewal of CSCs and IL-8 to CSCs proliferation through its binding to CXCR1 receptor [72,102,103,116,117].

Altogether MSCs engraftment at primary tumor site positively impacts cancer progression, due to the combination of several mechanisms including two-sided phenotypic modulation and promotion of OCCs proliferation and angiogenesis. MSCs also contribute to build a suitable environment that will participate in the regulation of ovarian cancer metastasis.

Metastatic niche: the concept of targeted spread

The “seed and soil” theory revisited

Based on autopsies of patients with breast cancer, Stephen Paget’s “seed and soil” theory illustrates the striking fact that a given tumor type will preferentially metastasize to specific organs [118]. This tumor tropism is clearly observed for certain cancers such as breast and prostate adenocarcinomas that commonly metastasize to bone tissue, or ovarian malignancies that typically spread into the peritoneal cavity. One century later, David Tarin reached a similar conclusion in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from diverse cancers including primary ovarian tumors [119]. While patients with peritoneo-venous shunts had millions of cancer cells poured in their blood circulation, they did not display more distant metastasis nor decreased survival compared to patients without shunts. Moreover, half of them did not develop any distant metastasis up to 27 months survival. Somehow, ovarian cancer is thus “programmed” to spread into selected organs and steer away from others. Besides the intrinsic abilities of cancer cells, tumor environment as well as resident stroma cells of distant sites participate in this targeted metastatic process.

The pre-metastatic niche

Lyden’s group has defined the concept of pre-metastatic niche as the early changes that occur in the future metastatic site before engraftment of cancer cells [79,120]. The constitution of such a niche dictates the pattern of metastatic spread. In brief, bone marrow-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) migrate to distant sites in response to growth factors and inflammatory cytokines secreted by the primary tumor. Kaplan et al. describe the existence of a complex loop where HPCs VEGFR1+ form cellular clusters in tumor-specific pre-metastatic sites before the arrival of cancer cells. Resident fibroblasts, possibly derived from MSCs and activated by tumor-specific growth factors, secrete fibronectin, an adhesion protein inducing VLA-4 (integrin α4β1) mediated recruitment of HPCs [29]. α4β1 signaling induces modifications of the local ECM mediated by MMP-9. The microenvironment alteration enhances recruitment of HPCs VEGFR1+, constituting in return a pre-metastatic contexture through a cytokine network including TNFα, MMP-9, TGFβ, and SDF1 [121]. SDF1 finally acts as a chemo-attractant for both hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs CXCR4+) and metastatic tumor cells (MTCs). In the hypoxia context, lysyl oxidase secreted by hypoxic tumor cells accumulates at pre-metastatic sites, resulting in CD11b + myeloid cell recruitment and increased production of MMP-2 [122]. MMP-2 favors tumor cells attachment through the changes they mediate in ECM [123]. MTCs subsequently engraft the permissive niche and contribute to the constitution of micro-metastases.

However, the stromal role during the metastatic process goes beyond the constitution of the pre-metastatic niche. Primary tumor stroma may also participate in selecting clones primed for metastasis in specific organs. In a triple negative breast cancer model, Zhang et al. have demonstrated that a tumor stroma rich in CAFs selects for cancer clones that fit to thrive on the CAF-derived cytokines SDF1 and IGF1 and sheds the carcinoma population toward a preponderance of such clones [124]. These clones display a constitutively high level of Src activity and bone metastatic ability contrary to most triple negative cancers that prominently metastasize to visceral organs. CAFs provide a cytokine contexture (SDF1 and IGF1) similar to bone marrow microenvironment and select metastatic seeds compatible with the target organ.

Altogether, data in the literature support the concept that the stroma actively participates in tumor promotion and to the constitution of a permissive niche for metastatic cells. It is thus a strong determinant of metastatic tropism. While different tumor types have their own physiopathology governing preferential sites for metastasis, ovarian cancer spread at an advanced stage (above IIIC) is limited to the peritoneum and distant blood-borne metastases are quite rare [125,126]. The recurrences are also often located within the abdominal cavity proposing the role of a residual niche within the peritoneum.

Initial dissemination within peritoneal cavity

Initial dissemination of OCCs from primary tumor is based on changes in expression of cellular adhesive proteins (Figure 4). Intercellular adhesion in ovarian tumors is mediated by N- and E-cadherin, and cell-matrix adhesion by integrins [127]. Disruption of both cell-cell contact and cell-matrix interactions results in the shedding of single cells or muticellular aggregates into peritoneal cavity. These ascitic OCCs undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition, resulting in a phenotype with low levels of E-cadherin and higher invasiveness and motility compared to primary tumor cells [128]. They also display CSCs characteristics when clustered in compact spheres, leading to increased chemoresistance and tumorigenesis [99]. They migrate to distant areas following the flow of peritoneal fluid hence the geographical localization of lesions within the abdomen at diagnosis. Ascites fluid comprises more than 200 proteins in its soluble fraction, including LPA, SDF1, cytokines such as RANTES, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10, growth factors (EGF, VEGF, HB-EGF, TGFβ, TNFα and CSF1) and ECM proteins such as collagens I and III [129-136]. It thus constitutes a suitable environment for OCCs survival.

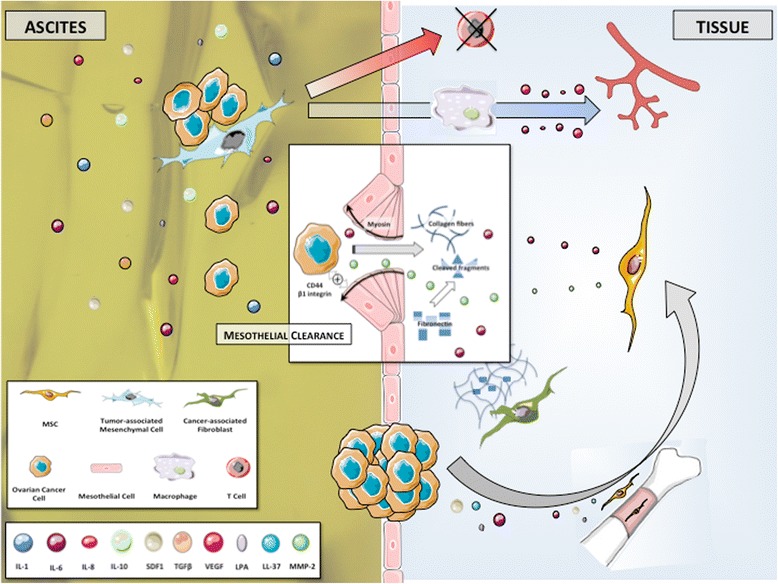

Figure 4.

Early steps in peritoneal infiltration. Tumor-associated Mesenchymal Cells (TAMCs) constitute a protective niche for ascitic Ovarian Cancer Cells (OCCs) through their inhibition of anti-cancer T cells. They also participate in angiogenesis at metastatic sites by inducing macrophages production of pro-angiogenic cytokines including IL-6, IL-8 and VEGF. Ascitic OCCs may be the primary source of peritoneal metastases. The initiation of peritoneal invasion relies on the ability of OCCs to attach to and to clear the mesothelial cells that constitute the peritoneum. This mesothelial clearance involves integrin- and talin-dependent activation of myosin and allows OCCs to get access to the basement membrane. Bone marrow-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) are recruited at metastatic sites and favor the infiltration process with the release of secreted factors such as IL-6 and MMP-2. The metalloprotease MMP-2 is also up regulated in OCCs upon binding to mesothelium and leads to improved attachment of tumor cells by modifying the extracellular matrix.

Cellular components including inflammatory and mesothelial cells are also prevalent in ascites. We have isolated stromal cells from ascites of patients presenting with ovarian cancer [137]. These tumor associated mesenchymal cells (TAMCs) were closely associated with tumor cells (photo) and shared some homology with bone marrow- and adipose- derived MSCs (CD9, CD10, CD29, CD146, CD166, HLA-1) [24]. They might therefore represent a differentiated stromal subset of MSCs. Converging data support that TAMCs actively contribute to metastatic process through different mechanisms. We have shown that intra-peritoneal co-injection of TAMCs and OCCs conferred a proliferative advantage to OCCs in a murine model with enhanced tumor growth and development of neoplastic ascites [24]. Noteworthy, TAMCs were preferentially localised close to cancer cells, typically in the periphery of tumors. Moreover, the presence of TAMCs was associated with increased tumor vascularization. Concordantly, HIF-1α and VEGF-A were overexpressed in tumors and ascites, respectively, derived from the group that received co-injection. Castells et al. failed to demonstrate any proliferative effect of TAMCs on ECs [138]. Nevertheless they have shown the existence of a crosstalk between TAMCs and macrophages yielding increased production of pro-angiogenic cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8 and VEGF.

TAMCs also display a protective role by inducing chemoresistance and immunomodulation [23,137,139]. TAMCs inhibit both proliferation and cytokine production in human CD4 and CD8 T-cells, allowing cancer cells to evade immune surveillance. Therefore, the protection TAMCs provide prompts us to consider them as a niche where tumor cells are sheltered against therapy.

Cancer dissemination in ovarian malignancies may be sequential, from the primary tumor to abdominal “milieu” and then to the peritoneum. Indeed, ascitic OCCs might be the primary source of intraperitoneal metastatic lesions. Their attachment to the peritoneum constitutes the first step toward peritoneal infiltration.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis

Peritoneal involvement

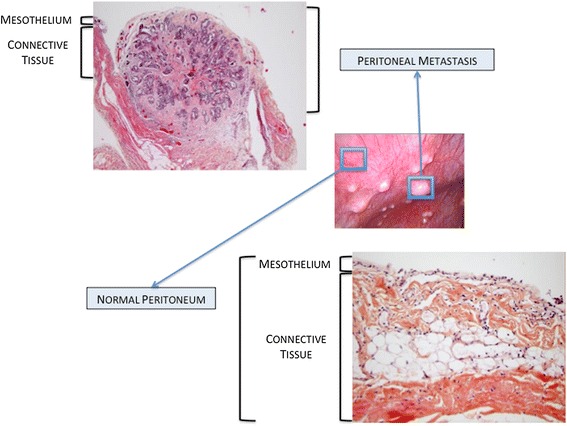

Clinical presentation at baseline in patients with advanced stages includes ascites, peritoneal carcinomatosis and omental involvement [140] (Figure 4). The peritoneum is a complex organ constituting the microenvironment of ovarian cancer metastatic nodules (Figure 5). It is composed of a continuous mesothelial cell layer covering all abdominal organs except ovaries. The peritoneum lies on a basement membrane covering stromal tissue. This stroma contains a collagen-based matrix (collagen types I and III), blood and lymphatic vessels, nerve fibers and fibroblastic-like cells (Figure 6). The peritoneum is considered as a tertiary lymphoid organ that allows fast mobilization and recruitment of the inflammatory machinery to overcome abdominal injury or infection. Hence many inflammatory cytokines are up regulated in ovarian cancer ascites. Mesothelial cells also contribute to peritoneal fluid dialysis, abdominal healing and formation of adherences [141,142]. Therefore, the peritoneum constitutes a functional and anatomical barrier against intra-abdominal aggression and is considered as the first line of defense against cancer spread [143,144].

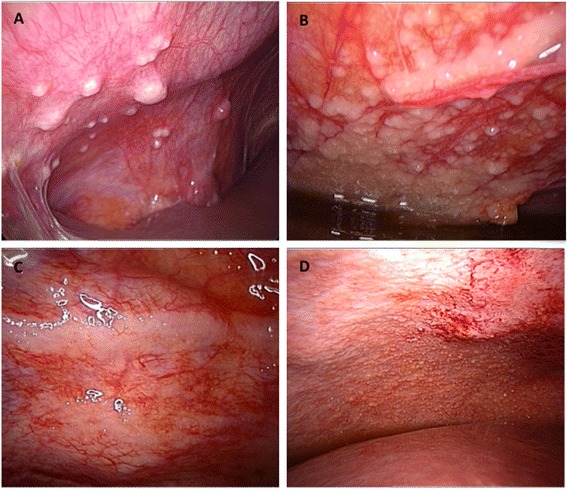

Figure 5.

Macroscopic aspects of peritoneal carcinomatosis. (A) Isolated lesions. (B) Confluent lesions. (C) Typical “taches de bougie” lesions. (D) Miliary lesions.

Figure 6.

Pathological aspects of normal peritoneum and peritoneal metastasis.

However the metastatic process manages to disrupt the organisation of the mesothelial layer: during the formation of carcinomatosis nodules, mesothelial cells aggregate around the neoplastic lesion [145]. The mechanism used by OCCs to clear mesothelial cells and get access to the basement membrane is complex and yet poorly understood. Tumoral soluble factors may prime mesothelial tissue for cancer spread. Indeed, mesothelium in ovarian carcinomatosis displays morphological changes and forms a discontinuous layer of hemispheric cells [146]. This phenotypic alteration is associated with modifications in transcriptomic profile, including modulation of genes involved in inflammation, catalytic activity, cellular adhesion and ECM constitution [147]. Analysis of surgical specimens has suggested that mesothelial cells may nurture peritoneal metastases through the production of growth factors such as VEGF and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) [148]. The initiation of peritoneal invasion also relies on the ability of OCCs to attach to mesothelial cells through activation of CD44 and beta-1 integrin [149,150]. In their in vitro model, Iwanicki et al. have shown that ovarian cancer spheroids use integrin- and talin-dependent activation of myosin and traction force to promote displacement of mesothelial cells [151]. This mesothelial clearance permits OCCs to get access to the basement membrane and to stromal cells that will then support their survival and growth. MSCs play an important role along this process, as supported by our 3D model of early peritoneal infiltration based on amniochorionic membrane [33]. In serum free condition, OCCs became adherent to the membrane within the first 24 hours following incubation and started to infiltrate the stroma 48 hours after adhesion. Infiltration was significantly deeper in areas settled with MSCs, due to increased release of IL-6. Therefore, MSCs generate a cytokine contexture suitable for metastasis establishment. Metalloproteases such as MMP-2 contribute through a feed-forward loop to cancer cells peritoneal adhesion and invasion. MMP-2 expression is up regulated in OCCs upon binding to mesothelium, through direct cell-cell interaction involving mesothelial cells [123]. MMP-2 is also produced by bone marrow-derived MSCs recruited to the tumor site in response to OCCs secretion of LL-37 [21]. MMP-2 over-expression leads to increased degradation of ECM proteins such as vibronectin and fibronectin. OCCs adhere more efficiently to cleaved fragments, resulting in improved attachment. Noteworthy, vibronectin and fibronectin production is increased during the metastatic process. Resident fibroblasts, potentially deriving from resident MSCs, are primed by tumor specific growth factors and and constitute the main source of ECM proteins [29].

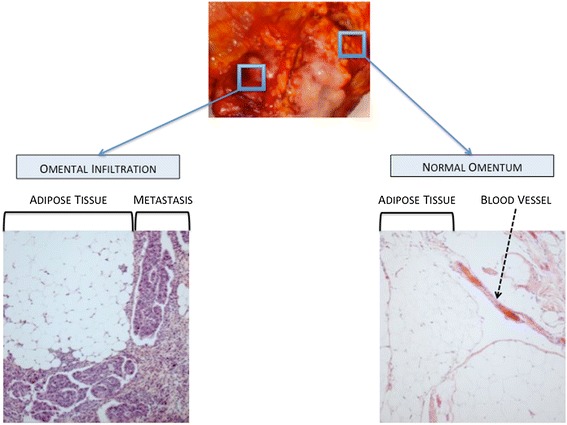

Omental infiltration

The omentum is a large fold of visceral peritoneum containing fatty tissue. In a 3D culture model of omental infiltration, Kenny et al. have demonstrated that OCCs preferentially adhere to and invade through collagen I and IV rather than fibronectin, vitronectin and laminin [143]. Furthermore, resident cells differently impact the metastatic process. While mesothelial cells inhibit both adhesion and invasion, omental fibroblasts promote OCCs attachment and infiltration. Similarly to peritoneal infiltration, MMP-2 over-expression observed upon the interaction between OCCs and omental fibroblasts may promote tumoral infiltration [123]. Omental MSCs (O-ASCs) also participate in the invasion process [152]. In a model of endometrial carcinoma, O-ASCs stimulated cancer cells proliferation and promoted in vivo tumor growth and vascularization [152]. Compared to the control group, the tumors associated with O-ASCs contained a more mature and extensive fibrovascular network. These findings can be extrapolated to the omental invasion occurring in ovarian cancer (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Pathological aspects of normal omentum and omental metastasis.

MSCs and chemoresistance

Microenvironement mediates resistance to therapy

The mainstay of treatment for ovarian cancer involves complete cyto-reductive surgery associated with platinium and taxane-based chemotherapy [153]. However, most patients achieving complete initial clinical remission will develop recurrences and resistance to first line drugs [154-156]. Acquired chemoresistance involves many mechanisms: (i) alteration of the lipid membrane modifying drug penetrance; (ii) increased capacity in DNA repair; (iii) modification of drug targets; (iv) drug inactivation mediated by metallothionein- or glutathione-dependent mechanisms; (v) loss of drug surface transporter; (vi) drug clearance by efflux pump [137]. Such resistance mechanisms consist in long-term processes and usually arise after multiple courses of chemotherapy [155,157]. They develop over time as a result of sequential genetic changes that ultimately culminate in some complex therapy-resistant phenotypes.

However, acquired chemoresistance cannot explain most of treatment failures in ovarian cancer. The majority of recurrences will occur within the first two years following completion of initial treatment. Primary resistance to treatment only concerns a low subgroup of early relapses (up to 6 months after initial treatment). Other diseases are considered platinium-sensitive. Therefore, in addition to casual mechanisms of acquired resistance, the microenvironment might mediate a kind of de novo drug resistance leading to the persistence of a hidden residual disease responsible for a subsequent relapse.

First evidences were provided in 1990 by Teicher et al. [158]. In a murine breast cancer model, long-term exposure to treatment was responsible for chemoresistance in tumor-bearing animals. Nevertheless, in spite of high levels of in vivo resistance, no significant resistance was observed when cancer cells were exposed to the same drugs in vitro. These findings set up the stage for the paradigm that drug resistance can develop through mechanisms that are expressed only in vivo and may involve the crosstalk between cancer and stromal cells. Somehow the microenvironment could protect the tumor cells from the effects of anticancer agents.

The cross talk between cancer and stromal cells is responsible for changes in ECM and cytokines release. Reciprocal integrin- and soluble factor-mediated interaction induces in cancer cells a transient drug resistant phenotype leading to persistence of surviving cells [157]. Over time, genetic instability inherent to tumor cells combined with selective pressure of therapy will result in successive and random genetic changes. Such modifications will cause the gradual development of more complex and permanent acquired-resistance phenotypes, and relapses may originate from these persistent cancer cells.

MSCs actively contribute to environment-mediated resistance

The microenvironment provides a transient protection while OCCs are acquiring genetic changes. Oncologic trogocytosis perfectly illustrates this mechanism: through a membrane uptake, cancer cells can get new functionalities. We have observed such hetero-cellular interaction between TAMCs and OCCs [137]. Trogocytosis allowed OCCs to acquire functional multidrug resistance proteins from TAMCs membrane, including P-gp and LRP. Such mechanisms have been described in other tumors as well [159,160].

MSCs are responsible for phenotypic modulation toward more aggressive cancer cell clones. We have proposed a transcriptomic approach in OCCs co-cultured with MSCs [32]. The analysis revealed that 3 biological-function gene clusters were enriched in OCCs upon contact with MSCs, comprising metastatic, proliferative and chemoresistance abilities. Concordantly, OCCs co-cultured with MSCs displayed chemoresistance to taxol and carboplatin. MSCs-derived secreted factors are also able to confer chemoresistance to platinium in OCCs, as supported by the decrease of carboplatin-induced apoptosis in the presence of MSCs condition medium [139]. This apoptosis blockade is mediated by the activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and the phosphorylation of its downstream regulator X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP).

Microenvironment protection may have contributed to the disappointing results of hyperthermic intraoperative chemotherapy (HIPEC) for stage IIIC ovarian cancers [161,162]. HIPEC procedure involves a complete resection of abdominal disease followed by intra peritoneal infusion of Oxaliplatin at 42-44°C. We have demonstrated that hyperthermia did not challenge survival of bone marrow-derived and cancer-associated MSCs [25]. Furthermore, in the context of hyperthermia, MSCs induced a thermo tolerance in OCCs through SDF1 secretion. The inhibition of SDF1/CXCR4 interaction restored cytotoxicity of hyperthermia.

Circulating MSCs, observed in advanced-stage ovarian malignancies, are also involved in chemoresistance. They are activated by platinium-derived drugs and in turn secrete fatty acids (PIFAs) that, in discrete quantities, confer OCCs resistance to several types of anti-cancer agents [34]. PIFAs induce acute and reversible prevention of apoptosis in cancer cells through an indirect and yet undetermined effect that can be prevented by concomitant infusion of cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitor.

MSCs widely participate in drug resistance in ovarian cancer through many mechanisms. Anti-tumor therapy should thus be associated to additional therapies targeting tumor-stroma interactions. Such therapeutic combination would prevent from temporary microenvironment-mediated drug resistance and might suppress any minimal residual disease. In the era of personalized medicine, it represents one of the biggest challenges for further therapeutic approaches in ovarian cancer.

Conclusion

Tumor stroma and microenvironment represent a cornerstone in the regulation of OCCs behavior (Figure 8). MSCs contribute to each step of cancer spread, from proliferation to chemoresistance, from infiltration to metastasis. The crosstalk between MSCs and OCCs is based on complex mechanisms, involving cell-cell interaction and secreted factors. Beyond casual phenotypic changes they generate in tumor cells, MSCs provide a smart environment-mediated resistance protecting residual disease from treatment while acquired mechanisms are developing. OCCs and MSCs clearly constitute a deadly cocktail, offering the disease a multi-potent partner. Therefore, to enhance suppression of any residual disease, future therapeutic approaches should thus combine anti-tumor therapy to new molecules targeting tumor-stroma interactions.

Figure 8.

Overview of the role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells along tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge everyone who contributed to this work: Jessica Hoarau, Mahatb Maleki, Nadine Abu-Kaoud, Renuka Gupta.

Abbreviations

- ECM

Extra-cellulra matrix

- EC

Endothelial cell

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cell

- HSC

Hematopoietic stem cell

- OCC

Ovarian cancer cell

- CAF

Cancer associated fibroblast

- EPC

Endothelial progenitor cell

- CSC

Cancer stem cell

- HPC

Hematopoietic progenitor cell

- MTC

Metastatic tumor cell

- TAMC

Tumor associated mesenchymal cell

- HIPEC

Hyperthermic intraoperative chemotherapy

Footnotes

Cyril Touboul, and Fabien Vidal, are contributed equally to this work.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

CT carried out manuscript writing and reviewing, and perfomed bibliographic search. FV carried out manuscript writing and reviewing and figures conception. JP carried out manuscript reviewing and figures conception. RL carried out manuscript reviewing and participated to bibliographic search. AR carried out manuscript writing and reviewing, figures conception and participated to bibliographic search. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Cyril Touboul, Email: cyril.touboul@gmail.com.

Fabien Vidal, Email: dox_94@yahoo.fr.

Jennifer Pasquier, Email: jep2026@qatar-med.cornell.edu.

Raphael Lis, Email: ral2020@med.cornell.edu.

Arash Rafii, Email: ral2020@med.cornell.edu.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leminen A, Auranen A, Butzow R, Hietanen S, Komulainen M, Kuoppala T, Maenpaa J, Puistola U, Vuento M, Vuorela P, Yliskoski M. Update on current care guidelines: ovarian cancer. Duodeciml. 2012;128:1300–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stehman FB, Brady MF, Thigpen JT, Rossi EC, Burger RA. Cytokine use and survival in the first-line treatment of ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(3):495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mobus V, Wandt H, Frickhofen N, Bengala C, Champion K, Kimmig R, Ostermann H, Hinke A, Ledermann JA. Phase III trial of high-dose sequential chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell support compared with standard dose chemotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer: intergroup trial of the AGO-Ovar/AIO and EBMT. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4187–4193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bookman MA, Darcy KM, Clarke-Pearson D, Boothby RA, Horowitz IR. Evaluation of monoclonal humanized anti-HER2 antibody, trastuzumab, in patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma with overexpression of HER2: a phase II trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:283–290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noguera IR, Sun CC, Broaddus RR, Branham D, Levenback CF, Ramirez PT, Sood AK, Coleman RL, Gershenson DM. Phase II trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with recurrent platinum- and taxane-resistant low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary, peritoneum, or fallopian tube. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombo N, Kutarska E, Dimopoulos M, Bae DS, Rzepka-Gorska I, Bidzinski M, Scambia G, Engelholm SA, Joly F, Weber D, El-Hashimy M, Li J, Souami F, Wing P, Engelholm S, Bamias A, Schwartz P. Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing patupilone (EPO906) with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in platinum-refractory or -resistant patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3841–3847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, Mannel RS, Homesley HD, Fowler J, Greer BE, Boente M, Birrer MJ, Liang SX. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kristensen G, Carey MS, Beale P, Cervantes A, Kurzeder C, du Bois A, Sehouli J, Kimmig R, Stahle A, Collinson F, Essapen S, Gourley C, Lortholary A, Selle F, Mirza MR, Leminen A, Plante M, Stark D, Qian W, Parmar MK, Oza AM. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2484–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott C, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T, Matei D, Macpherson E, Watkins C, Carmichael J, Matulonis U. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaaback K, Johnson N, Lawrie TA. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the initial management of primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD005340. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005340.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poveda Velasco A, Casado Herraez A, Cervantes Ruiperez A, Gallardo Rincon D, Garcia Garcia E, Gonzalez Martin A, Lopez Garcia G, Mendiola Fernandez C, Ojeda Gonzalez B. Treatment guidelines in ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:308–316. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke TW, Morris M. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1994;21:167–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers ER, Havrilesky LJ, Kulasingam SL, Sanders GD, Cline KE, Gray RN, Berchuck A, McCrory DC. Genomic tests for ovarian cancer detection and management. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2006;145:1–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ᅟ Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farley J, Ozbun LL, Birrer MJ. Genomic analysis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell Res. 2008;18:538–548. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malek JA, Mery E, Mahmoud YA, Al-Azwani EK, Roger L, Huang R, Jouve E, Lis R, Thiery JP, Querleu D, Rafii A. Copy number variation analysis of matched ovarian primary tumors and peritoneal metastasis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Udagawa T, Wood M. Tumor-stromal cell interactions and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor stroma and regulation of cancer development. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:119–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coffelt SB, Marini FC, Watson K, Zwezdaryk KJ, Dembinski JL, LaMarca HL, Tomchuck SL, Honer zu Bentrup K, Danka ES, Henkle SL, Scandurro AB. The pro-inflammatory peptide LL-37 promotes ovarian tumor progression through recruitment of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3806–3811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900244106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spaeth EL, Dembinski JL, Sasser AK, Watson K, Klopp A, Hall B, Andreeff M, Marini F. Mesenchymal stem cell transition to tumor-associated fibroblasts contributes to fibrovascular network expansion and tumor progression. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinet L, Poupot R, Mirshahi P, Rafii A, Fournie JJ, Mirshahi M, Poupot M. Hospicells derived from ovarian cancer stroma inhibit T-cell immune responses. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2143–2152. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasquet M, Golzio M, Mery E, Rafii A, Benabbou N, Mirshahi P, Hennebelle I, Bourin P, Allal B, Teissie J, Mirshahi M, Couderc B. Hospicells (ascites-derived stromal cells) promote tumorigenicity and angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2090–2101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lis R, Touboul C, Mirshahi P, Ali F, Mathew S, Nolan DJ, Maleki M, Abdalla SA, Raynaud CM, Querleu D, Al-Azwani E, Malek J, Mirshahi M, Rafii A. Tumor associated mesenchymal stem cells protects ovarian cancer cells from hyperthermia through CXCL12. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:715–725. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.St Hill CA. Interactions between endothelial selectins and cancer cells regulate metastasis. Front Biosci. 2012;17:3233–3251. doi: 10.2741/3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mierke CT. Role of the endothelium during tumor cell metastasis: is the endothelium a barrier or a promoter for cell invasion and metastasis? J Biophys. 2008;2008:183516. doi: 10.1155/2008/183516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cirri P, Chiarugi P. Cancer-associated-fibroblasts and tumour cells: a diabolic liaison driving cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, Zhu Z, Hicklin D, Wu Y, Port JL, Altorki N, Port ER, Ruggero D, Shmelkov SV, Jensen KK, Rafii S, Lyden D. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schauer IG, Zhang J, Xing Z, Guo X, Mercado-Uribe I, Sood AK, Huang P, Liu J. Interleukin-1beta promotes ovarian tumorigenesis through a p53/NF-kappaB-mediated inflammatory response in stromal fibroblasts. Neoplasia. 2013;15:409–420. doi: 10.1593/neo.121228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lis R, Touboul C, Raynaud CM, Malek JA, Suhre K, Mirshahi M, Rafii A. Mesenchymal cell interaction with ovarian cancer cells triggers pro-metastatic properties. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Touboul C, Lis R, Al Farsi H, Raynaud CM, Warfa M, Althawadi H, Mery E, Mirshahi M, Rafii A. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance ovarian cancer cell infiltration through IL6 secretion in an amniochorionic membrane based 3D model. J Transl Med. 2013;11:28. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roodhart JML, Daenen LGM, Stigter ECA, Prins H-J, Gerrits J, Houthuijzen JM, Gerritsen MG, Schipper HS, Backer MJG, van Amersfoort M, Vermaat JSP, Moerer P, Ishihara K, Kalkhoven E, Beijnen JH, Derksen PWB, Medema RH, Martens AC, Brenkman AB, Voest EE. Mesenchymal stem cells induce resistance to chemotherapy through the release of platinum-induced fatty acids. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavassoli M, Crosby WH. Transplantation of marrow to extramedullary sites. Science. 1968;161:54–56. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3836.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, Panasuk AF, Rudakowa SF, Luriá EA, Ruadkow IA. Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method. Exp Hematol. 1974;2:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedenstein A. Osteogenic stem cells in bone marrow. In: Heersche J, Kanis J, editors. Bone and Mineral Research. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1990. pp. 243–272. [Google Scholar]

- 39.da Silva Meirelles L, Sand TT, Harman RJ, Lennon DP, Caplan AI. MSC frequency correlates with blood vessel density in equine adipose tissue. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:221–229. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernardo ME, Locatelli F, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1176:101–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raynaud CM, Maleki M, Lis R, Ahmed B, Al-Azwani I, Malek J, Safadi FF, Rafii A. Comprehensive characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from human placenta and fetal membrane and their response to osteoactivin stimulation. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:658356. doi: 10.1155/2012/658356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.da Silva Meirelles L, Caplan AI, Nardi NB. In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2287–2299. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, Chen CW, Corselli M, Park TS, Andriolo G, Sun B, Zheng B, Zhang L, Norotte C, Teng PN, Traas J, Schugar R, Deasy BM, Badylak S, Buhring HJ, Giacobino JP, Lazzari L, Huard J, Peault B. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Differential expression of alpha-actin mRNA and immunoreactive protein in brain microvascular pericytes and smooth muscle cells. J Neurosci Res. 1994;39:430–435. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97:512–523. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Betsholtz C, Lindblom P, Gerhardt H. Role of pericytes in vascular morphogenesis. EXS. 2005;94:115–125. doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7311-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bianco P, Robey PG, Simmons PJ. Mesenchymal stem cells: revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caplan AI. The mesengenic process. Clin Plast Surg. 1994;21:429–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Lee CW, Barr S, Fuchs S, Epstein SE. Marrow-derived stromal cells express genes encoding a broad spectrum of arteriogenic cytokines and promote in vitro and in vivo arteriogenesis through paracrine mechanisms. Circ Res. 2004;94:678–685. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000118601.37875.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iso Y, Spees JL, Serrano C, Bakondi B, Pochampally R, Song YH, Sobel BE, Delafontaine P, Prockop DJ. Multipotent human stromal cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction in mice without long-term engraftment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valle-Prieto A, Conget PA. Human mesenchymal stem cells efficiently manage oxidative stress. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1885–1893. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krosl J, Austin P, Beslu N, Kroon E, Humphries RK, Sauvageau G. In vitro expansion of hematopoietic stem cells by recombinant TAT-HOXB4 protein. Nat Med. 2003;9:1428–1432. doi: 10.1038/nm951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang CC, Kaba M, Ge G, Xie K, Tong W, Hug C, Lodish HF. Angiopoietin-like proteins stimulate ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:240–245. doi: 10.1038/nm1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, Yates JR, 3rd, Nusse R. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butler JM, Nolan DJ, Vertes EL, Varnum-Finney B, Kobayashi H, Hooper AT, Seandel M, Shido K, White IA, Kobayashi M, Witte L, May C, Shawber C, Kimura Y, Kitajewski J, Rosenwaks Z, Bernstein ID, Rafii S. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, Sato H, Matsuoka S, Takubo K, Ito K, Koh GY, Suda T. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, Huang H, He X, Tong WG, Ross J, Haug J, Johnson T, Feng JQ, Harris S, Wiedemann LM, Mishina Y, Li L. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kollet O, Dar A, Shivtiel S, Kalinkovich A, Lapid K, Sztainberg Y, Tesio M, Samstein RM, Goichberg P, Spiegel A, Elson A, Lapidot T. Osteoclasts degrade endosteal components and promote mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:657–664. doi: 10.1038/nm1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raimondi G, Turnquist HR, Thomson AW. Frontiers of immunological tolerance. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;380:1–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-395-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuo YR, Chen CC, Goto S, Lin PY, Wei FC, Chen CL. Mesenchymal stem cells as immunomodulators in a vascularized composite allotransplantation. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:854846. doi: 10.1155/2012/854846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le Blanc K, Ringden O. Immunomodulation by mesenchymal stem cells and clinical experience. J Intern Med. 2007;262:509–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strioga M, Viswanathan S, Darinskas A, Slaby O, Michalek J. Same or not the same? Comparison of adipose tissue-derived versus bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem and stromal cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2724–2752. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Studeny M, Marini FC, Dembinski JL, Zompetta C, Cabreira-Hansen M, Bekele BN, Champlin RE, Andreeff M. Mesenchymal stem cells: potential precursors for tumor stroma and targeted-delivery vehicles for anticancer agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1593–1603. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klopp AH, Spaeth EL, Dembinski JL, Woodward WA, Munshi A, Meyn RE, Cox JD, Andreeff M, Marini FC. Tumor irradiation increases the recruitment of circulating mesenchymal stem cells into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11687–11695. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, Richardson AL, Polyak K, Tubo R, Weinberg RA. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vicari AP, Caux C. Chemokines in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:143–154. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ginestier C, Charafe-Jauffret E, Birnbaum D. Breast tumor microenvironment: in the eye of the cytokine storm. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(15):2420–2421. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luboshits G, Shina S, Kaplan O, Engelberg S, Nass D, Lifshitz-Mercer B, Chaitchik S, Keydar I, Ben-Baruch A. Elevated expression of the CC chemokine regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) in advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4681–4687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Belperio JA, Keane MP, Arenberg DA, Addison CL, Ehlert JE, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vicari AP, Ait-Yahia S, Chemin K, Mueller A, Zlotnik A, Caux C. Antitumor effects of the mouse chemokine 6Ckine/SLC through angiostatic and immunological mechanisms. J Immunol. 2000;165:1992–2000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, Barrera JL, Mohar A, Verastegui E, Zlotnik A. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mashino K, Sadanaga N, Yamaguchi H, Tanaka F, Ohta M, Shibuta K, Inoue H, Mori M. Expression of chemokine receptor CCR7 is associated with lymph node metastasis of gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2937–2941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Malek JA, Martinez A, Mery E, Ferron G, Huang R, Raynaud C, Jouve E, Thiery JP, Querleu D, Rafii A. Gene expression analysis of matched ovarian primary tumors and peritoneal metastasis. J Transl Med. 2012;10:121. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wels J, Kaplan RN, Rafii S, Lyden D. Migratory neighbors and distant invaders: tumor-associated niche cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:559–574. doi: 10.1101/gad.1636908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abramsson A, Lindblom P, Betsholtz C. Endothelial and nonendothelial sources of PDGF-B regulate pericyte recruitment and influence vascular pattern formation in tumors. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1142–1151. doi: 10.1172/JCI200318549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McLean K, Gong Y, Choi Y, Deng N, Yang K, Bai S, Cabrera L, Keller E, McCauley L, Cho KR, Buckanovich RJ. Human ovarian carcinoma-associated mesenchymal stem cells regulate cancer stem cells and tumorigenesis via altered BMP production. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3206–3219. doi: 10.1172/JCI45273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tomchuck SL, Zwezdaryk KJ, Coffelt SB, Waterman RS, Danka ES, Scandurro AB. Toll-like receptors on human mesenchymal stem cells drive their migration and immunomodulating responses. Stem Cells. 2008;26:99–107. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cai H, Xu Y. The role of LPA and YAP signaling in long-term migration of human ovarian cancer cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11:31. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jeon ES, Moon HJ, Lee MJ, Song HY, Kim YM, Cho M, Suh D-S, Yoon M-S, Chang CL, Jung JS, Kim JH. Cancer-derived lysophosphatidic acid stimulates differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells to myofibroblast-like cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:789–797. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Direkze NC, Hodivala-Dilke K, Jeffery R, Hunt T, Poulsom R, Oukrif D, Alison MR, Wright NA. Bone marrow contribution to tumor-associated myofibroblasts and fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8492–8495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cho JA, Park H, Lim EH, Kim KH, Choi JS, Lee JH, Shin JW, Lee KW. Exosomes from ovarian cancer cells induce adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells to acquire the physical and functional characteristics of tumor-supporting myofibroblasts. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ko SY, Barengo N, Ladanyi A, Lee JS, Marini F, Lengyel E, Naora H. HOXA9 promotes ovarian cancer growth by stimulating cancer-associated fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3603–3617. doi: 10.1172/JCI62229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hall B, Dembinski J, Sasser AK, Studeny M, Andreeff M, Marini F. Mesenchymal stem cells in cancer: tumor-associated fibroblasts and cell-based delivery vehicles. Int J Hematol. 2007;86:8–16. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yeung TL, Leung CS, Wong KK, Samimi G, Thompson MS, Liu J, Zaid TM, Ghosh S, Birrer MJ, Mok SC. TGF-beta modulates ovarian cancer invasion by upregulating CAF-derived versican in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5016–5028. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zou W, Machelon V, Coulomb-L'Hermin A, Borvak J, Nome F, Isaeva T, Wei S, Krzysiek R, Durand-Gasselin I, Gordon A, Pustilnik T, Curiel DT, Galanaud P, Capron F, Emilie D, Curiel TJ. Stromal-derived factor-1 in human tumors recruits and alters the function of plasmacytoid precursor dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1339–1346. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scotton CJ, Wilson JL, Scott K, Stamp G, Wilbanks GD, Fricker S, Bridger G, Balkwill FR. Multiple actions of the chemokine CXCL12 on epithelial tumor cells in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5930–5938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Porcile C, Bajetto A, Barbieri F, Barbero S, Bonavia R, Biglieri M, Pirani P, Florio T, Schettini G. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha (SDF-1alpha/CXCL12) stimulates ovarian cancer cell growth through the EGF receptor transactivation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;308:241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kukreja P, Abdel-Mageed AB, Mondal D, Liu K, Agrawal KC. Up-regulation of CXCR4 expression in PC-3 cells by stromal-derived factor-1alpha (CXCL12) increases endothelial adhesion and transendothelial migration: role of MEK/ERK signaling pathway-dependent NF-kappaB activation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9891–9898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peng SB, Peek V, Zhai Y, Paul DC, Lou Q, Xia X, Eessalu T, Kohn W, Tang S. Akt activation, but not extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation, is required for SDF-1alpha/CXCR4-mediated migration of epitheloid carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:227–236. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-04-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kryczek I, Lange A, Mottram P, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Hogan M, Moons L, Wei S, Zou L, Machelon V, Emilie D, Terrassa M, Lackner A, Curiel TJ, Carmeliet P, Zou W. CXCL12 and vascular endothelial growth factor synergistically induce neoangiogenesis in human ovarian cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:465–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, Carey VJ, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dalerba P, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:267–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.062105.204854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CH, Jones DL, Visvader J, Weissman IL, Wahl GM. Cancer stem cells–perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang S, Balch C, Chan MW, Lai HC, Matei D, Schilder JM, Yan PS, Huang TH, Nephew KP. Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4311–4320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Valent P, Bonnet D, De Maria R, Lapidot T, Copland M, Melo JV, Chomienne C, Ishikawa F, Schuringa JJ, Stassi G, Huntly B, Herrmann H, Soulier J, Roesch A, Schuurhuis GJ, Wohrer S, Arock M, Zuber J, Cerny-Reiterer S, Johnsen HE, Andreeff M, Eaves C. Cancer stem cell definitions and terminology: the devil is in the details. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:767–775. doi: 10.1038/nrc3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu S, Ginestier C, Ou SJ, Clouthier SG, Patel SH, Monville F, Korkaya H, Heath A, Dutcher J, Kleer CG, Jung Y, Dontu G, Taichman R, Wicha MS. Breast cancer stem cells are regulated by mesenchymal stem cells through cytokine networks. Cancer Res. 2011;71:614–624. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ginestier C, Liu S, Diebel ME, Korkaya H, Luo M, Brown M, Wicinski J, Cabaud O, Charafe-Jauffret E, Birnbaum D, Guan JL, Dontu G, Wicha MS. CXCR1 blockade selectively targets human breast cancer stem cells in vitro and in xenografts. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(2):485–497. doi: 10.1172/JCI39397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Boiko AD, Razorenova OV, van de Rijn M, Swetter SM, Johnson DL, Ly DP, Butler PD, Yang GP, Joshua B, Kaplan MJ, Longaker MT, Weissman IL. Human melanoma-initiating cells express neural crest nerve growth factor receptor CD271. Nature. 2010;466:133–137. doi: 10.1038/nature09161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, Liu R, Wang X, Cho RW, Hoey T, Gurney A, Huang EH, Simeone DM, Shelton AA, Parmiani G, Castelli C, Clarke MF. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bapat SA, Mali AM, Koppikar CB, Kurrey NK. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3025–3029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tomao F, Papa A, Rossi L, Strudel M, Vici P, Lo Russo G, Tomao S. Emerging role of cancer stem cells in the biology and treatment of ovarian cancer: basic knowledge and therapeutic possibilities for an innovative approach. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:48. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tomao F, Papa A, Strudel M, Rossi L, Lo Russo G, Benedetti Panici P, Ciabatta FR, Tomao S. Investigating molecular profiles of ovarian cancer: an update on cancer stem cells. J Cancer. 2014;5:301–310. doi: 10.7150/jca.8610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kusumbe AP, Bapat SA. Cancer stem cells and aneuploid populations within developing tumors are the major determinants of tumor dormancy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9245–9253. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Silva IA, Bai S, McLean K, Yang K, Griffith K, Thomas D, Ginestier C, Johnston C, Kueck A, Reynolds RK, Wicha MS, Buckanovich RJ. Aldehyde dehydrogenase in combination with CD133 defines angiogenic ovarian cancer stem cells that portend poor patient survival. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3991–4001. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kryczek I, Liu S, Roh M, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Wei S, Banerjee M, Mao Y, Kotarski J, Wicha MS, Liu R, Zou W. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase and CD133 defines ovarian cancer stem cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:29–39. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Abubaker K, Latifi A, Luwor R, Nazaretian S, Zhu H, Quinn MA, Thompson EW, Findlay JK, Ahmed N. Short-term single treatment of chemotherapy results in the enrichment of ovarian cancer stem cell-like cells leading to an increased tumor burden. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chau WK, Ip CK, Mak AS, Lai HC, Wong AS. c-Kit mediates chemoresistance and tumor-initiating capacity of ovarian cancer cells through activation of Wnt/beta-catenin-ATP-binding cassette G2 signaling. Oncogene. 2013;32:2767–2781. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pasquier J, Rafii A. Role of the microenvironment in ovarian cancer stem cell maintenance. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:630782. doi: 10.1155/2013/630782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Seo JH, Jeong KJ, Oh WJ, Sul HJ, Sohn JS, Kim YK, Cho do Y, Kang JK, Park CG, Lee HY. Lysophosphatidic acid induces STAT3 phosphorylation and ovarian cancer cell motility: their inhibition by curcumin. Cancer Lett. 2010;288:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Waugh DJ, Wilson C. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6735–6741. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet. 1889;8(2):98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tarin D, Price JE, Kettlewell MGW, Souter RG, Vass ACR, Crossley B. Mechanisms of human tumor metastasis studied in patients with peritoneovenous shunts. Cancer Res. 1984;44:3584–3592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kaplan RN, Rafii S, Lyden D. Preparing the ‘soil’: the Premetastatic Niche. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11089–11093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Psaila B, Lyden D. The metastatic niche: adapting the foreign soil. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nrc2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, Lang G, Bird D, Koong A, Le QT, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kenny HA, Kaur S, Coussens LM, Lengyel E. The initial steps of ovarian cancer cell metastasis are mediated by MMP-2 cleavage of vitronectin and fibronectin. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1367–1379. doi: 10.1172/JCI33775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhang XH, Jin X, Malladi S, Zou Y, Wen YH, Brogi E, Smid M, Foekens JA, Massague J. Selection of bone metastasis seeds by mesenchymal signals in the primary tumor stroma. Cell. 2013;154:1060–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cheng B, Lu W, Xiaoyun W, YaXia C, Xie X. Extra-abdominal metastases from epithelial ovarian carcinoma: an analysis of 20 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:611–614. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a416d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cormio G, Rossi C, Cazzolla A, Resta L, Loverro G, Greco P, Selvaggi L. Distant metastases in ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:125–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hudson LG, Zeineldin R, Stack MS. Phenotypic plasticity of neoplastic ovarian epithelium: unique cadherin profiles in tumor progression. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:643–655. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9171-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Veatch AL, Carson LF, Ramakrishnan S. Differential expression of the cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin in ascites and solid human ovarian tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:393–399. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Obermajer N, Muthuswamy R, Odunsi K, Edwards RP, Kalinski P. PGE (2)-induced CXCL12 production and CXCR4 expression controls the accumulation of human MDSCs in ovarian cancer environment. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7463–7470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhu GG, Risteli J, Puistola U, Kauppila A, Risteli L. Progressive ovarian carcinoma induces synthesis of type I and type III procollagens in the tumor tissue and peritoneal cavity. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5028–5032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mustea A, Pirvulescu C, Konsgen D, Braicu EI, Yuan S, Sun P, Lichtenegger W, Sehouli J. Decreased IL-1 RA concentration in ascites is associated with a significant improvement in overall survival in ovarian cancer. Cytokine. 2008;42:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lafky JM, Wilken JA, Baron AT, Maihle NJ. Clinical implications of the ErbB/epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor family and its ligands in ovarian cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1785:232–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Salazar H, Godwin AK, Daly MB, Laub PB, Hogan WM, Rosenblum N, Boente MP, Lynch HT, Hamilton TC. Microscopic benign and invasive malignant neoplasms and a cancer-prone phenotype in prophylactic oophorectomies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1810–1820. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.24.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Chene G, Penault-Llorca F, Le Bouedec G, Mishellany F, Dauplat MM, Jaffeux P, Aublet-Cuvelier B, Pouly JL, Dechelotte P, Dauplat J. Ovarian epithelial dysplasia and prophylactic oophorectomy for genetic risk. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:65–72. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181990127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nakayama K, Nakayama N, Kurman RJ, Cope L, Pohl G, Samuels Y, Velculescu VE, Wang TL, Shih IM. Sequence mutations and amplification of PIK3CA and AKT2 genes in purified ovarian serous neoplasms. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:779–785. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Freedman RS, Deavers M, Liu J, Wang E. Peritoneal inflammation - A microenvironment for Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (EOC) J Transl Med. 2004;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rafii A, Mirshahi P, Poupot M, Faussat A-M, Simon A, Ducros E, Mery E, Couderc B, Lis R, Capdet J, Bergalet J, Querleu D, Dagonnet F, Fourni J-J, Marie J-P, Pujade-Lauraine E, Favre G, Soria J, Mirshahi M. Oncologic trogocytosis of an original stromal cells induces chemoresistance of ovarian tumours. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Castells M, Thibault B, Mery E, Golzio M, Pasquet M, Hennebelle I, Bourin P, Mirshahi M, Delord JP, Querleu D, Couderc B. Ovarian ascites-derived Hospicells promote angiogenesis via activation of macrophages. Cancer Lett. 2012;326:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Castells M, Milhas D, Gandy C, Thibault B, Rafii A, Delord JP, Couderc B. Microenvironment mesenchymal cells protect ovarian cancer cell lines from apoptosis by inhibiting XIAP inactivation. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e887. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Shostak A, Chakrabarti E, Hirszel P, Maher JF. Effects of histamine and its receptor antagonists on peritoneal permeability. Kidney Int. 1988;34:786–790. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]