SUMMARY

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide are generated at wound sites and act as long-range signals in wound healing. The roles of other ROS in wound repair are little explored. Here we reveal a cytoprotective role for mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) in C. elegans skin wound healing. We show that skin wounding causes local production of mtROS superoxide at the wound site. Inhibition of mtROS levels by mitochondrial superoxide-specific antioxidants blocks actin-based wound closure, whereas elevation of mtROS promotes wound closure and enhances survival of mutant animals defective in wound healing. mtROS act downstream of wound-triggered Ca2+ influx. We find that the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter MCU-1 is essential for rapid mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and mtROS production after wounding. mtROS can promote wound closure by local inhibition of Rho GTPase activity via a redox-sensitive motif. These findings delineate a pathway acting via mtROS that promotes cytoskeletal responses in wound healing.

INTRODUCTION

Skin wound repair is essential for animals to survive in a harsh environment (Singer and Clark, 1999). Human wounds result from trauma, pathogen infections and conditions such as diabetes, affecting millions of people worldwide per year (Gurtner et al., 2008; Sonnemann and Bement, 2011). Repair of skin wounds is also an essential prerequisite for many kinds of tissue regeneration (Martin, 1997; Murawala et al., 2012). Thus, understanding how organisms recognize and repair epidermal wounds is of wide interest. Despite over two millennia of studies into wound healing (Sipos et al., 2004), until recently little was understood of the molecular basis of skin wound repair.

Many insights into the cell and molecular biology of wound healing have come from studies in model organisms, including Drosophila (Galko and Krasnow, 2004; Wood et al., 2002), Xenopus (Bement et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2003; Love et al., 2013), zebrafish (Niethammer et al., 2009; Schebesta et al., 2006), and C. elegans (Xu and Chisholm, 2011). Following injury, epithelia execute a coordinated program that closes the wound, combats infection, re-establishes barrier function, and restores tissue architecture (Cordeiro and Jacinto, 2013). Some key transcriptional regulators of wound healing are conserved between vertebrates and invertebrates (Mace et al., 2005; Ting et al., 2005), suggesting that despite the variety of skin structures in different animals, epidermal wound healing mechanisms may be shared (Sonnemann and Bement, 2011).

Wound repair must be initiated rapidly, and wounding triggers multiple transcription-independent signals (Cordeiro and Jacinto, 2013). Among these, elevation of intracellular Ca2+ is a near-universal immediate damage signal. Pioneering studies in epithelia showed that wounding induces Ca2+ waves (Lansdown, 2002; Tran et al., 1999). Injury-triggered Ca2+ waves are critical for wound responses and repair in multiple model organisms (Chen et al., 2003; Clark et al., 2009; Razzell et al., 2013; Xu and Chisholm, 2011; Yoo et al., 2012).

Wound closure frequently involves radical reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton at the cell and tissue level. Many signals and cytoskeletal structures normally used for cell polarization are reactivated at wounds (Razzell et al., 2014; Sonnemann and Bement, 2011). A dramatic example is during embryonic wound healing where an actomyosin cable composed of F-actin and myosin II, known as a purse-string, is assembled at the wound (Bement et al., 1999; Sonnemann and Bement, 2011). In many invertebrate and vertebrate organisms, where actomyosin cables are involved in wound closure and are regulated via RHO family small GTPases (Bement et al., 1999; Burridge and Wennerberg, 2004; Wood et al., 2002).

In the adult C. elegans the epidermis is made up of a small number of multinucleate syncytia (Chisholm and Hsiao, 2012). We previously reported that wounding the C. elegans syncytial epidermis triggers a sustained rise in intracellular Ca2+ required for local recruitment of F-actin at the wound site (Xu and Chisholm, 2011). Wound closure in the epidermal syncytium involves formation of actin rings surrounding the wound site; these rings close up the wound over a period of 2-4 h. While superficially reminiscent of actin purse-strings seen in multicellular wound closure, the actin rings in the C. elegans epidermis appear to be primarily closed by Arp2/3 dependent actin assembly. Actin ring closure is also negatively regulated by RHO-1 and nonmuscle myosin. It remains unknown how the widespread elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ in the epidermis triggers actin accumulation locally at the wound site.

A second widespread transcription-independent response to damage is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Suzuki and Mittler, 2012). Extracellular ROS have long been known to play antimicrobial roles after tissue injury or infection (Babior, 1978; Winterbourn and Kettle, 2013). Wounding also causes the synthesis of extracellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which functions as a long-range chemoattractant that recruits inflammatory cells to wound sites (Niethammer et al., 2009; Razzell et al., 2013; Yoo et al., 2011). ROS signaling is also required for Xenopus tadpole fin regeneration (Love et al., 2013). In Drosophila, extracellular H2O2 is generated by the Ca2+-stimulated plasma membrane enzyme Dual oxidase (Duox) (Razzell et al., 2013), indicating that Ca2+ signaling acts upstream of ROS production. In addition to being made by membrane and cytosolic oxidases, intracellular ROS are also generated as byproducts of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) (Dickinson and Chang, 2011). Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) signals have been implicated in diverse stress responses, such as adaptation to hypoxia (Chandel et al., 1998), regulation of immunity (West et al., 2011), and regulation of lifespan (Hekimi et al., 2011). In these cases, mtROS appear to be induced by stress and signal to facilitate cellular adaptation to stress.

Here, we show that C. elegans skin wounding triggers rapid and local production of mtROS at wounds, in response to the epidermal Ca2+ signal. mtROS are required for efficient wound closure, and elevated mtROS accelerates skin wound closure. We define a pathway linking mitochondrial Ca2+, mtROS production and the RHO-1 GTPase. Our findings reveal mtROS as key signals in promoting skin wound healing.

RESULTS

C. elegans skin wounding triggers local production of mitochondrial ROS superoxide

In other paradigms of wound healing, endogenously produced ROS such as H2O2 are induced by damage and attract migratory cells to wound sites. We are using adult C. elegans skin as a model to study wound healing (Figure S1A)(Xu and Chisholm, 2011). As C. elegans lacks migratory phagocytic cells we tested whether intracellular ROS play roles in wound repair. Mitochondria are major sources of intracellular ROS. mtROS are generated as byproducts of the electron transport chain (ETC) in the mitochondrial matrix or intermembrane space. The primary mtROS, superoxide (O2−), is converted spontaneously or by superoxide dismutases (SODs) into H2O2 in the matrix or cytosol (Murphy, 2009). To visualize mtROS in intact animals we used the genetically encoded mtROS sensor cpYFP, which displays occasional transient elevations known as ‘mitochondrial flashes’ (mitoflashes), reflecting increases in the mtROS superoxide (Hou et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2008). In the unwounded epidermis,mito::cpYFP levels were stable, but displayed a low frequency of spontaneous mitoflashes (Figure 1A,B; Figure S1B; Movie S1). After laser wounding, mitoflashes were suppressed for 70-100 s, then significantly increased both in frequency and amplitude for several minutes (Figure 1A-1D). Wound-induced mitoflashes were most frequent in the mitochondria close to the wound site, and individual mitochondria often flashed repeatedly (Figure 1E,F). Wound-induced mitoflashes lasted several times as long as those in unwounded worms (Figure 1G) and displayed significantly increased amplitude (Figure 1D). We observed similar patterns of mitoflashes after needle wounding (data not shown).

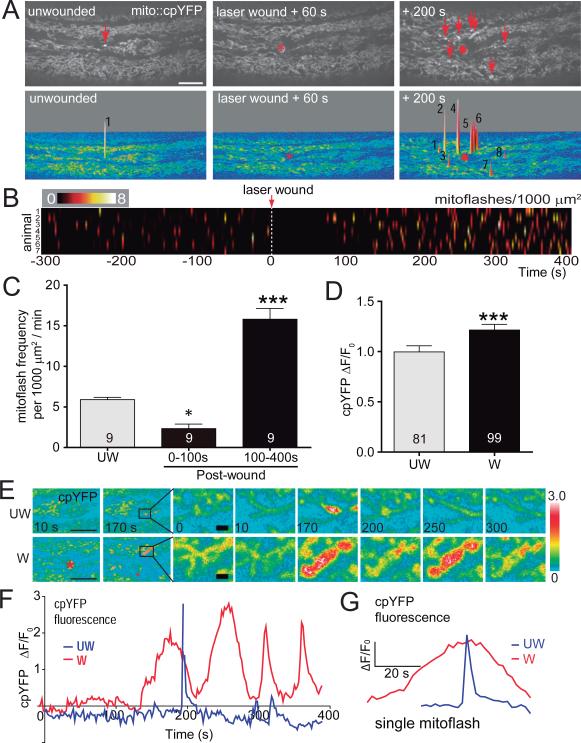

Figure 1. C. elegans epidermal wounding triggers a local burst of mitochondrial ROS superoxide.

(A) Laser wounding first inhibits and then induces mitochondrial cpYFP flashes (mitoflashes). Top: representative confocal images of mito::cpYFP in adult C. elegans epidermis before and after laser wounding (see Movie S1). Red asterisk indicates the wound site and red arrows indicate individual mitoflashes. Scale, 10 μm. Bottom: images of mitoflash events shown as surface plots from top images. Numbers indicate number of individual mitoflashes at each position.

(B) Heat map of mitoflash frequency in ROI of 1000 μm2 before and after wounding; each line represents mitoflashes in a single animal; n = 7 animals.

(C) Quantitation of mitoflashes in 1000 μm2 regions per min, n = 9 animals. In the first 100 s after wounding, mitoflashes decreased, *, P < 0.05 (versus control unwounded). In the next 5 min, mitoflashes significantly increased, ***, P < 0.001 (versus unwounded), ANOVA.

(D) Amplitude of mito::cpYFP intensity change of individual mitoflashes in unwounded and wounded animals, n > 80 flashes from 9 animals. ***, P < 0.001, Student's t-test. Data in C,D are mean ± SEM.

(E) Images of single mitochondria displaying mitoflashes in unwounded and wounded C. elegans epidermis over 300 s time course; scale, left: 10 μm; right (enlarged image): 1 μm.

(F) Time course (400 s) of representative single mitoflash intensity change in UW and W worms shown in panel (E).

(G) Comparison of representative cpYFP dynamics in a single mitoflash in wounded (W, red) versus unwounded epidermis (UW, blue).

Superoxide is converted into H2O2 either spontaneously or enzymatically by SODs. To ask whether wounding also affected mitochondrial H2O2 we expressed the genetically encoded H2O2 sensor HyPer2 (Belousov et al., 2006; Markvicheva et al., 2011) in epidermal mitochondria. However, we did not observe changes in HyPer2 fluorescence before or after wounding (Figure S1C,D), suggesting wounding specifically affects superoxide. cpYFP fluorescence is pH sensitive (Schwarzlander et al., 2012; Wei-LaPierre et al., 2013); however the pH sensor mito::pHluorin did not show flash-like dynamics before or after wounding, but instead decreased in intensity after wounding (Figure S1C,D), suggestive of mitochondrial acidification (Johnson and Nehrke, 2010). These observations suggest that wound induced mitoflashes are not due to alterations in mitochondrial pH and that wounding triggers production of mtROS superoxide.

Pharmacological elevation of mtROS promotes actin-based wound closure

We next attempted to manipulate epidermal mtROS by treatment with pro- or anti-oxidant drugs. Treatment with the pro-oxidant paraquat (PQ), which induces mitochondrial superoxide, significantly increased both baseline mito::cpYFP fluorescence (Figure S2B) and mitoflash frequency, before and after wounding (Figure S2A,C, Movie S2). Conversely, treatment with mitoTempo, a mitochondrially-targeted superoxide specific antioxidant, significantly decreased mitoflash frequency (Figure 2A,B, Movie S3), consistent with a previous report (Huang et al., 2011). The broad spectrum antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) decreased baseline mito::cpYFP fluorescence (Figure S2B) and mitoflash frequency both before wounding and after wounding (Figure S2A,C), and also reduced mitoflash amplitudes after wounding (Figure S2D).

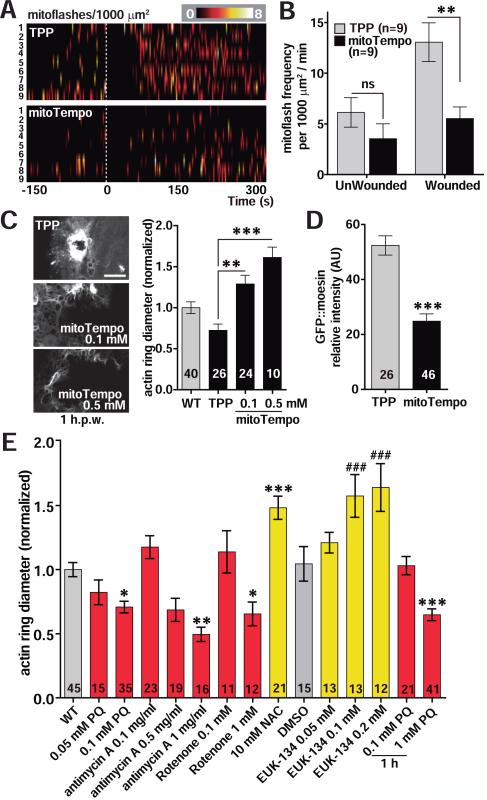

Figure 2. Mitochondrial ROS production is required for epidermal wound closure.

(A, B) mitoTempo treatment significantly inhibits wound-induced mitoflashes. Heat maps of mitoflashes in ROIs of 1000 μm2 of adult epidermis treated with mitoTempo or control triphenylphosphonium chloride (TPP) before and after laser wounding (at 0 s) (see Movie S3). Each line indicates a single animal.

(B) Quantitation of mitoflash frequency in animals shown in panel A. **, P < 0.01, Student's t-test.

(C-D) Modulation of mtROS levels affects wound closure. (C) Left, representative confocal images of the F-actin marker GFP::moesin at 1 h post needle wounding (h.p.w.) in TPP (0.1 mM) and mitoTempo (0.1 mM, 0.5 mM) treated worms; scale, 10 μm. Right, quantitation of F-actin ring diameter in WT, TPP and mitoTempo treated worms. Adult worms were incubated in 0.1 mM TPP or mitoTempo for 1 h before wounding. Number of animals indicated in bars. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs TPP. ANOVA. (D) mitoTempo reduces GFP::moesin intensity at wound site. GFP::moesin intensity at the wound site in TPP (0.1 mM) and mitoTempo (0.1 mM) treated worms in panel (C). ***, P < 0.001, Student's t-test.

(E) Treatment with oxidants (red bars) accelerates wound closure, and treatment with antioxidants (yellow bars) inhibits wound closure; quantitation of F-actin rings as in panel C. Worms were incubated on drug plates for 24 h from L4 stage at 20 °C except for acute treatment with PQ, added 1 h before needle wounding. *, P< 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001 vs WT, ANOVA; ###, P < 0.001 vs control DMSO, ANOVA.

To address whether manipulating mtROS could affect wound repair we analyzed the dynamics of actin rings that close epidermal wounds, using the F-actin probe GFP::moesin (Figure S2E) (Xu and Chisholm, 2011). Low concentrations of mitoTempo (0.1-0.5 mM) significantly delayed actin ring closure, and reduced GFP::moesin intensity around wounds (Figure 2C,D), suggesting mtROS is required for actin recruitment to wound sites. Treatment of L4 animals with low concentrations (< 0.1 mM) of PQ enhanced actin ring formation after wounding (Figure 2E) and did not affect survival (Figure S2F). Treatment with high levels of PQ (1 mM) immediately prior to wounding enhanced wound closure (Figure 2E) and did not affect survival if PQ was removed 4 h after wounding (Figure S2F). These results suggest elevated mtROS levels promote wound closure.

As PQ may have many other effects (Bus and Gibson, 1984), we tested whether other oxidants affect wound repair. Treatment with two superoxide-inducing oxidants, Antimycin A, which disrupts complex III of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) (Chen et al., 2003), and Rotenone, which inhibits the ETC at NADH oxidoreductase (Ved et al., 2005), promoted wound closure (Figure 2E). In contrast, treatment with NAC inhibited actin ring formation (Figure 2E) and significantly reduced post-wounding survival (Figure S2G). NAC is a nonspecific ROS scavenger, raising the question whether the effects observed above were due to non-mitochondrial ROS. To address this, we treated L4 worms with the SOD mimetic EUK-134, which increases both SOD and catalase activity and converts superoxide to H2O2 and then to H2O (Melov et al., 2000). EUK-134 treatment significantly impaired wound closure (Figure 2E). Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), which can inhibit H2O2 production by C. elegans Duox (Chavez et al., 2009), did not affect actin ring formation (Figure S2H). Conversely, increasing H2O2 concentration by treatment with a stable H2O2 derivative, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBOOH) (Tullet et al., 2008), slightly impaired wound closure (Figure S2H). Taken together, the results from these pharmacological experiments suggest mtROS, primarily superoxide, is rate-limiting in actin-mediated wound closure.

Genetic elevation of mtROS results in accelerated wound repair

To determine whether endogenous mtROS function in wound repair, we tested superoxide dismutase (SOD) mutants, known to display elevated mitochondrial superoxide (Van Raamsdonk and Hekimi, 2012; Yang et al., 2007). Among the five C. elegans SOD mutants tested, loss of either of the two mitochondrial MnSODs, SOD-2 and SOD-3 (Honda et al., 2008), significantly promoted wound closure (Figure 3A,B; Figure S3A,B; Movie S4). Conversely, overexpression of SOD-2 in the adult epidermis rescued the faster wound closure in sod-2 mutants and impaired wound closure in a sod-2(+) background (Figure S3C), consistent with mtROS being required autonomously within the epidermis. Loss of SOD-1, the major Cu/Zn SOD localized to the cytosol and mitochondrial intermembrane space (Doonan et al., 2008), also resulted in enhanced wound closure (Figure 3A, B). sod-4 or sod-5 mutants displayed normal wound closure (Figure 3B). Double mutants of sod-1; sod-2, or sod-2; sod-3, as well as sod-1,-3,-5 sod-1,-4,-5 triple mutants, and sod-1,-3,-4,-5 quadruple mutants all displayed enhanced wound closure (Figure 3A,B), indicating that chronically elevated mtROS resulting from reduced SOD activity can promote wound closure.

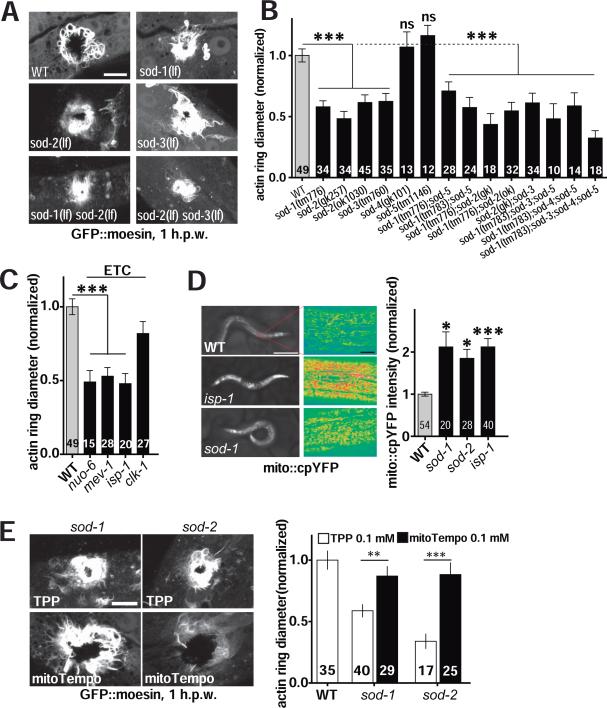

Figure 3. Genetic elevation of mitochondrial ROS accelerates wound repair.

(A-B) Mutants lacking superoxide dismutases SOD-1, SOD-2, or SOD-3 display accelerated wound repair after needle wounding (see Movie S4). (A) Representative confocal images of F-actin (GFP::moesin) at 1 h.p.w. in WT or sod loss of functionmutants. Scale, 10 μm. (B) Quantitation of actin ring diameter in wounded sod mutant worms. Number of animals indicated in bars in panels B-E. ***, P < 0.001, vs WT, ANOVA.

(C) Quantitation of actin ring diameter in mitochondrial mutants at 1 h.p.w. Electron transfer chain (ETC) mutants show faster wound closure (see Movie S4). F-actin ring diameter is normalized to WT. NUO-6, MEV-1, ISP-1, and CLK-1 are ETC components. ***, P < 0.001 (versus WT), ANOVA.

(D) Loss of function in isp-1, sod-1, or sod-2 causes increased mito::cpYFP fluorescence. Left, epidermal mito::cpYFP signal in young adults; scale, 250 μm. Center, epidermal mito::cpYFP in WT and mutants (intensity color code); scale, 10 μm. Right, quantitation of mito::cpYFP intensity in midbody epidermis, *, P < 0.05, ***, P < 0.001 (versus WT), ANOVA.

(E) Images and quantitation of F-actin rings (1 h.p.w.) in TPP- and mitoTempo-treated worms. WT or mutant worms (sod-1 and sod-2) were incubated on drug plates (0.1 mM TPP or mitoTempo) from L4 stage to young adult (24 h). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Student's t-test.

Mutants with impaired ETC function also display elevated mtROS (Lee et al., 2010; Senoo-Matsuda et al., 2001; Yang and Hekimi, 2010). We found that several such ETC mutants displayed accelerated wound closure (Figure 3C, Figure S3D and Movie S4), including isp-1 (Rieske iron sulphur protein, complex III), mev-1 (cytochrome b, subunit of complex II), and nuo-6 (NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase, complex I). isp-1, sod-1, and sod-2 mutants showed elevated mito::cpYFP fluorescence before wounding (Figure 3D). Using the dye mitoSOX, which specifically labels mitochondrial superoxide, we found mitochondrial mutants mev-1, isp-1, and sod-1 displayed elevated superoxide levels (Figure S3F,G). Treatment with the antioxidant mitoTempo suppressed the faster wound closure in sod-1 and sod-2 mutants (Figure 3E). The faster wound closure of isp-1, mev-1, or sod-1 mutants was also suppressed by NAC (Figure S3H,I), indicating that the improved wound closure in mitochondrial mutants is a result of their elevated levels of mtROS.

Mitochondrial ROS act downstream of Ca2+ in wound closure

Wounding the C. elegans epidermis triggers multiple signaling cascades including a TIR-1/PMK-1 p38 MAP kinase dependent innate immune response (Pujol et al., 2008), and a TRPM/GTL-2 dependent Ca2+ signal that has been shown to promote actin based wound repair (Xu and Chisholm, 2011). Loss of function in either pathway reduces animal survival after wounding. To determine the relationship between mtROS signals and these pathways we examined the post-wounding survival of double mutants. Loss of function in isp-1 did not suppress the defect in post-wounding survival of tir-1 mutants (Figure S4A), suggesting elevated mtROS cannot compensate for lack of the TIR-1 innate immune pathway. In contrast, isp-1 gtl-2 double mutants displayed significantly improved survival after wounding, compared to gtl-2 mutants (Figure 4A). The post-wounding survival defect of gtl-2 mutants was also suppressed in sod-1 double mutants and after PQ treatment (Figure S4B). Remarkably, the F-actin wound closure defects of gtl-2 mutants were fully suppressed in double mutants with isp-1 or sod-1, or by treatment with PQ (Figure 4B,C). These results are consistent with mtROS acting downstream of GTL-2/Ca2+ signaling in wound closure, in parallel to the TIR-1 innate immune pathway.

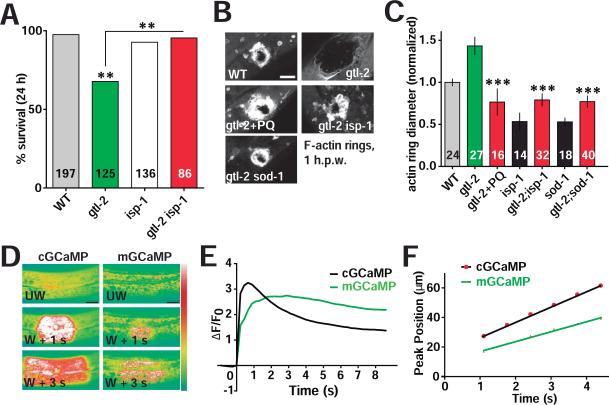

Figure 4. Mitochondrial ROS signals act downstream of Ca2+ to promote epidermal wound repair.

(A) Elevated mtROS suppresses the reduced survival of gtl-2(lf) mutants after needle wounding. gtl-2(lf) mutants show reduced survival 24 h.p.w., whereas isp-1(lf) gtl-2(lf) double mutants show normal survival 24 h.p.w. **, P < 0.01, Fisher's exact test.

(B) gtl-2(lf) mutants display delayed or reduced F-actin ring formation after needle wounding; this is suppressed by acute treatment with 1 mM PQ or in double mutants with isp-1 or sod-1. Representative images of F-actin rings at 1 h.p.w. Scale, 10 μm.

(C) Quantitation of F-actin ring diameter of animals shown in (B); mutants are normalized to WT. ***, P < 0.001 (vs. gtl-2(lf)), ANOVA.

(D) Laser wounding triggers elevated cytosolic Ca2+ (visualized with cGCaMP) and local mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (visualized with mGCaMP) in the adult epidermis (see Movie S5); GCaMP3 (juIs319) and mito::GCaMP3 (juEx4955) were expressed under the control of col-19 promoter, labeling cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ respectively. Intensity code. Scale, 10 μm.

(E) The cytosolic Ca2+ wave precedes mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Mean GCaMP3 intensity change (ΔF/F0) in cytosol and mitochondria at 20 μm from wound, n = 33.

(F) The average velocity of the mitochondrial GCaMP3 (mGCaMP) wave is slower than the epidermal GCaMP3 (cGCaMP) wave upon laser wounding, n = 11.

See also Figure S4A-D and Movie S5.

We next asked how Ca2+ activation after wounding contributed to mtROS production. To examine mitochondrial Ca2+ levels we targeted the Ca2+ sensor GCaMP3 to the mitochondrial matrix (mGCaMP) and found that wounding triggers rapid Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria (Figure 4D, Movie S5). The wave of mGCaMP fluorescence starts later and travels more slowly than the previously described wave of wound–triggered cytosolic GCaMP3 (cGCaMP) (Figure 4E, F, Movie S5), consistent with Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria being a result of elevated cytosolic Ca2+. The cytosolic Ca2+ rise spreads > 200 μm from the wound site (Xu and Chisholm, 2011), whereas mitochondrial Ca2+ increased only within 50 μm of the wound site (Figure S4C), suggesting rapid mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake requires a threshold level of cytosolic Ca2+ (Figure S4D).

Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondria matrix is mediated by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (Rizzuto et al., 2012), of which the protein MCU is an essential component (Baughman et al., 2011; De Stefani et al., 2011). To ask whether mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake functions in mtROS production and wound repair, we generated a deletion in the gene mcu-1 (Figure 5A; see Experimental Procedures), which encodes the C. elegans ortholog of MCU. The mcu-1 null mutants are viable and fertile, and display slightly decreased baseline mGCaMP (Figure 5B,C) and normal mitoflash frequency prior to wounding (Figure 5D). However mcu-1 mutants were strongly impaired in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake after laser or needle wounding (Figure 5B,C; Figure S4E; Movie S6) and showed reduced wound-induced mitoflashes (Figure 5D; Figure S4F; Movie S7). To test whether the TRPM/GTL-2-dependent cytosolic Ca2+ influx acted upstream of mtROS production, we examined mitoflashes in gtl-2 mutants. Partial loss of function (lf) and null (0) gtl-2 mutants both displayed fewer mitoflashes (Figure 5D; Figure S4F). These results suggest Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondria from cytosol contributes to mtROS production.

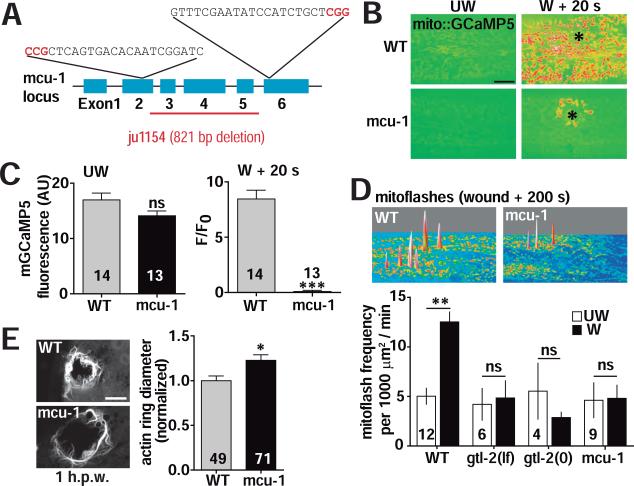

Figure 5. The mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter MCU-1 is required for wound induced mtROS superoxide production and wound repair.

(A) mcu-1 gene structure. mcu-1(ju1154) is an 821 bp deletion of exons 3-5 and part of exon 2. Two sgRNA sequences were used to generate a deletion using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

(B) The mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter subunit MCU-1 is required for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake after laser wounding. Representative images of mitochondrial Ca2+ after wounding in WT and mcu-1(ju1154) mutants (see Movie S6). Mitochondrial Ca2+ labeled with mito::GCaMP5 (juSi103). Black asterisk (*) indicates the wound site. Scale: 10 μm.

(C) Quantitation of mito::GCaMP5 (juSi103) in unwounded (left) and wounded (right) worms. ***, P < 0.001, Student's t-test.

(D) Cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ influxes are required for the increase in mitoflash frequency after wounding. Top: surface plot of mitoflash images in WT and mcu-1 mutants. Bottom: quantitation of mitoflash frequency in WT, mcu-1, gtl-2(lf) and gtl-2(0) mutants, before (UW) and after (W) wounding. **, P < 0.01, Student's t-test.

(E) mcu-1 mutants are defective in wound closure. Left: confocal image of F-actin ring formation around wound site in WT and in mcu-1 mutant. Right: normalized F-actin ring diameter. *, P < 0.05. Student's t-test, scale, 10 μm. Number of animals indicated in bars in panels C-E.

See also Figure S4E-H and Movie S6, S7.

To address how mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake affects wound closure we examined actin ring formation in mcu-1 mutants and found that loss of mcu-1 impaired wound closure (Figure 5E; Figure S4G). Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake can trigger opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) (Brookes et al., 2004), which decreases mitochondrial membrane potential and causes mtROS release (Rasola and Bernardi, 2011; Wang et al., 2008). To test whether the mPTP was involved in wound repair, we treated worms with the mPTP inhibitor Cyclosporine A (CsA) (Bernardi, 1996; Broekemeier et al., 1989), and found that CsA inhibited wound closure in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S4H). Taken together, these data suggest MCU-1 mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake triggers mtROS production by causing transient opening of the mPTP.

Mitochondrial ROS act upstream of Rho GTPases in wound healing

How might mtROS promote actin-based wound closure? We previously showed that wound closure involves antagonistic roles of the small GTPases CDC-42 and RHO-1 (Xu and Chisholm, 2011). CDC-42 is required for F-actin accumulation into rings at wound sites, whereas RHO-1 and non-muscle myosin negatively regulate wound closure; loss of function in rho-1, or in non-muscle myosin (nmy-1, mlc-4), results in accelerated wound closure. As loss of function in isp-1 or sod-1 caused rho-1-like accelerated actin ring closure, we tested whether the effects of these mutants required RHO-1 or CDC-42. We found that RNAi of rho-1 or mlc-4 neither enhanced nor suppressed the fast closure phenotypes of isp-1 or sod-1 mutants (Figure 6A), consistent with mtROS acting in the same pathway as RHO-1. NAC treatment suppressed the fast wound closure in isp-1 or sod-1 mutants (Figure S3H,I) but had no effect on the rapid closure of rho-1 or mlc-4 mutants (Figure 6B), suggesting mtROS signals act upstream of RHO-1 in wound closure. Conversely, cdc-42(RNAi) blocked the accelerated actin assembly in isp-1 and sod-1 mutants, or after PQ treatment (Figure S5A), consistent with CDC-42 acting downstream of the mtROS signal. These studies place mtROS upstream of both RHO-1 and CDC-42 in regulating F-actin assembly and ring formation.

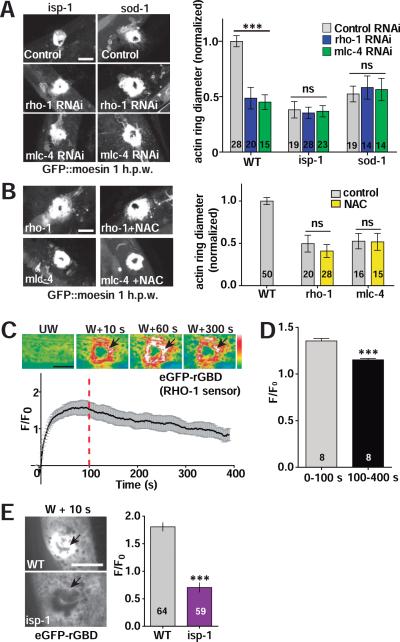

Figure 6. Mitochondrial ROS act upstream of RHO-1.

(A) Left, representative confocal images of F-actin ring formation after needle wounding. rho-1(RNAi) or mlc-4(RNAi) does not enhance the accelerated wound closure of isp-1 or sod-1 mutants. Control RNAi: L4440 empty vector. Right, F-actin ring diameter 1 h.p.w., Student's t-test. Number of animals indicated in bars in panels A,B,D,F.

(B) NAC does not block the enhanced wound closure caused by rho-1 or mlc-4 RNAi; images and quantitation as in panel A. Scale, 10 μm. Statistics: Student's t-test.

(C) Laser wounding activates RHO-1 around the wound site. Top, images of RHO-1 sensor eGFP-rGBD fluorescence in epidermis before and after wounding (see Movie S8), black arrows indicate RHO-1 activation zone. Bottom, eGFP-rGBD fluorescence intensity at activation zone. n = 8, mean ± SEM.

(D) eGFP-rGBD fluorescence intensity increases rapidly after wounding then declines. Average ΔF/F0 from 0-100 s and 100-400 s at activation zone after wounding. Average ΔF/F0 of eGFP-rGBD at 0-100 and 100-400 s (n = 8 animals). ***, P < 0.001, Student's t-test.

(E) Mutants with elevated mitochondrial ROS display reduced RHO-1 activation after wounding. Left: representative images of the RHO-1 sensor eGFP::rGBD fluorescence change upon laser wounding. Black arrows indicate RHO-1 activation zone. Right: quantitation of eGFP::rGBD fluorescence at activation zone from left at 10 s post wounding. ***, P < 0.001, Student's t-test. Number of animals in columns. Scale (A-C, E), 10 μm.

See also Figure S5A-D and Movie S8.

Since RHO-1 negatively regulates actin ring closure in C. elegans skin wound repair, we hypothesized that mtROS inhibits RHO-1 to promote wound repair. To test this, we expressed the genetically encoded Rho sensor eGFP-rGBD (Benink and Bement, 2005) in the epidermis to visualize RHO-1 activation. Laser wounding caused a rapid increase in eGFP-rGBD intensity at the wound site (Figure 6C, Movie S8). rho-1(RNAi) almost abolished eGFP-rGBD activation, indicating the eGFP-rGBD signal was dependent on rho-1 expression (Figure S5B-D). eGFP-rGBD intensity transiently increased during the first 100 s after wounding and then declined (Figure 6C, D). This time-course of activation and inhibition was complementary to the suppression then elevation of mitoflashes after wounding (Figure 1B), consistent with elevated mtROS inhibiting RHO-1 activation. eGFP-rGBD activation after wounding was significantly decreased in isp-1 mutant (Figure 6E,F), suggesting mtROS either directly or indirectly inhibits RHO-1 activity to promote wound closure.

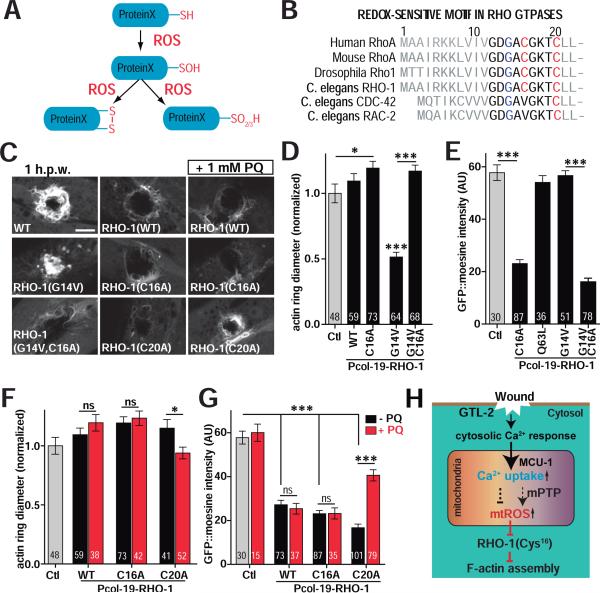

Mitochondrial ROS regulate RHO-1 activity via its redox-sensitive motif in epidermal wound repair

How might mtROS signals regulate RHO-1 in wound closure? ROS modulate protein activity by oxidation of Cysteine (Cys) residues (Lambeth and Neish, 2014)(Figure 7A). Rho family GTPases contain a conserved redox-sensitive G12XXXXGK(S/T)C20 motif that allows activation by ROS modification at C20 (Heo and Campbell, 2005) (Figure 7B). Rho itself contains an additional Cys residue in the motif GXXXC16GK(S/T)C20; high levels of ROS can inhibit Rho by inducing disulfide bond formation between the two Cys residues (Heo et al., 2006; Mitchell et al., 2013) (Figure 7A). C. elegans RHO-1 contains the motif GDGAC16GKTC20 (Figure 7B), suggesting that it may be inhibited by high levels of mtROS. To test this idea, we overexpressed WT or mutant rho-1 cDNAs specifically in adult epidermis and examined wound closure. Overexpression of rho-1(WT) slightly delayed wound closure and significantly reduced F-actin accumulation (Figure 7C, D), consistent with RHO-1 overexpression inhibiting F-actin accumulation. Overexpression of RHO-1(C16A) significantly inhibited wound closure and reduced F-actin accumulation (Figure 7C,E), suggesting the inhibitory activity of RHO-1(C16A) is higher than that of RHO-1(WT). Overexpression of the constitutively activated (ca) mutant RHO-1(G14V) enhanced wound closure, suggesting caRHO-1 has a dominant negative effect (Figure 7C,D; Figure S5E), consistent with a previous report that overexpression of caRhoA inhibits RhoA in Xenopus (Benink and Bement, 2005). The observed dominant negative effects of ca-RHO-1 could have a number of explanations, including effects of chronic RHO-1 activity on the cell cortex, sequestration of other factors required for normal RHO activity, or a requirement for RHO-1 activity turnover in wound closure (Benink and Bement, 2005). The RHO-1 double mutant G14V C16A was not able to promote wound closure (Figure 7C-E), suggesting the C16 residue is required for the caRHO-1(G14V) dominant negative activity.

Figure 7. RHO-1 activity in wound closure requires Cys16 in the redox-sensitive motif.

(A) Cartoon of protein Cysteine thiol oxidation by ROS.

(B) Conserved N-terminal redox-sensitive motifs of RHO family members; Glycine 14 is shown in blue and Cysteine 16 and 20 in red. G14V constitutively activates Rho.

(C) RHO-1 overexpression blocks wound closure. Confocal images of F-actin ring formation after needle wounding. WT RHO-1 and its mutants RHO-1(G14V), RHO-1(C16A), RHO-1(G14V,C16A), RHO-1(C20A) were expressed using the col-19 promoter. Scale, 10 μm.

(D) Overexpression of constitutively active caRHO-1(G14V) enhanced wound closure while RHO-1(C16A) delayed wound closure and suppressed the effect of G14V. Quantitation of F-actin ring diameter 1 h.p.w. Number of animals indicated in bars in panels D-G. *, P < 0.05, ***, P < 0.001, ANOVA (Bonferroni post test).

(E) Overexpression of RHO-1(C16A) inhibited actin assembly and suppressed the effect of RHO-1(G14V) in wound repair. Quantitation of F-actin accumulation (GFP::moesin intensity). ***, P < 0.001, Student's t-test.

(F) PQ treatment suppressed the effect of RHO-1(C20A) overexpression on wound closure. Actin ring diameter 1 h.p.w. in animals overexpressing WT or mutant RHO-1, with or without acute treatment of 1 mM PQ. *, P < 0.05. Student's t-test.

(G) F-actin intensity at wound site 1 h.p.w., with or without acute treatment of 1 mM PQ. PQ treatment suppressed the inhibitory effects of RHO-1(C20A) expression on actin assembly. ***, P < 0.001, Student's t-test.

(H) Model for the Ca2+/mtROS/RHO-1 pathway in C. elegans epidermal wound healing. See also Figure S5E.

To test whether RHO-1 was sensitive to ROS, we treated RHO-1(WT) or RHO-1(C16A) overexpressing worms with the pro-oxidant PQ. 2 h treatment of 1 mM PQ did not affect the ability of WT or RHO-1(C16A) to inhibit wound closure or F-actin accumulation (Figure 7C,F,G). However, PQ treatment suppressed the ability of RHO-1(C20A) to inhibit wound closure or F-actin accumulation (Figure 7C,F,G), suggesting RHO-1(C20A) is sensitive to ROS due to the presence of C16 in the redox sensitive motif (Figure 7B). The level of overexpression of RHO-1(WT) may be such that 1 mM PQ treatment is insufficient to inhibit its activity. Taken together, these results are consistent with mtROS acting via the redox-sensitive motif in RHO-1 to locally reduce its activity and promote wound closure.

DISCUSSION

We have shown here that mitochondrial ROS play protective roles in skin wound repair in vivo (Figure 7H). We find that C. elegans epidermal wounding triggers rapid local production of mtROS following a wound-induced Ca2+ influx and MCU/MCU-1 mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Elevated mtROS levels are sufficient to promote wound repair and organismal survival in mutants defective in repair, in part by regulating RHO-1-dependent actin remodeling at wound sites. Conversely, inhibition of mtROS by antioxidant treatment blocks wound closure. In mammals, tissue injury releases mitochondrial ‘damage-associated molecular patterns’ that activate innate immune responses (Zhang et al., 2010), and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation regulates repair of multiple tissues, including the epidermis (Shyh-Chang et al., 2013). Thus, mitochondria play diverse roles in tissue repair after damage.

Extracellular ROS, such as H2O2, are now established as key wound-generated signals mediating chemoattraction of migratory phagocytic cells (van der Vliet and Janssen-Heininger, 2014), but few studies have directly assessed the contribution of mtROS to wound repair. Superoxide levels have been shown to increase at mammalian skin wounds (Roy et al., 2006), but the significance of this observation has not been explored. Recently, mtROS have been shown to regulate actomyosin in Drosophila dorsal closure (Muliyil and Narasimha, 2014), a developmental process analogous to aspects of wound healing. Our results demonstrate mtROS promote efficient healing of wounds in a mature barrier epithelium. We find that wounding first inhibits then elevates mitoflashes close to the wound site. Given the time courses of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and mitoflashes after wounding, we propose that the initial Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria transiently inhibits mtROS production until excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ causes opening of the mPTP.

ROS are generated by multiple processes and enzymes, such as NADPH oxidases (Nox and dual oxidases) in the plasma membrane, lipid metabolism in peroxisomes, and cytosolic enzymes such as cyclooxygenases (Lambeth, 2004). However, in nonpathological conditions most cellular ROS (~ 90%) are generated by mitochondria (Balaban et al., 2005). mtROS such as superoxide are thought to be short-lived in vivo (Lambeth and Neish, 2014), being converted to more-stable species such as H2O2. Our analysis would suggest that H2O2 plays a mildly inhibitory role in actin-based wound repair, and that the protective effects of mtROS are unlikely to be mediated by H2O2. As C. elegans lacks migratory phagocytic cells, the need for extracellular ROS such as H2O2 may be less critical. Nevertheless oxidase-generated H2O2 or other ROS might play extracellular antimicrobial roles in C. elegans, in parallel to the intracellular mtROS pathway described here (Suzuki and Mittler, 2012).

We have provided evidence that mtROS promotes wound closure by local inhibition of the RHO-1 small GTPase. Rho family GTPases are key regulators of the actin cytoskeleton (Burridge and Wennerberg, 2004) and have been extensively analyzed in actomyosin based wound repair (Sonnemann and Bement, 2011; Wood et al., 2002). Our findings are consistent with mtROS signals inhibiting RHO-1 after wounding, thus promoting wound repair. ROS can modulate protein activity directly by oxidation of Cys residues (Miki and Funato, 2012). We find that the RHO-1 Cys-16 residue in its redox-sensitive motif is important for its ability to respond to mtROS in wound closure. These findings do not rule out the possibility that RHO-1 may also be regulated indirectly via other redox-sensitive regulators (Muliyil and Narasimha, 2014; Nimnual et al., 2003).

Collectively, our results reveal a protective role for mtROS signaling in intracellular wound repair. ROS are increasingly viewed as beneficial signals in wound repair. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has long been used to accelerate wound repair in chronic or refractory diabetic wounds, and is thought to act in part by increasing ROS and oxidative stress, inducing a protective response (Sen, 2009; Thom, 2009). Manipulation of mitochondrially generated ROS may be of interest in therapies for enhancing cellular or tissue repair.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

C. elegans genetics and transgenes

All C. elegans strains were grown at 20-22.5 °C on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with E. coli OP50. New strains were constructed using standard procedures, and all genotypes confirmed by PCR or sequencing. Previously described mutants used include: gtl-2(n2618)(lf), gtl-2(tm1463)(0), isp-1(qm150), mev-1(kn1), sod-1(tm776), sod-2(gk257), sod-2(ok1030), sod-3(tm760), sod-4(gk101), sod-5(tm1146), nuo-6(qm200), clk-1(qm30), tir-1(tm3036).

cpYFP was obtained from Dr. Wang Wang (University of Washington). Superecliptic pHluorin was obtained from Dr. Jeremy Dittman (Weill Cornell Medical College). We constructed Pcol-19-mito::cpYFP (pCZ820) and Pcol-19-mito::pHluorin (pCZ831) using Gibson assembly cloning (Gibson et al., 2009) to fuse cpYFP or pHluorin to the mitochondrial matrix target sequence of cox8, under the control of the col-19 promoter. Primer sequences are available on request. HyPer2 (Markvicheva et al., 2011) was generated from HyPer (Evrogen) by introducing the A406V mutation by QuikChange™ Site-Directed mutagenesis. Other plasmids were constructed using Gateway cloning. All transgenes and plasmids used are listed in Table S1. A single copy insertion of mito::GCaMP5(juSi103) was made by MosSCI using strain EG6701 following standard methods (Frokjaer-Jensen et al., 2012; Frokjaer-Jensen et al., 2008)

Needle wounding, wound closure and survival assays

We wounded animals with single stabs of a microinjection needle to the either anterior or posterior body of lateral hyp7 (avoiding the gonad) 24 h after L4 stage, essentially as described (Pujol et al., 2008). Wound closure and survival assays were performed as described (Xu and Chisholm, 2011). Except in Figure S2E, S3B, S4G, WT actin ring diameter was normalized to 1 and other conditions normalized to WT. To quantify GFP::moesin intensity (F0), the average fluorescence of 10 ROIs (10 × 10 pixels) on actin around wounds (FW) was measured and the average fluorescence of 10 equivalent ROIs in an unwounded region (FUW) subtracted.

Quantitation of mito::cpYFP fluorescence

To image mito::cpYFP fluorescence by spinning disk confocal microscopy we used a 491 nm excitation laser and collected emission using a 525/50 nm band pass filter. To analyze cpYFP flash dynamics, mito::cpYFP fluorescence images were taken every 2 s for 200 frames. Baseline fluorescence (F0) of mito::cpYFP was obtained by averaging fluorescence in 10 ROIs in the epidermal mitochondria then subtracting the average of 10 ROIs in the background before injury. The cpYFP flash amplitude ΔF/F0 was expressed as the ratio of change with respect to the baseline [(Ft-F0)/F0]. Recordings were made at 22°C. mito::GFP, mito::pHluorin and mito::HyPer2 fluorescence were imaged and quantitated in the same way except that mito::HyPer2 fluorescence was excited sequentially using 405 nm and 491 nm lasers and emission acquired using the 525/50 band-pass filter. As CFP405 did not show any change after wounding we only show YFP491 fluorescence in Figure S1C,D.

To visualize mitoflashes we first generated subtraction images comparing each frame with the preceding frame using MetaMorph. To quantitate mitoflashes, we manually counted flashes over 5 min in unwounded or wounded worms. A single mitoflash was defined as an increase in cpYFP fluorescence of ΔF/F0 > 0.5 in at least 2 consecutive frames. Heat maps and surface plots were generated using ImageJ.

Drug treatment and RNAi

OP50 bacteria were seeded onto NGM plates and allowed to grow overnight at 37°C. All drugs were added to the bacterial lawn from a high concentration stock and allowed to dry for 1-2 h at room temperature. DPI (Sigma D2926), EUK-134 (Cayman Chemical 10006329) and Rotenone (Sigma R8875) were dissolved in DMSO to make 500 mM, 30 mM, 24 mM, and 40 mM stock solutions, respectively. mitoTempo (Sigma, SML0737), Triphenylphosphonium chloride (TPP, Sigma 675121), Paraquat Dichloride (PQ, Sigma 36541), N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC, Sigma A7250) were dissolved in ddH2O to make 500 mM stocks; tBOOH (Sigma, Luperox TBH70X) stock was 70% in ddH2O. Antimycin A (Sigma A8674) was dissolved in ethanol as 25 mg/ml stock. For chronic treatment, L4 worms were transferred from normal NGM plates to drug plates for overnight before assaying wound repair or mitochondrial responses. For acute drug treatments (e.g. PQ treatment in Figure 2E and Figure 6C), young adults were transferred to freshly made drug plates 1-2 h at room temperature before needle wounding. RNAi was carried out as described (Xu and Chisholm, 2011). For imaging the effects of mitoTempo on mitoflashes adults were incubated on 0.1 mM mitoTempo or TPP plates for 2 h and transferred to 2 μl 12 mM levamisole with 0.1 mM mitoTempo or TPP agar pads for imaging and wounding.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and imaging

To analyze mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, we wounded animals using femtosecond laser irradiation, essentially as in C. elegans laser axotomy (Wu et al., 2007) except with 2 × 500 ms pulses. We acquired images using the spinning disk confocal in burst mode with 491 nm excitation using a 100x objective (Zeiss PlanApo, NA 1.46). To quantitate Ca2+ uptake, we measured average fluorescence in twenty equivalent regions of interest (ROI, 10 ×10 pixel), ten centered on a single mitochondrion and ten in the background. Baseline fluorescence (F0) was obtained by averaging fluorescence in 10 ROIs in the epidermal mitochondria then subtracting the average of 10 ROIs in the background before wounding. The change in fluorescence ΔF was expressed as the ratio of change with respect to the baseline [(Ft-F0)/F0]. To follow ΔF/F0 over time at different distances from the wound site we imaged using the 63x objective and drew ROI at intervals of 20 or 50 μm from the wound site.

CRISPR mediated deletion using dual sgRNAs

We generated a mcu-1 deletion using CRISPR/Cas9 (Friedland et al., 2013). To targeta deletion of most of the mcu-1 gene, we designed two sgRNAs: 1. GTTTCGAATATCCATCTGCT, 2. GATCCGATTGTGTCACTGAG. pU6::mcu-1 sgRNAs were generated by Gibson assembly and injected into N2 worms using standard methods, in mixtures composed of 40 ng/μl of each pU6::mcu-1 sgRNA, 100 ng/μl of Peft-3::Cas9-SV40 NLS::tbb-2-3’UTR and 20 ng/μl of Pcol-19-GFP as co-injection marker. Among 48 F1 GFP-positive worms we identified 1 animal heterozygous for the mcu-1 deletion ju1154. mcu-1(ju1154) animals are homozygous viable and contain an 821 bp deletion with breakpoints in exon 2 (CCGCT^CAGTGA) and in intron 5 (TTTTCT^GAAA).

RHO-1 mutant overexpression

Pcol-19-RHO-1 constructs were made using Gateway cloning. A rho-1 cDNA was isolated from N2 RNA and inserted into pCR8 using following primers: AC3542: ATGGCTGCGATTAGAAAGAAG, AC3543: CTACAAAATCATGCACTTGCTCTTC. All Pcol-19-RHO-1 mutations were generated using QuikChange™ Site-Directed mutagenesis. Pcol-19-RHO-1 and RHO-1 mutants were injected into CZ14748 (GFP::moesin strain) at 10 ng/μl with co-injection marker Punc-122-RFP (labeling coelomocytes) at 50 ng/μl. For each transgene, three lines were analyzed and data combined for statistical analysis.

Imaging the Rho sensor eGFP-rGBD

eGFP-rGBD (Benink and Bement, 2005) contains the Rho-binding domain of Rhotekin fused to eGFP and was a kind gift of Dr. William Bement (University of Wisconsin). Young adult worms were anesthetized with 12 mM levamisole on pads of 2% agar and their epidermis wounded using femtosecond laser irradiation as described above. To quantitate eGFP-rGBD fluorescence intensity post-wounding, we randomly chose 10 equivalent regions of interest (ROI, 10 pixel × 10 pixel) near the wound site (activation zone defined as within 1-2 μm of the wound) and in the background. Baseline fluorescence (F0) is the average of fluorescence in 10 ROIs before wounding. Fluorescence change ΔF was calculated as [(Ft-F0)/F0].

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA). Two-way comparisons used Student's t-test, or Fisher's exact test for proportions. For multiple comparisons we used one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett or Bonferroni post test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Chisholm and Jin labs for help and support. We thank Zhiping Wang for discussions on CRISPR. We thank Jonathan Ewbank, Nathalie Pujol, Yishi Jin, Bill McGinnis, and Emily Troemel for comments. We thank Wang Wang, Bill Bement, Jeremy Dittman, and Alex van der Bliek for clones and strains. Deletion mutations were generated by the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium and by the Japan National Bioresource Project. Some mutations were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). Supported by NIH R01 GM054657 to A.D.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Babior BM. Oxygen-dependent microbial killing by phagocytes (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1978;298:659–668. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803232981205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman JM, Perocchi F, Girgis HS, Plovanich M, Belcher-Timme CA, Sancak Y, Bao XR, Strittmatter L, Goldberger O, Bogorad RL, et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belousov VV, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov KA, Staroverov DB, Shakhbazov KS, Terskikh AV, Lukyanov S. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat Methods. 2006;3:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nmeth866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bement WM, Mandato CA, Kirsch MN. Wound-induced assembly and closure of an actomyosin purse string in Xenopus oocytes. Curr Biol. 1999;9:579–587. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benink HA, Bement WM. Concentric zones of active RhoA and Cdc42 around single cell wounds. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:429–439. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi P. The permeability transition pore. Control points of a cyclosporin A-sensitive mitochondrial channel involved in cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1275:5–9. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekemeier KM, Dempsey ME, Pfeiffer DR. Cyclosporin A is a potent inhibitor of the inner membrane permeability transition in liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7826–7830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C817–833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Wennerberg K. Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell. 2004;116:167–179. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bus JS, Gibson JE. Paraquat: model for oxidant-initiated toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1984;55:37–46. doi: 10.1289/ehp.845537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11715–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez V, Mohri-Shiomi A, Garsin DA. Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generates reactive oxygen species as a protective innate immune mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4983–4989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00627-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm AD, Hsiao TI. The Caenorhabditis elegans epidermis as a model skin. I: development, patterning, and growth. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2012;1:861–878. doi: 10.1002/wdev.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG, Miller AL, Vaughan E, Yu HY, Penkert R, Bement WM. Integration of single and multicellular wound responses. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1389–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro JV, Jacinto A. The role of transcription-independent damage signals in the initiation of epithelial wound healing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:249–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:504–511. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan R, McElwee JJ, Matthijssens F, Walker GA, Houthoofd K, Back P, Matscheski A, Vanfleteren JR, Gems D. Against the oxidative damage theory of aging: superoxide dismutases protect against oxidative stress but have little or no effect on life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3236–3241. doi: 10.1101/gad.504808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland AE, Tzur YB, Esvelt KM, Colaiacovo MP, Church GM, Calarco JA. Heritable genome editing in C. elegans via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Methods. 2013;10:741–743. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer-Jensen C, Davis MW, Ailion M, Jorgensen EM. Improved Mos1-mediated transgenesis in C. elegans. Nat Methods. 2012;9:117–118. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer-Jensen C, Davis MW, Hopkins CE, Newman BJ, Thummel JM, Olesen SP, Grunnet M, Jorgensen EM. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/ng.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galko MJ, Krasnow MA. Cellular and genetic analysis of wound healing in Drosophila larvae. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hekimi S, Lapointe J, Wen Y. Taking a “good” look at free radicals in the aging process. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J, Campbell SL. Mechanism of redox-mediated guanine nucleotide exchange on redox-active Rho GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31003–31010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J, Raines KW, Mocanu V, Campbell SL. Redox regulation of RhoA. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14481–14489. doi: 10.1021/bi0610101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y, Tanaka M, Honda S. Modulation of longevity and diapause by redox regulation mechanisms under the insulin-like signaling control in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:520–529. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Ouyang X, Wan R, Cheng H, Mattson MP, Cheng A. Mitochondrial superoxide production negatively regulates neural progenitor proliferation and cerebral cortical development. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2535–2547. doi: 10.1002/stem.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Zhang W, Fang H, Zheng M, Wang X, Xu J, Cheng H, Gong G, Wang W, Dirksen RT, et al. Response to “A critical evaluation of cpYFP as a probe for superoxide”. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1937–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D, Nehrke K. Mitochondrial fragmentation leads to intracellular acidification in Caenorhabditis elegans and mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2191–2201. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-10-0874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth JD, Neish AS. Nox enzymes and new thinking on reactive oxygen: a double-edged sword revisited. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown AB. Calcium: a potential central regulator in wound healing in the skin. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10:271–285. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.10502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Hwang AB, Kenyon C. Inhibition of respiration extends C. elegans life span via reactive oxygen species that increase HIF-1 activity. Curr Biol. 2010;20:2131–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love NR, Chen Y, Ishibashi S, Kritsiligkou P, Lea R, Koh Y, Gallop JL, Dorey K, Amaya E. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species are required for successful Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:222–228. doi: 10.1038/ncb2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace KA, Pearson JC, McGinnis W. An epidermal barrier wound repair pathway in Drosophila is mediated by grainy head. Science. 2005;308:381–385. doi: 10.1126/science.1107573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markvicheva KN, Bilan DS, Mishina NM, Gorokhovatsky AY, Vinokurov LM, Lukyanov S, Belousov VV. A genetically encoded sensor for H2O2 with expanded dynamic range. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P. Wound healing--aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, Gill MS, Walker DW, Clayton PE, Wallace DC, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR, Lithgow GJ. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H, Funato Y. Regulation of intracellular signalling through cysteine oxidation by reactive oxygen species. J Biochem. 2012;151:255–261. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L, Hobbs GA, Aghajanian A, Campbell SL. Redox regulation of Ras and Rho GTPases: mechanism and function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:250–258. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muliyil S, Narasimha M. Mitochondrial ROS regulates cytoskeletal and mitochondrial remodeling to tune cell and tissue dynamics in a model for wound healing. Dev Cell. 2014;28:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murawala P, Tanaka EM, Currie JD. Regeneration: the ultimate example of wound healing. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:954–962. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459:996–999. doi: 10.1038/nature08119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimnual AS, Taylor LJ, Bar-Sagi D. Redox-dependent downregulation of Rho by Rac. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:236–241. doi: 10.1038/ncb938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol N, Cypowyj S, Ziegler K, Millet A, Astrain A, Goncharov A, Jin Y, Chisholm AD, Ewbank JJ. Distinct innate immune responses to infection and wounding in the C. elegans epidermis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasola A, Bernardi P. Mitochondrial permeability transition in Ca2+-dependent apoptosis and necrosis. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzell W, Evans IR, Martin P, Wood W. Calcium Flashes Orchestrate the Wound Inflammatory Response through DUOX Activation and Hydrogen Peroxide Release. Curr Biol. 2013;23:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzell W, Wood W, Martin P. Recapitulation of morphogenetic cell shape changes enables wound re-epithelialisation. Development. 2014;141:1814–1820. doi: 10.1242/dev.107045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:566–578. doi: 10.1038/nrm3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Khanna S, Nallu K, Hunt TK, Sen CK. Dermal wound healing is subject to redox control. Molecular therapy. 2006;13:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schebesta M, Lien CL, Engel FB, Keating MT. Transcriptional profiling of caudal fin regeneration in zebrafish. ScientificWorldJournal 6 Suppl. 2006;1:38–54. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzlander M, Murphy MP, Duchen MR, Logan DC, Fricker MD, Halestrap AP, Muller FL, Rizzuto R, Dick TP, Meyer AJ, et al. Mitochondrial 'flashes': a radical concept repHined. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen CK. Wound healing essentials: let there be oxygen. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo-Matsuda N, Yasuda K, Tsuda M, Ohkubo T, Yoshimura S, Nakazawa H, Hartman PS, Ishii N. A defect in the cytochrome b large subunit in complex II causes both superoxide anion overproduction and abnormal energy metabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41553–41558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen EZ, Song CQ, Lin Y, Zhang WH, Su PF, Liu WY, Zhang P, Xu J, Lin N, Zhan C, et al. Mitoflash frequency in early adulthood predicts lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2014;508:128–132. doi: 10.1038/nature13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyh-Chang N, Zhu H, Yvanka de Soysa T, Shinoda G, Seligson MT, Tsanov KM, Nguyen L, Asara JM, Cantley LC, Daley GQ. Lin28 enhances tissue repair by reprogramming cellular metabolism. Cell. 2013;155:778–792. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipos P, Gyory H, Hagymasi K, Ondrejka P, Blazovics A. Special wound healing methods used in ancient egypt and the mythological background. World J Surg. 2004;28:211–216. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnemann KJ, Bement WM. Wound repair: toward understanding and integration of single-cell and multicellular wound responses. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:237–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species-dependent wound responses in animals and plants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:2269–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom SR. Oxidative stress is fundamental to hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;106:988–995. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91004.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting SB, Caddy J, Hislop N, Wilanowski T, Auden A, Zhao LL, Ellis S, Kaur P, Uchida Y, Holleran WM, et al. A homolog of Drosophila grainy head is essential for epidermal integrity in mice. Science. 2005;308:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1107511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PO, Hinman LE, Unger GM, Sammak PJ. A wound-induced [Ca2+]i increase and its transcriptional activation of immediate early genes is important in the regulation of motility. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:319–326. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullet JM, Hertweck M, An JH, Baker J, Hwang JY, Liu S, Oliveira RP, Baumeister R, Blackwell TK. Direct inhibition of the longevity-promoting factor SKN-1 by insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. Cell. 2008;132:1025–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger YM. Hydrogen peroxide as a damage signal in tissue injury and inflammation: murderer, mediator, or messenger? J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:427–435. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk JM, Hekimi S. Superoxide dismutase is dispensable for normal animal lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5785–5790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116158109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ved R, Saha S, Westlund B, Perier C, Burnam L, Sluder A, Hoener M, Rodrigues CM, Alfonso A, Steer C, et al. Similar patterns of mitochondrial vulnerability and rescue induced by genetic modification of alpha-synuclein, parkin, and DJ-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42655–42668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505910200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Fang H, Groom L, Cheng A, Zhang W, Liu J, Wang X, Li K, Han P, Zheng M, et al. Superoxide flashes in single mitochondria. Cell. 2008;134:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei-LaPierre L, Gong G, Gerstner BJ, Ducreux S, Yule DI, Pouvreau S, Wang X, Sheu SS, Cheng H, Dirksen RT, et al. Respective contribution of mitochondrial superoxide and pH to mitochondria-targeted circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (mt-cpYFP) flash activity. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10567–10577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AP, Brodsky IE, Rahner C, Woo DK, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Walsh MC, Choi Y, Shadel GS, Ghosh S. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2011;472:476–480. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Redox reactions and microbial killing in the neutrophil phagosome. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:642–660. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W, Jacinto A, Grose R, Woolner S, Gale J, Wilson C, Martin P. Wound healing recapitulates morphogenesis in Drosophila embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:907–912. doi: 10.1038/ncb875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Ghosh-Roy A, Yanik MF, Zhang JZ, Jin Y, Chisholm AD. Caenorhabditis elegans neuronal regeneration is influenced by life stage, ephrin signaling, and synaptic branching. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15132–15137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Chisholm AD. A Gαq-Ca(2)(+) signaling pathway promotes actin-mediated epidermal wound closure in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1960–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Hekimi S. A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Li J, Hekimi S. A Measurable increase in oxidative damage due to reduction in superoxide detoxification fails to shorten the life span of long-lived mitochondrial mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2007;177:2063–2074. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SK, Freisinger CM, LeBert DC, Huttenlocher A. Early redox, Src family kinase, and calcium signaling integrate wound responses and tissue regeneration in zebrafish. J Cell Biol. 2012;199:225–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SK, Starnes TW, Deng Q, Huttenlocher A. Lyn is a redox sensor that mediates leukocyte wound attraction in vivo. Nature. 2011;480:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature10632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.