Abstract

Retinoic acid (RA) generated in the mesoderm of vertebrate embryos controls body axis extension by downregulating Fgf8 expression in cells exiting the caudal progenitor zone. RA activates transcription by binding to nuclear RA receptors (RARs) at RA response elements (RAREs), but it is unknown whether RA can directly repress transcription. Here, we analyzed a conserved RARE upstream of Fgf8 that binds RAR isoforms in mouse embryos. Transgenic embryos carrying Fgf8 fused to lacZ exhibited expression similar to caudal Fgf8, but deletion of the RARE resulted in ectopic trunk expression extending into somites and neuroectoderm. Epigenetic analysis using chromatin immunoprecipitation of trunk tissues from E8.25 wild-type and Raldh2−/− embryos lacking RA synthesis revealed RA-dependent recruitment of the repressive histone marker H3K27me3 and polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) near the Fgf8 RARE. The co-regulator RERE, the loss of which results in ectopic Fgf8 expression and somite defects, was recruited near the RARb RARE by RA, but was released from the Fgf8 RARE by RA. Our findings demonstrate that RA directly represses Fgf8 through a RARE-mediated mechanism that promotes repressive chromatin, thus providing valuable insight into the mechanism of RA-FGF antagonism during progenitor cell differentiation.

Keywords: Body axis extension, Somitogenesis, Neurogenesis, Ligand-induced repression, Retinoic acid, Raldh2, Fgf8, PRC2, RERE

INTRODUCTION

Vertebrate embryos develop in a head-to-tail fashion by extension of the body axis from a caudal progenitor zone containing axial stem cells that generate neuroectoderm and presomitic mesoderm (Tzouanacou et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2009; Takemoto et al., 2011). Somitogenesis is a developmental process in which presomitic mesoderm exiting the caudal progenitor zone is sequentially segmented to form somites that later generate vertebrae and skeletal muscles (Dequéant and Pourquié, 2008). The location of segmentation lies just anterior to the expression domains of fibroblast growth factor 4 (Fgf4) and fibroblast growth factor 8 (Fgf8) in the caudal progenitor zone (Naiche et al., 2011; Boulet and Capecchi, 2012) in a region where fibroblast growth factor (FGF) activity is too low to maintain random cell migration, thus allowing epithelial condensation of presomitic mesoderm to form somites (Bénazéraf et al., 2010). Whereas FGF8 is required to position the somite front, ectopic administration of FGF8 to one side of chick embryos has been shown to inhibit somite formation on that side (Dubrulle et al., 2001). Alterations in the level of FGF signaling during embryogenesis have been linked to the etiology of congenital scoliosis, which is characterized by a lateral curvature of the spine caused by vertebral defects (Sparrow et al., 2012).

Retinoic acid (RA) produced by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (Raldh2; Aldh1a2) functions as a diffusible signal controlling vertebrate development (Duester, 2008; Niederreither and Dollé, 2008). Loss of RA synthesis in RA-deficient chick embryos and mouse Raldh2−/− embryos results in ectopic Fgf8 expression extending from the caudal progenitor zone into the trunk that disrupts somitogenesis and neurogenesis (Diez del Corral et al., 2003; Molotkova et al., 2005; Vermot et al., 2005; Vermot and Pourquié, 2005; Sirbu and Duester, 2006) as well as forelimb initiation (Zhao et al., 2009; Cunningham et al., 2013). Thus, RA functions as a diffusible signal that downregulates Fgf8 as cells exit the caudal progenitor zone. However, the mechanism through which RA downregulates caudal Fgf8 expression is unknown. Some clues have come from mutational studies on Rere encoding the transcriptional co-regulator RERE, a member of the Atrophin family of nuclear receptor co-regulators (Wang and Tsai, 2008); Rere mutants exhibited somite left-right asymmetry and asymmetric Fgf8 expression (Vilhais-Neto et al., 2010). Furthermore, previous studies tracking the position of the Fgf8 locus within the nucleus in the caudal progenitor zone and neural tube showed that it becomes more peripheral in the neural tube (a location associated with repression); however, this shift to the nuclear periphery was not observed in Raldh2−/− neural tube and was regulated by FGF signaling (Patel et al., 2013).

Signal-induced repression has been suggested to play a major role in developmental signaling (Affolter et al., 2008), but such a role for RA signaling has not been established. RA functions as a ligand for widely expressed nuclear RA receptors that bind as RAR/RXR heterodimers to RA response elements (RAREs) near target genes (Duester, 2008; Niederreither and Dollé, 2008). Although RAREs clearly control gene activation, relatively little is known about RA repression. Here, mutational and epigenetic studies were performed to investigate the biological function of a RARE upstream of Fgf8.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

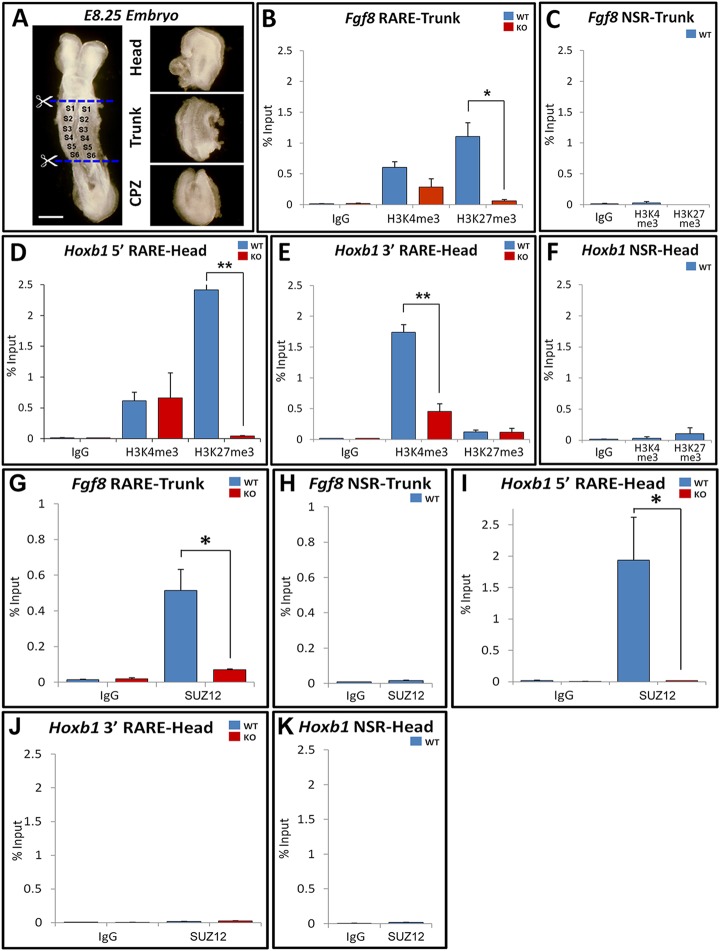

Conserved RARE upstream of Fgf8

We investigated whether RA restriction of caudal Fgf8 expression is mediated by direct transcriptional regulation. Sequence comparisons identified a conserved RARE near the human, mouse, rat and chick Fgf8 genes located 4.1-4.5 kb upstream of the promoter for mammals and 3.2 kb upstream for chick (Fig. 1A). The Fgf8 RAREs all include the sequence AGTTCA in the downstream half-site, which is the most efficient variant for controlling RAR-binding specificity (Phan et al., 2010). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of E8.25 (5-8 somite) whole mouse embryos revealed that the mouse Fgf8 RARE recruits all three RAR isoforms (Fig. 1A). We also performed ChIP on the 5′- and 3′-Hoxb1 RAREs that are required for Hoxb1 repression (Studer et al., 1994) and activation (Marshall et al., 1994), respectively, in different hindbrain domains at E8.25. The 5′-Hoxb1 RARE represses Hoxb1 in rhombomeres 3 and 5, but the mechanism of this repressive RARE remains unknown. Both the 5′- and 3′-Hoxb1 RAREs were able to recruit all three RARs (Fig. 1B). To further examine RAR binding to the Fgf8 RARE, we demonstrated that the wild-type (WT) Fgf8 RARE, but not a mutant version, binds RARs. For this, we used electrophoretic mobility shift assays with nuclear extracts from E8.25 mouse embryos and super-shift studies with RAR antibodies (supplementary material Fig. S1). These findings indicate that Fgf8 and Hoxb1 RAREs are capable of responding to RA signaling in mouse embryonic tissues at a stage when these genes are normally regulated by RA.

Fig. 1.

RAREs near Fgf8 and Hoxb1 bind RARs in mouse embryos. (A) Mouse Fgf8 RARE and alignment of sequences showing a highly conserved Fgf8 RARE; consensus RARE sequence is shown (Balmer and Blomhoff, 2005). (B) Hoxb1 gene harboring a repressive 5′-RARE and an activating 3′-RARE. ChIP was performed using chromatin from pooled E8.25 WT whole mouse embryos and antibodies against RAR isoforms or IgG (control); input DNA (diluted 100-fold) and immunoprecipitated DNA were analyzed by PCR using primers for the RAREs or for nonspecific regions (NSR) indicated by arrows. IP, immunoprecipitation; M, molecular size markers.

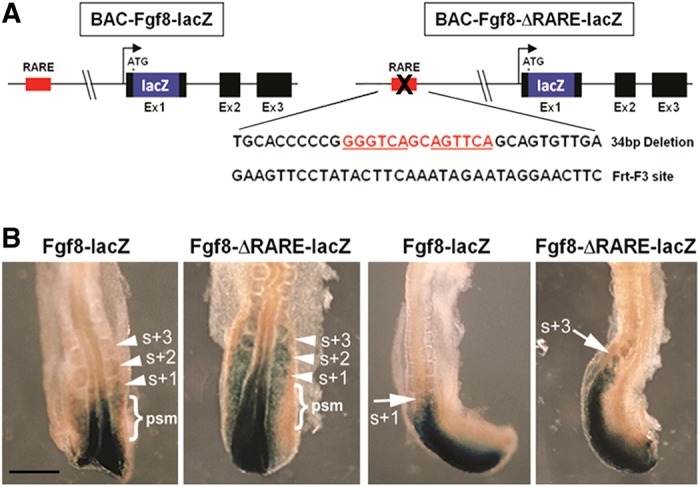

RA directly represses caudal Fgf8 transcription through an upstream RARE

Using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) recombination-mediated genetic engineering (recombineering), we fused the E. coli lacZ gene in frame with the ATG start codon of mouse Fgf8 (contained in a 200.9 kb BAC) to create Fgf8-lacZ (Fig. 2A); the BAC used contains elements known to stimulate caudal Fgf8 expression (Marinić et al., 2013). Further recombineering was performed to delete the Fgf8 RARE located at −4.1 kb, replacing it with the 34 bp sequence of the FRT-F3 site used in recombineering to create Fgf8-ΔRARE-lacZ (Fig. 2A). Injection of Fgf8-lacZ into fertilized mouse oocytes resulted in expression at E8.5 consistent with normal caudal Fgf8 expression (Fig. 2B; n=3). By contrast, E8.5 embryos carrying Fgf8-ΔRARE-lacZ exhibited ectopic lacZ expression extending anteriorly into the three caudal-most somites and into the posterior neuroectoderm to the level of somite+2 (Fig. 2B; n=3). These observations indicate that the Fgf8 RARE is required in vivo for restriction of caudal Fgf8 expression, thus demonstrating that RA signaling directly represses Fgf8 transcription through a RARE-mediated mechanism. The observation that Fgf8-ΔRARE-lacZ expression does not expand anteriorly along the entire body axis suggests that RA operates only to restrict caudal Fgf8 transcription and that other mechanisms are responsible for the absence of Fgf8 expression in rostral regions.

Fig. 2.

RA directly represses caudal Fgf8 transcription through an upstream RARE. (A) BAC constructs used for generating Fgf8-lacZ and Fgf8-ΔRARE-lacZ transgenic embryos. Fgf8-ΔRARE-lacZ lacks the Fgf8 RARE, which was replaced by the 34 bp FRT-F3 site. (B) Transgenic 9-somite embryos carrying Fgf8-lacZ recapitulate endogenous caudal Fgf8 expression, whereas Fgf8-ΔRARE-lacZ exhibits ectopic expression in the three somites most recently generated (arrowheads, arrows) and presomitic mesoderm (psm; brackets). Left panels, dorsal view; right panels, lateral view. Scale bar: 100 µm.

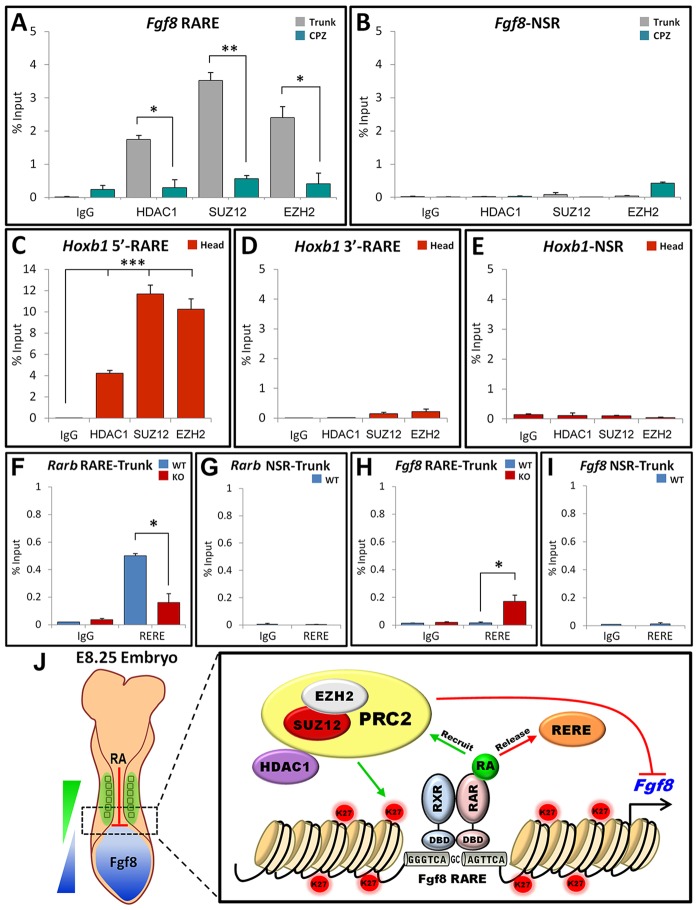

Histone methylation near Fgf8 RARE

Gene activation through RAREs functions through RA-dependent recruitment of transcriptional co-activators (Germain et al., 2002), but the mechanism through which RAREs repress transcription is unknown. Transcriptional repression is associated with histone-H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) catalyzed by polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), whereas transcriptional activation is linked with histone-H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) catalyzed by trithorax [lysine (K)-specific methyltransferase 2A – Mouse Genome Informatics] (Schuettengruber et al., 2007). For regional ChIP assays, WT embryos and Raldh2−/− embryos (lacking RA synthesis) collected at E8.25 (5-8 somites) were dissected into head, trunk and caudal progenitor zone (CPZ) regions (Fig. 3A). For pooled WT trunks, in which Fgf8 is normally not expressed, we found a significant enrichment of the repressive H3K27me3 mark near the Fgf8 RARE compared with the activating H3K4me3 mark (Fig. 3B). Importantly, enrichment of H3K27me3 near the Fgf8 RARE was reduced more than 15-fold in Raldh2−/− trunks lacking RA activity (Fig. 3B,C). As a control, ChIP analysis on pooled heads revealed that the 3′-Hoxb1 RARE required for gene activation exhibited much higher enrichment for H3K4me3 compared with H3K27me3, whereas the 5′-Hoxb1 RARE required for gene repression displayed much higher enrichment for H3K27me3 compared with H3K4me3; in both cases, enrichment was highly dependent upon Raldh2 function needed for RA synthesis (Fig. 3D-F). Our demonstration that RA stimulates accumulation of repressive chromatin marks near the Fgf8 and 5′-Hoxb1 RAREs provides further evidence that these RAREs function repressively in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Histone methylation and PRC2 recruitment near Fgf8- and Hoxb1-repressive RAREs. (A) For regional ChIP assays, E8.25 embryos were divided into head, trunk and CPZ as shown by cutting just posterior to the heart to release the head/heart and just posterior to the last somite to separate the trunk and CPZ. Dorsal view. Scale bar: 100 µm. (B,C) ChIP assay using trunk chromatin from pooled WT or Raldh2–/– (KO) embryos showing effect of loss of RA on H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 marks near the Fgf8 RARE. (D-F) ChIP performed on head for H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 marks near the 5′-Hoxb1-repressive RARE and the 3′-Hoxb1-activating RARE. (G-K) ChIP to examine the recruitment of Suz12 near the Fgf8 RARE in trunk tissue or near the Hoxb1 RAREs in head tissue. Controls include ChIP assays with IgG and nonspecific region (NSR) primers located at least 1 kb from the RAREs; see Fig. 1 for location of ChIP primers. Data shown as percentage input, mean±s.e.m.; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (t-test).

RA-dependent recruitment of PRC2 near Fgf8 RARE

We examined whether RA recruits PRC2 that generates the H3K27me3 mark by performing ChIP for the PRC2 subunit SUZ12 (Gillespie and Gudas, 2007). In WT trunks we found a strong signal for enrichment of SUZ12 near the Fgf8 RARE, but this was greatly reduced in Raldh2−/− trunks lacking RA activity (Fig. 3G,H). The 5′-Hoxb1 RARE required for repression behaved similarly to the Fgf8 RARE, displaying greatly reduced binding of SUZ12 in Raldh2−/− head compared with wild type, whereas the 3′-Hoxb1 RARE did not recruit SUZ12 (Fig. 3I-K). These observations provide evidence that the Fgf8 and 5′-Hoxb1 RAREs control repression in vivo through RA-dependent recruitment of PRC2.

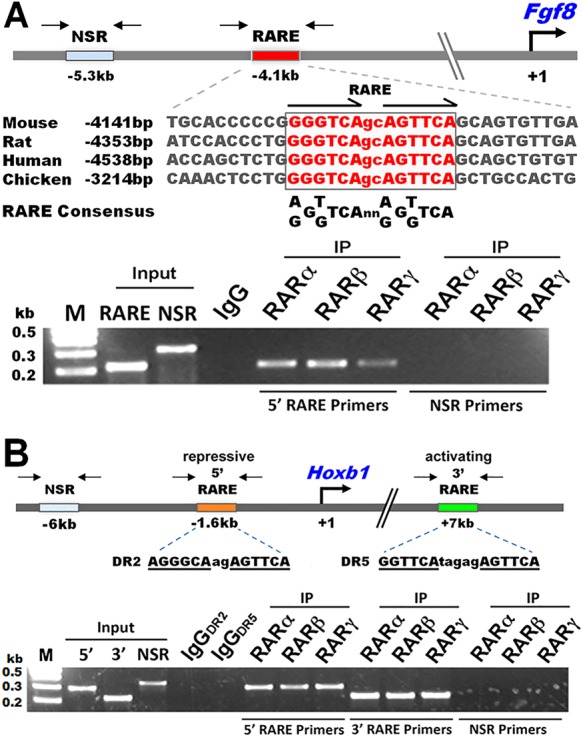

Regional recruitment of transcriptional repressors near Fgf8 RARE

We conducted ChIP assays to determine the relative regional occupancy of PRC2 components EZH2 and SUZ12, as well as the associated repressive factor histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), near the Fgf8 RARE in WT trunk and CPZ regions. HDAC1, EZH2 and SUZ12 were significantly enriched near the Fgf8 RARE in the trunk, where RA activity is high and Fgf8 expression is absent, but not in the CPZ, where RA activity is low and Fgf8 expression is high (Fig. 4A,B). ChIP performed on head tissue demonstrated a strong enrichment of HDAC1, EZH2 and SUZ12 near the repressive 5′-Hoxb1 RARE, but not near the activating 3′-Hoxb1 RARE (Fig. 4C-E). Taken together with our other findings, we conclude that the Fgf8 RARE functions in an RA-dependent and region-specific manner to repress Fgf8 transcription.

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of repressive Fgf8 RARE. (A-E) Regional ChIP assay from WT E8.25 embryos to examine recruitment of repressive proteins near Fgf8 and Hoxb1 RAREs. (F-I) ChIP assays showing recruitment of RERE to RARb and Fgf8 RAREs in WT or Raldh2−/− (KO) E8.25 trunk. See Fig. 3 legend for more details; data shown as percentage input, mean±s.e.m.; *P<0.05, **P<0.001, ***P<0.0001 (t-test). (J) Model for direct RA repression of caudal Fgf8 transcription through a RARE. Opposing gradients of RA and FGF8 along the body axis are shown. RA recruits a repressor complex near the Fgf8 RARE, containing PRC2 (EZH2, SUZ12) and HDAC1, that stimulates deposition of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 (K27). RA also prevents binding of the co-regulator RERE near the Fgf8 RARE. DBD, DNA-binding domain; RAR, RA receptor; RXR, retinoid-X-receptor (heterodimer partner for RAR).

Localization of RERE during body axis extension

RERE is a nuclear receptor co-regulator that has been reported to function in mice as a co-repressor able to recruit HDAC1 (Zoltewicz et al., 2004; Wang and Tsai, 2008). Rere (om) mutant mice were found to exhibit somite left-right asymmetry and corresponding ectopic caudal Fgf8 expression on the right side (Vilhais-Neto et al., 2010). Rere(om);Raldh2−/− double mutants have a more severe somitogenesis defect than either single mutant, demonstrating a synergistic effect of these two mutations (Vilhais-Neto et al., 2010). Rere (om) mutants exhibit reduced RA activity (RARE-lacZ expression) and RERE binds RAR/RXR at a RARE near the RARb gene to activate transcription in response to RA. This suggests that RERE controls somite symmetry by functioning as an RA-dependent co-activator that increases the amount of RA receptors (Vilhais-Neto et al., 2010). Thus, RERE might act as either a co-repressor or co-activator, depending on the particular gene involved.

As Rere mutants exhibit ectopic caudal Fgf8 expression, we investigated whether RERE might function as a co-repressor for Fgf8. Previous studies in cell lines showed that RERE functions as a co-activator for RARb through binding to a RARE located near the RARb promoter at −57 bp (Vilhais-Neto et al., 2010). Here, ChIP studies showed that binding of RERE near the RARb RARE in WT trunks was reduced approximately 3-fold in Raldh2−/− trunks, providing in vivo confirmation of RA-dependent binding of RERE near the RARb RARE (Fig. 4F,G). RERE binding was very low near the Fgf8 RARE in WT trunks, but a significant enrichment (approximately 10-fold) was observed in Raldh2−/− trunks (Fig. 4H,I). Thus, our findings demonstrate RA-dependent recruitment of RERE near the RARb RARE and RA-dependent release of RERE near the Fgf8 RARE, thereby suggesting that RERE affects somitogenesis not only by upregulating RARb but also by directly regulating Fgf8.

The previous observation that Rere(om);Raldh2−/− double mutants exhibit a more severe somite defect than either single mutant (Vilhais-Neto et al., 2010) can probably not be explained by a further reduction of RA signaling in Rere(om);Raldh2−/− mutants compared with Raldh2−/− mutants, as Raldh2−/− mutants already have no detectable RA activity (Vermot et al., 2005; Sirbu and Duester, 2006). However, synergism might be explained by our observation that recruitment of RERE to the Fgf8 RARE is greatly increased in Raldh2−/− trunks. Thus, loss of RA signaling in Raldh2−/− embryos might not totally de-repress caudal Fgf8 transcription due to recruitment of RERE (functioning as a co-repressor) to the Fgf8 RARE. However, simultaneous loss of RA and RERE could then further de-repress caudal Fgf8, resulting in more severe defects. RERE binds near the Fgf8 RARE in a manner similar to how other nuclear receptor co-repressors, such as SMRT or NCoR1, bind RAR/RXR heterodimers at RAREs in the absence of RA but are released upon binding of RA to RAR (Perissi et al., 2010). However, as RERE can also function as a co-activator, the mechanism of RERE action might be different when RERE is bound at an activating RARE compared with a repressive RARE. Together with Rere(om);Raldh2−/− genetic studies, our findings suggest a model in which RA binding to RAR at the repressive Fgf8 RARE releases RERE (Fig. 4J). It is unclear whether release of RERE is directly related to RA-mediated recruitment of PRC2 to the vicinity of the Fgf8 RARE, but it appears probable that additional regulatory proteins are involved in recruitment of PRC2 for RA-mediated Fgf8 repression.

Conclusions

Although the existence of caudal RA-FGF8 antagonism as a fundamental mechanism needed for vertebrate body axis extension has been acknowledged for some time, the mechanism itself has remained elusive. Here, our deletion studies demonstrate that the RARE upstream of Fgf8 is required in vivo for repression of Fgf8 transcription at the border of the trunk and caudal progenitor zones. A repressive role for the Fgf8 RARE is further supported by our observation of RA-dependent recruitment of PRC2 and deposition of the repressive H3K27me3 mark to the vicinity of the Fgf8 RARE in trunk tissue (Fig. 4J). Our findings are consistent with the ability of RA to stimulate peripheral nuclear localization of Fgf8 (Patel et al., 2013), suggesting a mechanism involving recruitment of polycomb complexes (PRC1 and PRC2). These complexes are known to induce chromatin compaction (Francis et al., 2004; Eskeland et al., 2010) and are associated with gene repression of loci localized to the nuclear periphery (Finlan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Interestingly, the 5′-Hoxb1 RARE, previously shown in transgenic mouse studies to act in a repressive manner (Studer et al., 1994), was also found to recruit PRC2 and H3K27me3 in an RA-dependent manner. As the Fgf8- and 5′-Hoxb1-repressive RAREs have sequences similar to activating RAREs (Balmer and Blomhoff, 2005), we suggest that the ability of some RAREs to function repressively depends upon differences in RARE half-site spacing or upon other nearby cis sequences that affect chromatin architecture. The mechanisms controlling recruitment of polycomb to vertebrate genes are more complex than those in lower animals and are still being explored (Schorderet et al., 2013). Further studies designed to understand how RA recruits PRC2 to the repressive Fgf8 and 5′-Hoxb1 RAREs might provide additional clues to the mechanism of PRC2 recruitment in general.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Raldh2 null embryos

Raldh2−/− mice have been described previously (Sirbu and Duester, 2006). All mouse studies conformed to the regulatory standards adopted by the Animal Research Committee at the Sanford–Burnham Medical Research Institute.

Generation of Fgf8 BAC transgenic mouse embryos

A BAC clone RP23-208N3 (BACPAC Resources Center) containing 200.9 kb around the mouse Fgf8 locus was subjected to recombineering (Gene Bridges kit; Lee et al., 2001) to join lacZ (from pHsp68-lacZ; Vokes et al., 2008) in frame with the Fgf8 ATG start codon to create Fgf8-lacZ. To generate Fgf8-ΔRARE-lacZ, recombineering was used to replace the Fgf8 RARE with a 34 bp FRT-F3 site (Nagy et al., 2003). BACs were injected into pronuclei of FVB/N fertilized eggs. Embryos dissected at E8.5 were stained 18 h for β-galactosidase activity as described (Nagy et al., 2003). Further details are available in Table S1 and Methods in the supplementary material.

ChIP assay

ChIP was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Active Motif) as described (Frank et al., 2001). For regional ChIP assays, we used pooled head/heart, trunk and CPZ tissues from 67 WT or 67 Raldh2−/− E8.25 (5-8 somite) mouse embryos separated by cutting posterior to the heart and posterior to the last somite. Antibodies used include H3K4me3 (Active Motif, 39159), H3K27me3 (Active Motif, 39155), EZH2 (Active Motif, 39901), SUZ12 (Active Motif, 39357), HDAC1 (GeneTex, GTX100513), RERE (Abgent, AP9954a) or control IgG antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 2729). For whole-embryo ChIP, 28 pooled WT E8.25 mouse embryos were used with anti-RARα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-551), anti-RARγ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-550) or anti-RARβ (Affinity BioReagents, PA1-811). For all ChIP reactions, 3 µg antibody was added per 200 µl immunoprecipitation reaction. Further details are available in Table S1 and Methods in the supplementary material.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed on nuclear extracts from 32 pooled wild-type E8.25 embryos using biotin-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probes containing wild-type and mutant Fgf8 RARE sequences. Binding reactions were performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Pierce, Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Further details are available in Table S1 and Methods in the supplementary material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ling Wang in the Sanford–Burnham Transgenic Mouse Facility for BAC pronuclear injection and S. Vokes for providing pHsp68-lacZ and advice on recombineering.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

S.K. carried out the experiments. S.K. and G.D. designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health [GM062848 to G.D.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.112367/-/DC1

References

- Affolter M., Pyrowolakis G., Weiss A., Basler K. (2008). Signal-induced repression: the exception or the rule in developmental signaling? Dev. Cell 15, 11-22 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer J. E., Blomhoff R. (2005). A robust characterization of retinoic acid response elements based on a comparison of sites in three species. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 96, 347-354 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bénazéraf B., Francois P., Baker R. E., Denans N., Little C. D., Pourquié O. (2010). A random cell motility gradient downstream of FGF controls elongation of an amniote embryo. Nature 466, 248-252 10.1038/nature09151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet A. M., Capecchi M. R. (2012). Signaling by FGF4 and FGF8 is required for axial elongation of the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 371, 235-245 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham T. J., Zhao X., Sandell L. L., Evans S. M., Trainor P. A., Duester G. (2013). Antagonism between retinoic acid and fibroblast growth factor signaling during limb development. Cell Rep. 3, 1503-1511 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dequéant M. L., Pourquié O. (2008). Segmental patterning of the vertebrate embryonic axis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 370-382 10.1038/nrg2320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez del Corral R., Olivera-Martinez I., Goriely A., Gale E., Maden M., Storey K. (2003). Opposing FGF and retinoid pathways control ventral neural pattern, neuronal differentiation, and segmentation during body axis extension. Neuron 40, 65-79 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00565-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrulle J., McGrew M. J., Pourquié O. (2001). FGF signaling controls somite boundary position and regulates segmentation clock control of spatiotemporal Hox gene activation. Cell 106, 219-232 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00437-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duester G. (2008). Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell 134, 921-931 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskeland R., Leeb M., Grimes G. R., Kress C., Boyle S., Sproul D., Gilbert N., Fan Y., Skoultchi A. I., Wutz A., et al. (2010). Ring1B compacts chromatin structure and represses gene expression independent of histone ubiquitination. Mol. Cell 38, 452-464 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlan L. E., Sproul D., Thomson I., Boyle S., Kerr E., Perry P., Ylstra B., Chubb J. R., Bickmore W. A. (2008). Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000039 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis N. J., Kingston R. E., Woodcock C. L. (2004). Chromatin compaction by a polycomb group protein complex. Science 306, 1574-1577 10.1126/science.1100576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S. R., Schroeder M., Fernandez P., Taubert S., Amati B. (2001). Binding of c-Myc to chromatin mediates mitogen-induced acetylation of histone H4 and gene activation. Genes Dev. 15, 2069-2082 10.1101/gad.906601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain P., Iyer J., Zechel C., Gronemeyer H. (2002). Co-regulator recruitment and the mechanism of retinoic acid receptor synergy. Nature 415, 187-192 10.1038/415187a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie R. F., Gudas L. J. (2007). Retinoid regulated association of transcriptional co-regulators and the polycomb group protein SUZ12 with the retinoic acid response elements of Hoxa1, RARβ2, and Cyp26A1 in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 298-316 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.-C., Yu D., Martinez de Velasco J., Tessarollo L., Swing D. A., Court D. L., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G. (2001). A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics 73, 56-65 10.1006/geno.2000.6451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinić M., Aktas T., Ruf S., Spitz F. (2013). An integrated holo-enhancer unit defines tissue and gene specificity of the Fgf8 regulatory landscape. Dev. Cell 24, 530-542 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall H., Studer M., Pöpperl H., Aparicio S., Kuroiwa A., Brenner S., Krumlauf R. (1994). A conserved retinoic acid response element required for early expression of the homeobox gene Hoxb-1. Nature 370, 567-571 10.1038/370567a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molotkova N., Molotkov A., Sirbu I. O., Duester G. (2005). Requirement of mesodermal retinoic acid generated by Raldh2 for posterior neural transformation. Mech. Dev. 122, 145-155 10.1016/j.mod.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A., Gertsenstein M., Vintersten K., Behringer R. R. (2003). Manipulating the Mouse Embryo, 3rd edn Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naiche L. A., Holder N., Lewandoski M. (2011). FGF4 and FGF8 comprise the wavefront activity that controls somitogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4018-4023 10.1073/pnas.1007417108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K., Dollé P. (2008). Retinoic acid in development: towards an integrated view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 541-553 10.1038/nrg2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N. S., Rhinn M., Semprich C. I., Halley P. A., Dollé P., Bickmore W. A., Storey K. G. (2013). FGF signalling regulates chromatin organisation during neural differentiation via mechanisms that can be uncoupled from transcription. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003614 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V., Jepsen K., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (2010). Deconstructing repression: evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 109-123 10.1038/nrg2736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan T. Q., Jow M. M., Privalsky M. L. (2010). DNA recognition by thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors: 3,4,5 rule modified. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 319, 88-98 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorderet P., Lonfat N., Darbellay F., Tschopp P., Gitto S., Soshnikova N., Duboule D. (2013). A genetic approach to the recruitment of PRC2 at the HoxD locus. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003951 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettengruber B., Chourrout D., Vervoort M., Leblanc B., Cavalli G. (2007). Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell 128, 735-745 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirbu I. O., Duester G. (2006). Retinoic-acid signaling in node ectoderm and posterior neural plate directs left-right patterning of somitic mesoderm. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 271-277 10.1038/ncb1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow D. B., Chapman G., Smith A. J., Mattar M. Z., Major J. A., O'Reilly V. C., Saga Y., Zackai E. H., Dormans J. P., Alman B. A., et al. (2012). A mechanism for gene-environment interaction in the etiology of congenital scoliosis. Cell 149, 295-306 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer M., Popperl H., Marshall H., Kuroiwa A., Krumlauf R. (1994). Role of a conserved retinoic acid response element in rhombomere restriction of Hoxb-1. Science 265, 1728-1732 10.1126/science.7916164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto T., Uchikawa M., Yoshida M., Bell D. M., Lovell-Badge R., Papaioannou V. E., Kondoh H. (2011). Tbx6-dependent Sox2 regulation determines neural or mesodermal fate in axial stem cells. Nature 470, 394-398 10.1038/nature09729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzouanacou E., Wegener A., Wymeersch F. J., Wilson V., Nicolas J.-F. (2009). Redefining the progression of lineage segregations during mammalian embryogenesis by clonal analysis. Dev. Cell 17, 365-376 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermot J., Pourquié O. (2005). Retinoic acid coordinates somitogenesis and left-right patterning in vertebrate embryos. Nature 435, 215-220 10.1038/nature03488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermot J., Llamas J. G., Fraulob V., Niederreither K., Chambon P., Dollé P. (2005). Retinoic acid controls the bilateral symmetry of somite formation in the mouse embryo. Science 308, 563-566 10.1126/science.1108363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilhais-Neto G. C., Maruhashi M., Smith K. T., Vasseur-Cognet M., Peterson A. S., Workman J. L., Pourquié O. (2010). Rere controls retinoic acid signalling and somite bilateral symmetry. Nature 463, 953-957 10.1038/nature08763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokes S. A., Ji H., Wong W. H., McMahon A. P. (2008). A genome-scale analysis of the cis-regulatory circuitry underlying sonic hedgehog-mediated patterning of the mammalian limb. Genes Dev. 22, 2651-2663 10.1101/gad.1693008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Tsai C. C. (2008). Atrophin proteins: an overview of a new class of nuclear receptor corepressors. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 6, e009 10.1621/nrs.06009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Kumar R. M., Biggs V. J., Lee H., Chen Y., Kagey M. H., Young R. A., Abate-Shen C. (2011). The Msx1 homeoprotein recruits polycomb to the nuclear periphery during development. Dev. Cell 21, 575-588 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson V., Olivera-Martinez I., Storey K. G. (2009). Stem cells, signals and vertebrate body axis extension. Development 136, 1591-1604 10.1242/dev.021246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Sirbu I. O., Mic F. A., Molotkova N., Molotkov A., Kumar S., Duester G. (2009). Retinoic acid promotes limb induction through effects on body axis extension but is unnecessary for limb patterning. Curr. Biol. 19, 1050-1057 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoltewicz J. S., Stewart N. J., Leung R., Peterson A. S. (2004). Atrophin 2 recruits histone deacetylase and is required for the function of multiple signaling centers during mouse embryogenesis. Development 131, 3-14 10.1242/dev.00908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.