Abstract

talpid2 is an avian autosomal recessive mutant with a myriad of congenital malformations, including polydactyly and facial clefting. Although phenotypically similar to talpid3, talpid2 has a distinct facial phenotype and an unknown cellular, molecular and genetic basis. We set out to determine the etiology of the craniofacial phenotype of this mutant. We confirmed that primary cilia were disrupted in talpid2 mutants. Molecularly, we found disruptions in Hedgehog signaling. Post-translational processing of GLI2 and GLI3 was aberrant in the developing facial prominences. Although both GLI2 and GLI3 processing were disrupted in talpid2 mutants, only GLI3 activator levels were significantly altered in the nucleus. Through additional fine mapping and whole-genome sequencing, we determined that the talpid2 phenotype was linked to a 1.4 Mb region on GGA1q that contained the gene encoding the ciliary protein C2CD3. We cloned the avian ortholog of C2CD3 and found its expression was ubiquitous, but most robust in the developing limbs and facial prominences. Furthermore, we found that C2CD3 is localized proximal to the ciliary axoneme and is important for docking the mother centriole to the ciliary vesicle and cell membrane. Finally, we identified a 19 bp deletion in talpid2 C2CD3 that produces a premature stop codon, and thus a truncated protein, as the likely causal allele for the phenotype. Together, these data provide insight into the cellular, molecular and genetic etiology of the talpid2 phenotype. Our data suggest that, although the talpid2 and talpid3 mutations affect a common ciliogenesis pathway, they are caused by mutations in different ciliary proteins that result in differences in craniofacial phenotype.

Keywords: Primary cilia, Craniofacial, talpid2, Gli processing, Hedgehog signaling, Ciliopathies, Chicken

INTRODUCTION

The chick is a classic embryological system that has been meticulously documented and described (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951). Several institutions have bred and maintained mutant avian lines that have lent a significant amount of insight into numerous developmental processes (Robb et al., 2011). Some of the most well-studied avian genetic developmental mutants have been the talpids (talpid, talpid2 and talpid3): three independently discovered, naturally occurring, autosomal recessive, lethal mutants characterized by pre-axial polydactyly, craniofacial anomalies and a host of other developmental defects (Abbott et al., 1959; Ede and Kelly, 1964a,b; MacCabe and Abbott, 1974). Although talpid became extinct, the study of the genetic and molecular etiology of the talpid2 and talpid3 phenotypes continues.

talpid2 and talpid3 have similar limb phenotypes, yet the craniofacial phenotypes are distinct. talpid3 has severe hypotelorism, a hypoplastic frontonasal mass superior to the eyes, medially fused nasal placodes, a narrow and peg-like lower beak, and an oral cavity that is divided in two by the maxillary prominences fusing across the midline (Abbott et al., 1959, 1960; Ede and Kelly, 1964a; Hinchliffe and Ede, 1968; Buxton et al., 2004). By contrast, the talpid2 facial phenotype is characterized by a short yet wide frontonasal prominence, bilateral clefting between the frontonasal and lateral nasal prominence and hypoglossia/aglossia (Schneider et al., 1999; Brugmann et al., 2010). Molecularly, the talpid3 mutant has been more extensively studied and attributed to disruptions in Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling (Buxton et al., 2004; Davey et al., 2006, 2007). Whereas the defect in SHH signaling was clear, understanding the molecular mechanism for the phenotype was confounded by the fact that the facial phenotype was indicative of a loss of SHH function, but the limb phenotype was indicative of a gain of SHH function (Buxton et al., 2004; Davey et al., 2006, 2007). A deeper understanding of the molecular etiology of the mutant was gained when the causal genetic element for talpid3 was identified and characterized as a protein (now called TALPID3 after the mutant itself) that localizes to the basal body of the primary cilia (Yin et al., 2009).

Primary cilia are ubiquitous organelles that serve as a cellular hub for the transduction of numerous signaling pathways. Most notably, cilia have been identified as the location for post-translational processing of GLI proteins (Goetz and Anderson, 2010). GLI proteins are transcription factors that regulate a number of cellular processes (e.g. proliferation, specification and differentiation). Full-length GLI (GLIFL) can be processed via phosphorylation into the activator isoform (GLIA) or cleaved into the repressor isoform (GLIR) (Liu et al., 2005). Inhibition of GLI processing prevents production of GLIA and GLIR isoforms (Haycraft et al., 2005). Thus, an essential role of primary cilia is to establish the ratio of GLIA to GLIR proteins, which in turn controls transcription of SHH target genes.

Our earlier studies regarding the molecular mechanism of talpid2 suggested defects in primary cilia (Brugmann et al., 2010); however, these studies did not address the extent of ciliary dysfunction, molecular consequences of aberrant cilia or the genetic cause of the mutation. Studies from other groups have suggested that the polydactylous phenotype of talpid2 was attributable to constitutive activation of SHH signaling, in which activation of the SHH pathway occurs in the absence of a SHH ligand (Caruccio et al., 1999). The limb phenotype in the talpid2 mutant has been attributed to defects in GLI processing (Caruccio et al., 1999), but an in-depth analysis of GLI protein expression in the facial prominences has not been explored.

No direct comparison or complementation analysis of talpid2 and talpid3 mutants has been undertaken. The similar phenotypes of the mutants raised the possibilities that the causative genetic elements for these mutants were: (1) alleles of the same gene with different grades of expression (Ede and Kelly, 1964b); (2) separate genetic insults within the same pathway; or (3) completely separate defects. Herein, we explore the cellular and molecular basis for the talpid2 craniofacial mutation, comparing our findings with those in the talpid2 limb and in talpid3. Furthermore, we use whole-genome sequencing of inbred talpid2 lines to identify the causative locus for the talpid2 mutation and confirm that it is distinct from the talpid3 mutation.

RESULTS

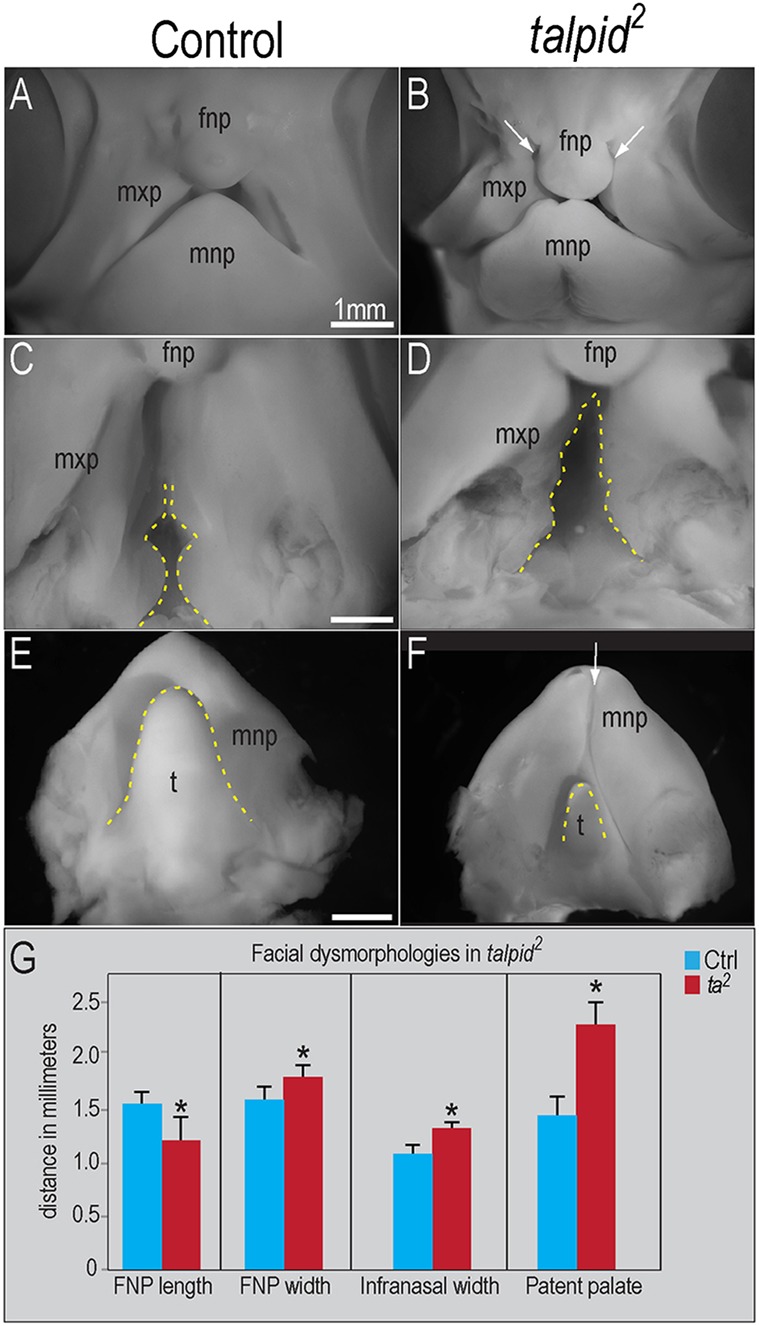

talpid2 embryos have craniofacial defects

Although craniofacial defects have been previously reported in talpid2 embryos (Abbott et al., 1959; Yee and Abbott, 1978; Caruccio et al., 1999; Schneider et al., 1999; Brugmann et al., 2010), an in-depth analysis of the development of facial prominences has not been reported. We examined control and talpid2 embryos and analyzed the growth of the frontonasal, maxillary and mandibular prominences (Fig. 1). talpid2 embryos displayed bilateral clefting between the frontonasal, lateral nasal and maxillary prominences (Fig. 1A,B). The frontonasal prominence was significantly shorter and wider in talpid2 embryos relative to controls (Fig. 1A,B,G). Growth of the maxillary prominence was also disrupted. The maxillary prominences fuse to form the secondary palate. In avians, part of the secondary palate remains patent (Lillie, 1908) (Fig. 1C). In contrast to control embryos, the extent of patency was significantly increased in talpid2 embryos (Fig. 1C,D,G). We also measured inner intercanthal distance and the width of the lateral nasal prominence. Neither of those measurements showed significant variation between control and talpid2 embryos (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that the predominant cause of clefting in the talpid2 embryos is the aberrant growth of the frontonasal and maxillary prominences. Finally, we analyzed the growth of the mandibular prominence. The mandibular prominences of talpid2 embryos fail to fuse completely (Fig. 1E,F). In addition, a large percentage of talpid2 embryos (10/12; 83%) exhibit hypoglossia/aglossia (Fig. 1E,F). These data confirm that the growth and development of the facial prominences are significantly disrupted in talpid2 embryos.

Fig. 1.

Growth and development of the facial prominences is disrupted in talpid2 mutants. Day 7 control (n=10) and talpid2 (n=4) embryos. (A,B) Frontal views of facial prominences; frontonasal (fnp), maxillary (mxp) and mandibular prominences (mnp). Bilateral clefting in talpid2 embryos (white arrows in B). (C,D) Palatal views show increased patency of both the primary and secondary palate of talpid2 embryos (dotted yellow line). (E,F) Dorsal view of the mnp. The mnp of talpid2 embryos is clefted (white arrow in F) and exhibits hypoglossia (dotted yellow line). (G) Quantitative analysis of fnp and mxp growth. For fnp length, *P<0.02; for fnp width, *P<0.02; for infranasal width, *P<0.04; for patent palate, *P<0.02. t, tongue. Data are mean±s.e.m. Scale bars: 1 mm (A-F).

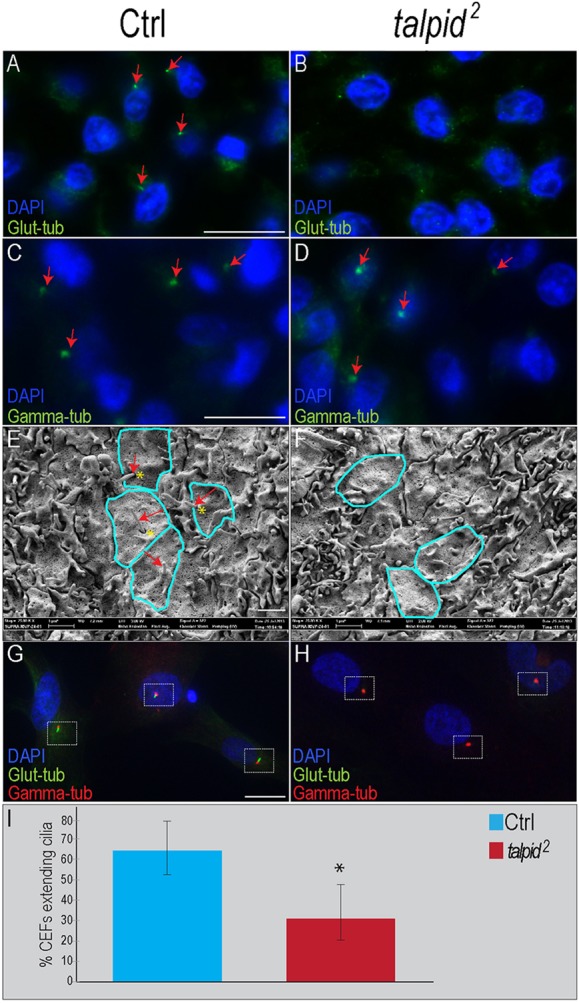

Primary cilia are disrupted throughout the talpid2 embryo

The talpid3 phenotype had previously been shown to be a product of disrupted primary cilia (Yin et al., 2009). Our previous work identified disrupted cilia in talpid2 mutants (Brugmann et al., 2010). We confirmed this finding by performing immunostaining with glutamylated-tubulin on facial mesenchyme (Fig. 2A,B). Glutamylated-tubulin staining in control avian embryos is localized to the ciliary axoneme (Fig. 2A), whereas staining in the talpid2 mesenchyme is diffuse and unorganized (Fig. 2B). We also examined γ-tubulin staining in the centrosome (Fig. 2C,D). We found abundant, punctate γ-tubulin staining in the mesenchyme of control embryos (Fig. 2C). Although we were able to detect γ-tubulin in talpid2 embryos (Fig. 2D), some staining was diffuse and not as punctate as in control embryos (Fig. 2D). To further characterize ciliary extension in the talpid2 mutants, we performed scanning electron microscopy in the forebrain (Fig. 2E,F). We found numerous ciliary extensions within a ciliary pocket (Fig. 2E) in control embryos. In talpid2 embryos, however, the majority of cells did not extend a cilium (Fig. 2F). Finally, we isolated and cultured chicken embryonic fibroblasts (CEFs) from both control and talpid2 embryos and quantified the percentage of cells extending a cilium. Sixty-four percent of control CEFs extended a glutamylated-tubulin-positive extension adjacent to a punctate domain of γ-tubulin staining (Fig. 2G,I). By contrast, only 32% talpid2 CEFs extended a glutamylated-tubulin-positive extension adjacent to a punctate domain of γ-tubulin staining (Fig. 2H,I). These results, in conjunction with our previous findings, strongly suggest that the talpid2 phenotype, like the talpid3 phenotype, is caused by a ciliary defect.

Fig. 2.

Primary cilia are disrupted in talpid2 mutants. (A-D) Immunostaining for ciliary markers on facial sections. (A,B) Anti-glutamylated-tubulin in facial mesenchyme. Red arrows mark axoneme. (C,D) Anti-γ-tubulin in facial mesenchyme. Red arrows mark centriole. (E,F) Scanning electron microscopy of the ventricular surface of the neuroectoderm. Blue lines outline cells; red arrow indicates axoneme; yellow asterisks mark ciliary pockets. (G,H) Double glutamylated- and γ-tubulin immunostaining in CEFs. (I) Quantification of control (n=686) and talpid2 (n=522) CEFs extending primary cilia; *P<0.005. Data are mean±s.e.m. Scale bars: 10 µm in A-D; 1 µm in E,F; 20 µm in G,H.

SHH expression and activity are affected in the developing face and brain of talpid2 embryos

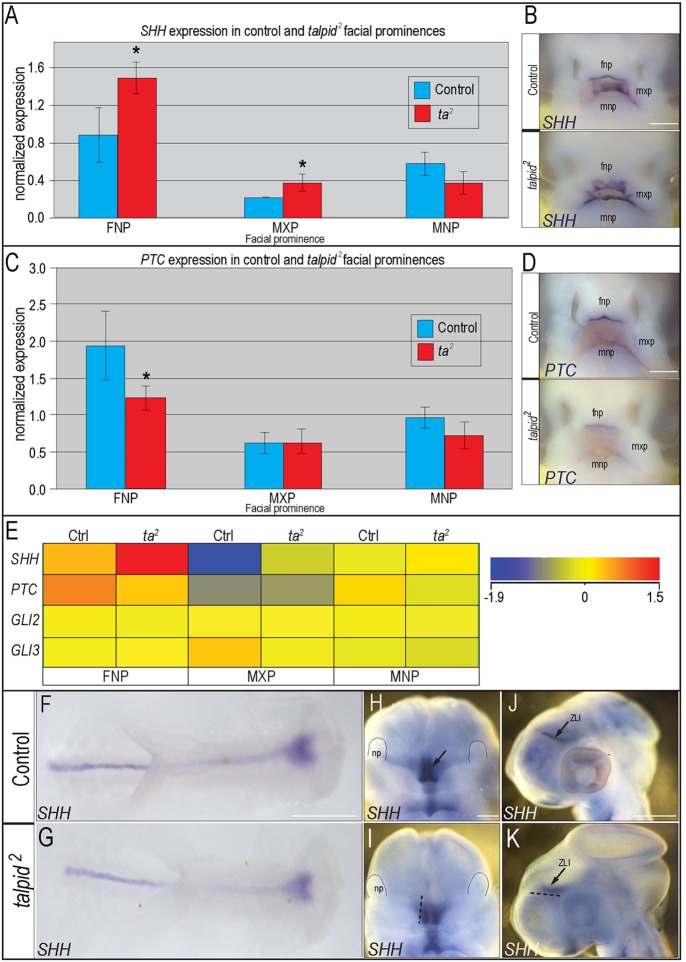

Previous studies have reported aberrant SHH expression in talpid2 embryos (Caruccio et al., 1999; Schneider et al., 1999; Agarwala et al., 2005). As ciliary defects have been known to affect various tissues and developmental domains differently, and because previous reports suggest a gain of SHH function in the limb with a loss of SHH function in the face of talpid3 (Buxton et al., 2004; Davey et al., 2006, 2007), we examined SHH expression and pathway activity in both the developing facial prominences and the developing brain. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) of individual facial prominences demonstrated that levels of SHH ligand expression varied in a prominence-specific manner. SHH expression was increased in both frontonasal and maxillary prominences; however, there was a slight decrease in expression in the mandibular prominence (Fig. 3A). These results were confirmed with in situ hybridization for SHH in HH25 control and talpid2 embryos (Fig. 3B). An increase in SHH ligand typically results in increased activity of the pathway, as marked by increased PATCHED (PTC) transcription. Despite increased SHH ligand expression, PTC expression was significantly reduced in the frontonasal prominence (Fig. 3C). Conversely, PTC expression was not significantly altered in either the maxillary or mandibular prominences (Fig. 3C). Variation in PTC expression was confirmed with in situ hybridization (Fig. 3D). Finally, RNA-seq was performed on individual facial prominences of both control and talpid2 embryos (Fig. 3E). These data support both qRT-PCR and in situ data suggesting that, although SHH ligand expression is increased in the frontonasal and maxillary prominences, pathway activity (as determined by PTC expression) is not. These data suggest SHH expression is altered in a prominence-specific manner and that ligand expression does not necessarily correlate with canonical SHH pathway activity in talpid2 embryos.

Fig. 3.

SHH signaling is disrupted in the developing face and brain of talpid2 mutants. (A) qRT-PCR for SHH in frontonasal (FNP), maxillary (MXP) and mandibular (MNP) prominences in control and talpid2 embryos; *P<0.05. Data are mean±s.e.m. (B) In situ hybridization for SHH in control (n=7) and talpid2 (n=3) HH25 embryos. (C) qRT-PCR for PTC; *P<0.03. Data are mean±s.e.m. (D) In situ hybridization for PTC in control (n=7) and talpid2 (n=3) HH25 embryos. (E) RNA-seq results for SHH, PTC, GLI2 and GLI3 expression. (F-K) In situ hybridization for SHH in control and talpid2 embryos. (F,G) Dorsal view of control (n=11) and talpid2 (n=9) HH10 embryos. (H-K) Frontal and lateral views of control (n=8) and talpid2 (n=4) HH20 embryos. Dotted black lines in I,K represent the size of the expression domain in the control embryo (H,J). ZLI, zona limitans intrathalamica. Scale bars: 250 µm in B,D; 600 µm in F,G; 100 µm in H,I; 200 µm in J,K.

The developing brain strongly influences the developing face (Marcucio et al., 2005; Young et al., 2010; Chong et al., 2012). There are several SHH signaling centers in the brain that can influence growth of the craniofacial complex, including the SHH domain in the ventral neural tube, forebrain and the zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI). To determine whether centers of SHH activity were disrupted in the brain of talpid2 embryos, we examined the expression of SHH at various stages of development. At HH10, the SHH domain in the ventral floor plate was evident in both control and talpid2 embryos (Fig. 3F,G). At HH20, however, SHH expression in both the forebrain and ZLI was significantly reduced (Fig. 3H-K). Thus, although initially established correctly, later SHH signaling domains are reduced in the developing brain of talpid2 embryos.

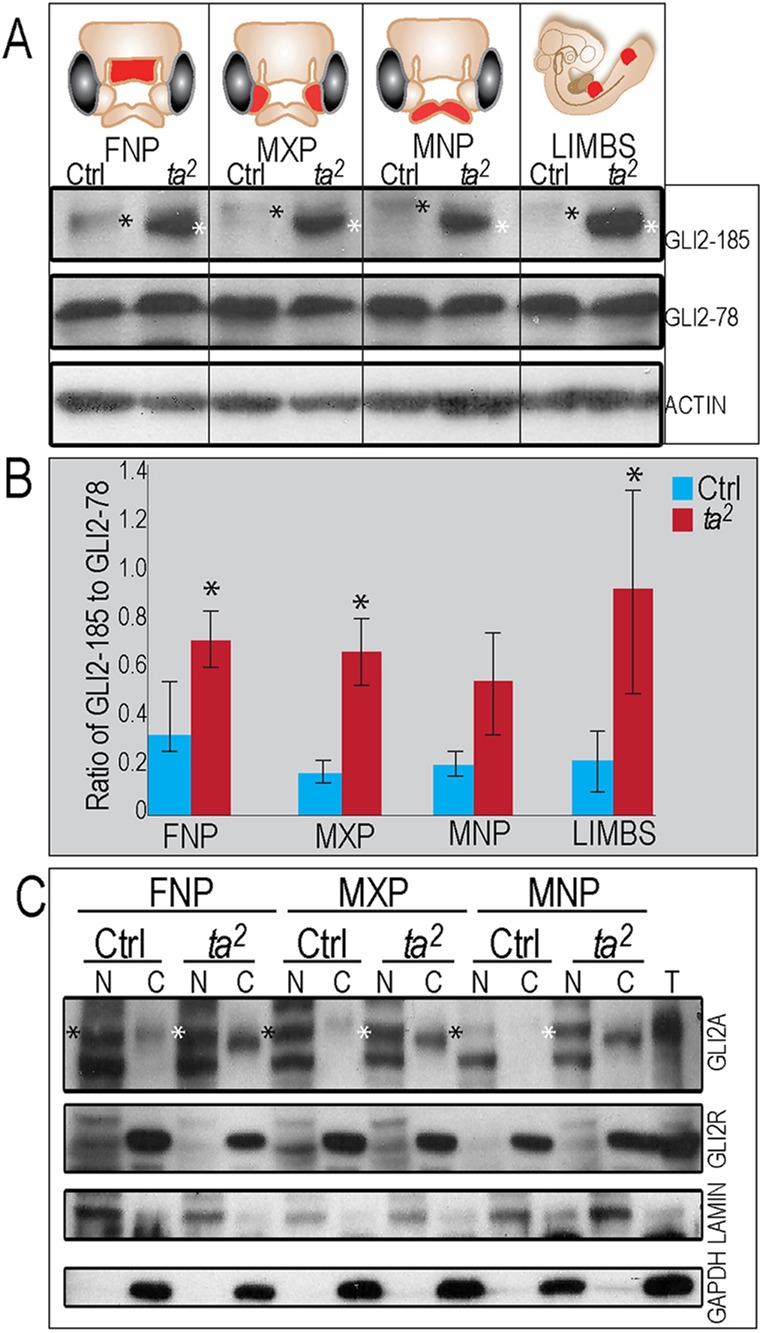

Post-translational processing of GLI2 is disrupted in the talpid2 mutant

Functional primary cilia are required for the proper processing of full-length GLI proteins (GLIFL) into either a full-length activator or a cleaved repressor (Haycraft et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2005; May et al., 2005; Humke et al., 2010; Wen et al., 2010). To determine whether the talpid2 craniofacial phenotype could be attributed to aberrant post-translational processing of the GLI transcription factors, we performed western blot analyses on individual facial prominences. We began our analysis with GLI2 because it functions as the primary activator of the SHH pathway (Ding et al., 1998; Motoyama et al., 1998; Park et al., 2000; Bai et al., 2002), and the limb phenotype in talpid2 embryos is highly suggestive of a gain of SHH phenotype. Using an antibody that recognizes both full-length (GLI2-185) and cleaved isoforms (GLI2-78) of GLI2, we found significant disruptions in both the developing facial prominences and limbs (Fig. 4). Relative to control, there was a significant and consistent increase in the levels of GLI2-185 in all talpid2 facial prominences and limb buds (Fig. 4A). Although GLI2 predominantly functions as a full-length isoform (Pan et al., 2006), we were able to detect an equivalent amount of the cleaved isoform in both control and talpid2 tissue (Fig. 4A). The ratio of full-length versus cleaved activity is used as a measure of net SHH pathway activity (Huangfu and Anderson, 2005). The increase in level of GLI2-185 in talpid2 mutants resulted in an increased ratio of GLI2-185 to GLI2-78, as quantified by densitometry (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Post-translational processing of GLI2 is disrupted in talpid2 mutants. (A) Western blot analysis for GLI2 in HH 25 facial prominences and limbs. Both full-length GLI2 protein (GLI2-185) and cleaved GLI2 (GLI2-78) are present. Gel mobility of GLI2-185 is higher in talpid2 (compare black and white asterisks). (B) Ratio of GLI2-185 to GLI2-78 is increased in talpid2. *P<0.05. Data are mean±s.e.m. (C) Nuclear fractionation detects both GLI2 activator (GLI2A) and GLI2 repressor (GLI2R). LAMIN and GAPDH expression mark the nuclear (N) and cytosolic (C) compartment. T, total protein.

To test whether the increased levels of GLI2-185 detected via whole-lysate western blot correlate with increased levels in the nuclear GLI2A in talpid2 mutants, we performed nuclear fractionation analysis (Fig. 4C). Although we detected increased GLI2-185 in all prominences of the talpid2 mutant (Fig. 4A,B), our nuclear fractionation result indicated that the levels of nuclear GLI2A were equivalent within control and talpid2 mutants (Fig. 4C; supplementary material Table S1). Furthermore, we did not note any significant change in the amount of cleaved nuclear GLI2R in talpid2 mutants (Fig. 4C; supplementary material Table S1). Taken together, our experiments indicate that, although full-length GLI2 processing is impaired in talpid2 mutants, nuclear levels of GLI2A and GLI2R are not altered.

To function properly, GLI proteins require post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation (Pan et al., 2009; Canettieri et al., 2010; Cox et al., 2010; Hui and Angers, 2011). In light of our results showing an accumulation of talpid2 full-length GLI2 with higher mobility than control full-length GLI2 (Fig. 4A) and multiple bands being detected in our nuclear fractionation (Fig. 4C), we tested the hypothesis that improper phosphorylation accounted for the changes in the mobility of GLI2-185 between control and talpid2. Phosphatase treatment did not alter mobility of control GLI2-185 to that of talpid2 GLI2-185 (supplementary material Fig. S1A), suggesting that aberrant phosphorylation is not the cause of increased mobility of talpid2 full-length GLI2. Regardless of increased mobility of talpid2 GLI2-185, the mobility and overall amount of talpid2 GLI2A protein in the nucleus was unchanged relative to control embryos and thus was determined not to be a possible cause for the talpid2 phenotype.

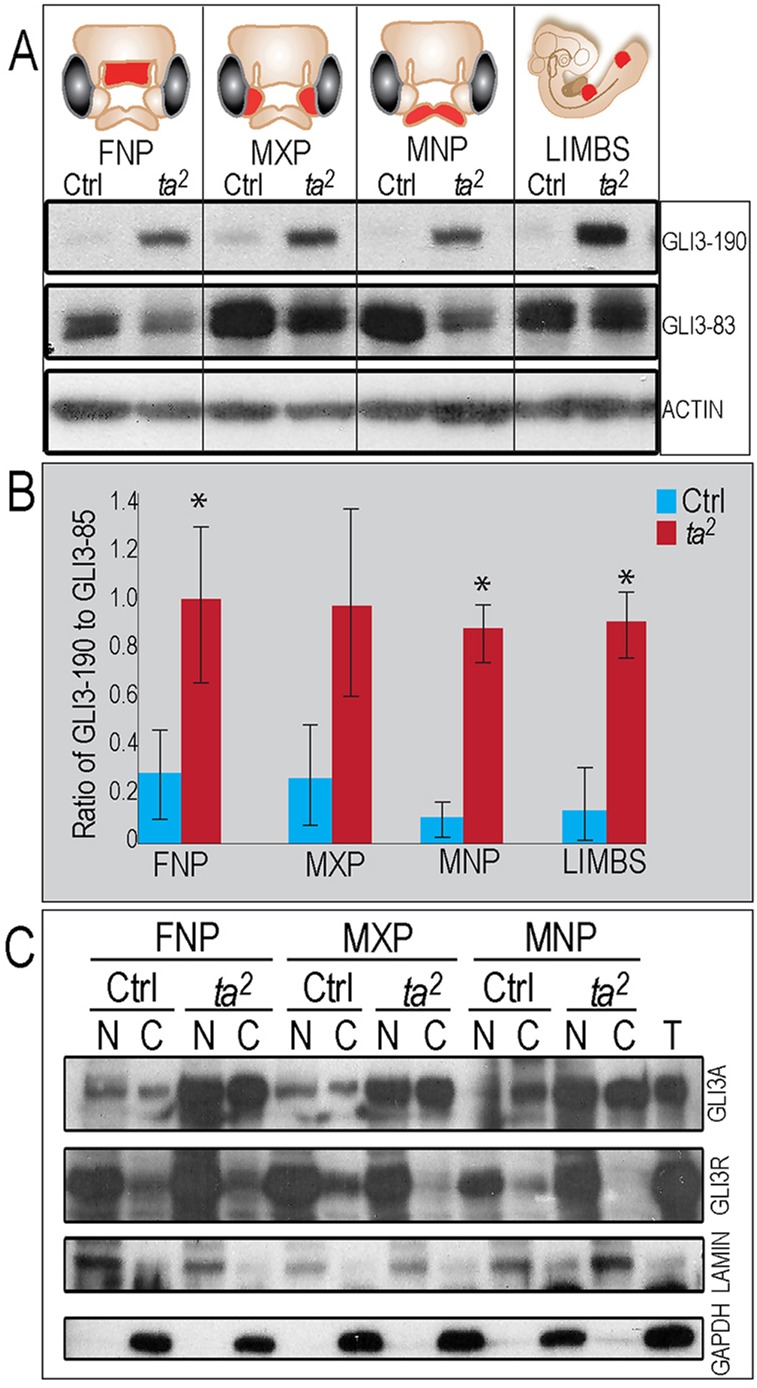

Post-translational processing of GLI3 is disrupted and GLI3 activator is increased in talpid2 mutants

We next examined the levels of GLI3 between control and talpid2 facial prominences (Fig. 5A). Similar to what we observed with GLI2, we found an increase in the levels of full-length GLI3 (GLI3-190) in talpid2 facial prominences and limb buds (Fig. 5A). Contrary to what we observed with the cleaved isoform of GLI2, levels of the cleaved GLI3 isoform (GLI3-83) were reduced in the talpid2 facial prominences relative to controls (Fig. 5A). Quantification of gel images by densitometry indicated that the ratio of GLI3-190 to GLI3-83 was also increased in talpid2 (Fig. 5B). Thus, our data suggest that in talpid2, GLI3 processing is also disrupted, resulting in an accumulation of GLI3-190 at the expense of GLI3-83.

Fig. 5.

Post-translational processing of GLI3FL is disrupted in talpid2. (A) Western blot analysis for GLI3 in HH 25 facial prominences and limbs. Both full-length GLI3 protein (GLI3-190) and cleaved GLI3 (GLI3-83) are present. (B) Ratio of GLI3-190 to GLI3-83 is increased in talpid2. *P<0.05. (C) Nuclear fractionation detects both GLI3 activator (GLI3A) and GLI3 repressor (GLI3R). LAMIN and GAPDH expression mark the nuclear (N) and cytosolic (C) compartment. T, total protein.

Similar to GLI2, full-length GLI3 can be degraded in the cytoplasm or enter the nucleus as a full-length activator (GLI3A) or cleaved repressor (GLI3R). Contrary to GLI2, GLI3 acts as the predominant repressor of the SHH pathway (Vortkamp et al., 1992; Hui and Joyner, 1993; Biesecker, 1997; Persson et al., 2002). Nuclear fractionation revealed that increased levels of whole lysate GLI3-190 correlated with a robust increase of nuclear GLI3A in talpid2 mutants (Fig. 5C; supplementary material Table S1). Furthermore, although GLI3-83 levels appeared slightly decreased via whole lysate examination, nuclear fractionation suggests that the total levels of GLI3R in the nucleus are equivalent between the control and talpid2 embryos (Fig. 5C). Detection of increased nuclear GLI3A supports a hypothesis that increase of GLI3 activator activity is the cause of the talpid2 facial phenotypes.

To determine the cause of aberrant GLI-190 production, we assessed the phosphorylation status of GLI3-190 in control and talpid2 embryos using phosphatase treatment (supplementary material Fig. S1B). We did not observe differential gel mobility between control and talpid2 GLI3-190. Although the amount of GLI3-190 was increased in talpid2, we observed similar shifts in mobility. These results indicate that aberrant phosphorylation is not the cause of increased full-length, nuclear GLI3A in talpid2 mutants.

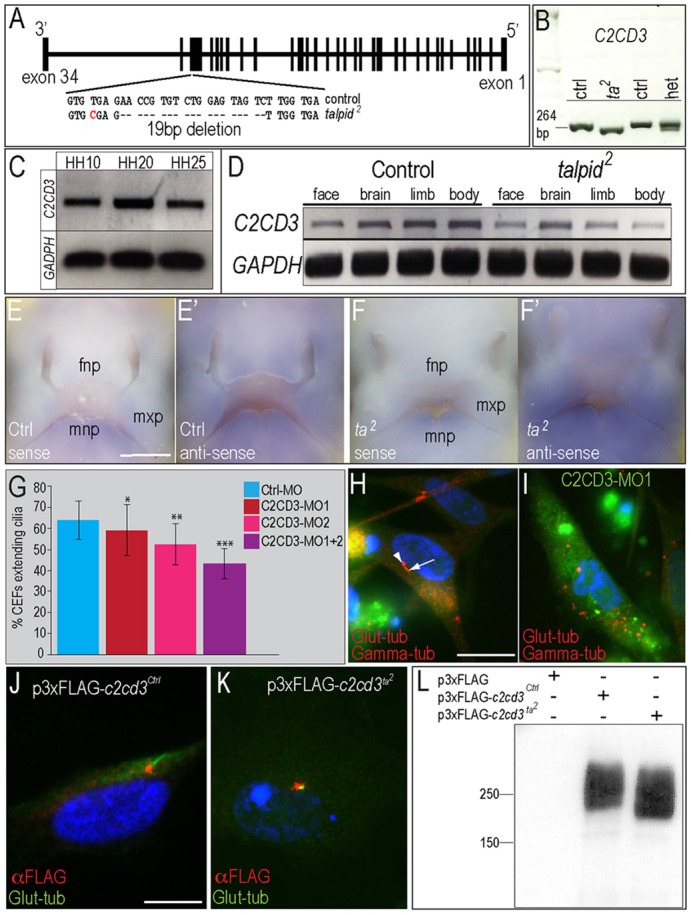

Genetic mapping and identification of the talpid2 locus

The talpid3 phenotype was linked to a ciliary gene encoded on chromosome 5 (GGA5) (Yin et al., 2009). Using a 60K SNP array, we previously identified five candidate chromosome locations (two on GGA1q, two on GGA10q and one on GGA15), none of which mapped to the talpid3 locus (Robb et al., 2011). Variation between the mutant talpid2.003 line and the congenic UCD003 control line was examined by whole-genome sequencing, and candidate genes and alleles were examined at all five intervals (data not shown; supplementary material Tables S2 and S3). These data indicated that the telomeric region of GGA1q (193.7 Mb to 195.2 Mb) exhibited at least a threefold higher ratio of talpid2-specific SNPs over any other interval (supplementary material Table S4), suggesting that this interval contained fixed, talpid2-specific polymorphisms derived from the original mutant line. Analysis of this interval suggested three potential candidate genes with variations that had potential to impair gene function: C2CD3 (C2 calcium-dependent domain containing 3), NUP98 (nucleoporin, 98 kDa) and NEU3 (neuraminidase 3). We subsequently resequenced all three candidates from both control and mutant samples, and did not find any likely causal polymorphisms, significant changes in transcript size or changes in level of expression in NUP98 and NEU3 (data not shown). As demonstrated by our cDNA cloning and sequencing, the chicken ortholog of C2CD3 produces a 7496 bp transcript with 34 exons (Fig. 6A; supplementary material Fig. S2). Whole-genome sequencing, cDNA sequencing and resequencing of the talpid2.003 line confirmed one insertion, one deletion and nine missense differences within the C2CD3 open reading frame between control and talpid2 genomes (supplementary material Table S5). The majority of the missense variants were likely to be tolerated and were located in regions of low complexity (according to protein modeling) with weak evolutionary conservation (data not shown); they were thus not likely to be causative. Moreover, subsequent resequencing of talpid2 alleles in a commercial background line (rather than being congenic on UCD003, as talpid2.003 is) eliminated most of the missense mutations as potential causal alleles. The top candidate for the causal mutation was a 19 bp deletion in the 3′ end of exon 32 (Fig. 6A) that produces a premature stop codon leading to the deletion of amino acids 2210-2330. PCR analysis supported our sequencing results and detected the 19 bp deletion in talpid2 mutants (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

C2CD3 is the candidate gene for the talpid2 mutation. (A) Chicken C2CD3. A 19 bp deletion was identified within exon 32 of talpid2. (B) RT-PCR analysis of C2CD3 in control, talpid2 and heterozygous embryos. (C) RT-PCR for C2CD3 in whole embryos. (D) RT-PCR for C2CD3 in various domains of HH25 embryos (n=3). (E-F′) In situ hybridization for C2CD3. (G) Quantification of CEFs extending cilia after transfection with a control-MO (n=342), C2CD3-MO1 (n=559), C2CD3-MO2 (n=551) or C2CD3-MO1+C2CD3-MO2 (n=573); *P<0.05, **P=0.001, ***P<0.0001. Data are mean±s.e.m. (H) Immunofluorescence marking glutamylated-tubulin (arrow) and γ-tubulin (arrowhead) on non-transfected CEFs. (I) Glutamylated-tubulin expression is lost on CEFs transfected with C2CD3-MO1. (J,K) Double immunofluorescence marking glutamylated-tubulin (green) and FLAG (red) on CEFs transfected with p3xFLAG-C2CD3Ctrl (J) or p3xFLAG-C2CD3ta2 (K). (L) Western blot analysis of CEFs transfected with p3xFLAG-C2CD3Ctrl and p3xFLAG-C2CD3ta2. Scale bars: 500 µm in E-F′; 20 µm in H,I; 10 µm in J,K.

We next examined the temporal and spatial expression of chicken C2CD3 in control and talpid2 embryos. Temporally, we found C2CD3 was robustly expressed throughout craniofacial development (Fig. 6C). To examine spatial expression, we isolated developing face, brain, limb and body from HH25 embryos (Fig. 6D). C2CD3 was ubiquitously expressed throughout all dissected domains of control and talpid2 embryos. Furthermore, we visualized C2CD3 expression via in situ hybridization. Whereas we did not detect any expression with the sense probe (Fig. 6E,F), low levels of ubiquitous expression and higher levels of localized expression in the branchial arches and limbs were detected in both control and talpid2 embryos (Fig. 6E′,F′; supplementary material Fig. S3). This expression pattern is consistent with C2CD3 expression in murine embryos (Hoover et al., 2008) and consistent with the talpid2 craniofacial and limb phenotype.

Next, to confirm that C2CD3 plays a role in ciliogenesis, we generated control and two distinct C2CD3-specific morpholinos. Control CEFs were transfected with a control morpholino, or with one or both C2CD3 morpholinos (Fig. 6G). Similar to non-transfected control CEFs (Fig. 2I), ∼63% of CEFs transfected with control MO extended a primary cilium (Fig. 6G). After transfection with C2CD3-MO1, C2CD3-MO2 or C2CD3-MO1 plus C2CD3-MO2, the number of CEFs extending cilia was significantly reduced (Fig. 6G). For example, the ciliary basal body and axoneme were clearly present in cells not transfected with C2CD3-MO; however, in the presence of C2CD3-MO, axoneme extension was absent (Fig. 6H,I). Taken together, these experiments suggest that C2CD3 contains the causal allele for the talpid2 mutant, that C2CD3 is expressed in areas correlating with the talpid2 phenotype and that MO-induced reduction of C2CD3 protein negatively affects ciliary extension.

C2CD3 is hypothesized to localize to either the proximal axoneme (transition zone) (Zhang and Aravind, 2012) or to the distal centriolar region (transition fibers) (Balestra et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2014). To determine where C2CD3 localized within avian cells, we transfected CEFs with FLAG-tagged control C2CD3 (C2CD3Ctrl). We detected FLAG-C2CD3Ctrl adjacent to, but not overlapping with, the ciliary axoneme (Fig. 6J). These results support previous findings in humans and mice suggesting that C2CD3 localizes to the distal aspect of the centrioles within the transition fibers (Balestra et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2014). We next tested whether the 19 bp deletion in talpid2 C2CD3 affected the cellular localization of this protein. FLAG-C2CD3ta2 was detected proximal to the axoneme, suggesting that the mutation does not affect the cellular localization of C2CD3 (Fig. 6K).

To determine whether the 19 bp deletion in talpid2 C2CD3 affected C2CD3 protein stability and size, we transfected both FLAG-C2CD3Ctrl and FLAG-C2CD3ta2 into CEFs and performed western blot analysis. As expected, cells transfected with the FLAG-C2CD3ta2 produced a significantly smaller protein relative to FLAG-C2CD3Ctrl (Fig. 6L), confirming that the 19 bp deletion generated a premature stop codon, producing a truncated version of C2CD3 in talpid2 embryos. Furthermore, our western blot analysis confirms that the talpid2 mutation does not affect C2CD3 stability or expression levels, as equal amounts of anti-FLAG staining were observed. Thus, although truncated, C2CD3 is still produced and properly localized in talpid2 embryos.

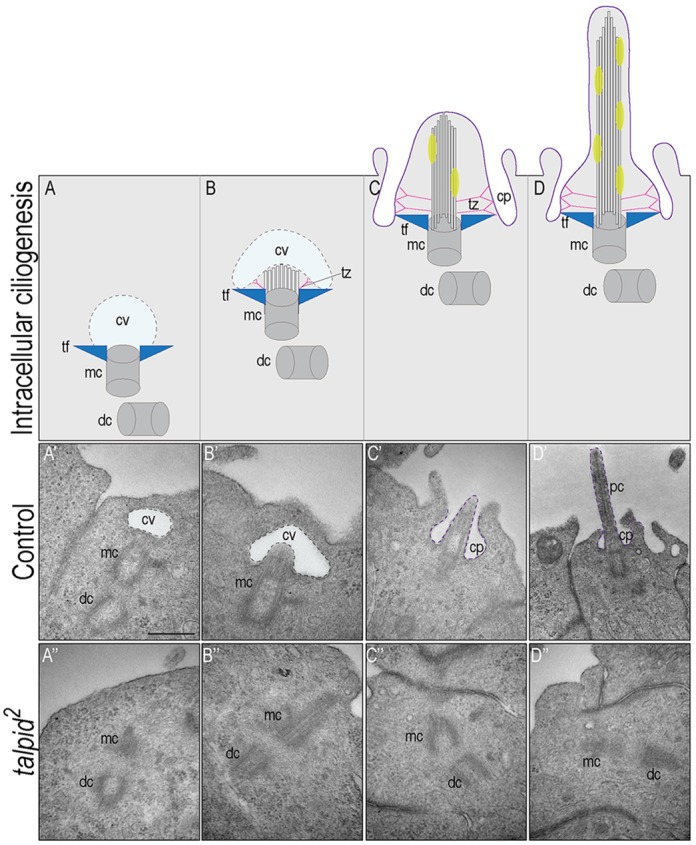

Ciliary vesicle docking and intracellular ciliogenesis is disrupted in talpid2 embryos

A recent study examining the role of C2CD3 in murine cells reported that the protein was localized within the transition fibers, it was required for initiating ciliogenesis via the recruitment of other centriolar distal appendage and intraflagellar transport proteins, and it was required for ciliary vesicle docking to the mother centriole (Ye et al., 2014). To determine whether the mechanism of avian C2CD3 function was similar to that of murine C2CD3, we analyzed control and talpid2 embryos via transition electron microscopy (TEM). Specifically, we used TEM to examine intracellular ciliogenesis: the process of ciliogenesis that uses transition fibers to associate with a ciliary vesicle and creates a ciliary pocket to establish an extended primary cilium (Fig. 7A-D) (Molla-Herman et al., 2010; Reiter et al., 2012). Association of the mother centriole with a ciliary vesicle was clearly detected in ∼45% of control cells (Fig. 7A′). Furthermore, invagination of the ciliary vesicle associated with microtubule outgrowth from the mother centriole (Fig. 7B′), association of the mother centriole with the plasma membrane (Fig. 7C′) and formation of an extended cilium within a ciliary pocket (Fig. 7D′) were also frequently observed in control cells. By contrast, proper orientation and association with the ciliary vesicle was only observed in 20% of talpid2 cells (Fig. 7A″-D″). Thus, we conclude that truncated C2CD3 in talpid2 embryos impairs the ability of this protein to properly establish the transition fiber complex, which in turn affects intracellular ciliogenesis through failure of mother centriole/ciliary vesicle docking.

Fig. 7.

Intracellular ciliogenesis is disrupted in talpid2 embryos. Hypothesized steps of intracellullar ciliogenesis. (A) A ciliary vesicle (cv) binds to the distal end of the mother centriole (mc), via associations with transition fibers (tf). (B) Microtubule and transition zone (tz) outgrowth emerges and invaginates the cv. (C) Docking of the centriolar/cv complex to the plasma membrane. (D) Axonemal outgrowth. (A′-D′) Steps of intracellular ciliogenesis in control embryos (n=11). (A″-D″) Intracellular ciliogenesis is significantly disrupted in talpid2 embryos. Association of the mc with the cv and progression of the centriolar/cv complex docking with the plasma membrane rarely occur in talpid2 embryos (n=15). dc, daughter centriole; pc, primary cilium; cp, ciliary pocket. Scale bars: 500 nm in A′-D″.

DISCUSSION

The talpid2 is an intriguing avian mutant that has been studied by the developmental community for many years (Abbott et al., 1959; Abbott, 1967; MacCabe and Abbott, 1974). Although disruptions in SHH signaling had been implicated in this mutant, there was a lack of understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanism for this phenotype. Furthermore, the genetic basis for this mutation was entirely unknown. We have previously suggested that defects in primary cilia exist within this mutant (Brugmann et al., 2010). Here, we confirm the aberrant structure and function of primary cilia in talpid2 mutants and determine that SHH signaling is disrupted. Specifically, an increased amount of GLI3A in both the developing facial prominences and limb buds was observed in mutant embryos. We further identified C2CD3 as the presumptive locus containing the talpid2 mutation via whole-genome sequencing and resequencing of multiple talpid2 mutants. Resequencing identified a 19 bp deletion in C2CD3 that causes a premature stop codon and produces a truncated protein in talpid2 embryos. We hypothesize that this is the casual mutation for the talpid2 phenotype. In addition to the 19 bp deletion, however, there is a missense mutation leading to an alanine-to-proline change at codon 782 consistently found among all talpid2 alleles (supplementary material Table S5). Although this amino acid is not widely conserved in other vertebrate C2CD3 genes, no other species contains proline at this codon. Therefore, we cannot eliminate the possibility that the Ala782Pro mutation, rather than the 19 bp deletion, leads to the mutant phenotype or, perhaps, a combination of both mutations. Reconciling the consequence(s) of this amino acid change is the focus of ongoing work.

The SHH pathway is uncoupled in a prominence-specific manner in talpid2 mutants

Our initial work identified increased expression of SHH pathway members in talpid2 mutants (Brugmann et al., 2010). Herein, we performed more in-depth analyses using qRT-PCR, RNA-seq and in situ hybridization to individually analyze each facial prominence. Often, a direct relationship between ligand and pathway activity occurs; SHH ligand expression is coupled to an increase in pathway activity, as marked by an increase in PTC or GLI1 transcription. Our analysis, however, suggests that this ‘coupling’ of the pathway is disturbed in talpid2 mutants in a facial prominence-specific manner. For example, there is an increase of SHH ligand expression in the frontonasal prominence, but PTC expression is reduced. By contrast, the maxillary prominence has increased SHH ligand expression with no change in PTC expression (Fig. 3). From these data, we conclude that aberrant ciliogenesis uncouples the SHH pathway in talpid2 mutants; however, the manner in which the pathway is perturbed is dependent upon the distinct molecular environment present in the individual facial prominences.

Disruptions in GLI processing are conserved between ciliary mutants

Members of the GLI family of transcription factors have been well studied for their role in developmental processes (Hui and Angers, 2011). Defects in GLI activity have been associated with craniofacial anomalies in both humans (Greig cephalopolysyndactyly) (Vortkamp et al., 1991, 1992) and mice (Extra-toes) (Johnson, 1967). Our analysis of GLI processing during craniofacial development revealed a number of interesting findings. First, our data suggest that the talpid2 mutation affects GLI2 differently from GLI3. GLI2 has a higher mobility in talpid2 mutants, indicating a lack or reduction of post-translational modifications required for proper function of the protein (Fig. 4A; supplementary material Fig. S1A). GLI3, however, does not show any mobility shift or differential response to phosphatase treatment (Fig. 5A; supplementary material Fig. S1B). Thus, there could be a different cadre of proteins required for the processing of GLI2 than GLI3. Second, although examined in different tissues, the most-significant molecular defect in both talpid2 and talpid3 appears to be the increase in the levels of GLI3A (Fig. 5C) (Davey et al., 2006). An increase in GLI3A suggests a net-increase in pathway activity; however, data from studies of the talpid3 suggest that there is a gain of SHH phenotype in the limb, yet a loss of SHH phenotype in the face (Buxton et al., 2004; Davey et al., 2006, 2007). By performing tissue isolations prior to western blotting, we confirmed that GLI processing was consistent among all facial prominences and the limb in talpid2. Thus, using GLI protein as an indicator of pathway activity, it can be concluded that there is a gain of SHH function in both the face and limb of talpid2. We hypothesize that this disruption is due to reduced ciliary function in talpid2 embryos, rather than to a direct interaction with C2CD3 protein, as neither FLAG-C2CD3Ctrl nor FLAG-C2CD3ta2 was able to pull-down GLI3 (supplementary material Fig. S4). It will be of great interest to determine whether TALPID3 and C2CD3 function in parallel, or as part of a greater complex necessary for GLI processing, centriolar docking or transition fiber formation.

talpid2 and talpid3 are caused by distinct mutations within proteins that function in the same cellular compartment and signaling pathway

The talpid mutants have long been associated with one another based simply on presentation of some similar phenotypes. Limited distribution and resources have prevented a direct comparison of the two mutations. The talpid3 mutant has been bred and maintained in the UK, whereas the talpid2 mutant has remained in the USA. The talpid3 mutation has been mapped to chromosome 5 and shown to be caused by a mutation in the KIAA0568 gene, which encodes what is now called TALPID3 protein (Davey et al., 2006, 2007). Tickle and colleagues showed that the KIAA0568 mutation responsible for the talpid3 resulted in disorganized basal bodies that are unable to dock with the cell membrane and almost completely lack ciliary axonemes (Yin et al., 2009). Here, we show that the talpid2 mutation is linked to a region on chromosome 1q within the avian ortholog of C2CD3. C2CD3 was first identified via a forward genetic screen for recessive mutations affecting mouse embryonic development (Hoover et al., 2008). hearty and talpid2 mutants both exhibit polydactyly, abnormal dorsal-ventral patterning and craniofacial anomalies, and both mutants have significantly increased levels of GLI3A (Abbott et al., 1959; Agarwala et al., 2005; Hoover et al., 2008). These phenotypic and molecular similarities strongly support our finding that a mutation in C2CD3 is causal for the talpid2 phenotype.

Although the exact function of C2CD3 is currently unknown, recent studies suggest C2CD3 is localized to the distal ends of both mother and daughter centrioles, and is required for the recruitment of centriolar distal appendage proteins (Jakobsen et al., 2011; Balestra et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2014). In vitro analysis further suggests that C2CD3 is required for recruiting the intraflagellar transport proteins IFT88 and IFT52 to the mother centriole, and is essential for ciliary vesicle docking to the mother centriole (Ye et al., 2014). Thus, our data, together with that of others, suggest that the C2CD3 protein regulates intracellular ciliogenesis by promoting the assembly of centriolar distal appendages that are crucial for docking ciliary vesicles and anchoring the centriolar complex to the cell membrane. This is an intriguing hypothesis, as the TALPID3 protein also reportedly functions to anchor the centriole to the membrane (Yin et al., 2009), perhaps via functioning within the transition fibers.

Future studies are needed to elucidate the exact role of C2CD3, primary cilia and GLI trafficking/processing in craniofacial development. The identification of avian C2CD3 opens the possibility that talpid2 may be a relevant model for human disease. Both the talpid2 and talpid3 mutations have provided new insights into craniofacial ciliopathies, which can be used to elucidate the pathways and regulatory mechanisms behind ciliopathic diseases. Interestingly, a number of human craniofacial ciliopathies are caused by mutations in proteins that localize to the distal centriole or proximal axoneme, including Meckel syndrome, Joubert syndrome, nephronophthisis and Senior-Loken syndrome (Reiter et al., 2012). The C2CD3 ortholog in humans is in the HSA11q13.4 chromosomal region, in close proximity to the critical regions for other human ciliopathies, including Meckel-Gruber syndrome 2 (MKS; 603194), Joubert syndrome 2 (JBTS2; 608091) and Nephronophthisis 15 (NPHP15; 614845) (Roume et al., 1998; Hoover et al., 2008; Valente et al., 2010). Thus, the continued examination of the role of C2CD3 has direct relevance for the study of human diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Embryo preparation and measurement of facial prominences

talpid2 heterozygous carriers were mated and eggs were collected. Embryos were incubated at 37°C for 2-7 days. Facial measurements were performed using Leica software. FNP length was defined as the superior aspect of the nasal pit to the distal tip of the FNP. FNP width was defined as the widest aspect of the distal FNP. Infranasal distance was the distance between the medial aspects of the nasal pits. Palatal patency was defined as the length of patency of the palatal shelves. P-values were determined using Student's two-tailed t-test with variance being unequal.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy

Facial and forebrain tissue were collected from control and talpid2 HH20 embryos. Samples were fixed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde, re-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in ethanol, dried, mounted and sputter-coated with 20 nm of gold. Images were collected at 2.0 keV in a Zeiss Supra-35VP FEG.

For transmission electron microscopy, tissue was fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde, washed with sodium cacodylate buffer, post-fixed with 1% OsO4, processed through an ethanol gradient, washed in serial dilutions of plastic (Ladd Research, LX-112)/propylene oxide mixture and moved to 60°C for 3 days. The tissue was sectioned by Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome at 100 nm and put onto 200 mesh copper grids.

Chicken embryonic fibroblast isolation and transfection

Facial prominences and limbs were collected from HH25 control or mutant embryos, and were digested with 1 mg/ml collagenase at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were dissociated, washed in PBS and plated in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 50 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin. Chick embryonic fibroblasts (CEFs) were plated at 70% confluency and transfection was carried out using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Quantitative RT-PCR, RT-PCR and RNA-seq

Facial prominences were collected and pooled from ∼10 control or mutant embryos. RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and cDNA was made using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and a CFX96 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) were used to perform quantitative real-time PCR. All the genes were normalized to GAPDH expression. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. P<0.05 was determined to be significant. Primers included: GAPDH F, CAACATCAAATGGGCAGATG; GAPDH R, AGCTGAGGGAGCT-GAGATGA; C2CD3 F, GAGGAAAGCAGTGAGGTTCTA AA; C2CD3 R, CTCCAGGATGGCAATTCG (amplicon size 782 bp).

For RNA-seq, individual facial prominences were harvested from control (n=8) and talpid2 (n=8) embryos at HH25. RNAs were processed according to recommended procedures, using the Illumina TruSeq and Nugen Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 methods. Sequencing was carried out using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 system according to Illumina protocols. BAM files underwent whole-genome RNA-seq analysis using GeneSpring Version 12.5-GX-NGS. The reference chick genome was taken from Ensembl (4/9/2012). The Audic Claverie test (no correction) was used to identify differentially expressed genes between control and talpid2 facial prominences with a P≤0.05. Heatmaps were generated by GeneSpring after performing the Pathway Analysis function. Raw data have been deposited in GEO under accession number GSE52757.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes, as described on the Gallus Expression in situ hybridization Analysis site (GEISHA) (Bell et al., 2004; Darnell et al., 2007).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed according to standard protocols. Briefly, embryos were fixed in either 100% methanol or DENTS fixative. CEFs were fixed in 4% PFA. Samples were blocked with 10% serum (Millipore) for 30 min at room temperature and incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight and with Alexa Fluor 594Ms or 488Rb secondary antibodies (1:1000; A11020 or A11070; Invitrogen) for 1 h. Slides were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindone (DAPI; 5 μg/ml; Invitrogen) and mounted (ProLong Gold, Invitrogen). Antibodies included rabbit anti-glutamylated-tubulin (1:500; AB3201, Millipore), mouse anti-γ-tubulin (1:1000; T6557, Sigma) and anti-FLAG (1:1000; F1804, Sigma). The percentage of primary cilium extension in CEFs was measured in at least 20 microscopic fields. The P-value was determined using Student's t-test.

Western blot analysis

Facial prominences and limbs were dissected from HH25 control or talpid2 embryos. Tissue was rinsed with ice-cold NaCl and sonicated in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific, #87786). Protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific, #23227) and 30 μg protein was applied to a 6% SDS-PAGE gel. Antibodies used included anti-Gli2 antibody (1:500; R&D, AF3635), anti-Gli3 antibody (1:1000; R&D, AF3690) and anti-β-actin antibody (1:10,000; Abcam, ab8227).

Nuclear fractionation

Facial prominences and developing limbs were dissected from HH 25 chicken embryos. Tissue was rinsed with PBS and digested with 2 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma, C2674). Nuclear fractionation was performed using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce, #78833).

Phosphatase treatment

Total proteins (100 μg) from control facial prominences were collected and treated with phosphatase (New England Biolabs, P0753S) at 30°C for 1 h. Laemmli buffer was added and the sample was boiled at 95°C for 5 min before performing western blot analyses.

Morpholino transfection

Control CEFs were grown to 80% confluency, trypsinized and resuspended in DMEM at a concentration of 1×107/ml. Cells (3×106 in 300 μl) were mixed with either 3 μl of 1 mM control-MO or with two separate C2CD3 translational MOs (C2CD3-MO1, 5′-CTGCATGGCTTCACCTCAAC-GCTT-3′; C2CD3-MO2, 5′-AACAGCCGCCCCGACGGGAGCATCT-3′) to a final concentration of 10 μM. Electroporation was performed using a geneZAPPER 450/2500 system at 950 μF and 200 V. After electroporation, 30 μl of the cells/well were plated on fibronectin-coated (5 μg/cm2) cover slips. Cells were serum starved for 48 h and immunostained. The percentage of ciliary extension in CEFs was measured in at least 20 microscopic fields. P-values were determined using Student's t-test.

Genetic lines, sequencing and analysis

Embryonic samples used for this study were from four genetic lines: the developmental mutant-congenic inbred line talpid2.003 (also known as ta2.003) and its inbred (F>0.99) parent background line UCD003, as well as the talpid2 mutation integrated onto a commercial white leghorn line (CWLL) and the outbred parental genetic background CWLL. The DNA from 10 known talpid2.003 mutants (−/−) and six inbred UCD 003 individuals were isolated and prepared for whole-genome sequencing. Samples were sequenced via NGS by DNA Landmarks (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec, Canada) on the Illumina Hi-Seq platform. Reads were mapped to the reference chicken genome and polymorphisms (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs, small insertion/deletions and structural rearrangements) were called using the CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC bio).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the UC Davis Avian Facility and Jackie Pisenti for husbandry of the talpid2 line. We also acknowledge and thank Jaime Struve for technical support and careful reading of the manuscript, Dr Rashmi Hegde for sequence analysis and protein modeling, Dr Matt Kofron for assistance with microscopy, Georgianne Ciraolo and the CCHMC Pathology core for assistance with TEM, and faculty members of the Division of Developmental Biology at CCHMC for critical discussion of the research project.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

C.-F.C. performed and interpreted most experiments, including immunofluorescence, western blotting, nuclear fractionation, cloning, subcloning, immunoprecipitation, transfection and qRT-PCR. E.N.S. performed facial prominence measurements, in situ hybridization and PCR, and analyzed RNA-seq results. E.A.O., J.D., H.H.C., W.M.M. and M.E.D. performed and analyzed all sequencing data. R.E.E. performed scanning electron microscopy. M.E.D. supplied talpid2 eggs. S.A.B. conceived the project, interpreted experiments and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) [R00-DE01985 to S.A.B.], by C.T.O. funds from the Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation to S.A.B., by the John and Joan Fiddyment Endowment (University of California, Davis) to M.E.D., and by the NRSP-8 National Animal Genome Research Support Program [CA-D*-ASC-7233-RR to M.E.D.]. Deposited in PMC for immediate release.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.105924/-/DC1

References

- Abbott U. K. (1967). Avian developmental genetics. In Methods in Developmental Biology (ed. Wilt F. H., Wessels N. K.), pp. 13-52 New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott U. K., Taylor L. W., Abplanalp H. (1959). A second talpid-like mutation in the fowl. Poult. Sci. 38, 1185. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott U. K., Taylor L. W., Abplanalp H. (1960). Studies with talpid2, an embryonic lethal of the fowl. J. Hered. 51, 195-202. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwala S., Aglyamova G. V., Marma A. K., Fallon J. F., Ragsdale C. W. (2005). Differential susceptibility of midbrain and spinal cord patterning to floor plate defects in the talpid2 mutant. Dev. Biol. 288, 206-220 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C. B., Auerbach W., Lee J. S., Stephen D., Joyner A. L. (2002). Gli2, but not Gli1, is required for initial Shh signaling and ectopic activation of the Shh pathway. Development 129, 4753-4761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestra F. R., Strnad P., Flückiger I., Gönczy P. (2013). Discovering regulators of centriole biogenesis through siRNA-based functional genomics in human cells. Dev. Cell 25, 555-571 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G. W., Yatskievych T. A., Antin P. B. (2004). GEISHA, a whole-mount in situ hybridization gene expression screen in chicken embryos. Dev. Dyn. 229, 677-687 10.1002/dvdy.10503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker L. G. (1997). Strike three for GLI3. Nat. Genet. 17, 259-260 10.1038/ng1197-259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugmann S. A., Allen N. C., James A. W., Mekonnen Z., Madan E., Helms J. A. (2010). A primary cilia-dependent etiology for midline facial disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 1577-1592 10.1093/hmg/ddq030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton P., Davey M. G., Paton I. R., Morrice D. R., Francis-West P. H., Burt D. W., Tickle C. (2004). Craniofacial development in the talpid3 chicken mutant. Differentiation 72, 348-362 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07207006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canettieri G., Di Marcotullio L., Greco A., Coni S., Antonucci L., Infante P., Pietrosanti L., De Smaele E., Ferretti E., Miele E., et al. (2010). Histone deacetylase and Cullin3-REN(KCTD11) ubiquitin ligase interplay regulates Hedgehog signalling through Gli acetylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 132-142 10.1038/ncb2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruccio N. C., Martinez-Lopez A., Harris M., Dvorak L., Bitgood J., Simandl B. K., Fallon J. F. (1999). Constitutive activation of sonic hedgehog signaling in the chicken mutant talpid(2): Shh-independent outgrowth and polarizing activity. Dev. Biol. 212, 137-149 10.1006/dbio.1999.9321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong H. J., Young N. M., Hu D., Jeong J., McMahon A. P., Hallgrimsson B., Marcucio R. S. (2012). Signaling by SHH rescues facial defects following blockade in the brain. Dev. Dyn. 241, 247-256 10.1002/dvdy.23726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox B., Briscoe J., Ulloa F. (2010). SUMOylation by Pias1 regulates the activity of the Hedgehog dependent Gli transcription factors. PLoS ONE 5, e11996 10.1371/journal.pone.0011996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell D. K., Kaur S., Stanislaw S., Davey S., Konieczka J. H., Yatskievych T. A., Antin P. B. (2007). GEISHA: an in situ hybridization gene expression resource for the chicken embryo. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 117, 30-35 10.1159/000103162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey M. G., Paton I. R., Yin Y., Schmidt M., Bangs F. K., Morrice D. R., Smith T. G., Buxton P., Stamataki D., Tanaka M., et al. (2006). The chicken talpid3 gene encodes a novel protein essential for Hedgehog signaling. Genes Dev. 20, 1365-1377 10.1101/gad.369106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey M. G., James J., Paton I. R., Burt D. W., Tickle C. (2007). Analysis of talpid3 and wild-type chicken embryos reveals roles for Hedgehog signalling in development of the limb bud vasculature. Dev. Biol. 301, 155-165 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q., Motoyama J., Gasca S., Mo R., Sasaki H., Rossant J., Hui C. C. (1998). Diminished Sonic hedgehog signaling and lack of floor plate differentiation in Gli2 mutant mice. Development 125, 2533-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ede D. A., Kelly W. A. (1964a). Developmental abnormalities in the head region of the talpid mutant of the fowl. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 12, 161-182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ede D. A., Kelly W. A. (1964b). Developmental abnormalities in the trunk and limbs of the talpid3 mutant of the fowl. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 12, 339-356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz S. C., Anderson K. V. (2010). The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 331-344 10.1038/nrg2774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V., Hamilton H. L. (1951). A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J. Morphol. 88, 49-92 10.1002/jmor.1050880104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycraft C. J., Banizs B., Aydin-Son Y., Zhang Q., Michaud E. J., Yoder B. K. (2005). Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet. 1, e53 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe J. R., Ede D. A. (1968). Abnormalities in bone and cartilage development in the talpid mutant of the fowl. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 19, 327-339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover A. N., Wynkoop A., Zeng H., Jia J., Niswander L. A., Liu A. (2008). C2cd3 is required for cilia formation and Hedgehog signaling in mouse. Development 135, 4049-4058 10.1242/dev.029835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D., Anderson K. V. (2005). Cilia and Hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11325-11330 10.1073/pnas.0505328102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C.-C., Angers S. (2011). Gli proteins in development and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 513-537 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C.-C., Joyner A. L. (1993). A mouse model of greig cephalo-polysyndactyly syndrome: the extra-toesJ mutation contains an intragenic deletion of the Gli3 gene. Nat. Genet. 3, 241-246 10.1038/ng0393-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humke E. W., Dorn K. V., Milenkovic L., Scott M. P., Rohatgi R. (2010). The output of Hedgehog signaling is controlled by the dynamic association between Suppressor of Fused and the Gli proteins. Genes Dev. 24, 670-682 10.1101/gad.1902910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen L., Vanselow K., Skogs M., Toyoda Y., Lundberg E., Poser I., Falkenby L. G., Bennetzen M., Westendorf J., Nigg E. A., et al. (2011). Novel asymmetrically localizing components of human centrosomes identified by complementary proteomics methods. EMBO J. 30, 1520-1535 10.1038/emboj.2011.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. R. (1967). Extra-toes: a nuew mutant gene causing multiple abnormalities in the mouse. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 17, 543-581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie F. R. (1908). The Development of the Chick: an Introduction to Embryology. New York: Henry Holt and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Liu A., Wang B., Niswander L. A. (2005). Mouse intraflagellar transport proteins regulate both the activator and repressor functions of Gli transcription factors. Development 132, 3103-3111 10.1242/dev.01894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCabe J. A., Abbott U. K. (1974). Polarizing and maintenance activities in two polydactylous mutants of the fowl: diplopodia and talpid. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 31, 735-746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucio R. S., Cordero D. R., Hu D., Helms J. A. (2005). Molecular Interactions coordinating the development of the forebrain and face. Dev. Biol. 284, 48-61 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May S. R., Ashique A. M., Karlen M., Wang B., Shen Y., Zarbalis K., Reiter J., Ericson J., Peterson A. S. (2005). Loss of the retrograde motor for IFT disrupts localization of Smo to cilia and prevents the expression of both activator and repressor functions of Gli. Dev. Biol. 287, 378-389 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molla-Herman A., Ghossoub R., Blisnick T., Meunier A., Serres C., Silbermann F., Emmerson C., Romeo K., Bourdoncle P., Schmitt A., et al. (2010). The ciliary pocket: an endocytic membrane domain at the base of primary and motile cilia. J. Cell Sci. 123, 1785-1795 10.1242/jcs.059519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama J., Liu J., Mo R., Ding Q., Post M., Hui C.-C. (1998). Essential function of Gli2 and Gli3 in the formation of lung, trachea and oesophagus. Nat. Genet. 20, 54-57 10.1038/1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Bai C. B., Joyner A. L., Wang B. (2006). Sonic hedgehog signaling regulates Gli2 transcriptional activity by suppressing its processing and degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3365-3377 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3365-3377.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Wang C., Wang B. (2009). Phosphorylation of Gli2 by protein kinase A is required for Gli2 processing and degradation and the Sonic Hedgehog-regulated mouse development. Dev. Biol. 326, 177-189 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. L., Bai C., Platt K. A., Matise M. P., Beeghly A., Hui C. C., Nakashima M., Joyner A. L. (2000). Mouse Gli1 mutants are viable but have defects in SHH signaling in combination with a Gli2 mutation. Development 127, 1593-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson M., Stamataki D., te Welscher P., Andersson E., Böse J., Rüther U., Ericson J., Briscoe J. (2002). Dorsal-ventral patterning of the spinal cord requires Gli3 transcriptional repressor activity. Genes Dev. 16, 2865-2878 10.1101/gad.243402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter J. F., Blacque O. E., Leroux M. R. (2012). The base of the cilium: roles for transition fibres and the transition zone in ciliary formation, maintenance and compartmentalization. EMBO Rep. 13, 608-618 10.1038/embor.2012.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb E. A., Gitter C. L., Cheng H. H., Delany M. E. (2011). Chromosomal mapping and candidate gene discovery of chicken developmental mutants and genome-wide variation analysis of MHC congenics. J. Hered. 102, 141-156 10.1093/jhered/esq122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roume J., Genin E., Cormier-Daire V., Ma H. W., Mehaye B., Attie T., Razavi-Encha F., Fallet-Bianco C., Buenerd A., Clerget-Darpoux F., et al. (1998). A gene for Meckel syndrome maps to chromosome 11q13. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 1095-1101 10.1086/302062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R. A., Hu D., Helms J. A. (1999). From head to toe: conservation of molecular signals regulating limb and craniofacial morphogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 296, 103-109 10.1007/s004410051271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente E. M., Logan C. V., Mougou-Zerelli S., Lee J. H., Silhavy J. L., Brancati F., Iannicelli M., Travaglini L., Romani S., Illi B., et al. (2010). Mutations in TMEM216 perturb ciliogenesis and cause Joubert, Meckel and related syndromes. Nat. Genet. 42, 619-625 10.1038/ng.594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vortkamp A., Gessler M., Grzeschik K.-H. (1991). GLI3 zinc-finger gene interrupted by translocations in Greig syndrome families. Nature 352, 539-540 10.1038/352539a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vortkamp A., Franz T., Gessler M., Grzeschik K. H. (1992). Deletion of GLI3 supports the homology of the human Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS) and the mouse mutant extra toes (Xt). Mamm. Genome 3, 461-463 10.1007/BF00356157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X., Lai C. K., Evangelista M., Hongo J.-A., de Sauvage F. J., Scales S. J. (2010). Kinetics of hedgehog-dependent full-length Gli3 accumulation in primary cilia and subsequent degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1910-1922 10.1128/MCB.01089-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., Zeng H., Ning G., Reiter J. F., Liu A. (2014). C2cd3 is critical for centriolar distal appendage assembly and ciliary vesicle docking in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2164-2169 10.1073/pnas.1318737111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee G. W., Abbott U. K. (1978). Facial development in normal and mutant chick embryos. I. Scanning electron microscopy of primary palate formation. J. Exp. Zool. 206, 307-321 10.1002/jez.1402060302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Bangs F., Paton I. R., Prescott A., James J., Davey M. G., Whitley P., Genikhovich G., Technau U., Burt D. W., et al. (2009). The Talpid3 gene (KIAA0586) encodes a centrosomal protein that is essential for primary cilia formation. Development 136, 655-664 10.1242/dev.028464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young N. M., Chong H. J., Hu D., Hallgrimsson B., Marcucio R. S. (2010). Quantitative analyses link modulation of sonic hedgehog signaling to continuous variation in facial growth and shape. Development 137, 3405-3409 10.1242/dev.052340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Aravind L. (2012). Novel transglutaminase-like peptidase and C2 domains elucidate the structure, biogenesis and evolution of the ciliary compartment. Cell Cycle 11, 3861-3875 10.4161/cc.22068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.