Abstract

This systematic review examines the relationship between late-life spousal bereavement and changes in routine health behaviors. We review six behavioral domains/modifiable risk factors that are important for maintaining health among elderly populations: physical activity, nutrition, sleep quality, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and body weight status. Thirty-four articles were identified, derived from 32 studies. We found strong evidence for a relationship between bereavement and nutritional risk and involuntary weight loss, and moderate evidence for impaired sleep quality and increased alcohol consumption. There was mixed evidence for a relationship between bereavement and physical activity. We identify several methodological shortcomings, and describe the clinical implications of this review for the development of preventive intervention strategies.

Keywords: routine health behaviors, lifestyle change, behavioral change, bereavement, widowhood, older adults

Bereavement refers to a state of having lost a relative or close friend through death. Although bereavement can occur at various ages, it is most common during later life. It is well documented that bereavement is a risk factor for poor mental and physical health. Bereavement is associated with an intense period of suffering (Holmes & Rahe, 1967), excess risk of mortality (Manzoli et al., 2007; van den Berg et al., 2011), and declines in physical and mental health as indicated by illness (Jones et al., 2010), disability (Lee & Carr, 2007), and adverse psychological effects (Utz et al., 2012). These concerns are increased among older adults who are also experiencing declines in physical, mental, and cognitive health by virtue of their age. Preventing bereavement-related health problems among older adults is important because of their prevalence and long-term consequences for the well-being of the survivor.

A wide range of empirical studies have documented the negative health outcomes associated with late-life bereavement (Stroebe et al., 2007). An increasing number of these studies report results related to health behavior change. Although limited, research suggests that behavioral changes following spousal loss (such as being sedentary and gaining or losing weight) may partially account for the onset of bereavement-related health problems (Chen et al., 2005; Williams, 2004).

The transition to widowhood has important consequences for the regulation of health behaviors because of the loss of partner support (Umberson, 1992). Research shows that spouses tend to regulate and encourage each other's behavior, which could be either health-promoting or health-damaging (Reczek & Umberson, 2012; Umberson & Montez, 2010). Understanding the effects of bereavement on changes in routine health behaviors is especially important for the development of effective health promotion programs targeting bereaved elders. Because many health behaviors are modifiable (Brawley et al., 2003), and bereaved elders are motivated to improve their self-care practices (Caserta et al., 2001; Johnson, 2002), understanding the link between health behaviors and bereavement is an important endeavor.

Current Study

The impact of bereavement during late-life is becoming increasingly understood as evidenced by the vast array of articles that have systematically reviewed the field. Numerous reviews have focused on the array of individual factors affecting adjustment (Itzhar-Nabarro, & Smoski, 2012; Onrust & Cuijpers, 2006; Stroebe, 2001; Wortman & Park, 2008); the bereavement – mortality relationship (Bowling, 1987; Stroebe, 1994); and bereavement care interventions (Forte et al., 2004; Wittouck et al., 2011). Numerous reviews of the bereavement literature have been published, yet no systematic review has focused exclusively on bereaved elders’ health behaviors.

The purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive review of the research literature that examined the effect of late-life bereavement on changes in routine health behaviors. Given both the high prevalence and health effects of loss during later life, we focus on late-life bereavement. We also focus on spousal bereavement, owing to the relatively limited amount of research that examines other types of relationship loss (parents, close friends, children) during later life and because the effects of bereavement on health behaviors are most likely to become manifest in spousal relationships. Although women are more likely to experience bereavement, we include studies examining both widows and widowers because of documented gender differences in the adjustment to bereavement (Stroebe et al., 2007). We adopt a broad perspective on health behaviors and include studies assessing five health behaviors that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) emphasizes as essential for the maintenance of health during later life: physical activity, nutrition, sleep, alcohol use, and tobacco use, (U.S. Department HHS, 2008). We also include body weight status as a modifiable risk factor associated with health status during later life (USDHHS, 2008). It is influenced by energy consumed (nutrition) and expended (physical activity). For each study included in the review, we characterize the methods used, summarize the findings and evaluate the quality of the evidence. Standard principles and procedures as outline in the PRISMA Statement were followed (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Liberati et al., 2009). We conclude by identifying gaps in research on this topic that need to be addressed in order to facilitate the development of prevention strategies to protect older adults from adverse changes to health behaviors that accompany the bereavement process.

Method

Search Strategy

The search strategy for relevant studies focused on published articles identified through computerized databases. We searched the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), PsycInfo, and PubMed/Medline databases from 1980-2012 using three sets of terms that were combined using Boolean operators and listed in the title, abstract, or keywords in each database. Search terms were (older adults OR aging OR elderly) AND (bereavement OR widowhood OR spousal loss) AND (health behavior OR physical activity OR exercise OR nutrition OR eating OR alcohol use OR tobacco use OR body weight OR sleep). In addition to the electronic search, reference lists from the identified articles were reviewed for additional studies.

Screening of Articles

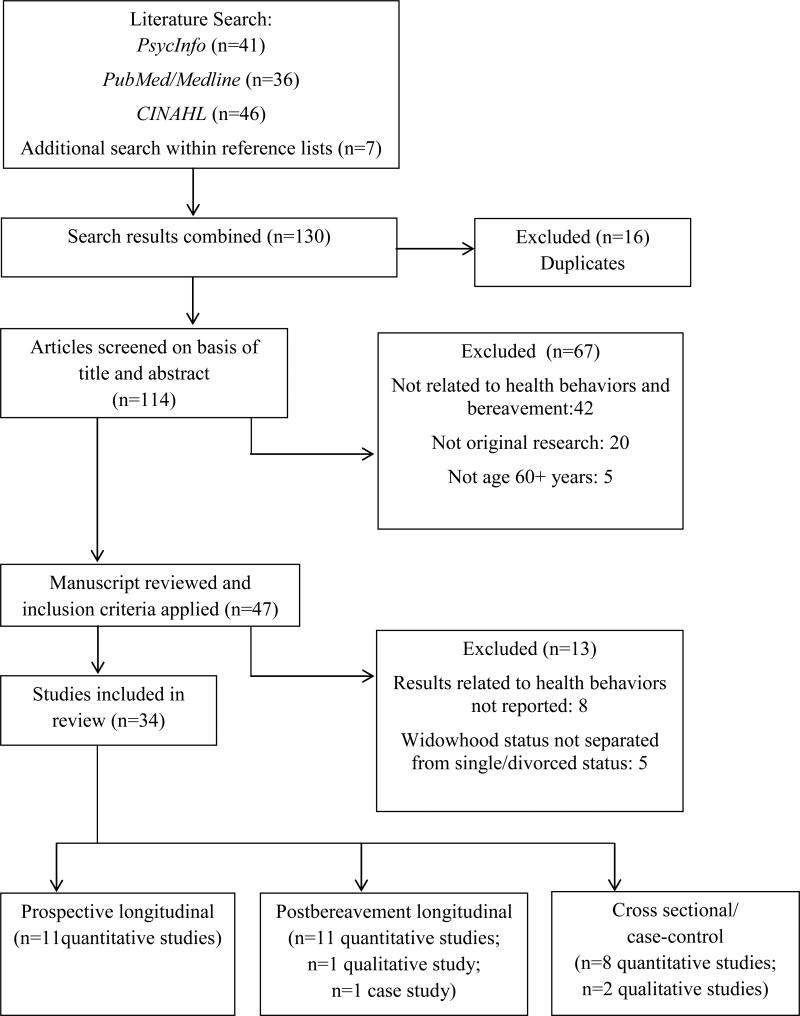

Inclusion criteria for this review were: 1) quantitative and qualitative original studies (intervention and observational); 2) study samples aged 50 years and older; 3) older adults who experienced the death of a spouse; and 4) an assessment of health behaviors (defined above). Papers were excluded if: 1) the study population included participants younger than age 50 (unless the results for those aged 50 and older were presented separately); 2) the study combined bereaved elders with single and/or divorced elders in the analyses (thus making the independent effect of bereavement on health behavior change unknown); and 3) the study did not report results related to one of the six aforementioned health behaviors. Figure 1 summarizes the literature search process.

Figure 1.

Summary of literature search process.

Data Extraction and Analysis

All eligible articles were reviewed independently by each author; the authors then met to discuss findings and a consensus review was completed. Data were extracted from all studies selected with regard to the study population, follow-up duration (if any), type and measurement of health behavior, and results. The nature of the literature makes a quantitative synthesis of the data challenging due to the small number of studies, inclusion of qualitative research, diverse behavioral outcomes, and lack of uniformity in how health behaviors are measured. Therefore, a meta-analysis was not considered informative; instead, results are presented descriptively including the estimation of effect sizes for individual studies that report means and standard deviations for outcome variables.

Results

Identification and Selection of the Literature

The CINHAL, PsycInfo and PubMed/Medline literature searches yielded 133 potentially relevant publications. These 133 papers reported results from 107 distinct studies. After screening the titles and abstracts of these publications, 80 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are shown in Figure 1. Most were excluded because they were reviews, were not related to health behaviors, or were not published in English. An additional eight studies were excluded because they did not report results related to the impact of bereavement on health behaviors. Although we considered all forms of relationship loss, our search yielded studies related to spousal loss (1 study included the loss of a friend). Searching of the eligible articles’ reference lists yielded 7 additional articles for a total of 34 articles that met inclusion criteria. These articles were based on 32 distinct studies; two studies had two publications each, using the same sample in each study but different predictors and/or outcomes (Janke et al., 2008a & 2008b; Patterson, 1996; Patterson & Carpenter, 1994). Thirty one of 33 articles were published in peer-reviewed journals; 3 were published dissertations (eligible articles are marked with an * in the references list of this paper).

Of the 34 articles, 9 focused mainly on physical activity and leisure participation, 7 focused on sleep-related behavior, and 6 focused on eating behavior and dietary intake. Another 4 examined a combination of health-risk behaviors such as unhealthy body weight and smoking (Avis et al., 1991; Nurriddin, 1998; Schulz et al., 2001; Williams, 2004) and 2 articles focused on alcohol consumption only (Byrne et al., 1999; Welte & Mirand, 1995). An additional 6 articles assessed a variety of health-risk and health-promoting behaviors including doctor visits, recreational activity, smoking status, sleep, and fruit/vegetable consumption, among others (Chen et al., 2005; Eng et al., 2005; Lee, et al., 2005; Schone & Weinick, 1998; Tran, 2007; Wilcox et al., 2003). Most of the included studies were quantitative studies; only 3 included qualitative methods, and one was a case study. Most were published after 2000; 14 studies were published between 1990-2000 and one study was published prior to 1990. Most studies were conducted in the United States; four were conducted in Australia, two in Canada, and one in the United Kingdom.

Table 1 provides a detailed description of the sample sizes, age of study participants, types of health behaviors assessed, and main findings of the studies included in this review. Methodological characteristics of the 34 articles are also shown in Table 1; 24 studies were longitudinal and assessed the transition to widowhood and 10 studies reported cross-sectional differences between recently widowed elders and married controls. To better understand the context of the 34 articles, we first describe methodological characteristics including study sampling and measurement tools used to assess health behaviors followed by the synthesis of evidence across each behavioral domain.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Examining Health Behaviors and Late-life Bereavement.

| Study | N | Mean Age (years) | % Female | Sample | Health Behaviors | Measurement Interval (months) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective longitudinal | |||||||

| Avis et al., 1991 * | 2,500 (76 bereaved) | 51.0 | 100 | Subgroup of a population-based sample of women (Massachusetts Women's Health Study; McKinlay et al., 1987) | Health status including (1) exerciser/nonexerciser; (2) smoker/ nonsmoker; and (3) alcoholic beverage consumption | Pre- and post bereavement (NR) | Widows' health behaviors were similar to that of married women. |

| Eng et al., 2005 * | 39,731 (530 bereaved) | 63.7 | 0 | Subgroup of a convenient sample survey of male health professionals (Health Professionals Follow-up Study; Rimm et al., 1991) | (1) Dietary intake including daily intake (kcal) of 131 foods and alcohol; (2) Smoking status; and (3) leisure/physical activity | Pre- and post bereavement (48 months) | Compared to married controls, men who became widowed increased their alcohol consumption, decreased their vegetable intake, and decreased in BMI. |

| Janke et al., 2008a & 2008b | 154 | 68.9 | 89.7 | Subgroup of a nationally representative sample survey (American's Changing Lives Study; House et al., 2005) | Leisure activities, including (1) talking to friends/family; (2) visiting friends/family; (3) clubs/organizations; (4) religious activities; (5) walking; (6) gardening; and (7) sports/exercise | Pre- and post bereavement (NR) | Widow(er)s were most likely to increase their social activities with family and friends and less likely to increase physical activity and gardening activities. |

| Janke et al., 2008c * | 296 (148 bereaved) | 69 | 100 | Subgroup of a women from a nationally representative sample survey (American's Changing Lives Study; House et al., 2005) | Leisure activities, including (1) informal; (2) formal; and (3) physical leisure activities | Pre- and post bereavement (NR) | Widowed women increased their involvement in all activities, whereas continuously married women decreased their involvement in informal and formal activities. |

| Lee et al., 2005 * | 80,944 (8,047 bereaved) | 63.9 | 100 | Subgroup of a random sample survey of registered nurses (Nurses' Health Study2; Colditz et al., 1992) | (1) Dietary intake of 130 foods, including alcoholic; (2) weight change; (3) recreational physical activity (MET-hours/week); (4) smoking status; and (5) mammogram screen during past 2 years | Pre- and post bereavement (48 months) | Compared to married controls, women who became widowed decreased their BMI, increased their alcohol consumption, and decreased their vegetable intake. |

| Schulz et al., 2001 | 129 | 80.1 | 89.9 | Subgroup of a population-based cohort study of spousal caregivers (Caregiver Health Effects Study; Schulz et al., 2001) | (1) Missing at least 1 physician appointment during last 6 mo.; (2) not having enough time to visit physician; (3) not exercising; (4) forgetting medications; (5) not getting enough rest; and (6) not being able to rest | Pre- and post bereavement (48 months) | Compared to caregivers, noncaregivers experienced significant weight loss following bereavement. Caregivers who felted strained experienced a significant decline in health-risk behaviors following bereavement. |

| Shahar et al., 2001 * | 116 | 77.6 | 82.8 | A subgroup of a population-based cohort study (Cardiovascular Health Study; Fried et al., 1991) | (1)Dietary intake of 100+ items; (2)eating behavior and feelings related to eating; and (3) weight change | Pre- and post bereavement (NR) | Relative to married controls, mean weight loss was significantly higher among widowed participants. Widow(er)s ate more meals alone, more commercial meals per week, and enjoyed eating less. |

| Tran, 2007 b | 121 | 75 | 68 | Random sample of community-dwelling adults aged 65 years+ (Canada) | Health-promoting behaviors, including (1) exercise; (2) diet; (3) stress management; (4) Interpersonal relationships; (5) spirituality; and (6) health responsibility | Pre- and post bereavement (NR) | Among all caregivers, experiencing the death of a spouse did not change the frequency of engaging in healthy behaviors. |

| Wilcox et al., 2003 * | 72,247 (16,076 bereaved) | 64.1 | 100 | Subgroup of a nationally representative sample of postmenopausal women (Women's Health Initiative; Women's Health Initiative Study Group, 1998) | (1) Dietary intake, including fruits and vegetables, alcohol, and energy from fat; (2) smoking status; (3) duration of walking (kcal), and (4) duration of moderate to strenuous exercise (kcal) | Pre- and post bereavement (36 months) | Relative to married women, widows weight loss. Recent widows decreased fruit and vegetable intake, and increased fat intake. Longer-term widows slightly increased their physical activity and decreased their tobacco use. |

| Williams, 2004 * | 402 (203 bereaved) | NR | NR | Subgroup of a community representative sample survey (Changing Lives of Older Couples; Carr et al., 2006) | Risky health behaviors, including (1) rarely or never walks/exercises for pleasure; (2) unhealthy body weight; (3) smokes cigarettes; and (d) <7 hours of sleep/24-hr period | Pre- and post bereavement (18 months) | Compared to married controls, widows/widowers increased their engagement in health-risk behaviors following the death of their spouse. |

| Postbereavement longitudinal | |||||||

| Anderson, 1999 *b | 171 (99 bereaved) | 68.1 | 67.7 | Community-dwelling adults aged 60 years (Pittsburgh) | Sleep-related behaviors, including subjective and objective assessments of sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, and sleep disturbances | Post bereavement (12 months), including a 2 week daily diary | Compared to married controls, bereaved elders reported poorer sleep quality. However, no significant differences emerged on objective assessments of sleep. |

| Byrne & Raphael, 1997 * | 114 (57 bereaved) | 74.5 | 0 | A convenience sample of community-dwelling men aged 65 years+ (Australia) | Sleep difficulties, including (1) lost much sleep over worry; and (2) had difficulty staying asleep once asleep | Post bereavement (6 weeks, 6 and 13 months) | Compared to married men, widowed men reported more sleep disturbances. |

| Byrne et al., 1999 * | 114 (57 bereaved) | 74.5 | 0 | A convenience sample of community-dwelling men aged 65 years+ (Australia) | Alcohol consumption, including (1) quantity: drinks/day; and (2) frequency: days/week | Post bereavement (6 weeks, 6 and 13 months) | Compared to married men, widowed men reported greater frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption. |

| Caserta et al., 2001 | 84 | 69 | 85.7 | Community-dwelling adults aged 50 years+ (NR) | Attendance at a health promotion program that included classes on self-care practices such as nutrition, physical activity, stress management, etc. | Pre- and post bereavement (NR) | Widow(er)s attended most of the health promotion classes (8/11) and attended because they were interested in learning how to improve their health. |

| Chen et al., 2005 | 200 | 66.3 | 73.5 | Subgroup of community-dwelling adults (Connecticut) | (1) Exercise (days/week); (2) nutritional supplements; (3) sleep (hours/night); (4) annual medical checkups (yes/no); and (5) caloric intake | Post bereavement (6 and 11 months) | Approximately half of widowed elders consistently slept 6.5-9 hours/night and monitored caloric intake during the first year postloss. Slightly more than half consistently exercised postloss. |

| McIntyre & Howie, 2002 a | 1 | NR | 100.0 | Case study of a spousally bereaved older woman (Australia) | Leisure activities, including daily routines, and social activities | Post bereavement (3 interviews) | Client highlighted that active participation in daily activities was a key factor in her adaptation to widowhood. |

| Monk et al., 2009 * | 47 | 72.3 | 80.9 | Community-dwelling adults aged 60 years+ (Pittsburgh) | Sleep behaviors, including (1) sleep quality; (2) sleep efficiency; (3) sleep latency; (4) wake after sleep onset; and (5) total sleep time | Postbereavement (2 week daily diary) | Compared to married controls, bereaved spouses reported significantly more sleep problems and sleep disturbances. |

| Nurriddin, 2008 b | 1,532 (250 bereaved) | 70.1 | 86 | Subgroup of a community representative sample survey (Changing Lives of Older Couples; Carr et al., 2006) | (1) alcohol consumption; (2) tobacco use; (3) exercise; (4) overeating; (5) drug use; and (6) excessive sleep | Postbereavement (6, 12, and 48 months) | Bereavement was associated with a lack of exercise, increased drinking, eating, excess sleep, and taking of medications. These health behaviors slightly declined with time. |

| Pasternak et al., 1992 | 28 (14 bereaved) | 6 8.1 | 78.6 | Convenience sample of community-dwelling adults aged 60 years+ (Pittsburgh) | Sleep quality, including subjective and laboratory assessments | Post bereavement (6, 10 months) | Bereaved elders showed clinically significant impairments in sleep quality. |

| Quandt et al., 2000 a | 145 | NR | 61 | Ethnographic study of rural adults aged 70 years+ (Rural Nutrition and Health Study; Quandt, et al.,1999) | Dietary interviews, including (1) ways adults obtain food; (2) how adults prepare food including meal type and frequency; and (3) how adults maintain food safety | Post bereavement (within 12 months) | Bereavement had a negative impact on nutritional strategies including meal skipping, reduced home food production, and less dietary variety. |

| Reynolds III et al., 1992 * | 61 (31 bereaved) | 71.8 | 54.8 | Convenience sample of community-dwelling depressed older adults (Pittsburgh) | Sleep efficiency, including subjective and laboratory assessments | Post bereavement (3 consecutive nights) | The sleep of the bereaved (without depression) was similar to that of healthy controls. Bereaved elders with depression had significantly lower sleep efficiency. |

| Reynolds III et al., 1993 * | 54 (27 bereaved) | 68.4 | 70.4 | Convenience sample of community-dwelling adults aged 60 years+ (Pittsburgh) | Sleep quality, including subjective and laboratory assessments | Post bereavement (3, 6, 11, 18, and 23 months) | Bereaved and control groups showed consistent differences over time in REM sleep (higher among bereaved), but were similar on all other sleep measures. |

| Wilcox & King, 2004 | 103 (NR bereaved) | 70.2 | 65.1 | Community-dwelling adults aged 65 years+ (Stanford-Sunnyvale Health Improvement Project II; King et al., 1994) | Participation in one of two health programs: (1) cardio endurance/strength; or (2) stretching/flexibility. Adults were encouraged to participate twice/week as well as two home sessions/week | Postbereavement (up to 12 months) | Across both programs, bereavement was negatively correlated to the number of home exercise sessions, but unrelated to the number or class-based sessions. |

| Cross-sectional | Length of bereavement at time of assessment | ||||||

| Barrett & Schneweis, 1980 | 193 | 74.4 | NR | Representative community sample aged 62 years+ (Wichita) | Nutrition, including mealtime experience and perception of healthy meals. (Note: only nutrition variables that emerged significant were included in the methods and results) | 10 months | Compared to longer-term widows/widowers, recently bereaved elders needed help with food preparation and did not believe they ate nutritional meals. |

| Fitzpatrick et al., 2001 * | 799 (373 bereaved) | 59.7 | 0.0 | Random sample of aging veteran men (Boston Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study; Bosse, et al., 1984) | Leisure activities, including (1) social activities such as meeting with friends, volunteering; (2) solitary activities such as reading, watching TV; and mixed activities such as hobbies, sports | NR | Compared to married men, bereaved men did not differ on measures of leisure activity. |

| Johnson, 2002 *a | 22 (15 bereaved) | 72.0 | 69.0 | Community-dwelling adults aged 60+ (Canada) | Nutritional risk, including (1) following Canada's Food Guide to Healthy Eating, (2) diet meets nutritional needs, and (3) adequate vitamin and mineral supplementation | 30 months | Compared to married controls, bereaved individuals had a moderate risk for poor nutrition and had dietary problems including food acquisition and preparation, place/time for meals, and influence of social network. |

| Okun et al., 2011 * | 222 (39 bereaved) | 71.6 | 79.5 | Convenience sample of community-dwelling adults aged 60 years+ (Aging Well, Sleeping Efficiently; Hall et al., 2008) | (1) Sleep-related behaviors including wake time, bedtime, time in bed, total sleep time; and (2)Health-related behaviors including caffeine consumption, alcohol use, smoking status, and exercise status | NR | Compared to married controls, widow(er)s took fewer naps, had greater variability in total sleep time, and exercised less. Bereaved elders and controls did not differ on in regards to caffeine consumption, alcohol use, and smoking status. |

| Patterson, 1996; Patterson & Carpenter, 1994 | 60 | 64.0 | 71.7 | Non-probability sample of community-dwelling widow(er)s (Australia) | Leisure Activities Scale (LAS), including gardening, socializing, walking, playing sports, participating in organizations/clubs | 6-24 months | Widows and widowers most frequently participated in home-based activities and social activities with family and friends. Participation was lowest in outdoor leisure activities. |

| Rosenbloom & Whittington, 1993 * | 100 (50 bereaved) | 70.2 | 94.0 | Convenience sample of community-dwelling adults aged 60+ (Atlanta) | Eating behavior, including (1) eating along; (2) meal skipping; (3)adequacy of morning meals; and (4)food diversity | within 24 months | Widowhood altered the social meaning that eating held for older adults and produced negative effects on eating behaviors and nutrient intakes. |

| Schone & Weinick, 1998 * | 4,443 (1,720 bereaved) | 76.3 | 84.0 | Subgroup of a nationally representative sample of noninstitutionalized older adults (National Medical Expenditure Survey; Edwards & Berlin, 1989) | Health promoting behaviors, including (1) checking blood pressure annually; (2) engaging in moderate/ strenuous physical activity; (3) eating breakfast; (4) seatbelt use; and (5) not smoking | NR | Relative to married controls, widow(er)s were less likely to engage in physical activity, eat breakfast, wear a seat belts, and abstain from smoking. |

| Welte & Mirand, 1993* | 2,325 (674 bereaved) | NR | 66.0 | Representative community sample aged 60 years+ (Erie county, New York) | Alcohol consumption, including (1) quantity and frequency of beer, wine, and distilled spirits; (2) signs of alcohol dependence such as binge drinking | NR | Stressful life events, including bereavement were not associated with current alcohol consumption or late-onset problem drinking. |

| Wylie et al., 1999 a | 15 | 80.6 | 80.0 | Convenience sample of older adults with restricted mobility (United Kingdom) | Dietary interviews, including (1) meal patterns; and (2) food consumption | NR | Bereavement had a negative impact on food intake including forgetting to eat, eating less, and not wanting to prepare or eat food alone. |

NR = not reported; kcal = kilocalories; REM = rapid eye movement; BMI = body mass index.

Case-control design.

Includes qualitative methodology.

Published dissertation.

Study Sampling –Generalizability of Findings

The vast majority of studies used non-probability sampling techniques. Seventeen studies were conducted with convenience samples recruited from communities that included adults aged 60 years and older. Several studies used focused convenience samples and recruited a specific demographic consistent with their study goals; these included male health professionals (Eng et al., 2005), registered nurses (Lee et al., 2004), veteran men (Fitzpatrick et al., 2001), spousal caregivers (Schulz et al., 2001), and depressed volunteers (Reynolds III et al., 1992) and pre-menopausal women (Avis et al., 1991). The remaining 11 studies were a subgroup of a representative sample of elders who became widowed while participating in a larger epidemiological study (e.g., American's Changing Lives Study, Cardiovascular Health Study, Changing Lives of Older Couples, etc.).

Overall, most studies were conducted with White, non-Hispanic samples, yet most epidemiological studies were conducted with samples that included multiple ethnic groups. However, no studies particularly focused on older adults from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds. Most studies included both widows and widowers; however an overwhelming majority of samples consisted of widowed women (76%), which is consistent with population estimates indicating spousal bereavement is most frequent among women (National Center for Health Statistics, 2009). Ten studies were sex specific and consisted of women (n=5) or men only (n=5). Although age of widowhood or age of decedent are not explicitly reported, they can sometimes be inferred from information provided about the sample (age at recruitment, M=68 years) and procedures of the study (e.g., timing of follow-up assessments).

Measurement Tools used to Assess Health Behaviors

Of the studies reporting physical activity, all were self-reported estimations of participation in a number of activities that varied across studies. Examples of activities included leisure activities: visiting with friends and family, attending clubs or organizations, volunteering; and physical activities: walking, gardening, physical exercise, and active sports (Fitzpatrick, 2001; Janke et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2008c; Wilcox et al., 2003). Other studies used either a single-item to assess physical activity, including “How many days/week do you exercise” (Chen et al., 2005); or created a dichotomous indicator differentiating between those who had time to walk/exercise from those who never participated (Okun et al., 2011; Schulz et al., 2001; Williams, 2004). Two studies assessed class attendance at a community-based exercise program (Caserta et al., 2001;Wilcox & King, 2004). The only formal instrument used to measure frequency of participation in physical activity was the Leisure Activity Scale (LAS) used in one study (Patterson, 1996; Patterson & Carpenter, 1994) but no psychometric properties were reported. Three studies converted self-reports of physical activity into metabolic equivalent hours (MET) per week, a measure of energy expenditure associated with physical activity participation (Eng et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2004; Wilcox et al., 2003).

Qualitative and quantitative methods were used to assess two aspects of nutritional risk: nutritional intake and dietary behaviors. A range of validated instruments were used including the National Cancer Institute-Health Habits and History Questionnaire (Block et al., 1990), the Nutritional Risk Index (McIntosh et al., 1989), the Food Frequency Questionnaire (Lee et al., 2004) and questions developed by Rosenbloom and Whittington (1993) to gauge diet quality including eating alone, meal skipping, adequacy of the morning meal, and food diversity. Two studies included a single-item assessing whether participants ate breakfast (Schone & Weinick, 1998) or the extent to which they monitored their caloric intake (Chen et al., 2005). The qualitative studies’ semistructured interviews included topics such as acquisition of food, food preparation, and difficulties meeting nutritional needs (Johnson, 2002; Quandt et al., 2000; Wylie et al., 1999).

Measurement of sleep included both self-report and objective assessments. The most common instrument used to measure sleep was the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989), which evaluates sleep quality along seven dimensions (self-reported sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction). Objective estimates of sleep were assessed in several studies by conducting overnight laboratory sleep assessments using polysomnography and electroencephalographic (EEG) evaluations (Anderson, 1999; Pasternak et al., 1992; Reynolds et al., 1992; Reynolds et al., 1993); two studies used actigraphy to monitor rest/activity cycles (Monk et al., 2009; Okun et al., 2011).

Alcohol consumption was measured in seven studies (Avis et al., 1991; Byrne et al., 1999; Eng et al., 2005; Johnson, 2002; Lee et al., 2004; Nurriddin, 2008; Welte & Mirand, 1995) using the quantity/frequency method for beer, wine, and spirits. One study included an assessment of alcohol dependence and alcohol-related consequences (Welte & Mirand, 1995), and another assessed the validity of self-reported alcohol consumption by drawing blood samples to measure serum liver enzyme levels (Byrne et al., 1999). Tobacco use was assessed in eight studies by asking participants to report their smoking status as ‘never, past, or current’, and if applicable, daily cigarette consumption (Avis et al., 1991; Eng et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2004; Nurriddin, 2008; Okun et al., 2011; Schone & Weinick, 1998; Wilcox et al., 2003; Williams, 2004). Finally, body weight status was measured in six studies using either participants’ current weight (lbs) (Schulz et al., 2001; Shahar et al., 2001) or body mass index (BMI) (Eng et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2004; Wilcox et al., 2003; Williams, 2004). Two studies used the adult body mass index formula (kg/m2) recommended by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2009) to define unhealthy body weight (<18.5 = underweight and >25 = overweight and obese). Three studies used clinical assessments of body weight status (Schulz et al., 2001; Shahar et al., 2001; Wilcox et al., 2003), and three used self-reports of body weight status (Eng et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2004; Williams, 2004).

Synthesis of Evidence

Thirty-four studies were included in our review, consisting of 10 cross-sectional studies that compared health behaviors on the basis of marital status, 11 prospective longitudinal studies that included assessments pre and post-bereavement, and 13 post-bereavement longitudinal studies with multiple assessments after death but no pre-death assessment. Within each behavioral domain, we present below a summary of findings for the relationship between bereavement and health behaviors (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Direction of Effects Reported for 6 Health Behaviors by Study (n=34).

| Health Behavior | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Physical activity | Nutrition | Sleep quality | Alcohol intake | Tobacco use | Body weight | ||

| Type of study | # of waves | d | ||||||

| Prospective longitudinal* | ||||||||

| Avis et al., 1991bb | 2 | - | stablec | no change | stable | |||

| Eng et al., 2005 a | 2 | .03, .25, .06, -, .50 | decreasedcd | worsened | increased | decreased | decreased | |

| Janke et al., 2008a & 2008b | 2 | - | decreasede | |||||

| Janke et al., 2008c b | 2 | .13 | increasedd | |||||

| Lee et al., 2005 b | 2 | - | increasedc | worsened | increased | increased | decreased | |

| Schulz et al., 2001 | 2 | .62, .50 | increasedcg | decreasedh | ||||

| Shahar et al., 2001 | 2 | .97, 1.20 | worsened | decreased | ||||

| Tran, 2007 | 2 | - | stablec | stable | ||||

| Wilcox et al., 2003 b | 2 | .04, .19, .02, .02 | increasedc | worsened | decreased | decreased | ||

| Williams, 2004 | 2 | - | ^ | ^ | ^ | ^ | ||

| Postbereavement longitudinal* | ||||||||

| Anderson, 1999 | 2 | 1.42 | declined | |||||

| Byrne & Raphael, 1997 a | 3 | .48 | declined | |||||

| Byrne et al., 1999 a | 3 | .43 | increased | |||||

| Caserta et al., 2001 | 2 | .67 | decreasedc | |||||

| Chen et al., 2005 | 2 | - | stablec | worsened | stable | |||

| McIntyre & Howie, 2002 b | 3 | - | stabled | |||||

| Monk et al., 2009 | 14 | 1.41 | declined | |||||

| Nurriddin, 2008 | 3 | .08, .51, .28, .02 | decreasedc | worsened | increased | stable | ||

| Pasternak et al., 1992 | 2 | 1.11 | declined | |||||

| Quandt et al., 2000 | 5 | - | worsened | |||||

| Reynolds III et al., 1992 | 3 | 1.27 | declined | |||||

| Reynolds III et al., 1993 | 5 | .46 | stable | |||||

| Wilcox & King, 2004 | 3 | .38 | decreasedbf | |||||

| Type of study | Control group | d | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional* | ||||||||

| Barrett & Schneweis, 1980 | no | .34 | NR | |||||

| Fitzpatrick et al., 2001 a | yes | .12 | no differencecd | |||||

| Johnson, 2002 | yes | .92 | worsened | |||||

| Okun et al., 2011 | yes | .15, .65, .01, - | decreasedc | declined | no difference | stable | ||

| Patterson, 1996; Patterson & | no | - | decreasedc | |||||

| Carpenter, 1994 | increasedd | |||||||

| Rosenbloom & Whittington, 1993 | yes | 1.75, 1.60 | worsened | decreased | ||||

| Schone & Weinick, 1998 | yes | .92,.73, .70 | decreasedc | worsened | increaseda | |||

| Welte & Mirand, 1993 | yes | - | no difference | |||||

| Wylie et al., 1999 | no | - | worsened |

NR=did not report results in reference to a control sample. Effect sizes were estimated for quantitative studies that reported means and standard deviations for outcome variables.

Results are reported for widowed elders across time.

Results are reported for widowed elders in reference to a control sample.

Did not report results that allowed for the estimation of effect sizes.

This study created a “health-risk” variable by summing 4 behavioral variables. Widowhood was associated with an increase in health-risk behaviors, but the effect of bereavement on each of these health behaviors was not reported.

Significant effect reported for widowed men only.

Significant effect reported for widowed women only.

Sports/exercise activity.

Leisure/social activity.

Physical activity and exercise only; elders increased their social activities across time.

Class-based exercise only; home-based exercise remained stable.

Among caregivers (who experienced strain) only.

Among noncaregivers only.

Physical Activity

Cross-sectional studies

Four studies examined differences in physical activity between bereaved elders and married controls. Two studies reported a negative effect of bereavement status on physical activity, one reported a positive effect, and one reported no difference. Okun et al. (2011) found that bereaved elders were less likely to endorse regular exercise compared to married controls, while Schone & Weinick (1998) found similar findings, but only among men and not women. Patterson (1996) found that widowed elders reported more engagement in social and leisure activities, but less engagement in sports and exercise (significance test not reported). On the other hand, the study by Fitzpatrick et al. (2001) found no significant difference between bereaved and married men across a variety of leisure activities including social activities with friends, sports, and exercise. However, men who experienced the loss of a spouse, friend, and/or family member were all included in the bereaved sample; the independent effect of each bereavement type on leisure activity was not reported.

Prospective longitudinal studies

Eight studies examined longitudinal change in physical activity pre- to postbereavement. Four studies reported an increase in activity following the transition to widowhood, two reported a decrease, and two reported no change. The study of Janke et al. (2008c) found that among women, widows increased their leisure activities following spousal loss, which included talking with others, visiting with friends, and religious activities. A second study of women similarly found an increase in walking and strenuous exercise. However, this effect was observed among longer-term widows only; compared to continuously married women, recent widowers slightly decreased their activity (Wilcox et al., 2003). Lee et al. (2004) also reported a slight increase in physical activity (MET/week) among women, but this effect was not statistically significant. Bereaved elders who experienced caregiver strain prior to spousal death were more likely to engage in exercise (bereaved noncaregivers showed relatively little change) (Schulz et al., 2001).

Conversely, the studies of Janke et al. (2008a, 2008b) found that widow(er)s reduced the total number of leisure activities in which they participated, and the overall frequency with which they engaged in them. However, widowed elders were most likely to continue their engagement in activities that included talking and visiting with friends, and a small proportion increased their involvement in sports and exercise following spousal loss (significance test not reported). Similarly, Eng et al. (2005) found that over a 4-year marital history, the transition to widowhood was associated with decreased leisure time and routine physical activity among men (METs/week). Of the two studies that did not find a significant effect, one study (Tran, 2007) used an index of physical activity that collapsed across a variety of specific behaviors (use of a planned exercise program, heart rate monitoring, strenuous exercise), and as a result did not examine the effect of spousal loss on each of these dimensions separately; and another study (Avis et al., 1991) examined exercise status only (engage versus do not engage) and did not examine the frequency of physical activity.

Postbereavement longitudinal studies

Another five studies examined postbereavement change only; three reported a decrease in activity following spousal loss, and two found no change (stability). Among women, Wilcox and King (2004) found that widows who experienced spousal loss decreased their participation in both home- and class-based exercise sessions during a 12 month postloss exercise program (effect was not statistically significant). Similarly, Caserta et al. (2001) found that the length of widowhood was associated with decreased attendance at a health promotion program; indicating that more recent widow(ers) were likely to attend because they were interested in learning new behavioral strategies to maximize their health. The study of Nurriddin (2008) had a longer follow-up, namely 2 years postloss, and found that exercise continued to decrease, especially among elders who did not have a history of physical activity and exercise. On the other hand, Chen et al (2005) found no significant change postloss; most widowed elders reported consistent exercise at least 1 day/week from 6- to 11-months postloss. Lastly, in a case study by McIntyre and Howie (2002), the widowed client highlighted that her continuity in meaningful activities including active participation in daily routines were crucial factors assisting her adjustment to widowhood.

Evidence synthesis

Based on the mixed findings from these 18 studies, there is inconsistent evidence for a relationship between bereavement and physical activity. Small to large effect sizes were calculated (d range = .03 – .92). It is important to note that these inconsistencies likely reflect the variations in the conceptualization of physical activity and array of methods used to measure activity. Despite these limitations, prospective studies suggest that the effect of bereavement varies by the specific activity outcome examined and participant gender. There appear to be differential effects of bereavement on leisure/social activities when compared to sports/exercise activities. Studies suggest that bereavement is associated with an increased change in leisure/social activities and decreased change in sports/exercise activities. Prospective studies also suggest that gender may be a strong effect modifier. Studies that include an analysis by gender suggest similar findings among women; but men are more likely to decrease their participation in all types of activities. Postbereavement evidence among men and women is more consistent and suggests activity levels, namely sports/exercise, decrease as time passes following spousal loss. The latter finding may not be related to bereavement per se, as it could be the result of normative aging processes in that older adults tend to normatively decrease their activity with increasing age regardless of bereavement status (Prohaska et al., 2006)

Nutrition

Cross-sectional

Five studies examined differences in nutritional intake between bereaved elders and married controls. All five indicated that bereavement status was associated with poor eating behaviors and nutrient intake. Rosenbloom & Whittington (1993) found bereavement status to be associated with nutritional quality (servings of fruits, vegetables, fats, etc.), and eating behavior (eating alone, skipping meals, low food diversity). The study of Johnson (2002) similarly found bereaved elders to be at moderate nutritional risk compared to married controls, and Schone & Weinick (1998) found an effect of bereavement status on skipping breakfast, but among women only. Compared to longer-term widow(er)s, Barrett & Schneweis (1980) found that recently bereaved elders needed help finding information on food preparation and did not believe they ate nutritious meals. Qualitative analyses identified significant themes surrounding 1) skills related to shopping and preparing food, 2) the social significant of eating, and 3) general nutritional quality (Wylie et al., 1999; Johnson, 2002).

Prospective longitudinal

Five studies examined longitudinal change in nutrition pre- to postbereavement. Four studies found an increase in nutritional risk following the transition to widowhood, and one found no change. The study of Shahar et al. (2001) found that the transition to widowhood was associated with decreased intake of vitamins A and E, and poorer eating behaviors, including eating meals alone, eating more commercial meals and fewer home-cooked meals. Widowed elders also reported less enjoyment of eating. Among men, those who became widowed during a 4 year marital history decreased their weekly intake of vegetables; this effect was more pronounced among younger than older men. Widowed men also increased their frequency of eating fried foods away from home. Similarly, Lee et al. (2004) found that widows had a lower intake of food (overall caloric intake) and specifically decreased vegetable intake relative to women who stayed married over a 4 year period. In another study of women, Wilcox et al. (2003) found that women who became widowed decreased their fruit and vegetable consumption and increased their fat consumption relative to women who remained married. One study that did not find a significant effect for nutrition (Tran, 2007): however the outcome variable was an index of health-promoting behaviors that combined dietary behaviors with 5 other behavioral outcomes.

Postbereavement longitudinal

Another three studies examined postbereavement change only. All three reported an increase in nutritional risk following spousal loss. The study of Chen et al. (2005) found that bereaved elders were less likely to monitor their caloric intake from 6 to 11 months postloss (p value not reported). A qualitative analysis during the first year of spousal loss (Quandt et al., 2000) found that bereavement was associated with changes in nutritional self-management, including 1) meal skipping, 2) reduced home food production, and 3) less dietary variety. During a longer follow-up of two years postloss, Nurridin found that compared to controls, bereaved elders reported overeating at 6 months postloss, but this effect decreased over time.

Evidence synthesis

Based on the consistent findings from 12 studies identified, there is strong evidence for a relationship between bereavement and increased nutritional risk, including poor dietary behaviors and worsened nutrient intake. Large effect sizes were primarily calculated (d range = .25– 1.6). Cross-sectional findings indicate bereaved elders are at increased nutritional risk compared to married controls while longitudinal findings point to the strong association between the transition to widowhood and significant decrements in a variety of nutrition-related behaviors. The negative effect of bereavement on nutritional risk appears to be strongest during the first year postloss.

Sleep Quality

Cross-sectional

One cross-sectional study found that widowed elders took fewer naps and exhibited poorer sleep compared to married controls (Okun et al., 2011).

Prospective longitudinal

No prospective sleep studies were identified.

Postbereavement longitudinal

Eight studies examined postbereavement change only. Six studies found that sleep quality declined following bereavement, and two found no change. Pasternak et al (1992) found that subjective sleep quality (prolonged sleep latency, daytime dysfunction) was worse among bereaved elders during the first 6 months postloss compared to controls. However, no significant differences in objective measures of sleep (EEG) emerged, except among bereaved elders with subsyndromal depression symptoms. Anderson (1999) included a longer follow-up time, namely 12 months postloss, and found that compared to controls, bereaved elders self-reported poorer sleep quality. However, there was no significant difference between bereaved elders and married controls on objective EEG assessments of sleep across time. Likewise, during the first 13 months postloss, Byrne & Raphael (1997) found that among men, widowers reported significantly more sleep disturbances, including losing sleep over worry and having difficulty staying asleep. The study of Monk et al. (2009) found that during a two week period postbereavement (time since spousal loss not reported), bereaved elders reported more sleep problems and sleep disturbances compared to married controls. Again, there were no significant differences between bereaved elders and controls on objective Actigraphy results. Lastly, Reynolds III et al (1992) found that sleep quality (subjective and objective) of the bereaved (without depression) was similar to that of healthy controls. However, bereaved elders with depression had significantly lower sleep efficiency.

Of the two studies that did not find a significant relation between time since spousal loss and sleep, one study hypothesized that no significant effect emerged within 2 years postloss because the sample of bereaved elders did not develop major depression during this time, which is strongly related to sleep (Reynolds III et al., 1993). The other study (Chen et al., 2005) did not measure sleep quality per se; participants self-reported the number of hours they slept/night, and less than half (44%) reported consistently sleeping 6.5-9 hours/night from 6- to 11-months postloss.

Evidence synthesis

Based on the consistent findings from the 9 studies identified, there is some evidence for a long-term negative effect of bereavement on sleep quality. Medium to large effect sizes were calculated (d range = .48 – 1.42). Longitudinal evidence shows that compared to married controls, bereaved elders subjectively report more sleep problems and sleep disturbances over time. Interestingly, no significant differences on objective measures of sleep emerged. Prospective studies are needed to determine if the transition to bereavement is an independent risk factor for the development of poor sleep.

Alcohol Consumption

Cross-sectional

In two cross-sectional studies of alcohol consumption, no significant difference emerged in the frequency of alcohol consumption between bereaved elders and married controls. However, it was unclear whether the sample consisted of recent or longer-term widowers, which may have influenced the onset of drinking behaviors (Okun et al., 2011; Welte & Mirand, 1993).

Prospective longitudinal

Three studies examined longitudinal change in alcohol consumption from pre- to postbereavement. Two studies reported an increase in alcohol consumption following the transition to widowhood, and one reported no change. Lee et al. (2004) found that among alcohol abstainers at baseline, women who became widowed during a 4 year assessment were more likely to start drinking compared to women who remained married. Eng et al. (2005) found that among men, becoming widowed was associated with increased alcohol consumption (.51 servings of alcohol/week) relative change in men who stayed married. A similar but non-significant trend was observed for the relationship between widowhood and alcohol consumption in the study of Avis et al. (1991).

Postbereavement longitudinal

Similar findings emerged among the two studies that examined postbereavement change only. Byrne et al. (1999) found that among men, recently widowed older men reported greater frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption than married controls during the first 13 months of bereavement. In addition, a significant minority (19%) reported hazardous levels of alcohol consumption (5+ drinks/day) (Byrne et al., 1999). During the first 2 years postloss, Nurriddin (2008) found a similar effect among men; widowers were more likely to consume alcohol than married men.

Evidence synthesis

Based on the findings from 7 studies identified, there is moderate support for a relationship between the transition to bereavement and increased alcohol consumption. Medium effect sizes were calculated (d range = .28 - .43). Cross-sectional findings do not find significant effects, yet the prospective studies indicate that men and women are equally at risk for increased alcohol consumption following spousal loss. One study suggests bereavement may pose serious long-term effects for hazardous drinking during the first year postloss, but only among men.

Tobacco Use

Cross-sectional

Two cross-sectional studies examined smoking status. Schone & Weinick (1998) found a significant effect of bereavement on smoking status (current smoker), but among men only, while no significant differences in smoking frequency emerged in the study of Okun et al. (2011) .

Prospective longitudinal

Four studies examined longitudinal change in smoking status from pre- to postbereavement. Two found a significant decrease in tobacco use, one found an increase, and one found no change. The study of Eng et al. (2005) found that among current smokers (men only), widowhood was associated with decreased cigarette use (-.42 cigarettes/day) compared to continuously married men. Wilcox et al (2003) found that among current smokers, widows showed a decline in tobacco use when compared to continuously married women. In contrast, Lee et al. (2004) found that among non-smokers, the odds of starting smoking were two times greater in women who became widowed. In addition, among smokers, women showed a significant increase in cigarette use (-.52 cigarettes/day) compared to married women. The one study that did not find a significant effect (Avis et al., 1991), examined women who were primarily middle-aged (M age at widowhood = 51 years).

Postbereavement longitudinal

During the first two years postloss, Nurriddin (2008) found that widowed men increased their daily cigarette use, while women were less likely to smoke as time passed following spousal loss.

Evidence synthesis

Based on the mixed findings from the 7 identified studies, there is inconsistent evidence for a relationship between bereavement and tobacco use. Small to large effect sizes were calculated (d range = .02 - .70). These inconsistencies may be attributable to elders’ initial smoking status and gender. Among current smokers, evidence suggests bereavement is associated with decreased smoking frequency, particularly among men (conflicting results were reported among women). Among non-smokers, the likelihood of starting to smoke increased for women following bereavement. The effect of bereavement on smoking may be temporary, as one study showed that the long-term effect of bereavement on tobacco use was nonsignificant.

Weight Status

Cross-sectional

Rosenbloom and Whittington (1993) found that bereaved elders self-reported more unintentional weight loss (7.64 pounds) compared to married controls.

Prospective longitudinal

Five studies examined longitudinal change in weight status from pre- to postbereavement. All found a significant association between spousal loss and weight loss. The study of Wilcox et al. (2003) found that women who became widowed reported an unintentional weight loss of 5 pounds or greater, and this effect was significantly larger among recent than among longer term widows. Schulz found that among noncaregivers, widowed elders lost approximately 3.8 pounds following the death of a spouse (no significant weight change emerged among caregivers). Shahar et al (2001) likewise found that widowhood increased the risk for weight loss, even after controlling variables such as baseline weight, years of widowhood, depression, and frequency of eating alone. In another study, women who became widowed across a 4 year span had a mean BMI decrease of -.44 kg/m2 relative to the change in women who stayed married (Lee et al., 2004). Similarly, but among men, those who became widowed had a mean BMI decrease of -.35 kg/m2 relative to the change in men who stayed married across a 4 year marital history (Eng et al., 2005).

Postbereavement longitudinal

No postbereavement studies were identified.

Evidence synthesis

Based on the consistent evidence from the 6 studies identified, there is strong evidence for a negative relationship between bereavement and weight status. Medium to large effect sizes were calculated (d range = .50 – 1.6). Cross-sectional evidence shows significant weight differences between widow(er)s and married controls, while longitudinal evidence shows that bereavement is a significant risk factor for body weight variables including unintentional weight loss and declines in BMI status. However, the long-term effect of bereavement on weight status is unknown.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to systematically summarize the research literature with regard to the relationship between bereavement and changes in routine health behaviors, taking into account key design features of the studies. Twenty of the 34 identified studies were published after 2000 demonstrating the increased attention to this area, highlighting the need for a systematic review. The cumulative results from this review support the need for the continued inclusion of health behavior assessments in studies of bereavement and the future development of behavioral prevention programs targeting spousally bereaved elders.

The first notable finding is the strong relationship between bereavement and increased nutritional risk. Common dietary behavioral changes included eating alone, skipping meals, eating fewer home cooked meals and eating more commercial meals following spousal loss. Widowed elders’ nutritional intake was also poor; they ate fewer servings of fruits and vegetables, more servings of fat, and consumed fewer vitamins and minerals. Importantly, nutritional risk appeared to increase over time. Widowed elders’ worsened nutritional intake is likely related to their significant decline in weight status. Bereavement is strongly associated with unintentional weight loss and declines in BMI. However, whether weight changes are temporary or whether they persist over time is unknown. The evidence also suggests that subjective sleep quality of the bereaved is worse relative to married controls, but there are no prospective studies demonstrating this effect. Sleep problems reported during the first year of bereavement included difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and losing sleep over worry. Men and women were equally at risk for increasing their alcohol consumption following spousal loss. Importantly, alcohol consumption continues to increase during the first year postloss, but only among men. Lastly, widowed elders tend to increase their participation in leisure/social activities and decrease their participation in sports/exercise activities following spousal loss. Sports/exercise activities continue to decrease during the first year postloss. Our effect size calculations show that large effects were found in studies that measured nutrition and sleep, medium effects in studies that reported weight status and tobacco, and small effects in studies that measured physical activity and alcohol consumption.

Mechanisms of Behavior Change

Across all behavioral domains, mechanism which might account for increased behavioral risk include the loss of social/partner support and the decreased social regulation of health (i.e., health-related reminders from significant others [Umberson, 1992]), and the impact of grief and depression reactions on elders’ ability to engage in self-care behaviors. Grief and depression reactions may undermine bereaved elders’ motivation to engage in health-promoting behaviors, and may also trigger physical symptoms (sleep disturbances, headaches, chest pain) that impair daily functioning, including routine health behaviors. Physical activity studies assert that engagement in activity serves as a coping mechanism by which to remain socially connected and experience positive affect. However, activities that are commonly shared among partners may be difficult to maintain in the absence of the deceased and therefore decline following bereavement (Janke et al., 2008a, 2008b; Williams, 2004). Nutrition studies agree that bereavement dramatically changes elders’ social environment, which triggers changes in their daily routines associated with food preparation and eating (Rosenbloom & Whittington, 1993; Shahar et al., 2001). Following spousal loss, food preparation and eating no longer deliver pleasure, fostering a lack of interest and enjoyment in in activities associated with eating. Consequently, the lack of interest in food preparation and eating likely contribute to the unintentional weight loss experienced by elders during the first year postloss. Sleep studies suggest that bereavement may elicit change to elders’ sleep-related behaviors, particularly sleep onset, because of the salience of co-sleeping during the spousal relationship (Monk et al., 2009). The sleep environment also changes following spousal loss, as widowed elders likely spent decades going to bed each night with their spouse. Therefore, bedtime routines and the sleeping environment may continuously remind the elder of their lost spouse, and trigger sleep problems, such as difficulty falling and staying asleep. Alternatively, it could be tested that sleep might improve under circumstances where the deceased spouse disrupted sleep of their partner because of illnesses such as Alzheimer's disease.

Although limited, research suggests that behavioral changes following bereavement may partially account for the adverse health outcomes among surviving spouses (Byrne & Raphael, 1997; Janke et al., 2007, 2008a, 2008b; Johnson, 2002; McIntyre & Howie, 2002; Pasternak et al, 1992; Reynolds et al., 1992; Quandt et al., 2007). Preventive interventions may be more likely to show clinically significant effects by targeting multiple mechanisms aimed at preventing unwanted behavioral change. Considerable research has identified strategies and challenges with facilitating behavioral change among older populations (e.g., Brawley et al., 2003; Rothman, 2006). Researchers should explore whether existing models of behavior change can be adapted to the context of bereavement.

Suggestions for Future Research

Based upon the findings from this review, we provide several suggestions for researchers to consider when testing the effects of bereavement on health behavior change. We identify several methodological shortcomings, and describe the clinical implications of this review on the development of preventive intervention strategies.

Methodological Considerations

There are several design and measurement issues worth mentioning. First, the majority of studies measured health behaviors, with the exception of sleep, by self-report only and by different recall periods (within the last year, week, or typical day). Objective assessments that are intended for specific behavioral domains, such as physical activity and alcohol consumption (e.g., accelerometers such as ActiGraph ,GeneActiv and alcohol sensors such as ScramX), may offer a valuable supplement to traditional self-report measures among aging populations because they avoid recall bias. Second, most studies (32 of 34) did not report effect sizes (Cohen's d), which are important for quantifying the difference between groups (Cohen, 1994). Few studies reported statistics (F, t values) that allowed us to calculate effect sizes. Several physical activity studies combined physical activities with social activities - which may or may not have involved physical exercise. Among activity measures being used, investigators should explicitly describe the instruments and differentiate between leisure/social activities and physical/exercise activities.

Another methodological issue that needs to be addressed concerns measurement intervals used pre-and post-bereavement. The length of the pre-bereavement interval (amount of time between pre-bereavement measures and spousal death) was not included in many longitudinal studies. Of the studies that did report the pre-bereavement interval, the length of time was within 1 year before spousal death. The length of the follow-up was also not included in many longitudinal studies, and may explain some of the inconsistencies in the results. Of the studies that did report the follow-up period, the length of the post-bereavement interval ranged from 1.5 – 4.0 years among prospective studies and 1 - 48 months among post-bereavement studies. Additionally, cross-sectional studies rarely reported the length of widowhood at time of assessment, and were often unclear if studies controlled for this variable in the analyses.

Precise information on measurement intervals from death are essential to determining when behavioral change is likely to occur and the time course of each behavioral domain. The extant literature consistently shows that surviving elders commonly experience changes in physical and psychological well-being during the first six months postloss. Widowed elders who are not able to cope with their loss and its consequences for more than six months postloss are often in need of a psychiatric intervention (Stroebe et al., 2007). It is reasonable to expect that behavioral change will similarly occur during the first six months postloss. It is important to note that the length of the follow-up duration should be matched to the time course of the behavioral domain. The time course of one behavioral domain may be very different than the time course of another. For example, bereaved elders may immediately alter their daily routines associated with food preparation and eating but may not notice changes in their weight status for several weeks or months following spousal loss. In addition, widowed elders may contemplate changing their physical and social activities immediately following bereavement, but may not enact these behavioral changes for several months postloss. Research is needed to identify the appropriate time course of behavioral change following bereavement. Failure to include an appropriate measurement interval likely underestimates the effect of bereavement on behavioral change.

Implications for Prevention

There are several ways in which this review could inform prevention and intervention studies during late-life spousal bereavement. First, future studies should evaluate whether there are persistent associations after bereavement between these six identified health behaviors and physical- and mental health outcomes. By focusing on the continuation or maintenance of routine health behaviors, behavioral interventions could be targeted towards bereaved elders to prevent or treat the negative physical health and mental health outcomes associated with bereavement. However, whether it is reasonable to expect that these six health behaviors are amendable to change in this population versus the larger older adult population is unknown. Second, studies should evaluate the additive effects of multiple behavioral changes on bereavement-related health outcomes to determine whether changes in multiple behavioral domains (as opposed to change in one behavioral domain) amplify negative health outcomes. If multiple behavioral changes are associated with increased health problems, clinicians and family members will have a better way to identify elders who are most at-risk for bereavement-related health problems.

Finally, there are many mental health interventions targeted toward the prevention of persistent emotional reactions among spousally bereaved elders (for review see Forte et al., 2004). Preventive health behaviors and negative affect are strongly correlated (Kobau et al., 2004). For example, mental health problems - such as depression - are associated with decreased adherence to self-management behaviors - such as physical activity and diet (DiMatteo et al., 2000). Therefore, developing a behavioral model of prevention in tandem with targeting specific mental health components may potentiate positive behavioral outcomes. Strategies that simultaneously treat depression while concentrating on the maintenance of routine health behaviors may achieve the greatest health outcomes. Older adults may also be more receptive to a mental health intervention if they believe they will learn new self-management strategies that will improve not only their quality of life but functional independence.

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This is the first systematic review of the effects of bereavement on common health behaviors that are well-known correlates of health during late life (USDHHS, 2008). The availability of prospective and post-bereavement longitudinal studies made it possible to assess both the short and long-term effects of bereavement on health behavior change. However, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. First, this review did not include unpublished studies. Null findings are less likely to be published, which may have led to an overrepresentation of studies in the field with positive results. Second, the studies identified were too heterogeneous for a quantitative review. Nevertheless, we believe that systematically describing all characteristics and results of each study will inform the work of both researchers and clinicians alike.

Conclusion

This review showed strong evidence for a relationship between bereavement and nutritional risk, involuntary weight loss, and moderate support for impaired sleep quality and increased alcohol consumption. Due to the lack of uniformity in the measurement of physical activity, there was mixed evidence for a relationship between bereavement and physical activity. Additional research is needed to understand the effect of bereavement on leisure/social activities versus sports/exercise activities, as well as the modifying effect of gender. With the rapid increase in studies consistently demonstrating the health benefits of aerobic exercise, understanding the effect of bereavement on physical exercise should be a high priority. This review also points to the need for further research to determine how bereavement changes the daily routines of widowed elders to fully understand how bereavement impacts behavioral change across multiple domains. For instance, health care utilization is important for maintaining health among elderly populations and deserves attention within the context of bereavement (Jin & Chrisatakis, 2009). Researchers should explore whether and how widowhood influences change in health care practices such as maintaining regular interactions with health care providers and engaging in annual health exams and screenings. Given the profound physical health and mental health effects of late-life bereavement and the number of adults who become widowed each year, prevention trials aimed at maintaining or improving eating behaviors, sleep, alcohol consumption, and weight status should be developed.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grants from NIH P30 MH090333-01A1, MHO19986, NR009573, NR013450, AG026010 , AG032370, and NSF 0540865.

References

- Anderson B. The relationship of stress, sleep, and depression in an elderly cohort: Predictors, mediators, and moderators. (Doctoral dissertation) 1999 Retrieved from ProQuest Information & Learning. (AAI9945089) [Google Scholar]

- Avis NE, Brambilla DJ, Vass K, McKinlay JB. The effect of widowhood on health: A prospective analysis from the Massachusetts women's health study. Social Science Medicine. 1991;33:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CJ, Schneweis KM. An empirical search for stages of widowhood. Journal of Death and Dying. 1980;11:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Brawley LR, Rejeski WJ, King AC. Promoting physical activity for older adults: The challenges for changing behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C. Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1990;43:1327–1335. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90099-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossé R, Ekerdt DJ, Silbert JE. The Veterans Administration Normative Aging Study. In: Mednick SA, Harway M, Finello KM, editors. Handbook of longitudinal research: Volume 2. Teenage and adults cohorts. Praeger; New York: 1984. pp. 273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A. Mortality after bereavement: A review of the literature on survival periods and factors affecting survival. Social Science & Medicine. 24:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): A new instrument for psychiatric research and practice. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne GJA, Raphael B. The psychological symptoms of conjugal bereavement in elderly men over the first 13 months. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;12:241–251. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199702)12:2<241::aid-gps590>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne GJA, Raphael B, Arnold E. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in recently widowed older men. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:740–747. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Neees RM, Wortman C, editors. Spousal Bereavement in Late Life. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS, Lund DA, Rice SJ. Participants’ attendance at a health promotion program for older widows and widowers. American Journal of Health Education. 2001;32:229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JH, Gill TM, Prigerson HG. Health behaviors associated with better quality of life for older bereaved persons. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8:96–106. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. ‘The Earth is Round (p<.05)’. American Psychologist. 1994;49:997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Type of postmenopausal hormone use and risk of breast cancer: 12-year follow-up from the Nurses' Health Study. Cancer Causes and Control. 1992;3:433–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00051356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards WS, Berlin M. National Medical Expenditure Survey Methods 2. Public Health Service; Rockville, MC: 1989. Questionnaires and data collection methods for the Household Survey and the Survey of American Indians and Alaska Natives. National Center for Health Services Research and Health Care Technology Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Eng PM, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice G, Rimm EB. Effects of marital transitions on changes in dietay and other health behaviours in US male health professionals. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health. 2005;59:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick T, Spiro A, Kressin NR, Greene E, Bosse R. Leisure activities, stress, and health among bereaved and non-bereaved elderly men: The Normative Aging Study. Omega. 2001;43:217–245. [Google Scholar]

- Forte AL, Hill M, Pazder R, Feudtner C. Bereavement care interventions: A systematic review. BMC Palliative Care. 2004;3:3–19. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Newman A. The cardiovascular health study: Design and rationale. Annals of Epidemiology. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Buysse DJ, Norzinger EA, Reynolds CF, III, Thompson W, Mazumdar S, Monk TH. Financial strain is a significant correlate of sleep continuity disturbances in late-life. Biological Psychology. 2008;77:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11:213–228. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Lantz PM, Herd P. Continuity and change in the social stratification of aging and health over the life course: Evidence from a nationally representative longitudinal study from 1986 to 2001/2002 (Americans’ Changing Lives Study). Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2005;60:15–26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhar-Nabarro Z, Smoski MJ. A review of theoretical and empirical perspectives on marital satisfaction and bereavement outcomes: Implications for working with older adults. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health. 2012;35:257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Janke MC, Nimrod G, Kleiber DA. Leisure patterns and health among recently widowed adults. Activities, Adaptation & Aging. 2008a;32:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Janke MC, Nimrod G, Kleiber DA. Reduction in leisure activity and well-being during the transition to widowhood. Journal of Women & Aging. 2008b;20:83–98. doi: 10.1300/J074v20n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke MC, Nimrod G, Kleiber DA. Leisure activity and depressive symptoms of widowed and married women in later life. Journal of Leisure Research. 2008c;40:250–266. [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Chrisatakis NA. Investigating the mechanism of marital mortality reduction: The transition to widowhood and quality of health care. Demography. 2009;46:605–625. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]