Abstract

Otto Warburg noted decades ago that cancer cells maintain very high rates of glycolysis, converting glucose to lactate, despite sufficient oxygen to perform oxidative-phosphorylation, which is the more efficient means of generating energy (ATP) from glucose. This conundrum has generated considerable speculation as to whether altered metabolism, including altered glucose metabolism, is a cause or consequence of malignancy and, if the former, what benefits altered metabolism might confer upon cancer cells. Several lines of evidence, including the recent identification of mutations affecting Fumarate Hydratase, Succinate Dehydrogenase, and Isocitrate Dehydrogenase, have strengthened the notion that altered metabolism can cause cancer and a number of non-mutually exclusive models have been put forth to rationalize why cancer cells might benefit from a high rate of glycolysis and decreased oxidative phosphorylation. This chapter will focus on the role of HIF, 2-oxoglutarate, and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes in cancer and cancer metabolism.

The HIF Transcription Factor

When cells are placed in a low oxygen environment they normally undergo a series of metabolic adaptations including an increase in glucose uptake and glycolysis and a decrease in oxidative phosphorylation. Conversely, the presence of oxygen is associated with a decrease in glycolysis and an increase in oxidative phosphorylation. The coupling of oxidative phosphorylation is known as the Pasteur Effect and is mediated by the HIF transcription factor (Seagroves et al. 2001).

HIF is a heterodimer consisting of an unstable alpha subunit and a stable beta subunit (also frequently called ARNT) (Kaelin and Ratcliffe 2008). Under low oxygen conditions the HIF alpha subunit is stabilized, dimerizes with a HIF beta subunit, translocates to the nucleus, and transcriptionaly activates a suite of genes that increase glucose uptake, increase glycolysis, and decrease oxidative phosphorylation. The latter is mediated by an increase in PDK, which phosphorylates, and thereby inactivates, pyruvate dehydrogenase (Kim et al. 2006a; Papandreou et al. 2006). This limits the entry of pyruvate into the Krebs cycle. Instead, pyruvate is converted lactate and extruded from the cell by the HIF responsive gene products lactate dehydrogenase A and monocarboxylate transporter 4, respectively (Ebert and Bunn 1998; Ullah et al. 2006; Perez de Heredia et al. 2010).

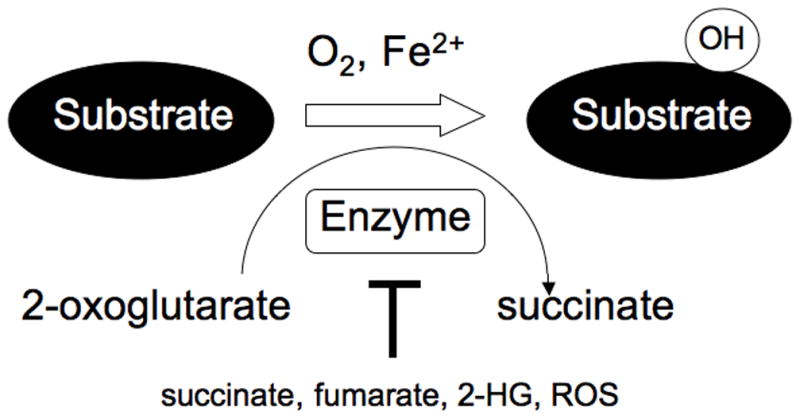

The stability of HIFα is linked to oxygen availability because it is a substrate for the EglN (also called PHD) family of prolyl hydroxylases (Kaelin and Ratcliffe 2008). In the presence of oxygen EglN hydroxylates HIFα on one (or both) of two conserved prolyl residues. Hydroxylation of either site creates a binding site for a ubiquitin ligase that contains the pVHL tumor suppressor protein. This complex then polyubiquitinates HIFα, thereby targeting it for destruction by the proteasome. There are 3 EglN family members. EglN1 appears to be the primary HIF prolyl hydroxylase with EglN2 and EglN3 playing compensatory roles under certain conditions (Berra et al. 2003; Appelhoff et al. 2004; Marxsen et al. 2004; Stiehl et al. 2006; Minamishima et al. 2009). The oxygen Km values for the hydroxylation of HIFα by EglN family members are just slightly above those likely to be encountered in tissues under normal conditions (Hirsila et al. 2003). Accordingly, the EglN family members are sensitive to further decrements in oxygen availability (hypoxia), leading to reduced hydroxylation of HIFα and therefore higher steady state levels of HIFα. In addition to oxygen, EglN family members also require reduced iron and 2-oxoglutarate (also called alpha-ketoglutarate) and there activity can be influenced by reactive oxygen species and changes in specific Kreb’s cycle intermediates (Fig 1) (see also below) (Kaelin 2005; Kaelin and Ratcliffe 2008).

Fig 1. 2-Oxoglutarate-dependent Dioxygenase Reaction.

2-Oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes require 2-oxoglutarate (also called alpha ketoglutarate), oxygen, and reduced iron to hydroxylate their substrates. 2-oxoglutarate is decarboxylated to succinate during the reaction. In the cases of histone demethylases a methyl group is hydroxylated and the resulting hydroxymethyl group is spontaneously given off as formaldehyde. These enzymes are variably susceptible to inhibition by Krebs Cycle intermediates such a succinate and fumarate, to 2-hydroxyglutarate, and to reactive oxygen species.

The Warburg Effect

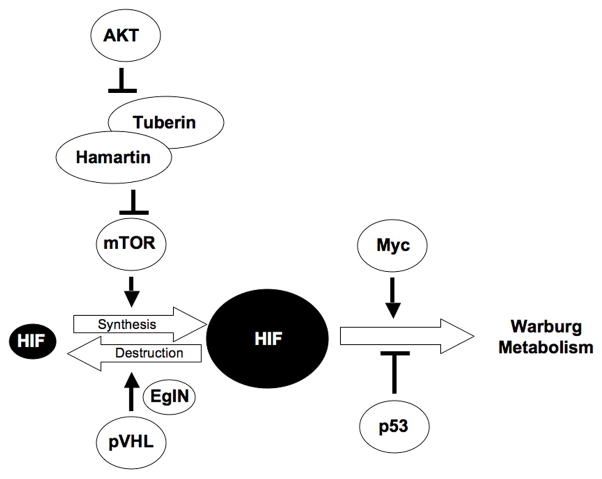

The Warburg Effect is due, at least in part, to the failure of cancer cells to appropriately downregulate HIF under well oxygenated conditions, either because of mutations that increase HIF production or that decrease HIF destruction (Fig 1). With respect to increased HIFα production, mutations that directly or indirectly inactivate the TSC complex, such as activating mutations of PI3K or AKT, lead to increased TORC1 activity (Brugarolas and Kaelin 2004). Increased TORC1, in turn, promotes HIFα transcription and translation (Hudson et al. 2002; Arsham et al. 2003; Brugarolas et al. 2003)(Fig 2). With respect to decreased HIFα destruction, inactivating mutations of the VHL tumor suppressor gene lead to impaired HIFα proteasomal degradation for the reasons outlined above (Fig 2). Similarly, inactivating SDH and FH mutations lead to the accumulation of succinate and fumarate, respectively, which inhibit EglN activity by competing with 2-oxoglutarate, thereby allowing HIFα to escape recognition by pVHL (Fig 1) (Dahia et al. 2005; Pollard et al. 2005; Selak et al. 2005; Selak et al. 2006; Koivunen et al. 2007; Pollard et al. 2007; Kaelin 2009; Sudarshan et al. 2009). A recent study suggested that IDH mutations lower 2-oxoglutarate production and hence EglN activity, leading to HIFα stabilization, although this finding has been disputed (Zhao et al. 2009). More recent studies indicate that cancer-relevant IDH mutations acquire the neomorphic ability to produce the 2-hydroxyglutarate but 2-HG does not appear to inhibit EglN activity (Dang et al. 2009b; Chowdhury et al. 2011).

Fig 2. Central Role of HIF in Warburg Metabolism.

Many oncogenic mutations lead to increased HIF accumulation, which promotes the Warburg Effect. Increase Myc expression and loss of p53 function can also contribute to such metabolic changes.

Although HIF contributes to the Warburg effect it does not act alone. For example, many of the effects of HIF on cell metabolism are reinforced by other molecular perturbations in cancer cells including those leading to activation of c-Myc or loss of p53 (Matoba et al. 2006; Yeung et al. 2008; Feng and Levine 2010; Kaelin and Thompson 2010). Indeed, HIF and c-Myc share a number of common targets that promote glycolysis (Dang 2007; Dang et al. 2009a). Cancer cells also frequently express the M2 isoform of PFK rather than the M1 isoform found in most somatic tissues (Christofk et al. 2008). Expression of the M2 isoform appears to faciliate the diversion of glucose-derived carbons for anabolism (Christofk et al. 2008). c-Myc promotes glutaminolysis, which provides an alternative source of carbon precursors for anabolism as well as for NADPH production in the Kreb’s Cycle (anaplerosis) (Dang et al. 2009a; Dang 2010).

The metabolic changes characteristic of the Warburg Effect are believed to allow cancer cells to out compete their neighbors for nutrients and to use those nutrients for anabolic reactions necessary for growth in addition to energy production. Lactate produced by tumors might also alter the microenvironment in a manner that facilitates both growth and invasion. In addition, changes in mitochondrial ROS production and mitochondrial metabolites (including 2-oxoglutarate) might indirectly affect the behavior of multiple enzymes within the cell, including phosphatases and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes, that control cell growth and survival.

HIF and Cancer: Bystander or Culprit?

Intratumoral hypoxia, and hence increased HIF levels, are very consistently associated with poor patient outcomes (Semenza 2003). At one extreme, this would reflect the ability of HIF itself to promote tumor growth. On the other hand, it is possible that the correlation simply reflects the fact that the most aggressive tumors are the ones most likely to outgrow their blood supplies and hence to develop intratumoral hypoxia. In favor of the former model, HIF activates a number of genes that might, in theory, promote tumor cell growth, invasion, and metastasis. For example, HIF induces autocrine and paracrine cancer cell growth factors such as TGFα and PDGF B, promotes invasion by upregulating genes such as MMP and LOX, and angiogenesis by upregulating genes such as VEGF (Semenza 2003). It is therefore understandable that HIF is usually viewed as an oncoprotein. Moreover, deletion of HIFα (or ARNT) has been shown to decrease tumor growth in nude mouse subcutaneous xenograft assays (Maxwell et al. 1997; Ryan et al. 1998). On the other hand, there is evidence that HIFα can act as a tumor suppressor, at least in some preclinical models. For example, deletion of HIF1α promotes the growth of teratocarcinomas formed by ES cells and orthotopic tumors form by transformed astrocytes (Carmeliet et al. 1998; Blouw et al. 2003; Covello et al. 2005). Deletion of HIF2α has been shown to promote the growth of K-Ras-driven lung adenocarcinomas in genetically engineered mice and the growth of astrocytomas (Mazumdar et al. 2010).

A causal role for HIFα (particularly HIF2α) has been perhaps most convincingly demonstrated in pVHL-defective kidney cancers. These tumors produce high levels of both HIF1α and HIF2α or, importantly, HIF2α only (Maxwell et al. 1999; Gordan et al. 2008; Shen et al. In Press). In preclinical models, including orthotopic models, elimination of HIF2α is sufficient to inhibit pVHL-defective tumor growth (Kondo et al. 2003; Zimmer et al. 2004) while restoring HIF2α (but not HIF1α) production is sufficient to override tumor suppression by pVHL (Kondo et al. 2002; Maranchie et al. 2002; Raval et al. 2005). In genetically engineered mice HIF2α appears to be necessary and sufficient for much of the pathology observed in tissues that lack pVHL (Kim et al. 2006b; Rankin et al. 2007; Rankin et al. 2008; Rankin et al. 2009). In patients with germline VHL mutations the degree to which their VHL alleles are compromised with respect to HIF regulation tracks closely with their risk of kidney cancer (Li et al. 2007) and single nucleotide polymorphisms in the general population have been linked to the risk of kidney cancer (Purdue et al. 2011). Collectively, these results suggest that HIF2α is a kidney cancer oncoprotein.

In start contrast, HIF1α appears to behave as a kidney cancer tumor suppressor. Three signature chromosomal abnormalities in kidney cancer are loss of chromosome 3p, spanning the VHL gene, loss of chromosome 14q, and gain of chromosome 5q. Chromosome 14q loss is most common in kidney cancer relative to other tumor types and almost invariably leads to loss of HIF1α located at 14q22 (Shen et al. In Press). Many pVHL-defective renal carcinoma lines harbor focal, homozygous, HIF1α deletions that lead to the production of either no HIF1α protein or the production of HIF1α variants that reflect alternative splicing events that circumvent the missing exons (Shen et al. In Press). Restoration of wild-type HIF1α in such cells suppresses their ability to proliferate in vitro and in vivo (Raval et al. 2005; Shen et al. In Press). Conversely, elimination of wild-type HIF1α in HIF1α-proficient cells enhances their proliferation in vitro and in vivo (Gordan et al. 2008; Shen et al. In Press). Intragenic HIF1α mutations have been identified in kidney cancer genome sequencing projects and, when tested, have proven to be loss of function (Morris et al. 2009; Dalgliesh et al. 2010; Shen et al. In Press). Such mutations are, however, rare compared to the frequency of 14q loss in kidney cancer. Specifically, many 14q deleted kidney cancers retain a wild-type HIF1α allele (Shen et al. In Press). This suggests that HIF1α haploinsufficiency contributes to kidney cancer growth. In keeping with this idea, 14q deleted tumors have a transcriptional signature indicative of HIF1α loss (Shen et al. In Press).

EglN Prolyl Hydroxylases as Targets of SDH, FH, and IDH Mutations

Deregulation of HIF is also suspected of playing a pathogenic role in papillary renal carcinomas linked to fumarate hydratase deficiency and to paragangliomas linked to succinate dehydrogenase deficiency (Gimenez-Roqueplo et al. 2001; Isaacs et al. 2005; Pollard et al. 2005; Selak et al. 2005; Selak et al. 2006; MacKenzie et al. 2007; Pollard et al. 2007; Sudarshan et al. 2009; Sudarshan et al. 2011), although the paucity of relevant cell culture and mouse models has so far prevented the types of preclinical validation experiments described above for pVHL-defective clear cell renal carcinomas to determine whether truly plays a causal, as opposed to correlative, role in these settings. It has also been suggested that SDH mutations lead to paraganglioma in an EglN-dependent, but HIF-independent, manner based on the following observations. A number of different genes, including VHL, NF1, c-Ret, and SDH subunit genes, lead to an increased risk of extraadrenal and intradrenal paragangliomas (the latter are called pheochromocytomas) but only when mutated in the germline (Nakamura and Kaelin 2006; Kaelin 2007). This suggests that these genes control of a paraganglioma-relevant biologic process that takes place during embryological development. Notably, some germline VHL mutations lead to a high risk of paraganglioma but not kidney cancer or the blood vessel tumors (hemangioblastomas) observed in classical VHL disease (Kaelin 2002). When tested, the product of such mutant VHL alleles are essentially normal with respect to HIF regulation (Clifford et al. 2001; Hoffman et al. 2001). Conversely, VHL mutations that confer a high risk of kidney cancer and low risk of paraganglioma lead to significant deregulation of HIF (Maxwell et al. 1999; Clifford et al. 2001; Hoffman et al. 2001; Li et al. 2007). The simplest interpretation of these findings is that the development of paraganglioma in cells lacking wild-type pVHL reflects the loss of a HIF-independent pVHL function.

Paragangliomas are tumors of the sympathetic nervous system. During embryological development, primitive neuronal cells with the potential to become sympathetic neurons compete for growth factors such as NGF, with the losers undergoing apoptosis (Deckwerth and Johnson 1993; Deppmann et al. 2008). NGF withdrawal leads to the induction of EglN3, which appears to be necessary and sufficient for apoptosis in this setting (Lipscomb et al. 1999; Straub et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2005). Loss of neurofibromin, which is a Ras-GAP for the nerve growth factor receptor, or gain of c-Ret, which can activate the nerve growth factor receptor in cis, lead to decreased apoptosis after NGF withdrawal (Vogel et al. 1995; Dechant 2002; Lee et al. 2005). Paraganglioma-associated VHL mutations lead to activation of aPKC and Jun B, which represses EglN3 levels (Lee et al. 2005). Finally, SDH mutations lead to the accumuation of succinate, which inhibits EglN3-induced apoptosis (Lee et al. 2005). Hence, all of the genes linked to familial paraganglioma can potentially regulate apoptosis of sympathetic neuronal precursors during embryological development, suggesting that paragangliomas arise in this setting due to impaired culling of this cell population. The sympathetic nervous system abnormalities observed in EglN3−/− mice are consistent with this view (Bishop et al. 2008).

EglN3-induced apoptosis appears to be HIF-independent (Schlisio et al. 2008). Interestingly, induction of apoptosis appears, instead, to be linked to its ability to increase expression of KIF1Bβ, which encodes a kinesin family member (Munirajan et al. 2008; Schlisio et al. 2008). KIF1Bβ maps to the minimal region of 1p36 that is deleted in a number of neural crest-derived tumors, including the sympathetic nervous system tumor neuroblastoma. Loss of function KIF1Bβ mutations have been identified in a family with neural crest tumors and in a small subset of pheochromocytomas, medulloblastomas, and neuroblastomas (Schlisio et al. 2008; Yeh et al. 2008). The frequency of such mutations is low, however, relative to the frequency of 1p36 deletions in such tumors. Among several possibilities, this might indicate that haploinsufficiency for KIF1Bβ, perhaps together with loss of contiguous genes, is sufficient to promote neural crest tumor development and that complete loss of KIF1Bβ would not.

Non-EglN Targets of SDH, FH, and IDH Mutations

It is also possible that the accumulation of succinate and fumarate observed in SDH and FH mutant tumors, as well as the accumulation of R-2-hydroxyglutarate in IDH mutant tumors, transforms cells by affecting the behavior of other 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes in addition to (or in some cases, perhaps instead of) the EglN family members (Fig 1). For example, the jumonji C domain-containing histone demethylases are 2 oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes (Klose et al. 2006). It is possible that inhibition of one or more of these enzymes, through changes in chromatin structure and gene expression, leads to transformation. In biochemical assays 2-HG can, with variable potencies inhibit various histone demethylases (Chowdhury et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2011). The histone demethylase Jhd1, an H3K36 demethylase, is inhibited in a yeast model of SDH deficiency (Smith et al. 2007) as is the H3K27 demethylase KDM6B (JMJD3) in mammalians cells after knockdown of SDH with siRNA (Cervera et al. 2009). KDM6B and its paralog KDM6A (UTX) are attractive candidates as targets of succinate, fumarate, and 2-HG because they behave as tumor suppressors in cell culture models by virtue of their ability to increase the expression of the Ink4A/ARF locus in response to oncogenic stress and to cooperate with the pRB tumor suppressor (Agger et al. 2009; Barradas et al. 2009; Herz et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010). Moreover, UTX is mutationally inactivated in a variety of tumors (van Haaften et al. 2009; Dalgliesh et al. 2010).

More recently TET2 has been implicated as a target of 2-HG (Figueroa et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2011). TET2 belongs to a family of 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes that hydroxylate methylcytosine, which is suspected of playing a role in the turnover of methylated DNA (Noushmehr et al. 2010; Ficz et al. 2011). Inactivating TET2 mutations, like IDH mutations, have been observed in acute leukemia and are mutually exclusive, consistent with the notion that IDH mutations lead to TET2 inactivation (and thereby eliminate the selection pressure to mutate TET2) (Figueroa et al. 2010). Overexpression of mutant IDH decreases the enzymatic of coexpressed TET2 and impairs hematopoietic differentiation (Figueroa et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2011). DNA hypermethylation is also a feature of IDH mutant brain tumors and leukemia, consistent with the idea that IDH mutations impair TET2 activity and thereby impair DNA demethylation (Figueroa et al. 2010; Noushmehr et al. 2010).

2-Oxoglutarate-dependent Dioxygenases as Cancer Therapeutic Targets

As described above, inactivation of specific 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases is suspected of contributing to transformation, especially in the context of SDH, FH, and IDH mutations. It is also possible that HIF, by limiting entry of pyruvate into the Krebs Cycle, indirectly inhibits such enzymes through changes in Krebs Cycle intermediates although this remains to be proven. At the same time, it is also clear that certain 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes can promote, rather than inhibit, cancer cells, at least in certain contexts. In addition, HIF increases the transcription of certain 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes (see below), perhaps to compensate for their reduced activity under hypoxia.

It is important to note that different 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes can differ substantially with respect to their requirements for oxygen and 2-oxoglutarate (Km values) and sensitivity to inhibition by metabolites such as succinate and 2-HG (IC50 values). As a result, genetic or pharmacological perturbations that affect intracellular oxygen and metabolite levels might affect (indirectly) some enzymes in this family more than others. It has also become clear that members of this family can be directly inhibited with drug-like small molecules that bind to their catalytic sites and interfere with 2-oxoglutarate binding, iron binding, or both (Ivan et al. 2002; Mole et al. 2003; Schlemminger et al. 2003; Safran et al. 2006). Moreover, a number of preclinical studies, describe below, support that inhibition of specific 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases would have an antitumor effect.

EglN1

EglN1 suppresses HIF and would therefore be predicted to be cell-autonomous tumor suppressor in most (but not all) cellular contexts for the reasons outlined above. Interestingly, however, tumor cell invasion, intravasation, and metastasis is impaired in Egln1+/− mice, possibly due to vessel pseudonormalization and improved intratumoral oxygenation (Mazzone et al. 2009).

EglN2

EglN2, a member of the EglN family, is induced by estrogen in estrogen receptor positive breast cancers (Seth et al. 2002; Appelhoff et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2009). Estrogen is an important mitogen for breast cancer cells, simulating progression through the cell-cycle. Cyclin D1 promotes cell-cycle progression by directing (together with cdk4 or cdk6) the phosphorylation of the pRB tumor suppressor protein (Sellers and Kaelin 1997). Overexpression, and at times amplification, of Cyclin D1 is common in breast cancer (Steeg and Zhou 1998; Roy and Thompson 2006). Notably, certain Cyclin D1-dependent phenotypes are lost in flies that lack Egl9, the sole EglN family member in this organism (Frei and Edgar 2004). Collectively, these observations pointed to a possible connection between EglN2 and Cyclin D1.

Indeed, loss of EglN2, but not loss of EglN1 or EglN3, decreases Cyclin D1 level in vitro and in vivo. Egln2−/− mice are viable but do not breastfeed appropriately due to mammary gland hypoproliferation reminiscent of mammary glands that lack Cyclin D1 (Zhang et al. 2009). Inactivation of EglN2 suppresses breast cancer proliferation in vitro and in vivo due specifically to loss of Cyclin D1 and impaired pRB phosphorylation (Zhang et al. 2009). Loss of EglN2 also impairs the fitness of a variety of other cancers in addition to breast cancer (Zhang et al. 2009). Control of Cyclin D1 by EglN2 requires EglN2 catalytic activity but appears to be HIF independent (Zhang et al. 2009). EglN2 does not hydroxylate Cyclin D1 directly (at least under the conditions tested so far) and appears to influence Cyclin D1 transcriptionally and postranscriptionally (Zhang et al. 2009).

LOX

HIF induces the expression of LOX, which encodes a lysyl oxidase. LOX expression by primary tumors appears to play a role in mobilization of bone marrow-derived cells that promote the formation of metastatic niches and hence metastasis (Erler et al. 2006; Erler et al. 2009). LOX has also been implicated in the ability of cancer cells to undergo an epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which is often associated with increased invasiveness and drug resistance (Schietke et al. 2010). It remains to be determined, however, whether inhibition of LOX would cause the regression of established tumors or otherwise favorably alter their natural history.

KDM 2A and KDM2B

KDM2A (JHDM1A or FBX11) and KDM2B (JHDM1B or FBXL10) demethylase H3K36. Loss of KDM2B impairs proliferation and induces senescence, at least partly through an increase in p15/Ink4b or p16/Ink4a expression (He et al. 2008; Tzatsos et al. 2009). Similarly, depletion of KDM2B in hematopoietic progenitors significantly impairs HOXA9/MEIS1-induced leukemic transformation, at least partly through impaired self-renewal (He et al. 2011). Conversely, KDM2B is target of a recurrent integration event in a MoMuLV rat lymphoma model and is overexpressed in a subset of leukemia (Pfau et al. 2008; He et al. 2011). Overexpression of KDM2A and/or B can immortalize mouse embryo fibroblasts and transform hematopoietic progenitors (Pfau et al. 2008; He et al. 2011). Collectively, these observations credential KDM2A and KDM2B as potential oncogenes.

KDM3A

KDM3A (JMJD1A, JHDM2A) is a H3K9 demethylase that has been implicated in stem cell maintenance (Ko et al. 2006; Loh et al. 2007). KDM3A is overexpressed in renal carcinoma, presumably because it is the product of a HIF-responsive gene (Beyer et al. 2008; Pollard et al. 2008; Wellmann et al. 2008; Sar et al. 2009; Xia et al. 2009; Krieg et al. 2010). Downeregulation of KDM3A impairs cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness (Krieg et al. 2010; Yamada et al. 2011).

KDM4B and KDM4C

KDM4C (JMJD2C, JHDM3, or GASC1) maps to chromosome 9p23-24, which is amplified in esophageal and breast cancers, and demethylates H3K9 (Yang et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2001; Cloos et al. 2006). In keeping with its suspect role as an oncogene, shRNA-mediated knockdown of KDM4C inhibits cancer cell proliferation in vitro. Conversely, KDM4C induces transformed phenotypes, including growth factor-independent proliferation, anchorage-independent growth, and mammosphere forming ability, when overexpressed in immortalized, nontransformed mammary epithelial cells (Liu et al. 2009). KDM4C was also recently shown to be coamplified with JAK2 in a subset of lymphomas (Rui et al. 2010). KDM4C cooperates with JAK2 in this setting to regulate chromatin structure and promote lymphomagenesis (Rui et al. 2010). KDM4C might also play a role in androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer (Wissmann et al. 2007) whereas its parolog KDM4B (JMJD2B) has been implicated in estrogen receptor signaling and the control of breast cancer proliferation (Yang et al. 2010; Kawazu et al. 2011; Shi et al. 2011). Both KDM4B and KDM4C can be induced by hypoxia (Beyer et al. 2008) (Xia et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2010).

KDM5A and KDM5B

KDM5A (also called RBP2 or JARID1A) and KDM5B (also called PLU-1 or JARID1B) are JmjC-containing histone demethylases that recognize methylated H3K4, a mark that is usually associated with transcriptionally active chromatin (Christensen et al. 2007; Hayakawa et al. 2007; Iwase et al. 2007; Klose et al. 2007; Secombe et al. 2007; Yamane et al. 2007). Methylated H3K4 is also found in association with the repressive mark methylated H3K27 in so-called bivalent chromatin domains, which believed to play important role in stem cell fate determination (Bernstein et al. 2006; Gan et al. 2007; Ohm et al. 2007). Increased expression PLU-1 and RBP2 have been linked to an increase in stem-like properties in cancer cells and to drug resistance (Dey et al. 2008; Roesch et al. 2010).

RBP2 was originally identified as a pRB-binding protein and has been linked to control of sensecence and differentiation by pRB (Defeo-Jones et al. 1991; Fattaey et al. 1993; Benevolenskaya et al. 2005). Inactivation of RBP2 impairs the growth of pRB-defective human cancer lines in vitro and in vivo and the development of tumors in Rb1+/− mice (Benevolenskaya et al. 2005; Lin et al. In Press). Similarly loss of RBP2 impairs the development of tumors driven by loss of the MEN1 tumor suppressor, which is a component of an H3K4 methylase complex (Lin et al. In Press). This later observation suggests that tumors driven by loss of a particular histone methylase might be treated by inhibiting one or more demethylases that normally serve to antagonize its function (or vice versa). This is noteworthy given the frequency with which mutations affecting histone methylases and demethylases are being identified in cancer (Northcott et al. 2009; Dalgliesh et al. 2010; Chapman et al. 2011; Yoshimi and Kurokawa 2011).

PLU-1 is frequently overexpressed in breast cancer and downregulation of PLU-1 impairs breast cancer growth in vivo (Barrett et al. 2002; Catchpole et al. 2011). Similarly, PLU-1 is overexpressed in bladder and lung cancer where its inhibition leads to apoptosis (Hayami et al. 2010). The overexpression of PLU-1 in tumors might be due, at least partly, to its induction by hypoxia (Xia et al. 2009).

Summary

There are now multiple examples of mutations affecting metabolic enzymes that play a causal role in cancer. Derangements in cellular metabolism can affect oncogenic signaling pathways and vice versa. The HIF transcription factor plays an important role in reprogramming cancer cell metabolism as well as being responsive to changes in cellular metabolism. Recent genetic and biochemical studies related to cancer metabolism point to a potentially important role for 2-oxoglutarate, and hence 2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzymes, in transformation. Pharmacological manipulation of these enzymes might be useful for the treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgments

I thank Christine McMahon for careful reading of the manuscript and for fellow laboratory members and colleagues for useful discussions. Supported by NIH, HHMI, and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. I apologize to colleagues whose work was not cited due to space limitations or my ignorance. Please bring errors and eggregious omissions to my attention.

References

- Agger K, Cloos PA, Rudkjaer L, Williams K, Andersen G, Christensen J, Helin K. The H3K27me3 demethylase JMJD3 contributes to the activation of the INK4A-ARF locus in response to oncogene- and stress-induced senescence. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1171–1176. doi: 10.1101/gad.510809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhoff RJ, Tian YM, Raval RR, Turley H, Harris AL, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Gleadle JM. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38458–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsham AM, Howell JJ, Simon MC. A novel hypoxia-inducible factor-independent hypoxic response regulating mammalian target of rapamycin and its targets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29655–29660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barradas M, Anderton E, Acosta JC, Li S, Banito A, Rodriguez-Niedenfuhr M, Maertens G, Banck M, Zhou MM, Walsh MJ, et al. Histone demethylase JMJD3 contributes to epigenetic control of INK4a/ARF by oncogenic RAS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1177–1182. doi: 10.1101/gad.511109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A, Madsen B, Copier J, Lu PJ, Cooper L, Scibetta AG, Burchell J, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. PLU-1 nuclear protein, which is upregulated in breast cancer, shows restricted expression in normal human adult tissues: a new cancer/testis antigen? Int J Cancer. 2002;101:581–588. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benevolenskaya EV, Murray HL, Branton P, Young RA, Kaelin WG., Jr Binding of pRB to the PHD Protein RBP2 Promotes Cellular Differentiation. Mol Cell. 2005;18:623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berra E, Benizri E, Ginouves A, Volmat V, Roux D, Pouyssegur J. HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. Embo J. 2003;22:4082–4090. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer S, Kristensen MM, Jensen KS, Johansen JV, Staller P. The histone demethylases JMJD1A and JMJD2B are transcriptional targets of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36542–36552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804578200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop T, Gallagher D, Pascual A, Lygate CA, de Bono JP, Nicholls LG, Ortega-Saenz P, Oster H, Wijeyekoon B, Sutherland AI, et al. Abnormal sympathoadrenal development and systemic hypotension in PHD3−/− mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3386–3400. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02041-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouw B, Song H, Tihan T, Bosze J, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, Johnson RS, Bergers G. The hypoxic response of tumors is dependent on their microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas J, Kaelin WG., Jr Dysregulation of HIF and VEGF is a unifying feature of the familial hamartoma syndromes. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas JB, Vazquez F, Reddy A, Sellers WR, Kaelin WG., Jr TSC2 regulates VEGF through mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, Neeman M, Bono F, Abramovitch R, Maxwell P, et al. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394:485–490. doi: 10.1038/28867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catchpole S, Spencer-Dene B, Hall D, Santangelo S, Rosewell I, Guenatri M, Beatson R, Scibetta AG, Burchell JM, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. PLU-1/JARID1B/KDM5B is required for embryonic survival and contributes to cell proliferation in the mammary gland and in ER+ breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:1267–1277. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera AM, Bayley JP, Devilee P, McCreath KJ. Inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase dysregulates histone modification in mammalian cells. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:89. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Schinzel AC, Harview CL, Brunet JP, Ahmann GJ, Adli M, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–472. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury R, Yeoh KK, Tian YM, Hillringhaus L, Bagg EA, Rose NR, Leung IK, Li XS, Woon EC, Yang M, et al. The oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate inhibits histone lysine demethylases. EMBO Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J, Agger K, Cloos PA, Pasini D, Rose S, Sennels L, Rappsilber J, Hansen KH, Salcini AE, Helin K. RBP2 belongs to a family of demethylases, specific for tri-and dimethylated lysine 4 on histone 3. Cell. 2007;128:1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford S, Cockman M, Smallwood A, Mole D, Woodward E, Maxwell P, Ratcliffe P, Maher E. Contrasting effects on HIF-1alpha regulation by disease-causing pVHL mutations correlate with patterns of tumourigenesis in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1029–1038. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloos PA, Christensen J, Agger K, Maiolica A, Rappsilber J, Antal T, Hansen KH, Helin K. The putative oncogene GASC1 demethylates tri- and dimethylated lysine 9 on histone H3. Nature. 2006;442:307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature04837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covello KL, Simon MC, Keith B. Targeted replacement of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by a hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha knock-in allele promotes tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2277–2286. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahia PL, Ross KN, Wright ME, Hayashida CY, Santagata S, Barontini M, Kung AL, Sanso G, Powers JF, Tischler AS, et al. A HIF1alpha regulatory loop links hypoxia and mitochondrial signals in pheochromocytomas. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:72–80. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, Davies H, Edkins S, Hardy C, Latimer C, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV. The interplay between MYC and HIF in the Warburg effect. Ernst Schering Found Symp Proc. 2007:35–53. doi: 10.1007/2789_2008_088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV. Rethinking the Warburg effect with Myc micromanaging glutamine metabolism. Cancer Res. 2010;70:859–862. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV, Le A, Gao P. MYC-induced cancer cell energy metabolism and therapeutic opportunities. Clin Cancer Res. 2009a;15:6479–6483. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, Fantin VR, Jang HG, Jin S, Keenan MC, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009b;462:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechant G. Chat in the trophic web: NGF activates Ret by inter-RTK signaling. Neuron. 2002;33:156–158. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckwerth TL, Johnson EM., Jr Temporal analysis of events associated with programmed cell death (apoptosis) of sympathetic neurons deprived of nerve growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1207–1222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defeo-Jones D, Huang PS, Jones RE, Haskell KM, Vuuocolo GA, Hanobik MG, Huber HE, Oliff A. Cloning of cDNAs for cellular proteins that bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature. 1991;352:251–254. doi: 10.1038/352251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deppmann CD, Mihalas S, Sharma N, Lonze BE, Niebur E, Ginty DD. A model for neuronal competition during development. Science. 2008;320:369–373. doi: 10.1126/science.1152677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey BK, Stalker L, Schnerch A, Bhatia M, Taylor-Papidimitriou J, Wynder C. The histone demethylase KDM5b/JARID1b plays a role in cell fate decisions by blocking terminal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5312–5327. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00128-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert BL, Bunn HF. Regulation of transcription by hypoxia requires a multiprotein complex that includes hypoxia-inducible factor 1, an adjacent transcription factor, and p300/CREB binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4089–4096. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, Lang G, Bird D, Koong A, Le QT, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, Dornhofer N, Kong C, Le QT, Chi JT, Jeffrey SS, Giaccia AJ. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nature04695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattaey A, Helin K, Dembski M, Dyson N, Harlow E, Vuocolo G, Hanobik M, Haskell K, Oliff A, Defeo-Jones D, et al. Characterization of the retinoblastoma binding proteins RBP1 and RBP2. Oncogene. 1993;8:3149–3156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Levine AJ. The regulation of energy metabolism and the IGF-1/mTOR pathways by the p53 protein. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficz G, Branco MR, Seisenberger S, Santos F, Krueger F, Hore TA, Marques CJ, Andrews S, Reik W. Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nature. 2011;473:398–402. doi: 10.1038/nature10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, Li Y, Bhagwat N, Vasanthakumar A, Fernandez HF, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei C, Edgar BA. Drosophila cyclin D/Cdk4 requires Hif-1 prolyl hydroxylase to drive cell growth. Dev Cell. 2004;6:241–251. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Q, Yoshida T, McDonald OG, Owens GK. Concise review: epigenetic mechanisms contribute to pluripotency and cell lineage determination of embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Favier J, Rustin P, Mourad JJ, Plouin PF, Corvol P, Rotig A, Jeunemaitre X. The R22X mutation of the SDHD gene in hereditary paraganglioma abolishes the enzymatic activity of complex II in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and activates the hypoxia pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1186–1197. doi: 10.1086/324413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan JD, Lal P, Dondeti VR, Letrero R, Parekh KN, Oquendo CE, Greenberg RA, Flaherty KT, Rathmell WK, Keith B, et al. HIF-alpha effects on c-Myc distinguish two subtypes of sporadic VHL-deficient clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T, Ohtani Y, Hayakawa N, Shinmyozu K, Saito M, Ishikawa F, Nakayama J. RBP2 is an MRG15 complex component and down-regulates intragenic histone H3 lysine 4 methylation. Genes Cells. 2007;12:811–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayami S, Yoshimatsu M, Veerakumarasivam A, Unoki M, Iwai Y, Tsunoda T, Field HI, Kelly JD, Neal DE, Yamaue H, et al. Overexpression of the JmjC histone demethylase KDM5B in human carcinogenesis: involvement in the proliferation of cancer cells through the E2F/RB pathway. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Kallin EM, Tsukada Y, Zhang Y. The H3K36 demethylase Jhdm1b/Kdm2b regulates cell proliferation and senescence through p15(Ink4b) Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1169–1175. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Nguyen AT, Zhang Y. KDM2b/JHDM1b, an H3K36me2-specific demethylase, is required for initiation and maintenance of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:3869–3880. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz HM, Madden LD, Chen Z, Bolduc C, Buff E, Gupta R, Davuluri R, Shilatifard A, Hariharan IK, Bergmann A. The H3K27me3 demethylase dUTX is a suppressor of Notch- and Rb-dependent tumors in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2485–2497. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01633-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsila M, Koivunen P, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. Characterization of the human prolyl 4-hydroxylases that modify the hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30772–30780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M, Ohh M, Yang H, Klco J, Ivan M, Kaelin WJ. von Hippel-Lindau protein mutants linked to type 2C VHL disease preserve the ability to downregulate HIF. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1019–1027. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson CC, Liu M, Chiang GG, Otterness DM, Loomis DC, Kaper F, Giaccia AJ, Abraham RT. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7004–7014. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7004-7014.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Mole DR, Lee S, Torres-Cabala C, Chung YL, Merino M, Trepel J, Zbar B, Toro J, et al. HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan M, Haberberger T, Gervasi DC, Michelson KS, Gunzler V, Kondo K, Yang H, Sorokina I, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, et al. Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13459–13464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192342099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase S, Lan F, Bayliss P, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Huarte M, Qi HH, Whetstine JR, Bonni A, Roberts TM, Shi Y. The X-linked mental retardation gene SMCX/JARID1C defines a family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. Cell. 2007;128:1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG. Molecular basis of the VHL hereditary cancer syndrome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:673–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG., Jr ROS: really involved in oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 2005;1:357–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG., Jr The von hippel-lindau tumor suppressor protein: an update. Methods Enzymol. 2007;435:371–383. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)35019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG., Jr SDH5 mutations and familial paraganglioma: somewhere Warburg is smiling. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr, Thompson CB. Q&A: Cancer: clues from cell metabolism. Nature. 2010;465:562–564. doi: 10.1038/465562a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawazu M, Saso K, Tong KI, McQuire T, Goto K, Son DO, Wakeham A, Miyagishi M, Mak TW, Okada H. Histone demethylase JMJD2B functions as a co-factor of estrogen receptor in breast cancer proliferation and mammary gland development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006a;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Safran M, Buckley MR, Ebert BL, Glickman J, Bosenberg M, Regan M, Kaelin WG., Jr Failure to prolyl hydroxylate hypoxia-inducible factor alpha phenocopies VHL inactivation in vivo. Embo J. 2006b;25:4650–4662. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC-domain-containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nrg1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose RJ, Yan Q, Tothova Z, Yamane K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Gilliland DG, Zhang Y, Kaelin WG., Jr The retinoblastoma binding protein RBP2 is an H3K4 demethylase. Cell. 2007;128:889–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko SY, Kang HY, Lee HS, Han SY, Hong SH. Identification of Jmjd1a as a STAT3 downstream gene in mES cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2006;31:53–62. doi: 10.1247/csf.31.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivunen P, Hirsila M, Remes AM, Hassinen IE, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) hydroxylases by citric acid cycle intermediates: possible links between cell metabolism and stabilization of HIF. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4524–4532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr Inhibition of HIF2alpha Is Sufficient to Suppress pVHL-Defective Tumor Growth. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:439–444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Klco J, Nakamura E, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG. Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg AJ, Rankin EB, Chan D, Razorenova O, Fernandez S, Giaccia AJ. Regulation of the histone demethylase JMJD1A by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha enhances hypoxic gene expression and tumor growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:344–353. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00444-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Nakamura E, Yang H, Wei W, Linggi MS, Sajan MP, Farese RV, Freeman RS, Carter BD, Kaelin WG, Jr, et al. Neuronal apoptosis linked to EglN3 prolyl hydroxylase and familial pheochromocytoma genes: Developmental culling and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhang L, Zhang X, Yan Q, Minamishima YA, Olumi AF, Mao M, Bartz S, Kaelin WG., Jr Hypoxia-inducible factor linked to differential kidney cancer risk seen with type 2A and type 2B VHL mutations. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5381–5392. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00282-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Cao J, Liu J, Beshiri M, Fujiwara Y, Francis J, Cherniack A, Geisen C, Blair L, Zou M, et al. Loss of the RBP2 histone demethylase suppresses tumorigenesis in mice lacking Rb1 or Men1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110104108. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb E, Sarmiere P, Crowder R, Freeman R. Expression of the SM-20 gene promotes death in nerve growth factor-dependent sympathetic neurons. J Neurochem. 1999;73:429–432. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Bollig-Fischer A, Kreike B, van de Vijver MJ, Abrams J, Ethier SP, Yang ZQ. Genomic amplification and oncogenic properties of the GASC1 histone demethylase gene in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:4491–4500. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh YH, Zhang W, Chen X, George J, Ng HH. Jmjd1a and Jmjd2c histone H3 Lys 9 demethylases regulate self-renewal in embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2545–2557. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie ED, Selak MA, Tennant DA, Payne LJ, Crosby S, Frederiksen CM, Watson DG, Gottlieb E. Cell-permeating alpha-ketoglutarate derivatives alleviate pseudohypoxia in succinate dehydrogenase-deficient cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3282–3289. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01927-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranchie JK, Vasselli JR, Riss J, Bonifacino JS, Linehan WM, Klausner RD. The contribution of VHL substrate binding and HIF1-alpha to the phenotype of VHL loss in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marxsen JH, Stengel P, Doege K, Heikkinen P, Jokilehto T, Wagner T, Jelkmann W, Jaakkola P, Metzen E. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) promotes its degradation by induction of HIF-alpha-prolyl-4-hydroxylases. Biochem J. 2004;381:761–767. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoba S, Kang JG, Patino WD, Wragg A, Boehm M, Gavrilova O, Hurley PJ, Bunz F, Hwang PM. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell P, Dachs G, Gleadle J, Nicholls L, Harris A, Stratford I, Hankinson O, Pugh C, Ratcliffe P. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 modulates gene expression in solid tumors and influences both angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell P, Weisner M, Chang G-W, Clifford S, Vaux E, Pugh C, Maher E, Ratcliffe P. The von Hippel-Lindau gene product is necessary for oxgyen-dependent proteolysis of hypoxia-inducible factor α subunits. Nature. 1999;399:271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar J, Hickey MM, Pant DK, Durham AC, Sweet-Cordero A, Vachani A, Jacks T, Chodosh LA, Kissil JL, Simon MC, et al. HIF-2alpha deletion promotes Kras-driven lung tumor development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14182–14187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001296107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone M, Dettori D, Leite de Oliveira R, Loges S, Schmidt T, Jonckx B, Tian YM, Lanahan AA, Pollard P, Ruiz de Almodovar C, et al. Heterozygous deficiency of PHD2 restores tumor oxygenation and inhibits metastasis via endothelial normalization. Cell. 2009;136:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Padera RF, Bronson RT, Liao R, Kaelin WG., Jr A feedback loop involving the Phd3 prolyl hydroxylase tunes the mammalian hypoxic response in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5729–5741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00331-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mole DR, Schlemminger I, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Schofield CJ. 2-oxoglutarate analogue inhibitors of HIF prolyl hydroxylase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2677–2680. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MR, Hughes DJ, Tian YM, Ricketts CJ, Lau KW, Gentle D, Shuib S, Serrano-Fernandez P, Lubinski J, Wiesener MS, et al. Mutation analysis of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF1A and HIF2A in renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4337–4343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munirajan AK, Ando K, Mukai A, Takahashi M, Suenaga Y, Ohira M, Koda T, Hirota T, Ozaki T, Nakagawara A. KIF1Bbeta functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor gene mapped to chromosome 1p36.2 by inducing apoptotic cell death. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24426–24434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802316200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura E, Kaelin WG., Jr Recent insights into the molecular pathogenesis of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Pathol. 2006;17:97–106. doi: 10.1385/ep:17:2:97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcott PA, Nakahara Y, Wu X, Feuk L, Ellison DW, Croul S, Mack S, Kongkham PN, Peacock J, Dubuc A, et al. Multiple recurrent genetic events converge on control of histone lysine methylation in medulloblastoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:465–472. doi: 10.1038/ng.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips HS, Pujara K, Berman BP, Pan F, Pelloski CE, Sulman EP, Bhat KP, et al. Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm JE, McGarvey KM, Yu X, Cheng L, Schuebel KE, Cope L, Mohammad HP, Chen W, Daniel VC, Yu W, et al. A stem cell-like chromatin pattern may predispose tumor suppressor genes to DNA hypermethylation and heritable silencing. Nat Genet. 2007;39:237–242. doi: 10.1038/ng1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez de Heredia F, Wood IS, Trayhurn P. Hypoxia stimulates lactate release and modulates monocarboxylate transporter (MCT1, MCT2, and MCT4) expression in human adipocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:509–518. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfau R, Tzatsos A, Kampranis SC, Serebrennikova OB, Bear SE, Tsichlis PN. Members of a family of JmjC domain-containing oncoproteins immortalize embryonic fibroblasts via a JmjC domain-dependent process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1907–1912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711865105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard P, Loenarz C, Mole D, McDonough M, Gleadle J, Schofield C, Ratcliffe P. Regulation of Jumonji-domain-containing histone demethylases by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha. Biochem J. 2008;416:387–394. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard PJ, Briere JJ, Alam NA, Barwell J, Barclay E, Wortham NC, Hunt T, Mitchell M, Olpin S, Moat SJ, et al. Accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates and over-expression of HIF1alpha in tumours which result from germline FH and SDH mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2231–2239. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard PJ, Spencer-Dene B, Shukla D, Howarth K, Nye E, El-Bahrawy M, Deheragoda M, Joannou M, McDonald S, Martin A, et al. Targeted inactivation of fh1 causes proliferative renal cyst development and activation of the hypoxia pathway. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdue MP, Johansson M, Zelenika D, Toro JR, Scelo G, Moore LE, Prokhortchouk E, Wu X, Kiemeney LA, Gaborieau V, et al. Genome-wide association study of renal cell carcinoma identifies two susceptibility loci on 2p21 and 11q13.3. Nat Genet. 2011;43:60–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Biju MP, Liu Q, Unger TL, Rha J, Johnson RS, Simon MC, Keith B, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1068–1077. doi: 10.1172/JCI30117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Rha J, Selak MA, Unger TL, Keith B, Liu Q, Haase VH. HIF-2 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4527–4538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Rha J, Unger TL, Wu CH, Shutt HP, Johnson RS, Simon MC, Keith B, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 regulates vascular tumorigenesis in mice. Oncogene. 2008;27:5354–5358. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch A, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, Schmidt EC, Zabierowski SE, Brafford PA, Vultur A, Basu D, Gimotty P, Vogt T, Herlyn M. A temporarily distinct subpopulation of slow-cycling melanoma cells is required for continuous tumor growth. Cell. 2010;141:583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy PG, Thompson AM. Cyclin D1 and breast cancer. Breast. 2006;15:718–727. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L, Emre NC, Kruhlak MJ, Chung HJ, Steidl C, Slack G, Wright GW, Lenz G, Ngo VN, Shaffer AL, et al. Cooperative epigenetic modulation by cancer amplicon genes. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:590–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan H, Lo J, Johnson R. HIF-1α is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO. 1998;17:3005–3015. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran M, Kim WY, O’Connell F, Flippin L, Gunzler V, Horner JW, Depinho RA, Kaelin WG., Jr Mouse model for noninvasive imaging of HIF prolyl hydroxylase activity: assessment of an oral agent that stimulates erythropoietin production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:105–110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509459103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sar A, Ponjevic D, Nguyen M, Box AH, Demetrick DJ. Identification and characterization of demethylase JMJD1A as a gene upregulated in the human cellular response to hypoxia. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;337:223–234. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0805-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schietke R, Warnecke C, Wacker I, Schodel J, Mole DR, Campean V, Amann K, Goppelt-Struebe M, Behrens J, Eckardt KU, et al. The lysyl oxidases LOX and LOXL2 are necessary and sufficient to repress E-cadherin in hypoxia: insights into cellular transformation processes mediated by HIF-1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6658–6669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlemminger I, Mole DR, McNeill LA, Dhanda A, Hewitson KS, Tian YM, Ratcliffe PJ, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ. Analogues of dealanylalahopcin are inhibitors of human HIF prolyl hydroxylases. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1451–1454. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlisio S, Kenchappa RS, Vredeveld LC, George RE, Stewart R, Greulich H, Shahriari K, Nguyen NV, Pigny P, Dahia PL, et al. The kinesin KIF1Bbeta acts downstream from EglN3 to induce apoptosis and is a potential 1p36 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2008;22:884–893. doi: 10.1101/gad.1648608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seagroves T, Ryan H, Lu H, Wouters B, Knapp M, Thibault P, Laderoute K, Johnson R. Transcription factor HIF-1 is a necessary mediator of the pasteur effect in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3463–3444. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3436-3444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secombe J, Li L, Carlos L, Eisenman RN. The Trithorax group protein Lid is a trimethyl histone H3K4 demethylase required for dMyc-induced cell growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:537–551. doi: 10.1101/gad.1523007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selak MA, Armour SM, Mackenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, Gottlieb E. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selak MA, Duran RV, Gottlieb E. Redox stress is not essential for the pseudo-hypoxic phenotype of succinate dehydrogenase deficient cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers WR, Kaelin WG. Role of the Retinoblastoma Protein in the Pathogenesis of Human Cancer. J Clin Onc. 1997;15:3301–3312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.11.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Krop I, Porter D, Polyak K. Novel estrogen and tamoxifen induced genes identified by SAGE (Serial Analysis of Gene Expression) Oncogene. 2002;21:836–843. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C, Beroukhim R, Schumacher SE, Zhou J, Chang M, Signoretti S, Kaelin WG. Genetic and Functional Studies Implicate HIF1α as a 14q Kidney Cancer Suppressor Gene. Cancer Discovery. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0098. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Sun L, Li Q, Liang J, Yu W, Yi X, Yang X, Li Y, Han X, Zhang Y, et al. Histone demethylase JMJD2B coordinates H3K4/H3K9 methylation and promotes hormonally responsive breast carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7541–7546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017374108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EH, Janknecht R, Maher LJ., 3rd Succinate inhibition of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes in a yeast model of paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3136–3148. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeg PS, Zhou Q. Cyclins and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;52:17–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1006102916060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiehl DP, Wirthner R, Koditz J, Spielmann P, Camenisch G, Wenger RH. Increased prolyl 4-hydroxylase domain proteins compensate for decreased oxygen levels. Evidence for an autoregulatory oxygen-sensing system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23482–23491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub JA, Lipscomb EA, Yoshida ES, Freeman RS. Induction of SM-20 in PC12 cells leads to increased cytochrome c levels, accumulation of cytochrome c in the cytosol, and caspase-dependent cell death. J Neurochem. 2003;85:318–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarshan S, Shanmugasundaram K, Naylor SL, Lin S, Livi CB, O’Neill CF, Parekh DJ, Yeh IT, Sun LZ, Block K. Reduced Expression of Fumarate Hydratase in Clear Cell Renal Cancer Mediates HIF-2alpha Accumulation and Promotes Migration and Invasion. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarshan S, Sourbier C, Kong HS, Block K, Valera Romero VA, Yang Y, Galindo C, Mollapour M, Scroggins B, Goode N, et al. Fumarate hydratase deficiency in renal cancer induces glycolytic addiction and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1alpha stabilization by glucose-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4080–4090. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00483-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzatsos A, Pfau R, Kampranis SC, Tsichlis PN. Ndy1/KDM2B immortalizes mouse embryonic fibroblasts by repressing the Ink4a/Arf locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2641–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813139106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah MS, Davies AJ, Halestrap AP. The plasma membrane lactate transporter MCT4, but not MCT1, is up-regulated by hypoxia through a HIF-1alpha-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9030–9037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haaften G, Dalgliesh GL, Davies H, Chen L, Bignell G, Greenman C, Edkins S, Hardy C, O’Meara S, Teague J, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:521–523. doi: 10.1038/ng.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel KS, Brannan CI, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Parada LF. Loss of neurofibromin results in neurotrophin-independent survival of embryonic sensory and sympathetic neurons. Cell. 1995;82:733–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JK, Tsai MC, Poulin G, Adler AS, Chen S, Liu H, Shi Y, Chang HY. The histone demethylase UTX enables RB-dependent cell fate control. Genes Dev. 2010;24:327–332. doi: 10.1101/gad.1882610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellmann S, Bettkober M, Zelmer A, Seeger K, Faigle M, Eltzschig HK, Buhrer C. Hypoxia upregulates the histone demethylase JMJD1A via HIF-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:892–897. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Greschik H, Fodor BD, Jenuwein T, Vogler C, Schneider R, Gunther T, Buettner R, et al. Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and LSD1 promotes androgen receptor-dependent gene expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:347–353. doi: 10.1038/ncb1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X, Lemieux ME, Li W, Carroll JS, Brown M, Liu XS, Kung AL. Integrative analysis of HIF binding and transactivation reveals its role in maintaining histone methylation homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4260–4265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810067106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH, Ito S, Yang C, Xiao MT, Liu LX, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada D, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto H, Tomimaru Y, Noda T, Uemura M, Wada H, Marubashi S, Eguchi H, Tanemura M, et al. Role of the Hypoxia-Related Gene, JMJD1A, in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Clinical Impact on Recurrence after Hepatic Resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1797-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane K, Tateishi K, Klose RJ, Fang J, Fabrizio LA, Erdjument-Bromage H, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Tempst P, Zhang Y. PLU-1 is an H3K4 demethylase involved in transcriptional repression and breast cancer cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Jubb AM, Pike L, Buffa FM, Turley H, Baban D, Leek R, Gatter KC, Ragoussis J, Harris AL. The histone demethylase JMJD2B is regulated by estrogen receptor alpha and hypoxia, and is a key mediator of estrogen induced growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6456–6466. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZQ, Imoto I, Fukuda Y, Pimkhaokham A, Shimada Y, Imamura M, Sugano S, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J. Identification of a novel gene, GASC1, within an amplicon at 9p23-24 frequently detected in esophageal cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4735–4739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZQ, Imoto I, Pimkhaokham A, Shimada Y, Sasaki K, Oka M, Inazawa J. A novel amplicon at 9p23 - 24 in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus that lies proximal to GASC1 and harbors NFIB. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh IT, Lenci RE, Qin Y, Buddavarapu K, Ligon AH, Leteurtre E, Do Cao C, Cardot-Bauters C, Pigny P, Dahia PL. A germline mutation of the KIF1B beta gene on 1p36 in a family with neural and nonneural tumors. Hum Genet. 2008;124:279–285. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SJ, Pan J, Lee MH. Roles of p53, MYC and HIF-1 in regulating glycolysis - the seventh hallmark of cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3981–3999. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimi A, Kurokawa M. Key roles of histone methyltransferase and demethylase in leukemogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:415–424. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Gu J, Li L, Liu J, Luo B, Cheung HW, Boehm JS, Ni M, Geisen C, Root DE, et al. Control of cyclin D1 and breast tumorigenesis by the EglN2 prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Lin Y, Xu W, Jiang W, Zha Z, Wang P, Yu W, Li Z, Gong L, Peng Y, et al. Glioma-derived mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and induce HIF-1alpha. Science. 2009;324:261–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1170944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer M, Doucette D, Siddiqui N, Iliopoulos O. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor is sufficient for growth suppression of VHL−/− tumors. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]