Animal research has been and remains crucial to the development of modern medicine. The reasons for ongoing research are manifold from finding ways to treat cancer to understanding the mechanisms behind neurodegeneration to developing new vaccines against HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases. Nearly all of us benefit from medical treatments made possible through animal research, and with so much at stake, it is important that scientists make the case for the importance of using animals in research. With animal rights extremism at an all-time low, there has never been a better time for scientists to overcome their reluctance to talk about the benefits of their work.

Sadly, polls show that opposition to animal research among young people, for example in the UK and USA, is significantly higher than among those aged over 65 1,2. In my view, this is in part because of the large amount of misinformation propagated across the Internet by opponents of animal research—the “antivivisection” (AV) movement. Moreover, the past decades have seen bouts of intense activism—including harassment, threats and violence directed towards scientists—aimed at shutting down animal research. During the same period, the scientific community have worked diligently to replace, refine and reduce the use of animals in research (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk), making much progress; however, these efforts have not been sufficient to satisfy the passions of some activists.

Part of the problem is that scientists rarely engage with those who are opposed to animal research, which can leave them detached from the need to justify or explain their work. This lack of communication also creates an information vacuum in the public sphere about the need to use animals. In a recent poll in the UK, only 31% of respondents felt “fairly well informed […] about science and scientific research/development” 2.

“With animal rights extremism at an all-time low, there has never been a better time for scientists to overcome their reluctance to talk about the benefits of their work”

Ignoring the animal rights community has not worked. Wherever there has been a vacuum of understanding about research, they have filled it with disinformation based on rare instances of negligence and shocking examples of seemingly barbaric experiments, accompanied by stories describing animal research as unnecessary and out-dated. Some animal rights groups mask their aim to ban animal research behind the noble banner of animal welfare—legitimately criticising incidents involving substandard animal care but then implying that these represent not the exception, but the rule. Yet, the huge improvements in laboratory animal welfare will never satisfy those animal rights groups that have a fundamental ideological opposition to such experiments. Instead, AV groups often buttress their position with unfounded assertions that such methods can be entirely replaced or cannot provide useful results. As activists build a seemingly stronger—even if bogus—case against the value of using animals in research, the public support for, or indifference to, some illegal activities rises.

I actually dislike the term “antivivisection.” It is scientifically inaccurate, as much animal research is non-invasive and does not involve cutting live animals (vivisection). Nonetheless, those opposed to animal research, particularly in the UK, have taken the word to describe their movement and it is a useful term for their subsection of the wider animal rights movement.

I first became interested in the issue of animal research and animal rights as a student at Oxford University in the UK in 2005. Studying Philosophy, Politics and Economics, I was probably more qualified to become a politician than I was to discuss animal research, but as I returned to my second year at Oxford, the hot topic was that AV extremists had burned down our student boathouses in protest against the new animal research facility the university was building. I became interested in the subject and spent some time researching AV websites. I was surprised to discover claims that animal research does not work and that it has held back science by many decades. The “33 facts of vivisection” (http://www.animalliberationfront.com/Philosophy/Animal%20Testing/Vivisection/animaltests.htm), for example, references 33 claims (sometimes this list is expanded or reduced) as to why animal research does not work. What I found most concerning at the time was that the claims seemed to me to be the result of purposeful misrepresentation (http://speakingofresearch.com/2013/05/14/skeptical-science-debunking-animal-rights-misinformation/).

In early January 2005, it became apparent that a number of Oxford students felt the same way. The (now defunct) Oxford Gossip Internet forum was full of heated debates about animal research, and pro-research/anti-AV groups were gathering support on Facebook. At the same time, animal rights groups were posting calls to action to harass students, professors and partners of the university. On 22 January 2006, a communiqué from the Animal Liberation Front read: “This ALF team is calling out to the movement to unite and fight against the University on a maximum impact scale, we must stand up, DO WHATEVER IT TAKES and blow these fucking monsters off the face of the planet. Information, tools and resources are out there for everyone to take part in smashing the University of Oxford, all you need do is find them! All that stands between the animals and victory is our fear, GET OVER IT! Fear is their most valued weapon and the animals cannot afford for us to work within their boundaries. We must target their construction companies and the University’s current and future building projects. We must target professors, teachers, heads, students, investors, partners, supporters and ANYONE that dares to deal in any part of the University in any way. There is no time for debate and there is no time for protest, this is make or break time and from now on, ANYTHING GOES. We cannot fail these animals that will end up in those death chambers.” (http://www.directaction.info/news_jan22_06.htm). This climate of hostility and fear understandably deterred many scientists from speaking up for research, which left the animal rights movement free reign to control the arguments presented in the media.

Ultimately, the galvanisation of the animal research advocacy movement fell to Laurie Pycroft, a then 16-year old boy of whom British professor Sir Robert Winston described as having: “put the medical and scientific establishment, drug companies and universities to shame” (http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2006/may/31/animalwelfare.highereducation). On 28 January 2006, while visiting his girlfriend, Laurie came across an animal rights demonstration protesting against the construction of the new Oxford Biomedical Research Facility. Frustrated with what he saw, he entered a shop, bought a large piece of card and marker pen and made a placard saying “Support Progress—Build the Oxford Lab!” He stood near the animal rights protest and held up his sign, despite the abuse hurled at him by AV activists.

Laurie wrote a blog entry about his day (http://sqrrl101.livejournal.com/2006/01/28/), announcing that he would hold a pro-research rally in Oxford on February 25 to coincide with a national animal rights march through Oxford (a “pro-test,” one of his blog followers wryly noted). In response, a handful of Oxford students approached Laurie and the “Pro-Test” committee was born. The committee came to the decision that if we wanted people to follow us, we would have to shed our anonymity and come out publicly. To date, none of the committee has received anything nastier than a few vitriolic emails.

The Pro-Test rally was hugely successful and the headline in the Guardian said it all: “The silent majority finds a voice” (http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2006/feb/27/leadersandreply.mainsection). Outnumbering the AV rally more than five-to-one, 850 students, scientists and members of the public marched through the streets of Oxford. From this point on, the pro-research movement expanded rapidly, engaging in school, university, radio and TV debates up and down the country. Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister at the time, signed the Coalition for Medical Progress’s “People’s Petition,” which accumulated more than 20,000 signatures in support of animal research. Moreover, Blair wrote an open letter to the Telegraph newspaper stating his support for animal research and the Pro-Test movement (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1518328/Tony-Blair-Time-to-act-against-animal-rights-protesters.html). In June 2006, Pro-Test held a second rally, once again bringing hundreds of people to the streets of Oxford.

Oxford University opened its new Biomedical Sciences Building in October 2008, offering state of the art equipment and a “gold standard” in animal care (http://www.ox.ac.uk/animal_research/). Perhaps Pro-Test’s biggest contribution was breaking the taboo that said that those who supported animal research should not say so openly. It is a taboo that must continue to be broken.

In March 2008, I became a fellow in public outreach at Americans for Medical Progress (AMP, USA) and founded Speaking of Research (SR), which aimed to provide accurate information about animal research and help mobilise students and staff to defend it. Over the next year, a committee of researchers, advocates technicians and science communicators came together to help run SR, giving talks, writing articles and reaching out to those affected by AV extremism.

The USA presented different challenges to the UK. National coverage is much harder to come by: incidents in one state are often not reported in the next, causing institutions to believe that tackling activism is “someone else’s problem.” I spent much time touring facilities and it was easy to see stark differences in approach. Those who had been targeted by animal rights protesters in the past had opened up their facilities for local journalists and residents to see. In this way, their local communities could assess for themselves the veracity of animal rights accusations. Those universities that were less open sometimes found themselves on the end of a protracted animal rights campaign. Scientists at UCLA, for example, had their houses flooded and were sent bombs and razor blades by mail (http://articles.latimes.com/2010/nov/25/local/la-me-targeted-professor-20101125). It was beginning to look like Oxford all over again.

In 2009, several weeks after David Jentsch, Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry & Behavioural Sciences at UCLA, had his car firebombed by the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), he and a small committee, myself included, organised a rally to stand up against this extremism. UCLA Pro-Test was born; it was later renamed Pro-Test for Science.

On 22 April 2009, 40 animal rights activists gathered for World Week for Animals in Laboratories. Across the road, approximately 800 scientists, animal technicians and other members of UCLA marched in support of science and in opposition to animal rights extremism. The rally gave scientists an opportunity to explain the importance of animal research to journalists and members of the UCLA community. The Pro-Test petition launched at the event garnered more than 11,000 signatures and was handed to representatives of the NIH at a second pro-research rally 1 year later (http://speakingofresearch.com/get-involved/ucla-pro-test/).

As SR marks its sixth birthday, I have learnt the importance of scientists supporting one another. Many researchers have felt isolated by their institution’s leadership, some of whom would rather end controversial research than stand up to activists. SR has always aimed to reach out to those researchers who have been targeted, giving them an outlet to discuss their research when their institution will not.

During 8 years of involvement, I have seen many different approaches to communicating the role of animals in research—everything from open discussion to a complete unwillingness to even acknowledge such research is conducted at an institution. I have also had many opportunities to interact and discuss with those opposed to animal research. This has allowed me to build a picture of how I believe the AV movement functions, how it is structured and the factors affecting its size and strength.

“Many researchers have felt isolated by their institution’s leadership, some of whom would rather end controversial research than stand up to activists”

AV groups and organisations vary in size and structure. Some can count their members on the one hand, while others, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA, USA; www.peta.org), claim their membership in millions. Many of the larger animal rights organisations deal with a variety of related issues including animals for food, fur farming, pet ownership and hunting, while smaller groups often focus on just one issue.

Activists are those employed, either professionally or as volunteers, by AV groups (AVGs) and AV organisations (AVOs). While the line between AVGs and AVOs is not clear-cut, AVOs are usually formal organisations that employ staff and tend to have a much larger turnover and greater assets. Examples of AVOs would include the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV; UK), Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM; USA) and PETA. Conversely, AVGs tend to be smaller, usually less established groups that do not salary their members, but may remunerate them for work done. Examples include Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC; UK), SPEAK (UK), Negotiation is Over (NIO; USA) and Fermare Green Hill (Stop Green Hill; Italy). AVGs may grow into AVOs; both PETA and SAEN (Stop Animal Exploitation Now!, USA) grew from being groups of like-minded people into tax-registered non-profits. However, many AVGs appear to prefer the flexibility associated with their informality and small size.

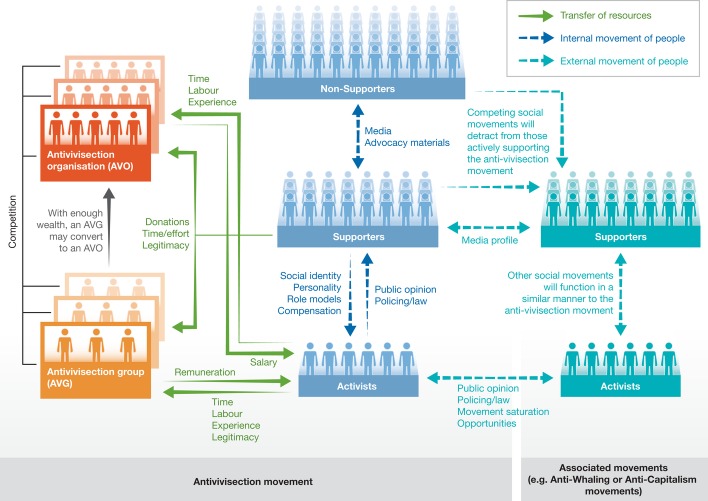

To study the AV movement, it is important to keep in mind that animal rights activism has become a profession for many of those involved. While many sociologists originally believed that social movements were simply forms of collective action by individuals with common grievances, the view was later criticised as incomplete since many such grievances exist without associated social movements. The development of Resource Mobilisation Theory (RMT) noted that individuals require sufficient resources to be available to form a movement and that this has a significant impact on the potential success of a movement 3. Figure 1 uses RMT to illustrate the movement of people and resources in the AV movement. Key resources include money, communication tools, influential networks and the activists themselves.

Figure 1. A model of the antivivisection movement.

The blue dashed arrows indicate the movement of people within the antivivisection movement: a person might read the website of an AVG and decide to change from non-supporter (either someone who disagrees with the AV views or has not formed an opinion either way) to a supporter, donating money or spending their time and effort signing petitions. The green arrows denote the movement of resources (e.g. time and money), though it should be noted that these are not exhaustive lists of resources. In return for their time and effort, that person might get a “feel-good buzz” about helping animals, or from the acceptance of their peers. Later, they might decide to get more involved. This change is the movement from supporter to activist (though the divisions are not clear-cut). The activist still feels good about what he or she is doing—possibly with a greater social acceptance from their newfound colleagues—and might also find himself or herself remunerated. Note that by giving time or money to any one AVG/AVO, they are choosing not to give those resources to another, so there is a natural competition between these AVGs/AVOs. Years later, the person might find they have less time and will drop back to supporter status, or might find that the massive publicity surrounding an associated movement draws their time and effort (turquoise dashed arrows), such that they stop their involvement with the original AV movement. Such associated movements need not have any relation to animal rights, but the more similar they are to the AV movement, the more competition there will be. Legitimacy is an important resource that both supporters and activists provide. An animal rights group that can only muster 20 supporters at important demonstrations will eventually find its supporters moving to competing AVG/AVOs. When the entire antivivisection movement comes under negative media spotlight, or as laws or police activities make certain activities more difficult, many supporters may move to other associated movements, and many activists may choose to put their expertise into other areas.

The amount of money provided by supporters is not small. In the USA, PETA had an income of US$35.3 million in 2013 (http://features.peta.org/annual-review-2013/year.aspx), while the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) received US$180 million in 2012 (http://www.humanesociety.org/about/overview/financials/annual-report-2012.html) from its 11 million supporters. The combined income of the three largest AV organisations in the UK exceeds £5 million. Even non-registered groups can accrue large sums of money. SHAC activists amassed “around £1 million in donations to SHAC’s collection buckets and bank account” (http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/uk/crime/article1875508.ece).

Given these sums, it is not surprising to see a certain level of competition for supporters and funding between organisations. The AVOs work hard to break the biggest stories, for example through undercover filming or by trawling through research papers or reports for sensational and often groundless claims about animal abuse. Between 2007 and 2011, for example, SAEN made more than six complaints per year to the USDA (http://www.all-creatures.org/saen/usda.html), often following up on rejected complaints with accusations that the USDA was failing in its role of regulator (e.g. http://www.all-creatures.org/saen/usda-oig-20101209.html). In 2012, PETA alleged animal cruelty relating to sound localisation experiments on cats at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Both the USDA and the National Institutes of Health Office of Laboratory Animal cleared the university and found the allegations baseless.

Despite the competition and some friction between animal rights groups, many appear to be closely intertwined, with activists moving between them. Jerry Vlasak, who is currently a press officer for the Animal Liberation Press Office—the mouthpiece for the ALF—has been involved in SPEAK, the Animal Defence League, Sea Shepherd and PCRM. These fluid movements are reminiscent of the way top businessmen move between the boards of firms as the skills gained within the animal rights movement are easily transferable. Alistair Currie moved from Campaign Director at BUAV to Campaign Coordinator at PETA and finally left the AV movement to become a spokesman for Free Tibet. Just as an experienced marketing consultant may move from a clothes firm to a car manufacturer, so a professional activist moves from movement to movement as the relative tides change. This reflects the professional nature of activism; however, some activists have suggested a “contamination” effect from animal rights activism that can make it harder to move out of the AV movement and into unrelated areas of campaigning.

However, it would seem that some prominent activists have also risen through the ranks, particularly of AVGs, on the back of extreme activities they have carried out under the banner of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), an extremist group made up of small autonomous cells. Mel Broughton was convicted of conspiracy to commit arson in 1999 but went on to lead several campaigns, including against Oxford University. Luke Steele was sentenced to 18 months in 2012 for “harassing staff at Harlan laboratories” (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/9151122/The-animal-rights-lone-wolf-feared-by-the-ferry-firms.html) and now runs several AV organisations including the Anti-Vivisection Coalition. Those serving prison sentenced gain prestige among parts of the AV community who support them (http://www.alfsg.org.uk) and are quick to welcome them back into the fold upon release.

The tide of resources into the AV movement has ebbed and flowed over time. In 1903, after Stephen Coleridge, head of the National Anti-Vivisection Society, lost £2,000 (over £200,000 in today’s money) in a libel action brought by the researcher William Bayliss during the Brown Dog Affair 4, the issue of animal research came to the attention of the media. As a result, resources flowed in; NAVS raised £5,735 (over £500,000 in today’s money) in just 4 months. Growing public disquiet about animal research also led to a string of dog protection bills being presented to parliament including the 1906 Dogs Act.

Activism waxed and waned in the following decades. In the 1960s, Ronnie Lee founded Band of Mercy, a direct action hunt saboteur group. Such groups helped to train animal rights activists in direct action methods (http://www.nocompromise.org/issues/18thirty_years.html). In 1975, the Australian philosopher Peter Singer wrote the seminal book, Animal Liberation, which provided the moral case for a new generation of activists 5. The following year Ronnie Lee founded the Animal Liberation Front (ALF). The 1980s saw the founding of the Animal Rights Militia, who sent bombs to politicians and animal researchers. By the early 1990s, AVGs were becoming more active. Extreme groups such as the Justice Department and Animal Rights Militia were abandoning the doctrine of non-violence. There were dozens of bomb attacks against researchers and organisations (http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/nocturnal-creatures-of-violence-1536717.html).

In 1996–1997, activists Greg Avery and his first wife Heather Nicholson ran a 10-month campaign that closed the Consort Kennels, a facility that bred dogs for medical research. In 1997, activists began a similar campaign that would eventually close Hillgrove Cat Farm. These campaigns were, on the face of it, legally conducted protests. Nonetheless, as support flowed in, some activists believed they had licence to take more extreme, illegal, actions: the Hillgrove Cat Farm campaign resulted in 21 jail sentences.

In 1999, Avery founded SHAC, whose members harassed and threatened staff at Huntingdon Life Sciences (HLS), HLS’s clients and HLS’s clients’ other clients over a period of 10 years. These tactics have spread widely: the same were used in Oxford to target the contractors, and the HLS campaign was exported to the USA in 2004 under the leadership of Kevin Kjonaas, who had spent 2 years working with Avery in the UK. John Cook, the author of a Salon article on SHAC, summarises their tactics thus: “SHAC’s modus operandi is simple, elegant and shockingly effective: Publish the names, home addresses and telephone numbers of executives and employees of Huntingdon and any companies it does business with; identify these individuals as ‘targets’” 6.

The approach of seasoned activists is professional: they take on a campaign, complete it and then look for the next one to start. It seems to me that the speed and size of a campaign is often determined by the donations to the previous campaign; in my analysis, each of Greg Avery’s campaigns was bigger than the last. As such, successful campaign leaders become role models and groom supporters to become activists (Fig 1).

Most campaigns have been relatively short. Consort Kennels was closed in 10 months, Stop Primate Experimentation at Cambridge achieved its goals within 1 year and its successor, SPEAK, forced out the first Oxford lab building contractors in less than 6 months. As a campaign drags on, it can become harder to find supporters to volunteer time and money to the cause. This can increase the pressure to take more desperate measures. Perhaps the most drastic was the grave-robbing of Gladys Hammond’s body by the Animal Rights Militia (ARM) in 2004. As the Save the Newchurch Guinea Pigs campaign (SNGP) dragged into its fifth year, ARM extremists stole the remains of the deceased mother-in-law of one of the guinea pig farm’s owners. Four members of SNGP were later convicted of using the desecration to blackmail the family into shutting down the farm, which happened the following year.

Such actions brought widespread public condemnation and the British police were granted new powers to tackle animal rights extremism. The UK Government set up the National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit (NETCU) to deal with domestic extremism. The crackdown and subsequent arrests included Mel Broughton (10 years), Greg Avery (9 years) and Kevin Kjonaas (6 years). Suddenly young activists were deprived of experienced mentors and many AV activists moved into other related movements. For example, Amanda King, a British protester who was previously involved in the campaign against Oxford University and the Newchurch guinea pig campaign, was most recently involved in protesting against the UK Government’s proposed badger cull. Alongside her were veteran hunt saboteurs and campaigners who had protested against HLS and Hillgrove Cat Farm, UK (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/agriculture/farming/9560130/Badger-cull-the-fanatics-hijacking-the-badger-cause.html).

AV extremism fell steadily from around 2005, which was likely due to a number of factors. NETCU focused heavily on animal rights extremism, with judges handing down harsher sentences. Pro-research communication was also increasing with the Coalition for Medical Progress and the Science Media Centre both founded in 2002, and the Pro-Test movement was gaining widespread media and public support. Finally, the public condemnation that followed high profile incidents, such as the grave-robbing of Gladys Hammond, made animal rights a less attractive issue for young activists.

While extremism in the UK and USA has fallen to an all-time low, there are signs that activism is on the rise in other countries. In particular, activists from across Europe are targeting Italian pharmaceutical companies, universities and breeders in a sustained campaign that may pose a serious threat to research in Italy. In the past 2 years, activists have broken into a beagle breeding facility at Green Hill, “liberating” dozens of dogs (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-17894881); blockaded a shipment of beagles to the pharmaceutical company Menarini until the dogs were given to activists (http://www.ilcorrieredellacitta.com/cronaca/menarini-salvi-i-cuccioli-di-beagle-niente-sperimentazione-ma-adozione.html); and broken into the University of Milan, where they mixed up the animals’ records and seized approximately 100 animals. Fortunately, a vigorous response is already underway, with the newly formed Pro-Test Italia attracting hundreds of scientists to rallies in Milan and Rome. Nonetheless, such strong responses are few and far between—after a Brazilian research facility recently shut down after activists raided it, taking almost 200 dogs (http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/437964/Activists-free-dogs-from-Brazil-lab), there was only minimal response from the scientific community.

“In particular, activists from across Europe are targeting Italian pharmaceutical companies, universities and breeders in a sustained campaign”

Back in the UK, online campaigns against universities seem to be increasing in number and magnitude, while a multi-faceted campaign by many AVGs and AVOs to prevent airlines transporting primates has left only a few willing to do so. In January 2012, the last of the ferry companies transporting laboratory animals across the English Channel stopped its service as a result of pressure from AV groups.

So what should we be doing now? Thanks to the efforts of pro-advocacy groups and the outreach activities of many research institutions and scientists, there have been positive developments in how we discuss the use of animals in research. Furthermore, as many extremists in the UK and USA are in jail, or are recently released and under control orders that ban them from being involved in AV activism, there is little danger of extremism.

Scientists must spend more time explaining their work to the public, why animals are vital to biomedical research and the measures taken to minimise their suffering in laboratories. Social networks and online outlets, such as university departmental webpages, science blogs, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, all offer ways for scientists to interact with the public—particularly younger audiences. Understanding Animal Research’s (UAR) “Science Action Network” points the scientific community towards articles that misrepresent animal research and posts links to Twitter with the hashtag #ARnonsense. Scientists who search for this hashtag, or who follow @ARnonsenseRT, can then go to these articles and leave comments correcting the misinformation within them. The result is that members of the public who come across these articles can quickly reassess their content.

Younger scientists often find it the hardest to speak up. Nevertheless, their voices are important. Start small; conversations with friends and family play a crucial part in “normalising” the issue of animal research, as well as practising science communication skills. Simple things like sharing animal research stories on Twitter or making mention of animal research on Facebook provide another avenue for discussion. A step further would be to write for a blog, student or local newspaper. Speaking of Research started a series of guest posts entitled “Speaking of Your Research” to provide scientists and animal care staff with a safe environment to discuss why they use animals (www.speakingofresearch.com). With science becoming more popular with the general public, there has never been a better time to discuss this issue (note the 12+ million likes for the “I Fucking Love Science” Facebook page).

“… scientists still go surprisingly quiet about animal research.”

While researchers directly involved in animal research are in the best position to talk about what they do, they are also open to accusations of bias. Therefore, it is important that the rest of the scientific community helps to explain why such research is carried out. All scientists should promote the value of both basic and applied science in all fields. I know plenty of researchers who have defended the Rothamsted Research Institute’s genetically modified wheat trials in the UK in the face of anti-GM protests in May 2012. Yet, scientists still go surprisingly quiet about animal research.

Institutions must also speak louder. It was reassuring, for instance, that the Bremen University in Germany legally and financially supported researcher Andreas Kreiter against attempts to shut down his research on macaque monkeys. Yet, in my view, too many research institutions, particularly in the USA, lack clear and open statements about the existence and importance of their animal research programmes. This is especially true of those organisations which fund, but do not carry out, animal research, such as medical research charities. The more details provided, along with pictures and videos, the better; otherwise, activists will be happy to supply their own, unrepresentative images. Organisations also need to work with local communities, inviting residents and journalists to tour facilities and sending scientists to schools in the local area. This can help minimise the resources (of local supporters) available to a new AV campaign (Fig 1). Importantly, such actions must happen in the good times, or else risk being perceived as a cheap public relations stunt.

“The more details provided, along with pictures and videos, the better; otherwise, activists will be happy to supply their own, unrepresentative images”

While we still have a way to go, the UK continues to provide the best practice in pro-research advocacy. Newspapers regularly report on interesting or promising research involving animals, thereby normalising the animal research issue. Universities and other institutions have driven this change by mentioning the animals used in research more regularly. Nonetheless, the long wait between initial studies in animals and the launch of new treatments means that the public can often lose sight of the link between the two. Those working on clinical research have a duty to recognise the contribution of animals when discussing new therapies with the press. In 2012, more than 40 institutions and organisations signed the Declaration on Openness, pledging to do more to communicate the important research they carry out (http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/science/medicine/article3574380.ece). This is a positive step that could be emulated in other countries.

Sidebar A: Activism and extremism —

It is useful to make a distinction between activism and extremism. Activism is the use of legal campaigning techniques to bring about a change. Such activities include letter-writing campaigns, producing leaflets and peaceful demonstrations—all hallmarks of an open democracy. Extremism is where activism moves beyond the law. This can include vandalism, harassment, breaking into research facilities, and even arson and physical violence.

Medical research involving animals is important to all of us, and we all have a duty to provide the accurate information the public needs to make up their mind.

Conflict of interest

This author is a former spokesman for Pro-Test; former Michael D Hayre Fellow in Public Outreach for AMP; founding member of Pro-Test for Science. [Correction added after first online publication 28 April 2014: in the preceding sentence the following Conflict of interest was added “and current Campaigns Manager for Understanding Animal Research”.]

References

- Pew Research. Scientific Achievements Less Prominent Than a Decade Ago. Washington, DC: The Pew Research Center; 2009. http://www.people-press.org/2009/07/09/section-5-evolution-climate-change-and-other-issues/ [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos Mori. Views on the Use of Animals in Research. London, UK: 2012. Ipsos Mori. http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/biscore/innovation/docs/I/ipsos-mori-views-on-use-of-animals-in-scientific-research-September-2012. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JD, Zald ZN. Resource mobilization and social movements: a partial theory. Am J Sociol. 1977;82:1212–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Illman J. Animal Research in Medicine: 100 years of Politics, Protests and Progress. The Story of the Research Defence Society. London: Research Defence Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Singer P. The Animal Liberation Movement: its Philosophy, its Achievements, and its Future. Nottingham: Russell Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cook J. 2006. Thugs for puppies. Salon, Feb 7. www.salon.com/2006/02/07/thugs_puppies/