Abstract

Youth are infrequently included in planning the health promotion projects designed to benefit them as many of the factors infringing upon youth’s health and well-being also limit their engagement in community-based public health promotion projects. This article explores youth engagement in 13 coalitions implementing structural changes meant to reduce HIV transmission among adolescents. There was wide variation of youth membership and involvement across coalitions. Using analytic induction, the authors show that youth engagement was associated with the successful completion of structural change efforts. The authors also describe how youth engagement indirectly facilitated coalitions’ success. The authors suggest that youth engagement in planning and conducting structural interventions is itself a valuable structural change.

Keywords: coalitions, HIV/AIDS, structural interventions, youth

Introduction

Structural interventions are increasingly touted as necessary for quelling the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Gupta, Parkhurst, Ogden, Aggleton, & Mahal, 2008; Piot, Bartos, Larson, Zewdie, & Mane, 2008; Wohlfeiler & Ellen, 2007) and for preventing the spread of HIV among youth (Rothrum-Borus, 2000). Structural change interventions modify aspects of the social, economic, and political environments that influence public health problems (Blankenship, Bray, & Merson, 2000). Despite a decade of calls for their implementation and assessment, structural interventions have rarely been developed (Blankenship, Friedman, Dworkin, & Mantell, 2006) or evaluated (Bonell, Hargreaves, Strange, Pronyk, & Porter, 2006). We know little about the implementation of structural interventions or about the role of youth in such efforts.

Youth (aged 12–24) are often excluded from meaningful involvement in health promotion projects that are designed to affect them, as many of the factors infringing upon their health and well-being also limit their engagement in community-based promotion projects (Boyce, 2001; Kohfeldt, Chhun, Grace, & Langhout, 2011; Wong, Zimmerman, & Parker, 2010; Miller, Reed, Francisco, Ellen, & the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, in press). Having youth participate in problem identification and solution setting when they are the intended beneficiaries of health promotion efforts may enhance the utility of proposed solutions and promote cause-based passion among adult members (Camino, & Zeldin, 2002; Powers & Tiffany, 2006). Proposed solutions may also better reflect youth’s needs, as youth possess the most intimate knowledge of their concerns. Youth’s perspective on the social problems affecting them and programs that serve them is, therefore, imperative to improve the community relevance and acceptability of solutions to youth’s public health problems (Prilleltensky, 2010; Zimmerman & Erbstein, 1999). Although youth involvement is believed to improve youth-focused programming in community-based health initiatives, we have little evidence that their involvement in structurally focused interventions is advantageous.

There are significant obstacles to involving youth in participatory health promotion approaches. A predisposition by staff that processes be led by professionals rather than laypersons (Boyce, 2001), and adults rather than children, may limit youth participation. Participation may also be affected by youth’s life situations (Boyce, 2001), such as transience and lack of resources or by emergent capabilities, such as learning to balance school, family, and work obligations. Adult attitudes toward youth may also pose an obstacle to youth participation. Youth are often viewed by adults as lacking requisite knowledge and skills to enable participation (Gurstein, Lovato, & Ross, 2003; Wong et al., 2010). These beliefs can result in young people’s knowledge being undervalued or dismissed and may prevent adults from seeing youth as equal partners capable of contributing to social change (Camino & Zeldin, 2002). These beliefs may also undermine authentic participation and create adult–youth power imbalances that lead youth to question their own abilities and legitimacy (Checkoway & Richards-Schuster, 2001).

Adults may lack necessary skills and knowledge of how to engage young people in social change and health promotion efforts (Finn & Checkoway, 1998). A truly participatory approach may require a shift in philosophy (Dallape, 1996) and willingness on the part of adults to reduce power imbalances and create partisan relationships with youth (Nelson, Prilleltensky, & MacGillivary, 2001). Participatory approaches may require adults shift their view of youth from one in which youth are viewed solely as sources of community representation to one in which youth are viewed as having unique competencies, needs, preferences, and values.

Barriers to youth participation may be particularly acute in structurally focused interventions. Structural interventions require changes in law, policy, social values, and organizational procedures (e.g., Blankenship et al., 2000), and efforts needed to advance these changes are likely to occur in social arenas in which youth rarely participate. Whether or not youth are capable of contributing to policy change efforts, adults may believe that they are more appropriately involved in programmatic interventions. Furthermore, identifying structural changes may be difficult for adults given that doing so may require a shift in the way they think of health risks (e.g., away from individual-level causes and toward community-level or structural causes of health risk; Blankenship et al., 2006, Willard, Chutuape, Stines, Ellen, & the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, 2010). Adults’ difficulty designing such interventions may make them more prone to believing youth incapable of making meaningful contributions. Organizations or coalitions working toward structural changes may face more process and implementation difficulties than groups working toward changes that are more conventional. For example, politically controversial structural changes (e.g., needle exchange programs) require social and community transformation and, therefore, face many obstacles to implementation (Miller, Reed, Francisco, Ellen, & the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, in press). These features of structural change may make it harder for adults to dedicate time and resources to youth participation or more difficult to see the value of youth involvement amid so many other pressing concerns. The challenges unique to structural interventions may exacerbate the tendencies of adults to ignore youth participation.

The Current Study

The current study examines the contribution of youth to the pursuit of structural change in HIV prevention. Connect to Protect® (C2P) is an Adolescent Medicine Trials Network–supported research initiative designed to institute structural changes that impact youth’s risk of exposure to HIV through the creation of community coalitions. To meet C2P’s goal, coalition members develop and carry out structural change objectives (SCOs), which they define as new or modified laws and policies meant “to create opportunities or remove barriers to promote HIV prevention” (Chutuape et al., 2010, p. 2). As an example, an objective implemented by the one coalition was as follows: “By school year 07–08, DC public schools will have a policy in place that mandates HIV risk reduction classes for all 9th grade and new DC public school students.” To identify locally relevant objectives, coalition members engage in root cause analysis to identify the community- and structural-level causes of a particular problem (Willard et al., in press).

This article describes 13 C2P coalitions, each of which is focused on a specific youth population at high risk of exposure to HIV in their local community (e.g., young men who have sex with men, heterosexual women, or injection drug users). Despite their differing target populations, these coalitions follow a relatively homogeneous set of processes because they operate under the provision of a large-scale national protocol (Ziff et al., 2006). A national coordinating council works with the coalitions to assure protocol adherence, guide coalition development, provide technical assistance, and offer ongoing feedback to coalition staff. Drawing from state-of-the-science work on community mobilization (Fawcett, Francisco, Hyra et al., 2000; Fawcett, Francisco, & Paine-Andrews, 2000; Francisco, Fawcett, Schultz, & Pain-Andrews, 2000), the coalitions engaged in parallel partnership formation and strategic planning processes, capacity-building exercises, and data monitoring procedures. Although operating procedures and management are similar, coalitions’ composition and structure differs in response to local needs, capacities, and members’ interests.

Each of the 13 coalitions is affiliated with a university or adolescent-focused clinical trials site (e.g., Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia). In addition to the C2P coalitions, each trial site also selected a community-level intervention from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) compendium of HIV prevention interventions with evidence of effectiveness to implement in their target communities. Sites were selected between implementing the Mpowerment Project (Kegeles, Hays, & Coates, 1996) or Community Promise (CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects Research Group, 1999) interventions. Staff who worked in parallel with coalition staff implemented the interventions as complimentary activities to the coalitions’ efforts.

The C2P protocol does not stipulate any required level of youth involvement. Although youth were not required to participate in the coalitions, there was awareness among C2P personnel that their input may be beneficial. C2P personnel hoped that the evidence-based interventions would attract youth and provide a mechanism by which to engage them in the coalitions’ efforts. C2P organizers believed that having a formal and well-resourced mechanism in place to support youth engagement might provide a way to alleviate well-documented barriers to youth participation in collaborative processes (Boyce, 2001; Camino & Zeldin, 2002; Gurstein et al., 2003; Powers & Tiffany, 2006; Prilleltensky, 2010; Wong et al., 2010). In addition, implementing the interventions might assuage some of the difficulties typical of coalitions pursuing structural change. Engaging youth via the interventions and offering activities associated with the interventions could provide coalition members with the experience of short-term success. As Kubisch and colleagues point out (Kubisch, Auspos, Brown, & Dewar, 2010), quick wins help build momentum when broader social and policy changes and reform are pursued. The intent was for the interventions to provide the coalitions with quick wins.

Method

To explore the contributions of youth to C2P, we analyzed secondary data that spanned the time from coalition inception in early 2006 to the end of 2008. Data for the current analyses come from the routine protocol monitoring reports provided by the coalitions to C2P’s coordinating center. Key actor logs listed all coalition members (including youth). Community action logs and action step reports charted how youth and other coalition members were involved in the completion of objectives. Adult coalition members and key informants at each coalition participated in structured interviews about beliefs regarding youth involvement, activities in which youth participated, and the influence of youth on coalition activities. Researchers who were external to the coalitions and located at an independent site in Chicago conducted the interviews.

For this analysis, we classified coalitions as successful based on their rate of SCO completion. Despite the limitations of simple counts, simple counts are used in C2P as the primary performance criteria against which coalitions are assessed, and simple counts are consistent with the recommendations of Fawcett and colleagues, on whose work these coalitions’ were based (Fawcett et al., 2000). (Elsewhere we note the great diversity within these coalitions in the complexity, reach, and quality of objectives—Miller, Reed, Fransisco, & the Adolescent Medical Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, in press—and discuss the limitations of simple counts as measure of accomplishment.) We coded the objectives as completed, abandoned, or still in progress. Of 304 established objectives, 137 were completed. Coalitions accomplishing more than half of their objectives (n = 7) were categorized as high-success coalitions; the remaining coalitions (n = 6) were categorized as low-success coalitions.

Analysis

We conducted analytic induction (Erickson, 1986). We chose this form of analysis because it allows researchers to work with a variety of different data sources and is an ideal, qualitatively driven approach for analyzing both qualitative and enumerated data (Becker, 1953; Smith, 1997). Researchers use analytic induction to develop, modify, and test assertions—comparable to quantitative hypotheses—inductively derived from empirical data. Analytic induction allows researchers to develop assertions based on extant literature and theory, our assumptions, or initial reads of the data. Consistent with analytic induction, we formed assertions regarding youth participation and then tested our assertions against the data. We formed these assertions after inspection of initial cases (i.e., each coalition was considered a case). As analytic induction entails the progressive redefinition of assertions, we altered these provisional statements based on examination of the remaining cases. In general, our assertions assumed that engaging youth would be associated with greater success.

In this iterative analytic process, negative cases—those that do not readily conform to the initial assertions—result in the evolution of assertions so that remaining assertions account for all cases. Notably, researchers may rework assertions until they are maximally generalizable across cases or may consider cases outside the scope of the inquiry. In the latter circumstance, there is a solid warrant to discard a case. Assertions apply to those cases that remain. Throughout the text, we explain our decisions regarding negative cases as a way to facilitate transparency regarding our analytic decision making.

To analyze our first assertion that youth coalition involvement was associated with the successful completion of structural changes, we quantified the number of completed objectives, objectives in which youth were actively involved, and coalition members listed as youth on key actor logs. We then used descriptive statistics to explore whether higher rates of youth coalition membership and involvement were associated with rates of SCO completion. We analyzed the remaining assertions using the narrative documents. All narrative records were analyzed using NVivo 8 (QSR International, 2008), a qualitative data management program. We first reduced the data corpus by conducing text searches for mentions of youth members, members’ feelings toward youth, and discussion of the Mpowerment and Promise interventions (because youth may have become involved in the coalitions through participation in the interventions). We then applied codes that indicated coalition members’ and coordinators’ opinions of youth, efforts to engage youth, and perspectives on how youth members influenced coalition activities.

Results

Across all coalitions, the percentage of youth coalition members was highly variable (M = 12.04%, SD = 9.11%); coalitions reported 1 to 62 youth members, and youth made up 1% to 32% of coalition members. Youth members joined coalitions through their acquaintance with adult coalition members, involvement in the CDC interventions, or by staff request. Youth were often members of the coalitions’ target population and though we do not have demographic data on the youth members, coalition staff informed us that most were toward the upper (18–24) end of the target population’s age spectrum.

In the results that follow, we outline the evidence for two assertions related to youth engagement.

Youth Membership and Involvement Was Associated With Completion of SCOs

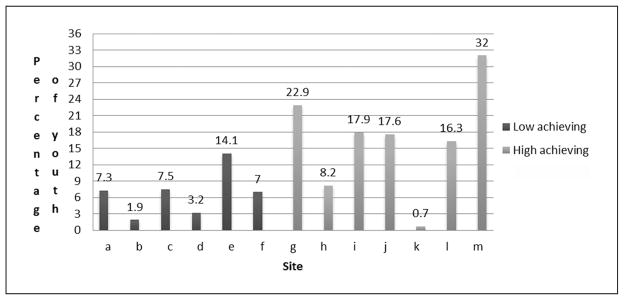

We hypothesized that higher rates of youth involvement would be associated with higher rates of objective completion. Coalitions that engaged larger numbers of youth attained their objectives at high rates (Figure 1). Most high-achieving coalitions had at least 15% of members who were youth (M = 19.15%, SD = 7.89); low-achieving coalitions had fewer youth members (M = 6.83%, SD = 4.27). The one high-achieving coalition (Coalition K) with low youth membership numbers routinely collaborated on objectives with another coalition (Site M) such that its apparent low number of youth members failed to reflect this close collaboration.

Figure 1.

Percentage of youth members involved in C2P (Connect to Protect®) coalitions, 2006–2008

With 1% youth membership, Site K constituted a negative case and warranted further analytic attention. Once we examined Site K’s data in more detail, we determined that Site K was dependent on Site M. During the time in question, Site K worked closely with Site M—so closely that one third of Site K’s accomplished objectives were jointly achieved with Site M. Site M created all of the joint objectives, had their members complete the action steps associated with these objectives, and had reached out to Site K to join them. Site M was thus the “lead” site among the two. Because we were able to determine the nature of the relationship between these two coalitions, we were able to make a data-informed decision to exclude Site K on the basis that it was dependent, unlike the other sites. With K excluded, the rate of objective completion correlated strongly with the percentage of youth listed as coalition members, r (n = 12) = 0.75, p < .001.

Because coalitions may list youth as members when they contribute little effort to coalition activities, we examined in more depth only the objectives in which youth were actively engaged. Youth members were involved in activities related to 39 objectives. Typically, youth participated on subcommittees designing objectives and completing tasks that had to be accomplished to implement the objective. All high-achieving coalitions reported that youth were involved in at least 1 objective (M = 4.14); half of all low-achieving coalitions, including Site E with a relatively high proportion of youth members, did not report youth involvement in any objectives (M = 1.67). In addition, having a relatively high proportion of youth members at low-achieving sites did not mean that these youth were engaged members who directly contributed to accomplishing SCOs. Thus, youth were more likely to be involved in objective formation and implementation at high-achieving coalitions than at low-achieving coalitions.

Objectives in which youth were involved were more likely to be completed than those in which they were uninvolved. Of the youth-involved objectives that were either completed or discontinued, 72.7% were completed and only 27.3% were discontinued (the remaining were still active). Youth-involved objectives were significantly more likely to be achieved than were objectives in which youth were uninvolved (72.7% vs. 55.5%); χ2(242) = 3.65, p < .05.

Coalitions with the most youth-involved objectives more frequently reported that youth attended subcommittee meetings than did coalitions with few youth-involved objectives. Only six coalitions reported youth attendance at subcommittee meetings. Of these six coalitions, five were high-achieving coalitions. The other coalition had an extremely low rate of discontinuation (even though not completed, most objectives of this coalition were still active and exhibited numerous qualities associated with objective completion; Reed, Miller, Francisco, and the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, in press). These six coalitions were responsible for the creation of the vast majority (76.92%) of the youth-involved objectives. Thus, high-achieving and low-discontinuation coalitions often incorporated youth in coalition activities at the subcommittee level. High-achieving coalitions were also often lauded for their efforts and held up as exemplar coalitions by those charged with overseeing coalition functioning. In contrast, the C2P national coordinating staff often reminded the low-achieving coalitions to do more to involve youth.

Having a relatively small proportion of youth members was associated with success in completing objectives, if these youth members were highly involved. For example, Site H often had youth involved in action steps, at the subcommittee level, as well as at working group meetings, including meetings at which members discussed mobilization plans. Site E, on the other hand, reported a large proportion of youth members but did not involve them at the committee level, on action steps, or in discussions of mobilization. The data from these two sites suggest we modify our original assertion: Youth membership and their meaningful participation in coalition work (on action steps and at the subcommittee level) was associated with the successful completion of SCOs.

Youth Involvement Indirectly Facilitates Coalition Success

We hypothesized that at the high-success coalitions that engaged youth in multiple capacities (e.g., on action steps, at the subcommittee level, at working group meetings), youth would also indirectly facilitate coalition success. Youth involvement was reported to affect coalition success. Youth members generated excitement among coalition members and community stakeholders. Members enjoyed working with the youth and were excited about their accomplishments. Youth involvement also made coalition members perceive the coalitions were worthwhile; for example, one coalition member expressed that having youth involved and participating at meetings “added legitimacy to the [coalition’s] efforts.” Members at these coalitions came to appreciate youth involvement because it helped them feel “like we’re working with/ alongside our target population as opposed to making decisions for them.” Members were also able to see the impact that they were having on youth, which may have further legitimated their efforts.

Youth involvement helped bring in key community partners. Members described being attracted to the coalitions because of the potential to work with youth. As one member said regarding his decision to work with C2P, “The thing I’m looking most forward to is doing the youth piece.” In one city, youth involved in the intervention attracted the attention of the mayor. The mayor, who had “declared [a] state of emergency around HIV/AIDS prevention,” wanted to make sure “that the youth have more voice” in setting the city’s prevention agenda. In this case, the youth’s work brought key community partners to the table who, as one coalition member said, have “influence on the city level, so it is good to have their name attached to the C2P coalition.” In other cases, influential community constituents supported C2P’s structural change efforts because they could not say “no” to youth or believed in the value of youth community participation. As one coalition member said, youth involvement “add[s] some meat to what we can provide to the young people; the experience that we can provide to the young people.”

Youth also helped in the development of SCOs. At one high-success coalition, coalition leaders trained youth to “identify SCOs that they can bring to the coalition.” Similarly, at another high-success coalition, information garnered from youth involved in the ball community resulted in numerous new objectives and the identification of a new target population. Youth helped inspire objectives by “sharing ideas that may be structural in nature.” Youth members also prompted other coalition members to identify new objectives. For example, after a youth member’s presentation at a work group meeting, the coalition identified new root causes and went on to develop new objectives:

In the past, we had young girls come, but for the first time yesterday they participated in conversation. It was a group conversation and that is why I was so excited, and I think it is because of our youth speaker. Having heard her presentation, it really lends to the other youth who were there to speak up. It was really productive in terms of root causes and solutions.

As the quote above indicates, it was not just youth presence but rather the engaged participation of youth that was “productive” for the coalitions.

In addition to providing feedback on SCOs, youth provided critical insight into youth culture, social networks, and motivations for participating in community-based health initiatives. For example, one high-success coalition asked youth to “serve as formal advisers to the coalition [by] offering strategies for engaging other young people and reaching the target population.” Youth had valuable knowledge to contribute to the coalitions’ efforts, and their feedback, advice, and advocacy enabled the coalitions to move in novel directions.

Discussion

Our analysis suggests that there was wide variation in youth involvement across C2P coalitions. Furthermore, accomplishment of SCOs was associated with successful and meaningful youth engagement. In addition, we found youth indirectly precipitated coalition success by generating excitement about and lending legitimacy to coalition efforts. Youth involvement facilitated member participation and commitment; an interest in working with youth, rather than for youth, was occasionally an impetus for key community partners to join the coalitions. Youth also provided critical insight into youth culture and social networks and identified a need for specific structural changes that would benefit local youth. High-success coalitions more effectively engaged youth than low-success coalitions. Overall, these data imply myriad benefits of youth inclusion and suggest that youth engagement—rather than intermittent involvement or tokenistic participation—was associated with the accomplishment of SCOs.

We can postulate a number of mechanisms that link youth engagement with the attainment of SCOs. Success was associated not solely with the number of youth members, but with the depth of their participation. It is possible that those coalitions that more effectively engaged youth were also better at engaging adults. Clark and colleagues (2010) analyzed the implementation of structural changes within coalitions focused on asthma prevention. They noted that patterns of member participation were associated with success in accomplishing policy and system-level changes such that coalitions with more engaged (rather than intermittent or peripheral) members completed more changes. Members at high-achieving coalitions may have been more motivated, committed, and engaged than those at low-achieving coalitions regardless of the level of youth participation. These successful C2P coalitions may simply be adept at strategically engaging members of all ages and those who have the qualities and skills that are advantageous for structurally based coalitions.

Similarly, the high-success coalitions may simply have been high-functioning coalitions and, therefore, able to dedicate time and resources to youth engagement and to accomplishing SCOs. In our analysis of other factors associated with C2P coalition success (Reed et al., in press) we observed that high-success coalitions evidenced other characteristics associated with effective coalitions (The California Endowment Group, 2011; Zakocs & Edwards, 2006). As developmentally young as these coalitions were during the period under analysis, it is possible that the low-achieving coalitions were still learning to meet the demands of the research protocol and simultaneously mobilize their members. A third possibility is that the objectives youth worked toward may have encountered fewer implementation barriers than those on which they did not participate. C2P coalitions, particularly those focused on young men who have sex with men, often faced contextual and political barriers to the implementation of SCOs (Miller et al., in press). The objectives proposed and enacted by youth may have been more acceptable to community gatekeepers and, thus, more likely achieved. Just as coalition members and community partners admitted having trouble saying “no” to youth, the actors who were targeted as part of the change process may have had trouble saying “no” to youth. Youth’s appeals for the structural changes meant to facilitate their health may have been especially compelling.

None of these explanations credit youth with facilitating coalition success. Rather, these explanations presuppose that youth engagement was an artifact of coalition functioning. Our data suggest that youth’s contributions were more than merely side effects of solid coalition functioning. Youth’s insights broadened the ways in which adult members thought of HIV-preventive structural changes and deepened their understanding of youth subpopula-tions. Through youth’s making presentations at and participating in meetings, members came to rethink their priorities or develop novel structural changes in response to youth’s concerns. Youth expanded the coalitions’ strategic focus.

Zakocs and Edwards (2006) examined indicators of effectiveness across the coalition literature and identified coalition-building factors associated with effectiveness. Our data allude to young people’s influence on a number of these coalition-building factors (e.g., active participation, diverse membership, member collaboration). Youth inclusion diversified coalition membership, and coalition members discussed ways in which youth enhanced member collaboration. In turn, youth engagement may have increased member satisfaction and participation, both of which are factors associated with coalition efficiency and effectiveness. Research on youth participatory action suggests that as youth engage in problem identification, solution design, and decision making, their perceived legitimacy increases (Kohfeldt et al., 2011). When youth have the opportunity for authentic participation, adults see them as capable change agents. When adults validate youth’s ideas, youth come to see their own value. Members may be more likely to sustain their participation when they are engaged in meaningful group problem analysis processes, and youth may enrich these discussions in ways that contribute to sustained participation.

The current study has several key limitations. The interview data we had available were limited to adult coalition members and staff; we do not have data from youth members from which to draw conclusions about their participation. We might glean a more complete understanding of youth engagement were we to have the perspective of the youth members. Despite the lack of data provided by youth, the interview data and data from other sources were convergent. Given the fact that these interviews were conducted by people unaffiliated with and independent of the coalitions and that respondents represent the viewpoints of numerous coalition members at each site, we have confidence that these data provide a credible and adequate representation of the role youth played in the early successes of these coalitions. We would note, however, that we believe that youth’s voices in a study on youth-focused coalitions provides the most intimate perspective on their experiences. We endorse calls for youth inclusion in health promotion projects (Prilleltensky, 2010; Wong et al., 2010) and urge that youth be asked to speak directly to their own experiences in future research on youth-focused coalitions.

Second, we recognize the potential for counts of youth membership to be problematic and not a true measure of youth involvement. An unknown number of youth who on membership surveys appear to be members may only have been peripherally involved members of the coalition (this is probably equally true of adults). With this possibility in mind, when we examined youth engagement, we also took into consideration the records of youth participation on action steps and youth attendance at committee meetings. Taken together, the use of multiple sources and multiple data types provides us with a more credible picture of how youth were involved and to what extent they contributed to coalition achievement. However, as a secondary analysis of records kept by the coalitions, we were limited by what data were available. As others have noted, secondary analyses of participation are often limited by the type of attendance information collected (Roth, Malone, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010). Ideally, youth engagement should be measured in terms of the intensity, breadth, and duration of their involvement (Roth et al., 2010). In addition, the youth–adult partnership literature indicates we might assess the degree of youth interaction with adults (Wong et al., 2010).

Third, we limited our analysis to the first 2 years of coalition mobilization, a period that may not represent the nature of youth’s current engagement in and impact on the coalitions. On one hand, it is likely that the coalitions’ relationships with youth have deepened over time, as the coalitions have become mature, well-established entities. On the other hand, the coalitions no longer offer the two CDC-endorsed interventions, closing a direct avenue for youth involvement. We could not identify precisely the role of these interventions in the coalitions’ efforts to attract and maintain youth members, so we cannot determine how important the discontinuation of these programs on youth engagement may be. However, given the increasing emphasis on pluralistic approaches to HIV prevention (Gupta et al., 2008; Piot et al., 2008; Wohlfeiler & Ellen, 2007) and the number of coalitions for which these programs provided the only means of direct youth engagement, we think it probable that we captured a unique period of youth engagement for these coalitions.

Last, as implied in this discussion, our analysis precludes us from drawing firm conclusions about the particular mechanisms that link youth engagement with the coalitions’ implementation of SCOs. We recognize there are a variety of factors that influence coalition maintenance and achievement; elsewhere, we have examined how particular aspects of the SCOs (Reed et al., in press) and the target populations (Miller et al., in press) were related to achievement. We have no delusions that youth engagement was the only, or even the main, factor that influenced coalition success.

Conclusion

Community members are rarely involved in the design, implementation, or evaluation of HIV-preventive structural interventions (Shriver, Everett, & Morin, 2000). Yet research on community-based interventions suggests that ensuring value congruence and relevance enhances intervention effectiveness and sustainability (Altman, 1995; Miller & Shinn, 2005). One practical impetus for involving community members, and particularly a diverse array of target population members, in collaborative processes to design structurally focused interventions is to ensure such congruence and relevance. As is the case with other community-based interventions, support for structural changes may increase when the people whom the intervention is likely to affect are involved in design and implementation.

The success of many of the C2P coalitions in attracting and maintaining youth members shows that structurally focused coalitions can overcome the barriers to youth participation and that doing so may be advantageous for coalition health and effectiveness. It is up to coalition leaders to ensure youth inclusion and to be cognizant of the many barriers to youth engagement in decision-making processes (The California Endowment Group, 2011). Given the barriers to youth engagement in community health promotion projects, the individual-level growth that may accrue to adults and youth from such involvement, and the potential for youth engagement to aid coalitions in framing acceptable and attainable objectives, youth engagement may itself represent a structural change that positively alters the way youth-focused interventions are conducted.

Acknowledgments

The study was scientifically reviewed by the ATN’s Community and Prevention Leadership Group. Network scientific and logistical support was provide by the ATN Coordinating Center (C. Wilson, C. Partlow), at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The ATN 079 Protocol Team members are Vincent Francisco (University of North Carolina–Greensboro), Robin Lin Miller (Michigan State University), Jonathan Ellen (John Hopkins University), Peter Freeman (Children’s Memorial Hospital), Lawrence B. Friedman (University of Miami School of Medicine), Grisel-Robles Schrader (University of California–San Francisco), Jessica Roy (Children’s Diagnostic and Treatment Center), Nancy Willard (Johns Hopkins University), and Jennifer Huang (Westat, Inc.). Research assistantship was provided by Sarah Reed (Michigan State University), Ella Dolan (Michigan State University), and Greer Cook (University of North Carolina–Greensboro).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) is funded by Grants No. 2 U01 HD040533 and No.2 U01 HD040474 from the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (B. Kapogiannis, MD), with supplemental funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (N. Borek, PhD), National Institute on Mental Health (P. Brouwers, PhD), and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K Bryant, PhD).

Biographies

Sarah J. Reed, MA, is a doctoral student in the Ecological-Community Psychology program at Michigan State University. Her research interests include structural approaches to HIV prevention and the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents.

Robin Lin Miller, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Psychology at Michigan State University. Dr. Miller’s research program focuses on the design and delivery of effective community-based HIV prevention services, with a particular emphasis on populations at highest risk in the nation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Altman DM. Sustaining interventions in community systems: On the relationship between researchers and communities. Health Psychology. 1995;14:526–536. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HS. Becoming a marihuana user. American Journal of Sociology. 1953;59:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KS, Bray SJ, Merson MH. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14:S11–S21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KS, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C, Hargreaves J, Strange V, Pronyk P, Porter J. Should structural interventions be evaluated using RCTs? The case of HIV prevention. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63:1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WF. Disadvantaged persons’ participation in health promotion projects: Some structural dimensions. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:1551–1564. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camino L, Zeldin S. From periphery to center: Pathways for youth civic engagement in the day-to-day life of communities. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:213–220. [Google Scholar]

- CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects Research Group. Community-level HIV intervention in five cities: Final outcome data from the AIDS community demonstration projects. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(3):336–345. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkoway B, Richards-Schuster K. Lifting new voices for socially just communities. Community Youth Development. 2001;2:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape KS, Willard N, Sanchez K, Straub DM, Ochoa TN, Howell K the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Mobilizing communities around HIV prevention youth: How three coalitions applied key strategies to bring about structural changes. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22:15–27. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark NM, Lachance L, Doctor LJ, Gilmore L, Kelly C, Krieger J, Wilkin M. Policy and system change and community coalitions: Outcomes from Allies Against Asthma. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(5):904–912. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallape F. Urban children: A challenge and an opportunity. Childhood. 1996;3:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson F. Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In: Wittrock MC, editor. Handbook of research on teaching. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1986. pp. 119–161. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett SB, Francisco VT, Hyra D, Paine-Andrews A, Schultz JA, Russos S. Building healthy communities. In: Tarlov A, StPeter R, editors. The society and population health reader: A state and community perspective. New York, NY: New Press; 2000. pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett SB, Francisco VT, Paine-Andrews A. Working together for healthier communities. Public Health Reports. 2000;115:174–179. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn JL, Checkoway B. Young people as competent community builders: A challenge for social work. Social Work. 1998;43:335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco VT, Fawcett SB, Schultz JA, Paine-Andrews A. A model of health promotion and community development. In: Balcazar FB, Montero M, Newbrough JR, editors. Health promotion in the Americas: Theory and practice. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2000. pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. HIV prevention 4: Structural approaches to HIV prevention. The Lancet. 2008;372(9637):764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurstein P, Lovato C, Ross S. Youth participation in planning: Strategies for social action. Canadian Journal of Urban Research. 2003;12:249–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment project: A community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(8):1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohfeldt D, Chhun L, Grace S, Langhout RD. Youth empowerment in context: Exploring tensions in school-based yPAR. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:28–45. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9376-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubisch AC, Auspos P, Brown P, Dewar T. Voices from the field III: Lessons and challenged from two decades of community change efforts. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL, Reed SJ, Francisco VT, Ellen JM. Conflict transformation, stigma, and HIV-preventive structural change. American Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9465-7. the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL, Reed SJ, Fransisco VT. Accomplishing structural change: Identifying intermediate indicators of success. American Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9544-4. the Adolescent Medical Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL, Shinn M. Learning from communities: Overcoming difficulties in dissemination of prevention and promotion efforts. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35:169–183. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-3395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Prilleltensky I, MacGillivary H. Building value-based partnerships: Toward solidarity with oppressed groups. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:649–677. doi: 10.1023/A:1010406400101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piot P, Bartos M, Larson H, Zewdie D, Mane P. Coming to terms with complexity: A call to action for HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:845–859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JL, Tiffany JS. Engaging youth in participatory research and evaluation. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2006;12:79–87. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200611001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky I. Child wellness and social inclusion: Values for action. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;46:238–249. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo 8 [computer software] Melbourne, Australia: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reed SJ, Miller RL, Francisco VT. Programmatic capacity and HIV structural change interventions: Influences on coalitions’ success and efficiency in accomplishing intermediate outcomes. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.660123. the Adolescent Medical Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JL, Malone LM, Brooks-Gunn J. Does the amount of participation in afterschool programs relate to developmental outcomes: A review of the literature. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45:310–324. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothrum-Borus MJ. Expanding the range of interventions to reduce HIV among adolescents. AIDS. 2000;14:33–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriver MD, Everett C, Morin SF. Structural interventions to encourage primary HIV prevention among people living with HIV. AIDS. 2000;14:57–62. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML. Mixing and matching: Methods and models. In: Greene JC, Caracelli VJ, editors. Advances in mixed-method evaluation: The challenges and benefits of integrating diverse paradigms. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1997. pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- The California Endowment Group. What makes an effective coalition? Evidence-based indicators of success. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Willard N, Chutuape K, Stines S, Ellen J. Bridging the gap between individual level risk for HIV and structural determinants: Using root cause analysis in strategic planning. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.660122. the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfeiler D, Ellen JM. The limits of behavioral interventions for HIV prevention. In: Cohen L, Chehimi S, Chavez V, editors. Prevention is primary: Strategies for community well-being. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007. pp. 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wong NT, Zimmerman MA, Parker EA. A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;46:100–114. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakocs RC, Edwards EM. What explains community coalition effectiveness? A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(4):351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziff M, Harper G, Chutuape K, Deeds BG, Futterman D, Ellen J the Adolescent Trial Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Laying the foundation for Connect to Protect®: A multi-site community mobilization intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS incidence and prevalence among urban youth. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:506–522. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman K, Erbstein N. Promising practices: Youth empowerment evaluation (Harvard Family Research Project: Evaluation Exchange, V: 1) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University; 1999. [Google Scholar]