Science is valued by society because the application of scientific knowledge helps to satisfy many basic human needs and improve living standards. Finding a cure for cancer and a clean form of energy are just two topical examples. Similarly, science is often justified to the public as driving economic growth, which is seen as a return-on-investment for public funding. During the past few decades, however, another goal of science has emerged: to find a way to rationally use natural resources to guarantee their continuity and the continuity of humanity itself; an endeavour that is currently referred to as “sustainability”.

Scientists often justify their work using these and similar arguments—currently linked to personal health and longer life expectancies, technological advancement, economic profits, and/or sustainability—in order to secure funding and gain social acceptance. They point out that most of the tools, technologies and medicines we use today are products or by-products of research, from pens to rockets and from aspirin to organ transplantation. This progressive application of scientific knowledge is captured in Isaac Asimov’s book, Chronology of science and discovery, which beautifully describes how science has shaped the world, from the discovery of fire until the 20th century.

However, there is another application of science that has been largely ignored, but that has enormous potential to address the challenges facing humanity in the present day education. It is time to seriously consider how science and research can contribute to education at all levels of society; not just to engage more people in research and teach them about scientific knowledge, but crucially to provide them with a basic understanding of how science has shaped the world and human civilisation. Education could become the most important application of science in the next decades.

“It is time to seriously consider how science and research can contribute to education at all levels of society…”

More and better education of citizens would also enable informed debate and decision-making about the fair and sustainable application of new technologies, which would help to address problems such as social inequality and the misuse of scientific discoveries. For example, an individual might perceive an increase in welfare and life expectancy as a positive goal and would not consider the current problems of inequality relating to food supply and health resources.

However, taking the view that science education should address how we apply scientific knowledge to improve the human condition raises the question of whether science research should be entirely at the service of human needs, or whether scientists should retain the freedom to pursue knowledge for its own sake—albeit with a view to eventual application. This question has been hotly debated since the publication of British physicist John D. Bernal’s book, The Social Function of Science, in 1939. Bernal argued that science should contribute to satisfy the material needs of ordinary human life and that it should be centrally controlled by the state to maximise its utility—he was heavily influenced by Marxist thought. The zoologist John R. Baker criticised this “Bernalistic” view, defending a “liberal” conception of science according to which “the advancement of knowledge by scientific research has a value as an end in itself”. This approach has been called the “free-science” approach.

The modern, utilitarian approach has attempted to coerce an explicit socio-political and economic manifestation of science. Perhaps the most recent and striking example of this is the shift in European research policy under the so-called Horizon 2020 or H2020 funding framework. This medium-term programme (2014-2020) is defined as a “financial instrument implementing the Innovation Union, a Europe 2020 flagship initiative aimed at securing Europe’s global competitiveness” (http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/index_en.htm). This is a common view of science and technology in the so-called developed world, but what is notable in the case of the H2020 programme is that economic arguments are placed explicitly ahead of all other reasons. Europe could be in danger of taking a step backwards in its compulsion to become an economic world leader at any cost.

“Europe could be in danger of taking a step backwards in its compulsion to become an economic world leader at any cost.”

For comparison, the US National Science Foundation declares that its mission is to “promote the progress of science; to advance the national health, prosperity and welfare; to secure the national defence; and for other purposes” (http://www.nsf.gov/about/glance.jsp). The Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) states that it “promotes creation of intellect, sharing of intellect with society, and establishment of its infrastructure in an integrated manner and supports generation of innovation” (http://www.jst.go.jp/EN/about/mission.html). In his President’s Message, Michiharu Nakamura stated that, “Japan seeks to create new value based on innovative science and technology and to contribute to the sustained development of human society ensuring Japan’s competitiveness” 1. The difference between these declarations and the European H2020 programme is that the H2020 programme explicitly prioritises economic competitiveness and economic growth, while the NIH and JST put their devotion to knowledge, intellect, and the improvement of society up front. Curiously, the H2020 programme’s concept of science as a capitalist tool is analogous to the “Bernalistic” approach and contradicts the “liberal” view that “science can only flourish and therefore can only confer the maximum cultural and practical benefits on society when research is conducted in an atmosphere of freedom” 2. By way of example, the discovery of laser emissions in 1960 was a strictly scientific venture to demonstrate a physical principle predicted by Einstein in 1917. The laser was considered useless at that time as an “invention in the search for a job”.

“… we need to educate the educators, and consequently to adopt adequate science curricula at university education departments.”

The mercantilisation of research is, explicitly or not, based on the simplistic idea that economic growth leads to increased quality of life. However, some leading economists think that using general economic indicators, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), to measure social well-being and happiness is flawed. For example, Robert Costanza, of the Australian National University, and several collaborators published a paper in Nature recently in which they announce the “dethroning of GDP” and its replacement by more appropriate indicators that consider both economic growth and “a high quality of life that is equitably shared and sustainable” 3.

If the utilitarian view of science as an economic tool prevails, basic research will suffer. Dismantling the current science research infrastructure, which has taken centuries to build and is based on free enquiry, would have catastrophic consequences for humanity. The research community needs to convince political and scientific managers of the danger of this course. Given that a recent Eurobarometer survey found significant support among the European public for scientists to be “free to carry out the research they wish, provided they respect ethical standards” (73% of respondents agreed with this statement; http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_224_report_en.pdf), it seems that a campaign to support the current free-science system, funded with public budgets, would likely be popular.

The US NSF declaration contains a word that is rarely mentioned when dealing with scientific applications: education. Indeed, a glance at the textbooks used by children is enough to show how far scientific knowledge has advanced in a few generations, and how these advances have been transferred to education. A classic example is molecular biology; a discipline that was virtually absent from school textbooks a couple of generations ago. The deliberate and consistent addition of new scientific knowledge to enhance education might seem an obvious application of science, but it is often ignored. This piecemeal approach is disastrous for science education, so the application of science in education should be emphasised and resourced properly for two reasons: first, because education has been unequivocally recognised as a human right, and second, because the medical, technological and environmental applications of science require qualified professionals who acquire their skills through formal education. Therefore, education is a paramount scientific application.

“The deliberate and consistent addition of new scientific knowledge to enhance education might seem an obvious application of science, but it is often ignored.”

In a more general sense, education serves to maintain the identity of human culture, which is based on our accumulated knowledge, and to improve the general cultural level of society. According to Stuart Jordan, a retired senior staff scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and currently president of the Institute for Science and Human Values, widespread ignorance and superstition remain “major obstacles to progress to a more humanistic world” 4 in which prosperity, security, justice, good health and access to culture are equally accessible to all humans. He argues that the proliferation of the undesirable consequences of scientific knowledge—such as overpopulation, social inequality, nuclear arms and global climate change—resulted from the abandonment of the key principle of the Enlightenment: the use of reason under a humanistic framework.

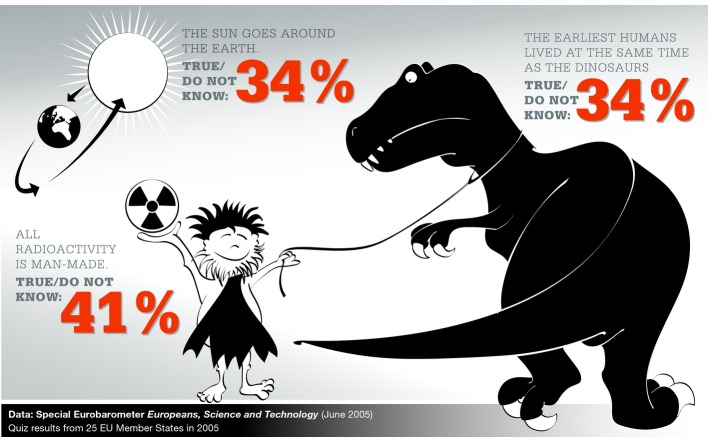

When discussing education, we should therefore consider not only those who have no access to basic education, but also a considerable fraction of the populations of developed countries who have no recent science education. The Eurobarometer survey mentioned provides a striking argument: On average, only the half of the surveyed Europeans knew that electrons are smaller than atoms; almost a third believed that the Sun goes around the Earth, and nearly a quarter of them affirmed that earliest humans coexisted with dinosaurs (http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_224_report_en.pdf). Another type of passive ignorance that is on the increase among the public of industrialised countries, especially among young people, is an indifference to socio-political affairs beyond their own individual and immediate well-being.

Ignorance may have a relevant influence on politics in democracies because ignorant people are more easily manipulated, or because their votes may depend on irrelevant details, such as a candidate’s physical appearance or performance in public debates. A democracy should be based on an informed society. Education sensu lato—including both formal learning and cultural education—is therefore crucial for developing personal freedom of thought and free will, which will lead to adequate representation and better government 5.

To improve the cultural level of human societies is a long-term venture in which science will need to play a critical role. We first need to accept that scientific reasoning is intimately linked to human nature: Humanity did not explicitly adopt science as the preferred tool for acquiring knowledge after choosing among a set of possibilities; we simply used our own mental functioning to explain the world. If reason is a universal human feature, any knowledge can be transmitted and understood by everyone without the need for alien constraints, not unlike art or music.

Moreover, science has demonstrated that it is a supreme mechanism to explain the world, to solve problems and to fulfil human needs. A fundamental condition of science is its dynamic nature: the constant revision and re-evaluation of the existing knowledge. Every scientific theory is always under scrutiny and questioned whenever new evidence seems to challenge its validity. No other knowledge system has demonstrated this capacity, and even, the defenders of faith-based systems are common users of medical services and technological facilities that have emerged from scientific knowledge.

For these reasons, formal education from primary school to high school should therefore place a much larger emphasis on teaching young people how science has shaped and advanced human culture and well-being, but also that science flourishes best when scientists are left free to apply human reason to understand the world. This also means that we need to educate the educators and consequently to adopt adequate science curricula at university education departments. Scientists themselves must get more involved both in schools and universities.

“Dismantling the current science research infrastructure, which has taken centuries to build and is based on free enquiry, would have catastrophic consequences for humanity.”

But scientists will also have to get more engaged with society in general. The improvement of human culture and society relies on more diffuse structural and functional patterns. In the case of science, its diffusion to the general public is commonly called the popularisation of science and can involve scientists themselves, rather than journalists and other communicators. In this endeavour, scientists should be actively and massively involved. Scientists—especially those working in public institutions—should make a greater effort to communicate to society what science is and what is not; how is it done; what are its main results; and what are they useful for. This would be the best way of demystifying science and scientists and upgrading society’s scientific literacy.

In summary, putting a stronger emphasis on formal science education and on raising the general cultural level of society should lead to a more enlightened knowledge-based society—as opposed to the H2020 vision of a knowledge-based economy—that is less susceptible to dogmatic moral systems. Scientists should still use the other arguments—technological progress, improved health and well-being and economic gains—to justify their work, but better education would provide the additional support needed to convince citizens about the usefulness of science beyond its economic value. Science is not only necessary for humanity to thrive socially, environmentally and economically in both the short and the long term, but it is also the best tool available to satisfy the fundamental human thirst for knowledge, as well as to maintain and enhance the human cultural heritage, which is knowledge-based by definition.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Japan Science and Technology Agency. 2013. Overview of JST program and organisation 2013–2014 http://www.jst.go.jp/EN/JST_Brochure_2013.pdf ). Last accessed: March 20, 2014.

- McGucken W. On freedom and planning in science: the Society for Freedom in Science, 1940–46. Minerva. 1978;16:42–72. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R, Kubiszewski I, Giovannini E, Lovins H, McGlade J, Pickett KE. Time to leave GDP behind. Nature. 2014;505:283–285. doi: 10.1038/505283a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S. The Enlightenment Vision. Science, Reason and the Promise of a Better Future. Amherst: Promethous Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rull V. Conservation, human values and democracy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:17–20. doi: 10.1002/embr.201337942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]