Abstract

Fibroblasts can be directly reprogrammed into cardiomyocyte-like cells (iCMs) by overexpression of cardiac transcription factors or microRNAs. However, induction of functional cardiomyocytes is inefficient, and molecular mechanisms of direct reprogramming remain undefined. Here, we demonstrate that addition of miR-133a (miR-133) to Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 (GMT) or GMT plus Mesp1 and Myocd improved cardiac reprogramming from mouse or human fibroblasts by directly repressing Snai1, a master regulator of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. MiR-133 overexpression with GMT generated sevenfold more beating iCMs from mouse embryonic fibroblasts and shortened the duration to induce beating cells from 30 to 10 days, compared to GMT alone. Snai1 knockdown suppressed fibroblast genes, upregulated cardiac gene expression, and induced more contracting iCMs with GMT transduction, recapitulating the effects of miR-133 overexpression. In contrast, overexpression of Snai1 in GMT/miR-133-transduced cells maintained fibroblast signatures and inhibited generation of beating iCMs. MiR-133-mediated Snai1 repression was also critical for cardiac reprogramming in adult mouse and human cardiac fibroblasts. Thus, silencing fibroblast signatures, mediated by miR-133/Snai1, is a key molecular roadblock during cardiac reprogramming.

Keywords: cardiomyocyte, microRNA, reprogramming, Snai1, transcription factor

Introduction

Direct reprogramming of mature cells from one lineage to another without passing through a stem cell state has emerged as a new strategy for generating cell types of interest and may hold great potential for regenerative medicine. Thus far, neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, blood precursor cells, and neural progenitors were successfully induced from fibroblasts by overexpression of lineage-specific transcription factor (Ieda et al, 2010; Szabo et al, 2010; Vierbuchen et al, 2010; Sekiya & Suzuki, 2011; Han et al, 2012; Wada et al, 2013). Suppression of the starting-cell signature is a recognized characteristic of cell fate conversion, although the molecular mechanisms underlying this process and its importance during direct reprogramming remain poorly understood (Marro et al, 2011; Muraoka & Ieda, 2014).

It was reported that induced cardiomyocyte-like cells (iCMs) can be directly generated from mouse fibroblasts by the combination of transcription factors, Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 (GMT), GMT plus Hand2 (GHMT), or Mef2c, Myocd, and Tbx5 in vitro (Ieda et al, 2010; Protze et al, 2012; Song et al, 2012). Recently, we and others reported that iCMs can be directly generated from human fibroblasts by overexpression of GMT plus Mesp1 and Myocd (GMTMM) or other combinations of reprogramming factors (Fu et al, 2013; Nam et al, 2013; Wada et al, 2013). However, induction of functional cardiomyocytes in vitro was inefficient and slow, possibly hindering our investigations of the molecular events during cardiac reprogramming (Chen et al, 2012; Srivastava & Ieda, 2012; Addis & Epstein, 2013). We and others also showed that endogenous mouse cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) can be converted into iCMs in vivo by gene transfer of GMT or GHMT (Inagawa et al, 2012; Qian et al, 2012; Song et al, 2012). The in vivo iCMs were more fully reprogrammed than their cultured counterparts, suggesting the presence of undefined factors that enhance reprogramming. Identification of such potent reprogramming factors could provide new insights into the mechanisms of cardiac reprogramming.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) can suppress the expression of hundreds of genes, primarily through binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, and thus play important roles in cell fate decisions. Embryonic stem cell-specific miRNAs enhanced the reprogramming efficiency of fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs; Judson et al, 2009; Subramanyam et al, 2011), and more recently, Jayawardena et al (2012) reported that a combination of muscle-specific miRNAs (miR-1, 133, 208, 499) alone reprogrammed neonatal mouse CFs into cardiomyocyte-like cells (Jayawardena et al, 2012). However, it remains unclear whether other types of fibroblasts could also be converted into iCMs by miRNAs. Moreover, the global transcriptional changes and mechanistic basis of cardiac reprogramming by miRNAs remain unknown.

Here, we show that miR-133a (miR-133) promoted cardiac reprogramming in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), adult mouse cardiac fibroblasts, and human cardiac fibroblasts (HCFs) in combination with GMT or GMTMM transduction. We found that miR-133 suppressed the fibroblast programs by directly repressing Snai1, a master regulator of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and thereby promoted cardiac reprogramming.

Results

MiR-133 promotes cardiac induction in MEFs in combination with Gata4/Mef2c/Tbx5

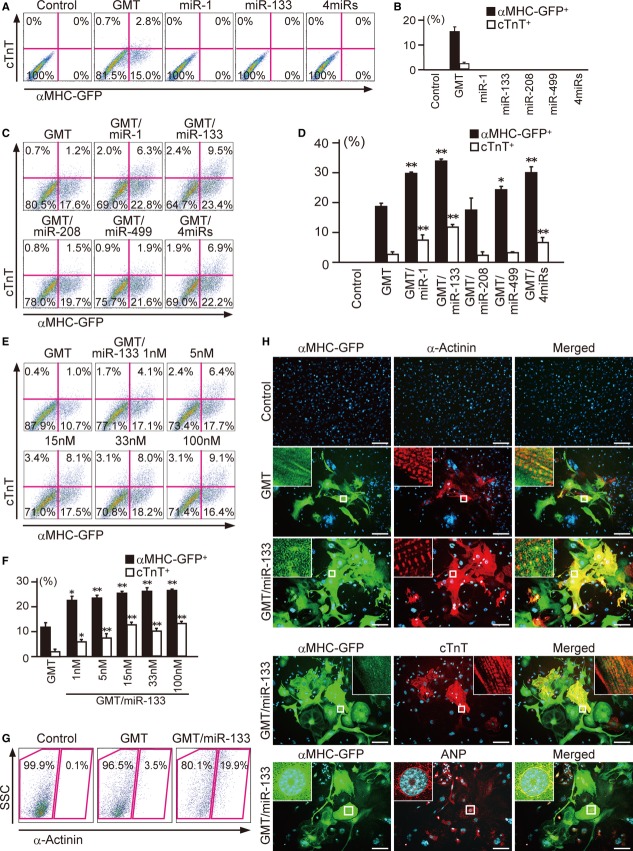

We first investigated whether miR-1, 133, 208, and 499 alone, shown previously to induce cardiac reprogramming in neonatal mouse CFs, could also generate iCMs from MEFs, which have a distinct embryonic origin compared to CFs. We used MEFs from αMHC promoter-driven EGFP transgenic mice (αMHC-GFP), in which no cardiomyocytes or cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) were detected by immunofluorescence, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses (Supplementary Fig S1A–E; Ieda et al, 2010). The transfection efficiency by miRNA mimics was 97%, but none of the miRNA mimics induced αMHC-GFP or cardiac troponin T (cTnT) expression in MEFs when used individually or as a pool (four miRs) after 1 week of transfection (Fig1A and B, Supplementary Fig S1F and G; Jayawardena et al, 2012). In contrast, GMT transduction induced αMHC-GFP and cTnT expression in MEFs, similar to that induced in CFs (Fig1A and B, Supplementary Fig S1H; Ieda et al, 2010).

Figure 1. MiR-133 promotes Gata4/Mef2c/Tbx5-induced cardiac reprogramming.

A, B FACS analyses for αMHC-GFP+ and cTnT+ cells 1 week after GMT transduction or miRNA transfection. Quantitative data are shown in (B) (n = 3).

C, D FACS analyses for αMHC-GFP+ and cTnT+ cells 1 week after GMT and miRNA transduction. Quantitative data are shown in (D) (n = 3).

E, F Dose dependency of miR-133-mediated cardiac induction with GMT. Quantitative data are shown in (F) (n = 3).

G FACS analyses for α-actinin+ cells 1 week after transduction.

H Immunocytochemisty for αMHC-GFP, α-actinin, and DAPI. GMT/miR-133 induced abundant αMHC-GFP and α-actinin expression 2 weeks after transduction. High-magnification views in insets show sarcomeric organization. GMT/miR-133 induced cTnT and ANP expression 2 weeks after transduction. Insets are high-magnification views.

Data information: All data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus relevant control. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

Next, we introduced these miRNAs along with GMT into MEFs to investigate whether miRNAs promote cardiac reprogramming. We found that the number of αMHC-GFP+ cells activating a cardiac reporter was increased by approximately twofold and that the number of cTnT+ cells expressing the endogenous cardiac-specific gene was increased by approximately sixfold by the addition of miR-1, 133, or four miRs to the GMT transduction (Fig1C and D). In contrast, addition of miR-208 or miR-499 had no substantial effects, suggesting that the miRNA effects were specific. Among them, miR-133 mimics showed the greatest effects, and thereby, we used miR-133 in subsequent studies. We determined the dose dependency of miR-133-mediated cardiac induction and found that 15 nM of miR-133 was sufficient (Fig1E and F). Addition of JAK inhibitor I, which reported to increase cardiac induction, to GMT/miR-133 did not augment the reprogramming efficiency (Supplementary Fig S1I and J; Jayawardena et al, 2012). FACS analyses demonstrated that expression of another cardiac marker, sarcomeric α-actinin (α-actinin), was also increased by addition of miR-133 to GMT (Fig1G). Immunostaining for cardiac markers, including α-actinin, cTnT, and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), demonstrated that GMT/miR-133 strongly enhanced cardiac protein expression, and the iCMs had well-defined sarcomeric structures, similar to neonatal cardiomyocytes (Fig1H and I, Supplementary Fig S1B). Thus, miR-133 improved cardiac induction from MEFs in combination with GMT transduction.

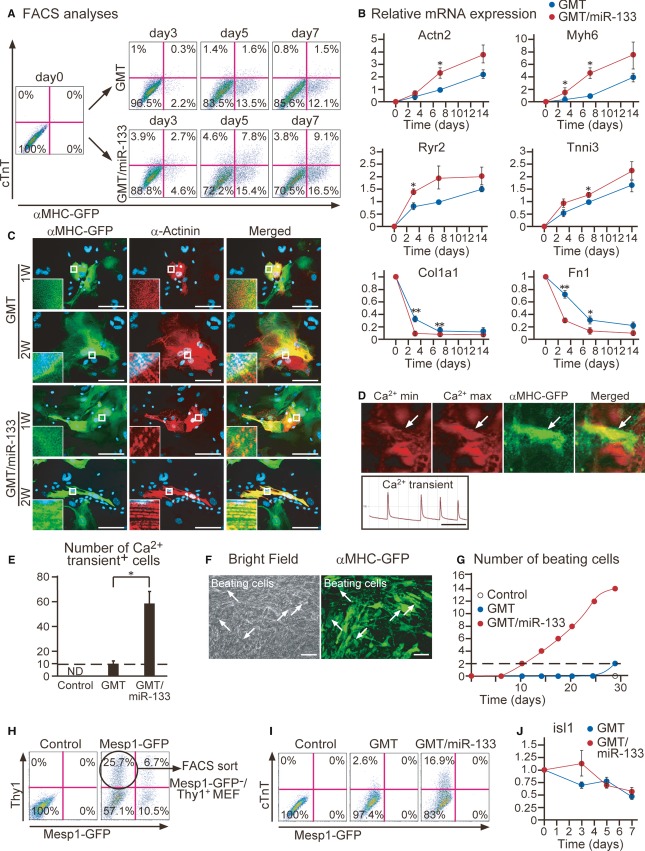

MiR-133 rapidly and efficiently induces functional cardiomyocyte-like cells from MEFs in combination with Gata4/Mef2c/Tbx5

To investigate the effects of miR-133 on cardiac reprogramming in more detail, we next compared the time courses of reprogramming between GMT and GMT/miR-133 induction. FACS analyses revealed that GMT/miR-133 induced significantly more α-MHC-GFP and cTnT expression in the MEFs by as early as day 3 than GMT alone, with the numbers peaking at day 7, and remaining higher even at 4 weeks after transduction (Fig2A, Supplementary Fig S2A). The iCMs were less proliferative than non-converted fibroblasts and decreased in percentage relative to the total number of cells over time in culture. qRT-PCR demonstrated that the expression of cardiac genes, Actn2 (sarcomeric α-actinin), Myh6 (α-myosin heavy chain), Ryr2 (ryanodine receptor 2), and Tnni3 (cardiac troponin I), was upregulated, while the expression of fibroblast genes, Col1a1 (collagen 1a1) and Fn1 (fibronectin 1), was significantly downregulated from day 3 in the FACS-sorted α-MHC-GFP+ cells induced with GMT/miR-133 (Fig2B). Non-sorted samples also revealed comparable results (Supplementary Fig S2B). Immunocytochemistry demonstrated that the GMT/miR-133-iCMs showed sarcomeric structures after 7 days of infection, which normally takes 2 weeks with GMT alone (Fig2C). qRT-PCR and immunostaining for the genes specific to nodal, atrial, and ventricular myocytes revealed that most iCMs were atrial-type myocytes with either transduction (Supplementary Fig S2C and D). Functionally, a subset of MEF-derived iCMs showed spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, and sixfold more cells exhibited Ca2+ flux with GMT/miR-133 induction than with GMT alone (Fig2D and E, Supplementary Movie S1). Notably, cell contraction started from 10 days after GMT/miR-133 transduction, which generally took 4 weeks with GMT. The number of beating cells increased over time, with sevenfold more contractile cells achieved compared to using GMT alone (Fig 2F and G, Supplementary Fig S2E, and Supplementary Movies S2 and S3). We did not observe any beating cells in untreated MEF cultures, excluding the possibility of cardiomyocyte contamination. EdU incorporation assays revealed that the increase in beating iCMs with GMT/miR-133 transduction was not due to cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig S2F and G). These results suggest that miR-133 promoted the speed and efficiency of cardiac reprogramming in combination with GMT.

Figure 2. MiR-133 enhances generation of functional iCMs.

A Time course of αMHC-GFP and cTnT expression by GMT or GMT/miR-133 transduction in MEFs. See also Supplementary Fig S2A.

B qRT-PCR for cardiac and fibroblast gene expression in αMHC-GFP+ cells by GMT or GMT/miR-133 transduction (n = 4). Data were normalized against the values of GMT-iCMs at day 7 (Actn2,Myh6,Ryr2,Tnni3) or MEFs at day 0 (Col1a1,Fn1). See also Supplementary Fig S2B.

C GMT/miR-133 induced expression of α-actinin with sarcomeric organization 1 week after transduction.

D, E Spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations observed in MEF-derived iCMs (arrows) after 4 weeks of induction, corresponding to Supplementary Movie S1. Rhod-3 images at Ca2+ max and min are shown in the upper panels and Rhod-3 intensity trace is shown in the lower panel (D). Total number of Ca2+ oscillation+ cells in 10 randomly selected fields per well is shown in (E) (n = 3).

F Spontaneously beating GMT/miR-133 iCMs 4 weeks after transduction (arrows), corresponding to Supplementary Movie S2. See also Supplementary Fig S2E and Movie S3.

G Number of spontaneously beating cells in each well after transduction of mock, GMT, or GMT/miR-133 at the indicated time.

H, I Mesp1-GFP−/Thy1+ MEFs were sorted and transduced with GMT or GMT/miR-133 (H). All cTnT+ cells were negative for Mesp1-GFP (I).

J qRT-PCR for isl1 expression in the cells transduced with GMT or GMT/miR-133 (n = 3).

Data information: All data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus relevant control. Scale bars: 100 μm (C, F); 5 s (D).

Mesp1-GFP mice, in which the progeny of multipotent CPCs can be traced by fluorescence, were used to determine the route of cardiac reprogramming (Saga et al, 1999; Kawamoto et al, 2000). We isolated Mesp1-GFP–/Thy1+ MEFs by FACS and transduced the cells with GMT/miR-133 (Fig2H). The resulting cTnT+ cells did not express GFP, suggesting that the iCMs were generated from MEFs without passing through a mitotic Mesp1+-CPC state (Fig2I). Moreover, a later CPC marker, isl1, was not induced by GMT/miR-133 during reprogramming (Fig2J). These results indicated that the iCMs were directly generated from fibroblasts by GMT/miR-133.

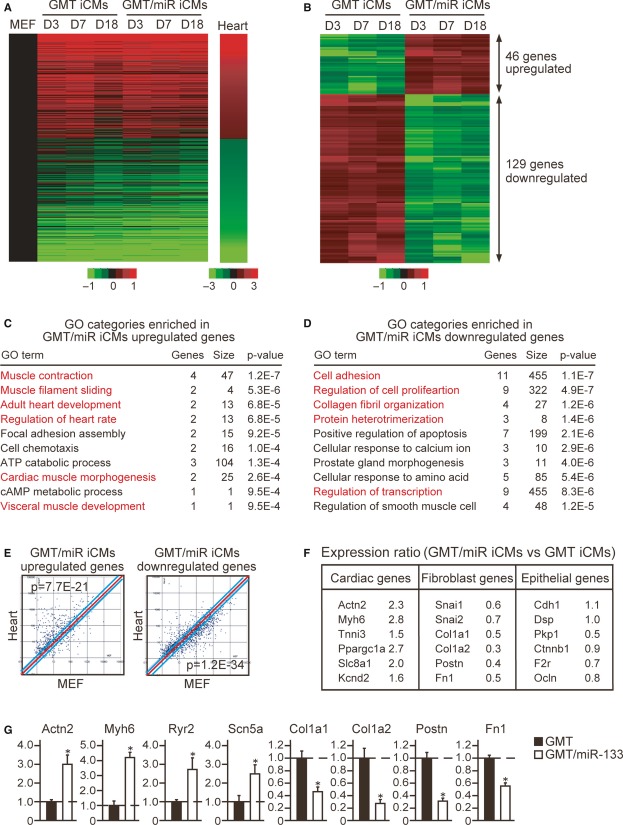

MiR-133 suppresses fibroblast signatures in concert with cardiac gene activation

Next, to investigate the mechanistic basis of miR-133-mediated cardiac reprogramming, we analyzed the global gene expression profiles of iCMs induced with GMT or GMT/miR-133 by microarray. We FACS-sorted α-MHC-GFP+ cells at 3, 7, and 18 days after transduction, before and after the GMT/miR-133-transduced cells started contractions, and compared the differential gene expressions between MEFs and hearts. Although the vast majority of α-MHC-GFP+ cells were only partially reprogrammed iCMs, with few capable of beating, the heatmap image of microarray data revealed a shift in the global gene expression patterns of the iCMs from a MEF state toward a cardiac-like phenotype by GMT or GMT/miR-133 transduction at all stages (Fig3A). Next, to identify the genes that were regulated by miR-133, we focused on the genes that were differentially expressed between GMT and GMT/miR-133 transduction at all stages. Among 23,474 probes, 46 genes were upregulated, and 129 genes were downregulated by at least 1.5-fold by GMT/miR-133 induction, consistent with the function of miRNAs, typically diminishing the expression of their mRNA targets (Fig3B, Supplementary Table S1). Gene ontology (GO) analyses demonstrated that upregulated genes in the GMT/miR-133-iCMs were significantly enriched for GO terms associated with cardiac function and development, while the downregulated genes were significantly enriched for the GO terms associated with fibroblast signatures, such as cell adhesion, cell proliferation, and collagen fibril organization (Fig3C and D). Scatter plot analyses at day 3 of transduction demonstrated that the upregulated genes induced by GMT/miR-133 were significantly enriched in heart compared to MEFs (P = 7.7E-21), while the downregulated genes in GMT/miR-133-iCMs were highly enriched in MEFs (P = 1.2E-34), indicating that miR-133 induced cardiac gene programs and extinguished fibroblast signatures from the early stages of reprogramming (Fig3E). Microarray and qRT-PCR analyses revealed that cardiac genes related to different functions, such as sarcomere structures (Actn2, Myh6, Tnni3), mitochondrial metabolism (Ppargc1a), and ion channels (Ryr2, Slc8a1, Kcnd2, and Scn5a), were upregulated, while fibroblast genes, Snai1,Col1a1, Col1a2, Fn1, and Postn, were downregulated in the GMT/miR-133-iCMs compared to the GMT-iCMs at day 7 (Fig3F and G). Epithelial genes, such as cdh1 (E-cadherin), Dsp,Pkp1,Ctnnb1,F2r, and Ocln, were not upregulated, suggesting miR-133 did not induce mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) process. Thus, miR-133 silenced fibroblast signatures in parallel with cardiac gene activation from the early stages of reprogramming.

Figure 3. MiR-133 silences fibroblast signatures and activates cardiac programs.

A Heat-map image of microarray data illustrating the global gene expression pattern of MEFs, iCMs, and hearts. The iCMs were sorted as αMHC-GFP+ cells after 3 (D3), 7 (D7), and 18 (D18) days of GMT or GMT/miR-133 transduction. Differentially expressed genes between MEFs and hearts are shown (n = 1).

B Differentially expressed genes between GMT-iCMs and GMT/miR-iCMs are shown (n = 1). See also Supplementaray Table S1.

C, D GO analyses of the upregulated (C) and downregulated (D) genes in GMT/miR-iCMs at all stages. Top 10 GO categories are shown. Cardiac (C) and fibroblast-related (D) GO terms are shown in red.

E The upregulated and downregulated genes in GMT/miR-iCMs at day 3 were analyzed by scatter plots.

F The relative mRNA expression of cardiomyocyte, fibroblast, and epithelial cell genes in D7 GMT/miR-iCMs compared to D7 GMT-iCMs by microarray.

G The relative mRNA expression of D7 GMT/miR-iCMs compared to D7 GMT-iCMs was determined by qRT-PCR (n = 3).

Data information: Data were normalized by the values of GMT-iCMs. All data are presented as means ± SEM (G). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus relevant control.

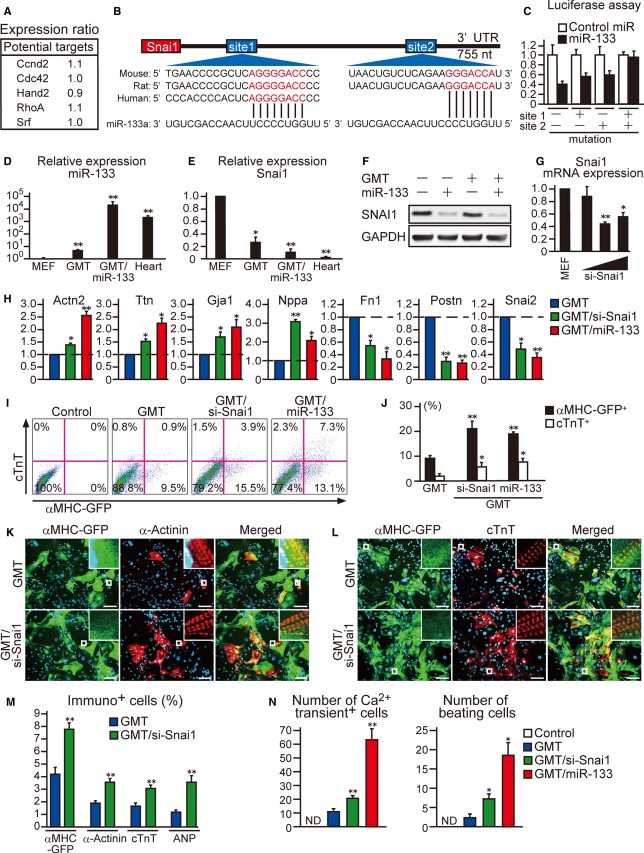

MiR-133 directly represses Snai1 expression during cardiac reprogramming

We then searched for potential direct mRNA targets of miR-133 during cardiac reprogramming. Expression of Ccnd2,Cdc42, Hand2, RhoA, and Srf, shown previously as the direct targets of miR-133, was not significantly altered in GMT-miR-133-iCMs compared to GMT-iCMs, as shown by microarray (Fig4A; Liu & Olson, 2010). Using the miRNA target prediction program, we identified Snai1 as a putative direct target of miR-133 with two conserved miR-133-binding sites within the 3′UTR (Fig4B). Snai1 is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, known as a master regulator of EMT, and induces mesenchymal programs and fibrogenesis during development and disease (Rowe et al, 2009; Li et al, 2010). In luciferase reporter assays with a construct containing a full-length Snai1 3′UTR sequence, miR-133 transfection strongly repressed the luciferase activity by 60%. Mutations of either predicted miR-133-binding site in the Snai1 3′UTR reduced the responsiveness to miR-133, which was almost absent with mutations of both sites, suggesting direct binding of miR-133 to both sites (Fig4C). qRT-PCR confirmed that miR-133 expression was induced by GMT transduction in MEFs and further upregulated by miR-133 overexpression (Fig4D). Inversely, the mRNA expression of Snai1 was high in MEFs, significantly downregulated by GMT and further reduced by 60% with the addition of miR-133 to GMT, consistent with the array data (Figs4E and 3F). Western blot analyses also demonstrated that Snai1 protein expression was strongly downregulated in MEFs by transduction with miR-133 alone or GMT/miR-133 (Fig4F). These results suggested that miR-133 directly targets Snai1, resulting in reduced expression of this protein during reprogramming.

Figure 4. Repression of Snai1 silences fibroblast profile and promotes cardiac reprogramming.

A The relative mRNA expression of potential direct targets of miR-133 in D7 GMT/miR-iCMs compared to D7 GMT-iCMs by microarray.

B Snai1 3′UTR contains two predicted miR-133a binding sites. Both are conserved among species, shown in red.

C MiR-133a directly repressed WT Snai1 3′UTR in luciferase assay, and the repression was abolished when both of binding sites were mutated (n = 3).

D Relative miR-133a expression in MEFs, GMT-iCMs, GMT/miR133-iCMs, and hearts (n = 3).

E Relative mRNA expression of Snai1 in MEFs, GMT-iCMs, GMT/miR133-iCMs, and hearts (n = 3).

F Western blot analyses for Snai1 expression in MEFs, MEFs transfected with miR-133 alone, and MEFs transduced with GMT and GMT/miR-133.

G Relative mRNA expression of Snai1 in MEFs and MEFs transfected with siRNA against Snai1 (5, 15, 100 nM) (n = 3).

H Relative mRNA expression of cardiac (Actn2,Ttn,Gja1,Nppa) and fibroblast genes (Fn1,Postn,Snai2) in MEFs transduced with GMT, GMT/si-Snai1, or GMT/miR-133 (n = 3). See also Supplementary Fig S3A.

I, J FACS analyses for αMHC-GFP+ and cTnT+ cells 1 week after GMT transduction with si-Snai1 or miR-133 transfection. Quantitative data are shown in (J) (n = 3).

K–M Immunocytochemisty for αMHC-GFP, α-actinin, cTnT, and DAPI. Snai1 suppression increased cardiac protein expression in GMT-transduced cells (M, n = 5). See also Supplementary Fig S3C.

N Total number of Ca2+ oscillation+ cells in 10 randomly selected fields per well is shown (the left panel, n = 8). Spontaneously beating cells were counted in each well after 4 weeks of infection (the right panel, n = 3). See also Supplementary Fig S3D and Movie S4.

Data information: All data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus relevant control. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Next, to investigate the possible contribution of Snai1 during cardiac reprogramming, we suppressed Snai1 expression with siRNA in GMT-transduced MEFs (Fig4G). qRT-PCR at day 7 of transduction demonstrated that knockdown of Snai1 in the presence of GMT strongly downregulated expression of multiple fibroblast genes, including Fn1, Postn, and Snai2, to levels comparable with those affected by GMT/miR-133 (Fig4H). Intriguingly, inhibition of Snai1 concomitantly upregulated a panel of cardiac genes related to different functions, such as sarcomere structures (Actn2, Ttn), gap junctions (Gja1), hormones (Nppa), and ion channels (Ryr2 and Kcnd2), in GMT-transduced cells (Fig4H, Supplementary Fig S3A). FACS analyses demonstrated that knockdown of Snai1 significantly increased the induction of α-MHC-GFP+ cells and cTnT+ cells from MEFs in combination with GMT, but not with GMT/miR-133 (Fig4I and J, Supplementary Fig S3B). Immunostaining for cardiac markers, including α-actinin, cTnT, and ANP, demonstrated that Snai1 suppression increased cardiac protein expression in combination with GMT after 4 weeks (Fig4K–M, Supplementary Fig S3C). Snai1 suppression significantly increased spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations and cell contractions in GMT-transduced cells, although not to the levels seen with miR-133 overexpression (Fig4N, Supplementary Fig S3D, Supplementary Movie S4). These results suggested that suppression of Snai1 reduced fibroblast profiles and concomitantly promoted cardiac induction in GMT-transduced fibroblasts, which recapitulated the effects of miR-133 overexpression.

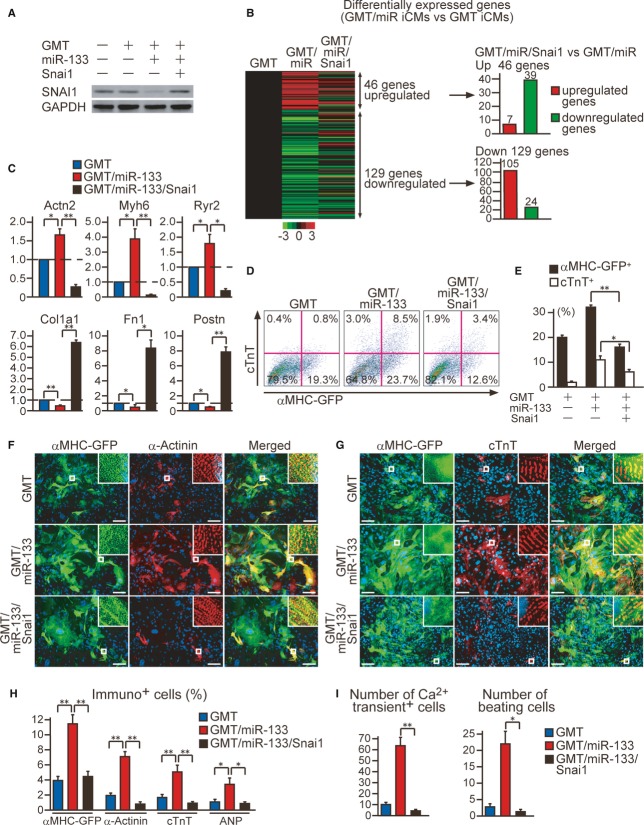

Overexpression of Snai1 maintains fibroblast signatures and disrupts cardiac reprogramming in GMT/miR-133-transduced MEFs

We next asked whether suppression of Snai1 is a consequence of or is required for cardiac reprogramming induced with GMT/miR-133. To address this, we restored Snai1 expression in GMT/miR-133-transduced MEFs by overexpression of Snai1 cDNA without the 3′UTR and investigated whether Snai1 restoration could counteract the effects of miR-133-mediated cardiac reprogramming (Fig5A). Microarray analyses revealed that among 46 genes upregulated by GMT/miR-133 (Fig3B), 39 were suppressed by Snai1 overexpression. In contrast, 105 out of 129 genes downregulated by miR-133 addition (Fig3B) were upregulated by Snai1 restoration, suggesting most portions of the transcriptional changes effected by miR-133 were mediated via Snai1 suppression (Fig5B). The genes upregulated and downregulated by Snai1 overexpression were identified as fibroblast- and cardiac-related genes, respectively, and qRT-PCR analyses confirmed the array data (Fig5C, Supplementary Fig S3E and F). These results suggest that Snai1 repression is critical for silencing fibroblast programs and activating the cardiac phenotype in MEFs induced with GMT/miR-133. Snai1 overexpression also inhibited both the induction of α-MHC-GFP and cTnT expression in GMT/miR-133-transduced fibroblasts, as shown by FACS analyses (Fig5D and E), and the expression of endogenous cardiac proteins, α-actinin, cTnT, and ANP, in GMT/miR-133-transduced cells at 4 weeks, as revealed by immunocytochemistry (Fig5F–H, Supplementary Fig S3G). Consistent with this, constitutive expression of Snai1 strongly suppressed spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in GMT/miR-133-transduced cells and inhibited generation of beating iCMs at 4 weeks, overriding the positive effects of miR-133 (Fig5I). These results suggested that downregulation of Snai1 is critical for suppressing fibroblast profiles and cardiac reprogramming in MEFs induced with GMT/miR-133.

Figure 5. Overexpression of Snai1 inhibits cardiac reprogramming.

A Western blot analyses for Snai1 expression in MEFs and MEFs transduced with GMT, GMT/miR-133, and GMT/miR-133 with Snai1 overexpression.

B Heat-map image of microarray data for GMT-, GMT/miR-, and GMT/miR/Snai1-iCMs sorted as αMHC-GFP+ cells after 1 week of transduction (left panel, n = 1). Differentially expressed genes between GMT-iCMs and GMT/miR-iCMs are shown (see also Fig3B). Thirty-nine genes out of 46 upregulated genes were suppressed by Snai1 overexpression, while 105 genes out of 129 downregulated genes were increased with Snai1 transduction (right panel).

C The relative mRNA expression of D7 GMT/miR-iCMs compared to D7 GMT-iCMs was determined by qRT-PCR (n = 3). Relative mRNA expression of cardiac (Actn2,Myh6,Ryr2) and fibroblast genes (Col1a1,Fn1,Postn) in MEFs transduced with GMT and GMT/miR-133 with or without Snai1 overexpression (n = 3).

D, E FACS analyses for αMHC-GFP + and cTnT+ cells 1 week after GMT and GMT/miR-133 transduction with or without Snai1 overexpression. Quantitative data are shown in (E) (n = 3).

F–H Immunocytochemisty for αMHC-GFP, α-actinin, cTnT, and DAPI. Snai1 overexpression suppressed cardiac protein expression in GMT/miR-133-transduced cells (H, n = 5).

I Numbers of Ca2+ oscillation+ cells in 10 randomly selected fields per well are shown (left panel, n = 8). Number of spontaneously beating cells in each well after 4 weeks of infection (right panel, n = 3).

Data information: All data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus relevant control. Scale bars, 100 μm.

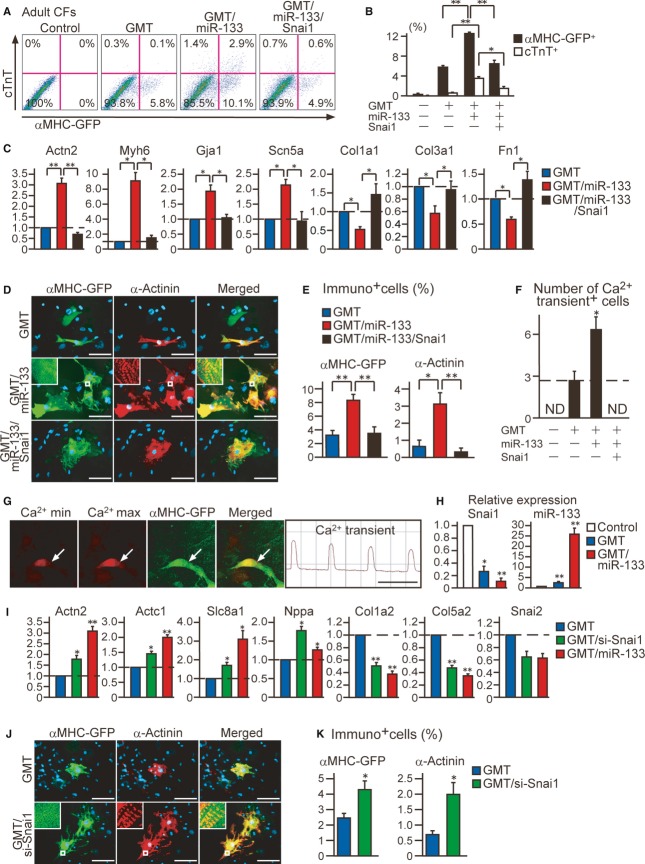

MiR-133-induced Snai1 suppression is critical for cardiac reprogramming in adult mouse cardiac fibroblasts

We next investigated whether the miR-133-mediated suppression of Snai1 also plays critical roles in cardiac reprogramming in adult mouse CFs. Similar to the MEF cultures, we did not detect contamination of cardiomyocytes in adult CF cultures derived from α-MHC-GFP mice. Transfection of miR-133 alone did not induce cardiac reprogramming in adult CFs either with or without the JAK inhibitor (Supplementary Fig S3H). We then introduced miR-133 with GMT and found significantly increased induction of α-MHC-GFP+ and cTnT+ cells from adult CFs by FACS at 1 week (Fig6A and B). qRT-PCR demonstrated that miR-133 upregulated multiple cardiac genes and concomitantly downregulated fibroblast gene expression in adult CFs in combination with GMT (Fig6C). Immunocytochemistry and Ca2+ imaging also showed that addition of miR-133 to GMT promoted cardiac induction from adult CFs (Fig6D–G, Supplementary Movie S5). These results suggested that miR-133 promotes cardiac reprogramming in adult CFs, but with lower reprogramming efficiency compared to that in MEFs.

Figure 6. MiR-133-mediated Snai1 repression is critical for cardiac reprogramming in adult cardiac fibroblasts.

A, B FACS analyses for αMHC-GFP + and cTnT+ cells in adult CFs 1 week after GMT and GMT/miR-133 transduction with or without Snai1 overexpression. Quantitative data are shown in (B) (n = 3).

C Relative mRNA expression of cardiac (Actn2,Myh6,Gja1,Scn5a) and fibroblast genes (Col1a1,Col3a1,Fn1) in adult CFs transduced with GMT and GMT/miR-133 with or without Snai1 overexpression (n = 3).

D, E Immunocytochemisty for αMHC-GFP and α-actinin with DAPI staining in GMT, GMT/miR-133, or GMT/miR-133/Snai1-transduced adult CFs 4 weeks after transduction. High-magnification views in insets show sarcomeric organization. Quantitative data are shown in (E) (n = 5).

F, G Total number of Ca2+ oscillation+ cells in 10 randomly selected fields per well is shown in (F) (n = 3). Spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations observed in adult CF-derived GMT/miR-133-iCMs (arrows in G), corresponding to Supplementary Movie S5. The Rhod-3 images and intensity trace are shown in (G).

H Relative Snai1 mRNA and miR-133a expression in adult CFs, GMT-iCMs, and GMT/miR133-iCMs (n = 3).

I Relative mRNA expression of cardiac (Actn2,Actc1,Slc8a1,Nppa) and fibroblast genes (Col1a2,Col5a2,Snai2) in adult CFs transduced with GMT, GMT/si-Snai1, or GMT/miR-133 (n = 3).

J, K Immunocytochemisty for αMHC-GFP and α-actinin in GMT or GMT/si-Snai1 transduced adult CFs 4 weeks after transduction. High-magnification views in insets show sarcomeric organization. Quantitative data are shown in (K) (n = 5).

Data information: All data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus relevant control. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Next, we analyzed the link between miR-133 and Snai1 during reprogramming in adult CFs. The mRNA expression of Snai1 was high in adult CFs, downregulated by GMT, and further reduced by 50% with the addition of miR-133 to GMT, which was inversely correlated with the expression of miR-133 (Fig6H). qRT-PCR demonstrated that knockdown of Snai1 upregulated a panel of cardiac genes related to multiple functions and repressed fibroblast genes in GMT-transduced adult CFs (Fig6I). Immunostaining revealed that inhibition of Snai1 increased the induction of α-MHC-GFP+ cells and α-actinin+ cells from adult CFs in combination with GMT (Fig6J and K). These results suggested that suppressing Snai1 could in turn suppress fibroblast programs and promote cardiac induction in adult CFs. We then also overexpressed the Snai1 cDNA without 3′UTR in GMT/miR-133-transduced adult CFs and found reduced α-MHC-GFP+ and cTnT+ cells, as measured by FACS (Fig6A and B). qRT-PCR revealed downregulated expression of cardiac genes and upregulated expression of multiple fibroblast genes by Snai1 overexpression, suggesting that Snai1 repression is critical for silencing fibroblast signatures and inducing cardiac reprogramming in adult CFs (Fig6C). Immunocytochemistry and functional studies also revealed that Snai1 overexpression strongly inhibited cardiac reprogramming in GMT/miR-133-transduced adult CFs (Fig6D–F).

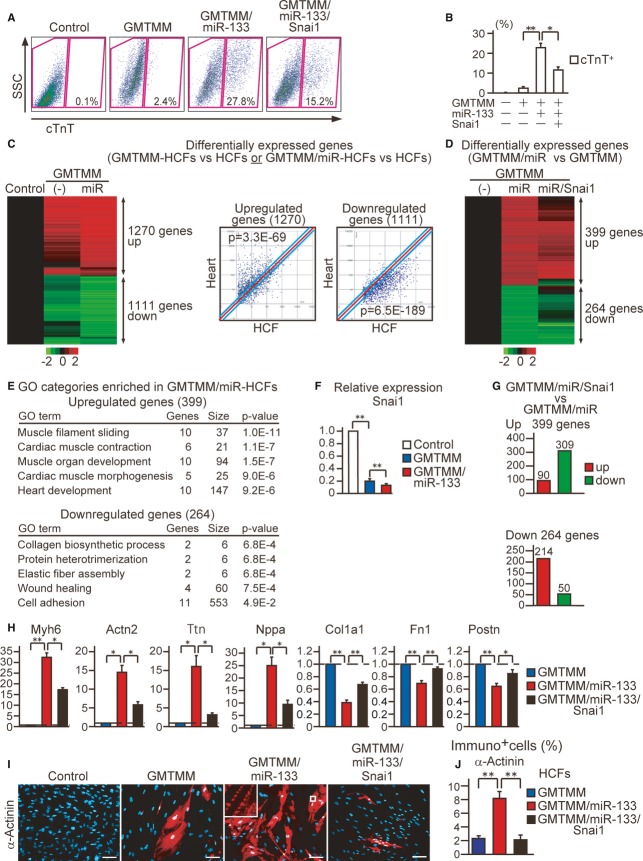

MiR-133-mediated Snai1 repression is also critical in human cardiac reprogramming

We next tested whether miR-133-mediated Snai1 suppression also plays important roles in human cardiac reprogramming using HCFs. Transfection of miR-133 alone or 4miRs with or without JAKI-1 did not induce cardiac reprogramming (Supplementary Fig S4A). In contrast, using new lentiviral vectors to transduce the genes efficiently into HCFs (Supplementary Fig S4B), we demonstrated that transduction of lentiviral GMTMM induced cTnT+ and α-actinin+ cells in 2–8% of HCFs (Fig7A and B, Supplementary Fig S4C). The induction rate increased to 23–27% of HCFs with addition of miR-133 to GMTMM (Fig7A and B, Supplementary Fig S4C). Microarray analyses further revealed that GMTMM or GMTMM/miR-133 transduction upregulated 1,270 cardiac-enriched genes and downregulated 1,111 fibroblast-related genes in HCFs, suggesting global transcriptional changes toward cardiac fate induced by the reprogramming factors (Fig7C). Differential gene expression analyses between GMTMM-HCFs and GMTMM/miR-133-HCFs showed that addition of miR-133 upregulated 399 genes and downregulated 264 genes (Fig7D). GO term analyses associated the upregulated genes with cardiac function and the downregulated genes with fibroblast signatures, suggesting that miR-133 promotes cardiac reprogramming in HCFs (Fig7E). Snai1 mRNA expression was suppressed by GMTMM and further reduced by 40% with GMTMM/miR-133 in human cardiac reprogramming (Fig7F). Microarray analyses demonstrated that the transcriptional changes effected by miR-133 were largely counteracted by Snai1 overexpression, suggesting the miR-133-induced cardiac reprogramming was mainly mediated through Snai1 suppression (Fig7D and G). Consistent with this, qRT-PCR, FACS analyses, and immunocytochemistry revealed that Snai1 overexpression inhibited GMTMM/miR-133-mediated cardiac induction (Fig7A, B, H, I and J, Supplementary Fig S4D and E), whereas Snail knockdown increased the induction of cardiac genes in combination with GMTMM as measured by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig S4F). FACS analyses and immunostaining also demonstrated that knockdown of Snai1 significantly increased expression of α-actinin+ cells in HCFs in combination with GMTMM, suggesting that suppressing Snai1 expression promotes cardiac induction (Supplementary Fig S4G–I). Taken together, these results suggest that miR-133-mediated Snai1 suppression is also crucial for human cardiac reprogramming.

Figure 7. MiR-133/Snai1 pathway is critical for human cardiac reprogramming.

A, B FACS analyses for cTnT+ cells in HCFs 1 week after GMTMM, GMTMM/miR-133, and GMTMM/miR-133/Snai1 transduction. Quantitative data are shown in (B) (n = 4).

C Heat-map image of microarray data illustrating the global gene expression pattern of HCFs, GMTMM-HCFs, and GMTMM/miR-133-HCFs after 1 week of transduction (n = 1, left panel). The differentially expressed genes between GMTMM- or GMTMM/miR-133-HCFs and HCFs are shown. Cardiac genes were upregulated and fibroblast genes were downregulated by transduction of the reprogramming factors, as shown in the scatter plot analyses (right panel).

D 399 genes were upregulated and 264 genes were downregulated by the addition of miR-133 to GMTMM.

E GO term analyses of the upregulated and downregulated genes, shown in (D). Cardiac- and fibroblast-related GO terms are shown.

F The mRNA expression of Snai1 in HCFs, GMTMM-HCFs, and GMTMM/miR-133-HCFs (n = 3).

G Snai1 restoration counteracted the effects of miR-133. 309 out of 399 upregulated genes were suppressed by Snai1 overexpression, while 214 out of 264 downregulated genes were increased with Snai1. See also Fig7D.

H Relative mRNA expression of cardiac (Myh6, Actn2,Ttn,Nppa) and fibroblast genes (Col1a1,Fn1,Postn) in GMTMM-, GMTMM/miR-133-, and GMTMM/miR-133/Snai1-HCFs after 1 week of transduction (n = 3).

I, J Immunocytochemisty for α-actinin and DAPI. Snai1 overexpression suppressed cardiac protein expression in GMTMM/miR-133-transduced HCFs (J, n = 10). High-magnification view in inset shows sarcomeric organization.

Data information: All data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus relevant control. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Discussion

Direct reprogramming is characterized as a process that progressively activates the target cell program and concomitantly suppresses the starting-cell profile without passing through a stem cell state by overexpression of lineage-specific transcription factors or miRNAs. In this study, we demonstrated that overexpression of miR-133 in the presence of these transcription factors promoted cardiac reprogramming in mouse and human, partly by suppressing Snai1, a master regulator of EMT, and silencing the fibroblast program.

The miR-133 family comprises three miRNAs: miR-133a-1, miR-133a-2, and miR-133b. MiR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2 have identical sequences and are expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscles. Indeed, mice lacking both miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2 undergo embryonic or neonatal death due to heart defects, suggesting critical roles of miR-133a in cardiogenesis (Liu et al, 2008). Consistent with this, addition of miR-133a to cardiac reprogramming factors increased cardiac reporter and gene expression, shifted the global gene expression profile of the iCMs toward a cardiac fate, and generated more functional iCMs in direct reprogramming.

Our findings support that combining lineage-specific transcription factors and miRNAs provides a powerful approach to improve direct conversion of fibroblasts into another lineage. Yoo et al (2011) reported that a combination of neural-specific miRNAs, miR-9/9*, and miR-124, and neurogenic transcription factors directly reprogrammed human fibroblasts into functional neuronal cells (Yoo et al, 2011). Recently, Nam et al (2013) reported that addition of miR-1 and miR-133 to Gata4, Hand2, Myocd, and Tbx5 promoted cardiac reprogramming in human fibroblasts (Nam et al, 2013). However, the mechanistic basis underlying direct reprogramming by the transcription factor/miRNA combinations was not established in these previous studies. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms and importance of suppressing fibroblast signatures during direct reprogramming remained largely unknown.

In the present study, we found that miR-133 suppressed a large set of fibroblast genes and concomitantly activated cardiac gene programs during cardiac reprogramming when used in combination with GMT or GMTMM. Among many predicted targets of miR-133, we identified Snai1 as a novel direct target of the miRNA and demonstrated that Snai1 repression silences fibroblast programs and promotes cardiac reprogramming, recapitulating the effects of miR-133 overexpression. In contrast, overexpression of Snai1 inhibited suppression of fibroblast genes and activation of cardiac programming induced with GMT/miR-133. Thus, silencing fibroblast signatures, mediated by miR-133/Snai1, could be a key molecular roadblock during direct cardiac reprogramming. Intriguingly, this process is similar to the MET, a critical step during the reprogramming of fibroblasts into iPSCs by the Yamanaka factors (Li et al, 2010; Samavarchi-Tehrani et al, 2010). During iPSC generation, Oct4 and Sox2 suppress Snai1, while Klf4 induces epithelial genes including E-cadherin (Li et al, 2010). Snai1 downregulation and E-cadherin upregulation cooperatively suppress EMT signals and activate an epithelial program, leading to MET and iPSC generation. Similar to our findings, blocking MET by overexpression of Snai1 or addition of a Snai1 activator (transforming growth factor β) impaired iPSC generation, whereas inducing MET by addition of transforming growth factor β inhibitors promoted iPSC induction (Li et al, 2010; Samavarchi-Tehrani et al, 2010). Thus, it is conceivable that silencing fibroblast signatures by repressing Snai1 might be a common pathway in the early phase of reprogramming from fibroblasts to another lineage and that manipulation of this pathway could be a new target to enhance direct reprogramming in general. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating a molecular mechanism of direct cardiac reprogramming.

While we found that the miR-133/Snai1 pathway is critical for cardiac reprogramming, the iCM population was heterogeneous and most of the cells remained as partially reprogrammed cardiac cells in culture (Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, the reprogramming efficiency of adult CFs was low compared with MEFs in this study and our previous data using neonatal CFs (Ieda et al, 2010). Differences between mouse lines used and transcriptional and epigenetic differences between fibroblasts might have contributed to the lower reprogramming efficiency in adult CFs. Because miR-133 has numerous predicted targets, and knockdown of Snai1 increased cardiac induction, but not to the level observed with miR-133 overexpression, some additional pathways might be involved in miR-133-mediated cardiac reprogramming (Liu & Olson, 2010). Nevertheless, given that the in vivo environment might be more permissive than culture dishes for reprogramming, GMT/miR-133 transduction or Snai1 knockdown with GMT in vivo might be sufficient to repair damaged hearts (Qian et al, 2012; Song et al, 2012). Further in vitro and in vivo studies are thus needed to progress our understanding of molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac reprogramming and apply this new technology to future regenerative therapies.

Materials and Methods

Generation of αMHC-GFP and Mesp1-GFP mice

Transgenic mice overexpressing GFP under the control of an α-MHC promoter were generated as described previously (Ieda et al, 2010). Mesp1-GFP mice were obtained by crossing Mesp1-Cre mice and CAG-CAT-EGFP reporter mice (Saga et al, 1999; Kawamoto et al, 2000). The Keio University Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments approved all experiments in this study.

Quantitative RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells, and qRT-PCR was performed on a StepOnePlus™ (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan probes: Actc1 (Mm01333821_m1, Hs00606316_m1), Myh6 (Mm00440354_m1, Hs00411908_m1), Ryr2 (Mm00465877_m1, Hs00892842_m1), Gja1 (Mm00439105_m1), Nppa (Mm01255747_g1, Hs00383230_g1), Actn2 (Mm00473657_m1, Hs00153809_m1), Kcnd2 (Mm0116732_m1), Slc8a1 (Mm01232254_m1, Hs01062258_m1), Scn5a (Mm00451971_m1), Tnni3 (Mm00437164_m1), Tnnt2 (Hs00165960_m1), Ttn (Mm00621005_m1, Hs00399225_m1), Myl2 (Mm00440384_m1, Hs00166405_m1), Myl7 (Mm00491655_m1), Hcn4 (Mm01176086_m1), isl1 (Mm00517585_m1), Col1a1 (Mm00801666_g1, Hs00164004_m1), Col1a2 (Mm00483888_m1), Col3a1 (Mm01254476_m1), Col5a2 (Mm00483675_m1), Fn1 (Mm01256744_m1, Hs00365052_m1), Snai1 (Mm00441533_g1, Hs00195591_m1), Snai2 (Mm00441531_m1), Ddr2 (Mm0000445615_m1), Postn (Mm00450111_m1, Hs00170815_m1), Hsa-miR-133a (1102119-Q). mRNA levels were normalized by comparison to Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1, Hs02758991_g1). miRNA levels were normalized by comparison to Rnu6b (0811824-H) snRNA.

Molecular cloning, retroviral infection, lentiviral infection, and miRNA mimics transfection

To construct the pMXs retroviral vectors, we amplified the coding regions of GFP, Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5, and Snai1 by PCR and subcloned them into respective pMXs vectors for transfection into Plat-E cells using Fugene 6 (Roche) to generate retroviruses (Ieda et al, 2010). We generated lentiviral vectors by subcloning human Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5, Mesp1, Myocd, and Snai1 (HuPEX, AIST) into the CSII-CMV-RfA plasmid (RIKEN BRC) using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). To generate the lentiviruses, we transfected the vectors into HEK293 cells with pCAG-HIVgp and pCMV-VSV-G-RSV-Rev plasmids (RIKEN BRC) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The CSII-CMV-Venus vector was used to determine transduction efficiency. Virus-containing supernatants were collected after 48 h and used for transduction. Synthetic mimics of mature miRNAs (Thermo Scientific) and the siRNA pool (Thermo Scientific) were transfected simultaneously into cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Synthetic mimics of mature miRNAs and siRNA pool: miRIDIAN microRNA Mouse mmu-miR-1-Mimic (C-310376-07-0020), miRIDIAN microRNA Mouse mmu-miR-133a-Mimic (C-310407-07-0020), miRIDIAN microRNA Mouse mmu-miR-208a-3p-Mimic (C-310501-05-0020), miRIDIAN microRNA Mouse mmu-miR-499-Mimic (C-310727-01-0020), miRIDIAN microRNA Mimic Negative Control #2 (CN-002000-01-05), siGENOME Mouse Snai1 siRNA - SMARTpool (M-062765-00-0020), siGENOME Human Snai1 siRNA - SMARTpool (M-010847-00-0020). After 24 h, the medium was replaced with D-MEM (high glucose) with L-Glutamate and Phenol Red (Wako, 044-29765)/Medium199 with Earle's Salts, L-Glutamate and 22 g/l Sodium Bicarbonate (Gibco, 11150-059)/10% Hyclone Characterized FBS (Thermo Scientific, SV30014.03) medium and changed every 2–3 days. JAK inhibitor I (1 nM, EMD Biosciences) treatment was initiated 2 days after transfection and continued daily for 7 days.

Cell culture

For MEF isolation, embryos isolated from 12.5-day pregnant mice were washed with PBS, and the head and visceral tissues were carefully removed. The remaining parts of the embryos were washed in fresh PBS, minced using a pair of scissors, transferred into a 0.25 mM trypsin/1 mM EDTA solution (3 ml per embryo), and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. An additional 3 ml of trypsin/EDTA solution was then added, and the mixture was further incubated at 37°C for 20 min. After trypsinization, an equal amount of medium (6 ml of DMEM containing 10% FBS per embryo) was added and pipetted up and down a few times to help tissue dissociation. After incubation of the tissue/medium mixture for 5 min at room temperature, the supernatant was transferred into a new tube and cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in DMEM/10% FBS (Thermo Scientific, SV30014.03) for culturing at 37°C in 5% CO2. For isolation of mouse adult cardiac fibroblasts, αMHC-GFP TG adult mouse hearts were minced into small pieces < 1 mm3 in size. The explants were plated on gelatin-coated dishes and cultured for 10–14 days in explant medium (IMDM with L-Glutamate and 25 mM HEPES (Gibco, 12440-053)/20% FBS). Migrated fibroblasts were harvested and filtered with 40-μm cell strainers (BD) to avoid contamination with tissue fragments. The αMHC-GFP–/Thy1+ CFs were FACS sorted and plated at a density of 104/cm2 for the retrovirus transduction.

Human atrial tissues were obtained from patients undergoing cardiac surgery (age 1 month to 80 year; average age, 35 year) with informed consent in conformation with the guidelines of the Keio University Ethics Committee. For isolation of human cardiac fibroblasts, human hearts were minced into small pieces < 1 mm3 in size. The explants were plated on gelatin-coated dishes and cultured for 14 days in the explant medium. Migrated fibroblasts were harvested, filtered with 40-μm cell strainers (BD), and plated at a density of 5 × 103/cm2 for the virus transduction. For all experiments, we used fibroblasts of early passage number (P1-3). The Keio Center for Clinical Research approved all of the human experiments in this study (20100131).

FACS analyses and sorting

For GFP expression analyses, cells were harvested from culture dishes and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) with FlowJo software. For αMHC-GFP/cTnT expression, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min, permealized with saponin, and stained with anti-cTnT and anti-GFP antibodies, followed by secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa 488 and 647, respectively. For α-actinin or cTnT expression, cells were stained with anti-α-actinin or cTnT antibody, followed by secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 647. For iCM sorting, cells were sorted as αMHC-GFP + cells, and for Mesp1-GFP–/Thy1+ cell sorting, cells were incubated with APC-conjugated anti-Thy1 antibody (eBioscience) and sorted by FACS Aria.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, blocked by 5% serum, and incubated with primary antibodies against sarcomeric α-actinin (Sigma Aldrich), vimentin (Progen), Collagen 1 (Millipore), GFP (Invitrogen), cTnT (Thermo Scientific), ANP (Millipore), Myl7 (Synaptic Systems), or Nkx2.5 (Santa Cruz), and subsequently with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa 488 or 546 (Molecular Probes), followed by DAPI counterstaining (Invitrogen). The percentage of cells immunopositive for GFP, α-actinin, cTnT, and ANP were counted in six randomly selected fields per well in three independent experiments, and 500–1,000 cells were counted in total. The measurements and calculations were made in a blinded manner.

EdU labeling assay

For the experiments assessing cell proliferation, 10 μM EdU was added to the culture medium after 2 weeks of transduction and maintained throughout the culture for a further 2 weeks. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized, incubated with anti-cTnT antibody followed by secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 546 (for immunocytochemistry) or 647 (for FACS), and then incubated with the EdU reaction cocktail following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

Ca2+ imaging and counting beating cells

Ca2+ imaging was performed according to the standard protocol. Briefly, cells were labeled with Rhod-3 (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and incubated for an additional 1 h to allow de-esterification of the dye. Rhod-3 labeled cells were analyzed at 37°C by LSM 510 META confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss). Imaging of the Ca2+ oscillations was possible for only a short time due to the increasing background fluorescence from the medium, and thus, the measurements were taken within 30 min after changing to the Tyrode's buffer. The Ca2+ oscillation+ cells were counted in 10 randomly selected fields per well in at least three independent experiments, and a minimum of 1,000 cells were counted in total. The total number of Ca2+ oscillation+ cells in 10 randomly selected fields per well is shown.

For counting beating cells, we seeded 50,000 fibroblasts per well on 12-well plates, performed cell transductions, and then monitored cell contraction. The number of spontaneously contracting cells was manually counted in each well in at least three independent experiments. The number of beating cells per well is shown. The measurements and calculations were made in a blinded manner.

Western blotting

Lysates were prepared by homogenization of cells in RIPA buffer and run on SDS–PAGE to separate proteins prior to the immunoblot analyses. After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, immunodetection was performed with antibodies to Snai1 (Abcam) and Gapdh (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology). The antibody-bound proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence detection (ECL, Amersham).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

For construction of the Snai1 3′UTR reporter, the CMV promoter was subcloned into the promoterless pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) upstream of the luciferase gene. A 755-bp Snai1 3′UTR fragment containing miR-133a-binding sites was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the modified pGL3-Basic vector. The activities of firefly luciferase and renilla luciferase in the control vector were determined by the dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega). Mutations of the AGGGGACCA miR-133a seed binding sequence were constructed through PCR-based mutagenesis (Stratagene). The miRNA target prediction program (http://cbio.mskcc.org/cgi-bin/mirnaviewer/mirnaviewer.pl) was used to identify putative targets.

Gene microarray analyses

Mouse genome-wide gene expression analyses were performed using 3D-Gene Mouse Oligo chip 25k (Toray Industries Inc.). For efficient hybridization, this microarray is three-dimensional and is constructed with a well as the space between the probes and cylinder stems with 70-mer oligonucleotide probes on the top. RNA was extracted from MEFs, GMT-, GMT/miR-133-, or GMT/miR-133/Snai1-induced αMHC-GFP+ cells, neonatal mouse heart tissues, HCFs, GMTMM-, GMTMM/miR-133-, GMTMM/miR-133/Snai1-transduced HCFs using ReliaPrep™ RNA Cell Miniprep System (Promega). Total RNA was labeled with Cy5 using the Amino Allyl MessageAMP II aRNA Amplification Kit (Applied Biosystems), and the hybridization was performed using the supplier's protocols (http://www.3d-gene.com). Hybridization signals were scanned using 3D-Gene Scanner (Toray Industries Inc.) and processed by extraction (Toray Industries Inc.). The raw data of each spot were normalized by substitution with a mean intensity of the background signal determined by the combined signal intensities of all blank spots at 95% confidence intervals. Raw data intensities > 2 standard deviations (SD) of the background signal intensity were considered to be valid. Detected signals for each gene were normalized by the global normalization method. Heatmap images for differentially expressed genes (more than 2-fold or 1.5-fold difference) were processed using the Cluster 2.0 software, and the results were displayed with the TreeView program (http://rana.lbl.gov/eisen/). Scatter plot analyses were processed using Microsoft Excel. Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using GeneCodis. This method computes hypergeometric P-values for over- or under-representation of each GO term in the specified ontology for the gene set of interest. Moderated t-statistics and the associated P-values were calculated by the Welch t-test using Microsoft Excel. Differential gene expression was defined using the statistics/threshold combination.

Statistical analyses

Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using Student's t-test or ANOVA. P-values of < 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Data deposition

Microarray data are deposited in GEO with accession number GSE56913.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of the Fukuda lab, S. Mikami, H. Mochizuki, and H. Miyoshi (RIKEN BRC), for discussion and reagents. M. I. was supported by research grants from JST CREST, JSPS, the Mitsubishi Foundation, Banyu Life Science, the Uehara Memorial Foundation, Senshin Medical Research Foundation, AstraZeneca, and Takeda Science Foundation, and N. M. was supported by research grants from Japan Heart Foundation Research Grant, Keio University Medical Science Fund, and Keio University Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists.

Author contributions

NM and MI designed the experiments. NM, HYamak, KM, TS, TM, MI, HN, MA, RW, KI, YK, RA, HYamag, and NG carried out the experiments. NM, TN, RK, TF, STa, STo, HH, and KF analyzed the data. NM and MI wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information for this article is available online: http://emboj.embopress.org

References

- Addis RC, Epstein JA. Induced regeneration–the progress and promise of direct reprogramming for heart repair. Nat Med. 2013;19:829–836. doi: 10.1038/nm.3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JX, Krane M, Deutsch MA, Wang L, Rav-Acha M, Gregoire S, Engels MC, Rajarajan K, Karra R, Abel ED, Wu JC, Milan D, Wu SM. Inefficient reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using gata4, mef2c, and tbx5. Circ Res. 2012;111:50–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JD, Stone NR, Liu L, Spencer CI, Qian L, Hayashi Y, Delgado-Olguin P, Ding S, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts toward a cardiomyocyte-like state. Stem Cell Rep. 2013;1:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DW, Tapia N, Hermann A, Hemmer K, Hoing S, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Zaehres H, Wu G, Frank S, Moritz S, Greber B, Yang JH, Lee HT, Schwamborn JC, Storch A, Scholer HR. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into neural stem cells by defined factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagawa K, Miyamoto K, Yamakawa H, Muraoka N, Sadahiro T, Umei T, Wada R, Katsumata Y, Kaneda R, Nakade K, Kurihara C, Obata Y, Miyake K, Fukuda K, Ieda M. Induction of cardiomyocyte-like cells in infarct hearts by gene transfer of Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5. Circ Res. 2012;111:1147–1156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.271148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardena TM, Egemnazarov B, Finch EA, Zhang L, Payne JA, Pandya K, Zhang Z, Rosenberg P, Mirotsou M, Dzau VJ. MicroRNA-mediated in vitro and in vivo direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2012;110:1465–1473. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson RL, Babiarz JE, Venere M, Blelloch R. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs promote induced pluripotency. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:459–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto S, Niwa H, Tashiro F, Sano S, Kondoh G, Takeda J, Tabayashi K, Miyazaki J. A novel reporter mouse strain that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon Cre-mediated recombination. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:263–268. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Liang J, Ni S, Zhou T, Qing X, Li H, He W, Chen J, Li F, Zhuang Q, Qin B, Xu J, Li W, Yang J, Gan Y, Qin D, Feng S, Song H, Yang D, Zhang B, et al. A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Bezprozvannaya S, Williams AH, Qi X, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3242–3254. doi: 10.1101/gad.1738708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Olson EN. MicroRNA regulatory networks in cardiovascular development. Dev Cell. 2010;18:510–525. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marro S, Pang ZP, Yang N, Tsai MC, Qu K, Chang HY, Sudhof TC, Wernig M. Direct lineage conversion of terminally differentiated hepatocytes to functional neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka N, Ieda M. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into myocytes to reverse fibrosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:21–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam YJ, Song K, Luo X, Daniel E, Lambeth K, West K, Hill JA, DiMaio JM, Baker LA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Reprogramming of human fibroblasts toward a cardiac fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5588–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301019110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protze S, Khattak S, Poulet C, Lindemann D, Tanaka EM, Ravens U. A new approach to transcription factor screening for reprogramming of fibroblasts to cardiomyocyte-like cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, Liu L, Conway SJ, Fu JD, Srivastava D. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RG, Li XY, Hu Y, Saunders TL, Virtanen I, Garcia de Herreros A, Becker KF, Ingvarsen S, Engelholm LH, Bommer GT, Fearon ER, Weiss SJ. Mesenchymal cells reactivate Snail1 expression to drive three-dimensional invasion programs. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:399–408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Takagi A, Kitajima S, Miyazaki J, Inoue T. MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development. 1999;126:3437–3447. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Golipour A, David L, Sung HK, Beyer TA, Datti A, Woltjen K, Nagy A, Wrana JL. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Nam YJ, Luo X, Qi X, Tan W, Huang GN, Acharya A, Smith CL, Tallquist MD, Neilson EG, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors. Nature. 2012;485:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava D, Ieda M. Critical factors for cardiac reprogramming. Circ Res. 2012;111:5–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.271452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanyam D, Lamouille S, Judson RL, Liu JY, Bucay N, Derynck R, Blelloch R. Multiple targets of miR-302 and miR-372 promote reprogramming of human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo E, Rampalli S, Risueno RM, Schnerch A, Mitchell R, Fiebig-Comyn A, Levadoux-Martin M, Bhatia M. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to multilineage blood progenitors. Nature. 2010;468:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nature09591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Sudhof TC, Wernig M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada R, Muraoka N, Inagawa K, Yamakawa H, Miyamoto K, Sadahiro T, Umei T, Kaneda R, Suzuki T, Kamiya K, Tohyama S, Yuasa S, Kokaji K, Aeba R, Yozu R, Yamagishi H, Kitamura T, Fukuda K, Ieda M. Induction of human cardiomyocyte-like cells from fibroblasts by defined factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12667–12672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304053110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo AS, Sun AX, Li L, Shcheglovitov A, Portmann T, Li Y, Lee-Messer C, Dolmetsch RE, Tsien RW, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated conversion of human fibroblasts to neurons. Nature. 2011;476:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.