Abstract

Objective

To estimate the incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a sociodemographically diverse southeastern Michigan source population of 2.4 million people.

Methods

SLE cases fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria (primary case definition) or meeting rheumatologist-judged SLE criteria (secondary definition) and residing in Wayne or Washtenaw Counties during 2002–2004 were included. Case finding was performed from 6 source types, including hospitals and private specialists. Age-standardized rates were computed, and capture–recapture was performed to estimate underascertainment of cases.

Results

The overall age-adjusted incidence and prevalence (ACR definition) per 100,000 persons were 5.5 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 5.0–6.1) and 72.8 (95% CI 70.8–74.8). Among females, the incidence was 9.3 per 100,000 persons and the prevalence was 128.7 per 100,000 persons. Only 7 cases were estimated to have been missed by capture–recapture, adjustment for which did not materially affect the rates. SLE prevalence was 2.3-fold higher in black persons than in white persons, and 10-fold higher in females than in males. Among incident cases, the mean ± SD age at diagnosis was 39.3 ± 16.6 years. Black SLE patients had a higher proportion of renal disease and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (40.5% and 15.3%, respectively) as compared to white SLE patients (18.8% and 4.5%, respectively). Black patients with renal disease were diagnosed as having SLE at younger age than white patients with renal disease (mean ± SD 34.4 ± 14.9 years versus 41.9 ± 21.3 years; P = 0.05).

Conclusion

SLE prevalence was higher than has been described in most other population-based studies and reached 1 in 537 among black female persons. There were substantial racial disparities in the burden of SLE, with black patients experiencing earlier age at diagnosis, >2-fold increases in SLE incidence and prevalence, and increased proportions of renal disease and progression to ESRD as compared to white patients.

Estimating the incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in the general population is challenging and resource-intensive to perform. In part, this is due to the protean and systemic nature of the disease and the attendant diagnostic complexity that requires the synthesis of a multitude of clinical and laboratory findings, often obtained from a variety of health care settings. In the US, the fragmented health care system and lack of existing infrastructure suitable for the surveillance of autoimmune diseases such as SLE further complicates the implementation of population-based efforts to ascertain and validate cases. As a result, existing estimates of the incidence and prevalence of SLE vary widely, with close to 10-fold differences in published incidence estimates from the US (1,2). In response to the need for accurate and contemporary statistics related to the risk and burden of SLE, we developed the Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance (MILES) program, which covers a sociodemo-graphically diverse population in southeastern Michigan, consisting of ~2.4 million persons or ~25% of the population of Michigan (3).

In partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH), we implemented the MILES program with the primary goal of ascertaining and validating all diagnosed cases of SLE in persons residing in the geographic region of the source population, in order to derive population-based incidence and prevalence estimates for SLE during 2002–2004. Given the large scope and diversity of the underlying population, the MILES program has enabled the characterization of disease patterns in population subsets with a high level of detail and precision.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Regultory approvals

As described elsewhere (4), this lupus surveillance project was conducted under a grant of authority from the MDCH as a public health surveillance activity, with Institutional Review Board exemptions and waiver for informed consent from the CDC, the MDCH, and the University of Michigan (UM).

Source population, catchment area, and surveillance period

The source population consisted of 2.4 million residents of the counties of Wayne (includes Detroit) and Wash-tenaw (includes Ann Arbor) in southeastern Michigan, comprising a mixed urban/rural population (57.7% white, 38.7% black, 3.7% other racial/ethnic groups according to 2003 US Census estimates) (3). Location of “usual residence” was determined according to the 2000 Census rules (5). To capture SLE cases receiving health care outside their residential county, the catchment area for case ascertainment also included neighboring Oakland County, as determined by a pilot analysis of data on health care utilization patterns (6). The surveillance period encompassed January 1, 2002 through December 31, 2004.

SLE definitions and verification of diagnosis

Primary analyses were based on classification of SLE according to fulfillment of the current research standard: ≥4 of 11 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE (7,8) (or, ACR definition). Secondary analyses used our rheumatologist definition, which was based on the consensus judgment of our team of 6 board-certified rheumatologist-investigators representing the major academic medical centers in southeastern Michigan. As detailed further in the data collection section below, in addition to data elements comprising the ACR classification criteria, we systematically ascertained data elements from other case definitions, including the Boston weighted criteria (9), as well as from validated SLE activity measures and components of the new Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria for the classification of SLE (10). In addition, free-text note fields were available for each organ system and included data on confounding diagnoses or other salient points substantiating the record. Thus, the judgment of the rheumatologists was based on the synthesis of medical history details beyond the ACR or other classification criteria. Based on the rheumatologist definition, some patients who satisfied fewer than 4 ACR criteria and had biopsy-proven lupus nephritis and/or additional objective features of SLE were considered to have SLE. The rheumatologist definition also excluded some patients who satisfied ≥4 ACR criteria but who had met subcriteria that could more likely be attributed to a comorbid illness, such as hepatitis C virus infection. If there was disagreement between the ACR and rheumatologist classifications, the record was reviewed independently by at least 2 physician-investigators to assure consensus on the rheumatologist definition that was recorded.

Case ascertainment

Multiple case-finding sources were used, including hospitals/health systems, private practice specialists (rheumatologists, nephrologists, and dermatologists), Medicaid claims, the US Renal Data System for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients with a diagnosis of SLE, and commercial laboratories. In addition, a random sample of primary care practices was taken in order to explore the utility of primary care practices for case finding, though this source did not yield adequate data for analysis. Case finding was customized to be compatible and as comprehensive as possible for each source/facility; queries were based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) codes for pathology reports, keyword/text searching of medical records, and/or other patient logs, as applicable (codes and keywords are listed in Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.38238/abstract).

Case ascertainment and abstraction in the source population was completed at 27 of 28 hospitals (96.4%), 59 of 67 rheumatologists (88.1%), 74 of 84 nephrologists (88.1%), and 50 of 86 dermatologists (58.1%). Of the 18 rheumatologists and nephrologists that were not included, ~20% had retired/closed practices since the surveillance period, 39% declined to participate, and the remainder were affiliated with larger health systems that we accessed. Of the dermatologists who were not included, the majority were not directly relevant to our surveillance program because of their area of subspecialization (e.g., cosmetic dermatology or Mohs surgery). In neighboring Oakland County, case ascertainment and abstraction were completed at an additional 10 hospitals and 20 private practices.

Data collection

Detailed sociodemographic and clinical data were collected (see Supplementary Table 2, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://online library.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.38238/abstract). Relevant clinical data included the ACR (7,8) and SLICC (10) classification criteria for SLE, components of validated SLE disease activity instruments (e.g., the SLE Disease Activity Index [SLEDAI] [11], the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Index [BILAG] [12], and the Systemic Lupus Activity Measure [SLAM] [13,14]), and ACR consensus definitions (neuropsychiatric lupus) (15). Data elements were selected based on an iterative process among a working group of >10 rheumatology/ public health faculty members. Clinical data included dates of SLE diagnosis and, for the major features of SLE (e.g., ACR criteria), both the date of onset and the source of the data (physician observation, medical document, or patient report), potentially confounding diagnoses (e.g., hepatitis C virus infection), common SLE medications, and the diagnosis recorded in the patient's medical chart. For some data elements (e.g., antiphospholipid antibodies), the results of multiple assessments were recorded.

Data were collected by abstractors who had completed standardized, rigorous training, which included completion of pilot abstractions that were reviewed in detail by the rheumatologist-investigators against the source documentation. Continual quality assurance of data abstraction included reabstraction of 5% of the records, as well as physician review of all abstractions and provision of feedback. For each potential case, abstractors manually reviewed all available records. A medical record search engine (the Universal Medical Record Search Engine [UMERSE]) (16) was used when available to screen electronic records for keywords. Data were entered into a secure electronic data-capture system. Completed abstractions, representing the synthesis of data from all available sources, were reviewed in detail by at least one rheumatologist-investigator, who requested further information if necessary.

Statistical analysis

All cases contributed person-years to the prevalence numerators for each year (from diagnosis onward) of residence in the source population during 2002– 2004 and to the incidence numerators for the year of diagnosis (if during 2002–2004). Age-, sex-, and race-specific denominators for 2002–2004, by county in Michigan, were based on US Census data (the vintage 2009 bridged-race population files produced by the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau) (3,17). The race-bridging methodology is used to create comparability between multiple-race (31 race categories) and single-race (4 race categories) data collection systems (1). Crude and stratum-specific mean annual incidence and prevalence rates were computed per 100,000 person-years. Rates were estimated as the number of incident or prevalent cases divided by the relevant number of person-years, and exact 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were computed. Age-standardized rates were calculated using the direct method (using 5-year age bands), with weights based on the 2000 US Standard Population (18).

To estimate underascertainment of cases, capture– recapture analysis (19) was used to take account for the degree of overlap among multiple case-finding sources. Specifically, we fit log-linear models (20) assuming there was no “3-way” interaction of sources. Contingency tables were set up with count data for the number of cases uniquely identified for each source and for pairs of sources. Each of these cells represented a potential predictor in the models, which included each of the sources and interaction terms, and then nonsignificant interactions were removed from the final model (up to 9 pairs of 2-way interactions for the 5-source models, and up to 5 pairs of 2-way interactions for the 4-source models). Goodness-of-fit statistics were used to identify the best models based on Pearson's chi-square and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (21,22). The BIC includes 2 terms, the first corresponds to how well the data fit the model, and the second is a penalty for the model complexity. Thus, the BIC reflects the trade-off between model complexity and goodness-of-fit. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute), R (R Foundation), and Stata (StataCorp) software packages.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

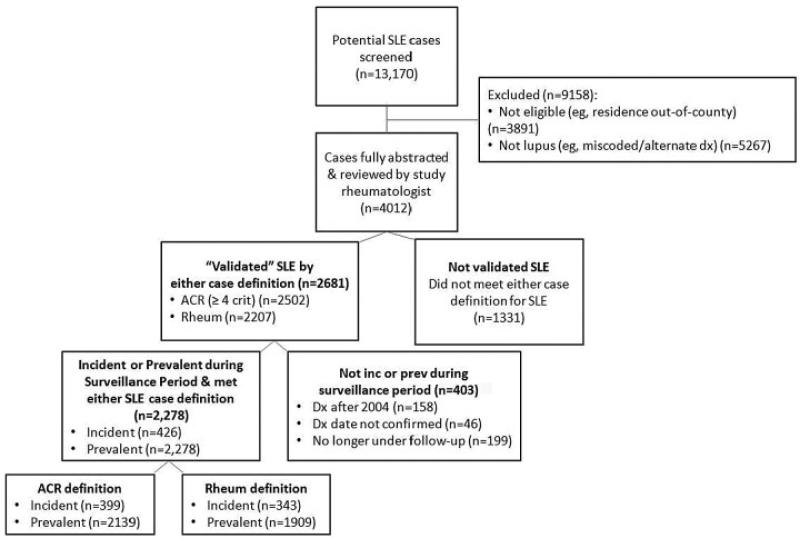

As depicted by the flow diagram in Figure 1, among the 13,170 potential cases screened, a total of 2,278 prevalent cases, with a subset of 426 incident cases, were confirmed as meeting eligibility criteria (residency and time period) and either the ACR or the rheumatologist definitions of SLE. A larger number of cases fulfilled the ACR definition as compared to the rheumatologist definition (2,139 versus 1,909) (Figure 1). The demographic features of the cases meeting the ACR definition were as follows: 1,957 (91.5%) female; 1,219 (57.0%) black, 820 (38.3%) white, 100 (4.7%) other/unknown race (Table 1). The vast majority of cases (2,124 of 2,278 [93.2%]) that were included in the Registry were ascertained by just 4 of the 6 case-finding source categories (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the ascertainment and verification of cases of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in the Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance program. For the category of not incident (inc) or prevalent (prev) during surveillance period, the prevalent cases included both newly diagnosed (incident) and existing cases (i.e., the incident cases are a subset of the prevalent cases). Dx = diagnosis; ACR = American College of Rheumatology; Rheum = rheumatologist.

Table 1.

Crude and age-standardized mean annual incidence and prevalence rates (per 100,000) of SLE in southeastern Michigan, 2002–2004, according to the ACR and rheumatologist case definitions, categorized by race/ethnicity and sex*

| ACR definition |

Rheumatologist definition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity, sex | No. of cases | Crude rate (95% CI) | Age-standardized rate (95% CI) | No. of cases | Crude rate (95% CI) | Age-standardized rate (95% CI) |

| Incidence | ||||||

| Overall† | 399 | 5.6 (5.0–6.2) | 5.5 (5.0–6.1) | 343 | 4.8 (4.3–5.3) | 4.7 (4.3–5.3) |

| Male | 54 | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 50 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) |

| Female | 345 | 9.3 (8.4–10.4) | 9.3 (8.3–10.3) | 293 | 8.0 (7.1–8.9) | 7.9 (7.0–8.9) |

| Black | 215 | 7.9 (6.9–9.0) | 7.9 (6.9–9.1) | 204 | 7.5 (6.5–8.5) | 7.5 (6.5–8.5) |

| Male | 25 | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 2.1 (1.3–3.0) | 26 | 2.1 (1.3–3.0) | 2.1 (1.3–3.0) |

| Female | 190 | 12.8 (11.1–14.8) | 12.8 (11.1–14.8) | 178 | 12.1 (10.4–14.0) | 12.0 (10.3–13.9) |

| White | 157 | 3.8 (3.2–4.4) | 3.7 (3.1–4.3) | 115 | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 2.7 (2.2–3.3) |

| Male | 24 | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) | 19 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) |

| Female | 133 | 6.3 (5.3–7.5) | 6.3 (5.2–7.4) | 96 | 4.6 (3.7–5.6) | 4.5 (3.7–5.5) |

| Prevalence | ||||||

| Overall† | 2,139 | 72.1 (70.1–74.1) | 72.8 (70.8–74.8) | 1,909 | 64.1 (62.3–66.0) | 64.6 (62.8–66.5) |

| Male | 182 | 12.4 (11.3–13.7) | 12.8 (11.7–14.1) | 177 | 12.2 (11.1–13.4) | 12.5 (11.4–13.8) |

| Female | 1,957 | 127.8 (124.2–131.5) | 128.7 (125.1–132.4) | 1,732 | 112.7 (109.3–116.2) | 113.4 (110.0–116.9) |

| Black | 1,219 | 105.8 (102.0–109.8) | 111.6 (107.7–115.6) | 1,142 | 98.2 (94.5–102.0) | 103.0 (99.2–106.9) |

| Male | 93 | 17.8 (15.5–20.2) | 19.3 (17.0–21.9) | 96 | 18.3 (16.0–20.8) | 19.9 (17.6–22.6) |

| Female | 1,126 | 181.6 (174.8–188.7) | 186.3 (179.4–193.4) | 1,046 | 167.0 (160.4–173.7) | 170.5 (164.0–177.4) |

| White | 820 | 48.7 (46.6–50.9) | 47.5 (45.5–49.7) | 679 | 40.8 (38.9–42.8) | 39.8 (37.9–41.7) |

| Male | 76 | 8.8 (7.5–10.1) | 8.7 (7.5–10.1) | 612 | 7.9 (6.7–9.2) | 7.8 (6.6–9.1) |

| Female | 744 | 88.0 (84.0–92.1) | 86.7 (82.8–90.8) | 67 | 73.2 (69.6–76.9) | 72.1 (68.5–75.9) |

| Asian/PI | 25 | 27.1 (20.7–34.9) | 24.9 (18.7–32.4) | 21 | 22.2 (16.4–29.3) | 20.8 (15.2–27.7) |

| Male | 3 | 5.3 (2.0–11.6) | 4.4 (1.4–10.4) | 3 | 5.3 (2.0–11.6) | 4.3 (1.4–10.4) |

| Female | 22 | 49.6 (37.3–64.9) | 45.0 (33.3–59.5) | 18 | 39.5 (28.6–53.2) | 36.9 (26.3–50.1) |

| Hispanic‡ | 39 | 33.6 (27.3–40.9) | 42.1 (35.0–50.2) | 36 | 31.9 (25.8–39.0) | 40.1 (33.1–47.9) |

| Male | 7 | 11.5 (6.8–18.2) | 14.9 (9.3–22.1) | 7 | 11.5 (6.8–18.2) | 14.9 (9.3–22.1) |

| Female | 32 | 58.4 (46.3–72.5) | 71.4 (58.0–86.8) | 29 | 54.8 (43.1–68.5) | 67.6 (54.7–82.9) |

Rates are per 100,000 persons. SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Represents the entire population, including persons whose race/ethnicity was not known. The numerator for this category is larger than the sum of the individual subsets, since it includes persons of other racial/ethnic classifications. Incidence estimates according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) definition are not presented for other racial/ethnic groups because of the small numbers: 7 Asian/Pacific Islander (PI), 1 American Indian/Alaska Native, and 9 Hispanic patients. For the 19 patients of unknown race, there were 8 incident cases according to the ACR definition; rates were not calculated for this subset since the appropriate population denominator could not be determined. For prevalent cases according to the ACR definition, 3 were American Indian/Alaska Natives and 72 were of unknown race.

Hispanic/Latino ethnicity is recorded separately from race; therefore, persons in this ethnicity category are also represented in the race categories.

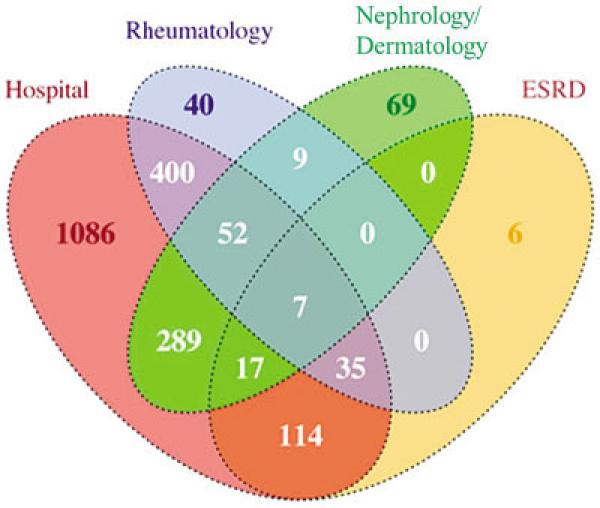

Figure 2.

Venn diagram depicting the overlap of cases identified by the 4 categories of case-finding sources used in the primary capture– recapture models. This diagram corresponds to unique prevalent cases classified as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) definition. Capture– recapture modeling was performed using both 4-source and 5-source models; the models that used the 4 case-finding sources presented in this Venn diagram were determined to fit the data best and, thus, represent our primary capture–recapture modeling. The majority of cases in the registry (2,124 of 2,278 [93.2%]) meeting the ACR or rheumatologist definitions were ascertained from these 4 case-finding source categories. (The 2 case-finding sources that were not retained in the primary models were Medicaid and laboratory.) Based on the capture–recapture analysis of prevalent SLE cases meeting the ACR criteria, we estimated that an additional 7 prevalent SLE cases were in the source population (Wayne and Washtenaw Counties, Michigan, 2002–2004) but were not ascertained in the Registry. ESRD = end-stage renal disease (data from US Renal Data System).

Incidence rates

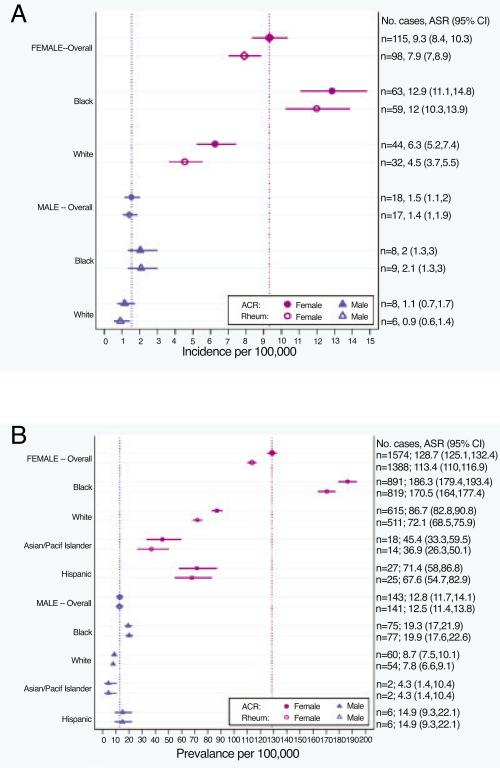

According to the ACR definition, 399 cases were newly diagnosed during 2002–2004 (average of 133 new cases annually). Crude and age-standardized rates according to both SLE definitions, stratified by sex and race, are detailed in Table 1 and Figure 3A. By the ACR definition, the age-standardized incidence rates were as follows: for the overall population, 5.5 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 5.0–6.1); for the female population, 9.3 (95% CI 8.3–10.3); and for the male population, 1.5 (95% CI 1.1–2.0) (incidence ratio of females to males 6:1). The age-standardized incidence rate among black patients was 7.9 (95% CI 6.9–9.1) and among white patients was 3.7 (95% CI 3.1–4.3). The incidence for black females (12.8 [95% CI 11.1–14.8]) was higher than for white females (6.3 [95% CI 5.2–7.4]). Incidence rates were higher among black male patients as compared to white male patients, although they did not reach statistical significance (likely due to the small number of male patients). The numbers of incident cases for other racial/ethnic groups (7 Asian/ Pacific Islander, 1 American Indian/Alaska Native, and 9 Hispanic patients) were small; thus, the incidence rates for these groups are not presented due to statistical imprecision. Incidence patterns by race and sex were similar according to the secondary rheumatologist definition, although the rates were slightly lower.

Figure 3.

A and B, Forest plots of the age-standardized incidence (A) and prevalence (B) rates of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and rheumatologist (Rheum) case definitions, categorized by sex and race/ethnicity. Values are the point estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Vertical dotted lines indicate the point estimates for the overall male and female rates according to the ACR definition. Numbers shown on the right y-axis are the average annual number of SLE cases during 2002–2004, with the age-standardized rate (ASR) per 100,000 persons and 95% CI. Pacif = Pacific.

Capture–recapture modeling (applied to the ACR definition) using 4- and 5-source models was performed to assess the extent of underascertainment of cases by our surveillance program. Based on goodness-of-fit statistics, our primary capture–recapture models incorporated the following 4 case-finding sources: hospitals, rheumatology practices, nephrology/dermatology practices, and US Renal Data System/ESRD database. From this 4-source model, we estimated that we were unable to identify 2 (95% CI 1–4) incident SLE cases in the source population. Adjustment for this low level of underascertainment did not materially affect the incidence rates.

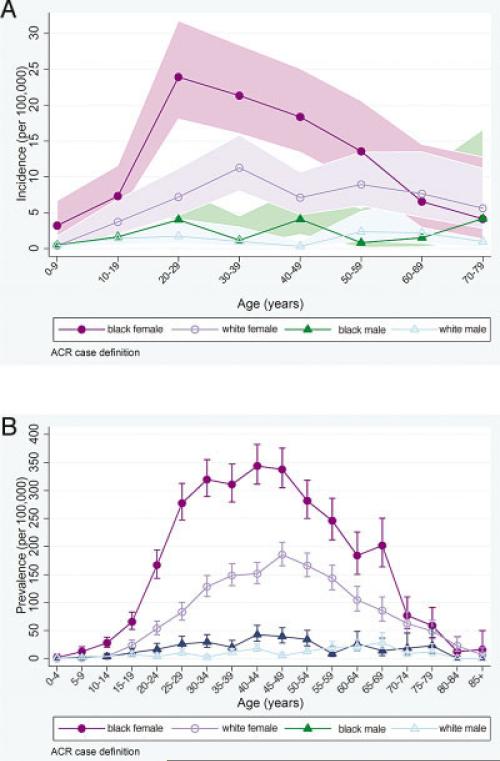

The mean ± SD age at diagnosis in the ACR-defined incident cases was 39.3 ± 16.6 years and was significantly younger in black female patients (37.1 ± 14.5 years) as compared to white female patients (43.9 ± 16.9 years; P < 0.001), but was similar in black male patients (36.4 ± 18.6 years) as compared to white male patients (41.0 ± 19.9 years). Age-specific incidence rates (Figure 4A) in black female patients rose from early childhood and peaked in the twenties, while the rates for white female patients increased more gradually and plateaued from the thirties through fifties. Among males, the incidence rates appeared more constant across age groups.

Figure 4.

A and B, Age-specific average annual incidence (A) and prevalence (B) rates (per 100,000 persons) of systemic lupus erythematosus, according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) case definitions, categorized by sex and race/ethnicity, in southeastern Michigan, 2002–2004. Values are the point estimates; shading in A and bars in B represent 95% confidence intervals.

Prevalence rates

From a total of 2,139 ACR-defined prevalent cases, the annual average number of person-years contributed during 2002–2004 was 1,708. The prevalence rates, including sex- and race-specific rates for both case definitions, are detailed in Table 1 and Figure 3B. The age-standardized prevalence was 72.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 70.8–74.8) overall, 128.7 (95% CI 125.1–132.4) for females, and 12.8 (95% CI 11.7–14.1) for males. The age-standardized prevalence among black persons was more than double that for white persons, including among black females (186.3 [95% CI 179.4–193.4]) as compared to white females (86.7 [95% CI 82.8–90.8]). The estimated prevalence rates for Asians/Pacific Islander and Hispanic persons were lower than for black persons, although the small number of cases in these groups limits further comparisons.

While the age-specific prevalence for both black and white females peaked in the fourth decade of life, from ages 10–69 years, black females had a significantly higher prevalence than did white females or males of either racial/ethnic group (Figure 4B), demonstrating that the disproportionate disease burden among black females pertained across the majority of the lifespan. Based on our primary 4-source capture–recapture analyses (described above), we estimated that 7 (95% CI 5–10) prevalent SLE cases in the source population were missed. Adjustment for this low level of underascertainment did not materially affect the prevalence rates.

Clinical characteristics

The proportion of patients with prevalent SLE who satisfied each of the 11 individual ACR criteria was similar in patients identified by either definition of SLE, but the rheumatologist definition included a larger number of patients with ESRD (Table 2). Black patients had a higher proportion of renal involvement (2.2-fold) and ESRD (3.4-fold) as compared to white patients. In the subset of ACR-defined incident cases with renal disease, the mean ± SD age at SLE diagnosis was younger among black patients (34.4 ± 14.9 years) as compared to white patients (41.9 ± 21.3 years; P = 0.05).

Table 2.

Clinical manifestations among the prevalent cases of SLE, according to the ACR and rheumatologist case definitions*

| ACR definition |

Rheumatologist definition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical manifestation | No. (%) of overall group (n = 2,139) | No. (%) of black cases (n = 1,215) | No. (%) of white cases (n = 820) | No. (%) of overall group (n = 1,909) | No. (%) of black cases (n = 1,146) | No. (%) of white cases (n = 675) |

| Malar rash | 1,055 (49.3) | 520 (42.7) | 483 (58.9)† | 923 (48.4) | 482 (42.2) | 397 (58.5)† |

| Discoid rash | 520 (24.3) | 392 (32.2)† | 111 (13.5) | 456 (23.9) | 350 (30.7)† | 93 (13.7) |

| Photosensitivity | 1,036 (48.4) | 505 (41.4) | 483 (58.9)† | 850 (44.5) | 442 (38.7) | 370 (54.5)† |

| Oral ulcers | 892 (41.7) | 462 (37.9) | 395 (48.2)† | 726 (38.0) | 405 (35.5) | 295 (43.5)† |

| Arthritis | 1,514 (70.8) | 875 (71.8) | 570 (69.5) | 1,314 (68.8) | 793 (69.4) | 461 (67.9) |

| Serositis | 938 (43.9) | 559 (45.9) | 347 (42.3) | 837 (43.8) | 522 (45.7) | 288 (42.4) |

| Renal disorder | 682 (31.9) | 494 (40.5)† | 154 (18.8) | 671 (35.2) | 495 (43.4)† | 145 (21.4) |

| ESRD | 231 (10.8) | 187 (15.3)† | 37 (4.5) | 254 (13.3) | 204 (17.9)† | 42 (6.2) |

| Neurologic disorder | 394 (18.4) | 265 (21.7)† | 115 (14.0) | 354 (18.5) | 243 (21.3)† | 99 (14.6) |

| Hematologic disorder | 1,411 (66.0) | 814 (66.8) | 529 (64.5) | 1,247 (65.3) | 737 (64.5) | 453 (66.7) |

| Immunologic disorder | 1,436 (67.1) | 864 (71.0)† | 503 (61.3) | 1,372 (71.9) | 841 (73.6)† | 462 (68.0) |

| Antinuclear antibody | 2,012 (94.1) | 1,172 (96.1)† | 750 (91.5) | 1,818 (95.2) | 1,102(96.5)† | 635 (93.5) |

Prevalent cases consisted of both new (incident) and existing cases of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) during the years 2002–2004. Clinical manifestations consisted of the 11 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE plus end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The overall group represents the entire population, including persons whose race/ethnicity was not known. The numerator for this category is larger than the sum of the individual subsets, since it includes persons of other racial/ethnic classifications.

Significantly higher proportion of cases with the clinical manifestation between the black and white subgroups.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiologic data are fundamental to our understanding of the risk and burden of disease in the population. However, such data are challenging and resource intensive to derive in a fragmented health care system and for diseases such as SLE, in which a heterogeneous constellation of clinical and laboratory features is necessary to establish a diagnosis. Surveillance outside of the tertiary care setting is imperative for capturing the full spectrum of SLE, in order to identify cases receiving health care in other settings. In the sociodemographically diverse MILES source population of 2.4 million, there were, on average, 133 new cases and 1,708 prevalent cases of SLE annually during 2002–2004, yielding age-standardized incidence and prevalence estimates per 100,000 persons of 5.5 and 72.8, respectively. Using more complete case-finding sources, we were able to quantify at a new level of statistical precision the higher risk and burden of SLE among women and minorities in the general population of the US.

The majority of previously available data on the epidemiology of SLE were derived from predominantly homogeneous populations of European descent. As reviewed elsewhere (23), previous North American and European estimates of the prevalence of SLE in recent years (1995–2008) have varied widely (from 32 to 150 per 100,000 persons) (23). Weighted mean estimates for SLE based on studies published over the 3 earlier decades (for the years 1965–1995) were 7.3 for the incidence and 23.8 for the prevalence (24). Though caution should be exercised when comparing results between studies that may be heterogeneous in terms of methodologies and population structures, in relation to the weighted data, our rates in Michigan appear to be similar for SLE incidence, though 3-fold higher for SLE prevalence. The larger prevalence-to-incidence ratio in our population, coupled with the higher prevalence range in the more recent review, suggests that prevalence may be increasing, in part due to improved survival, over the last 2 decades. The net migration in Michigan (i.e., the balance of in- and out-migration) from 1985 through the end of the surveillance period was relatively stable, including that among young adults (a reasonable proxy for a “healthy” population subset). Thus, it does not appear that the premise for improved survival was an artifact of migration patterns (25). However, the possibility that persons with preexisting lupus migrated into the source population in order to be more proximate to medical care cannot be excluded.

We found a female-to-male incidence ratio of 6.2:1 and a female-to-male prevalence ratio of 10.1:1; hence, males accounted for a higher proportion of newly diagnosed cases as compared to existing cases in the overall population, a pattern that pertained to both black patients and white patients. Studies examining race have documented higher rates in persons of African descent: a study from Allegheny County, PA (for the years 1985–1990) found an ~3-fold incidence of SLE among black females versus white females (9.2 versus 3.5 per 100,000 persons) (1); another study of the adult population in Birmingham, UK (for 1992) found the prevalence among African-Caribbeans to be 206 per 100,000 persons, as compared with 27.7 per 100,000 persons overall (26). In our population, black persons had the highest risk and burden of SLE, with a 2.1-fold higher incidence and a 2.3-fold higher prevalence (1 in 537 black females) than white persons, ratios somewhat smaller than those reported elsewhere. The ability to compare disease patterns in other racial and ethnic groups is limited by the small numbers of these minorities in our geographic region, though our data suggest that black persons have a higher prevalence of SLE than Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic persons.

As shown by the age-specific incidence rates, SLE began earlier in the reproductive years in black females. In late childhood, there was already a trend for black girls to have an increased incidence compared to white girls, and in the 20–50-year range, there was an early incidence peak in black women, as compared to statistically lower levels that plateaued among white women. However, after the average age of menopause (~51 years of age in the US) (27), the incidence rates in black versus white women did not differ significantly. In contrast to recent European studies describing a peak incidence among females around the age of menopause (28,29), the observation of peak incidence in this Michigan population during the reproductive years is driven by the early onset in black females. Higher genetic load (number of SLE-susceptibility risk alleles) has been associated with earlier disease onset among African American, but not European American, SLE patients (30), and gene–environment interactions may further underlie observed racial differences in the natural history of this disease.

This study has several limitations. First, it was based on review of medical records, rather than direct patient examination, as most population-based epidemiologic studies must. Second, race and ethnicity were ascertained from records, not self-reports, which would be the gold standard. Misclassification may be a particular concern for persons of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, since many medical records systems do not assess Hispanic ethnicity as a separate variable from race, which in theory, could lead to underestimation. Third, although we tried to reach all targeted health care sources, a few (see the case ascertainment section above) did not permit access, and the slow cooperation of others necessitated active record reviews through 2011, requiring increased allocation of resources in order to complete the planned surveillance activities. The nonparticipating sites did not appear to differ systematically from the participating sites in terms of the demographics of the populations served or other discernible features. Fourth, we have likely underestimated incident and prevalent cases, as there may be undiagnosed cases in the community that have not reached the health care system for screening and diagnosis, and other cases may have received care outside the catchment area. However, the capture–recapture analyses estimated that our surveil-lance program missed only 7 cases in the source population, pointing to highly effective methods of defining catchment areas (based on a pilot analysis of health care utilization patterns) and case ascertainment. Fifth, we were unable to enlist the systematic cooperation of primary care providers for even more comprehensive findings, but the interactions we did have suggested that primary care practices are likely to refer SLE patients and are therefore unlikely to represent a large source of additional cases.

This study also has several strengths. First, it included multiple case-finding sources, including health care facilities in a county contiguous to the source population, which helped to ensure complete ascertainment in a mobile population. Other researchers have previously noted a substantial lack of overlap between administrative case-finding sources, particularly for prevalent SLE cases (31). Second, for each patient, there was comprehensive abstraction and synthesis of detailed clinical and laboratory data from multiple sources. With the public health authority from the MDCH enabling our access to all relevant records, a thorough profile could be constructed for the majority of patients. In some cases, the diagnosis of lupus could be confirmed only after combining data from several hospitals or physicians. Third, as noted above, the use of 2 analytical case definitions (ACR and rheumatologist definitions) independently confirmed the diagnoses in the majority of patients and accommodated the clinical uncertainty of classifying SLE. The rheumatologist rates may be considered to yield conservative estimates and, thus, serve as a validated “lower bound” for the estimation of SLE. Fourth, the collaboration with colleagues from the CDC, the Georgia Lupus Registry, and the respective state health departments for the methods and infrastructure development can serve as a prototype for the implementation of other SLE registries, which will enhance opportunities for comparison of SLE statistics across sites. Indeed, new registries based on this framework have been initiated in regions with greater representation of other minority groups (Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, and American Indian/Alaska Native groups).

Based on this comprehensive, population-based surveillance program, our data underscore substantial levels of confirmed SLE cases and considerable racial disparities in the epidemiology of SLE. Black persons had the highest risk and burden of SLE, the earliest age at diagnosis, and an increased proportion of renal disease and progression to ESRD. Such data support a focus of medical resources on early diagnosis and improved treatment of lupus nephritis in young black Americans.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following individuals (all from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) participated in the data collection and medical chart abstractions for the MILES program: Sarah Barnhart, Dr. Shivani Bhutani, Dr. Elizabeth Bodkin, Elizabeth Curry, Dr. Rufaidah Dabbagh, Ryan Fix, Dr. Sheeja Francis, Dr. Thomas Kallarackal-Malaikal, Lauren Levy, James Moon, Catherine Myles, Steven Nelson, Katie O'Connor, Amanda Rasnake, Emily Siegwald, Riley Turchetti, and Jessica Wong.

In addition, the authors thank the following individuals (from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, except where indicated otherwise): TingTing Lu and Martha Ganser for statistical support; Maggie Smith, Padma Vinukonda, and Kelly Ding for database management and informatics support; Nancy Laracey and Carol VanHuysen for program management; Ana Austin for regulatory support; Dr. David Hanauer for developing the capacity for electronic medical record search engine integration; Dr. Rajiv Saran for assistance with the US Renal Data System/ESRD data; Drs. David Fox, Timothy Laing, Michelle Jaffe, and the late Dr. MaryFran Sowers for providing guidance during the planning stages of the program; staff of the MDCH, including Glenn Copeland, Sarah Lyon-Callo, Dr. Violanda Grigorescu, Dr. Judi Lyles, and Karen Petersmarck; Drs. Sam Lim, Cristina Drenkard, and colleagues from the Georgia Lupus Registry for their continued collaboration; and the physicians and staff throughout southeastern Michigan who graciously facilitated the data collection activities.

The findings and conclusions reported herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Michigan Department of Community Health, or the National Institutes of Health.

Supported by cooperative agreements between the CDC and the Michigan Department of Community Health (U58/CCU522826 and U58/DP001441), the NIH (National Center for Research Resources grant UL1-RR-024986), and the Herbert and Carol and Amster Lupus Research Fund. Dr. Somers’ work was supported in part by the NIH (grant K01-ES-019909). Dr. Marder's work was supported in part by the NIH (grant K12-HD-001438).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Somers had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Somers, Marder, DeGuire, Gordon, Helmick, Dhar, Leisen, McCune.

Acquisition of data. Somers, Marder, Lewis, DeGuire, Dhar, Leisen, Shaltis, McCune.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Somers, Marder, Cagnoli, DeGuire, Gordon, Helmick, Wang, Wing, McCune.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA, Jr, Ramsey-Goldman R, LaPorte RE, Kwoh CK. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus: race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260–70. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman CH, Hiraki LT, Liu J, Fischer MA, Solomon DH, Alarcon GS, et al. Epidemiology and sociodemographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis among US adults with Medicaid coverage, 2000–2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:753–63. doi: 10.1002/art.37795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Postcensal estimates of the resident population of the United States for July 1, 2000-July 1, 2009, by year, county, age, bridged race, Hispanic origin, and sex (Vintage 2009). Prepared under a collaborative arrangement with the US Census Bureau. URL: http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/nvss/bridged_race.htm.

- 4.Lim SS, Drenkard C, McCune WJ, Helmick CG, Gordon C, DeGuire P, et al. Population-based lupus registries: advancing our epidemiologic understanding. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1462–6. doi: 10.1002/art.24835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Census Bureau. United States Census Residence rules: facts about Census 2000 residence rules. 2000 URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/resid_rules.html.

- 6.Wennberg J, Wennberg D. Dartmouth atlas of health care in Michigan. Dartmouth College; Hanover (NH): 2000. The geography of health care in Michigan. pp. 6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochberg MC. for the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American College of Rheumatology. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus [letter]. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costenbader KH, Karlson EW, Liang MH, Mandl LA. Defining lupus cases for clinical studies: the Boston Weighted Criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2545–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677–86. doi: 10.1002/art.34473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang DH. and the Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Derivation of the SLEDAI: a disease activity index for lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Symmons DP, Coppock JS, Bacon PA, Bresnihan B, Isenberg DA, Maddison P, et al. and Members of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG). Development and assessment of a computerized index of clinical disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Q J Med. 1988;69:927–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang MH, Socher SA, Roberts WN, Esdaile JM. Measurement of systemic lupus erythematosus activity in clinical research. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:817–25. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang MH, Socher SA, Larson MG, Schur PH. Reliability and validity of six systems for the clinical assessment of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1107–18. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACR Ad Hoc Committee on Neuropsychiatric Lupus Nomenclature. The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:599–608. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<599::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Universal Medical Record Search Engine Case studies: UMERSE and lupus screening. URL: http://www.umerse.com/casestudy04.html.

- 17.Ingram DD, Parker JD, Schenker N, Weed JA, Hamilton B, Arias E, et al. United States Census 2000 population with bridged race categories. Vital Health Stat2. 2003;135:1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health Standard populations (millions) for age-adjustment. URL: http://seer.can cer.gov/stdpopulations/index.html.

- 19.Wittes JT, Colton T, Sidel VW. Capture-recapture methods for assessing the completeness of case ascertainment when using multiple information sources. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27:25–36. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Working Group for Disease Monitoring and Forecasting Capture-recapture and multiple-record systems estimation I: history and theoretical development. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1047–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hook EB, Regal RR. Capture-recapture methods in epidemiology: methods and limitations. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:243–64. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper GS, Bynum MLK, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, Graham NM. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–43. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darga K. Fallacies that misinform our thinking about Michigan's population and economy. 2008 Jan 11;:1–33. URL: http://www.michigan.gov/documents/hal/lm_census_RevEstConf08-0111_221465_7.pdf.

- 26.Johnson AE, Gordon C, Palmer RG, Bacon PA. The prevalence and incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in Birmingham, England: relationship to ethnicity and country of birth. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:551–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gold EB, Bromberger J, Crawford S, Samuels S, Greendale GA, Harlow SD, et al. Factors associated with age at natural meno-pause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:865–74. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.9.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somers EC, Thomas SL, Smeeth L, Schoonen WM, Hall AJ. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United Kingdom, 1990–1999. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:612–8. doi: 10.1002/art.22683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonsson H, Nived O, Sturfelt G, Silman A. Estimating the incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in a defined population using multiple sources of retrieval. Br J Rheumatol. 1990;29:185–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/29.3.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb R, Kelly JA, Somers EC, Hughes T, Kaufman KM, Sanchez E, et al. Early disease onset is predicted by a higher genetic risk for lupus and is associated with a more severe phenotype in lupus patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:151–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.141697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernatsky S, Joseph L, Pineau CA, Tamblyn R, Feldman DE, Clarke AE. A population-based assessment of systemic lupus erythematosus incidence and prevalence—results and implications of using administrative data for epidemiological studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1814–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.