Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the two most common systemic autoimmune disorders, have both unique and overlapping manifestations. One feature they share is a significantly enhanced risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular (CV) disease that significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality. The primary mechanisms that drive CV damage in these diseases remain to be fully characterized, but recent discoveries indicate that distinct inflammatory pathways and immune dysregulation characteristic of RA and SLE likely play prominent roles. This review focuses on analyzing the major mechanisms and pathways potentially implicated in the acceleration of atherothrombosis [**AU: Should this be atherosclerosis for consistency?**] and CV risk in SLE and RA, as well as in the identification of putative preventive strategies that may mitigate vascular complications in systemic autoimmunity.

Keywords: inflammation, cardiovascular, interferon, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, autoimmunity

INTRODUCTION

Although atherosclerosis was traditionally viewed as a lipid-based disorder affecting the arteries, this theory has been significantly modified based on the increased understanding of the mechanisms promoting vascular damage. Indeed, inflammatory pathways appear to play key roles in development and propagation of atherosclerosis and the onset of acute coronary syndromes (1). A number of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders are associated with a significant increase in atherosclerotic cardiovascular (CV) risk. However, it has been less clear if the mediators that promote atherogenesis are shared by all chronic inflammatory conditions, or whether upstream disease-specific mechanisms cause premature CV disease (CVD) through distinct pathways that may eventually converge into a shared proatherogenic phenotype.

This review analyzes putative mechanisms of CVD in two of the most common systemic autoimmune diseases: rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Despite their differences in clinical presentation and pathogenesis, both diseases are associated with elevated CV risk that substantially increases morbidity and mortality (2, 3). Although some of the mechanisms that drive CVD in RA and SLE may be shared, we propose that each disease has specific immunological aberrations that provide a distinct milieu for atherosclerosis development. Furthering the understanding of specific atherogenic pathways in these diseases may also expand our knowledge of the various mechanisms that lead to CVD in the general population.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

RA is a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder that affects ~1% of the general population and damages synovial joints. Systemic and articular synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-17, play crucial roles in joint and end-organ damage in this disease. RA patients are more prone to develop atherosclerosis, associated with a markedly increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, as outlined below.

TNF: tumor necrosis factor [**AU: This (and other text in this font) is a glossary entry. In later proofs, glossary entries will appear in the margin instead of interrupting your text like this.**]

CVD Epidemiology

Although dramatic improvements in the care of RA patients have led to decreases in the incidence of joint destruction, the prevalence of CVD in these patients is 50% higher than in the general population, and represents the leading cause of mortality (4). CV risk in RA is comparable to the risk reported in patients with diabetes mellitus of similar disease duration (5). Like diabetic patients, RA patients are more likely to develop silent ischemia and sudden cardiac death (6). Further, CV events occur earlier in RA and are associated with a higher case fatality than in the general population (7).

Increased CV risk in RA is attributed to both traditional cardiac Framingham risk factors and systemic inflammation (4, 8). RA-specific factors might play prominent roles in decreased survival rates following an ischemic event; further, there is a clear correlation between RA disease duration and atherosclerosis severity (9). As such, RA is considered a significant independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease. Treatment with disease- modifying antirheumatic drugs improves CV outcomes in RA patients, and patients with higher classic inflammatory burden have enhanced CVD (8, 10). All these observations support an important role for RA-specific immune pathways in atherosclerosis development.

There is evidence that vascular damage accrual begins prior to the diagnosis of RA, and accelerates as the disease progresses. RA patients present with endothelial dysfunction (a known predictor of future atherosclerosis development) and increased subclinical atherosclerosis compared to age-matched controls (11, 12). Progression of carotid atherosclerosis is greatest within the first six years (13), but continues to worsen with disease duration (9). Endothelial function, assessed by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation , also worsens with disease duration (14). Autopsy reports indicate that RA may contribute to distinct types of vascular lesions, as blood vessels in this disease display heightened media and adventitial inflammation and increased vulnerable plaques (15), even if the number of lesions is not different from that seen in non-RA patients.

Several genetic polymorphisms have also been associated with increased risk of CVD in RA patients, but detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this review (see 16 for details).

Traditional Risk Factors and CV Risk in RA

Individuals with systemic inflammatory disorders such as RA have an overall increased frequency of traditional CV risk factors. In RA, smoking is considered an independent risk factor for disease development and is associated with disease activity and with synthesis of rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated protein (anti-CCP) antibodies, [**AU: OK?**] all of which may contribute to increased RA-associated CVD (17). However, smoking status has not been systematically linked to CV events in seropositive RA patients, indicating that an increase in CV mortality in this disease is not explained by confounding effects of tobacco use.

RF: rheumatoid factor

CCP: cyclic citrullinated peptide

A specific type of dyslipidemia occurs in RA and can precede arthritis diagnosis (18). This pattern is characterized by low levels of HDL and LDL cholesterol and raised triglycerides. Indeed, for RA patients, unlike the general population, CV events do not clearly track with elevated total cholesterol (19). Additionally, RA patients display increased prevalence of alterations in the composition and function of HDL, which may further contribute to CV risk. Levels of oxidized proinflammatory HDL are elevated in RA compared to healthy controls (20); this phenomenon may promote LDL oxidation, and foam cell formation and decrease reverse cholesterol transport (21, 22). The decreased antioxidant capacity of HDL in RA has been associated with decreased activity of paraoxonase, an antioxidant enzyme that circulates attached to HDL and prevents LDL oxidation (22).

HDL: high-density lipoprotein

LDL: low-density lipoprotein

Other metabolic abnormalities associated with vascular disease in the general population are more prevalent in RA patients than in controls. Examples include insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome (21, 23), which are associated with increased coronary calcification in this disease (23). Furthermore, clear evidence points to a role for TNF-α as a promoter of insulin resistance in RA (24). Consequently, the interactions of inflammatory pathways and traditional CV risk factors may amplify CV risk in RA.

Cytokines and CVD in RA

As inflammation and disease duration influence CVD development in RA (9), it is likely that elevated proinflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein, characteristic of RA, may play pathogenic roles in associated atherothrombotic CV events (Table 1). Anti-cytokine biologic therapy has become an important tool in the treatment of RA, but whether this will significantly alter CV events remains unclear.

Table 1.

Inflammatory cytokines involved in atherosclerosis and autoimmunity

| Cytokine | Atherosclerosis | Rheumatoid arthritis | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Increases adhesion molecules on endothelial surface Recruits inflammatory cells to vascular wall Promotes foam cell formation Promotes insulin resistance |

Involved in pathogenesis of arthritis Inhibition likely protective for CVD development |

May be elevated, potential role in lupus nephritis; correlates with CVD |

| IL-17 | Absence of IL-17 signaling is protective for atherosclerosis development in mice | Involved in pathogenesis of arthritis Predicts microvascular endothelial function and macrovascular compliance May have prothrombotic effects |

Elevated in SLE but link with CVD unknown |

| IL-6 | Increased in atherosclerotic plaques Accelerates atherosclerosis in mice Inhibition of signaling can reverse plaque Its blockade may have deleterious effects on lipids |

Involved in pathogenesis of arthritis Correlates with coronary calcium scores Likely contributes to abnormal lipid profiles |

Link to CVD unknown |

| Type I interferons | Increased in atherosclerotic plaques Enhances inflammatory cell activation and plaque destabilization |

Some patients may have elevated levels but role in RA-associated CVD is undefined | Plays a major role in SLE pathogenesis Contributes to endothelial dysfunction, poor vascular repair, platelet activation, foam cell formation and increased CV risk in SLE |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

TNF-α. TNF-α levels are increased in RA and correlate with the CVD (24). TNF-α may play important roles in the initiation and perpetuation of traditional atherosclerotic lesions in non-RA patients, as it increases endothelial cell (EC) surface adhesion molecules, levels of chemotactic proteins that promote mononuclear cell recruitment into the endothelial wall, and scavenger receptor expression on macrophages which exacerbates foam cell formation (25). Indeed, RA serum induces similar changes in macrophages and these changes are partially reversed by TNF-α- or IL-6-neutralizing antibodies, suggesting that these cytokines actively promote plaque development in RA (25). Lipid profiles, insulin resistance, endothelial function, and aortic compliance may improve with anti-TNF treatment, but whether these effects are sustained and significant remains unclear (26). A recent meta-analysis indicates a trend towards cardioprotection with anti-TNF biologics, [**AU: As meant?**] but significance was observed in cohort studies and not in randomized controlled trials, leaving the role of TNF in RA CVD still open for debate (27).

EC: endothelial cell

IL-17. IL-17 plays pathogenic roles in RA joint inflammation (28), and recent evidence also suggests a link with enhanced RA-associated CVD. IL-17 is a significant, independent predictor of lower microvascular endothelial function and macrovascular arterial compliance in RA patients with stable disease (29). Further, the combination of IL-17 and TNF-α is prothrombotic by inducing platelet aggregation and disrupting the balance between procoagulant and anticoagulant factors on ECs (30). A protective effect of IL-17 blockade on plaque burden has been described in atherosclerosis-prone mice (31). Thus, this cytokine may influence CVD development and acute events in the inflammatory milieu unique to RA.

IL-6. IL-6 levels are elevated in RA, and this cytokine significantly contributes to disease pathogenesis. IL-6 is also found in human atherosclerotic plaques (32), and can accelerate atherosclerosis in mice (33). Inhibition of IL-6 signaling via a soluble receptor can prevent plaque formation and reverse existing plaque (34). Importantly, increased IL-6 correlates with increased coronary calcium in RA patients, independent of Framingham risk factors (24). RA patients treated with tocilizumab, an IL-6- neutralizing antibody, have improvements in insulin sensitivity and lower lipoprotein (a) levels, which could contribute to decreased CV risk (35). However, as tocilizumab can significantly raise triglycerides, it is unclear if anti-IL-6 approaches will decrease CV risk.

Auto-Antibodies

The presence and/or levels of RF have been proposed as risk factors for CVD in the general population, even after controlling for inflammatory profiles (36). A strong correlation between the presence of RF and decreased endothelial function has been reported in patients with longstanding RA (29). Similar correlations have been made between anti-CCP antibodies and decreased endothelial function (37), presence of atherogenic risk factors (38), and increased carotid intima media thickness (39), though not in every study (29, 40). Anti-citrullinated vimentin antibodies have been associated with systemic inflammation and proatherogenic lipid profiles in RA (38). It is unclear whether other autoantibodies commonly seen in RA, including those to other specific citrullinated antigens, may specifically contribute to CVD risk.

Cellular Mediators

Aberrations in certain cellular populations in RA may also contribute to an elevated risk of CVD. CD4+CD28null T cells are expanded in RA and correlate with early indicators of CVD in these patients (41). Anti-TNF therapies restore CD28 expression, suggesting an additional mechanism by which TNF-α influences CVD development (41). The roles of other cell types in RA-associated CVD, such as B cells, neutrophils, and platelets, are currently under investigation and may provide additional targets for preventive strategies as well as disease treatments.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

SLE is a systemic autoimmune syndrome of unclear etiology with heterogeneous clinical manifestations that result from immune-mediated damage to various organs. Additionally, SLE patients display enhanced CV risk. Unlike those with RA, SLE patients typically present with a lower “classical inflammatory burden” (i.e., elevated C-reactive protein). This observation suggests that the variables that trigger accelerated atherosclerosis in SLE differ from typical proinflammatory factors reported in RA or in the general population.

CVD Epidemiology

A bimodal peak of mortality has been reported in SLE, with late increases in death often occurring as a result of premature atherosclerotic CVD (42). Enhanced vascular risk in SLE is particularly striking in young female patients, with up to 50-fold increases compared to age-matched controls (3, 43). As in RA, Framingham risk factors likely contribute to CVD in SLE; however, they cannot fully account for the increased propensity to vascular events (44). Atherosclerosis develops or progresses in 10% of SLE patients per year [**AU: OK?**]. Among other factors, this progression is associated with older age and longer disease duration, supporting the hypothesis that chronic exposure to SLE immune dysregulation promotes atherosclerosis (45).

Like in RA, vascular function abnormalities have been reported in the early course of SLE (46). Carotid plaque is prevalent in 21% of SLE patients under age 35 and in up to 100% of those over age 65 (47). Coronary arteries are commonly affected in SLE patients, with more than half displaying noncalcified plaques (48). Impairments in the coronary microvasculature flow reserve, even in patients with grossly normal coronary arteries, are also present (49). These findings indicate that microvascular damage and dysfunction are part of SLE-related CV pathology.

Traditional Risk Factors and CV Risk in SLE

The risk of CVD in SLE is greater than what can be explained by traditional Framingham risk factors (44). A recent study suggests that smoking may be the main traditional risk factor promoting increased CV risk in SLE (50). Given the high incidence of nephritis, hypertension is common in SLE patients and may contribute to CVD development.

Patients with SLE display higher prevalence of decreased HDL, increased LDL, VLDL, and triglycerides. These alterations may be related to abnormal chylomicron processing secondary to low levels of lipoprotein lipase (51). Like those with RA, SLE patients display higher levels of proinflammatory HDL, which is unable to protect LDL from oxidation, may promote endothelial injury, and is associated with increased subclinical atherosclerosis (52). Strikingly, levels of proinflammatory HDL are significantly higher in SLE than in RA, but it is unclear what mechanisms drive this increased lipid oxidation, compared to other diseases with significant inflammatory burden (20). Increased levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and antibodies to resultant protein adducts are described in SLE, correlate with disease activity, and may provide an environment for oxidation of lipoproteins that contribute to the atherogenic milieu (53).

Other metabolic abnormalities, such as microalbuminuria, insulin resistance, and increased homocysteine, are prevalent in SLE and may be involved in atherosclerosis and coronary calcification in this disease (54).

Cytokines and CVD in SLE

In contrast to RA, various classic inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) do not appear to play major pathogenic roles in the development and severity of SLE. Human and murine studies indicate that IFN-α, and potentially other type I IFNs, may be crucial in the pathogenesis and clinical course of SLE (55, 56). Our group and others recently reported that type I IFNs may play key roles in increased CV risk in SLE by enhancing thrombosis and endothelial damage, impairing vascular repair, and promoting foam cell formation and arterial inflammatory infiltrates that promote atherosclerotic plaque formation and progression.

Thrombosis

Platelets in SLE patients are activated and display increased markers of type I IFN signaling, and a link between exposure to IFN-α and platelet activation has been proposed (57). Further, SLE-prone mice exposed to increased levels of type I IFNs have accelerated thrombosis, enhanced platelet activation, and formation of leukocyte:platelet aggregates (58). These observations indicate that type I IFNs may be an additional factor that promotes thrombosis in this disease.

Abnormal Vascular Repair

Both Patients And Murine Models Of SLE display an imbalance between vascular damage and endothelial repair, which may accelerate plaque development. Circulating apoptotic ECs are increased in SLE, and this phenomenon correlates with endothelial dysfunction and generation of tissue factor (46). In addition, SLE patients have decreased levels and function of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and circulating angiogenic cells (CACs), both of which are implicated in effective vascular repair. Indeed, levels and/or function of these cells inversely correlate with the incidence of CVD and with risk factors of vascular damage in the general population (59). Human and murine SLE EPC/CACs are proapoptotic, even during quiescent disease, and they display decreased synthesis of proangiogenic molecules, and hampered capacity to incorporate into formed vascular structures and differentiate into mature ECs (60--62). Thus, patients with SLE have compromised repair of the damaged endothelium, likely leading to the establishment of a milieu that promotes the development of plaque.

EPC: endothelial progenitor cell

CAC: circulating angiogenic cell

We have reported that dysfunction of EPC/CAC differentiation in SLE is mediated by type I IFNs, as neutralization of these cytokines restores a normal EPC/CAC phenotype (61). The pathways by which IFN-α, and potentially other type I IFNs, mediates aberrant vascular repair may depend on repression of the proangiogenic factors IL-1β and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and on enhancement of inflammasome activation and upregulation of IL-18 and the antiangiogenic IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1-RA) (62, 63). Further supporting a role for type I IFNs in premature vascular damage in SLE, patients with high type I IFN signatures have lower endothelial function, as assessed by peripheral arterial tone (64) and by flow-mediated dilation measurements, as well as increased carotid intima media thickness and coronary calcification (65). Furthermore, there is evidence that an antiangiogenic phenotype is present in patients with SLE, manifested by decreased vascular density and increased vascular rarefaction in renal blood vessels in vivo, and associated with upregulation of IL-1-RA and decreased VEGF both in the kidney and in serum (61, 62).

Atherogenesis

Recent evidence indicates that type I IFNs may play important roles in atherosclerosis development in the general population, not just in SLE models. Type I IFN-induced signaling and IFN-α- producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are increased in atherosclerotic plaques (66, 67), and pDC depletion is protective in murine atherosclerosis models (68). Additionally, IFN-α sensitizes plaque-residing myeloid DCs (66), and activates plaque-residing CD4+ T cells to increase TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand expression, leading to cytotoxicity of plaque- stabilizing cells and potentially increasing plaque rupture risk (67).

pDC: plasmacytoid dendritic cell

The effects of type I IFNs on macrophage function may be particularly relevant to CVD development. In vivo exposure to IFN-α or IFN-β results in increased macrophage infiltration of vessels (58, 66). Additionally, priming of macrophages with IFN-α leads to enhanced oxidized LDL uptake and increased foam cell formation through modulation of scavenger receptors (69). Indeed, abrogation of type I IFN pathways in atherosclerosis-prone mice decreases plaque severity and macrophage and T cell infiltration (66). Finally, as mentioned above, type I IFN activity in serum correlates with subclinical atherosclerosis in SLE patients (58, 65).

The potential role of other cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-17, and TNF, in SLE-associated atherosclerosis needs to be further defined.

Autoantibodies

A central feature of SLE is the generation of numerous autoantibodies, some of which may potentially contribute to CVD development. The role of antiphospholipid (APL) antibodies in premature CVD remains a matter of debate. β2-glycoprotein I, which is abundant in vascular plaques, has been proposed to play an antiatherogenic role. APL antibodies are associated with abnormal ankle brachial index, and their titers correlate with carotid atherosclerosis (70, 71). However, not all studies clearly associate these antibodies with functional and/or anatomical abnormalities of the vessel wall (72). Nevertheless, because arterial thrombosis risk is enhanced in the presence of APL antibodies, their putative role in triggering unstable angina and acute coronary syndromes should be considered.

Autoantibodies against regulatory proteins in the atherogenic cycle in SLE may potentially contribute to CVD. For example, antibodies to the antiatherogenic HDL and one of its components, Apo A-1, are increased in SLE and rise with disease flares (73). Increased levels of antilipoprotein lipase antibodies in association with SLE disease activity have been reported and may contribute to increased triglyceride levels (74). Anti-Ro antibodies correlate with EPC/CAC dysfunction and IL-18 levels, suggesting they may have a role in CVD development in SLE (63). Complement activation and immune complex formation may contribute to atherogenesis in SLE, and this area remains to be further investigated.

Cellular Mediators

T and B cells, though crucial in SLE pathogenesis, have not been definitively linked to CV risk in SLE, and further investigation is needed regarding their role in this complication. CD4+ T cells may play a putative role in SLE-related CVD, [**AU: If you have “may,” do you need “putative”?**] as atherosclerosis-prone mice display increased vascular inflammation and CD4+ T cell infiltration in arterial plaques following bone marrow transplantation from SLE-prone donor mice (75).

A recent putative role for aberrant neutrophils in the pathogenesis of vascular damage in SLE has been proposed. A distinct subset of low-density granulocytes (LDGs) isolated from SLE patients displays enhanced capacity to synthesize proinflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs and induces EC cytotoxicity. Indeed, these cells produce sufficient amounts of type I IFNs to disrupt vascular repair, as LDG depletion restores the capacity of EPC/CACs to differentiate into mature ECs (76). Recent evidence from various groups implicates the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in the development of endothelial damage and atherothrombosis in non-SLE settings (77). Bactericidal proteins present in the NETs, including the cathelicidin LL-37, may be crucial in atheroma formation. Importantly, LDGs have an enhanced capacity to form NETs, and this promotes EC cytotoxicity (78). One could envision that aberrant NETosis could promote a feed-forward loop: pDCs are activated by complexes of DNA and bactericidal proteins present in the NETs, promoting enhanced type I IFN release in atheromatous plaques, thereby potentiating vascular damage (68). Furthermore, type I IFNs may promote NET formation. Future studies should focus on dissecting the mechanisms that lead to enhanced NET formation and their role in vascular damage and atherothrombosis in SLE.

PREVENTION OF CVD IN RA AND SLE PATIENTS

Because the etiologies of CVD in RA and SLE are still being discerned, effective targeting of pathologic mechanisms driving vascular events is not yet possible. It is also unclear if CV prevention strategies proven effective in diseases such as diabetes mellitus will be equally effective in RA or SLE. Thus, many RA or SLE patients with increased traditional CV risk factors are suboptimally treated (79).

Management of Traditional CV Risk Factors in RA and SLE

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends multiplying the CV risk calculated by conventional predictive scores by 1.5 for any RA patient with disease duration >10 years, positive RF or anti-CCP antibodies, or extra-articular manifestations, thus lowering the threshold for treatment (80). Additionally, EULAR recommends yearly monitoring and treatment of traditional CV risk factors including smoking, decreased activity level, oral contraceptive use, hormonal therapies, family history of cardiovascular events, hypertension, abnormal lipid profiles, and insulin resistance in both RA and SLE patients (80, 81). Until firm guidelines for CV risk reduction in these diseases are in place, we suggest a combination of common-sense targeting of traditional CV risk factors and appropriate disease treatment.

Statins can effectively lower total cholesterol in RA patients and significantly improve CV-related and all-cause mortality in this disease when used for primary, but not secondary, prevention of vascular events (82). Additionally, population-based studies suggest that mortality risk following CV events is higher in RA patients after discontinuation of statins, supporting a cardioprotective effect in this patient population (83).

The use of statins in SLE has not been extensively studied, but they appear to improve endothelial function in adult patients (84). Statin use trended toward a protective effect for carotid intima media thickness in pediatric SLE, but prophylactic statin use in children did not show a statistically significant benefit after three years of follow-up (85). Additionally, improvements in carotid atherosclerosis or coronary calcification with two years of statin use were not detected in adult SLE (86). It is hoped that future research will clarify the exact role that statins play in CV risk reduction in systemic autoimmune diseases and provide data on timing of drug use and combinations so that definitive guidelines can be established.

RA-Specific Treatment-Related Harms and Benefits

Several of the various medications used in RA treatment may have deleterious effects on CV outcomes. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use has been associated with increased CV risk in the general population and theoretically could play a contributing role in RA-associated CVD (87). However, long-term follow-up of RA patients has not shown an increased risk of CVD in NSAID users (88). Thus, the risks and benefits of NSAIDs in RA patients require further investigation. Additionally, steroids should be used judiciously to minimize CV risk secondary to their effects on metabolic parameters and blood pressure. However, because corticosteroids also have profound effects against inflammation and arthritis activity, further studies should attempt to better understand the impact of steroids on CVD in RA.

Although improvements in RA management have not clearly, reduced CV risk, specific medications frequently used in RA may provide important cardioprotective effects. There is clear evidence that the risk of CV events is reduced in RA patients who use methotrexate (89). This protective effect may be secondary, at least in part, to promotion of reverse cholesterol transport, inhibition of foam cell formation, and important anti-inflammatory effects of this drug (90). The antimalarial hydroxychloroquine, very frequently used for RA management, improves lipid profiles, and glycemic index and may decrease thrombosis risk (91).

As discussed above, the exact contribution of biologic agents to RA-associated CV risk remains unclear (27). Some studies have found no benefit in cardiac ischemic event rates (despite good anti-inflammatory response) in RA (92), whereas other reports indicate that anti-TNF modalities can reduce CV events in young patients (93) and decrease progression rates of subclinical atherosclerosis (13). It is also unclear if all anti-TNF strategies may play equivalent roles in CV prevention. Finally, data on newer biologics such as abatacept, tocilizumab, and rituximab are conflicting and preliminary; as such, randomized controlled studies are needed to poinpoint their role in CV risk reduction.

SLE-Specific Treatment-Related Harms and Benefits

Various studies indicate that early and appropriate treatment of immune dysregulation in SLE could be key to slowing CVD development and progression. Patients treated with lower doses of cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or corticosteroids had greater progression of CVD than those treated with higher doses (45). Further, aortic atherosclerosis risk is lower in SLE patients who have undergone treatment with cyclophosphamide than in SLE patients who have not (94). The role of corticosteroid treatment is complex and poorly understood, given potentially dual effects on CV risk that may depend on dose and time of exposure (47).

Although no studies have shown a reduced incidence of CV events with the use of antimalarials, an association between decreased prevalence of carotid plaque and these agents has been reported in SLE (95). A correlation between lack of antimalarial use and increased vascular stiffness in SLE has also been demonstrated (96). As antimalarials can weakly inhibit IFN-α production (97), it is possible that downregulation of this cytokine may be an additional mechanism explaining the survival benefits reported with antimalarial use in SLE. More research into the vascular effects of antimalarials is needed to understand their benefits and potential impact on atherosclerosis development.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), commonly used in SLE, may be potentially beneficial in atherosclerosis. MMF decreases atherosclerotic plaque inflammation prior to carotid endarterectomy and is able to reverse atherosclerosis and decrease vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis- prone mice with or without SLE background (98, 99). Whether this drug has a CV benefit in SLE patients should be addressed in future studies.

The role of novel biologics in CV prevention in SLE remains unknown. Currently, studies targeting type I IFNs, IL-17, and the various anti--B cell therapies are under way in SLE and other diseases. Long-term follow-up to assess atherosclerosis progression and CV risk biomarkers in these groups will be important to identify potential favorable effects. Given the recent observation that repression of IL-1 pathways is implicated in abnormal vascular repair in SLE (62), a note of caution is added with regards to the use of anakinra and other anti-IL-1 therapies in this disease as well as in other conditions where aberrant vasculogenesis is observed.

CONCLUSION

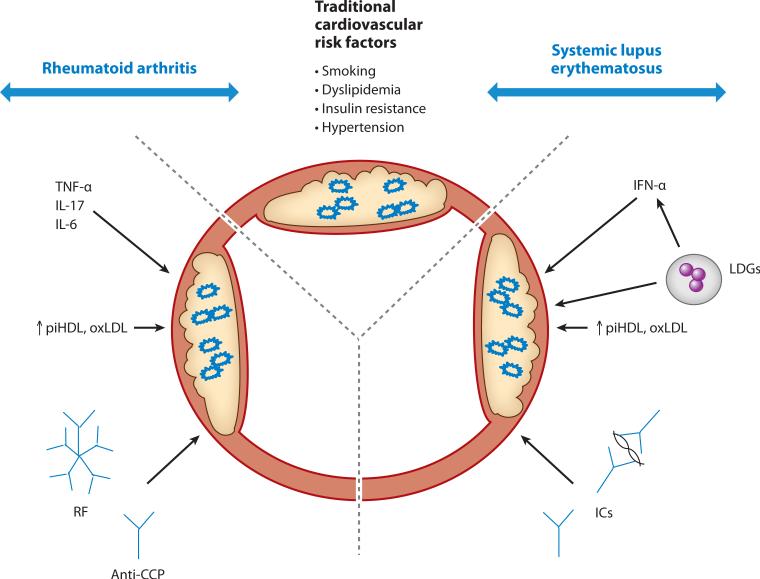

RA and SLE are associated with a significant increase in CV complications secondary to accelerated atherosclerosis. It appears that variables unique to each disease, in association with traditional CV risk factors, contribute to premature vascular damage (Figure 1). Further work should continue to focus on characterizing the precise molecular mechanisms leading to premature vascular damage, and larger and more rigorous studies should assess the individual contributions of various treatments and their effects on CVD in these diseases. It is also imperative that effective screening methods be identified and validated in these patient populations, so that specific guidelines for CV risk management are established. These approaches may lead to better preventive therapies to reduce or eliminate CV morbidity and mortality in both RA and SLE.

Figure 1.

An interplay between traditional cardiovascular risk factors and disease-specific traits leads to enhanced prevalence of atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Abbreviations: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; LDG, low density granulocyte; piHDL, proinflammatory high density lipoprotein; oxLDL, oxidized low density lipoprotein; RF, rheumatoid factor; CCP, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide; IC, immune complexs.

SUMMARY POINTS.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are characterized by significant increase in cardiovascular (CV) risk not fully explained by the Framingham risk equation.

TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-6 have pathogenic roles in RA and likely contribute to the development of premature atherosclerosis in this disease.

Type I interferons promote vascular damage in SLE through induction of pathways crucial in atherosclerosis progression.

Cytokines with important pathogenic roles in RA and SLE may also promote atherosclerosis in the general population.

Inflammatory factors in RA and SLE result in modification of lipoproteins, contributing to a proatherogenic environment.

The role of autoantibodies in CV risk in RA and SLE requires further investigation.

ACRONYMS AND DEFINITIONS LIST

[**AU: I've omitted three categories of acronyms from the glossary: those that are used very rarely (replaced by the spelled-out words), those that are used only in a discrete part of the text (defined parenthetically on first use), and those that are used so frequently that the reader has no time to forget what they mean.*]

- CAC

circulating angiogenic cell

- CCP

cyclic citrullinated peptides

- EC

endothelial cell

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

[**AU: Please insert your Disclosure of Potential Bias statement, covering all authors, here. If you have nothing to disclose, please confirm that the statement below may be published in your review. Fill out and return the forms sent with your galleys, as manuscripts CANNOT be sent for pageproof layout until these forms are received.**]

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1685–-95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myllykangas-Luosujärvi R. Shortening of life span and causes of excess mortality in a population-based series of subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1995;13:149–-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hak AE, Karlson EW, Feskanich D, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and the risk of cardiovascular disease: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61:1396–-402. doi: 10.1002/art.24537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1690–-97. doi: 10.1002/art.24092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamatelopoulos KS, Kitas GD, Papamichael CM, et al. Atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis versus diabetes: a comparative study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:1702–-8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:402–-11. doi: 10.1002/art.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodson N, Marks J, Lunt M, et al. Cardiovascular admissions and mortality in an inception cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with onset in the 1980s and 1990s. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005;64:1595–-601. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Innala L, Moller B, Ljung L, et al. Cardiovascular events in early RA are a result of inflammatory burden and traditional risk factors: a five year prospective study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13:R131. doi: 10.1186/ar3442. [**AU: only one page? Also for Ref 12 and others for this journal.**]

- 9.del Rincón I, O'Leary DH, Freeman GL, et al. Acceleration of atherosclerosis during the course of rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:354–-60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Doornum S, McColl G, Wicks IP. Accelerated atherosclerosis: an extraarticular feature of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:862–-73. doi: 10.1002/art.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergholm R, Leirisalo-Repo M, Vehkavaara S, et al. Impaired responsiveness to NO in newly diagnosed patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002;22:1637–-41. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000033516.73864.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannawi S, Haluska B, Marwick T, et al. Atherosclerotic disease is increased in recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a critical role for inflammation. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007;9:R116. doi: 10.1186/ar2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giles JT, Post WS, Blumenthal RS, et al. Longitudinal predictors of progression of carotid atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3216–-25. doi: 10.1002/art.30542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Llorca J, Gonzalez-Gay M. Correlation between endothelial function and carotid atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis patients with long-standing disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13:R101. doi: 10.1186/ar3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aubry M-C, Maradit-Kremers H, Reinalda MS, et al. Differences in atherosclerotic coronary heart disease between subjects with and without rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2007;34:937–-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan MJ. Cardiovascular complications of rheumatoid arthritis: assessment, prevention, and treatment. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2010;36:405–-26. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe F. The effect of smoking on clinical, laboratory, and radiographic status in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2000;27:630–-37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2012;24:171–-76. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834ff2fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Semb AG, Kvien TK, Aastveit AH, et al. Lipids, myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the Apolipoprotein-related Mortality RISk (AMORIS) Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:1996–-2001. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMahon M, Grossman J, FitzGerald J, et al. Proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein as a biomarker for atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2541–-49. doi: 10.1002/art.21976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rho YH, Chung CP, Oeser A, et al. Interaction between oxidative stress and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is associated with severity of coronary artery calcification in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:1473–-80. doi: 10.1002/acr.20237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charles-Schoeman C, Lee YY, Grijalva V, et al. Cholesterol efflux by high density lipoproteins is impaired in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200493. Epub ahead of print. [**AU: Add volume number and pagespan when known**]

- 23.Chung CP, Avalos I, Oeser A, et al. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: association with disease characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007;66:208–-14. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.054973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rho YH, Chung CP, Oeser A, et al. Inflammatory mediators and premature coronary atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61:1580–-85. doi: 10.1002/art.25009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashizume M, Mihara M. Atherogenic effects of TNF-α and IL-6 via up-regulation of scavenger receptors. Cytokine. 2012;58:424–-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daïen CI, Duny Y, Barnetche T, et al. Effect of TNF inhibitors on lipid profile in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:862–-68. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnabe C, Martin BJ, Ghali WA. Systematic review and meta-analysis: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:522–-29. doi: 10.1002/acr.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar S, Fox DA. Targeting IL-17 and Th17 cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2010;36:345–-66. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marder W, Khalatbari S, Myles JD, et al. Interleukin 17 as a novel predictor of vascular function in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:1550–-55. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.148031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hot A, Lenief V, Miossec P. Combination of IL-17 and TNFα induces a pro-inflammatory, pro-coagulant and pro-thrombotic phenotype in human endothelial cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:768–-76. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Es T, van Puijvelde GHM, Ramos OH, et al. Attenuated atherosclerosis upon IL-17R signaling disruption in LDLr deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;388:261–-65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schieffer B, Schieffer E, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, et al. Expression of angiotensin II and interleukin 6 in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques: potential implications for inflammation and plaque instability. Circulation. 2000;101:1372–-78. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huber SA, Sakkinen P, Conze D, et al. Interleukin-6 exacerbates early atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999;19:2364–-67. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.10.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuett H, Oestreich R, Waetzig GH, et al. Transsignaling of interleukin-6 crucially contributes to atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:281–-90. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.229435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz O, Oberhauser F, Saech J, et al. Effects of inhibition of interleukin-6 signalling on insulin sensitivity and lipoprotein (a) levels in human subjects with rheumatoid diseases. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomasson G, Aspelund T, Jonsson T, et al. Effect of rheumatoid factor on mortality and coronary heart disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:1649–-54. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.110536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hjeltnes G, Hollan I, Førre Ø , et al. Anti-CCP and RF IgM: predictors of impaired endothelial function in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2011;40:422–-27. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2011.585350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Barbary AM, Kassem EM, El-Sergany MAS, et al. Association of anti-modified citrullinated vimentin with subclinical atherosclerosis in early rheumatoid arthritis compared with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide. J. Rheumatol. 2011;38:828–-34. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerli R, Bocci EB, Sherer Y, et al. Association of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies with subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008;67:724–-25. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.073718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pereira I, Laurindo I, Burlingame R, et al. Auto-antibodies do not influence development of atherosclerotic plaques in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:416–-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerli R, Schillaci G, Giordano A, et al. CD4+CD28− T lymphocytes contribute to early atherosclerotic damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Circulation. 2004;109:2744–-48. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131450.66017.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urowitz MB, Bookman AA, Koehler BE, et al. The bimodal mortality pattern of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J. Med. 1976;60:221–-25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, et al. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997;145:408–-15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Grodzicky T, et al. Traditional Framingham risk factors fail to fully account for accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2331–-37. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2331::aid-art395>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roman MJ, Crow MK, Lockshin MD, et al. Rate and determinants of progression of atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3412–-19. doi: 10.1002/art.22924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajagopalan S, Somers E, Brook R, et al. Endothelial cell apoptosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a common pathway for abnormal vascular function and thrombosis propensity. Blood. 2004;103:3677–-83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manzi S, Selzer F, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of carotid plaque in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:51–-60. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<51::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiani AN, Vogel-Claussen J, Magder LS, et al. Noncalcified coronary plaque in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 2010;37:579–-84. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Recio-Mayoral A, Mason J, Kaski J, et al. Chronic inflammation and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients without risk factors for coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 2009;30:1837–-43. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gustafsson J, Simard J, Gunnarsson I, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012;14:R46. doi: 10.1186/ar3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borba EF, Bonf E, Vinagre CG, et al. Chylomicron metabolism is markedly altered in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1033–-40. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1033::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McMahon M, Grossman J, Skaggs B, et al. Dysfunctional proinflammatory high-density lipoproteins confer increased risk of atherosclerosis in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2428–-37. doi: 10.1002/art.24677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang G, Pierangeli SS, Papalardo E, et al. Markers of oxidative and nitrosative stress in systemic lupus erythematosus: correlation with disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2064–-72. doi: 10.1002/art.27442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mok C, Poon W, Lai J, et al. Metabolic syndrome, endothelial injury, and subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2010;39:42–-49. doi: 10.3109/03009740903046668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baechler E, Batliwalla F, Karypis G, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2610–-15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim T, Kanayama Y, Negoro N, et al. Serum levels of interferons in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1987;70:562–-69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lood C, Amisten S, Gullstrand B, et al. Platelet transcriptional profile and protein expression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: up-regulation of the type I interferon system is strongly associated with vascular disease. Blood. 2010;116:1951–-57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thacker SG, Zhao W, Smith CK, et al. Type I interferons modulate vascular function, repair, thrombosis and plaque progression in murine models of lupus and atherosclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 doi: 10.1002/art.34504. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1002/art.34504 [**AU: Add volume number and pagespan when known**]

- 59.Schmidt-Lucke C, Rossig L, Fichtlscherer S, et al. Reduced number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells predicts future cardiovascular events: proof of concept for the clinical importance of endogenous vascular repair. Circulation. 2005;111:2981–-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Westerweel P, Luijten RKMAC, Hoefer I, et al. Haematopoietic and endothelial progenitor cells are deficient in quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007;66:865–-70. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Denny MF, Thacker S, Mehta H, et al. Interferon-alpha promotes abnormal vasculogenesis in lupus: a potential pathway for premature atherosclerosis. Blood. 2007;110:2907–-15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thacker S, Berthier C, Mattinzoli D, et al. The detrimental effects of IFN-α on vasculogenesis in lupus are mediated by repression of IL-1 pathways: potential role in atherogenesis and renal vascular rarefaction. J. Immunol. 2010;185:4457–-69. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kahlenberg JM, Thacker SG, Berthier CC, et al. Inflammasome activation of IL-18 results in endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2011;187:6143–-56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee P, Li Y, Richards H, et al. Type I interferon as a novel risk factor for endothelial progenitor cell depletion and endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3759–-69. doi: 10.1002/art.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Somers EC, Zhao W, Lewis EE, et al. Type I interferons are associated with subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goossens P, Gijbels MJJ, Zernecke A, et al. Myeloid type I interferon signaling promotes atherosclerosis by stimulating macrophage recruitment to lesions. Cell Metab. 2010;12:142–-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niessner A, Sato K, Chaikof EL, et al. Pathogen-sensing plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulate cytotoxic T-cell function in the atherosclerotic plaque through interferon-alpha. Circulation. 2006;114:2482–-89. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Döring Y, Manthey H, Drechsler M, et al. Auto-antigenic protein-DNA complexes stimulate plasmacytoid dendritic cells to promote atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2012;125:1673–-83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.046755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li J, Fu Q, Cui H, et al. Interferon-α priming promotes lipid uptake and macrophage-derived foam cell formation: a novel link between interferon-α and atherosclerosis in lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:492–-502. doi: 10.1002/art.30165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baron MA, Khamashta MA, Hughes GRV, et al. Prevalence of an abnormal ankle-brachial index in patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome: preliminary data. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005;64:144–-46. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.016204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ames PRJ, Margarita A, Alves JD, et al. Anticardiolipin antibody titre and plasma homocysteine level independently predict intima media thickness of carotid arteries in subjects with idiopathic antiphospholipid antibodies. Lupus. 2002;11:208–-14. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu165oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gresele P, Migliacci R, Vedovati MC, et al. Patients with primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and without associated vascular risk factors present a normal endothelial function. Thromb. Res. 2009;123:444–-51. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Neill S, Giles I, Lambrianides A, et al. Antibodies to apolipoprotein A-I, high-density lipoprotein, and C-reactive protein are associated with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:845–-54. doi: 10.1002/art.27286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodrigues CEM, Bonfá E, Carvalho JF. Review on anti-lipoprotein lipase antibodies. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2010;411:1603–-5. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.07.028. [**AU: Please check this ref**]

- 75.Braun N, Wade N, Wakeland E, et al. Accelerated atherosclerosis is independent of feeding high fat diet in systemic lupus erythematosus--susceptible LDLr−/− mice. Lupus. 2008;17:1070–-78. doi: 10.1177/0961203308093551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Denny M, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, et al. A distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils isolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induces vascular damage and synthesizes type I IFNs. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3284–-97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:15880–-85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2011;187:538–-52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Toms TE, Panoulas VF, Douglas KM, et al. Statin use in rheumatoid arthritis in relation to actual cardiovascular risk: evidence for substantial undertreatment of lipid-associated cardiovascular risk? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:683–-88. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.115717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peters MJL, Symmons DPM, McCarey D, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:325–-31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.113696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mosca M, Tani C, Aringer M, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for monitoring patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in clinical practice and in observational studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:1269–-74. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sheng X, Murphy MJ, MacDonald TM, et al. Effectiveness of statins on total cholesterol and cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2012;39:32–-40. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Impact of statin discontinuation on mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis---a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/acr.21643. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1002/acr.21643 [**AU: Add volume number and pagespan when known**]

- 84.Ferreira GA, Navarro TP, Telles RW, et al. Atorvastatin therapy improves endothelial-dependent vasodilation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: an 8 weeks controlled trial. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1560–-65. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schanberg LE, Sandborg C, Barnhart HX, et al. Atherosclerosis prevention in pediatric lupus erythematosus I. Use of atorvastatin in systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:285–-96. doi: 10.1002/art.30645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Petri MA, Kiani AN, Post W, et al. Lupus Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (LAPS). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:760–-65. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.136762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goodson NJ, Brookhart AM, Symmons DPM, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use does not appear to be associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: results from a primary care based inception cohort of patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009;68:367–-72. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Micha R, Imamura F, Wyler von Ballmoos M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of methotrexate use and risk of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011;108:1362–-70. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reiss AB, Carsons SE, Anwar K, et al. Atheroprotective effects of methotrexate on reverse cholesterol transport proteins and foam cell transformation in human THP-1 monocyte/macrophages. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3675–-83. doi: 10.1002/art.24040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morris SJ, Wasko MCM, Antohe JL, et al. Hydroxychloroquine use associated with improvement in lipid profiles in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:530–-34. doi: 10.1002/acr.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ljung L, Simard JF, Jacobsson L, et al. Treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and the risk of acute coronary syndromes in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:42–-52. doi: 10.1002/art.30654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Al-Aly Z, Pan H, Zeringue A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α blockade, cardiovascular outcomes, and survival in rheumatoid arthritis. Transl. Res. 2011;157:10–-18. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roldan C, Joson J, Sharrar J, et al. Premature aortic atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a controlled transesophageal echocardiographic study. J. Rheumatol. 2010;37:71–-78. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roman M, Shanker B-A, Davis A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:2399–-406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Selzer F, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Fitzgerald S, et al. Vascular stiffness in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hypertension. 2001;37:1075–-82. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.4.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kalia S, Dutz JP. New concepts in antimalarial use and mode of action in dermatology. Dermatol. Ther. 2007;20:160–-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van Leuven SI, van Wijk DF, Volger OL, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil attenuates plaque inflammation in patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:231–-36. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Leuven SI, Mendez-Fernandez YV, Wilhelm AJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil but not atorvastatin attenuates atherosclerosis in lupus-prone LDLr−/− mice. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:408–-14. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]