Abstract

Within their natural habitat, plants are subjected to a combination of abiotic conditions that include stresses such as drought and heat. Drought and heat stress have been extensively studied; however, little is known about how their combination impacts plants. The response of Arabidopsis plants to a combination of drought and heat stress was found to be distinct from that of plants subjected to drought or heat stress. Transcriptome analysis of Arabidopsis plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress revealed a new pattern of defense response in plants that includes a partial combination of two multigene defense pathways (i.e. drought and heat stress), as well as 454 transcripts that are specifically expressed in plants during a combination of drought and heat stress. Metabolic profiling of plants subjected to drought, heat stress, or a combination of drought and heat stress revealed that plants subject to a combination of drought and heat stress accumulated sucrose and other sugars such as maltose and gulose. In contrast, Pro that accumulated in plants subjected to drought did not accumulate in plants during a combination of drought and heat stress. Heat stress was found to ameliorate the toxicity of Pro to cells, suggesting that during a combination of drought and heat stress sucrose replaces Pro in plants as the major osmoprotectant. Our results highlight the plasticity of the plant genome and demonstrate its ability to respond to complex environmental conditions that occur in the field.

The study of abiotic stress in plants has advanced considerably in recent years. However, the majority of experiments testing the response of plants to changes in environmental conditions have focused on a single stress treatment applied to plants under controlled conditions. In contrast, in the field, a number of different stresses can occur simultaneously. These may include conditions such as high irradiance, low water availability, extreme temperature, or high salinity and may alter plant metabolism in a novel manner that may be different from that caused by each of the different stresses applied individually. The response of plants to abiotic stresses in the field may therefore be very different from that tested in the laboratory (Cushman and Bohnert, 2000; Mittler et al., 2001; Zhu, 2002).

Drought and heat stress represent an excellent example of two different abiotic stresses that occur in the field simultaneously, especially in semi-arid or drought-stricken areas (Mittler et al., 2001; Moffat, 2002; Rizhsky et al., 2002). Although drought and heat stress have been extensively studied (Vierling, 1991; Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 1996; Miernyk, 1999; Queitsch et al., 2000), relatively little is known about how their combination impacts plants. A number of studies examined the effect of a combination of drought and heat stress on the growth and productivity of maize, barley, sorghum, and different grasses. It was found that a combination of drought and heat stress had a significantly higher detrimental effect on the growth and productivity of these plants and crops compared to each of the different stresses applied individually (Savage and Jacobson, 1935; Craufurd and Peacock, 1993; Savin and Nicolas, 1996). In maize, resistance to a combination of drought and heat stress is a well-known breeding target (Heyne and Brunson, 1940). Furthermore, a combination of drought and heat stress was found to alter the physiological status of grasses and other plants, to inhibit photosynthesis, and to result in the accumulation of end products of lipid peroxidation (Perdomo et al., 1996; Jagtap et al., 1998; Jiang and Huang, 2001).

Initial studies in tobacco suggested that the molecular response of plants to a combination of drought and heat stress is distinct from that of plants subjected to each of these stresses applied individually. Thus, the steady-state level of a number of transcripts, elevated during drought or heat stress, was reduced during a combination of drought and heat stress, and a small number of transcripts were specifically expressed during a combination of drought and heat stress (Rizhsky et al., 2002). Despite these findings, the number of transcripts tested in tobacco was relatively small (170 transcripts), and the scale of the plant's response to this stress combination remained largely unknown.

In this study we performed an initial analysis of the molecular and metabolic response of Arabidopsis to a combination of drought and heat stress. Our study revealed a new pattern of defense response in plants that includes a partial combination of two multigene defense pathways (drought and heat stress), as well as 454 transcripts that are specifically expressed in cells during a combination of drought and heat stress. In addition, plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress accumulated high levels of sucrose and other sugars, but did not accumulate Pro.

RESULTS

Physiological and Molecular Characterization of Arabidopsis Plants Subjected to a Combination of Drought and Heat Stress

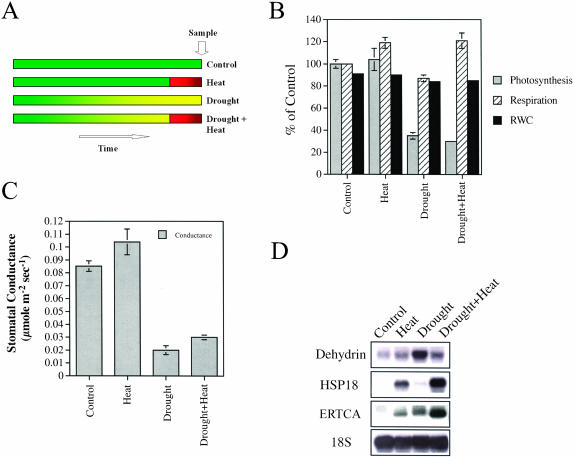

A combination of drought and heat stress was imposed on plants according to Rizhsky et al. (2002; Fig. 1A). As shown in Figure 1, the physiological and molecular response of Arabidopsis to a combination of drought and heat stress was very similar to that of tobacco (Rizhsky et al., 2002). Figure 1, B and C, shows that heat stress was accompanied by enhanced respiration and opening of stomata, whereas drought was accompanied by suppression of photosynthesis and closure of stomata (all measurements were performed with a Li-Cor 6400 [Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE] and refer therefore to rates of CO2 exchange between the leaf and the LI-6400-leaf chamber). In contrast, a combination of drought and heat stress resulted in the simultaneous enhancement of respiration and suppression of photosynthesis. Compared to tobacco, we could not, however, find a significant difference between the leaf temperature of plants subjected to heat stress or a combination of drought and heat stress (data not shown; Rizhsky et al., 2002). It should, however, be noted that although the same instrument was used to measure leaf temperature in both cases (i.e. a LI-6400), the variability in the measurements obtained with the smaller leaf of Arabidopsis was higher than that obtained with the larger tobacco leaf. In addition, the stomatal conductance of Arabidopsis leaves subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress (Fig. 1C) was not as low as that of tobacco (Rizhsky et al., 2002), suggesting that Arabidopsis plants might have been able to cool their leaves, at least partially, under the conditions used in our assay.

Figure 1.

Physiological and molecular characterization of Arabidopsis plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress. Plants were subjected to heat stress, drought, or a combination of heat stress and drought, as described in “Materials and Methods.” Results are presented as mean and standard deviation of three individual measurements. A, The experimental design for applying a combination of drought and heat stress to Arabidopsis. This design attempts to mimic the conditions that occur in the field in which a relatively prolonged period of drought (yellow) is accompanied by a brief period of heat stress (red; usually during midday to early afternoon). B, Photosynthetic activity and dark respiration, measured with a Li-Cor LI-6400 apparatus. C, Stomatal conductance, measured with a Li-Cor LI-6400 apparatus. D, Steady-state level of stress-response transcripts, measured by RNA gel blots. Ribosomal RNA (18S) was used to control for equal loading of RNA.

RNA-blot analysis using cDNA probes with a known expression pattern during a combination of drought and heat stress in tobacco (Rizhsky et al., 2002) revealed that, at least with these transcripts, a similar expression pattern could be found between Arabidopsis and tobacco (Fig. 1D). Thus, the steady-state level of transcripts encoding a specific dehydrin, that was elevated during drought, was not elevated to the same degree during a combination of drought and heat stress, and the steady-state level of transcripts encoding a specific small heat shock protein (HSP18) and an ethylene-response transcriptional coactivator (ERTCA) was strongly elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress.

Transcriptome Profiling of Arabidopsis Plants Subjected to a Combination of Drought and Heat Stress

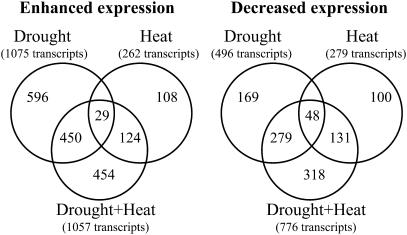

To examine changes in steady-state transcript level in leaves of Arabidopsis plants subjected to drought, heat stress, or their combination, we performed a transcriptome analysis of leaves using DNA arrays (ATH1 chips; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). As shown in Figure 2, there was very little similarity between the response of Arabidopsis to drought or heat stress. Out of 1,075 transcripts elevated during drought and 262 transcripts elevated during heat stress (cutoff of 1.5-fold log2), an overlap of only 29 transcripts was found. Similarly, an overlap of only 48 transcripts was observed between 496 and 279 transcripts decreased during drought or heat stress, respectively (cutoff of 1.5-fold log2). Compared to nonstressed plants, the steady-state level of 1,057 transcripts was elevated and the steady-state level of 776 transcripts was decreased during a combination of drought and heat stress. Out of the transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress, 479 were also elevated during drought and 153 were also elevated during heat stress (with a 29-transcript overlap). In addition to transcripts elevated in plants during drought or heat stress, the transcriptome of plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress contained 454 transcripts that were specifically elevated by this stress combination (cutoff of 1.5-fold log2). A similar situation was observed with transcripts decreased in plants during a combination of drought and heat stress, with 318 transcripts specifically decreased during this stress combination (Fig. 2). The transcriptome of plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress was therefore different from that of plants subjected to heat or drought stress.

Figure 2.

Venn diagrams showing the number of transcripts enhanced (left) or decreased (right) in plants in response to drought, heat stress, or a combination of drought and heat stress (compared to control nonstressed plants). Only transcripts with an increase or decrease in steady-state level of 1.5-fold (log2) over control unstressed plants are included. Results are presented as average of three independent experiments. RNA isolation and Affymetrix chip analysis were performed as described in “Materials and Methods.”

Table I shows the transcripts elevated in Arabidopsis subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress. Due to space limitations we included in the table only transcripts that were elevated fourfold or higher (cutoff of 2 log2). Additional tables listing transcripts elevated or decreased during drought, heat stress, or their combination (compared to control) can be found in the supplemental material to this manuscript (see www.plantphysiol.org). The table is divided and grouped into sections to represent transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress as well as drought or heat stress (A), transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress as well as heat stress (B), transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress as well as drought (C), and transcripts specifically elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress (D).

Table I.

Transcripts elevated in leaves of Arabidopsis plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress

| Gene No. | Transcript Name | Avg. | sd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Section A | |||

| At3g46230 | Heat shock protein 17 | 9.7 | 1.7 |

| At3g12580 | Heat shock protein 70 | 7.5 | 1.5 |

| At5g48570 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase | 5.9 | 0.4 |

| At5g59220 | ABA-induced protein phosphatase 2C | 5.3 | 0.2 |

| At3g24500 | Ethylene-responsive transcriptional coactivator | 4.3 | 0.4 |

| At2g47180 | Galactinol synthase | 3.8 | 0.3 |

| At3g53230 | CDC48-like endoplasmic reticulum ATPase | 3.6 | 0.5 |

| At3g16360 | Putative two-component phosphorelay mediator | 3.0 | 0.2 |

| At1g65660 | Step II splicing factor SLU7 | 2.9 | 0.1 |

| At3g24520 | Heat shock transcription factor HSF1 | 2.9 | 0.2 |

| At3g07770 | Putative heat shock protein | 2.6 | 0.3 |

| At1g22770 | Putative gigantea protein | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| At4g22590 | Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase | 2.5 | 0.2 |

| At5g28540 | Luminal binding protein | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| Section B | |||

| At5g59720 | Heat shock protein 18 | 10.0 | 0.6 |

| At4g25200 | Mitochondrion-small heat shock protein | 9.9 | 0.6 |

| At4g27670 | Heat shock protein 21 | 9.5 | 0.3 |

| At1g53540 | 17.6-kD Heat shock protein | 9.0 | 1.2 |

| At5g12020 | Heat shock protein 17.6-II | 8.9 | 0.4 |

| At5g12030 | Heat shock protein 17.6A | 8.3 | 1.8 |

| At4g10250 | Heat shock protein 22.0 | 7.3 | 1.3 |

| At2g29500 | Putative small heat shock protein | 6.5 | 0.2 |

| AtMg00520 | Maturase | 5.8 | 1.3 |

| At3g09640 | Putative ascorbate peroxidase | 5.7 | 0.6 |

| At1g74310 | Heat shock protein 101 (HSP101) | 5.5 | 0.3 |

| At5g12110 | Elongation factor 1B alpha-subunit | 5.1 | 0.7 |

| At4g03320 | Putative chloroplast import component | 5.0 | 0.5 |

| At5g52640 | Heat shock protein | 5.0 | 0.1 |

| At1g62510 | Similar to 14-kD Pro-rich protein | 4.7 | 0.1 |

| AtMg00160 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 | 4.4 | 0.3 |

| At1g72660 | Putative GTP-binding protein | 4.4 | 0.3 |

| At2g32120 | 70-kD Heat shock protein | 4.2 | 0.2 |

| AtMg00513 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 | 4.2 | 0.3 |

| AtMg00270 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6 | 4.1 | 0.5 |

| AtMg01360 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 | 3.8 | 0.2 |

| At2g20560 | Putative heat shock protein | 3.5 | 0.3 |

| At4g18280 | Gly-rich cell wall protein | 3.5 | 0.1 |

| AtMg00650 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4L | 3.4 | 0.1 |

| At5g37670 | Cytosolic class I small heat shock protein | 3.3 | 0.1 |

| AtMg00960 | Cytochrome c biogenesis | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| At1g07350 | Transformer-SR ribonucleoprotein | 3.2 | 0.2 |

| At5g25450 | Ubiquinol–cytochrome-c reductase | 3.2 | 0.2 |

| At3g48520 | Cytochrome P450-like protein | 2.7 | 0.1 |

| At1g26580 | Putative MYB family transcription factor | 2.7 | 0.3 |

| At5g67080 | Protein kinase-like protein | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| At1g09140 | Putative SF2/ASF splicing modulator | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| At5g58590 | Ran binding protein 1 homolog | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| AtMg00090 | Ribosomal protein L16 | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| At3g13470 | Chaperonin 60 beta | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| At1g09950 | Similar to Nicotiana tumor-related protein | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| At3g04000 | Short-chain type dehydrogenase/reductase | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| AtMg01080 | ATP synthase subunit 9 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At4g36010 | Thaumatin-like protein | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At3g59350 | Pto kinase interactor 1 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At5g14800 | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At5g58070 | Outer membrane lipoprotein | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At1g56340 | Calreticulin (crt1) | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| AtMg00180 | Cytochrome c biogenesis | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| Section C | |||

| At5g06760 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein | 8.9 | 0.1 |

| At5g59310 | Nonspecific lipid-transfer protein precursor | 8.4 | 0.3 |

| At1g22990 | Putative metal-binding protein | 8.0 | 1.0 |

| At5g13170 | Senescence-associated protein (SAG29) | 7.5 | 0.7 |

| At3g02480 | Unknown protein similar to pollen coat protein | 7.2 | 0.8 |

| At1g17020 | Fe(II)/ascorbate oxidase | 6.6 | 0.6 |

| At5g59320 | Nonspecific lipid-transfer protein precursor | 6.5 | 0.1 |

| At1g52690 | Late embryogenesis-abundant protein | 6.1 | 0.2 |

| At5g66400 | Dehydrin RAB18-like protein | 5.7 | 0.1 |

| At3g17520 | Unknown protein identical to LEA-like protein | 5.3 | 0.6 |

| At1g05100 | Putative NPK1-related MAP kinase | 5.1 | 0.2 |

| At1g07430 | Protein phosphatase 2C | 4.9 | 0.5 |

| At5g52300 | Low-temperature-induced 65-kD protein | 4.8 | 1.0 |

| At2g46680 | Homeodomain transcription factor (ATHB-7) | 4.6 | 0.3 |

| At5g29000 | Putative CDPK substrate protein 1 | 4.3 | 0.7 |

| At3g22840 | Early light-induced protein | 4.3 | 0.3 |

| At1g64660 | Met/cystathionine gamma lyase | 4.2 | 0.3 |

| At5g56500 | Rubisco chaperonin, 60 kD | 4.1 | 0.4 |

| At5g25110 | Ser/Thr protein kinase-like protein | 4.0 | 0.8 |

| At3g60350 | Arm repeat containing protein | 3.7 | 0.7 |

| At1g70300 | Potassium transporter | 3.7 | 0.1 |

| At1g02205 | Lipid transfer protein | 3.7 | 0.3 |

| At2g15480 | Putative glucosyltransferase | 3.6 | 0.7 |

| At1g56600 | Water stress-induced protein | 3.6 | 0.2 |

| At1g54100 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | 3.5 | 0.1 |

| At5g05410 | DREB2A | 3.5 | 0.2 |

| At4g15910 | Drought-induced protein-like | 3.5 | 0.2 |

| At1g03940 | Anthocyanin 5-aromatic acyltransferase | 3.5 | 0.2 |

| At1g62570 | Flavin-containing monooxygenase | 3.4 | 0.3 |

| At4g33150 | Lys-ketoglutarate reductase/saccharopine | 3.4 | 0.2 |

| At1g02205 | Receptor-like protein glossy1 | 3.4 | 0.4 |

| At1g57590 | Pectinacetylesterase precursor | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| At1g61800 | Glucose-6-phosphate/phosphate-translocator | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| At2g43590 | Putative endochitinase | 3.3 | 0.1 |

| At5g37540 | Nucleoid DNA-binding protein | 3.2 | 0.1 |

| At1g62290 | Aspartic protease | 3.2 | 0.1 |

| At5g53870 | Phytocyanin/early nodulin-like protein | 3.2 | 0.1 |

| At5g18820 | Chaperonin 60 alpha chain | 3.1 | 0.7 |

| At1g06430 | FtsH zinc dependent protease | 3.1 | 0.3 |

| At4g35940 | Putative Glu-rich protein | 3.1 | 0.9 |

| At5g52310 | Low-temperature-induced protein 78 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| At3g57520 | Probable imbibition protein | 3.1 | 0.1 |

| At2g46270 | G-box binding bZIP transcription factor | 3.1 | 0.3 |

| At1g21400 | Alpha keto-acid dehydrogenase | 3.1 | 0.1 |

| At4g20320 | CTP synthase-like protein | 3.0 | 0.8 |

| At3g55610 | Delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase | 3.0 | 0.1 |

| At2g33380 | Putative calcium-binding EF-hand protein | 3.0 | 0.1 |

| At2g33590 | Putative cinnamoyl-CoA reductase | 2.9 | 0.1 |

| At2g21590 | Putative ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase | 2.9 | 0.3 |

| At5g09590 | Heat shock protein 70 (Hsc70-5) | 2.9 | 0.3 |

| At3g57540 | Putative DNA binding protein | 2.8 | 0.2 |

| At4g24000 | Cellulose synthase catalytic subunit | 2.8 | 0.7 |

| At5g14270 | Kinase-like RING3 protein | 2.8 | 0.3 |

| At1g73040 | Jacalin | 2.8 | 0.4 |

| At4g35580 | NAM/CUC2-like protein | 2.8 | 0.5 |

| At3g13672 | Seven in absentia-like protein | 2.8 | 0.2 |

| At2g04030 | Putative heat shock protein | 2.7 | 0.1 |

| At1g51140 | Similar to phytochrome interacting factor 3 | 2.7 | 0.1 |

| At3g61890 | Homeobox-Leu zipper protein ATHB-12 | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| At1g56650 | Anthocyanin2 | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| At5g04530 | Fatty acid elongase 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase | 2.6 | 0.4 |

| At3g50970 | Dehydrin Xero2 | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| At4g12280 | Copper amine oxidase-like | 2.6 | 0.2 |

| At3g05650 | Putative disease resistance protein | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| At2g16890 | Putative glucosyltransferase | 2.6 | 0.4 |

| At1g52890 | Similar to NAM (no apical meristem) | 2.6 | 0.0 |

| At2g18050 | Histone H1 | 2.6 | 0.2 |

| At3g05640 | Putative protein phosphatase-2C | 2.6 | 0.3 |

| At4g21650 | Subtilisin proteinase | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| At1g11480 | Similar to eukaryotic initiation factor 4B | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| At5g22290 | NAM (no apical meristem)-like protein | 2.5 | 0.4 |

| At1g72770 | Protein phosphatase 2C (AtP2C-HA) | 2.5 | 0.2 |

| At3g05660 | Putative disease resistance protein | 2.5 | 0.4 |

| At5g57050 | Protein phosphatase 2C ABI2 | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| At5g40760 | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| At4g34000 | ABA responsive elements-binding factor (3) | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| At4g19600 | Putative protein cyclin C | 2.5 | 0.2 |

| At5g15450 | HSP100/ClpB | 2.5 | 0.2 |

| At1g11840 | Lactoylglutathione lyase-like protein | 2.5 | 0.0 |

| At5g42800 | Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| At1g22370 | UDP-glucose glucosyltransferase | 2.4 | 0.2 |

| At5g63370 | Protein kinase | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| At1g36730 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5 | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| At3g08860 | Beta-Ala-pyruvate aminotransferase | 2.4 | 0.2 |

| At5g01600 | Ferritin 1 precursor | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| At3g52850 | Vacuolar sorting receptor homolog/AtELP1 | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| At4g17030 | Allergen-like protein | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| At5g05110 | Cys proteinase inhibitor-like protein | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| At3g25230 | Rotamase FKBP (ROF1) | 2.3 | 0.3 |

| At3g23920 | Beta-amylase | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At2g29630 | Putative thiamin biosynthesis protein | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At2g20330 | Putative WD-40 repeat protein | 2.3 | 0.2 |

| At4g23050 | Ser/Thr kinase MAP3K | 2.3 | 0.4 |

| At4g39210 | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase | 2.3 | 0.2 |

| At2g29300 | Putative tropinone reductase | 2.3 | 0.3 |

| At5g25390 | AP2 domain containing protein | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At2g47470 | Putative protein disulfide-isomerase | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At3g59820 | Leu zipper-EF-hand protein | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At5g60360 | Cys proteinase | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At4g30470 | Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At4g35300 | Putative sugar transporter protein | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At3g19100 | CDPK-related kinase | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At5g65260 | Poly(A)-binding protein II-like | 2.2 | 0.4 |

| At5g23050 | Acetyl-CoA synthetase-like protein | 2.2 | 0.3 |

| At5g07920 | Diacylglycerol kinase (ATDGK1) | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At4g04020 | Putative fibrillin | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At3g20500 | Purple acid phosphatase | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At1g67360 | Stress-related protein | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At5g53120 | Spermidine synthase | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At4g19230 | Cytochrome P450 | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At1g64550 | ABC transporter protein | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| At1g62710 | Beta-VPE | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At5g24800 | Transcription factor light-induced CPRF-2 | 2.1 | 0.3 |

| At1g48000 | myb-related transcription factor | 2.1 | 0.6 |

| At1g73680 | Feebly-like protein | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| At5g48030 | DnaJ protein-like | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| At1g30500 | Transcription factor | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| At5g62190 | RNA helicase | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At1g56170 | Transcription factor | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| At1g79560 | FtsH protease, chloroplast | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At3g06400 | Putative ATPase (ISW2-like) | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| At3g11270 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit S12 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At1g64140 | Similar to putative disease resistance protein | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At5g10930 | Ser/Thr protein kinase SNFL3 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At5g51070 | ATP-dependent Clp protease (ClpD) | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At5g02620 | Ankyrin-like protein | 2.0 | 0.4 |

| At3g19170 | Metalloprotease 1 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At5g53400 | Similar to nuclear movement protein nudC | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At4g23670 | Putative major latex protein 1 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At4g30490 | Putative ATPase | 2.0 | 0.4 |

| At5g17220 | Glutathione S-transferase | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At4g35790 | Putative protein phospholipase D | 2.0 | 0.3 |

| Section D | |||

| At1g52560 | Chloroplast-small heat shock protein | 6.7 | 0.8 |

| At1g71000 | Heat shock protein DnaJ | 4.8 | 1.4 |

| At5g59330 | Nonspecific lipid-transfer protein | 4.7 | 0.9 |

| At2g26150 | Putative heat shock transcription factor | 4.0 | 1.7 |

| At4g28350 | Lectin receptor-like Ser/Thr kinase | 3.7 | 0.8 |

| At3g11020 | DREB2B transcription factor | 3.6 | 1.8 |

| At1g32560 | Late-embryogenesis abundant protein | 3.4 | 1.7 |

| At1g04220 | Putative beta-ketoacyl-CoA synthase | 3.3 | 0.5 |

| At2g34355 | Nodulin-like protein | 3.1 | 0.6 |

| At4g25000 | Alpha-amylase | 3.1 | 0.3 |

| At5g15250 | FtsH protease | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| At2g42270 | Putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase | 2.9 | 0.3 |

| At1g17665 | Dehydrogenase-like protein | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| At1g02300 | Cathepsin B-like Cys protease | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| At3g03470 | Putative cytochrome P450 | 2.6 | 0.2 |

| At5g66110 | atfp6-like protein | 2.5 | 0.5 |

| At4g02430 | Similar to alternative splicing factor ASF | 2.5 | 0.4 |

| At1g14040 | Polytropic retrovirus receptor | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| At5g49990 | Permease | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| At5g43920 | WD-repeat protein-like | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| At2g40350 | AP2 domain transcription factor | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| At2g14120 | Dynamin-like protein | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| At3g50980 | Dehydrin-like protein dehydrin Xero2 | 2.3 | 0.4 |

| At1g78670 | Gamma glutamyl hydrolase | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| At1g47960 | Similar to invertase inhibitor | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At2g43570 | Endochitinase isolog | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| At1g21460 | Similar to nodule development protein | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At4g01120 | GBF2, G-box binding factor | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At1g07720 | Fatty acid elongase 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase | 2.2 | 0.0 |

| At2g15880 | Related to disease resistance Pro-rich | 2.2 | 0.8 |

| At1g15550 | Gibberellin 3 beta-hydroxylase | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At1g77510 | Putative thioredoxin | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At4g28450 | SOF1-like protein (rRNA processing) | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| At4g33490 | Nucellin-like protein | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| At3g62090 | Putative phytochrome-associated protein 3 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| At3g12860 | Putative nucleolar protein | 2.1 | 1.2 |

| At1g61580 | Ribosomal protein | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At1g04980 | Disulfide isomerase-related protein | 2.1 | 0.3 |

| At5g58770 | Dehydrodolichyl diphosphate | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| At1g10050 | Putative xylan endohydrolase | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| At5g54080 | Homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| At2g32920 | Putative protein disulfide isomerase | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At2g38530 | Putative nonspecific lipid-transfer protein | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| At1g80110 | Similar to PP2 lectin polypeptide | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| At4g24280 | Heat shock 70 protein | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At4g30960 | Ser/Thr protein kinase | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| At3g54820 | Aquaporin MIP-like protein | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At2g07750 | Putative RNA helicase | 2.0 | 1.4 |

| At3g10410 | Putative Ser carboxypeptidase | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| At5g65110 | Acyl-CoA oxidase | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At3g23990 | Mitochondrial chaperonin hsp60 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At5g24870 | RING finger-like protein RING-H2 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

| At3g62560 | Small GTP-binding protein | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At3g13784 | Beta-fructofuranosidase | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| At3g44880 | Lethal leaf-spot 1 homolog Lls1 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At5g57900 | SKP1 interacting partner 1 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

| At5g04810 | Salt-inducible protein | 2.0 | 0.1 |

Changes in steady-state transcript abundance in plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress. Results are presented as fold-difference in steady-state transcript level (log2) over control unstressed plants. Only transcripts with a known (or putative) function and an expression level of fourfold or higher (2 log2) are shown. Accession numbers are given to each transcript on left. The known or putative function of each transcript is given on right. RNA preparation and analysis by Affymetrix chips are described in “Materials and Methods.” Transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress, as well as drought or heat stress, are indicated in A; transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress, as well as heat stress, are indicated in B; transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress, as well as drought, are indicated in C; and transcripts specifically elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress are indicated in D. sd, Standard deviation.

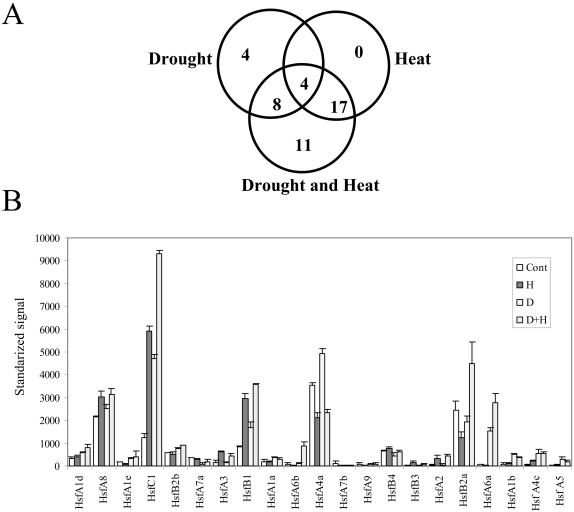

Among the transcripts elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress as well as heat stress (B) were many transcripts encoding mitochondrial proteins such as different subunits of NADH dehydrogenase and cytochrome c oxidase. The expression of these transcripts correlated with the enhanced respiratory activity detected in plants subjected to heat stress or a combination of drought and heat stress (Fig. 1B). As expected, the expression of a large number of transcripts encoding HSPs was elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress. However, not all HSPs elevated during heat stress were also elevated during drought or a combination of drought and heat stress. Thus, the steady-state level of 4 transcripts encoding HSPs was specifically elevated during drought, and the steady-state level of 11 transcripts encoding HSPs was specifically elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress (Fig. 3A; Table I; supplemental material). Because the expression of HSPs is controlled by the activity of heat shock transcription factors (HSFs; Czarnecka-Verner and Gurley, 2000; Nover et al., 2001), we examined the expression pattern of all 21 Arabidopsis HSFs. As shown in Figure 3B, the expression pattern of HSFs during a combination of drought and heat stress was different from that during drought or heat stress. Differences were mainly focused on the degree of expression of HsfC1, the presence of HsfA6a (not found in cells during heat stress, but elevated during drought), and the presence of HsfA2 and HsfA3 (elevated during heat stress but not drought). Interestingly, the expression of a HSF previously reported to be elevated in cells during light stress (HsfA7a; Pnueli et al., 2003) was not elevated in cells during drought, heat stress, or their combination.

Figure 3.

Steady-state transcript level of Arabidopsis transcripts encoding HSPs and HSFs in leaves of plants subjected to drought, heat stress, or a combination of drought and heat stress. Results are presented as average of three independent experiments. A, A Venn diagram showing the number of HSPs elevated during drought, heat stress, or a combination of drought and heat stress (cutoff 1.5-fold log2). B, Expression level of all Arabidopsis HSFs during drought, heat stress, and a combination of drought and heat stress. RNA isolation and Affymetrix chip analysis were performed as described in “Materials and Methods.” Cont, Control; D, drought; H, heat stress; D+H, a combination of drought and heat stress.

Another defense enzyme previously reported to be controlled by HSFs and elevated during heat stress, ascorbate peroxidase (Storozhenko et al., 1998; Panchuk et al., 2002; Pnueli et al., 2003), was also elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress. The function of this enzyme, i.e. removing reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI; Mittler, 2002), may be important for cell protection during a combination of drought and heat stress. The steady-state level of additional transcripts involved in ROI detoxification and ROI signaling was also elevated in cells during drought and a combination of drought and heat stress (Table IC). These included transcripts involved in glutathione metabolism, ferritin, and an NPK1-like mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase (Kovtun et al., 2000; Pnueli et al., 2003). The group of transcripts elevated during drought and a combination of drought and heat stress also included transcripts encoding enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway, dehydrins and late embryogenesis abundant (LEA)-like proteins, cold-induced proteins, and enzymes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Transcripts specific for a combination of drought and heat stress (cutoff 2 log2) belonged to a number of different groups including HSPs, proteases, starch degrading enzymes, and lipid biosynthesis enzymes (Table I; supplemental material). The steady-state level of different transcripts encoding signal transduction proteins was also elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress. These included receptor-like kinases, small GTP-binding proteins, MYB transcription factors, and protein kinases. In addition, the expression of at least five different transcripts encoding membrane channels was elevated in plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress (CLC-b chloride channel, aquaporin membrane intrinsic protein (MIP), potassium transporter, Na+/Ca2+-antiporter, and an ABC-type transporter). Defense transcripts specifically elevated in cells during a combination of drought and heat stress included thioredoxin and 2-peroxiredoxin, important for the prevention of oxidative stress, P450s, and a salt-inducible protein (Table I; supplemental material).

Transcripts elevated by all three treatments are also shown in Table IA (cutoff 2 log2). They include several HSPs, trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase, an abscisic acid (ABA)-induced protein phosphatase 2C, a two-component phosphorelay protein, and an ethylene-response transcription coactivator.

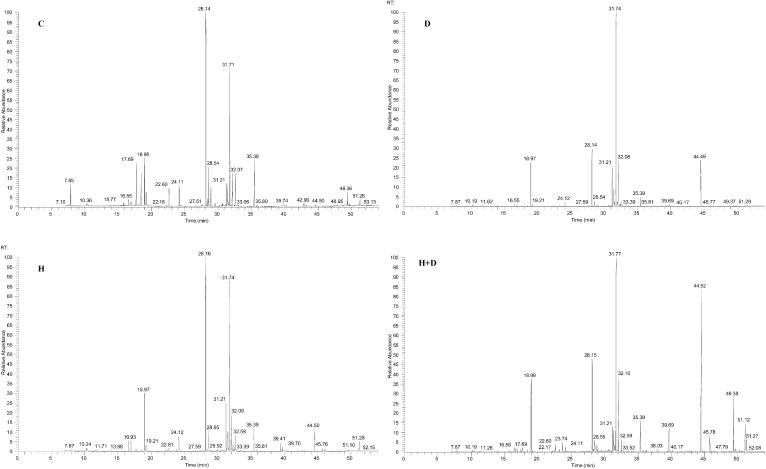

Metabolite Profiling of Arabidopsis Plants Subjected to a Combination of Drought and Heat Stress

To examine the accumulation of stress-associated metabolites in leaves of Arabidopsis plants subjected to drought, heat stress, or their combination, we performed a gas chromatography-mass spectrometric (GC-MS) analysis of polar compounds extracted from leaves of plants subjected to the different stresses. For this analysis we used the same batch of leaf tissues used for the physiological and molecular analysis of plants presented in Figures 1 to 3, and Table I. As shown in Figure 4, the GC profile of plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress was more similar to that of plants subjected to drought than to that of control plants or plants subjected to heat stress. Compound identification is shown in Table II. As shown in Table II, plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress accumulated high levels of sucrose and other sugars such as maltose, melibiose, gulose, and mannitol. In contrast, Pro that accumulated to a very high level in plants subjected to drought did not accumulate in plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress. The level of Gln was specifically elevated in plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress (Table II), suggesting that Pro biosynthesis is inhibited and Glu is converted to Gln instead of Pro during the stress combination. Cys, a potential precursor of the antioxidant glutathione, was also elevated in leaves subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress. This accumulation corresponds with the enhancement of different transcripts involved in glutathione biosynthesis (Table I; supplemental material).

Figure 4.

GC profiles of polar extracts obtained from control plants and plants subjected to heat stress, drought, or a combination of drought and heat stress. C, Control; D, drought; H, heat stress; D+H, a combination of drought and heat stress. Polar compound extraction and GC separation are described in “Materials and Methods.”

Table II.

Metabolites detected by GC-MS in polar extracts of Arabidopsis leaves subjected to heat stress, drought, or a combination of drought and heat stress

| C

|

H

|

D

|

H+D

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derivative | Resp ratioa | seb | %C | Resp ratio | se | %C | Resp ratio | se | %C | Resp ratio | se |

| Citric acid | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.62 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fumaric acid | 2.71 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 1.82 | 0.18 | 0.75 | 2.04 | 1.23 | 1.69 | 4.58 | 0.12 |

| Furanone | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.37 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Glucoheptonic acid meox1 tms | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.46 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.12 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Glucoheptonic acid meox2 tms | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Hydroxybutanoic acid | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Hydroxysuccinic acid | 0.22 | 0.05 | 2.40 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 7.46 | 1.64 | 0.09 |

| Isocitric acid | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Lactic acid | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.19 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Malic acid | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Succinic acid | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 4-Aminobutyric acid | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Allothreonine | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Arg | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| β-Ala | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.70 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.35 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Cys | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.30 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Glu | 0.14 | 1.37 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Gln | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.75 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 4.92 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| Gly | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| His | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Isoleucine | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Leu | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.37 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Lys | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.46 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.12 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Orn | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pro | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.28 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 31.48 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Thr | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.61 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Tyr | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.70 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Val | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.70 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.35 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 1,3-Diaminopropane | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.62 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ethanolamine | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.14 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 2.96 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Putrescine | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 3.15 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 1.55 | 0.55 | 0.09 |

| Fructose-6-phosphate | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.82 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 2.87 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 2.52 | 0.46 | 0.09 |

| Glycerol | 0.12 | 0.03 | 1.35 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Inositol | 0.30 | 0.13 | 1.06 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 1.52 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 2.57 | 0.76 | 0.14 |

| Lactitol | 0.10 | 0.05 | 3.49 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Maltitol | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Mannitol | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1.71 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| Xylitol | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 3.59 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.33 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Fructose meox1 tms | 0.35 | 0.07 | 1.01 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 3.15 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 1.55 | 0.55 | 0.09 |

| Fructose meox2 tms | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 2.87 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 2.52 | 0.46 | 0.09 |

| Fucose | 0.22 | 0.05 | 2.40 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 7.46 | 1.64 | 0.09 |

| Galactose | 0.41 | 0.04 | 1.11 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 4.72 | 1.93 | 0.03 | 4.31 | 1.77 | 0.30 |

| Glucose | 0.29 | 0.03 | 1.52 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 4.56 | 1.32 | 0.06 | 3.92 | 1.13 | 0.20 |

| Gulose | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.56 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 4.85 | 0.24 | 0.04 |

| Isomaltose meox1 tms | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Isomaltose meox2 tms | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 3.56 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Maltose | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.68 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 5.37 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Mannose | 1.97 | 0.13 | 1.13 | 2.23 | 0.10 | 4.37 | 8.62 | 0.51 | 3.90 | 7.68 | 0.89 |

| Melibiose | 0.17 | 0.07 | 2.38 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 4.66 | 0.78 | 0.17 |

| Sucrose meox1 tms | 0.43 | 0.39 | 1.50 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 5.48 | 2.37 | 1.04 | 23.65 | 10.22 | 0.81 |

| Sucrose meox2 tms | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.25 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Trehalose | 0.29 | 0.03 | 1.52 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 4.56 | 1.32 | 0.06 | 3.92 | 1.13 | 0.20 |

GC-MS analysis of polar extracts from plants subjected to heat stress, drought, or a combination of heat stress and drought. Polar extracts were derivatized and analyzed as described in “Materials and Methods.” All samples were methoximated and trimethylsilylated. Compounds with a twofold increase or more are indicated in bold.

Response ratios are peak areas compared to the internal standard ribitol/adonitol. Peak areas were integrated with Genesis algorithm in Xcalibur.

n = 3. se, Standard error; ND, not detected. Values of 0.00 are <0.01.

The source of sucrose in cells subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress is unknown. Because photosynthesis is suppressed in cells subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress (Fig. 1B), it is possible that sucrose is synthesized following starch degradation. Indeed, the expression of all three transcripts required for starch degradation (α-amylase, β-amylase, and α-glucosidase) is significantly elevated in plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress (Table I; supplemental material). In addition, the expression of hexokinase, that phosphorylates glucose, the expression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, that can act as an entry point into the pentose phosphate pathway, and the expression of sucrose-phosphate synthase, fructokinase, and sucrose-UDP glucosyltransferase, involved in sucrose biosynthesis, is elevated in plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress (Table I; supplemental material). Thus, based at least on the steady-state level of these transcripts, the synthesis of sucrose during a combination of drought and heat stress may occur from starch. Additional studies are, however, required to examine this possibility.

Amelioration of Pro Toxicity to Cells during Heat Stress

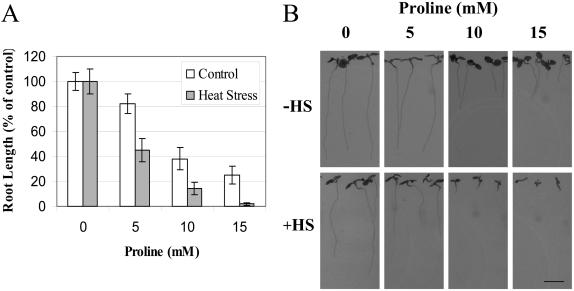

During different abiotic conditions such as cold, salt, and drought, Pro accumulates in cells and functions as an osmoprotectant (Apse and Blumwald, 2002; Zhu, 2002). Moreover, genetically engineering plants to overaccumulate Pro enhances their tolerance to some of these stresses (Kavi Kishor et al., 1995; Nanjo et al., 1999; Nuccio et al., 1999; Rontein et al., 2002). However, Pro can also be toxic to cells if it is not properly removed (Hellmann et al., 2000; Deuschle et al., 2001; Mani et al., 2002; Nanjo et al., 2003). The absence of Pro from cells subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress (Table II) suggested that under these conditions Pro might be toxic to cells. To test whether Pro is toxic to plant cells during heat stress we grew Arabidopsis seedlings on Murashige and Skoog plates that contained different concentrations of Pro and subjected seedlings to a heat stress treatment. Conflicting reports can be found regarding the growth of Arabidopsis seedlings on plates containing Pro. Hellmann et al. (2000) and Mani et al. (2002) reported that Pro is toxic to wild-type seedlings grown on plates. In contrast, Nanjo et al. (2003) reported that the growth of wild-type seedlings is not inhibited by concentrations of up to 25 mm Pro. As shown in Figure 5, we found that the growth of Arabidopsis seedlings is inhibited in the presence of Pro. Moreover, we found that a heat stress treatment (similar to the treatment used in our analysis of plants subjected to heat stress or a combination of drought and heat stress; Figs. 1–4) ameliorated the toxic effect of Pro.

Figure 5.

Amelioration of Pro toxicity during heat stress. A, Measurements of root length taken 48 h post a heat stress treatment of seedlings in the presence or absence of Pro. B, Photographs of Arabidopsis seedlings taken 96 h post a heat stress treatment of seedlings in the presence or absence of Pro; the bar in the lower right represents 4 mm. All measurements were performed as described in “Materials and Methods.”

DISCUSSION

We describe what appears to be a new type of defense response in plants, induced by a combination of drought and heat stress. This response is characterized by enhanced respiration, suppressed photosynthesis, a complex expression pattern of defense and metabolic transcripts, and the accumulation of sucrose and other sugars (Figs. 1 and 2; Tables I and II). Based on our physiological and molecular characterization there were many similarities between the response of Arabidopsis (Fig. 1 and Table I) and tobacco (Rizhsky et al., 2002) to this stress combination, suggesting that this mode of defense response is conserved among different plants.

There was a considerable degree of overlap between transcripts expressed in plants during drought or heat stress and a combination of drought and heat stress (Fig. 2). This overlap suggests that large segments of the defense program of plants against drought or heat stress are coactivated in the same cells during a combination of drought and heat stress. This possibility should be examined in future studies by a comprehensive proteomic approach since it raises a number of interesting questions regarding the co-function of defense proteins such as molecular chaperones and LEA-like proteins in the same cells (see below).

The steady-state level of many different transcripts was specifically elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress (Table I; supplemental material). This group of transcripts included transcripts with an unknown function (over 40%; supplemental material) and a large number of transcripts involved in different defense pathways. Based on changes in steady-state transcript abundance and metabolite levels we could identify the pathways for starch degradation and sucrose biosynthesis as specifically elevated in plants during a combination of drought and heat stress, with some portions of these pathways also expressed during drought (Table I; supplemental material). However, the expression of many other transcripts belonging to different metabolic and defense pathways is also specifically elevated in cells during the stress combination (Table I). It should, however, be noted that our analysis is based upon a single time point (at the end of the heat stress treatment; Fig. 1A), and that a detailed time-course analysis should reveal additional transcripts expressed in cells during drought, heat stress, or their combination.

A considerable overlap was found between transcripts involved in the defense of plants against abiotic conditions such as cold, drought, and salinity (Kreps et al., 2002; Oztur et al., 2002; Seki et al., 2002). In contrast, our findings suggest a relatively small overlap between transcripts induced during drought or heat stress (Fig. 2). Nonetheless, during a combination of drought and heat stress, drought- and heat-stress-specific transcripts are expressed in the same tissues (Table I; supplemental material). Although we can only assume that many of these transcripts are translated, it is interesting that some of these transcripts can be found in the same cells because their function might in some cases be conflicting. For example, some LEA-like proteins and dehydrins can have a helix/random coil structure (Soulages et al., 2002). This structure may interfere with the proper function of some HSPs and molecular chaperones because it may compete with unfolded proteins and enzymes that are the natural substrate of HSPs during stress.

In response to a decrease in leaf water content plants accumulate a variety of compounds that function as osmoprotectants (Bohnert, 2000; Hoekstra et al., 2001). It was suggested that a moderate level of water stress is accompanied by the accumulation of compounds such as Pro and Gly-betaine, whereas a severe level of water stress is accompanied by the accumulation of sugars such as sucrose (Hoekstra et al., 2001). Although the relative water content of plants subjected to drought and plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress was not significantly different (Fig. 1B), plants subjected to drought accumulated Pro whereas plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress accumulated sucrose (Table II). This difference may suggest that a combination of drought and heat stress imposes on plants a different type of internal stress (compared to drought or heat stress), that requires sucrose rather than Pro as an osmoprotectant. Alternatively, Pro may be toxic to cells during a combination of drought and heat stress. Thus, sucrose may be required to replace Pro as the major osmoprotectant of cells during the stress combination.

At least three different studies suggested that Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C), and perhaps other intermediates in Pro biosynthesis and degradation can be toxic to cells (Hellmann et al., 2000; Deuschle et al., 2001; Mani et al., 2002). It is possible that heat stress alters the balance between Pro biosynthesis and degradation and causes the accumulation of P5C and/or other intermediates. Moreover, an enhanced activity of mitochondria (i.e. enhanced respiration) was found in cells during heat stress and a combination of drought and heat stress (Fig. 1B; Rizhsky et al., 2002). Because Pro biosynthesis and degradation occurs in the mitochondria, the accumulation of toxic compounds such as P5C in this organelle might be more damaging to cells under these conditions (especially in plants subjected to a combination of drought and heat stress that appear to completely depend upon the mitochondria for their energetic metabolism; Fig. 1B; Rizhsky et al., 2002). Our results (Table II; Fig. 5), as well as the results of others (e.g. Deuschle et al., 2001), suggest that plants that were engineered to overaccumulate Pro in order to enhance their tolerance to abiotic stress (Kavi Kishor et al., 1995; Nanjo et al., 1999; Nuccio et al., 1999; Rontein et al., 2002) might not be resistant to field conditions that occur in some areas and include a combination of drought and heat stress, or simply heat stress.

The response of plants to a combination of drought and heat stress highlights the plasticity of the plant genome and its ability to modulate its response to complex environmental conditions that occur in the field. Key to this plasticity is a large network of transcription factors that regulate the response of plants to different stresses (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000; Chen et al., 2002). Here we show that the complex response of HSPs during heat stress, drought, and their combination (Fig. 3A; Table I; Rizhsky et al., 2002) is reflected in the pattern of expression of HSFs (Fig. 3B). Compared to humans and animals that express, at the most, four different transcripts encoding HSFs, Arabidopsis contains 21 different HSF-encoding genes that belong to at least three different families (Nover et al., 2001). Our results (Fig. 3; Pnueli et al., 2003) suggest that plant HSFs function as a network of transcription factors that controls the expression of HSPs during different stresses. Thus, we identified oxidative- and light-stress-specific HSFs (Pnueli et al., 2003) as well as heat-stress- and drought-specific HSFs (Fig. 3). Future analysis of this gene family, including measurements of HSF activity in cells, might provide an initial insight into how plants compensated during evolution for their sessile nature by developing complex and specialized gene families to control their response to environmental conditions. These were most likely created by gene duplication, however, acquired specific roles related to specific pathways or stresses, as well as their combination (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000). Similar results were also obtained with several members of the MYB transcription factor gene family (Fig. 1; supplemental material), and MYB-At1g26580 was identified as specifically elevated during a combination of drought and heat stress (Table I).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis plants (cv Columbia) were grown under controlled conditions: 21°C to 22°C, 100 μmol m−2 s−1, and a relative humidity of 70%. All treatments were performed in parallel. Heat stress was applied by raising the temperature in the growth chamber to 38°C for 6 h. Drought was imposed by withdrawing water from plants until they reached a relative water content (RWC) of 70% to 75% (typically 6–7 d). A combination of drought and heat stress was performed by subjecting drought-stressed plants (RWC of 70%–75%) to a heat stress treatment (38°C for 6 h). All plants, i.e. drought-stressed plants, well-watered plants subjected to heat stress, drought- and heat-stressed plants, and control well-watered plants kept at 21°C to 22°C were sampled at the same time for analysis (Rizhsky et al., 2002; Fig. 1A). All experiments were performed in triplicates and repeated at least three times. All tissues collected were divided and used in parallel for molecular and metabolic analysis of plants.

Molecular and Physiological Analysis

RNA and protein were isolated and analyzed by RNA and protein blots as previously described (Pnueli et al., 2003; Rizhsky et al., 2003). A ribosomal 18S rRNA probe was used to control for RNA loading. Photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, and dark respiration were measured with a Li-Cor LI-6400 apparatus as described by Pnueli et al. (2003) using the Arabidopsis leaf chamber (Li-Cor).

DNA Chip Analysis

In three independent experiments RNA was isolated from control plants and plants subjected to heat stress, drought, and a combination of heat and drought stress (a pool of 80 to 100 plants per treatment in triplicates), as described above. This RNA was used to perform the chip analysis (Arabidopsis ATH1 chips; Affymetrix) at the University of Iowa DNA facility (http://dna-9.int-med.uiowa.edu/microarrays.htm). Conditions for RNA isolation, labeling, hybridization, and data analysis are described in Pnueli et al. (2003) and Rizhsky et al. (2003). Comparative analysis of samples was performed with the GeneChip mining tool version 5.0 and the Silicon Genetics GeneSpring version 5.1. Some of the comparison results were confirmed by RNA blots.

GC-MS Analysis

Extraction and derivatization were performed according to Roessner et al. (2000) and Fiehn et al. (2000). Leaves were harvested, cut into 1- to 2-mm-long pieces, and stored at −80°C. For each sample, a total of 250 mg of frozen leaves was transferred into a 13 × 100 borosilicate culture tube, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder with a glass rod. Aliquots of 1.4 mL methanol and 50 μL of ribitol/adonitol (2 mg/mL water stock) were added. Tubes were vortexed, and pH was verified within 5 to 6. The solution was sonicated for 10 min at 42 kHz with a Branson 3510 ultrasonic cleaner (Branson Ultrasonic, Danbury, CT). Extraction was done in a water bath at 70°C for 15 min. Tubes were centrifuged for 20 min at 4,500 rpm and the supernatant was decanted to new culture tubes, and 1.4 mL of water and 0.75 mL of chloroform were added. The mixture was vortexed thoroughly and centrifuged for 5 min at 4,500 rpm. The polar phase (methanol/water) was decanted to 1.5-mL HPLC vials and dried in a Centrivap benchtop centrifugal concentrator (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) overnight. The dried polar phase was methoximated for 90 min at 30°C (80 μL of 20 mg/mL methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine), a 40-μL aliquot of a retention time standard mixture was added (Roessner et al., 2000), and the mixture was trimethylsilylated for 30 min at 37°C. Solutions were transferred to glass inserts within the 1.5-mL HPLC vials prior to injection.

Sample volumes of 1 μL were injected at a split ratio of 25:1 into a Trace DSQ GC/MS system (Thermo Finnigan, Austin, TX) equipped with Combi-Pal autosampler (Leap Technologies, Carrboro, NC). Tuning was done using tris(perfluorobutyl)amine (CF43) as a reference gas. Chromatography was performed using a 30-m × 250-μm Alltech AT-5MS column (Alltech Associates, Deerfield, IL). Injection temperature was 230°C, the interface was kept at 250°C, and the ion source was kept at 200°C. Oven temperature program was 5 min at 70°C, followed by a 5°C min−1 ramp to 310°C, 1 min at 310°C, and a final 6 min at 70°C before the next injection. Carrier gas was helium at a constant flow of 1 mL min−1. Mass spectra were recorded at two scans per second over a range of 50 to 600 m/z. Compounds were identified based on retention time and comparison with reference spectra in mass spectral libraries. Quantitation of compounds was done using a processing method in Xcalibur version 1.3 (Xcalibur, Herndon, VA) where peak area was integrated with the Genesis algorithm. Statistical analysis of peak area was done using the SAS system version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Analysis of Pro Toxicity during Heat Stress

Arabidopsis seedlings (15–20 per plate) were germinated under sterile conditions on Murashige and Skoog plates (0.5×), containing different concentrations of Pro (0–15 mm). Plates were placed vertically, and seedlings were allowed to grow at 21°C to 22°C, 60 μmol m−2 s−1. Three-day-old seedlings were subjected to a heat stress treatment as described above and allowed to recover at 21°C to 22°C. Forty-eight hours following the heat stress treatment the root length of seedlings (Rizhsky et al., 2003) was measured and compared between heat-stress-treated and heat-stress-untreated seedlings grown in the presence or absence of Pro. In each experiment six different plates were used for each concentration (three heat stressed and three non-heat stressed).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Eve Syrkin-Wurtele, Carol Foster, and Hailong Zhang for their help with Affymetrix data analysis.

This work was supported by funding from the Plant Sciences Institute at Iowa State University, the Biotechnology Council of Iowa State University, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Iowa State University, the Israeli Academy of Science, the Nevada Agricultural Experimental Station (publication no. 03031333), and the Fund for the Promotion of Research at the Technion.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.033431.

References

- Apse MP, Blumwald E (2002) Engineering salt tolerance in plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol 13: 146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408: 796–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert HJ (2000) What makes desiccation tolerable? Genome Biol 1: 1010.1–1010.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Provart NJ, Glazebrook J, Katagiri F, Chang HS, Eulgem T, Mauch F, Luan S, Zou G, Whitham SA, et al. (2002) Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative functions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell 14: 559–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craufurd PQ, Peacock JM (1993) Effect of heat and drought stress on sorghum. Exp Agr 29: 77–86 [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecka-Verner E, Gurley WB (2000) Plant heat shock transcription factors: divergence in structure and function. Biotechnologia 3: 125–142 [Google Scholar]

- Cushman JC, Bohnert HJ (2000) Genomic approaches to plant stress tolerance. Curr Opin Plant Biol 3: 117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschle K, Funck D, Hellmann H, Daschner K, Binder S, Frommer WB (2001) A nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial Delta-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase and its potential role in protection from proline toxicity. Plant J 27: 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiehn O, Kopka J, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L (2000) Identification of uncommon plant metabolites based on calculation of elemental compositions using gas chromatography and quadrupole mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 23: 3573–3580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann H, Funck D, Rentsch D, Frommer WB (2000) Hypersensitivity of an Arabidopsis sugar signaling mutant toward exogenous proline application. Plant Physiol 123: 779–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyne EG, Brunson AM (1940) Genetic studies of heat and drought tolerance in maize. J Am Soc Agron 32: 803–814 [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra FA, Golovina EA, Buitink J (2001) Mechanisms of plant desiccation tolerance. Trends Plant Sci 6: 431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J, Bartels D (1996) The molecular basis of dehydration tolerance in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 47: 377–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap V, Bhargava S, Streb P, Feierabend J (1998) Comparative effect of water, heat and light stresses on photosynthetic reactions in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. J Exp Bot 49: 1715–1721 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Huang B (2001) Drought and heat stress injury to two cool season turfgrasses in relation to antioxidant metabolism and lipid peroxidation. Crop Sci 41: 436–442 [Google Scholar]

- Kavi Kishor PB, Hong Z, Miao GH, Hu CAA, Verma DPS (1995) Overexpression of [delta]-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase increases proline production and confers osmotolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol 108: 1455–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtun Y, Chiu WL, Tena G, Sheen J (2000) Functional analysis of oxidative stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 2940–2945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreps JA, Wu Y, Chang H-S, Zhu T, Wang X, Harper JF (2002) Transcriptome changes for Arabidopsis in response to salt, osmotic, and cold stress. Plant Physiol 130: 2129–2141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani S, Van De Cotte B, Van Montagu M, Verbruggen N (2002) Altered levels of proline dehydrogenase cause hypersensitivity to proline and its analogs in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 128: 73–83 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miernyk JA (1999) Protein folding in the plant cell. Plant Physiol 121: 695–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R (2002) Oxidative stress, antioxidants, and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci 7: 405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Merquiol E, Hallak-Herr E, Rachmilevitch S, Kaplan A, Cohen M (2001) Living under a ‘dormant’ canopy: a molecular acclimation mechanism of the desert plant Retama raetam. Plant J 25: 407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat AS (2002) Plant genetics. Finding new ways to protect drought-stricken plants. Science 296: 1226–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjo T, Fujita M, Seki M, Kato T, Tabata S, Shinozaki K (2003) Toxicity of free proline revealed in an arabidopsis T-DNA-tagged mutant deficient in proline dehydrogenase. Plant Cell Physiol 44: 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjo T, Kobayashi M, Yoshiba Y, Kakubari Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (1999) Antisense suppression of proline degradation improves tolerance to freezing and salinity in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett 461: 205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L, Bharti K, Doring P, Mishra SK, Ganguli A, Scharf KD (2001) Arabidopsis and the heat stress transcription factor world: how many heat stress transcription factors do we need? Cell Stress Chaperones 6: 177–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuccio ML, Rhodes D, McNeil SD, Hanson AD (1999) Metabolic engineering of plants for osmotic stress resistance. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2: 128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oztur ZN, Talame V, Deyholos M, Michalowski CB, Galbraith DW, Gozukirmizi N, Tuberosa R, Bohnert HJ (2002) Monitoring large-scale changes in transcript abundance in drought- and salt-stressed barley. Plant Mol Biol 48: 551–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchuk II, Volkov RA, Schoffl F (2002) Heat stress- and heat shock transcription factor-dependent expression and activity of ascorbate peroxidase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 129: 838–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo P, Murphy JA, Berkowitz GA (1996) Physiological changes associated with performance of Kentucky bluegrass cultivars during summer stress. HortScience 31: 1182–1186 [Google Scholar]

- Pnueli L, Hongjian L, Mittler R (2003) Growth suppression, altered stomatal responses, and augmented induction of heat shock proteins in cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase (Apx1)-deficient Arabidopsis plants. Plant J 34: 187–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queitsch C, Hong SW, Vierling E, Lindquist S (2000) Heat shock protein 101 plays a crucial role in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12: 479–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L, Hongjian L, Mittler R (2002) The combined effect of drought stress and heat shock on gene expression in tobacco. Plant Physiol 130: 1143–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L, Liang H, Mittler R (2003) The water-water cycle is essential for chloroplast protection in the absence of stress. J Biol Chem 278: 38921–38925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessner U, Wagner C, Kopka J, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L (2000) Simultaneous analysis of metabolites in potato tuber by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Plant J 23: 131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rontein D, Basset G, Hanson AD (2002) Metabolic engineering of osmoprotectant accumulation in plants. Metab Eng 4: 49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DA, Jacobson LA (1935) The killing effect of heat and drought on buffalo grass and blue grama grass at Hays. Kansas J Amer Soc Agro 27: 566–582 [Google Scholar]

- Savin R, Nicolas ME (1996) Effects of short periods of drought and high temperature on grain growth and starch accumulation of two malting barley cultivars. Aust J Plant Physiol 23: 201–210 [Google Scholar]

- Seki M, Narusaka M, Ishida J, Nanjo T, Fujita M, Oono Y, Kamiya A, Nakajima M, Enju A, Sakurai T, et al. (2002) Monitoring the expression profiles of 7000 Arabidopsis genes under drought, cold and high-salinity stresses using a full-length cDNA microarray. Plant J 31: 279–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K (1996) Molecular responses to drought and cold stress. Curr Opin Biotechnol 7: 161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulages JL, Kim K, Walters C, Cushman JC (2002) Temperature-induced extended helix/random coil transitions in a group 1 late embryogenesis-abundant protein from soybean. Plant Physiol 128: 822–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storozhenko S, De Pauw P, Van Montagu M, Inze D, Kushnir S (1998) The heat-shock element is a functional component of the Arabidopsis APX1 gene promoter. Plant Physiol 118: 1005–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierling E (1991) The roles of heat shock proteins in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 42: 579–620 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-K (2002) Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 53: 247–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.