Abstract

Hyperglycemia (HG) reduces AMPK activation leading to impaired autophagy and matrix accumulation. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) treatment improves HG-induced renovascular remodeling however, its mechanism remains unclear. Activation of LKB1 by the formation of heterotrimeric complex with STRAD and MO25 is known to activate AMPK. We hypothesized that in HG; H2S induces autophagy and modulates matrix synthesis through AMPK-dependent LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex formation. To address this hypothesis, mouse glomerular endothelial cells were treated with normal and high glucose in the absence or presence of sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS), an H2S donor. HG decreased the expression of H2S regulating enzymes CBS and CSE, and autophagy markers Atg-5, −7, −3 and LC3B/A ratio. HG increased galectin-3 and periostin, markers of matrix accumulation. Treatment with NaHS to HG cells increased LKB1/STRAD/MO25 formation and AMPK phosphorylation. Silencing the encoded genes confirmed complex formation under normoglycemia. H2S-mediated AMPK activation in HG was associated with upregulation of autophagy and diminished matrix accumulation. We conclude that H2S mitigates adverse remodeling in HG by induction of autophagy and regulation of matrix metabolism through LKB1/STRAD/MO25 dependent pathway.

Keywords: Diabetes, sodium hydrogen sulfide, LKB1, STRAD, MO25, autophagy, extracellular matrix

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is well known as a potent vasodilator and signaling molecule under normal and pathophysiological conditions. In the mammalian tissue, it is produced from L-cysteine by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3MST), and cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) [1]. Previously we reported that in diabetic kidney, H2S is a critical regulator of MMP-9-induced renovascular remodeling involving connexins-40 and −43 [2]. H2S treatment has also been shown to regulate interstitial microcirculation in diabetic nephropathy [3]. Despite these studies, the exact mechanism of how H2S mediates these effects remains unknown.

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a key regulator of cellular energy status in the body. Under metabolic stress, activation of AMPK leads to increased glucose uptake, increased expression of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) and mitochondrial biogenesis [4]. The activation of AMPK involves phosphorylation of threonine residue by an upstream kinase, liver kinase B1 (LKB1) which forms a complex with two other subunits, STE20-related adaptor (STRAD) and mouse protein 25 (MO25) [5]. The formation of this tri-molecular complex, LKB1/STRAD/MO25 is crucial in the LKB1-AMPK signaling pathway for cell growth and proliferation [5]. Acute hyperglycemia has been reported to reduce AMPK phosphorylation in the kidney and promote protein synthesis by activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex and administration of H2S was found to restore basal AMPK phosphorylation and reverse these changes [6, 7]. A reduction in AMPK phosphorylation in type 1 diabetes was shown to induce podocyte apoptosis and worsening of renal injury [8]. Similarly, reduced AMPK activation has also been demonstrated in human diabetic nephropathy [9]. In the above study, treatment with 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside, an AMPK activator was found to reduce accumulation of matrix proteins and reduce albuminuria [9]. A recent study has also suggested that AMPK activation plays an important role in the autophagy mechanism in chronic kidney disease [10].

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process which recycles damaged or unused proteins and organelles to promote cell survival under stress conditions and is regulated mainly by mTOR and AMPK pathways [11, 12]. Recent reports suggest that autophagy is defective in hyperglycemic condition leading to podocyte and proximal tubular injury causing acceleration of the disease process [13, 14]. Upregulation of mTOR is associated with hypertrophy of glomerular and tubular epithelial cells and its inhibition using rapamycin was found to be protective [15–17]. Inactivation of AMPK in diabetes was associated with similar renal injury which was abrogated by metformin, an AMPK agonist [6, 18, 19]. Recently, we also reported that induction of autophagy mitigates adverse renovascular remodeling in salt-sensitive hypertension [20]. Taken together the above studies suggest that autophagy plays significant role in conditions associated with excess deposition of extracellular matrix proteins causing renal fibrosis.

Since hyperglycemia is associated with decreased H2S production and reduced activation of AMPK, in this study we hypothesized that 1) diminished H2S inhibits LKB1 activation thus decreasing AMPK phosphorylation, 2) NaHS (H2S donor) treatment phosphorylates LKB1 by forming a trimolecular complex with STRAD and MO25 leading to AMPK activation, and 3) activation of AMPK induces autophagy and reduces excess matrix deposition in hyperglycemic condition. Here, we report that H2S treatment mediates its beneficial effects in hyperglycemic condition by activation of LKB1-AMPK signaling which involves the formation of LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex.

RESULTS

H2S supplementation normalizes H2S levels and CBS and CSE expression in HG cells

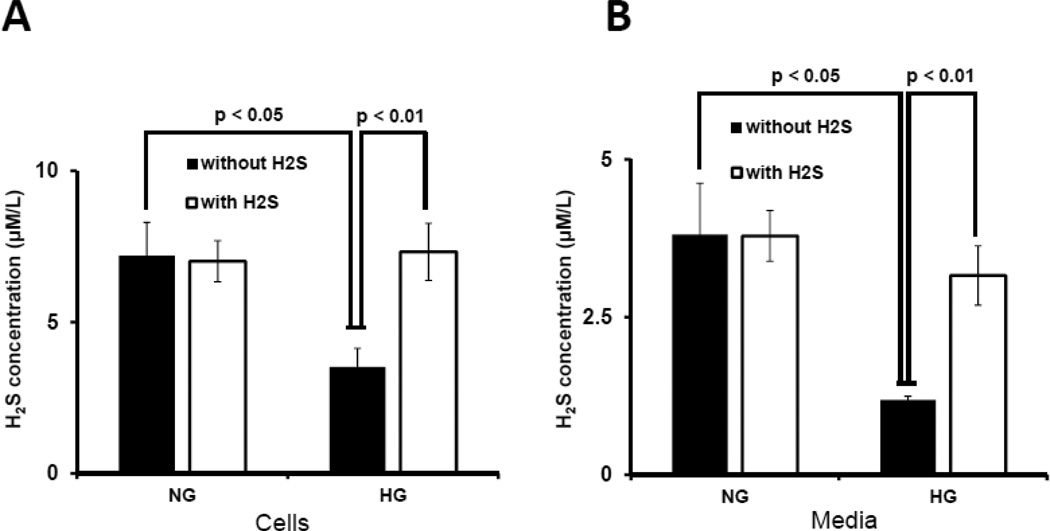

To determine whether hyperglycemia was associated with decreased H2S, we measured H2S concentration in the cells and culture media. There was no difference in H2S concentration in NG cells treated without or with H2S (Fig. 1A). In contrast, HG cells had low levels of H2S which was restored to normal following H2S treatment (Fig. 1A). Similar results were obtained for H2S in culture media (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Hyperglycemia attenuated H2S production, and CBS and CSE expression.

Mouse glomerular endothelial cells (MGECs) were cultured in normoglycemic (NG) and hyperglycemic (HG) conditions without or with H2S (30 µM) for 24 h. (A–B) H2S concentration in cell lysates and media. H2S measurement in the media was performed within 2 h of sample collection. (C) 100 µg of protein was loaded for Western blot and GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Pixel densities were quantified as fold change. (E) RT-PCR amplification and transcript levels of CBS and CSE were measured using 2 µg of RNA extracted from MGECs as described in Materials and Methods. GAPDH mRNA was used as loading control. (F) Pixel densities are presented as fold change. Data represents mean ± s.e.m. (n = 5). Images are representative of four independent experiments performed in triplicate for H2S.

To determine if HG affects CBS and CSE, enzymes that regulate H2S production, cells were treated with NG or HG in the absence or presence of H2S. In cells maintained at NG, treatment with H2S had no effect on the expression of CBS and CSE protein (Fig. 1C,D) and mRNA (Fig. 1E,F). HG abolished the expression of CBS and CSE protein and mRNA which was normalized following H2S treatment (Fig. 1 C–F).

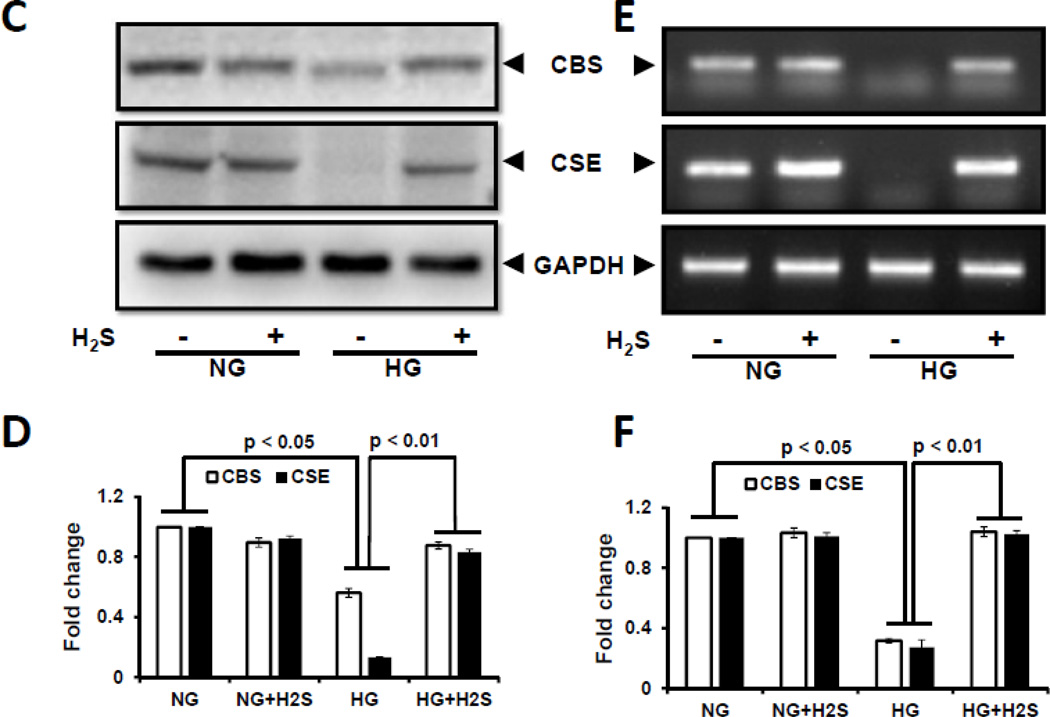

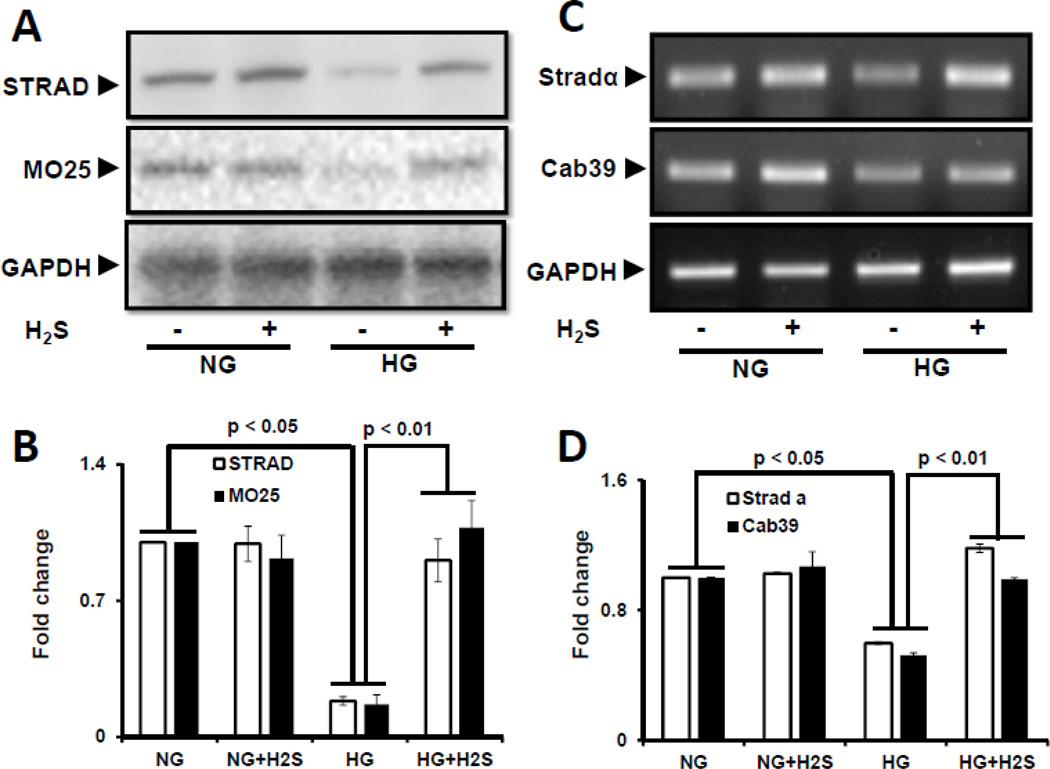

H2S normalizes expression of STRAD and MO25 in HG cells

Activation of AMPK is regulated by upstream serine/threonine kinase LKB1. Since LKB1 activation and translocation from nucleus requires STRAD and MO25, we first determined the effects of HG and H2S on the expression of STRAD and MO25. Western blot showed basal expression of STRAD and MO25 in NG cells which did not change upon treatment with H2S (Fig. 2A,B). However, HG decreased the expression of STRAD and MO25 which was restored following H2S treatment (Fig. 2A,B). STE-20 related adaptor protein-α (Stradα) and Calcium binding protein 39 (Cab39) regulate the expression of STRAD and MO25 proteins, respectively [21, 22]. To determine whether protein expression correlates with gene expression, we measured Stradα and Cab39 mRNA by semiquantitative PCR. Similar to protein expression above, there was basal expression of Stradα and Cab39 mRNA in NG which was not affected by treatment with H2S (Fig. 2C,D). HG caused a significant decrease in STRAD and MO25 expression which was restored following H2S treatment (Fig. 2C,D).

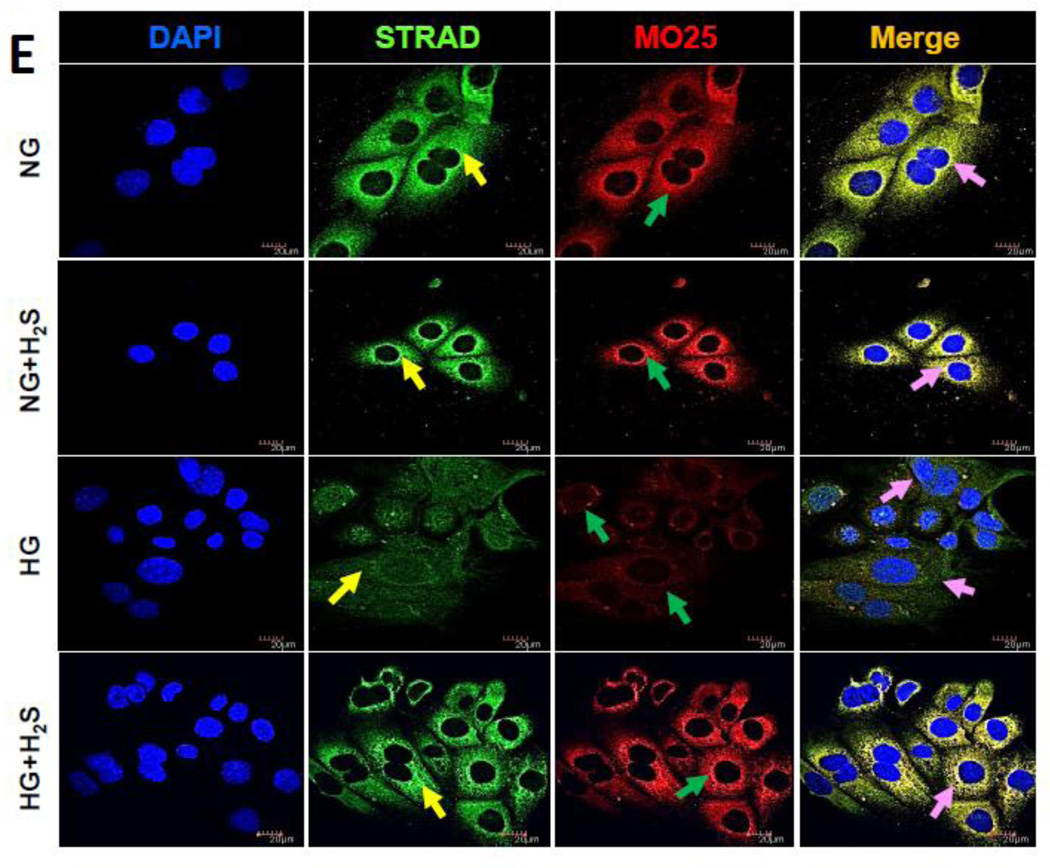

Figure 2. H2S induces expression and co-localization of STRAD and MO25 in hyperglycemia.

MGECs were incubated in NG or HG condition without or with H2S for 24 h. (A) Protein expression of STRAD and MO25 were measured by Western blot analysis using GAPDH as control. (B) Fold change of respective proteins. (C) RT-PCR amplification and gene expression of Strad-α (gene controlling STRAD) and Cab39 (gene controlling MO25). (D) Fold change of gene expression. Images are representative of single experiment. Bar graphs represent mean ± s.e.m. from five independent experiments (n = 5). (E) Cells were immunostained against STRAD (yellow arrow) and MO25 (green arrow), and nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue). Co-localization of STRAD and MO25 are shown in the merge image (pink arrow). Scale bar, 20 µm.

Immunostaining further confirmed basal expression and co-localization of STRAD and MO25 in NG cells which was unaffected following H2S treatment (Fig. 2E) However, in HG cells their expression was significantly decreased and H2S treatment normalized their expression (Fig. 2E).

To confirm the above data, we used siRNA technology to knock down STRAD, MO25, or LKB1 and determined the complex formation. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2F, knockdown of STRAD or MO25 by siRNA effectively decreased its respective protein expression compared to cells treated with scrambled siRNA in NG condition. Further, knockdown of LKB1 by siRNA showed basal expression of STRAD and MO25. Treatment of NG cells with H2S failed to restore basal expression of individual kinases involved in the complex formation (Supplementary Fig. 2G).

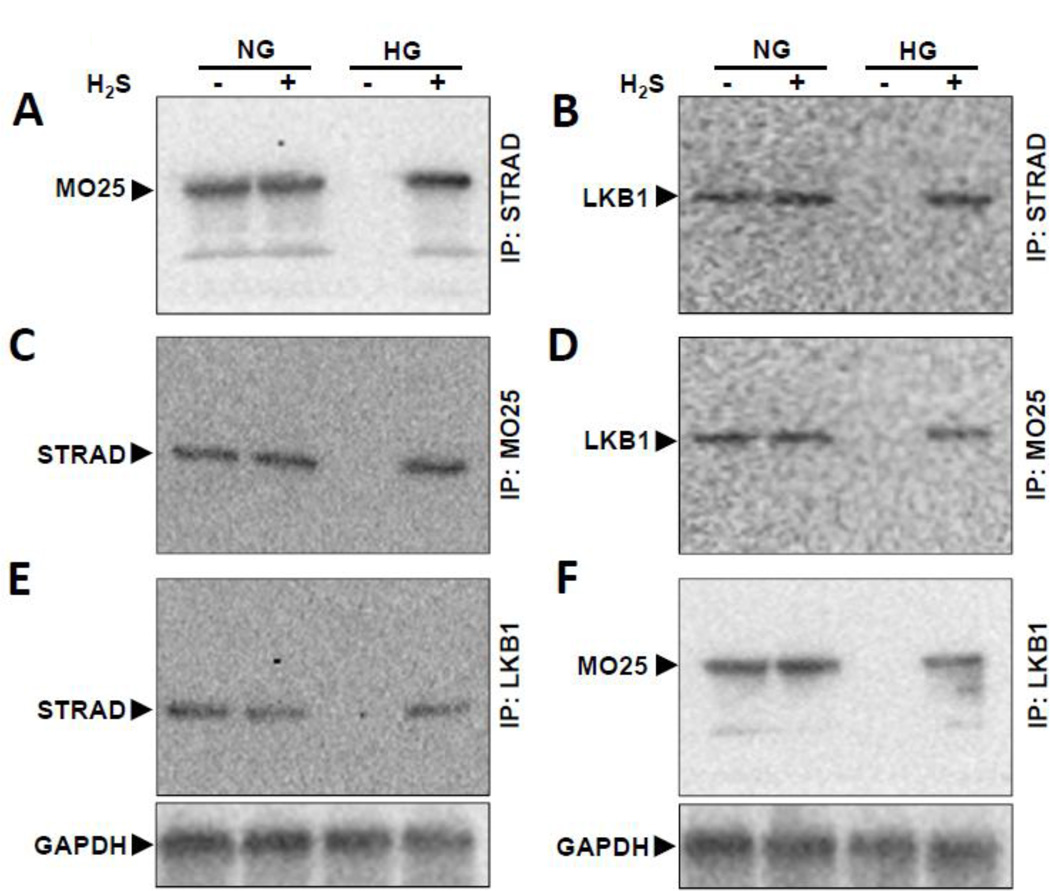

H2S normalizes LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex formation in HG cells

To confirm the formation of LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex, we used co-immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with STRAD antibody followed by probing with MO25 (Fig. 3A) and LKB1 (Fig. 3B). Similarly, other possible combinations were done as shown in Fig. 3C – F in NG and HG conditions without and with H2S. In NG cells treated without or with H2S, STRAD, MO25, and LKB1 individually were able to precipitate the other members of the complex. In HG cells, the complex was not detected suggesting the lack of formation of the complex or decreased expression of the proteins involved in complex formation. Treatment with H2S restored the association of the complex similar to NG cells (Fig. 3A – F).

Figure 3. H2S treatment restores tri-molecular complex formation in HG condition.

(A–F) MGECs were incubated in NG and HG condition without or with H2S for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with STRAD, MO25 or LKB1 separately and immunoblotted with antibodies against the other two molecules in the tri-molecular complex (LKB1/STRAD/MO25). Immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by Western blot (WB) analyses validated positive association between LKB1, STRAD and MO25 kinases. Representative blots are from individual experiments.

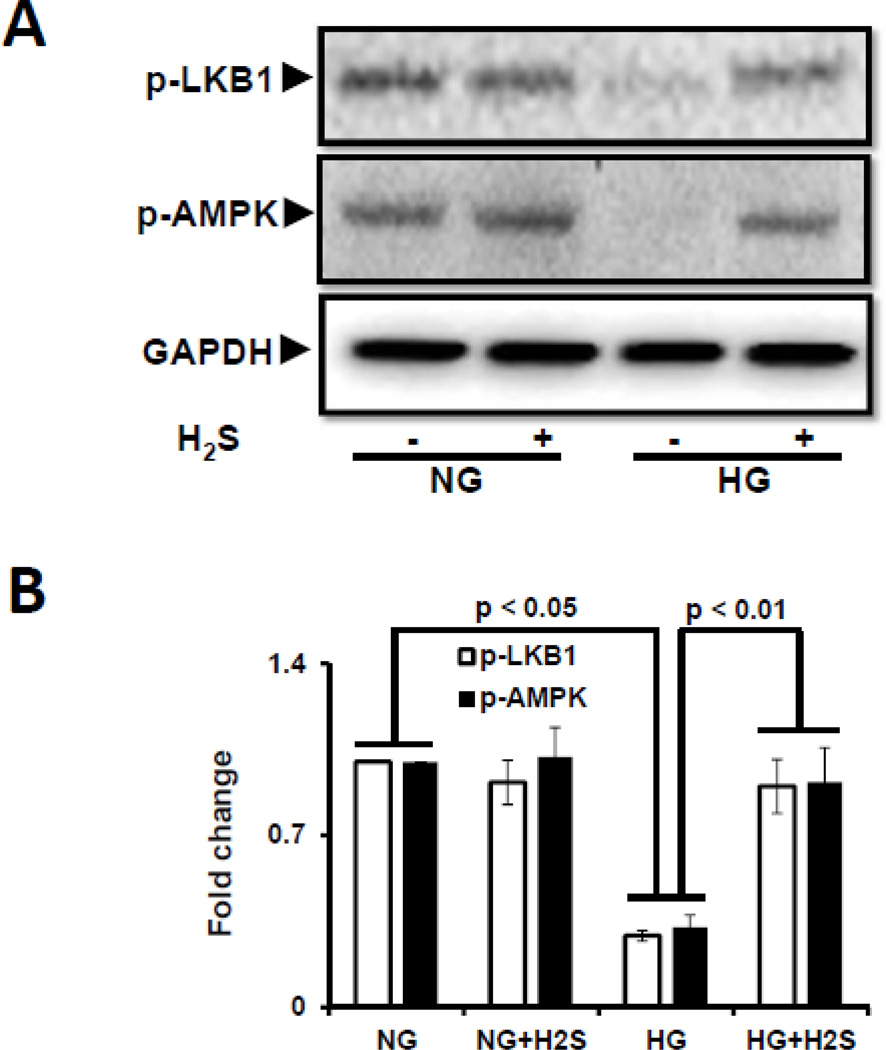

H2S normalizes HG-induced decrease in phosphorylation of LKB1 and AMPK

Since activation of LKB1 is essential for AMPK phosphorylation and subsequent autophagy, we measured the phosphorylation status of LKB1 and AMPK as surrogate for activation in cells treated with NG or HG in the presence or absence of H2S. As shown in Fig. 4 immunoblotting (A and B) and immunofluorescence (C) showed that under basal (NG) conditions both LKB1 and AMPK are phosphorylated. Treatment with H2S had no significant effect on the phosphorylation of LKB1 and AMPK in NG cells (Fig. 4A,B). In contrast MGECs treated with HG, showed minimal phosphorylation of LKB1 and AMPK compared to NG treated cells (Fig. 4A,B). Interestingly, H2S treatment to HG cells restored phosphorylation of LKB1 and AMPK to levels observed in NG cells (Fig. 4A,B).

Figure 4. H2S treatment in hyperglycemia normalized LKB1 and AMPK phosphorylation.

(A) Phospho-LKB1 and phospho-AMPK were measured by Western blot using GAPDH as control. (B) Protein expression as fold change. (C) MGECs were cultured in NG and HG condition in 8-well chamber slide, and treated without or with H2S for 24 h. Cells were immunostained with phospho-LKB1 and phospho-AMPK antibodies to detect kinase activation. Yellow, green and pink arrows represent p-LKB1, p-AMPK, and co-localization of p-LKB1 and p-AMPK, respectively. Images are representative of single experiment and bar graphs represent mean ± s.e.m. from five independent experiments (n = 5).

To determine the formation of LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex and subsequent AMPK phosphorylation we used siRNA to knock down respective kinases and measured the phosohorylation of LKB1 and AMPK by immunofluorescence in NG cells. As shown in supplementary Fig. 4D, no basal phosphorylation was detected for both LKB1 and AMPK compared to levels seen in NG cells using scrambled siRNA as control. Treatment with H2S failed to restore LKB1 and AMPK phosphorylation further confirming the lack of complex formation (supplementary Fig. 4E).

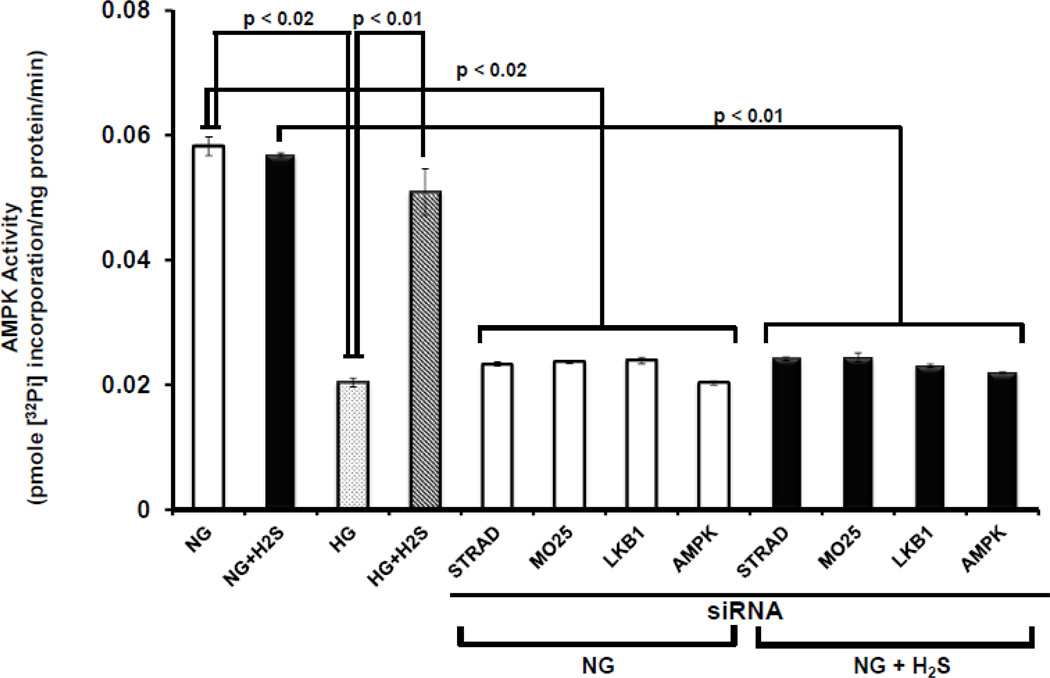

H2S restores HG-induced decrease in AMPK activity

The above data suggest that HG decreases LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex formation which is required for AMPK activation. To determine whether the effect of H2S on AMPK activation, we determined AMPK activity in NG and HG cells in the presence or absence of H2S. As shown in Fig. 5, there was basal activity of AMPK in NG cells which was not affected by treatment with H2S. In contrast, HG cells had significantly lower AMPK activity as compared to NG cells. Interestingly, treatment with H2S significantly upregulated AMPK activity in HG cells compared to untreated cells. Furthermore, knock-down of any member of the LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex in NG cells both in the absence or presence of H2S blocked the activation of AMPK (Fig. 5). Additionally, siRNA inhibition of AMPK showed diminished activity in NG conditions without or with H2S treatment (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Diminished AMP kinase activity in HG condition was normalized by H2S.

MGECs were incubated in NG and HG condition, and cells were treated without or with H2S for 24 h. In separate experiments, cells were transfected with siRNAs for STRAD, MO25, LKB1 and AMPK for 24 h in NG condition, and then treated without or with H2S for additional 24 h. Cells were homogenized in HEPES-Brij buffer and AMPK activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. AMP kinase activity corresponds to the formation of a tri-molecular complex (LKB1/STRAD/MO25). The activities are expressed as pmoles phosphate incorporated into the AMPK substrate peptide per minute per milligram protein. Data represents mean ± s.e.m. Two separate assays were done for four independent experiments (n = 4).

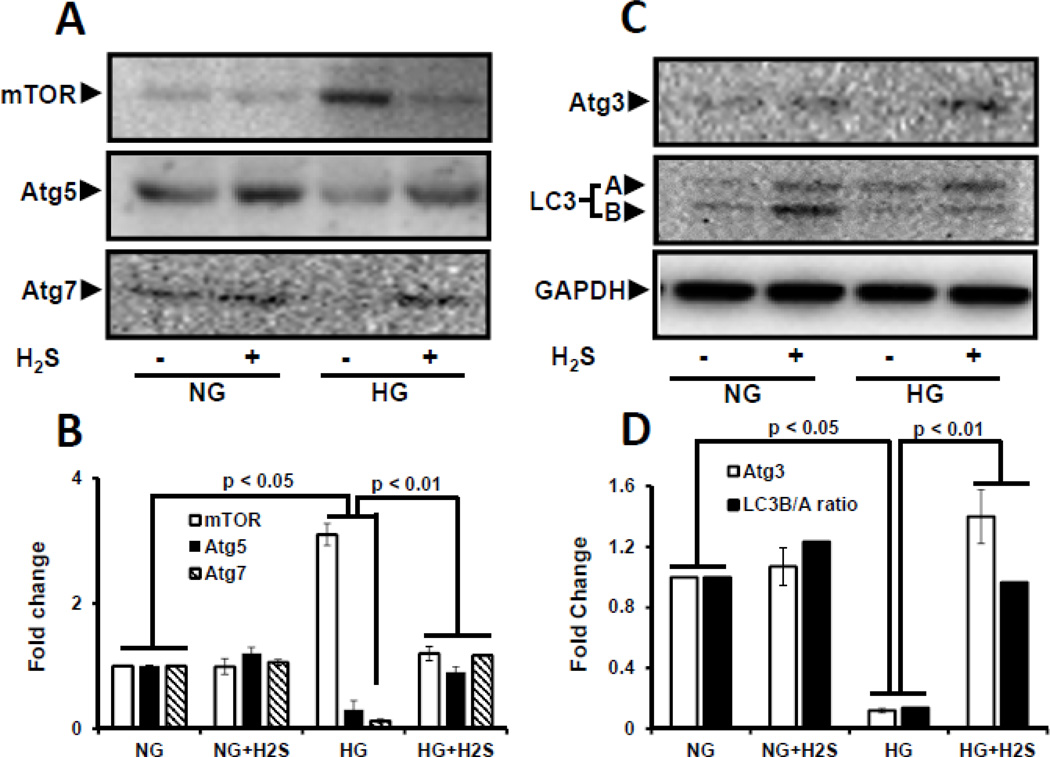

H2S normalizes HG-induced impaired autophagy

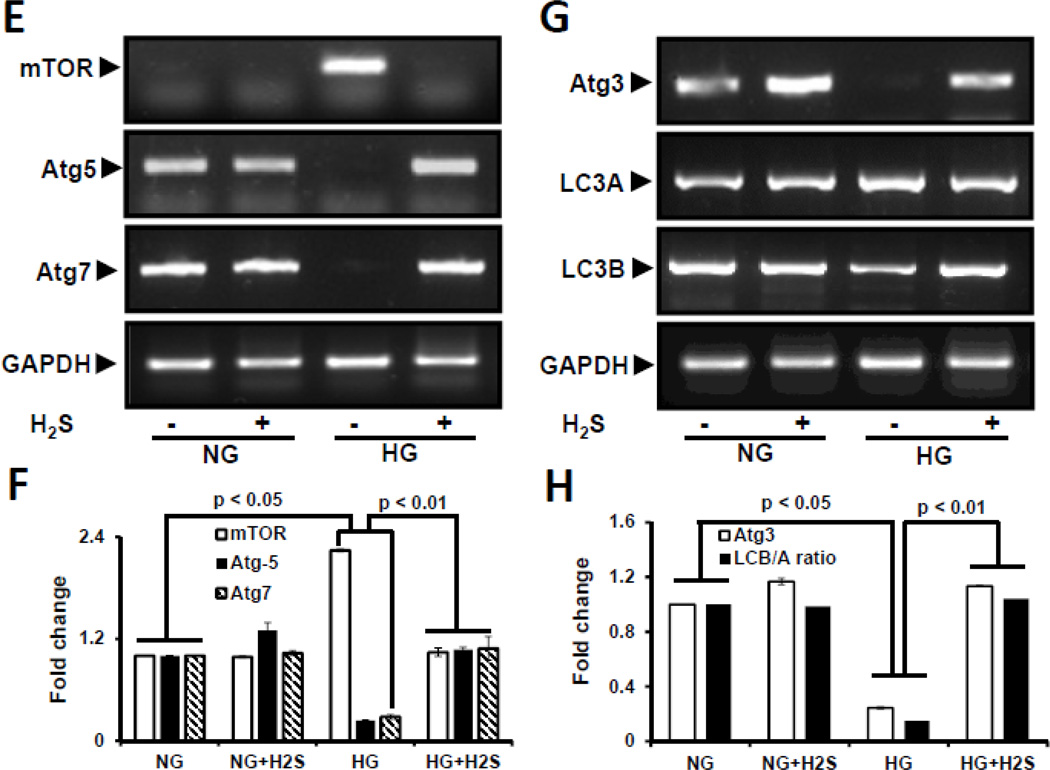

Impaired autophagy results in accumulation of abnormal degradation products including extracellular matrix proteins. We therefore measured the effect of H2S on the expression of autophagy markers, viz; mTOR, Atg-5, −7, −3 and LC3B/A ratio in NG and HG cells. In NG cells mTOR levels were low whereas, Atg-5, −7, −3 were expressed at baseline levels which was unaffected following H2S treatment. However, in HG cells there was a significant decrease in Atg −5, −7, −3 expression and LC3B/A ratio, and a significant increase in mTOR expression (Fig 6A – D). Treatment with H2S to HG cells restored the expression of Atg −5, −7, −3 and LC3B/A ratio to basal levels, and decreased mTOR expression. Semi-quantitative PCR confirmed mRNA levels with their protein expression in NG and HG conditions without or with H2S treatment (Fig. 6E – H).

Figure 6. H2S modulated autophagy in hyperglycemia (HG).

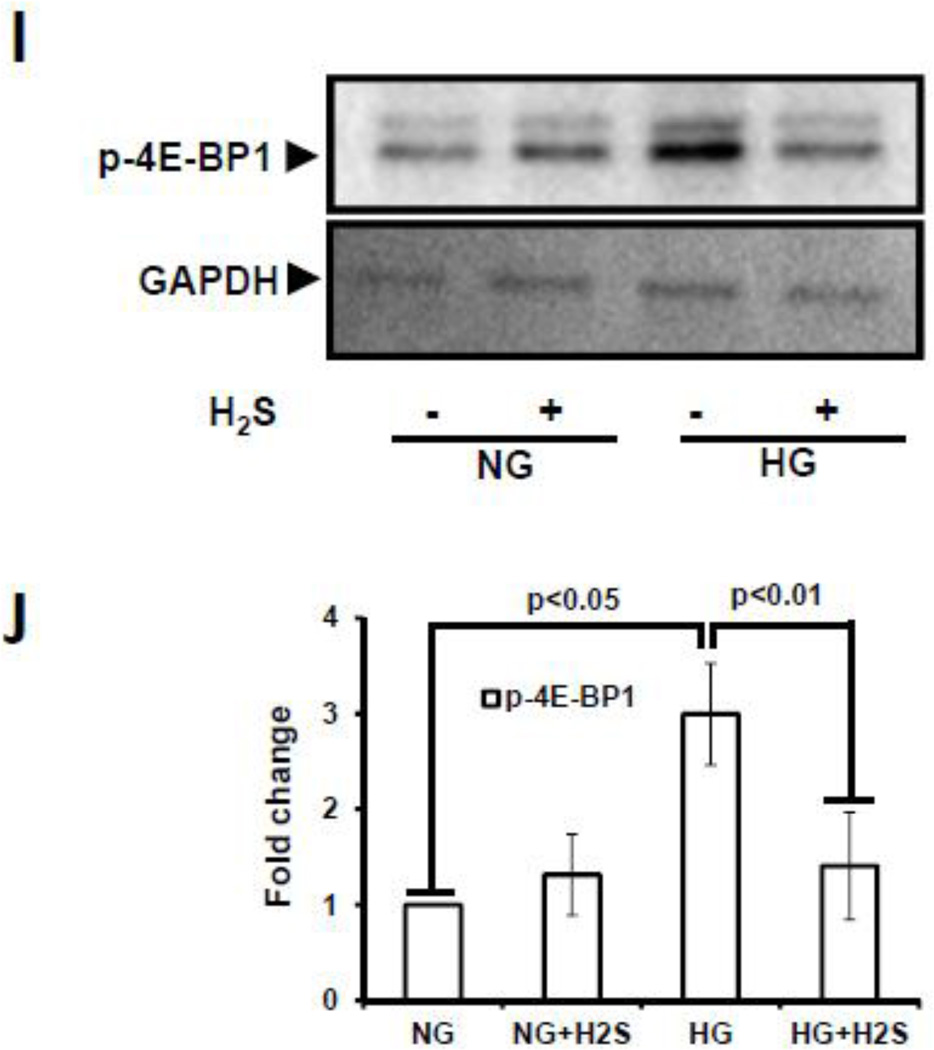

Protein expression for autophagy markers, mTOR, Atg5, Atg7 (A), and Atg3 and LC3A/B (C) were measured in MGECs. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (E and G) Gene expression of autophagy markers was detected by RT-PCR amplification using 2 µg of RNA from cells. GAPDH mRNA was used as loading control. The band intensity of protein (A and C) and mRNA (E and G) expression were quantified using ImageJ software and presented as fold change (B, D, F and H). Images are representative of single experiment and bar graphs represent mean ± s.e.m. from five independent experiments (n = 5). MGECs were incubated in NG or HG condition without or with H2S for 24 h. Protein expression of phospho-4E-BP1 was measured by Western blot analysis using GAPDH as control (I). Band intensities were quantified by ImageJ and presented as fold change (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3) (J).

Hyperglycemia induces mTORC1 activation which controls the synthesis of initiation and elongation factors of mRNA translation. In order to confirm mTORC1 activation, we measured the phosphorylation status of 4E-BP1 at serine 65 position. There was basal phosphorylation in NG cells which did not change with H2S treatment (Fig. 6I, J). In contrast, there was robust increase in 4E-BP1 phosphorylation in HG cells which was restored to NG levels following H2S treatment (Fig. 6I,J).

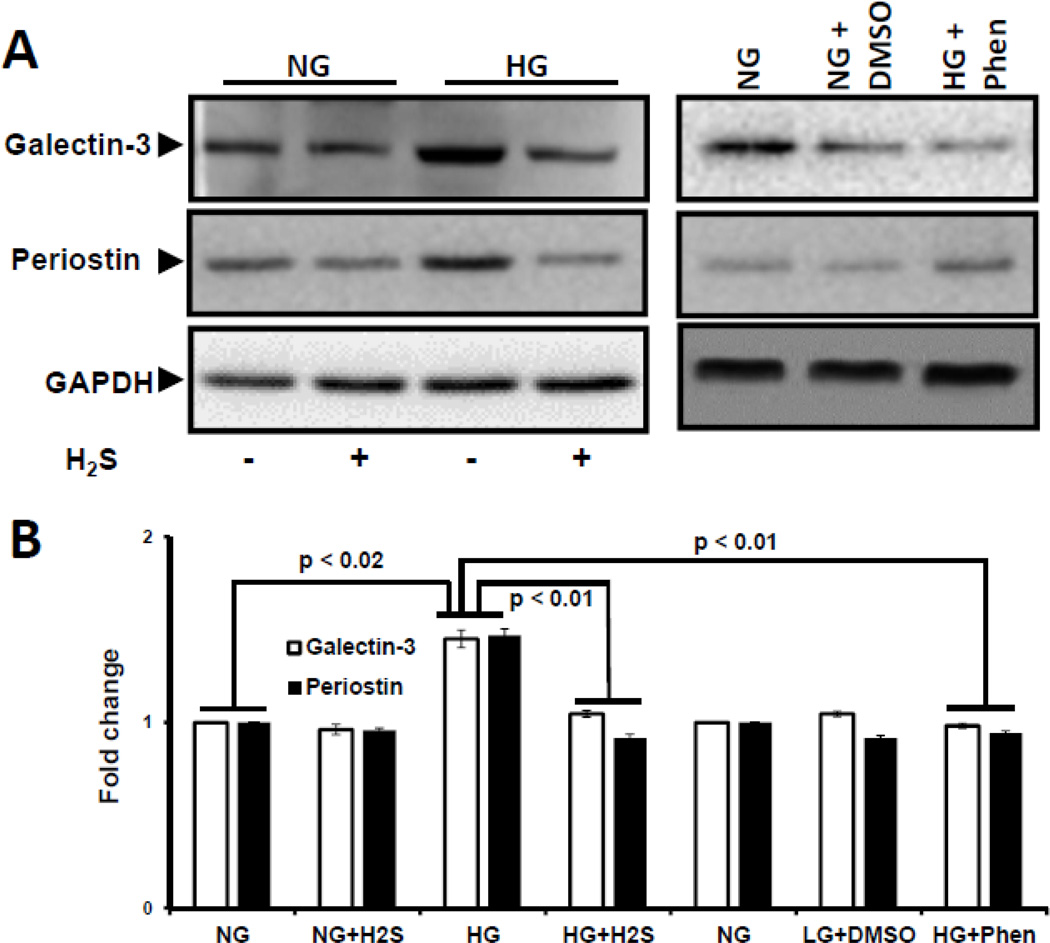

H2S decreases HG-induced Galectin-3 and Periostin overexpression

Accumulation of matricellular proteins is associated with matrix remodeling. We measured the expression of galectin-3 and periostin as surrogate markers for matrix remodeling. In HG cells, expression of both galectin-3 and periostin were increased (Fig. 7A,B) and treatment with H2S normalized their expression to the levels observed in NG cells (Fig. 7A,B). To determine if the increase in matrix protein expression is dependent upon AMPK activation, HG cells were treated with an AMPK activator, phenformin. As shown in Fig. 7, treatment with phenformin normalized expression of galectin-3 and periostin in HG cells. DMSO had no effect on expression of galectin-3 and periostin.

Figure 7. H2S-induced activation of AMPK decreased the expression of galectin-3 and periostin in hyperglycemia.

(A) Expression of matricellular proteins, galectin-3 and periostin, were measured by Western blot. Cells in NG/HG condition were treated without or with H2S and AMPK activator, Phenformin in DMSO. Phenformin reduced the expression of galectin-3 and periostin in HG condition. Cells treated with DMSO alone did not differ from NG condition. GAPDH was used as loading control. (B). Band intensities were quantified by ImageJ and presented as fold change (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5).

DISCUSSION

Several pathogenic processes contribute to the development of glomerular and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. A reduction in hydrogen sulfide has been reported to cause excess matrix protein deposition and hypertrophy in diabetic kidneys and exogenous administration of H2S ameliorated the effects of hyperglycemia [7]. Previously, we demonstrated that H2S treatment in HG reduced MMP-9-induced diabetic renal remodeling by downregulation of connexins [2]. However, the mechanism by which H2S mediates these effects is unknown. In the present study, we report a novel signaling mechanism of H2S-induced autophagy and reduction in matricellular protein synthesis in mouse glomerular endothelial cells (MGECs) under hyperglycemic (HG) condition. We show that hyperglycemia results in decreased cellular expression of CBS and CSE and H2S levels which in turn inhibited the activation of LKB1 and AMPK. Inactive AMPK further diminished autophagy and promoted synthesis and accumulation of matricellular proteins, galectin-3 and periostin. We show for the first time that administration of H2S in HG causes phosphorylation and activation of LKB1 by the formation of a heterotrimeric complex with STRAD and MO25 leading to AMPK activation, induction of autophagy, and degradation of matrix proteins.

In addition to its role as a modulator of cardiovascular and neuronal signaling, hydrogen sulfide has been shown to regulate renal function [23]. In diabetes, deficiency of hydrogen sulfide is associated with renal injury whereas, its supplementation has been reported to attenuate glomerular lesions and improve local blood flow in the capillaries around the proximal tubules [3, 24]. In addition, treatment of diabetic rats with H2S donor, NaHS, has been shown to decrease TGF-β mediated collagen IV synthesis in the kidney [25]. Further, Lee et al demonstrated that H2S administration to cultured glomerular epithelial cells reduces hypertrophy and matrix protein synthesis under hyperglycemic conditions [7]. More recently, we demonstrated that H2S deficiency in type 1 diabetic mice and mouse glomerular endothelial cells (MGECs) was associated with MMP-9-activation and renal remodeling and treatment with H2S abrogated the adverse effects [2]. The results from the present study confirms previous findings regarding decreased CBS/CSE levels and H2S during hyperglycemia and the beneficial effect that H2S provides in diabetic kidney disease. Interestingly, H2S treatment to HG cells increased the expression of CBS and CSE at protein and mRNA level. H2S exerts a variety of physiological functions in the body by several intracellular signaling mechanisms. In a recent study involving hydrogen peroxide-induced injury in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, NaHS treatment was reported to increase CSE expression and activity both at protein and mRNA level [26]. In another study involving unilateral ureteral obstruction induced renal fibrosis in mice; Jung et al. reported decreased expression of CBS and CSE in the kidney [27]. However, following NaHS treatment, the expression of CBS and CSE were found to be significantly increased [27].

Previous studies have demonstrated that administration of NaHS (H2S donor) increased the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide (NO) production in in vitro and in vivo experiments [28, 29]. In an earlier study on the role of H2S on cardiovascular tissue, Zhao W et al. showed that NO donor treatment increased H2S production in rat aorta and smooth muscle cells isolated from the aorta. This was associated with increased expression of CSE mRNA [30]. Although the exact mechanism of how nitric oxide increases the expression of CSE is not known, the author suggests this possibility as essential evidence for H2S-mediated physiological functions [31]. Further, emerging evidence suggests significant crosstalk between the three endogenous gasotransmitters, H2S, NO and carbon monoxide [32]. It is possible that such interactions could promote the upregulation of either enzymes leading to increased H2S production, however, further studies are required to unravel the underlying mechanisms.

It is well documented that AMPK plays a key role in maintaining glucose homeostasis. The activation of AMPK has multiple effects in several organs including increased glucose uptake by reducing insulin resistance, increasing fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis [33]. In mice fed with high-fat diet, reduction in renal AMPK activity was associated with an inflammatory response in the early stages of kidney disease and treatment with AMP activator, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribonucleoside prevented renal hypertrophy [34]. Recent studies provide evidence that H2S induces AMPK activation in hyperglycemia to modulate neuroinflammation, reduce oxidative stress and vascular inflammation [35, 36]. Further, in vitro studies on glomerular epithelial cells showed that NaHS treatment increased AMPK phosphorylation and inhibited excess protein synthesis due to hyperglycemia [7]. In agreement with the above studies, we found increased AMPK phosphorylation following H2S treatment. The activation of AMPK occurs mainly by two upstream kinases: a) calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β (CaMKKβ) and b) AMP-dependent liver kinase B1 (LKB1). Previous studies report that CaMKKβ accounts for H2S mediated AMPK phosphorylation in glomerular epithelial cells and BV2 microglia [7, 35]. In contrast, our results suggest that H2S-mediated AMPK phosphorylation occurs via LKB1 activation in glomerular endothelial cells. Although we did not study CaMKKβ mediated AMPK phosphorylation, transfection of MGECs with siRNA for LKB1 significantly inhibited phosphorylation of AMPK suggesting this as the predominant mechanism in mouse glomerular endothelial cells.

Liver kinase B1 is an upstream kinase of AMPK which is involved in maintaining cell polarity and suppression of inappropriate cell proliferation under stress conditions. The localization and activity of LKB1 is dependent on its interaction with two pseudokinases, STRADα and MO25 which is crucial for AMPK activation. STRADα directly associates with LKB1 at its kinase domain which allows for the translocation of LKB1 from the nucleus to cytoplasm [37] and MO25 binds to the C-terminal residue of STRAD and acts as a scaffold to support the formation of heterotrimeric complex (LKB1/STRAD/MO25) [38]. The loss of LKB1 activity in adult mouse liver leads to complete loss of AMPK activity and is associated with hyperglycemia [39, 40]. In the present study, H2S treatment in hyperglycemia was associated with the formation of LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex and AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. 2E and 4C). This was further confirmed by the inability of complex formation and activation of AMPK when MGECs were knocked down for LKB1, STRAD and MO25 genes under normoglycemia including H2S treatment (Fig 2F and G; Fig. 4D and E).

Autophagy is a highly conserved catabolic process which maintains cellular homeostasis under stress conditions by degradation and recycling intracellular components [41]. Autophagy begins with the formation of a phagophore membrane which is derived from endoplasmic reticulum and is followed by Atg5-Atg12 conjugation [42]. Ubiquitin-like enzymes, Atg7 and Atg10 play a key role in the activation and conjugation of Atg5-Atg12 which then complexes with Atg16L and recruits microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3B) [41]. Further cleavage and activation of LC3B-I by Atg7 is processed by Atg3 and phosphatidylethanolamine generating LC3B-II. The integration of LC3B-II enables fusion of membranes and engulfment of proteins and organelles for degradation [42]. Increased level of LC3B-II is an indicator of autophagy induction. In hyperglycemia, excess nutrient status causes downregulation of autophagy leading to accumulation of proteins in glomerular basement membrane and proximal tubules [43, 44]. Because AMPK is an energy sensor in the cell, during glucose sufficiency AMPK is inactive, whereas, its target, mTOR becomes activated causing phosphorylation of Ulk1 which in turn prevents the interaction between Ulk1 and AMPK thus inhibiting autophagy [45]. Our results showing increased mTOR expression and decreased autophagy markers (Fig. 6A–H) are in concurrence with these earlier reports. The phosphorylation of AMPK by H2S treatment increased the expression of Atg5, Atg7 and Atg3 and LC3B suggesting induction of autophagy.

Several studies have shown that mTOR signaling is involved in protein synthesis and renal hypertrophy [15, 46]. mTOR has been shown to regulate the initiation and elongation phases in the protein translation process. In vitro studies on human embryonic kidney cells has shown that pre-treatment with rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor significantly decreases protein synthesis implying a key role for mTOR signaling in this process [47]. In the present study, we confirmed increased 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, a downstream target of mTOR, suggesting mTORC1 activation during hyperglycemia and its reduction following H2S treatment. Furthermore, AMPK has been shown to control the phosphorylation of several other enzymes involved in protein synthesis. For example, when cardiomyocytes were treated with AMPK activators, metformin or 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribofuranoside protein synthesis was significantly inhibited [48]. During hyperglycemia, the combined effects of mTOR activation and AMPK inhibition enhances protein synthesis leading to basement membrane thickening and expansion of the mesangium [49]. Periostin and galectin-3 have been identified as markers associated with vascular remodeling and disease progression in diabetic nephropathy [50, 51]. In this study, we demonstrate that the expression of both proteins was markedly increased in HG condition suggesting their role in matrix remodeling and H2S treatment normalized their expression supporting our hypothesis that H2S has the potential to prevent renovascular remodeling caused by hyperglycemia.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that hyperglycemia impairs H2S production and AMPK phosphorylation. The activation of AMPK which is dependent on the activation of LKB1, an upstream kinase is reduced due to the inability of LKB1 to form a heterotrimeric complex (LKB1/STRAD/MO25). Inactive AMPK inhibited autophagy by upregulation of mTOR and increased matrix protein accumulation. We demonstrate for the first time that for H2S-induced AMPK activation, LKB1 requirement and the formation of heterotrimeric complex with STRAD and MO25 is essential and selective for glomerular endothelial cells. The downstream effects of AMPK activation inhibited protein synthesis and induced autophagy for clearance of excess matrix proteins to prevent matrix remodeling in HG condition.

Limitation of the study

Activation of AMPK is regulated mainly by calcium-dependent calmodulin kinase kinase beta (CamKKβ) and AMP-dependent liver kinase B1 (LKB1). Previous reports suggest that H2S mediated AMPK activation occurs via CamKKβ in glomerular epithelial cells and BV2 microglia [7, 35]. However, in a recent study involving human umbilical vein endothelial cells and bovine aortic endothelial cells, metformin induced AMPK phosphorylation required LKB1 for its activation [52]. Although our study shows that AMPK activation occurs via LKB1 phosphorylation in MGECs, whether the activation of AMPK under similar conditions occurs by CamKKβ remains to be investigated. However, the absence of LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex formation after knock down of respective genes suggests that this may be the predominant mechanism in MGECs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Mouse glomerular endothelial cells (MGECs) and complete media kit (Cat. No. M1168) were purchased from Cell Biologics, Inc. (Chicago, IL). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in complete media. Cells were plated onto six-well culture dishes and all experiments were carried out at 80–85% confluence.

Cell treatment

Cells were divided into two groups: Group 1: treated with 5 mM glucose; designated as normoglycemic or NG, and Group 2: treated with 25 mM glucose for 24 h; designated as diabetic or hyperglycemic or HG. Where reported, the groups were treated without or with NaHS (30 µM, as a source of instant H2S) for 24 h. At the end of experimentation, cells were washed with PBS, collected and used for various tests and analysis as reported.

Gene silencing by siRNA transfection

Pre-designed small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting STRAD, MO25, LKB1, AMPKα1/2, and control siRNAs were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The transfection procedure was performed using DNA transfection reagent (jetPRIME, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, MGECs were seeded onto a 6-well culture plates (TPP, USA) and allowed to reach 60% confluence. Transfection reagents were prepared by adding 200 µl of jetPRIME buffer, 100 pmoles of siRNA and 4 µl of jetPRIME reagent. After mixing, the final solution containing 10 nM of siRNA was added to the wells and allowed to grow for 24 h and followed by experimental conditions.

Antibodies and reagents

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), STE-20 related adapter protein α (STRAD), mouse protein 25 (MO25), phosphorylated LKB1 (p-LKB1), phosphorylated AMPK (p-AMPK), Galectin-3, Periostin, phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (p-4E-BP1, Ser 65); horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked anti-rabbit IgG antibody and siRNAs were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Atg3, anti-Atg5, anti-Atg7, anti-mTOR, and anti-GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Anti-LC3A/B antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). NaHS and other analytical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Phenformin hydrochloride was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO)

H2S measurement

H2S was measured from both cell extracts and culture media. After treatment, media was collected and kept in an air-tight tube to prevent H2S loss. Cells were extracted in ice-cold PBS, collected in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube, and sealed immediately with parafilm. H2S measurement was originally described by Stipanuk and Beck [53]. We used the modified protocol to measure acid-labile sulfur as described by Lu et al. [54]. Briefly, samples were sonicated and 100 µl aliquots were mixed with PBS (pH 7.4, 350 µL) and zinc acetate (1% W/V, 250 µL) in a micro-centrifuge tube. This was followed addition of N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate (20 mM, 133 µL) in 7.2 M HCl, and FeCl3 30 mM, 133 µL) in 1.2 M HCl. Tubes were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of trichloroacetic acid solution (10% w/v, 250 µL) and following centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and the absorbance was measured at 670 nm in a spectrophotometer. All samples were assayed in duplicate in each experiment and H2S was calculated against a calibration curve of known concentrations of NaHS (0.01 – 100 µmol/L).

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted using RIPA buffer (Boston BioProducts, Worcester, MA) with 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Following measurement of protein concentration, 100 µg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and electro-transferred to PVDF membrane. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies against CBS, CSE, STRAD, MO25, p-LKB1, p-AMPK, autophagy markers, galectin-3 and periostin, p-4E-BP1 and HRP-conjugated appropriate secondary antibodies. Blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Band intensity was analyzed by ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/)

RNA extraction and quality assessment

MGECs were washed with ice-cold PBS and RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent isolation kit following manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Cells from six separate wells (in a 12 well plate) of the same group were pooled, and used as n=1. The quality of total RNA was measured by NanoDrop ND-1000 and only high quality RNA (260/280- 2.00 and 260/230-1.80) was used for reverse transcriptase PCR.

Semi-Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (RT-PCR)

The total RNA (2 µg) was reverse transcribed by two-step process using Promega ImProm RT-PCR kit. Incubation of RNA with oligo dT at 70°C for 5.00 min. The RT cycle was 25°C for 2.00 min, 42°C for 50.00 min, 75°C for 5.00 min, 4°C forever. PCR program for amplification of cDNA was 95°C for 10.00 min, (95°C for 00.30 min, 55°C for 1.00 min, 72°C for 00.30 min) × 46 cycles, 95°C for 1.00 min, 55°C for 00.30 min and 95°C for 00.30 min. The primer sequences and their accession numbers are presented in Table-1.

Table 1.

Primers used to amplify mRNAs encoding genes for H2S production, pseudokinases, autophagy markers and GAPDH

| Primer | Accession no. | Forward Primer (5’-3’) | Reverse Primer (3’-5’) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBS | NM_144855.3 | TGCGGAACTACATGTCCAAG | TTGCAGACTTCGTCTGATGG |

| CSE | AY083352.1 | GACCTCAATAGTCGGCTTCGTT | CAGTTCTGCGTATGCTCCGTAA |

| Stradα (STRAD) | NM_001252449.1 | CACAACTTTGTGGAACAGTG | AAGATTCCACTGTGATCCTG |

| Cab39 (MO25) | NM_133781.4 | CGGAGACGAAGCAGAGA | CTTGTGAGACTTGCCAAATG |

| mTOR | NM_020009.2 | CATTCATTGGAGACGGTTTG | AGATGTTGCCTGCTTGATAA |

| Atg5 | NM_053069.5 | ACTGGGACTTCTGCTCC | GTTCTTCCTTCAACCAAAGC |

| Atg7 | NM_001253717.1 | CATACAGGCCTCTGGAAAAT | CTACTGTTCTTACCAGCCTC |

| Atg3 | NM_026402.3 | TCCTGTCAGAAGGTTCTAGT | GCTAGTTCTGACACTGGTAG |

| Map1lc3a (LC3A) | NM_025735.3 | AAGAAACCTTCGGCTTCTGAGTC | AAATGACCACAGATCCATACACC |

| Map1lc3a (LC3B) | NM_026160.4 | GGTAGACTGCAAGTCCAATGCTC | CAGGAATCCTTACTGATCGCAC |

| GAPDH | M32599.1 | TAAATTTAGCCCGTGTGACCT | AGGGGAAAGACTGAGAAAAC |

CBS: cystathionine beta synthase, CSE: cystathionine gamma lyase, Strad α: STE20-related kinase adaptor alpha, Cab39: calcium binding protein 39 (gene for MO25), mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin, Atg5: autophagy related 5, Atg7: autophagy related 7, Atg3: autophagy related 3, LC3A: microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 α, LC3B: microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 β, GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3 phosphate dehydrogenase

Immunostaining

Cells in 8-well chamber slide were gene silenced with appropriate siRNAs, and incubated in NG or HG condition without or with H2S treatment as shown in the figures. Immunostaining was performed according to the standard protocol. Briefly, after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, cells were premeabilized with PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for detection of proteins in the cytoplasmic domain (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Primary antibodies were applied overnight and included STRAD, MO25, p-LKB1 and p-AMPK. Secondary antibodies labeled with either Alexa Fluor-488 or - 594 (Invitrogen) were applied for immunodetection of proteins or their phosphorylated forms. Stained slides were visualized and analyzed for fluorescence intensity under a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus FluoView1000) using appropriate filter.

Determination of AMPK activity

AMPK activity assay was measured as described previously [55]. Cells were washed twice with PBS, pH 7.4, and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 10 µl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail 1, 10 µl/ml phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1, 0.5% Nonidet-40, and 1% Triton X-100). The lysates were sonicated for 3 × 10 seconds on ice at 10 s interval in-between each sonic pulse. AMPK activity was determined according to the manufacturer's protocol (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Briefly, 1mL of working solution containing γ32 P-ATP: 10 µl γ32 P-ATP 10 mCi/ml (specific activity 158–160 CPM/pmole of ATP), 10 µl of ATP (100 mM), 25 µl of magnesium chloride (MgCl2) 1 M, 955 µl of HEPES-Brij buffer (50 mM Na HEPES, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 0.2 g Brij 35, 0.02%) was prepared. A positive (10 µl of working solution, 10 µl 1 mM AMP and 10 µl SAMS peptide 100 µM) and negative (10 µl of working solution, 10 µl 1 mM AMP and 10 µl HEPES-Brij buffer) master mix solution was prepared prior to the experiment (30 µL for each sample). The master mix solutions, one negative and two positive were added to three sample aliquots from the same group. Activated AMPK (50 mU, Richmond, VC, Canada) was added to 2 separate tubes to serve as control. The samples were transferred to a 30°C shaker bath for 20 min. at 350 RPM. After incubation, each sample was transferred to a numbered P81 phosphocellulose paper. After drying, the paper were washed thrice with 1% (v/v) phosphoric acid and finally with acetone. After re-drying they were transferred to scintillation vials. Bound radioactivity was quantitated by the addition of 3 ml of scintillation fluid and read in a scintillation counter (Pharmacia). A substrate control was measured to correct for nonspecific binding along with the samples. AMPK activity was measured by subtracting control counts from the sample. The activity is expressed as pmoles phosphate incorporated into the AMPK substrate peptide per minute per milligram protein.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Co-immunoprecipitation was followed by Western blot to confirm protein-protein interactions with all possible combinations between LKB 1, STRAD and MO25. Briefly, 100 µg of protein was mixed with antibodies to LKB1, STRAD and MO25 separately and the final volume made up to 150 µl with 1x PBS. Gelatin-Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology Ab Uppsala, Sweden) pre-soaked in PBS was added to the protein-antibody mixture and incubated overnight at 4 °C in a rotating shaker. The tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 15 minutes and supernatant discarded. The pellet was blocked with 1% BSA for 45 minutes and washed thrice with ice-cold PBS. Washed pellets were re-suspended in 25 µl of 6x sample buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 5 minutes to dissociate bound proteins. The sample buffer was loaded to SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted and probed separately with antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Primer of Biostatistics (Ver. 7; McGraw-Hill, Blacklick, OH). All results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Multiple comparisons were analyzed using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Mann–Whitney rank sum test was performed for ordinal data. The threshold for significance was p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Hyperglycemia (HG) is associated with decreased CBS, CSE and H2S production

In HG, p-LKB1 and p-AMPK are decreased

HG is associated with impaired autophagy and increased matrix accumulation

H2S-induced AMPK activation involves LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex formation in MGECs

H2S-induced AMPK activation normalized autophagy and decreased matrix remodeling

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was supported, in part, by NIH grant HL-104103.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There is no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

SK, SBP and US designed research work. SK and SJK collected data. SBP and SK wrote the manuscript. SBP and US edited for submission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kimura H. The physiological role of hydrogen sulfide and beyond. Nitric Oxide. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kundu S, Pushpakumar SB, Tyagi A, Coley D, Sen U. Hydrogen sulfide deficiency and diabetic renal remodeling: role of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E1365–E1378. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00604.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto J, Sato W, Kosugi T, Yamamoto T, Kimura T, Taniguchi S, Kojima H, Maruyama S, Imai E, Matsuo S, Yuzawa Y, Niki I. Distribution of hydrogen sulfide (H(2)S)-producing enzymes and the roles of the H(2)S donor sodium hydrosulfide in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:32–40. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0670-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardie DG. AMPK: a key regulator of energy balance in the single cell and the whole organism. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(Suppl 4):S7–S12. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alessi DR, Sakamoto K, Bayascas JR. LKB1-dependent signaling pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:137–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee MJ, Feliers D, Mariappan MM, Sataranatarajan K, Mahimainathan L, Musi N, Foretz M, Viollet B, Weinberg JM, Choudhury GG, Kasinath BS. A role for AMP-activated protein kinase in diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F617–F627. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00278.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HJ, Mariappan MM, Feliers D, Cavaglieri RC, Sataranatarajan K, Abboud HE, Choudhury GG, Kasinath BS. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits high glucose-induced matrix protein synthesis by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4451–4461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eid AA, Ford BM, Block K, Kasinath BS, Gorin Y, Ghosh-Choudhury G, Barnes JL, Abboud HE. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) negatively regulates Nox4-dependent activation of p53 and epithelial cell apoptosis in diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37503–37512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.136796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dugan LL, You YH, Ali SS, Diamond-Stanic M, Miyamoto S, DeCleves AE, Andreyev A, Quach T, Ly S, Shekhtman G, Nguyen W, Chepetan A, Le TP, Wang L, Xu M, Paik KP, Fogo A, Viollet B, Murphy A, Brosius F, Naviaux RK, Sharma K. AMPK dysregulation promotes diabetes-related reduction of superoxide and mitochondrial function. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:4888–4899. doi: 10.1172/JCI66218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satriano J, Sharma K. Autophagy and metabolic changes in obesity-related chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(Suppl 4):v29–v36. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meijer AJ, Codogno P. AMP-activated protein kinase and autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;3:238–240. doi: 10.4161/auto.3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meley D, Bauvy C, Houben-Weerts JH, Dubbelhuis PF, Helmond MT, Codogno P, Meijer AJ. AMP-activated protein kinase and the regulation of autophagic proteolysis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:34870–34879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang L, Zhou Y, Cao H, Wen P, Jiang L, He W, Dai C, Yang J. Autophagy attenuates diabetic glomerular damage through protection of hyperglycemia-induced podocyte injury. PloS one. 2013;8:e60546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamahara K, Kume S, Koya D, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Chin-Kanasaki M, Araki H, Isshiki K, Araki S, Haneda M, Matsusaka T, Kashiwagi A, Maegawa H, Uzu T. Obesity-mediated autophagy insufficiency exacerbates proteinuria-induced tubulointerstitial lesions. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2013;24:1769–1781. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CH, Inoki K, Guan KL. mTOR pathway as a target in tissue hypertrophy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:443–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Wang J, Qin L, Shou Z, Zhao J, Wang H, Chen Y, Chen J. Rapamycin prevents early steps of the development of diabetic nephropathy in rats. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:495–502. doi: 10.1159/000106782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakaguchi M, Isono M, Isshiki K, Sugimoto T, Koya D, Kashiwagi A. Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin attenuates renal hypertrophy in the early diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fryer LG, Parbu-Patel A, Carling D. The Anti-diabetic drugs rosiglitazone and metformin stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase through distinct signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25226–25232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Shon E, Kim CS, Kim JS. Renal podocyte injury in a rat model of type 2 diabetes is prevented by metformin. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:210821. doi: 10.1155/2012/210821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pushpakumar SB, Kundu S, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC, Sen U. Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibition Mitigates Renovascular Remodeling in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Physiological reports. 2013;1:e00063. doi: 10.1002/phy2.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orlova KA, Parker WE, Heuer GG, Tsai V, Yoon J, Baybis M, Fenning RS, Strauss K, Crino PB. STRADalpha deficiency results in aberrant mTORC1 signaling during corticogenesis in humans and mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:1591–1602. doi: 10.1172/JCI41592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godlewski J, Nowicki MO, Bronisz A, Nuovo G, Palatini J, De Lay M, Van Brocklyn J, Ostrowski MC, Chiocca EA, Lawler SE. MicroRNA-451 regulates LKB1/AMPK signaling and allows adaptation to metabolic stress in glioma cells. Molecular cell. 2010;37:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia M, Chen L, Muh RW, Li PL, Li N. Production and actions of hydrogen sulfide, a novel gaseous bioactive substance, in the kidneys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:1056–1062. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.149963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue R, Hao DD, Sun JP, Li WW, Zhao MM, Li XH, Chen Y, Zhu JH, Ding YJ, Liu J, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulfide treatment promotes glucose uptake by increasing insulin receptor sensitivity and ameliorates kidney lesions in type 2 diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:5–23. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan P, Xue H, Zhou L, Qu L, Li C, Wang Z, Ni J, Yu C, Yao T, Huang Y, Wang R, Lu L. Rescue of mesangial cells from high glucose-induced over-proliferation and extracellular matrix secretion by hydrogen sulfide. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2119–2126. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen YD, Wang H, Kho SH, Rinkiko S, Sheng X, Shen HM, Zhu YZ. Hydrogen sulfide protects HUVECs against hydrogen peroxide induced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. PloS one. 2013;8:e53147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung KJ, Jang HS, Kim JI, Han SJ, Park JW, Park KM. Involvement of hydrogen sulfide and homocysteine transsulfuration pathway in the progression of kidney fibrosis after ureteral obstruction. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1989–1997. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen PH, Fu YS, Wang YM, Yang KH, Wang DL, Huang B. Hydrogen sulfide increases nitric oxide production and subsequent s-nitrosylation in endothelial cells. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:480387. doi: 10.1155/2014/480387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King AL, Polhemus DJ, Bhushan S, Otsuka H, Kondo K, Nicholson CK, Bradley JM, Islam KN, Calvert JW, Tao YX, Dugas TR, Kelley EE, Elrod JW, Huang PL, Wang R, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide cytoprotective signaling is endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide dependent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:3182–3187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321871111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang R. Two's company three's a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2002;16:1792–1798. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0211hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polhemus DJ, Lefer DJ. Emergence of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous gaseous signaling molecule in cardiovascular disease. Circulation research. 2014;114:730–737. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang BB, Zhou G, Li C. AMPK: an emerging drug target for diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2009;9:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decleves AE, Mathew AV, Cunard R, Sharma K. AMPK mediates the initiation of kidney disease induced by a high-fat diet. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011;22:1846–1855. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou X, Cao Y, Ao G, Hu L, Liu H, Wu J, Wang X, Jin M, Zheng S, Zhen X, Alkayed NJ, Jia J, Cheng J. CaMKKbeta-Dependent Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Is Critical to Suppressive Effects of Hydrogen Sulfide on Neuroinflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manna P, Jain SK. L-cysteine and hydrogen sulfide increase PIP3 and AMPK/PPARgamma expression and decrease ROS and vascular inflammation markers in high glucose treated human U937 monocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:2334–2345. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baas AF, Boudeau J, Sapkota GP, Smit L, Medema R, Morrice NA, Alessi DR, Clevers HC. Activation of the tumour suppressor kinase LKB1 by the STE20-like pseudokinase STRAD. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:3062–3072. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boudeau J, Scott JW, Resta N, Deak M, Kieloch A, Komander D, Hardie DG, Prescott AR, van Aalten DM, Alessi DR. Analysis of the LKB1-STRAD-MO25 complex. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6365–6375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viollet B, Foretz M, Guigas B, Horman S, Dentin R, Bertrand L, Hue L, Andreelli F. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in the liver: a new strategy for the management of metabolic hepatic disorders. The Journal of physiology. 2006;574:41–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw RJ, Lamia KA, Vasquez D, Koo SH, Bardeesy N, Depinho RA, Montminy M, Cantley LC. The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science. 2005;310:1642–1646. doi: 10.1126/science.1120781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizushima N. Physiological functions of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;335:71–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kume S, Thomas MC, Koya D. and diabetic nephropathy. Nutrient sensing, autophagy, Diabetes. 2012;61:23–29. doi: 10.2337/db11-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park IS, Kiyomoto H, Abboud SL, Abboud HE. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta and type IV collagen in early streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetes. 1997;46:473–480. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen JK, Chen J, Neilson EG, Harris RC. Role of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in compensatory renal hypertrophy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2005;16:1384–1391. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herbert TP, Kilhams GR, Batty IH, Proud CG. Distinct signalling pathways mediate insulin and phorbol ester-stimulated eukaryotic initiation factor 4F assembly and protein synthesis in HEK 293 cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11249–11256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan AY, Soltys CL, Young ME, Proud CG, Dyck JR. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits protein synthesis associated with hypertrophy in the cardiac myocyte. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32771–32779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lieberthal W, Levine JS. The role of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in renal disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20:2493–2502. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Satirapoj B, Wang Y, Chamberlin MP, Dai T, LaPage J, Phillips L, Nast CC, Adler SG. Periostin: novel tissue and urinary biomarker of progressive renal injury induces a coordinated mesenchymal phenotype in tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2702–2711. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kikuchi Y, Kobayashi S, Hemmi N, Ikee R, Hyodo N, Saigusa T, Namikoshi T, Yamada M, Suzuki S, Miura S. Galectin-3-positive cell infiltration in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:602–607. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie Z, Dong Y, Scholz R, Neumann D, Zou MH. Phosphorylation of LKB1 at serine 428 by protein kinase C-zeta is required for metformin-enhanced activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase in endothelial cells. Circulation. 2008;117:952–962. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.744490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stipanuk MH, Beck PW. Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. The Biochemical journal. 1982;206:267–277. doi: 10.1042/bj2060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu M, Liu YH, Goh HS, Wang JJ, Yong QC, Wang R, Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits plasma renin activity. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2010;21:993–1002. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009090949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim CT, Lolli F, Thomas JD, Kola B, Korbonits M. Measurement of AMP-activated protein kinase activity and expression in response to ghrelin. Methods Enzymol. 2012;514:271–287. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381272-8.00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.