Abstract

Objectives

To describe the full spectrum of symptom exacerbations defined by interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome patients as flares, and to investigate their associated health-care utilization and bother at two sites of the Trans-Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (Trans-MAPP) Epidemiology and Phenotyping study.

Patients and methods

Participants completed a flare survey that asked them: 1) whether they had ever had flares (“symptoms that are much worse than usual”) that lasted <1 hr, >1 hr and <1 day, and >1 day; and 2) for each duration of flare, to report their: a) average length and frequency; b) typical levels of urologic and pelvic pain symptoms; and c) levels of health-care utilization and bother.

We compared participants' responses to their non-flare Trans-MAPP values and across flares using generalized linear mixed models.

Results

Seventy six of 85 participants (89.4%) completed the flare survey, 72 of whom reported having flares (94.7%).

Flares varied widely in terms of their duration (seconds to months), frequency (several times per day to once per year or less), and intensity and type of symptoms (e.g., pelvic pain versus urologic symptoms).

Flares of all duration were associated with greater pelvic pain, urologic symptoms, disruption to participants' activities, and bother, with increasing severity of each of these factors as the duration of flares increased. Days-long flares were also associated with greater health-care utilization.

In addition to duration, symptoms (pelvic pain, in particular) were also significant determinants of flare-related bother.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that flares are common and associated with greater symptoms, health-care utilization, disruption, and bother. Our findings also inform the characteristics of flares most bothersome to patients (i.e., increased pelvic pain and duration), and thus of greatest importance to consider in future research on flare prevention and treatment.

Introduction

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) are chronic, debilitating syndromes characterized by bladder and/or pelvic pain, and irritative urologic symptoms, such as urinary urgency and frequency. Although the natural history of these urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPSs) is widely believed to include symptom exacerbations (frequently referred to as “flares” or “flare-ups” [1-6]), very few studies have described these flares. In our previous small, longitudinal study designed to quantify symptom changes during flares, particularly those lasting >1 day [7], we found unexpectedly that some participants reported flares lasting only a few minutes. As we are not aware of any references to flares of this short duration in the published literature – only flares lasting at least a few hours to several days or weeks have been referenced [1, 8, 9] – we conducted an exploratory study at two sites of the ongoing Trans-Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Epidemiology and Phenotyping (EP) study to examine the full spectrum of UCPPS flares, and to determine which of these flares warrant further study based on their associated health-care utilization and, more importantly, degree of bother to participants. This type of descriptive information that draws upon patient experiences is critical to inform future studies of flare prevention, treatment, and management.

Patients and Methods

Study population and design

The Trans-MAPP EP Study is a one-year, prospective observational study designed to characterize the treated natural history of IC/BPS and CP/CPPS to identify subgroups of patients that may lead to a better understanding of the causes, clinical course, and treatment response in future clinical trials. The study design consists of: 1) three in-clinic visits (baseline, 6-months, and 12-months), at which time participants complete a battery of questionnaires and provide biologic specimens; and 2) shorter bi-weekly online assessments. To be eligible for the Trans-MAPP study, all participants must report a response of ≥1 on a scale of 0-10 for pain, pressure, or discomfort associated with their bladder/prostate and/or pelvic region in the previous two weeks. IC/BPS participants (women and men) are also required to report these symptoms, as well as lower urinary tract symptoms, for the majority of time in the previous three months, whereas CP/CPPS participants must report pain or discomfort in the perineum, testicles, tip of their penis, below their waist, with urination, with ejaculation, with bladder filling, or relieved by voiding for the majority of time in any three of the previous six months. Additional eligibility criteria are provided in reference 7 and Appendix Table 1. Each of the main sites, including Washington University, was asked initially to recruit 30 female and 30 male participants. The University of Alabama sub-site followed an abbreviated protocol, consisting of the baseline visit only, and with a lower recruitment goal (n=30 participants of any sex).

For the present study, we invited all participants enrolled at the Washington University and University of Alabama sites to complete an additional, brief survey on flares. To avoid over-burdening participants at their baseline visit, we asked participants to complete this survey at the 6-month visit at the Washington University site. Participants at the University of Alabama completed this survey at their baseline visit because they attended only one study visit. All participants enrolled from the start of the study (February, 2010) through March 2013 were included in the present analysis.

This study was approved by the Washington University and University of Alabama Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). The parent study was approved by the IRB at each participating institution and the data coordinating center. All participants provided written informed consent.

Flare survey

To complement ongoing work in the parent Trans-MAPP study and to allow for comparisons with responses provided by participants when they were not experiencing a flare, we based many of the survey questions on questionnaires administered at all biweekly Trans-MAPP assessments: the Brief Flare Risk Factor Questionnaire, a questionnaire developed for the Trans-MAPP study; the male and female Genitourinary Pain Indices [10], 0-10 point scales for urologic and pelvic pain symptoms used in previous IC/BPS trials [11], and questions about their most bothersome symptom and health-care utilization. Specifically, we asked participants whether they had ever had flares, defined as “urologic or pelvic pain symptoms that are much worse than usual,” that lasted <1 hour, >1 hour but <1 day, and >1 day. For each duration of flare to which they responded affirmatively, we also asked participants to report their: 1) average length and frequency; 2) typical levels of pelvic pain, urinary urgency, frequency, overall urologic and pelvic pain symptoms, and overall pain symptoms that were not urologic or pelvic (e.g., back pain) on scales of 0-10; 3) most bothersome symptom; 4) typical health-care and self-management activities; and 5) the degree to which: a) their usual activities were disrupted; b) they thought about their symptoms; and c) they were bothered in general by their flares (none, only a little, some, and a lot, Appendix 2).

With the flare duration category of >1 hour to <1 day, we had intended to explore flares lasting only a few hours. However, when we examined the typical duration of flares in this category, we found that some flares were longer than typical waking hours during a day and might be more appropriately classified as one day-long flares. Therefore, for comparisons across flares, we divided responses to the question on flares lasting >1 hour to <1 day into two categories based on participants' responses to the question on typical length of each flare, i.e., less than the majority of typical waking hours in one day (≤50% of 16 hours=8 hours, “hours-long”) and more than the majority of typical waking hours in one day (>8 hours, “one day-long”).

Statistical analysis

To investigate the change in symptoms, most bothersome symptom, health-care utilization, and bother during flares, we compared participants' responses on the flare survey to their responses to the same questions on the Trans-MAPP questionnaires completed: 1) closest in time to the flare survey; and 2) when participants were not experiencing a flare; eight participants did not have non-flare comparison data. We performed these analyses using generalized linear mixed models to account for multiple observations per participant (i.e., one non-flare and at least one flare value per participant). We did not use methods such as simple ANOVA or chi-squared tests because these should be used only for independent data (i.e., only one value per participant); however, estimates from generalized linear models can be interpreted in the same way as those from a simple ANOVA or chi-squared test. We also used mixed models to investigate flare characteristics (i.e., symptoms and duration) independently associated with health-care utilization and bother. Finally, we conducted regression classification tree analyses [12] to explore the possibility that specific combinations of symptoms and duration (e.g., short and painful flares, long and painful flares) might influence flare-related bother, defined as being bothered “a lot” by flares. We used jack-knifing to select our samples (n=1,000) and we selected one flare per participant in each sample to account for multiple flare values per participant. We performed all analyses using either SAS version 9.3 (SAS, Cary, NC) or R version 2.15.1.

Results

Seventy six (46 female and 30 male) of 85 participants completed the flare survey (89.4%; 90.2% of women and 88.2% of men). Participants ranged widely in age (18.9-80.0 years) but tended to be Caucasian (88.2%) and to meet the MAPP IC/BPS criteria (100% of women by definition; 86.7% of men, Table 1). At baseline, female participants reported having had their condition for a longer period of time than male participants. They also reported more severe urologic and pelvic pain symptoms when not experiencing a flare, and were non-significantly more likely to report symptoms of a non-urological associated syndrome.

Table 1. Characteristics of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) participants, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, 2010-2013.

| All (n=76) | Female (n=46) | Male (n=30) | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age (years, mean (range)) | 47.7 (18.9 -80.0) | 46.6 (18.9 - 75.8) | 49.4 (26.6 - 80.0) | 0.45 |

| Caucasian (%) | 88.2 | 89.1 | 86.7 | 0.73 |

| Met IC/BPS criteria at baseline (%)2 | 94.7 | 100.0 | 86.7 | 0.02 |

| Duration of symptoms at baseline (years, mean (range)) | 13.3 (0.2 - 54.2) | 16.4 (0.2 - 52.0) | 8.6 (0.9 - 54.2) | 0.01 |

| Non-flare symptom levels (mean (range)): | ||||

| Pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort in the past two weeks (on a scale of 0-10) | 4.2 (0.0 - 10.0) | 4.9 (0.0 - 10.0) | 3.2 (0.0 - 9.0) | 0.007 |

| Urgency in the past two weeks (on a scale of 0-10) | 3.9 (0.0 - 10.0) | 4.8 (0.0 - 10.0) | 2.6 (0.0 - 8.0) | 0.001 |

| Frequency in the past two weeks (on a scale of 0-10) | 4.0 (0.0 - 10.0) | 4.9 (0.0 - 10.0) | 2.7 (0.0 - 9.0) | 0.002 |

| Genitourinary pain index (on a scale of 0-23) | 10.5 (0.0 - 22.0) | 11.6 (0.0 - 22.0) | 9.0 (0.0 - 20.0) | 0.06 |

| Interstitial cystitis symptom index (on a scale of 0-20) | 8.7 (0.0 - 18.0) | 10.4 (3.0 - 18.0) | 6.4 (0.0 - 16.0) | 0.0002 |

| Interstitial cystitis problem index (on a scale of 0-16) | 7.0 (0.0 - 16.0) | 8.8 (1.0 - 16.0) | 4.8 (0.0 - 14.0) | 0.0002 |

| Flare at baseline (%) | 33.0 | 35.6 | 30.0 | 0.62 |

| Presence of non-urological associated syndromes (%):3 | ||||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 26.8 | 28.6 | 24.1 | 0.68 |

| Fibromyalgia | 9.9 | 14.3 | 3.5 | 0.23 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 12.7 | 19.1 | 3.5 | 0.07 |

| Any associated syndrome | 38.0 | 45.2 | 27.6 | 0.13 |

P-values were calculated by Student's t-tests or chi-squared tests, as appropriate.

Defined as an unpleasant sensation of pain, pressure, or discomfort perceived to be related to the bladder/prostate and/or pelvic region, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms, for the majority of time in the three months before baseline.

Assessed by the Complex Medical Symptoms Inventory[15]

Spectrum of duration and frequency of flares

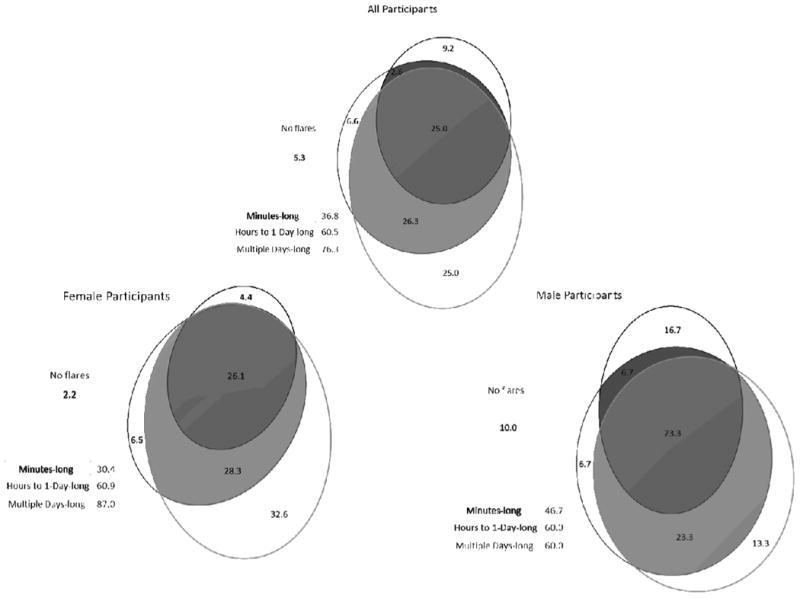

Of the 76 participants who completed the flare survey, 72 reported ever having had a flare (94.7%; 97.8% of women and 90.0% of men, Figure 1). Overall, 36.8% of participants reported ever having flares lasting <1 hour (“minutes-long”), 60.5% reported flares lasting >1 hour and <1 day (“hours- to one day-long”), and 76.3% reported flares lasting >1 day (“multiple days-long”). This distribution of flare duration differed by sex; female participants were more likely to report days-long flares and less likely to report minutes-long flares than men (p=0.012). This difference was not explained by sex-based differences in meeting the MAPP IC/BPS criteria, the duration of participants' condition, or the presence of non-urological associated syndromes (data not shown); however, it did attenuate slightly when we adjusted for participants' overall non-flare pain and urologic symptom severity as markers of the general state of their condition (p=0.05-0.14). When we examined distinct patterns of flares, 18.4% of participants reported exclusively shorter flares ranging from minutes to one day, 25.0% reported exclusively days-long flares, and 51.3% reported flares ranging from minutes or hours to days. The distribution of exact flare length by flare duration category is presented in Appendix Table 3.

Figure 1.

Distribution of flare duration by sex among 76 participants with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and/or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2010-2013 The four circles of each diagram represent participants who reported never having experienced a flare (“no flares”) or participants who reported having experienced one of the following durations of flares (“minutes-long flares”: less than an hour long; “hours to 1-day-long flares”: more than an hour but less than a day long; or “multiple days-long flares”: more than a day long). The size of each circle is proportional to the percentage of participants who reported no flares or each duration of flare, and the number written within the circle indicates this percentage. Where the circles overlap indicates where participants reported more than one duration of flare. For instance, 9.2% of all participants reported minutes-long flares only; 2.6% of participants reported both minutes-long and hours to 1-day-long flares, but not multiple-days long flares; and 25.0% of participants reported flares of all three durations. The total percentage of participants who reported each duration of flare is presented in the legend. For instance, 36.8% of participants (the sum of 9.2, 2.6, and 25.0%) reported minutes-long flares.

With respect to the frequency of flares, female participants reported minutes-long flares a median of once/week up to 10 times/week, whereas male participants reported minutes-long flares a median of twice/week up to 42 times/week (or 6 times/day, p=0.098, Appendix Table 3). Women and men reported similar numbers of hour-long flares (median of once/week), whereas women appeared to report slightly fewer one day-long flares (0.2 versus 0.5 times/week) and slightly more multiple days-long flares than men (1.5 versus 0.5 times/month, p=0.027). Finally, when we summed the number of hours that participants spent in a flare during a typical week, women reported a median of 21 hours (range: 0.01-131) and men reported a median of 8 hours (range: 0.003-124, p=0.51).

Symptoms during flares of varying duration

Considering the change in symptoms during flares, pelvic pain, urgency, and overall urologic and pelvic pain symptoms were significantly worse at the time of flares of all duration, with the exception of hours-long flares; only pelvic pain was significantly worse during these flares (Table 2). Frequency was significantly worse during days-long flares, but not during shorter flares. Comparing flares by duration, pelvic pain and frequency worsened significantly, and urgency and overall urologic and pelvic pain symptoms worsened non-significantly with increasing duration of flares. Non-urologic pain symptoms appeared to be no different or slightly better during flares. Irrespective of whether or not participants were experiencing a flare, pelvic pain was the most bothersome symptom reported. However, participants were more likely to report pelvic pain as their most bothersome symptom during a flare than when they were not experiencing a flare (76.5% versus 65.6%, p=0.048). This likelihood did not vary by duration of flare.

Table 2.

Urologic, and pelvic and non-pelvic pain symptoms1 by flare status and duration among 64 participants with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and/or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2010-2013

| Non-Flare (n=64) | Flare duration | p-value2 | p-value3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Minutes-long (n=26) | Hours-long (n=24) | One day-long (n=16) | Multiple days-long (n=51) | ||||

| Typical symptom severity (on a scale of 0-10, mean (range)): | |||||||

| Pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort | 4.3 (0 – 10) | 5.2 (0 – 10)** | 6.0 (2 – 10)**** | 7.0 (3 – 10)**** | 6.9 (2 – 10)**** | <0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| Urinary urgency | 4.0 (0 – 10) | 5.2 (0 – 10)**** | 4.3 (0 – 10) | 5.6 (0 – 10)**** | 5.7 (0 – 10)**** | <0.0001 | 0.21 |

| Frequency | 4.1 (0 – 10) | 3.9 (0 – 10) | 4.2 (0 – 10) | 4.7 (0 – 9) | 5.6 (0 – 10)**** | 0.0187 | 0.0054 |

| Overall urologic or pelvic pain symptoms | 4.3 (0 – 10) | 5.5 (1 – 10)** | 5.1 (1 – 9) | 6.5 (2 – 10)*** | 6.2 (0 – 10)**** | <0.0001 | 0.11 |

| Overall non-urologic pain symptoms | 4.2 (0 – 10) | 3.1 (0 – 10)** | 3.2 (0 – 10)* | 3.2 (0 – 9) | 4.0 (0 – 10) | 0.045 | 0.087 |

| Most bothersome symptom (%): | |||||||

| Pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort4 | 65.6 | 74.7 | 77.1 | 78.1 | 76.7 | ||

| Urologic symptoms5 | 17.2 | 7.4 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 10.7 | 0.0487 | 0.587 |

| Other bothersome symptoms6 | 17.2 | 17.5 | 14.1 | 15.3 | 12.8 | ||

P-values for comparisons to non-flare levels:

0.05≤p<0.1;

0.01≤p<0.05;

0.001≤p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Means and percentages were calculated by generalized linear mixed models. P-values were calculated by generalized linear mixed models or conditional logistic regression, as appropriate.

Comparing all flare to non-flare values.

Assessing the linear trend in symptom severity by duration of flares.

Includes pain, pressure, or discomfort in the pubic or bladder area; in the area between: their rectum and testicles (perineum, males only) or the vaginal area (females only);or during or after sexual activity.

Includes urgency, frequency, nocturia, or sense of incomplete emptying.

Includes the following symptoms reported by participants as “other bothersome symptoms” on the flare survey: pain during or after urination, urethral pain, pain at the tip of the penis, pain after ejaculation, pain/burning in the bladder, dripping with urination, fatigue, and back pain. “Other” responses were collected on the flare survey only; they were not collected in the parent Trans-Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain study.

Comparing pelvic pain to all other symptoms.

Considering patterns of bothersome symptoms, 54.6% of participants reported pelvic pain as their most bothersome symptom at all times, 17.2% reported urologic or other symptoms as their most bothersome symptom at all times, 14.0% reported urologic or other non-pain symptoms as their most bothersome symptoms when they were not experiencing a flare but pelvic pain as their most bothersome symptom where they were experiencing a flare, and the remainder (14.2%) reported variable patterns of pelvic pain, urologic, and other symptoms (Appendix Table 4).

Appendix Table 4.

Patterns of most bothersome symptoms by flare status and duration among 64 participants with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and/or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2010-2013

| Non-Flare | Flare duration | N (%) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Minutes-long | Hours-long | One day-long | Multiple days-long | |||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pain1 | Urologic2 | Other3 | Pain1 | Urologic2 | Other3 | Pain1 | Urologic2 | Other3 | Pain1 | Urologic2 | Other3 | Pain1 | Urologic2 | Other3 | ||

| Pelvic pain at all times: | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pattern 1 | X | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | 35 (54.6) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Urologic or other symptoms at all times: | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pattern 2 | X | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | 4 (6.2) | ||||||||||

| Pattern 3 | X | X | 1 (1.6) | |||||||||||||

| Pattern 4 | X | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | 6 (9.4) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Urologic or other symptoms when participants are not experiencing a flare and pelvic pain during flares: | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pattern 5 | X | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | 5 (7.8) | ||||||||||

| Pattern 6 | X | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | X/0 | 4 (6.2) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Variable patterns of pelvic pain, and urologic and other symptoms: | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pattern 7 | X | X | X | X | 1 (1.6) | |||||||||||

| Pattern 8 | X | X | X | X | 1 (1.6) | |||||||||||

| Pattern 9 | X | X | X | X | 1 (1.6) | |||||||||||

| Pattern 10 | X | X | X | X/0 | 2 (3.1) | |||||||||||

| Pattern 11 | X | X | X | X | 1 (1.6) | |||||||||||

| Pattern 12 | X | X | X | 1 (1.6) | ||||||||||||

| Pattern 13 | X | X | X | X | 1 (1.6) | |||||||||||

| Pattern 14 | X | X | X | X | 1 (1.6) | |||||||||||

X=affirmative response; 0=blank response for participants who did not report that particular duration of flare. For instance, the first row of the table includes participants who reported pelvic pain as their most bothersome symptom when they were not experiencing a flare and during all flares that they experienced (minutes-, hours-, one day-, and multiple days-long flares, as appropriate for each participant).

Includes pain, pressure, or discomfort in the pubic or bladder area; in the area between: their rectum and testicles (perineum, males only) or the vaginal area (females only); or during or after sexual activity

Includes urgency, frequency, nocturia, and sense of incomplete emptying.

Includes symptoms reported by participants as “other bothersome symptoms”: pain during or after urination, urethral pain, pain at the tip of the penis, pain after ejaculation, pain/burning in the bladder, dripping with urination, fatigue, and back pain.

Health-care utilization, self-management strategies, and bother associated with flares of varying duration

Participants were more likely to contact or see a health-care provider during multiple days-long flares, but not during shorter flares, than when they were not experiencing a flare (Table 3). With respect to medication use, although participants were no more likely to change or increase their medication use during flares than when they were not experiencing a flare, they were more likely to change or increase their medication use with increasing duration of flares. Participants' likelihood to rest did not vary by duration of flares. They were, however, non-significantly more likely to do other activities, such as take a hot bath, during multiple days-long than shorter flares.

Table 3.

Health-care utilization, self-management strategies, and bother1 by flare status and duration among 64 participants with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and/or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2010-2013

| Non-Flare (n=64) | Flare duration | p-value2 | p-value3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Minutes-long (n=26) | Hours-long (n=24) | One day-long (n=16) | Multiple days-long (n=51) | ||||

| Health-care utilization and self-management strategies (%): | |||||||

| Contact or see a health-care provider | 15.6 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 15.2 | 33.6*** | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Medication change or increase | 17.2 | 10.2 | 9.0 | 17.6 | 22.9 | 0.48 | 0.024 |

| Rest | ----- | 52.1 | 60.2 | 73.1 | 63.3 | ----- | 0.28 |

| Other activities4 | ----- | 18.8 | 17.2 | 9.4 | 31.2 | ----- | 0.13 |

| Bother: | |||||||

| Keep you from doing usual things during flares (%): | |||||||

| None | 46.9 | 20.4 | 13.3 | 18.6 | 10.5 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Only a little | 23.4 | 32.2 | 16.8 | 12.5 | 7.8 | ||

| Some | 23.4 | 34.5 | 55.4 | 37.0 | 31.9 | ||

| A lot | 6.2 | 10.2*** | 16.6**** | 32.9**** | 51.5**** | ||

| Think about symptoms during flares (%): | |||||||

| None | 7.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | <0.0001 | 0.0013 |

| Only a little | 34.4 | 14.0 | 9.5 | 12.8 | 2.6 | ||

| Some | 32.8 | 35.3 | 45.6 | 43.6 | 23.3 | ||

| A lot | 25.0 | 52.0**** | 45.1**** | 46.1*** | 74.6**** | ||

| Bothered in general by flares (%): | |||||||

| None | ----- | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ----- | <0.0001 |

| Only a little | ----- | 13.2 | 10.6 | 17.0 | 9.8 | ||

| Some | ----- | 49.6 | 45.6 | 33.0 | 17.9 | ||

| A lot | ----- | 31.4 | 47.4 | 49.7 | 76.0 | ||

P-values for comparisons to non-flare levels:

0.05≤p<0.1;

0.01≤p<0.05;

0.001≤p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Means and percentages were calculated by generalized linear mixed models. P-values were calculated by generalized linear mixed models or conditional logistic regression, as appropriate.

Comparing all flare to non-flare values.

Assessing the linear trend in symptom severity by duration of flares.

Includes taking medications, pain pills, more medication, aloe vera/Elmiron, Tylenol/Urised, Vicodin, pain killers, Tylenol/Ibuprofen, Valium, antibiotics, numbing medications, and muscle relaxants; relaxing/resting and trying to rest; taking a bath/hot bath with/without baking soda, drinking warm water with baking soda, drinking more fluid, watching their diet, avoiding problem foods/beverages, lying down, relaxing, using a heating pad, icing the painful area, massaging the lower tip of their penis, and praying.

Finally, with respect to the bother of flares, participants reported a greater degree of disruption to their usual activities and thinking about their symptoms during flares of all duration than when they were not experiencing a flare. The degree of disruption and thinking about their symptoms increased with increasing duration of flares, as did the general bother associated with flares. However, even for minutes- and hours-long flares, most participants reported some disruption to their usual activities, and all reported thinking about their symptoms and being bothered by their symptoms to some degree.

Independent influence of flare symptoms and duration on health-care utilization and bother

Considering the influence of both symptoms and duration of flares on health-care utilization and self-management strategies, only duration was independently associated with contacting a health-care provider, and only overall non-urologic pain symptoms were associated with rest (Table 4). With respect to bother, pelvic pain, overall urologic and pelvic pain symptoms, and duration were independently associated with disruption to participants' usual activities during flares and general flare-related bother, whereas only pelvic pain and overall urologic and pelvic pain symptoms were independently associated with symptom-related thought during flares.

Table 4.

Influence of flare symptoms and duration on health-care utilization and bother1 among 64 participants with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and/or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2010-2013

| Typical symptom severity (on a scale of 0-10): | Duration | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort | Urinary urgency | Frequency | Overall urologic or pelvic pain symptoms | Overall non-urologic pain symptoms | (level, minutes to days) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted2 | Unadjusted | Adjusted2 | Unadjusted | Adjusted2 | Unadjusted | Adjusted2 | Unadjusted | Adjusted2 | Unadjusted | Adjusted2 | |

| Health-care utilization and self-management strategies (%): | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Contact or see a health-care provider | *** | * | ** | *** | * | * | **** | *** | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Medication change or increase | * | * | ** | * | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Rest | ** | ** | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bother (%): | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Keep you from doing usual things during flares3 | **** | **** | *** | *** | **** | **** | **** | *** | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Think about symptoms during flares3 | **** | ** | *** | *** | **** | **** | *** | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bothered in general by flares3 | **** | *** | ** | *** | **** | **** | * | **** | **** | |||

Significance of positive associations:

0.05≤p<0.1;

0.01≤p<0.05;

0.001≤p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Associations were calculated by generalized linear mixed models.

Mutually adjusted for duration and all symptoms listed in the table with the following exceptions: a) none of the models were adjusted for overall urologic or pelvic pain symptoms; b) urgency and frequency models were not mutually adjusted because of the high correlation between these two variables (r=0.82); and c) models for overall urologic or pelvic pain symptoms were adjusted for overall non-urologic pain symptoms and duration only.

Comparing flares with a lot of bother to those with none, a little, or some bother.

Given these findings for both symptoms and duration, we next performed regression classification tree analysis to explore additional possible patterns of symptoms and duration that might be associated with flare-related bother (defined as “a lot” of general flare-related bother). In these analyses, both symptoms and duration were important, although pelvic pain appeared to be the most important factor (mean variable importance factor=4.70 for pelvic pain, 4.14 for either urgency or frequency (combined because of their high degree of correlation, r=0.82), and 4.05 for duration). While no one single classification tree predominated (see Appendix Table 5 for the most common trees), common variable cut-off points were observed across a large proportion of trees. These cut-off points for “a lot” of bother were >5.5 (out of 10) for pelvic pain (45.6% of trees), >6.5 for urgency or frequency (40.0%), and multiple days-long for duration (46.1%).

Appendix Table 5.

Common classification trees of flare-related bother1 derived from 64 participants with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and/or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2010-2013.

| First partition | Second partition (of the first left node) | Second partition (of the first right node) | Percentage of 1,000 trees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Variable | Cut-off point | Variable | Cut-off point | Variable | Cut-off point | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Left node | Right node | Left node | Right node | Left node | Right node | ||||

| Urgency or frequency | ≤6.5 | >6.5 | Duration | ≤One day-long | Multiple days-long | ----- | ----- | ----- | 17.3 |

| Urgency or frequency | ≤6.5 | >6.5 | Pelvic pain | ≤5.5 | >5.5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | 7.5 |

| Pelvic pain | ≤5.5 | >5.5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 13.2 |

| Pelvic pain | ≤5.5 | >5.5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | Duration | ≤Hours-long | ≥One day-long | 3.2 |

| Pelvic pain | ≤6.5 | >6.5 | Non-urologic pain symptoms | ≥1.5 | <1.5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1.6 |

| Pelvic pain | ≤5.5 | >5.5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | Duration | Minutes-long | ≥Hours-long | 1.6 |

| Pelvic pain | ≤5.5 | >5.5 | Duration | ≤One day-long | Multiple days-long | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1.6 |

| Duration | ≤One-day long | Multiple days-long | Urgency or frequency | ≤7.5 | >7.5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | 9.3 |

| Duration | Minutes-long | ≥Hours-long | ----- | ----- | ----- | Pelvic pain | ≤5.5 | >5.5 | 2.9 |

| Duration | ≤One-day long | Multiple-days long | Urgency or frequency | ≤6.5 | >6.5 | ----- | ----- | ----- | 2.5 |

| Duration | ≤Hours-long | ≥One day-long | ----- | ----- | ----- | Pelvic pain | ≤5.5 | >5.5 | 2.3 |

Defined as “a lot” of general flare-related bother. Each tree can be interpreted as follows: the first partition indicates where the data are first split into two nodes and the second partition indicates where one of these nodes (either the left or right node) is split into two further nodes. Nodes on the right contain mostly flares associated with “a lot” of bother and nodes on the left contain primarily flares associated with not a lot of bother. Each of the partitions is determined by maximizing the association between flare attributes (i.e., intensity of pelvic pain, intensity of urgency or frequency, or duration) and flare-related bother. As an example, we describe the most common tree (first row of the table). The first optimal partition of this tree occurs at values of urgency or frequency >6.5. This means that flares with values of urgency or frequency >6.5 have a higher probability of contributing to a lot of bother than those with values of urgency or frequency ≤6.5. The second and final optimal partition of this tree occurs among flares with values of urgency or frequency ≤6.5 (first left node). Of these flares, those that last for multiple days have a higher probability of contributing to a lot of bother than those that last for one day or less. Thus, considering the tree as a whole, flares with values of urgency or frequency >6.5 and those with values of urgency or frequency ≤6.5 that last for multiple days have a higher probability of contributing to a lot of bother, whereas those with values of urgency or frequency ≤6.5 that last for one day or less have a lower probability of contributing to a lot of bother. This pattern occurred 173 times (17.3%) out of the 1,000 times that the analyses were run with re-sampling.

Discussion

In this exploratory study of UCPPS flares, we identified a wide spectrum of flares in terms of their duration (seconds to months), frequency (several times/day to once/year or less), intensity (0-10 on a scale of 0-10), and type of symptoms (e.g., pelvic pain versus urologic symptoms). This wide spectrum was observed even within the same participant. For instance, while some participants reported exclusively one duration of flare (e.g., only multiple days-long flares), others reported variable durations of flares (e.g., minutes- to days-long flares) with varying types of bothersome symptoms, although days-long flares and pelvic pain tended to be the most common duration and bothersome symptom reported, respectively. We also found that flares of any duration were associated with greater pelvic pain and urologic symptoms, disruption to participants' activities and thoughts, and general bother, with increasing severity of symptoms and bother as the duration of flares increased. These associations were evident even though multiple days-long flares were also associated with greater self-reported health-care utilization and medication use. Finally, in addition to duration, symptoms, particularly pelvic pain, were significant determinants of flare-related bother.

Although days-long UCPPS flares have long been recognized in the medical community, very few studies have described these flares [7] or assessed their impact. In our survey, we found that multiple days-long flares were associated with the highest levels of urologic and pelvic pain symptoms, ranging from a mean of 5.6 points for frequency (on a scale of 0-10) to 6.9 for pelvic pain. These flares were also associated with considerable health-care utilization, disruption to participants' usual activities, symptom-related thought, and general bother. Approximately one third of participants reported contacting or seeing a health-care provider during multiple days-long flares, approximately one quarter reported changing or increasing their medication, over one half were kept from doing their usual activities, and three quarters thought about their symptoms and were bothered by their symptoms “a lot”. Therefore, given these clear negative consequences of multiple days-long flares, greater emphasis should be placed on research to prevent and treat these flares.

While the occurrence of multiple days-long flares is well recognized in the medical community, at least anecdotally, the occurrence and impact of shorter flares are less well understood. We found that shorter flares – i.e., minutes- and hours-long flares – were common and were associated with significantly worse pelvic pain (mean of 5.2 for minutes-long to 6.0 for hours-long flares) and urgency (mean of 5.2 for minutes-long flares), although these symptoms were frequently not as severe as for flares of longer duration. However, in contrast to longer flares, we found that shorter flares were not associated with greater health-care utilization, possibly because they resolved before participants had the opportunity or reached a threshold to contact their health-care provider. This observation may also explain the lack of references to these shorter flares in the medical literature. Finally, although shorter flares were not associated with a greater degree of health-care utilization, they were associated with greater disruption to participants' usual activities, symptom-related thought, and general bother. For instance, almost half reported at least “some” degree of disruption to their usual activities, almost 90% reported some symptom-related thought, and 80% reported some bother associated with minutes-long flares. Therefore, while not as impactful as longer flares, shorter flares, particularly those that are painful, also appear to influence patients' lives negatively and thus warrant further research attention.

In contrast to our findings for urologic and pelvic pain symptoms, non-urologic pain symptoms (e.g., back pain) appeared to be similar during flares than when participants were not experiencing a flare. This finding was counter to our expectation based on anecdotal reports from patients of widespread worsening of pain during flares. However, it is possible that participants focus more on their worsening urologic and pelvic pain symptoms than on their non-urologic pain symptoms during flares, leading them to rate their non-urologic pain symptoms lower in the context of a flare (i.e., an adaptation-level effect of other pain [13, 14]). As another possibility, body pain may widen during flares (i.e., the number of body areas with pain may increase) but the severity of pain in these areas may be no worse than when they are not experiencing a flare, at least for the majority of participants.

Finally, one further unexpected observation warrants discussion. When asked about minutes-long flares, one male participant reported six flares/day for which his most bothersome symptom was a “slight burning sensation” with urination. These flares appear to correspond to the characteristic UCPPS symptom of pain or burning with urination rather than to an exacerbation of UCPPS symptoms, which is a more typical, anecdotal definition of flares. Therefore, in future studies, it may be useful to clarify and separate these two definitions so that the mechanisms of pain with urination can be explored separately from the mechanisms and etiology of symptom exacerbations, particularly those of unknown etiology.

In summary, in what we believe is the first study to describe the full spectrum of UCPPS symptom flares, we identified a wide spectrum of symptom exacerbations in terms of duration, frequency, symptoms, and symptom severity. We also found that flares of all duration were common, and were associated with greater severity of symptoms, disruption to participants' activities and thoughts, and bother. This was particularly true for longer flares but was also true for shorter flares. Finally, independent of their duration, painful flares were also bothersome. Therefore, we believe that future research should focus on ways in which to prevent and treat flares, particularly those that are longer and/or painful, given their common occurrence and high degree of bother.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra H. Berry, and Drs. Bruce D. Naliboff and Erika A. Waters for helpful discussion related to this manuscript; our MAPP research coordinators, Rebecca Bristol and Vivien Gardner, for implementing the study; members of the MAPP Data Coordinating Center for managing the parent study data; the physicians and nurses within the Division of Urological Surgery for referring their patients; and, most importantly, the participants for their participation.

Some of the information contained in this manuscript was presented as abstracts at the Annual American Urological Association meetings in Atlanta, GA (2012) and San Diego, CA (2013). This study was funded by the MAPP (Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain) research grant, NIH DK082315. Dr. Sutcliffe was also supported by the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation.

Appendix Table 1

Eligibility criteria for the Trans-Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Epidemiology and Phenotyping Study

| Inclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

| Deferral criteria |

|

|

|

Appendix Table 2

Flare survey administered to all participants at the Washington University School of Medicine and University of Alabama at Birmingham sites of the Multidisciplinary Approaches to the study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Research Network

-

Have you ever had a flare of your urologic or pelvic pain symptoms that lasted[less than an hour*]? By flare we mean, symptoms that are much worse than usual?

❑1 Yes ❑0 No (if No, skip to question 2.)

If YES, please answer the following questions about your flares that last [LESS THAN AN HOUR]. We will ask you about your longer flares in the next set of questions.

On average, how many minutes do your flares usually last if they last [less than an hour]? ___________ minutes

How often do you usually have flares that last [less than an hour]? (Please use any time frame that applies to you, e.g., times per day, per week, per month, etc.) ___________

-

How would you rate your symptoms during a typical flare that lasts [less than an hour]?

No symptoms Worst symptoms 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Pain, pressure and discomfort associated with your bladder/prostate and/or pelvic region ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑

Urgency (urge or pressure to urinate) ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑

Frequency of urination ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑

Overall urologic or pelvic pain symptoms ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑

Overall pain symptoms that were not urologic or pelvic pain symptoms (e.g., back pain, headache, etc) ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑ ❑

-

During a typical flare that lasts [less than an hour], what is your single most bothersome symptom? (Please select only ONE answer.)

❑1 Pain, pressure, discomfort in your pubic or bladder area

❑2 Pain, pressure, discomfort in the area between: your rectum and testicles (perineum) [MALES only], - OR-the vaginal area [FEMALES only]

❑3 Pain/discomfort during or after sexual activity

❑4 Strong need to urinate with little or no warning

❑5 Frequent urination during the day

❑6 Frequent urination at night

❑7 Sense of not emptying your bladder completely

❑8 Other: _______________________________________________________________________ -

During a typical flare that lasts [less than an hour], which of the following activities do you usually do? (Please check all that apply.)

Contact a health-care provider (physician, nurse, physical therapist, or other provider) by telephone or e-mail; see a health-care provider in his/her office; or make a trip to an emergency room or urgent care center ❑

Have a medication changed (new medication or different dose) ❑

Rest ❑

Other: ____________________________________________________________________________

-

During a typical flare that lasts [less than an hour], how much do your symptoms keep you from doing the kinds of things you would usually do?

None Only a little Some A lot ❑0 ❑1 ❑2 ❑3 -

During a typical flare that lasts [less than an hour], how much do you think about your symptoms?

None Only a little Some A lot ❑0 ❑1 ❑2 ❑3 -

How much do your symptom flares that last [less than an hour] bother you?

None Only a little Some A lot ❑0 ❑1 ❑2 ❑3 * This form was repeated for flares that last “more than an hour but less than a day” and for flares that last “more than a day”.

Appendix Table 3

Distribution of duration and frequency of symptom flares by broad flare duration category and sex among 72 participants with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Washington University School of Medicine and the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2010-13.

| Minutes-long flares | Hours-long flares | One day-long flares | Multiple days-long flares | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

|

| ||||||||

| Duration | (in minutes) | (in hours) | (in hours) | (in days) | ||||

| N | 13 | 14 | 21 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 39 | 17 |

| Maximum | 60.0 | 60.0 | 8.0 | 6.5 | 17.0 | 23.0 | 90.0 | 60.0 |

| 75th percentile | 37.5 | 35.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 22.5 | 10.0 |

| Median | 30.0 | 30.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 3.5 | 7.0 |

| Mean | 27.5 | 25.6 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 7.4 | 10.9 |

| 25th percentile | 15.0 | 10.0 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 2.5 | 4.5 |

| Minimum | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 2.51 |

|

| ||||||||

| Frequency | (per week) | (per week) | (per week) | (per month) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| N | 12 | 13 | 20 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 34 | 16 |

| Maximum | 10.0 | 42.0 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 8.7 | 17.4 |

| 75th percentile | 2.3 | 7.0 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 |

| Median | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| Mean | 2.1 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| 25th percentile | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Minimum | 0.1 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.083 |

p-value for comparison of the full distribution between women and men = 0.020.

p-value for comparison of the full distribution between women and men = 0.098.

p-value for comparison of the full distribution between women and men = 0.027.

References

- 1.Whitmore KE. Self-care regimens for patients with interstitial cystitis. Urol Clin North Am. 1994;21(1):121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metts JF. Interstitial cystitis: urgency and frequency syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(7):1199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanno PM, et al. American Urological Association (AUA) guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. American Urological Association. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Propert KJ, et al. A prospective study of interstitial cystitis: results of longitudinal followup of the interstitial cystitis data base cohort. The Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study Group. J Urol. 2000;163(5):1434–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander RB, Trissel D. Chronic prostatitis: results of an Internet survey. Urology. 1996;48(4):568–74. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Propert KJ, et al. A prospective study of symptoms and quality of life in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort study. J Urol. 2006;175(2):619–23. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00233-8. discussion 623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutcliffe S, et al. Changes in symptoms during urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome symptom flares: findings from one site of the MAPP Research Network. Neurourol Urodyn. doi: 10.1002/nau.22534. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong HJ. Effects of a short course of oral prednisolone in patients with bladder pain syndrome with fluctuating, worsening pain despite low-dose triple therapy. Int Neurourol J. 2012;16(4):175–180. doi: 10.5213/inj.2012.16.4.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Interstitial Cystitis Association Web survey. How do you define an IC flare? [Accessed February 17, 2011];2009 Available at: http://www.ichelp.org/Page.aspx?pid=525.

- 10.Clemens JQ, et al. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 2009;74(5):983–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078. quiz 987 e1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster HE, Jr, et al. Effect of amitriptyline on symptoms in treatment naive patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2010;183(5):1853–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breiman L, et al. Classification and Regression Trees. New York: Wadsworth, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naliboff BD, et al. Signal detection and threshold measures for chronic back pain patients, chronic illness patients, and cohort controls to radiant heat stimuli. J Abnorm Psychol. 1981;90(3):271–4. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MJ, et al. Signal detection and threshold measures to loud tones and radiant heat in chronic low back pain patients and cohort controls. Pain. 1983;16(3):245–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DA, Schilling S. Advances in the assessment of fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35(2):339–57. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]