Abstract

Objective

To determine whether there are differences in fracture patterns and femur fracture treatment choices in obese vs. non-obese pediatric trauma patients.

Design

Prognostic study, retrospective chart review.

Setting

Two level I pediatric trauma centers.

Patients

The trauma registries of two pediatric hospitals were queried for patients with lower extremity long bone fractures resulting from blunt trauma. 2858 alerts were examined and 397 patients had lower extremity fractures. 331 patients with a total of 394 femur or tibia fractures met inclusion criteria, and 70 patients (21%) were obese.

Main Outcome Measurements

Weight for age >95th percentile was defined as obese. Radiographs were reviewed and fractures were classified according the OTA/AO pediatric fracture classification system. Fracture patterns (OTA subsegment), severity, and choice of intervention for femur fractures were primary outcomes.

Results

Overall, obese patients were twice as likely (RR=2.20, 95% CI 1.25–3.89) to have fractures involving the physis. Physeal fracture risk was greater for femur fractures (RR=3.25, 95% CI 1.35–7.78) than tibia fractures (RR=1.58, 95% CI 0.76–3.26). Severity did not differ between groups. Obese patients with femur fractures were more likely to be treated with locked nails.

Conclusion

Obese pediatric trauma patients are more likely to sustain fractures involving the physis than non-obese patients. This could be related to intrinsic changes to the physis related to obesity, or altered biomechanical forces. This is consistent with the observed relationships between obesity and other conditions affecting the physis including Blount’s and slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Keywords: obesity, physeal fracture, pediatric

Introduction

Obesity is epidemic in the United States, and children are not being left behind. The South has a particularly alarming rate of obesity in childhood and adolescence. Currently, the home states of the participating centers rank 46th and 47th in childhood obesity (the 4th and 5th highest rates of obesity in the U.S.).1 Certainly, the most serious implications of the obesity epidemic are to the long-term health of the patients due to co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, and diabetes.2 Obesity may also lead to musculoskeletal complications, such as slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) and tibia vara.3 Furthermore, obese children may be at increased risk of fracture.4, 5 The causes for these differences are not clear, and may be multi-factorial.6–8 Despite investigation into whether obese children are at increased risk of fracture, few studies have examined whether the patterns of fracture differ between obese and non-obese children.8

In a previous study, we evaluated associated injury patterns, ISS and mortality in obese and non-obese trauma patients who sustained lower extremity long-bone fractures.9 In the present study, we further examined the relationships between lower extremity fracture and obesity in trauma patients, emphasizing fracture patterns and treatment. We hypothesized that patients with obesity would have altered fracture patterns, and receive differing treatments. A retrospective review of radiographs and charts was performed utilizing the trauma registries of two free standing level I pediatric trauma centers.

Patients and Methods

Patients

IRB approval with waiver of informed consent was obtained from both institutions. The trauma registries were queried from 2004 to 2010 for patients 2–14 years of age who had been admitted following high-energy trauma alerts (based on mechanistic or physiologic criteria) and had a diagnosis of lower extremity long bone fracture. A total of 2,858 trauma alerts were reviewed and 397 patients with femur and/or tibia fractures were identified. Typical mechanisms included motor vehicle crash, fall from height, and pedestrian struck by vehicle. Exclusion criteria were patients with mechanism penetrating trauma, isolated fibula fracture, traumatic amputation, pathologic fracture, and medical record did not provide weight information and available radiographic images. There were 331 patients with femur or tibia fracture that met inclusion criteria.

Data Collection

Weight, height (when available), age, and fracture location and method of treatment were recorded. Information regarding associated head, chest abdomen and pelvic trauma and inpatient outcomes regarding intensive care unit (ICU) stay and mortality was recorded and has been reported in a separate publication.9 For this investigation, we performed radiographic review of the fractures and classified them according to the OTA/AO pediatric long bone fracture classification system.10–12 It should be noted that in this system, the sub-segment designation “Epiphysis” includes all Salter-Harris physeal fracture types. Additionally a severity modifier is used to distinguish between simple fracture patterns (.1 severity code) and more severe/unstable fracture patterns involving a wedge fragment or segmental comminution (.2 severity code). The fractures were classified by a medical student after training by a pediatric orthopaedist. A subset of 56 radiographs was classified by the senior author blinded to patient characteristics and to the student’s assessment and interobserver agreement was evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were classified as obese or non-obese based on weight for age (WFA) percentile.13 The Centers for Disease Control defines children with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 85th percentile as overweight and children with BMI greater than or equal to 95th percentile as obese.14 WFA ≥ 95th percentile was used rather than body mass index as has been done in other published studies due to inconsistent recording of height in the medical record.15–17 In addition, a secondary analysis used BMI ≥ 85th percentile to classify patients as overweight for those patients with height recorded. The study populations for the two institutions were compared and found not to be statistically different with respect to age, race, and WFA percentile. Given that some patients had multiple fractures, the unit of observation for this analysis was at the level of injury.

Patient level characteristics of obese and non-obese patient groups were compared using Chi-square tests or, when appropriate, Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and two-sided Student t-tests for continuous variables. Fisher’s exact tests were used to examine significant differences in fracture location and long bone segment, i.e., proximal, distal, and diaphyseal, and for sub-segment (epiphysis and metaphysis) stratified by long bone segment. P-values less than or equal to 0.05 alpha were considered statistically significant.

Risk of epiphyseal fracture was calculated overall and restricted to proximal-distal segments for each long bone type and femur-tibia combined. To account for patients who had multiple fractures, i.e., clustering of events, crude and adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated utilizing generalized estimating equations (GEE) assuming a Poisson distribution and a log link function.18 RRs were adjusted for patient age, height, and injury severity score (ISS). We also examined risk of epiphyseal fracture with respect to BMI. Because of a small number of patients who were obese using BMI ≥ 95th percentile, we evaluated overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile). Finally, femur fracture treatments were compared between groups using Chi-square tests that accounted for clustering of events to test for statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic and injury characteristics did not differ from those reported in the previous publication.9 Overall, 18.4% of patients (70/331) were classified as obese (i.e., WFA ≥ 95%). Mean age was slightly older for obese children (9.9±3.7 years vs, 8.7 ±3.9, P=.02.). There were no differences in racial composition or gender. Of those with height data, 70 patients (21%) were >90th percentile height for age. Height data was missing for 51 patients (15.4%). For those patients with recorded height, 121(43%) patients had BMI≥85th percentile (overweight) but only four (1%) had BMI≥95th percentile (obese). The rate of obesity observed with BMI was not felt to be an accurate representation of our patient population, and WFA9003E;95th percentile was used to define obesity for remaining analyses.

A total of 266 femur fractures had radiographs available for fracture classification. Of these, 82.7 % of fractures were diaphyseal, 5.6% were proximal, and 11.7% were distal. A total of 128 tibia fractures had radiographs available, of which 52% were diaphyseal, 10% were proximal, and 38% were distal. There were no statistically significant differences between groups with respect to distribution of fractures in the proximal, middle, and distal segments of the femur and tibia.

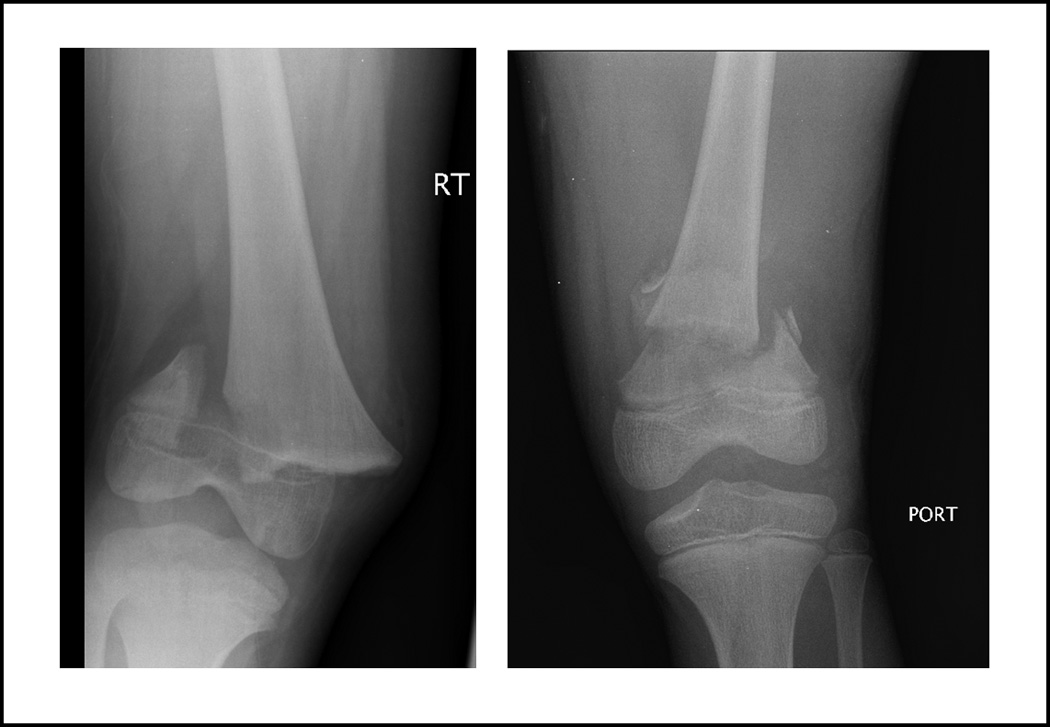

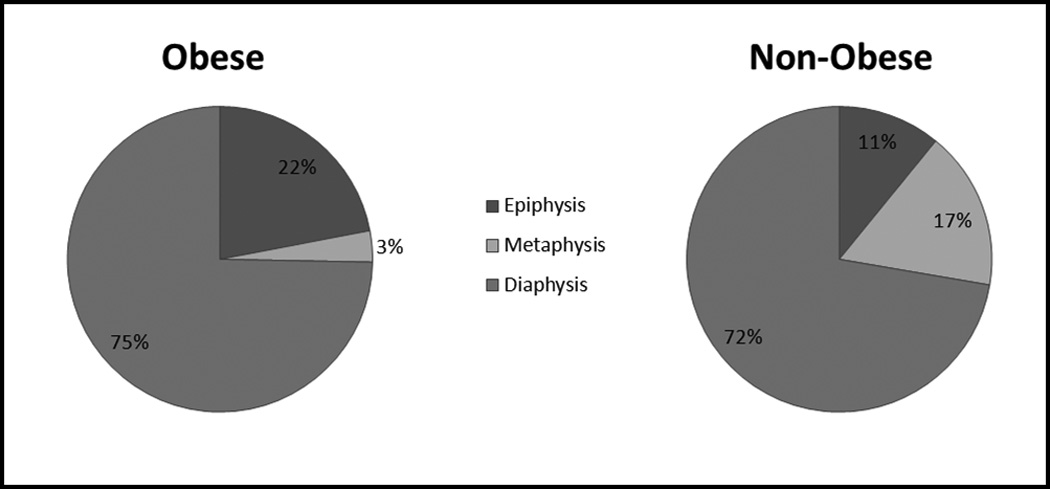

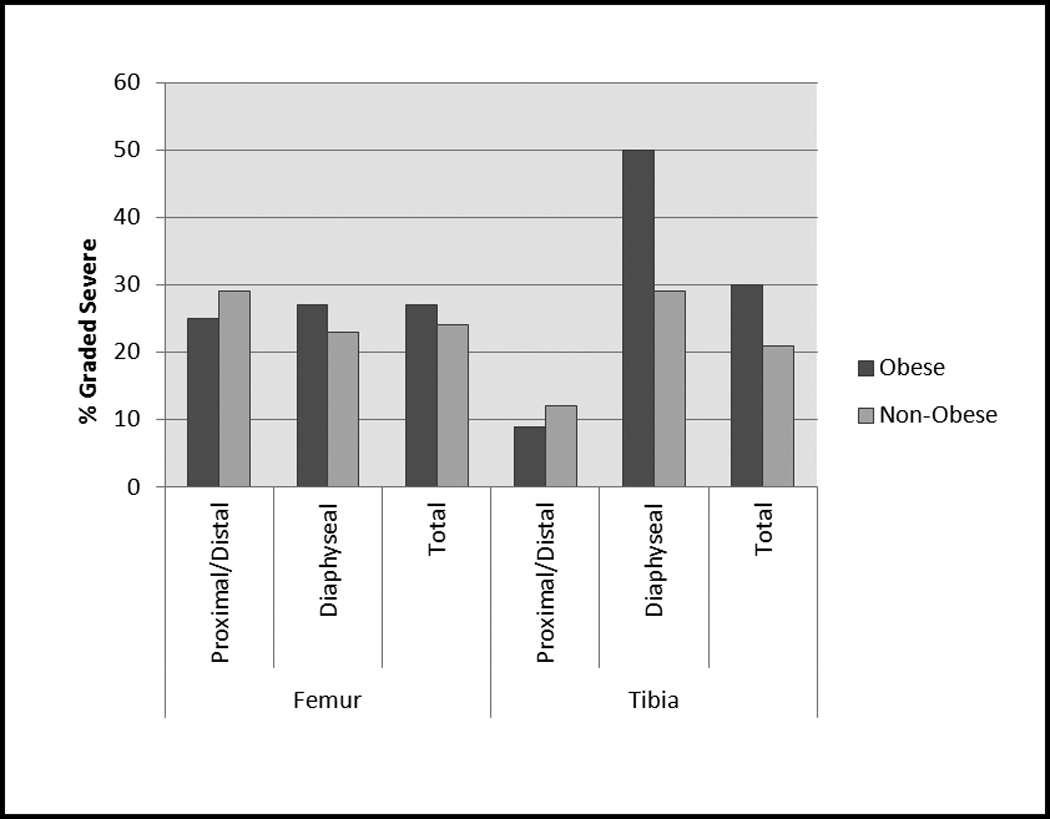

When segments were classified as epiphyseal or metaphyseal, obese patients were more likely to fracture the epiphysis compared to non-obese patients (femur: 91.7% vs. 44.1%, P = .004; tibia: 81.8% vs. 36%, P <=.007) (see case example Figure 1). Obese patients had a higher proportion of epiphyseal fractures at all locations, and the differences reached statistical significance for the proximal femur (Table 1, Figure 2). Comparison of attending and medical student classification for subsegment (metaphyseal, epiphyseal, diaphyseal) yielded a simple kappa value of 0.87 (near perfect agreement). Table 2 displays the distribution of distal femur and distal tibia physeal fractures in each group organized by Salter-Harris classification. There were only two proximal femur physeal fractures, one Salter Harris I fracture and one ligamentum teres avulsion, both in obese patients. There was one proximal tibia physeal fracture of the tibial eminence in both groups. Due to the limited number of fractures involving the epiphysis, no statistics were performed comparing fracture morphology between groups. Finally, comparison of fracture severity between obese and non-obese groups revealed no significant difference in the overall proportion of severe fractures (classified as severity code .2 by the OTA/AO pediatric long bone classification system10–12 (Simple kappa = 0.55, slight agreement)). There was a trend towards more severe tibia fractures in the obesity group, 50% vs. 29%, but it did not reach statistical significance (P =0.17) (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Case Example.

Two patients who sustained distal femur fractures in motor vehicle collisions. The obese patient (left) sustained a SH II physeal fracture, while the non-obese patient (right) sustained a metaphyseal fracture.

Table 1.

Comparison of fracture location by long bone segment (proximal, distal, diaphyseal) and sub-segment (epiphysis vs. metaphysis).

| N (%) | Obese (WFA>95th) |

Non-Obese | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femur, N | 68 | 198 | |

| Long bone segment | |||

| Proximal | 3 (4.4) | 12 (6.1) | 0.8020 |

| Distal | 9 (13.2) | 22 (11.1) | |

| Diaphyseal | 56 (82.4) | 164 (82.8) | |

| Proximal and distal sub-segments | |||

| Epiphysis | 11 (91.7) | 15 (44.1) | 0.0043 |

| Metaphysis | 1 (8.33) | 19 (55.9) | |

| Proximal sub-segment | |||

| Epiphysis | 2 (66.7) | 0 (-) | 0.0286* |

| Metaphysis | 1 (33.3) | 12 (100) | |

| Distal sub-segment | |||

| Epiphysis | 9 (100) | 15 (68.2) | 0.0766* |

| Metaphysis | 0 (-) | 7 (31.8) | |

| Tibia, N | 23 | 105 | |

| Long bone segment | |||

| Proximal | 1 (4.4) | 12 (11.4) | 0.5492 |

| Distal | 10 (43.5) | 38 (36.2) | |

| Diaphyseal | 12 (52.2) | 55 (52.4) | |

| Proximal-distal sub-segment | |||

| Epiphysis | 9 (81.8) | 18 (36.0) | 0.0077* |

| Metaphysis | 2 (18.2) | 32 (64.0) | |

| Proximal sub-segment | |||

| Epiphysis | 1 (100) | 1 (8.3) | 0.1538 |

| Metaphysis | 0 (-) | 11 (91.7) | |

| Distal sub-segment | |||

| Epiphysis | 8 (80.0) | 17 (44.7) | .0753* |

| Metaphysis | 2 (20.0) | 21 (55.3) |

Fisher’s exact test

Figure 2. Fracture location.

Pie charts show proportion of diaphyseal, metaphyseal and physeal fractures (tibia and femur combined) in the obese and non-obese weight groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of physeal fractures between groups

| N (%) | Obese | Non-Obese |

|---|---|---|

| Femur - distal | 9 | 15 |

| Salter Harris I | 1 (11.1) | 2 (13.3) |

| Salter Harris II | 6 (66.7) | 11 (73.3) |

| Salter Harris III | 1 (11.1) | 0 (-) |

| Salter Harris IV | 1 (11.1) | 2 (13.3) |

| Tibia - distal | 8 | 17 |

| Salter Harris I | 0 (-) | 2 (11.8) |

| Salter Harris II | 3 (37.5) | 6 (35.3) |

| Salter Harris III | 3 (37.5) | 9 (52.9) |

| Salter Harris IV | 2 (25.0) | 0 (-) |

Figure 3. Fracture severity.

Percent of fractures from indicated segment classified as ‘severe’ (Severity code .2). No statistically significant differences were seen between the obese and non-obese groups.

Risk ratios were calculated to estimate the increased risk of epiphyseal fracture in obesity (Table 3). Because of the statistically significant difference between the groups for age (1.2 years) and ISS (4.7), risk ratios were adjusted for age and ISS. An adjustment for height >90th percentile was also included, as this characteristic showed a trend towards being associated with physeal fracture. When all fractures of the tibia or femur were considered, obese patients were almost twice as likely to sustain an epiphyseal fracture as non-obese patients, even when statistical adjustment for age, height, and ISS was made (adjusted RR 2.20, CI 1.25–3.89). If diaphyseal fractures are excluded (i.e. examining just those with the possibility of involving the physis) obese patients had an adjusted RR of 2.03 (95% CI 1.41–2.94) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Crude and Adjusted Risk Ratios and 95% CIs for obesity and physeal fracture by long bone type

| RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) |

P-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long bone type | |||

| Femur | 2.52 (1.26–5.05) | 3.25 (1.35–7.78) | 0.0082 |

| Tibia | 2.15 (1.10–4.20) | 1.58 (0.76–3.26) | 0.2179 |

| Combined | 2.16 (1.30–3.59) | 2.20 (1.25–3.89) | 0.0065 |

| Proximal-distal | |||

| Femur | 2.08 (1.35–3.20) | 2.17 (1.30–3.60) | 0.0107 |

| Tibia | 2.15 (1.36–3.39) | 1.38 (0.89–2.14) | 0.1007 |

| Combined | 2.16 (1.58–2.95) | 2.03 (1.41–2.94) | 0.0002 |

Physeal includes all epiphyseal fractures with the exception of ligament avulsions and tibial spine fractures

Adjusted model includes Height for age 90% (yes/no), age, and ISS

We previously reported that the obese patients in this cohort had a higher rate of operative fracture treatment, particularly for the femur.9 In the present study, we chose to further investigate treatment modalities chosen for femur fractures. A statistically significantly greater number of fractures among obese patients were treated with locked nails (26% vs. 13%, p = 0.0140). Trends were observed regarding other treatment options, but did not reach statistical significance: a smaller proportion of obese patients were treated with casting or flexible intramedullary nails and a larger proportion were treated with external fixation (Supplemental Table 1).

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated significant differences in fracture patterns and treatment between obese and non-obese trauma patients who present with femur or tibia fracture. Obese patients are more likely to sustain physeal fractures. When operative intervention for femur fractures was chosen, obese patients were more likely to undergo locked intramedullary nailing.

The strengths of the present study include a comparatively high volume of patients which allows for more robust statistical analysis, including appropriate statistical adjustments for age and height. More specifically, the high rate of obesity provides a larger number of obese patients than in previous studies. In addition, the multivariate analysis was carried out at the injury level and accounted for clustering of multiple events among patients.

The limitations include those common to retrospective chart reviews including lack of information regarding co-morbidities, and inconsistent or possibly inaccurate documentation of height and weight. The use of WFA instead of body mass index could overestimate obesity. For example a child who was very tall may have weight that is height appropriate, but high compared to age. This choice was made due to incomplete reporting of patient height. The use of WFA has been previously reported,15–17 and in the present study results in an obesity rate (18.4%) that is consistent with the reported population rates for the region. The region from which patients in the present study are drawn has a childhood obesity rate of 19.2%, compared with 16.4% nationwide.19

To further address this, a secondary analysis of patients with height information was performed. The use of BMI in this study population appeared to be less suitable with 15% of patients lacking height data (including 7 of 26 patients with femur physeal fractures), and only 1% of the patients found to be obese by BMI. Another study examining BMI using measurements from clinic showed an overall rate of obesity of 19% in our scoliosis patients.20 This suggests that exclusion of patients without recorded height may skew our data and that use of solely BMI percentile criteria with the available data likely underestimates obesity. Nevertheless, we repeated the analysis of relative risk of physeal fracture in overweight children (BMI≥85th percentile) and found similar trends towards increased rate of physeal fracture that was significant for femur and tibia fractures combined (Adjusted RR=1.82, CI 1.02–3.26, supplemental Table 2). Future studies should include prospective measurement of height and weight. Additional information such as estimation of body composition and skeletal maturity assessment would also be of value.

Additionally, detailed injury data was not available to fully address mechanism of injury or directly evaluate the forces resulting in fracture. Finally, the radiographs were read by a medical student after training, raising a potential concern regarding correct classification. However, a subset of the radiographs was also classified by an experienced pediatric orthopaedic surgeon and interobrserver agreement was found to be equal or superior to reported agreement between pediatric orthopaedic surgeons11,12 for the comparatively simple step of assigning fractures to sub segments of diaphyseal, metaphyseal or epiphyseal, which forms the main thrust of this study.

The increased propensity for physeal fracture in obese patients has not been previously reported to our knowledge. It is not known whether the same would be true for low energy injuries, but the finding is congruous with the concept that obesity is linked with an increased susceptibility to physeal alteration such as Blount’s disease or SCFE.3, 21–23 The present study cannot address potential causes for the increased rate of physeal fracture in obesity, which is likely to be multi-factorial including physiologic and mechanical influences. With respect to physiology, adipose tissue is being increasingly recognized as metabolically active. Specifically with respect to Blounts, patients have been noted to have advanced skeletal age24 consistent with the finding that obese children in general have advanced skeletal age. Since the mechanical forces applied to the upper extremities which are used to evaluate skeletal age would be less affected by obesity, this suggests a metabolic effect on the physis, Fat may have endocrine effects on bone through obesity related pathways such as leptin and adiponectin.25–28 Vitamin D levels have also been shown to be diminished in obesity, and this could contribute to altered skeletal health.29 Obese children tend to have lower bone mass,30 and have higher rates of self-reported fractures.31 Also, girls with low-energy forearm fractures tend to be heavier and have decreased bone mineral density32 and decreased cross-sectional area of the radius33 compared to non-fractured controls.

Mechanical effects could also contribute to the alteration of fracture pattern in obese children. Obesity may place chronic excessive stress on the bones and cartilage as well as the supporting ligaments and tendons .34 Acutely, patients who were injured by sudden deceleration such as MVC or fall would experience increased force in proportion to mass (Force = Mass × Acceleration). Further, increased size may alter the relationship of the patient to the compartment and restraints in the case of MVC or other modes of transportation. Detailed information regarding mechanism of injury beyond general types was not available to further evaluate the forces sustained. Finally, in the companion paper to this manuscript examining inpatient mortality and associated injuries the obese patients were noted to present with higher injury severity score,9 suggesting they are either more likely to sustain severe trauma or survive severe trauma until hospital presentation. It is difficult to conceptualize how these possible different physical effects would alter the propensity for physeal vs. metaphyseal fracture, however.

Obesity appears to influence surgeon choices for femur fracture fixation. The obese group had a lower proportion of femur fractures treated with casting and a higher proportion treated with external fixation or locked nail, although statistical significance was noted only for locked nails. This may be in part due to reports of increased risk of malunion and other complications following flexible nailing in obese patients,15 and due to increased difficulty of managing obese patients in spica casts.35, 36 Age is also an important consideration in femur fracture management, but the higher rate of operation in obese children persisted after statistical adjustment for the 1.2 year age difference.

In conclusion, the present study documents a previously unreported finding of increased rate of physeal fracture in obese pediatric trauma patients. This suggests a need for further study into the mechanisms by which skeletal and adipose tissue interact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

source of funding: Shawn R. Gilbert has grants from Department of Defense (OR090206), National Institutes of Health (R03EB017344), and the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America. Ian Backstrom was supported by an NIH training grant through the University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for Clinical and Translational Science: grant # 5UL1 RR025777. Paul MacLennan is supported through the Center for Injury Sciences at UAB.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Aaron Creek and Jeffery Sawyer declare no conflicts of interest.

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, San Francisco, California, 2012.

Contributor Information

Shawn R. Gilbert, Email: srgilbert@uabmc.edu, University of Alabama at Birmingham, ACC 316, 1600 7th Ave South, Birmingham, AL 35233, Phone: 205-939-5385, Fax: 205-939-6049.

Paul A. MacLennan, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1922 7th Ave S, Suite 115, Birmingham, AL 35233.

Ian Backstrom, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1918 East End Ave, Winter Park FL, 37982.

Aaron Creek, University of Tennessee Campbell Clinic, 309 Melville Ave, Greenville, SC 29605.

Jeffrey Sawyer, University of Tennessee Campbell Clinic, 1400 S Germantown Rd, Germantown, TN 38138.

References

- 1.Childhood Obesity Action Network. State Obesity Profiles, 2009. National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality Child Policy Research Center, and Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. from www.childhealthdata.org/browse/snapshots/obesity-2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):518–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gettys FK, Jackson JB, Frick SL. Obesity in pediatric orthopaedics. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;42(1):95–105. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimitri P, Wales JK, Bishop N. Fat and bone in children: differential effects of obesity on bone size and mass according to fracture history. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(3):527–536. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimitri P, Bishop N, Walsh JS, et al. Obesity is a risk factor for fracture in children but is protective against fracture in adults: A paradox. Bone. 2012;50(2):547–566. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackerman A, Thornton JC, Wang J, et al. Sex difference in the effect of puberty on the relationship between fat mass and bone mass in 926 healthy subjects, 6 to 18 years old. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(5):819–825. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole ZA, Harvey NC, Kim M, et al. Increased fat mass is associated with increased bone size but reduced volumetric density in pre pubertal children. Bone. 2012;50(2):562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson PL, Goulding A, Chalmers DJ. Biomechanical analysis of arm fracture in obese boys. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39(9):657–664. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Backstrom IC, MacLennan PA, Sawyer JR, et al. Pediatric Obesity and Traumatic Lower Extremity Long Bone Fracture Outcomes. J Trauma Aucte Care Surg. 2012;73(4):966–971. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825a78fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slongo TF, Audigé L A.P.C. Group. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium for children: the AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures (PCCF) J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 Suppl):S135–S160. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200711101-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slongo T, Audigé L, Clavert JM, et al. The AO comprehensive classification of pediatric long-bone fractures: a web-based multicenter agreement study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(2):171–180. doi: 10.1097/01.bpb.0000248569.43251.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slongo T, Audigé L, Lutz N, et al. Documentation of fracture severity with the AO classification of pediatric long-bone fractures. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):247–253. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Control, C.f.D. Clinical Growth Charts. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/clinical_charts.htm.

- 14.Barlow SE Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leet AI, Pichard CP, Ain MC. Surgical treatment of femoral fractures in obese children: does excessive body weight increase the rate of complications? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(12):2609–2613. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pomerantz WJ, Timm NL, Gittelman MA. Injury patterns in obese versus nonobese children presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):681–685. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zonfrillo MR, Nelson KA, Durbin DR, et al. The association of weight percentile and motor vehicle crash injury among 3 to 8 year old children. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2010;54:193–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Survey of Children's Health. NSCH. Data query from the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health website. [Retrieved 08/26/2013];2007 from www.childhealthdata.org.

- 20.Gilbert SR, Savage AJ, Whitesell R, et al. Influence of Body Mass Index on Magnitude of Scoliosis at Presentation. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson RC. Tibia vara: a complication of adolescent obesity. J Pediatr. 1992;121(3):482–486. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81811-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolai RD, Grasemann H, Oberste-Berghaus C, et al. Serum insulin-like growth factors IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in children with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8(2):103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery CO, Young KL, Austen M, et al. Increased risk of Blount disease in obese children and adolescents with vitamin D deficiency. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(8):879–882. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181f5a0b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabharwal S, Sakamoto SM, Zhao C. Advanced bone age in children with blount disease: a case-control study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(5):551–557. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318285c524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, et al. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell. 2000;100(2):197–207. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, et al. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111(3):305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(10):772–783. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Afghani A, Goran MI. The interrelationships between abdominal adiposity, leptin and bone mineral content in overweight Latino children. Horm Res. 2009;72(2):82–87. doi: 10.1159/000232160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smotkin-Tangorra M, Purushothaman R, Gupta A, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20(7):817–823. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2007.20.7.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goulding A, Taylor RW, Jones IE, et al. Overweight and obese children have low bone mass and area for their weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(5):627–632. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flynn J, Foley S, Jones G. Can BMD assessed by DXA at age 8 predict fracture risk in boys and girls during puberty?: an eight-year prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(9):1463–1467. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goulding A, Jones IE, Taylor RW, et al. More broken bones: a 4-year double cohort study of young girls with and without distal forearm fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(10):2011–2018. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skaggs DL, Loro ML, Pitukcheewanont P, et al. Increased body weight and decreased radial cross-sectional dimensions in girls with forearm fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(7):1337–1342. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.7.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wearing SC, Henig EM, Byrne NM, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders associated with obesity: a biomechanical perspective. Obes Rev. 2006;7(3):239–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anglen JO, Choi L. Treatment options in pediatric femoral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(10):724–733. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000192294.47047.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson OL, Morrissy RT, Gerdes MH, et al. Early casting of femoral shaft fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4(1):16–21. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.