Abstract

Purpose

Although penile duplex Doppler ultrasonography (PDDU) is a common and integral procedure in a Peyronie's disease workup, the intracavernosal injection of vasoactive agents can carry a serious risk of priapism. Risk factors include young age, good baseline erectile function, and no coronary artery disease. In addition, patients with Peyronie's disease undergoing PDDU in an outpatient setting are at increased risk given the inability to predict optimal dosing. The present study was conducted to provide support for a standard protocol of early administration of phenylephrine in patients with a sustained erection after diagnostic intracavernosal injection of vasoactive agents to prevent the deleterious effects of iatrogenic priapism.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective review of Peyronie's disease patients who received phenylephrine reversal after intracavernosal alprostadil (prostaglandin E1) administration to look at the priapism rate. Safety was determined on the basis of adverse events reported by subjects and efficacy was determined on the basis of the rate of priapism following intervention.

Results

Patients with Peyronie's disease only had better hemodynamic values on PDDU than did patients with Peyronie's disease and erectile dysfunction. All of the patients receiving prophylactic phenylephrine had complete detumescence of erections without adverse events, including no priapism cases.

Conclusions

The reversal of erections with phenylephrine after intracavernosal injections of alprostadil to prevent iatrogenic priapism can be effective without increased adverse effects.

Keywords: Alprostadil; Male urogenital diseases, Peyronie's disease; Phenylephrine; Priapism

INTRODUCTION

Priapism is the persistence of erection that is not associated with sexual stimulation [1]. The most common etiology of priapism is intracavernosal injection therapy with vasoactive drugs such as papaverine or prostaglandin E1 (PGE1). The incidence of iatrogenic causes ranges from 0.26% to 10.26% [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Predictive factors of prolonged erections include young age, good baseline erectile function, and absent coronary artery disease [10]. Intracavernosal agents have a number of utilities in addition to erectile dysfunction treatment. They can facilitate erection for office-based examinations, such as a penile duplex Doppler ultrasonography (PDDU) in the workup of Peyronie's disease [11]. These patients will almost invariably undergo PDDU for evaluation of erectile function, plaque size, penile curvature, and hemodynamic function [12]. The use of vasoactive agents carries a risk of inducing iatrogenic priapism [13]. Patients receiving these injections in an outpatient setting are at increased risk because of the inability to predict optimal dosing. Furthermore, Deveci et al. [14] reported the prevalence of erectile dysfunction in Peyronie's patients to be approximately 35% (self-reported at presentation), with 18% of those patients having normal results on hemodynamic PDDU studies.

Therefore, given that the majority of Peyronie's disease patients are expected to have normal or near-normal erectile function, this patient group was chosen to evaluate the risk of iatrogenic priapism following intracavernosal vasoactive agent injection therapy. Phenylephrine has been well described as a method of priapism treatment. The aim of our study was to analyze the utility of "early" prophylactic administration of low-dose phenylephrine in patients with sustained erections after diagnostic injections of vasoactive agents to prevent the deleterious effects of iatrogenic priapism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective review of all patients with Peyronie's disease in a specialized practice was performed to analyze the effects of low-dose phenylephrine as a prophylaxis against iatrogenic priapism. A total of 78 patients underwent a workup for Peyronie's disease that included a focused history and physical examination as well as PDDU. All patients were given 10 µg of alprostadil, with an additional 10 µg to achieve adequate response (rigidity 4-5) when the initial injection was insufficient. Clinician assessment and grading of penile rigidity (on a scale of 1-5) as well as degree and direction of penile curvature were recorded by a single urologist (H.S.N). Rigidity was classified as 5/5 if there was complete fullness as determined by the same clinician. A score of 3/5 was given if there was 50% fullness. A score of 1/5 was given if there was no fullness or response to vasoactive injection. Subsequently, the patients underwent PDDU to obtain peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end diastolic velocity (EDV). Following the study, the patients were reevaluated at 15 minutes after the completion of the exam (approximately 45-60 minutes after alprostadil injection) to assess for persistent penile rigidity. The patients with unsubsided penile rigidity evaluated as 4 to 5 out of 5 at 15 minutes after the PDDU study were given 200-µg intracavernosal phenylephrine combined with 5 minutes of firm pressure at the injection site to achieve full detumescence. Patients were asked to report any symptoms, including lightheadedness, headaches, or palpitations. Blood pressure and heart rate were monitored within 10 minutes of phenylephrine injection.

A database was compiled to include patient demographics, duration of symptoms, degree and direction of curvature, associated symptoms, erectile function, medical comorbidities, PDDU results, and complications. One patient required immediate phenylephrine reversal because of unbearable discomfort secondary to alprostadil injection (excluded from study results). The remaining 77 patients were divided into 2 groups on the basis of rigidity following the examination: 1-3 vs. 4-5. A total of 44 patients with 4-5 rigidity were further analyzed to determine the proportion with reported erectile dysfunction and the correlation with PDDU analyses. Chi-square with Yates correction and two-tailed t-tests were used to analyze comorbidities, demographics, erectile function, and PDDU measurements where appropriate. Finally, 95% confidence intervals of studies reporting iatrogenic priapism rates were calculated. Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Co., Redmond, WA, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

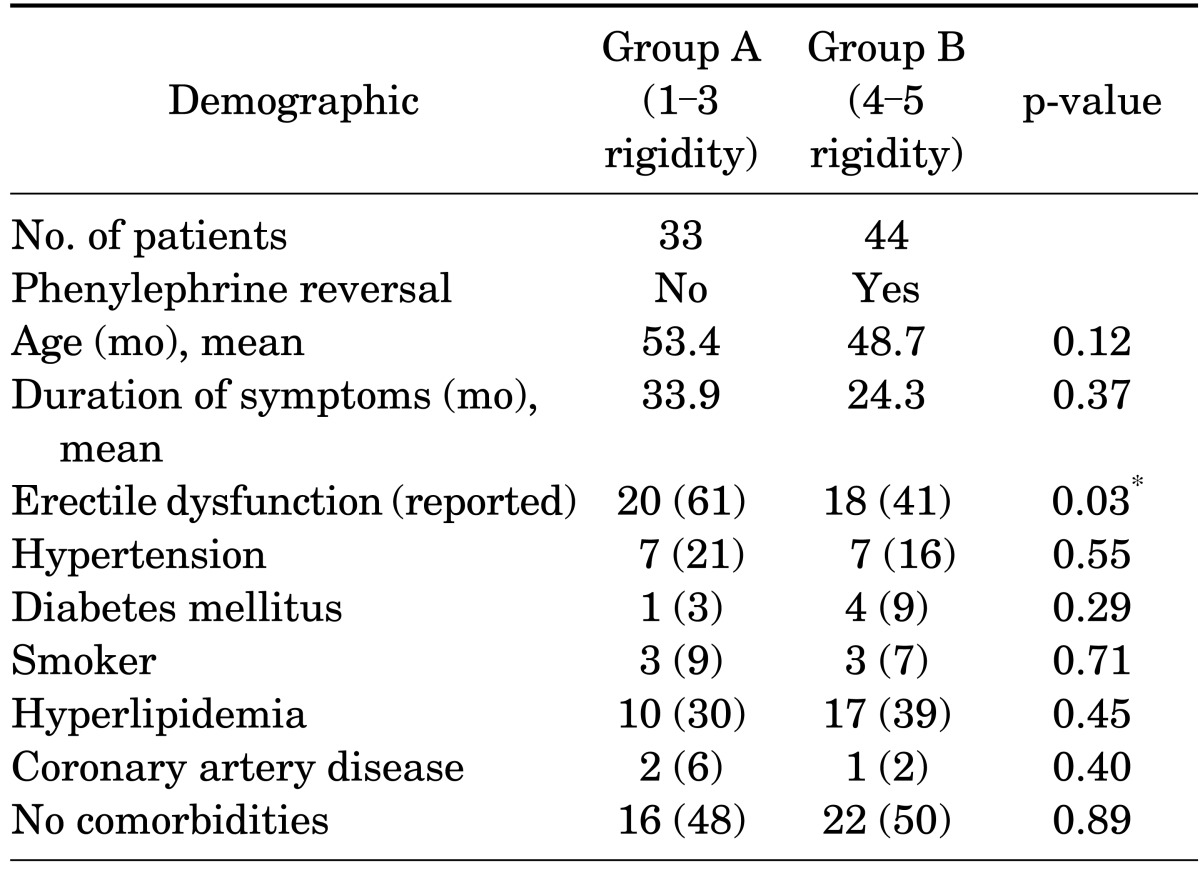

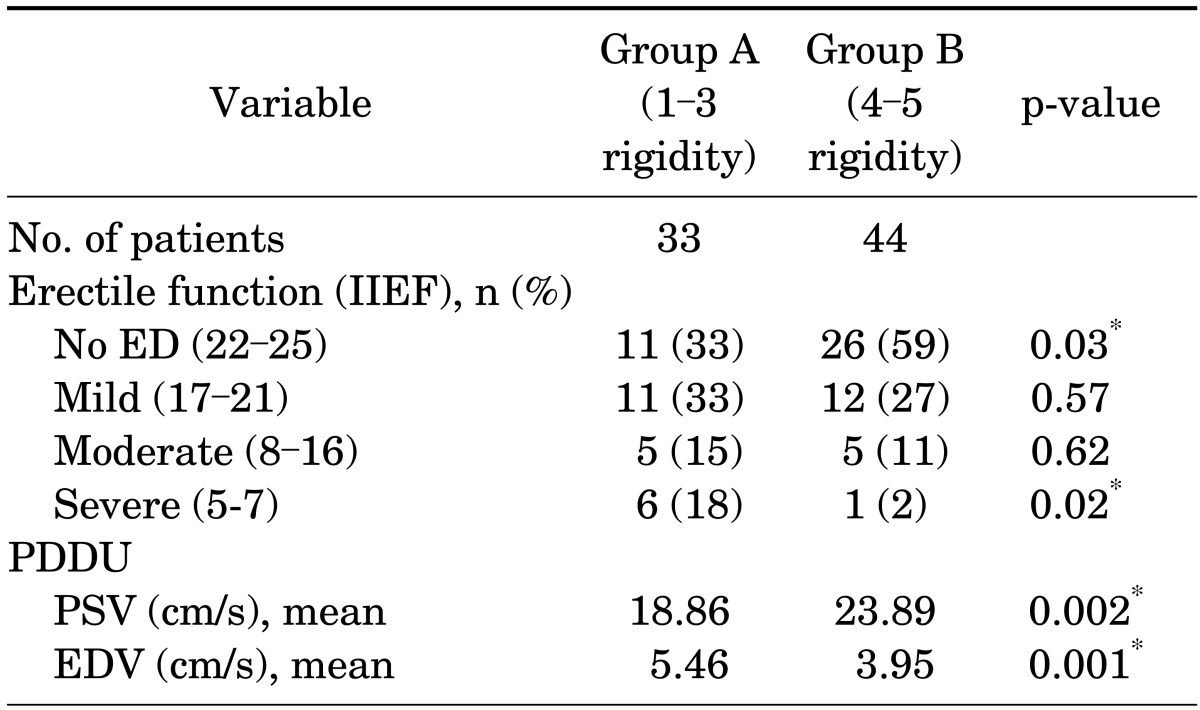

Of the 77 patients studied, 44 had persistent rigidity (score 4-5) approximately 45 to 60 minutes after receiving alprostadil injection and received phenylephrine reversal. Table 1 reports the patients' demographic characteristics and comorbidities, which did not differ significantly between the two groups. Table 2 compares the two groups by baseline erectile function as reported by subjective International Index of Erectile Function [15] categories and objective hemodynamic measurements (mean PSV and EDV). Group B had significantly more patients with normal reported erectile function and better hemodynamic values.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and comorbidities

Values are presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

*Significant (p<0.05).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of erectile function with IIEF scores and PDDU hemodynamic values

IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function; ED, erectile dysfunction; PDDU, penile duplex Doppler ultrasonography; PSV, peak systolic velocity; EDV, end diastolic velocity.

*Significant (p<0.05).

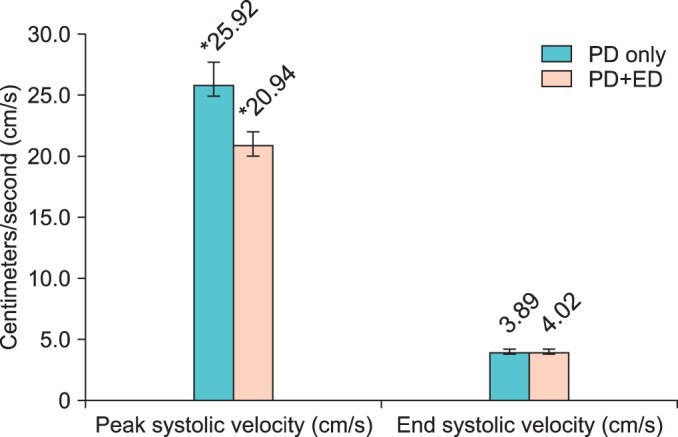

The 44 patients in group B who received phenylephrine were further divided into subgroups, with 26 patients reporting no erectile dysfunction. Comparison of patients with Peyronie's disease only (PD only) versus patients with Peyronie's disease and erectile dysfunction (PD+ED) showed that PD only patients had higher PSV and lower EDV than would be expected (Fig. 1). There was a significant difference in PSV for PD only (25.92±7.30) and PD+ED (20.94±5.71, p=0.02). The difference in EDV between the two groups was not significant.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of penile duplex Doppler ultrasonography values in patients receiving low-dose phenylephrine. PD, Peyronie disease; PD+ED, Peyronie disease and erectile dysfunction.

*Significant (p<0.05).>

All 44 patients achieved complete detumescence following injection of phenylephrine. There were no reports of hypotension, palpitation, or other adverse effects during or after the study. Average blood pressure change was <10 mmHg systolic. A number of patients (n=12) in both groups had complained of a "throbbing sensation" in the penis for up to 2 hours after the study, but it was difficult to assess whether this transient sensation was due to phenylephrine or to the initial alprostadil injection. The priapism rate was 0%.

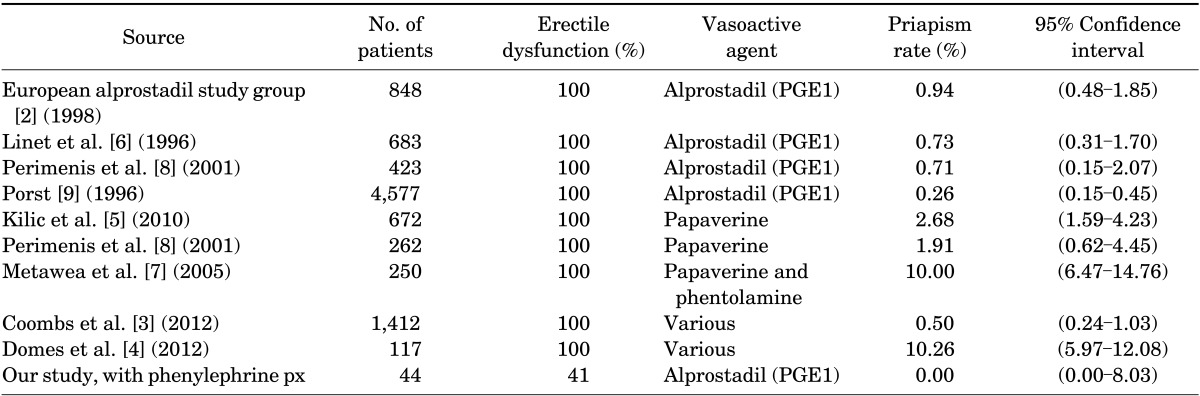

Table 3 summarizes the results of a literature search on previous studies of iatrogenic priapism rates resulting from intracavernosal injection of vasoactive agents. All studies were conducted in patients with existing erectile dysfunction, with the incidence of iatrogenic priapism ranging from 0.26% to 10.26%. There were noticeably higher incidences of iatrogenic priapism with papaverine versus alprostadil injections. The use of alprostadil yielded lower rates of priapism, ranging from 0.26% to 0.94% (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Reported rates of iatrogenic priapism secondary to intracavernosal injection of vasoactive agents

PGE1, prostaglandin E1; px, prophylaxis.

DISCUSSION

Iatrogenic priapism is a serious complication of diagnostic and therapeutic intracavernosal injection of vasoactive agents. The detrimental effects of priapism have been described extensively in the literature as biochemical alterations that produce histologic changes that result in cavernosal damage [16]. Juenemann et al. [17] demonstrated that hypoxia and intracorporeal acidosis occur 4 hours after erection onset as seen in corporal blood gas analysis. This anoxia and acidosis combined with glucose deprivation results in significantly diminished cavernosal smooth muscle tone and irreversible contractile dysfunction [12,18]. Low-flow priapism can result in irreversible cellular damage and corporal fibrosis, which results in significant morbidity of permanent erectile dysfunction [16,19].

Patients with Peyronie's disease are intuitively thought to be at higher risk for iatrogenic priapism because a substantial number of these patients have normal erectile function. As shown in Table 3, previous studies that attempted to identify iatrogenic priapism rates were conducted in patients with existing erectile dysfunction. In fact, we were unable to identify any studies that specifically reported on the use of intracavernosal injections in patients with a similar erectile function profile as our patients. Thus, the findings of this pilot study underscore the safety and efficacy of preemptive and "early" use of intracavernosal phenylephrine injection to achieve detumescence, particularly in patients with normal baseline erectile function.

Intracavernosal phenylephrine for reversal of prolonged erections has been well established as an important therapeutic intervention that is safe and effective [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Azocar et al. [26] noted that 93.1% of cases achieved detumescence and no adverse complications were identified. Munarriz et al. [22] demonstrated that high-dose intracavernosal phenylephrine (mean dose, 2059±807 µg) can be used for management without adverse effects or significant changes in vital signs. We found that a minimal dose of 200 µg of phenylephrine resulted in complete detumescence without any adverse effects.

Our experience with Peyronie's disease patients showed 59% to have normal erectile function. All patients who had persistent penile rigidity (score of 4-5) approximately 45 to 60 minutes after alprostadil injection received prophylactic phenylephrine. All patients achieved complete detumescence, without any cases of iatrogenic priapism. Although the published studies reviewed in Table 3 also reported low rates of iatrogenic priapism, the patient population studied was different from the typical Peyronie's disease patient, as discussed above.

Thus, in our study, absent a proactive intervention with vasoactive agents (i.e., reversal with an alpha adrenergic agent), it would be expected that a number of patients will have prolonged, painful erections that require further pharmacologic injections, penile aspiration, or surgical intervention after induction of an erection with papaverine or PGE1. This further treatment entails additional unnecessary and stressful time spent with a health care provider, as well as expenditure of more health care dollars in the form of added visits to emergency rooms and urgent care centers. Furthermore, the persistence of erection can be alarming and exceedingly uncomfortable for patients who have already endured the discomfort of intracavernosal injection therapy for PDDU. Preempting the emergency management of priapism by identifying those patients at higher risk for developing iatrogenic priapism can minimize stressors on both patients and the health care system. Although waiting in the office and receiving vasoactive injection requires spending extra time at the office at the outset, this brief intervention will lead to better outcomes overall by reducing the chances of more extensive and time-consuming interventions if the same patient were to present to the Emergency Department or the physician's office after a 3- to 4-hour priapism episode.

Our study was limited by sample size, given that Peyronie's disease is fairly uncommon. In addition, the penile curvature could have affected the hemodynamic studies, depending on the direction and degree of curvature and the plaque location. We note that whereas a small fraction of patients in group A (1-3 rigidity) received phenylephrine reversal because of discomfort and concern, these reversals are not expected to have affected the data analysis because no analyses included group A data beyond assessment of penile rigidity.

Although this was a small pilot study, the implications of the findings are applicable to a much larger group of Peyronie's disease patients who undergo diagnostic testing before starting treatment. Peyronie's disease occurs in less than 10% of men, though its incidence may be underestimated [27]. Less invasive and conservative therapies (versus corrective surgery) that had been "grandfathered" as accepted therapies without formal approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or other licensing authorities were likely less known to the general public or even primary care physicians. In the past year, FDA approval of collagenase clostridium histolyticum intralesional injection for Peyronie's disease has attracted more attention to this pathology. This treatment was shown to statistically significantly improve penile curvature deformity and symptom bother scores on the Peyronie's Disease Questionnaire [28,29]. As a result of the approval of collagenase by the FDA, it is anticipated that this nonsurgical intervention will likely increase the number of patients who may previously have been reluctant to pursue surgical or non-FDA-approved therapies. Owing to increased awareness of the disease and treatment options, more PD patients will likely seek therapies. Collagenase therapy may require up to four treatment cycles, each with two injections and multiple evaluations to assess improvement in penile curvature. The evaluation protocol typically includes a PDDU and intracavernosal injection, along with careful documentation of symptoms [30]. The findings of our study are applicable to patients seeking this treatment who will be undergoing the vasoactive injection and evaluation as described. Specifically, prophylactic and "early" phenylephrine injections as advocated in our study will help to prevent priapism episodes in this particular population. Larger studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of early phenylephrine injections will help to standardize treatment protocols for the increasing number of patients undergoing PDDU with pharmacologic challenge.

CONCLUSIONS

Prophylactic phenylephrine reversal of strong erections persisting beyond 60 minutes following vasoactive induction is warranted to prevent the deleterious physiological effects of prolonged erections, especially in patients who are at higher risk. Future studies should incorporate well-defined endpoints with larger sample sizes to explore the incidence of iatrogenic priapism secondary to diagnostic procedures.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Pryor J, Akkus E, Alter G, Jordan G, Lebret T, Levine L, et al. Priapism. J Sex Med. 2004;1:116–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The European Alprostadil Study Group. The long-term safety of alprostadil (prostaglandin-E1) in patients with erectile dysfunction. Br J Urol. 1998;82:538–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coombs PG, Heck M, Guhring P, Narus J, Mulhall JP. A review of outcomes of an intracavernosal injection therapy programme. BJU Int. 2012;110:1787–1791. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domes T, Chung E, DeYoung L, MacLean N, Al-Shaiji T, Brock G. Clinical outcomes of intracavernosal injection in post-prostatectomy patients: a single-center experience. Urology. 2012;79:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilic M, Serefoglu EC, Ozdemir AT, Balbay MD. The actual incidence of papaverine-induced priapism in patients with erectile dysfunction following penile colour Doppler ultrasonography. Andrologia. 2010;42:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linet OI, Ogrinc FG. Efficacy and safety of intracavernosal alprostadil in men with erectile dysfunction. The Alprostadil Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:873–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604043341401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metawea B, El-Nashar AR, Gad-Allah A, Abdul-Wahab M, Shamloul R. Intracavernous papaverine/phentolamine-induced priapism can be accurately predicted with color Doppler ultrasonography. Urology. 2005;66:858–860. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perimenis P, Athanasopoulos A, Geramoutsos I, Barbalias G. The incidence of pharmacologically induced priapism in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of 685 men with erectile dysfunction. Urol Int. 2001;66:27–29. doi: 10.1159/000056558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porst H. The rationale for prostaglandin E1 in erectile failure: a survey of worldwide experience. J Urol. 1996;155:802–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lomas GM, Jarow JP. Risk factors for papaverine-induced priapism. J Urol. 1992;147:1280–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lue TF, Hricak H, Marich KW, Tanagho EA. Vasculogenic impotence evaluated by high-resolution ultrasonography and pulsed Doppler spectrum analysis. Radiology. 1985;155:777–781. doi: 10.1148/radiology.155.3.3890009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeRoy TJ, Broderick GA. Doppler blood flow analysis of erectile function: who, when, and how. Urol Clin North Am. 2011;38:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerfoot WW, Carson CC. Pharmacologically induced erections among geriatric men. J Urol. 1991;146:1022–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37992-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deveci S, Palese M, Parker M, Guhring P, Mulhall JP. Erectile function profiles in men with Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 2006;175:1807–1811. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)01018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Pena BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broderick GA, Kadioglu A, Bivalacqua TJ, Ghanem H, Nehra A, Shamloul R. Priapism: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and management. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 2):476–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juenemann KP, Lue TF, Abozeid M, Hellstrom WJ, Tanagho EA. Blood gas analysis in drug-induced penile erection. Urol Int. 1986;41:207–211. doi: 10.1159/000281199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muneer A, Cellek S, Dogan A, Kell PD, Ralph DJ, Minhas S. Investigation of cavernosal smooth muscle dysfunction in low flow priapism using an in vitro model. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:10–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eland IA, van der Lei J, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MJ. Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology. 2001;57:970–972. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00941-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dittrich A, Albrecht K, Bar-Moshe O, Vandendris M. Treatment of pharmacological priapism with phenylephrine. J Urol. 1991;146:323–324. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37781-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, Dmochowski RR, Heaton JP, Lue TF, et al. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol. 2003;170(4 Pt 1):1318–1324. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000087608.07371.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munarriz R, Wen CC, McAuley I, Goldstein I, Traish A, Kim N. Management of ischemic priapism with high-dose intracavernosal phenylephrine: from bench to bedside. J Sex Med. 2006;3:918–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ralph DJ, Pescatori ES, Brindley GS, Pryor JP. Intracavernosal phenylephrine for recurrent priapism: self-administration by drug delivery implant. J Urol. 2001;165:1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadeghi-Nejad H, Dogra V, Seftel AD, Mohamed MA. Priapism. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:427–443. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staerman F, Nouri M, Coeurdacier P, Cipolla B, Guille F, Lobel B. Treatment of the intraoperative penile erection with intracavernous phenylephrine. J Urol. 1995;153:1478–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azocar Hidalgo G, Van Cauwelaert R, Castillo Cadiz O, Aguirre Aguirre C, Wohler Campos C. Treatment of priapism with phenylephrine. Arch Esp Urol. 1994;47:785–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenfield JM, Levine LA. Peyronie's disease: etiology, epidemiology and medical treatment. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelbard M, Goldstein I, Hellstrom WJ, McMahon CG, Smith T, Tursi J, et al. Clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability of collagenase clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of peyronie disease in 2 large double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled phase 3 studies. J Urol. 2013;190:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelbard M, Hellstrom WJ, McMahon CG, Levine LA, Smith T, Tursi J, et al. Baseline characteristics from an ongoing phase 3 study of collagenase clostridium histolyticum in patients with Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2822–2831. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellstrom WJ, Feldman R, Rosen RC, Smith T, Kaufman G, Tursi J. Bother and distress associated with Peyronie's disease: validation of the Peyronie's disease questionnaire. J Urol. 2013;190:627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]