Abstract

The optical response of semiconducting monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) is dominated by strongly bound excitons that are stable even at room temperature. However, substrate-related effects such as screening and disorder in currently available specimens mask many anticipated physical phenomena and limit device applications of TMDCs. Here, we demonstrate that that these undesirable effects are strongly suppressed in suspended devices. Extremely robust (photogain > 1,000) and fast (response time < 1 ms) photoresponse allow us to study, for the first time, the formation, binding energies, and dissociation mechanisms of excitons in TMDCs through photocurrent spectroscopy. By analyzing the spectral positions of peaks in the photocurrent and by comparing them with first-principles calculations, we obtain binding energies, band gaps and spin-orbit splitting in monolayer TMDCs. For monolayer MoS2, in particular, we obtain an extremely large binding energy for band-edge excitons, Ebind ≥ 570 meV. Along with band-edge excitons, we observe excitons associated with a van Hove singularity of rather unique nature. The analysis of the source-drain voltage dependence of photocurrent spectra reveals exciton dissociation and photoconversion mechanisms in TMDCs.

Monolayer (1L) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), molybdenum diselenide (MoSe2), or tungsten diselenide (WSe2) are two-dimensional atomic crystals1,2,3. In contrast to graphene4, a prototypical 2D material, 1L-TMDCs are direct band gap semiconductors with strong spin-orbit interactions, which cause spin-splitting of the valence band of TMDCs5,6,7 and allow optical manipulation of spin- and valley- degrees of freedom in these materials8,9,10,11. Two-dimensional confinement, high effective carrier mass and weak screening lead to strong electron-electron interactions and dominance of tightly bound excitons in the optical properties of 1L-TMDCs5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. These extraordinary properties make TMDCs ideal platform for studying many anticipated phenomena including quantum-, valley- and spin-Hall effects6,15,16, superconductivity in monolayer MoS217,18 and many-body effects12,13,19. Moreover, strong light-matter interactions20 make TMDCs excellent materials for ultrasensitive photodetectors21,22,23,24 and energy harvesting devices25. Despite rapid progress in understanding the electronic and optical properties of TMDCs1, important fundamental questions remain unanswered:

What types of excitons exist in TMDCs and what are their binding energies? While calculations predict a plethora of excitonic states with extremely large binding energies26,27, experimental progress has been hampered by large broadening of the excitonic peaks in the available samples5,26.

How do substrate-related effects perturb the intrinsic properties of monolayer TMDCs? Indeed, there are indications that the presence of a substrate can cause strong carrier scattering28,29 and affect exciton energies through screening30.

What are the photoconversion mechanisms in TMDC devices? Despite indications of efficient photoconversion20,21, photodetection21,22,23,24, and strong interest in employing TMDCs as solar cells25, it is currently unclear how strongly-bound excitons in TMDCs dissociate and contribute to the photocurrent.

Our experiments are geared towards answering these questions. First, we eliminate substrate-related screening in TMDCs by fabricating free-standing and electrically contacted MoS2, MoSe2, and WSe2 specimens. We then use photocurrent spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying excitons and their dissociation mechanisms. In monolayer (1L) MoS2, we have observed well-defined peaks at ~1.9 eV and ~2.1 eV (‘A’ and ‘B’) and a broad peak ‘C’ at ~2.9 eV. We attribute the peaks A and B to optical absorption by band-edge excitons, and the peak C to absorption by excitons associated with the van Hove singularity of MoS2. Compared to previously reported optical absorption measurements of supported MoS25, our photocurrent spectra exhibit sharp and isolated peaks with near-zero background between them, suggesting the absence of disorder-related midgap states. Our suspended devices allow us to obtain experimentally, for the first time, the lower bound of the binding energy of band-edge excitons of MoS2, Ebind ≥ 570 meV. Finally, we investigate the photoconversion and photogain mechanisms in monolayer TMDCs. By controlling the source-drain voltage, we observe different dissociation pathways for A/B- and C-excitonic states, demonstrate photogain of the order of 1000 with response times faster than 1 ms, and investigate the mechanism of this photogain. We also demonstrate the universality of our techniques by performing measurements on other materials, such as bi- and multi-layer MoS2, monolayer MoSe2 and monolayer WSe2. Our results demonstrate, for the first time, that photocurrent spectroscopy is an efficient tool for probing single- and many-body states in pristine TMDCs and suggest the application of TMDCs as efficient photodetectors with a voltage-tunable spectral response.

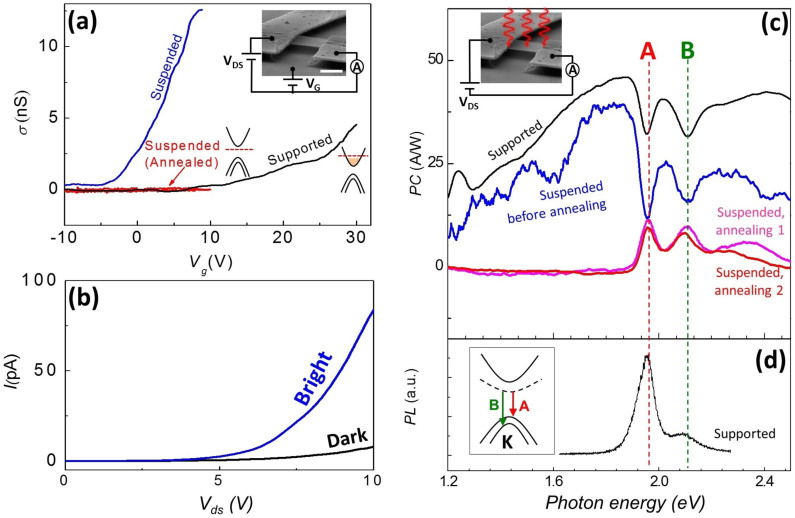

In attempt to decrease the substrate-induced screening and disorder in TMDCs, we studied 14 electrically contacted suspended devices with typical dimensions ~1 μm × 1 μm made from different TMDCs following the approach developed for graphene28 (see Supplementary Information, S1 for details). Initially, we focus on 1L-MoS2 devices (Fig. 1a, Inset), while discussing the case of monolayer MoSe2, WSe2, and multilayer MoS2 later. Two-probe electrical transport measurements indicate that upon suspension the field effect carrier mobility (μ) of a typical device (device #1), ~0.05 cm2/Vs, increases by an order of magnitude (Fig. 1a), consistent with a recent report29. We note that since neither the contact resistance nor the carrier density can be determined in the two-probe geometry, the physically relevant Hall or four-probe mobility of the same device may be larger by orders of magnitude31,32,33. To further increase the quality of suspended devices, we rely on thermal annealing, which is effective in improving μ both for graphene28 and multilayer MoS234. Since the low electrical conductance (G) of MoS2 devices precludes annealing via Ohmic heating28, we instead locally heat the region of the wafer that is in thermal contact with the device. The annealing is performed in situ inside a cryostat kept at base temperature T = 77 K using a ~5 W CO2 laser beam, which is defocused (intensity < 20 μW/μm2) to avoid sample damage. Annealed and unannealed MoS2 samples were imaged with atomic resolution using aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy. We did not observe any annealing-induced modification or defects (see Supplementary Information, S2). This annealing renders the device near-insulating under small source-drain bias voltage |Vds| < 1 V (Fig. 1a, red curve). This behavior is consistent with a pristine undoped semiconductor with the Fermi level located inside the band gap. Since the gate voltage is limited to |Vg| < 12 V to avoid electrostatic collapse of MoS2, we are unable to achieve either electron or hole conductivity regimes via electrostatic gating.

Figure 1. Effects of substrate and thermal annealing on conductance and photocurrent of suspended MoS2.

(a) Gate-dependent conductance of supported, suspended, and suspended annealed 1L-MoS2 device #1 at T = 300 K. Inset: Image of the device. The scale bar is 1 μm. Schematically drawn band diagrams show the position of the Fermi level (red dashed line). (b) Dark and bright electrical response of an annealed suspended device #2 at T = 77 K. Illumination intensity is ~3 pW/μm2 and wavelength is λ = 430 nm. (c) Photocurrent (PC) spectrum of a supported and suspended MoS2 device #1 at different stages of thermal annealing at T = 77 K. (d) Photoluminescence spectra for a supported MoS2 device #1 at T = 300 K. Since PL spectra were recorded at room temperature, we manually blue-shift them by 150 meV to allow comparison with PC spectra obtained at T = 77 K (see Supplementary Information, S5 for details). Inset: Bandstructure schematics of MoS2 near K-point illustrating the origin of band-edge excitons. The dashed line represents excitonic states.

To investigate suspended devices further, we measure PC under high Vds (>3 V) (Fig. 1b, blue curve). We illuminate the entire device using a low intensity (≤30 pW/μm2) light source and record photocurrent IPC across the device as a function of the photon energy  (Fig. 1c). The total current through the device is I = Vds G(Vds, n), where G in turn depends on the number of charge carriers n and Vds. Upon illumination with power P, n increases by

(Fig. 1c). The total current through the device is I = Vds G(Vds, n), where G in turn depends on the number of charge carriers n and Vds. Upon illumination with power P, n increases by  , where α is the absorption coefficient, D is the photoconversion probability (the probability of generating an unbound photocarrier by an absorbed photon), and τ is the photocarrier lifetime35. For a constant Vds, the photocurrent is

, where α is the absorption coefficient, D is the photoconversion probability (the probability of generating an unbound photocarrier by an absorbed photon), and τ is the photocarrier lifetime35. For a constant Vds, the photocurrent is

|

where e is the electron charge. The expression inside the brackets is the photogain η, the ratio between the number of photocarriers transported across the device and the number of absorbed photons per unit time. Assuming α(1.9 eV) ~ 0.1 and α(2.9 eV) ~ 0.45 we estimate η ~ 200 at Vds ~ 10 V, for a device #2 (Figs. 1b). In another device #4 we observed η > 1,000.

Equation (1) is central to the analysis of our data as it shows that PC can be used to estimate the intrinsic parameters of TMDCs  , τ, and D. Indeed, since the photogain is weakly wavelength-dependent, peaks in IPC are associated with peaks in

, τ, and D. Indeed, since the photogain is weakly wavelength-dependent, peaks in IPC are associated with peaks in  (See the Supplementary Information, S4 for more detail). On the other hand, the amplitude of IPC is related to photogain, and hence to D and τ. Therefore, similarly to optical absorption measurements, PC spectroscopy allows us to study single- and many-body electronic states in TMDCs36,37. Unlike absorption spectroscopy, PC can be easily measured for an electrically contacted microscopic device in a cryogenic environment, as the device itself acts as its own photodetector. Moreover, high photosensitivity of TMDC phototransistors allows us to use very low illumination intensity in our experiments, thereby excluding artifacts, such as photo-thermoelectric effects38 (which would yield currents <0.1 pA, more than three order of magnitude smaller than the photocurrent measured in our devices) and optically non-linear39 effects arising at high photocarrier densities. We first use PC spectroscopy to probe absorption spectrum

(See the Supplementary Information, S4 for more detail). On the other hand, the amplitude of IPC is related to photogain, and hence to D and τ. Therefore, similarly to optical absorption measurements, PC spectroscopy allows us to study single- and many-body electronic states in TMDCs36,37. Unlike absorption spectroscopy, PC can be easily measured for an electrically contacted microscopic device in a cryogenic environment, as the device itself acts as its own photodetector. Moreover, high photosensitivity of TMDC phototransistors allows us to use very low illumination intensity in our experiments, thereby excluding artifacts, such as photo-thermoelectric effects38 (which would yield currents <0.1 pA, more than three order of magnitude smaller than the photocurrent measured in our devices) and optically non-linear39 effects arising at high photocarrier densities. We first use PC spectroscopy to probe absorption spectrum  of TMDCs, while later investigating the origins of large photogain.

of TMDCs, while later investigating the origins of large photogain.

For substrate-supported and for majority of suspended unannealed devices, we observe two dips (similar to the ones seen previously in photocurrent spectra of bulk TMDCs40) at ~1.9 eV and ~2.1 eV (Fig. 1c) on top of a largely featureless device-dependent background photocurrent. Upon annealing, this background, attributable to absorption by midgap states41 as well as to photogating artifacts42,43 (Supplementary Information, S3) recedes leaving a set of universal features seen in every device. We note that some devices do not require annealing and exhibit clean PC spectrum right after suspension. Photoconductivity spectrum of a high-quality device #2 is shown in Fig. 2a. We observe: (i) Two sharp peaks at ~1.9 eV and ~2.1 eV (labeled ‘A’ and ‘B’, respectively), (ii) near-zero PC signal below the A-peak, between A- and B-peaks and above the B-peak (from ~2.1 eV to ~2.5 eV), (iii) steep growth of PC starting at ~2.5 eV, and (iv) a broad and strong peak ‘C’ at ~2.9 eV. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first observation of the features (ii)–(iv) in PC spectroscopy. Next, we demonstrate that all of these features originate from optical absorption by bound excitons as well as by unbound electron-hole (e–h) pairs in MoS2.

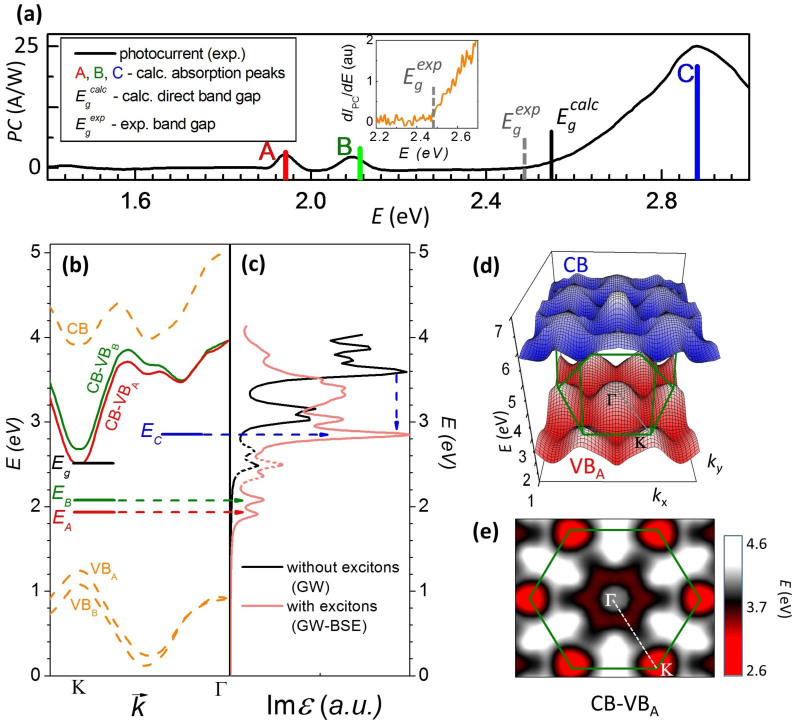

Figure 2. Probing excitons in pristine monolayer MoS2 through photocurrent spectroscopy.

(a) PC spectrum of an intrinsic suspended unannealed 1L-MoS2 device #2 acquired at Vds = 6 V. Background photocurrent due to the surface photovoltage was subtracted (Supplementary Information, S3). Calculated positions of excitonic A-, B- and C-peaks and band gap Eg are shown as colored vertical bars. The bar height represents peaks amplitudes. The inset: derivative of the photocurrent plotted vs. the photon energy. (b) Electronic and optical band structures of 1L-MoS2 along the K-Γ direction. The solid horizontal lines are the estimated positions of the excitonic bound states. (c) Optical spectrum of MoS2 calculated with and without excitonic effects. The dashed peaks between 2.2 eV and 2.7 eV are computational artifacts, which are discussed in the Supplementary Information, S6. Vertical blue arrow indicates the position of the van Hove singularity downshifted by excitonic effects. (d) Three-dimensional plot of the band structure of MoS2. (e) The colorplot of the optical band structure of MoS2. Dark red gear shaped region around Γ is the local minimum corresponding to the excitonic C-peak.

Features A and B stem from optical absorption by the well-known5,7,34 A- and B- band edge excitons of MoS2 residing at K-points of the Brillouin zone (Fig. 1d, Inset). Recombination of these excitons results in photoluminescence peaks at similar spectral positions (Fig. 1d). The ~160 meV separation between the A- and B- peaks is a consequence of the splitting of the valence band of MoS2 at the K point due to spin-orbit interactions5,6,7. The positions of the A- and B-peaks are also in good agreement with the calculated optical spectrum that we obtain using first-principles GW-BSE calculations (Fig. 2c, light-red curve,)27,44,45,46. See Supplementary Information, S6 for details.

The feature at ~2.9 eV (‘C’) has been previously noted in absorption spectrum of MoS25,34,44, but to the best of our knowledge not thoroughly analyzed. We interpret this peak as coming from an excitonic state associated with the van Hove singularity of 1L-MoS2. This van Hove singularity is peculiar, as neither the conduction nor the valence bands have singularities in the density of states in the corresponding region of the Brillouin zone between K and Γ points (orange curves in Fig. 2b and Fig. 2d). At the same time, the bands are locally parallel in that region, causing a local minimum in the Mexican-hat-like optical band structure (difference between conduction and valence bands shown in Fig. 2b as red and green curves). This minimum is prominent in a 2D colorplot of the optical band structure as a continuous gear-shaped region circling the Γ point (Fig. 2e, dark red region). The large joint density of states associated with this minimum yields a strong peak in  . Indeed, our GW calculations (i.e., without inclusion of excitonic effects) of the optical spectrum prominently feature a sharp peak at ~3.45 eV, the value that corresponds to the optical band gap at the van Hove singularity point (Fig. 2c, black curve). Excitonic effects downshift the peak to ~2.9 eV (Fig. 2c, light-red curve), very close to the experimentally measured position of the C-peak. Interestingly, the C-exciton valley of the optical bandstructure is near-rotationally symmetric rendering this exciton effectively one-dimensional47. Moreover, the location of the C-exciton at the bottom of the Mexican hat dispersion suggest that this exciton is localized in both real and momentum space, a conclusion also supported by first-principles calculations26,44.

. Indeed, our GW calculations (i.e., without inclusion of excitonic effects) of the optical spectrum prominently feature a sharp peak at ~3.45 eV, the value that corresponds to the optical band gap at the van Hove singularity point (Fig. 2c, black curve). Excitonic effects downshift the peak to ~2.9 eV (Fig. 2c, light-red curve), very close to the experimentally measured position of the C-peak. Interestingly, the C-exciton valley of the optical bandstructure is near-rotationally symmetric rendering this exciton effectively one-dimensional47. Moreover, the location of the C-exciton at the bottom of the Mexican hat dispersion suggest that this exciton is localized in both real and momentum space, a conclusion also supported by first-principles calculations26,44.

Within the resolution of our measurements (signal-to-noise ratio is ~20 for A/B-peaks), we observe zero photocurrent below the A-peak, between the A- and B-peaks and between the B- and C-peaks. This observation is in contrast with non-zero optical absorption5 and photocurrent in the same region in supported devices measured by us (data in the Supplementary Information, S4) as well as by others5,34. It has been previously suggested48 and observed34,49 that disorder-related midgap states can significantly perturb the optical response of MoS2 leading to below-band gap absorption. Moreover, reduction in the background absorption upon annealing, which is likely associated with reduced disorder, has been recently observed in chemically exfoliated MoS2 samples34. We therefore interpret the lack of PC background in our devices as a signature of the low density of the disorder-related midgap states. Moreover, we do not observe any features due to trions12,13 and trapped excitons49, which suggests that our devices are undoped and contain low defect density. We also note that despite the high quality of our devices, no signatures of anticipated26,50 excited states of A- or B-excitons are observed. This is consistent with the very low oscillator strength of these states expected from a simple 2D hydrogen model (see Supplementary Information, S7).

Above the near-zero photocurrent region, we observe a featureless and abrupt increase of the PC above Egexp ~ 2.5 eV. This increase is clearly visible in the plot of  (Fig. 2a, Inset). The PC onset occurs very close in energy to the calculated fundamental (i.e. single-particle) band gap of 1L-MoS2, Egcalc ~ 2.55 eV (Fig. 2b–c) and is therefore related to direct band-to-band absorption by unbound e–h pairs. However, experimentally we cannot distinguish the onset of the band-to-band absorption from the tail of the C-peak. We therefore interpret that the measured value of Eg is a lower bound for the fundamental band gap value. We can therefore experimentally estimate the exciton binding energy in MoS2 as Ebind = Eg − EA ≥ 570 meV. We emphasize that in our suspended devices the measured values for Eg and Ebind are free from the influence of the substrate-related dielectric screening and hence can be directly compared to calculations (Fig. 2a–c).

(Fig. 2a, Inset). The PC onset occurs very close in energy to the calculated fundamental (i.e. single-particle) band gap of 1L-MoS2, Egcalc ~ 2.55 eV (Fig. 2b–c) and is therefore related to direct band-to-band absorption by unbound e–h pairs. However, experimentally we cannot distinguish the onset of the band-to-band absorption from the tail of the C-peak. We therefore interpret that the measured value of Eg is a lower bound for the fundamental band gap value. We can therefore experimentally estimate the exciton binding energy in MoS2 as Ebind = Eg − EA ≥ 570 meV. We emphasize that in our suspended devices the measured values for Eg and Ebind are free from the influence of the substrate-related dielectric screening and hence can be directly compared to calculations (Fig. 2a–c).

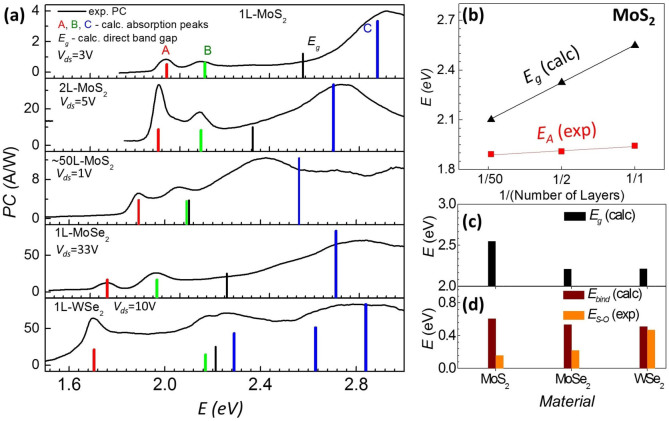

We now turn to bi- and multi-layer MoS2, as well as other 1L-TMDCs, such as MoSe2 and WSe2. Similar A-, B-, and C- features are seen in photocurrent spectra for all of these materials (Fig. 3a). For materials other than 1L-MoS2, however, we do not observe the zero photocurrent between B- and C-peaks. This precludes direct experimental estimation of exciton binding energies in these materials. However, since our first-principles calculations of Eg, A-, B- and C-peaks for 1L MoS2 are in good agreement with the experimental data, we can infer Eg and Ebind of other TMDC materials from corresponding A-, B- and C-peak positions (details are in Supplementary Information, S6). We note the following trends:

The A- and B- peaks in MoS2 do not depend significantly on its thickness (Fig. 3b, red points)5. This is a consequence of simultaneous and nearly equal reduction of Eg (Fig. 3b, black points) and Ebind with the number of layers of MoS251.

The splitting between A- and B- peaks is largest in WSe2 (~510 meV), followed by MoSe2 and MoS2 (Fig. 3d). This is a signature of the stronger spin-orbit interaction in WSe2, related to the higher atomic number of tungsten.

The calculations suggest that variation of the type of chalcogen (S, Se) atom has a strong effect on Eg (Fig. 3c). This is a consequence of the dependence of the lattice constant on the type of chalcogen atoms. On the other hand, Ebind remains roughly constant for all measured materials (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3. Photocurrent in various TMDC materials.

(a) Experimental PC spectra of different TMDC devices. All the devices are suspended and annealed except for the multilayer MoS2 device, which is supported on a glass substrate (Supplementary Information, S1). 1L MoS2 sample is an annealed device #3. For each device, the bias voltage was chosen to maximize the signal to noise ratio for the photocurrent. Solid bars are calculated excitonic peaks and band gap values. Large spin-orbit coupling of WSe2 results in splitting of the valence and the conduction bands even near Γ-point, which leads to splitting of the C-peak. (b) Dependence of excitonic peak positions and band gap values on number of layers of MoS2. (c,d) Comparison of Eg, Ebind and spin-orbit coupling strengths for different 1L-TMDCs.

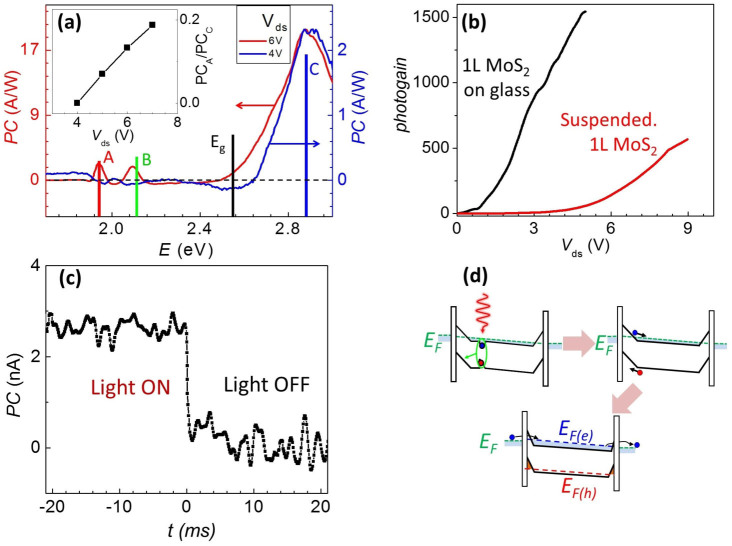

Our next aim is to understand very large PC magnitude. To contribute to photocurrent, a neutral exciton must first dissociate into an unbound electron-hole pair. This process is characterized by the probability D entering into Eq. (1). To investigate the mechanism of dissociation in 1L-MoS2, we examine IPC vs. Vds. We find that the A- and B- peaks in the photocurrent practically disappear at low Vds, while the C-peak remains prominent (Fig. 4a). This behavior is consistent with dissociation of excitons by strong electric fields arising near the interface between MoS2 and metallic contacts. Indeed, a large electric field is required to overcome the binding energy Ebind ≥ 0.6 eV for A-excitons. Such a field can arise at the interface between MoS2 and a metallic contact due to the application of a large bias voltage (like in the case of pristine organic semiconductors52) and possibly due to the mismatch of the work functions of MoS2 and metal (similar to nanotube devices53 and excitonic solar cells54). Our conclusion that PC is produced only at the contacts is also supported by scanning photocurrent microscopy measurements directly mapping photocurrent production23. In contrast, C-excitons exist above the band gap and therefore can produce unbound e–h pair even without application of an external electric field. Thus we demonstrate for the first time electric field assisted dissociation of A- and B-excitons and spontaneous decay of C-excitons into a free electron-hole pairs.

Figure 4. Photoconversion mechanisms in monolayer MoS2.

(a) PC spectra measured in a suspended 1L-MoS2 at two different Vds. Both curves are normalized to the height of the C-peak. Inset: relative PC amplitudes of A- and C- peaks vs. Vds. Note that apparent negative photocurrent around ~2 eV and ~2.5 eV is an artifact caused by our procedure for background subtraction (Supplementary Information, S3). (b) Photogain for a glass-supported and suspended devices vs. Vds. The device is illuminated at λ = 640 nm with intensity ~ 30 pW/μm2. (c) Time response of PC to the varying light intensity in a glass-supported MoS2 (device #4) This measurements sets the upper limit for the response time < 1 ms. Accuracy of time-resolved measurements was limited by the high resistance of MoS2 and therefore high RC-time constant of the measurement circuit. (d) Schematics (not to scale) of the photogain mechanism. EF, EF(e) and EF(h) represents the Fermi level, and quasi-Fermi levels for electrons and holes respectively.

Finally, we analyze the reason for the very large photogain (η > 1,000) and photoresponsivity (~50 A/W) in our devices (Fig. 4b). Photoresponsivity ranging from ~1 mA/W23,24 to ~900 A/W21 has been previously reported for monolayer MoS2 and from ~5 mA/W23 to ~0.6 A/W22 – for multilayer MoS2. Previously suggested mechanisms, such as the direct dissociation at the contacts (yielding η < 1)23 or photothermoelectric effect (yielding η ≪ 0.1)38 cannot explain very high observed photogain. Generally, large gain can be related to multiplication of photocarriers due to the avalanche effect35. It can also originate from long photocarrier lifetime τ due to the trapping of photoexcited carriers either in the defect states (persistent photoconductivity35) or in the band-bending region between a metal contact and a semiconductor55. However, as mentioned above, clean suspended MoS2 devices only start to conduct (G ~ 10−7 S) at large (Vds > Eg/e) source-drain bias (Fig. 1b). Operation in this regime may be complicated by additional effects, such as Zener or thermal breakdown55. On the other hand, we observe that glass-supported MoS2 devices (chosen to eliminate parasitic photogating) have dark conductance G ~ 10−5 S, likely due to the higher doping level of supported MoS2. In agreement with Eq. (1), the photoresponse of these devices is correspondingly higher and can be observed even at small Vds (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the relatively low resistance and correspondingly low RC time-constant of glass-supported devices allows us to measure the time dependence of the photocurrent.

The observation of η ~ 25 at Vds ~ 0.5 V for a glass-supported device #4 (Fig. 4b) rules out the avalanche effect as the mechanism responsible for the observed high photogain. In this regime, the energy eVds is well below the fundamental band gap and is not sufficient to start an avalanche. Persistent photoconductivity has been previously reported in MoS221, but we can exclude it as a possible candidate for the PC generation in clean MoS2 because we routinely observe characteristic photoresponse time < 1 ms at low temperatures (Fig. 4c). This is approximately five orders of magnitude faster than the response time reported for persistent photoconductivity21, but still slower compared to the carrier transit time (time it takes a carrier to travel across the device). The large photogain of our devices is most consistent with photocarrier trapping mechanism also seen in metal-semiconductor-metal and tunnel-emitter phototransistors55. Upon illumination, photoexcited holes are trapped in the potential well formed due to band bending56 at the interface between MoS2 and Au metallic contacts. At the same time, the electrons are injected into the MoS2 channel (Fig. 4d). According to the Eq. 1 this leads to very large changes in the conductivity. First, spatial separation of photocarriers precludes their recombination and greatly increases their lifetime τ. Second, high concentration of holes near the metal-semiconductor junction decreases the thickness of the Schottky barrier and reduces the contact resistance55.

In conclusion, we note several potential applications of the obtained results. First, the large photogain, fast photoresponse, and bias-voltage dependence of the photocurrent spectra of pristine monolayer TMDCs suggest applications of these materials as sensitive and voltage-tunable photodetectors57. Second, the high absorption and dissociation probability of C-excitons may be employed in creating efficient TMDC-based solar cells25,58. Finally, our study confirms that the properties of TMDCs are strongly affected by their environment. This may prove important in designing TMDC-based electronic and optoelectronic devices.

While the manuscript was under review, several groups reported measurements of the binding energy for excitons in 1L TMDCs. Some studies obtained the binding energy ~ 600–700 meV59,60,61, which is very close to our estimates. Others observed lower binding energy ~ 350 meV62,63 for substrate-supported devices, but predict values close to ~500 meV for suspended devices62.

Author Contributions

A.R.K. and A.K.M.N. prepared the samples, performed the experiment and analyzed the data; K.I.B. supervised the project; B.W. and S.T.P. conducted the first-principles calculations; J.L. and S.T.P. conducted the STEM imaging; K.A.V. performed analytical calculations; D.P. prepared the glass-supported TMDC samples; A.R.K., A.K.M.N., H.K., B.L.I. and N.H.T. designed and built the spectroscopic measurement unit; D.C., A.B., N.J.G., J.Y. and D.G.M. grew the TMDC bulk crystals; A.R.K., A.K.M.N. and K.I.B. co-wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors discussed the results.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Jed Ziegler and Richard Haglund for their help with optical measurements and acknowledge stimulating discussions with Tony Heinz. K.I.B. acknowledges support from ONR- N000141310299, NSF CAREER DMR-1056859, HDTRA1-10-0047, and Vanderbilt University. N.H.T. would like to acknowledge support from DOE/BES and ARO through grant numbers FGO2-99ER45781 and W911NF-07-R-0003-02. Samples for this work were prepared at the Vanderbilt Institute of Nanoscale Science and Engineering using facilities renovated under NSF ARI-R2 DMR-0963361 and NSF EPS1004083. N.J.G., J.Y., D.M., and S.T.P. were supported by US DoE, BES, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division.

References

- Wang Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Kis A., Coleman J. N. & Strano M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 699–712 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov K. S. et al. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 102, 10451–10453 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radisavljevic B., Radenovic A., Brivio J., Giacometti V. & Kis A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat Nanotechnol 6, 147–150 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro Neto A. H., Guinea F., Peres N. M. R., Novoselov K. S. & Geim A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev Mod Phys 81, 109–162 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F., Lee C., Hone J., Shan J. & Heinz T. F. Atomically Thin MoS2: A New Direct-Gap Semiconductor. Phys Rev Lett 105, 136805 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D., Liu G. B., Feng W. X., Xu X. D. & Yao W. Coupled Spin and Valley Physics in Monolayers of MoS2 and Other Group-VI Dichalcogenides. Phys Rev Lett 108, 196802 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splendiani A. et al. Emerging Photoluminescence in Monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett 10, 1271–1275 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H. L., Dai J. F., Yao W., Xiao D. & Cui X. D. Valley polarization in MoS2 monolayers by optical pumping. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 490–493 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F., He K. L., Shan J. & Heinz T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 494–498 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallen G. et al. Robust optical emission polarization in MoS2 monolayers through selective valley excitation. Phys Rev B 86, 081301 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Cao T. et al. Valley-selective circular dichroism of monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat Commun 3, 887 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F. et al. Tightly bound trions in monolayer MoS2. Nat Mater 12, 207–211 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. S. et al. Electrical control of neutral and charged excitons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat Commun 4, 1474 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newaz A. K. M. et al. Electrical control of optical properties of monolayer MoS2. Solid State Commun 155, 49–52 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang F. & Niu Q. Unconventional Quantum Hall Effect and Tunable Spin Hall Effect in Dirac Materials: Application to an Isolated MoS2 Trilayer. Phys Rev Lett 110, 066803 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F., McGill K. L., Park J. & McEuen P. L. The valley Hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldán R., Cappelluti E. & Guinea F. Interactions and superconductivity in heavily doped MoS2. Phys Rev B 88, 054515 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K. & Grigorieva I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigner E. On the Interaction of Electrons in Metals. Phys Rev 46, 1002–1011 (1934). [Google Scholar]

- Britnell L. et al. Strong Light-Matter Interactions in Heterostructures of Atomically Thin Films. Science 340, 1311–1314 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Sanchez O., Lembke D., Kayci M., Radenovic A. & Kis A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat Nanotechnol 8, 497–501 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai D.-S. et al. Few-Layer MoS2 with High Broadband Photogain and Fast Optical Switching for Use in Harsh Environments. ACS Nano 7, 3905–3911 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-C. et al. Elucidating the Photoresponse of Ultrathin MoS2 Field-Effect Transistors by Scanning Photocurrent Microscopy. J Phys Chem Lett 4, 2508–2513 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. et al. Single-Layer MoS2 Phototransistors. ACS Nano 6, 74–80 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi M., Palummo M. & Grossman J. C. Extraordinary Sunlight Absorption and One Nanometer Thick Photovoltaics Using Two-Dimensional Monolayer Materials. Nano Lett 13, 3664–3670 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D. Y., da Jornada F. H. & Louie S. G. Optical Spectrum of MoS2: Many-Body Effects and Diversity of Exciton States. Phys Rev Lett 111, 216805 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasubramaniam A. Large excitonic effects in monolayers of molybdenum and tungsten dichalcogenides. Phys Rev B 86, 115409 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin K. I. et al. Ultrahigh electron mobility in suspended graphene. Solid State Commun 146, 351–355 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Jin T., Kang J., Su Kim E., Lee S. & Lee C. Suspended single-layer MoS2 devices. J Appl Phys 114, 164509 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Berkelbach T. C., Hybertsen M. S. & Reichman D. R. Theory of neutral and charged excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys Rev B 88, 045318 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Baugher B. W. H., Churchill H. O. H., Yang Y. & Jarillo-Herrero P. Intrinsic Electronic Transport Properties of High-Quality Monolayer and Bilayer MoS2. Nano Lett 13, 4212–4216 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao W. Z., Cai X. H., Kim D., Sridhara K. & Fuhrer M. S. High mobility ambipolar MoS2 field-effect transistors: Substrate and dielectric effects. Appl Phys Lett 102, 042104 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Radisavljevic B. & Kis A. Mobility engineering and a metal–insulator transition in monolayer MoS2. Nat Mater 12, 815–820 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G. et al. Photoluminescence from Chemically Exfoliated MoS2. Nano Lett 12, 526–526 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soci C. et al. Nanowire Photodetectors. J Nanosci Nanotechno 10, 1430–1449 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. T., Klitzing K. v. & Ploog K. Photocurrent spectroscopy of GaAs/AlxGa1−xAs quantum wells in an electric field. Phys Rev B 33, 4378–4381 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar J. D. et al. High-resolution photocurrent spectroscopy of the positive trion state in a single quantum dot. Phys Rev B 87, 155315 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Buscema M. et al. Large and Tunable Photothermoelectric Effect in Single-Layer MoS2. Nano Lett 13, 358–363 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemla D. S. & Shah J. Many-body and correlation effects in semiconductors. Nature 411, 549–557 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam K. K. & Parkinson B. A. Detailed Photocurrent Spectroscopy of the Semiconducting Group-Vi Transition-Metal Dichalcogenides. J Phys Chem 86, 463–467 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal P. & Klimov V. I. Role of mid-gap states in charge transport and photoconductivity in semiconductor nanocrystal films. Nat Commun 2, 486–493 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M., Low T., Xia F. N. & Avouris P. Photoconductivity of biased graphene. Nat Photonics 7, 53–59 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Konstantatos G. et al. Hybrid graphene-quantum dot phototransistors with ultrahigh gain. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 363–368 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Sánchez A., Sangalli D., Hummer K., Marini A. & Wirtz L. Effect of spin-orbit interaction on the optical spectra of single-layer, double-layer, and bulk MoS2. Phys Rev B 88, 045412 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfing M. & Louie S. G. Electron-hole excitations and optical spectra from first principles. Phys Rev B 62, 4927–4944 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Hüser F., Olsen T. & Thygesen K. S. How dielectric screening in two-dimensional crystals affects the convergence of excited-state calculations: Monolayer MoS2. Phys Rev B 88, 245309 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B., Shklovskii B. I. & Voloshin M. B. Bound state energy of a Coulomb impurity in gapped bilayer graphene. Phys Rev B 89, 041405 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Dolui K., Rungger I. & Sanvito S. Origin of the n-type and p-type conductivity of MoS2 monolayers on a SiO2 substrate. Phys Rev B 87, 165402 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Tongay S. et al. Defects activated photoluminescence in two-dimensional semiconductors: interplay between bound, charged, and free excitons. Sci. Rep. 3, 2657 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. L., Guo S. H., Chan F. T., Wong K. W. & Ching W. Y. Analytic solution of a two-dimensional hydrogen atom. I. Nonrelativistic theory. Phys Rev A 43, 1186–1196 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komsa H.-P. & Krasheninnikov A. V. Effects of confinement and environment on the electronic structure and exciton binding energy of MoS2 from first principles. Phys Rev B 86, 241201 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro L. A. et al. Exciton dissociation and charge carrier recombination processes in organic semiconductors. J Chem Phys 135, 224901 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohite A. D., Gopinath P., Shah H. M. & Alphenaar B. W. Exciton dissociation and stark effect in the carbon nanotube photocurrent spectrum. Nano Lett 8, 142–146 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg B. A. Excitonic solar cells. J Phys Chem B 107, 4688–4698 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Ng K. K. Complete guide to semiconductor devices. International edn, 439–444 (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Fontana M. et al. Electron-hole transport and photovoltaic effect in gated MoS2 Schottky junctions. Sci. Rep. 3, 1634 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. C. et al. Multicolor voltage-tunable quantum-well infrared photodetector. Electron Device Letters, IEEE 14, 566–568 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Eda G. & Maier S. A. Two-Dimensional Crystals: Managing Light for Optoelectronics. ACS Nano 7, 5660–5665 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Chen X. & Cui X. Exciton Binding Energy of Monolayer WS2. arXiv:1403.5108 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ye Z. et al. Probing Excitonic Dark States in Single-layer Tungsten Disulfide. arXiv:1403.5568 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang G. et al. Non-linear Optical Spectroscopy of Excited Exciton States for Efficient Valley Coherence Generation in WSe2 Monolayers. arXiv:1404.0056 (2014).

- Chernikov A. et al. Non-Hydrogenic Exciton Rydberg Series in Monolayer WS2. arXiv:1403.4270 (2014).

- He K. et al. Tightly Bound Excitons in Monolayer WSe2. Phys Rev Lett 113, 026803 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information