Abstract

Background and Purpose

Infarct size and location are thought to correlate with different mechanisms of lacunar infarcts. We examined the relationship between the size and shape of lacunar infarcts and vascular risk factors and outcomes.

Methods

We studied 1679 participants in the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Stroke trial with a lacunar infarct visualized on DWI. Infarct volume was measured planimetrically, and shape was classified based on visual analysis after 3D reconstruction of axial MRI slices.

Results

Infarct shape was ovoid/spheroid in 63%, slab 12%, stick 7%, and multi- component 17%. Median infarct volume was smallest in ovoid/spheroid relative to other shapes: 0.46, 0.65, 0.54, and 0.90 ml respectively, p< 0.001. Distributions of vascular risk factors were similar across the four groups except that patients in the ovoid/spheroid and stick groups were more often diabetic and those with multi-component had significantly higher blood pressure at study entry. Intracranial stenosis did not differ among groups (p=0.2). Infarct volume was not associated with vascular risk factors. Increased volume was associated with worse functional status at baseline and 3 months. Overall, 162 recurrent strokes occurred over an average of 3.4 years of follow-up with no difference in recurrent ischemic stroke rate by shape or volume.

Conclusion

In patients with recent lacunar stroke, vascular risk factor profile was similar amongst the different infarct shapes and sizes. Infarct size correlated with worse short- term functional outcome. Neither shape nor volume was predictive of stroke recurrence.

Keywords: Small subcortical infarcts, Lacunar infarcts, Infarct shape, Infarct size, Diffusion weighted imaging, Lacunar stroke

Introduction

The volume of acute ischemic infarcts has been shown to correlate with stroke severity and functional outcomes in all subtypes of ischemic stroke 1, 2. In patients with lacunar stroke, infarct size in conjunction with infarct location has been proposed to distinguish this subtype from other forms of subcortical ischemic stroke 3. Most lacunar infarcts are caused by occlusion of the penetrating small vessels and classically have a maximum diameter less than 15 mm in the chronic phase 4. Infarct size is typically reported only by maximum lesion diameter on axial imaging, which may inadequately characterize actual volume. Moreover, lesion shape may be an indicator of mechanism 5-7.

Recent three-dimensional (3D) volumetric imaging analyses of chronic lacunar infarcts show that a significant proportion of these lesions does not have spheroid-ovoid morphology and may have more complex shapes 8. Previous imaging studies have suggested that both lacunar infarct volume and shape may be predictive of early neurological deterioration in this population 9, 10.

The relationship between lacunar infarct shape and volume with functional outcome has not been confirmed in a large-scale study of recent lacunar stroke patients, and the predictive value of infarct shape and volume for recurrent ischemic events is unknown. We studied the relationships between infarct shape and volume with vascular risk factors, functional outcome, and recurrent stroke in patients enrolled in the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial, a well-defined cohort in which cardioembolic and carotid stroke etiologies were excluded 11. We sought to determine whether a small acute subcortical infarct associated with a clinical lacunar syndrome could still have different patterns of vascular risk factors based on shape and volume, and the relationship of shape and volume with functional outcome and stroke recurrence. We also examined whether the volume of infarcts differed by shape, and how actual volume compared if we assumed all lacunar infarcts had a spherical/ovoid shape.

Methods

Rationale, design, patient characteristics, and results of the SPS3 trial (NCT00059306) have been previously published 12-15. Briefly, SPS3 was a randomized, multicenter clinical trial conducted at 81 clinical centers in North America, Latin America, and Spain. In a 2-by-2 factorial design, patients with recent (within 180 days) lacunar stroke and without surgically- amenable ipsilateral carotid artery disease or major-risk cardioembolic sources such as atrial fibrillation were randomized to two interventions, to single vs. dual antiplatelet treatment and to one of two target levels of systolic blood pressure control.

Participants with a lacunar syndrome were required to meet MRI criteria to be eligible and to have no evidence of recent or remote cortical infarct, large (>15 mm) subcortical infarct, or prior intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of microbleeds was not an exclusion. The MRI also had to demonstrate an infarct corresponding to the clinical syndrome by at least one of the following four specific imaging criteria: i) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) lesion <20 mm in size at largest dimension (including rostro-caudal extent); ii) well delineated focal hyperintensity <20 mm in size at largest dimension (including rostro- caudal extent) on FLAIR or T2 and clearly corresponding to the clinical syndrome; iii) multiple hypointense lesions of size 3-15 mm at largest dimension (including rostro-caudal extent) only in the cerebral hemispheres on FLAIR or T1 in patients whose qualifying event is clinically hemispheric; iv) well-defined hypointense lesions on FLAIR and/or T1 measuring ≥3 mm, but no more than 15 mm in maximum dimension. Eligibility was determined locally with MRI scans subsequently submitted for central interpretation by a neuroradiologist (CB). Here we consider the 2246 of the 3020 patients with an acute subcortical infarct evident on DWI by central interpretation. Small, old subcortical (lacunar) infarcts had similar appearance as in criterion (iv) but did not correspond to the qualifying clinical syndrome 16. The burden of white matter hyperintensities (WMH) on MRI was evaluated centrally using the age-related white matter changes (ARWMC) scale (range 0-16). A priori, scores of 0-4 were defined as absent-mild disease, 5-8 moderate, and 9+ severe 17. Maximum dimension of the lesion was defined as the greatest of the right-to-left, anterior- to-posterior, and superior-to-inferior dimensions as measured by CB. The superior-to-inferior dimension was computed by multiplying the number of axial sections (minus ½ section) on which the lesion appeared by the sum of the slice and skip thicknesses.

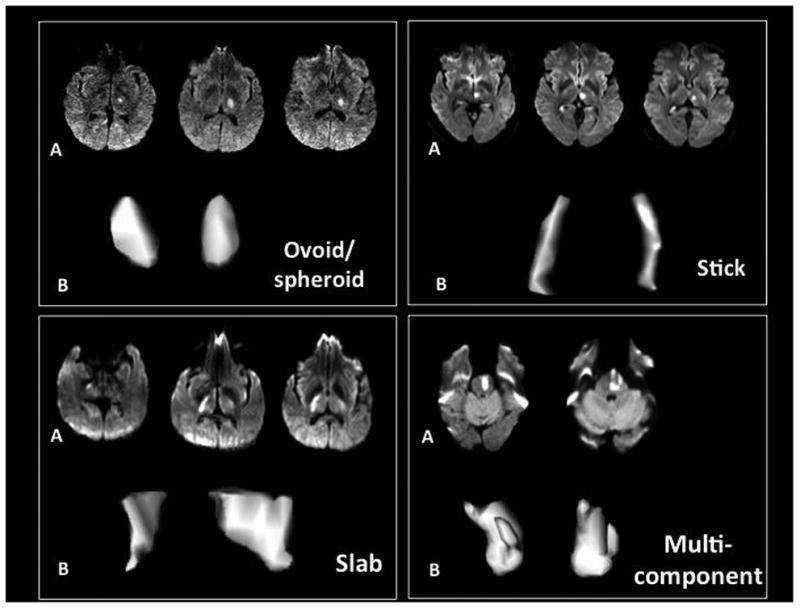

Planimetric DWI lesion volume measurement was performed using Quantomo software 18. DWI lesion borders were defined using a semi-automated threshold intensity technique. The shape of the qualifying lacunar infarct was analyzed using a 3-dimensional (3-D) viewing tool from OsiriX V4.1.1 (32 bit) imaging software. The b1000 DWI images were selected to create a 3-D image of the acute S3 lesion using the 3D surface-rendering program in OsiriX. The surface-pixel value was manually adjusted by the examiner to select only areas with DWI positivity. One of two examiners (NA or MN) classified each lesion shape into one of four categories based on visual analysis: ovoid/spheroid, slab, stick, or multi component 19. A priori, a spheroid/ovoid lesion was defined as a geometric shape created by rotation of an ellipse on or about of its axes, slab as a 3-dimensional cube with one short dimension and two long ones, stick as a 3-dimensional cube with one long dimension and two short dimensions, and multi-component as one not conforming to any of the above geometric shapes. Volume measurements were performed by the same two examiners. Inter-rater reliabilities for volume measurement and shape classification on a random sample of 45 images were very good (Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.97 for volume; Kappa = 0.73, 84% agreement for shape classification.)

Patient characteristics were described using means with standard deviations (SD) [or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR)] and compared across groups using ANOVA (or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) for continuous variables, and using proportions compared across groups with chi-square tests (or Fisher exact test if expected < 5) for categorical variables. Intracranial stenosis was defined as the presence of atherosclerotic disease in the relevant parent artery of equal or greater than 50% based on available intracranial imagining The relationship between the maximum dimension and volume of the acute infarct was explored by fitting various curve functions (e.g. linear, quadratic, power, growth, etc.), checking model assumptions, and then identifying the best fit as determined by highest adjusted r-square. Multivariable logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess independent contributions of infarct shape and volume for predicting disability at 3 months and recurrent ischemic stroke during follow-up respectively. Statistical significance was accepted at the 0.05 level, and no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. All confidence intervals (CI) are two-sided. Analyses were done using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20 (Armonk NY).

Results

Of the 2246 patients enrolled in SPS3 with an acute subcortical infarct evident on DWI, 1679 were included in the current study. A total of 567 (25%) were excluded as their images could not be processed by the measurement software (images were saved on micro-film, not transferrable, or not analyzable by Quantomo software) (Supplemental Figure I). Mean (SD) age of patients included was 62 yr (11) with 76% having a history of hypertension, 38% diabetes, 53% dyslipidemia and 12% ischemic heart disease. The median (IQR) time from the stroke onset to MRI acquisition was 2 (4) days. SPS3 participants excluded from these analysis were similar to those included but with less hyperlipidemia (Supplementary table I).

Infarct shape was ovoid/spheroid in 63%, slab in 12%, stick in 7%, and multi-component in 17% of the 1679 patients (Figure 1-2). Distributions of vascular risk factors were similar across the four groups except that patients in the ovoid/spheroid and stick groups had a higher proportion of diabetes, and those with multi-component had significantly higher blood pressure at study entry. (Table 1) Infarct shape was not associated with the presence of relevant intracranial large artery atherosclerosis. (Table 1) Infarct volumes were the smallest in the ovoid/spheroid group [median (IQR) 0.46 (0.55) ml] and largest in the multi-component group [median (IQR) 0.90 (0.89) ml].

Figure 1. The acute infarcts are categorized into four groups based on their three-dimensional shape.

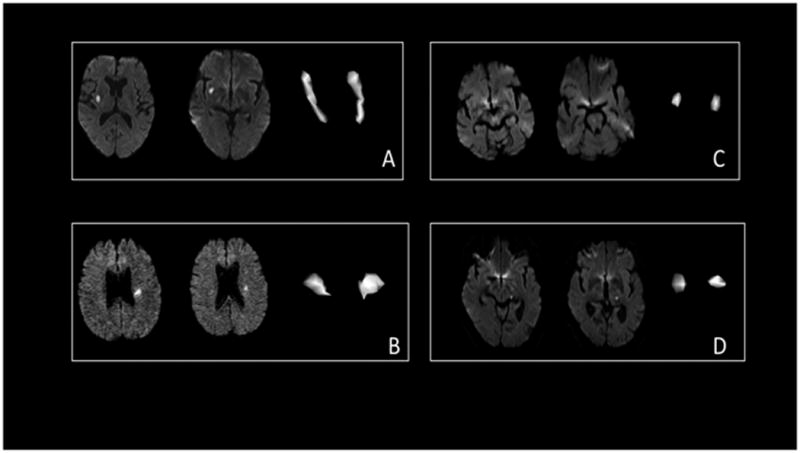

Figure 2.

Examples of large and small infarcts. A: Lentiform infarct measuring 2.2 ml, stick shape. B: A Corona radiata infarct, measuring 0.71 ml, slab. C: Pontine infarct, measuring 0.25 ml, ovoid/spheroid. D: thalamic infarct, measuring 0.48 ml, ovoid/spheroid

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with acute lacunar stroke according to infarct shape.

| Ovoid/spheroid (n = 1055) | Slab (n = 208) | Stick (n = 123) | Multi-component (n = 293) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age, mean (sd) | 63 (11) | 62 (11) | 63 (11) | 62 (11) | 0.7 |

|

| |||||

| Male, % | 63 | 60 | 63 | 61 | 0.9 |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension, % | 76 | 74 | 78 | 76 | 0.8 |

|

| |||||

| Diabetes, % | 40 | 29 | 39 | 34 | 0.008 |

|

| |||||

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 54 | 49 | 54 | 50 | 0.4 |

|

| |||||

| Blood pressure at study entry, mean (sd) | 143 (18) / 78 (11) | 142 (19) / 78 (10) | 139 (20) / 75 (10) | 146 (19) / 79 (10) | 0.02 / 0.009 |

|

| |||||

| Ischemic heart disease, % | 13 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 0.4 |

|

| |||||

| Prior symptomatic lacunar stroke, % | 10 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 0.5 |

|

| |||||

| Relevant intracranial stenosis ≥ 50%, % | 7 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 0.2 |

|

| |||||

| Time (days) from stroke onset to MRI, median (IQR) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0.5 |

|

| |||||

| Infarct volume (ml), median (IQR) | 0.46 (0.55) | 0.65 (0.67) | 0.54 (0.52) | 0.90 (0.89) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Location of qualifying lacunar infarct on MRI, % | < 0.001 | ||||

| basal ganglia | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 | |

| thalamus | 33 | 31 | 20 | 11 | |

| internal capsule | 11 | 22 | 15 | 11 | |

| corona radiata | 23 | 25 | 33 | 44 | |

| centrum semiovale pons | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| medulla/midbrain/cerebellum | 22 | 11 | 21 | 26 | |

| 7 | 1 | 4 | 3 | ||

|

| |||||

| Rankin score at study entry, % | 0.6 | ||||

| 0 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 12 | |

| 1 | 52 | 46 | 52 | 52 | |

| 2 | 25 | 29 | 28 | 28 | |

| 3 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 9 | |

|

| |||||

| Small old lacunar infarcts on FLAIR/T1, % | 33 | 37 | 39 | 34 | 0.5 |

|

| |||||

| WMH –ARWMC score, % | 0.9 | ||||

| absent-mild | 49 | 48 | 50 | 47 | |

| moderate | 28 | 29 | 31 | 30 | |

| severe | 23 | 22 | 19 | 23 | |

Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), White matter hyperintensity (WMH), age-related white matter changes (ARWMC)

Overall median (IQR) infarct volume observed was 0.55 (0.65) ml. Median (IQR) observed volume was 57% (59%) of that predicted assuming a spherical shape lesion with diameter of maximum dimension observed (i.e. volume = 4/3Πr3), with the median (IQR) ovoid/spheroid lesion measuring 67% (63%) of predicted volume. Median (IQR) measured volume of a slab lesion was 46% (41%), a stick lesion 37% (48%), and a multicomponent lesion 44% (39%) of predicted volume assuming a spherical shape. Just over 60% of the variability in volume was explained by the maximum dimension observed. (Supplemental Figure I) Infarct volume was weakly correlated with time from stroke onset to imaging with <1% of variability explained and patients with larger strokes being more likely to have images longer after their stroke than those with smaller strokes (rSpearman = 0.097, p = 0.001). Patients with infarct volumes ≤1 ml were older and more likely to have ischemic heart disease than those with infarct volumes >1 ml. (Table 2) Distributions of vascular risk factors were otherwise similar across the three groups of patients with different infarct volumes.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with acute lacunar stroke by infarct volume.

| ≤ 0.50 ml (n =754) | 0.51-1.0 ml (n = 528) | > 1.0 ml (n = 397) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (sd) | 63 (11) | 63 (11) | 61 (11) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Male, % | 62 | 64 | 61 | 0.6 |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension, % | 77 | 78 | 73 | 0.2 |

|

| ||||

| Blood pressure at study entry, mean (sd) | 143 (18) / 78 (10) | 143 (19) / 78 (11) | 143 (19) / 79 (10) | 0.9 / 0.4 |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes, % | 39 | 36 | 38 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 54 | 52 | 51 | 0.7 |

|

| ||||

| Ischemic heart disease, % | 15 | 11 | 9 | 0.005 |

|

| ||||

| Prior symptomatic lacunar stroke, % | 11 | 9 | 9 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||

| Relevant intracranial stenosis ≥ 50%, % | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1.0 |

|

| ||||

| Time (days) from stroke onset to MRI, median (IQR) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Location of qualifying lacunar infarct on MRI, % | < 0.001 | |||

| basal ganglia | 3 | 3 | 5 | |

| thalamus | 36 | 23 | 18 | |

| internal capsule | 13 | 13 | 11 | |

| corona radiata | 13 | 31 | 51 | |

| centrum semiovale | 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| pons | 23 | 25 | 12 | |

| medulla/midbrain/cerebellum | 10 | 1 | 1 | |

|

| ||||

| Rankin score at study entry, % | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 18 | 14 | 8 | |

| 1 | 54 | 52 | 47 | |

| 2 | 22 | 27 | 33 | |

| 3 | 7 | 7 | 12 | |

|

| ||||

| Small old lacunar infarcts on FLAIR/T1, % | 34 | 34 | 36 | 0.8 |

|

| ||||

| WMH-ARWMC score, % | 0.2 | |||

| absent-mild | 52 | 47 | 47 | |

| moderate | 26 | 30 | 32 | |

| severe | 22 | 23 | 22 | |

Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), White matter hyperintensity (WMH), age-related white matter changes (ARWMC)

Infarct size and shape varied by location (Tables 1 and 2). Thalamic (74%) and those in pons, midbrain, medulla and cerebellum (68%) lesions were more likely (p < 0.001) to be ovoid/spheroid than anterior circulation (53%) lesions and smaller [median (IQR) 0.43 (0.5) ml, 0.45 (0.5) ml, and 0.74 (0.8) ml respectively, p < 0.001)]. Old lacunar infarcts on FLAIR/T1 were evident in 34% of the cohort. Neither infarct shape (p=0.5) nor volume (p=0.8) correlated with the presence of old lacunar infarcts on MRI. (Tables 1 and 2) WMH were absent/mild in 49%, moderate in 29%, and severe in 22% of the cohort. There was no association between infarct shape (p = 0.9) or infarct volume (p = 0.2) and severity of WMH.

Clinical stroke severities as measured by mRS at study entry were similar for patients with different infarct shapes (Table 1), whereas mRS was higher for patients with larger lesion volumes at study entry (Table 2). At study entry, significant functional disability (mRS 2-3) was observed in 29%, 34% and 45% of patients with infarct volumes of ≤ 0.5, 0.51-1.0, and >1.0 ml, respectively. In multivariable analysis, after adjusting for age, diabetes, and prior symptomatic lacunar stroke, infarct volume remained significantly associated with functional disability at study entry and at 3 months post study entry. (Table 3) In these multivariable models, infarct volume, as compared with maximum dimension, was not more strongly associated with functional disability at randomization or at 3 months post-randomization (c-statistic for infarct volume in each model was 0.62 vs. 0.63 for maximum dimension in each model). After adjusting for baseline mRS in addition to age, diabetes, and prior lacunar stroke, neither infarct volume (p = 0.9) nor maximum dimension (p = 0.7) was associated with functional disability at 3 months.

Table 3. Relationships between vascular risk factors, acute infarct volume or maximum infarct dimension, and functional disability: multivariable models.

| Acute Infarct Volume | ||

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) for disability at randomization (mRankin ≥2) | OR (95% CI) for disability 3 months post-randomization (mRankin ≥2) | |

| Age, per 10 year increase | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) |

| Diabetes | 1.7 (1.4, 2.2) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.3) |

| History of lacunar stroke | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.5) |

| Infarct volume, ml | ||

| ≤ 0.50 | reference group | reference group |

| 0.51 – 1.0 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) |

| > 1.0 | 2.1 (1.7, 2.8) | 1.8 (1.4, 2.5) |

| Maximum infarct dimension | ||

| OR (95% CI) for disability at randomization (mRankin ≥2) | OR (95% CI) for disability 3 months post-randomization (mRankin ≥2) | |

| Age, per 10 year increase | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) |

| Diabetes | 1.8 (1.4, 2.2) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.3) |

| History of lacunar stroke | 1.8 (1.3, 2.4) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) |

| Infarct maximum dimension, mm | ||

| <10 | reference group | reference group |

| 10-15 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

| > 15 | 2.3 (1.8, 3.1) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.6) |

During an average follow-up of 3.4 patient-years, 162 first strokes occurred (143 ischemic, 17 hemorrhagic, and 2 uncertain etiology). Considering only the ischemic and uncertain strokes, annualized recurrent ischemic stroke rates were similar for patients with different lesion shapes, i.e. 2.6, 2.0, 2.5, and 2.4% per patient-year for patients with ovoid/spheroid, slab, stick and multi-component infarct shapes respectively (log rank test, p=0.8). Ischemic stroke recurrence rates of 2.6, 2.8, and 2.0% per patient-year were associated with lesion volumes of ≤0.5, 0.51-1.0, and >1.0ml, respectively, not significantly different (log rank test, p= 0.4). In a multivariable analyses adjusting for male sex, black race, diabetes, and prior lacunar stroke or TIA 20, neither infarct shape (p = 0.9, 3 df) nor volume (p = 0.5, 2 df) was significantly predictive of recurrent ischemic stroke.

Discussion

This study is the largest cohort to date to characterize the lesion shape and volume in patients with recent lacunar stroke confirmed by MRI. We did not find correlations between lacunar infarct shape and vascular risk factors at study entry, other than a marginal increase in the proportion with diabetes in those with ovoid/spheroid and stick shaped infarcts. Furthermore, we did not find a correlation between infarct volume and the presence of either relevant intracranial stenosis or risk factors for large vessel disease such as dyslipidemia, and ischemic heart disease. In contrast, we found that patients with larger lacunar infarcts were less likely to have ischemic heart disease, but had otherwise a similar pattern of vascular risk factors. Patients with larger lacunar infarcts were more disabled relative to those with smaller infarcts (either volume or dimension), but neither infarct volume nor shape was predictive of future recurrent strokes in this population.

We postulated that small infarcts with ovoid shape would be associated with MRI markers of small vessel disease, multiple infarcts, and severity of white matter hyperintensities. However, these associations were not demonstrated in our analysis.

Our findings are in contrast to those of multiple neuroimaging studies that suggest that different vascular mechanisms (i.e. embolic, atherothrombotic, etc) of lacunar infarcts may be reflected by differing infarct size, shape and other neuroimaging characteristics such as the burden of old infarcts and leukoaraiosis 21-23. In the original autopsy description of lacunar infarcts,5 Fisher identified two types of vascular pathology: lipohyalinosis and microatheroma. He and others hypothesized that there could be two subtypes of lacunar stroke 24-26. Previous studies concluded that lacunes due to lipohyalinosis are predominantly of ovoid/spheroid shape, smaller in size and associated with multiplicity of infarcts and more prominent leukoaraisosis on MRI 22. Patients in this subtype were more likely to have risk factors for lipohyalinosis as mechanism 27. In our study, the ovoid/spheroid shape comprised over 60% of all lacunar infarct shapes and were significantly smaller than lacunar infarcts of other shapes; however except for a higher rate of diabetes in those with ovoid/spheroid and stick-shape infarcts, we did not find an importantly different pattern of vascular risk factor characteristics between ovoid/spheroid and other shapes. A recent case series of 195 patients with lacunar infarcts that did not exclude patients with atrial fibrillation or ipsilateral cervical carotid stenosis came to similar conclusions 28. Similarly, we did not find a correlation between smaller lacunar infarct size and the degree of white matter disease and presence of prior lacunar stroke on neuroimaging.

In contrast to infarcts secondary to lipohyalinosis, those due to perforating vessel microatheroma were hypothesized to be larger, predominately striato-capsular in location, 29 and to be associated with progression of clinical symptoms and poor prognosis relative to those with lipohyalinosis 30, 31. In our study, the majority of the larger infarcts (>1 ml in total volume) were located in the anterior circulation (predominantly in the corona radiata). We did not find an association between these larger lacunar infarcts and relevant intracranial stenosis. Similarly, we did not find a correlation between smaller lacunar infarct size and the degree of white matter disease and presence of prior lacunar infarcts on neuroimaging. Patients with larger infarcts had similar prognosis from the recurrent ischemic stroke perspective as those with smaller infarct size.

Multiple groups have studied the relationship between acute infarct size and clinical measures of stroke outcome including the Rankin Disability Scale 32-36. Previous volumetric studies, using computed tomographic (CT) scans, either failed to show a positive correlation between the two 37, 38 or only a moderate association between infarct volume and disability 33. They concluded that other factors such as infarct location might have a more important role in predicting outcome than size alone. In contrast, more recent MRI studies in non-lacunar (hemispheric) strokes identified acute DWI infarct volume as an independent predictor of functional dependence 34-36. In lacunar stroke, the correlation between infarct size and functional outcome has been reported only in studies with a small number of patients using either MRI or CT scan imaging 32, 33. Furthermore, the definition of lacunar stroke in these studies was based predominately on radiographic but not clinical characteristics. Our study provides the largest DWI volumetric analysis of acute lacunar stroke patients defined by both clinical and MRI criteria. We found that infarct volume predicts functional disability after adjusting for age and other known predictors of poor outcome in stroke. It did not however provide additional information regarding disability at 3 month after considering the baseline disability. This strong association between size and disability in symptomatic lacunes may be related to the predominantly eloquent location of these lesions. However, our data suggests that baseline disability has a stronger predictive value for 90-day disability that infarct volume. Interestingly, despite the heterogeneous infarct shapes across lacunar patients in our cohort, we found a strong correlation between maximum infarct dimension and infarct volume which suggests that the maximum infarct dimension may be used as a reliable surrogate measure for volume in future studies.

We examined the relationship of shape and volume with recurrent stroke, not recurrent lacunar strokes. About two-thirds of recurrent strokes were grossly classified as “lacunar strokes”. It is possible that shape and volume are predictive of recurrent lacunar stroke, however as we did not have the follow-up MRI or CT available for central reading/adjudication, we were unable to accurately identify the recurrent lacunar strokes.

Our study has limitations. The patients were selected from a cohort enrolled in a randomized control trial of phenotypic cerebral small vessel stroke so patients with other stroke mechanisms (i.e. carotid stenosis, cardioembolic) were not included. It is possible that infarct size/shape may correlate with cardioembolic or carotid risk factors in an excluded subset of symptomatic small subcortical strokes. The median time from stroke onset to imaging was short, however patients were enrolled in our study from 14-180 days after stroke onset and as such early clinical deterioration could not be studied in the present cohort. It is therefore possible that infarct shape or size may correlate with such an outcome. In this analysis we included a large subgroup of the entire SPS3 cohort, i.e. those whose lesions at the DWI stage of evolution could be analyzed by available software, however, we cannot discount the possibility that bias could have been introduced by excluding others. Finally, this was not a pre-specified analysis.

The strengths of our study include an unprecedented sample size of well-characterized patients with a relatively homogenous stroke subtype.

In summary, lacunar infarcts visualized on DWI have heterogeneous shapes, sizes, and locations. However, despite their clinical and radiographic differences they seem to have a similar pattern of vascular risk factors and outcomes. In a clinically and radiographically well-characterized population of patients with recent lacunar strokes, infarct size or shape do not predict recurrent ischemic stroke.

Supplementary Material

Table I. Baseline characteristics of participants included and not included in the analysis

Figure I Relationship between maximum dimension and lesion volume

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: SPS3 was funded by a cooperative agreement (U01NS038529) from the US National Institute of Health-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH-NINDS). NA is supported by a research allowance from the Vancouver General Hospital and University of British Columbia hospital foundation. NM is supported by the Mochida Memorial Foundation for medical and pharmaceutical Research and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Vitalizing Brain Circulation.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Baird AE, Benfield A, Schlaug G, Siewert B, Lovblad KO, Edelman RR, et al. Enlargement of human cerebral ischemic lesion volumes measured by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:581–589. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovblad KO, Baird AE, Schlaug G, Benfield A, Siewert B, Voetsch B, et al. Ischemic lesion volumes in acute stroke by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging correlate with clinical outcome. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:164–170. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seifert T, Enzinger C, Storch MK, Pichler G, Niederkorn K, Fazekas F. Acute small subcortical infarctions on diffusion weighted mri: Clinical presentation and aetiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1520–1524. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.063594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher CM. Lacunes: Small, deep cerebral infarcts. Neurology. 1965;15:774–784. doi: 10.1212/wnl.15.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher CM. The arterial lesions underlying lacunes. Acta Neuropathol. 1968;12:1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00685305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher CM. Lacunar strokes and infarcts: A review. Neurology. 1982;32:871–876. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerraty RP, Parsons MW, Barber PA, Darby DG, Desmond PM, Tress BM, et al. Examining the lacunar hypothesis with diffusion and perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2002;33:2019–2024. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020841.74704.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herve D, Mangin JF, Molko N, Bousser MG, Chabriat H. Shape and volume of lacunar infarcts: A 3d mri study in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke. 2005;36:2384–2388. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185678.26296.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryu DW, Shon YM, Kim BS, Cho AH. Conglomerated beads shape of lacunar infarcts on diffusion-weighted mri: What does it suggest? Neurology. 2012;78:1416–1419. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318253d62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takase K, Murai H, Tasaki R, Miyahara S, Kaneto S, Shibata M, et al. Initial mri findings predict progressive lacunar infarction in the territory of the lenticulostriate artery. Eur Neurol. 2011;65:355–360. doi: 10.1159/000327980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benavente OR, White CL, Pearce L, Pergola P, Roldan A, Benavente MF, et al. The secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes (sps3) study. International journal of stroke : official journal of the International Stroke Society. 2011;6:164–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benavente O, White CL, Roldan AM. Small vessel strokes. Current cardiology reports. 2005;7:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s11886-005-0006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benavente OR, Coffey CS, Conwit R, Hart RG, McClure LA, Pearce LA, et al. Blood-pressure targets in patients with recent lacunar stroke: The sps3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:507–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:817–825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White CL, Szychowski JM, Roldan A, Benavente MF, Pretell EJ, Del Brutto OH, et al. Clinical features and racial/ethnic differences among the 3020 participants in the secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes (sps3) trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:764–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benavente OR, Pearce LA, Bazan C, Roldan AM, Catanese L, Bhat Livezey VM, et al. Clinical-mri correlations in a multiethnic cohort with recent lacunar stroke: The sps3 trial. International journal of stroke. 2014 doi: 10.1111/ijs.12282. published online ahead of print May 27, 2014. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijs.12282/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wahlund LO, Barkhof F, Fazekas F, Bronge L, Augustin M, Sjogren M, et al. A new rating scale for age-related white matter changes applicable to mri and ct. Stroke. 2001;32:1318–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosior JC, Idris S, Dowlatshahi D, Alzawahmah M, Eesa M, Sharma P, et al. Quantomo: Validation of a computer-assisted methodology for the volumetric analysis of intracerebral haemorrhage. International journal of stroke. 2011;6:302–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oomes AH, Dijkstra TM. Object pose: Perceiving 3-d shape as sticks and slabs. Percept Psychophys. 2002;64:507–520. doi: 10.3758/bf03194722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Bakheet MF, Benavente OR, Conwit RA, McClure LA, et al. Predictors of stroke recurrence in patients with recent lacunar stroke and response to interventions according to risk status: Secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;23:618–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gouw AA, Seewann A, van der Flier WM, Barkhof F, Rozemuller AM, Scheltens P, et al. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: A systematic review of mri and histopathology correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:126–135. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.204685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nah HW, Kang DW, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Diversity of single small subcortical infarctions according to infarct location and parent artery disease: Analysis of indicators for small vessel disease and atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2010;41:2822–2827. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen L, Feng J, Zheng D. Heterogeneity of single small subcortical infarction can be reflected in lesion location. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:1109–1116. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boiten J, Lodder J, Kessels F. Two clinically distinct lacunar infarct entities? A hypothesis. Stroke. 1993;24:652–656. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caplan LR. Intracranial branch atheromatous disease: A neglected, understudied, and underused concept. Neurology. 1989;39:1246–1250. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Jong G, Kessels F, Lodder J. Two types of lacunar infarcts: Further arguments from a study on prognosis. Stroke. 2002;33:2072–2076. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000022807.06923.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bezerra DC, Sharrett AR, Matsushita K, Gottesman RF, Shibata D, Mosley TH, Jr, et al. Risk factors for lacune subtypes in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. Neurology. 2012;78:102–108. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823efc42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Bene A, Makin SD, Doubal FN, Inzitari D, Wardlaw JM. Variation in risk factors for recent small subcortical infarcts with infarct size, shape, and location. Stroke. 2013;44:3000–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donnan GA, O'Malley HM, Quang L, Hurley S, Bladin PF. The capsular warning syndrome: Pathogenesis and clinical features. Neurology. 1993;43:957–962. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto Y, Ohara T, Hamanaka M, Hosomi A, Tamura A, Akiguchi I. Characteristics of intracranial branch atheromatous disease and its association with progressive motor deficits. J Neurol Sci. 2011;304:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto Y, Ohara T, Hamanaka M, Hosomi A, Tamura A, Akiguchi I, et al. Predictive factors for progressive motor deficits in penetrating artery infarctions in two different arterial territories. J Neurol Sci. 2010;288:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruno A, Shah N, Akinwuntan AE, Close B, Switzer JA. Stroke size correlates with functional outcome on the simplified modified rankin scale questionnaire. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:781–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saver JL, Johnston KC, Homer D, Wityk R, Koroshetz W, Truskowski LL, et al. Infarct volume as a surrogate or auxiliary outcome measure in ischemic stroke clinical trials. The ranttas investigators. Stroke. 1999;30:293–298. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thijs VN, Lansberg MG, Beaulieu C, Marks MP, Moseley ME, Albers GW. Is early ischemic lesion volume on diffusion-weighted imaging an independent predictor of stroke outcome? A multivariable analysis. Stroke. 2000;31:2597–2602. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo AJ, Barak ER, Copen WA, Kamalian S, Gharai LR, Pervez MA, et al. Combining acute diffusion-weighted imaging and mean transmit time lesion volumes with national institutes of health stroke scale score improves the prediction of acute stroke outcome. Stroke. 2010;41:1728–1735. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.582874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaidi SF, Aghaebrahim A, Urra X, Jumaa MA, Jankowitz B, Hammer M, et al. Final infarct volume is a stronger predictor of outcome than recanalization in patients with proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion treated with endovascular therapy. Stroke. 2012;43:3238–3244. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.671594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chua MG, Davis SM, Infeld B, Rossiter SC, Tress BM, Hopper JL. Prediction of functional outcome and tissue loss in acute cortical infarction. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:496–500. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540290086022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyden PD, Zweifler R, Mahdavi Z, Lonzo L. A rapid, reliable, and valid method for measuring infarct and brain compartment volumes from computed tomographic scans. Stroke. 1994;25:2421–2428. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.12.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table I. Baseline characteristics of participants included and not included in the analysis

Figure I Relationship between maximum dimension and lesion volume