Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Turmeric and its active component curcumin have received considerable attention due to their many recognized biological activities. Turmeric has been commonly used in food preparation and herbal remedies in South Asia, leading to a high consumption rate of curcumin in this region. However, the amount of curcumin in the Korean diet has not yet been estimated, where turmeric is not a common ingredient.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

This study utilized the combined data sets obtained from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted from 2008 to 2012 in order to estimate the curcumin intake in the Korean diet. The mean intake of curcumin was estimated from the amount of curcumin-containing foods (curry powder and ready-made curry) consumed using reported curcumin content in commercial turmeric and curry powders.

RESULTS

Only 0.06% of Koreans responded that they consumed foods containing curcumin in a given day, and 40% of them were younger than 20 years of age. Curcumin-containing foods were largely prepared at home (72.9%) and a significant proportion (20.4%, nearly twice that of all other foods) was consumed as school and workplace meals. The estimated mean turmeric intake was about 0.47 g/day corresponding to 2.7-14.8 mg curcumin, while the average curry powder consumption was about 16.4 g, which gave rise to curcumin intake in the range of 8.2-95.0 mg among individuals who consumed curcumin. The difference in estimated curcumin intake by using the curcumin content in curry powder and turmeric may reflect that curry powder manufactured in Korea might contain higher amounts of other ingredients such as flour, and an estimation based on the curcumin content in the turmeric might be more acceptable.

CONCLUSIONS

Thus, the amount of curcumin that can be obtained from the Korean diet in a day is 2.7-14.8 mg, corresponding to nearly one fourth of the daily curcumin intake in South Asia, although curcumin is rarely consumed in Korea.

Keywords: Curcumin mean intake, curry powder, KNHANES, Korean diet, turmeric

INTRODUCTION

Curcumin [1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadien-3,5-dione] is a polyphenolic compound that gives a strong yellow color to the spice turmeric. Turmeric is the powdered rhizome of Curcuma longa, a member of the ginger family and has been commonly used for flavor and color in food preparation in South Asia [1]. In addition, it has been traditionally used as an herbal medicine to treat inflammatory and other disease conditions [1].

The biological activities of curcumin have been studied extensively. Curcumin has exhibited a wide range of biological activities, including anti-inflammation, lipid-lowering effects, and anticancer properties [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, recent epidemiological and clinical studies indicate that curcumin can also improve cognitive function and cardiovascular health, as well as insulin sensitivity [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Therefore, curcumin has received a great deal of attention due to its potential usefulness to prevent and improve many disease conditions.

In order to achieve the beneficial health effects of curcumin, however, high consumption of curcumin is necessary, although the required dose may vary depending on disease conditions. High doses of curcumin (1.5-4 g/day) are required for the effective treatment of some cancer types including lung and pancreatic cancers [14,15,16], whereas less than 0.5 g of curcumin is effective in treating some inflammatory conditions [17,18]. Turmeric extract was approved by the Korea Food and Drug Administration as a functional food ingredient for its joint health potential at the dose of 1 g/day. No toxicity has been observed during the long history of high curcumin intake in the diet. In South Asian countries, such as India, where curcumin consumption is very high, the estimated average daily intake of turmeric is 1-2 g or higher [19]. Furthermore, clinical studies demonstrated that curcumin at high doses (4-8 g/day) does not give rise to any toxic effect or adverse outcome, and oral intake of 8 g curcumin daily for several months is well-tolerated in treated patients [8].

Curcumin consumption in Korea has not yet been estimated. Curcumin may be consumed in the diet at fairly low levels in most countries including Korea where turmeric is not commonly used in their cooking. However, in Korea, curry that contains turmeric as the main ingredient is popular, and both curry powders and ready-made curries from multiple manufacturers are available in the market. Curry dishes are conveniently prepared at home and frequently included in lunch meal menus offered by schools and workplaces. In addition, owing to the recognized potential health effect of curcumin, turmeric-enhanced curry products have been popular. Therefore, Koreans may consume curcumin higher than one may speculate. It will be informative to estimate how much curcumin can be consumed from the Korean diet with an increasing interest in products having higher turmeric content, as well as the potential health-beneficial effects of curcumin. In this study, the mean intake of curcumin that can be consumed from the Korea diet was estimated from the datasets of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) conducted from 2008 to 2012. This study will estimate how much curcumin can be consumed from the ordinary Korean diet. The obtained information could presumably be utilized to evaluate whether the consumption of curcumin in the general Korean diet could exert any health-promoting effects derived from curcumin.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design

This study is a cross-sectional analysis of the nutritional survey data sets obtained from the KNHANES 2008-2012. KNHANES is a nationwide survey program conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to access the health and nutritional status of Koreans. KNHANES takes place yearly, since the fourth KNHANES was conducted in 2007. The KNHANES sampling involves a multi-stage clustered probability design that includes about 10,000 non-institutionalized Korean citizens aged 1 year and older in each survey year to represent the entire Korean population [20]. The nutritional survey component of the KNHANES assesses dietary behaviors, food frequency, and food intake by face to face interview questions. In this nutritional survey, food intake information is collected using the 24-hour recall interview that is conducted by well-trained staff members aided by various measuring devices [20].

Selection of curcumin-containing food sources

The 24-hour recall data sets of the KNHANES were examined in terms of the variables "diet name", "coded food name", and "other food names or remarks reported by interviewees" to identify food sources that contain curcumin. Turmeric, a major spice in curry and curry powder, is a major dietary source of curcumin. In the KNHANES, turmeric is classified into "ginger", and its consumption was only recognizable by the variable, "other food names or remarks reported by interviewees", which was only recorded if available. The consumption of turmeric (in the form of powder or balls of paste) was reported but was very rare, with no occurrences in 2008 or 2009, and only one case each in 2011 and 2012. Even in 2010, a year when the recorded turmeric intake was the highest, only 7 individuals derived from 3 households reported consumption. Due to the paucity of responders and the difficulty of retrieving information on turmeric consumption, turmeric was not included in the estimation of curcumin intake. Any "coded food name" relating to curry foods was selected to estimate the curcumin intake in the Korean diet.

Dietary assessment and estimation of curcumin consumption

Information on consumption was assessed using all "coded food names" related to curry foods. There are a total of 31 different food codes that correspond to curry foods according to the curry type (powder or ready-made) or commercial name. In fact, when the KNHANES from 2008 to 2012 was examined, a total of 9 food codes (6 of powder and 3 of ready-made types) were relevant to curry foods. The actual amount of curcumin-containing food consumption was obtained for each of the 9 individual "coded food names" using the 24-hour recall data sets combined from 2008 to 2012. Those consumptions were then converted into that of curry powder and turmeric to estimate the mean curcumin intake using the reported curcumin content in commercial turmeric and curry powders, as described in the Results section.

Statistical analysis

Data preparation and statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Five years of nutritional survey data sets derived from KNHANES were combined to assess the characteristics of curcumin consumers and to estimate the amount of curcumin that can be consumed in the Korean diet. A multi-stage sampling design was considered for data generation and analysis. Chi-squared tests and t-tests were performed to determine the differences in demographic characteristics and eating behaviors between curcumin consumers and non-consumers. The resulting estimates were weighted to account for the multi-stage sampling design that was considered to represent the entire Korean population.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics and eating behavior of curcumin consumers

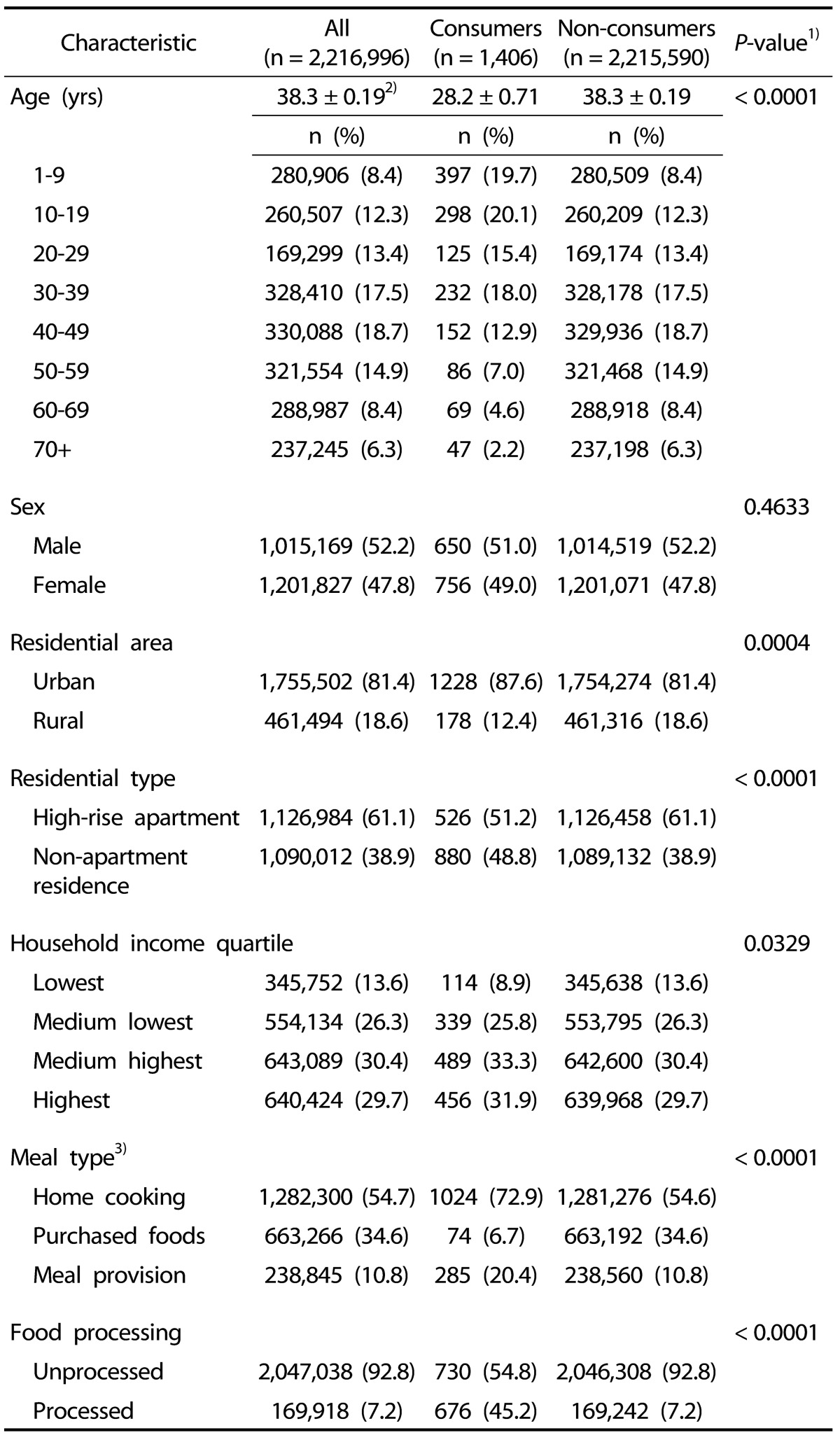

The demographic characteristics and eating behaviors of individuals who consumed curcumin are described in Table 1. The frequency of curcumin intake in a given day was fairly low (0.06%) and those who did not consume curcumin represented the entire population well. Curcumin consumers were younger compared to the non-consumers; about 40% were less than 20 years of age. They more frequently lived in urban areas (87.6%) and resided in non-apartment residences (48.8%) in comparison to 81.4% and 38.9% in individuals who did not consume curcumin, respectively. Curcumin-containing foods (curry powder and ready-made curry) were more often consumed at home (72.9%) or provided at schools or workplaces as lunch meals (20.4%) rather than purchased at restaurants (6.7%) compared to foods that do not contain curcumin. Curry foods were more often consumed as processed food (45.2%) compared to all other foods (7.2%).

Table 1.

Demographic and eating behavioral characteristics of individuals who consumed curcumin in a given day

1) The significance of differences in frequencies and means between curcumin consumers and non-consumers was tested using t-tests and chi-squared tests, respectively.

2) Mean ± SE.

3) Home cooking, foods prepared at residential home; purchased foods, foods purchased at restaurants; meal provision, foods provided in preschool, school, or work place as lunch meals.

Curry consumption for different age groups

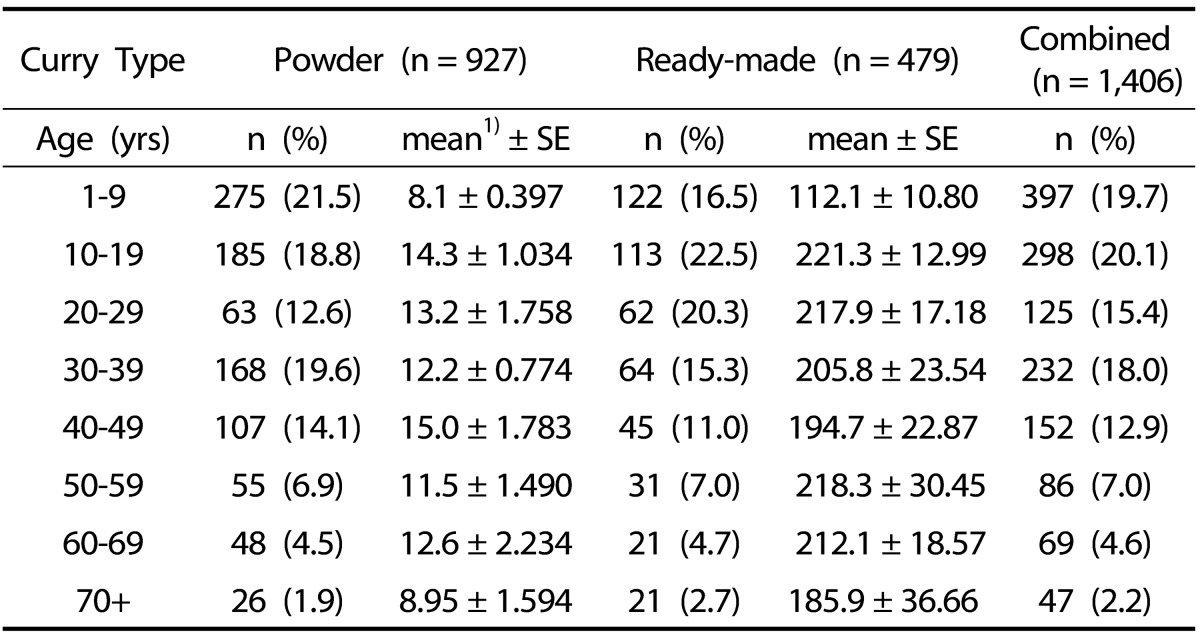

Curcumin-containing foods were consumed mainly in two types, curry powder and ready-made curry. In each curry type consumed, the frequency of consumption and average intake among curcumin consumers in each age group are described in Table 2. Regardless of curry type, the frequency of consumption was higher in younger age groups (1-9 and 10-19 years of age) compared to older age groups (over 50 years). However, the average curry consumption was similar (12-15 g for curry powder and about 200 g for ready-made curry) for all age groups except the youngest (less than 10 years) and the oldest (over 70 years) groups.

Table 2.

Frequency of consumption and average intake of curry powder and ready-made curry among curcumin consumers in each age group

1) Mean, g

Estimation of curcumin consumption

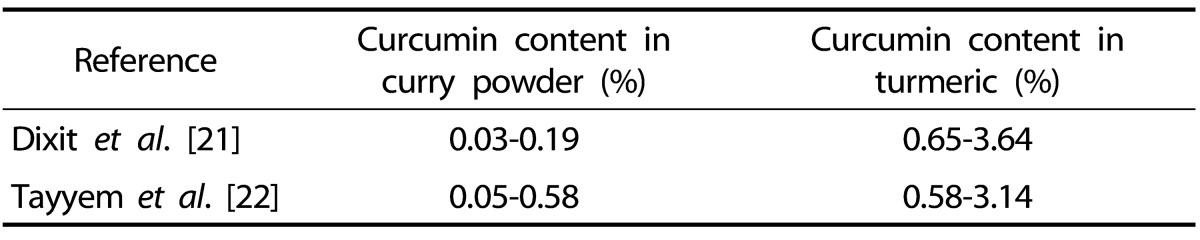

Table 3 summarizes the curcumin content analyzed from turmeric and commercial curry powders in the previous studies [21,22]. The curcumin content varies in curry powder ranging from less than 0.05% to over 0.5%, while turmeric contains a higher amount of curcumin in a relatively narrower range (0.6-3.6%) compared to curry powder (Table 3). The consumption of curry powder and turmeric were derived from the actual consumption amount of curcumin-containing foods (curry powder and ready-made curry) retrieved from the KNHANES 24-hour recall data sets as described below. The mean curcumin intake among individuals who consumed curcumin was then estimated using the curcumin content analyzed from commercial turmeric and curry powders manufactured in different countries including India, Japan, and the United States of America [22] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Curcumin content of commercial curry powder and turmeric

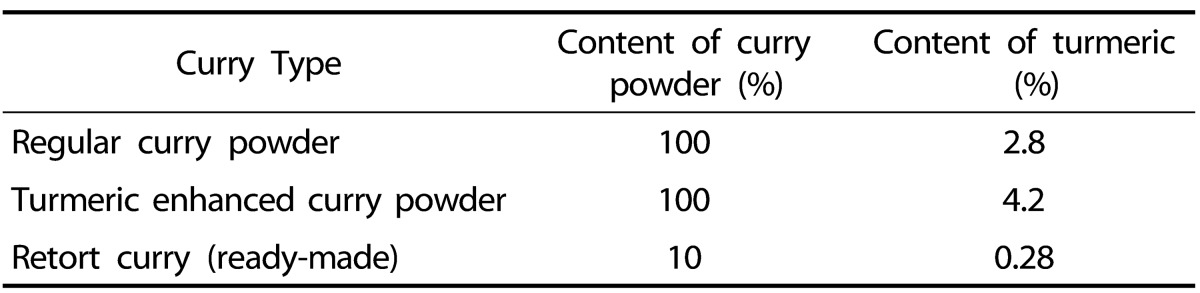

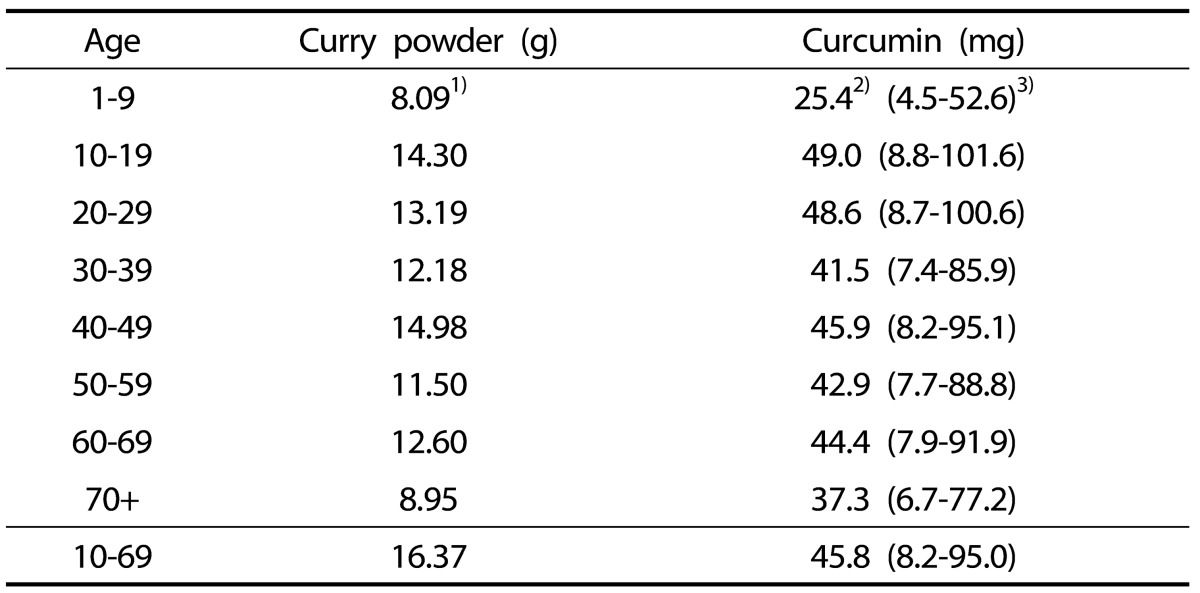

Approximate curry powder contents was calculated for ready-made curry, which is cooked with vegetables and/or meats and processed by retort sterilization in order to convert the consumption of ready-made curry into that of curry powder. Ready-made curry contains about 10% of curry powder by weight when powder and ready-made products from the same manufacturer were compared (Table 4). The resulting mean intake of curry powder was 16.4 g which corresponds to 8.2-95.0 mg curcumin per day in curcumin consumers aged 10-69 years based on the curcumin content of curry powder (Table 5).

Table 4.

Estimation of curry powder and turmeric content from curry products

Table 5.

Curcumin intake among curcumin consumers estimated by the reported curcumin content of commercial curry powder

1) Mean intake of curry powder estimated from consumption amount of curcumin-containing foods according to the calculation described in Table 4.

2) Mean intake of curcumin estimated by the average of curcumin contents analzyed from various commercial curry powders [22].

3) Mean intake of curcumin estimated in the range of the highest and lowest curcumin content from various commercial curry powders [22].

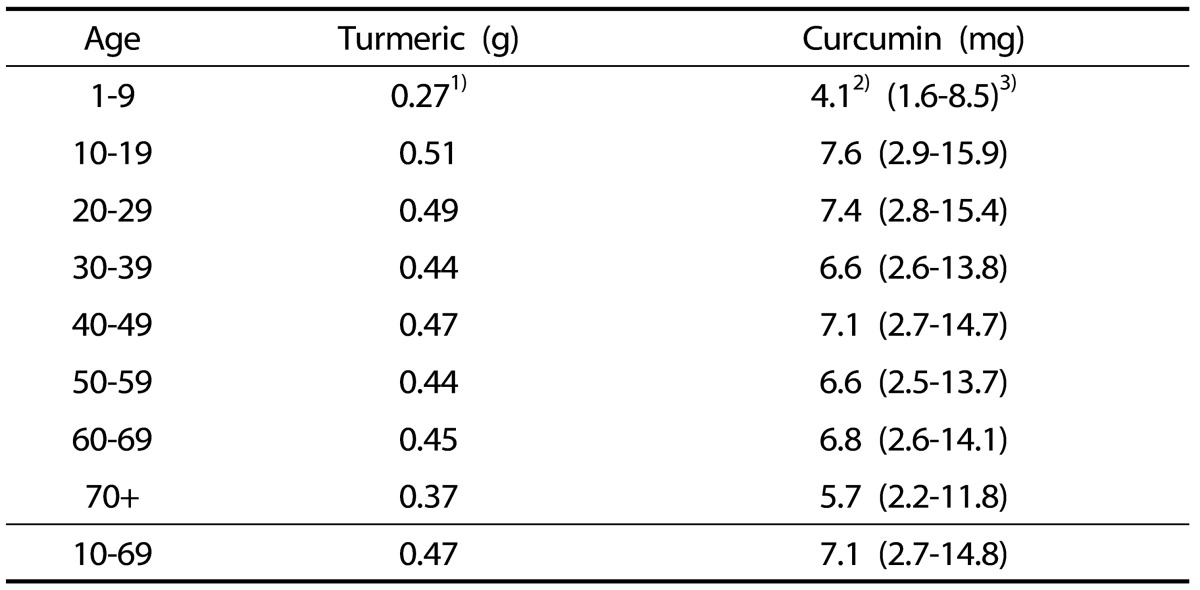

For the estimation of turmeric consumption, first, each "coded food name" corresponding to curry related foods was categorized by turmeric content into three categories: regular curry powder, turmeric-enhanced curry powder (more than 55% increase in turmeric content), and ready-made curry. Among the curry products surveyed in the KNHANES, those high in curry product were selected and their food labels were used for the calculation of the turmeric contents in 100 g of curry product for each category. Accordingly, regular curry powder contains an average of 2.8% turmeric, while approximately 4.2% and 0.28% of turmeric is included in turmeric-enhanced curry powder and ready-made curry, respectively (Table 4). The solid-block type curry contains almost the same amount of turmeric as in the curry powder made from the same manufacturer. No differences were found in the turmeric content according to spiciness (e.g., mild, medium, and hot). Therefore, curry foods were not further divided by flavor strength or block type. Based on the calculation of the turmeric content in each category, the mean intake of turmeric was an estimated 0.47 g (corresponding to 2.7 mg to 14.8 mg curcumin) per day among curcumin consumers aged between 10 and 69 years (Table 6). Unfortunately, many responses were unidentifiable regarding the commercial name of curry powder, so they were classified as regular curry powder. In addition, there were no separate codes for ready-made curry products that contain higher turmeric content than regular products. Therefore, there may be a chance that turmeric consumption is slightly underestimated.

Table 6.

Curcumin intake among curcumin consumers estimated by the reported curcumin content of commercial turmeric

1) Mean intake of turmeric estimated from consumption amount of curcumin-containing foods according to the calculation described in Table 4.

2) Mean intake of curcumin estimated by the average of curcumin contents analzyed from various commercial turmeric [22].

3) Mean intake of curcumin estimated in the range of the highest and lowest curcumin content from various commercial turmeric [22].

DISCUSSION

Curcumin is a polyphenolic compound found in the spice turmeric. Curcuminoids including curcumin in turmeric gives curry its distinctive yellow color and flavor. Turmeric and its active component curcumin have received considerable attention due to the many recognized biological activities including anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and lipid-lowering effects [8,9,23]. Turmeric is largely produced in India and used extensively in South Asia as a spice and coloring agent in South Asian cuisine [23]. In those countries, the estimated consumption of turmeric is about 1-2 g/day or higher [23]. Curcumin consumption has not yet been estimated in Korea. A major food source of curcumin in the Korean diet might be curry. Although the usage of curcumin in food preparation is limited in Korea, curry is a popular one-dish meal prepared at homes and often served at schools and workplaces as lunch. Therefore, the consumption of curcumin might be higher than expected. This study utilized the combined data sets obtained from the KNHANES conducted from 2008 to 2012 in order to estimate the mean curcumin intake in Korea.

The demographic and eating behavioral characteristics of individuals who consumed curcumin seemed to reflect the fact that the major curcumin food source in the Korean diet is curry. In Korea, curry is typically prepared with commercial curry powders. Moreover, pre-made curry that is ready to serve on rice after heating is available with a wide selection for convenience. Consumption of ready-made curry was over 36% in frequency (Table 2), contributing to the high curcumin consumption from processed foods. In addition, due to the convenience in preparing curry at home and schools or workplaces for lunch meals, curcumin consumption occurred more frequently at homes, schools, and workplaces (Table 1). Curcumin was more frequently consumed by individuals who lived in urban areas, probably because curry preparation utilizes commercial ingredients that make food preparation easier upon purchase and because it is frequently included in meal menus offered at schools and workplaces. The latter might also lead to lowering the average age of individuals who consumed curcumin (Table 1). It is unclear why curcumin consumption occurred more frequently at non-apartment residences. Many different types of restaurants might be available for purchasing food near high-rise apartment complexes in Korea. The curry restaurant is less common in Korea and less than 7% of curcumin was consumed at restaurants (Table 1).

Curry consumption could be divided by the different types of curry consumed. Mean consumption in curcumin consumers was about 13 and 213 g per day for curry powder and ready-made curry, respectively, in all age groups except the youngest (< 10 years) and the oldest (≥ 70 years) groups, which may have smaller portion sizes (Table 2). Ready-made curry was consumed at its approximate serving size, whereas curry powder intake was less than its serving size (about 20 g), probably because prepared curry might also be consumed as a side dish rather than a one-dish meal, and/or because curry powder might also be used for preparing other dishes such as fried chicken and fried rice.

The average curry powder intake was about 16.4 g, which corresponds to 8.2-95.0 mg curcumin based on the reported curcumin amount in curry powder among individuals who consumed curcumin (Table 5). The estimated mean turmeric intake was about 0.47 g, equivalent to the mean curcumin intake of 2.7-14.8 mg in reference to the curcumin content in turmeric (Table 6), although it might be underestimated due to possible misclassification of curry products with unknown commercial names. There are other possibilities that curcumin consumption might be underestimated in this study. The consumption of turmeric, a major curcumin-containing food, was not considered in this study due to the absence of a separate code for turmeric. It was observed that turmeric (classified into ginger) was very rarely consumed as described in the Subjects and Methods section. It is also possible that participants may be unaware that they consumed curry powder and did not report the consumption because they were not involved in food preparation.

The curcumin content of turmeric could vary depending on the Curcuma strains [24] and purity of the turmeric [22]. Commercial curry powders may contain curcumin in an even greater variation due to varying amounts of other ingredients such as flour and oil in curry powders. Curry products manufactured in Korea might contain more thickening agents such as flour to more easily serve over rice, and this might lower the curcumin content in curry powder. Therefore, it might be more reasonable to estimate the mean intake of curcumin using the curcumin content in the turmeric.

Clinical studies indicate that high amounts of curcumin (0.5-8 g/day depending on diseases to be treated or prevented) are required for its biological activity due to its low bioavailability [14,15,16,17,18]. Thus, the curcumin consumption level (2.7-14.8 mg/day) in the Korean population might not be significant enough to exert any of the biological effects of curcumin. It should be also noted that curry is not usually consumed on a daily basis in Korea. However, it is encouraging that frequent curry consumption (occasionally and often or very often) was associated with high Mini-Mental State Examination scores in elderly Asians [11]. In addition, those who consumed curry once monthly had better respiratory health compared to subjects who never or rarely consumed curry in Singaporeans aged 55 and over [12]. Therefore, studies suggested a potential beneficial effect with ordinary curry meals especially in the elderly, characterized by a high prevalence of many chronic diseases. However these results cannot be compared in this study because the frequency of curry consumption was not assessed in the KNHANES.

In summary, curcumin-containing foods consumed by Koreans were primarily curry powder and ready-made curry. Although in a given day, very few Koreans consumed foods that contain curcumin, the average daily consumption of curcumin-containing foods was high among individuals who consumed curcumin at about 16.4 g of curry powder or 0.47 g of turmeric, which corresponds to 2.7-14.8 mg curcumin.

References

- 1.Ammon HP, Wahl MA. Pharmacology of Curcuma longa. Planta Med. 1991;57:1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagad AS, Joseph JA, Bhaskaran N, Agarwal A. Comparative evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of curcuminoids, turmerones, and aqueous extract of curcuma longa. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2013;2013:805756. doi: 10.1155/2013/805756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guimarães MR, Leite FR, Spolidorio LC, Kirkwood KL, Rossa C., Jr Curcumin abrogates LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Evidence for novel mechanisms involving SOCS-1, -3 and p38 MAPK. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58:1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu GX, Lin H, Lian QQ, Zhou SH, Guo J, Zhou HY, Chu Y, Ge RS. Curcumin as a potent and selective inhibitor of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1: improving lipid profiles in high-fat-diet-treated rats. PLoS One. 2013;8:e49976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon Y, Malik M, Magnuson BA. Inhibition of colonic aberrant crypt foci by curcumin in rats is affected by age. Nutr Cancer. 2004;48:37–43. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc4801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peschel D, Koerting R, Nass N. Curcumin induces changes in expression of genes involved in cholesterol homeostasis. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zingg JM, Hasan ST, Meydani M. Molecular mechanisms of hypolipidemic effects of curcumin. Biofactors. 2013;39:101–121. doi: 10.1002/biof.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta SC, Patchva S, Aggarwal BB. Therapeutic roles of curcumin: lessons learned from clinical trials. AAPS J. 2013;15:195–218. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9432-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatcher H, Planalp R, Cho J, Torti FM, Torti SV. Curcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1631–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra S, Palanivelu K. The effect of curcumin (turmeric) on Alzheimer's disease: an overview. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2008;11:13–19. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.40220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng TP, Chiam PC, Lee T, Chua HC, Lim L, Kua EH. Curry consumption and cognitive function in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:898–906. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng TP, Niti M, Yap KB, Tan WC. Curcumins-rich curry diet and pulmonary function in Asian older adults. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugawara J, Akazawa N, Miyaki A, Choi Y, Tanabe Y, Imai T, Maeda S. Effect of endurance exercise training and curcumin intake on central arterial hemodynamics in postmenopausal women: pilot study. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:651–656. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll RE, Benya RV, Turgeon DK, Vareed S, Neuman M, Rodriguez L, Kakarala M, Carpenter PM, McLaren C, Meyskens FL, Jr, Brenner DE. Phase IIa clinical trial of curcumin for the prevention of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:354–364. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhillon N, Aggarwal BB, Newman RA, Wolff RA, Kunnumakkara AB, Abbruzzese JL, Ng CS, Badmaev V, Kurzrock R. Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4491–4499. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polasa K, Raghuram TC, Krishna TP, Krishnaswamy K. Effect of turmeric on urinary mutagens in smokers. Mutagenesis. 1992;7:107–109. doi: 10.1093/mutage/7.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandrasekaran CV, Sundarajan K, Edwin JR, Gururaja GM, Mundkinajeddu D, Agarwal A. Immune-stimulatory and anti-inflammatory activities of Curcuma longa extract and its polysaccharide fraction. Pharmacognosy Res. 2013;5:71–79. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.110527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahiff C, Moss AC. Curcumin for clinical and endoscopic remission in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:E66. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrucci LM, Daniel CR, Kapur K, Chadha P, Shetty H, Graubard BI, George PS, Osborne W, Yurgalevitch S, Devasenapathy N, Chatterjee N, Prabhakaran D, Gupta PC, Mathew A, Sinha R. Measurement of spices and seasonings in India: opportunities for cancer epidemiology and prevention. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1621–1629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, Chun C, Khang YH, Oh K. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:69–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixit S, Khanna SK, Das M. A simple 2-directional high-performance thin-layer chromatographic method for the simultaneous determination of curcumin, metanil yellow, and sudan dyes in turmeric, chili, and curry powders. J AOAC Int. 2008;91:1387–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tayyem RF, Heath DD, Al-Delaimy WK, Rock CL. Curcumin content of turmeric and curry powders. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:126–131. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5502_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basnet P, Skalko-Basnet N. Curcumin: an anti-inflammatory molecule from a curry spice on the path to cancer treatment. Molecules. 2011;16:4567–4598. doi: 10.3390/molecules16064567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minami M, Nishio K, Ajioka Y, Kyushima H, Shigeki K, Kinjo K, Yamada K, Nagai M, Satoh K, Sakurai Y. Identification of Curcuma plants and curcumin content level by DNA polymorphisms in the trnS-trnfM intergenic spacer in chloroplast DNA. J Nat Med. 2009;63:75–79. doi: 10.1007/s11418-008-0283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]