Abstract

Cigarette smoking is one of the most significant public health issues and the most common environmental cause of preventable cancer deaths worldwide. EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor)-targeted therapy has been used in the treatment of LC (lung cancer), mainly caused by the carcinogens in cigarette smoke, with variable success. Presence of mutations in the KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) driver oncogene may confer worse prognosis and resistance to treatment for reasons not fully understood. NQO1 (NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase), also known as DT-diaphorase, is a major regulator of oxidative stress and activator of mitomycins, compounds that have been targeted in over 600 pre-clinical trials for treatment of LC. We sequenced KRAS and investigated expression of NQO1 and five clinically relevant proteins (DNMT1, DNMT3a, ERK1/2, c-MET, and survivin) in 108 patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). NQO1, ERK1/2, DNMT1, and DNMT3a but not c-MET and survivin expression was significantly more frequent in patients with KRAS mutations than those without, suggesting the following: (1) oxidative stress may play an important role in the pathogenesis, worse prognosis, and resistance to treatment reported in NSCLC patients with KRAS mutations, (2) selecting patients based on their KRAS mutational status for future clinical trials may increase success rate, and (3) since oxidation of nucleotides also specifically induces transversion mutations, the high rate of KRAS transversions in lung cancer patients may partly be due to the increased oxidative stress in addition to the known carcinogens in cigarette smoke.

Keywords: lung cancer, non-small cell lung carcinoma, oxidative stress, KRAS, mutation, NQO1, DNA methyl transferase, ERK1/2, c-MET, survivin

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking, the main cause of lung cancer, has remained as one of the most significant public health issues [1,2]. Lung cancer is the most frequent cause of cancer deaths worldwide [3]. It comprises approximately 18.2% of all cancer deaths, causing nearly as many deaths as breast, prostate, and colon cancers combined [3]. Although EGFR-directed therapy has been used for treatment with variable success, it may be less effective in patients carrying mutations in KRAS [4].

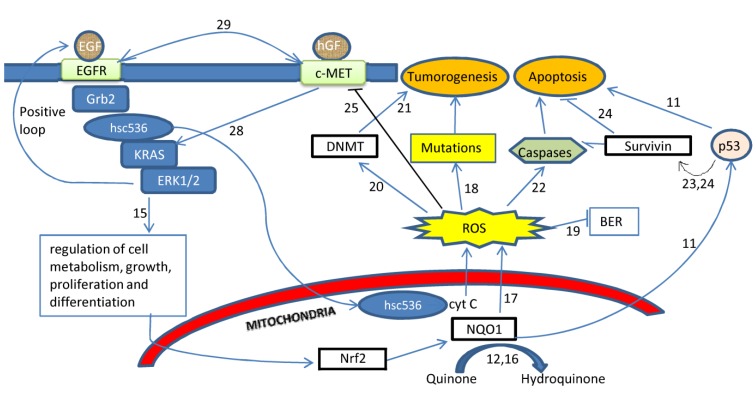

KRAS is a driver oncogene encoding for a small GTPase [5]. It activates proteins such as RAF, MEK, and ERK1/2 involved in the MAPK/ERK signal transduction pathway in response to extracellular signals received by the EGFR [6], (Figure 1). Mutations in KRAS result in the loss of its GTPase activity and constitutive activation of the downstream proteins, resulting in malignant transformation [7].

Figure 1.

Inter-relationships among oxidative stress, KRAS, NQO1, survivin, DNA methyltransferases, and c-MET in the pathogenesis of lung cancer a,b.

a See the list of references for literature cited. b Activating mutations in KRAS results in increased cellular growth, metabolism, and proliferation [15]. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced during metabolic processes are normally converted into harmless products by antioxidant enzymes such as NQO1 [12,16] which stabilizes the tumor suppressor TP53 [11]. However, when the capacity of NQO1 and other antioxidant enzymes is overwhelmed, the ROS may “leak out” of the mitochondria [17] and oxidize DNA bases, creating mutations [18]. Oxidative stress may repress base excision repair systems, which may result in additional mutations [19]. ROS may increase DNA methyl transferase activity [20], which may be an early event in lung carcinogenesis [21]. ROS regulate apoptosis via upregulation of caspases [22]. Survivin, a caspase inhibitor, also regulated by DNMTs and TP53, may decrease effects of ROS by inhibiting apoptosis [23,24]. Oxidative stress inhibits expression of c-MET, an oncogene altered in many cancers [25,26,27]. c-MET regulates oncogenic transformation of the lung cancers associated with KRAS mutations [28]. Co-activation of c-MET and EGFR is seen in a subset of lung cancers with distinct expression profile, mutational spectrum, and response to chemotherapy [29].

An interesting feature of the KRAS mutations in smokers is the high incidence of G:C > A:T transversions [8]. Previous studies have shown that NNK (4-(N-Methyl-N-nitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone), the carcinogen found in cigarette smoke, is one of the causes of these transversion mutations [9]. Interestingly, DNA replication involving 8-OHdG, the product of oxidation of guanosine, also produces the G:C > A:T transversion mutations [10]. Increased transversion rates in smokers, thus, may not only be due to the NNK but also increased oxidative stress (OS) in lung cancer cells, suggesting that there may be a link between oxidative stress and KRAS mutational status.

NQO1 (NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase, also known as DT-diaphorase) is a major regulator of oxidative stress that links oxidative stress and tumorogenesis by stabilizing the tumor suppressor TP53 [11]. Its overexpression in the tumor but not normal tissue has made it an attractive target for treatment of lung cancer [12]. NQO1 is the main activator of quinone-containing alkylating agents such as mitomycins.

To our knowledge, possible associations between NQO1 expression and KRAS mutational status have been rarely investigated in the literature. As of February 2014, entering “KRAS” and “NQO1” into the PubMed database [13] returned only one relevant study that investigated modulation of RAS (rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) mutations by NQO1 [14]. Our objective was to sequence KRAS and compare expression of NQO1 as well as a panel of five clinically relevant proteins in 108 non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), the most common form of LC, patients with and without KRAS mutations. The panel included survivin (a potent inhibitor of apoptosis), DNMT1 (the maintenance methylator of DNA), DNMT3a (the enzyme ensuring accurate inheritance of the maternal methylation patterns), ERK1/2 (downstream targets of KRAS), and c-MET (an oncogene important in the transformation of cells with KRAS mutations).

2. Results

In total, 52 of the 108 (48.1%) patients included in this study had mutations in KRAS. Of the mutations, 73.1% (38/52) were transversions and the remaining were transitions. All of the mutations originated from the guanosine nucleotide.

Average age at diagnosis was 61.0 (8.9) years (Supplemental Table S1). Male gender, smoking history, hypertension, and family cancer history were present in over half of all patients. Smoking history was present in 44 of the 48 patients (91.7%) with KRAS mutations.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) results showed that NQO1, DNMT1, DNMT3a, and ERK1/2 but not survivin and c-MET expression were more frequent in patients carrying mutations in KRAS than those carrying the wild type (Table 1). When the KRAS mutational status was ignored, expression of the following proteins was present in over half of the NSCLC patients (percentage of patients with positive expression of the protein in parenthesis): NQO1 (67.8%), survivin (75%), DNMT1 (74.6%), and c-MET (68.9%). DNMT3a and ERK1/2 expression, on the other hand, were detected in less than half of the patients (i.e., 43.3% and 46.2%, respectively).

Table 1.

Expression of NQO1 and clinically relevant proteins in non-small cell lung carcinoma patients with and without KRAS mutations.

| Protein | IHC a | KRAS Wild Type b | KRAS Mutated b | Total | P c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQO1 | Negative | 17 | 2 | 19 | <0.001 * |

| Positive | 16 | 24 | 40 | ||

| DNMT1 | Negative | 14 | 1 | 15 | <0.001 * |

| Positive | 19 | 25 | 44 | ||

| DNMT3a | Negative | 24 | 10 | 34 | 0.01 * |

| Positive | 10 | 16 | 26 | ||

| ERK1/2 | Negative | 17 | 11 | 28 | 0.002 * |

| Positive | 4 | 20 | 24 | ||

| c-MET | Negative | 5 | 9 | 14 | 0.43 |

| Positive | 15 | 16 | 31 | ||

| Survivin | Negative | 3 | 10 | 13 | 0.19 |

| Positive | 19 | 20 | 39 |

a IHC = results of the immunohistochemical staining. b Values in these columns represent numbers of patients with positive or negative immunohistochemical staining. c An asterisk “*” denotes statistical significance at P = 0.05.

3. Discussion

Despite all efforts, lung cancer has remained as the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [30,31]. The median survival rate after diagnosis of advanced-stage lung cancer is approximately 7–8 months and the average one year survival rate can be as low as 32% [32]. The reasons for these high mortality rates are probably the essential functions of the lungs, lack of reliable methods for early detection and prevention of the cancer, and the unavailability of optimized therapeutic options. Although EGFR-targeted therapy has been used with variable success, it may be less effective in patients carrying mutations in KRAS for reasons not fully understood [4,33].

KRAS is a small GTPase involved in the MAPK/ERK signal transduction pathway that regulates cell proliferation, differentiation and senescence [34,35]. Activating mutations in KRAS result in the constitutive activation of the downstream proteins and tumorogenesis [36]. KRAS mutations have been widely reported in many cancers including lung and colorectal cancers [37].

Evidence in the literature suggests that oxidative stress and KRAS mutational status may be related. The vast majority of the KRAS mutations reported in lung cancer patients are transversions. Interestingly, increased oxidative stress is also associated with increased transversion rates. Oxidative stress suppresses base excision repair (BER) mechanisms [19], which may result in incorporation of oxidized DNA nucleotides, especially guanosine, into the replicating DNA, generating transversions. We suggest that a two way relationship that may exist between the KRAS mutational status and oxidative stress may be the starting point for initiating a vicious cycle leading to malignant transformation in NSCLC.

NQO1 is an especially interesting antioxidant enzyme that may represent a direct link between oxidative stress and tumorogenesis. It not only catalyzes the two electron reduction of quinones into the hydroquinones in a reaction that prevents the production of harmful semiquinones and ROS [16,38] but also stabilizes the tumor suppressor TP53 [11]. The C609T polymorphisms in NQO1 may be a predictive factor for survival after resection of NSCLC tumors [39] and the rs1800566C/T SNP within NQO1 is linked to the deletion of EGFR exon 19 in NSCLC patients [40]. Eighty-four percent of the NQO1(-/-), but none of the control mice, exposed to gamma irradiation develop NSCLC [41].

The catalytic function of NQO1 in the reduction of quinones to hydroquinones is required for the activation of quinone-containing alkylating agents such as mitomycins, an important group of compounds used in the treatment of lung cancer for decades [12]. NQO1 expressed by the tumor cells activates the quinone-containing alkylating agents which results in the death of the cells that express NQO1. This phenomenon has been exploited to the extreme in the search for compounds for effective treatment of LC. As of 2013, over 600 pre-clinical trials targeting mitomycins have been performed but the success rate has been disappointingly low. Mitomycin C has remained as the only quinone-containing alkylating agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration for lung cancer treatment. Despite the overwhelming evidence suggesting importance of both NQO1 and KRAS in the pathogenesis of cancers, we are aware of only a single study investigating possible associations between them [14].

In our study, positive NQO1 staining was significantly more frequent in NSCLC patients with mutated than with wild type KRAS (92% vs. 48%, P <0.001). This observation raises some interesting questions. For example, why is there a stronger need for detoxification of quinones and stabilization of TP53 in NSCLC cells with the KRAS mutations than in those carrying the wild type? More importantly, could the increased NQO1 have any direct involvement in the worse prognosis and resistance to treatment seen in NSCLC patients with KRAS mutations? Further investigations are required to find definitive answers to these questions. However, the significantly more frequent expression of NQO1 in the NSCLC with KRAS mutations found in our study and the wide range of cellular events regulated by oxidative stress imply an important role for oxidative stress in the development of NSCLC with the KRAS mutations.

Another interesting result obtained in our study was the increased expression of DNMT1, the enzyme that methylates promoters of tumor suppressor genes in cancer cells, in NSCLC with KRAS mutations. Positive DNMT1 staining was seen in 57.6% of patients carrying the wild type but 96.2% of the patients with the mutated KRAS. Positive staining for DNMT1 but negative staining for DNMT3a was most frequent in NSCLC patients when the KRAS mutational status was ignored. These results are in indirect agreement with a previous study [42].

In our study, ERK1/2 expression was elevated in the NSCLC with KRAS mutations but survivin and c-MET expression did not differ between the patients with and without KRAS mutations. Survivin inhibits apoptosis by repressing caspase activity and regulating ROS production [43,44,45,46]. Its presence in tumor but not terminally differentiated cells makes it an attractive candidate for chemotherapy [47,48] and clinical trials for its therapeutic use in lung cancer are ongoing [49]. The lack of an association between KRAS mutational status and survivin expression in our study suggests that survivin-mediated apoptosis is probably not an important event in the development of the phenotype associated with KRAS mutations. When KRAS mutational status was ignored, survivin was expressed in 75% of all NSCLC tumors included in this study, a result in agreement with a previous study reporting overexpression of survivin in NSCLC [50].

In summary, we sequenced KRAS in NSCLC patients and investigated the expression of several proteins involved in oxidative stress and related events in an attempt to determine the molecular changes associated with the KRAS mutations which are known to confer worse prognosis and less favorable response to therapy. Our results suggest that increased expression of NQO1, and consequently oxidative stress, may play an important role in the development of NSCLC with KRAS mutations. Further investigations of the components of the oxidative stress systems may help in the efforts aimed at identifying molecular targets for the treatment of NSCLC with KRAS mutations. Contribution of survivin-mediated apoptosis and c-MET expression in the development of NSCLC, on the other hand, is probably not significant although further research is required to substantiate this conclusion. These results may help in a better understanding of the effects of KRAS mutations in not only NSCLC but also other types of cancers such as colorectal cancer where KRAS mutational status is a major determinant in the selection of optimal therapeutic regimes for individual patients.

4. Experimental Section

The samples included in this study were obtained from 108 NSCLC patients treated at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, OH, USA. DNA was isolated using QiaAmp Micro DNA kits from Qiagen Inc. (Valencia, CA, USA). The tissue samples resected after surgery were embedded in paraffin, fixed in formalin, and archived until analyzed. We used a semi-nested Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assay followed by direct sequencing to identify KRAS mutations in codons 12 and 13. The forward 5’-TACTGGTGGAGTATTTGATAGTG-3’ and reverse 5’-CTGTATCAAAGAATGGTCCTG-3’ primers were used in the first round of PCR. In the second round of PCR, the forward 5’-TGTAAAACGGCCAGTTAGTGTATTAACCTTATGTG-3’ and reverse 5’-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCACCTCTATTGTTGGATCATATTCG-3’ primers were used. The PCR conditions (95 °C for 15 min, 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 48 °C for 30 s, and 72 ° C for 30 s, followed by an extension step of seven minutes at 72 °C) were used in both rounds of PCR except that the annealing temperature was raised to 58 °C in the second round. Fluorescence-based capillary electrophoresis was used in an ABI3130XL genetic analyzer to detect the mutations.

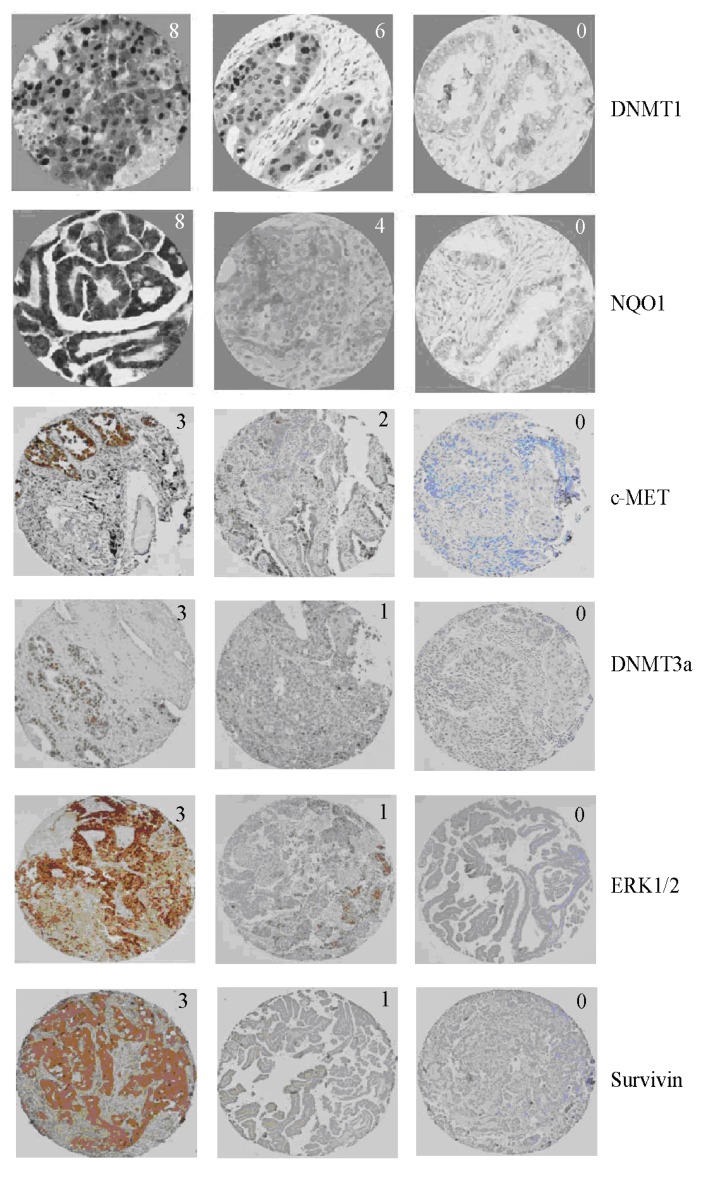

To perform IHC, tissue blocks were cut at four micron thickness and placed on positively charged slides. Slides with sections were placed in a 60 °C oven for one hour and then cooled. The samples were deparaffinized and rehydrated through two changes of O-xylene for 5 min each and 10–20 dips in graded ethanol solutions. The slides were quenched for five minutes in 3% H2O2 solution in water to block endogenous peroxidases. To perform antigen retrieval, the slides were placed in Target Retrieval Solution (Dako, CA, USA) for 25 min at 96 °C in a vegetable steamer (Black & Decker, IL, USA) and cooled for 15 min in solution. Slides were processed using a Dako Autostainer Immunostaining System following manufacturer’s instructions. Initially, slides were blocked with serum-free protein (Dako) for 15 min. The primary antibodies were diluted at proportions given in Supplemental Table S2 and incubated for one hour. Detection systems described in Supplemental Table S2 were used. Staining was visualized after incubation with DAB+ chromogen (Dako) for five minutes. The slides were then counterstained in hematoxylin, dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions and coverslipped. Representative IHC images are provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representative immunohistochemistry images of proteins with different Allred scores investigated in this study. The values on the top right corner of each image represent Allred score for that image.

IHC scores were obtained using Allred scoring system which combines the percentage of positive cells and the intensity of the reaction products in the carcinoma [51]. Proportion score has six possible values based on percentage of positive cells (in parentheses): 0 (0%), 1 (<1%), 2 (1%–10%),3 (11%–33%), 4 (34%–66%), and 5 (>67%). Intensity score has four possible values (with level of intensity in parentheses): 0 (none), 1 (weak), 2 (intermediate), and 3 (strong). The proportion and intensity scores are added to obtain the final Allred scores that range from 0 to 8. We reported samples with the final Allred scores 0, 1, and 2 as negative and those with scores 3 or higher as positive. Statistical analysis was performed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the F-test for continuous variables with the significance level set at P = 0.05.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results obtained in this study, we conclude the following: (1) increased NQO1 expression in NSCLC patients with KRAS mutations indicates that cells carrying KRAS mutations may be suffering from increased oxidative stress, (2) the increased transversion rates in NSCLC patients with KRAS mutations may partly be due to increased oxidative stress that induces transversions, and (3) since the patients with mutations may utilize quinone-containing alkylating agents more efficiently due to increased NQO1 expression, including KRAS mutational status in future clinical trials may improve success rates.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the medical staff at The Ohio State University Medical Center for providing excellent patient care and resources for conducting medical research.

Supplementary Files

Author Contributions

The authors designed the study (Weiqiang Zhao), conducted experiments and contributed materials and analysis tools (Weiqiang Zhao, Ahmet Yilmaz, Nehad Mohamed, Kara A. Patterson, Konstantin Shilo, Miguel A. Villalona-Calero, Xiaoping Zhou, Wendy Frankel, Gregory A. Otterson, Yan Tang, Howard D. Beall), analyzed and interpreted the data (Ahmet Yilmaz, Weiqiang Zhao) and wrote the manuscript (Ahmet Yilmaz, Weiqiang Zhao, Michael E. Davis, Kara A. Patterson). All authors critically read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- 1.Ezzati M., Henley S.J., Lopez A.D., Thun M.D. Role of smoking in global and regional cancer epidemiology: Current patterns and data needs. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;116:963–971. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A., Bray F., Center M.M., Ferlay J., Ward E., Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J., Shin H.R., Bray F., Forman D., Mathers C., Parkin D.M. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campos-Parra A.D., Zuloaga C., Manríquez M.E., Avilés A., Borbolla-Escoboza J., Cardona A., Meneses A., Arrieta O. KRAS mutation as the biomarker of response to chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Clues for its potential use in second-line therapy decision making. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318287bb23. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karachaliou N., Mayo C., Costa C., Magrí I., Gimenez-Capitan A., Molina-Vila M.A., Rosell R. KRAS mutations in lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2013;14:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts P.J., Der C.J. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;14:3291–3310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell S.L., Khosravi-Far R., Rossman K.L., Clark G.J., Der C.J. Increasing complexity of Ras signaling. Oncogene. 1998;17:1395–1413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noda N., Matsuzoe D., Konno T., Kawahara K., Yamashita Y., Shirakusa T. K-Ras gene mutations in non-small cell lung cancer in Japanese. Oncol. Rep. 2001;8:889–892. doi: 10.3892/or.8.4.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronai Z.A., Gradia S., Peterson L.A., Hecht S.S. G to A transitions and G to T transversions in codon 12 of the Ki-Ras oncogene isolated from mouse lung tumors induced by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and related DNA methylating and pyridyloxobutylating agents. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:2419–2422. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.11.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng K.C., Cahill D.S., Kasai H., Nishimura S., Loeb L.A. 8-Hydroxyguanine, an abundant form of oxidative DNA damage, causes G-T and A-C substitutions. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asher G., Lotem J., Kama R., Sachs L., Shaul L. NQO1 stabilizes p53 through a distinct pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beall H.D., Winski S.I. Mechanisms of action of quinone-containing alkylating agents. I: NQO1-directed drug development. Front. Biosci. 2000;5:D639–D648. doi: 10.2741/Beall. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PubMed Home Page. [(accessed on 27 May 2014)]; Available online: http://www.pubmed.gov.

- 14.Andrade F.G., Furtado-Silva J.M., Gonçalves B.A., Thuler L.C.S., Barbosa T.C., Emerenciano M., Siqueira A., Pombo-de-Oliveira M.S., Brazilian collaborative study group of infant acute leukaemia RAS mutations in early age leukaemia modulated by NQO1 rs1800566 (C609T) are associated with second-hand smoking exposures. BMC Cancer. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberg F., Hamanaka R., Wheaton W.W., Weinberg S., Joseph J., Lopez M., Kalyanaraman B., Mutlu G.M., Budinger G.R.S., Chandel N.S. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:8788–8793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ralph S.J., Rodríguez-Enríquez S., Neuzil J., Saavedra E., Moreno-Sánchez R. The causes of cancer revisited: “mitochondrial malignancy” and ROS-induced oncogenic transformation—Why mitochondria are targets for cancer therapy. Mol. Aspects Med. 2010;31:145–170. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelicano H., Feng L., Zhou Y., Carew J.S., Hileman E.O., Plunkett W., Plunkett M.J., Huang J. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration: A novel strategy to enhance drug-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells by a reactive oxygen species-mediated mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37832–37839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakim I.A., Harris R., Garland L., Cordova C.A., Mikhael D.A., Chow H-H.S. Gender difference in systemic oxidative stress and antioxidant capacity in current and former heavy smokers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012;21:2193–2200. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen B., Zhong Y., Peng W., Sun Y., Hu Y.-J., Yang Y., Kong W.-J. Increased mitochondrial DNA damage and decreased base excision repair in the auditory cortex of D-galactose-induced aging rats. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011;38:3635–3642. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franco R., Schoneveld O., Georgakilas A.G., Panayiotidis M.I. Oxidative stress, DNA methylation and carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belinsky S.A., Nikula K.J., Baylin S.B., Issa J.P. Increased cytosine DNA—Methyltransferase activity is target-cell-specific and an early event in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:4045–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon H.U., Haj-Yehia A., Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis. 2000;5:415–418. doi: 10.1023/A:1009616228304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y.A., Kamarova Y., Shen K.C., Jiang Z.L., Hahn M.-J., Wang Y.L., Brooks S.C. DNA methyltransferase-3a interacts with p53 and represses p53-mediated gene expression. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005;4:1138–1143. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.10.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hervouet E., Vallette F.M., Cartron P.F. Impact of the DNA methyltransferases expression on the methylation status of apoptosis-associated genes in glioblastoma multiforme. Cell. Death Dis. 2010;1 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.7.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X., Liu Y. Suppression of HGF receptor gene expression by oxidative stress is mediated through the interplay between Sp1 and Egr-1. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F1216–F1225. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00426.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korobko I.V., Zinov’eva M.V., Allakhverdiev A.K., Zborovskaia I.B., Svwrdlov E.D. c-Met and HGF expression in non-small-cell lung carcinomas. Mol. Gen. Mikrobiol. Virusol. 2007;2:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prat M., Narsimhan R.P., Crepaldi T., Nicotra M.R., Natali P.G., Comoglio P.M. The receptor encoded by the human c-MET oncogene is expressed in hepatocytes, epithelial cells and solid tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 1991;49:323–328. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y., Wislez M., Fujimoto N., Prudkin L., Izzo J.G., Uno F., Ji L., Hanna A.E., Langley R.R., Liu D. A selective small molecule inhibitor of c-Met, PHA-665752, reverses lung premalignancy induced by mutant K-ras. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:952–960. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsubara D., Ishikawa S., Sachiko O., Aburatani H., Fukayama M., Niki T. Co-activation of epidermal growth factor receptor and c-MET defines a distinct subset of lung adenocarcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:2191–2204. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., Hao Y., Xu J.-Q., Murray T., Thun M.J. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamangar F., Dores G.M., Anderson W.F. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: Defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonomi P., Kim K., Fairclough D., Cella D., Kugler J., Rowinsky E., Jiroutek M., Johnson D. Comparison of survival and quality of life in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with two dose levels of paclitaxel combined with cisplatin versus etoposide with cisplatin: Results of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:623–631. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberhard D.A., Johnson B.E., Amler L.C., Goddard A.D., Heldens S.L., Herbst R.S., Ince W.L., Jänne P.A., Januario T., Johnson D.H. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aviel-Ronen S., Blackhall F.H., Shepherd F.A., Tsao M.S. K-ras mutations in non-small-cell lung carcinoma: A review. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2006;8:30–38. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sunaga N., Shames D.S., Girard L., Peyton M., Larsen J.E., Imai H., Soh J., Sato M., Yanagitani N., Kaira K., et al. Knockdown of oncogenic KRAS in non-small cell lung cancers suppresses tumor growth and sensitizes tumor cells to targeted therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011;10:336–346. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keller J.W., Franklin J.L., Graves-Deal R., Friedman D.B., Whitwell C.W., Coffey R.J. Oncogenic KRAS provides a uniquely powerful and variable oncogenic contribution among RAS family members in the colonic epithelium. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;210:740–749. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minamoto T., Mai M., Ronai Z. K-ras mutation: Early detection in molecular diagnosis and risk assessment of colorectal, pancreas, and lung cancers—A review. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2000;24:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel D., Kepa J.K., Ross D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) localizes to the mitotic spindle in human cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song S.Y., Jeong S.Y., Park H.J., Park S., Kim D.K., Kim Y.H., Shin S.S., Lee S.-W., Ahn S.D., Kim J.H., et al. Clinical significance of NQO1 C609T polymorphisms after postoperative radiation therapy in completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang S.Y., Yang T.Y., Li Y.J., Chen K.C., Liao K.M., Hsu K.H., Tsai C.R., Chen C.H., Hsu C.P., Hsia J.Y., et al. EGFR exon 19 in-frame deletion and polymorphisms of DNA repair genes in never-smoking female lung adenocarcinoma patients. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132:449–458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iskander K., Barrios R.J., Jaiswal A.K. Disruption of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene in mice leads to radiation-induced myeloproliferative disease. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7915–7922. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.An H.J., Lee H., Paik S.G. Silencing of BNIP3 results from promoter methylation by DNA methyltransferase 1 induced by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol. Cells. 2011;31:579–583. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0065-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamm I., Wang Y., Sausville E., Scudiero D.A., Vigna N., Oltersdorf T., Reed J.C. IAP-family protein survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5315–5320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y., Wang X., Li W., Zhang H., Zhao C., Li Y., Wang Z., Chen C. Sp1 upregulates survivin expression in adenocarcinoma of lung cell line A549. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 2011;294:774–780. doi: 10.1002/ar.21378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaikwad A., Long D.J., 2nd, Stringer J.L., Jaiswal A.K. In vivo role of NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in the regulation of intracellular redox state and accumulation of abdominal adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:22559–22564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu J., Wu S., Xing D. Survivin mediates self-protection through ROS/cdc25c/CDK1 signaling pathway during tumor cell apoptosis induced by high fluence low-power laser irradiation. Cancer Lett. 2010;297:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ambrosini G., Adida C., Altieri D.C. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat. Med. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altieri D.C. Validating survivin as a cancer therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:46–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryan B.M., O’Donovan N., Duffy M.J. Survivin: A new target for anti-cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2009;35:553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han P.H., Li X.J., Qin H., Yao J., Du N., Ren H. Upregulation of survivin in non-small cell lung cancer and its clinicopathological correlation with p53 and Bcl-2 (In Chinese) Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue. Za. Zhi. 2009;25:710–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allred D.C., Harvey J.M., Berardo M., Clark G.M. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod. Pathol. 1998;11:155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.