Abstract

Large-conductance voltage and Ca2+-activated potassium channels (BKCa) play a critical role in modulating contractile tone of smooth muscle, and neuronal processes. In most mammalian tissues, activation of β-adrenergic receptors and protein kinase A (PKAc) increases BKCa channel activity, contributing to sympathetic nervous system/hormonal regulation of membrane excitability. Here we report the requirement of an association of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) with the pore forming α subunit of BKCa and an A-kinase-anchoring protein (AKAP79/150) for β2 agonist regulation. β2AR can simultaneously interact with both BKCa and L-type Ca2+ channels (Cav1.2) in vivo, which enables the assembly of a unique, highly localized signal transduction complex to mediate Ca2+- and phosphorylation-dependent modulation of BKCa current. Our findings reveal a novel function for G protein-coupled receptors as a scaffold to couple two families of ion channels into a physical and functional signaling complex to modulate β-adrenergic regulation of membrane excitability.

Keywords: BKCa, β2AR, kinase, macromolecular complex, phosphorylation

Introduction

Large-conductance voltage and Ca2+-activated potassium channels (BKCa), encoded by the gene Slo1 (Butler et al, 1993), are regulated extensively by alternative splicing (Lagrutta et al, 1994), phosphorylation/dephosphorylation (Chung et al, 1991) and associated regulatory proteins such as β subunits (Brenner et al, 2000). BKCa/Slo channels are activated by depolarization and elevated cytosolic Ca2+. In neurons, BKCa channels have been localized to cell bodies and nerve terminals (Knaus et al, 1996) and can functionally colocalize with Ca2+ channels at presynaptic terminals (Robitaille et al, 1993). In neurons, the channels underlie the fast after-hyperpolarization that contributes to resetting the membrane potential during an action potential (Storm, 1987). In presynaptic terminals, the channels are believed to influence synaptic transmission by hyperpolarizing the plasma membrane, thereby limiting Ca2+ influx (Storm, 1987; Lancaster et al, 1991; Robitaille et al, 1993; Joiner et al, 1998). In smooth muscle, BKCa channels hyperpolarize the membrane, thereby indirectly reducing contractility (Nelson et al, 1995). The direct regulation of BKCa mediates, in part, the bronchorelaxant and vasorelaxant properties of β agonists (Schubert and Nelson, 2001; Pelaia et al, 2002).

An emerging concept in ion channel regulation is that modulation by phosphorylation is controlled by local signaling mechanisms (Marx et al, 2000, 2001; Davare et al, 2001). BKCa channels are potently modulated by reversible protein phosphorylation (Chung et al, 1991; Reinhart et al, 1991; Schubert et al, 1999; Schubert and Nelson, 2001; Zhou et al, 2001). Prior studies have established that BKCa is a substrate of protein kinase A (PKAc) (Sadoshima et al, 1988; Kume et al, 1989; Nara et al, 1998) that can activate or inhibit channel activity, depending on the splice isoform (Carl et al, 1991; Tian et al, 2001; Fury et al, 2002). BKCa channels are also phosphorylated by protein kinase C (PKC) (Minami et al, 1993; Zhou et al, 2001) and protein kinase G (PKG) (Kume et al, 1992; Alioua et al, 1998) at distinct sites (Zhou et al, 2001). To add to the complexity of regulation, cross-activation of PKG by cAMP-dependent vasodilators has been described (White et al, 2000; Barman et al, 2003). Although several studies have suggested that kinase(s) is/are tethered to the BKCa channel (Chung et al, 1991; Wang et al, 1999; Tian et al, 2003), the macromolecular complex that facilitates β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) signaling to the BKCa channel has not been clearly elucidated. We identified the requirement of an association between the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), A-kinase-anchoring protein (AKAP79/150) and BKCa channel to enhance β2 agonist regulation of the channel. Moreover, as β2ARs can dimerize (Angers et al, 2000) and simultaneously interact with both BKCa and L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCC) (Davare et al, 2001), a functional macromolecular signaling complex is created that permits the rapid response to β2 agonist.

Results

PKAc interacts with BKCa channel

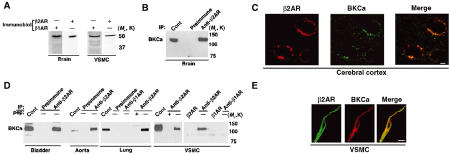

BKCa channels, immunoprecipitated from brain extract, were phosphorylated in vitro by PKAc, which was inhibited by the addition of a PKA inhibitor, PKI5–24 (Figure 1A). BKCa immunoprecipitated from brain is also phosphorylated in the presence of cAMP, in the absence of exogenous PKAc. The phosphorylation induced by cAMP is inhibited by PKI, suggesting that BKCa is closely associated in vivo with an endogenous PKAc (Figure 1B) (Chung et al, 1991; Esguerra et al, 1994). This endogenous kinase bound to the channel is inactive, as the BKCa channel immunoprecipitated by brain was not phosphorylated with the exclusion of cAMP (Figure 1A). PKAc can be completely dissociated from the BKCa complex by cAMP (Figure 1C), indicating that the catalytic subunit engages the complex through a regulatory subunit (holoenzyme), rather than via a distinct site on the catalytic subunit, as is the case for PKAc and Drosophila BKCa (dSlo) interaction (Zhou et al, 2002). When cAMP was not preincubated with the immunoprecipitates prior to in vitro phosphorylation, a strong phosphorylation signal is detected (Figure 1C). These data suggest that BKCa is part of a macromolecular complex that underlies the regulation of the channel by β2AR signaling/processes that elevate intracellular cAMP.

Figure 1.

BKCa channel is phosphorylated by associated PKA. (A) Autoradiograph (left) of BKCa channel immunoprecipitated from brain incubated with the catalytic subunit of PKA (PKAc) and [γ-32P]ATP and size-fractionated on SDS–8% PAGE; the specificity was established using preimmune serum and PKA inhibitor, PKI5–24. Immunoblot (right) of immunoprecipitation (IP) of BKCa channel from brain extract size-fractionated on SDS–10% PAGE, demonstrating specificity of antibody. ‘cont' represents 5% of input, ‘HC' represents the heavy chain of IgG BKCa channel is specifically phosphorylated by exogenous PKA. (B) Autoradiograph of BKCa immunoprecipitated from brain incubated with PKAc or cAMP±PKI. cAMP activates an associated, endogenous kinase that is inhibited by PKI, indicating that PKAc is associated with the channel complex. (C) Autoradiograph of BKCa immunoprecipitated from brain, initially preincubated with 5 μM cAMP (without Mg-ATP, which is not permissive for phosphorylation of the channel), followed by in vitro phosphorylation initiated by cAMP and [γ-32P]ATP/Mg-ATP. Preincubation with cAMP releases the associated PKAc from the BKCa macromolecular complex, as indicated by the reduction of cAMP-induced phosphorylation in the pretreated lane (+).

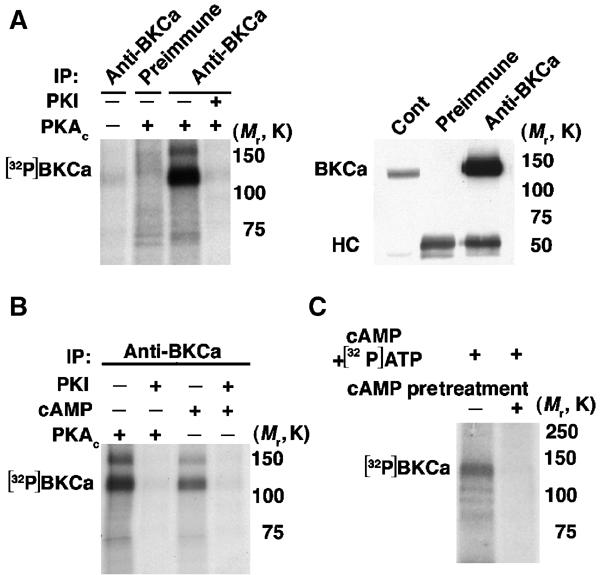

β2AR associates with neuronal and smooth muscle BKCa channel

Given the importance of adrenergic input for regulating membrane excitability and BKCa function, we sought to determine whether BKCa associates with β-ARs. Although both β1AR and β2AR are expressed in the brain (Figure 2A), β2AR, but not β1AR (data not shown), is associated with BKCa (Figure 2B). BKCa colocalized/distributed with β2AR in the soma of mouse brain cortical neurons (Figure 2C) and in cerebellar Purkinje cells, and in basket and stellate cells in the molecular layer of the cerebellum (data not shown).

Figure 2.

β2AR is associated with BKCa channel in brain and smooth muscle. (A) β2AR and β1AR immunoblot of brain and VSMC lysates. (B) BKCa immunoblot of β2AR and preimmune immunoprecipitations from rat brain. BKCa specifically associates with β2AR. (C) Representative confocal images of immunostaining of mouse cerebral cortex for β2AR (red) and BKCa (green). BKCa and β2AR are colocalized/distributed (merged image) on the soma of the cortical neuron. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) BKCa immunoblots of β2AR immunoprecipitations from extracts of rat bladder and aorta, human lung (lymphangiomyomatosis) and VSMCs. Immunoprecipitation specificity was demonstrated using β1AR and β2AR antibody without lysate (in VSMC samples), preimmune serum or β2AR peptide-blocked antibody (+pep) in lung and VSMC samples. β2AR specifically co-immunoprecipitates with BKCa channels. ‘cont' is 5% input. (E) Representative confocal images of immunostaining for β2AR (green) and BKCa (red) in isolated human VSMCs. BKCa and β2AR are colocalized/distributed (merged images). Scale bar, 10 μm.

BKCa channels play a significant role in the regulation of vascular (Brenner et al, 2000), pulmonary (Pelaia et al, 2002) and uterine (Wallner et al, 1995) smooth muscle contraction, and modulation of BKCa by β-ARs represents an important therapeutic target. Immunoprecipitation of β2AR from extracts of tissues enriched in smooth muscle such as bladder, aorta and lung (Figure 2D) demonstrated a specific association with BKCa channels. Negative controls included β1AR and β2AR antibody alone (without lysate), preimmune serum (with lysate) and peptide-blocked β2AR antibody (with lysate). As the regulation of arterial tone is dependent on vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) contractility, we sought to determine whether the complex was present in isolated VSMCs. Consistent with this role, the association of β2AR and BKCa was present in VSMC as demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 2D) and confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 2E). The interaction was specific, as the β1AR, although expressed in vascular smooth muscle and lung as determined by immunoblot (Figure 2A and data not shown), was not associated with the channel (Figure 2D).

Formation of BKCa–β2AR–AKAP79/150 complex

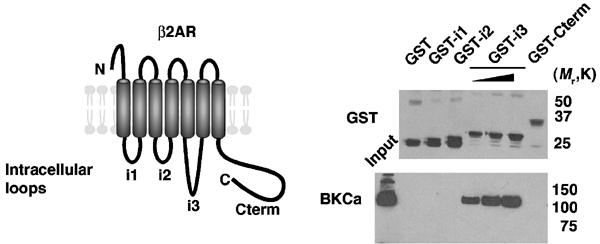

To examine the binding determinants for BKCa on β2AR, glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins of the β2AR intracellular loops were prepared and assayed for their ability to interact with BKCa in brain extracts. Mapping of the interaction sites revealed that only the third intracellular (i3) loop associated with the channel (Figure 3). GST fusion proteins containing the other intracellular domains (i1, i2 and C-terminus) failed to co-precipitate the channel.

Figure 3.

Specific interaction of the β2AR third intracellular loop and BKCa channel. Representation (left) of β2AR; GST fusion proteins were prepared for the three intracellular loops (i1–i3) and the C-terminus (Cterm). Rat brain extracts were incubated with the GST fusion proteins bound to glutathione sepharose. For GST-i3, pull-downs were performed with increasing amounts of GST fusion proteins to demonstrate specificity of interaction. After extensive washing, samples were size-fractionated on SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Immunoblots (right; upper GST antibody, lower BKCa antibody) demonstrate that only GST-i3 specifically co-precipitated BKCa channel.

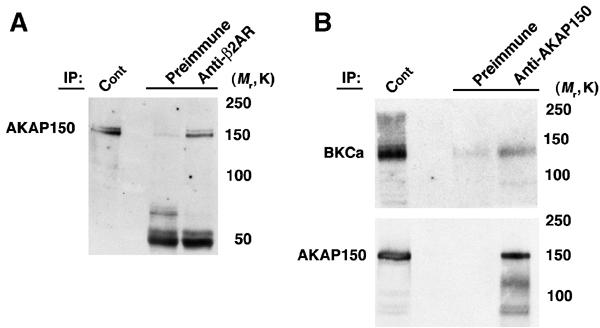

Prior studies have demonstrated that AKAP79/150 (Fraser et al, 2000) and gravin bind to β2AR (Shih et al, 1999; Tao et al, 2003). β2AR can co-immunoprecipitate AKAP150, the rodent homolog of AKAP79 from rat brain lysates (Figure 4A). We hypothesized that the BKCa–β2AR complex might recruit an AKAP due to the constitutive binding of an AKAP to β2AR (Shih et al, 1999; Fraser et al, 2000). In rat brain lysates, AKAP150 could be co-immunoprecipitated with BKCa (Figure 4B), indicating that a BKCa–β2AR–AKAP150 complex exists in native tissue.

Figure 4.

AKAP150 is associated with β2AR and BKCa channels in brain. (A) AKAP150 immunoblot of immunoprecipitation using β2AR antibody or preimmune serum from rat brain lysates. β2AR specifically associates with AKAP150. (B) BKCa (upper) and AKAP150 (lower) immunoblot of immunoprecipitation using AKAP150 antibody or preimmune serum from rat brain lysates. AKAP150 specifically associates with BKCa.

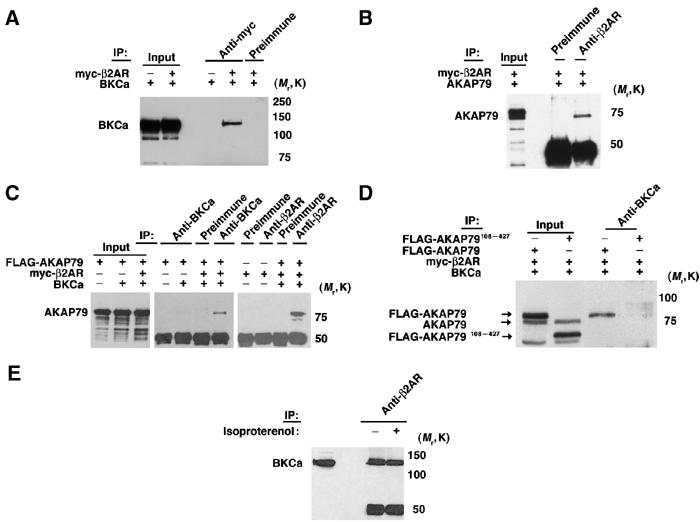

The β2AR–BKCa interaction can be reconstituted in HEK293 cells after expression of both myc-β2AR and BKCa (Figure 5A). β2AR constitutively recruits AKAP79 (Fraser et al, 2000) (Figure 5B), which enables the targeting of AKAP79 to the channel (Figure 5C). Without expression of β2AR, AKAP79 cannot associate with BKCa (Figure 5C), demonstrating the requirement for AKAP79 binding to β2AR in order to assemble the AKAP79–BKCa complex. Overexpression of AKAP79 is not required for β2AR–BKCa interaction (Figure 5A). Likewise, overexpression of BKCa is not required for β2AR–AKAP79 association (Figure 5B). The binding of both AKAP79 and BKCa to β2AR (Figure 5C) is not mutually exclusive, consistent with the findings that BKCa associate with β2AR via the third intracellular loop (i3; Figure 3) and AKAP79 associates with β2AR via the third intracellular loop and the C-terminus independently (Fraser et al, 2000). A mutant AKAP79 (FLAG-AKAP79108–427) that can bind RII and PKA, but cannot associate with β2AR (Fraser et al, 2000), was not recruited into the BKCa complex (Figure 5D). The coupling of β2AR and BKCa was constitutive, as it was not modulated by exposure to isoproterenol (Figure 5E). Collectively, these findings suggest that a functional consequence of β2AR targeting to BKCa may be the facilitation of cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of BKCa by an anchored pool of PKA holoenzyme.

Figure 5.

β2AR and AKAP79 associate with BKCa channel in HEK293 cells (A) BKCa immunoblot of immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-myc and preimmune serum from extracts of HEK293 cells overexpressing myc-β2AR and BKCa. β2AR–BKCa association can be reconstituted in HEK293 cells. (B) AKAP79 immunoblot of immunoprecipitation using β2AR antibody and preimmune serum of HEK293 cells overexpressing myc-β2AR and AKAP79. β2AR specifically associates with AKAP79. (C) Coexpression of BKCa, β2AR and AKAP79 (as indicated) in HEK; lysates were immunoprecipitated with preimmune serum, BKCa or β2AR antibodies and blotted with AKAP79 antibody. AKAP79 associates with BKCa, only in cells coexpressing BKCa/β2AR/AKAP79. (D) AKAP79 immunoblot of BKCa immunoprecipitations of extracts from HEK293 cells expressing BKCa/β2AR and either AKAP79 or AKAP79108–427 (not targeted to β2AR). The inability of the truncated AKAP79 to bind to β2AR prevents the assembly of a BKCa–AKAP79 complex. (E) BKCa immunoblot of β2AR immunoprecipitations of β2AR/BKCa-HEK293 cells exposed to isoproterenol. β2AR–BKCa associate in a β-agonist-independent manner.

Macromolecular signaling complex enhances β2 agonist activation of BKCa

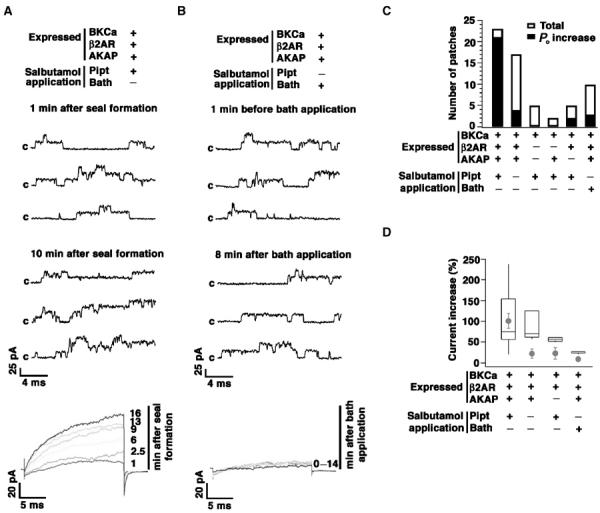

To explore the functional implications of β2AR–BKCa, we coexpressed BKCa, β2AR and AKAP79 in Xenopus oocytes. We recorded channel activity using cell-attached patch clamp and applied a specific β2 agonist, salbutamol (20 μM), either in the recording pipette by back-filling or in the bath solution (20–40 μM) (Chen-Izu et al, 2000). The inclusion of a β2 agonist in the patch pipette increased channel activity over ∼10 min (Figure 6A), consistent with the diffusion of the agonist within the patch pipette and activation of BKCa (P<0.0005 compared to no salbutamol by Wilcoxon's rank sum test). In contrast, channel activity did not increase with bath application of salbutamol, indicating that BKCa is preferentially regulated by β2AR within the channel macromolecular complex, as opposed to those located remotely in the cell (Figure 6B). In a total of 23 patches recorded with salbutamol in the patch pipette, channel activity increased in 21 patches (91%) (Figure 6C), whereas channel activity increased in three of 10 (30%) patches recorded with bath application of salbutamol (P<0.001 compared to salbutamol in patch pipette by Wilcoxon's rank sum test) (Figure 6C). The likelihood of channel activation with salbutamol in the patch pipette was substantially enhanced by expression of the three macromolecular components, as compared to expression of BKCa alone, BKCa+AKAP79 or BKCa+β2AR (Figure 6C). BKCa activity could be increased only when the channel was coexpressed with β2AR, indicating the lack of endogenous β2AR in Xenopus oocytes. Thus, the colocalization of β2AR and BKCa channel, along with AKAP79 is required for full functional regulation. In addition, the increase of BKCa current in the cell-attached patch was not due to an increase in Ca2+ entry into the oocyte, as the free Ca2+ concentration in pipette solution and bath solution was very low, either 0.5 nM (5 mM EGTA) or ∼10 μM (without EGTA).

Figure 6.

Localized upregulation of BKCa channels via β2AR signaling. (A, B) Representative current traces of BKCa channels coexpressed with β2AR and AKAP79 in a Xenopus oocyte. Channel activity was recorded using cell-attached patch clamp during 20 ms, +150 mV test pulses from −50 mV, and then returned to −50 mV. Salbutamol (20 μM) was applied in the patch pipette by back-filling (A) or in the bath (B). A total of 100 sweeps were applied at various times as indicated. Sweeps 10, 40 and 80 at each time are shown. ‘c' represents closed state of the channel. Average currents of all 100 sweeps are shown at the bottom at the indicated times (min) after the GΩ seal formation (A) or bath application of salbutamol (B). (C) Total number of patches that have been recorded versus the number of patches in which an increased open probability of BKCa (Po increase >10%) was observed. Inclusion of salbutamol in the patch pipette significantly increased the number of patches which demonstrated Po increase as compared to bath application. Increased BKCa channel Po was dependent on coexpression of β2AR–AKAP79. (D) Graph of data set summarizing average currents of all 100 sweeps 15 min after salbutamol application. In the box plot, patches without Po increase are excluded. In each box, the mid-line shows the median value, the top and bottom lines show the 75th and 25th percentiles, and the whiskers show the 90th and 10th percentiles. The circles are means of data, including patches without Po increase, and error bars are standard error of means. For experiments on coexpression of BKCa, β2AR and AKAP, the P-value of Wilcoxon's rank sum test <0.0005 between pipette application of salbutamol and no salbutamol (left two circles), and <0.001 between pipette application and bath application of salbutamol (left and right circles).

The magnitude of current increase (%) varied extensively (Figure 6D; box plot), an effect that may be due to the variable expression efficiency and/or the time between back-filling the agonist and the formation of the gigaseal. However, the magnitude of current increase was significantly smaller with bath application than that caused by agonist in the patch pipette (Figure 6D; box plot). Although channel activity increased in response to pipette salbutamol in two of five patches (40%) when AKAP79 was not coexpressed, the magnitude of current increase was less than when three components were expressed (Figure 6C and D). These findings suggest that expression of AKAP79 increases the likelihood of salbutamol-mediated modulation (Figure 6C and D). Xenopus oocytes may contain an endogenous AKAP or, alternatively, signaling pathways other than the AKAP-mediated pathway may contribute to the modulation of BKCa. Overall, only expression of all three components of the complex reconstituted full-β2 agonist modulation of the channel (Figure 6D; circles).

LTCC associate with BKCa channel through β2AR-dependent scaffold

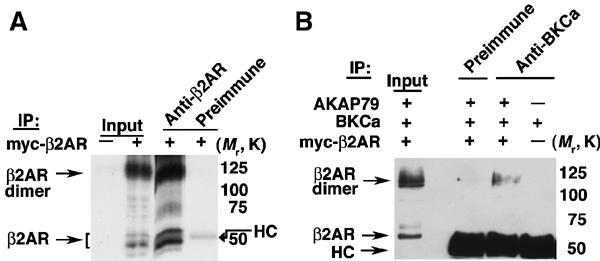

β2ARs in native tissue and expressed in HEK293 cells form SDS-resistant dimers (Figure 7A) (Angers et al, 2000; Salahpour et al, 2003), which associate with BKCa (Figure 7B). Although, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are thought to function independently as monomers to signal to effector molecules, recent studies have suggested that oligomerization (dimerization) of GPCRs in vivo is a constitutive process, dependent on disulfide bonds and hydrophobic packing (Salahpour et al, 2003), that provides an additional level of functional complexity for their responses (Barki-Harrington et al, 2003). Our findings of β2AR dimerization are consistent with prior reports, although the extent of dimerization seen on SDS–PAGE may not correlate with the extent of dimerization in situ.

Figure 7.

BKCa channel associates with β2AR dimers. (A) myc immunoblot of β2AR immunoprecipitations from HEK293 cells overexpressing myc-β2AR. The lower molecular form represents the expressed monomeric β2AR, while the higher species represents SDS-resistant β2AR dimers. β2AR antibody specifically immunoprecipitates expressed myc-β2AR. (B) myc immunoblot of BKCa immunoprecipitation from HEK293 cells expressing the indicated constructs. BKCa channels associate with β2AR dimers (the monomer species is obscured by the heavy chain of Ig (HC).

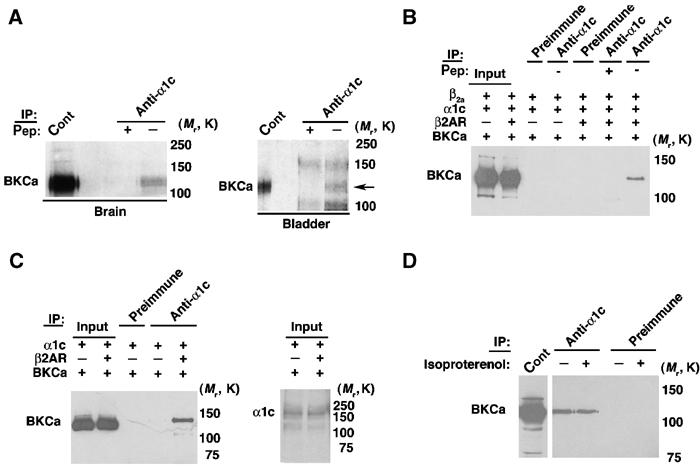

As the β2AR can dimerize and associate with BKCa (Figure 7B) and LTCC (Davare et al, 2001), we hypothesized that β2AR might act as a scaffold that not only facilitates cAMP-mediated regulation of the channels but also recruits both ion channels into a macromolecular complex. Despite the observations that Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) can activate BKCa (Roberts et al, 1990; Gola and Crest, 1993; Nelson et al, 1995; Marrion and Tavalin, 1998; Herrera and Nelson, 2002; Sun et al, 2003), a physical association between the ion channels has not been demonstrated. Immunoprecipitation of LTCC from brain and bladder extract revealed that the channel was part of the BKCa complex (Figure 8A). The association was specific, as the co-immunoprecipitation could be blocked by preabsorption of the antibody with α1c peptide (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

β2AR mediates physical colocalization of BKCa and LTCC. (A) BKCa immunoblots of α1c immunoprecipitations from brain and bladder lysates. BKCa (arrow) co-precipitates with α1c (LTCC). Immunoprecipitation specificity was demonstrated using preimmune serum and peptide-blocked antibody (+pep). (B) BKCa immunoblot of α1c immunoprecipitations from HEK293 cells expressing BKCa/β2AR/α1c/β2A. BKCa co-immunoprecipitates with α1c in HEK293 cells coexpressing β2AR. (C) BKCa (left) and α1c/LTCC (right) immunoblot of α1c immunoprecipitates from HEK cells expressing BKCa/β2AR/α1c. BKCa co-precipitates with α1c in a β2a subunit-independent manner. Equivalent expression of α1c in HEK cells is shown (right). (D) BKCa immunoblot of α1c immunoprecipitation of HEK293 cells coexpressing β2AR/BKCa/α1c without β2a subunit. Cells were treated with isoproterenol. α1c-BKCa channels associate in a β-agonist-independent manner.

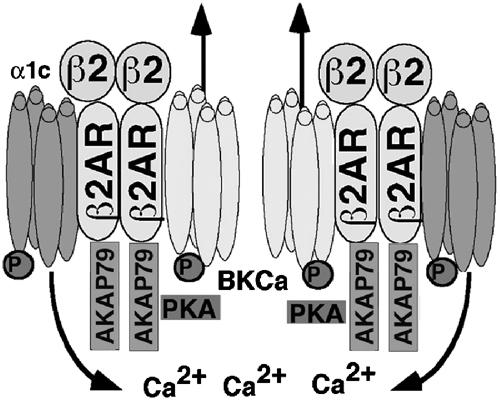

We next examined whether β2AR was required for the assembly of the BKCa–LTCC complex. Coexpression of BKCa, β2AR, and LTCC α1c/β2a subunits reconstituted the association (Figure 8B). The co-immunoprecipitation was blocked by α1c peptide (Figure 8B). The interaction was dependent on β2AR expression because the association was not present in HEK293 cells coexpressing only BKCa and α1c/β2a (Figure 8B). These findings indicate that the assembly of the BKCa–LTCC (α1c+β2a) complex was dependent on β2AR expression. To examine the role of the LTCC β subunit in the assembly of the complex, we coexpressed β2AR, BKCa and α1c in HEK293 cells. The assembly of the BKCa–LTCC complex was dependent on β2AR expression, but not β2a subunit expression (Figure 8C). Exposure of HEK293 cells expressing β2AR, LTCC and BKCa channel to a β agonist (isoproterenol) did not affect the association of BKCa and LTCC (Figure 8D). These findings indicate a novel function for β2AR as a scaffold to permit the physical association of two families of ion channels, which have been previously reported to couple functionally (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Molecular model of macromolecular complex depicting the physical and functional regulation of the BKCa channel by β2AR/AKAP79 and α1c. Activation of β2AR by β2 agonist leads to phosphorylation of both BKCa and LTCC, resulting in increased BKCa channel activity.

Discussion

The present study offers a molecular identification of a mechanism through which BKCa channel activity is specifically regulated by β2AR signaling in brain and smooth muscle. The ability of β2AR to form a complex with BKCa, and concomitantly bind phosphorylation-modulatory components (AKAP79/150) enables specific and local regulation of BKCa channels and defines a signal transduction pathway governing cellular excitability in diverse tissues. The findings also reveal a physiologically important and unanticipated role of β2AR: that of serving as a nonphosphorylation-dependent scaffold to enable regulation of BKCa channels by LTCC.

A common theme in signal transduction is the close association of signaling molecules with effectors to enable specific and local regulation (Pawson and Scott, 1997). Specificity of PKA anchoring is achieved by targeting motifs that direct AKAPs to specific cellular sites (Pawson and Scott, 1997). AKAP79/150 has been demonstrated to interact with PKA, PKC and calcineurin (Klauck et al, 1996). The associated PKA and PKC are maintained in an inactive state when bound to AKAP79, but can be activated by cAMP or diacylglycerol (Faux et al, 1999). AKAP79/150 associates with β2AR in brain, regulating the phosphorylation state of the receptor (Fraser et al, 2000). Our findings suggest that association of AKAP79/150 with β2AR enables the facilitation of phosphorylation of BKCa and LTCC in response to β agonists. As the BKCa channel is also regulated by PKC, it remains to be determined whether the assembly of the β2AR–BKCa–AKAP79/150 complex facilitates regulation by PKC. A recent report has suggested that PKA is targeted to the BKCa channel through leucine zipper-mediated interactions (Tian et al, 2003), similar to leucine zipper-mediated interactions described for ryanodine receptors (Marx et al, 2000, 2001), KCNQ1 (Marx et al, 2002) and Cav1.1/Cav1.2 (Hulme et al, 2002, 2003). Our findings do not preclude BKCa channel association with PKA in native tissues through additional mechanisms. Thus, the BKCa channel is actively regulated by a macromolecular complex that enables specific regulation by kinases and phosphatases (Carl et al, 1991; Reinhart and Levitan, 1995; Sansom et al, 1997; Widmer et al, 2003).

Although the role of kinases and phosphatases has been relatively well studied in numerous systems, there has been limited information regarding the effects in specific neuronal cells. PKA phosphorylation activates BKCa channels in many, but not all, cell types. In smooth muscle, most but not all studies have shown that PKA phosphorylation leads to activation of the channel (Schubert and Nelson, 2001). However, cAMP-induced activation of PKG (cross-activation) has been described, potentially leading to channel activation through PKG phosphorylation (White et al, 2000). Our findings of a β2AR–BKCa complex does not preclude the cross-activation hypothesis, but rather serves to highlight a mechanism through which generation of cAMP through activation of the closely associated β2AR can lead to modulation of BKCa channels. Moreover, adenylyl cyclase has been reported to co-purify with Gαs and Gβ subunits (Bar-Sinai et al, 1992) and colocalizes with LTCC in rabbit cardiac myocytes (Gao et al, 1997) and with the β2AR–LTCC complex in brain (Davare et al, 2001). Thus, the formation of a β2AR–BKCa complex can lead to a highly organized scaffold that facilitates cAMP-dependent phosphorylation.

Most binding sites for β2AR interacting proteins are within the third intracellular loop and C-terminus. The C-terminus has been reported to interact with the LTCC (Davare et al, 2001) and Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor (NHERF) (Hall et al, 1998). AKAP79/150, which modulates PKA phosphorylation of β2AR and GPCR kinase 2 (GRK2) (Cong et al, 2001), interacts with the β2AR third intracellular loop and C-terminus (Fraser et al, 2000). BKCa channel interacts directly with only the β2AR third intracellular loop. Unlike heterotrimeric G proteins, arrestins (Rockman et al, 2002) and NHERF (Hall et al, 1998), which bind to β2AR in an agonist-dependent manner, AKAP79/150 (Fraser et al, 2000), and BKCa bind to β2AR constitutively. Moreover, the BKCa–LTCC channel complex is not dependent on the β2AR activation state. The amino-acid sequence of the β1AR third intracellular loop markedly differs from that of β2AR, consistent with our findings that β2AR, but not β1AR, binds to BKCa in vivo (Green and Liggett, 1994).

The association of β2AR and BKCa is required to permit β2 agonist activation. The inclusion of the β2 agonist in the patch pipette significantly increased the likelihood of channel activation as compared to bath application. This finding demonstrates that BKCa channels are preferentially activated by local β2 agonist signaling. Prior studies have demonstrated that the BKCa channel can be activated by extracellular exposure to isoproterenol (a β1 and β2 agonist) (Sadoshima et al, 1988; Kume et al, 1989). This finding highlights the distinction between β1AR and β2AR stimulation in that β1 agonists can activate the channel both locally and remotely, whereas β2 agonists modulate BKCa channels only locally. Prior studies indicated that β2AR signaling leading to activation of LTCC is also highly localized in cardiac muscle and neurons, potentially due to the coupling of both Gαs and Gi to β2AR (Chen-Izu et al, 2000; Davare et al, 2001; Xiao, 2001). The likelihood of spontaneous activation of BKCa channels coexpressed with β2AR and AKAP79 (without β2 agonist in patch pipette) was similar to activation after bath application of the β2 agonist. This finding may be explained by the occurrence of spontaneous activation of β2AR (Zhou et al, 2000). The magnitude of BKCa current increase was greatest upon coexpression of β2AR and AKAP79 and activation of β2AR locally. Only coexpression of all three components of the macromolecular complex reconstituted full β2 agonist modulation.

The source of Ca2+ for activation of BKCa has been the subject of intense investigation. Several studies have suggested a functional linkage between the BKCa channel and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel and/or ryanodine receptor, although the specific subtype of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel has been variable (Roberts et al, 1990; Gola and Crest, 1993; Nelson et al, 1995; Marrion and Tavalin, 1998; Pineda et al, 1998; Herrera and Nelson, 2002; Sun et al, 2003). In hippocampal neurons, LTCC have been suggested to couple functionally to small-conductance calcium-activated channels (SK), whereas Ca2+ influx through N-type Ca2+ channels activates BKCa channels (Marrion and Tavalin, 1998). In contrast, conflicting data have been shown in neocortical neurons, with reports demonstrating Ca2+ influx via both L- and N-type Ca2+ channels activates BKCa channels in mouse neocortical pyramidal neurons (Sun et al, 2003), but only N-, P- and Q-type currents activate BKCa channels in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons (Pineda et al, 1998). In vascular smooth muscle, the activation of LTCC can increase [Ca2+]i in the environment of a neighboring BKCa channel leading to its activation (Guia et al, 1999). Activation of BKCa channels was independent of ryanodine receptor activity and could be inhibited by nifedipine. These data support the premise that BKCa and LTCC are colocalized on the smooth muscle cell membrane. Consistent with these findings, urinary bladder smooth muscle steady-state BKCa channel activity is highly dependent on Ca2+ entry through VDCCs, whereas transient BKCa currents require local communication from ryanodine receptors (Ca2+ sparks) to BKCa channels (Herrera and Nelson, 2002). Therefore, we have identified a novel mechanism that can mediate the functional coupling of Ca2+ influx through LTCC and activation of BKCa channels; β2AR can act as a scaffold to bridge the two families of ion channels into a macromolecular complex. Taken together, β2AR localization with the BKCa channel can serve two important purposes: (1) targeting of phosphorylation modulatory proteins to the channel and (2) recruitment of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to the complex, contributing a source of Ca2+ for BKCa channel activation. The formation of the macromolecular complex is independent of β2AR activation status, leading to the constitutive formation of a signaling complex that is present in both brain and smooth muscle. Our findings describe one mechanism to bring about the colocalization of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and BKCa channels and it is conceivable that other mechanisms exist in various tissues to colocalize the two ion channels. However, in HEK293 cells, association of the two ion channels was dependent on expression of β2AR. These findings highlight a novel mechanism to assemble an ion channel macromolecular signaling complex and suggest that homo- and heterodimerization of GPCRs may provide unique scaffolds to permit the assembly of unique macromolecular complexes that regulate ion channel function.

Materials and methods

Immunoprecipitations and kinase assays

Rat brain, bladder, aorta and human lung lysates were homogenized in modified RIPA buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 (v/v), (in mM) 20 EDTA, 10 EGTA, 10 Tris–HCl (pH 7.4)+Complete mini-tablet (Roche), calpain I inhibitor (7 μg/ml), calpain II inhibitor (17 μg/ml) and PMSF (200 μM). Human VSMCs (Cambrex) were grown in SmGM-2 media (Cambrex) and harvested/lysed in (mM) 50 Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 50 NaCl, Triton X-100 (1%), Complete mini-tablet (1 per 7 ml) and PMSF (200 μM). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (14K rpm × 10 min × 2) and supernatants were collected. Immunoprecipitations were performed in 500 μl of (mM) 50 Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 50 NaCl, Triton X-100 (0.25%), Complete (1 per 7 ml) and PMSF (200 μM) using 2 μg β2AR (Santa Cruz, SC-569), BKCa (BD Transduction Laboratories 611248; Alomone Laboratories APC-021), c-myc (SC-40), L-type Ca2+ channel (Alomone, ACC-003) or AKAP150 (SC-6445) antibodies overnight. Immune complexes were collected using protein A (Amersham) or G sepharose (Sigma) for 1 h, followed by extensive washing. All immunoprecipitations included negative controls (peptide-blocked, preimmune, antibody alone). In addition to the antibodies listed above, additional antibodies utilized for immunoblotting include GST-HRP (SC-138) and AKAP79 (BD Transduction Lab-610314). Blots were developed with the use of ECL (Amersham) or Supersignal detection (Pierce). Input represents 5% of immunoprecipitation except 0.3% for co-immunoprecipitations of LTCC–BKCa and AKAP150–BKCa. In all cases, data shown are representative of three or more similar experiments.

For kinase reactions, BKCa was immunoprecipitated from rat brain lysates (1 mg) captured on protein A–sepharose, washed, followed by resuspension in kinase reaction buffer (in mM, 8 MgCl, 10 EGTA, 50 Tris, 50 PIPES; pH 6.8). Phosphorylation was initiated upon the addition cAMP (5 μM, Sigma), PKAc (5 U, Sigma), MgATP (33 μM) and (5 μCi) [32P]γATP (Marx et al, 2001). Reactions were terminated with 6 × loading buffer, size-fractionated on SDS–8% PAGE and exposed to film. Negative controls included preimmune serum, absence of cAMP or PKAc, and PKI.

GST fusion proteins/co-precipitation assays

GST constructs were prepared in pGEX4T-1 representing the β2AR i1 (residues 59–74), i2 (residues 127–153), i3 (217–277) and C-terminus (326–413) (Davare et al, 2001). Co-precipitation assays from total rat brain extract (2 mg) were performed as previously described (Marx et al, 2001).

Constructs

Rat BKCa was cloned via RT–PCR from brain mRNA (Clontech), sequenced and ligated into pcDNA-HisMax (Invitrogen). AKAP79 was cloned via RT–PCR from human brain mRNA (Clontech), sequenced and ligated into pCMV Tag2 (FLAG, Stratagene). Human β2AR was cloned in pCMV Tag3 (Myc, Stratagene). Constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Transfected HEK293 cells were harvested after 24–48 h, lysed in modified RIPA buffer containing 1% Triton X-100. Transfected HEK293 cells were stimulated with isoproterenol (10 μM) (Fraser et al, 2000) for 15 min.

Immunocytochemistry

Human VSMCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min at room temperature (RT), followed by permeabilization with Triton X-100 (0.2%) for 7 min. We used a Cy3 kit tyramide amplification kit (NEL704A; Perkin-Elmer) for detection of BKCa (BD Bioscience; 1:50). β2ARs were detected by conventional fluorescent staining using β2AR Ab (1:100) and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Jackson Immunoresearch, 1:300). Fluorescent images were obtained using a Bio-Rad MRC-600 scanning attachment mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescence microscope. To confirm specific binding of both BKCa and β2AR antibodies, the binding was blocked with corresponding excess antigen or absence of primary antibody (data not shown).

Adult mice (Swiss Webster) were perfused with 4% PFA in 100 mM phosphate buffer (PBS), pH 7.4. The brains were postfixed in cold 4% PFA overnight, cryoprotected with 100 mM PBS containing 30% sucrose for 24 h at 4°C and frozen in OCT (Tissue-Trek). Brain sections (20 μm) were prepared on a cryostat microtome and collected on Superfrost slides (Fisher). β2AR was detected using β2AR (1:25 000) and a Cy3 kit tyramide amplification kit; BKCa was detected by conventional fluorescent staining with anti-BKCa (Affinity Bioreagents, 1:1000) and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500). Images were acquired using a Carl-Zeiss confocal microscope. To confirm specific binding of antibodies, the binding was blocked with corresponding excess antigen or absence of primary antibody (data not shown).

Electrophysiology

The mbr5 clone of mslo1 (Butler et al, 1993), human β2AR and AKAP79 were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Channel activities were recorded from cell-attached patches formed with borosilicate pipettes of 1–3 MΩ resistance. Data were acquired using an Axopatch 200-B patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments) and Pulse acquisition software (HEKA Electronik). Records were digitized at 20-μs intervals and low-pass filtered at 10 kHz with the Axopatch's 4 pole Bessel filter. The pipette and bath solution contained (mM): 140 K-methanesulfonic acid, 20 Hepes, 2 KCl, 2 MgCl2, pH 7.2, either with or without 5 mM EGTA. Salbutamol (Sigma) was either applied in the patch pipette by back-filling or in the bath with final concentrations of 20–40 μM. All recordings were obtained at RT (22–24°C).

Acknowledgments

We thank Geoffrey Pitt for LTCC cDNA, Larry Salkoff for BKCa cDNA, Jeanine D'Armiento for providing human lung tissue, Xiaofeng Wang and Jiayang Sun for help in statistical analyses of data, and Steven Siegelbaum, Andrew Marks and Steven Jones for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from NIH (to SOM and JC), AHA (to SOM), the Whitaker Foundation (to JC), and The Ned and Emily Sherwood Family Foundation and the Kaiser Family Foundation (to SOM). SOM is the Silverberg Assistant Professor of Medicine.

References

- Alioua A, Tanaka Y, Wallner M, Hofmann F, Ruth P, Meera P, Toro L (1998) The large conductance, voltage-dependent, and calcium-sensitive K+ channel, Hslo, is a target of cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation in vivo. J Biol Chem 273: 32950–32956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers S, Salahpour A, Joly E, Hilairet S, Chelsky D, Dennis M, Bouvier M (2000) Detection of beta 2-adrenergic receptor dimerization in living cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 3684–3689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Sinai A, Marbach I, Shorr RG, Levitzki A (1992) The GppNHp-activated adenylyl cyclase complex from turkey erythrocyte membranes can be isolated with its beta gamma subunits. Eur J Biochem 207: 703–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barki-Harrington L, Luttrell LM, Rockman HA (2003) Dual inhibition of beta-adrenergic and angiotensin II receptors by a single antagonist: a functional role for receptor–receptor interaction in vivo. Circulation 108: 1611–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman SA, Zhu S, Han G, White RE (2003) cAMP activates BKCa channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle via cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L1004–L1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW (2000) Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature 407: 870–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Tsunoda S, McCobb DP, Wei A, Salkoff L (1993) MSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding ‘maxi' calcium activated potassium channels. Science 261: 221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl A, Kenyon JL, Uemura D, Fusetani N, Sanders KM (1991) Regulation of Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels by protein kinase A and phosphatase inhibitors. Am J Physiol 261: C387–C392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Izu Y, Xiao RP, Izu LT, Cheng H, Kuschel M, Spurgeon H, Lakatta EG (2000) G(i)-dependent localization of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor signaling to L-type Ca(2+) channels. Biophys J 79: 2547–2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SK, Reinhart PH, Martin BL, Brautigan D, Levitan IB (1991) Protein kinase activity closely associated with a reconstituted calcium-activated potassium channel. Science 253: 560–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong M, Perry SJ, Lin FT, Fraser ID, Hu LA, Chen W, Pitcher JA, Scott JD, Lefkowitz RJ (2001) Regulation of membrane targeting of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 by protein kinase A and its anchoring protein AKAP79. J Biol Chem 276: 15192–15199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare MA, Avdonin V, Hall DD, Peden EM, Burette A, Weinberg RJ, Horne MC, Hoshi T, Hell JW (2001) A beta2 adrenergic receptor signaling complex assembled with the Ca2+ channel Cav1.2. Science 293: 98–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esguerra M, Wang J, Foster CD, Adelman JP, North RA, Levitan IB (1994) Cloned Ca(2+)-dependent K+ channel modulated by a functionally associated protein kinase. Nature 369: 563–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faux MC, Rollins EN, Edwards AS, Langeberg LK, Newton AC, Scott JD (1999) Mechanism of A-kinase-anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) and protein kinase C interaction. Biochem J 343: 443–452 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser ID, Cong M, Kim J, Rollins EN, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, Scott JD (2000) Assembly of an A kinase-anchoring protein–beta(2)-adrenergic receptor complex facilitates receptor phosphorylation and signaling. Curr Biol 10: 409–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fury M, Marx SO, Marks AR (2002) Molecular BKology: the study of splicing and dicing. Sci STKE 2002: PE12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Puri TS, Gerhardstein BL, Chien AJ, Green RD, Hosey MM (1997) Identification and subcellular localization of the subunits of L-type calcium channels and adenylyl cyclase in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 272: 19401–19407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola M, Crest M (1993) Colocalization of active KCa channels and Ca2+ channels within Ca2+ domains in helix neurons. Neuron 10: 689–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SA, Liggett SB (1994) A proline-rich region of the third intracellular loop imparts phenotypic beta 1-versus beta 2-adrenergic receptor coupling and sequestration. J Biol Chem 269: 26215–26219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guia A, Wan X, Courtemanche M, Leblanc N (1999) Local Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels activates Ca2+-dependent K+ channels in rabbit coronary myocytes. Circ Res 84: 1032–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RA, Premont RT, Chow CW, Blitzer JT, Pitcher JA, Claing A, Stoffel RH, Barak LS, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ, Grinstein S, Lefkowitz RJ (1998) The beta2-adrenergic receptor interacts with the Na+/H+-exchanger regulatory factor to control Na+/H+ exchange. Nature 392: 626–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Nelson MT (2002) Differential regulation of SK and BK channels by Ca(2+) signals from Ca(2+) channels and ryanodine receptors in guinea-pig urinary bladder myocytes. J Physiol 541: 483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme JT, Ahn M, Hauschka SD, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (2002) A novel leucine zipper targets AKAP15 and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase to the C terminus of the skeletal muscle Ca2+ channel and modulates its function. J Biol Chem 277: 4079–4087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme JT, Lin TW, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (2003) Beta-adrenergic regulation requires direct anchoring of PKA to cardiac CaV1.2 channels via a leucine zipper interaction with A kinase-anchoring protein 15. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13093–13098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner WJ, Tang MD, Wang LY, Dworetzky SI, Boissard CG, Gan L, Gribkoff VK, Kaczmarek LK (1998) Formation of intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels by interaction of Slack and Slo subunits. Nat Neurosci 1: 462–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauck TM, Faux MC, Labudda K, Langeberg LK, Jaken S, Scott JD (1996) Coordination of three signaling enzymes by AKAP79, a mammalian scaffold protein. Science 271: 1589–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus HG, Schwarzer C, Koch RO, Eberhart A, Kaczorowski GJ, Glossmann H, Wunder F, Pongs O, Garcia ML, Sperk G (1996) Distribution of high-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels in rat brain: targeting to axons and nerve terminals. J Neurosci 16: 955–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume H, Graziano MP, Kotlikoff MI (1992) Stimulatory and inhibitory regulation of calcium-activated potassium channels by guanine nucleotide-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 11051–11055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume H, Takai A, Tokuno H, Tomita T (1989) Regulation of Ca2+-dependent K+-channel activity in tracheal myocytes by phosphorylation. Nature 341: 152–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrutta A, Shen KZ, North RA, Adelman JP (1994) Functional differences among alternatively spliced variants of Slowpoke, a Drosophila calcium-activated potassium channel. J Biol Chem 269: 20347–20351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster B, Nicoll RA, Perkel DJ (1991) Calcium activates two types of potassium channels in rat hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci 11: 23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrion NV, Tavalin SJ (1998) Selective activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by co-localized Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurons. Nature 395: 900–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx SO, Kurokawa J, Reiken S, Motoike H, D'Armiento J, Marks AR, Kass RS (2002) Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science 295: 496–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Gaburjakova M, Gaburjakova J, Yang YM, Rosemblit N, Marks AR (2001) Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of ryanodine receptors: a novel role for leucine/isoleucine zippers. J Cell Biol 153: 699–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR (2000) PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell 101: 365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami K, Fukuzawa K, Nakaya Y (1993) Protein kinase C inhibits the Ca(2+)-activated K+ channel of cultured porcine coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 190: 263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nara M, Dhulipala PD, Wang YX, Kotlikoff MI (1998) Reconstitution of beta-adrenergic modulation of large conductance, calcium-activated potassium (maxi-K) channels in Xenopus oocytes. Identification of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation site. J Biol Chem 273: 14920–14924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ (1995) Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science 270: 633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T, Scott JD (1997) Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science 278: 2075–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaia G, Gallelli L, Vatrella A, Grembiale RD, Maselli R, De Sarro GB, Marsico SA (2002) Potential role of potassium channel openers in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Life Sci 70: 977–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda JC, Waters RS, Foehring RC (1998) Specificity in the interaction of HVA Ca2+ channel types with Ca2+-dependent AHPs and firing behavior in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol 79: 2522–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart PH, Chung S, Martin BL, Brautigan DL, Levitan IB (1991) Modulation of calcium-activated potassium channels from rat brain by protein kinase A and phosphatase 2A. J Neurosci 11: 1627–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart PH, Levitan IB (1995) Kinase and phosphatase activities intimately associated with a reconstituted calcium-dependent potassium channel. J Neurosci 15: 4572–4579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM, Jacobs RA, Hudspeth AJ (1990) Colocalization of ion channels involved in frequency selectivity and synaptic transmission at presynaptic active zones of hair cells. J Neurosci 10: 3664–3684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille R, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ, Charlton MP (1993) Functional colocalization of calcium and calcium-gated potassium channels in control of transmitter release. Neuron 11: 645–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ (2002) Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature 415: 206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoshima J, Akaike N, Kanaide H, Nakamura M (1988) Cyclic AMP modulates Ca-activated K channel in cultured smooth muscle cells of rat aortas. Am J Physiol 255: H754–H759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahpour A, Bonin H, Bhalla S, Petaja-Repo U, Bouvier M (2003) Biochemical characterization of beta2-adrenergic receptor dimers and oligomers. Biol Chem 384: 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom SC, Stockand JD, Hall D, Williams B (1997) Regulation of large calcium-activated potassium channels by protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem 272: 9902–9906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert R, Lehmann G, Serebryakov VN, Mewes H, Hopp HH (1999) cAMP-dependent protein kinase is in an active state in rat small arteries possessing a myogenic tone. Am J Physiol 277: H1145–H1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert R, Nelson MT (2001) Protein kinases: tuners of the BKCa channel in smooth muscle. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22: 505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih M, Lin F, Scott JD, Wang HY, Malbon CC (1999) Dynamic complexes of beta2-adrenergic receptors with protein kinases and phosphatases and the role of gravin. J Biol Chem 274: 1588–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm JF (1987) Action potential repolarization and a fast after-hyperpolarization in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol 385: 733–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Gu XQ, Haddad GG (2003) Calcium influx via L- and N-type calcium channels activates a transient large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ current in mouse neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 23: 3639–3648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Wang HY, Malbon CC (2003) Protein kinase A regulates AKAP250 (gravin) scaffold binding to the beta2-adrenergic receptor. EMBO J 22: 6419–6429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Coghill LS, MacDonald SH, Armstrong DL, Shipston MJ (2003) Leucine zipper domain targets cAMP-dependent protein kinase to mammalian BK channels. J Biol Chem 278: 8669–8677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Duncan RR, Hammond MS, Coghill LS, Wen H, Rusinova R, Clark AG, Levitan IB, Shipston MJ (2001) Alternative splicing switches potassium channel sensitivity to protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 276: 7717–7720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner M, Meera P, Ottolia M, Kaczorowski GJ, Latorre R, Garcia ML, Stefani E, Toro L (1995) Characterization of and modulation by a beta-subunit of a human maxi KCa channel cloned from myometrium. Receptors Channels 3: 185–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhou Y, Wen H, Levitan IB (1999) Simultaneous binding of two protein kinases to a calcium-dependent potassium channel. J Neurosci 19: RC4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RE, Kryman JP, El-Mowafy AM, Han G, Carrier GO (2000) cAMP-dependent vasodilators cross-activate the cGMP-dependent protein kinase to stimulate BK(Ca) channel activity in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 86: 897–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmer HA, Rowe IC, Shipston MJ (2003) Conditional protein phosphorylation regulates BK channel activity in rat cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Physiol 552: 379–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao RP (2001) Beta-adrenergic signaling in the heart: dual coupling of the beta2-adrenergic receptor to G(s) and G(i) proteins. Sci STKE 2001: RE15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XB, Arntz C, Kamm S, Motejlek K, Sausbier U, Wang GX, Ruth P, Korth M (2001) A molecular switch for specific stimulation of the BKCa channel by cGMP and cAMP kinase. J Biol Chem 276: 43239–43245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Wang J, Wen H, Kucherovsky O, Levitan IB (2002) Modulation of Drosophila slowpoke calcium-dependent potassium channel activity by bound protein kinase A catalytic subunit. J Neurosci 22: 3855–3863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YY, Yang D, Zhu WZ, Zhang SJ, Wang DJ, Rohrer DK, Devic E, Kobilka BK, Lakatta EG, Cheng H, Xiao RP (2000) Spontaneous activation of beta(2)- but not beta(1)-adrenoceptors expressed in cardiac myocytes from beta(1)beta(2) double knockout mice. Mol Pharmacol 58: 887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]