Summary

The Casein kinase 1A1 gene (CSNK1A1) is a putative tumor suppressor gene located in the common deleted region for del(5q) myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). We generated a murine model with conditional inactivation of Csnk1a1 and found that Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency induces hematopoietic stem cell expansion and a competitive repopulation advantage whereas homozygous deletion induces hematopoietic stem cell failure. Based on this finding, we found that heterozygous inactivation of Csnk1a1 sensitizes cells to a CSNK1 inhibitor relative to cells with two intact alleles. In addition, we identified recurrent somatic mutations in CSNK1A1 on the non-deleted allele of patients with del(5q) MDS. These studies demonstrate that CSNK1A1 plays a central role in the biology of del(5q) MDS and is a promising therapeutic target.

Introduction

Deletions of chromosome 5q are the most common cytogenetic abnormalities in MDS, and patients with isolated del(5q) have a distinct clinical phenotype (Ebert, 2011; Haase et al., 2007; Hasserjian, 2008). To date, no genes within the common deleted regions (CDR) have been found to undergo homozygous inactivation, copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity, or recurrent mutation (Gondek et al., 2008; Graubert et al., 2009; Heinrichs et al., 2009; Jerez et al., 2012; Mallo et al., 2013). Functional studies have revealed individual genes that contribute cooperatively to the clinical phenotype through genetic haploinsufficiency (Boultwood et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Ebert, 2011; Kumar et al., 2011; Lane et al., 2010; Starczynowski et al., 2010). Heterozygous loss of the RPS14 gene, for example, has been linked to impaired erythropoiesis via p53 activation (Dutt et al., 2011; Ebert et al., 2008). While several 5q genes have been reported to alter hematopoietic stem cell function, the mechanism of clonal dominance of del(5q) cells remains a critical unsolved question (Joslin et al., 2007; Lane et al., 2010; Min et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010a).

CSNK1A1 encodes casein kinase 1α (CK1α), a serine/threonine kinase, and is located in the distal common deleted region (5q32) in del(5q) MDS. In a careful study of gene expression in CD34+ cells from a large cohort of del(5q) and other MDS cases, CSNK1A1 was one of the few genes in the del(5q) common deleted region that has approximately 50% normal expression (Boultwood et al., 2007). Recent studies demonstrated that CSNK1A1 is a tumor suppressor gene in colon cancer and melanoma controlling proliferation by its function as a central regulator of β-catenin activity (Elyada et al., 2011; Sinnberg et al., 2010). In hematopoiesis, stem and progenitor cells respond in a graded fashion to canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Luis et al., 2011). Constitutive activation of β-catenin has been reported to increase HSC numbers followed by apoptosis, HSC depletion, and bone marrow failure (Kirstetter et al., 2006; Scheller et al., 2006). In contrast, less profound activation is associated with HSC expansion with enhanced repopulation potential (Trowbridge et al., 2006). APC, like CK1α, is a member of the β-catenin destruction complex, and is inactivated in approximately 95% of cases with del(5q) MDS. Mice with heterozygous deletion of Apc (Wang et al., 2010a) or heterozygous for the ApcMin allele (Lane et al., 2010) have increased repopulation potential in primary bone marrow transplants, but decreased repopulation potential of secondary transplants due to loss of HSC quiescence.

We sought to explore whether haploinsufficiency or mutation of Csnk1a1 contributes to the biology of del(5q) MDS. In addition, given evidence that Csnk1a1 is selectively essential for murine MLL-AF9 leukemia cells relative to normal hematopoietic cells (Jaras et al., 2014), we investigated whether CK1α is a therapeutic target in del(5q) MDS.

Results

Csnk1a1 is required for adult murine hematopoiesis

To explore the role of Csnk1a1 on hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function, we generated a mouse model in which Csnk1a1 exon 3, essential for CK1α kinase function (Bidere et al., 2009), is flanked by loxP sites. Following crosses to Mx1Cre transgenic mice, we induced Csnk1a1 excision in hematopoietic cells by poly(I:C), and confirmed decreased mRNA and protein expression (Figure 1A and S1A).

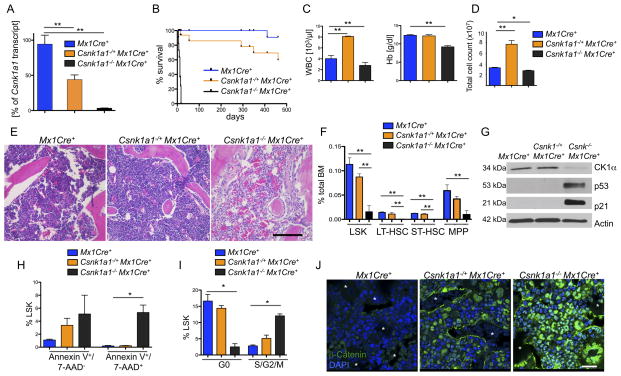

Figure 1. Conditional homozygous inactivation of Csnk1a1 results in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell ablation.

(A) Deletion of Csnk1a1 in whole bone marrow cells was determined 7 days after poly(I:C) induction by quantification of Csnk1a1 transcript levels by qt-RT-PCR. Data is presented as remaining Csnk1a1 transcript expression in percent relative to Mx1Cre+-control mice (mean±SD, n=3). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ (n=10), Csnk1a1−/ −Mx1Cre+ (n=10) and Mx1Cre+ (n=10) control mice. Time point 0 is the day of the first of 3 poly(I:C) inductions. (C) Absolute numbers of white blood cells (WBC) and hemoglobin (Hb) levels in peripheral blood from Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ and Mx1Cre+ controls 10 days after poly(I:C) induction (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.001). (D) Numbers of whole bone marrow cells collected from tibias, femurs and pelvis of Csnk1a1−/+MxCre+, Csnk1a1−/ −MxCre+ 10 days after poly(I:C) induction (mean ±SD; n=3, *p<0.001). (E) Histological analysis of HE-stained spine from Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/ −Mx1Cre+ and Mx1Cre+ controls 10 days after poly(I:C). Scale bar: 200 μm. (F) Analysis of the HSC compartment, defined as LinlowSca1+ckit+ (LSK), long-term (LT; linlowSca1+ckit+CD48−CD150+), short-term (ST; linlowSca1+ckit+CD48−CD150−) HSC and multipotent progenitor cells (MPP, linlowSca1+ckit+CD48+CD150−) in the bone marrow from Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/ −Mx1Cre+ and Mx1Cre+ controls 10 days after poly(I:C), (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05, **p<0.001). (G) Western blot of whole bone marrow lysate 8 days after induction of poly(I:C). (H) Apoptosis was assessed in the LSK fraction from BM by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining (early apoptosis: Annexin V+/7-AAD−; late apoptosis: Annexin V+/7-AAD+, (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.001). (I) Cell cycle was analyzed by combined proliferation (Ki67) and cell cycle (Hoechst 33342) staining in permeabilized LSK from bone marrow (G0: Ki67−/Hoechst−; S/G2/M: Ki67+/Hoechst+), (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (J) Immunofluorescence staining of paraffin-embedded bone marrow with an antibody against β-catenin (DAPI counterstaining). Asterisks highlight erythrocyte filled sinusoids. Scale bar: 20 μm. See also Figure S1.

We first examined whether Csnk1a1 plays a critical role in hematopoiesis. Homozygous deletion of Csnk1a1 in the hematopoietic system (Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+) resulted in rapid lethality 5–17 days after gene excision, accompanied by a significant decrease in all peripheral blood counts and histologic evidence of fulminant bone marrow failure with evidence of ischemia in multiple organs (Figures 1B, C, D, E and S1B).

We next examined whether the observed hematologic abnormalities were associated with changes in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Ten days after Csnk1a1 excision, Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ mice had a highly significant reduction of HSC (LSK, linlowSca1+ckit+) including long-term (LT, linlowSca1+ckit+CD150+CD48−), short-term (ST, linlowSca1+ckit+CD150−CD48−) HSC and multipotent progenitor cells (MPP, linlowSca1+ckit+CD150−CD48+) indicating that Csnk1a1 is essential for HSC survival (Figure 1F and S1C).

CK1α is a major regulator of p53 activity, so we investigated whether Csnk1a1 ablation activates p53 in the bone marrow (Elyada et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012). Homozygous, but not heterozygous Csnk1a1 deletion caused accumulation of p53 as well as p21, a p53 target, demonstrating that p53 is both present and active (Figure 1G). Consistent with this finding, we found that only complete ablation of Csnk1a1 led to significant induction of early and late apoptosis (Figure 1H and S1D). Csnk1a1-ablated HSC exited quiescence and entered the cell cycle, with a marked decrease in the number of Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ HSC (LSK) in G0 and a significant increase in S/G2/M compared to Mx1Cre+ controls (Figure 1I and S1E–F).

Csnk1a1 loss induces increased β-catenin levels in both hematopoietic and stromal cells

CK1α is a critical regulator of β-catenin (Cheong and Virshup, 2011). In our murine model, heterozygous and homozygous knockout of Csnk1a1 induced strong nuclear accumulation of β-catenin (Figure 1J). In the heterozygous knockout bone marrow, positive staining was predominantly in hematopoietic cells proximal to endothelial and endosteal cells, while in the homozygous knockout bone marrow, β-catenin nuclear accumulation was observed in nearly all cell types, highlighting a graded β-catenin activation by Csnk1a1 gene dosage.

In addition, we observed a striking accumulation of β-catenin in the bone marrow stroma cells of heterozygous and homozygous Csnk1a1 knockout mice, consistent with the expression of Mx1Cre in bone marrow stroma (Walkley et al., 2007). We validated this finding in mesenchymal stroma cells (MSC) isolated from endosteal bone (Zhu et al., 2010) and confirmed Csnk1a1 excision in the stroma (Figure S1G). We found strong β-catenin expression in MSC from heterozygous Csnk1a1 knockout mice, and even more pronounced expression in homozygous knockout mice (Figure S1H). In in vitro long-term culture initiating cell assays, both Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ and Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ MSC had significantly impaired hematopoiesis-supporting capacity. Inactivation of β-catenin rescued the effect of Csnk1a1 loss in stromal cells (Figure S1I). The hematopoietic effects of Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency that we found in vitro were also observed in vivo. Eight weeks after pIpC treatment, we observed a significant reduction in bone marrow cellularity and in the percentage of LT- and ST-HSC in Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ mice compared to Mx1Cre+ controls (Figure S1J–M). Consistent with this finding, the survival of Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ primary mice was significantly impaired (Figure 1B). After 15 months Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ mice developed pancytopenia, a significant decrease in the LT-HSC and ST-HSC, and a near complete loss of myeloid progenitor cells (Figure S1N–V). These results are comparable to the recently described consequences of constitutively active β-catenin in osteoblasts (Kode et al., 2014), though we did not observe any evidence of malignant transformation in Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ mice at 15 months.

Cell intrinsic Csnk1a1 ablation leads to bone marrow failure

Having observed that Csnk1a1 excision in primary Mx1Cre+ mice has striking effects on hematopoiesis, and given the cell-extrinsic effects of stromal β-catenin activation on hematopoietic cells (Kode et al., 2014; Lane et al., 2010; Stoddart et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2010a), we examined the cell-intrinsic effects of Csnk1a1 inactivation in hematopoietic cells using bone marrow transplantation into wild-type recipient mice. We transplanted whole bone marrow cells from Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ or Mx1Cre+ mice (CD45.2+) into lethally irradiated WT recipient mice (CD45.1+). Prior to induction of Csnk1a1 excision, 4 weeks after transplantation, more than 90% of peripheral blood cells in recipient mice were reconstituted with donor-derived CD45.2+ cells. All recipient chimeric mice reconstituted with Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ cells became moribund with bone marrow failure 8–14 days after Csnk1a1 excision (Figure 2A and S2A–C). Flow cytometric analysis revealed a complete loss of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in recipient mice. These studies confirm that a cell intrinsic function of Csnk1a1 is essential for hematopoiesis.

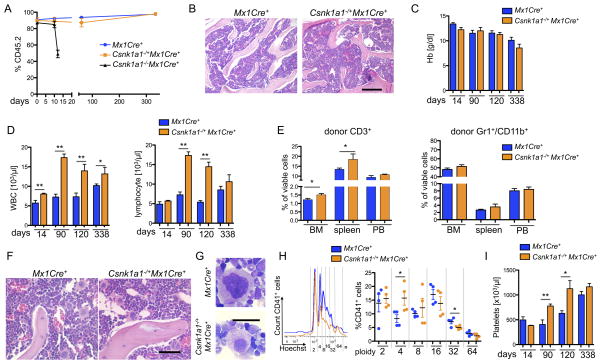

Figure 2. Homozygous Csnk1a1 inactivation causes cell intrinsic hematopoietic stem cell ablation, while Csnk1a1 heterozygous inactivation causes cell-intrinsic lineage expansion.

(A) Donor chimerism (CD45.2) of Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ and Mx1Cre+ derived hematopoietic cells was monitored over time (mean±SD, n=7, **p<0.001). (B) Histomorphological analysis of transplanted Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ and Mx1Cre+ cells 8 weeks after poly(I:C) induction. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Hemoglobin (Hb) levels were followed over time (mean±SD, n=7, non-significant). (D) White blood cell and lymphocyte count were monitored over time (mean±SD, n=7, *p<0.05, **p<0.001). (E) Distribution of donor derived (CD45.2+) myeloid (Gr1+/CD11b+) and T-cells (CD3+) was analyzed by flow cytometry in bone marrow, spleen and peripheral blood (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (F) Histomorphological analysis of megakaryocyte dysplasia in transplanted Mx1Cre+ and Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ 8 weeks after poly(I:C) induction. Scale bar: 100 μm. (G) Detailed megakaryocyte morphology on cytospin preparations (May-Gruenwald-Giemsa staining, Oil immersion, Scale bar: 20 μm). (H) Representative ploidy analysis and quantification on CD45.2+, CD41+ megakaryocytes using Hoechst33342 staining on fixed and permeabilized cells. (mean±SD, n=4, *p<0.05). (I) Platelet counts were taken over time (mean±SD, n=7, *p<0.05). See also Figure S2.

In striking contrast to mice transplanted with Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ cells, mice transplanted with Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ had no change in survival compared to Mx1Cre+ control mice (Figure S2A). Transplanted Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient hematopoietic cells fully reconstituted the bone marrow, resulting in a normal to hypercellular marrow, a normal hemoglobin, and significantly elevated white blood cell counts with lymphocytosis (Figures 2B–D). The lymphocytosis was caused by an increase in T-cells, consistent with reports demonstrating that moderate Wnt-activation promotes T-cell differentiation (Luis et al., 2012; Luis et al., 2011). The percentage of Gr1+CD11b+ myeloid cells (Figure 2E) and CD19+ B-cells (Figure S2D) was not affected.

Pathological evaluation of the Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient bone marrow revealed increased and mildly dysplastic hypolobulated (micro) megakaryocytes in atypical locations, reminiscent of the megakaryocyte morphology in del(5q) MDS (Figure 2F and S2E–F). This phenotype was recapitulated in vitro when whole bone marrow cells were cultured in the presence of 10 ng/ml murine thrombopoietin. Nuclear ploidy analysis of the CD41+ megakaryocytes revealed a shift towards hypoploidy, consistent with hypolobation apparent in cytospins of the cultures (Figure 2G, H). Over time, the mice developed a significantly elevated platelet count (Figure 2I).

Haploinsufficiency of Csnk1a1 leads to β-catenin activation and cell-intrinsic expansion of hematopoietic stem cells

CSNK1A1 has been reported to be a tumor suppressor gene in solid tumors due to activation of β-catenin (Elyada et al., 2011; Sinnberg et al., 2010). We first examined whether Csnk1a haploinsufficiency causes a cell-intrinsic effect on the number and function of HSC in a non-competitive transplantation assay. We found an increase in the percentage of the HSC-enriched LSK compartment, in contrast to the decrease in LSK and LK cells observed in the setting of an abnormal microenvironment in primary Mx1Cre+ animals (Figure 1F and S1M, R). In particular, the proportion of LT-HSC was significantly elevated (Figure 3A).

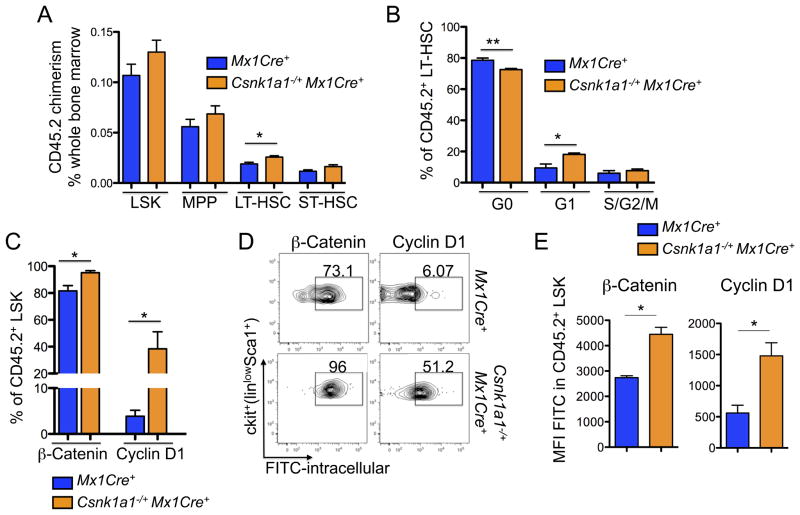

Figure 3. Haploinsufficiency of Csnk1a1 leads to cell-intrinsic expansion of transplanted hematopoietic stem cells.

(A) HSC chimerism (CD45.2) was analyzed in CD45.1 mice repopulated with Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ and Mx1Cre+ cells 8 weeks after induction with poly(I:C) in the LSK, MPP, LT-HSC, and ST-HSC (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (B) Cell cycle was analyzed by combined proliferation (Ki67) and cell cycle (Hoechst 33342) staining in permeabilized LSK and LT-HSC from bone marrow (G0: Ki67−/Hoechst−; S/G2/M: Ki67+/Hoechst+), (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (C) Intracellular flow cytometry for β-catenin and cyclin D1 (FITC-labeled secondary antibody each) on the CD45.2+ viable LSK population (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05). (D) Corresponding representative flow blots to the quantitative analysis of intracellular β-catenin and cyclin D1, accumulation. (E) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of intracellular β-catenin and cyclin D1 in LSK (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05). See also Figure S3.

To analyze whether HSC expansion might be due to exit from quiescence and enhanced HSC proliferation, we performed cell cycle analysis on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. In comparison to CD45.2+ Mx1Cre+ control baseline hematopoiesis, CD45.2+ LSK cells and LT-HSC from Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ cells had a significantly lower percentage of cells in the quiescent G0 fraction (in LT-HSC not LSK) and a significantly higher percentage of cells in the cycling G1 fraction (Figure 3B) and in the S-phase as seen by BrdU incorporation (Figure S3A), consistent with exit from quiescence.

We next examined whether Csnk1a1 heterozygous hematopoietic stem cells have altered β-catenin or cyclin D1 activity, as these pathways could contribute to decreased quiescence. Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ hematopoietic cells, transplanted into WT mice, had increased nuclear β-catenin accumulation by immunohistochemistry (Figure S3B) and by intracellular flow cytometry (Figure 3C–E). We found increased β-catenin in the stem cell enriched LSK fraction. β-catenin accumulation in HSC was accompanied by significantly increased expression of cyclin D1, a major regulator of cell cycle progression, corroborating the G1-phase progression in the cell cycle of Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells. In the lineage-positive fraction, the differences in β-catenin were not apparent. These experiments demonstrate that heterozygous Csnk1a1 inactivation is associated with increased levels of β-catenin in the hematopoietic stem cell.

As heterozygous deletion of APC occurs in approximately 95% of MDS cases and APC and CK1α are both negative regulators of β-catenin, we analyzed the combinatorial effect of Csnk1a1 and Apc on β-catenin levels and hematopoietic stem cell expansion (Figure S3F). Compound heterozygous (Csnk1a1−/+Apc−/+Mx1Cre+) hematopoietic cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice and analyzed over a period of 52 weeks. Compound heterozygous inactivation of Csnk1a1 and Apc resulted in significantly increased LT-HSCs, increased β-catenin levels, and increased activation of the cell cycle in hematopoietic stem cells in long-term transplants (Figure S3G–J). In aggregate, our data highlight a central role for β-catenin in the pathophysiology of del(5q) MDS.

Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient HSCs have increased self-renewal ability in vivo

As Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency leads to a significant increase in cycling LT-HSCs, we examined the functional capacity of Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells in a competitive repopulation assay. Four weeks after transplantation, mice were treated with poly(I:C) to induce Csnk1a1 deletion. Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells out-competed WT cells, while Mx1Cre+ control cells were stable over time, and cells with homozygous Csnk1a1 inactivation were rapidly depleted (Figure 4A).

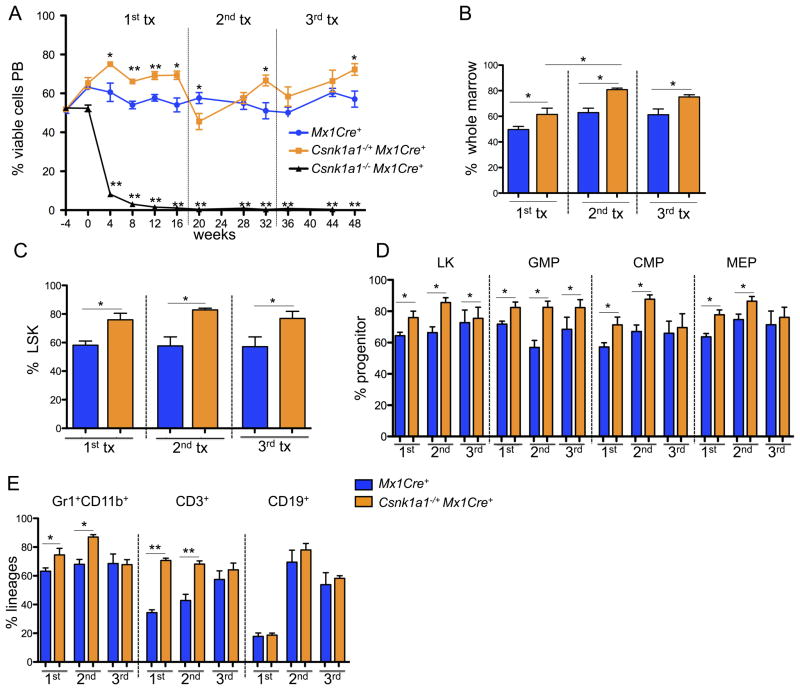

Figure 4. Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient hematopoietic stem cells show increased repopulating ability consistent with increased self-renewal.

(A) Competitive repopulation assays were performed by mixing CD45.2-expressing cells (Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/ −Mx1Cre+, or Mx1Cre+) with CD45.1 competitor cells at an approximately 50:50 ratio, and transplanting the cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. The percentage of CD45.2 donor cell chimerism in the whole peripheral blood from peripheral blood of lethally irradiated recipient animals is shown. Time (weeks) denotes the time relative to termination of the poly(I:C) injections (poly(I:C)=timepoint 0). After 16 weeks, bone marrow was harvested and transplanted for secondary transplants, and 16 weeks later for tertiary transplants in lethally irradiated mice (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05; **p<0.001). (B) Donor chimerism of total bone marrow cells performed at 16 (first competitive transplant), 32 (secondary competitive transplant, 16 weeks after transplantation) or 48 (tertiary competitive transplant) weeks after poly(I:C) induction (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (C, D) Donor chimerism of the hematopoietic stem (LSK) (C) and progenitor cell compartments: LK, linlowSca1−ckit+; common-myeloid progenitors (CMP), LK CD34+CD16/32−; granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP), LK CD34+CD16/32+; myeloerythroid progenitors (MEP), LK CD34−CD16/32− (D) performed at 16 (first competitive transplant), 32 (secondary competitive transplant), or 48 (tertiary competitive transplant) weeks after poly(I:C) induction (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (E) Chimerism of hematopoietic lineages in the bone marrow each 16 weeks after the first, second and third competitive transplant. Composite data of donor (CD45.2+) granulocytes (Gr1+CD11b+), B-cells (CD19+) or T-cells (CD3+) are shown (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05).

To determine the long-term repopulating potential of Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient bone marrow, whole bone marrow cells from the primary recipients were injected into lethally irradiated secondary and tertiary recipients. Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient bone marrow cells had a significantly impaired response to the stress of transplantation, resulting in significantly lower numbers of CD45.2+ donors cells in the peripheral blood compared to Mx1Cre+ controls each 4 weeks after secondary and tertiary transplantation. However, 16 weeks after each round of transplantation, Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells recovered and again out-competed the control cells (Figure 4A).

Having observed a competitive advantage for Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient bone marrow evaluated in the peripheral blood, we next evaluated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the setting of competitive repopulation (Figure 4B–E). At both 16 weeks following the primary transplant and 16 weeks following the secondary transplant, Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells were significantly more abundant than their wild type counterparts in the percentage of LSK cells and downstream myeloid progenitor cells, Gr1+CD11b+ myeloid cells, and CD3+ T-cells in the bone marrow.

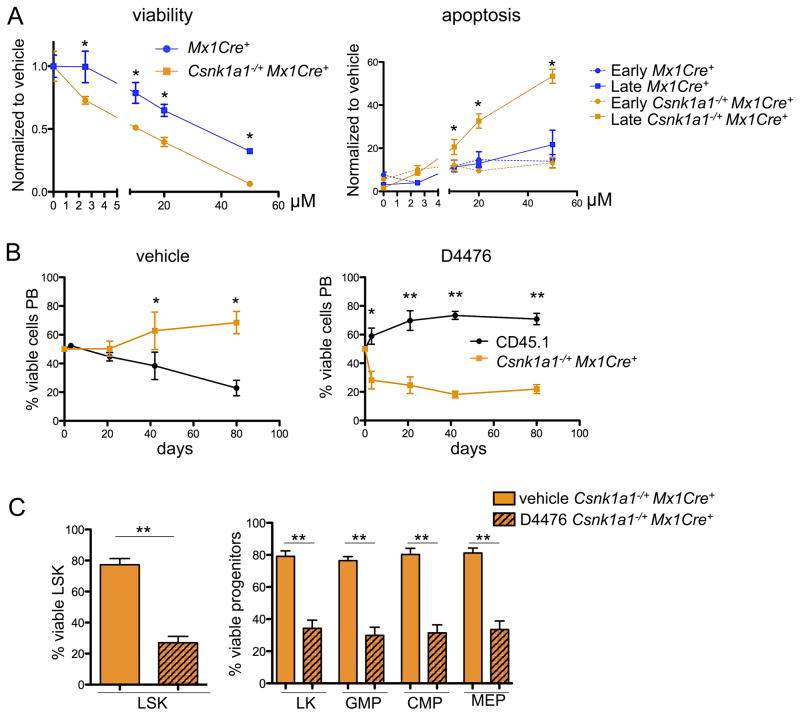

Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency sensitizes cells to casein kinase 1 inhibition

Having demonstrated a selective advantage for cells with heterozygous Csnk1a1 inactivation, and a severe disadvantage for cells with homozygous Csnk1a1 inactivation, we postulated that Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency might sensitize cells to CK1α inhibition. Partial inhibition of CK1α would be expected to cause wild-type cells to have a phenotype similar to haploinsufficient cells, while CK1α inhibition in cells that already have one allele inactivated would approach closer to complete ablation of CK1α activity, thereby establishing a therapeutic window for CK1α inhibition in del(5q) MDS cells. We tested this hypothesis using D4476, a selective small molecule inhibitor of CK1 (Rena et al., 2004). Since D4476 has a short half-life in vivo, we treated purified myeloid progenitors from Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells and Mx1Cre+ controls with D4476 in vitro. D4476 significantly decreased viability and increased apoptosis in Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells relative to Mx1Cre+ controls at a range of concentrations, consistent with a therapeutic window for targeting Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency provides a therapeutical window for the specific treatment of disease-propagating hematopoietic stem cells.

(A) Sorted hematopoietic progenitor cells (LK) were pre-stimulated for 24 hours after the sort and treated for 72 hours with varying concentrations of D4476. Viability of cells was analyzed after 72 hours with the CellTitre glo assay, apoptosis by combined Annexin V and 7AAD staining discriminating early (Annexin V+7AAD−) and late apoptosis (AnnexinV+7AAD+) using flow cytometry. (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (B) 21 days after poly(I:C) treatment, Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ or CD45.1 bone marrow was harvested and LSK cells were sort-purified. Equal ratios of Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ and CD45.1+ LSK were mixed and treated for 72 hours ex vivo with either D4476 or DMSO, followed by transplantation into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice. The chimerism was followed over time in the peripheral blood (mean±SD, n=6, *p<0.05; **p<0.001). (C) The chimerism of Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ in the bone marrow was analyzed in the LSK and progenitor fractions after 12 weeks under DMSO or D4476 treatment conditions (mean±SD, n=6, **p<0.001). See also Figure S4.

To assess the relative effect of D4476 treatment on HSC and progenitor cell function in vivo, we performed a competitive repopulation experiment following ex vivo exposure to D4476. Purified LSK cells from Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ (CD45.2) and WT CD45.1 mice were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and treated ex vivo with either D4476 or DMSO control for 48 hours, followed by injection of the cells into lethally irradiated mice. Following DMSO treatment, Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells out-competed the wild-type controls, as assessed by peripheral blood chimerism. In contrast, following treatment with D4476, Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells were selectively depleted. Similarly, D4476 caused a selective depletion of Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient stem and progenitor cells in the bone marrow (Figure 5B–C) and reduced Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in colony-forming unit assays (Figure S4A).

To examine if partial, systemic inhibition of CK1α would be tolerated in a therapeutic approach targeting haploinsufficiency, we analyzed the effects of global heterozygous Csnk1a1 inactivation. Csnk1a1−/+EIIaCre+ mice, in which heterozygous deletion of Csnk1a1 is induced in all tissues, were born in normal Mendelian ratios without apparent malformations. Histopathological analysis at 6 and 10 months of age revealed structural integrity of organs, and blood counts were normal and stable over this period of time (Figure S4B–D). In aggregate, these data indicate that Csnk1a1 inhibition is an attractive therapeutic approach for the selective targeting of Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells, such as MDS cells with del(5q).

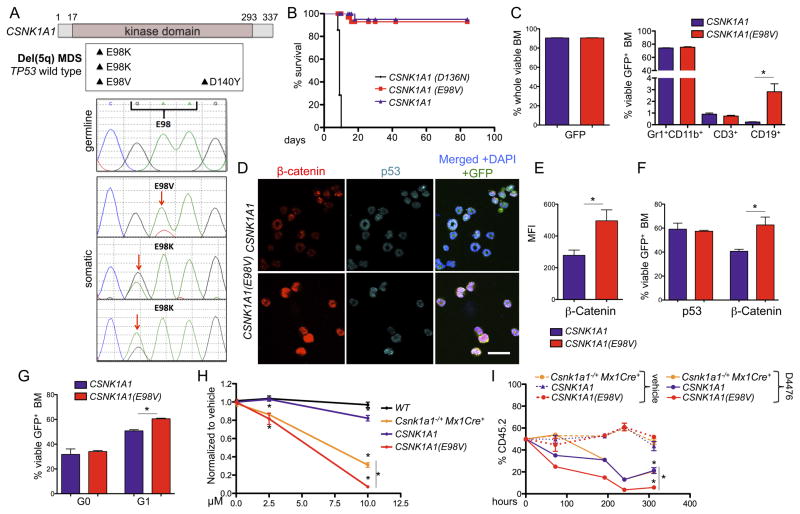

Identification of recurrent somatic CSNK1A1 mutations in patients with del(5q) MDS

In parallel with our functional studies, we performed whole-exome sequencing on MDS samples to identify genetic drivers of del(5q) MDS: genes that are selectively mutated in del(5q) MDS, or genes within the del(5q) CDRs that are recurrently somatically mutated in MDS cases without del(5q). We performed whole-exome sequencing on paired samples (MDS-derived bone marrow sample and matched normal CD3+ cells) of 21 cases: 19 del(5q) and 2 with normal karyotypes (Table S1). We identified two cases with somatic mutations in CSNK1A1, both in untreated cases with del(5q) with wild-type TP53 (Table 1). Both mutations caused the same amino acid change, E98K (Figure 6A). The mutations were confirmed to be present and somatic by Sanger sequencing (Figure 6A). Only a fraction (75% in patient 1 and 42% in patient 2) of the non-deleted CSNK1A1 allele were mutated. By SNP array analysis (Figure S5A), the percentage of the del(5q) MDS clone was 70–80% in patient 1 and 90–100% in patient 2. These data indicate that deletion of chromosome 5q occurred first, and that the CSNK1A1 mutation occurred on the remaining allele of chromosome 5q. The mutation was identified in only less than 5% of the matched control samples from T cells. We analyzed an additional set of 22 MDS samples with isolated del(5q) and found one additional mutation, also altering the same codon (E98V). We examined published MDS genome-sequencing data and found one CSNK1A1 mutation, D140A, in a case with MDS and a normal karyotype (Graubert et al., 2012) and CSNK1A1 D140Y in a patient with del(5q) MDS (Woll et al., 2014). Additional CSNK1A1 mutations were identified in the literature in other malignancies (Dulak et al., 2013; Sato et al., 2013), two of which are also missense mutations of codon 98, and one of codon 140 (Figure S5B). CSNK1A1 is therefore a gene with recurrent somatic mutations within a del(5q) CDR in MDS.

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients with the identified somatic CSNK1A1 mutations

| #1 | #2 | #3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 85 | 82 | 65 |

| Gender | M | F | F |

| FAB | RA | RA | RA |

| Karyotype | 46, XY, del(5)(q13q31) [17]/46, XY[3] | 46, XX, del(5)(q13q33)[14]/46, XX[6] | 46, XX, del(5)(q13q33)[4]/46, XX[2] |

| IPSS-R | 2, low risk | 1, very low risk | 1, very low risk |

| TP53 | wild type | wild type | wild type |

| Hemoglobin [g/dL] | 10.6 | 11.8 | 9.5 |

| Absolute neutrophil count [109/l] | 49.6 | 0.951 | 5.01 |

| Platelets [cells/μl] | 140,000 | 118,000 | 72,000 |

M: Male; F: Female; FAB: French-American-British classification; RA: Refractory Anemia. IPSS-R: revised International Prognostic Scoring System

Figure 6. Identification and functional characterization of CSNK1A1 mutations in del(5q) MDS patients.

(A) Summary of CSNK1A1 mutations identified in del(5q)MDS patients (upper panel) and Sanger sequencing results around codon 98 of the normal control (germline) and tumors (somatic) (lower panel). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of chimeric mice transplanted with Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells expressing Csnk1a1 cDNA, Csnk1a1 D136 cDNA or Csnk1a1 E98V cDNA. Timepoint 0 is the first day of poly(I:C) induction (n=5). (C) GFP expression in whole BM (left) and distribution of the different lineages (Gr1+CD11b+ neutrophils, CD3+ T-cells, CD19+ B-cells) in GFP+ BM cells (right). (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05). (D) Co-immunofluorescent staining of β-catenin and p53 in cytospin preparations of red blood cell lysed whole bone marrow cells (red: β-catenin, turquoise: p53, green: GFP MIG vector, blue: DAPI). Scale bar 20 μm. (E) Quantification of β-catenin intensity using the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05). (F) Intracellular flow cytometry measurement of β-catenin and p53 in permeabilized whole bone marrow cells. (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05). (G) Cell cycle was analyzed by combined Ki67 and Hoechst33342 staining in permeabilized whole bone marrow cells. (mean±SD, n=3, *p<0.05). (H) GFP+ LSK from mice transplanted with either CSNK1A1 or CSNK1A1 E98V-expressing Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ cells as well as Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient LSK and WT LSK were sort purified and exposed to vehicle, 2.5 or 10 μM D4476 for 72 hours and viability of cells was analyzed after 72 hours with the CellTitre glo assay (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (I) LSK (all CD45.2) isolated as in (H) were treated in competition to CD45.1 wild type cells in one culture well to analyze selective ablation of cells under the same culture condition. (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). See also Figure S5 and Table S1.

We tested the function of the CSNK1A1 E98V mutation by retroviral expression of the mutant cDNA in Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ hematopoietic cells, reflecting the finding of mutations in del(5q) cells without a wild-type allele. Ckit+ hematopoietic cells were transduced with retroviruses expressing a wild type CSNK1A1 cDNA, the CSNK1A1 E98V mutation, or the CSNK1A1 D136N cDNA with mutational inactivation of the CK1α kinase activity (Bidere et al., 2009; Davidson et al., 2005; Peters et al., 1999). Four weeks after transplantation of transduced cells into lethally irradiated recipients, we induced excision of both endogenous Csnk1a1 alleles. Mice transplanted with cells expressing the kinase-dead CSNK1A1 D136N cDNA died rapidly as expected, as the mutant cDNA was unable to rescue the effect of the Csnk1a1 ablation (Figure S5C–E). In contrast, cDNA overexpressing CSNK1A1 and CSNK1A1 E98V cDNA rescued the HSC ablation in Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ cells (Figure 6B and S5C). After 12 weeks, the bone marrow of the recipient mice was fully reconstituted by cells transduced with either CSNK1A1 cDNA or CSNK1A1 E98V cDNA (Figure 6C). Cells expressing CSNK1A1 or CSNK1A1 E98V reconstituted lineages, as well as stem and progenitor cells (Figures 6C and S5F).

We next examined the cellular consequences of the CSNK1A1 E98V mutation. Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ cells transduced with CSNK1A1 E98V cDNA, compared to cells expressing the wild-type cDNA, had increased nuclear β-catenin accumulation by immunofluorescence, and higher β-catenin accumulation by intracellular flow cytometry (Figure 6D–F and S5G). While expression of the kinase-dead CSNK1A1 D136N cDNA caused increased apoptosis and HSC ablation, the CSNK1A1 E98V cDNA did not induce p53 or apoptosis (Figure 6, D, F and S5G, H). Furthermore, bone marrow cells expressing CSNK1A1 E98V cDNA had an increased frequency of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, with no change in cells in G0 (Figure 6G). In aggregate, these findings indicate that the codon 98 mutations are not loss-of-function, and do not cause increased p53 activation, but do increase β-catenin activity, providing a potential selective advantage to del(5q) MDS cells.

Having demonstrated that Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells are sensitized to CK1 inhibition, we tested whether CSNK1A1 E98V-expressing cells in a Csnk1a1 null background are more sensitive to treatment with a CK1 inhibitor than wild-type or Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells. GFP+ CSNK1A1 E98V and CSNK1A1 expressing LSK cells and Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient and wild-type LSK cells were sorted and treated with D4476 (Figure 6H). Treatment of Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ cells transduced with CSNK1A1 E98V cDNA were significantly more sensitive to the compound than Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells. Similar results were obtained from a co-culture competition assay in the presence of D4476 (Figure 6I and S5I).

Discussion

Our studies converged on a critical role for CK1α in the pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS. Activation of β-catenin downstream of Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency in a murine model, and downstream of CSNK1A1 mutations in MDS patient samples, provides a potential mechanism of clonal selection. In contrast, homozygous inactivation of Csnk1a1 is not tolerated due to activation of p53. The sensitivity of hematopoietic cells to Csnk1a1 gene dosage provides a therapeutic window for targeting CK1α in haploinsufficient cells.

In a previous study, we found Csnk1a1 to be a therapeutic target in AML, and that D4476 selectively kills leukemic stem cells relative to normal hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (Jaras et al., 2014). Both the knockdown of Csnk1a1 using shRNA and the genetically engineered mouse model show that reduction of Csnk1a1 expression by more than 50% has a negative effect on hematopoietic stem cell expansion and survival. Haploinsufficiency, in contrast, increases the number and function of hematopoietic stem cells.

β-catenin is a major driver of stem cell self-renewal and neoplasia in multiple cellular lineages (Baba et al., 2005; Elyada et al., 2011; Willert et al., 2003; Yeung et al., 2010). Hematopoietic stem cells have a graded response to β-catenin, with modest levels leading to increased stem cell self-renewal (Baba et al., 2005), and more marked induction leading to stem cell exhaustion (Albuquerque et al., 2002; Kirstetter et al., 2006; Lane et al., 2010; Luis et al., 2011). Forced expression of β-catenin, in combination with HOXA9 and MEIS1, induces leukemia in progenitor cells (Wang et al., 2010b), and β-catenin is essential for leukemia cells driven by the MLL-AF9 oncogene (Miller et al., 2013). Histopathological studies have found nuclear, non-phosphorylated β-catenin expression in bone marrow specimen from de novo AML and MDS patients to be a predictor for clinical outcome, and these studies suggested an association between nuclear β-catenin expression and del(5q) MDS, though the number of samples studied was too small to be conclusive (Xu et al., 2008). CK1α is a member of the β-catenin destruction complex and is therefore a known, central regulator of β-catenin activity (Cheong and Virshup, 2011). In our studies, Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency conferred to increased intrinsic self-renewal of HSC, with associated nuclear β-catenin accumulation, cyclin D1 induction, and exit from quiescence in LT-HSCs.

Increased LT-HSC proliferation and expansion was a cell-intrinsic effect in our study. Inactivation of Csnk1a1 in stromal cells in our model caused stromal β-catenin levels to increase, with consequent effects on hematopoiesis, including pancytopenia and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell depletion. This observation is consistent with recent studies demonstrating that β-catenin accumulation in the stroma negatively regulates HSC maintenance and might also contribute to leukaemogenesis (Kode et al., 2014; Lane et al., 2010).

APC, another member of the β-catenin destruction complex, is also deleted in the vast majority of del(5q) MDS cases. Hematopoietic cells with Apc haploinsufficiency have been shown to have enhanced repopulation potential, indicating a cell intrinsic gain of function in the LT-HSC population. However, in contrast to Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency, Apc haploinsufficient bone marrow was unable to repopulate secondary recipients due to loss of the quiescent HSC population (Lane et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010a). Different levels of Wnt activation may explain these findings. Similarly, deletions of Csnk1a1 and of Apc in the gut have significantly different effects. While Csnk1a1 deletion led to robust activation of Wnt target genes and proliferation without invasion, Apc deletion induced immediate dysplastic transformation and rapid death (Elyada et al., 2011). CK1α has many phosphorylation targets that could alter stem cell function (Bidere et al., 2009; Elyada et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012). As has been postulated previously, it is possible that CK1α inactivation restrains hyperactive Wnt signaling through mechanisms yet to be defined.

Our sequencing studies revealed recurrent mutations in a gene located in an MDS common deleted region on chromosome 5q. SNP array studies have not identified any genes on 5q that undergo homozygous deletion in del(5q) MDS (Gondek et al., 2008; Graubert et al., 2009; Heinrichs et al., 2009). Indeed, our studies would indicate that homozygous inactivation of CSNK1A1 would be highly deleterious to a hematopoietic cell. Although CSNK1A1 mutations in MDS are rare, they provide powerful evidence that these lesions are genetic drivers of clonal dominance. In functional studies, expression of the identified CSNK1A1 E98V allele, in the setting of inactivation of both wild-type alleles to mimic the genetic context of the mutations observed in patients, caused an induction of nuclear β-catenin and a significant HSC cell cycle progression compared to expression of the wild-type CSNK1A1. Future experiments using a conditional knock-in mouse strain will be helpful to study the long-term hematopoietic effects of the mutant allele expressed at physiological levels.

Our results indicate that CSNK1A1 is a CYCLOPS (copy number alteration yielding cancer liabilities owing to partial loss) gene (Nijhawan et al., 2012). Heterozygous inactivation of Csnk1a1 sensitized cells to CK1 inhibition with D4476. The ablation of hematopoiesis in Csnka1a1 null cells, and the normal to enhanced hematopoiesis in Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells, provides a mechanistic basis for this therapeutic window. We demonstrated that systemic Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency in our murine model does not have significant effects on other organs, indicating that partial pharmacologic inhibition of CK1 would likely be well tolerated. While D4476 does not have pharmacokinetic properties for in vivo use, and lacks specificity for CK1α, a more selective compound has the potential for therapeutic utility in the treatment of patients with myeloid malignancies associated with del(5q).

Experimental Procedures

Generation of a Csnk1a1 conditional knockout mouse

Mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells with Csnk1a1 exon 3 targeted in a C57BL/6N genetic background were generated by the KOMP consortium (project ID: CSD45494). The neomycin/lacZ cassette was flipped out in vitro by transfection of a plasmid expressing the flippase recombinase (FRT). Successful FRT recombination was validated by PCR (forward primer: 5′-TCGCACTTGAGCTATTGGGGAGT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-AGGCATGGTAGCTCACACCTGA-3′). Following confirmation of germline transmission, mice were crossed with the Mx1-Cre mouse strain (Jackson: 002527). To excise Csnk1a1 exon 3, Csnk1a1 conditional mice were given three rounds of 200 μg of poly(I:C) (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using intraperitoneal injections. Successful excision of Csnk1a1 exon 3 was validated using forward primer above and reverse 5′ AGCTGGGCTACCAAGAGGCAA-3′ primer. All experiments and procedures were conducted in the Children’s Hospital Boston animal facility and were approved by the Children’s Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry

Bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated by flushing and crushing pelvis and hind leg bones with PBS (GIBCO) + 2% FBS + Penicillin/Streptomycin (GIBCO). Whole bone marrow was lysed on ice with red blood cell (RBC) lysis solution (Invitrogen/Life Technologies), and washed in PBS (GIBCO) + 2% FBS. Single-cell suspensions of spleen were prepared by pressing tissue through a cell strainer followed by red blood cell lysis. Cells were labeled with monoclonal antibodies in 2% FBS/PBS for 30 min on ice (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures for the information on antibodies used) and analyzed using an LSRII (BD biosciences). Apoptosis (Annexin V apoptosis detection kit, ebioscience) and cell cycle (Ki67 cell cycle and proliferation kit, BD biosciences) assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bone marrow transplantation assays

In transplantation assays of Csnk1a1 cells into CD45.1 wild-type mice, 5×106 freshly isolated whole bone marrow cells were harvested before poly(I:C) treatment, and injected into the tail-vein of lethally irradiated (1050 Rads) CD45.1-positive B6. SJL (Jackson) recipient mice without support cells. In competitive bone marrow transplantation studies, 2×106 freshly isolated bone marrow cells were harvested and transplanted via tail vein into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice together with 2×106 freshly isolated CD45.1+ bone marrow competitor cells in an equal ratio. Four weeks after transplantation, blood samples were taken and donor cell chimerism was determined by flow cytometric analysis. Shortly thereafter, mice were given three rounds of poly(I:C) treatment and donor blood cell chimerism was determined every four weeks.

Western blots

Western blots were performed according to standard protocols. In brief, cell lysis was performed in RIPA buffer with protease/phosphatase inhibitors. After protein quantification, lysates were resuspended in Laemmli Sample Buffer, and loaded to gradient gels (Criterion Tris-HCl Gel, 8–16%). Proteins were transferred onto Immobilon polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes. As primary antibodies β-catenin (rabbit polyclonal, 9562, 1:500, Cell Signaling), p53 (mouse monoclonal, DO-1, 1:500, Santa Cruz), p21 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:200, C-19, Santa Cruz), Cyclin D1 (rabbit monoclonal, 1:200, SP4, Thermo Scientific) and GAPDH (rabbit polyclonal, 1:4000, Bethyl laboratories Inc) were applied.

Histopathology

For histological and immunohistochemical analyses, murine organs were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde overnight, dehydrated and prepared for paraffin embedding. Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining was done according to routine protocols. For immunohistochemical stainings, the Avidin-Biotin Complex (ABC) was applied. Peripheral blood smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich). Images were obtained on a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a SPOT RT color digital camera model 2.1.1 (Diagnostic Instruments).

Viral vector cloning

MIG-CSNK1A1, MIG-CSNK1A1(E98V) and MIG-CSNK1A1(D136N) were flanked by Not1 and Xho1 sites for convenient cloning into the MIG vector backbone.

Patient samples and Sequencing

Patients included in the whole exome sequencing were diagnosed between 2008 and 2013 at different Spanish hospitals affiliated to the MDS Spanish Group (Grupo Español de SMD, GESMD). Patients were diagnosed with MDS according to the French-American-British and 2008 World Health Organization classification. Samples were deidentified at the time of inclusion. This study was approved by institutional review boards (Clinical Research Ethics Committee Institut Català de la Salut/Germans Trias i Pujol Hospital and Clinical and Ethics Committee Parc de Salut MAR) and performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their informed written consent. Whole-exome sequencing was performed using paired-end reads generated from DNA libraries prepared from MDS samples (whole bone marrow) with matched normal samples (CD3+ lymphocytes isolated from peripheral blood). Whole-exome hybrid capture was carried out on 3 μg of genomic DNA, using the SureSelect Human Exome Kit version 3 (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The captured exome library was sequenced with 100bp paired-end reads on an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Whole-exome sequencing data were analyzed using an in-house bioinformatics pipeline as previously reported (BWA; GATK’s; VarScan2; SAMTools; SnpEff: (Koboldt et al., 2012; McKenna et al., 2010). Somatic mutations identified as alterations present in tumor but not in the matched CD3+ sample were validated by Sanger sequencing. Sanger sequencing was performed on genomic DNA isolated from whole bone marrow cells and CD3+ cells using GentraPuregene Cell kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Exon 3 from CSNK1A1 gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the following primers: forward primer: 5′-TCCTTTTGTTTCGTTAGGTGGT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AAGGTTAAATAGTGATGCACAGGA-3′; amplification size: 251 bp). Single nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP-A) were performed with Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 from Affymetrix. Assays were performed according to Affymetrix protocols.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Related to figure 1. Characterization of primary Mx1Cre+ mice.

(A) Validation of Csnk1a1 excision after poly(I:C) by PCR (left) and by Western Blot (right). (B) Autopsies including histopathological examinations in Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ mice revealed pale parenchymal organs and rarefication of the red pulp in the spleen with extramedullar erythropoiesis (arrows), prominently in subcapsular localization. Liver and the myocardium showed signs of ischemia. In the liver cytoplasmatic vacuolization and pyknotic nuclei were observed. Defined areas of the myocardium showed wavy fibers with loss of transversal striations, partially with loss of the cell nucleus (arrows). HE-staining. Scale bar each as indicated. (C) Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells were analyzed by staining murine whole bone marrow cells with a lineage cocktail (CD3, B220, Gr1, CD11b, Ter119) and viability staining (DAPI) and either (a) classical stem and myeloid progenitor cell markers to dissect the LSK compartment in MPP (LSK CD48+), LT-HSC and ST-HSC (CD48 and CD150/Slamf1) and the LK compartment in GMP, CMP, MEP [FcgRII/III (CD16/32) and CD34] or (b) 6 myelo-erythroid progenitor cell fractions of the LK compartment [CD41 (Itga2b), Endoglin (CD105), CD150 (Slamf1), FcgRII/III (CD16/32), Ter119]. Representative contour blots of Mx1Cre+ control, Csnk1a1−/+ Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/− Mx1Cre+ stem and progenitor cells, only live cells are displayed. (D) Representative flow blots of Annexin V and Hoechst stained LSK cells. (E) Ki67 immunohistochemistry on paraffin-embedded bone marrow sections. Scale bar as indicated. (F) Representative contour flow blots of combined Ki67 (proliferation) and Hoechst 3342 (cell cycle) staining gating on LSK cells. (G) Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) were negative for CD31 and CD45 but positive for CD29, Sca1, CD44 and CD105. The Csnk1a1 excision was confirmed by PCR (n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.05). (H) β-catenin and p53 immunofluorescence in MSC isolated from Mx1Cre+ control, Csnk1a1−/+ Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/− Mx1Cre+ bone marrows (DAPI counterstain: blue, β-catenin: green, p53: red. Scale bar as indicated). (I) Limiting-dilution analysis of long-term culture-initiating cells (LT-CIC) was applied as a quantitative method of estimating hematopoietic stem cell-supporting activity of MSC isolated from Mx1Cre+ controls and Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/+β-catenin−/+Mx1Cre+ and Csnk1a1−/+p53−/+Mx1Cre+MSC (n=10, mean±SD, *p<0.05). (J, K) Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient mice were analyzed eight weeks after poly(I:C) i.p. injections. Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient mice had a rather hypocellular bone marrow, but normal blood counts (n=5, mean±SD, *p<0.05). (L) Histopathological evaluation revealed hypolobulated micro-megakaryocytes (arrows) but normal trilineage maturation of hematopoiesis. (M) Analysis of the stem cell compartment after eight weeks (n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.05). (N) Blood counts of aged Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient mice were analyzed 15 months after induction of poly(I:C), (n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.05*; **p<0.001). The peripheral blood revealed a pan-cytopenia consistent with (O) a hypocellular partially empty bone marrow in HE-staining. Scale bar as indicated. (P) Detailed histopathological analysis demonstrated a significant reduction of the myeloid and erythroid lineage, but quite intact lymphoid maturation. The stroma, in particular surrounding sinusoids, was prominent and significant dysplasia of small megakaryocytes with signs of emperipolesis and apoptosis was noted. No malignant transformation; the blast count in BM smears was <5%. HE staining, Scale bar as indicated. (Q) Representative lin−Sca1−ckit+ flow plots and (R) composite data of hematopoietic stem cell analysis by flow cytometry (lin−Sca1+ckit+, LSK cells), including long-term (lin−Sca1+ckit+CD48−CD150+, LT-HSC) and short-term (lin−Sca1+ckit+CD48−CD150+, ST-HSC) hematopoietic stem cells (n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.05; **p<0.001). (S) Composite data of flow cytometry analysis of lin−Sca1+ckit− cells reflecting the stromal compartment (n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.05). (T, U) Cell cycle analysis of the LSK fraction by flow cytometry (n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.05). (V) Intracellular expression of β-catenin as well as p53 in HSC (LSK), (n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.05).

Figure S2: Related to figure 2. Rapid bone marrow failure after Csnk1a1 ablation is an intrinsic effect.

(A) Kaplan Meier survival curves over a time frame of 351 days [(day 0=first dose of poly(I:C)]. (B) Representative histomorphological analysis of bone marrow and spleen showing an empty bone marrow and extramedullar hematopoiesis, respectively, in Csnk1a1− − Mx1Cre+ mice 10 days after poly(I:C) treatment. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Representative flow plots of the CD45.1 and CD45.2 chimerism as well as the HSC compartment. (D) CD19+ B-cells in bone marrow (BM), spleen or peripheral blood (PB) (composite data, mean±SD, n=5, no significant differences). (E) CD71/Ter119 analysis of the bone marrow showing a terminal differentiation defect from the polychromatophilic erythroblast stage (R3) to the orthochromatophilic erythroblast/reticulocyte stage (R4), (n=5, mean±SD, *p<0.05). (F) The bone appeared normo- to hypercellular in mice transplanted with Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ in the long-term transplant setting. Micro-megakaryocytes were increased in their number (as highlighted by blue asterisks), hypolobulated and presented with spherical nuclei. Scale bar as indicated.

Figure S3: related to figure 3: Expanded HSC and increased β-catenin levels in Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ and Csnk1a1−/+Apc−/+Mx1Cre+ mice.

(A) To further analyze proliferation changes in the expanded LT-HSC compartment in transplanted Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells, we performed bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation analysis. Mice received an initial intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (1 mg/6 g bodyweight) 18 hours prior to sacrifice. BrdU incorporation (S-phase) was analyzed in CD45.2+lin−Sca1+ckit+CD150+CD48− cells (LT-HSC). Quantification and composite data of cycling BrdU+ LT-HSC in transplanted Csnk1a1 haploinsufficient cells versus Mx1Cre+ cells (mean±SD, *p<0.05, n=4). (B) β-catenin immunohistochemistry on bone marrow chimeras of Mx1Cre+ and Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ transplants. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Representative contour blots of β-catenin and cyclin D1 expression in CD45.2 LK (lin−Sca1−ckit+) cells. (D) Composite data depicting CD45.2+ LK cells expression of β-catenin and cyclin D1 in progenitor cells of Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+-derived LK cells compared to Mx1Cre+ LK cells (n=5, mean±SD, *p<0.05, **p<0.001). (E) Composite data of intracellular β-catenin and cyclin D1 flow cytometry on lineage+ cells (mean±SD, *p<0.05). (F) Lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice were transplanted with Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/+Apc−/+Mx1Cre+ or Mx1Cre+ whole bone marrow cells. Four weeks after transplantation, the gene excision was induced with poly(I:C). Morphological analysis of whole bone marrow cytospin preparations of mice transplanted with Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/+Apc−/+Mx1Cre+ or Mx1Cre+ show trilineage differentiation without evidence for leukemic transformation and blast counts <5%. MGG staining, Scale bar 100 μm. (G) CD45.2+ chimerism of the hematopoietic stem cell enriched bone marrow fraction (mean±SD, n=5, ns). (H) HSC chimerism (CD45.2) in the whole bone marrow 336 days after induction with poly(I:C) including LT-HSC, ST-HSC and MPP (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (I) Representative flow blot and composite data of cell cycle analysis in HSC (lin−Sca1+ckit+) using Ki67 and Hoechst 3342 staining (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05). (J) Histogram analysis of intracellular β-catenin expression analysis in permeabilized LSK, quantified mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of β-catenin in LSK (mean±SD, n=5, *p<0.05) and β-catenin immunofluorescence on bone marrow cytospins (arrows, blue: DAPI counterstaining, green: β-catenin; scale bar: 80 μm).

Figure S4: related to figure 5: Csnk1a1 germline haploinsufficiency does not affect structural integrity of abdominal or thoracical organs

(A) Hematopoietic stem cells (LSK) were sorted from Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ and Mx1Cre+ mice and subjected to 10 μM D4476 or vehicle. After 48 hours cells were harvested and methylcellulose assays were started with 3000 LSK each. After 8 days, cells were recovered from methylcellulose and re-plated on fresh methylcellulose. n=3 biological donors and 3 technical replicates. (mean±SD, n=9, *p<0.05). (B) Genomic DNA was isolated and the excision of the targeted exon 3 was validated by PCR in Csnk1a1−/+EIIaCre+ and EIIaCre+ cells. (C) 6 and 10 months old Csnk1a1−/+EIIaCre+ mice do not differ in their peripheral blood counts from EIIaCre+ mice (mean±SD, n=4, ns). (D) Histopathological comparison of lymph node, lung, myocardium, spleen, liver, kidney, pancreas, small intestine and large intestine in Csnk1a1−/+EIIaCre+ or EIIaCre+ mice does not show any structural abnormalities or differences between the two groups. Scale bar as indicated.

Figure S5: related to figure 6: The identified CSNK1A1 mutation in del(5q) MDS patients occurs on the remaining allele of chromosome 5q and is not a loss of function mutation.

(A) Single nucleotide polymorphism arrays (SNP-A) were performed with Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0. The percentage of the 5q-deletion was 70–80 % in patient 1 and 90–100 % in patient 2. (B) Mutations of CSNK1A1 in the same codon as in del(5q) MDS in other malignancies/tissues according to the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer [*COSMIC, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk; (Dulak et al., 2013; Graubert et al., 2012; Sato et al., 2013)]. Somatic missense mutations in CSNK1A1 were identified in an adenocarcinoma of the esophagus (E98K), a Burkitt lymphoma (E98 V) and a renal clear cell carcinoma (D140H). (C) GFP expression in the peripheral blood over a period of 80 days [day 0= day of first poly(I:C) injection; mean±SD, n=5]. (D) Analysis of the CSNK1A1(D136N) (GFP) distribution in the bone marrow. (mean±SD, n=5). (E) Representative flow blot of the HSC compartment in mice transplanted with Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ hematopoietic cells overexpressing CSNK1A1(D136N). (F) The bone marrow of mice transplanted with Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ ckit+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells transduced with CSNK1A1 cDNA or CSNK1A1(E98V) cDNA was analyzed 12 weeks after induction of the Csnk1a1 excision by poly(I:C). Compound data show the distribution of the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the GFP+ transduced bone marrow fraction (mean±SD, n=3, ns). (G) Histogram showing β-catenin and p53 expression in RBC lysed, GFP+ whole bone marrow cells. (H) Composite data of apoptosis detected by Annexin in GFP+ whole bone marrow cells (mean±SD, n=3, ns). (I) Western blots showing CK1α protein expression (Santa Cruz, Casein kinase 1a, C19) in Mx1Cre+, Csnk1a1−/+Mx1Cre+ as well as transduced, transplanted and sorted CSNK1A1 or CSNK1A1(E98V) expressing bone marrow cells in a Csnk1a1−/−Mx1Cre+ background [2 weeks after induction of poly(I:C); n=3 biological replicates].

Table S1: related to Figure 6: Patients with del(5q) MDS and according samples analyzed by whole exome sequencing.

Highlights.

Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency increases HSC number and function

Csnk1a1 homozygous inactivation leads to bone marrow failure

In del(5q) MDS, CSNK1A1 is deleted, and CSNK1A1 is a therapeutic target

CSNK1A1 is recurrently mutated in del(5q) MDS

Significance.

Our studies provide functional and genetic evidence indicating that CSNK1A1 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS. We found that heterozygous inactivation of Csnk1a1 causes hematopoietic stem cell expansion and β-catenin activation. In addition, we found that Csnk1a1 haploinsufficiency sensitizes cells to casein kinase inhibition, demonstrating an approach for the targeting of heterozygous deletions in cancer. While no recurrently mutated genes have been previously identified in genes within the common deleted regions of chromosome 5q, we found recurrent mutations in CSNK1A1 in a subset of del(5q) MDS patients. In aggregate, these findings indicate that CSNK1A1 is a promising therapeutic treatment for the treatment of del(5q) MDS.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the HSCI/Children’s Hospital Boston (Mahnaz Paktinat and Ronald Mathieu) and Dana Farber Cancer Institute Flow Cytometry Core Facility (Suzan Lazo-Kallanian). We warmly thank all members of the Ebert laboratory, in particular Damien Wilpitz, Brenton G. Mar and Jan Krönke, as well as Steven Lane (Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Brisbane, Australia), Dagmar Walter and Michael Milsom (HI-STEM, Heidelberg, Germany) for their insights, scientific discussion and collegiality. This work was supported by the NIH (R01HL082945), the Claudia Adams Barr Program, a Gabrielle’s Angel Award, and a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar Award to B.L.E. R.K.S was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG1188/3-1) and the Edward P. Evans Foundation. D. H. was supported by the German Cancer Aid. Whole-exome sequencing was supported in part by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Spain (PI 11/02010), by Red de Investigación Cooperativa en Cancer (RTICC, FEDER; RD12/0036/0044), 2014 SGR 225 GRE (Generalitat de Catalunya) and Celgene Spain. We sincerely acknowledge Lourdes Florensa, Leonor Arenillas, Maria Consuelo del Cañizo, Maria Diez-Campelo, Lurdes Zamora and Laura Palomo, for their implication on the project and selection of the patients and CNAG (Centro Nacional de Analisis Genomicos) for whole-exome sequencing studies.

Footnotes

Accession number

The Gene Expression Omnibus accession number for SNP-arrays is GSE59244.

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, 5 figures, 1 table.

Authorship Contributions:

R.K.S, D.H., M.J. and B.L.E. designed experiments. R.K.S, D.H., A.M.L, L.P.C., M.E.M., A.M. and R.K. performed experiments and analyzed data. V.A., M.M., R.B. and F.S. collected patient samples and clinical information, performed whole exome sequencing, validation by Sanger sequencing and analyzed these data. R.K.S and B.L.E. wrote the manuscript. All authors provided critical review of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albuquerque C, Breukel C, van der Luijt R, Fidalgo P, Lage P, Slors FJ, Leitao CN, Fodde R, Smits R. The ‘just-right’ signaling model: APC somatic mutations are selected based on a specific level of activation of the beta-catenin signaling cascade. Human molecular genetics. 2002;11:1549–1560. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba Y, Garrett KP, Kincade PW. Constitutively active beta-catenin confers multilineage differentiation potential on lymphoid and myeloid progenitors. Immunity. 2005;23:599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidere N, Ngo VN, Lee J, Collins C, Zheng L, Wan F, Davis RE, Lenz G, Anderson DE, Arnoult D, et al. Casein kinase 1alpha governs antigen-receptor-induced NF-kappaB activation and human lymphoma cell survival. Nature. 2009;458:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boultwood J, Pellagatti A, Cattan H, Lawrie CH, Giagounidis A, Malcovati L, Della Porta MG, Jadersten M, Killick S, Fidler C, et al. Gene expression profiling of CD34+ cells in patients with the 5q-syndrome. British journal of haematology. 2007;139:578–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boultwood J, Pellagatti A, McKenzie AN, Wainscoat JS. Advances in the 5q-syndrome. Blood. 2010;116:5803–5811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-273771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TH, Kambal A, Krysiak K, Walshauser MA, Raju G, Tibbitts JF, Walter MJ. Knockdown of Hspa9, a del(5q31.2) gene, results in a decrease in hematopoietic progenitors in mice. Blood. 2011;117:1530–1539. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-293167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong JK, Virshup DM. Casein kinase 1: Complexity in the family. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2011;43:465–469. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson G, Wu W, Shen J, Bilic J, Fenger U, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. Casein kinase 1 gamma couples Wnt receptor activation to cytoplasmic signal transduction. Nature. 2005;438:867–872. doi: 10.1038/nature04170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulak AM, Stojanov P, Peng S, Lawrence MS, Fox C, Stewart C, Bandla S, Imamura Y, Schumacher SE, Shefler E, et al. Exome and whole-genome sequencing of esophageal adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent driver events and mutational complexity. Nature genetics. 2013;45:478–486. doi: 10.1038/ng.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutt S, Narla A, Lin K, Mullally A, Abayasekara N, Megerdichian C, Wilson FH, Currie T, Khanna-Gupta A, Berliner N, et al. Haploinsufficiency for ribosomal protein genes causes selective activation of p53 in human erythroid progenitor cells. Blood. 2011;117:2567–2576. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert BL. Molecular dissection of the 5q deletion in myelodysplastic syndrome. Seminars in oncology. 2011;38:621–626. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert BL, Pretz J, Bosco J, Chang CY, Tamayo P, Galili N, Raza A, Root DE, Attar E, Ellis SR, Golub TR. Identification of RPS14 as a 5q-syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature. 2008;451:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature06494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elyada E, Pribluda A, Goldstein RE, Morgenstern Y, Brachya G, Cojocaru G, Snir-Alkalay I, Burstain I, Haffner-Krausz R, Jung S, et al. CKIalpha ablation highlights a critical role for p53 in invasiveness control. Nature. 2011;470:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature09673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondek LP, Tiu R, O’Keefe CL, Sekeres MA, Theil KS, Maciejewski JP. Chromosomal lesions and uniparental disomy detected by SNP arrays in MDS, MDS/MPD, and MDS-derived AML. Blood. 2008;111:1534–1542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubert TA, Payton MA, Shao J, Walgren RA, Monahan RS, Frater JL, Walshauser MA, Martin MG, Kasai Y, Walter MJ. Integrated genomic analysis implicates haploinsufficiency of multiple chromosome 5q31.2 genes in de novo myelodysplastic syndromes pathogenesis. PloS one. 2009;4:e4583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubert TA, Shen D, Ding L, Okeyo-Owuor T, Lunn CL, Shao J, Krysiak K, Harris CC, Koboldt DC, Larson DE, et al. Recurrent mutations in the U2AF1 splicing factor in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nature genetics. 2012;44:53–57. doi: 10.1038/ng.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase D, Germing U, Schanz J, Pfeilstocker M, Nosslinger T, Hildebrandt B, Kundgen A, Lubbert M, Kunzmann R, Giagounidis AA, et al. New insights into the prognostic impact of the karyotype in MDS and correlation with subtypes: evidence from a core dataset of 2124 patients. Blood. 2007;110:4385–4395. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasserjian RP, LeBeau MM, List AF, Bennett JM, Thiele J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. World Health Organization Press: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. Myelodysplastic syndrome with isolated del(5q) p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs S, Kulkarni RV, Bueso-Ramos CE, Levine RL, Loh ML, Li C, Neuberg D, Kornblau SM, Issa JP, Gilliland DG, et al. Accurate detection of uniparental disomy and microdeletions by SNP array analysis in myelodysplastic syndromes with normal cytogenetics. Leukemia. 2009;23:1605–1613. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaras M, Miller PG, Chu LP, Puram RV, Fink EC, Schneider RK, Al-Shahrour F, Pena P, Breyfogle LJ, Hartwell KA, et al. Csnk1a1 inhibition has p53-dependent therapeutic efficacy in acute myeloid leukemia. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211:605–612. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerez A, Gondek LP, Jankowska AM, Makishima H, Przychodzen B, Tiu RV, O’Keefe CL, Mohamedali AM, Batista D, Sekeres MA, et al. Topography, clinical, and genomic correlates of 5q myeloid malignancies revisited. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1343–1349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joslin JM, Fernald AA, Tennant TR, Davis EM, Kogan SC, Anastasi J, Crispino JD, Le Beau MM. Haploinsufficiency of EGR1, a candidate gene in the del(5q), leads to the development of myeloid disorders. Blood. 2007;110:719–726. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirstetter P, Anderson K, Porse BT, Jacobsen SE, Nerlov C. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway leads to loss of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation and multilineage differentiation block. Nature immunology. 2006;7:1048–1056. doi: 10.1038/ni1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome research. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kode A, Manavalan JS, Mosialou I, Bhagat G, Rathinam CV, Luo N, Khiabanian H, Lee A, Murty VV, Friedman R, et al. Leukaemogenesis induced by an activating beta-catenin mutation in osteoblasts. Nature. 2014;506:240–244. doi: 10.1038/nature12883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MS, Narla A, Nonami A, Mullally A, Dimitrova N, Ball B, McAuley JR, Poveromo L, Kutok JL, Galili N, et al. Coordinate loss of a microRNA and protein-coding gene cooperate in the pathogenesis of 5q-syndrome. Blood. 2011;118:4666–4673. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SW, Sykes SM, Al-Shahrour F, Shterental S, Paktinat M, Lo Celso C, Jesneck JL, Ebert BL, Williams DA, Gilliland DG. The Apc(min) mouse has altered hematopoietic stem cell function and provides a model for MPD/MDS. Blood. 2010;115:3489–3497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis TC, Ichii M, Brugman MH, Kincade P, Staal FJ. Wnt signaling strength regulates normal hematopoiesis and its deregulation is involved in leukemia development. Leukemia. 2012;26:414–421. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis TC, Naber BA, Roozen PP, Brugman MH, de Haas EF, Ghazvini M, Fibbe WE, van Dongen JJ, Fodde R, Staal FJ. Canonical wnt signaling regulates hematopoiesis in a dosage-dependent fashion. Cell stem cell. 2011;9:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallo M, Del Rey M, Ibanez M, Calasanz MJ, Arenillas L, Larrayoz MJ, Pedro C, Jerez A, Maciejewski J, Costa D, et al. Response to lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q): influence of cytogenetics and mutations. British journal of haematology. 2013;162:74–86. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PG, Al-Shahrour F, Hartwell KA, Chu LP, Jaras M, Puram RV, Puissant A, Callahan KP, Ashton J, McConkey ME, et al. In Vivo RNAi screening identifies a leukemia-specific dependence on integrin beta 3 signaling. Cancer cell. 2013;24:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min IM, Pietramaggiori G, Kim FS, Passegue E, Stevenson KE, Wagers AJ. The transcription factor EGR1 controls both the proliferation and localization of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2008;2:380–391. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan D, Zack TI, Ren Y, Strickland MR, Lamothe R, Schumacher SE, Tsherniak A, Besche HC, Rosenbluh J, Shehata S, et al. Cancer vulnerabilities unveiled by genomic loss. Cell. 2012;150:842–854. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, McKay RM, McKay JP, Graff JM. Casein kinase I transduces Wnt signals. Nature. 1999;401:345–350. doi: 10.1038/43830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rena G, Bain J, Elliott M, Cohen P. D4476, a cell-permeant inhibitor of CK1, suppresses the site-specific phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of FOXO1a. EMBO reports. 2004;5:60–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Yoshizato T, Shiraishi Y, Maekawa S, Okuno Y, Kamura T, Shimamura T, Sato-Otsubo A, Nagae G, Suzuki H, et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature genetics. 2013;45:860–867. doi: 10.1038/ng.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller M, Huelsken J, Rosenbauer F, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Tenen DG, Leutz A. Hematopoietic stem cell and multilineage defects generated by constitutive beta-catenin activation. Nature immunology. 2006;7:1037–1047. doi: 10.1038/ni1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnberg T, Menzel M, Kaesler S, Biedermann T, Sauer B, Nahnsen S, Schwarz M, Garbe C, Schittek B. Suppression of casein kinase 1alpha in melanoma cells induces a switch in beta-catenin signaling to promote metastasis. Cancer research. 2010;70:6999–7009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starczynowski DT, Kuchenbauer F, Argiropoulos B, Sung S, Morin R, Muranyi A, Hirst M, Hogge D, Marra M, Wells RA, et al. Identification of miR-145 and miR-146a as mediators of the 5q-syndrome phenotype. Nature medicine. 2010;16:49–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart A, Fernald AA, Wang J, Davis EM, Karrison T, Anastasi J, Le Beau MM. Haploinsufficiency of del(5q) genes, Egr1 and Apc, cooperate with Tp53 loss to induce acute myeloid leukemia in mice. Blood. 2013 doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-517953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge JJ, Xenocostas A, Moon RT, Bhatia M. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is an in vivo regulator of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation. Nature medicine. 2006;12:89–98. doi: 10.1038/nm1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkley CR, Olsen GH, Dworkin S, Fabb SA, Swann J, McArthur GA, Westmoreland SV, Chambon P, Scadden DT, Purton LE. A microenvironment-induced myeloproliferative syndrome caused by retinoic acid receptor gamma deficiency. Cell. 2007;129:1097–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fernald AA, Anastasi J, Le Beau MM, Qian Z. Haploinsufficiency of Apc leads to ineffective hematopoiesis. Blood. 2010a;115:3481–3488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Krivtsov AV, Sinha AU, North TE, Goessling W, Feng Z, Zon LI, Armstrong SA. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is required for the development of leukemia stem cells in AML. Science. 2010b;327:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1186624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, Yates JR, 3rd, Nusse R. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woll PS, Kjallquist U, Chowdhury O, Doolittle H, Wedge DC, Thongjuea S, Erlandsson R, Ngara M, Anderson K, Deng Q, et al. Myelodysplastic Syndromes Are Propagated by Rare and Distinct Human Cancer Stem Cells In Vivo. Cancer cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Chen L, Becker A, Schonbrunn E, Chen J. Casein kinase 1alpha regulates an MDMX intramolecular interaction to stimulate p53 binding. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32:4821–4832. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00851-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Suzuki M, Niwa Y, Hiraga J, Nagasaka T, Ito M, Nakamura S, Tomita A, Abe A, Kiyoi H, et al. Clinical significance of nuclear non-phosphorylated beta-catenin in acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. British journal of haematology. 2008;140:394–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung J, Esposito MT, Gandillet A, Zeisig BB, Griessinger E, Bonnet D, So CW. beta-Catenin mediates the establishment and drug resistance of MLL leukemic stem cells. Cancer cell. 2010;18:606–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Guo ZK, Jiang XX, Li H, Wang XY, Yao HY, Zhang Y, Mao N. A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse compact bone. Nature protocols. 2010;5:550–560. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Related to figure 1. Characterization of primary Mx1Cre+ mice.