Abstract

Background:

Trigger finger is a common disorder of upper extremity. Majority of the patients can be treated conservatively but some resistant cases eventually need surgery.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the results of percutaneous trigger finger release under local anesthesia.

Subjects and Methods:

This is a prospective study carried out from July 2005 to July 2010, 46 fingers in 46 patients (30 females and 16 males) were recruited from outpatient department having trigger finger for more than 6 months. All patients were operated under local anesthesia. All patients were followed for 6 months. The clinical results were evaluated in terms of pain, activity level and patient satisfaction.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Statistical analysis was limited to calculation of percentage of patients who had excellent, good and poor outcomes.

Results:

The results were excellent in 82.6% (38/46) patients, good in 13.0% (6/46) patients and poor in two 4.3% (2/46) patients respectively. Complete Pain relief was achieved in 82.6% (38/46) patients, partial pain relief in 13.0% (6/46) patients and no pain relief in 4.3% (2/46) patients just after surgery. There was no recurrence of triggering. Range of motion was preserved in all cases. There were no digital nerve or tendon injuries. On subjective evaluations, 82.6% (38/46) patients reported full satisfaction, 13.0% (6/46) patients partial satisfaction and 4.3% (2/46) patients dissatisfaction with the results of treatment respectively.

Conclusions:

Percutaneous trigger finger release under local anesthesia is a minimal invasive procedure that can be performed in an outpatient setting. This procedure is easy, quicker, less complications and economical with good results.

Keywords: Local anesthesia, Minimal invasive procedure, Percutaneous, Trigger finger

Introduction

Trigger finger is a common condition in clinical practice. It is generally characterized by pain, swelling, the limitation of finger motion and a triggering sensation.[1] It generally involves the thumb or index finger, but can be seen in any other finger.[1] The primary pathology is thickening of the A1 pulley with resultant entrapment of the flexor tendon, thus forming a triggering mechanism.[2] Of the two treatment methods, the success of conservative treatment is reported to be 50-92% in the literature. Steroid injection, anti-inflammatory drug use and splinting of the finger are among the conservative treatment measures.[3,4] When conservative treatment fails, we have a surgical option of releasing the A1 pulley, which has success rates reported up to 100%.[1] The reported complications of surgical release are: Infection, digital nerve injury, scar tenderness and joint contractures.[5] Percutaneous release was first performed in 1958 and success rates of up to 100% without any complications have been reported.[6] Nowadays, percutaneous A1 pulley release is the method of choice in patients unresponsive to conservative treatment, with the advantages of ease of application, low complication rates and high patient satisfaction.[7,8,9] The aim of this study is to evaluate the results of percutaneous trigger finger release under local anesthesia.

Subjects and Methods

This prospective study was carried out at Orthopedics department of M. M. Medical College from July 2005 to July 2010. It was approved by institutional medical ethics committee. A total of 46 fingers in 46 patients (16 males and 30 females) with trigger finger admitted to our institute were included in present study. A written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. All patients were followed for 6 months. The indications for surgery (A1 pulley release) were as follows: More than 6 months of persistent symptoms despite the aggressive conservative treatments, such as rest, drug therapy, splinting, physiotherapy and a history of more than three steroid injections for treatment and functional impairment at work and home. Cases were excluded if there had been previous surgery or other hand pathology such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis.

Percutaneous technique

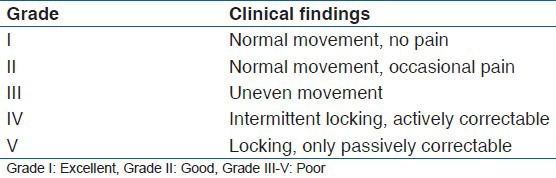

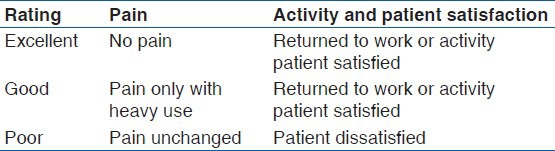

This percutaneous operative procedure was performed on an outpatient basis with use of local anesthesia. The patient was placed in supine position with the shoulder abducted by 45° so that the volar surface of the trigger fingers ‘faced the ceiling. Hand and wrist were placed on the pillow to extend the trigger finger. After cleaning and draping, a needle was inserted at a 1-2 mm of the distal portion from the metacarpophalangeal joint crease and the patient was administered 5 ml of 1% lidocaine. After the local anesthesia, a trigger finger could be hyperextended, which brought the flexor tendon sheath directly under the skin. An 18 gauge needle was inserted to the center of the metacarpophalangeal joint where was applied by a local anesthetic. The bevel of the needle needed to be parallel to the longitudinal axis of the flexor tendon and the location of needle was confirmed by a needle movement when the patient flexed and extended the distal phalanx. If the needle moved along with the finger's motion, the needle might be inserted into the flexor tendon, which was an incorrect location. The target structure to be inserted by a needle was not a flexor tendon but an A1 pulley. So, to make sure that the needle tip was placed in the Al pulley, the needle must be slowly withdrawn until its movement ceased. Then, moving the needle from the proximal portion to the distal portion of the longitudinal axis on the flexor tendon and getting a grating sensation, we could confirm the A1 pulley was located correctly below a needle. After confirming the location of the needle tip, the operator kept the needle moving for cutting the A1 pulley until there was no further grating sensation. The disappearing of the grating sensation indicated that the A1 pulley was being cut. Once the pulley has been released adequately, then the patient was asked to flex and extend the digit to confirm relief from the symptom of triggering. After the operation, a dressing was applied and the procedure site was compressed for 3 min to prevent hematoma. The patients were prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for 3 days. No complications, such as infection, digital artery, nerve injury, recurrence or stiffness of the operating site, were reported. These patients were followed-up weekly for a month and monthly for 6 months and graded according to Quinnell's criteria [Table 1].[10] During the last examination at 6 months, pain, activity level and patient satisfaction were evaluated [Table 2].[11] All cases were done by one surgeon in the duration of 5 years. The results were classified as satisfactory if the treated digit had no triggering and was comfortable and as unsatisfactory if there was persistent discomfort or if local steroid injection or if open surgery had been required. During the last examination pain, activity level and patient satisfaction were evaluated [Table 2].[11]

Table 1.

Severity of triggering according to the Quinnell grading system[10]

Table 2.

Rating system used to evaluate pain, activity and patient satisfaction

Results

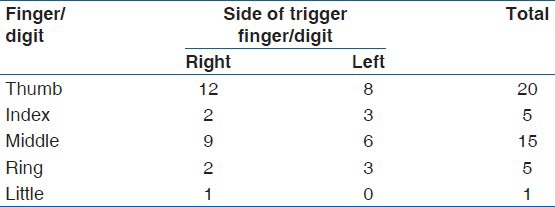

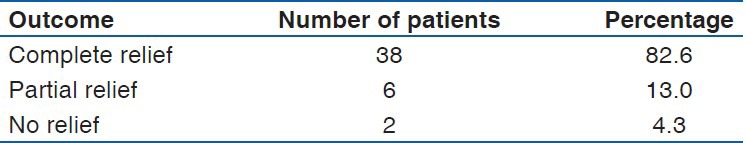

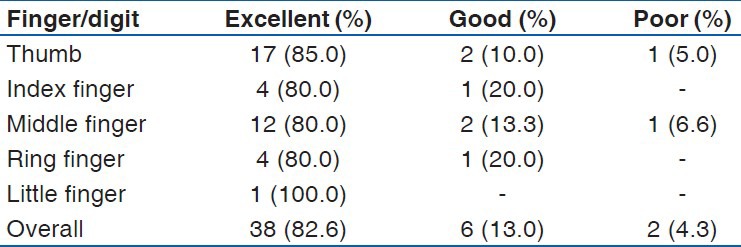

Out of 100% (46/46) patients, 65.2% (30/46) patients were women and 34.8% (16/46) patients were male respectively. All patients had unilateral trigger finger. Nearly 56.5% (26/46) cases of trigger finger were found on the right side and 43.5% (20/46) cases were seen on the left side [Table 3]. The mean age of patients was 52 years (range: 42-68 years). All patients were followed for 6 months. These patients were followed-up weekly for a month and monthly for 6 months and graded according to Quinnell's criteria [Table 1]. Nearly 82.6% (38/46) patients were of grade I, 13.0% (6/46) patients of grade II and 4.3% (2/46) patients were of grade III. At final follow-up examination pain, activity level and patient satisfaction were evaluated. The results were excellent in 82.6% (38/46) patients, good in 13.0% (6/46) patients and Poor results were encountered in 4.3% (2/46) patients. Complete Pain relief was achieved in 82.6% (38/46) patients, partial pain relief in 13.0% (6/46) patients and no pain relief in 4.3% (2/46) patients just after surgery respectively. We performed open release in these patients and verified that the release was incomplete. These releases were successful in these cases. Pain relief was achieved just after surgery. There was no recurrence of triggering. Range of motion was preserved in all cases. There were no digital nerve or tendon injuries. On subjective evaluations, 82.6% (38/46) patients reported full satisfaction, 13.0% (6/46) patient reported partial satisfaction and 4.3% (2/46) patients reported dissatisfaction with the results of treatment respectively. All were satisfied with the incision scar [Tables 4 and 5].

Table 3.

Distribution of fingers among patients (N=46)

Table 4.

Treatment outcome of (N=46)

Table 5.

Outcome of percutaneous trigger finger release as assessed by Quinnell grading system (N=46)

Discussion

One recent study in the Journal of Hand Surgery suggests that the most cost-effective treatment is two trials of corticosteroid injection, followed by open release of the first annular pulley.[12] The standard surgery is open surgical release of the tendon tunnel and is usually carried out under local anesthesia as a day case procedure. Open surgical division of the A1 annular pulley in the triggering digit has been the standard of treatment in protracted cases. However, complications after open release could be quite frequent and serious as previously reported by Thorpe[13] Scar tenderness, wound infection and finger stiffness are the potential complications. The percutaneous surgical release (PR) technique performed by Eastwood et al.,[14] as a convenient, cost-effective method with a low complication rate, is becoming more popular than open surgery.[14] The ones who suggest PR aim to decrease the complications that can be seen with open surgery, such as infections, painful scar formation, bowstringing of the flexor tendons due to pulley injuries, joint stiffness, weakness and digital artery or nerve damage. The percutaneous technique offers the advantage of being less invasive and therefore minimizes the risk of these problems. Previous reports confirmed these observations.[14,15] This is compared to a percutaneous needle release (100% success rate) and open release (100% success rate).[16] Our preliminary experience is encouraging and has confirmed the safety and effectiveness of the percutaneous technique. There was no digital nerve injury and no serious tendon injury resulted. All patients had complete resolution of their triggering symptoms without recurrence during the study period. We believe this is a potentially very useful technique and recommend continued study over its long-term effects. The following technical points, however, should be emphasized: (1) Always stay in the midline of the digit. This is especially true when operating on the thumb and index finger because the radial digital nerves run to within 3 mm of the midline, (2) make sure that the metacarpophalangeal joint is hyper extended so that the neurovascular bundles fall to the sides of the flexor tendons. This maneuver also brings the annular pulley closer to the skin; (3) keep the needle perpendicular to the finger in the sagittal plane. Failure to do so may easily cause the tip of the needle to tilt toward the radial or ulnar neurovascular bundles and cause injury; (4) use minimal amounts of local anesthetic (5 ml of 1% lidocaine). We now use only 0.5 ml of plain 1% lignocaine and have found less immediate post-operative numbness; (5). Be as accurate as possible with the position of the needle tip in relation to the tendon and pulley. The A1 pulley should be divided in one clean stroke. Multiple attempts make the procedure more difficult as the distal edge of the pulley becomes much less easily detectable. Avoid deep penetration of the flexor tendon by regularly moving the finger to check the depth of the needle. We believe when these guidelines are closely adhered to, the technique should be safe, effective and convenient to the patient. It offers obvious advantages to both the patient and the surgeon. In a study by Sato et al.[16] stated that the percutaneous and open surgery methods displayed similar effectiveness and proved superior to the conservative corticosteroid method regarding the trigger cure and relapse rates. Fiorini et al.[17] stated that the demarcation of the longitudinal axis of the tendon in the percutaneous technique and precise anatomical knowledge of the pulleys are important factors for preventing complications, which is similar to the conclusion reached in anatomical studies. Overall, published research studies do not favor any particular type of treatment for the resolution of trigger thumb. There is not sufficient scientific evidence to favor any particular type of treatment for a flexor tendinopathy. Non-operative treatment has been deemed highly successful in clinical practice and is preferable over surgery. Research efforts should focus on demonstrating the most cost-effective and minimal invasive treatment options for patients with a flexor tendinopathy. Percutaneous surgical technique under local anesthesia in the treatment of trigger finger appears to be a safe alternative to open surgery. We have shown the clinical success of the percutaneous technique in this study. It is a convenient, cost-effective method with a low complication rate, if performed carefully. The limitation of this study was that an analysis was not made based on a comparison with other methods of anesthesia and surgical techniques, which were mostly more difficult and costly than the present method. This study has fewer numbers of cases however this study presented satisfactory results of trigger finger. In our study, the results were excellent in 82.6% patients and good in 13.0% patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bonnici AV, Spencer JD. A survey of ‘trigger finger’ in adults. J Hand Surg Br. 1988;13:202–3. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_88_90139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampson SP, Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Seidman J. Pathobiology of the human A1 pulley in trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16:714–21. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(91)90200-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel MR, Bassini L. Trigger fingers and thumb: When to splint, inject, or operate. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17:110–3. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(92)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urbaniak JR, Roth JH. Office diagnosis and treatment of hand pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982;13:477–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrozzella J, Stern PJ, Von Kuster LC. Transection of radial digital nerve of the thumb during trigger release. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(89)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorthioir J., Jr Surgical treatment of trigger-finger by a subcutaneous method. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40-A:793–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumberg N, Arbel R, Dekel S. Percutaneous release of trigger digits. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:256–7. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2001.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragoowansi R, Acornley A, Khoo CT. Percutaneous trigger finger release: The ‘lift-cut’ technique. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:817–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park MJ, Oh I, Ha KI. A1 pulley release of locked trigger digit by percutaneous technique. J Hand Surg Br. 2004;29:502–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinnell RC. Conservative management of trigger finger. Practitioner. 1980;224:187–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grundberg AB, Dobson JF. Percutaneous release of the common extensor origin for tennis elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;376:137–40. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerrigan CL, Stanwix MG. Using evidence to minimize the cost of trigger finger care. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:997–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorpe AP. Results of surgery for trigger finger. J Hand Surg Br. 1988;13:199–201. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_88_90138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eastwood DM, Gupta KJ, Johnson DP. Percutaneous release of the trigger finger: An office procedure. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17:114–7. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(92)90125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka J, Muraji M, Negoro H, Yamashita H, Nakano T, Nakano K. Subcutaneous release of trigger thumb and fingers in 210 fingers. J Hand Surg Br. 1990;15:463–5. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(90)90091-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato ES, Gomes Dos Santos JB, Belloti JC, Albertoni WM, Faloppa F. Treatment of trigger finger: Randomized clinical trial comparing the methods of corticosteroid injection, percutaneous release and open surgery. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:93–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiorini HJ, Santos JB, Hirakawa CK, Sato ES, Faloppa F, Albertoni WM. Anatomical study of the A1 pulley: Length and location by means of cutaneous landmarks on the palmar surface. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:464–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]