Abstract

Background:

Chronic periodontitis is gaining increasing prominence as a potential influnce on systemic health. Time to conception has been recently investigated in relation to chronic periodontitis among Caucasians. The authors set out to replicate the study among Nigerian pregnant women.

Aim:

The etiology of many medical conditions have been linked with the state of the oral health and one of such is the time to conception (TTC) among women. This study was aimed to assess the effect of periodontitis on TTC.

Subjects and Methods:

A cross-sectional study in a hospital setting involving 58 fertility clinic attendees and 70 pregnant controls using the simplified oral hygiene index, community periodontal index (CPI) and matrix metalloproteinase-8 immunoassay. Statistical analysis used included Spearman's rank order correlation statistic, Z-statistic and logistic regression.

Results:

Good oral hygiene correlated with shorter TTC (<1 year) than fair oral hygiene, but not statistically significant. The odds of increased conception were higher with CPI (odds ratio [OR]: 0.482, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.259-0.895, P = 0.02), periodontitis risk (OR 0.157, 95% CI 0.041-0.600, P < 0.01) and age (OR 0.842, 95% CI 0.756-0.938, P < 0.01).

Conclusion:

Chronic periodontitis was positively associated with increased TTC in the present study. The authors are recommending that women in child bearing age should be encouraged to have regular preventive dental check-ups in order to maintain good oral and periodontal health.

Keywords: Fertility, Oral hygiene, Periodontitis, Time to conception

Introduction

Almost two decades ago, Offenbacher et al. in their study have reported possible links between chronic periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes.[1,2,3] Other potential links include cardiovascular events,[4] kidney disease,[5] endometriosis,[6] oral cancer,[7] erectile dysfunction,[8] low sperm count,[9] and increased time to conception (TTC)[10] have also been reported.

Explanations for the observed associations include a dose-response relationship between prostaglandin E-2, periodontal disease activity and decreasing birth weight.[2] Other explanations include endotoxins released from Gram-negative bacteria[11] and direct vascular endothelial infection by periodontal microorganisms.[12] Systemic exposure to oral bacteria through periodontitis releases inflammatory mediators capable of initiating or supporting atherosclerosis.[13]

The evidence to support a link between periodontitis and increased TTC is still emerging. “Low-grade systemic inflammation associated with periodontal disease”. may have a local effect within the endometrium.”[10] This position is corroborated by several studies.[14,15,16]

An association between chronic periodontitis and increased TTC among black women is worrisome.

Nigerian researchers have reported a possible link between poor oral hygiene and low sperm count.[17] However, the association between chronic periodontitis and increased TTC has not been reported among Nigerians hence the need for the present study.

Subjects and Methods

Ethics

The study satisfied the Helsinki declaration and received the approval of the institutional review board. It formed part of a series of multi-center studies on the association between the chronic periodontitis and fertility among Nigerians. Verbal informed consent was obtained from participants prior to inclusion in the study. Consecutive fertility clinic attendees and pregnant antenatal clinic (ANC) controls participated in the study.

Sampling

This is the first study of its kind in Nigeria therefore, prevalence figures were not available. This made it only practicable to adopt a convenience sampling technique of consecutive new patients registering for ANC and fertility clinics of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital.

Inclusions and exclusions

Inclusion criteria were being pregnant or attempting to get pregnant. Patients had to be clinically healthy to be included. Patients on fertility medications and those who got pregnant through fertility medications were included, but under fertility clinic attendees. Further exclusions were not considered. Fertility was based on gravidity rather than parity, which means that a woman who suffered an abortion would still have been considered fertile despite not having a baby.

In order to eliminate inadequate copulation as a confounder, a history of regular sexual intercourse was important before being classified as infertile or non-pregnant.

Using pre-tested, closed-ended examiner-administered questionnaires, data on age, past dental visit, oral hygiene practice and smoking status were obtained. Others included TTC among pregnant women and time since trying for pregnancy among yet-to-conceive women (tetrodotoxin [TTX]) were obtained.

Periodontal examination was performed under natural illumination and parameters including oral hygiene index score (OHIS), community periodontal index (CPI) and periodontitis risk score using matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) (neutrophil collagenase-2). The kit works on the principle of lateral flow immunoassay. Lateral flow immunoassay which predictively reveals periodontal inflammation, existing or hidden ones and is associated with clinical signs of periodontal tissue destruction.[18] MMP-8 immunoassay also predicts successful treatment outcomes.[19,20,21]

A previous report[18] stated that this immunoassay kit is “96% sensitive for poor oral hygiene, 95% sensitive for chronic periodontitis and 82.6% sensitive for bleeding on probing.”

The immunoassay test was performed using a simple mouthrinse previously approved by the institutional review board. Based the immunoassay results, patients were grouped either as a three-tier “high risk,” “low risk” and “no risk” group or a two-tier “no risk” and “risk” group. The classification was based on the depth of color change. Obtained OHIS results were classified as either good, fair or poor “Good” (0-1.2), “Fair” (1.3-3.0) and “Poor” (3.1-6.0).[22] The result of the rapid periodontitis risk immunoassay was read-off as color change.

Statistical analysis

TTC was recoded into two groups - <1 year and >1 year. Though a continuous variable, TTC was so grouped in consonance with acceptable standards for infertility. A woman is not considered infertile until after 1-year of unprotected sexual intercourse with their male spouse. OHIS was recoded into good (0-1.2), fair (1.3-3.0) and poor (>3.1). Data were analyzed using software package used for statistical analysis (SPSS version 18 (PASW statistics, IBM). Preliminary analysis performed to assess associations between groups using the Chi-square statistic, Z statistic and risk analysis. An attempt to further explore the strength of associations between the oral hygiene and TTC was made using Pearson's correlation statistics. However, not all variables were normally distributed among pregnant ANC attendees as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (P < 0.05). A Spearman's rank order correlation statistic was therefore performed as a non-parametric alternative after preliminary analysis showed the relationship to be monotonic. For the same reasons, a Spearman's rank order correlation test was performed as a non-parametric alternative to assess the relationship between OHIS and TTX. Age-matched comparisons were performed between the non-pregnant fertility clinic attendees and their pregnant controls using the Z statistic.

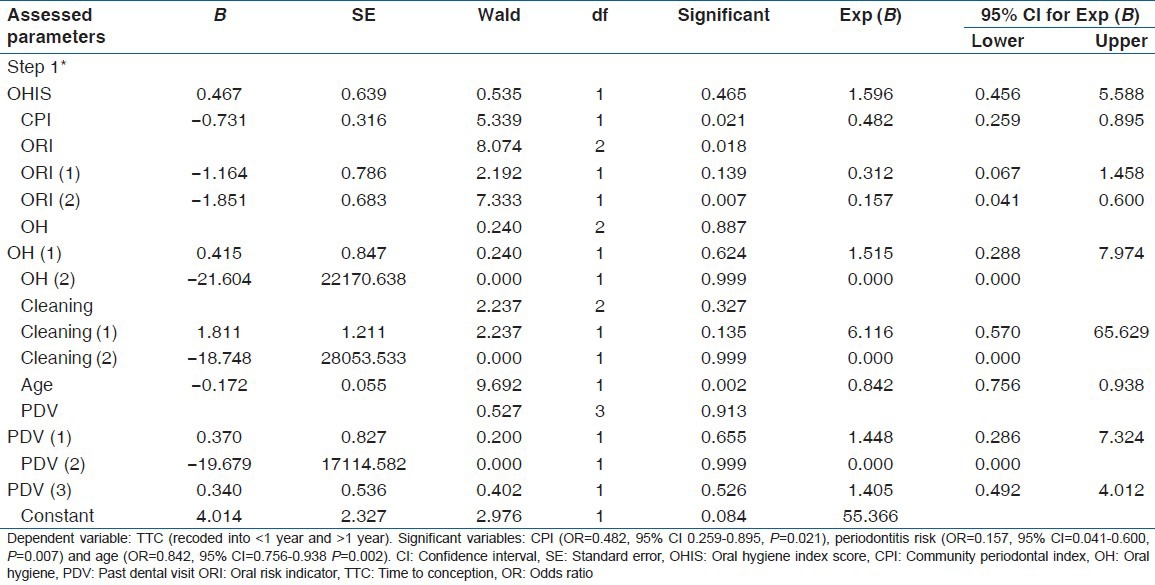

Since the relative contribution of the various independent variables to the occurrence of the dependent variable (TTC) was inconclusive in most instances, a logistic regression was performed. This incorporated six explanatory variables namely age, frequency of dental visit, oral hygiene index, oral hygiene practice, CPI score and periodontitis risk indicator (oral risk indicator). The logistic regression model to evaluate the likelihood that participants have increased TTC (>1 year) was statistically significant, χ2 (12) =40.862, P < 0.0015, explained 38.3% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in TTC and correctly classified 75.6% of cases. The sensitivity of the model was 66.7%, specificity was 81.3%, positive predictive value was 69.6% and negative predictive value was 79.2% respectively.

Results

A total of 128 women aged range from 23 to 48 years (mean age = 33.9 [5.04]) participated in this study. The number comprised of 70 pregnant ANC attendees (mean age = 32.8 [4.81]) and 58 non-pregnant fertility clinic attendees (mean age = 35.3 [5.00]).

TTC and oral hygiene

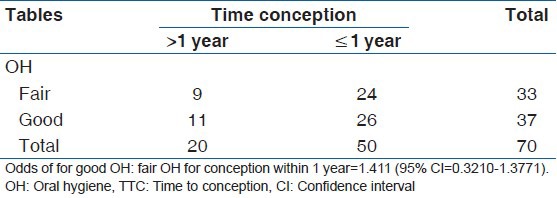

Overall, the association between oral hygiene and TTC was not significant (P = 0.09). Despite this, further analysis was conducted to determine if associations existed with smaller subgroups. The odds of conception within 1 year was greater in participants with good oral hygiene (odds ratio [OR]: 0.79, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3210-1.3771) than fair oral hygiene (OR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.3210-1.3771). The association translates approximately to 44% versus 36%, which failed to achieve statistical significance (Z statistic = 1.099, P = 0.27). There was also a weak positive correlation between oral hygiene and TTC among pregnant ANC attendees albeit insignificant (rs[69] =0.201, P = 0.09) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Association between OH and TTC (rs (69)=0.201, P>0.05)

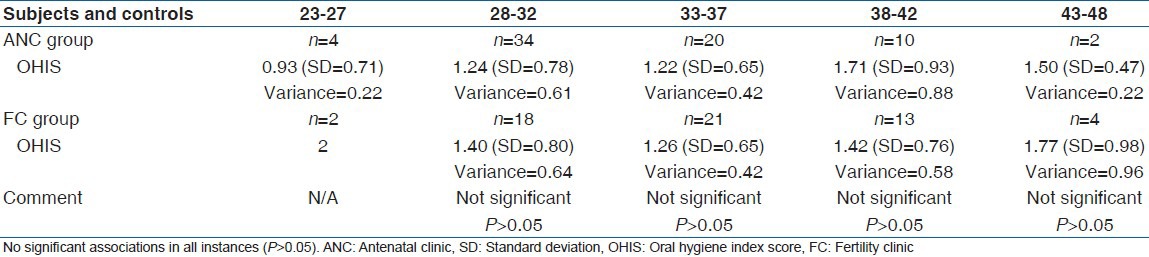

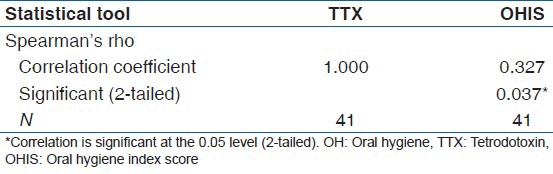

A Students’ t-test and age-matched Z-statistic found no significant differences in oral hygiene scores between test and control groups (Z statistic = −0.6124) [Table 2]. However, a moderate, but significant positive correlation between oral hygiene and waiting time without pregnancy existed (TTX) (rs[39] =0. 327, P = 0.04) [Table 3].

Table 2.

Age-matched evaluation between pregnant ANC attendees and non-pregnant FC attendees

Table 3.

Association between OH and waiting time without pregnancy (TTX) (rs (39)=0.327, P=0.037)

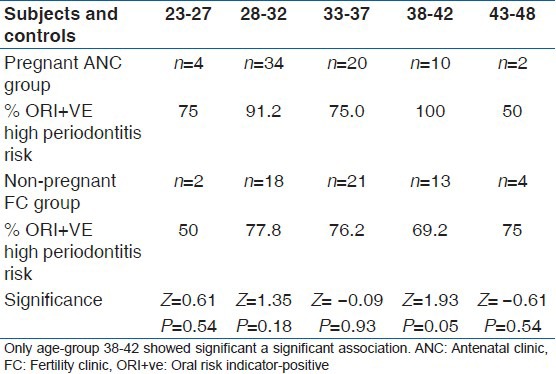

TTC and periodontitis

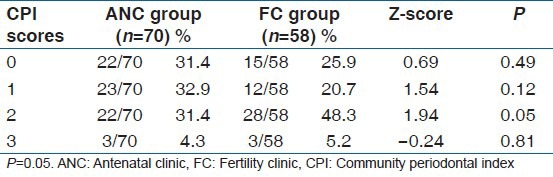

Initial MMP-8 immunoassay results showed no significant differences between the two groups except in the 38-42 year old age group [Table 4]. Only CPI score 2 (calculus) differed significantly between both groups. Non-pregnant fertility clinic attendees had significantly more calculus deposits than their pregnant counterparts [Table 5].

Table 4.

Age-matched Z statistic for comparisons of periodontitis risk between pregnant (ANC) and non-pregnant FC groups

Table 5.

Comparisons of CPI scores between pregnant (ANC) and non-pregnant FC groups showed significantly more calculus deposits in the non-pregnant FC group

Oral hygiene and periodontitis logistic regression

After logistic regression analysis, oral hygiene remained irrelevant to TTC (P = 0.47). The odds of increased TTC were higher with CPI (OR: 0.482, P = 0.02), periodontitis risk (OR: 0.157, P < 0.01) and age (OR: 0.842, P < 0.01) [Table 6].

Table 6.

Binary logistic regression analysis

Discussion

The study was aimed to explore the association between the chronic periodontitis and TTC. The main assessment tool for periodontitis has been described as “an effective tool in the diagnosis and monitoring of active periodontal diseases.”[23,24] Considerations of periodontitis experience among pregnant fertility clinic attendees would have been sufficient for evaluation. Most of the analysis was therefore considered separately for ANC attendees and non-pregnant fertility clinic attendees.

Within the limits of a cross-sectional, case-control study compared with the pioneer study[10] in this area, the results are quite disturbing and call for further evaluation in a larger sample of Africans. Unlike a recent Nigerian study[17] which reported a statistically significant association between poor oral hygiene and low sperm count, the present study found no such associations. The closest observation included greater odds of conception within 1-year among women with good oral hygiene which failed to attain statistical significance (Z statistic = 1.099, P = 0.27). This observation, however, needs to be treated with caution due to the limited sample size.

Unfortunately, there is no basis for comparison with the pioneer work because it did not consider oral hygiene. Interestingly though, the popular media in quoting this work have alluded more to oral hygiene than chronic periodontitis actually evaluated in the study. Findings from oral hygiene evaluations should stimulate great concerns.

In the present study, oral hygiene significantly positively correlated with increasing waiting time among non-pregnant fertility clinic attendees albeit weakly (rs[39] =0. 327, P = 0.04) and there were statistically more fertility clinic attendees with calculus than pregnant controls. Direct associations between oral hygiene and fertility issues have only been reported among Nigerian males.[17] It is not clear how calculus deposits affect TTC since calculus is traditionally believed to be incapable of inducing inflammation without plaque. This position is now contested as evident from the statement “inability to clearly differentiate effects of calculus versus “plaque on calculus.”[25] Full explanations of these effects might still elusive until we can confidently differentiate these effects.

Assessment of periodontitis in the present study went beyond dependence on CPI code 3 which could be very limited in its usefulness. The current study used a modern rapid chair-side MMP-8 immunoassay kit, which has proven sensitivity, specificity and good correlation with periodontal clinical parameters.[18] Initial analysis detected differences only in the 38-42 years age group. After regression analysis, periodontitis strongly associated with increased TTC (P < 0.01). This corroborates the pioneer study[10] only second to age as the most important predictor of TTC - again corroborating the pioneer study.[10]

A pertinent question to ask should be “how exactly does periodontitis affect fertility and TTC?” It is important to note that the pioneers of this observation never claimed or insinuated a causal relationship between periodontitis and infertility. They only, - as in the current study - reported an unexplained association. It has been suggested, however, that periodontitis affects TTC in a similar fashion to other inflammatory conditions such as endometriosis,[21] polycystic ovarian syndrome[16] and hydrosalpinges.[15] Periodontitis is believed to exert an “endometrial effect” as commonly reported in the literature[14,15,16,21] similar to these systemic inflammatory conditions. This explains a possible link between periodontitis and increased TTC as observed in the current study.

Conclusion

There were significant associations between TTC and age (P < 0.01), periodontitis (P < 0.01) assessed with a MMP-8 chair-side oral rinse.

Recommendations

The authors recommend that women in child bearing age should be encouraged to have regular preventive dental check-ups in order to maintain good oral and periodontal health

This study lacks the power to establish a causal link between chronic periodontitis and prolonged TTC but warrants a need for periodontal consultation in women trying to conceive.

Limitations

Limitations to studies like the current one often involves the difficulty of ruling out all possible confounders. Such confounders include factors unrelated to the studied group such as low sperm count in the spouse. However, patients attending fertility clinic would usually have gone through a screening stage to rule out spouse-associated problems before commencement of fertility treatment.

Another apparent limitation of this study is the use of CPI code 3 and OHIS. It is noteworthy however, that OHIS measures oral hygiene (and not periodontal status) in this study. Also, CPI was only adjunctive to the use of the highly sensitive MMP-8 immunoassay which is “an effective tool in the diagnosis and monitoring of active periodontal diseases.”[23,24]

Average number of sex attempts was eliminated as a confounder by considering those “actively trying for pregnancy.”

The authors did not consider stress in this study. It is not clear how stress could have affected our findings.

Finally, previous abortions could have posed as confounders but confounder eliminated by basing TTC on gravidity rather than current pregnancy alone.

Definitions

rs in Spearman's rank order correlation = 1 for perfect positive and − 1 for perfect negative correlation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Offenbacher S, Katz V, Fertik G, Collins J, Boyd D, Maynor G, et al. Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1103–13. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Offenbacher S, Jared HL, O’Reilly PG, Wells SR, Salvi GE, Lawrence HP, et al. Potential pathogenic mechanisms of periodontitis associated pregnancy complications. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:233–50. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Offenbacher S, Lin D, Strauss R, McKaig R, Irving J, Barros SP, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy during pregnancy on periodontal status, biologic parameters, and pregnancy outcomes: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2006;77:2011–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flores MF, Montenegro MM, Furtado MV, Polanczyk CA, Rösing CK, Haas AN. Periodontal Status Affects C-Reactive Protein and Lipids in Stable Heart Disease Patients From a Tertiary Care Cardiovascular Clinic. J Periodontol. 2013 Jun 27; doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130255. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ismail G, Dumitriu HT, Dumitriu AS, Ismail FB. Periodontal disease: a covert source of inflammation in chronic kidney disease patients. Int J Nephrol 2013. 2013:515796. doi: 10.1155/2013/515796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavoussi SK, West BT, Taylor GW, Lebovic DI. Periodontal disease and endometriosis: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feller L, Altini M, Lemmer J. Inflammation in the context of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:887–92. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant WB, Sorenson M, Boucher BJ. Vitamin D deficiency may contribute to the explanation of the link between chronic periodontitis and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2353–4. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinger A, Hain B, Yaffe H, Schonberger O. Periodontal status of males attending an in vitro fertilization clinic. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:542–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart R, Doherty DA, Pennell CE, Newnham IA, Newnham JP. Periodontal disease: A potential modifiable risk factor limiting conception. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1332–42. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saini R, Saini S, Saini SR. Periodontitis: A risk for delivery of premature labor and low-birth-weight infants. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2010;1:40–2. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.71672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong IW. Infections and their role in atherosclerotic vascular disease. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(Suppl):7S–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhardwaj A, Bhardwaj SV. Periodontitis as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease with its treatment modalities: A review. J Mol Pathophysiol. 2012;1:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss G, Goldsmith LT, Taylor RN, Bellet D, Taylor HS. Inflammation in reproductive disorders. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:216–29. doi: 10.1177/1933719108330087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson N, van Voorst S, Sowter MC, Strandell A, Mol BW. Surgical treatment for tubal disease in women due to undergo in vitro fertilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002125. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002125.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart R, Norman R. Polycystic ovarian syndrome – Prognosis and outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20:751–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nwhator SO, Umeizudike KA, Ayanbadejo PO, Opeodu OI, Olamijulo JA, Sorsa T. Another reason for impeccable oral hygiene; oral hygiene-sperm count link. JCDP. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1542. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nwhator SO, Ayanbadejo PO, Umeizudike KA, Opeodu OI, Agbelusi GA, Olamijulo JA, et al. Clinical correlates of a lateral-flow immunoassay oral risk indicator. J Periodontol. 2014;85:188–94. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mäntylä P, Stenman M, Kinane D, Salo T, Suomalainen K, Tikanoja S, et al. Monitoring periodontal disease status in smokers and nonsmokers using a gingival crevicular fluid matrix metalloproteinase-8-specific chair-side test. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:503–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mäntylä P, Stenman M, Kinane DF, Tikanoja S, Luoto H, Salo T, et al. Gingival crevicular fluid collagenase-2 (MMP-8) test stick for chair-side monitoring of periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:436–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnhart K, Dunsmoor-Su R, Coutifaris C. Effect of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:1148–55. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. Oral hygiene index: A method for classifying oral hygiene status. J Am Dent Assoc. 1960;61:172–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Lindhe J, Kent RL, Okamoto H, Yoneyama T. Clinical risk indicators for periodontal attachm ent loss. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindhe J, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Progression of periodontal disease in adult subjects in the absence of periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:433–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White DJ. Dental calculus: Recent insights into occurrence, formation, prevention, removal and oral health effects of supragingival and subgingival deposits. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:508–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]