Abstract

Mycobacteriophages have provided numerous essential tools for mycobacterial genetics, including delivery systems for transposons, reporter genes, and allelic exchange substrates, and components for plasmid vectors and mutagenesis. Their genetically diverse genomes also reveal insights into the broader nature of the phage population and the evolutionary mechanisms that give rise to it. The substantial advances in our understanding of the biology of mycobacteriophages including a large collection of completely sequenced genomes indicates a rich potential for further contributions in tuberculosis genetics and beyond.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacteriophages are viruses that infect mycobacterial hosts including Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The first mycobacteriophages were isolated in the late 1940s using M. smegmatis as a host (1, 2), followed by isolation of phages that infect M. tuberculosis (3). The application of phages with distinct host preferences to typing clinical mycobacterial isolates was recognized, and numerous studies on mycobacteriophage typing were published over the subsequent 30 years (4–12). In the 1950s a variety of further investigations focusing on the biology of these phages and their potential applications were initiated including studies on generalized transduction (13), viral morphology (14, 15), lysogeny (16–20), transfection of phage DNA (21, 22), and other biochemical features (23–40). These early contributions provided a critical foundation for the further characterization and application of mycobacteriophages to tuberculosis research that emerged from them.

Prior to the mid-1990s, the lack of methods for efficient and reproducible introduction of DNA into mycobacteria—coupled with the lack of simple plasmid vectors—represented substantial impediments to the development of facile systems for genetic manipulation of M. tuberculosis and other mycobacteria (41). Bacteriophages played a critical role in overcoming these roadblocks, in part because of the ability to introduce phage DNA into M. smegmatis spheroplasts using strategies developed earlier for Streptomyces (42, 43) and because of the development of shuttle phasmids, which grow as phages in mycobacteria and as large plasmids in Escherichia coli (44, 45). These contributed to the development of methods for more efficient transfection and transformation, demonstration of genetically selectable systems, and general methods for gene transfer into mycobacteria (46–49).

In the early 1990s, the first complete genome sequence of a mycobacteriophage was described (50), followed by another dozen or so over the following decade (51–54). With the advancements in DNA sequence technologies and the development of integrated research and education programs in phage discovery and genomics (55–58), the number of sequenced mycobacteriophage genomes now exceeds 500. These show substantial degrees of both genetic diversity and genetic novelty, providing insights into viral evolution and greatly expanding the potential for developing additional tools for mycobacterial genetics and for gaining insights into the physiology of their hosts (59–61).

In this chapter I review our current understanding of mycobacteriophages including their genetic diversity and applications for tuberculosis genetics. The focus will primarily be on recent developments, and there are a number of other reviews that the reader may find useful (18, 59, 60, 62–78).

GENERAL ASPECTS OF MYCOBACTERIOPHAGES

Mycobacteriophage Isolation

Bacteriophages can typically be isolated from any environment in which their bacterial host—or close relatives of their host—is present. There is no obvious reservoir of M. tuberculosis outside of its human host, but mycobacteriophages have been isolated from various patient samples including stool (79–81). However, because there are numerous saprophytic mycobacterial relatives, mycobacteriophages can be readily isolated from environmental samples such as soil or compost, using M. smegmatis or other nonpathogenic mycobacteria as hosts; a subset of these phages also infect M. tuberculosis (discussed further below). Phages can also be isolated by release from lysogenic host bacteria (82, 83), and phage genomic sequences can be identified in sequenced mycobacterial genomes (83–88).

M. smegmatis has proven to be a useful surrogate for phage isolation, using either direct plating from environmental samplesorbyenrichment, in which the sample is first incubated with M. smegmatis to promote amplification of phages for that host. Typically, direct plating yields only a small number of plaques from ~10% of the samples that are tested, whereas enrichment generates plaques from a higher proportion of samples, and the phage titers can be greater than 109 plaque forming units (pfu)/ml. Although enrichment might be anticipated to reduce the diversity of the phages isolated due to the potential growth advantages that a subset of phages might enjoy under these conditions, there is little evidence to support this with the mycobacteriophages. However, it does appear to alter the prevalence with which different phage types are recovered. For example, phages with one particular genome type (Cluster A; see below for details) represent over 40% of the phages recovered after enrichment, whereas they are only 25% isolated by direct plating. However, phages of a second genome type (Cluster B) are more prevalently recovered by direct plating (27%) than by enrichment (13%). But both of these general phage types themselves encompass considerable diversity and can be divided into several subtypes (i.e., subclusters), and enrichment also influences the abundance of particular subclusters. For example, phages of Subcluster A4 are relatively abundant in enriched samples (25% of the Cluster Aphages, and 10% of the total) relative to direct plating (10% of Cluster A phages and 1% of the total). However, these biases in isolation should be interpreted cautiously, because there are numerous influences on which particular phages are selected for sequencing and further characterization. Additional hosts including M. tuberculosis could be used for enrichment, although plating directly on M. tuberculosis lawns is challenging because of its slow growth and the propensity for growth of contaminants that increase the difficulty of identifying plaques.

All mycobacteriophages examined to date carry double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). No phages with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA genomes—or with virion morphologies other than the caudoviruses (see below)—have been described. It is plausible that they exist in these or other environments but that the isolation methods used to date bias against their growth and recovery. Phages with ssDNA or RNA genomes have been described for many other bacterial hosts, and it is somewhat surprising that none have been recovered for the mycobacteria. However, we note that this is also true for the phages described to date for all other species within the Actinomycetales.

Mycobacteriophage Virion Morphologies

The virion morphologies of many mycobacteriophages have been examined, and although three morphotypes of dsDNA tailed phages (Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae) have been described for other hosts, only phages with siphoviral and myoviral morphologies (with long, flexible, noncontractile tails and contractile tails, respectively) have been identified for the mycobacteria (Fig. 1). No podoviral morphotypes (with short stubby tails) have been described, and with several hundred phages examined microscopically, it seems likely that these are truly excluded from the mycobacteriophage population. Although this could result from evolutionary exclusion, the rampant horizontal genetic exchange common to bacteriophages would suggest that this is unlikely, and it is plausible that a physical barrier, such as the complex mycobacterial cell wall, prevents them from accessing the cell membrane for successful infection. This may also account for why phages other than the tailed dsDNA phages have yet to be discovered.

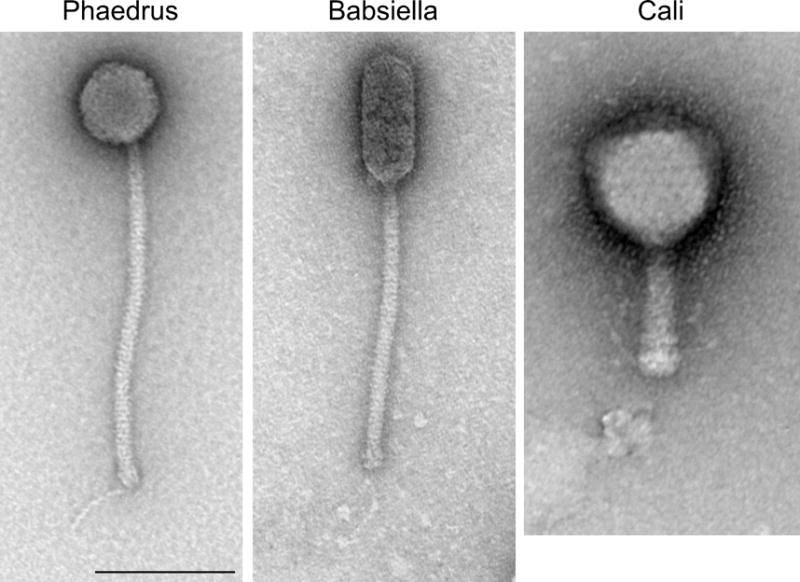

FIGURE 1.

Mycobacteriophage morphologies. Three examples of virion morphologies are illustrated. Phaedrus and Babsiella exhibit siphoviral morphologies with long flexible tails; Phaedrus has an isometric head, whereas the Babsiella head is prolate. Cali is an example of myoviral morphology. Scale bar is 100 nm. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0032-2013.f1

By far the majority (>90%) of mycobacteriophages have siphoviral morphologies with long flexible tails, and only ~8% have myoviral morphologies, all of which belong to a single genome type (Cluster C; see below). Most of the siphoviral morphotypes have isometric heads (varying in diameter from 50 to 80 nm), but a few have prolate heads with length:width ratio ranges from 2.5:1 to 4:1 (Fig. 1). There is substantial variation in tail length, ranging from 135 to 350 nm (89). The range in diameters of the isometric capsids—corresponding to differences in genome length—likely reflects different triangulation numbers in the capsid structures, but few have been determined experimentally. An electron micrograph–based reconstruction of mycobacteriophage Araucaria shows it has a T = 7 capsid symmetry (83), and a cryo-EM reconstruction of the phage BAKA capsid shows it has a T = 13 symmetry (90).

Phage Discovery and Genomics as an Integrated Research and Education Platform

Because phage genomes are relatively small, sequencing them is much less of a technological feat than it was 25 years ago. The chief limitation thus becomes the availability of phage isolates to sequence and characterize. In developing the Phage Hunters Integrating Research and Education (PHIRE) program at the University of Pittsburgh, this research mission (i.e., discovering and genomically characterizing new mycobacteriophages) is paired with a mission in science education, specifically to develop programs that introduce young students (high school and undergraduate students) to authentic scientific research (55–58). The success of this program fueled implementation of a nationwide research course for freshman undergraduate students in collaboration with the Science Education Alliance (SEA) program of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The SEA Phage Hunters Advancing Genomic and Evolutionary Science (SEA-PHAGES) initiative began in 2008 and has involved over 4,000 undergraduate students at over 70 institutions ranging from R1 research universities to primarily undergraduate teaching colleges. The research accomplishments of the PHIRE and SEA-PHAGES programs are reflected in the massive increase in the number of completely sequenced mycobacteriophage genomes, growing from fewer than 20 to more than 500 in a 10-year span (www.phagesdb.org). The impact on science education is indicated by numerous parameters including student surveys such as the Classroom Undergraduate Research Experience (CURE) instrument (91).

Successful implementation of the PHIRE and SEA-PHAGES programs is predicated on a suite of features that characterize phage discovery and genomics. The enormous diversity of the phage population stacks the deck in favor of individual phage hunters isolating a phage with novel features, in some instances being completely unrelated to previously sequenced phages. This, however, is only apparent from the genomic characterization, because little or nothing can be learned about phage diversity and evolution without the genomic sequence. Students name their phages following a non-systematic nomenclature that reflects the individualistic aspects of the phage genomes (see below). With over 500 completely sequenced genomes of phages isolated on M. smegmatis mc2155, the prospects of isolating a phage with a completely novel DNA sequence is greatly diminished, although it is still extremely rare to find two phages with identical or near-identical genomes. However, the diversity of phages isolated using other—but closely related—hosts is likely to be just as great, and it is easy to envisage that large collections of sequenced phage genomes using numerous hosts within the Actinomycetales are likely to substantially advance our understanding of viral evolution.

Seven additional attributes of the PHIRE program have been described that contribute to its productivity (55, 56). These are (i) technical simplicity in beginning the project, (ii) the lack of requirement for prior advanced conceptual understanding, (iii) flexibility in timing and implementation, (iv) multiple milestones for success, (v) a parallel project design with strong peer-mentoring opportunities and the potential to engage large numbers of students, (vi) authentic research leading to peer-reviewed publications, and (vii) project ownership that powerfully engages students in their own individual contributions. These attributes should be transferable to other research and education platforms, and there are several excellent examples (92–95).

MYCOBACTERIOPHAGE GENOMICS

At the time of writing, there are a total of 285 complete mycobacteriophage genomes available in GenBank, and we will focus on these in this chapter (Table 1). The total number of sequenced mycobacteriophages is larger—currently 531 (www.phagesdb.org)—and the outstanding genomes will be available in GenBank pending completion and review of the annotations. Of the 285, all except one were either isolated on M. smegmatis or are known to infect M. smegmatis. The single exception is DS6A (61), whose host preference is restricted to the M. tuberculosis complex (6, 24).

Table 1.

Sequenced mycobacteriophage genomes

| Phage | Cluster | Accession # | Length (bp) | GC % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aeneas | A1 | JQ809703 | 53684 | 63.6 |

| Bethlehem | A1 | AY500153 | 52250 | 63.2 |

| BillKnuckles | A1 | JN699000 | 51821 | 63.4 |

| BPBiebs31 | A1 | JF957057 | 53171 | 63.4 |

| Bruns | A1 | JN698998 | 53003 | 63.6 |

| Bxb1 | A1 | AF271693 | 50550 | 63.6 |

| DD5 | A1 | EU744252 | 51621 | 63.4 |

| Doom | A1 | JN153085 | 51421 | 63.8 |

| Dreamboat | A1 | JN660814 | 51083 | 63.9 |

| Euphoria | A1 | JN153086 | 53597 | 63.7 |

| Jasper | A1 | EU744251 | 50968 | 63.7 |

| JC27 | A1 | JF937099 | 52169 | 63.6 |

| KBG | A1 | EU744248 | 53572 | 63.6 |

| KSSJEB | A1 | JF937110 | 51381 | 63.6 |

| Kugel | A1 | JN699016 | 52379 | 63.8 |

| Lesedi | A1 | JF937100 | 50486 | 63.8 |

| Lockley | A1 | EU744249 | 51478 | 63.4 |

| Marcell | A1 | JX307705 | 49186 | 64.0 |

| MrGordo | A1 | JN020140 | 50988 | 63.8 |

| Museum | A1 | JF937103 | 51426 | 63.6 |

| PattyP | A1 | KC661273 | 52057 | 63.6 |

| Perseus | A1 | JN572689 | 53142 | 63.7 |

| RidgeCB | A1 | JN398369 | 50844 | 64.0 |

| SarFire | A1 | KF024726 | 53701 | 63.8 |

| SkiPole | A1 | GU247132 | 53137 | 63.6 |

| Solon | A1 | EU826470 | 49487 | 63.8 |

| Switzer | A1 | JF937108 | 52298 | 63.8 |

| Trouble | A1 | KF024724 | 52102 | 63.6 |

| U2 | A1 | AY500152 | 51277 | 63.7 |

| Violet | A1 | JN687951 | 52481 | 63.8 |

| Che12 | A2 | DQ398043 | 52047 | 62.9 |

| D29 | A2 | AF022214 | 49136 | 63.5 |

| L5 | A2 | Z18946 | 52297 | 62.3 |

| Odin | A2 | KF017927 | 52807 | 62.3 |

| Pukovnik | A2 | EU744250 | 52892 | 63.3 |

| RedRock | A2 | GU339467 | 53332 | 64.5 |

| Trixie | A2 | JN408461 | 53526 | 64.5 |

| Turbido | A2 | JN408460 | 53169 | 63.3 |

| Bxz2 | A3 | AY129332 | 50913 | 64.2 |

| HelDan | A3 | JF957058 | 50364 | 64.0 |

| JHC117 | A3 | JF704098 | 50877 | 64.0 |

| Jobu08 | A3 | KC661281 | 50679 | 64.0 |

| Methuselah | A3 | KC661272 | 50891 | 64.2 |

| Microwolf | A3 | JF704101 | 50864 | 64.0 |

| Rockstar | A3 | JF704111 | 47780 | 64.3 |

| Vix | A3 | JF704114 | 50963 | 64.0 |

| Arturo | A4 | JX307702 | 51500 | 64.1 |

| Backyardigan | A4 | JF704093 | 51308 | 63.7 |

| Dhanush | A4 | KC661271 | 51373 | 63.9 |

| Eagle | A4 | HM152766.1 | 51436 | 63.9 |

| Flux | A4 | JQ809701 | 51370 | 63.9 |

| ICleared | A4 | JQ896627 | 51440 | 63.9 |

| LHTSCC | A4 | JN699015 | 51813 | 63.9 |

| Medusa | A4 | KF024733 | 51384 | 63.9 |

| MeeZee | A4 | JN243856 | 51368 | 63.9 |

| Peaches | A4 | GQ303263.1 | 51376 | 63.9 |

| Sabertooth | A4 | JX307703 | 51377 | 63.9 |

| Shaka | A4 | JF792674 | 51369 | 63.9 |

| TiroTheta9 | A4 | JN561150 | 51367 | 63.9 |

| Wile | A4 | JN243857 | 51308 | 63.7 |

| Airmid | A5 | JN083853 | 51241 | 60.0 |

| Benedict | A5 | JN083852 | 51083 | 59.8 |

| Cuco | A5 | JN408459 | 50965 | 60.9 |

| ElTiger69 | A5 | JX042578 | 51505 | 59.8 |

| George | A5 | JF704107 | 51578 | 61.0 |

| LittleCherry | A5 | KF017001 | 50690 | 60.9 |

| Tiger | A5 | JQ684677 | 50332 | 60.7 |

| Blue7 | A6 | JN698999 | 52288 | 61.4 |

| DaVinci | A6 | JF937092 | 51547 | 61.5 |

| EricB | A6 | JN049605 | 51702 | 61.5 |

| Gladiator | A6 | JF704097 | 52213 | 61.4 |

| Hammer | A6 | JF937094 | 51889 | 61.3 |

| Jeffabunny | A6 | JN699019 | 48963 | 61.6 |

| HINdeR | A7 | KC661275 | 52617 | 62.8 |

| Timshel | A7 | JF957060 | 53278 | 63.1 |

| Astro | A8 | JX015524.1 | 52494 | 61.4 |

| Saintus | A8 | JN831654 | 49228 | 61.2 |

| Alma | A9 | JN699005 | 53177 | 62.5 |

| PackMan | A9 | JF704110 | 51339 | 62.6 |

| Goose | A10 | JX307704 | 50645 | 65.1 |

| Rebeuca | A10 | JX411619 | 51235 | 65.1 |

| Severus | A10 | KC661279 | 49894 | 64.4 |

| Twister | A10 | JQ512844 | 51094 | 65.0 |

| ABU | B1 | JF704091 | 68850 | 66.5 |

| Chah | B1 | FJ174694 | 68450 | 66.5 |

| Colbert | B1 | GQ303259.1 | 67774 | 66.5 |

| Fang | B1 | GU247133 | 68569 | 66.5 |

| Harvey | B1 | JF937095 | 68193 | 66.5 |

| Hertubise | B1 | JF937097 | 68675 | 66.4 |

| IsaacEli | B1 | JN698990 | 68839 | 66.5 |

| JacAttac | B1 | JN698989 | 68311 | 66.5 |

| Kikipoo | B1 | JN699017 | 68839 | 66.5 |

| KLucky39 | B1 | JF704099 | 68138 | 66.5 |

| Morgushi | B1 | JN638753 | 68307 | 66.4 |

| Murdoc | B1 | JN638752 | 68600 | 66.4 |

| Newman | B1 | KC691258 | 68598 | 66.5 |

| Oline | B1 | JN192463 | 68720 | 66.4 |

| Oosterbaan | B1 | JF704109 | 68735 | 66.5 |

| Orion | B1 | DQ398046 | 68427 | 66.5 |

| OSmaximus | B1 | JN006064 | 69118 | 66.3 |

| PG1 | B1 | AF547430 | 68999 | 66.5 |

| Phipps | B1 | JF704102 | 68293 | 66.5 |

| Puhltonio | B1 | GQ303264.1 | 68323 | 66.4 |

| Scoot17C | B1 | GU247134 | 68432 | 66.5 |

| SDcharge11 | B1 | KC661274 | 67702 | 66.5 |

| Serendipity | B1 | JN006063 | 68804 | 66.5 |

| ShiVal | B1 | KC576784 | 68355 | 66.5 |

| TallGrassMM | B1 | JN699010 | 68133 | 66.5 |

| Thora | B1 | JF957056 | 68839 | 66.5 |

| ThreeOh3D2 | B1 | JN699009 | 68992 | 66.5 |

| UncleHowie | B1 | GQ303266.1 | 68016 | 66.5 |

| Vista | B1 | JN699008 | 68494 | 66.5 |

| Vortex | B1 | JF704103 | 68346 | 66.5 |

| Yoshand | B1 | JF937109 | 68719 | 66.5 |

| Arbiter | B2 | JN618996 | 67169 | 68.9 |

| Ares | B2 | JN699004 | 67436 | 69.0 |

| Hedgerow | B2 | JN698991 | 67451 | 69.0 |

| Qyrzula | B2 | DQ398048 | 67188 | 68.9 |

| Rosebush | B2 | AY129334 | 67480 | 68.9 |

| Akoma | B3 | JN699006 | 68711 | 67.5 |

| Athena | B3 | JN699003 | 69409 | 67.5 |

| Daisy | B3 | JF704095 | 68245 | 67.6 |

| Gadjet | B3 | JN698992 | 67949 | 67.5 |

| Kamiyu | B3 | JN699018 | 68633 | 67.5 |

| Phaedrus | B3 | EU816589 | 68090 | 67.6 |

| Phlyer | B3 | FJ641182.1 | 69378 | 67.5 |

| Pipefish | B3 | DQ398049 | 69059 | 67.3 |

| ChrisnMich | B4 | JF704094 | 70428 | 69.1 |

| Cooper | B4 | DQ398044 | 70654 | 69.1 |

| KayaCho | B4 | KF024729 | 70838 | 70.0 |

| Nigel | B4 | EU770221 | 69904 | 68.3 |

| Stinger | B4 | JN699011 | 69641 | 68.6 |

| Zemanar | B4 | JF704104 | 71092 | 68.9 |

| Acadian | B5 | JN699007 | 69864 | 68.4 |

| Reprobate | B5 | KF024727 | 70120 | 68.3 |

| Alice | C1 | JF704092 | 153401 | 64.7 |

| ArcherS7 | C1 | KC748970 | 156558 | 64.7 |

| Astraea | C1 | KC691257 | 154872 | 64.7 |

| Ava3 | C1 | JQ911768 | 154466 | 64.8 |

| Breeniome | C1 | KF006817 | 154434 | 64.8 |

| Bxz1 | C1 | AY129337 | 156102 | 64.8 |

| Cali | C1 | EU826471 | 155372 | 64.7 |

| Catera | C1 | DQ398053 | 153766 | 64.7 |

| Dandelion | C1 | JN412588 | 157568 | 64.7 |

| Drazdys | C1 | JF704116 | 156281 | 64.7 |

| ET08 | C1 | GQ303260.1 | 155445 | 64.6 |

| Ghost | C1 | JF704096 | 155167 | 64.6 |

| Gizmo | C1 | KC748968 | 157482 | 64.6 |

| LinStu | C1 | JN412592 | 153882 | 64.8 |

| LRRHood | C1 | GQ303262.1 | 154349 | 64.7 |

| MoMoMixon | C1 | JN699626 | 154573 | 64.8 |

| Nappy | C1 | JN699627 | 156646 | 64.7 |

| Pio | C1 | JN699013 | 156758 | 64.8 |

| Pleione | C1 | JN624850 | 155586 | 64.7 |

| Rizal | C1 | EU826467 | 153894 | 64.7 |

| ScottMcG | C1 | EU826469 | 154017 | 64.8 |

| Sebata | C1 | JN204348 | 155286 | 64.8 |

| Shrimp | C1 | KF024734 | 155714 | 64.7 |

| Spud | C1 | EU826468 | 154906 | 64.8 |

| Wally | C1 | JN699625 | 155299 | 64.7 |

| Myrna | C2 | EU826466 | 164602 | 65.4 |

| Adjutor | D | EU676000 | 64511 | 59.9 |

| Butterscotch | D | FJ168660 | 64562 | 59.7 |

| Gumball | D | FJ168661 | 64807 | 59.6 |

| Nova | D | JN699014 | 65108 | 59.7 |

| PBI1 | D | DQ398047 | 64494 | 59.8 |

| PLot | D | DQ398051 | 64787 | 59.8 |

| SirHarley | D | JF937107 | 64791 | 59.6 |

| Troll4 | D | FJ168662 | 64618 | 59.6 |

| 244 | E | DQ398041 | 74483 | 63.4 |

| ABCat | E | KF188414 | 76131 | 63.0 |

| Bask21 | E | JF937091 | 74997 | 62.9 |

| Cjw1 | E | AY129331 | 75931 | 63.7 |

| Contagion | E | KF024732 | 74533 | 63.1 |

| Dumbo | E | KC691255 | 75736 | 63.0 |

| Elph10 | E | JN391441 | 74675 | 63.0 |

| Eureka | E | JN412590 | 76174 | 62.9 |

| Henry | E | JF937096 | 76049 | 63.0 |

| Kostya | E | EU816591 | 75811 | 63.5 |

| Lilac | E | JN382248 | 76260 | 63.0 |

| Murphy | E | KC748971 | 76179 | 62.9 |

| Phaux | E | KC748969 | 76479 | 62.9 |

| Phrux | E | KC661277 | 74711 | 63.1 |

| Porky | E | EU816588 | 76312 | 63.5 |

| Pumpkin | E | GQ303265.1 | 74491 | 63.0 |

| Rakim | E | JN006062 | 75706 | 62.9 |

| SirDuracell | E | JF937106 | 75793 | 62.9 |

| Toto | E | JN006061 | 75933 | 63.0 |

| Ardmore | F1 | GU060500 | 52141 | 61.5 |

| Bobi | F1 | KF114874 | 59179 | 61.7 |

| Boomer | F1 | EU816590 | 58037 | 61.1 |

| Che8 | F1 | AY129330 | 59471 | 61.3 |

| Daenerys | F1 | KF017005 | 58043 | 61.6 |

| DeadP | F1 | JN698996 | 56461 | 61.6 |

| DLane | F1 | JF937093 | 58899 | 61.9 |

| Dorothy | F1 | JX411620 | 58866 | 61.4 |

| DotProduct | F1 | JN859129 | 55363 | 61.8 |

| Drago | F1 | JN542517 | 54411 | 61.2 |

| Fruitloop | F1 | FJ174690 | 58471 | 61.8 |

| GUmbie | F1 | JN398368 | 57387 | 61.4 |

| Hamulus | F1 | KF024723 | 57155 | 61.8 |

| Ibhubesi | F1 | JF937098 | 55600 | 61.2 |

| Job42 | F1 | KC661280 | 59626 | 61.2 |

| Llij | F1 | DQ398045 | 56852 | 61.5 |

| Mozy | F1 | JF937102 | 57278 | 61.1 |

| Mutaforma13 | F1 | JN020142 | 57701 | 61.3 |

| Pacc40 | F1 | FJ174692 | 58554 | 61.3 |

| PMC | F1 | DQ398050 | 56692 | 61.4 |

| Ramsey | F1 | FJ174693 | 58578 | 61.2 |

| RockyHorror | F1 | JF704117 | 56719 | 61.1 |

| SG4 | F1 | JN699012 | 59016 | 61.9 |

| Shauna1 | F1 | JN020141 | 59315 | 61.7 |

| ShiLan | F1 | JN020143 | 59794 | 61.4 |

| SiSi | F1 | KC661278 | 56279 | 61.5 |

| Spartacus | F1 | JQ300538 | 61164 | 61.7 |

| Taj | F1 | JX121091 | 58550 | 61.9 |

| Tweety | F1 | EF536069 | 58692 | 61.7 |

| Velveteen | F1 | KF017004 | 54314 | 61.5 |

| Wee | F1 | HQ728524 | 59230 | 61.8 |

| Avani | F2 | JQ809702 | 54470 | 61.0 |

| Che9d | F2 | AY129336 | 56276 | 60.9 |

| Jabbawokkie | F2 | KF017003 | 55213 | 61.1 |

| Yoshi | F2 | JF704115 | 58714 | 61.0 |

| Angel | G | FJ973624 | 41441 | 66.7 |

| Avrafan | G | JN699002 | 41901 | 66.6 |

| BPs | G | EU568876 | 41901 | 66.6 |

| Halo | G | DQ398042 | 42289 | 66.7 |

| Hope | G | GQ303261.1 | 41901 | 66.6 |

| Liefie | G | JN412593 | 41650 | 66.8 |

| Konstantine | H1 | FJ174691 | 68952 | 57.4 |

| Predator | H1 | EU770222 | 70110 | 56.4 |

| Barnyard | H2 | AY129339 | 70797 | 57.5 |

| Babsiella | I1 | JN699001 | 48420 | 67.1 |

| Brujita | I1 | FJ168659 | 47057 | 66.8 |

| Island3 | I1 | HM152765 | 47287 | 66.8 |

| Che9c | I2 | AY129333 | 57050 | 65.4 |

| BAKA | J | JF937090 | 111688 | 60.7 |

| Courthouse | J | JN698997 | 110569 | 60.9 |

| LittleE | J | JF937101 | 109086 | 61.3 |

| Omega | J | AY129338 | 110865 | 61.4 |

| Optimus | J | JF957059 | 109270 | 60.8 |

| Redno2 | J | KF114875 | 108297 | 60.9 |

| Thibault | J | JN201525 | 106327 | 60.8 |

| Wanda | J | KF006818 | 109960 | 60.8 |

| Adephagia | K1 | JF704105 | 59646 | 66.6 |

| Anaya | K1 | JF704106 | 60835 | 66.4 |

| Angelica | K1 | HM152764 | 59598 | 66.4 |

| BarrelRoll | K1 | JN643714 | 59672 | 66.6 |

| CrimD | K1 | HM152767 | 59798 | 66.9 |

| JAWS | K1 | JN185608 | 59749 | 66.6 |

| TM4 | K2 | AF068845 | 52797 | 68.1 |

| MacnCheese | K3 | JX042579 | 61567 | 67.3 |

| Pixie | K3 | JF937104 | 61147 | 67.3 |

| Fionnbharth | K4 | JN831653 | 58076 | 68.0 |

| Larva | K5 | JN243855 | 62991 | 65.3 |

| JoeDirt | L1 | JF704108 | 74914 | 58.8 |

| LeBron | L1 | HM152763 | 73453 | 58.8 |

| UPIE | L1 | JF704113 | 73784 | 58.8 |

| Breezona | L2 | KC691254 | 76652 | 58.9 |

| Crossroads | L2 | KF024731 | 76129 | 58.9 |

| Faith1 | L2 | JF744988 | 75960 | 58.9 |

| Rumpelstiltskin | L2 | JN680858 | 69279 | 58.9 |

| Winky | L2 | KC661276 | 76653 | 58.9 |

| Whirlwind | L3 | KF024725 | 76050 | 59.3 |

| Bongo | M | JN699628 | 80228 | 61.6 |

| PegLeg | M | KC900379 | 80955 | 61.5 |

| Rey | M | JF937105 | 83724 | 60.9 |

| Butters | N | KC576783 | 41491 | 65.8 |

| Charlie | N | JN256079 | 43036 | 66.3 |

| Redi | N | JN624851 | 42594 | 66.1 |

| Catdawg | O | KF017002 | 72108 | 65.4 |

| Corndog | O | AY129335 | 69777 | 65.4 |

| Dylan | O | KF024730 | 69815 | 65.4 |

| Firecracker | O | JN698993 | 71341 | 65.5 |

| BigNuz | P | JN412591 | 48984 | 66.7 |

| Fishburne | P | KC691256 | 47109 | 67.3 |

| Jebeks | P | JN572061 | 45580 | 67.3 |

| Giles | Q | EU203571 | 53746 | 67.3 |

| Send513 | R | JF704112 | 71547 | 56.0 |

| Marvin | S | JF704100 | 65100 | 63.4 |

| Dori | Single | JN698995 | 64613 | 66.0 |

| DS6A | Single | JN698994 | 60588 | 68.4 |

| Muddy | Single | KF024728 | 48228 | 58.8 |

| Patience | Single | JN412589 | 70506 | 50.3 |

| Wildcat | Single | DQ398052 | 78296 | 57.2 |

Grouping of Mycobacteriophages into Clusters and Subclusters

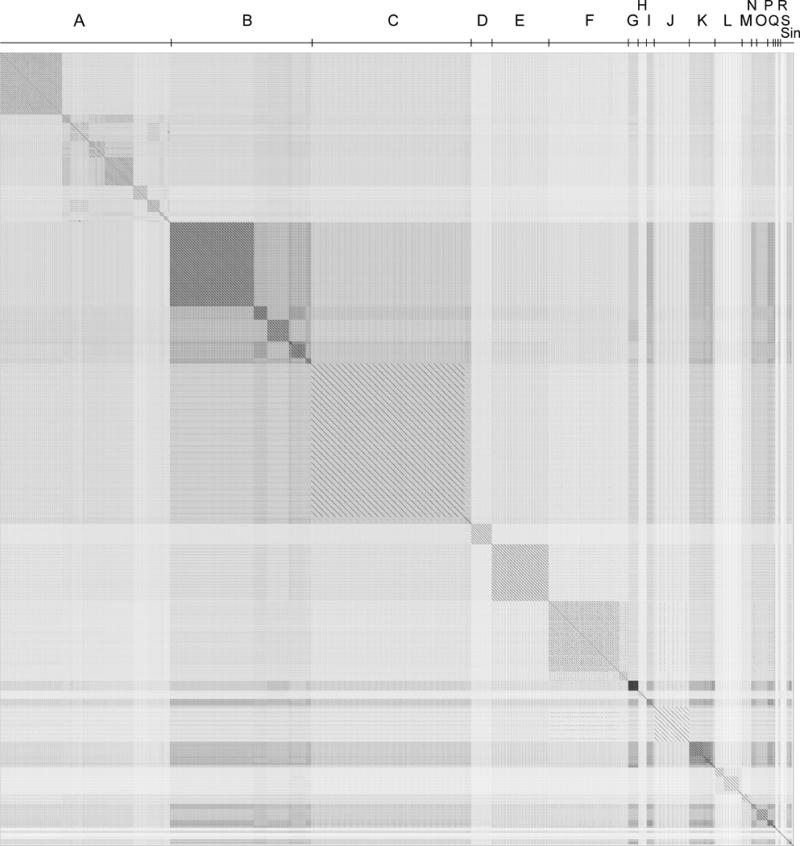

A simple dotplot comparison of the 285 genomes reveals an obvious feature of these genomes: that there is substantial diversity (i.e., many different types) but that the diversity is heterogeneous, and some phages are more closely related to each other than to others (Fig. 2). To recognize this heterogeneity and to simplify discussion, analysis, and presentation, these phages are assorted into groups called clusters (Cluster A, Cluster B, Cluster C, etc.), with the main criterion being that grouping of phages within a cluster requires recognizable nucleotide sequence similarity spanning over 50% of genome lengths with another phage in that cluster (56). Phages without any close relatives are referred to as singletons. For most phages, assignment to a cluster is simple, and extensive DNA sequence similarity is clear and apparent (see Fig. 3). However, assignment of phages to clusters is a taxonomy of convenience and does not reflect well-defined distinctions based on phylogeny or evolutionary relationships. Closer examination of sequence relationships reveals that they are mosaic and are constructed from segments swapped horizontally across the phage population (54, 96). This mosaicism is evident at both the DNA and the gene product levels and imposes challenges to some cluster assignments.

FIGURE 2.

Dotplot comparison of 285 mycobacteriophage genomes. A concatenated file of 285 mycobacteriophage nucleotide sequences was compared against itself using the Gepard program (242) to generate the dotplot. The order of the genomes was arranged such that genomically related phages were adjacent to each other in this file, and the clusters of related phages (Clusters A, B, C, etc.) are shown above the plot. Five of the genomes are singletons with no closely related phages and are denoted collectively as Sin. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0032-2013.f2

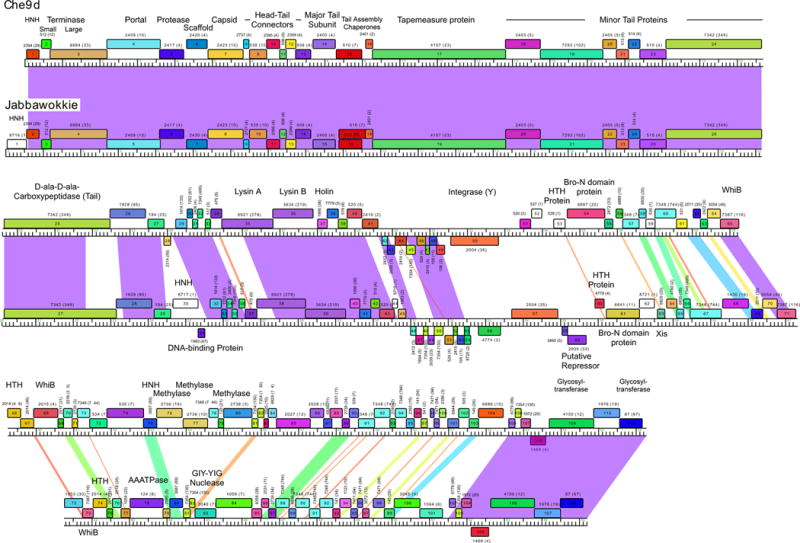

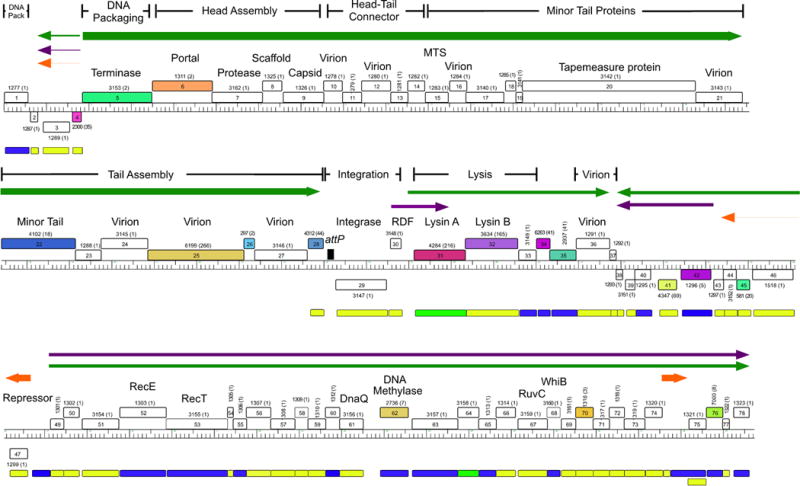

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of mycobacteriophage Che9d and Jabbawokkie genome maps. Mycobacteriophages Che9d and Jabbawokkie are grouped into Subcluster F2, and their genome maps are shown as represented by the Phamerator program (100). Each genome is shown with markers, and the shading between the genomes reflects nucleotide sequence similarity determined by BLASTN, spectrum-colored with the greatest similarity in purple and the least in red. Protein-coding genes are shown as colored boxes above or below the genomes, reflecting rightward or leftward transcription, respectively. Each gene is assigned a phamily (Pham) designation based on amino acid sequence similarity (see text), as shown above or below each box, with the number of phamily members shown in parentheses; genes shown as white boxes are orphams and have no other phamily members. Putative gene functions are indicated. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0032-2013.f3

Difficulties in cluster assignment have become more prevalent as the number of sequenced genomes has increased and generally fall into two categories. In the first, there are examples of genomes that are distantly related such that the nucleotide sequence similarity extends over substantial parts of the genomes but is sufficiently weak that it barely rises above the threshold levels of recognizable similarity, whether it is viewed by dotplot analysis or more quantitative methods. One example is phage Wildcat, which is currently classified as a singleton and although it has many similarities to the Cluster M phages, is not so closely related that it warrants inclusion in the cluster. A second conundrum arises from genomes that have segments of strong similarity to other phages, but over a span that either doesn’t convincingly meet the 50% threshold or spans more than 50% of one genome but not the other. An example is the inclusion of phage Che9c in Cluster I, where it belongs somewhat tenuously. Notwithstanding these caveats, the 285 genomes are grouped into 19 clusters (Clusters A to S) and five singleton genomes (Table 1).

Within some of these groupings, there is further heterogeneity in the degrees and extent of DNA sequence similarities. Thus, some of the clusters can be divided into subclusters, and the groupings are usually apparent by differences in the average nucleotide identity values (56, 89, 97, 98). However, the diversity varies from cluster to cluster, and thus the average nucleotide identity subcluster threshold values are not fixed and are relative to other members of the cluster. The subdivisions are usually apparent by dotplot comparison and, for example, the five subclusters within Cluster B can be easily seen in Fig. 2. Of the current 19 clusters, 9 are divided into subclusters, with the greatest division being the 10 subclusters within Cluster A (Table 1). The total number of different cluster-subcluster-singleton types is 47.

Assortment of Genes into Phamilies using Phamerator

An alternative representative of genome diversity is through gene content comparison (56, 89, 98, 99). This is accomplished with the program Phamerator (100), which sorts genes into phamilies (phams)—groups of genes in which each gene product has amino acid sequence similarity to at least one other phamily member above threshold levels (typically 32.5% amino acid identity or a BLASTP cutoff of less than 10−50) (100). Genomes can then be compared according to whether they do or do not have a member of each phamily. In a Phamerator database (Mycobacteriophage_285) generated with these 285 genomes there are a total of 3,435 phams, of which 1,322 (38%) are orphams, i.e., they contain only a single gene member. The relationships can be displayed using a network comparison in Splitstree (101) and in general show groupings of related phages that closely mirror the cluster designations from nucleotide sequence comparisons (56). It should be noted, however, that not all of the genes within the genomes necessarily have the same evolutionary histories—as a consequence of the mosaicism generated by horizontal genetic exchange—and thus these relationships only reflect the aggregate similarities and differences among the phages (56).

Comparative Genome Analysis

An especially informative representation of genome comparisons is by alignment of genome maps. These maps can be generated using Phamerator (100) and provide an overview of similarities at both the nucleotide and amino acid sequence levels (Fig. 3). Pairwise nucleotide sequence similarities are calculated using BLASTN, and values above a threshold level are displayed as colored shading between adjacent genomes in the display (Fig. 3); this is especially useful for identifying differences between genomes that have occurred in relatively recent evolutionary time. Because each gene is represented as a box colored according to its phamily membership, gene content comparisons and synteny also are displayed (Fig. 3).

Comparison of the genome maps of phages Che9d and Jabbawokkie—both members of Subcluster F2 (Table 1)—provides an informative illustration (Fig. 3). A large segment (~22 kbp) in the leftmost parts of the genomes (extending from the left ends through Che9d 25 and Jabbawokkie 27), encoding the virion structure and assembly genes, is extremely similar at the nucleotide sequence level (98% identity), as shown by the purple shading between the genomes in Fig. 3. The most obvious difference in this region is the insertion of an orpham (a gene that has no close mycobacteriophage relatives; i.e., it is the sole member of that pham) between the left physical end of the genome and a homing endonuclease (HNH) gene (Fig. 3), which is also predicted to encode an HNH endonuclease.

To the right of Che9d 25 and Jabbawokkie 27, there is another region of close similarity that extends to the left of the integrase genes and includes the lysis cassette (Fig. 3). Although there are several large interruptions in the alignment, the matching segments are closely related and vary between 90% and 100% nucleotide identity. Apart from the lysis genes and another HNH insertion in Jabbawokkie (gene 30), most of these genes are of unknown function. The entire right parts of the genomes (from ~31 kbp coordinates to the right physical ends) are much less closely related at the nucleotide sequence level, and many regions are sufficiently different that they are below the threshold for displaying any similarity; there are also many small segments of intermediate similarity and a block of closely related sequences (96% identity) at the right end. Another noteworthy feature is that some of the genes encode proteins of the same phamily even though there is little detectable nucleotide similarity. Perhaps the best example is the integrase genes (Che9d 50, Jabbawokkie 57; Fig. 3); the proteins share 45% amino acid identity but do not have recognizable DNA sequence similarity.

This comparison illustrates six general aspects of mycobacteriophage genomes. First, the genes are tightly packed and there is little noncoding space. Second, they are mosaic in their architecture, with different segments having different evolutionary histories (54, 96). Third, among those with siphoviral morphologies, the synteny of the virion structure and assembly genes is well conserved. Fourth, there are large numbers of genes of unknown function (56, 89, 98). Fifth, there is an abundance of small open reading frames, especially in the right parts of the genomes. Sixth, even where putative gene functions can be assigned, it is often unclear what their specific roles are (for example, why are there two whiB genes in Che9d, distantly related and sharing only ~25% amino acid sequence identity?).

Virion Structure and Assembly Genes

Phages with siphoviral morphologies (i.e., with a long flexible noncontractile tail)—including all mycobacteriophages except those in Cluster C—have a well-defined operon of virion structure and assembly genes in a syntenically well-conserved order. The genomes are typically represented, following the Lambda precedent, with these genes at the left end of the genome and transcribed rightward (see Fig. 3, 4, and 5). Sometimes this structural operon is situated such that the terminase genes at its left end are close to the physical ends of the genome, but there are many examples (e.g., Cluster A phages) where other genes are situated in this interval. Large subunit terminase genes can be readily identified in most of these phages, and many—but not all—have an identifiable small terminase subunit. The other virion structural genes typically follow in the order: terminase, portal, capsid maturation protease, scaffolding, capsid subunit, 4 to 6 head-tail connector proteins, major tail subunit, tail assembly chaperones, Tapemeasure protein, and 5 to 10 minor tail proteins.

FIGURE 4.

Functional genomics of mycobacteriophage Giles. A map of the mycobacteriophage Giles was generated using Phamerator and annotated as described for Fig. 3. Boxes below the genome indicate whether the gene is nonessential for lytic growth (yellow), likely essential (blue), or essential (green). Arrows indicate genes expressed in lysogeny (red) or early (green) or late (purple) lytic growth, with line thickness reflecting transcription strength. Reproduced with permission from Dedrick et al. (107). 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0032-2013.f4

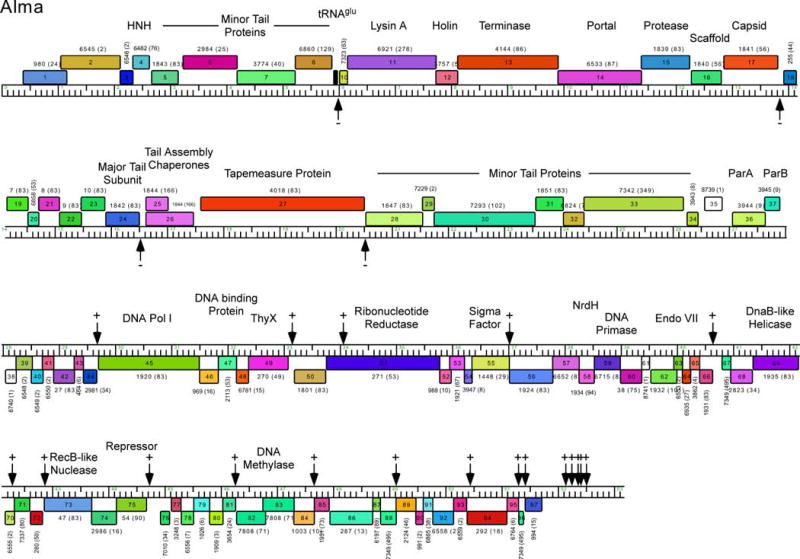

FIGURE 5.

Genome map of mycobacteriophage Alma. The genome map of mycobacteriophage Alma was generated using Phamerator and is illustrated as described for Fig. 3. Alma is a Subcluster A6 phage and shares the features of other Cluster A phages in having multiple binding sites for its repressor protein (gp75). These stoperator sites are indicated by vertical arrows, and the orientation of the asymmetric sites relative to genome orientation are shown as (−) or (+). Stoperators were identified as sequences corresponding to the consensus sequence 5′-GATGAGTGTCAAG with no more than a single mismatch. Note that the stoperator consensus sequences can differ for different Subcluster A phages (98). 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0032-2013.f5

Although the gene order is very well conserved, there is substantial sequence diversity, to the extent that genes conferring some of the specific functions cannot be predicted from their sequence alone, although their position is also informative. However, because it is relatively simple to characterize the virions themselves, by SDS-PAGE, N-terminal sequencing, or mass spectrometry, correlations between the structural genes and proteins can be readily determined (50, 53, 90, 102, 103). In general, these studies show that the major capsid and tail subunits are the most abundant and that in some phages (e.g., L5) the capsid subunit is extensively covalently cross-linked, similar to the well-studied phage HK97 (50, 104). A scaffold protein gene involved in head assembly is absent from some mycobacteriophages, although its function may be provided by a domain of the capsid subunit.

The Tapemeasure protein is simple to identify because it is typically encoded by the longest gene in the genome, and the two reading frames immediately upstream are expressed via a programmed translational frameshift (105). Although the sequences of the Tapemeasure proteins are very diverse, they often contain small conserved domains corresponding to peptidoglycan hydrolysis motifs (54). The precise roles for these is not clear, but in TM4 it has been shown that the motif is not required for phage assembly or growth, and removal of it results in a predictably shorter tail but also a reduction of its efficiency of infection of stationary phase cells (106). Following the tapemeasure gene are the minor tail protein genes encoding the proteins that constitute the tail tip structure. These are among some of the most diverse sequences in the mycobacteriophages, with many complex relationships, reflecting recombination and a mutational bias likely associated with host resistance. Many of the phages have a tail protein containing a D-Ala-D-Ala carboxypeptidase motif that presumably promotes infection through enzymatic modification or remodeling of the peptidoglycan. As described below, mutations conferring expanded host range also map to these minor tail protein genes (99).

Phages such as BPs and its Cluster G relatives have a compact virion structure and assembly operons with a total of 26 genes in a ~24-kbp span (103). At the opposite extreme, the Cluster J phages have a similar number of structural genes, but they span >30 kbp as a result of insertions of HNH endonucleases, introns, inteins (see below), and an assortment of other genes including those coding for methyltransferases and glycosyltransferases, whose roles are unknown. In Marvin, there is an unusual genome rearrangement in which a segment encoding several of the minor tail protein genes is displaced and sits among the nonstructural genes in the right part of the genome (102). The organizations of structural genes in the Cluster C phages with myoviral morphologies are much less well characterized.

Nonstructural Genes

The right parts of the genomes encoding nonstructural functions are characterized by an abundance of small open reading frames of unknown functions. They usually include a subset of genes whose functions can be bioinformatically predicted, and these are often associated with nucleotide metabolism or DNA replication. For example, some phages encode a DNA polymerase similar to E. coli DNA Polymerase I, whereas others encode alpha subunits of bacterial DNA Polymerase III. While it is simple to reason that these are involved in phage DNA replication, this has not been shown directly, and there are many mycobacteriophages that do not encode their own DNA polymerase at all. So why it would be needed in some phages but not in others is not clear. It is also common to find helicase and primase-like proteins, and sometimes recombination functions, including both recA and recET-like genes. In phage Giles, proteins of previously unknown function are implicated in DNA replication from mutagenesis studies (see Fig. 4) (107); D29 gp65—predicted to be part of the RecA/DnaB helicase superfamily—has been demonstrated to be an exonuclease (108). But overall, very little is known about the mechanics of regulation of DNA replication in mycobacteriophages or many of the possible genes that are involved.

Some of the nonstructural genes are cytotoxic and kill the host when expressed or overexpressed. This has been extensively characterized in staphylococcal phages (109), where it has been developed as part of a drug development pipeline, but several mycobacteriophage-encoded cytotoxic proteins have also been identified. Initially, segments of the phage L5 genome were shown to be not tolerated on plasmid vectors and could not be transformed into M. smegmatis (110). Further dissection showed that L5 genes 77, 78, and 79 all have cytotoxic properties, with 77 being the most potent (111). Interestingly, expression of L5 gp79 seems to specifically inhibit cell division of M. smegmatis and promote filamentation (111). L5 gp77 appears to act by interacting directly with Msmeg_3532, a pyridoxal- 5′-phosphate-dependent L-serine dehydratase that converts L-serine to pyruvate (112), although it is unclear what the consequences of the interaction are. The role of such an interaction in the growth of L5—or the many other Cluster A phages encoding homologues of L5 gp77—is unclear.

tRNA and tmRNA Genes

A considerable variety of tRNA gene repertoires are seen among the mycobacteriophages. Many of them do not appear to code for any tRNA genes at all, whereas others have dozens, close to a nearly complete coding set (54). But there are many intermediate variations, with some carrying just a single tRNA gene, and others with five or six. For example, many of the Cluster A phages carry one or more tRNA genes, but their specificities are quite varied. For example, just among the Subcluster A2 phages, L5 has three tRNA genes (tRNAAsn, tRNATrp, and tRNAGln) (50), and D29 contains these plus two more (tRNAGlu and tRNATyr) (52). But Turbido and Pukovnik have a single tRNAGln gene, Redrock has a single tRNATrp gene, and Trixie has both tRNATrp and tRNAGln genes. So while there have been several efforts to account for the specific roles of these genes in accommodating phage codon usage requirements (113–116), this variation suggests considerable complexity. It is plausible, for example, that many of them are “legacy genes” that may have been required for growth in a particular unknown host in their recent evolutionary past but play no role in the current host (see Fig. 6). Furthermore, there are examples of genes that appear to encode nonsense tRNAs as well as potential frame-shifting tRNAs, suggesting regulatory roles in gene expression. The Subcluster K1 phages all encode a single tRNA gene (tRNATrp) but also carry genes coding for a putative RNA ligase (RtcB), which could a play a role in repair of host-mediated attack of the tRNA (97).

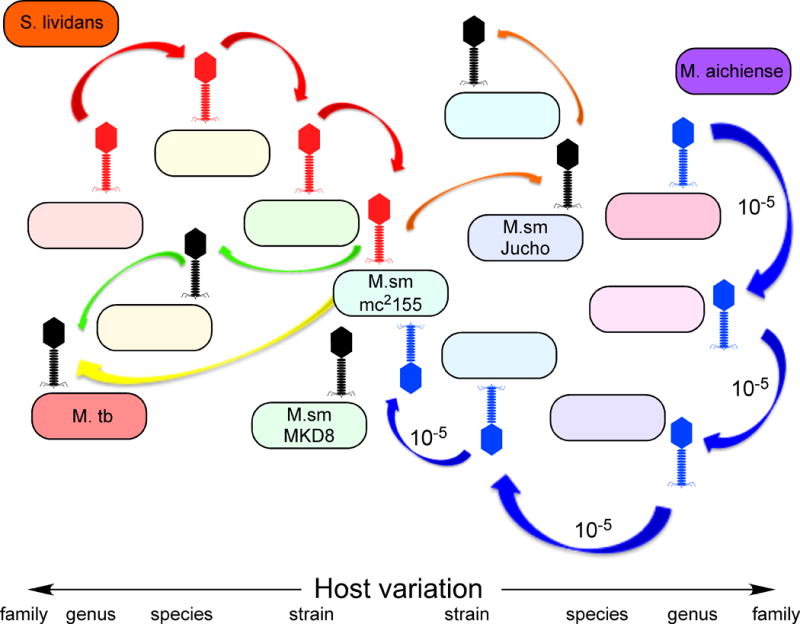

FIGURE 6.

A model for mycobacteriophage diversity. The large number of different types of mycobacteriophages isolated on M. smegmatis mc2155 can be explained by a model in which phages can readily infect new bacterial hosts—either by a switch or an expansion of host range—using a highly diverse bacterial population that includes many closely related strains. As such, phages with distinctly different genome sequences and GC% contents infecting distantly related bacterial hosts, such as those to the left (red) or right (blue) extremes of a spectrum of hosts, can migrate across a microbial landscape through multiple steps. Each host switch occurs at a relatively high frequency (~1 in 105 particles, or an average of about one every 103 bursts of lytic growth) and much faster than either amelioration of phage GC% to its new host or genetic recombination. Two phages (such as those shown in red and blue) can thus “arrive” at a common host (M. smegmatis mc2155) but be of distinctly different types (clusters, subclusters, and singletons). Reproduced with permission from Jacobs-Sera et al. (99). 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0032-2013.f6

Some phages (e.g., Cluster C) also encode a tmRNA gene, similar to host-encoded tmRNA genes that play a role in the release of ribosomes from broken mRNA. The specific roles of the phage-encoded tmRNAs are unclear, but it is plausible that they enhance the pool of free ribosomes for late gene expression by releasing them from early transcripts when they are no longer required.

Mobile Elements: Transposons, Introns, Inteins, and HNH Endonucleases

The key architectural feature of phage genomes—pervasive mosaicism—is likely generated by illegitimate recombination events that occur at regions of DNA sharing little or no DNA sequence similarity (96). Although most of these may result from replication or repair “accidents”, there are several active processes that could contribute, including transposition, intron and intein mobility, and HNH endonuclease activity.

A number of different transposable elements in mycobacterial genomes have been described, although these are generally not present in mycobacteriophage genomes. However, both active transposons and residual segments of transposons have been identified in the phages. Comparative analysis of the Cluster G phages provides compelling evidence for identification of novel ultra-small mycobacteriophage mobile elements (MPMEs), with two closely related subtypes, MPME1 and MPME2 (117). There are at least three instances in which an MPME insertion is present in one genome but absent from others, and because the Cluster G genomes are extremely similar to each other, the preintegration site and the precise insertion can be readily interpreted. The 439-bp MPME1 elements contain 11-bp imperfect inverted repeats (IRs) near their ends and a small (125-codon) open reading frame encoding a putative transposase. The MPME1 elements in phages BPs and Hope are 100% identical to each other (from IR-L to IR-R), but the insertions differ in a 6-bp segment between IR-L and the preintegration site. The origin of this 6-bp sequence is unclear but does not correspond to a target duplication (117).

MPME1 elements are found in a variety of other mycobacteriophage genomes including those in Clusters F and I and are either identical or have no more than a single base pair difference; there are also truncated versions of the element in the Cluster O phages (117). MPME2 elements are 1 base pair longer and share 79% nucleotide sequence identity to MPME1. They are present in the Cluster G phage Halo and phages within Clusters F, I, and N, being either identical to each other or having no more than a single base pair difference. As yet there is no direct evidence for the mobility of the MPME elements, the frequency of movement, or the mechanism involved, although the comparative genomics suggests that these are active and moving at a respectable rate. No MPME elements have been identified outside of the mycobacteriophages.

Comparative genomics also reveals an IS110-like element in phage Omega, which is absent from phage LittleE, and the genomes are sufficiently similar in these regions to indicate the preintegration site and a 5-bp target duplication (90). There are no closely related copies in other mycobacteriophages, but there are some more distantly related segments in some Subcluster A1 phages (90). It is unclear if this is a remnant or an active transposon.

There are few examples of self-splicing introns in the mycobacteriophages, but two have been recently described, both in Cluster J phages (90) and both within virion structural protein genes. In phage BAKA the intron is small (265 bp) and is within a putative tail protein gene; in phage LittleE the intron is within the capsid subunit gene and is larger (819 bp) due to inclusion of a small open reading frame on the opposite strand with similarities to homing endonucleases. Because both these proteins are required for virion assembly, and the capsid must be expressed at very high levels, the splicing events are expected to occur extremely efficiently. They are probably variants of group I introns, but little is known about their mechanisms of splicing (90). Other introns may be present in other genomes but have escaped detection because of insertion in genes of unknown function.

The rarity of self-splicing RNA introns contrasts with the relative abundance of inteins that splice out at the protein level. These are typically identifiable through conserved domains associated with intein splicing and are often apparent by comparative genomics. Phage ET08 has a total of five inteins—the most in any single mycobacteriophage genome to date (98). These are located within gp3, gp79, gp202, gp239, and gp248, but the functions of these are largely unknown, except for gp3, which is predicted to be a nucleotidyltransferase. For all five, there are examples of intein-less homologues in other phages. Most of the inteins contain an endonuclease domain that is predicted to promote DNA cleavage in intein-less genes followed by repair with the intein-containing DNA copy. The intein in Bethlehem gp51 has been dissected biochemically and shown to represent a new type (type III) of splicing mechanism (118), of which the Omega gp206 intein is an unusual variant (119).

It is common for mycobacteriophage genomes to have one or more putative HNH homing endonucleases encoded as freestanding genes (rather than as part of an intein or coded within an intron). These are usually recognized from the presence of conserved motifs, and none have yet been shown to have nuclease activity. However, a comparison of the freestanding HNH encoded by Courthouse gene 51 and phage Thibault, which lacks it, shows a precise insertion and the presumed location of endonucleolytic cleavage (90). A second example is an HNH insertion in Omega that is somewhat messier and when compared to phage Optimus, lacking the insertion, is associated with a loss of 35 bp, presumably during the process of HNH acquisition (90). While the specific mechanisms generating these events are not clear, it is not difficult to see how these could play important roles in generating genomic mosaicism during phage evolution.

MYCOBACTERIOPHAGE-HOST INTERACTIONS

Mycobacteriophage Host Range and Host Range Expansion

Considerable efforts in using mycobacteriophages for phage typing illustrate that they readily discern between different hosts and that by using panels of phages with defined host ranges, the identities of unknown hosts can be predicted (6). Unfortunately, for the most part the typing phages are no longer available, and the genomic information is lacking. However, the host ranges of a few sequenced phages have been examined and are informative in regard to understanding the genetic diversity of the phages. For example, Rybniker et al. (120) tested the host ranges of 14 mycobacteriophages and showed that L5 and D29 (both Subcluster A2 phages) as well as Bxz2 (Subcluster A3) have broad host ranges and infect M. tuberculosis, BCG, Mycobacterium scrofulaceum, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and some strains of both Mycobacterium ulcerans and Mycobacterium avium, in addition to M. smegmatis. Other phages have intermediate host preferences, such as phage Wildcat, which infects M. scrofulaceum, M. fortuitum, and M. chelonae, and some (e.g., Barnyard, Che8, Rosebush) infect only M. smegmatis or its substrains, out of the strains tested (120).

Jacobs-Sera et al. (99) determined whether a collection of 220 of the sequenced phages are able to infect M. tuberculosis. In general, there is a close correlation between the ability to infect M. tuberculosis and the cluster or subcluster type. For example, all of the Cluster K phages—regardless of subcluster—efficiently infect M. tuberculosis; among the Cluster A phages, only phages within specific subclusters can infect M. tuberculosis, including Subclusters A2 and A3. Interestingly, the Cluster G phages (e.g., BPs) do not efficiently infect M. tuberculosis, although mutants that do can be isolated at a frequency of ~10−5, and the mutants maintain the ability to infect M. smegmatis. Several of these mutants have been mapped, and all have single amino acid substitutions in gene 22, encoding a putative tail fiber protein (107, 117). A simple interpretation is that the mutants overcome the need for a specific interaction with receptors on the M. tuberculosis cell surface. However, adsorption assays suggest there is a more complex explanation, because the mutants do not appear to adsorb to M. tuberculosis more efficiently than the wild-type parent phage, and surprisingly, they adsorb substantially better to M. smegmatis, in some cases, dramatically so (99). This is not easy to explain, because the mutants appear to infect M. smegmatis quite normally and were selected for infection of M. tuberculosis.

The same set of phages was also tested for their ability to infect two other strains of M. smegmatis (99). Many, but not all, of the phages efficiently infect these strains, and although there is a correlation between infection and cluster/subcluster type, it is statically weaker than with M. tuberculosis infection. But similarly, there are instances where phages are able to overcome the host barrier at moderate frequencies (10−5), and examination of phage Rosebush mutants capable of infecting M. smegmatis Jucho (99) reveals amino acid substitutions in putative tail fibers, reminiscent of the Cluster G mutants that infect M. tuberculosis.

Mechanisms of Phage Resistance

Resistance to phage infection can occur by a variety of mechanisms including surface changes, and phages can presumably coevolve to overcome this resistance, reflecting the processes giving rise to the expanded-host-range mutants described above. However, in general, little is known about mycobacterial receptors for phage recognition or the determinants of host specificity. For phage I3 (which is not completely sequenced but is a Cluster C–like phage) resistance is accompanied by loss of cell-wall-associated glycopeptidolipids (121), and an M. smegmatis peptidoglycolipid, mycoside C(sm), has been implicated in the binding of phage D4 (which is also genomically uncharacterized) (122). Lyxose-containing molecules have also been proposed as possible receptors for the unsequenced phage Phlei (123, 124). There is clearly much to be learned about mycobacteriophage receptors and how phage tail structures specifically recognize them.

However, there are many other determinants of host range beyond the availability of cell wall receptors, including restriction/modification systems, lysogenic immunity, CRISPR elements (125), and various abortive infection systems including those mediated by toxin-antitoxin systems (126). M. smegmatis mc2155 has no known prophages, restriction modification systems, or CRISPR arrays, which may contribute to its suitability as a permissive host for phage isolation. However, M. tuberculosis H37Rv contains a type III-A family CRISPR array (127) and more than 80 putative toxin/antitoxin systems (128), perhaps suggesting development within a phage-rich environment in its recent evolutionary history. None of the spacer elements within the M. tuberculosis CRISPR array (which are used for spoligotyping M. tuberculosis isolates) closely match known phage sequences, and it is unclear whether the CRISPR arrays are currently active or contribute in any way to phage resistance (129). M. tuberculosis H37Rv has two small (~10 kbp) prophage-like elements in its genome (φRv1 and φRv2), but it is unlikely that these confer immunity to other phages (96). However, a likely intact 55-kbp prophage has been identified in a Mycobacterium canettii strain (88), and other prophages are present in the genomes of M. avium 104 (130), Mycobacterium marinum (87), M. ulcerans (85), and Mycobacterium abscessus (83, 84). Resistance of M. smegmatis to D29 infection can result from overexpression of the host multicopy phage resistance (mpr) gene, perhaps by alteration of the cell surface, although the specific mechanism is not known (131, 132).

Because phages can easily replicate from a single particle to vast numbers (there are 106 to 108 particles in a typical plaque), and mutants arise at moderate frequencies, host range mutants can readily arise within environmental populations. As such, phages are expected to move from one host to another at frequencies that are vastly greater than the time required to ameliorate their genomic features, such as coding biases and GC%, to a specific host. This leads to a model (Fig. 6) in which two key parameters contribute to the diversity of phages: the ability of phages to rapidly switch hosts, and the availability of a broad spectrum of closely related hosts in the environment from which the phages are isolated (99). This model can therefore account for the nature of mycobacteriophage genomes and predicts that similar phage diversity will be seen using other hosts and similar sampling (99).

Lysis Systems

Host cell lysis is a critical step in phage lytic growth, and in the prototype lambda system is both efficient and precisely timed (133, 134). Understanding the lysis systems of mycobacteriophages is of particular interest in that these can illuminate features of mycobacterial cell walls. Mycobacteriophage lysis systems are described in detail in reference 243 and will be discussed only briefly here.

Most mycobacteriophages encode at least three proteins required for lysis: a peptidoglycan-cleaving endolysin (also called Lysin A), Lysin B, and a holin; a few lack Lysin B, some either lack a holin or it is difficult to identify bioinformatically, but all encode an endolysin (135–138). Phage Ms6 and its relatives encode an additional protein that acts as a chaperone for delivery of the endolysin to its peptidoglycan target (139). The endolysins are diverse and modular in nature, reflecting an intragenic mosaicism that is a microcosm of the generally mosaic nature of the phage genomes (138). Many are composed of three segments: an N-terminal domain with predicted peptidase activity, a central domain that cleaves the peptidoglycan sugar backbone, and a C-terminal cell wall binding domain; there are, however, numerous departures from this general organization (138). In total, there are at least 25 different organizations (Org-A to Org-Y) with unique combinations of the constituent domains. Interestingly, the Ms6 lysA (Org-J) gene encodes a second lysis gene that is wholly embedded within lysA and is expressed by translation initiation from an internal start codon; phage mutants that express only the longer (Lysin384) or the shorter (Lysin241) endolysin are viable (140). Lysin B encodes an esterase that cleaves the linkage of the mycolylarabinogalactan to the peptidoglycan (136, 137) and, unlike lysin A, is dispensable for lytic growth (137). However, it is required for optimal lysis and efficient phage reproduction (137) and likely plays an analogous role to the spanins that facilitate fusion of the inner and outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria during phage lysis (134, 141). Analysis of the Ms6 gp4 shows that it is a likely holin, with a signal-arrest-release (SAR) domain followed by a transmembrane domain (142). However, Ms6 gp5 also has a transmembrane domain, and gp4 and gp5 interact to facilitate lysis (142).

INTEGRATION SYSTEMS

Phages within more than one-half of the different clusters encode a phage integrase, and there are numerous examples of both tyrosine integrases (Int-Y) and serine integrases (Int-S); these include Clusters A, E, F, G, I, J, K, L, M, and P and the singletons Dori and DS6A. But the distribution of Int-Y and Int-S types within different clusters is nonrandom. For example, all of the phages within Clusters E, F, G, I, J, K, L, and P (as well as Dori and DS6A) encode tyrosine integrases, and all of the Cluster M phages encode serine integrases. However, the distribution of different integrase types varies among the various subclusters within Cluster A. For example, all of the A1, A5, A7, and A10 phages encode an Int-S, as well as 2 of the 8 A3 phages, 11 of the 14 A4 phages, and 1 of the 2 A8 phages (the other has a deletion in this region of the genome); 7 of the 9 A2 phages, 6 A3 phages, and 3 A4 phages encode Int-Ys. These systems thus may evolve quickly relative to the rest of the genomes, presumably by promoting site-specific or quasisite-specific recombination events.

Interestingly, two of the A2 phages, the one A9 phage, and all six A6 phages have a parA/B partitioning system at the location where the integrase is in the related phages (67). Presumably, these genomes replicate extrachromosomally during lysogeny, and the parA/B systems ensure their accurate segregation at cell division and conferring prophage maintenance—essentially the same functionality provided by the integration systems (143). How these phages are able to replicate their genomes during lysogeny is unclear, especially as their related genomes that integrate presumably do not.

For most of the genomes encoding a tyrosine integrase, the location of attP can be bioinformatically predicted. Typically, these use a bacterial attachment site (attB) overlapping the 3′ end of a tRNA gene, and to preserve the integrity of the tRNA following integration, attP and attB typically share 30- to 40-bp sequence identity. Thus, a BLASTN search of the phage genome against the M. smegmatis chromosome usually identifies the putative attB site. At least 12 attB sites have been identified this way, and usage of the sites has been shown for at least 8 of these (67, 90, 97, 103, 144–146). For the Cluster E and Cluster L phages, bioinformatic analysis fails to identify putative attB sites, and these await experimental determination.

Phages encoding serine integrases do not integrate at host tRNA genes and often use attB sites located within open reading frames (147, 148). The attP and attB sites typically share only minimal segments of sequence identity (3 to 10 bp) and thus cannot be readily predicted bioinformatically and require experimental analysis. The attB sites for two different mycobacterial Int-S systems have been described: Bxb1, which integrates into the groEL1 gene of M. smegmatis, and Bxz2, which integrates into the gene Msmeg_5156 (145, 147). Bxb1 integration has been especially useful for gaining insights into mycobacterial physiology because Bxb1 lysogens are defective in the formation of mature biofilms (149). This results specifically from inactivation of the groEL1 gene by integrative disruption and led to the demonstration that GroEL1 plays a role as a dedicated chaperone for mycolic acid biosynthesis (149, 150). It is not known if disruption of Msmeg_5156 or any other host gene as a consequence of phage integration via a serine integrase has specific physiological consequences.

Phage integration systems typically are carefully regulated in their recombination directionality, such that integrase catalyzes integrative recombination using attP and attB sites (252 bp and 29 bp, respectively [151, 152]) but in the absence of accessory factors does not mediate excisive recombination utilizing attL and attR sites (which are themselves the products of integration) (153). Directional control is enabled by a recombinational directionality factor (RDF), a phage-encoded accessory actor that determines which pairs of attachment sites can undergo recombination. The L5 RDF has been identified (gp36) and acts by binding to specific DNA sites within attP and attR to bend DNA and alter the nature of higher-order protein-DNA architectures that can be formed by the Int-Y, the RDF, and the host integration factor, mIHF (154–157). Directional control is determined by a different mechanism for the serine integrases, as illustrated for Bxb1. The attachment sites are relatively small (<50 bp), and Int binds as a dimer to each site, and the choice of pairs of sites competent for recombination is determined by which protein-DNA complexes can undergo synapsis, presumably predicated on compatible conformations of Int bound to specific sites (158, 159). A phage-encoded RDF, Bxb1 gp47, associates with Int-DNA complexes not through DNA binding, but by direct protein-protein interactions and presumably alters the conformations such that attL and attR can undergo synapsis, but attP and attB cannot (160, 161). A curious feature of Bxb1 is that the RDF is encoded by gene 47, which is situated among DNA replication genes, and is not closely linked to int (gene 35). Numerous mycobacteriophages have homologues of Bxb1 47, including many (such as L5) that utilize tyrosine integrases and for which there is no obvious role in recombination. Presumably, these genes play alternative roles in phage growth, most likely in DNA replication, and have been coopted by the integration systems for directional regulation (162).

MYCOBACTERIOPHAGE GENE EXPRESSION AND ITS REGULATION

None of the sequenced mycobacteriophage genomes encode single-subunit RNA polymerases, and it is likely that all phage transcription utilizes the host RNA polymerase. In some examples, phage growth has specifically been shown to be sensitive to the transcription inhibitor, rifampin (33, 50). Promoters corresponding to those used by the host major sigma factor (SigA) have also been identified in several mycobacteriophages and can be predicted in many others. For example, the strong Pleft promoter in phage L5 closely corresponds to −10 and −35 SigA sequences (163), as do both the early lytic promoter (PR) and the repressor promoter (Prep) of BPs (164), and in all three examples, the transcription start site has been mapped. Interestingly, in both the BPs promoters, these transcripts provide a leaderless mRNA for the first gene in the operon, with the first base of the translation initiation codon corresponding to the 5′ end of the mRNA. The use of leaderless mRNA transcripts has been shown previously in expression of the firefly luciferase reporter gene in an L5 recombinant phage (165). A SigA-like promoter has also been described for expression of the Ms6 lysis cassette, but this does include a leader between the transcription initiation site and the predicted translational start codon (166).

The use of host SigA-like promoters does not, however, appear to be universal for mycobacteriophage transcription. For example, a search for SigA-like promoters in mycobacteriophage Rey reveals no close matches and none that closely correlate with positions where promoters are anticipated to be. In phage Giles, where the transcripts in lysogeny as well as early and late lytic growth have been mapped by RNAseq (Fig. 4), there are no evident SigA-like promoter sequences upstream of where transcription starts. Although late transcripts are likely to utilize phage-encoded activators, it is unclear whether the early promoters in Giles use an alternative host sigma factor or if these also are regulated by phage-encoded functions. There is clearly much to be learned about how transcription initiation is regulated in mycobacteriophage growth. The Cluster A phages all encode a potential sigma factor (Phams 1448, 1922, 2982 in the Phamerator database Mycobacteriophage_285), as indicated by HHPred searches with the closest similarity to SigK of M. tuberculosis, which could regulate phage gene expression. Many phages also encode one or more WhiB proteins, but whether these regulate host or phage expression is not clear. In TM4, it has been shown that the phage-encoded WhiB protein is not required for phage growth, although it contains an Fe-S cluster, is a dominant negative regulator of the host whiB2 gene, and promotes superinfection exclusion (167).

Transcriptomics

RNAseq analysis of transcription in phage Giles is quite informative. In lysogeny, few regions are expressed—as expected—and these include gene 47, which encodes the phage repressor. Somewhat surprisingly, the repressor is expressed at high levels, equivalent to the 0.5 percentile of highest expressed genes in M. smegmatis (107), in noted contrast to the lower expression of other phage repressors (168). Presumably, the Giles repressor binds with relatively low affinity to its binding site(s), although these have yet to be identified. Lysogenic transcription proceeds through the four downstream genes, although at a much lower level (Fig. 4). The leftward-transcribed genes at the left end of the genome (3–4) are also expressed at a low level in lysogeny. Perhaps most surprising from this RNAseq analysis is the expression of an apparent noncoding RNA near the right end of the genome (Fig. 4), which is made during both lysogenic and early lytic growth. It is expressed at a high level, but its function is unclear, and the DNA segment encoding it is not required for phage growth or lysogeny.

Immunity Regulation in Cluster A Phages

An unusual system for gene expression is found in the temperate Cluster A phages but has been studied in detail in just a few examples: L1, L5, and Bxb1 (163, 169–177). The repressor is encoded in the right part of the genome (gene 71 in phage L5) and codes for a small protein (183 amino acids) containing a putative helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif near its N-terminus; deletion of the gene interferes with lysogeny and generates a clear plaque phenotype. L5 gene 71 is sufficient to confer immunity to superinfection, and thermo-inducible mutations map in the repressor gene (110, 176, 178). The repressor sequence of the closely related L1 phage is identical to that of L5 (176). The repressor functions by binding to a 13-bp operator site that overlaps the early lytic promoter, Pleft, situated near the right end of the genome and transcribing leftward (163, 169). It is a two-domain protein with an N-terminal domain (residues 1 to 64) and a C-terminal domain (residues 64 to 183) separated by a hinge region (172), and mutations in either domain influence DNA binding (172, 176). The repressor binds as a monomer and imparts a modest DNA bend (30°) at its binding site (171).

Surprisingly, there are many additional repressor-binding sites situated throughout the L5 genome, and the repressor has been shown to bind to 23 of these in addition to its operator at Pleft (169). These sites correspond to a tightly conserved asymmetric consensus sequence, 5′-GGTGGc/aTGTCAAG, and all or most of the base positions are critical for repressor binding (169, 171). A clue to the role of these additional binding sites emerges from their genomic locations and orientation. With few exceptions, they are located within short intergenic regions or overlapping translation initiation or termination codons and are oriented in one direction relative to the direction of transcription (169). Thus, in the left arm of L5, in which the virion structure and assembly genes are transcribed rightward, there are four sites in the “−” orientation (and one at the extreme left end in the nontranscribed region in the “+” orientation, where “+” and “−” refer to whether the sequence corresponds to the top or bottom strand of the genome), and in the leftward transcribed right arm there are 17 sites in the “+” orientation (and one at the extreme right end in the nontranscribed region in the “−” orientation). There are no apparent promoters at each of these sites, suggesting a role different from that of the true operator site at Pleft (169). Insertion of one or more sites between a nonphage promoter (hsp60) and a reporter gene results in a reduction of reporter activity, in a manner that is dependent on both the repressor and the orientation of the site, which is magnified with larger numbers of binding sites (169). This suggests a model in which repressor binding to these sites acts to promote cessation of transcription and facilitate silencing of the L5 genome in the lysogenic state. These sites are thus referred to as “stoperators” (169). An example of stoperator location and orientation in mycobacteriophage Alma is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Mycobacteriophage Bxb1 is heteroimmune to L5 but contains a similar regulatory system (51, 175). The Bxb1 repressor (gp69) shares only 41% amino acid sequence identity to L5 gp71, and there are a total of 34 putative operator/stoperator sites in the Bxb1 genome. As in L5, these sites correspond to a tightly conserved asymmetric consensus sequence, 5′-GTTACGt/ag/aTCAAG, and are located in short intergenic regions in one orientation relative to transcription. The consensus sequences of the L5 and Bxb1 stoperators are closely related but with differences that likely contribute to heteroimmunity of the two phages (175). Genomic analysis of the large number of Cluster A phages shows that they all share this unusual repressor/stoperator system, with variations of the stoperator consensus sequence that correlate with subcluster designation (98). However, the variation typically occurs within positions 2 to 8 of the consensus sequence, and positions 1 (G) and 9 to 13 (5′-TCAAG) are invariant. How heteroimmunity evolves in this system is unclear, because although amino substitutions within the repressor could readily lead to altered recognition of positions 2 to 8 in the stoperator sites, it is unclear what selection pressure leads to coordinate evolution of over 30 genomically dispersed binding sites to new specificities (see Fig. 6). Interestingly, although the repressor/stoperator system is restricted to the Cluster A phages within the collection of sequenced mycobacteriophages, it appears to be shared with phages of some other Actinomycetales hosts. For example, there are multiple stoperator-like sites in Streptomyces phage R4 and its relatives (244), as well as in Rhodococcus phage RER2 (179); in the latter phage the invariant positions (1, 9 to 13) are the same as in the Cluster A mycobacteriophages, but the R4-like Streptomyces phage stoperators are substantially different. The prevalence of this regulatory system among the broader Actinomycetales phage population remains to be explored.

Although this particular regulatory system is confined to Cluster A phages, within the mycobacteriophages, other phages contain repeated sequences that are likely involved in the regulation of gene expression. One example is the Cluster K phages that contain a conserved sequence (5′-GGGATAGGAGCCC) positioned 2 to 8 bp upstream of putative translation start sites and are thus referred to as start-associated sequences (SASs); there are 10 to 19 copies per genome (97). The sequence is asymmetric and is situated in the expected location of the ribosome binding site, and eight of the conserved positions can pair with the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA. However, there are well-conserved positions at the edges of the site that cannot pair with the 16SrRNA, suggesting that it is not just a common variation of a ribosome binding site. Moreover, the sites are situated exclusively next to nonvirion structural genes, and the consensus site is present neither in other mycobacteriophages nor in the M. smegmatis genome (97). So if these SASs are involved in translation initiation, they likely also require a phageencoded regulator. An intriguing hypothesis is that the SAS-associated genes are highly expressed in early lytic growth and that the SASs play a role in releasing ribosomes from these transcripts during late lytic growth to optimize ribosome availability for late gene expression. Curiously, a subset of the SAS sites has a second conserved sequence composed of imperfect 17-bp IRs separated by a variable spacer. Because of their tight association with SASs—typically located with a few base pairs upstream—these are referred to as extended start-associated sequences, and their roles are unknown (97).