Abstract

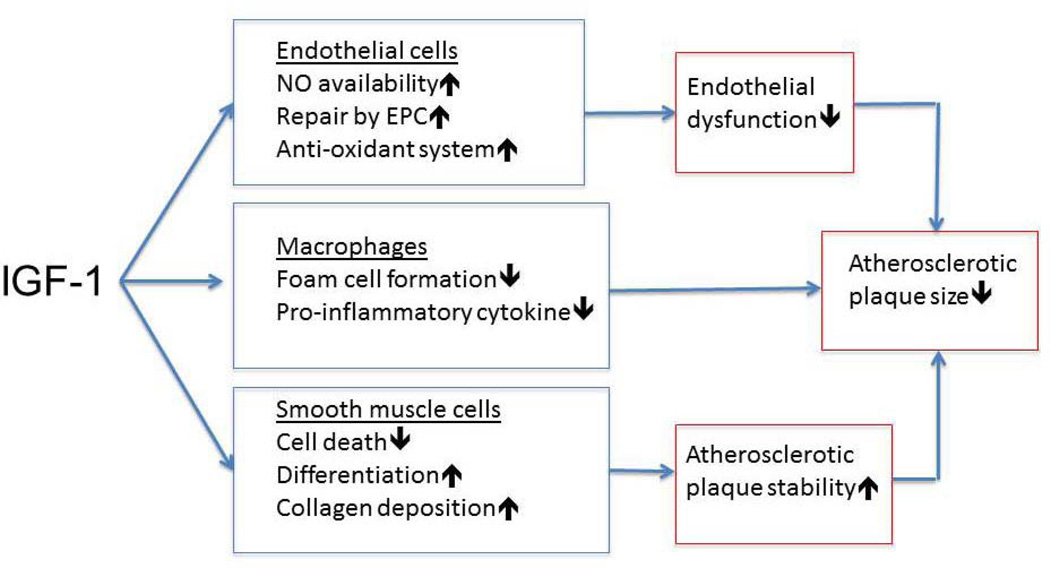

The process of vascular aging encompasses alterations in the function of endothelial (EC) and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) via oxidation, inflammation, cell senescence and epigenetic modifications, increasing the probability of atherosclerosis. Aged vessels exhibit decreased endothelial antithrombogenic properties, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and inflammatory signaling, increased migration of VSMCs to the subintimal space, impaired angiogenesis and increased elastin degradation. The key initiating step in atherogenesis is subendothelial accumulation of apolipoprotein-B containing low density lipoproteins resulting in activation of endothelial cells and recruitment of monocytes. Activated endothelial cells secrete “chemokines” that interact with cognate chemokine receptors on monocytes and promote directional migration. Recruitment of immune cells establishes a pro-inflammatory status, further causing elevated oxidative stress, which in turn triggers a series of events including apoptotic or necrotic death of vascular and non-vascular cells. Increased oxidative stress is also considered to be a key factor in mechanisms of aging-associated changes in tissue integrity and function. Experimental evidence indicates that insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) exerts anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and pro-survival effects on the vasculature, reducing atherosclerotic plaque burden and promoting features of atherosclerotic plaque stability.

Growth factors and Atherosclerosis

Initial results from experiments employing the endothelial denudation induced intima hyperplasia model showed a detrimental effect of growth factors (i.e., platelet derived growth factor-B [PDGF-B], transforming growth factor-β [TGFβ], epidermal growth factor [EGF] and insulin-like growth factor [IGF-1]), via stimulation of migration and proliferation of VSMCs and promotion of neointima formation [1–4]. However, in animal models of atheroma formation, such as the apolipoprotein e−/− (Apoe−/−) deficient mouse model,[5] there is limited contribution of growth factors to atherogenesis and in some cases even antiatherogenic activity and reduced oxidative stress in response to some growth factors.[6] For instance, Kozaki et al.[7] showed that the absence of PDGF-B in circulating cells in a Pdgfb−/− mouse model (on Apoe−/− background), led to a phenotypic change in atherosclerotic lesions, namely, more macrophage infiltration and reduced fibrous cap formation as compared with Pdgfb+/+ counterparts. However, after 45 weeks, smooth muscle cell accumulation in the fibrous cap was indistinguishable in the two study groups.[7] Treatment of Apoe−/− mice with a PDGF receptor antagonist delayed, but did not prevent, smooth muscle accumulation and fibrous cap formation. This data suggests a modest contribution of PDGF to atherogenesis. Cardiac-specific overexpression of TGFβ, a growth factor that promotes VSMC proliferation and matrix protein production[8] was reported to limit atherosclerotic plaque burden.[9] Our group has shown that IGF-1 has antiatherogenic effects via anti-inflammatory and pro-repair mechanisms, both of which were coupled to changes in vascular oxidative stress.[10] We recently reported that IGF-1 enhances antioxidant activity through upregulation of glutathione peroxidase-1 expression and activity in endothelial cells.[11] In this chapter, we will review the epidemiological and experimental evidence for and the postulated molecular basis of IGF-1’s activity in atherosclerosis and in the vascular aging process.

The physiology of the IGF-1 system

The IGF system encompasses three structurally related peptides: IGF-1, IGF-2 and human pro-insulin.[12] IGF-1 is a small (7649Da) peptide that circulates in the blood in relatively high concentrations (150–400 ng/mL) of which < 1% represents a free-active form.[13] The binding of growth hormone (GH) to its hepatic receptor stimulates expression and release of IGF-1 peptide in the circulation and contributes to the majority of the IGF-1 in plasma.[14] Many other organs produce IGF-1, representing the autocrine and paracrine forms of IGF-1.[15] IGF-1 effects are modulated by six IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs). The expression of IGFBPs is tissue- and developmental stage–specific, and the concentrations of IGFBPs in different body compartments are different.[16] The functions of IGFBPs are regulated by phosphorylation, proteolysis, polymerization, and cell or matrix association of the IGFBP.[17] IGFBP-3 forms a ternary complex with IGF-1 and the Acid Labile Subunit and carries around 80% of the circulating total IGF-1, thus limiting IGF-1 transport across the endothelium. The IGF-1/IGFBP-3 ratio is considered a surrogate for the bioactivity of IGF-1.[18] All 6 IGFBPs have been shown to inhibit IGF-1 action, but IGFBP-1, -3, and -5 are also shown to stimulate IGF-1 action.[14] Some of the effects of IGFBPs may be IGF-1 independent.[16–19]

The IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) is a tetramer consisting of 2 extracellular α-chains and 2 transmembrane β-chains.[20] The β-chains include an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain that is thought to be essential for most of the receptor’s biologic effects.[15] IGF-1R signaling involves autophosphorylation and subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc adapter protein and insulin receptor substrate (IRS) -1, -2, -3, and -4.[21] IRS serves as a docking protein and can activate multiple signaling pathways, including phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K), Akt, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)[20–22] The activation of these signaling pathways induces differential biologic actions of IGF-1, including cell growth, migration, and survival [23, 24] In addition, half of an IGF-1R (i.e. a pair of alpha- and beta-subunits) can form a hybrid receptor with a half of the insulin receptor.[25, 26] These hybrid receptors preferentially bind IGF-1. For instance, in VSMCs and ECs, both IGF-1 and insulin receptor subunits are expressed. However, in VSMCs, the expression of the IGF-1R is predominant to the expression of the insulin/IGF-1 hybrid receptors making VSMCs insensitive to insulin.[27] In contrast, vascular ECs appear more sensitive to insulin. In fact, at physiological concentrations, insulin activates insulin receptors but not IGF-1 or hybrid receptors in ECs.[28] To further complicate the picture, a variety of hormones and growth factors regulate IGF-1, IGF-1R and IGFBP expression in most tissues and there may be crosstalk between IGF-1 signaling pathways and those of other growth factors and hormones.[29]

Epidemiological evidence linking IGF-1 with cardiovascular disease

Acromegaly is the prototypical disease characterized by increased circulating IGF-I. These individuals typically present with increased body growth, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, abnormal lipid profiles and insulin resistance. This state is associated with an increased incidence of cancer and cardiovascular mortality.[30] However data on coronary artery disease incidence are conflicting [31–33]. Of note, adult onset growth hormone deficiency with low circulating IGF-1 has been linked to increased atherosclerotic complications in most observational studies.[34]

Observational cohort studies have evaluated the association of IGF-1 levels with cardiovascular disease as an independent risk factor and yielded inconclusive results. A recent meta-analysis suggests a U-shaped relationship between overall mortality and cardiovascular mortality and IGF-1 levels with increased mortality in both the low and high IGF-1 groups.[35] Some cross-sectional and prospective studies found an association between IGF-1 (and in some cases IGFBP-3) and atherosclerosis, i.e. the higher the levels of IGF-1, the higher the likelihood of all-cause mortality and development of congestive heart failure, but not cardiovascular mortality[36, 37] Other studies found that low IGF-1 levels predict ischemic heart disease and mortality.[38, 39] Conversely, several large prospective cohort studies failed to systematically confirm these findings.[40, 41] Methodological constraints can explain these contradictions. Most studies have used total extractable IGF-1 immunoassays as an estimate of the in-vivo bio-activity of IGF-1.[42] However total IGF-1 levels represent only a crude estimate of the biologically active hormone as less than 1% is present in its free form. Only free IGF-I is believed to be the active form as it can readily cross the endothelium and interact with its own receptor. It has potentially greater physiological [43] and clinical relevance than total IGF-I. To date only three studies have addressed the relation of free IGF-1 and cardiovascular disease. High free IGF-I was associated with decreased carotid plaques and coronary artery disease in participants of the Rotterdam Elderly Study[44] and with decreased carotid intima-media ratio[45]. This association could not be reproduced in a study of 95 male individuals with a prior myocardial infarction[46].

Free IGF-I measurements by available methods might not accurately represent the free fraction of IGF-1 (reviewed in [47]). An IGF-1-specific kinase receptor activation assay has been developed as an alternative method to assess IGF-1 bioactivity.[48] Instead of measuring immunoreactive IGF-1, this kinase receptor assay measures IGF-1 bioactivity by the ability of serum to activate IGF-1R autophosphorylation. Thus this assay accounts for IGFBP and IGFBP protease modulation of IGF-1 activity. Using this technique, IGF-1 bioactivity was evaluated in relation to survival in elderly males from the Netherlands. Individuals in the highest quartile of IGF-1 bioactivity survived significantly longer than those in the lowest quartile, both in the total population (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.2–2.8; P=0.01) and in subgroups with a high inflammatory risk profile or history of cardiovascular disease.[49] An IGF-1 gene promoter polymorphism has been shown to influence circulating IGF-1 levels.[50] As such, in the population-based Rotterdam study, individuals without the 192 base-pair wild-type allele had 18% lower circulating IGF-1 levels and were at increased risk for type 2 diabetes, myocardial infarction and left ventricular hypertrophy.[51] In the presence of hypertension, these individuals also had higher carotid intima-media thickness and higher aortic pulse wave velocity.[52] Additional analyses from this study demonstrated that subjects heterozygous for the 192 or 194 base-pair alleles or non-carriers of these two alleles had lower IGF-1 and higher myocardial infarction-related mortality, particularly in cases of co-existing diabetes.[53, 54] However, others have not replicated these studies even finding the opposite association.[55, 56] It is of note that loss-offunction mutations in genes encoding components of the insulin/IGF-1 pathway are associated with extension of life in multiple organisms including mice.[57, 58] Mutations in the IGF-1R gene that result in reduced IGF-1 signaling have been identified in centenarians.[59] Additional studies designed to assess whether genetically determined low IGF-1 levels or low bioactivity of IGF-1 are important risk factors for atherosclerotic burden and a negative determinant of overall and cardiovascular survival are needed.

Aging and IGF-1

The calorie restriction model has shown that reduction in food intake without malnutrition extends life span and delays age-related disease onset substantially in unicellular and multicellular organisms.[60] Since a reduction in food intake decreases signaling activity and/or bioavailability of insulin and IGF-1 (or corresponding orthologs), it has been proposed that decreased levels of insulin and IGF-1 signaling contribute to longevity. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that mutations in the IGF-1R gene which result in reduced IGF-1 signaling have been found in centenarians.[59] Additionally, experiments performed in genetically altered models in yeast, nematode, drosophila, and mouse, have shown that targeting of corresponding orthologs of insulin/IGF-1 effectively elongates life span. However, targeting of the IGF-1 system has not yielded similar results in all instances. For instance, it was originally reported that mice with inactivated IGF-1R live on average 26% longer than their wild-type littermates and these IGF-1R-deficient mice display greater resistance to oxidative stress, a known determinant of ageing.[61] However, another group found that longevity of lgf1r(+/−) mice was increased only slightly, and only in females (less than 5%).[62] Thus, the causal role of decreased IGF-1 signaling in calorie restriction-induced extension of murine lifespan is uncertain. A recent case-control study in individuals with GH receptor deficiency (thus a severe IGF-1 deficiency) did not confirm the life extending effect of low IGF-1 availability, although these individuals had a lower incidence of cancer and diabetes.[63]

Antiatherogenic effects of IGF-1 in animal models of atherosclerosis

Because IGF-1 is a potent VSMC mitogen, the majority of studies exploring mechanical injury models and direct or indirect mechanisms to alter vascular IGF-1 signaling reported that increased IGF-1 levels or IGF-1 signaling correlates with increased neointimal burden, suggesting that IGF-1 promotes vascular hyperplasia.[64–69] In particular, targeted overexpression of IGF-1 in VSMCs increases neointimal area size.[65] Leukocyte antigen related protein-tyrosine phosphatase (LAR) physically associates with IGF-1R and diminishes its signaling activity by dephosphorylating IGF-1R. Deletion of the LAR gene increased neointima size in a mechanical injury model, consistent with a positive effect of IGF-1 on VSMC migration and proliferation.[70] Animal models of atherosclerosis include genetic hyperlipidemia models such as Apoe−/− and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (Ldlr)-deficient mice, and a Western (high-fat) diet is often supplied to these animals to produce even more pronounced hyperlipidemia, thus accelerating atherogenesis. These hyperlipidemic animals develop atherosclerotic lesions that parallel those of human subjects, characterized by lesion development at vascular branch points and progression from a foam cell stage to a fibroproliferative stage with well-defined fibrous caps and necrotic lipid cores.[71] To date, few studies have evaluated IGF-1 effects on atherosclerosis using Apoe−/− mice. Harrington et al. created double-knockout mice deficient in Apoe and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A), a metalloproteinase that degrades IGFBP-4.[66] Pappa−/−/Apoe−/− mice fed with a Western diet had decreased lesion size, and this correlated with reduced expression of IGFBP-5, which is positively regulated by IGF-1.[72–74] Because PAPP-A deficiency increases IGFBP-4 levels, thereby reducing IGF-1 bioavailability, these data suggested potential pro-atherogenic effects of PAPP-A mediated by IGF-1.

Our group investigated the potential effect of IGF-1 on atherosclerosis by infusing human recombinant IGF-1 into Apoe−/− mice fed a Western diet. This study protocol provided resulted in an approximately two-fold increase in total serum IGF-1 levels, which was associated with enhanced IGF-1 signaling activity.[75] IGF-1 infusion for 12 weeks reduced atherosclerotic lesion size and this effect was accompanied by a significant reduction in urinary excretion of 8-isoprostane, a systemic index of oxidative stress. Other potential beneficial effects included a decrease in lesion macrophage infiltration, reduced aortic expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased levels of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. IGF-1-infused animals had an increase in expression of vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, decreased vascular superoxide levels, and overall reduced oxidative stress localized specifically in atherosclerotic plaque.[75] Interestingly, the IGF-1-induced antioxidant effect was significantly reduced by administration of L-NAME, a pan-nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, indicating that this effect was in part dependent on NO bioavailability. However, infusion of Apoe−/− mice with GH-releasing-peptide-2 (GHRP-2), a synthetic peptide that increases both circulating GH and IGF-I levels, did not reduce atherosclerotic burden, suggesting that an elevation of GH counteracted potential beneficial effects of IGF-1 on the vasculature.[76, 77] Our findings suggested that the antiatherogenic effects of IGF-1 are associated with reduced oxidative stress in the vasculature, although it is important to note that L-NAME did not block the anti-atherosclerotic effect of IGF-1, indicating that increased NO was not the main mediator of the anti-atherosclerotic effect.[75] It has been suggested that an imbalance in redox regulation is associated with aging, leading to elevated vascular oxidative stress which predisposes to atherogenesis. [78] Thus the anti-oxidant effect of IGF-1 could represent an anti-aging mechanism that contributes to prevention of atherosclerosis. We recently found that a ~20% reduction in circulating IGF-1 levels was accompanied by a significant increase in aortic lesion size in Apoe−/− mice.[79] It is well known that levels of circulating IGF-1 decline with aging.[80] Therefore our model of reduced bioavailabiity of IGF-1 in Apoe−/− mice mimics the loss of IGF-1 bioavailability that occurs with aging, and supports the notion that low IGF-1 bioavailability exacerbates atherosclerosis.

The vascular effects of alterations in circulating IGF-1 represent endocrine effects. To address the effects of locally produced IGF-1 on atherosclerosis, transgenic mice which overexpress IGF-1 in smooth muscle were created on an Apoe−/− background (Apoe−/−-Tg(SMP8-Igf1)).[81] When compared with Apoe−/− mice, the Apoe−/−-Tg(SMP8-Igf1) mice developed a comparable plaque burden after 12 weeks on a Western diet, suggesting that the ability of increased circulating IGF-1 to reduce plaque burden was mediated in large part via non-VSMC target cells.[10] However, advanced plaques in Apoe−/−-Tg(SMP8-Igf1) mice displayed several features of increased plaque stability, including elevated α-smooth muscle actin positive VSMC content, increased fibrous cap area, increased collagen levels, and reduced necrotic cores.[81] It is unclear if local production of IGF-1 in the vasculature declines with aging, as has been described for circulating IGF-1. It is also unknown if aging impairs IGF-1R activation in VSMCs as it does in skeletal muscle [82] and osteoblasts.[83] If this were the case, loss of responsiveness to IGF-1 in VSMCs could contribute to the increased prevalence of atherothrombotic diseases in aged subjects.

IGF-1 and endothelial function

There is increasing evidence that IGF-1 preserves endothelial function. GH deficiency impairs flow-mediated arterial dilation and thus affects endothelial NO-dependent vasodilation.[84] Because GH is a primary regulator of circulating IGF-1 and GH deficiency leads to low IGF-1, it is reasonable to hypothesize that IGF-1 plays a role in vasodilatory responses by regulating NO production in the endothelium. As such, low plasma IGF-1 levels are associated with impaired endothelium dependent vasodilation.[85] In patients with diabetes, vascular tone regulation is impaired, and IGF-1 supplementation improves vascular responses to vasodilators, potentially by enhancing eNOS activity.[86] These observations in humans are supported by animal and cell culture studies. For example, in mice fed a high-fat diet (an animal model of type-2 diabetes), IGF-1 resistance exists at the endothelial level, which in turn blunts eNOS dependent vasorelaxation.[87] This finding is consistent with a positive effect of IGF-1 on endothelium function. However, this model was characterized by increased serum IGF-1 levels, whereas patients with poorly controlled diabetes generally have low serum IGF-1 levels.[88]

In endothelial cell culture systems, IGF-1 acutely enhances eNOS dependent NO production by increasing phosphorylation at Ser1177 via a PI3K and Akt dependent pathway.[89] In addition to acute effects of IGF-1 on eNOS activity, a link has been suggested between tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) biosynthesis and IGF-1. A mouse model in which one of the key enzymes involved in BH4 biosynthesis (6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase) is deficient produces dwarfism with markedly reduced serum IGF-1 levels, suggesting that a functional BH4 biosynthetic pathway is essential for maintenance of IGF-1 levels and normal growth.[90] In contrast, in pheochromocytoma-12 cells, IGF-1 elevates BH4 levels, potentially by enhancing its biosynthesis through a PI3K-dependent mechanism.[91] It would be interesting to determine if the potential IGF-1 effect on BH4 biosynthesis can be generalized to other tissues with NO synthase activity.

In Apoe−/− mice fed a high-fat diet, we observed that IGF-1 infusion enhanced eNOS gene expression in the aorta.[10] Recently, we demonstrated that IGF-1-induced reduction in atherosclerotic plaque burden does not depend on NO bioavailability.[75] The role of IGF-1 in regulating endothelial function is supported by the recent finding that a deficiency of GH and IGF-1 exacerbates high-fat diet induced endothelial impairment and that systemic IGF-1 deficiency in mice decreases vascular oxidative stress resistance by impairing the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response.[92] Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 2) is a transcription activator that binds to antioxidant response elements in the promoter regions of target genes; hence it is important for the coordinated up-regulation of genes in response to oxidative stress. We recently found that in vascular endothelial cells IGF-1 reduces oxidative stress by increasing expression and activity of glutathione peroxidase-1, [11] a major antioxidant enzyme whose activity is strongly inversely related to the prevalence of cardiovascular events [93]. Abbas et al. took a different approach to investigate IGF-1 effects on endothelial function by creating mice with whole-body haploinsufficiency of IGF-1R and endothelium specific holo- and haploinsufficiency of IGF-1R.[94] They found that haploinsufficiency of IGF-1R both at the whole-body level and in endothelium led to enhanced endothelial function, as assessed by reduced vasoconstriction to phenylephrine, increased basal NO production, and increased endothelial cell insulin sensitivity leading to augmented insulin-mediated NO generation. They conclude that IGF-1R, via its ability to form hybrids with the insulin receptor, is a negative regulator of insulin signaling in endothelium. In fact, in an insulin-resistance mouse model (whole-body insulin receptor haploinsufficiency), the introduction of IGF-1R haploinsufficiency restored insulin-mediated NO production, presumably by changing IGF-1R: insulin receptor stoichiometry. Therefore, whether IGF-1 (or IGF-1R) augments or diminishes endothelial function might be substantially affected by physiological settings (e.g. the presence of insulin resistance). Further studies are required to understand this complex interaction between IGF-1 and the endothelium.

IGF-1 and vascular smooth muscle cells

In VSMCs IGF-1 promotes cell proliferation,[1, 2] survival,[95] and differentiation.[96, 97] It has been shown that moderate oxidative stress can enhance IGF-1 signaling in VSMC, whereas excessive oxidative stress seems inhibitory. For example, oxidative stress augments IGF-1 and IGF-1R expression in VSMC.[98] In fact, IGF-1R tyrosine kinase activity mediates hydrogen peroxide activation of MAPK and Akt.[99, 100] In addition, IGF-1 itself moderately elevates ROS in VSMC suggesting that IGF-1 amplifies its activity through ROS generation.[101] Furthermore, ROS enhance insulin signaling by inhibiting the protein tyrosine phosphatase activity and given the similarities between IGF-1 and insulin signaling pathways, ROS may also enhance IGF-1 signaling.[102] However, elevated ROS also inhibit insulin/IGF-1 signaling and induce apoptotic cell death.[103] Thus, it seems that the balance between ROS elevation and the activity of antioxidant systems (e.g. enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase), and presumably a specific location of ROS generation (e.g., plasma membrane vs. mitochondrion), will determine the dominant downstream vascular effects of oxidant stress.

In advanced atherosclerotic plaques, a balance between cell death and survival of cells within the fibrous cap, primarily composed of VSMC and extracellular matrix, appears to correlate with plaque instability or stability.[104] Moreover, apoptosis of VSMC accelerates atherosclerosis, promotes calcification and medial degeneration, important steps for the transition from early to advanced plaques.[105] VSMC apoptosis is controlled by growth factors and cytokines, including IGF-1. A key pro-atherogenic molecule, oxidized LDL (OxLDL), co-localizes with apoptotic VSMC in human atherosclerotic plaques, and these cells have reduced IGF-1 and IGF1R levels.[6, 106] In human carotid atherosclerotic plaques, a reduced expression of IGF-1, along with downregulation of IGF-2 and IGFBP-3, -4, -5, and -6, and upregulation of IGFBP-1, was also found.[107] Consistent with these findings, OxLDL reduces IGF-1R levels and induces apoptosis of cultured VSMC via a redox-sensitive mechanism that includes activation of two major oxidases, lipoxygenase (LOX) and NADPH oxidase, which have been shown to be major sources of elevated oxidative stress in plaques.[6, 106] IGF-1 is a potent survival factor for VSMC, and increased IGF-1 signaling prevents OxLDL-induced VSMC apoptosis via a PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway.[95] IGF-1 reduced the total number of apoptotic cells, specifically in atherosclerotic plaque in Apoe−/− mice and, interestingly, IGF-1 had no effect on plaque SMC cell apoptosis indicating that the anti-apoptotic effect of IGF-1 was exerted on non-SMC plaque cells.[75] In addition to its antiapoptotic effects, IGF-1 also suppresses autophagic cell death of plaque-derived VSMC via Akt-dependent inhibition of microtubule-associated-1 light chain-3 expression.[108] We described that smooth muscle specific IGF-1 overexpression in Apoe−/− mice changes atherosclerotic lesion phenotype, resulting in elevated α-smooth muscle actin positive VSMC content, increased fibrous cap area and collagen levels, and reduced necrotic cores.[81] Whereas a reduction in apoptotic cell death of VSMC was not confirmed, locally produced IGF-1 promoted VSMC differentiation and matrix deposition, also seen in cultured VSMCs.[81, 96] These autocrine/paracrine effects of IGF-1 could potentially stabilize plaques thereby reducing the prevalence of atherothrombotic vascular disease.

IGF-1 and endothelial regeneration

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) contribute to neovascularization in response to ischemia.[109] EPCs promote endothelial repair directly by differentiation and integration into a newly formed endothelial layer or by producing a variety of pro-angiogenic cytokines and growth factors, promoting proliferation and migration of pre-existing EPCs. Aging has been shown to be associated with a reduced EPC availability and impaired function, including homing, proliferation and migration.[110] Importantly, it has been shown in human subjects that an increase in circulating IGF-1 in response to GH or IGF-1 administration corrects age-dependent impairment of EPCs. Thus, GH or IGF-1 increased circulating EPC number and improved EPC colony forming and migratory capacity, enhanced incorporation into tube-like structures, and augmented endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression.[111] These findings provide direct evidence that IGF-1 exerts beneficial effects on aging associated impairment in endothelial repair mechanisms. Similar findings in an animal model of atherosclerosis imply that IGF-1 influences EPCs mobilization and function by altering NO bioavailability as it does in mature ECs.[10] However, many questions remain to be answered in regard to potential IGF-1 regulation of EPCs niches and subsequent EPCs mobilization and homing.[112]

IGF-1 and inflammation

An increase in inflammation is associated with vascular aging and contributes to the development of several aging-associated syndromes such as sarcopenia (reduction in skeletal muscle mass and development of muscle weakness).[113] Furthermore, sarcopenia progression correlates with suppression of IGF-1 signaling in skeletal muscle.[114] At an early stage of atherogenesis, phagocytic cells such as monocytes/macrophages are recruited and infiltrate into a fatty streak, scavenging accumulated LDLs which have been denatured or modified (e.g. aggregated or oxidized) locally in the tissue. Modified LDL binding to cell surface receptors and subsequent internalization induces a variety of pro-inflammatory responses in these cells, triggering feed-forward reactions to promote atherosclerosis. Inflammatory responses and oxidative stress are closely related; for instance, in monocytes/macrophages it has been shown that reactive oxygen species enhance pro-inflammatory cytokine production via nuclear factor-κB activity.[115] At the tissue level, activated inflammatory cells express high-levels of oxidant-generating enzymes, such as myeloperoxidase, NADPH oxidase and 12/15-LOX, causing oxidative damage to surrounding tissue, further inducing inflammatory responses.

Several reports suggest that IGF-1 is anti-inflammatory. For instance, there is an inverse relation between serum interleukin (IL)-6 and IGF-1 levels, and IGF-1/IGFBP-3 administration to patients with severe burn injury induced an anti-inflammatory effect and reduced IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α.[116–118] Furthermore, low IGF-1 and high IL-6 and TNF-α levels are associated with higher mortality in elderly patients.[119] Accordingly, our group showed that IGF-1 modulates macrophage function. This could represent a key mechanism mediating the anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects of IGF-1 in the vasculature. Indeed, human recombinant IGF-1 infusion into Apoe−/− mice markedly suppressed macrophage infiltration into atherosclerotic lesions by a mechanism associated with downregulation of TNF-α expression.[10] In human subjects with GH deficiency, low serum IGF-1 levels are associated with increased lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and TNF-α expression in macrophages.[120] Interestingly, macrophages from these subjects are more susceptible to foam cell formation in vitro and, in fact, uptake of oxidized LDL was enhanced in these cells, consistent with the ability of LPL to facilitate binding and uptake of modified LDL. Furthermore, IGF-1 reduces aortic LPL mRNA levels in Apoe−/− mice and also in cultured macrophages.[75] Taken together, these observations in animal models and humans support an anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and thus anti-atherogenic effect of IGF-1. However, other reports suggest that IGF-1 has pro-inflammatory effects. For instance, in monocytes/macrophages, IGF-1 enhanced chemotactic macrophage migration, stimulated TNF-α expression, and enhanced LDL uptake and cholesterol esterification.[121, 122] Moreover, pro-atherogenic factors such as advanced glycosylation end products and TNF-α increase IGF-1 synthesis.[123, 124] Some of these effects of IGF-1 on macrophages might not necessarily be proatherogenic; for instance, IGF-1-mediated stimulation of cellular uptake of LDL could contribute to reducing plasma LDL cholesterol levels.[122] Additional studies are required to clarify the action of IGF-1 on inflammatory processes in atherosclerosis.

IGF-1 and Hypertension

Hypertension is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis, and aging influences the prevalence of hypertension, although aging by itself may not be sufficient to induce hypertension.[125] As described above, IGF-1 increases endothelial NO production, hence a major part of IGF-1 effects on vascular tone regulation can be attributed to eNOS-NO dependent mechanisms. In addition, insulin/IGF-1 reduces [Ca2+]i and Ca2+-myosin light chain sensitivity in VSMC thereby inducing vascular relaxation.[126] In humans, there is an inverse association between free IGF-1 and isovolumic relaxations in arterial systemic hypertension and IGF-1 levels in the low-normal range are associated with hypertension in subjects without pituitary and cardiovascular disease.[127] Moreover peripheral resistance and systolic blood pressure were increased in liver-specific IGF-1 knockout mice, and IGF-1–induced vasodilator effects were impaired before the onset of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats.[128–130] Collectively, these observations point to a pathophysiological role of IGF-1 in the development of hypertension.

The powerful vasoconstrictor, endothelin-1, has also been suggested as a potential link between IGF-1 and vascular tone regulation. IGF-1 attenuates endothelin-1-induced contractile responses in porcine aorta, potentially by altering endothelin-1/endothelin receptor type-A signaling activity in smooth muscle cells.[131] IGF-1 might directly or indirectly regulate endothelin-1 gene expression; for example, in liver specific IGF-1-deficient mice, endothelin-1 gene expression was upregulated in the aorta, and was associated with elevated systolic blood pressure and impaired vasorelaxation.[128] IGF-1 enhancement of NO bioavailability could explain the ability of IGF-1 to antagonize endothelin-1 contractile response. As such, endothelin-1 increases vascular superoxide by enhancing NADPH-oxidase activity and thus lowers NO bioavailability, [132–134] [133–135] [134–136] [136–138] [137–139] suggesting that endothelin-1-induced endothelial dysfunction is, at least partly, mediated by increased oxidative stress.[121–123] Interestingly, insulin and IGF-1 upregulate endothelin-A levels in VSMCs, indicating a complex interaction between insulin/IGF-1 and endothelin effects.[135, 136]

Conclusions

Increasing evidence points to pleiotropic effects of IGF-1 on the vasculature resulting in reduced vascular oxidant stress, apoptosis and inflammatory signaling. Importantly, IGF-1 has been shown to reduce atherosclerotic burden and increase plaque stability in animals. These findings suggest that IGF-1 may have anti-atherogenic effects on the normal vascular aging process. Further studies are required to assess the therapeutic potential of IGF-1 in the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms mediating IGF-1 effects on atherosclerosis

References

- 1.Cercek B, Fishbein MC, Forrester JS, Helfant RH, Fagin JA. Induction of Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Messenger Rna in Rat Aorta after Balloon Denudation. Circ Res. 1990;66:1755–1760. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maile LA, Capps BE, Ling Y, Xi G, Clemmons DR. Hyperglycemia Alters the Responsiveness of Smooth Muscle Cells to Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2435–2443. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nabel EG, Yang Z, Liptay S, San H, Gordon D, Haudenschild CC, Nabel GJ. Recombinant Platelet-Derived Growth Factor B Gene Expression in Porcine Arteries Induce Intimal Hyperplasia in Vivo. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1822–1829. doi: 10.1172/JCI116394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soaje M, Deis RP. A Modulatory Role of Endogenous Opioids on Prolactin Secretion at the End of Pregnancy in the Rat. J Endocrinol. 1994;140:97–102. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1400097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang SH, Reddick RL, Piedrahita JA, Maeda N. Spontaneous Hypercholesterolemia and Arterial Lesions in Mice Lacking Apolipoprotein E. Science. 1992;258:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1411543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okura Y, Brink M, Itabe H, Scheidegger KJ, Kalangos A, Delafontaine P. Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Is Associated with Apoptosis of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Human Atherosclerotic Plaques. Circulation. 2000;102:2680–2686. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozaki K, Kaminski WE, Tang J, Hollenbach S, Lindahl P, Sullivan C, Yu JC, Abe K, Martin PJ, Ross R, Betsholtz C, Giese NA, Raines EW. Blockade of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor or Its Receptors Transiently Delays but Does Not Prevent Fibrous Cap Formation in Apoe Null Mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1395–1407. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64415-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raines EW. Pdgf and Cardiovascular Disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frutkin AD, Otsuka G, Stempien-Otero A, Sesti C, Du L, Jaffe M, Dichek HL, Pennington CJ, Edwards DR, Nieves-Cintron M, Minter D, Preusch M, Hu JH, Marie JC, Dichek DA. Tgf-[Beta]1 Limits Plaque Growth, Stabilizes Plaque Structure, and Prevents Aortic Dilation in Apolipoprotein E-Null Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1251–1257. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.186593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sukhanov S, Higashi Y, Shai SY, Vaughn C, Mohler J, Li Y, Song YH, Titterington J, Delafontaine P. Igf-1 Reduces Inflammatory Responses, Suppresses Oxidative Stress, and Decreases Atherosclerosis Progression in Apoe-Deficient Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2684–2690. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higashi Y, Pandey A, Goodwin B, Delafontaine P. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Regulates Glutathione Peroxidase Expression and Activity in Vascular Endothelial Cells: Implications for Atheroprotective Actions of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clemmons DR. Metabolic Actions of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I in Normal Physiology and Diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41:425–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.017. vii–viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemmons DR. Modifying Igf1 Activity: An Approach to Treat Endocrine Disorders, Atherosclerosis and Cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:821–833. doi: 10.1038/nrd2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-Like Growth Factors and Their Binding Proteins: Biological Actions. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:3–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delafontaine P. Insulin-Like Growth Factor I and Its Binding Proteins in the Cardiovascular System. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;30:825–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider MR, Lahm H, Wu M, Hoeflich A, Wolf E. Transgenic Mouse Models for Studying the Functions of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Proteins. Faseb J. 2000;14:629–640. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai K, Busby WH, Jr, Clarke JB, Clemmons DR. Tissue Transglutaminase Facilitates the Polymerization of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Protein-1 (Igfbp-1) and Leads to Loss of Igfbp-1's Ability to Inhibit Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I-Stimulated Protein Synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8740–8745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohta M, Hirao N, Mori Y, Takigami C, Eguchi M, Tanaka H, Ikeda M, Yamato H. Effects of Bench Step Exercise on Arterial Stiffness in Post-Menopausal Women: Contribution of Igf-1 Bioactivity and Nitric Oxide Production. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2012;22:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones JI, Gockerman A, Busby WH, Jr, Wright G, Clemmons DR. Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 Stimulates Cell Migration and Binds to the Alpha 5 Beta 1 Integrin by Means of Its Arg-Gly-Asp Sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10553–10557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Roith D. The Insulin-Like Growth Factor System. Exp Diabesity Res. 2003;4:205–212. doi: 10.1155/EDR.2003.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuruzoe K, Emkey R, Kriauciunas KM, Ueki K, Kahn CR. Insulin Receptor Substrate 3 (Irs-3) and Irs-4 Impair Irs-1- and Irs-2-Mediated Signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:26–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.26-38.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin Signalling and the Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Nature. 2001;414:799–806. doi: 10.1038/414799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart CE, Rotwein P. Growth, Differentiation, and Survival: Multiple Physiological Functions for Insulin-Like Growth Factors. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:1005–1026. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higashi Y, Sukhanov S, Anwar A, Shai SY, Delafontaine P. Aging, Atherosclerosis, and Igf-1. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:626–639. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moxham CP, Duronio V, Jacobs S. Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Receptor Beta-Subunit Heterogeneity. Evidence for Hybrid Tetramers Composed of Insulin-Like Growth Factor I and Insulin Receptor Heterodimers. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13238–13244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soos MA, Siddle K. Immunological Relationships between Receptors for Insulin and Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Evidence for Structural Heterogeneity of Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Receptors Involving Hybrids with Insulin Receptors. Biochem J. 1989;263:553–563. doi: 10.1042/bj2630553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engberding N, San Martin A, Martin-Garrido A, Koga M, Pounkova L, Lyons E, Lassegue B, Griendling KK. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Receptor Expression Masks the Antiinflammatory and Glucose Uptake Capacity of Insulin in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:408–415. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li G, Barrett EJ, Wang H, Chai W, Liu Z. Insulin at Physiological Concentrations Selectively Activates Insulin but Not Insulin-Like Growth Factor I (Igf-I) or Insulin/Igf-I Hybrid Receptors in Endothelial Cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4690–4696. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnaldez FI, Helman LJ. Targeting the Insulin Growth Factor Receptor 1. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26:527–542. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2012.01.004. vii–viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colao A. The Gh-Igf-I Axis and the Cardiovascular System: Clinical Implications. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:347–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg C, Petersenn S, Lahner H, Herrmann BL, Buchfelder M, Droste M, Stalla GK, Strasburger CJ, Roggenbuck U, Lehmann N, Moebus S, Jockel KH, Mohlenkamp S, Erbel R, Saller B, Mann K. Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Patients with Uncontrolled and Long-Term Acromegaly: Comparison with Matched Data from the General Population and the Effect of Disease Control. J. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3648–3656. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cannavo S, Almoto B, Cavalli G, Squadrito S, Romanello G, Vigo MT, Fiumara F, Benvenga S, Trimarchi F. Acromegaly and Coronary Disease: An Integrated Evaluation of Conventional Coronary Risk Factors and Coronary Calcifications Detected by Computed Tomography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3766–3772. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bogazzi F, Battolla L, Spinelli C, Rossi G, Gavioli S, Di Bello V, Cosci C, Sardella C, Volterrani D, Talini E, Pepe P, Falaschi F, Mariani G, Martino E. Risk Factors for Development of Coronary Heart Disease in Patients with Acromegaly: A Five-Year Prospective Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4271–4277. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmeiro CR, Anand R, Dardi IK, Balasubramaniyam N, Schwarcz MD, Weiss IA. Growth Hormone and the Cardiovascular System. Cardiol Rev. 2012;20:197–207. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318248a3e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgers AM, Biermasz NR, Schoones JW, Pereira AM, Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Egger M, Dekkers OM. Meta-Analysis and Dose-Response Metaregression: Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor I (Igf-I) and Mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2912–2920. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andreassen M, Raymond I, Kistorp C, Hildebrandt P, Faber J, Kristensen LO. Igf1 as Predictor of All Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease in an Elderly Population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:25–31. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruotolo G, Bavenholm P, Brismar K, Efendic S, Ericsson CG, de Faire U, Nilsson J, Hamsten A. Serum Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Level Is Independently Associated with Coronary Artery Disease Progression in Young Male Survivors of Myocardial Infarction: Beneficial Effects of Bezafibrate Treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conti E, Andreotti F, Sestito A, Riccardi P, Menini E, Crea F, Maseri A, Lanza GA. Reduced Levels of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 in Patients with Angina Pectoris, Positive Exercise Stress Test, and Angiographically Normal Epicardial Coronary Arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:973–975. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruidavets JB, Luc G, Machez E, Genoux AL, Kee F, Arveiler D, Morange P, Woodside JV, Amouyel P, Evans A, Ducimetiere P, Bingham A, Ferrieres J, Perret B. Effects of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 in Preventing Acute Coronary Syndromes: The Prime Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrela M, Qiao Q, Koistinen R, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A, Seppala M, Leinonen P. High Serum Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein-1 Is Associated with Increased Cardiovascular Mortality in Elderly Men. Horm Metab Res. 2002;34:144–149. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallander M, Norhammar A, Malmberg K, Ohrvik J, Ryden L, Brismar K. Igf Binding Protein 1 Predicts Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2343–2348. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janssen JA, Stolk RP, Pols HA, Grobbee DE, Lamberts SW. Serum Total Igf-I, Free Igf-I, and Igfb-1 Levels in an Elderly Population: Relation to Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:277–282. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frystyk J. Utility of Free Igf-I Measurements. Pituitary. 2007;10:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s11102-007-0025-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janssen JA, Stolk RP, Pols HA, Grobbee DE, Lamberts SW. Serum Total Igf-I, Free Igf-I, and Igfb-1 Levels in an Elderly Population: Relation to Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:277–282. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boquist S, Ruotolo G, Skoglund-Andersson C, Tang R, Bjorkegren J, Bond MG, de Faire U, Brismar K, Hamsten A. Correlation of Serum Igf-I and Igfbp-1 and -3 to Cardiovascular Risk Indicators and Early Carotid Atherosclerosis in Healthy Middle-Aged Men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischer F, Schulte H, Mohan S, Tataru MC, Kohler E, Assmann G, von Eckardstein A. Associations of Insulin-Like Growth Factors, Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Proteins and Acid-Labile Subunit with Coronary Heart Disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;61:595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frystyk J. Free Insulin-Like Growth Factors -- Measurements and Relationships to Growth Hormone Secretion and Glucose Homeostasis. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2004;14:337–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brugts MP, Ranke MB, Hofland LJ, van der Wansem K, Weber K, Frystyk J, Lamberts SW, Janssen JA. Normal Values of Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Bioactivity in the Healthy Population: Comparison with Five Widely Used Igf-I Immunoassays. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2539–2545. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brugts MP, van den Beld AW, Hofland LJ, van der Wansem K, van Koetsveld PM, Frystyk J, Lamberts SW, Janssen JA. Low Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Bioactivity in Elderly Men Is Associated with Increased Mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2515–2522. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaessen N, Heutink P, Janssen JA, Witteman JC, Testers L, Hofman A, Lamberts SW, Oostra BA, Pols HA, van Duijn CM. A Polymorphism in the Gene for Igf-I: Functional Properties and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes and Myocardial Infarction. Diabetes. 2001;50:637–642. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bleumink GS, Schut AF, Sturkenboom MC, Janssen JA, Witteman JC, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Stricker BH. A Promoter Polymorphism of the Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Gene Is Associated with Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Heart. 2005;91:239–240. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.019778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schut AF, Janssen JA, Deinum J, Vergeer JM, Hofman A, Lamberts SW, Oostra BA, Pols HA, Witteman JC, van Duijn CM. Polymorphism in the Promoter Region of the Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Gene Is Related to Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity in Subjects with Hypertension. Stroke. 2003;34:1623–1627. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000076013.00240.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yazdanpanah M, Rietveld I, Janssen JA, Njajou OT, Hofman A, Stijnen T, Pols HA, Lamberts SW, Witteman JC, van Duijn CM. An Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Promoter Polymorphism Is Associated with Increased Mortality in Subjects with Myocardial Infarction in an Elderly Caucasian Population. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1274–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yazdanpanah M, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Janssen JA, Rietveld I, Hofman A, Stijnen T, Pols HA, Lamberts SW, Witteman JC, van Duijn CM. Igf-I Gene Promoter Polymorphism Is a Predictor of Survival after Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:751–756. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allen NE, Davey GK, Key TJ, Zhang S, Narod SA. Serum Insulin-Like Growth Factor I (Igf-I) Concentration in Men Is Not Associated with the Cytosine-Adenosine Repeat Polymorphism of the Igf-I Gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:319–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frayling TM, Hattersley AT, McCarthy A, Holly J, Mitchell SM, Gloyn AL, Owen K, Davies D, Smith GD, Ben-Shlomo Y. A Putative Functional Polymorphism in the Igf-I Gene: Association Studies with Type 2 Diabetes, Adult Height, Glucose Tolerance, and Fetal Growth in U.K. Populations. Diabetes. 2002;51:2313–2316. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Selman C, Lingard S, Choudhury AI, Batterham RL, Claret M, Clements M, Ramadani F, Okkenhaug K, Schuster E, Blanc E, Piper MD, Al-Qassab H, Speakman JR, Carmignac D, Robinson IC, Thornton JM, Gems D, Partridge L, Withers DJ. Evidence for Lifespan Extension and Delayed Age-Related Biomarkers in Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 Null Mice. Faseb J. 2008;22:807–818. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9261com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kenyon CJ. The Genetics of Ageing. Nature. 2010;464:504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suh Y, Atzmon G, Cho MO, Hwang D, Liu B, Leahy DJ, Barzilai N, Cohen P. Functionally Significant Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Receptor Mutations in Centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3438–3442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705467105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending Healthy Life Span--from Yeast to Humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, Leneuve P, Geloen A, Even PC, Cervera P, Le Bouc Y. Igf-1 Receptor Regulates Lifespan and Resistance to Oxidative Stress in Mice. Nature. 2003;421:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bokov AF, Garg N, Ikeno Y, Thakur S, Musi N, DeFronzo RA, Zhang N, Erickson RC, Gelfond J, Hubbard GB, Adamo ML, Richardson A. Does Reduced Igf-1r Signaling in Igf1r+/− Mice Alter Aging? PLoS One. 2011;6:e26891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guevara-Aguirre J, Balasubramanian P, Guevara-Aguirre M, Wei M, Madia F, Cheng CW, Hwang D, Martin-Montalvo A, Saavedra J, Ingles S, de Cabo R, Cohen P, Longo VD. Growth Hormone Receptor Deficiency Is Associated with a Major Reduction in Pro-Aging Signaling, Cancer, and Diabetes in Humans. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:70ra13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H, Dimayuga P, Yamashita M, Yano J, Fournier M, Lewis M, Cercek B. Arterial Injury in Mice with Severe Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (Igf-1) Deficiency. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2002;7:227–233. doi: 10.1177/107424840200700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu B, Zhao G, Witte DP, Hui DY, Fagin JA. Targeted Overexpression of Igf-I in Smooth Muscle Cells of Transgenic Mice Enhances Neointimal Formation through Increased Proliferation and Cell Migration after Intraarterial Injury. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3598–3606. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harrington SC, Simari RD, Conover CA. Genetic Deletion of Pregnancy-Associated Plasma Protein-a Is Associated with Resistance to Atherosclerotic Lesion Development in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice Challenged with a High-Fat Diet. Circ Res. 2007;100:1696–1702. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.146183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nichols TC, Busby WH, Jr, Merricks E, Sipos J, Rowland M, Sitko K, Clemmons DR. Protease-Resistant Insulin-Like Growth Factor (Igf)-Binding Protein-4 Inhibits Igf-I Actions and Neointimal Expansion in a Porcine Model of Neointimal Hyperplasia. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5002–5010. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Razuvaev A, Henderson B, Girnita L, Larsson O, Axelson M, Hedin U, Roy J. The Cyclolignan Picropodophyllin Attenuates Intimal Hyperplasia after Rat Carotid Balloon Injury by Blocking Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Receptor Signaling. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Resch ZT, Simari RD, Conover CA. Targeted Disruption of the Pregnancy-Associated Plasma Protein-a Gene Is Associated with Diminished Smooth Muscle Cell Response to Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I and Resistance to Neointimal Hyperplasia after Vascular Injury. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5634–5640. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Niu XL, Li J, Hakim ZS, Rojas M, Runge MS, Madamanchi NR. Leukocyte Antigen-Related Deficiency Enhances Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Signaling in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Promotes Neointima Formation in Response to Vascular Injury. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19808–19819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zadelaar S, Kleemann R, Verschuren L, de Vries-Van der Weij J, van der Hoorn J, Princen HM, Kooistra T. Mouse Models for Atherosclerosis and Pharmaceutical Modifiers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1706–1721. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adamo ML, Ma X, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Donahue LR, Beamer WG, Rosen CJ. Genetic Increase in Serum Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I (Igf-I) in C3h/Hej Compared with C57bl/6j Mice Is Associated with Increased Transcription from the Igf-I Exon 2 Promoter. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2944–2955. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nichols TC, du Laney T, Zheng B, Bellinger DA, Nickols GA, Engleman W, Clemmons DR. Reduction in Atherosclerotic Lesion Size in Pigs by Alphavbeta3 Inhibitors Is Associated with Inhibition of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I-Mediated Signaling. Circ Res. 1999;85:1040–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ye P, D'Ercole J. Insulin-Like Growth Factor I (Igf-I) Regulates Igf Binding Protein-5 Gene Expression in the Brain. Endocrinology. 1998;139:65–71. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sukhanov S, Higashi Y, Shai SY, Blackstock C, Galvez S, Vaughn C, Titterington J, Delafontaine P. Differential Requirement for Nitric Oxide in Igf-1-Induced Anti-Apoptotic, Anti-Oxidant and Anti-Atherosclerotic Effects. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3065–3072. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Titterington JS, Sukhanov S, Higashi Y, Vaughn C, Bowers C, Delafontaine P. Growth Hormone-Releasing Peptide-2 Suppresses Vascular Oxidative Stress in Apoe−/− Mice but Does Not Reduce Atherosclerosis. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5478–5487. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andersson IJ, Ljungberg A, Svensson L, Gan LM, Oscarsson J, Bergstrom G. Increased Atherosclerotic Lesion Area in Apoe Deficient Mice Overexpressing Bovine Growth Hormone. Atherosclerosis. 2006;188:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Payne JA, Reckelhoff JF, Khalil RA. Role of Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Reduction of No-Cgmp-Mediated Vascular Relaxation in Shr. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R542–R551. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shai SY, Sukhanov S, Higashi Y, Vaughn C, Rosen CJ, Delafontaine P. Low Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Increases Atherosclerosis in Apoe-Deficient Mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1898–H1906. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01081.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khan AS, Sane DC, Wannenburg T, Sonntag WE. Growth Hormone, Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and the Aging Cardiovascular System. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shai SY, Sukhanov S, Higashi Y, Vaughn C, Kelly J, Delafontaine P. Smooth Muscle Cell-Specific Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Overexpression in Apoe−/− Mice Does Not Alter Atherosclerotic Plaque Burden but Increases Features of Plaque Stability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1916–1924. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Willis PE, Chadan SG, Baracos V, Parkhouse WS. Restoration of Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Action in Skeletal Muscle of Old Mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E525–E530. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.3.E525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cao JJ, Kurimoto P, Boudignon B, Rosen C, Lima F, Halloran BP. Aging Impairs Igf-I Receptor Activation and Induces Skeletal Resistance to Igf-I. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1271–1279. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Elhadd TA, Abdu TA, Oxtoby J, Kennedy G, McLaren M, Neary R, Belch JJ, Clayton RN. Biochemical and Biophysical Markers of Endothelial Dysfunction in Adults with Hypopituitarism and Severe Gh Deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4223–4232. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Perticone M, Laino I, Miceli S, Care I, Galiano Leone G, Andreozzi F, Maio R, Sesti G. Low-Plasma Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Levels Are Associated with Impaired Endothelium-Dependent Vasodilatation in a Cohort of Untreated, Hypertensive Caucasian Subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2806–2810. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fryburg DA. Ng-Monomethyl-L-Arginine Inhibits the Blood Flow but Not the Insulin-Like Response of Forearm Muscle to Igf-I: Possible Role of Nitric Oxide in Muscle Protein Synthesis. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1319–1328. doi: 10.1172/JCI118548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Imrie H, Abbas A, Viswambharan H, Rajwani A, Cubbon RM, Gage M, Kahn M, Ezzat VA, Duncan ER, Grant PJ, Ajjan R, Wheatcroft SB, Kearney MT. Vascular Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Resistance and Diet-Induced Obesity. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4575–4582. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Holly JM, Amiel SA, Sandhu RR, Rees LH, Wass JA. The Role of Growth Hormone in Diabetes Mellitus. J Endocrinol. 1988;118:353–364. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1180353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Michell BJ, Griffiths JE, Mitchelhill KI, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Tiganis T, Bozinovski S, de Montellano PR, Kemp BE, Pearson RB. The Akt Kinase Signals Directly to Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:845–848. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Elzaouk L, Leimbacher W, Turri M, Ledermann B, Burki K, Blau N, Thony B. Dwarfism and Low Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Due to Dopamine Depletion in Pts−/− Mice Rescued by Feeding Neurotransmitter Precursors and H4-Biopterin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28303–28311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tanaka J, Koshimura K, Murakami Y, Kato Y. Possible Involvement of Tetrahydrobiopterin in the Trophic Effect of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 on Rat Pheochromocytoma-12 (Pc12) Cells. Neurosci Lett. 2002;328:201–203. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bailey-Downs LC, Sosnowska D, Toth P, Mitschelen M, Gautam T, Henthorn JC, Ballabh P, Koller A, Farley JA, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Growth Hormone and Igf-1 Deficiency Exacerbate High-Fat Diet-Induced Endothelial Impairment in Obese Lewis Dwarf Rats: Implications for Vascular Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:553–564. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Blankenberg S, Rupprecht HJ, Bickel C, Torzewski M, Hafner G, Tiret L, Smieja M, Cambien F, Meyer J, Lackner KJ. Glutathione Peroxidase 1 Activity and Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1605–1613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abbas A, Imrie H, Viswambharan H, Sukumar P, Rajwani A, Cubbon RM, Gage M, Smith J, Galloway S, Yuldeshava N, Kahn M, Xuan S, Grant PJ, Channon KM, Beech DJ, Wheatcroft SB, Kearney MT. The Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Receptor Is a Negative Regulator of Nitric Oxide Bioavailability and Insulin Sensitivity in the Endothelium. Diabetes. 2011;60:2169–2178. doi: 10.2337/db11-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li Y, Higashi Y, Itabe H, Song YH, Du J, Delafontaine P. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Receptor Activation Inhibits Oxidized Ldl-Induced Cytochrome C Release and Apoptosis Via the Phosphatidylinositol 3 Kinase/Akt Signaling Pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2178–2184. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099788.31333.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hayashi K, Saga H, Chimori Y, Kimura K, Yamanaka Y, Sobue K. Differentiated Phenotype of Smooth Muscle Cells Depends on Signaling Pathways through Insulin-Like Growth Factors and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28860–28867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu ZP, Wang Z, Yanagisawa H, Olson EN. Phenotypic Modulation of Smooth Muscle Cells through Interaction of Foxo4 and Myocardin. Dev Cell. 2005;9:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Du J, Peng T, Scheidegger KJ, Delafontaine P. Angiotensin Ii Activation of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor Transcription Is Mediated by a Tyrosine Kinase-Dependent Redox-Sensitive Mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2119–2126. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tabet F, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation by Hydrogen Peroxide Is Mediated through Tyrosine Kinase-Dependent, Protein Kinase C-Independent Pathways in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: Upregulation in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2005–2012. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000185715.60788.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Azar ZM, Mehdi MZ, Srivastava AK. Activation of Insulin-Like Growth Factor Type-1 Receptor Is Required for H2o2-Induced Pkb Phosphorylation in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:777–786. doi: 10.1139/y06-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gorlach A, Brandes RP, Bassus S, Kronemann N, Kirchmaier CM, Busse R, Schini-Kerth VB. Oxidative Stress and Expression of P22phox Are Involved in the up-Regulation of Tissue Factor in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Response to Activated Platelets. Faseb J. 2000;14:1518–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Loh K, Deng H, Fukushima A, Cai X, Boivin B, Galic S, Bruce C, Shields BJ, Skiba B, Ooms LM, Stepto N, Wu B, Mitchell CA, Tonks NK, Watt MJ, Febbraio MA, Crack PJ, Andrikopoulos S, Tiganis T. Reactive Oxygen Species Enhance Insulin Sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2009;10:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gardner CD, Eguchi S, Reynolds CM, Eguchi K, Frank GD, Motley ED. Hydrogen Peroxide Inhibits Insulin Signaling in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:836–842. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0322807-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Clarke MC, Figg N, Maguire JJ, Davenport AP, Goddard M, Littlewood TD, Bennett MR. Apoptosis of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Induces Features of Plaque Vulnerability in Atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2006;12:1075–1080. doi: 10.1038/nm1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clarke MC, Littlewood TD, Figg N, Maguire JJ, Davenport AP, Goddard M, Bennett MR. Chronic Apoptosis of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Accelerates Atherosclerosis and Promotes Calcification and Medial Degeneration. Circ Res. 2008;102:1529–1538. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Okura Y, Brink M, Zahid AA, Anwar A, Delafontaine P. Decreased Expression of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Apoptosis of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Human Atherosclerotic Plaque. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1777–1789. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang J, Razuvaev A, Folkersen L, Hedin E, Roy J, Brismar K, Hedin U. The Expression of Igfs and Igf Binding Proteins in Human Carotid Atherosclerosis, and the Possible Role of Igf Binding Protein-1 in the Regulation of Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jia G, Cheng G, Gangahar DM, Agrawal DK. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Tnf-Alpha Regulate Autophagy through C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase and Akt Pathways in Human Atherosclerotic Vascular Smooth Cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:448–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Takahashi T, Kalka C, Masuda H, Chen D, Silver M, Kearney M, Magner M, Isner JM, Asahara T. Ischemia- and Cytokine-Induced Mobilization of Bone Marrow-Derived Endothelial Progenitor Cells for Neovascularization. Nat Med. 1999;5:434–438. doi: 10.1038/7434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rauscher FM, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Davis BH, Wang T, Gregg D, Ramaswami P, Pippen AM, Annex BH, Dong C, Taylor DA. Aging, Progenitor Cell Exhaustion, and Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2003;108:457–463. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000082924.75945.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thum T, Hoeber S, Froese S, Klink I, Stichtenoth DO, Galuppo P, Jakob M, Tsikas D, Anker SD, Poole-Wilson PA, Borlak J, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Age-Dependent Impairment of Endothelial Progenitor Cells Is Corrected by Growth-Hormone-Mediated Increase of Insulin-Like Growth-Factor-1. Circ Res. 2007;100:434–443. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257912.78915.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tilki D, Hohn HP, Ergun B, Rafii S, Ergun S. Emerging Biology of Vascular Wall Progenitor Cells in Health and Disease. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Degens H. The Role of Systemic Inflammation in Age-Related Muscle Weakness and Wasting. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:28–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hammers DW, Matheny RW, Jr, Sell C, Adamo ML, Walters TJ, Estep JS, Farrar RP. Impairment of Igf-I Expression and Anabolic Signaling Following Ischemia/Reperfusion in Skeletal Muscle of Old Mice. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Matata BM, Galinanes M. Peroxynitrite Is an Essential Component of Cytokines Production Mechanism in Human Monocytes through Modulation of Nuclear Factor-Kappa B DNA Binding Activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2330–2335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Succurro E, Andreozzi F, Sciacqua A, Hribal ML, Perticone F, Sesti G. Reciprocal Association of Plasma Igf-1 and Interleukin-6 Levels with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Nondiabetic Subjects. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1886–1888. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jeschke MG, Herndon DN, Barrow RE. Insulin-Like Growth Factor I in Combination with Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3 Affects the Hepatic Acute Phase Response and Hepatic Morphology in Thermally Injured Rats. Ann Surg. 2000;231:408–416. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Spies M, Wolf SE, Barrow RE, Jeschke MG, Herndon DN. Modulation of Types I and Ii Acute Phase Reactants with Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1/Binding Protein-3 Complex in Severely Burned Children. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:83–88. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roubenoff R, Parise H, Payette HA, Abad LW, D'Agostino R, Jacques PF, Wilson PW, Dinarello CA, Harris TB. Cytokines, Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1, Sarcopenia, and Mortality in Very Old Community-Dwelling Men and Women: The Framingham Heart Study. Am J Med. 2003;115:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Serri O, Li L, Maingrette F, Jaffry N, Renier G. Enhanced Lipoprotein Lipase Secretion and Foam Cell Formation by Macrophages of Patients with Growth Hormone Deficiency: Possible Contribution to Increased Risk of Atherogenesis? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:979–985. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Renier G, Clement I, Desfaits AC, Lambert A. Direct Stimulatory Effect of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I on Monocyte and Macrophage Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Production. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4611–4618. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hochberg Z, Hertz P, Maor G, Oiknine J, Aviram M. Growth Hormone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Increase Macrophage Uptake and Degradation of Low Density Lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 1992;131:430–435. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.1.1612024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kirstein M, Aston C, Hintz R, Vlassara H. Receptor-Specific Induction of Insulin-Like Growth Factor I in Human Monocytes by Advanced Glycosylation End Product-Modified Proteins. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:439–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI115879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fournier T, Riches DW, Winston BW, Rose DM, Young SK, Noble PW, Lake FR, Henson PM. Divergence in Macrophage Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I (Igf-I) Synthesis Induced by Tnf-Alpha and Prostaglandin E2. J Immunol. 1995;155:2123–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kotsis V, Stabouli S, Karafillis I, Nilsson P. Early Vascular Aging and the Role of Central Blood Pressure. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1847–1853. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834a4d9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Standley PR, Zhang F, Ram JL, Zemel MB, Sowers JR. Insulin Attenuates Vasopressin-Induced Calcium Transients and a Voltage-Dependent Calcium Response in Rat Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1230–1236. doi: 10.1172/JCI115426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Galderisi M, Vitale G, Lupoli G, Barbieri M, Varricchio G, Carella C, de Divitiis O, Paolisso G. Inverse Association between Free Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Isovolumic Relaxation in Arterial Systemic Hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;38:840–845. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.091776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tivesten A, Bollano E, Andersson I, Fitzgerald S, Caidahl K, Sjogren K, Skott O, Liu JL, Mobini R, Isaksson OG, Jansson JO, Ohlsson C, Bergstrom G, Isgaard J. Liver-Derived Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Is Involved in the Regulation of Blood Pressure in Mice. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4235–4242. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vecchione C, Colella S, Fratta L, Gentile MT, Selvetella G, Frati G, Trimarco B, Lembo G. Impaired Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Vasorelaxant Effects in Hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;37:1480–1485. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.6.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hongo K, Nakagomi T, Kassell NF, Sasaki T, Lehman M, Vollmer DG, Tsukahara T, Ogawa H, Torner J. Effects of Aging and Hypertension on Endothelium-Dependent Vascular Relaxation in Rat Carotid Artery. Stroke. 1988;19:892–897. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.7.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hasdai D, Holmes DR, Jr, Richardson DM, Izhar U, Lerman A. Insulin and Igf-I Attenuate the Coronary Vasoconstrictor Effects of Endothelin-1 but Not of Sarafotoxin 6c. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;39:644–650. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Duerrschmidt N, Wippich N, Goettsch W, Broemme HJ, Morawietz H. Endothelin-1 Induces Nad(P)H Oxidase in Human Endothelial Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:713–717. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li L, Fink GD, Watts SW, Northcott CA, Galligan JJ, Pagano PJ, Chen AF. Endothelin-1 Increases Vascular Superoxide Via Endothelin(a)-Nadph Oxidase Pathway in Low-Renin Hypertension. Circulation. 2003;107:1053–1058. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051459.74466.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wedgwood S, McMullan DM, Bekker JM, Fineman JR, Black SM. Role for Endothelin-1-Induced Superoxide and Peroxynitrite Production in Rebound Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Inhaled Nitric Oxide Therapy. Circ Res. 2001;89:357–364. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.094983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Frank HJ, Levin ER, Hu RM, Pedram A. Insulin Stimulates Endothelin Binding and Action on Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1092–1097. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.3.8365355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kwok CF, Juan CC, Shih KC, Hwu CM, Jap TS, Ho LT. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Increases Endothelin Receptor a Levels and Action in Cultured Rat Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:1126–1134. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]