Abstract

Background

Although the poor oral health of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) constitutes a significant health disparity in the United States, few interventions to date have produced lasting results. Moreover, there is minimal application of planning models to inform and design a theory-based strategy that has the potential to be effective and sustainable in this population.

Methods

The PRECEDE-PROCEED planning model is being used to design and evaluate an oral health strategy for adults with IDD. The PRECEDE component involves assessing social, epidemiological, behavioral, environmental, educational, and ecological factors that informed the development of an intervention with underlying social cognitive theory assumptions. The PROCEED component consists of pilot-testing and evaluating the implementation of the strategy, its impact on mediators and outcomes of the population under study.

Results

A The PRECEDE assessment and strategy design results are presented including a conceptual framework and oral health strategy that are linked to social cognitive theory and Health Action Process Approach. We have developed a strategy consisting of a planned actions, capacity building, environmental adaptations, and caregiver reinforcement within group homes. The strategy is designed to increase caregiver self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, and behavioral capability, and also to create environmental influences that will lead to improved self-care behavior of the adult with IDD. It is anticipated that this strategy will improve the oral health and quality of life, including respiratory health, of individuals with IDD. The planned PROCEED component of the planning model includes a description of an in-process pilot study to refine the oral health strategy, along with a future randomized controlled clinical trial to demonstrate its effectiveness.

Conclusions

The application of the PRECEDE-PROCEED planning model presented here demonstrates the feasibility of this planning model for developing and evaluating interventions for adults within the IDD population.

Keywords: Oral health, Adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, PRECEDE-PROCEED planning model, Social cognitive theory, Health Action Process Approach, Oral health strategy

The poor oral health of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) living in community settings constitutes a significant health disparity in the United States (1, 2). Efforts have been made to develop and evaluate various strategies to improve the oral hygiene and oral health of this vulnerable population with minimal to moderate success (3-7). None of these interventions used a planning model or theory-based behavior change intervention for caregivers of individuals with IDD. To the best of our knowledge there are only a few reports of how a planning model is used in dental public health (8, 9), but these reports are not used to develop a theory-based oral health strategy or intervention for individuals with IDD.

Planning, designing, and evaluating interventions to impact public dental health can be a challenging and time-consuming undertaking. The National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) places emphasis on the importance of using intervention planning models such as PRECEDE-PROCEED, the role of health behavior theory in developing interventions, and mediators, moderators, and testing for mechanisms of action. Moreover, the NIDCR strongly encourages investigators “to utilize methods that allow for a test of mechanisms of action. Mechanisms of action are causal explanations for behavior. These are distinguished from correlates, predictors, risk and protective factors, etc., which may be candidate mechanisms, but have not been demonstrated to have a causal link with the outcome(s) of interest” (http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/Research/DER/bssrb.htm) (10).

The PRECEDE-PROCEED model can be used to design and evaluate an oral health promotion effort. The PRECEDE component allows a researcher to work backward from the ultimate goal of the research (distal outcomes) to create a blueprint to instruct the formation of the intervention or strategy (11). The PROCEED component may lay out the evaluation, including pilot study and efficacy study methodologies. The model has been used by Watson and colleagues to design an oral health promotion program in an inner-city Latino community (12); by Cannick and colleagues to guide the training of health professional students (13); and by Sato (9) and Dharamsi (14) to analyze attitudes and prediction factors regarding oral health. Although this planning model has been applied in oral health, there are others such as RE-AIM (15) and the Stage Model of Behavioral Therapy (16) that achieve the same goal of organizing the framework for an oral health promotion program. It is important to remember that planning models are not health behavior theories because they cannot test mechanisms of action or causal relationships (10).

Of particular importance to the PRECEDE-PROCEED planning model is the role of theory in creating a conceptual framework that guides construction of an intervention and its evaluation (11). We believe it is important to develop a planned intervention for oral health that draws from multiple theories. Several behavioral change theories have reportedly been used in designing oral health intervention strategies. One of the most common is Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), which posits that the process of human adaptation and change is a dynamic interplay of personal, behavioral, and environmental factors (17). The literature suggests that interventions designed to impact these three factors are more likely to produce desired changes in outcomes (17-19). Personal factors may play a major role in a person's capability to perform behaviors. Environmental factors may hinder a person's ability to adequately perform a behavior and impact their self-efficacy (a personal factor) in performing the behavior of interest. The reciprocal nature of these determinants of human functioning make it possible to design interventions to impact personal, behavioral, or environmental factors. Schwarzer's Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) (20, 21) uses social cognitive constructs, including outcome expectancies and self-efficacy as well as planned actions, in predicting behavior change. This approach provides a framework for prediction of behavior and reflects the assumed causal mechanisms of behavior change (21). HAPA has been used to describe, explain, and predict changes in health behaviors in a variety of settings (21) including oral health (22).

METHODS

This article presents the application of the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model (23) as a planning tool for oral health. (11) PRECEDE (Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis) outlines a diagnostic planning process to assist in the development of targeted and focused public health programs. PROCEED (Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development) highlights the implementation and evaluation of the intervention designed in the PRECEDE component. Although an eight-phase planning model as presented in the literature is being used, we have tweaked the PROCEED component (phase 5) to include pilot testing for revising the original strategy before implementing and evaluating the intended processes, impact, and outcomes of the intervention. Soliciting input from key informants of the community actively involved with the population of interest is important in all phases of assessment. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Louisville reviewed the research (11.0338) and approved the study including all consent forms for the pilot test of the oral health strategy.

PRECEDE Planning Model Component

We used an extensive literature review and informal discussions with selected community leaders and staff who work with IDD population in a targeted Midwestern city. These participants consisted of one vice president, one residential director, and three caregivers working in group homes of one IDD service organization, and two dentists and three dental hygienists/assistants who work with IDD population. In total, interview data were collected from 10 IDD and dental care persons. Each of these participants engaged in an informal discussion that posed questions central to the assessment of phases 1-4. A content analysis of the literature and discussions produced the results presented later.

Phase 1 - Social Assessment

The PRECEDE portion of the Model begins with diagnostic activities that identify desirable outcomes or goals of the intervention or ask, “What can be achieved?” These activities determined the primary or distal outcomes of the oral health strategy for the individual with disabilities.

Phase 2 - Epidemiological, Behavioral, and Environmental Assessment

We searched the literature and asked questions of the selected community leaders and healthcare staff noted above about what problems or issues affect the oral health-related quality of life for persons with IDD? - OR - What needs to change to achieve optimal oral health for these individuals? This phase determined epidemiological, behavioral, and environmental factors that may well have an impact on the oral health and quality of life of individuals with IDD. This phase contributed to the identification of the factors that an oral health strategy needs to impact (mediating outcomes) in order to achieve the primary outcomes.

Phase 3 - Educational and Ecological Assessment

This phase determined factors that, if modified, would be most likely to result in behavior change and to sustain this change process. These factors are generally classified as predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors (23). “Predisposing factors are antecedents to behavior that provide the rationale or motivation for the behavior” (p.415) (24) and include individuals’ existing skills and self-efficacy. “Enabling factors are antecedents to behavioral or environmental change that allow a motivation or environmental policy to be realized” (p.415) (24) and may include new skills, services, resources, and programs. Reinforcing factors are those factors following a behavior that provide continuing reward or incentive for the persistence or repetition of the behavior” (p.415) (24) and they include social support, praise, and vicarious reinforcement.

Change theory(ies) for designing the intervention after this assessment includes individual, interpersonal, and community theories. Individual-level theories are best used to address predisposing factors, while interpersonal-level theories, such as social cognitive theory, address reinforcing factors well; community-level theories are most appropriate for addressing enabling factors. (24).

Phase 4 - Intervention Alignment and Administrative and Policy Assessment

Phase 4a - Intervention Alignment

This phase matched appropriate strategies and interventions with the projected changes and outcomes identified in phases 1-3 (23). Using assessment results from phases 1-3, the oral health strategy presented in the results section emerged as our intervention of choice.

Phase 4b - Administrative and Policy Assessment

In this phase, resources, organizational barriers and facilitators, and policies that were needed for the strategy or intervention implementation and sustainability were identified (24). The organizational and environmental systems that could affect the desired outcomes (enabling factors) were taken into account. The administrative diagnosis assessed resources, policies, budgetary needs, and organizational situations that could hinder or facilitate the development and implementation of the strategy or program (25). The policy diagnosis assessed the compatibility of the oral health strategy with those of the organizations providing services to individuals with IDD.

PROCEED Planning Model Component

Phase 5 - Pilot Study

Although we did not recognize the inclusion of a pilot study as essential to the PRECEDE-PROCEED planning model, we believe that it is an important planning phase. These results and lessons learned are important to revising both the pilot oral health strategy and its evaluation for an efficacy study. To this end, we have provided a description of our inprogress pilot study in the results section of this article.

Phase 6 - Implementation

This phase presents a description of the implementation of the oral health strategy in an efficacy study. Key roles in the implementation phase are highlighted.

Phases 7 and 8 - Process and Outcome Evaluation

Our planned efficacy study is designed as a cluster randomized control trial that includes a process and outcome evaluation. The study of both the implementation process and outcome achievements is important. The implementation process assessment should address the amount of intervention exposure of the oral health strategy (dosage), extent to which an intervention is implemented as designed (fidelity), and participant appraisal of intervention quality or usefulness (participant reaction), all of which are discussed in the evaluation literature (26). In addition, we measured adequacy of implementation by recruiting an expert panel who has published implementation articles to assess the adequacy of our implementation (27). The outcome evaluation should be composed of an assessment of oral health strategy direct effects on outcomes, mediation of outcomes designated as mechanisms of change, and moderation of contextual factors. Our evaluation plans are highlighted in the results section of this article.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

We present the results of the PRECEDE component of the planning model being demonstrated. The planned PROCEED component is also described.

PRECEDE Phase 1 - Social Assessment

Our social diagnosis began while we were conducting previous studies in long-term care facilities and in community settings for persons with IDD. During this planning phase, we solicited input from the community (direct care staff, administrators, and dental professionals who care for persons with IDD), and they all stated that poor oral health is one of the greatest unmet health care needs of their population (28). The community was also becoming aware of the association of aspiration of bacteria from the mouth into the lungs with respiratory infections, and it wanted to improve oral health and oral health-related quality of life including respiratory health.

PRECEDE Phase 2 - Epidemiological, Behavioral, and Environmental Assessment

A. Epidemiological Assessment

Historically, children and adults with mild to profound intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) either lived at home or were placed in large state institutions with fully staffed medical and dental facilities and stable, well-trained workers. Over the past several decades, a major effort to deinstitutionalize these individuals and place them in smaller community residences has been successful. Although overall quality of life may have been improved for this vulnerable population, their access to dental care has become limited or non-existent, and their oral health has suffered (29). A majority of persons with IDD are insured by Medicaid, and many dentists either do not accept Medicaid or do not believe they are adequately trained to treat special-needs patients.

The oral health of this population is compromised not only by the lack of preventive dental treatment every six months but also by their inability to adequately brush and/or floss their own teeth. The oral hygiene provided or supervised by caregivers is thus critical to maintaining oral health and reducing the need for extensive restoration or extraction of teeth. Providing oral care for individuals with IDD is challenging, not only because they may have physical impairments but also because they exhibit uncooperative behaviors (30). Caregivers often only clean the anterior teeth, ignoring the posterior teeth and causing the posterior oropharyngeal area to be at risk for colonization with bacteria and infection (31-33).

Swallowing disorders (dysphagia) are common in persons with developmental disabilities, putting them at risk for aspiration and respiratory infections, a major cause of morbidity and mortality in this population (34, 35). Similar to what occurs with elderly persons residing in nursing homes and patients in intensive care units, (36, 37) potentially pathogenic bacteria colonize the oropharyngeal area of people with IDD. (38) Rigorous oral hygiene can reduce oral colonization with bacteria and yeasts, thus reducing pneumonia in at-risk individuals (39, 40).

Although social initiatives that focus on increasing the number of dentists who will treat special-needs patients are needed, it remains the purview of the caregiver to supervise and/or provide oral hygiene. Thus, theoretically sound strategies or interventions that address the caregiver's behavioral capability in providing oral health support may reduce disparities and could be imperative for improving health and quality of life in this population.(28, 41)

B. Behavioral Assessment

We determined key behavioral factors of the individual with IDD that affect mechanisms impacting their oral health and quality of life. Individuals with IDD have physical, behavioral, and cognitive disabilities that negatively impact their ability to perform their own oral hygiene practices at an optimal level (42). Those with mild disability, who are capable of performing their oral hygiene, frequently do not prioritize brushing or flossing their teeth on a regular basis and often do not know how to perform these practices optimally. Those with moderate to profound disabilities may be able to partially perform their oral hygiene, but they often require assistance and/or supervision provided by caregivers to adequately clean their teeth. Also, due to their emotional and unpredictable episodes, as the caregivers call them, all IDD persons may exhibit uncooperative and/or resistant behaviors from time to time that prevent them from engaging in oral hygiene practices regularly.

Like the parents of very young children, caregivers also play a key role in shaping the behavior of adults with IDD, who frequently have a mental age lower than that of a 5-year-old child without disability. Adults with disabilities generally do not achieve an acceptable standard of oral health on their own. However, Shaw and colleagues demonstrated that if these IDD persons are supervised, encouraged, and motivated by caregivers, their oral hygiene can be improved (43). Caregiver behavior in the form of support of the adult with IDD oral health, coupled with the caregiver's self-efficacy in promoting the adult's self-care behavior, should improve the residents’ oral hygiene practices.

C. Environmental Assessment

We identified environmental barriers or influences that are key factors in social cognitive theory. First, the physical environment in group homes is frequently not conducive to optimal oral hygiene practices. Materials available for oral hygiene usually include only over-the-counter toothbrushes, which may not be adequate to address the residents’ disabilities.

Second, our assessment of the social environment in the group homes determined that there were no policies or procedures in place concerning oral health or oral hygiene practices. Implementation of policies and procedures related to oral health by the organizations that manage the group homes would provide all caregivers with guidelines for and expectations of their performance. We found that all caregivers are responsible for preparing either breakfast or dinner during the week, and on weekends they must prepare all meals and/or take the residents out to lunch. As such, they are the primary persons responsible for determining what the residents eat and drink while in their care and they hold the responsibility of ensuring the availability of an appropriate diet in the group home setting to reduce the risk of tooth decay.

PRECEDE Phase 3 - Educational and Ecological Assessment

A. Predisposing Factors

We identified potential factors that may need to be modified to effect changes in caregiver behavior. We identified these factors based on discussions with our community leaders and a review of the literature. These social cognitive factors-self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, and behavioral capability-may be important because merely providing education to caregivers in oral hygiene provision for dependent persons has been shown to be minimally effective in improving oral health (5, 44).

Self-efficacy is defined as “people's judgments of the capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances” (17, p. 391). Self-efficacy in oral hygiene, or the perceived ability or confidence of an individual to perform good tooth brushing and flossing, has been shown to be important in previous oral health studies (45-48). Caregivers reported to us that they had knowledge of the importance of oral health but stated that they were not comfortable supervising or assisting the residents in oral hygiene procedures. The literature reports that parental/caregiver self-efficacy in supporting or supervising young children's oral hygiene can be a strong predictor of parental/caregiver oral hygiene support (49, 50).

Outcome expectancies are defined as “a person's estimate that a given behavior will lead to certain outcomes” (p.193) (51) or beliefs about the likelihood and value of behavioral choices. Caregiver psychosocial factors, such as expectations of poor oral health in their residents/clients, may serve as a barrier to optimal oral hygiene behavior (52-54). Outcome expectancies may be impacted by individuals seeing like individuals perform the behavior and/or encouragement to them that they are capable of performing the behavior (55, 56). Demonstrations of oral health behaviors by a dental hygienist and the subsequent modeling of the behavior by the caregivers may impact their outcome expectancies of providing oral health support.

Behavioral capability is defined as someone's actual ability to perform a behavior in real-life situations. A caregiver must know what oral health support behavior is and have the skills to perform it. Informal interviews conducted with caregivers (direct care staff) in the group homes revealed that they received virtually no training or support in supervising or providing oral health services or dietary supervision for their adults with IDD. As previously stated, we know that providing only didactic training to caregivers does not result in improved resident oral health (5), which suggests that building behavioral capability is also necessary.

B. Enabling Factors

Our literature review identified factors external to the caregivers and adults with IDD that could be impacted by our strategy to improve oral health. These factors-planned action, capacity building, and environmental adaptation-would be antecedents to the behavior change we hoped to impact. We believe these enabling factors should be intervention components of our oral health strategy.

Planned action is an enabling factor that has been shown to impact caregiver behavior and is a key construct of the Health Action Process Approach (20). Interventions reported in the obesity and cardiovascular literature that begin with a plan and a behavioral contract between the parents/ caregivers and researchers to complete the plan have been effective (19, 57, 58). In addition, young children whose parents had set goals using an action plan demonstrated significantly reduced plaque scores and improved gingival health compared to a control group who had no planned actions (59). Similarly, children with plans for asthma and obesity actions showed marked improvement in their health (60, 61). Glassman and colleagues recommend that adults with IDD should have an oral health care action plan (31).

Capacity building is the process through which the abilities to do certain things are obtained, strengthened, adapted, and maintained over time (62). Capacity building was used by community health workers to promote oral health among women and mothers, and this resulted in significant changes in oral health expectancies, self-efficacy, and oral health behaviors (63). We believe that the strategy must include a comprehensive capacity-building component that will provide not only didactic training but also observational learning and skill development throughout the duration of the strategy. In addition, providing the caregiver with training and skills in dietary supervision may enable him/her to improve the oral health of the residents.

Environmental adaptation utilizing oral hygiene aids, such as special toothbrush handles for individuals who have poor coordination or diminished ability to grip, mouth props, multi-surface brushes (Surround or Collis), powered brushes, dental floss alternatives, and flavored toothpaste, may also improve caregiver behavioral capability and the oral health of adults with IDD (64). Caregivers may also need to alter the physical environment where they provide oral hygiene for residents who are partially or fully dependent by performing these procedures in an area of the home other than the restroom (31). Reclining the resident on a bean bag or sofa can facilitate resident's cooperation and reduce potential for injury to the resident or care-giver. Finally, the social environment in the home could be adapted by the implementation of policies and procedures regarding oral health to influence the caregivers’ behavior.

C. Reinforcing Factors

Reinforcing a desired behavior is an important construct in social cognitive theory, and it encourages a behavior to be repeated and sustained. We identified two intervention components-coaching and monitoring oral health practices-that could impact caregiver self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, behavioral capabilities, and environmental influences.

The literature suggests that ongoing coaching of the caregiver and resident is essential to the success of an oral health strategy for persons with IDD (5). There is some evidence that continued follow-up with caregivers and feedback on plaque removal are needed to improve oral hygiene practices, as well as to effect significant and sustainable change in oral health (6, 43, 65).

In addition to coaching, a web-based monitoring system can enable the ability to provide constructive reinforcement to caregivers on a regular basis. Residents also need reinforcement from the caregiver when they perform their oral hygiene or when they cooperate with caregiver-provided oral hygiene (43). The proposed oral health strategy will also include coaching and monitoring of the caregivers, and building the caregiver's capacity to reinforce and monitor the residents’ oral health and oral hygiene practices.

PRECEDE Phase 4a - Intervention Alignment

Based on the analysis of the assessments in phase 1-3, we constructed an intervention strategy. The PRECEDE activities identified predictors of the caregivers’ and individual residents’ targeted health behaviors. We then conducted a search of the literature for health behavior theories that would allow for testing of mechanisms of change and thereby inform our intervention techniques. We determined that two theories, SCT and HAPA, incorporate concepts that are aligned with the results of our assessments during PRECEDE activities.

We used four constructs from the two theories to assess their impact as mechanisms of change or mediating variables in the strategy framework: self-efficacy, behavioral capability, and environmental influences from SCT, and outcome expectancies constructs from both SCT and HAPA. We posit links between the determinants of the targeted oral health of an IDD population and our theory-based oral health strategy described below. We took into account factors identified during the PRECEDE activities including enabling factors (planned actions from HAPA, capacity building, environmental adaptation, and reinforcement from SCT). These enabling factors formed our four-component oral health strategy-planned action, capacity building, environmental adaptations, and reinforcement activities.

Planned action will involve a behavioral contract with the caregivers, who will be asked to make a contract with the research team to participate in the oral health strategy and the development, implementation, and monitoring of oral health plans for each consented individual with IDD in their care. Capacity building will be facilitated by a dental hygienist who will provide training to increase the behavioral capability of the caregiver in providing oral health support to the individuals with IDD. Environmental adaptations will occur when the hygienist works with caregivers to select and use various oral hygiene aids and dental devices to improve oral hygiene practices. The implementation of oral health policies and procedures will adapt the group home environment to impact caregiver outcome expectations. Reinforcement will occur during follow-up coaching visits by the hygienist with the caregivers and individuals with IDD, and the web-based monitoring will also provide reinforcement to the caregivers.

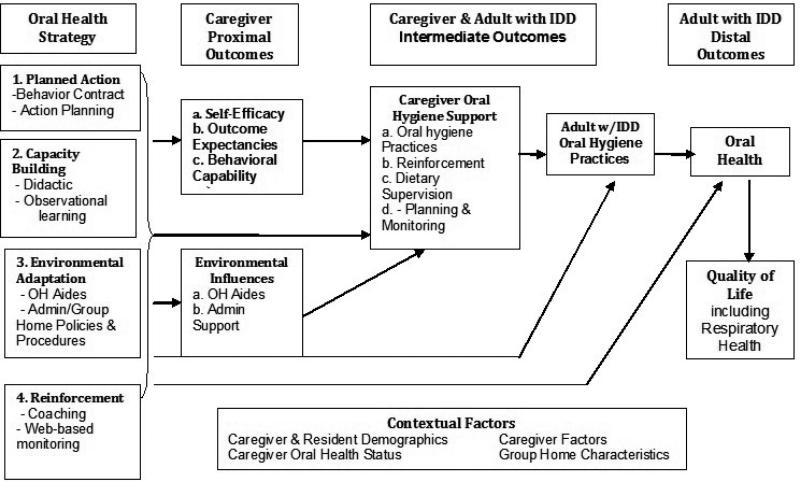

Figure 1 presents our conceptual framework, which shows the assumed interrelationships between the oral health strategy and proximal, intermediate, and distal outcomes. The framework posits that the strategy will impact caregiver proximal outcomes of self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, behavioral capabilities, and environmental influences. Assuming the caregiver proximal outcomes (i.e., mediators) are positively impacted, we posit that the oral health support of caregivers will improve, thereby improving oral hygiene practices of adults with IDDs and subsequently improving the overall oral self-care behavior of an individual with IDD according to his/her ability.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of the Oral Health Strategy for Adults with Intellectual and/or Development Disabilities.

Since there may be some strategy influence on the oral health of the adult with IDD that is not accounted for by the SCT mediators, the model also suggests that the strategy will directly affect the oral health support of caregivers. Finally, we believe that contextual factors, including demographics, caregiver oral health status, and group home environmental characteristics, may be associated with the efficacy of the strategy; therefore, these factors should be statistically controlled in a randomized controlled study and/or considered as moderators of the strategy effects.

PRECEDE Phase 4b - Administrative and Policy Assessment

We determined in our administrative assessment that an oral health strategy would need the following key factors: (1) support of the organizations that provide community services for the individual residents with IDD and (2) behavioral contracts with the Directors of Residential Services of these organizations to delineate the roles and responsibilities of these key individuals.

Our policy assessment determined that if the oral health strategy were to be successful, the following would be needed: (1) a randomized controlled trial to produce evidence of impact on oral health outcomes, (2) implementation of a monitoring policy by the organization providing services for the adults with IDD, and (3) preliminary evidence of the sustainability of the strategy.

PROCEED Model Component

The PROCEED component entails conducting a pilot study to refine the oral health strategy (phase 5a), implementing the strategy (phase 5b), and testing the efficacy of the strategy under experimental conditions (phases 6-8). The larger study would be designed to assess intervention processes (phase 6), impact on mediators (phase 7), and outcomes relating to the oral health and quality of life of adults with IDD (phase 8).

PROCEED 5 - Pilot Study

The pilot study is part of an in-process R34 grant from the NIDCR. This study is examining the oral health strategy described in this article using a pre-post intervention design only. The participants are consented caregivers and adults with IDD in 12 group homes managed by a large organizational network serving the IDD population in one Midwestern city. The pilot study assesses (a) dosage [amount of intervention exposure of each strategy component], (b) implementation fidelity [extent to which each component is implemented as designed], and (c) participant reactions [appraisal of the quality or usefulness of the strategy] that are associated with implementing the strategy over a condensed one-month time period. In addition, we are assessing change in the study outcomes as preliminary results to guide development of the final oral health strategy. Also, the reliability and validity of our process and outcome measures and the feasibility of various data-collection procedures (such as using video cameras to collect observation data in a group home setting) are being examined in this in-process NIDCR grant. The analytical strategies for the pilot test will involve the use of simple descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies and percentages for the process assessment (phase 5a) and linear or logistic regression for assessing changes in the proximal, intermediate, and distal outcomes.

PROCEED 6 - Implementation of the Oral Health Strategy

Assuming the pilot study results demonstrate the feasibility of a larger RCT study, we plan to apply for a second NIDCR grant in the near future. In sequence, the oral health strategy will be implemented after obtaining written informed consent and HIPAA authorization from the caregivers and the parents or guardians of the adults with IDD. First, a behavioral contract will be negotiated with the caregivers to participate in a program to improve the oral health of their residents.

Second, the strategy is designed to promote capacity building in the caregiver by requiring skills training in providing and/or supervising oral hygiene practices for the IDD resident, dietary supervision, and planning and monitoring goals for oral health care. All components and Key Points of the following three capacity-building parts of the intervention are included in a Manual of Procedures for the study, which is required in the NIDCR-funded pilot study. Initially, didactic training will be provided in the group homes to groups of caregivers. The training has been adapted from the Overcoming Obstacles program (5), which includes a PowerPoint presentation and a 20-minute DVD demonstrating oral hygiene and behavioral management techniques. Caregiver capacity building will continue during in-home training immediately after the didactic training and will be provided by the dental hygienist with at least two caregivers and the three adults with IDD residing in the home. The in-home training begins with a discussion of each resident's current oral hygiene practices and any existing behavioral challenges to oral health. The hygienist and caregivers will then cooperatively develop individualized oral healthcare plan goals for each resident. During this initial in-home visit the dental hygienist will provide opportunities for observational learning by performing oral hygiene procedures for each IDD resident while the caregivers watch. The caregivers will then be encouraged to model the same hygiene practices while the hygienist watches and offers suggestions for improvement, praise, reassurance, and encouragement.

Third, because each resident will have unique needs for environmental adaptation, the dental hygienist will work with each caregiver throughout the intervention to find and evaluate adaptive devices and/or behavioral strategies that will produce the greatest benefit for the resident by increasing participation and cooperation. The environment in the group homes will also be adapted by providing caregivers on-line technology to document on a daily basis the resident's self-care behavior, including oral hygiene practices and diet. The on-line technology will also facilitate reinforcement of the caregivers’ study activities.

Fourth, the dental hygienist will also assist the caregivers in selecting and assessing reinforcements that will improve IDD participant cooperation. During this time, there will also be training for the caregivers on how to record video observations and daily logs that capture the IDD residents’ oral hygiene practices. During the subsequent four in-home capacity-building visits (coaching visits), the dental hygienist will coach the caregivers in ways to improve supervising and/or providing oral hygiene practices, supervising residents’ diets, and planning and monitoring the residents’ oral health. At the end of the intervention, the caregivers and dental hygienist will review the behavioral contract, evaluating how well each caregiver met the expectations of participation in the intervention.

PROCEED 7 and 8 - Process and Outcome Evaluation

For the efficacy study, we propose an oral health strategy to be implemented over a four-month period. The implementation process measures include dosage, fidelity, and participant reaction as described above. To test for effects on the proximal outcomes or mediators/mechanisms of change (i.e., caregiver self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, behavioral capability, and environmental influence), we plan to conduct a cluster randomized controlled trial that randomly assigns group homes to experimental conditions within organizations. Outcomes will be measured at baseline, at post-implementation, and at a six-month follow-up. The control group will be implemented first over a nine-month period, followed by the intervention group over the same length of time. This will reduce contamination between the control and intervention group participants.

We estimate that approximately 80 group homes with an average of three caregivers and two to three adults with IDD must be recruited to obtain sufficient power to detect small- to medium-size effects. With such a large sample of group homes, we will need to implement the RCT in two cohorts with pairs of group homes matched and randomly assigned to control and experimental conditions within cohorts. Members of the research team have successfully used this research strategy in another large-scale NIH study (66).

The analysis of the anticipated larger RCT study will be more involved in both the process and outcome evaluations. For the process analysis (phase 7), we will produce frequency and percentages for all process measures. These results will be presented to an expert panel of 16 authors who have published implementation quality papers in order to assess the adequacy of the implementation quality of our larger study (67). Expert panels usually consist of a small number of members, which precludes performing inferential analyses from which inferences can be drawn (68). To increase our confidence in the results from our small sample of experts, we will analyze the observed data and then perform a bootstrap analysis (27, 68). Using Excel, we will draw 1,000 bootstrapped samples of size 16, sampling with replacement, for each of our results. We will calculate average test values across all bootstrapped samples, except for p values that stem from the average t-statistic.

The outcome evaluation (phase 8) will produce outcome data for caregivers and adults with IDD nested in group homes. To answer research questions about intervention direct effects, we plan to use a three-level hierarchical linear model (HLM) random intercept regressions (69), which will assess whether there have been differential changes between the intervention and control groups on proximal, intermediate, or distal outcomes. Hierarchical non-linear modeling (HNLM) will be used for dichotomous outcomes.

Phase 8 of the larger study analysis also concerns the assessment of mediating and moderating effects. We plan to use multilevel structural equation model (MSEM) procedures to determine whether social cognitive factors (e.g., caregiver self-efficacy) mediate the relationship between intervention exposure and intermediate and/or distal outcomes (70). MSEM solves for parameters at both an adult with IDD level and group home level, and constraints are placed across models to represent the effects of random variability.

CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we present an eight-phase planning model that is an adaptation of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model described in the literature. The PRECEDE component involves assessing social, epidemiological, behavioral, environmental, educational, and ecological factors that inform the development of an oral health strategy for the IDD population with underlying social cognitive theory and health action planning approach assumptions (phases 1-4). The PROCEED component consists of pilot-testing, implementing, and evaluating the implementation of the strategy and its impact on outcomes of the population under study (phases 5-8). The results of the PRECEDE assessment, a conceptual framework, and an oral health strategy are summarized. In addition, we describe the phases of our PROCEED component that will guide the refinement of the oral health strategy and the testing of the strategy under experimental conditions. Importantly, members of various sectors of the community that work with the IDD population have had input into the development of the strategy being presented.

We believe that our application of an adapted PRECEDE-PROCEED planning model will be useful to others in dental public health and to those who are working to improve the oral health of the IDD population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by a National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant R34DE022274. We wish to thank our research team members .Melissa Abadi, Henry Hood, Steve Shamblen, Kirsten Thompson, Linda Young and Brigit Zaksek for their input into the development of our oral health strategy. In addition, we thank participating members of the community, especially the Community Alternatives of Kentucky administrative staff, group home caregivers, and adults with IDD for their assistance in the diagnostic and pilot testing phases of the planning process.

REFERENCES

- 1.DHHS . Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services: National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan JP, Minihan PM, Stark PC, Finkelman MD, Yantsides KE, Park A, et al. The oral health status of 4,732 adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2012;143(8):838–46. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avenali L, Guerra F, Cipriano L, Corridore D, Otto-lenghi L. Disabled patients and oral health in Rome, Italy: long-term evaluation of educational initiatives. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2011;2(3-4):25–30. PMCID: 3314314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faulks D, Hennequin M. Evaluation of a long-term oral health program by carers of children and adults with intellectual disabilities. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20(5):199–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2000.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glassman P, Miller CE. Effect of preventive dentistry training program for caregivers in community facilities on caregiver and client behavior and client oral hygiene. N Y State Dent J. 2006;72(2):38–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange B, Cook C, Dunning D, Froeschle ML, Kent D. Improving the oral hygiene of institutionalized mentally retarded clients. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74(3):205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fickert NA, Ross D. Effectiveness of a caregiver education program on providing oral care to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;50(3):219–32. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knazan YL. Application of PRECEDE to dental health promotion for a Canadian well-elderly population. Gerodontics. 1986;2(5):180–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato K, Oda M. Analysis of the factors that affect dental health behaviour and attendance at scheduled dental check-ups using the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model. Acta Med Okayama. 2011;65(2):71–80. doi: 10.18926/AMO/45265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomar SL. Cigarette smoking does not increase the risk for early failure of dental implants. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2009;9(1):11–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crosby R, Noar SM. What is a planning model? An introduction to PRECEDE-PROCEED. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(Suppl 1):S7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson MR, Horowitz AM, Garcia I, Canto MT. A community participatory oral health promotion program in an inner-city Latino community. J Public Health Dent. 2001;61(1):34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannick GF, Horowitz AM, Garr DR, Reed SG, Neville BW, Day TA, et al. Oral cancer prevention and early detection: using the PRECEDE-PROCEED framework to guide the training of health professional students. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22(4):250–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03174125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dharamsi S, Jivani K, Dean C, Wyatt C. Oral care for frail elders: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of long-term care staff. J Dent Educ. 2009;73(5):581–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jilcott S, Ammerman A, Sommers J, Glasgow RE. Applying the RE-AIM framework to assess the public health impact of policy change. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(2):105–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02872666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rounsaville B, Carroll K, Onken L. A Stage Model of Behavioral Therapies Research: Getting Started and Moving on From Stage 1. Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 2001;8:133–42. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nixon CA, Moore HJ, Douthwaite W, Gibson EL, Vogele C, Kreichauf S, et al. Identifying effective behavioural models and behaviour change strategies underpinning preschool- and school-based obesity prevention interventions aimed at 4-6-year-olds: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13(Suppl 1):106–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams CL, Carter BJ, Eng A. The “Know Your Body” program: a developmental approach to health education and disease prevention. Prev Med. 1980;9(3):371–83. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(80)90231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarzer R. In: Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors: Theoretical ap proaches and a new model. Schwarzer R, editor. Hemisphere; Washington, DC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(3):161–70. doi: 10.1037/a0024509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuz B, Sniehotta FF, Schwarzer R. Stage-specific effects of an action control intervention on dental flossing. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(3):332–41. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green L, Kreuter M. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 4th edition ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green L, Ottoson J. In: Public Health Education and Health Promotion. Novick L, Morrow C, Mays G, editors. Jones & Bartlett Publishers; Boston: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi P, Lipsey M, Freeman H. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach. 7th ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer M, Booker J. Eliciting and analyzing expert judgement: A practical guide. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; Philadelphia: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anders PL, Davis EL. Oral health of patients with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Spec Care Dentist. 2010;30(3):110–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2010.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanfield M, Scully C, Davison MF, Porter S. Oral healthcare of clients with learning disability: changes following relocation from hospital to community. Br Dent J. 2003;194(5):271–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809931. discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perlman S, Friedman C, Tesini D. Prevention and Treatment Considerations for People with Special Needs. Johnson & Johnson, Inc.; Skillman, NJ: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glassman P, Miller C. Dental disease prevention and people with special needs. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31(2):149–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vigild M, Brinck JJ, Christensen J. Oral health and treatment needs among patients in psychiatric institutions for the elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21(3):169–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tesini DA, Fenton SJ. Oral health needs of persons with physical or mental disabilities. Dent Clin North Am. 1994;38(3):483–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blisard KS, Martin C, Brown GW, Smialek JE, Davis LE, McFeeley PJ. Causes of death of patients in an institution for the developmentally disabled. J Forensic Sci. 1988;33(6):1457–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polednak AP. Respiratory disease mortality in an institutionalised mentally retarded population. J Ment Defic Res. 1975;19(3-4):165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1975.tb01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell SL, Boylan RJ, Kaslick RS, Scannapieco FA, Katz RV. Respiratory pathogen colonization of the dental plaque of institutionalized elders. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19(3):128–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1999.tb01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scannapieco FA, Stewart EM, Mylotte JM. Colonization of dental plaque by respiratory pathogens in medical intensive care patients. Crit Care Med. 1992;20(6):740–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Binkley CJ, Haugh GS, Kitchens DH, Wallace DL, Sessler DI. Oral microbial and respiratory status of persons with mental retardation/intellectual and developmental disability: an observational cohort study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(5):722–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.027. PMCID: 2763931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genuit T, Bochicchio G, Napolitano L, McCarter R, Roghman MC. Prophylactic Chlorhexidine Oral Rinse Decreases Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Surgical ICU Patients. Surgical Infections. 2001;2:5–17. doi: 10.1089/109629601750185316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoneyama T, Yoshida M, Ohrui T, Mukaiyama H, Okamoto H, Hoshiba K, et al. Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):430–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(Suppl):S8–17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kendall NP. Differences in dental health observed within a group of non-institutionalised mentally handicapped adults attending day centres. Community Dent Health. 1992;9(1):31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaw MJ, Shaw L. The effectiveness of differing dental health education programmes in improving the oral health of adults with mental handicaps attending Birmingham adult training centres. Community Dent Health. 1991;8(2):139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simons D, Baker P, Jones B, Kidd EA, Beighton D. An evaluation of an oral health training programme for carers of the elderly in residential homes. Br Dent J. 2000;188(4):206–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kakudate N, Morita M, Fukuhara S, Sugai M, Nagayama M, Kawanami M, et al. Application of self-efficacy theory in dental clinical practice. Oral Dis. 2010;16(8):747–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buglar ME, White KM, Robinson NG. The role of self-efficacy in dental patients' brushing and flossing: testing an extended Health Belief Model. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):269–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kakudate N, Morita M, Kawanami M. Oral health care-specific self-efficacy assessment predicts patient completion of periodontal treatment: a pilot cohort study. J Periodontol. 2008;79(6):1041–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Syrjala AM, Kneckt MC, Knuuttila ML. Dental self-efficacy as a determinant to oral health behaviour, oral hygiene and HbA1c level among diabetic patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26(9):616–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finlayson TL, Siefert K, Ismail AI, Sohn W. Maternal self-efficacy and 1-5-year-old children's brushing habits. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(4):272–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finlayson TL, Siefert K, Ismail AI, Delva J, Sohn W. Reliability and validity of brief measures of oral health-related knowledge, fatalism, and self-efficacy in mothers of African American children. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27(5):422–8. PMCID: 1388259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maserejian NN, Trachtenberg F, Link C, Tavares M. Underutilization of dental care when it is freely available: a prospective study of the New England Children's Amalgam Trial. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68(3):139–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly SE, Binkley CJ, Neace WP, Gale BS. Barriers to care-seeking for children's oral health among low-income caregivers. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(8):1345–51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harrison RL, Li J, Pearce K, Wyman T. The Community Dental Facilitator Project: reducing barriers to dental care. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63(2):126–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: the exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Resnick B, Simpson M. Restorative care nursing activities: pilot testing self-efficacy and outcome expectation measures. Geriatr Nurs. 2003;24(2):82–9. doi: 10.1067/mgn.2003.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Resnicow K, Cross D, Wynder E. The Know Your Body program: a review of evaluation studies. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1993;70(3):188–207. PMCID: 2359238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams CL, Arnold CB, Wynder EL. Primary prevention of chronic disease beginning in childhood. The “know your body” program: design of study. Prev Med. 1977;6(2):344–57. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(77)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lepore LM, Yoon RK, Chinn CH, Chussid S. Evaluation of behavior change goal-setting action plan on oral health activity and status. N Y State Dent J. 2011;77(6):43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chomitz VR, Collins J, Kim J, Kramer E, McGowan R. Promoting healthy weight among elementary school children via a health report card approach. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(8):765–72. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zemek RL, Bhogal SK, Ducharme FM. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining written action plans in children: what is the plan? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):157–63. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.UnitedNations . Capacity Development Practice Note. United Nations; New York, New York: 2006. [2013 August]. [updated 2006]; Available from: http://europeandcis.undp.org/uploads/public/File/Capacity_Development_Regional_Training/UNDP_Capacity_Development_Practice_Note_JUL Y_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frazao P, Marques D. Effectiveness of a community health worker program on oral health promotion. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43(3):463–71. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102009000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grant E, Carlson G, Cullen-Erickson M. Oral health for people with intellectual disability and high support needs: positive outcomes. Spec Care Dentist. 2004;24(2):70–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2004.tb01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hurling R, Claessen JP, Nicholson J, Schafer F, Tomlin CC, Lowe CF. Automated coaching to help parents increase their children's brushing frequency: an exploratory trial. Community Dent Health. 2013;30(2):88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson KW, Grube JW, Ogilvie KA, Collins D, Courser M, Dirks LG, et al. A community prevention model to prevent children from inhaling and ingesting harmful legal products. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(1):113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.08.001. PMCID: 3210444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson KW, Ogilvie KA, Collins DA, Shamblen SR, Dirks LG, Ringwalt CL, et al. Studying implementation quality of a school-based prevention curriculum in frontier Alaska: application of video-recorded observations and expert panel judgment. Prev Sci. 2010;11(3):275–86. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0174-5. PMCID: 3569516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meyer MA, Booker JM. Eliciting and analyzing expert judgment: A practical guide. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; Philadelphia: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson K, Shamblen SR, Ogilvie K, Collins D, Saylor B. Preventing youth's use of inhalants and other harmful legal products in frontier Alaskan communities: A randomized trial. Prevention Science. 2009;10(4):298–312. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0132-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnson K. Structural equation modeling in practice: Testing a theory for research use. Journal of Social Service Research. 1999;24(3/4):131–71. [Google Scholar]