Abstract

PURPOSE

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) with autologous tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) is a therapy for metastatic melanoma with response rates up to 50%. However, the generation of the TIL transfer product is challenging, requiring pooled allogeneic normal donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) used in vitro as “feeders” to support a rapid expansion protocol (REP). Here, we optimized a platform to propagate TIL to a clinical scale using K562-cells genetically modified to express costimulatory molecules such as CD86, CD137-ligand and membrane-bound IL-15 to function as artificial antigen-presenting cell (aAPC) as an alternative to using PBMC feeders.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

We used aAPC or γ-irradiated PBMC feeders to propagate TIL and measured rates of expansion. The activation and differentiation state was evaluated by flow cytometry and differential gene expression analyses. Clonal diversity was assessed based on pattern of T-cell receptor (TCR) usage. T-cell effector function was measured by evaluation of cytotoxic granule content and killing of target cells.

RESULTS

The aAPC propagated TIL at numbers equivalent to that found with PBMC feeders, while increasing the frequency of CD8+ T-cell expansion with a comparable effector-memory phenotype. mRNA profiling revealed an up-regulation of genes in the Wnt and stem-cell pathways with the aAPC. The aAPC platform did not skew clonal diversity and CD8+ T cells showed comparable anti-tumor function as those expanded with PBMC feeders.

CONCLUSIONS

TIL can be rapidly expanded with aAPC to clinical scale generating T cells with similar phenotypic and effector profiles as with PBMC feeders. These data support the clinical-application of aAPC to manufacture TIL for the treatment of melanoma.

Keywords: Adoptive T-cell therapy, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, melanoma, artificial antigen-presenting cells, K562, co-stimulation

INTRODUCTION

Adoptive T-cell therapy infusing propagated autologous tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) ex vivo has been shown in multiple Phase II clinical trials to be an effective investigational therapy for metastatic melanoma with sustained clinical response rates of approximately 50% according to RECIST criteria (1–3). These anti-tumor effects are attributed to the infusion of T cells harvested from a tumor site that maintain a broad specificity during the tissue culture. Notably, the infusion of TIL has emerged to be a salvage therapy for some patients who progressed after multiple lines of prior therapy (including checkpoint blockade). The typical clinical protocol includes a lymphodepleting preconditioning regimen using cyclophosphamide and fludarabine followed by co-infusion of TIL and IL-2 (2–4). Correlative biomarker studies on patients responding to this adoptive immunotherapy revealed attributes of the infusion product associated with therapeutic success. For example, an increased proportion of CD8+ T cells and CD8+ T cells expressing the B- and T- lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) in the propagated TIL infusion product is associated with favorable outcomes (3, 5, 6).

One obstacle limiting the distribution of TIL-based immunotherapy is the technical challenges associated with the manufacture of the autologous TIL-derived product. Currently, TIL expansion requires a two week rapid-expansion protocol (REP) using CD3 cross-linking and IL-2 after an initial expansion of TIL from small pieces of tumor (tumor fragments) with IL-2 alone (7, 8). This generates a final infusion product composed of 20–150 billion T cells (7, 8). A key component in the REP besides anti-CD3 and IL-2 is the presence of an excess of irradiated allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy donors added as “feeder cells” (7, 9). These feeders are needed to support TIL activation and propagation early during the REP. However, the procurement of large numbers of feeder cells (up to 1010 per patient treated) is difficult and expensive. The practicality of using these feeders is further compounded by the requirement to pool PBMC from multiple donors (4–6 donors at a time) to ensure optimal activity; which introduces lot-to-lot heterogeneity and variability in activation of TIL. This problem is one of the key issues that has hindered the out-scaling of TIL manufacturing and therapy.

A common bank of well defined, renewable, and designed feeders will remedy these issues associated with PBMC-derived feeders. Artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPC) have been developed from K562 cells (10) and applied by our group for clinical expansion of genetically modified T cells from peripheral blood (11–13). K562-derived aAPC have been shown to expand bulk or antigen-specific T cells to large numbers while preserving clonal diversity (11, 14). K562 cells were genetically modified and cloned (designated clone 4) to homogeneously express desired T-cell co-stimulatory molecules CD86, CD137-ligand (4-1BBL), high affinity Fc receptor (CD64) to allow antibody coating and membrane-bound variant of IL-15 (mIL15, co-expressed with EGFP) (15). K562-based aAPC would be an appealing “off-the-shelf” feeder cell to expand TIL for human application. However, it is unclear whether aAPC will support a reproducible and scalable system for activation and propagation of human TIL and expansion yields comparable or improved from the traditional REP needed for clinical application.

In this study, we investigated an alternative to PBMC feeders REP based on activating and propagating melanoma TIL using aAPC in the traditional flask system as well as in a new “G-REX” culture flask system (16). We found that the aAPC supports the rapid expansion of TIL to a similar extent as PBMC feeders with a comparable effector-memory phenotype, making aAPC suitable for GMP grade melanoma TIL REP. We observed that the aAPC expansion platform was also able to favor the expansion of CD8+ TIL which we have found to be critical in mediating tumor regression in treated patients (3). Our results show that aAPC may be used in lieu of PBMC to support the production of T cells from TIL for human application and thus, we plan on retiring the traditional PBMC feeders from our approach to manufacturing clinical-grade T cells for melanoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Initial propagation of TIL from human melanoma tumors

TIL used in this study were isolated from tumor samples obtained from melanoma patients with stages IIIc and IV disease undergoing surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) according to Institutional Review Board-approved protocols and patient consent (LAB06-0755 and LAB06-0757). The initial TIL expansion was undertaken in 24-well plates from either from small 3–5 mm2 tumor fragments or after enzymatic digestion followed by centrifugation over a step gradient of 75% and 100% Ficoll, with the TIL collected from above the 100% Ficoll layer (3, 17). In both cases, the T cells were propagated for 3 to 5 weeks with 6,000 IU/mL human recombinant IL-2 (Prometheus; San Diego, CA) in RPMI 1640 with Glutamax supplemented with 2 mM L-Glutamine, 1 mM Pyruvate, 1x of HEPES, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1X Pen-Strep (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 10% heat-inactivated human AB Serum (Sigma-Aldrich). Autologous tumor lines were established from enzymatically-digested tumors by collecting the cells at the 75% Ficoll layer and used as targets.

Rapid expansion of TIL (REP)

Cultured TIL were propagated by REP with anti-CD3 (OKT3, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) using pooled allogeneic irradiated PBMC feeder cells (ratio of 1 TIL to 200 feeders), which is identical to the protocol currently used for Phase II clinical trials carried out at MDACC (3). For TIL propagation carried in the G-REX 100M flask (Wilson Wolf Manufacturing, New Brighton, MN); 5×106 TIL were seeded per G-REX flask on day 0 and the expansion was completed using same reagents, feeding schedule and cell ratios as the current protocol performed in traditional flask.

Rapid expansion of TIL by aAPC

Cultured TIL were co-cultured with irradiated aAPC (ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1:100 (TIL:aAPC)) that were derived from K562 cells genetically modified to co-express CD19, CD64, CD86, CD137L and mIL15 and cloned to obtain homogenous expression (18). Prior to starting the REP, the K562 clone 4 aAPC were irradiated at 150 Gy and pre-loaded with anti-CD3. Briefly, cells were incubated in X-VIVO 15 (LONZA, Walkersville, MD) media containing 0.2% of Acetylcysteine (APP Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL) (at a concentration of 1 million per mL overnight followed by an incubation with OKT3 (0.1 to 1ug/mL) at 4°C for 30 min while rotating. Clone 4 aAPC were then washed and frozen for subsequent usage. The TIL expansion in the G-REX 100M using the aAPC was performed as described above.

Flow cytometry

Monitoring of clone 4 was done by staining with anti-CD64-PE, CD137L-PE and CD86-APC (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and OKT3 loading was evaluated by staining with a PE-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunology Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA). T cells were stained with anti-CD3-FITC (or PerCP-Cy5.5), CD8-PB (or APC-H7), CD16-PE, CD56-PE-Cy7 (or PE), CD27-APC, CD28-PE-Cy7, CD127-PE, BTLA-PE (clone J168), CD45RA-FITC (or V450), CD57-FITC (BD Bioscience), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5, TIM3-APC (clone F38-2E2) (eBioscience), PD1-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone EH12.2H7) and CCR7-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Cells were stained in 100 μL FACS buffer containing AQUA live/dead dye (Invitrogen) on ice for 30 minutes. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and subsequently stained for granzyme B-PE, perforin-FITC (eBioscience), and in some cases also with cleaved caspase-3-PE (BD Biosciences). Data acquired using a FACScanto II cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo v 7.6.5 (Treestar) with different subsets defined using size, viability, and “fluorescence minus one” (FMO) controls.

Direct TCR expression assay (DTEA)

Total RNA was isolated from post-REP TIL expanded with either feeders or aAPC using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), and quantified using a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, St-Louis, MO). DTEA to measure the abundance of 45 Vα and 46 Vβ TCR chains was performed using the nCounter™ (model No. NCT-SYST-120) assay system (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA) as described (19).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA (300 ng) from T cells that completed propagation by REP or aAPC was amplified using Ambion WT expression kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA and a second strand cDNA was generated, which was then used as a template for in vitro transcription for cRNA synthesis. Following purification, the cRNA was converted into cDNA and excess RNA was removed by RNase H treatment. With the use of restriction digestion, cDNA was fragmented and labeled on the terminal end with the GeneChip WT Terminal Label kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The samples were hybridized to Human Gene ST 1.0 Arrays (Affymetrix) in a GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640 for >16 hours, at 45°C, 60 rpm, stained on a GeneChip Fluidics Station 450, and scanned by GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix). Following quality control assessment, unprocessed data were engendered with Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console, and analyzed using Partek Genomic Suite 6.6 software after background subtraction and RMA normalization. Differentially expressed genes were defined by two way ANOVA with p value <0.005. Genes were further analyzed for functional involvement and enrichment using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (QIAGEN, Redwood City, CA).

T-cell mediated killing

Killing of HLA-A- matched melanoma tumor cells (target cells) by specific activated/propagated T-cells was visualized flow cytometry to measure the level of activated caspase-3 in target cells (20). To test the class I-dependency of killing, target cells were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C with 80 μg/mL of either MHC class I blocking antibody W6/32 or the IgG2a-matching isotype control (eBioscience).

IFN-γ ELISA assay

Anti-tumor reactivity of post-REP TIL was also tested by measuring IFN-γ secretion using ELISA on supernatants of co-cultures of 5×104 TIL with 5×104 (triplicates) tumor cells from autologous or HLA-A-match melanoma lines (3). Assays were performed in 96-well plates and supernatants were collected after 16 h and stored at −80°C until analysis. MHC class I blocking antibody W6/32 or the mouse IgG2a matching isotype was also used as control in these assays, as described above. TIL treated with PMA (50 pg/mL) and Ionomycin (2 μg/mL) were also included as a positive control. ELISA was performed done using ELISA kits (Pierce, St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

Rapid expansion of melanoma TIL using aAPC leads to similar rates of TIL expansion as PBMC-feeders and favors CD8+ T-cell growth

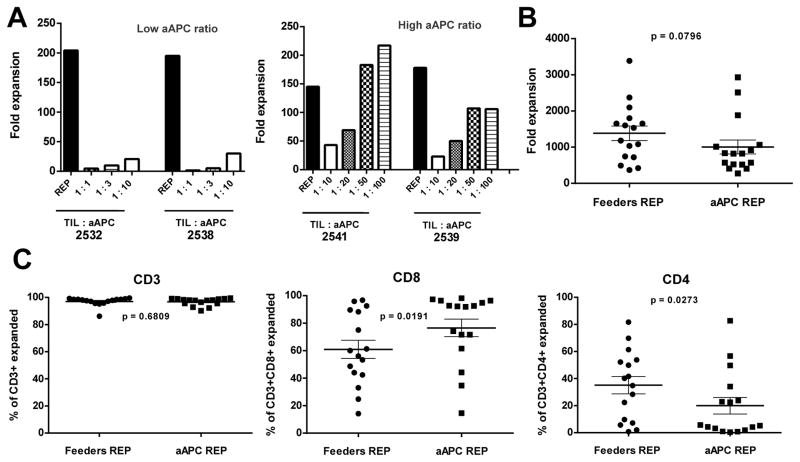

The current REP used for the clinical manufacturing of melanoma TIL infusion products uses pooled irradiated PBMC as feeders and usually achieves TIL expansion in the range of 500 to 2,000-fold over 14 days to generate infusion products used in TIL clinical trials. We first assessed whether K562-aAPC (clone 4) loaded with OKT3 could achieve comparable levels of expansion from TIL, as the traditional PBMC-feeders, but also preserve the CD8+ T cells component that has been shown to correlate with clinical response. Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data on-line) shows OKT3 loading as well as the expression levels of CD64, CD86, and 4-1BBL stably expressed in the clone 4 aAPC that were used in all the experiments. We first evaluated different ratios of aAPC added to TIL compared to the PBMC feeders REP to identify the best TIL:aAPC ratio yielding the highest and most consistent expansion. The most rapid phase of TIL cell division (population doublings) occurs during the first 7 days of the REP, reasoning that the initial 7-day period was enough to judge the activity of the aAPC. As shown in Fig. 1A (left graph), lower ratios of TIL to aAPC (1:1 to 1:10) could not expand TIL to a similar level as the traditional REP with feeders (1:200 TIL:feeders). However, increased ratios of the aAPC increased the fold expansion, with a 1:50 ratio supporting near maximal or maximal TIL expansion (Fig. 1A, right graph). Based on this data, we chose the 1:50 TIL:aAPC ratio for subsequent experiments and further development of this system.

Figure 1.

Rapid expansion of melanoma TIL using aAPC. A) Melanoma TIL cultured in high doses of IL-2 (6000 IU/mL) for three to five weeks were rapidly expanded using different TIL:aAPC ratios [low (1:1, 1:3, 1:10) and high (1:10, 1:20, 1:50 and 1:100)] and 30 ng/mL of αCD3 mAb (OKT3) with IL-2. Fold expansion of bulk TIL was evaluated on day 7 of the REP. B) Graph showing cumulative data of fold expansion of bulk TIL lines C) Percentage of CD3+ TIL post-REP (left graph) obtained after 14 days of expansion. Middle and right graph show post-REP frequency of respectively CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD4+ TIL. For each TIL line, REP were setup simultaneously using PBMC-feeders (1:200) and aAPC (1:50) as an expansion platform for direct comparison. Statistics were determined using paired t test and a “p” value <0.05 was considered significant.

Comparison of T cells propagated by PBMC feeders REP and aAPC REP

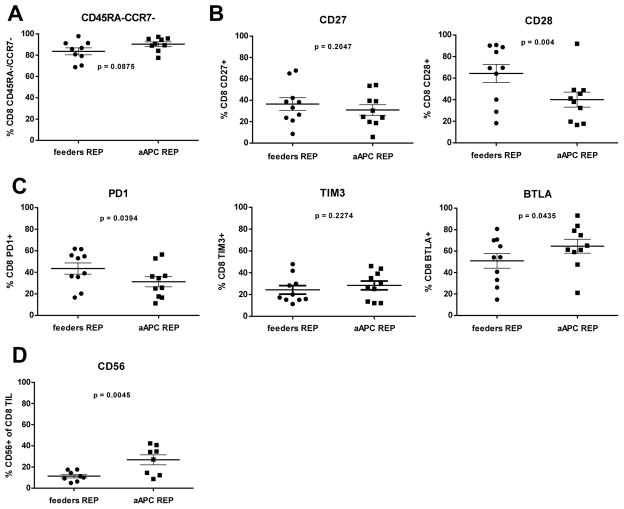

The 1:50 TIL:aAPC ratio was used to activate and rapidly expand TIL for 14 days for a larger number of patient samples (n= 16). As shown in Figure 1B, there was no statistical difference (p> 0.05) in the fold expansion of TIL co-cultured with aAPC versus propagated with PBMC feeders. After co-culture the final TIL products were almost exclusively CD3+ cells (Fig. 1C), but the aAPC REP yielded an increased percentage of CD3+CD8+ T cells with a concomitant decreased percentage of CD3+CD4+ T cells compared to traditional REP. The propagated products contained only a small frequency of NK cells (<5%) as marked by CD56+ or CD56+CD16+ cells (data not shown). The increased CD8+ T-cell yield is desirable as clinical data indicates that an increased frequency of CD8+ TIL infused was associated with tumor regression (3). We performed additional multicolor flow cytometry analysis on post-REP melanoma TIL from a number of patients expanded with both platforms for 14 days. Panels were established to study the expression of differentiation, activation, and co-inhibitory markers on T cells based on expression of CD8, CD56, CD45RA, CD127, CD28, CD27, CCR7, BTLA, TIM3 and PD1. We focused on CD8+ T cells, given its association with clinical response in our TIL clinical trial and also because of the presence of 4-BBL on the aAPC which activates costimulation through 4-1BB mainly expressed on activated CD8+ T cells. Co-staining for CD45RA and CCR7 revealed that the majority of expanded CD8+ cells with either protocol were CD45RA−CCR7− as well as CD127−, consistent with an effector-memory phenotype (Fig. 2A and data not shown) (21). The expression of CD27 and CD28 are other markers used to identify effector-memory cells. Although we did not find any differences in the frequency of CD27+ cells emerging from the two expansion approaches, we observed a decreased frequency of CD28+ T cells co-cultured with aAPC (Fig. 2B; p= 0.004). This prompted us to examine the expression of inhibitory molecules such as TIM3, PD1, and BTLA. There was no significant difference in the expression of TIM3 on T cells propagated using the two protocols, however, PD1 was expressed on a lower percentage of CD8+ T cells expanded with aAPC than with PBMC feeders (Fig. 2C; p= 0.0394). We also observed higher percentage of CD8+ T cells expressing BTLA after aAPC REP compared with traditional REP (Fig. 2D; p= 0.0435). This was of great interest given our previous observation linking of BTLA expression on CD8+ TIL with clinical response following TIL infusion (3). To further evaluate the activation status, we assessed expression of CD56 on CD8+ TIL rapidly expanded with aAPC compared with PBMC feeders (Fig. 2D; p= 0.0045) (22, 23). In summary, these flow cytometry data indicate that CD8+ T cells propagated with the aAPC exhibit an effector-memory phenotype similar to the one generated with the feeders REP.

Figure 2.

Intensive phenotyping by flow cytometry shows similarity in differentiation markers on post-REP CD8+ TIL for both conditions with the exception of CD28, BTLA and CD56. Post-REP TIL were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, anti-CD4, anti-CD16, anti-CD56, anti-CD127, anti-CD28, anti-CD27, anti-CCR7, anti-BTLA, anti-TIM3 and anti-PD1. Results are showed after excluding dead cells by using Aqua®live/dead (AQUA) staining. Graphs show ten TIL lines, with only the most predominant makers presented. (A) Frequency of CCR7− CD45RA− in the CD8+ T-cell population after expansion. (B) Analysis of CD27 and CD28 expression in the CD8+ T-cell population. (C) Frequency of PD1 (left), TIM3 (middle) and BTLA (right) positive cells in the CD8 population. (D) Percentage of CD56+ cells expended amongst the post-REP CD8+ TIL. Gating was performed with the use of “fluorescence minus one (FMO)” controls. Statistics were determined using paired t test and a “p” value <0.05 was considered significant.

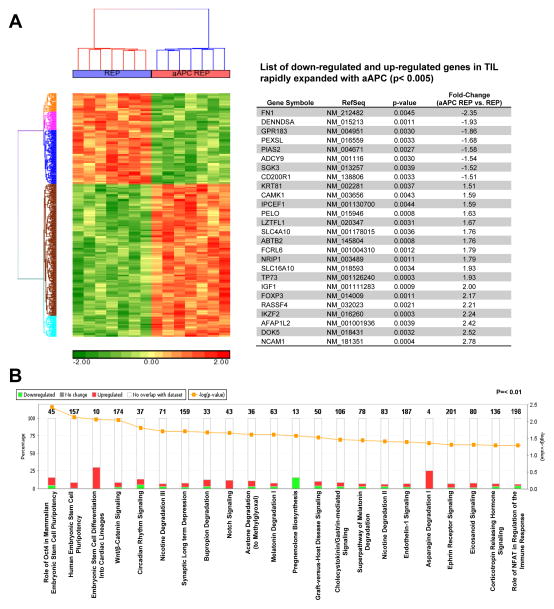

Gene expression reveals a shared effector and stem-like cell profile in TIL rapidly expanded with aAPC

We profiled and compared gene expression using Affymetrix Human Gene ST 1.0 ST gene chip arrays (33,297 human transcripts) of 7 post-REP melanoma TIL lines rapidly expanded simultaneously with either the aAPC or PBMC feeders. The heat map presented in Figure 3A (left) shows the clustering of post-REP TIL depending on their expansion platform after removing the noise introduced by heterogeneity amongst patients. This source of variation remained lower than our point of comparison which was the type of expansion platform (data not shown), validating the differentiation analysis. Using this approach, we found 26 highly significant genes (p< 0.005, two-way ANOVA based on cell line and expansion method) differentially down-regulated or up-regulated in the aAPC REP TIL (Fig. 3A, table). A more complete list of differentially-expressed genes with a p< 0.01 cut-off for statistical significance is also shown in Table S1. Top differentially expressed genes in Figure 3A (table) included CD56 (NCAM1) which was the highest up-regulated gene in the aAPC REP TIL, with a fold change of 2.78 (p= 0.0004). This result correlates with the protein expression previously observed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2D). The transcription factor FOXP3 was also up-regulated 2.17-fold in TIL expanded with the aAPC platform. FOXP3 is usually associated with regulatory T cells (Tregs) but no other Treg-associated genes were found to be up-regulated in the aAPC REP TIL in this assay. However, it must be noted that FOXP3 can also be expressed by recently activated conventional (non-Treg) T cells and IFN-γ producing non-regulatory T cells (24, 25). The most highly down-modulated gene was fibronectin-1 (FN1). Fibronectin, a multifunctional glycoprotein, is a major component of lymph nodes and participates in the CCR7/CCL21 mediated T-cell migration into the lymph node (26, 27). Although CD28 was not among the altered genes found after applying a more stringent p-value cut-off (Fig. 3A, table) it was significantly down-modulated in the aAPC REP TIL by −2.24-fold, (p= 0.0066) (Table S1). Similarly, the BTLA gene was up-regulated +1.33 (p= 0.0088) (Table S1). Both these results are in agreement with the flow cytometry data (Fig. 2C).

Figure 3.

TIL rapidly expanded using the aAPC platform demonstrated a dual gene signature with attributes of effector and stem cells. (A) Enrichment analysis of a global set of genes from post-REP TIL expanded with feeders or aAPC. The left shows a heat map cluster after removal of the cell line factor. On the right, a table presenting the top 26 genes, ranked by fold-expression changes with a “p” value <0.005, that are showing a differentiation of expression in aAPC post-REP TIL. A Two way ANOVA was performed using two parameters: cell line and expansion method. A comprehensive list of genes ranked by enrichment scores are shown in Supplemental Table 1. (B) Graph showing the percentage (and the number in bold) of gene up regulated (red columns) and down regulated (green columns) in the different canonical pathways. The dark yellow line (log) shows the intensity of change in the gene expression. Analysis was performed using “Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)”, p <0.01.

With the use of the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), we further analyzed the microarray data by undertaking a pathway and network analysis (Fig. 3B). The pathways altered in the aAPC TIL with the lowest p-values were involved in stem cell or stem cell-associated pathways such as the Wnt pathway (see first 4 significant pathways on the left side of Fig. 3B). For the most part, these canonical pathways are not traditionally associated with lymphocyte development, but their involvement in pluripotency and differentiation of stem cells from non-lymphoid origins is intriguing.

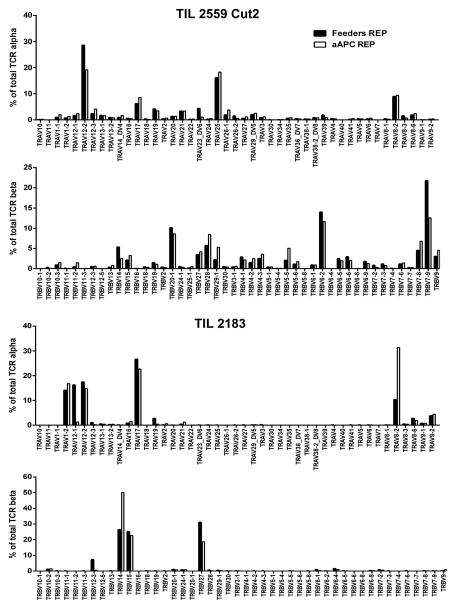

Diversity of TCR usage was preserved in TIL propagated with the aAPC platform

TIL contain a diverse repertoire of T cells and the maintenance of this diversity as well as their ability to recognize multiple tumor-associated antigens is considered an advantage of TIL versus other forms of T-cell therapy (28, 29). Therefore, we compared the ability of the two approaches at rapidly expanding TIL on the overall TCR gene diversity of the post-REP products. We assessed the diversity and abundance of TCR expression by direct TCR gene expression analysis (DTEA) assay, a non-enzymatic assay based on bar-coded probes (19). DTEA revealed that the abundance of the of 45 Vα and 46 Vβ TCR chains was similar in both approaches (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

aAPC REP does not favor or disfavor expansion of predominant melanoma TIL clonotypes. Measurement of the expression of major TCR α and β chain gene usage found after rapid expansion (REP) with either aAPC REP or PBMC feeders using the NanoString nCounter® technology. This assay directly digitally reads out the level of expression of 45 possible Vα and all known 46 Vβ genes in RNA isolates using bar-coded probes. Two examples representative of six TIL lines from six melanoma patients.

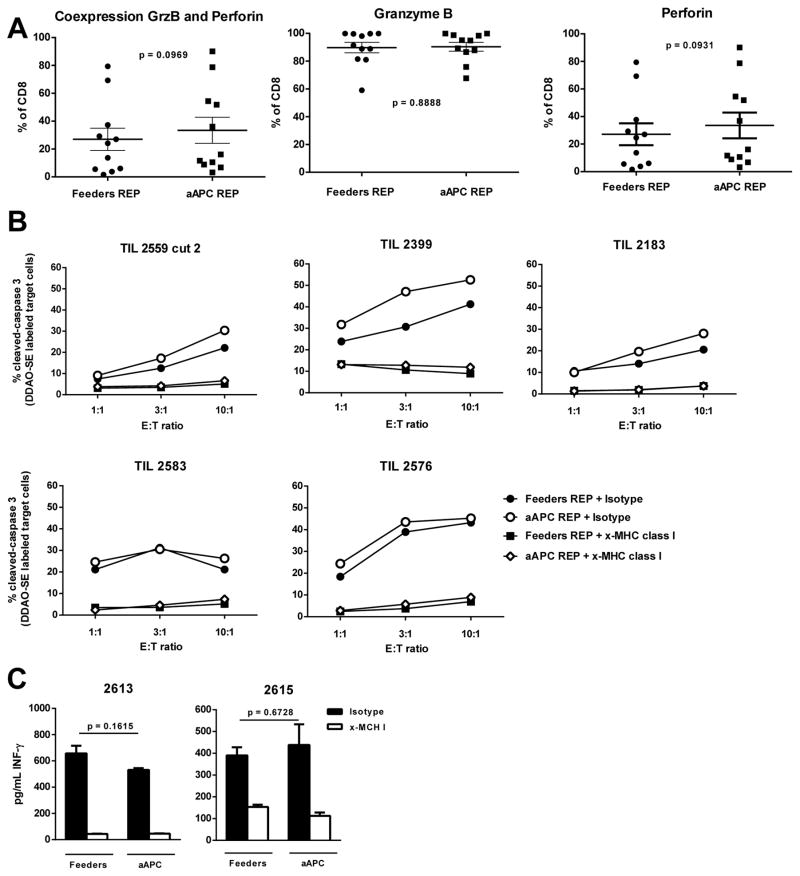

Post-REP TIL expanded with aAPC display comparable anti-tumor CTL activity as TIL expanded with the conventional feeders REP

We first assessed the cytolytic potential of both post-REP products by flow cytometry staining for intracellular cytotoxic granule proteins granzyme B and perforin. As shown in Fig. 5A, no difference was found when TIL lines where rapidly expanded with either method. In addition, we measured tumor-specific CTL activity in post-REP TIL using a flow cytometry-based CTL assay staining for the extent of caspase 3 cleavage in melanoma cell line targets. In both cases, similar levels HLA-restricted tumor cell killing were observed after the REP (Fig. 5B). Addition of anti-HLA-class I blocking antibodies to these assay inhibited caspase 3 cleavage showing the specificity of the TIL in each case. We also measured IFN-γ release in response to co-incubation of post-REP TIL with HLA matched melanoma cells and found similar IFN-γ secretion capacities of the post-REP TIL in both cases (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Melanoma CD8+ TIL rapidly expanded with the aAPC platform demonstrated an antitumor potential equivalent than TIL expanded with PBMC-feeders. (A) On day 14 of the REP, cells were harvested, permeabilized and stained for surface CD8, AQUA and intracellular Granzyme B and Perforin. (B) Post-REP TIL were cocultured with DDAO-SE labeled autologous or HLA-A matched tumor cell line for 3 hours. Tumor cells were pre-incubated with 80 μg/mL of blocking antibodies specific for MHC-I (clone W6/32) as a test for class I-dependency of killing or the corresponding isotype (IgG2a). Target-to-Effector (T:E) ratios of 1:1, 1:3 and 1:10 were used. After 3 hours, cells were permeabilized and stained for active caspase-3 by flow cytometry. The graphs indicate percent expression of active caspase-3 in the tumor cells. The MHC-1 blocking control is shown on the bottom row. (C) Post-REP TIL and tumor cells were cocultured with or without MHC-I blocking antibody for 16 hours at a ratio of 1:1. Supernatant was collected and an IFN-γ ELISA assay was performed in triplicates and the mean ± SE is shown for each. Statistics were determined using paired t test and a “p” value <0.05 was considered significant.

Application of aAPC for rapid expansion of melanoma TIL using the G-REX system

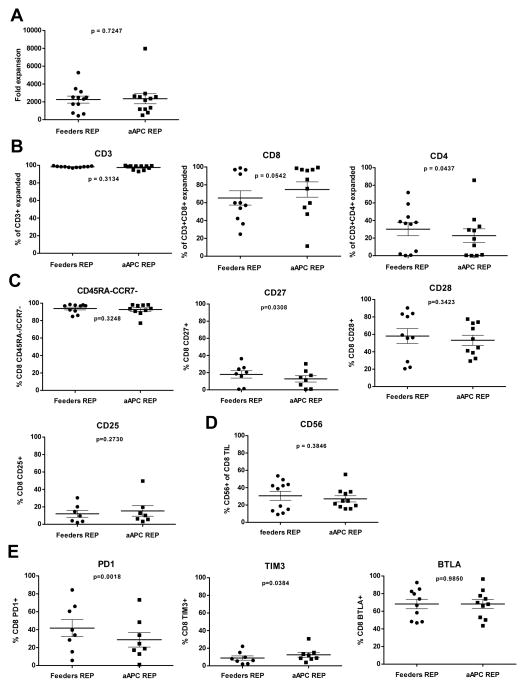

Currently, our group at MD Anderson Cancer Center has adopted the use of the G-REX culture flask system (Wilson-Wolf, Minneapolis, MN) for the clinical-grade REP of melanoma TIL for patient therapy. This G-REX system uses flasks that have a gas permeable membrane at the bottom of the flask where cells sit during culture allowing gas exchange directly through this membrane rather than needing to diffuse through the culture medium on top of the cells (16, 30). We have adopted the GREX 100M flask system having a 100 cm2 gas permeable membrane for the clinical-grade rapid expansion of melanoma TIL in our Phase II clinical trials using the PBMC feeder system. Here, we wanted to also test how the aAPC support the rapid expansion of melanoma TIL using this new G-REX system using the same aAPC to TIL (50:1) and PBMC feeder to TIL (200:1) ratios as before. We compared the propagation of 12 different melanoma pre-REP TIL lines and did post-REP phenotyping by flow cytometry using the same antibody panels used before. As shown in Fig. 6A, no differences in fold expansion was observed when TIL were rapidly expanded with the aAPC or with the PBMC feeders in the G-REX 100M flask. We observed a high fold expansion rate with the use of the G-REX 100M for both REP conditions (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Melanoma TIL rapidly expanded with the aAPC in the G-REX flask have a comparable phenotype then when expanded with the PBMC-feeders. Flow cytometry on post-REP CD8+ TIL for both conditions shows similarity in differentiation, activation and inhibition molecules. Post-REP TIL were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, anti-CD4, anti-CD16, anti-CD56, anti-CD127, anti-CD28, anti-CD27, anti-CCR7, anti-CD25, anti-BTLA, anti-TIM3 and anti-PD1. Results are showed after excluding dead cells by using Aqua®live/dead (AQUA) staining. Graphs show ten TIL lines expanded in the G-REX flask. (A) Graph showing cumulative data of fold expansion of bulk TIL lines. (B) Percentage of CD3+ TIL post-REP (left graph) obtained after 14 days of expansion. Middle and right graph show post-REP frequency of respectively CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD4+ TIL. Frequency of CCR7− CD45RA− in the CD8+ T-cell population after expansion (C) Frequency of CCR7− CD45RA− (upper left graph), CD27 (middle), CD28 (right) and CD25 (lower left graph) in the CD8+ T-cell population after expansion. Frequency of PD-1, TIM3 and BTLA positive cells in the CD8 population. (D) Percentage of CD56+ cells expended amongst the post-REP CD8+ TIL. (E) Frequency of PD-1 (left), TIM3 (middle) and BTLA (right) positive cells in the CD8 population. Gating was performed with the use of “fluorescence minus one (FMO)” controls. Statistics were determined using paired t test and a “p” value <0.05 was considered significant.

As shown in Figure 6B (left graph), the post-REP product from the G-REX system was mostly constituted CD3+ cells for both conditions. Similar frequencies of CD8+ TIL were obtained, except that the aAPC REP condition tended to yield a higher CD8+ cell frequency, although this did not reach statistically significance (p= 0.0542; Fig. 6B). CD4+ T-cell frequency was however significantly lower in the aAPC G-REX 100M REP cultures (Fig. 6B, far right panel).

No major differences in the CD45RA−CCR7− subset, CD25 and CD27 expression were found (Fig 6C, middle graph). In addition CD28 expression showed no significant difference between aAPC and PBMC feeders REP in the G-REX 100M flask (Fig. 6C, right graph). The frequency of CD3+CD8+CD56+ cells was also similar between the aAPC and PBMC feeders REP (Fig. 6D). The frequency of cells with a late stage CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell phenotype based on expression of markers such as CD56 and CD57 (CD28−CD56+ or CD28−CD57+) was low but favored the aAPC protocol regarding a lower CD28−CD57+ population, suggesting that most of the expanded CD8+ cells were activated effector-memory cells (Supplementary Fig. 2).

As before, we also measured the expression of PD-1, TIM-3 and BTLA on the post-REP cells. No significant differences were found in the frequencies of CD8+BTLA+ cells with aAPC versus PBMC feeders in the GREX system (Fig. 6E). However, the frequency of PD-1+ CD8+ cells was significantly lower when TIL were rapidly expanded with the aAPC in the G-REX flask and the frequency of TIM3-expressing cells was slightly higher under the aAPC condition (Fig. 6E, left panel), although lower than what we observed in the regular flask system before.

DISCUSSION

Adoptive cell therapy of autologous TIL has been one of the most effective treatments for refractory metastatic melanoma with clinical response rates near 50% (1–3). However, only a few cancer centers are currently capable of performing this therapy due to the intricate culture steps making its implementation in a broader number of institutions challenging. One of the main obstacles is the technical complexity of expanding TIL to the large numbers needed to achieve clinical effectiveness (20–150 billion). The need to procure large numbers of donor-derived pooled PBMC cell products as “feeders” to provide cell support for the TIL REP represents both a technical and financial problem. The rapid expansion usually requires a 200:1 PBMC feeders to TIL ratio to facilitate optimal TIL growth, especially of CD8+ T cells which are critical for mediating anti-tumor activity. In addition, procurement of PBMC feeder products introduces logistics issues with the collection of donor apheresis products, batch-to-batch variability, and increased costs. The results presented here indicate that the use of a genetically modified antigen-presenting cell line based on the K562 erythroleukemia cell line can be a practical and effective alternative to PBMC feeders for TIL rapid expansion. Using the K562 clone 4, we developed an optimal and clinically-translatable approach that can rapidly expand melanoma TIL at comparable rates of expansion as the PBMC feeders REP generating a final product that is phenotypically and functionally similar.

We tested different aAPC:TIL ratios and found that an aAPC:TIL ratio of 50:1 was ideal in that it facilitated optimal rates of expansion comparable to the PBMC feeders REP while still maintaining an aAPC:TIL ratio that was well below the 200:1 PBMC feeder:TIL ratio used in the conventional REP. We were able to induce even higher rates of expansion (over 2000-fold) when the aAPC were used in the G-REX flask system without having to restimulate the TIL during the expansion phase. This was achieved with only one initial stimulation using the aAPC compared to previous studies using a lower 2:1 aAPC:TIL ratio in which an additional round of stimulation was needed to increase the fold-expansion to levels achieved here (31). We also observed that our aAPC favored the proliferation of the CD8+ TIL over CD4+ cells. This higher percentage of CD8+ T cells in the final REP product may be attributed to enhanced 4-1BB costimulation provided to the activated TIL by the 4-1BBL on the surface of aAPC which was previously described to preferentially expand CD8+ T cells (32). In fact, 4-1BBL was reported to be essential to expand TIL directly from single cell suspension of tumor digests using K562-aAPC and IL-2, with favored expansion towards CD8+ T cells but also NK cells given the absence of CD3 stimulation in this study (33). Moreover, our group previously demonstrated that engagement of 4-1BB during the initial phase of the REP favors expansion of CD8+ T cells amongst TIL (34).

Given our previous report correlating a higher frequency and number of infused CD8+ T cells with clinical response in the 31 first patients of our TIL therapy trial at MD Anderson Cancer Center (3), we decided to further characterize the post-REP CD8+ T cells by measuring the expression of a number of lineage-specific markers, as well as activation, differentiation and negative costimulatory molecules and differential gene expression analysis using gene chips on the final TIL products. One of the major differences we observed was a higher percentage of CD8+ TIL positive for the expression of NCAM (CD56) in the aAPC REP compared to the PBMC feeders REP. Expression of CD56 by CD8+ T-cell is usually associated with a highly cytotoxic profile and increased effector cell differentiation (22, 23). It has been previously reported that stimulation with 4-1BBL can enhance the killing potential of CD3+CD56+ cells and also of CD8+ T cells, but to our knowledge, expression of CD56 on CD8+ T cells induced by 4-1BB stimulation was not investigated (35, 36). The increased frequency of CD8+CD56+ cells in the post-REP product generated with the aAPC in regular T-25 flasks could also indicate a more differentiated effector-memory phenotype since the frequency of CD8+CD28+ cells also tended to be lower. CD56 expression was also found on terminally-differentiated T-cells but these cells were also expressing CD45RA and high levels of PD-1 which is not the case in our study (37, 38). It is also possible that decreased CD28 is reversible and due to the high CD86 expression on the aAPC that may down-modulate, but not permanently eliminate CD28 expression. Previous published data from patients treated with tumor-specific T-cells has also found that activated T-cells can the re-express CD28 and CD27 in vivo after adoptive transfer (39). However, the decreased CD28 expression in the T-flask system with the aAPC was not observed with when TIL were rapidly expanded using the G-REX flasks which we are now using for clinical-grade TIL expansion in our adoptive cell therapy trials. Thus, the data from our G-REX flask system indicated that CD28 expression can be preserved with the aAPC REP.

Interestingly, the difference with the CD56 expression between the two expansion platforms was also lost in the G-REX flask and similar frequencies of CD45RA−CCR7− cells were observed, independently of the device that was used for the REP. Thus, the use of the G-REX flask to rapidly expand TIL seems to have a bigger impact on the phenotype of the expanded TIL when using PBMC feeders in the REP whereas the phenotype of the TIL seems to be more stable with the aAPC REP independently of the type of flask. It is possible that the improved gas exchange in the G-REX flasks (increased O2 availability and faster CO2 diffusion) due to the nature of this culture system versus the tradition T-flask may alter the metabolism of the cells.

Our microarray gene expression analysis suggests that the aAPC may not indeed lead to increased T-cell differentiation. Pathway analysis conducted on the 7 TIL lines rapidly expanded with either the PBMC feeders or the aAPC platform after microarray analysis demonstrated up-regulation of genes belonging to canonical pathways such as the Wnt pathway and other stem cell pathways. Recently, Lee et al., reported that induction of 4-1BB signaling leads indirectly to activation of the TCF-1/β-catenin pathway in T cells, which involved activation of the Wnt signaling pathway downstream of 4-1BB (40). This observation was attributed to a delayed effect of 4-1BB signaling and was visible 1 to 2 days following 4-1BB ligation but was not investigated at later time points. The up-regulation of genes belonging to such pathway could confer a better persistence potential to cells harboring a more activated and cytotoxic phenotype, which are not thought to persist long after adoptive transfer. Nonetheless, once this aAPC platform is translated into clinic, long-term blood tracking of TIL T-cell clones after infusion will be required to determine any beneficial effects on TIL persistence and whether any of these differentially-expressed genes correlate with differences in clinical response.

In addition to the up-regulation of genes belonging to different stem cell pathways, the differential gene expression profiling found increased expression of some unexpected genes. The transcription factor FOXP3 was surprising given that no other genes attributed to a Treg signature were overexpressed in TIL expanded with the aAPCSo far, other than FOXP3 being a maker for T-cell activation, no other conclusion can be currently drawn (24). Insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1), an endocrine mediator of growth and development, was also one of the most up-regulated genes in TIL expanded with aAPC compared to the feeder platform. IGF-1 was reported to be implicated in T-cell differentiation in the thymus as well as NK cell development and cytotoxic function (41, 42). One of the major genes found to be down-regulated in post-aAPC REP TIL was one of the 3 modules that constitutes fibronectin, FN1. FN1 is implicated in wound healing and high levels of this molecule were reported in IL-10 producer type 2 tumor-infiltrating macrophages, correlating with reduced survival in renal cancer (43, 44). Increased level of fibronectin in the serum has also been linked with a lack of clinical response to high-dose IL-2 therapy in melanoma and renal cell cancer patients (45). Literature linking FN1 and lymphocytes is mostly about expression of fibronectin following T-cells activation (4 to 7 days later); but not precisely on the FN1 constituent (46, 47). Since this constituent has been associated with immune-suppression and wound healing, its down-regulation in TIL expanded with aAPC compared to those amplified with feeders could be seen as a positive asset.

One of the major strengths of ACT with TIL is that the infusion product still retains a reasonable diverse T-cell repertoire generating specificity against multiple known and unknown tumor antigens (48). Some antigens are derived from self/mutated protein while others are not yet identified (28, 29). Targeting multiple tumor antigens simultaneously gives a strong advantage towards avoiding tumor escape due to antigen loss. This was a major point in our study; as we wanted to make sure that we were preserving an equivalent clonal diversity in comparison with the infusion product obtained by using the PBMC feeder platform. To do this we compared the clonal diversity generated with both platforms using the DTEA method to assess for expression of Vα and Vβ TCR and saw the preservation of the same array of different TCR α and β genes in post-REP TIL expanded using both methods. Furthermore, the anti-tumor CTL function of post-aAPC REP TIL against autologous or HLA-A-matched tumor targets was as efficient as the one observed with the TIL rapidly expanded using the conventional method. This was consistent with a similar level of intra-cytoplasmic cytotoxic granule protein content (Granzyme B/Perforin expression by flow cytometry).

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated significant expansion of melanoma TIL using genetically modified K562 as aAPC. Melanoma TIL can be comparably expanded with aAPC as with the PBMC feeders REP yielding cells with similar phenotypic and effector functional profiles as well as similar TCR gene diversity. However, some interesting differences were noted particularly in the gene expression profiles indicating that the aAPC REP may yield cells with a different functional phenotype in vivo after adoptive transfer. Thus, this will be determined in clinical trial with evaluation of clinical responses and long-term persistence tracking of the infused cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the MDACC TIL lab: Rahmatu Mansaray, Orenthial J. Fulbright, Renjith Ramachandran, Seth Wardell, Audrey Gonzalez and Valentina Dumitru. The authors would also like to thank all the additional clinical and research staff in the Melanoma Medical Oncology Department as well as the Division of Pediatrics at the MDACC that contributed to this study. This work is supported by the CPRIT grant (RP110553-P4) and Marie-Andrée Forget thanks CPRIT for her salary support. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support provided by the Adelson Medical Research Foundation (AMRF), and the Mulva Foundation as well as the National Institute of Health (NIH) Melanoma SPORE (P50 CA093459-08) and the R01 CA116206-09.

References

- 1.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Treves AJ, et al. Clinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short-term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2646–2655. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radvanyi LG, Bernatchez C, Zhang M, et al. Specific lymphocyte subsets predict response to adoptive cell therapy using expanded autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6758–6770. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4550–4557. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itzhaki O, Hovav E, Ziporen Y, et al. Establishment and large-scale expansion of minimally cultured “young” tumor infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive transfer therapy. J Immunother. 2011;34:212–220. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318209c94c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilon-Thomas S, Kuhn L, Ellwanger S, et al. Efficacy of adoptive cell transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after lymphopenia induction for metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2012;35:615–620. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31826e8f5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riddell SR, Watanabe KS, Goodrich JM, et al. Restoration of viral immunity in immunodeficient humans by the adoptive transfer of T cell clones. Science. 1992;257:238–241. doi: 10.1126/science.1352912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive-cell-transfer therapy for the treatment of patients with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:666–675. doi: 10.1038/nrc1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Shelton TE, et al. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother. 2003;26:332–342. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lozzio CB, Lozzio BB. Human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell-line with positive Philadelphia chromosome. Blood. 1975;45:321–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maus MV, Thomas AK, Leonard DG, et al. Ex vivo expansion of polyclonal and antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by artificial APCs expressing ligands for the T-cell receptor, CD28 and 4-1BB. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis-Mize KS, Dupuis M, MacKichan ML, et al. Plasmid DNA adsorbed onto cationic microparticles mediates target gene expression and antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Gene Therapy. 2000;7:2105–2112. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh H, Figliola MJ, Dawson MJ, et al. Reprogramming CD19-specific T cells with IL-21 signaling can improve adoptive immunotherapy of B-lineage malignancies. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3516–3527. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler MO, Lee JS, Ansen S, et al. Long-lived antitumor CD8+ lymphocytes for adoptive therapy generated using an artificial antigen-presenting cell. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1857–1867. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manuri PV, Wilson MH, Maiti SN, et al. piggyBac transposon/transposase system to generate CD19-specific T cells for the treatment of B-lineage malignancies. Human gene therapy. 2010;21:427–437. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vera JF, Brenner LJ, Gerdemann U, et al. Accelerated production of antigen-specific T cells for preclinical and clinical applications using gas-permeable rapid expansion cultureware (G-Rex) J Immunother. 2010;33:305–315. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181c0c3cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Liu S, Hernandez J, et al. MART-1-specific melanoma tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes maintaining CD28 expression have improved survival and expansion capability following antigenic restimulation in vitro. J Immunol. 2010;184:452–465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh H, Manuri PR, Olivares S, et al. Redirecting specificity of T-cell populations for CD19 using the Sleeping Beauty system. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2961–2971. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Maiti S, Bernatchez C, et al. A new approach to simultaneously quantify both TCR alpha- and beta-chain diversity after adoptive immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4733–4742. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He L, Hakimi J, Salha D, et al. A sensitive flow cytometry-based cytotoxic T-lymphocyte assay through detection of cleaved caspase 3 in target cells. J Immunol Methods. 2005;304:43–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero P, Zippelius A, Kurth I, et al. Four functionnally distinct populations of human effector-memory CD8+ T lymphocytes. Journal of immunology. 2007;178:4112–4119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh M, Seki S, Hashimoto W, et al. Cytotoxic gammadelta or alphabeta T cells with a natural killer cell marker, CD56, induced from human peripheral blood lymphocytes by a combination of IL-12 and IL-2. J Immunol. 1996;157:3886–3892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pittet MJ, Speiser DE, Valmori D, et al. Cutting edge: cytolytic effector function in human circulating CD8+ T cells closely correlates with CD56 surface expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:1148–1152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran DQ, Ramsey H, Shevach EM. Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+FOXP3 T cells by T-cell receptor stimulation is transforming growth factor-beta dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood. 2007;110:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaldjian EP, Gretz JE, Anderson AO, et al. Spatial and molecular organization of lymph node T cell cortex: a labyrinthine cavity bounded by an epithelium-like monolayer of fibroblastic reticular cells anchored to basement membrane-like extracellular matrix. International immunology. 2001;13:1243–1253. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.10.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon LA, Calloway PA, Welch TP, et al. CCR7/CCL21 migration on fibronectin is mediated by phospholipase Cgamma1 and ERK1/2 in primary T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38781–38787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.152173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kvistborg P, Shu CJ, Heemskerk B, et al. TIL therapy broadens the tumor-reactive CD8(+) T cell compartment in melanoma patients. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:409–418. doi: 10.4161/onci.18851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robbins PF, Lu YC, El-Gamil M, et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells. Nat Med. 2013;19:747–752. doi: 10.1038/nm.3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin J, Sabatino M, Somerville R, et al. Simplified method of the growth of human tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in gas-permeable flasks to numbers needed for patient treatment. J Immunother. 2012;35:283–292. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31824e801f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye Q, Loisiou M, Levine BL, et al. Engineered artificial antigen presenting cells facilitate direct and efficient expansion of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J Transl Med. 2011;9:131. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shuford WW, Klussman K, Tritchler DD, et al. 4-1BB costimulatory signals preferentially induce CD8+ T cell proliferation and lead to the amplification in vivo of cytotoxic T cell responses. J Exp Med. 1997;186:47–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman KM, Devillier LE, Feldman SA, et al. Augmented lymphocyte expansion from solid tumors with engineered cells for costimulatory enhancement. J Immunother. 2011;34:651–661. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31823284c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chacon JA, Wu RC, Sukhumalchandra P, et al. Co-stimulation through 4-1BB/CD137 improves the expansion and function of CD8(+) melanoma tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive T-cell therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu BQ, Ju SW, Shu YQ. CD137 enhances cytotoxicity of CD3(+)CD56(+) cells and their capacities to induce CD4(+) Th1 responses. Biomed Pharmacother. 2009;63:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez-Chacon JA, Li Y, Wu RC, et al. Costimulation through the CD137/4-1BB pathway protects human melanoma tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from activation-induced cell death and enhances antitumor effector function. J Immunother. 2011;34:236–250. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318209e7ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franceschetti M, Pievani A, Borleri G, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cells are terminally differentiated activated CD8 cytotoxic T-EMRA lymphocytes. Experimental hematology. 2009;37:616–628. e612. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Legat A, Speiser DE, Pircher H, et al. Inhibitory Receptor Expression Depends More Dominantly on Differentiation and Activation than “Exhaustion” of Human CD8 T Cells. Frontiers in immunology. 2013;4:455. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapuis AG, Thompson JA, Margolin KA, et al. Transferred melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells persist, mediate tumor regression, and acquire central memory phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4592–4597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113748109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee do Y, Choi BK, Lee DG, et al. 4-1BB Signaling Activates the T Cell Factor 1 Effector/beta-Catenin Pathway with Delayed Kinetics via ERK Signaling and Delayed PI3K/AKT Activation to Promote the Proliferation of CD8(+) T Cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kermani H, Goffinet L, Mottet M, et al. Expression of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor axis during Balb/c thymus ontogeny and effects of growth hormone upon ex vivo T cell differentiation. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2012;19:137–147. doi: 10.1159/000328844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni F, Sun R, Fu B, et al. IGF-1 promotes the development and cytotoxic activity of human NK cells. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, et al. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7303–7311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dannenmann SR, Thielicke J, Stockli M, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages subvert T-cell function and correlate with reduced survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e23562. doi: 10.4161/onci.23562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabatino M, Kim-Schulze S, Panelli MC, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor and fibronectin predict clinical response to high-dose interleukin-2 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2645–2652. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner C, Burger A, Radsak M, et al. Fibronectin synthesis by activated T lymphocytes: up-regulation of a surface-associated isoform with signalling function. Immunology. 2000;99:532–539. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blum S, Hug F, Hansch GM, et al. Fibronectin on activated T lymphocytes is bound to gangliosides and is present in detergent insoluble microdomains. Immunology and cell biology. 2005;83:167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersen RS, Thrue CA, Junker N, et al. Dissection of T-cell antigen specificity in human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1642–1650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.