Abstract

Impulsivity is a heritable, multifaceted construct with clinically relevant links to multiple psychopathologies. We assessed impulsivity in young adult (N~2100) participants in a longitudinal study, using self-report questionnaires and computer-based behavioral tasks. Analysis was restricted to the subset (N=426) who underwent genotyping. Multivariate association between impulsivity measures and single-nucleotide polymorphism data was implemented using parallel independent component analysis (Para-ICA). Pathways associated with multiple genes in components that correlated significantly with impulsivity phenotypes were then identified using a pathway enrichment analysis. Para-ICA revealed two significantly correlated genotype–phenotype component pairs. One impulsivity component included the reward responsiveness subscale and behavioral inhibition scale of the Behavioral-Inhibition System/Behavioral-Activation System scale, and the second impulsivity component included the non-planning subscale of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and the Experiential Discounting Task. Pathway analysis identified processes related to neurogenesis, nervous system signal generation/amplification, neurotransmission and immune response. We identified various genes and gene regulatory pathways associated with empirically derived impulsivity components. Our study suggests that gene networks implicated previously in brain development, neurotransmission and immune response are related to impulsive tendencies and behaviors.

Introduction

Impulsivity has been defined as ‘a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli with diminished regard to the negative consequences of these reactions to the impulsive individual or others'.1, 2, 3, 4 Impulsivity is a complex, multidimensional construct related to responses to rewards/punishments, attention and other cognitive processes.5 Impulsivity relates to multiple psychiatric disorders and abnormal behaviors, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, suicide, aggression and addiction.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders 5th edition (DSM V)6 defines impulse-control features and/or impulsive symptoms as major factors in the diagnosis of bipolar, attention-deficit/hyperactivity, conduct and antisocial and borderline personality disorders, among others.4,7 Impulsivity may predict suicidal behavior, psychopathy and conduct disorder, drug and alcohol problems.8

Impulsivity is genetically influenced and heritable.5,9 Offspring of parents with substance-use disorders have increased impulsivity,8 which may be transmitted as general risk factor for substance abuse.10,11 Some putatively related genes related to impulsive behaviors have been identified.12 Prior studies also report genetic associations in other impulsivity-associated pathological conditions including behavioral addictions and eating disorders, which may share similar neurobiological risk factors.13, 14, 15 Quantifying precise genetic underpinnings of impulsivity hold promise for intervention development for multiple psychiatric conditions.

Similar to other complex, inherited, behavioral phenotypes analogous to complex medical disorders such as obesity16 and psychological phenotypes such as extraversion are clearly influenced by multiple genes and also by environmental factors and their interactions. Various impulsivity-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in previous genome-wide association studies, including those associated with dopaminergic and serotonergic genes.17,18 Prior meta-analyses also link common variants in such genes to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and suicidal behaviors,19,20 which are characteristically impulsive. Most genetic studies utilize a univariate (often genome-wide association studies) approach; however, this method is hindered by high statistical threshold owing to multiple testing corrections for SNP numbers and does not take into account the aggregate effects of genetic variants, such as those that might underlie epistasis and other types of interrelationships that likely underpin complex phenotypes. The role of any individual gene in impulsivity remains unclear, likely attributable to the common disease common variant model alluded above, for which univariate approaches are not optimal. Thus, alternate approaches that consider such genetic aggregates are important to pursue.

Multivariate analyses such as parallel independent component analysis (Para-ICA) provide a sensitive and powerful alternative to traditional univariate analyses using single SNPs and single phenotypes. Para-ICA is typically more powerful than univariate analyses because it examines clusters of related individual phenotypic measures in relation to clusters of related SNPs that can be linked via annotation pathways to known molecular biological processes.21 Para-ICA derives both these phenotypic and SNP clusters empirically from the data set, in a hypothesis-free manner, to reveal novel, biologically relevant associations that might otherwise not be detected.22 Prior studies have shown that Para-ICA yields robust results with practical sample size of patients with various psychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia.21,23 Consequently, in the current study, we used Para-ICA22,24 to examine aggregate effects of common SNP variants underlying impulsivity-related constructs.

The main purpose of the current study was to uncover novel gene networks comprised of interacting SNPs associated with various impulsivity-related measures in a sample of healthy young adults. In addition, we aimed to identify the underlying molecular and biological mechanisms associated with these gene networks that might promote understanding the etiology of specific impulsivity-related behaviors and tendencies. Jupp and Dalley25 recently reviewed various neurotransmission systems (dopaminergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic, glutamergic, GABAergic, opoidergic, cholinergic and cannabinoids) that have a putative role in impulsivity. The importance of these neurotransmission systems may differ with respect to different aspects of impulsive behavior.25 In addition, brain organizational process during specific neurodevelopmental stages (such as adolescence) might impact the brain's motivation and inhibition substrates, influencing impulsive choice, risky behaviors and addiction risk.26 We hypothesized that the biological processes identified by Para-ICA would contain genes identified previously as associated with brain development; impulsive traits and impulsivity-related behavioral problems such as externalizing behaviors, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, suicidal behavior and substance abuse; nervous system signal generation, amplification or transduction; and neurotransmitter function, for example, their associated receptors, reuptake sites and synthetic/degrading enzymes.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study sample consisted of N=426 young adult freshman students who participated in the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism-funded Brain and Alcohol Research with College Students longitudinal study11 consisting of the subset of participants from the larger sample (N~2100) who provided genotyping data. Demographic information is shown in Table 1. All subjects provided written informed consent, approved by Hartford Hospital, Yale University, Trinity College and Central Connecticut State University. Exclusion criteria included current psychotic or bipolar disorder based on Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview,27 history of seizures, head injury with loss of consciousness >10 min, cerebral palsy, concussion in last 30 days, positive urine toxicological screens for common drugs of abuse and pregnancy. Although we did not collect classical intelligence quotient measures, we recorded Scholastic Assessment Test scores from all our participants. Prior studies have shown Scholastic Assessment Test scores to be a good predictor of intelligence quotient.28 Thus, intelligence quotient estimates were calculated using Scholastic Assessment Test scores as recommended by Frey and Detterman.28 Also, socio-economic status was calculated using the Hollingshead (1975) four factor index of social status.

Table 1. Demographic Information.

|

Demographic information

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | African American | Hispanic | Mixed/other | |||||

| |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

| Subjects (N) | 137 | 172 | 17 | 30 | 13 | 21 | 18 | 18 |

| Age range (years) | 17–24 | |||||||

| Mean age (years; s.d.) | 18.31 (0.77) | |||||||

Impulsivity-related measures

Five different self-report questionnaires and three behavioral tasks were used to measure impulsivity and related constructs. These measures were chosen to capture different facets of impulsivity and related constructs that had constituted separate factors in our prior research.3 Self-report measures were as follows: (i) Barrat Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11),29 (ii) Behavioral-Inhibition System/Behavioral-Activation System scale (BIS/BAS),30 (iii) Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ),31 (iv) Zuckerman Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS)32 and (v) Padua Inventory (PI).33 Computer-based behavioral tasks consisted of (i) two different versions of the Balloon Analog Risk Task (BART), the Java Neuropsychological Test (JANET) BART34 and conventional BART,35 and (ii) Experiential Discounting Task (EDT).36 Subscales used in our analysis included attention, motor and non-planning from BIS-11; drive, fun-seeking and reward responsiveness subscales from BAS; reward and punishment scales from SPSRQ; thrill and adventure seeking (ZTAS), experience seeking (ZES), disinhibition (ZDIS) and boredom susceptibility (ZBS) from SSS; total score from PI; total balloon pumps and pops from JANET BART; average adjusted pumps from conventional BART; and area under the curve from the EDT, yielding 18 total impulsivity scores and subscores that were included in the analysis. Missing impulsivity-related values (10.5-14.1%) were imputed with mean substitution using SPSS v19.0 (www.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/) and normalized.

SNP data collection and preprocessing

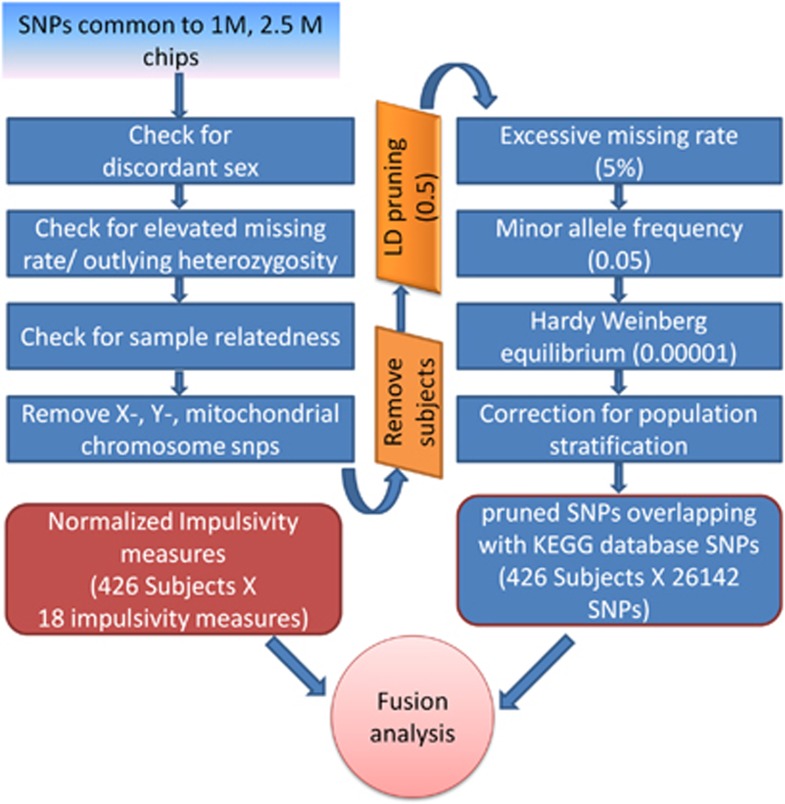

Genomic DNA was extracted with saliva collected from each subject using Oragene collection kits.37 Genotyping was performed using Illumina (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) HumanOmni1-Quad v1.0 Beadchip (~1 million target SNPs) for 237 subjects and Illumina HumanOmni2.5-8v1 BeadChip (~2.5 million target SNPs) for 189 subjects. Both chips had identical allele coding. The SNP data from both chips were merged in PLINK software (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/). SNPs common between two chips (N=582 300) were considered for further processing. We followed quality control steps of SNPs data using PLINK software as reported elsewhere.38 Figure 1 is a conceptual illustration of the preprocessing steps in quality control of SNP data. To increase independence between markers, SNPs in high-linkage disequilibrium were removed (window size in SNPs=50, number of SNPs to shift the window at each step=5 and r2>0.5). We performed principal component analysis using custom MATLAB scripts using algorithm similar to EIGENSTRAT.39 In order to correct for stratification bias, data were corrected using top two eigenvectors. Stratification bias was verified using Q–Q plot based on the P-values from the association test. To further reduce the number of SNPs for optimal employment of Para-ICA,22 we took processed SNPs and queried using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (www.genome.jp/kegg). Finally, 26 142 SNPs that were part of pathways in KEGG database were considered for Para-ICA.

Figure 1.

Illustration of quality control processing pipeline of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data. LD, linkage disequilibrium; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Genetic-impulsivity association

To identify associations between genetic and impulsivity-related data, Para-ICA from the Fusion ICA Toolbox (http://mialab.mrn.org/software/fit/) was used in MATLAB 7.7. Data were prepared for impulsivity analysis as (426 (subjects) × 18 (impulsivity-related measures)) and SNPs as (426 (subject) × 26142 (SNPs)), which were then input to Para-ICA.22,24 The number of independent components for impulsivity-related and SNPs data was calculated using minimum description length criteria40 and the number of components estimated was 6 for impulsivity-related measures and 17 for SNPs.

Correlations between modalities

Gene-impulsivity associations were established by examining correlations between loading coefficients between the SNP and impulsivity-related components. To account for confounding factors, partial correlation between loading coefficients of both modalities were computed controlling for calculated intelligence quotient scores, socio-economic status, age and sex using SPSS. Only those components surviving Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (P<0.05/(17 (SNP components) × 6 (impulsivity-related components))) were considered for further examination. Post hoc power calculation was performed on genotype–phenotype correlation pairs that survived multiple comparison corrected statistical threshold to ensure our sample adequately controlled the possibility of type II errors using G*Power software (http://www.gpower.hhu.de/).

Pathway analysis

Genes corresponding to dominant SNPs from the both (GC1 and GC2) genetic networks were selected using an arbitrary threshold |z| >2.5. To correct for gene-size bias, gene-based trait association value was calculated using VEGAS software.41 Genes with P<0.05 values were input for enrichment analysis in Metacore-based annotation software GeneGo (https://portal.genego.com/) and ConsensusPathDB (http://cpdb.molgen.mpg.de/). Both ConsensusPathDB enrichment analysis and GeneGo allowed examination of pathway and/or gene ontology categories corresponding to gene sets in each component. The quantitative enrichment scores were calculated using a hyper-geometric approach to estimate the likelihood that significant genes were overrepresented in particular biological pathways. To correct for multiple comparisons, significance values were adjusted using false-discovery rate.42

Results

Genetic-impulsivity associations

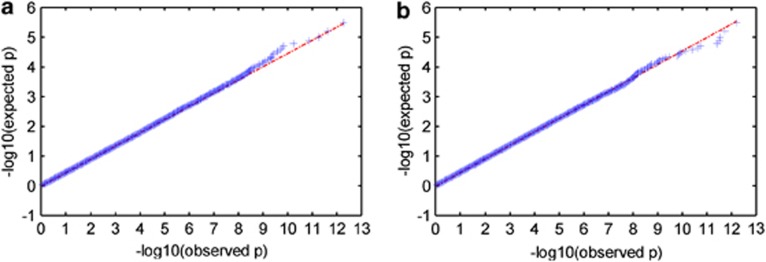

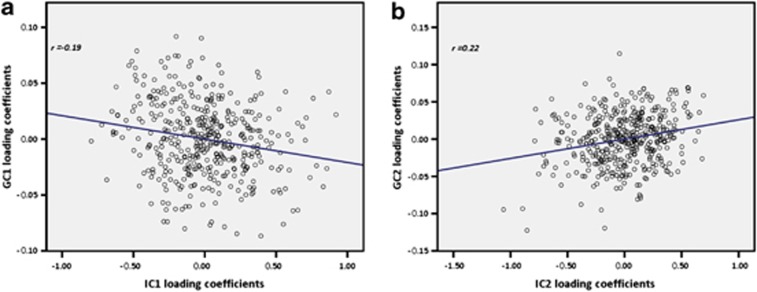

No significant inflation was noted in the association between loading coefficients and SNP data (see Figure 2 for Q–Q plot). Partial correlation controlling for calculated intelligent quotient, socio-economic status, age and sex revealed significant correlations between two independent impulsivity-related phenotypic components (IC1 and IC2) with two genetic components (GC1 and GC2). GC1 contained 618 SNPs from 304 genes and GC2 comprised 643 SNPs from 322 genes. The most significant impulsivity-related measures represented in IC1 were reward-sensitivity and Behavioral-Inhibition system scale scores of BIS/BAS scale.30 The most significant impulsivity-related measures represented in IC2 were the non-planning subscale score of the BIS-11 (ref. 29) and the area under the curve score from the EDT.36 IC1 correlated negatively with GC1 (r=−0.19, P=0.00008) and IC2 correlated positively with GC2 (r=0.22, P=0.000002). Scatter plots of both component pairs are shown in Figure 3. The top 20 most significant genes from each of the genetic components GC1 and GC2 are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Post hoc power analysis revealed power attained from IC1–GC1 and IC2–GC2 correlation pairs were 99.6% and 98.1%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Quantile-Quantile (Q–Q) plot of P-values for (a) IC1 and (b) IC2.

Figure 3.

(a) Scatter plots of loading coefficients of gene cluster GC1 and impulsivity component IC1; and (b) scatter plots of loading coefficients of gene cluster GC2 and impulsivity component IC2.

Table 2. List of the top 20 genes in GC1.

| SNP | Gene | Name | CHR | ZS | RW | Function | Associated disease and/or behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2269426 | TNXB a | Tenascin XB | 6p21.3 | −8.66 | 1.00 | Mediates interactions between cells and extracellular matrix. | SZ |

| rs2734335 | C2 | Complement component 2 | 6p21.3 | 7.60 | 0.87 | Part of complement system | Autoimmune disease, obesity |

| rs2072633 | RDBP | Negative elongation factor complex member B | 6p21.3 | 7.44 | 0.85 | Regulates elongation of transcription by RNA polymerase | Unknown |

| rs2559639 | CHST11 a | Carbohydrate sulfotransferase 11 | 12q23.3 | 6.90 | 0.79 | Catalyzes transfer of sulfate | Marijuana abuse |

| rs9266231 | HLA-B a | MHC class I, B | 6p21.3 | 6.79 | 0.78 | Immune system | MS, SZ, BP |

| rs2249742 | HLA-C a | MHC class I, C | 6p21.3 | −6.54 | 0.75 | Immune system | Psoriasis, SZ, BP |

| rs4151657 | CFB | Complement factor B | 6p21.3 | −6.54 | 0.75 | Part of complement system. | SZ |

| rs3134798 | NOTCH4 a | Notch4 | 6p21.3 | 6.38 | 0.73 | Cognition, brain development. | SZ, AD, BP |

| rs6931646 | HLA-DRA a | MHC class II, DR alpha | 6p21.3 | 6.12 | 0.70 | Immune system | AD, BP, PD, obesity |

| rs2844519 | MICA | MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A | 6p21.33 | 5.43 | 0.62 | Antigen presentation. | AD |

| rs151719 | HLA-DMB a | MHC class II, DM beta | 6p21.3 | 5.27 | 0.60 | Peptide loading of MHC class II molecules by helping release the CLIP. | SZ, MS, obesity |

| rs1787729 | DCC a | Deleted in colorectal carcinoma | 18q21.3 | 5.20 | 0.60 | Axon and neuronal guidance. | SZ, depression |

| rs2741566 | PIGT | Phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class T | 20q12–q13.12 | 5.01 | 0.57 | Component of GPI transamidase complex | Unknown |

| rs1511179 | CTNNA2 a | Catenin, alpha 2 | 2p12-p11.1 | −4.66 | 0.53 | Cell–cell adhesion and differentiation in nervous system | Excitement seeking/risk taking, AD, ADHD |

| rs2213565 | HLA-DQA2 a | MHC class II, DQ alpha 2 | 6p21.3 | 4.62 | 0.53 | Peptide loading of MHC class II beta chain. | Obesity, BP, SZ |

| rs2544800 | SULT2B1 | Sulfotransferase family, cytosolic, 2B, member 1 | 19q13.3 | 4.61 | 0.53 | Catalyzes sulfate conjugation of many hormones, neurotransmitters, drugs and xenobiotic compounds | PD |

| rs1152663 | CTBP2 a | C-terminal binding protein 2 | 10q26.13 | 4.60 | 0.53 | Targets diverse transcription regulators | TBI |

| rs9664844 | PRKG1 a | Protein kinase, cGMP dependent, type I | 10q11.2 | 4.48 | 0.51 | Nitric oxide/cGMP signaling pathway | SZ, AD |

| rs3117578 | CSNK2B a | Casein kinase 2, beta polypeptide | 6p21.3 | 4.46 | 0.51 | Wnt signaling pathway. Regulates basal catalytic activity of the alpha subunit | Unknown |

| rs7176717 | RORA a | RAR-related orphan receptor A | 15q22.2 | −4.43 | 0.51 | DA/GLU signaling, circadian rhythms, learning | Autism, PTSD, Depression, BP, MDD |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BP, bipolar; CHR, chromosome; CLIP, class II-associated invariant chain peptide; MDD, major depressive disorder; MHC, major histocompatibilty complex; MS, multiple sclerosis; PD, Parkinson's disease; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RW, rank weights; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SZ, schizophrenia; TBI, traumatic brain injury; ZS, Z-score.

Multiple SNP occurrence (>2) in gene network. Information provided was gathered from PubMed, genecards and gene associated databases. Refer to Supplementary Table S4 for detailed references.

Table 3. List of the top 20 genes in GC2.

| SNP | Gene | Name | CHR | ZS | RW | Function | Associated disease and/or behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1008805 | CYP19A1 a | Cytochrome p450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | 15q21.1 | −5.05 | 1.00 | Regulates aromatase activity in catalyzing estrogen biosynthesis from androgens | Obesity, impulsivity |

| rs6467802 | ATP6V0A4 a | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0 subunit a4 | 7q34 | −4.82 | 0.95 | Neurotransmitter release | Unknown |

| rs6952633 | PDE1C | Phosphodiesterase 1C | 7p14.3 | 4.79 | 0.94 | Neuronal plasticity. Hydrolyzes cAMP and cGMP | Male mating problems in melanogaster |

| rs1224391 | PRKG1 a | Refer to Table 4 | — | 4.76 | 0.94 | — | — |

| rs8028974 | RYR3 a | Ryanodine receptor 3 | 15q14–q15 | 4.60 | 0.91 | Relases calcium from intracellular storage. Neuronal plasticity. Role in CBF and pathological brain response | Social contact, pain sensitivity, fear conditioning |

| rs12777566 | CTNNA3 | Catenin alpha 3 | 10q22.2 | −4.57 | 0.90 | Cell–cell adhesion | AD |

| rs9650418 | PPP2R2A | Protein phosphatase 2, regulatory subunit B, alpha | 8p21.2 | 4.53 | 0.89 | Unknown | Height |

| rs1313762 | ABCG2 a | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G, member 2 | 4q22 | 4.52 | 0.89 | Brain development. | AD, drug abuse |

| rs8080721 | PRKCA a | Protein kinase C, alpha | 17q22–q23.2 | 4.51 | 0.89 | Emotional memory formation | PTSD, SZ, alcoholism, obesity |

| rs1704917 | CHST11 | Refer to Table 4 | — | 4.44 | 0.87 | — | — |

| rs924138 | ABCC1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C, member 1 | 16p13.1 | 4.41 | 0.87 | Brain development. Drug transport across CNS | AD, neurodevelopment disorders |

| rs918241 | RYR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 | 1q43 | −4.39 | 0.86 | Role in CBF and pathological responses in brain. Neuronal plasticity | SZ |

| rs4416750 | MGAM | Maltase–glucoamylase | 7q34 | −4.38 | 0.86 | Brain maturation | Unknown |

| rs751933 | KCNK5 | Potassium channel, subfamily K, member 5 | 6p21 | 4.36 | 0.86 | Cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis. Sensitive to environmental stimuli, for example, pH, glucose | MS |

| rs362794 | RELN a | Reelin | 7q22 | −4.32 | 0.85 | Synaptic plasticity, brain development. Functional and behavioral development in juvenile prefrontal circuits | ASD, SZ, BP, MDD, AD, impulsivity |

| rs16531 | CACNB1 | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, beta 1 | 17q21–q22 | 4.23 | 0.83 | Synaptic transmission | Unknown |

| rs1709834 | PRKCH | Protein kinase C, Eta | 14q23.1 | −4.21 | 0.83 | NRG1 interactor in neurite formation | SZ, MDD |

| rs1460756 | MAPK10 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 10 | 4q22.1–q23 | 4.21 | 0.83 | Neuronal proliferation, differentiation, migration | Anxiety |

| rs16948648 | ITGA3 | Integrin alpha 3 | 17q21.33 | 4.17 | 0.82 | Transmembrane glycoprotein connecting extracellular matrix to cytoskeleton | Neural tube defects, SZ |

| rs7811880 | WBSCR17 a | Williams–Beuren syndrome chromosome region 17 | 7q11.23 | 4.13 | 0.81 | Lamellipodium formation, O-glycosylation, macropinocytosis | Williams–Beuren syndrome |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BP, bipolar; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CHR, chromosome; CNS, central nervous system; MDD, major depressive disorder; MS, multiple sclerosis; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RW, rank weights; SZ, schizophrenia; ZS, Z-score.

Multiple SNP occurrence (>2) in gene network. Information provided was gathered from PubMed, genecards and gene associated databases. Refer to Supplementary Information Table S5 for detailed references.

Pathway analysis

Pathways associated with GC1 (associated with IC1) included calcium signaling, cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), cholinergic synapse, long-term depression (LTD), long-term potentiation and various immune response pathways. Similarly pathways associated with GC2 (associated with IC2) included focal adhesion, calcium signaling, LTD, long-term potentiation, glutamate regulation of dopamine D1A receptor signaling and various immune response pathways. Top 10 KEGG and GeneGo pathways associated with GC1 and GC2 along with their P-values and q-values are listed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Also, genes overlapping with gene clusters and top 10 significant pathways are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Table 4. List of top 10 significant pathways for GC1.

| Pathways | P-value | q-value |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG pathways | ||

| Calcium signaling | 2.18 × 10−15 | 4.14 × 10−13 |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 1.90 × 10−14 | 1.80 × 10−12 |

| Long-term depression | 1.75 × 10−11 | 1.11 × 10−09 |

| Circadian entrainment | 2.97 × 10−11 | 1.41 × 10−09 |

| Cell adhesion molecules | 7.24 × 10−11 | 2.75 × 10−09 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 2.49 × 10−10 | 7.18 × 10−09 |

| Pathways in cancer | 2.64 × 10−10 | 7.18 × 10−09 |

| Cholinergic synapse | 4.27 × 10−10 | 9.61 × 10−09 |

| MAPK signaling pathway | 4.55 × 10−10 | 9.61 × 10−09 |

| Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling | 7.37 × 10−10 | 1.40 × 10−08 |

| GeneGo pathways | ||

| Neurophysiological process_ACM regulation of nerve impulse | 7.05 × 10−09 | 4.12 × 10−06 |

| Immune response_NFAT in immune response | 2.51 × 10−08 | 6.20 × 10−06 |

| Signal transduction_Activation of PKC via G-protein-coupled receptor | 3.18 × 10−08 | 6.20 × 10−06 |

| Immune response_BCR | 5.01 × 10−08 | 7.32 × 10−06 |

| Neurophysiological process_NMDA-dependent postsynaptic long-term potentiation in CA1 hippocampal neurons | 9.51 × 10−08 | 1.11 × 10−05 |

| Development_Gastrin in differentiation of the gastric mucosa | 1.20 × 10−07 | 1.17 × 10−05 |

| Immune response_IL-22 signaling | 4.97 × 10−07 | 4.15 × 10−05 |

| Immune response_Fc epsilon RI | 5.74 × 10−07 | 4.19 × 10−05 |

| Immune response_CCR5 signaling in macrophages and T lymphocytes | 1.01 × 10−06 | 6.05 × 10−05 |

| Transport_Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor regulation of ion channels | 1.04 × 10−06 | 6.05 × 10−05 |

Abbreviations: KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; BCR, B-cell antigen receptor; IL, interleukin; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; PKC, protein kinase C.

Uncorrected and false-discovery rate corrected P-values are reported in the table.

Table 5. List of top 10 significant pathways for GC2.

| Pathways | P-value | q-value |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG pathways | ||

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 1.2 × 10−23 | 2.3 × 10−21 |

| Pathways in cancer | 2.2 × 10−19 | 2.2 × 10−17 |

| Focal adhesion | 4.2 × 10−19 | 2.7 × 10−17 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1.6 × 10−17 | 6.9 × 10−16 |

| MAPK signaling | 1.7 × 10−17 | 6.9 × 10−16 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 3.1 × 10−17 | 1.0 × 10−15 |

| Calcium signaling | 4.3 × 10−17 | 1.2 × 10−15 |

| PI3K-Akt signaling | 2.7 × 10−13 | 6.8 × 10−12 |

| Vascular smooth muscle contraction | 1.5 × 10−11 | 3.4 × 10−10 |

| Long-term depression | 5.8 × 10−11 | 1.1 × 10−09 |

| GeneGo pathways | ||

| Signal transduction_Activation of PKC via G-protein-coupled receptor | 1.0 × 10−09 | 6.3 × 10−07 |

| Immune response_Fc epsilon RI | 2.5 × 10−08 | 6.1 × 10−06 |

| Immune response_CD28 signaling | 3.1 × 10−08 | 6.1 × 10−06 |

| Immune response_CCR5 signaling in macrophages and T lymphocytes | 4.8 × 10−08 | 7.0 × 10−06 |

| Neurophysiological process_Long-term depression in cerebellum | 7.2 × 10−08 | 8.4 × 10−06 |

| Immune response_NFAT in immune response | 1.1 × 10−07 | 1.0 × 10−05 |

| Immune response_T cell receptor signaling | 1.7 × 10−07 | 1.4 × 10−05 |

| Neurophysiological process_NMDA-dependent postsynaptic long-term potentiation in CA1 hippocampal neurons | 2.6 × 10−07 | 1.9 × 10−05 |

| Glutamate regulation of dopamine D1A receptor signaling Glutamate regulation of Dopamine D1A receptor signaling | 3.1 × 10−07 | 2.0 × 10−05 |

| Ca(2+)-dependent NF-AT signaling in cardiac hypertrophy | 3.7 × 10−07 | 2.1 × 10−05 |

Abbreviations: KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; PKC, protein kinase C.

Uncorrected and false-discovery rate corrected P-values are reported in the table. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Discussion

In this study, we used a multivariate technique, Para-ICA, to investigate the genetic associations of impulsivity traits in young adults. We hypothesized that the biological classes and processes identified by Para-ICA-derived gene components would contain a significant excess of genes identified previously with risk for impulsive traits and impulsivity-related behavioral problems, as well as pathways associated with brain development, nervous system signal generation, amplification or transduction and neurotransmission. The impulsivity measures included in the current analysis were based on our previous study.3 Given that impulsivity construct validity and theoretical overlap remains a topic of active research, future studies could consider adding various other impulsivity assessments and explore their genetic associations in attempts to refine our understanding of impulsivity genotype–phenotype relationships.

Phenotypic component IC1 (BAS-Reward and BIS) represented an impulsivity construct describing self-reported tendencies relating to propensities to seek out rewarding situations and the regulation of aversive motivations, and IC2 (BIS-11 non-planning and EDT) represented an impulsivity construct relating to propensities of focusing on present rather than future events and the favoring of immediate rewards over longer-term consequences. Prior studies suggest a multidimensional nature of impulsivity; however, how best to parse impulsivity-related domains remains debated.5 Impulsivity-related constructs may vary depending upon the number and types of tests administered.3,43 The impulsivity-related components emerging from the current study differ from those we reported in a prior study.3 Components extracted in this study (Supplementary Table S3) were based on ICA, which differs conceptually and empirically from the principal component analysis used previously. Para-ICA constrains both genotype and phenotype components to maximize their cross-correlation,22 which likely explains differences in component structure. Additional differences may relate to the sample and the impulsivity measures used in the study. In the current study, the JANET BART was included along with four submeasures (thrill and adventure seeking, experience seeking, disinhibition and boredom susceptibility) from the SSS instead of the SSS total score used in our prior study.

Pathway analysis revealed various pathways related to neural development (for example, CAMs in GC1 and focal adhesion in GC2). The association of these pathways seems plausible and suggests neurodevelopmental effects on impulsive behavior. CAM pathways have a vital role in neurogenesis, immune response, interneuronal signaling for learning and memory, and brain development.44 In addition, CAMs are associated with cognition45 and various neuropsychiatric disorders.46 Also, prior studies point to various CAM genes in addiction vulnerability.47 Neuronal CAM gene, implicated in the CAM pathway (Supplementary Table S1) is involved in neuron–neuron adhesion and promotes directional signaling during axonal cone growth. Neuronal CAM has been associated with drug abuse and personality characteristics such as novelty seeking and reward dependence.48 Focal adhesion pathways are responsible for cell motility, proliferation, differentiation, survival and regulation of gene expression,49 and have a major role in central nervous system development. The mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway significantly associated with GC1 and GC2 is involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation and migration. Mitogen-activated protein kinases have a role in various neurodegenerative diseases.50 The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway associated with GC2 have key role in controlling cellular processes by phosphorylating substrates involved in apoptosis, protein synthesis, metabolism and the cell cycle. Also, PI3K/Akt signaling promotes neural development in hippocampus and has been associated with cognition.51 Mitogen-activated protein kinase and PI3K/Akt pathways influence focal adhesion kinases that are responsible for neurogenesis via integrin signaling.52,53 Integrin complex genes overlap between GC2 and both focal adhesion and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). In addition, abnormality in hippocampal neurogenesis has been linked to impairment of hippocampal-related learning and memory and addiction vulnerability.54

Unexpectedly, we found that the first gene component GC1 contained multiple examples of genes related to the major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) classes I and II, and to complement components that are primarily known for immune-related functions. Eight such gene SNPs occurred among the 20 most significantly ranked within GC1, with multiple occurrences of different SNPs from the same genes reoccurring in the same component. In recent years, much attention has been given to the role of MHC proteins, particularly MHC class I, in brain development and plasticity.55,56 These proteins contribute importantly to neuronal differentiation, synapse formation, synaptic function, synaptic plasticity and activity-dependent refinement of synaptic connections,55 as well as in modulating behavior and stress reactivity, possibly through hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function.56 Immune-related genes are associated with genetic risk for alcoholism.57 MHC class II antigens are associated with obesity.58 In addition, association of immune-related genes in schizophrenia has received recent attention.59 The MHC and complement genes, together with other top-ranked SNP members of GC1, are all located on 6p21.3 (Table 2). Tenascin XB, a MHC class II gene, was the top-ranked gene in GC1. Tenascin XB mediates interactions between cell and extracellular matrix, and has been reported to be associated with schizophrenia,59 a disorder in which impulsivity has been identified as major problem.60

The top-ranked gene in GC2, cytochrome p450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 (CYP19A1), regulates aromatase activity in catalyzing estrogen biosynthesis from androgens. Androgens are involved in the regulation of aggression, cognition, emotion and personality,61 with aromatase activity associated with aggression, including impulsive aggression, in humans and animals.62

Among the top 20 most significant genes in our gene networks, we identified many associated with neurogenesis, brain development and several previously reported to be associated with impulsive behaviors. Notch4, among the top 20 genes in GC1, is reportedly involved in neurodevelopment, learning, memory and late-life neurodegeneration.63 DCC (deleted in colorectal carcinoma) that has a critical role in brain development via axon and neuronal guidance,64 and in reorganizing dopamine circuitry,65 was among the top genes in GC1. As dopaminergic system is linked to impulsivity,17 association of DCC and impulsivity seems plausible. Also, increased DCC expression was found in brain of people who committed suicide.66 CAMs, including catenin (CTNNA2 and CTNNA3) were among the top 20 genes in gene clusters GC1 and GC2. Catenin alpha 2 (CTNNA2) is expressed in prefrontal, temporal and cingulate cortex, hypothalamus and amygdala; brain regions associated with executive function, learning and emotion. In addition, CTNNA2 was previously identified as a gene associated with excitement seeking/risk taking.12 Ryanodine receptor genes (RYR2 and RYR3), among the top 20 genes in GC2, mediate calcium signaling and are important for neuronal plasticity.67 Prior studies reported RYRs to have roles in cerebral blood flow and brain responses.68 Also, RYRs expression is regulated by dopamine D1 receptor signaling system.69 Dopaminergic system has been associated with impulsivity,17,25 which suggest role of RYRs in impulsivity. Also, maltase-glucoamylase, which was among the top 20 genes in GC2, has role in brain maturation.70

The RAR-related orphan receptor (RORA), a nuclear hormone receptor gene, has an important role in maintaining circadian rhythms and immune system,71 and was among the top 20 genes in GC1. Prior mouse studies show the RORA gene to be expressed strongly in the cerebellum and thalamus.72 In addition, RORA has been associated with learning ability73 and mood disorder personality trait in neuroticism.71 Top 20 ranked genes in GC2 included protein kinase C, protein kinase C-alpha (PRKCA) and Reelin. PRKCA is involved in cell proliferation and cell growth arrest by positive and negative regulation of cell cycle, and has an important role in learning and memory.74 PRKCA has been associated with alcoholism,75 obesity,76 memory impairment77 and predisposition to strong emotional memory.74 Reelin, whose main function is layering of neurons in cerebellum cortex and cerebellum has an important role in neural plasticity and development,78 and also has been associated with executive function.79 Also, interaction of brain dopaminergic, serotonergic and opioid systems with Reelin have role in anxiety and impulsivity.80

We identified various pathways related to nervous system signal generation, amplification or transduction (calcium signaling, LTD, activation of protein kinase C via G-protein-coupled receptor, N-methyl-D-aspartate-dependent long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 neurons in both GC1 and GC2, and cholinergic receptor, muscarinin (ACM) regulation of nerve impulse in GC1). Calcium signaling was the top-most significant pathways in GC1, and is important in neuronal synaptic transmission, signal transduction and cell signaling.81 Association of this pathway seems plausible because calcium signaling has also been linked with dopamine receptors that have a significant role in impulsivity-associated behaviors.17,81 Also, calcium signaling pathway is associated with opioid dependence.82 Calcium signaling is also important in neural plasticity and has been linked with neurodegenerative diseases.83 Thus, our finding suggests that altered calcium signaling might relate to impulsivity-related behaviors. LTD has an important role in learning and memory and is altered in various pathological conditions.84 In addition, LTD is involved in adolescent cognitive and executive function85 and has been associated with drug addiction and acute stress.86 ACM participate in many physiological processes through regulation of calcium ion transport (for example, regulation of neuronal neurotransmitter release). Long-term potentiation is responsible for learning and memory.87 Prior study reported abnormal protein kinase C signaling in prefrontal cortex to be associated with impulsivity, distraction and impaired judgment.88

Pathways related to neurotransmission (cholinergic synapse, retrograde endocannabinoid signaling, alpha 2 adrenergic receptor regulation of ion channels in GC1 and glutamate regulation of dopamine D1A receptor signaling in GC2) were significantly associated with our gene clusters. Implication of these pathways in our study supports prevailing hypothesis that impulsive behaviors are modulated by neurotransmitters and their receptors.89 The cholinergic signaling pathway modulates neural differentiation, neurogenesis, involved in synaptic plasticity90 and neural development.91 Also, acetylcholine function is associated with impulsive action.92 The retrograde endocannabinoid signaling pathway regulates axonal growth and guidance during development and adult neurogenesis.93 The associated cannabinoid receptor (CB1) is expressed in hippocampus, basal ganglia and cerebellum;94 rodent studies suggest that CB1 and CB2 receptors has a role in regulation of impulsive behaviors.94,95 The endocannabinoid system also has been associated with substance abuse, addiction and other psychiatric disorders.96 The type-1 cannabinoid receptor may also moderate the relationship between trait impulsivity and marijuana-related behavioral problems.97 Identification of glutamate regulation of dopamine D1A receptor signaling pathways was consistent with prior studies reporting glutamate and dopamine involvement in impulsivity.17,20

Circadian entrainment pathway was associated with GC1. Prior study has shown association of sleep duration and impulsivity in men.98 Serotonin, a key neurotransmitter is associated with both impulsivity and sleep/wake cycle.17,98 Serotonin and circadian systems of brain are linked both anatomically and genetically through various signaling molecules.99 Thus, implication of circadian pathways suggests that abnormal circadian rhythm might induce impulsive behavior. Other significant pathways were related to cardiovascular diseases including various cardiomyopathy-associated pathways. Most of the genes overlapping with gene cluster and pathways were calcium signaling, integrin and CAMs (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Also, these genes are most likely expressed in brain as well as heart. Nuclear factor of activated T cells in immune response and Ca(2+)-dependent nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling in cardiac hypertrophy were among significant pathways. Members of the nuclear factor of activated T cells family of transcription factors are implicated in shaping neuronal function throughout the nervous system. Also, stimulation of D1 dopamine receptors induces nuclear factor of activated T cells-dependent transcription through activation of L-type calcium channels.100 To our surprise, pathways in cancer was associated with both GC1 and GC2. However, genes overlapping between gene clusters and pathways were associated with neurogenesis (AKT2, AKT3, integrin molecules and CAMs), calcium signaling (RYRs and PRKCA), regulation of neurotransmitters (AKT2, AKT3 and BCL2; Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Also, overlapping genes CTNNA2, RYRs and PRKCA (also among the top 20 genes in GC1 and GC2) are associated with impulsive behavior and disorders associated with impulsivity (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5).

Limitations and future directions

Owing to limitation of Para-ICA, we were only able to include a subset of SNP data in the analysis. Thus, it is possible that we overlooked other genetic components that potentially might be associated with impulsivity. Current study was limited with sample from young adults (age 18–24 years). Also, current study does not take into account the current medications, substance abuse that might have confounding effects on their impulsive behaviors. There are multiple other impulsivity measures that were not included in the current study. Impulsivity measures in our study were based on those used in our prior studies and limited by the number of test batteries that could be practically completed in a single test session without risking participant fatigue and disengagement. Future studies should consider other impulsivity assessments to further investigate their genetic and biological associations.

Conclusion

In the current study, we used the multivariate technique Para-ICA to identify genetic associations with impulsivity-related measures and identified various genetic pathways and genes associated with impulsivity and related constructs. Many of the genetic pathways identified contribute to brain development, nervous system signal generation, amplification or transduction, neurotransmitter regulation, calcium signaling and immune response. This study suggests that these pathways and associated genes contribute to impulsive behaviors in young adults. Furthermore, pathways identified in current study might be potential target sites for medication development and a future research area for various psychiatric conditions characterized by elevated impulsivity.

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants AA016599 & AA19036 to Dr GD Pearlson.

MNP has received financial support or compensation for the following: MNP has consulted for Ironwood and Lundbeck; has received research support from Mohegan Sun Casino, the National Center for Responsible Gaming and Psyadon pharmaceuticals; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse-control disorders or other health topics; has consulted for law offices and gambling entities on issues related to impulse-control disorders; provides clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program; has performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; has edited journals or journal sections; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Canli T, Congdon E, Todd Constable R, , Lesch KP. Additive effects of serotonin transporter and tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene variation on neural correlates of affective processing. Biol Psychology. 2008;79:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon E, Lesch KP, , Canli T. Analysis of DRD4 and DAT polymorphisms and behavioral inhibition in healthy adults: implications for impulsivity. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:27–32. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Stevens MC, Potenza MN, Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, , Andrews MM, et al. Investigating the behavioral and self-report constructs of impulsivity domains using principal component analysis. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:390–399. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833113a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, , Swann AC. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. AM J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1783–1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, Chamberlain SR, Goudriaan AE, Stein DJ, Vanderschuren LJ, , Gillan CM, et al. New developments in human neurocognition: clinical, genetic, and brain imaging correlates of impulsivity and compulsivity. CNS Spect. 2014;19:69–89. doi: 10.1017/S1092852913000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, and clinical utility. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:727–729. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a2168a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, , Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychiatry of impulsivity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:255–261. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280ba4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Lawrence AJ, , Clark L. Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:777–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestri M, Calati R, Serretti A, , De Ronchi D. Genetic modulation of personality traits: a systematic review of the literature. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;29:1–15. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328364590b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cservenka A, , Nagel BJ. Risky decision-making: an FMRI study of youth at high risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:604–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dager AD, Anderson BM, Stevens MC, Pulido C, Rosen R, , Jiantonio-Kelly RE, et al. Influence of alcohol use and family history of alcoholism on neural response to alcohol cues in college drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:E161–E171. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Esko T, Sutin AR, de Moor MH, Meirelles O, , Zhu G, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies common variants in CTNNA2 associated with excitement-seeking. Transl Psychiatry. 2011;1:e49. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Tomasi D, , Baler RD. Obesity and addiction: neurobiological overlaps. Obes Rev. 2013;14:2–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua L, Goldman D. Genetics of impulsive behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120380. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ. The serotonergic system in mood disorders and suicidal behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120537. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manco M, , Dallapiccola B. Genetics of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics. 2012;130:123–133. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, , Roiser JP. Dopamine, serotonin and impulsivity. Neuroscience. 2012;215:42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorwood P, Le Strat Y, Ramoz N, Dubertret C, Moalic JM, , Simonneau M. Genetics of dopamine receptors and drug addiction. Human Genet. 2012;131:803–822. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, , He L. Meta-analysis supports association between serotonin transporter (5-HTT) and suicidal behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:47–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Sham PC, Owen MJ, , He L. Meta-analysis shows significant association between dopamine system genes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2276–2284. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Ruano G, Windemuth A, O'Neil K, Berwise C, , Dunn SM, et al. Multivariate analysis reveals genetic associations of the resting default mode network in psychotic bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2066–E2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313093111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Demirci O, , Calhoun VD. A parallel independent component analysis approach to investigate genomic influence on brain function. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2008;15:413–416. doi: 10.1109/LSP.2008.922513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Narayanan B, Liu J, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Stevens MC, , Calhoun VD, et al. A large scale multivariate parallel ICA method reveals novel imaging-genetic relationships for Alzheimer's disease in the ADNI cohort. NeuroImage. 2012;60:1608–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Pearlson G, Windemuth A, Ruano G, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, , Calhoun V. Combining fMRI and SNP data to investigate connections between brain function and genetics using parallel ICA. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:241–255. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B, , Dalley JW. Convergent pharmacological mechanisms in impulsivity and addiction: insights from rodent models. Br J Pharmacol. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chambers RA, Taylor JR, , Potenza MN. Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: a critical period of addiction vulnerability. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1041–1052. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, , Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:4–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey MC, , Detterman DK. Scholastic Assessment or g? The relationship between the Scholastic Assessment Test and general cognitive ability. Psychol Sci. 2004;15:373–378. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, , Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, , White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Torrubia R, Avila C, Molto J, , Caseras X. The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray's anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;31:837–862. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, , Neeb M. Sensation seeking and psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 1979;1:255–264. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberger LG, , Burns GL. Obsessions and compulsions: psychometric properties of the Padua Inventory with an American college population. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:341–345. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90087-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkil S, Satish S, Mathew SS, Dinesh N, Kumar CT, , Lombardo LE, et al. Cross-cultural standardization of the South Texas Assessment of Neurocognition in India. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136:280–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MK, Hopko DR, Bare R, Lejuez CW, , Robinson EV. Construct validity of the Balloon Analog Risk Task (BART): associations with psychopathy and impulsivity. Assessment. 2005;12:416–428. doi: 10.1177/1073191105278740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, , Schiffbauer R. Measuring state changes in human delay discounting: an experiential discounting task. Behav Process. 2004;67:343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes AP, Oliveira IO, Santos BR, Millech C, Silva LP, , Gonzalez DA, et al. Quality of DNA extracted from saliva samples collected with the Oragene DNA self-collection kit. BMC Med Res Method. 2012;12:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Clarke GM, Cardon LR, Morris AP, , Zondervan KT. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1564–1573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, , Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, , Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;14:140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JZ, McRae AF, Nyholt DR, Medland SE, Wray NR, , Brown KM, et al. A versatile gene-based test for genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner-Benaim A. FDR control by the BH procedure for two-sided correlated tests with implications to gene expression data analysis. Biom J. 2007;49:107–126. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200510313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, , O'Malley SS, et al. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addict Biol. 2010;15:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DL, Schnapp LM, Shapiro L, , Huntley GW. Making memories stick: cell-adhesion molecules in synaptic plasticity. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:473–482. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01838-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, Tucci V, Nolan PM, Schachner M, Jakovcevski I, , Kheifets A, et al. Cognitive assessment of mice strains heterozygous for cell-adhesion genes reveals strain-specific alterations in timing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Biol Sci. 2014;369:20120464. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvin AP. Neuronal cell adhesion genes: key players in risk for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other neurodevelopmental brain disorders? Cell Adh Migr. 2010;4:511–514. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.4.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR. Molecular genetics of addiction vulnerability. NeuroRx. 2006;3:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo BK, Shim JC, Lee BD, Kim C, Chung YI, , Park JM, et al. Association of the neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NrCAM) gene variants with personality traits and addictive symptoms in methamphetamine use disorder. Psychiatry Invest. 2012;9:400–407. doi: 10.4306/pi.2012.9.4.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, , Mitra SK. Multiple connections link FAK to cell motility and invasion. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EK, , Choi EJ. Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochimica et Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Zhang H, Kang T, Zhang JJ, Yang Y, , Liu H, et al. PI3K/Akt signal pathway involved in the cognitive impairment caused by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rats. PloS One. 2013;8:e81901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan JL. Role of focal adhesion kinase in integrin signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik-Stanaszek L, Gregor A, , Zalewska T. Regulation of neurogenesis by extracellular matrix and integrins. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 2011;71:103–112. doi: 10.55782/ane-2011-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RA. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the pathogenesis of addiction and dual diagnosis disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister AK. Major histocompatibility complex I in brain development and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar A, MacKenzie RN, , Foster JA. Loss of class I MHC function alters behavior and stress reactivity. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;244:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT. Immune function genes, genetics, and the neurobiology of addiction. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2012;34:355–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio J. MHC class II pathway mediates adipose inflammation. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:252. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Sun S, Zhang L, Wang Z, Ye L, , Liu L, et al. Further study of genetic association between the TNXB locus and schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet. 2011;21:216. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283413398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzir M. Impulsivity in schizophrenia: a comprehensive update. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;18:247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow DR, , Schmidt PJ. Androgens, brain, and behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:974–984. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor BC, Kyomen HH, , Marler CA. Estrogenic encounters: how interactions between aromatase and the environment modulate aggression. Front Neuroendocr. 2006;27:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasky JL, , Wu H. Notch signaling, brain development, and human disease. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:104R–109RR. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000159632.70510.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Gao J, Zhang H, Sun L, , Peng G. Robo2—slit and Dcc—netrin1 coordinate neuron axonal pathfinding within the embryonic axon tracts. J Neurosci. 2012;32:12589–12602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6518-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A, Hoops D, Labelle-Dumais C, Prevost M, Rajabi H, , Kolb B, et al. Netrin-1 receptor-deficient mice show enhanced mesocortical dopamine transmission and blunted behavioural responses to amphetamine. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:3215–3228. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manitt C, Eng C, Pokinko M, Ryan RT, Torres-Berrio A, , Lopez JP, et al. dcc orchestrates the development of the prefrontal cortex during adolescence and is altered in psychiatric patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e338. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adasme T, Haeger P, Paula-Lima AC, Espinoza I, Casas-Alarcon MM, , Carrasco MA, et al. Involvement of ryanodine receptors in neurotrophin-induced hippocampal synaptic plasticity and spatial memory formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3029–3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013580108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabertrand F, Nelson MT, , Brayden JE. Ryanodine receptors, calcium signaling, and regulation of vascular tone in the cerebral parenchymal microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2013;20:307–316. doi: 10.1111/micc.12027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa K, Mizuno K, Kiyokage E, Shibasaki M, Toida K, , Ohkuma S. Dopamine D1 receptor signaling system regulates ryanodine receptor expression after intermittent exposure to methamphetamine in primary cultures of midbrain and cerebral cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 2011;118:773–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quezada-Calvillo R, Robayo-Torres CC, Ao Z, Hamaker BR, Quaroni A, , Brayer GD, et al. Luminal substrate "brake" on mucosal maltase-glucoamylase activity regulates total rate of starch digestion to glucose. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:32–43. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31804216fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Tanaka T, Sutin AR, Sanna S, Deiana B, , Lai S, et al. Genome-wide association scan of trait depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ino H. Immunohistochemical characterization of the orphan nuclear receptor ROR alpha in the mouse nervous system. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:311–323. doi: 10.1177/002215540405200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde R, , Strazielle C. Discrimination learning in Rora(sg) and Grid2(ho) mutant mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:472–474. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Kolassa IT, Ackermann S, Aerni A, Boesiger P, , Demougin P, et al. PKCalpha is genetically linked to memory capacity in healthy subjects and to risk for posttraumatic stress disorder in genocide survivors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8746–8751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200857109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Kimpel MW, Edenberg HJ, Bell RL, Strother WN, , McClintick JN, et al. Differential gene expression in the nucleus accumbens with ethanol self-administration in inbred alcohol-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:481–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melen E, Himes BE, Brehm JM, Boutaoui N, Klanderman BJ, , Sylvia JS, et al. Analyses of shared genetic factors between asthma and obesity in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:631–7 e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablensky A, Morar B, Wiltshire S, Carter K, Dragovic M, , Badcock JC, et al. Polymorphisms associated with normal memory variation also affect memory impairment in schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:410–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom TD, , Fatemi SH. The involvement of Reelin in neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2013;68:122–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baune BT, Konrad C, Suslow T, Domschke K, Birosova E, , Sehlmeyer C, et al. The Reelin (RELN) gene is associated with executive function in healthy individuals. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;94:446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Ognibene E, Romano E, Adriani W, , Keller F. Gene-environment interaction during early development in the heterozygous reeler mouse: clues for modelling of major neurobehavioral syndromes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasbi A, Fan T, Alijaniaram M, Nguyen T, Perreault ML, , O'Dowd BF, et al. Calcium signaling cascade links dopamine D1-D2 receptor heteromer to striatal BDNF production and neuronal growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21377–21382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903676106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler HR, Sherva R, Koesterer R, Almasy L, , Zhao H, et al. Genome-wide association study of opioid dependence: multiple associations mapped to calcium and potassium pathways. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;76:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marambaud P, Dreses-Werringloer U, , Vingtdeux V. Calcium signaling in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegen. 2009;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, , Bashir ZI. Long-term depression: multiple forms and implications for brain function. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selemon LD. A role for synaptic plasticity in the adolescent development of executive function. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e238. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Peineau S, Howland JG, , Wang YT. Long-term depression in the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:459–473. doi: 10.1038/nrn2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, , Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum SG, Yuan PX, Wang M, Vijayraghavan S, Bloom AK, , Davis DJ, et al. Protein kinase C overactivity impairs prefrontal cortical regulation of working memory. Science. 2004;306:882–884. doi: 10.1126/science.1100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattij T, , Vanderschuren LJ. The neuropharmacology of impulsive behaviour. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas-Meunier E, Fossier P, Baux G, , Amar M. Cholinergic modulation of the cortical neuronal network. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:17–29. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0999-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu-Villaca Y, Filgueiras CC, , Manhaes AC. Developmental aspects of the cholinergic system. Behav Brain Res. 2011;221:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui-Kimura I, Ohmura Y, Izumi T, Yamaguchi T, Yoshida T, , Yoshioka M. Endogenous acetylcholine modulates impulsive action via alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;641:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Vasilyev DV, Goncalves MB, Howell FV, Hobbs C, , Reisenberg M, et al. Loss of retrograde endocannabinoid signaling and reduced adult neurogenesis in diacylglycerol lipase knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2017–2024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5693-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiskerke J, Stoop N, Schetters D, Schoffelmeer AN, , Pattij T. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation mediates the opposing effects of amphetamine on impulsive action and impulsive choice. PloS One. 2011;6:e25856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete F, Perez-Ortiz JM, Manzanares J. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor-mediated regulation of impulsive-like behaviour in DBA/2 mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinu IR, Popa S, Bicu M, Mota E, , Mota M. The implication of CNR1 gene's polymorphisms in the modulation of endocannabinoid system effects. Rom J Intern Med. 2009;47:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell LC, Metrik J, McGeary J, Palmer RH, Francazio S, , Knopik VS. impulsivity, variation in the cannabinoid receptor (CNR1) and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) genes, and marijuana-related problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:867–878. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grano N, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Kouvonen A, Puttonen S, Vahtera J, , Elovainio M, et al. Association of impulsivity with sleep duration and insomnia in an employee population. Pers Indiv Differ. 2007;43:307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarleglio CM, Resuehr HE, , McMahon DG. Interactions of the serotonin and circadian systems: nature and nurture in rhythms and blues. Neuroscience. 2011;197:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth RD, Weick JP, Bradley KC, Luoma JI, Aravamudan B, , Klug JR, et al. D1 dopamine receptor activation of NFAT-mediated striatal gene expression. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:31–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.