Abstract

Research shows that young men who have sex with men (YMSM) engage in higher rates of health risk behaviors and experience higher rates of negative health outcomes than their peers. The purpose of this study is to determine if the effects of adversity on HIV risk are mediated by syndemics (co-occurring health problems). Participants were 470 ethnically diverse YMSM ages 18 to 24 recruited between 2005 and 2006 and surveyed every 6 months for 24 months. Regression analyses examined the impact of adversity on syndemics (emotional distress, substance use, and problematic alcohol use) and the effects of both adversity and syndemics on HIV risk behaviors over time. Gay-related discrimination and victimization—among other adversity variables—were significantly associated with syndemics and condomless sex (CS). Syndemics mediated the effects of adversity on CS in all models. Adverse events impact HIV risk taking among YMSM through syndemics. These findings suggest that prevention programs aimed at reducing adversity may reduce both the synergistic effect of multiple psychosocial health problems and HIV risk taking.

Keywords: Sexual minority health, Syndemics, HIV, Health disparities

Introduction

Extensive public health research has shown that men who have sex with men, especially young men who have sex with men (YMSM), engage in higher rates of health risk behaviors and experience higher rates of negative health outcomes than their heterosexual peers.1–3 An important feature of these disparities among MSM is that they are often co-occurring and operate in ways to suggest that they are mutually reinforcing, thereby creating a “syndemic.”4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) define a syndemic as “two or more afflictions, interacting synergistically, contributing to excess burden of disease in a population.”5 Several psychosocial health conditions have been evaluated as part of a syndemic among MSM, including, but not limited to intimate partner violence,6–8 sexual assault,6,7 history of arrest,8,9 substance use,6–8 and psychological distress.6,7

Syndemic conditions have been shown repeatedly to increase HIV risk and HIV infection in samples of YMSM and may be, in part, responsible for driving the epidemic in this population.6,7,10 Overall, YMSM accounted for over a quarter of new HIV infections in 2009.11 Among adolescents and young adults, male-to-male transmission increased from 61 % in 2006 to 71 % in 2009 while decreasing (heterosexual, IDU) or remaining stable (MSM IDUs) in other transmission categories. African-American YMSM continues to be disproportionately impacted by HIV with new infections increasing 48 % between 2006 and 2009. That HIV continues to increase at disproportionate rates for YMSM suggests the need to further understand the factors associated with condomless sex (CS) risk and resilience.

Syndemic conditions, which are produced at least in part through exposure to adverse conditions,12,13 have been shown to be associated with HIV risk and HIV infection among MSM.6,7,10 Sexual minority stress has been shown to significantly impact the physical and mental health of adults.14 Such adversity has also resulted in disproportionate rates of mental health issues, psychological distress, and substance use among sexual minority youth.2,15 In a recent review article, Mustanski provides strong support, citing decades of YMSM research, for considering how experiences of adversity impact HIV risk behaviors.16 For example, experiences of gay-related harassment, health-related concerns, stress (partner, school, and work related), and unstable housing (e.g., forced to move because of sexuality or having no regular place to stay) have been significantly associated with HIV risk behaviors and predictors (partner and health-related stress) of inconsistent condom use.17,18 Substance use and experiencing intimate partner violence have also been strongly associated with increased HIV risk behaviors.6,19 However, it is still unclear what forms of adverse experiences and contexts impact syndemic production and how these conditions impact HIV risk among populations of MSM. The purpose of this study is to empirically test the theory that the presence of co-occurring psychosocial health conditions mediates the impact of adversity on HIV risk behaviors. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that experiences of adversity are associated with HIV risk taking behaviors among young MSM, and that syndemics are the pathway upon which these associations occur.

Methods

To test the mediated pathway suggested by Syndemic theory, we used data from the Healthy Young Men’s (HYM) Study, a study that utilized a mixed methods approach to identify factors related to health risk behaviors among YMSM. Participants were recruited between February 2005 and January 2006 in Los Angeles, California and surveyed every 6 months for 24 months. This study utilizes data from baseline and waves 3 (month 12) and 5 (month 24). This study received approval from the committee on clinical investigations of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the institutional review board of the University of Pittsburgh. Methods for the HYM study have been described in detail elsewhere;20–22 however, those directly relevant to this analysis are discussed below.

Sampling and Recruitment

A total of 526 young men were recruited for the HYM study. Young men were eligible to participate in the study if they were (1) 18–24 years old; (2) self-identified as gay, bisexual, or questioning and/or reported having had sex with a male partner; (3) a resident of Los Angeles County and anticipated living in Los Angeles for at least 6 months; and (4) self-identified as Caucasian, African-American, or Latino of Mexican descent. The overall retention rate was 93 %.

Young MSM were recruited from public venues such as bars, cafes, parks, etc., using venue-day-time (VDT) sampling.23 Forty-seven venues were evaluated over a 3-month period to ensure adequate numbers of eligible young men accessed those venues, of which 36 venues were selected for recruitment. Young men who entered these venues on the day and time selected for VDT who appeared to be eligible for the study (i.e., appeared to be between the ages of 18 and 24) were asked to complete a brief eligibility screening interview offered in both English and Spanish. Eligible individuals were given a detailed description of the study. Informed consent and contact information were obtained from interested individuals. A total of 4,648 individuals were screened during 203 sampling events, 1,371 (30 %) of whom met study eligibility criteria and 938 (68 % of those eligible) expressed an interest in participating. Fifty-six percent of those who expressed an interest (N = 526) participated in the study.

Participants completed a 1- to 1.5-h assessment using either an audio computer-assisted survey instrument (ACASI) or an on-line testing format in a space convenient to the participant (ex. study office, local coffee shop, etc). Participants completed this survey at baseline, and 6, 12, 18, and 24 month follow ups for a total of five visits. Participants received $35 as compensation for each wave of assessment completion.

Measures

Sociodemographic Variables

Sociodemographic variables include age, race/ethnicity, educational status, and sexual identity and attraction taken from the baseline assessment.

Experiences of Adversity (IVs)

Independent variables taken from the baseline survey summarize a range of adverse conditions and events that are both retrospective (e.g., family violence) and current life events (e.g., stress) taken from baseline data. Composite variables, described in detail below, were created to encompass four different forms of adversity: social adversity (four items), victimization (four items), family adversity (three items), and adverse context (three items). All individual items were dichotomized (0 = adversity was not experienced, 1 = adversity was experienced) and averaged with higher mean scores reflecting higher levels of adversity (range for each adversity scale, 0 to 1).

Social Adversity

Homophobia: Eight questions about frequency of hearing denigrating comments about homosexuals while growing up (Cronbach’s α current study = 0.79, original study = 0.75),24 coded as “1” for participants with scores greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean.

Gay-related discrimination: Four questions about frequency of experiencing discrimination based on sexual orientation as an adult, coded as “1” for participant with scores greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean.

Identity rejection: The reaction of “person most influential in your life” to disclosure of identity on five-point scale from very accepting to rejecting, coded as “1” for participants who indicated the person was either “intolerant” or “rejecting.”

Racism/ethnic discrimination: Two questions about the frequency of victimization based on one’s race or ethnicity as an adult or while growing up, coded as “1” for participants with scores greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean.

Victimization

Gay-related victimization: Two questions about being physically victimized for being gay or being perceived as effeminate as an adult or while growing up, coded as “1” for participants indicating that such an event happened.

Unwanted sexual experience: Participants were asked “How much you wanted this to happen?” for each of five types of sexual acts (received or performed oral, insertive or receptive anal, or vaginal). Responses were coded as “1” for participants indicating they experienced any of the five unwanted acts.

Sexual assault: Coded as “1” for participants who answered affirmatively to a question regarding ever having “non-consensual or forced sex.”

Family Adversity

Negative family influence: Coded as “1” for participants who answered affirmatively to the question “Is there someone in your family that has been a negative influence on your life?”

Sexual abuse in the home: Coded as “1” for participants who answered affirmatively to the question “When you were growing up, did your parents or any other adults in your home ever sexually abuse any of the children in your home?”

Drug/alcohol problem in household growing up: Coded as “1” for participants who answered affirmatively to the question “When you were growing up, did anyone in your family have a drug or alcohol problem?”

Physical abuse: Coded as “1” for participants who answered affirmatively to a question regarding being hit by a parent or guardian when growing up.

Adverse Context

Poverty: Coded as “1” for participants who reported being “without light or heat because of financial difficulty” while growing up.

Homelessness: Coded as “1” for participants who answered affirmatively to the question “Have you ever lived on the streets?”

Stressful life events: Respondents completed a 43-item scale concerning potentially stressful life events in the last 3 months, ranging from family arguments to death of a loved one (Cronbach’s α = 0.76).25 For the present study, this scale was recoded as “1” for participants with composite score greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean.

Syndemic (Mediator)

The syndemic mediator was a count variable, ranging from 0 to 3, of the number of co-occurring psychosocial health outcomes endorsed by an individual at wave 3 (month 12) of data collection. The component variables were comprised of (1) Distress, coded “1” for current Centers for Epidemiological Studies Distress (CES-D) scale26 score of 16 or greater;26 (2) Illicit substance use, coded “1” for use of any illicit drug (except marijuana) in the past 3 months; and (3) Alcohol misuse, coded “1” for any binge drinking in the past 30 days, defined as consuming five or more drinks in a single evening.27

Condomless Sex (DV)

CS was defined as less than consistent condom use for either insertive or receptive anal sex in the past 3 months (no CS = 0, any CS = 1). The CS measure was taken from wave 5 data (month 24).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 18. Listwise deletion was used to handle missing data. YMSM who did not participate in all three waves relevant to this study (waves 1, 3, and 5) or who were missing data for the outcome variable were excluded from analysis, leaving a final analytic sample of 470 participants. First, we ran a logistic regression to look at the relationship between the syndemic variable and the sexual risk outcome variable to insure that the three psychosocial variable chosen were in fact working as a syndemic. A series of linear multiple regression analyses were run to examine the impact of the baseline adversity variables on syndemics at wave 3, while controlling for age, race, and syndemics at the previous wave. Similarly, a series of logistic regression analyses were run to look at the impact of these adversity variables on condomless sex at wave 5 after controlling for age, race, and CS at the previous wave. Additional models were run with the adversity variables divided into four different categories of adversity as follows: (1) social adversity, (2) victimization, (3) family adversity, and (4) adverse context. A final model was run with composites of all four types of adversity entered simultaneously. All models were run with tolerance statistics; all variance inflation factors were less than 1.40, suggesting no problems with multicollinearity. Socioeconomic status (highest education level of most educated parent) was not related to the outcome variables and was therefore omitted as a covariate from all models.

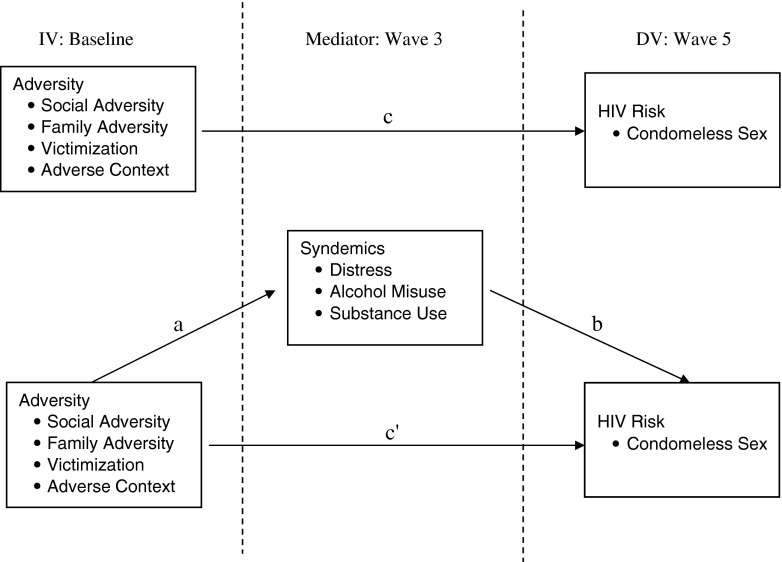

The primary goal of this study was to determine if the effects of adversity on HIV risk behaviors (CS) were mediated by syndemics. In order to assess mediation, several effects must be evaluated: (a) the effect of adversity on syndemics, (b) the effect of syndemics on CS, controlling for adversity, (c) the total effect of adversity on CS, and (d) the direct effect of adversity on CS controlling for syndemics (see Fig. 1). The indirect effect of adversity on CS through syndemics must also be evaluated in order to test for mediation. The indirect effect for all mediation models were tested using bootstrapping methods, as recommended by Preacher and Hayes.28,29 Bootstrapping is a nonparametric sampling procedure that is used to estimate the indirect effect of the predictor variable on the outcome variable through the mediator variable. Bootstrapping also allows the calculation of a confidence interval around the indirect effect in order to determine statistical significance. This method of testing mediation has advantages over more popular methods (e.g., the method of Baron and Kenny or the Sobel test) as it has greater statistical power and does not rely on the often faulty assumption of normality of the sampling distribution.28 Rather, the sampling distribution is tested empirically using the data from the original sample.30,31

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized mediated syndemic process. a The effect of adversity on syndemics. b The effect of syndemics on CS, controlling for adversity. c The total effect of adversity on CS. c’ the direct effect of adversity on CS controlling for syndemics.

Bootstrapping analyses were conducted using a publically available SPSS macro (http://www.comm.ohio-state.edu/ahayes/SPSS%20programs/indirect.htm) developed by Hayes.28 To test for mediation, a parameter estimate of the indirect effect (a x b, or the product of the regression coefficient from adversity to syndemics (a), and from syndemics to CS controlling for adversity (b); see Fig. 1) was generated by creating 5,000 random samples with replacement from the 470 participants in the original study. These 5,000 parameter estimates were also used to estimate a 95 % confidence interval so that the study hypothesis could be tested directly.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The average age of the sample is just over 20 years old (20.14; range 18 to 24; SD = 1.57) and the self-reported racial/ethnic identification of the sample was primarily Latino of Mexican descent (40 %) followed by white (36.8 %) and African-American (23.2 %). The majority of the sample identified as gay (74.9 %) and indicated that they were attracted to men only (70.6 %). Approximately, half of the sample (48.3 %) was currently in school at baseline.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics of young men who have sex with men (MSM) recruited into the Healthy Young Men’s (HYM) Study, Los Angeles, CA 2005–2006 (N = 470)

| Age, M (SD) | 20.14 (1.57) |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |

| African-American | 109 (23.2) |

| Mexican | 188 (40.0) |

| White | 173 (36.8) |

| Attraction, N (%) | |

| Men only | 332 (70.6) |

| Men and women | 129 (27.4) |

| Women only | 5 (1.1) |

| Sexual identity, N (%) | |

| Gay/MSM | 352 (74.9) |

| Bisexual | 77 (16.4) |

| Other | 41 (8.7) |

| Currently in school, N (%) | |

| Yes | 227 (48.3) |

| No | 243 (49.1) |

The mean syndemic count score was 0.963 (SD = 0.904). Approximately, one third of the sample reported each of alcohol misuse (32.6 %), distress (32.1 %), and illicit drug use (31.5 %). Sexual risk was predicted by the syndemic variable with each increase syndemic count predicting a 1.32 (p = 0.008) increase in odds of engagement in sexual risk. Table 2 presents the results of the associations between adversity variables and each of the three component syndemic conditions, controlling for age and race. All significant results were in the expected direction, suggesting that experiences of adversity at wave 1 were associated with greater odds of negative psychosocial outcomes at wave 3. Physical abuse, sexual abuse in the home, poverty, and identity rejection by the most influential person in one’s life were not significantly related to any of the psychosocial outcomes at a p < 0.05 level.

TABLE 2.

Association between adversity variables and psychosocial health outcomes among young men who have sex with men (MSM), Los Angeles, CA 2005–2006 (N = 470)

| Alcohol misuse | Distress | Substance use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | OR (95 % CI) | OR (95 % CI) | |

| Homophobia | 1.11 (0.669, 1.85) | 1.81* (1.10, 2.96) | 0.856 (0.500, 1.46) |

| Gay-related discrimination | 1.64* (1.00, 2.68) | 1.87* (1.15, 3.06) | 1.37 (0.826, 2.28) |

| Racial victimization | 2.53* (1.25, 5.13) | 0.855 (0.397, 1.84) | 1.39 (0.661, 2.93) |

| Gay-related victimization | 1.32 (0.840, 2.07) | 1.77* (1.13, 2.77) | 1.15 (0.723, 1.84) |

| Identity rejection | 1.73** (0.983, 3.04) | 0.983 (0.545, 1.77) | 1.13 (0.625, 2.04) |

| Unwanted sex | 0.868 (0.560, 1.34) | 1.75* (1.15, 2.66) | 1.01 (0.651, 1.57) |

| Sexual assault | 1.13 (0.712, 1.78) | 2.19*** (1.40, 3.41) | 1.71* (1.08, 2.69) |

| Negative family influence | 1.55* (1.05, 2.30) | 2.15*** (1.44, 3.19) | 1.23 (0.822, 1.83) |

| Victim of physical abuse | 1.13 (0.755, 1.68) | 1.28 (0.857, 1.92) | 1.12 (0.741, 1.68) |

| Sexual abuse (in home) | 0.984 (0.419, 1.97) | 1.61 (0.831, 3.12) | 1.14 (0.571, 2.28) |

| Family substance use | 0.990 (0.668, 1.47) | 1.84*** (1.24, 2.74) | 1.08 (0.719, 1.61) |

| Poverty | 1.47 (0.848, 2.56) | 1.36 (0.781, 2.37) | 1.52 (0.865, 2.68) |

| Lifetime homelessness | 0.742 (0.320, 1.72) | 3.20*** (1.51, 6.81) | 0.990 (0.435, 2.25) |

| Stressful life events | 1.45 (0.886, 2.37) | 3.54*** (2.18, 5.77) | 1.94*** (1.18, 3.18) |

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.10; ***p ≤ 0.01. OR odds ratios

A series of linear regressions that evaluated the effect of adverse events prior to or at baseline on the syndemic condition at wave 3, controlling for age and race, are presented in Table 3. All of the adversity variables were positively related to syndemic production, though only gay-related discrimination, gay-related victimization, sexual assault, the presence of a negative family influence, childhood poverty, and stressful life events were significantly related at a p < 0.05. Table 3 also presents the results of a series of logistic regressions evaluating the effect of these same adverse events on condomless sex reported at wave 5, also controlling for age and race. Notably, the syndemic variable was positively and significantly associated with CS with a 31 % increase in odds of engaging in condomless sex for each additional syndemic condition endorsed. Racial victimization, sexual assault, the presence of sexual abuse in the home, and family substance abuse were also significantly and positively related to CS.

TABLE 3.

Number and percent of participants endorsing each adverse event, as well as associations between adversity variables and (1) syndemic outcome and (2) condomless sex, controlling for age and race among young men who have sex with men (MSM), Los Angeles, CA 2005–2006 (N = 470)

| N (%) | Syndemic | CS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | (95 % CI) | OR | (95 % CI) | ||

| Syndemic | 1.31** | (1.06, 1.60) | |||

| Homophobia | 81 (17.2) | 0.130 | (−0.096, 0.356) | 1.42 | (0.876, 2.31) |

| Gay related discrimination | 81 (17.2) | 0.328** | (0.137, 0.584) | 1.35 | (0.832, 2.12) |

| Racial victimization | 35 (7.4) | 0.255 | (0.042, 0.689) | 2.78** | (1.33, 5.80) |

| Gay related victimization | 107 (22.8) | 0.222* | (0.046, 0.450) | 1.40 | (0.901, 2.15) |

| Identity rejection (Influential) | 59 (12.6) | 0.149 | (−0.073, 0.441) | 1.72*** | (0.982, 3.00) |

| Unwanted sex | 211 (44.9) | 0.100 | (−0.088, 0.290) | 0.797 | (0.528, 1.20) |

| Sexual assault | 133 (28.3) | 0.324** | (0.148, 0.549) | 1.99** | (1.28, 3.08) |

| Negative family influence | 209 (44.5) | 0.304** | (0.165, 0.504) | 1.02 | (0.707, 1.48) |

| Victim of physical abuse | 261 (55.5) | 0.136 | (−0.071, 0.274) | 0.790 | (0.542, 1.15) |

| Sexual abuse (In Home) | 40 (8.5) | 0.102 | (−0.153, 0.459) | 2.49** | (1.26, 4.92) |

| Family substance use | 227 (48.3) | 0.142*** | (−0.024, 0.321) | 1.62* | (1.12, 2.36) |

| Poverty | 64 (13.6) | 0.248* | (0.061, 0.559) | 1.02 | (0.592, 1.74) |

| Lifetime homelessness | 31 (6.6) | 0.222 | (−0.029, 0.659) | 1.28 | (0.606, 2.70) |

| Stressful life events | 85 (18.1) | 0.523** | (0.377, 0.808) | 1.03 | (0.636, 1.66) |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.10. CS condomless sex

The results of five multivariate models of syndemics and CS regressed on adversity are presented in Table 4. All four different forms of adversity—social, victimization, family, and context—significantly predicted syndemics. In each of these models, only one component adversity variable predicted syndemics above and beyond all other variables in the model (parameter estimates for significant variables are presented in the table). Three of the four different types of adversity also predicted condomless sex, with the exception being adverse context. The final model included each of the four different forms of adversity in a single model. This model significantly predicted syndemics (R2 = 0.071, p < 0.001) and CS (R2 = 0.059, p= 0.002). In the model predicting syndemics, adverse context remained significant after controlling for all other forms of adversity. In the model predicting CS, social adversity remained significant after controlling for the other forms of adversity.

TABLE 4.

Associations of adversity groups on syndemic and CS outcomes among young men who have sex with men (MSM), Los Angeles, CA 2005–2006 (N = 470)

| Syndemic | CS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95 % CI) | Adj. R 2 | OR (95 % CI) | Nagelkerke R 2 | |

| Model 1: social adversity | 0.030, p = 0.004 | 0.042, p = 0.029 | ||

| Homophobia | 0.068 (−0.159, 0.295) | 1.37 (0.82, 2.28) | ||

| Gay related discrimination | 0.317** (0.093, 0.540) | 1.26 (0.76, 2.10) | ||

| Identity rejection | 0.084 (−0.167, 0.335) | 1.57 (0.89, 2.78) | ||

| Model 2: victimization | 0.038, p = 0.001 | 0.067, p = 0.001 | ||

| Gay related victimization | 0.177 (−0.018, 0.372) | 1.18 (0.75, 1.85) | ||

| Unwanted sex | 0.038 (−0.143, 0.220) | 0.72 (0.47, 1.10) | ||

| Sexual assault | 0.287** (0.091, 0.483) | 1.93** (1.22, 3.05) | ||

| Racial victimization | 0.141 (−0.173, 0.455) | 2.36* (1.11, 5.04) | ||

| Model 3: family adversity | 0.042, p < 0.001 | 0.067, p = 0.002 | ||

| Negative family influence | 0.329** (0.152, 0.506) | 0.93 (0.62, 1.40) | ||

| Sexual abuse (in home) | −0.006 (−0.312, 0.300) | 2.52* (1.22, 5.19) | ||

| Victim of physical abuse | 0.017 (−0.157, 0.192) | 0.625* (0.416, 0.940) | ||

| Family substance use | 0.060 (−0.112, 0.231) | 1.68* (1.13, 2.51) | ||

| Model 4: adverse context | 0.059, p < 0.001 | 0.018, p = 0.406 | ||

| Poverty | 0.163 (−0.078, 0.403) | 0.98 (0.56, 1.70) | ||

| Lifetime homelessness | 0.012 (−0.331, 0.354) | 1.38 (0.63, 3.03) | ||

| Stressful life events | 0.507** (0.294, 0.720) | 0.99 (0.61, 1.62) | ||

| Model 5: total adversity | 0.071, p < 0.001 | 0.059, p = 0.002 | ||

| Social adversity | 0.335 (−0.055, 0.725) | 2.62* (1.04, 6.61) | ||

| Victimization | 0.219 (−0.199, 0.638) | 2.69 (0.99, 7.29) | ||

| Family adversity | 0.187 (−0.146, 0.520) | 1.19 (0.54, 2.60) | ||

| Adverse context | 0.663** (0.213, 1.11) | 0.56 (0.19, 1.65) | ||

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

The primary objective of this paper was to test the hypothesis that experiences of adversity increase the likelihood that an individual engages in condomless sex mediated by the presence of syndemics. The results of the meditational analyses that directly address this question are presented in Table 5. As previously demonstrated, pathway a (from adversity to syndemics) and pathway b (from syndemics to CS) were significant for all models. Pathway c, which represents the total effect of adversity on syndemics, was significant for victimization only. The direct effect (path c’) of adversity on CS controlling for syndemics was not significant for any of the models.

TABLE 5.

Summary of mediation results, controlling for age, race, and syndemics at previous wave among young men who have sex with men (MSM), Los Angeles, CA 2005–2006 (N = 470)

| a | b | c | c’ | Indirect effect (a x b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social adversity | 0.229* | 0.296* | 0.754 | 0.695 | 0.068 (−0.008, 213) |

| Victimization | 0.327* | 0.391* | 0.929* | 0.849 | 0.095* (0.001, 0.305) |

| Family adversity | 0.093* | 0.306* | 0.318 | 0.392 | 0.029 (−0.039, 137) |

| Adverse context | 0.338* | 0.313* | −0.052 | −0.162 | 0.106* (0.003, 0.310) |

| Total adversity | 0.480* | 0.291** | 1.09 | 0.960 | 0.140* (0.011, 0.390) |

All estimates provided are unstandardized regression coefficients. Path (a) the direct effect of adversity on Syndemics. Path (b) the direct effect of syndemics on HIV risk, controlling for adversity. Path (c) the total effect of adversity on HIV risk. Path (c’) the effect direct effect of adversity on HIV risk controlling for syndemics

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

The indirect effects (a x b), which directly test the mediated pathway in question, were significant at p < 0.05 for victimization and adverse context, but not for social adversity or family adversity. The indirect effect for the total adversity variable was also significant, indicating that adversity impacts CS through syndemics (a x b = 0.140, p < 0.05; 95 % CI 0.011, 0.390).

Several additional models were run to address the question of whether or not the mediation results could be driven by one or two of the component conditions rather than by a syndemic. First, bootstrapped models were run with each of the three psychosocial health conditions as individual mediators controlling for race and prior existence of that condition. The estimated coefficients and the 95 % confidence intervals of the indirect effects of those four models are as follows: substance use, B = 0.0011 (−0.0991, 0.1163); distress, B = 0.0839 (−0.1125, 0.3041); and alcohol misuse, B = 0.0551 (−0.0128, 0.2562). As evidenced by all confidence intervals overlapping zero, none of the models showed significant mediation for any of the component conditions alone. To further test the relative importance of each of the psychosocial outcome, three bootstrapped mediation models were tested, each with one of the syndemic conditions removed. The estimated coefficients and the 95 % confidence intervals of the indirect effects of the three models are as follows: substance use removed, B = 0.1855 (−0.0081, 0.5156); distress removed, B = 0.0275 (−0.0978, 0.2234); and alcohol misuse removed, B = 0.1243 (−0.0011, 0.3890). None of these models remained significant when components of the syndemic condition were removed, suggesting that the mediated pathway is intact only when all three conditions are in the model.

Discussion

Consistent with past literature,6,7,10 these findings show an increase in odds of HIV risk for each additional psychosocial condition endorsed by an individual, suggesting that co-occurring psychosocial health conditions may be contributing to HIV risk among young MSM. These findings also suggest that experiences of adversity play a key role in both syndemic development and HIV risk taking behaviors. Furthermore, these results indicate that syndemic conditions mediate the pathway from adversity to HIV risk taking behaviors. Thus, the impact of certain types of adversity on HIV risk may be obscured if syndemics are not taken into account.37 For example, the adverse context variable, which included poverty, lifetime homelessness, and stressful life events, did not by itself have a significant impact on condomless sex. However, when taking syndemics into account (defined as the co-occurrence of psychological distress, illicit substance use, and alcohol misuse), the indirect impact of this type of adversity significantly predicted CS with a higher estimated coefficient than any of the other types of adversity alone.

Despite these findings, there is reason to interpret these results with caution. Syndemics theory suggests that negative psychosocial health conditions have a tendency to intertwine and snowball making the impact of the syndemic condition more deleterious in terms of HIV outcomes than any single condition.6,7,10 However, to date, there is little information beyond the preliminary work presented here about how this process works. It is possible that certain conditions have a much greater negative impact than others, or that a certain pairing or set of conditions is necessary for there to truly be a syndemic. Additional analyses were conducted to rule out these possibilities, the results of which suggest that no single condition is driving the mediated effect of adversity on CS. Most importantly, the data used to conduct these analyses most likely does not capture the true complexity of syndemics, how they are produced or how they play out to impact HIV.

Beyond the inherent complexities of defining and testing syndemics, there are other limitations that should be noted. First, the data used for this study are based on self-report data and therefore may be subject to recall bias or social desirability factors. This may cause participants to underreport illicit or risky behaviors. However, sensitive information was collected using an ACASI program which has been shown to reduce self-report bias.32,33 Also, inclusion in this study required retention of an individual over 2 years. It may be that those who failed to return to subsequent visit are the highest risk individuals that are most likely to be wrapped up in syndemic processes; thus, because those individuals are not included in this analysis, the effect sizes may be underestimated.

Additionally, the sampling method used to identify potential participants, VTD, is not a true probability sample and may therefore impact generalizability to the wider young MSM population. However, the rigorous use of a quasi-probability sample such as VTD has been shown to yield far more representative samples than snowballing or other convenience approaches.34,35 Furthermore, the recall time points varied for many of the variables included in the analysis. This may have impacted the way each predictor influenced the outcome variables with the more proximal items driving the results. Finally, Syndemics theory, as it applies to MSM, has been used to address the relationship between co-occurring psychosocial conditions and HIV seroprevalence,7 or recently, seroincidence.10 Because this study did not include the collection of biological specimens, we relied on unprotected sex as a proxy for seropositivity. Although using risk behaviors as an outcome of syndemics is not unprecedented,6 it may not be the ideal way to model syndemic processes. However, condomless sex has been shown repeatedly to be an antecedent to HIV infections and therefore may be the best predictor of seropositivity, or the potential for future seropositivity, available for this and other behavioral studies.

Despite those limitations, this study has several notable strengths. First, this study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to test the mediated pathway proposed by Syndemics theory and the Theory of Syndemic Production.13 The relationship between early life adverse experiences and syndemic conditions has been tested previously with similar results,12 however, that analysis relied on retrospective data collected cross-sectionally and did not look at syndemics as a mediator of HIV sexual risk behaviors. Other strengths of this study are the racial and ethnic diversity of the sample, the longitudinal design with high retention levels, and the use of a rigorous, quasi-probability sampling design. In summary, results from this study support the arguments made by Syndemic theory that adverse life events impact HIV risk taking behaviors among young MSM through syndemics. Future work to develop HIV prevention programs aimed at reducing experiences of adversity faced by young MSM may help to reduce both the accumulation of psychosocial health problems and HIV risk-taking behaviors among young MSM.

Implications

The results of this study have important implications for the prevention of HIV and other health disparities among young MSM. Primarily, experiences of adversity may impact HIV risk-taking behaviors through syndemics as well as directly. Thus, previous research that has shown null relationships between adversity variables and HIV risk behaviors may be missing an important part of the picture. There were situations in this study where the relationship between the independent variable and HIV risk behaviors (path c) were nonsignificant. However, analysis of the indirect effect shows a significant relationship between these two variables. To illustrate this point take, for example, the relationship between adverse context and CS. The direct relationship between these variables is not statistically significant. This is because the direct effect of context adversity on CS is the sum of many different pathways of influence, such as personality traits, availability of condoms, and innumerable other factors that are not included in the model. If several of these factors influence the relationship in opposite ways, they may cancel out the direct effect.29 However, when alternative pathways are taken into account, such as the presence of a syndemic, the relationship between context adversity and CS becomes significant. Thus, previous studies that have found that there is no relationship between adversity variables and CS,36 or those relationships that gone unpublished due to null results, may be prematurely taking focus away from factors important to HIV prevention for YMSM.

The primary value in studying syndemic processes among young MSM is not only to understand how syndemics are formed and how they impact HIV risk, but also to identify innovative approaches to interventions that will positively impact the health of young MSM. This test of the mediating effects of syndemics suggests several avenues by which innovative health promotion interventions among MSM might be developed. First, it is important to note the varied and serious effects of adversity experienced by young people. While all the forms of adversity evaluated in this study are negative in and of themselves, the sequelae of these events may be direr. Results of this study suggest that abatement of adversity may impact the long-term health of MSM. Programs that target homophobia or gay-related discrimination at the level of the school or community, or national policy decisions that impact homelessness and poverty, may have a positive impact on downstream health outcomes.

The role of syndemics in mediating the pathway to HIV risk behaviors suggests a need to target co-occurring health outcomes in HIV prevention efforts. However, the results also suggest that removing distress, substance use, or alcohol misuse from the model mitigates the mediating effect of syndemics. This may imply that impacting any one of these conditions could have a positive impact on syndemic processes and HIV risk behavior. However, there is still much to be learned about how syndemics develop and play out to impact the health of MSM; therefore, further research is needed before interventions can be developed with confidence that will interrupt syndemic processes. For instance, it is important to note that less than 10 % of the sample reported none of the forms of adversity evaluated in this study, yet over a third of the sample (37.0 %) reported having none of the syndemic conditions. This suggests that many of the youth who experienced adversity, even those who experienced high levels of adversity, avoided distress, substance use, and alcohol misuse. Furthermore, of those who endorsed two or more psychosocial health conditions, only half (52.6 %) reported condomless sex. These results point to unmistakable resilience among this group of young men. Further research is needed to understand how youth who experience adversity avoid developing syndemics, and how those youth who develop syndemics avoid participation in HIV risk behaviors. Only when these processes are better understood are we likely to see the desperately needed reductions in health disparities among young men who have sex with men.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01 DA015638-03) and by the National Institute of Mental Health (1 F31 MH087238-01A1). We thank the HYM study team and the PITT Public Health Behavioral HIV team for their contribution to this study. Most importantly, we would sincerely like to thank the young men who have participated for their immense contribution to HIV research.

References

- 1.Herrick A, Marshal MP, Smith HA, Sucato G, Stall R: sex While intoxicated: a meta-analysis comparing heterosexual and sexual minority youth. J Adolesc Health. 2010, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health. 2011; 101(8): 1481–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC: http://www.cdc.gov/syndemics/. Retrieved July, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/syndemics/

- 6.Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:37–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02879919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:939–942. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon TM, Halkitis PN, Moeller RM, et al. Sex Parties among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in New York City: attendance and behavior. J Urban Health. 2011; 88(6); 1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kurtz SP. Arrest histories of high-risk gay and bisexual men in Miami: unexpected additional evidence for syndemic theory. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:513–521. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy K, Wimonsate W, Guadamuz T, et al. Syndemic analysis of co - occurring psychosocial health conditions and HIV infection in a cohort of men who have sex with men (MSM) in Bangkok, Thailand. Vienna: International AIDS Conference; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1481. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrick AL, Lim SH, Plankey MW, et al. Adversity and syndemic production among men participating in the multicenter AIDS cohort study: a life-course approach. Am J Public Health. 2013; 103(1): 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Stall R, Friedman M, Catania J: Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: a theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. In: Wolitski R, Stall R, Valdiserri R, editors. Unequal Opportunity: Health Disparities Affecting Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 251–274.

- 14.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurasaki KS, Okazaki S, Sue S. Asian American mental health: assessment theories and methods. New York, NY : Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002.

- 16.Mezzich JE, Caracci G. Cultural formulation: a reader for psychiatric diagnosis. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson; 2008.

- 17.Peterson DB. Psychological aspects of functioning, disability, and health. New York, NY: Springer Pub; 2011.

- 18.Puri BK. Saunders’ pocket essentials of psychiatry. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, UK: W.B. Saunders; 2000.

- 19.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. A model of sexual risk behaviors among young gay and bisexual men: longitudinal associations of mental health, substance abuse, sexual abuse, and the coming-out process. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:444–460. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Weiss G, et al. The health and health behaviors of young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kipke MD, Weiss G, Ramirez M, et al. Club drug use in Los Angeles among young men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:1723–1743. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong CF, Kipke MD, Weiss G, McDavitt B: The impact of recent stressful experiences on HIV-risk related behaviors. J Adolesc. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Muhib FB, Lin LS, Stueve A, et al. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:216. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: findings from 3 US cities. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nott K, Vedhara K, Power M. The role of social support in HIV infection. Psychol Med. 1995;25:971–983. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700037466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radloff LS. The Ces-D scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostrow DG, Monjan A, Joseph J, et al. HIV-related symptoms and psychological functioning in a cohort of homosexual men. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:737–742. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNall M, Remafedi G. Relationship of amphetamine and other substance use to unprotected intercourse among young men who have sex with men. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes A. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76:408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar Behav Res. 2004;39:99. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams J, Mackinnon DP. Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Struct Equ Model. 2008;15:23–51. doi: 10.1080/10705510701758166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kissinger P, Rice J, Farley T, et al. Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behavior research. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:950–954. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Tu X. Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muhib FB, Lin LS, Stueve A, et al. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:216. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stueve A, O’Donnell LN, Duran R, San Doval A, Blome J. Time-space sampling in minority communities: results with young Latino men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:922–926. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B: Moderators of the relationship between internalized homophobia and risky sexual behavior in men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2009:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed]