Abstract

BACKGROUND

Among the well described cytogenetic abnormalities in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a translocation involving chromosomes 1 and 19 (t[1;19] [q23;p13]) occurs in a small subset but has been associated variously with an intermediate prognosis or a bad prognosis in different studies.

METHODS

Adults with ALL and t(1;19) who were treated at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center were reviewed. Their clinical features and outcomes were compared with those of patients who had other cytogenetic abnormalities. The study endpoints included the complete remission (CR) rate, the complete response duration (CRD), and overall survival (OS).

RESULTS

Of 411 adults with pre-B-cell ALL, 12 patients had t(1;19). Ten of 12 patients with t(1;19) received hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine (hyper-CVAD) chemotherapy; and the other 2 patients received combined vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (VAD). All 12 patients achieved CR, and the 3-year survival rate was 73%. Patients with t(1;19) had significantly better CRD and OS compared with all other patients combined and compared individually with patients who had Philadelphia chromosome-positive, t(4;11), and lymphoma-like abnormalities (deletion 6q, addition q14q, t[11;14], and t[14;18]).

CONCLUSIONS

Adults with ALL and t(1;19) had an excellent prognosis when the received the hyper-CVAD regimen.

Keywords: cytogenetic subcategories, pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, translocation (1;19), hyper-CVAD

Chromosomal abnormalities in acute leukemia determine the disease pathophysiology and patient prognosis. Treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) results in high cure rates of 70% to 90%. Adults with ALL achieve high complete remission rates of 80% to 90%; however, cure rates are only 30% to 40%.1

A major difference between childhood and adult ALL is the frequency of various cytogenetic subcategories. A hyperdiploid karyotype, which is favorable, is observed in 30% of children compared with 2% to 5% of adults. Another favorable category is a translocation involving chromosomes 12 and 21, t(12;21), which results in the TEL-AML1 fusion gene.2 The latter is the most common molecular lesion in childhood ALL but is uncommon in adult ALL (range, 3%–4%).3,4 The t(9;22), or the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) (an unfavorable cytogenetic subset), is common in adult ALL (25%) but is rare in childhood ALL (<5%).5,6

One difficulty with elucidating the prognostic influence of certain cytogenetic abnormalities in ALL has been the rarity of the disease7 coupled with the low frequency of specific abnormalities. One recurring translocation in both children and adults is t(1;19)(q23;p13). It results in a fusion of the transcription factor 3 gene TCF3 (E2A) at 19p13 with the pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox gene PBX1 at 1q23, creating a TCF3-PBX1 fusion gene that encodes a protein with transforming properties. The E2A gene encodes 2 transcription factors, E12 and E47, which, in turn, bind to enhancer elements in the immunoglobulin κ or IGK gene and regulatory elements of other genes. PBX1 is a homeobox gene (HOX) on chromosome 1. E2A/PBX1 fusion messenger RNAs are formed and code for chimeric proteins that consist of the transcriptional activating domain of E12/E47 and DNA-binding domains of PBX1.8,9 The E2a/Pbx1 fusion protein may promote leukemogenesis by the transactivation of several genes normally not expressed in lymphoid tissues.10 The t(1;19) occurs in 2 forms: 1) a reciprocal translocation t(1;19)(q23;p13) or, more often, 2) an unbalanced form characterized by 2 normal chromosomes 1 and 19 and a rearranged chromosome 19, der(19)t(1,19)(q23;p13). In some studies, patients with the reciprocal translocation had a worse outcome.11 Children with t(1;19) who were treated on conventional antimetabolite-based therapy protocols had poor outcomes.12 Newer intensified regimens have improved prognosis, but patients with a balanced t(1;19) translocation still have an adverse prognosis.13 In the current study, we reviewed the outcome of adults with ALL and t(1;19) who received the hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine (hyper-CVAD) regimen.14

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Group and Therapy

Adults with newly diagnosed ALL who were referred to the Leukemia Department at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center from 1983 to 2007 were reviewed. In total, 411 adults had pre-B-cell ALL and were categorized into the following chromosome groups: t(1;19), normal (diploid), lymphoma-like, Ph-positive, t(4;11), and miscellaneous. The lymphoma-like group included patients with del(6q), add(14q), t(11;14), and t(14;18).

The miscellaneous group included patients with hyperdiploidy and patients with hypodiploidy. The majority of patients (80%) received the hyper-CVAD regimen, which consisted of fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and dexamethasone alternating with high doses of methotrexate and cytarabine.14 Adults who were referred before 1992 received the vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (VAD) regimen or the cytoxan plus VAD regimen.15

Statistical Analysis

The endpoints that we examined included complete response (CR), complete response duration (CRD), and overall survival (OS). A CR response required bone marrow with <5% blasts, a neutrophil count ≥1000/mL, and a platelet count ≥100,000/mL. Survival was estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method,16 and differences in survival curves were analyzed by using the log-rank test.17 Differences among variables were compared by using the chi-square test or Wilcoxon tests.

RESULTS

Study Group

In total, 411 adults with pre-B-cell ALL were identified. Their characteristics are listed according to cytogenetic subgroup in Table 1. Twelve patients had t(1;19), and they tended to be younger (median age, 30.5 years; range, 17–78 years). Their outcomes are detailed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Cytogenetic Groups

| Variable | Cytogenetic Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miscellaneous | Diploid | Lymphoma-Like | Ph+ | t(1;19) | t(4;11) | |

| No. of patients | 112 | 138 | 20 | 117 | 12 | 12 |

| Age | ||||||

| Median [range], y | 38 [15–78] | 37 [13–83] | 38 [18–70] | 50 [16–84] | 31 [17–78] | 40 [22–75] |

| No. aged >60 y (%) | 16 (14) | 20 (14) | 4 (20) | 31 (26) | 1 (8) | 2 (17) |

| WBC, ×109/L: No. (%) | ||||||

| <10 | 66 (59) | 90 (65) | 15 (75) | 48 (41) | 7 (58) | 3 (25) |

| 10–50 | 29 (26) | 30 (22) | 3 (15) | 44 (38) | 4 (33) | 2 (17) |

| >50 | 17 (15) | 18 (13) | 2 (10) | 25 (21) | 1 (8) | 7 (58) |

| Median hemoglobin [range], g/dL | 9.1 [4.0–15.2] | 8.6 [2.5–16.3] | 9.4 [4.8–13.8] | 9.0 [3.2–16.9] | 9.4 [7.5–11.7] | 9.0 [7.4–11.0] |

| Median platelet count [range], ×109/L | 57 [5–513] | 68 [8–402] | 70 [12–209] | 44 [4–449] | 36 [19–67] | 50 [22–102] |

| Median WBC [range], ×109/L | 6.9 [0.6–602.5] | 4.9 [0.2–196.5] | 5.9 [0.8–152.0] | 14.6 [0.8–344.5] | 8.0 [1.8–120.3] | 99.3 [1.4–316.5] |

| No. of men (%) | 58 (52) | 87 (63) | 14 (70) | 61 (52) | 9 (75) | 3 (25) |

| Performance status: No. (%) | ||||||

| 0–1 | 90 (80) | 109 (79) | 17 (85) | 94 (80) | 9 (75) | 11 (92) |

| ≥2 | 22 (20) | 29 (21) | 3 (15) | 23 (20) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) |

| No. of complete responses (%) | 100 (89) | 133 (96) | 16 (80) | 102 (87) | 12 (100) | 11 (92) |

Ph indicates Philadelphia chromosome; t, translocation; WBC, white blood cells.

Table 2.

Treatment and Results

| Patient | Age, y | Treatment Arm | Response | Remission Time, Weeks | Recurrence | Survival, Weeks | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | VAD | CR | 35 | Yes | 48 | Dead |

| 2 | 24 | VAD | CR | ≥547 | No | ≥550 | Alive |

| 3 | 78 | HCVAD | CR | 8 | No | 12 | Dead (CR) |

| 4 | 33 | HCVAD | CR | ≥623 | No | ≥625 | Alive |

| 5 | 59 | HCVAD | CR | 40 | Yes | 106 | Dead |

| 6 | 21 | HCVAD | CR | ≥404 | No | ≥407 | Alive |

| 7 | 28 | HCVAD | CR | ≥352 | No | ≥355 | Alive |

| 8 | 18 | HCVAD | CR | ≥308 | No | ≥312 | Alive |

| 9 | 28 | HCVAD | CR | ≥219 | No | ≥222 | Alive |

| 10 | 17 | HCVAD+rituximab | CR | ≥160 | No | ≥163 | Alive |

| 11 | 41 | HCVAD | CR | ≥117 | No | ≥120 | Alive |

| 12 | 39 | HCVAD | CR | ≥4 | No | ≥7 | Alive |

VAD indicates combined vincristine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and decadron; HCVAD, fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine; CR, complete remission.

Ten of 12 patients with t(1;19) received hyper-CVAD, and the other 2 patients received VAD. The average number of cycles of hyper-CVAD given was 7 (range, 3–9 cycles). All 12 patients achieved CR. The median remission duration was ≥189.5 weeks (range, from 4 weeks to ≥623 weeks). Nine of 12 patients remained alive and in CR at the time of the current report. Two patients (ages 48 years and 59 years) developed recurrent disease and died after 35 weeks and 40 weeks, respectively. The oldest patient (aged 78 years) died in CR from sepsis (Table 2). The karyotypes for each patient are listed in Table 3. Most patients had a complex karyotype, and 11 patients had a derivative (der) of chromosome 19, signifying an unbalanced translocation. The only patient who developed recurrent disease after treatment with hyper-CVAD was the 1 treated patient who did not carry a derivative of chromosome 19. The other patient who died from disease recurrence had received the VAD regimen.

Table 3.

Karyotype of the 12 Patients With Translocation (1;19)

| Karyotype |

|---|

| Patient 1 |

| [11] 49, XY,+ X, t(1;19)(q23;p13.3), der(9)t(1;9)(q23;q13), i(9)(q10),+13,+16, der(19)t(1;19)(q23;p13.3) |

| [11] 46, XY[11] |

| Patient 2 |

| [14] 60 XY,+ Y,+4,+5,+7, i(7)(q10),+8,+8,+10,+10,+14, +15,+16,+18, der(19)t(1;19)(q23;p13.3),+21,+21 |

| [11] Diploid |

| Patient 3 |

| [1] der(1;19) |

| [24] Diploid |

| Patient 4 |

| [20] 46XY, der(19)t(1;19)(q23;p13) |

| [5] 46XY |

| Patient 5 |

| [3] 36XY+1, t(1;19)(q21;q13.3), der(1;15)(q10;q10), t(5;15)(q33;q15) |

| [32] 46XY |

| [4] 45X, -Y |

| Patient 6 |

| [5] 46XY, der19t(1;19)(q23;p13) |

| [1] 42, i6(p10)−7,−17,−18, der19t(1;19),−22 |

| [16] 46XY |

| Patient 7 |

| [13] 46XY, t(1;9)(p10;p10), der19t(1;19)(q23;p13) |

| [7] 46XY |

| Patient 8 |

| [17] 53–58, XY,+ X,+4,+6,+10,+13,+14,+15,+17, +18, der19t(1;19)(q31;p15),+21,+22+0–6mar |

| [3] 46XY |

| Patient 9 |

| [18] 46XY, der19t(1;19)(q23;p13) |

| [1] 41, idem,+1,−9,−13,−16,−19,−20,−22 |

| [1] 46XY |

| Patient 10 |

| [3] Pseudodiploid clone 46, XY, der(19)t(1:19)(q23;p13) |

| [17] 46XY |

| Patient 11 |

| [8] Pseudodiploid clone 46, XX, add(7)p(15)der(9)t(9;22) (p13;q11.2)der(19)t(1;19)(q23:p13) |

| [8] 46XX |

| Patient 12 |

| [2] 47XX+ der(19)t(1;19)(q23;p13.3)[2] |

| [11] 46XX |

+ Indicates gain; t, translocation; q, long arm; p, short arm; der, unbalanced translocation; i, isochromosome; −, loss; mar, marker chromosome; idem, stemline karyotype; add, additional material of unknown origin.

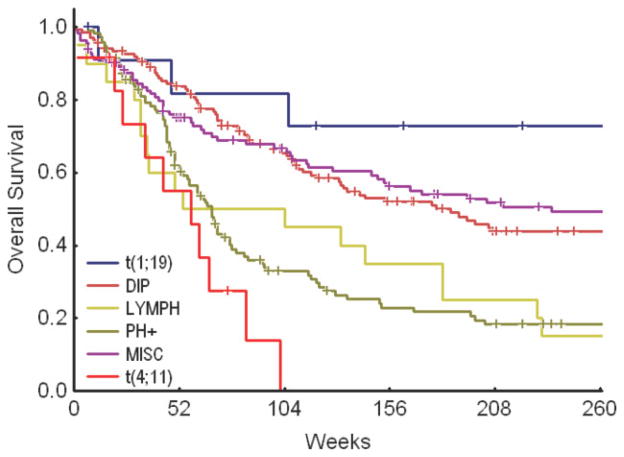

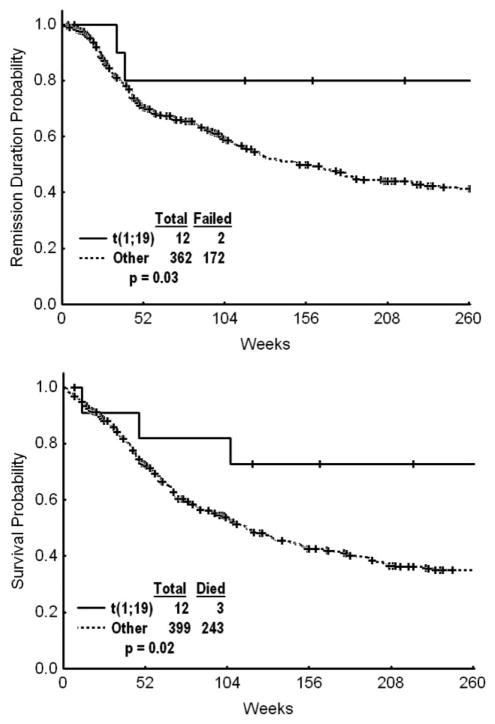

The estimated 3-year CRD and survival rates for the t(1;19) subgroup were 80% (Fig. 1) and 73%, respectively (Fig. 2). The t(1;19) group had significant improvement in CRD and OS when compared individually with the Ph-positive group, the t(4;11) group, and the lymphoma-like group (with del[6q], add[14q], t[11;14], and t[14;18]) (Table 4). The significant improvements in CRD and OS were maintained when patients with t(1;19) were compared with patients in all cytogenetic groups combined (Fig. 3, Table 5).

FIGURE 1.

Complete remission duration of patients with a translocation involving chromosomes 1 and 19 (t[1;19]) versus patients in other cytogenetic groups. DIP indicates diploid group; LYMPH, lymphoma-like group; PH+, Philadelphia chromosome-positive group; MISC, miscellaneous group.

FIGURE 2.

Overall survival of patients with a translocation involving chromosomes 1 and 19 (t[1;19]) versus patients in other cytogenetic groups. DIP indicates diploid group; LYMPH, lymphoma-like group; PH+, Philadelphia chromosome-positive group; MISC, miscellaneous group.

Table 4.

Outcome of Patients by Cytogenetic Group

| Cytogenetic Group | No. | No. of Failures | 3-year Survival, % | Median Survival, Weeks | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t(1;19) vs individual cytogenetic groups | |||||

| OS | |||||

| t(1,19) | 12 | 3 | 73 | NR | |

| Diploid | 138 | 72 | 52 | 179 | .09 |

| Lymphoma-like | 20 | 17 | 35 | 54 | .008 |

| Ph+ | 117 | 88 | 23 | 68 | .0002 |

| Miscellaneous | 112 | 56 | 56 | 236 | .17 |

| t(4,11) | 12 | 10 | 0 | 58 | .002 |

| CR duration | |||||

| t(1,19) | 12 | 2 | 80 | NR | |

| Diploid | 133 | 59 | 54 | 177 | .06 |

| Lymphoma-like | 16 | 13 | 34 | 89 | .009 |

| Ph+ | 102 | 52 | 42 | 63 | .006 |

| Miscellaneous | 100 | 41 | 59 | 401 | .16 |

| t(4,11) | 11 | 7 | NR | 45 | .018 |

t Indicates translocation; OS, overall survival; NR, not reported; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome positive; CR, complete response.

FIGURE 3.

(Top) Remission duration and (bottom) overall survival of patients with a translocation involving chromosomes 1 and 19 (t[1;19]) versus all other patient groups with pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. DIP indicates diploid group; LYMPH, lymphoma-like group; PH+, Philadelphia chromosome-positive group; MISC, miscellaneous group.

Table 5.

Response by Cytogenetic Group: The Translocation (1;19) Group Versus All Other Cytogenetic Groups Combined

| Cytogenetic Group | CR, % | Death During Induction, % | PR, % | Resistance, %* | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response, % | |||||

| t(1,19) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| All other groups | 91 | 3 | 1 | 5 | |

| Cytogenetic Group | No. | Failure | 3-Year Survival, % | Median Survival, wk | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | |||||

| t(1,19) | 12 | 3 | 73 | NR | .02 |

| All other groups | 399 | 206 | 42 | 116 | |

| CR duration | |||||

| t(1,19) | 12 | 2 | 80 | NR | .03 |

| All other groups | 362 | 172 | 50 | 151 | |

CR complete response; PR, partial response; t, translocation; failure, death in remission or relapse; OS, overall survival; NR, not reported

Resistance indicates no response to treatment.

DISCUSSION

The prognostic impact of t(1;19) in children and adults with ALL is controversial. Early data suggested that this translocation conferred a poor prognosis. Crist et al reported on 285 children with pre-B-cell ALL who were treated by the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) with induction therapy that included prednisone, vincristine, and L-asparaginase from 1986 to 1989. In that study, children with t(1;19) had significantly worse outcomes.18 In 1994, Pui et al reported the St. Jude data from 1979 to 1994 on 1101 children with newly diagnosed ALL.11 Forty-five children had either a balanced translocation (n = 10) or derivative translocation del (n = 30). The 5-year event-free survival rate in that study was 65% in children with del(19)t(1;19) and 41% in children with t(1;19) (P = .15).11 In the Children’s Cancer Group (CCG) studies from 1988 to 1994, 47 of 1322 children (3.6%) had t(1;19). The majority of children with t(1;19) were classified as poor-risk patients, whereas <50% of the B-lineage patients without this translocation were classified as poor-risk patients (P = .008). The 4-year event-free survival rate was 76% in patients with t(1;19) and 68% in the other B-lineage patients (P = .37). A significantly better outcome was noted in patients who had unbalanced translocations compared with balanced translocations (4-year event-free survival rate, 81% vs 42%; P = .003).13

Kager et al described the incidence and outcome of Austrian children using polymerase chain reaction analysis to identify the TCF-PBX1 transcript. They detected the fusion gene in 31 of 859 children with ALL (3.6%). Ten patients in their study had a balanced translocation, 10 children had an unbalanced translocation, and 5 children had both variants in 2 distinct clones. The 5-year event-free survival rate was 90%. The authors examined outcomes according to 4 sequential protocols that were used between 1986 and 2003 and reported that patients appeared to do better with higher dose intensity regimens.19 A similarly improved prognosis for patients with t(1;19) was reported with more intensive therapy by the POG in 2000.20 Recently, Schultz et al combined data from the POG and the CCG (now merged as the Children’s Oncology Group), and suggested that t(1;19) should not be included in the risk stratification algorithm.21

Similar data have been reported in adult ALL. In a French study from 1987 to 1992 of 443 adults with ALL, t(1;19) was present in 11 patients (3%), and those patients tended to be younger (median age, 22 years). All 11 patients in that study achieved a complete remission, but the median event-free survival was only 6 months, and the 3-year event-free survival rate was 20%.22 In a study by Secker-Walker et al (Medical Research Council [MRC] trials, 1985–1992), 10 of 850 adults (3%) had t(1;19), and 7 had unbalanced translocations. Their median disease-free survival was 36 months.23 More recently, Foa et al reported the experience of the Italian Study Group for Adult Hematologic Malignancies in adults with ALL and the E2A-PBX1 fusion protein. In that study, of 305 patients, 10 (3.3%) had t(1;19), and all had a pre-B-cell phenotype and were relatively young (median age, 22 years). The CR rate was 90%, and 4 patients remained alive in CR at the time of the report.24 In an MRC/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (MRC-ECOG) trial in 2007,25 t(1;19) was identified in 24 of 1522 patients (1.5%), and these patients had a 5-year OS rate of 32%. In other MRC-ECOG trials, there was no significant association between the translocation and prognosis.26–28 The ECOG trials listed above used an induction regimen of daunorubicin, vincristine, L-asparaginase, prednisone, and methotrexate followed by a second induction regimen of cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, 6 mercaptopurine, and methotrexate. The poorer prognosis reported in adult patients with t(1;19) in those studies may be attributed in part to the different induction regimens that were used.

The role of stem cell transplantation (SCT) in adult patients with ALL and t(1;19) was discussed by Vey et al. In their study, 24 adult patients with ALL and t(1;19) were given high-dose induction chemotherapy with prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and either daunorubicin or idarubicin. This was followed by intensive consolidation with high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantrone. Patients who achieved a CR were assigned to undergo either allogeneic SCT if a donor was available or autologous stem cell transplantation. Twenty-one of 24 patients (87%) achieved a CR after induction chemotherapy: Eight patients underwent allogeneic SCT, and 5 patients underwent autologous SCT. The overall 5-year disease-free survival rate was 39%. The patients who underwent allogeneic SCT had a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 63% compared with 16% in the autologous SCT arm and 0% in the maintenance chemotherapy arm, a finding that did not reach statistical significance. The 5-year OS rate for all 24 patients with t(1;19) was 54%. The authors argued that allogeneic SCT should be offered in first CR to patients with ALL and t(1;19) given their poor outcome with chemotherapy.29 The OS of adult patients with ALL and t(1;19) at our center who received the hyper-CVAD regimen compared favorably with the outcome of patients who underwent allogeneic transplantation.

The literature results suggested a better outcome for patients with t(1;19) who received higher dose intensity chemotherapy. Analysis of the prognostic significance of t(1;19) has been limited, because it is present in only 1% to 3% of patients with pre-B-cell ALL. In the pediatric population, it often is associated with other well known high-risk factors. However, there is a clear trend for improved prognosis of these patients over time with risk-adapted, intensive, multiagent chemotherapy. Hyper-CVAD uses dose-intensive therapy and originally was derived from childhood regimens that were designed to treat Burkitt leukemia. This may explain the favorable outcome of patients with t(1;19) who received hyper-CVAD.

In this study, adult patients with the t(1;19) abnormality had an excellent prognosis when they received the hyper-CVAD regimen. Comparing patients who carried t(1;19) and patients without this abnormality, the t(1;19) group had a significant improvement in CRD and OS. Given the rarity of patients with this cytogenetic aberration, only a multicenter trial would allow further demonstration of the apparent efficacy of this regimen.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors made no disclosures.

References

- 1.Larson RA, Dodge RK, Bloomfield CD, Schiffer CA. Treatment of biologically determined subsets of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: Cancer and Leukemia Group B studies. In: Buchner T, Hiddeman W, Wormann B, et al., editors. Acute Leukemias VI: Prognostic Factors and Treatment Strategies. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1997. pp. 677–686. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloomfield CD, Goldman AI, Alimena G, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities identify high-risk and low-risk patients with ALL. Blood. 1986;67:415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shurtleff SA, Buijs A, Behm FG, et al. TEL/AML1 fusion resulting from a cryptic t(12;21) is the most common genetic lesion in pediatric ALL and defines a subgroup of patients with excellent prognosis. Leukemia. 1995;9:1985–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLean TW, Ringold S, Neuberg D, et al. TEL/AML-1 dimerizes and is associated with a favorable outcome in childhood ALL. Blood. 1996;88:4252–4258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro RC, Abromowitch M, Raimondi SC, et al. Clinical and biologic hallmarks of the Philadelphia chromosome in childhood ALL. Blood. 1987;70:948–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wetzler M, Dodge RK, Mrozek K, et al. Prospective karyotype analysis in adult ALL: the Cancer and Leukemia Group B experience. Blood. 1999;93:3983–3993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNally RJQ, Roman E, Cartwright RA. Leukemias and lymphomas: time trends in the UK, 1984–93. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:35–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1008859730818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunger SP. Chromosomal translocations involving the E2A gene in ALL: clinical features and molecular pathogenesis. Blood. 1996;87:1211–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamps MP. E2A-Pbx1 induces growth, blocks differentiation, and interacts with other homeodomain proteins regulating normal differentiation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1997;220:25–43. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60479-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu X, McGrath S, Pasillas M, et al. EB-1, a tyrosine kinase signal transduction gene, is transcriptionally activated in the t(1;19) subset of pre-B ALL, which express oncoprotein E2a-Pbx1. Oncogene. 1999;18:4920–4929. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pui CH, Raimondi SC, Hancock ML, et al. Immunologic, cytogenetic, and clinical characterization of childhood ALL with the t(1;19) (q23;p13) or its derivative. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2601–2606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.12.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll AJ, Crist WM, Parmley RT, Roper M, Cooper MD, Finley WH. Pre-B cell leukemia associated with chromosome translocation 1;19. Blood. 1984;63:721–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uckun FM, Sensel MG, Sather HN, et al. Clinical significance of t(1;19) in childhood ALL in the context of contemporary therapies: a report from the Children’s Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:527–535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Smith TL, et al. Results of treatment with hyper-CVAD, a dose-intensive regimen, in adult ALL. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:547–561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantarjian HM, Walters RS, Keating MJ, et al. Results of the vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone regimen in adults with standard- and high-risk acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:994–1004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.6.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and 2 new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crist WM, Carroll AJ, Shuster JJ, et al. Poor prognosis of children with pre-B ALL is associated with the t(1;19) (q23;p13): a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Blood. 1990;76:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kager L, Lion T, Attarbaschi A, et al. Incidence and outcome of TCF3-PBX1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Austrian children. Haematologica. 2007;92:1561–1564. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maloney KW, Shuster JJ, Murphy S, Pullen J, Camitta BA. Long-term results of treatment studies for childhood ALL: Pediatric Oncology Group studies from 1986–1994. Leukemia. 2000;14:2276–2285. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schultz KR, Pullen DJ, Sather HN, et al. Risk- and response-based classification of childhood B-precursor ALL: a combined analysis of prognostic markers from the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) and Children’s Cancer Group (CCG) Blood. 2007;109:926–935. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-024729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique. Cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlations with hematologic findings and outcome. A collaborative study of the Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique. Blood. 1996;87:3135–3142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Secker-Walker LM, Berger R, Fenaux P, et al. Prognostic significance of the balanced t(1;19) and unbalanced dert(1;19) translocations in ALL. Leukemia. 1992;6:363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foa R, Vitale A, Mancini M, et al. E2A-PBX1 fusion in adult ALL: biological and clinical features. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:484–487. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult ALL: analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the MRC UKALL XII/ECOG 2993 trial. Blood. 2007;109:3189–3197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowe JM, Buck G, Burnett AK, et al. Induction therapy for adults with ALL: results of more than 1500 patients from the international ALL trial: MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2005;106:3760–3767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of ALL; an MRC UKALL 12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109:944–950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-018192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazarus HM, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Central nervous system involvement in ALL at diagnosis. Results from the International ALL trial MRC UKALL-XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2006;108:465–472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vey N, Thomas X, Picard C, et al. Allogeneic transplantation improves the outcome of adults with t(1;19)/E2A-PBX1 and t(4;11)/MLL-AF4 positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the prospective multicenter LALA-94 study. Leukemia. 2006;20:2155–2161. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]