Abstract

The type strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, PAO1, showed great upregulation of many nitrosative defense genes upon treatment with S-nitrosoglutathione, while the mucoid strain PAO578II showed no further upregulation above its constitutive upregulation of nor and fhp. NO· consumption however, showed that both strains mount functional, protein synthesis-dependent NO·-consumptive responses.

The prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) is thought to be due to derangements of salt concentrations in airway surface fluid, bacterial adhesion to airway epithelial cells, and nitric oxide (NO·)-mediated innate immunity (23). While these factors can be interrelated (5), decreased NO·-mediated innate immunity is clearly important (15). NO· is a potently bactericidal component of the innate immune system (3, 19) that acts either directly or via its ready conversion to other species, e.g., peroxynitrite and S-nitrosothiols. Microarray studies have demonstrated mucoidy-induced expression increases for genes whose products, such as nitric oxide reductase (nor) and flavohemoglobin (fhp), are involved in defense against NO· (7). Conversion to mucoidy in the CF-infected host increases general bacterial resistance to host clearance and antibiotics (11, 17), to which constitutive NO· defense by Nor and Fhp may contribute. To further characterize this NO· resistance, we induced nitrosative defense responses in the P. aeruginosa type strain, PAO1 (which is nonmucoid), and its mucoid derivative strain, PA0578II, by using S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO). GSNO is a physiologically relevant NO· donor that provides a nonvolatile carrier of NO· in the airway surface fluid of the lung (27) and whose levels are decreased in the lower airways in individuals with CF (12). These characteristics are thought to be important in the pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa in cases of CF (10). Gene expression was determined by microarray analysis as previously described (7). Furthermore, rates of in vivo NO· consumption were measured by a microelectrode technique.

Microarray analysis of nitrosative defense by GSNO.

GSNO (13) was added to cultures of PAO1 and its mucoid derivative, PAO578II (4, 8), for 30 min at a 5 mM final concentration, and then RNA extraction and analysis were performed as previously described (7). Strain PAO578II is a prototypical strain of mucoid isolates from individuals with CF: it carries both the mucA22 and sup-2 mutations (4, 8). The GSNO treatment caused growth arrest, but plate assays showed it not to be bactericidal (data not shown). The results from three microarray chips, i.e., independent identical experiments, were obtained for each strain (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Each value from each chip represents the average of 13 independent spots for each gene on each chip, providing further averaging. Ratios of gene expression levels in GSNO-treated bacteria to those in controls were calculated, and the 30 most upregulated, annotated genes (28) for each strain were selected (see the online annotation project at http://www.pseudomonas.com). All statistical analysis was done by t testing (with Microcal Origin software).

The P. aeruginosa mucoid strain PAO578II and the nonmucoid strain PAO1 were grown and treated with GSNO as described above. Total cellular RNA was isolated by using the AquaPure RNA isolation kit (Bio-Rad) and treated with DNA-free (Ambion) to remove any contaminating DNA. Reverse transcription was performed with a Retroscript kit (Ambion) per the manufacturer's protocol. The total cDNA was quantified by spectrophotometry, and exactly 50 ng was used in each real-time PCR. Real-time PCR was carried out in triplicate on an iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) by using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) with 50 ng of cDNA and a 500 nM concentration of each primer. Controls consisted of samples to which no cDNA template had been added or to which original RNA was added. Primers were designed for norB and fhp with Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The PCR primers for norB were CCAATGGCTCCCTGAAATTC and GCCCGACGAAGAGGATCA. The primers for fhp were TGCGCCGCAACTATTCG and TTGACGCTGATGCGGTATTC. Following PCR, relative expression levels were calculated by using 2ΔCT, where ΔCT represents the difference between cycling times (CT) for the two samples being compared. The CT is the point at which the PCR cycle crosses the preset logarithmic threshold.

Nonmucoid strain PAO1 strongly upregulates transcription of nitrosative defense genes upon GSNO treatment.

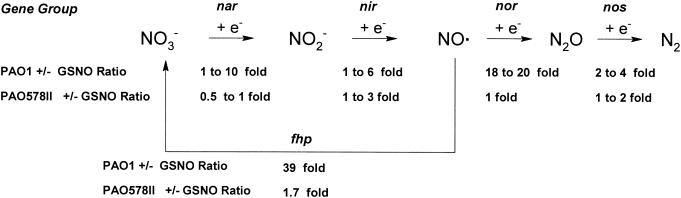

Of the 30 most upregulated genes (upregulated more than threefold, with a P value of <0.05), 12 are involved with metabolizing oxides of nitrogen and 2 have antioxidative functions (Table 1). The most highly upregulated gene, fhp, codes for flavohemoglobin, which oxidatively metabolizes NO· to NO3− by using O2 and NADPH (14) The genes norB and norC code for NO· reductase (Nor), which reductively metabolizes NO· to relatively inert N2O and thus can protect against nitrosative stress. This parallel induction of both nor and fhp is consistent with the physiological need to detoxify NO· as rapidly as possible. Nor, an integral inner membrane protein (32), is well placed to detoxify NO· as it enters bacterial cells, while cytosolic Fhp can act only once NO· has entered the cell. These capabilities can be viewed as providing nitrosative defense throughout the cell. To confirm the microarray analysis, real-time PCR was performed upon fhp and norB. In PAO1, upon GSNO treatment, the fhp and norB gene expression levels were 194- and 23-fold higher than those of the non-GSNO-treated controls, respectively (P < 0.00001). Other classes of genes involved in denitrification were also upregulated; their connections to the metabolic pathways are shown in Fig. 1. For example, moaB1 codes for the synthesis of the molybdopterin cofactor of nitrate reductase, and narK1 codes for a nitrate transporter (32). However, expression of adhC, glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase, which directly metabolizes GSNO and would be expected to be upregulated (16), was in fact not increased (0.8-fold increase; not significant).

TABLE 1.

Gene expression ratios for 30 most upregulated genes of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and corresponding genes of mucoid strain PAO578II under nitrosative stress with GSNO compared to controls

| Gene | Gene expression ratio (with GSNO stress/control)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | PAO578II | |

| PA2664 fhp | 38.7 (194) | 1.72 (0.54)b |

| PA3877 narK1 | 27.9 | 9.31 |

| PA3915 moaB1 | 22.9 | 25.4 |

| PA0525 norD | 19.6 | 0.87b |

| PA0523 norC | 18.4 | 0.76b |

| PA0524 norB | 18.4 (22.6) | 0.88 (1.2)b |

| PA1671 stk1 | 6.97 | 0.96b |

| PA4225 pchF | 5.79 | 6.62 |

| PA1778 cobA | 5.51 | 2.11b |

| PA0024 hemF | 4.32 | 1.80 |

| PA4235 bfrA | 4.09 | 4.30 |

| PA2532 tpx | 3.88 | 2.58 |

| PA3394 nosF | 3.86 | 1.10b |

| PA0291 oprE | 3.56 | 3.59 |

| PA3392 nosZ | 3.33 | 4.21 |

| PA3746 ffh | 3.19 | 4.01 |

| PA4260 rplB | 3.05 | 5.41 |

| PA3549 algJ | 3.04 | 0.24 |

| PA1077 flgB | 2.88 | 4.08 |

| PA4687 hitA | 2.82 | 1.52 |

| PA3989 holA | 2.77 | 4.87 |

| PA1796 folD | 2.74 | 2.91 |

| PA3396 nosL | 2.74 | 1.82 |

| PA3391 nosR | 2.69 | 1.19b |

| PA4267 rpsG | 2.67 | 4.47 |

| PA3393 nosD | 2.57 | 1.04b |

| PA5563 soj | 2.54 | 1.96 |

| PA3246 rluA | 2.50 | 1.83 |

All results are significant at a P value of <0.05 except where otherwise indicated. Confirmatory real-time PCR was performed with fhp and norB as detailed in the text. Values in parentheses represent gene expression ratios as determined by PCR.

Ratio indicates no significant difference in gene expression.

FIG. 1.

Correlation between denitrification reaction pathway and increases in gene expression resulting from nitrosative stress, based on microarray data (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

The mucoid strain PAO578II displays limited upregulation of nitrosative defense genes but upregulates pyochelin and other stress proteins.

The mucoid strain PAO578II exhibited a substantially different pattern of gene activation upon GSNO treatment, with a hallmark being little or no upregulation of the key nitrosative defense genes, nor and fhp, that are upregulated in PAO1 (Table 1). This finding was confirmed by real-time PCR analysis of fhp and norB. In the mucoid strain PAO578II, upon GSNO treatment the gene expression ratios for fhp and norB were increased 1.15-fold and decreased 1.9-fold, respectively, over those of the non-GSNO treated controls (P < 0.025). The fhp and nor genes are already greatly upregulated in mucoid cells; however, this is not the case for most of the other genes shown. The reason for this difference is unclear. The data showing little constitutive or GSNO-induced upregulation in mucoid strain PAO578II (compared to that in PAO1) of most genes (excluding nor and fhp) involved in denitrification are in contrast to the expectation that mucoid P. aeruginosa uses the denitrification pathway in respiration during mucoid colonization (30). One potential explanation, at least for the nir genes, is that Nir is proinflammatory due to increased epithelial-cell interleukin-8 production (18, 21). The lack of upregulation of nir is consistent with mucoidy-associated persistence in the lung and a decrease in the systemic virulence of most mucoid CF-associated isolates (31). The pattern of upregulated genes in PAO578II (Table 2) was quite different from that of the genes in PAO1. One category of genes showing significant increases in expression in GSNO-treated mucoid strain PAO578II was that of the damage control and repair genes bfr, groEL, grpE, grx, hslU, and ohr, which were upregulated 4.3-, 5.2-, 5.4-, 6.1-, 5.6-, and 13.7-fold, respectively. These damage control and repair genes were not significantly upregulated in PAO1. Although nor and fhp are constitutively upregulated upon conversion to mucoidy (and hence in PAO578II) (7), this upregulation appears insufficient to completely protect against nitrosative damage; hence, these repair mechanisms are induced. Another major class of genes upregulated by GSNO in PAO578II was that of the pch genes that are involved in synthesis of the siderophore pyochelin (22, 24), which were also upregulated in PAO1 (although only the upregulation of pchF reached significance at a P value of <0.05). In particular, pchA (whose product is a rate-limiting step in pyochelin synthesis in P. aeruginosa) (9) is strongly upregulated. Expression of the pyochelin receptor gene (fptA) (1) was also increased 4.6-fold (P < 0.05). It is as yet unclear, however, whether this upregulation of pchF resulted from the known disregulation of iron metabolism caused by nitrosative stress (6) or from a metabolic requirement for iron. Pyoverdin genes were not upregulated significantly in PAO578II or PAO1 by GSNO.

TABLE 2.

Gene expression ratios for 30 most upregulated genes of P. aeruginosa PAO578II and corresponding genes of mucoid strain PAO1 under nitrosative stress with GSNO compared to controls

| Gene | Gene expression ratio (with GSNO stress/control)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PAO578II | PAO1 | |

| PA3915 moaB1 | 25.4 | 22.9 |

| PA4231 pchA | 19.0 | 8.4b |

| PA2850 ohr | 13.7 | 6.3b |

| PA3407 hasAp | 12.2 | 7.2b |

| PA4228 pchD | 12.1 | 7.2b |

| PA4230 pchB | 11.3 | 4.6b |

| PA4229 pchC | 10.7 | 5.7b |

| PA0437 codA | 10.0 | 1.4b |

| PA3877 narK1 | 9.31 | 27.9 |

| PA4484 gatB | 9.09 | 1.5b |

| PA3299 fadD1 | 8.87 | 2.1b |

| PA2629 purB | 7.67 | 1.6b |

| PA1580 gltA | 6.71 | 1.8b |

| PA4226 pchE | 6.68 | 4.7b |

| PA4225 pchF | 6.63 | 5.79 |

| PA4266 fusA1 | 6.40 | 1.6b |

| PA5129 grx | 6.10 | 2.4b |

| PA5128 secB | 5.97 | 1.9b |

| PA4248 rplF | 5.69 | 1.9b |

| PA5054 hslU | 5.60 | 2.1b |

| PA4263 rplC | 5.59 | 2.0b |

| PA0963 aspS | 5.43 | 1.82 |

| PA4260 rplB | 5.41 | 2.7b |

| PA4762 grpE | 5.38 | 2.1b |

| PA4246 rpsE | 5.26 | 1.3b |

| PA4385 groEL | 5.19 | 1.7b |

| PA4258 rplV | 5.17 | 2.18 |

| PA0447 gcdH | 5.10 | 0.7b |

All results are significant at a P value of <0.05 except where otherwise indicated.

Ratio indicates no significant difference in gene expression.

Gene expression responses of conversion to mucoidy in PAO578II and of nitrosative defense in PAO1 are essentially independent.

A comparative study of the upregulation by nitrosative stress and mucoidy (shown for selected genes in Table 3) showed little cross-correlation between genes induced by mucoidy in PAO578II (7) and nitrosative stress. The control pathways involved in mucoidy and nitrosative defense appear to be essentially independent.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of gene expression ratios for P. aeruginosa PAO1 and mucoid strain PAO578II under nitrosative stress with GSNO with mucoidy-induced gene expression ratios determined previously for PAO578II

| Gene | Gene expression ratio (with GSNO stress/control)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | PAO578IIb | Mucoidy-induced PAO578IIc | |

| PA0059 osmC | 2.11b | 0.71 | 24 |

| PA0523 norC | 18.4 | 0.76 | 52 |

| PA0524 norB | 18.4 | 0.88 | 54 |

| PA0525 norD | 19.6 | 0.87 | 20 |

| PA0762 algU | 0.85b | 0.37 | 49 |

| PA0763 mucA | 1.57 | 0.58 | 21 |

| PA1249 aprA | 0.31b | 0.50 | 9 |

| PA1431 rsaL | 1.81b | 0.40 | 23 |

| PA2193 hcnA | 0.61b | 1.05 | 6 |

| PA2664 fhp | 38.7 | 1.72 | 61 |

| PA3540 algD | 1.71b | 0.52 | 7 |

| PA3724 lasB | 0.26b | 1.39 | 8 |

| PA4876 osmE | 1.89b | 0.68 | 49 |

All results are significant at a P value of <0.05 except where otherwise indicated.

Ratio(s) indicates no significant difference in gene expression.

Data are from reference 7.

Expression of adherence genes is downregulated by nitrosative stress in both PAO1 and PAO578II.

A recent study has shown that NO· decreases adherence between P. aeruginosa and airway epithelial cells (5). Upon the onset of nitrosative stress, the expression of several important adherence genes, including fliO (26), fliD (2), and several cupA and cupB genes (29), was significantly downregulated in both PAO1 and mucoid strain PAO578II (Table 4). This downregulation may explain the decreased adherence, and maximizing this effect may provide a useful treatment strategy for CF.

TABLE 4.

Gene expression ratios of potential adhesion-related genes in P. aeruginosa PAO1 and mucoid strain PAO578II under nitrosative stress with GSNO compared to control

| Gene | Gene expression ratio (with GSNO stress/control)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | PAO578II | |

| PA1445 fliO | 0.46 | 0.95b |

| PA2129 cupA2 | 1.35b | 0.39 |

| PA2132 cupA5 | 0.68b | 0.30 |

| PA4525 pilA | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| PA4082 cupB5 | 0.45b | 0.33 |

All results are significant at a P value of <0.05 except where otherwise indicated.

Ratio indicates no significant difference in gene expression.

In vivo NO· consumption analysis.

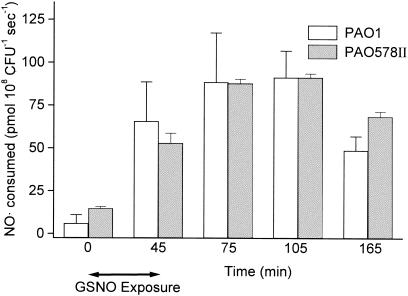

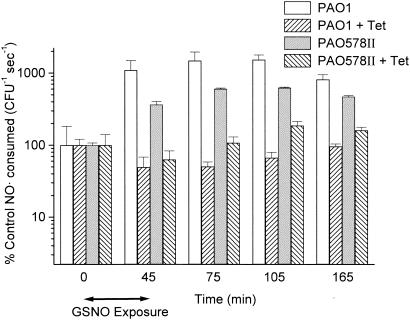

For the analysis of NO· consumption, 45 min of GSNO exposure was used (to allow protein expression from increased mRNA), followed by centrifugation and resuspension in fresh Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. NO· (final concentration, 50 μM) was added to 1 ml of stirred aerobic culture (3 × 108 CFU/ml) in a glass chamber at 37°C (20). The NO· concentration was measured with a daily calibrated inNO-T system (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Mass.). The baseline NO· consumption of mucoid strain PAO578II (14.6 ± 1.1 pmol 108 CFU−1 s−1) was significantly higher than that of nonmucoid strain PAO1 (5.8 ± 4.9 pmol 108 CFU−1 s−1), at a P value of <0.01, in accordance with its higher expression of nor and fhp genes. NO· consumption was substantially increased with GSNO treatment for both PAO1 and PAO578II (Fig. 2). This GSNO-induced increase in NO· consumption was inhibited in both strains by the protein synthesis inhibitor tetracycline (Fig. 3). We observed a 15-fold increase in NO· consumption in PAO1 (from 0 to 105 min) (Fig. 2), consistent with the microarray data for nor and fhp. For mucoid strain PAO578II, the induction of NO· consumption by GSNO that we observed was sixfold higher than that demonstrated by the microarray data for PAO578II, in which neither nor nor fhp genes were upregulated. This difference may be the result of induction of an NO·-consuming system other than Nor or Fhp or of a posttranscriptional regulation process that increases synthesis of Nor or Fhp in the absence of increased mRNA.

FIG. 2.

NO· consumption by P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PAO578II (in the presence of 0.3 M NaCl) measured with an NO· electrode after nitrosative stress; data shown are means + 1 standard deviation (n = 8). Nitrosative stress consisted of exposure to GSNO (initial concentration, 5 mM) for 0 to 45 min, after which the bacteria were centrifuged and resuspended in GSNO-free LB medium. Consumption rates for PAO1 (except at time zero) were all statistically significant compared to those of either the same strain at time zero or the other strain at the same time point at a P value of <0.01 (t test).

FIG. 3.

Effect of protein synthesis inhibition by tetracycline (50 μg/ml) on NO· consumption by P. aeruginosa PAO1 and mucoid strain PAO578II as measured with an NO· electrode after nitrosative stress; data shown are means + 1 standard deviation (n = 4). Nitrosative stress consisted of exposure to GSNO (initial concentration, 5 mM) for 0 to 45 min, after which the bacteria were centrifuged and resuspended in GSNO-free LB medium still containing tetracycline. Consumption rates were analyzed as percentages of the initial GSNO-free rate, and all data points for strains PAO1 and PAO578II with or without tetracycline (except at time zero) were statistically significant at a P value of <0.01 (t test).

These data could have implications for our understanding of P. aeruginosa pathogenesis in individuals with CF. For example, the limited effectiveness of clinical NO· or GNSO therapies for CF (25, 27) could derive in part from an induction of NO·-consuming, nitrosative defense systems, as demonstrated here. While this induction may explain the failure of these NO· and GSNO treatments, our studies with tetracycline suggest that combination therapy with a protein synthesis-inhibiting antibiotic could circumvent this problem. Additionally, characterization of NO· defenses of PAO1 and PAO578II at the protein level could provide an understanding of the nitrosative defense of clinically important mucoid strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI31139 (to V.D.) and by a microarray supplement (to V.D.) and a grant (to G.S.T.) from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Microarry instrumentation was supported by the Keck-UNM genomics core.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ankenbauer, R. G., and H. N. Quan. 1994. FptA, the Fe(III)-pyochelin receptor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a phenolate siderophore receptor homologous to hydroxamate siderophore receptors. J. Bacteriol. 176:307-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora, S. K., B. W. Ritchings, E. C. Almira, S. Lory, and R. Ramphal. 1998. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar cap protein, FliD, is responsible for mucin adhesion. Infect. Immun. 66:1000-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogdan, C., M. Rollinghoff, and A. Diefenbach. 2000. Reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen intermediates in innate and specific immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:64-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher, J. C., H. Yu, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1997. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect. Immun. 65:3838-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darling, K. E. A., and T. Evans. 2003. Effects of nitric oxide on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of epithelial cells from a human respiratory cell line derived from a patient with cystic fibrosis. Infect. Immun. 71:2341-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Autreaux, B., D. Touati, B. Bersch, J. M. Latour, and I. Michaud-Soret. 2002. Direct inhibition by nitric oxide of the transcriptional ferric uptake regulation protein via nitrosylation of the iron. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16619-16624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firoved, A. M., and V. Deretic. 2003. Microarray analysis of global gene expression in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 185:1071-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fyfe, J. A., and J. R. Govan. 1980. Alginate synthesis in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a chromosomal locus involved in control. J. Gen. Microbiol. 119:443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaille, C., C. Reimmann, and D. Haas. 2003. Isochorismate synthase (PchA), the first and rate-limiting enzyme in salicylate biosynthesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16893-16898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaston, B., F. Ratjen, J. W. Vaughan, N. R. Malhotra, R. G. Canady, A. H. Snyder, J. F. Hunt, S. Gaertig, and J. B. Goldberg. 2002. Nitrogen redox balance in the cystic fibrosis airway: effects of antipseudomonal therapy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165:387-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Govan, J. R. W., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grasemann, H., B. Gaston, K. Fang, K. Paul, and F. Ratjen. 1999. Decreased levels of nitrosothiols in the lower airways of patients with cystic fibrosis and normal pulmonary function. J. Pediatr. 135:770-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart, T. W. 1985. Some observations concerning the s-nitroso and s-phenylsulfonyl derivatives of l-cysteine and glutathione. Tetrahedron Lett. 26:2013-2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hausladen, A., A. J. Gow, and J. S. Stamler. 1998. Nitrosative stress: metabolic pathway involving the flavohemoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14100-14105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley, T. J., and M. L. Drumm. 1998. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression is reduced in cystic fibrosis murine and human airway epithelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 102:1200-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, L., A. Hausladen, M. Zeng, L. Que, J. Heitman, and J. S. Stamler. 2001. A metabolic enzyme for S-nitrosothiol conserved from bacteria to humans. Nature 410:490-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, M. H. Mudd, J. R. W. Govan, B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8377-8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori, N., K. Oishi, B. Sar, N. Mukaida, T. Nagatake, K. Matsushima, and N. Yamamoto. 1999. Essential role of transcription factor nuclear factor-κB in regulation of interleukin-8 gene expression by nitrite reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in respiratory epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:3872-3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Nathan, C., and M. U. Shiloh. 2000. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8841-8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Donnell, V., K. Taylor, S. Parthasarathy, H. Kuhn, V. DarleyUsmar, and B. Freeman. 1998. Turnover-dependent consumption of nitric oxide by 15-lipoxygenase: modulation of nitric oxide signalling and 15-lipoxygenase activity. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 25:172. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oishi, K., B. Sar, A. Wada, Y. Hidaka, S. Matsumoto, H. Amano, F. Sonoda, S. Kobayashi, T. Hirayama, T. Nagatake, and K. Matsushima. 1997. Nitrite reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces inflammatory cytokines in cultured respiratory cells. Infect. Immun. 65:2648-2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel, H. M., J. Tao, and C. T. Walsh. 2003. Epimerization of an l-cysteinyl to a d-cysteinyl residue during thiazoline ring formation in siderophore chain elongation by pyochelin synthetase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 42:10514-10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poschet, J., E. Perkett, and V. Deretic. 2002. Hyperacidification in cystic fibrosis: links with lung disease and new prospects for treatment. Trends Mol. Med. 8:512-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quadri, L. E., T. A. Keating, H. M. Patel, and C. T. Walsh. 1999. Assembly of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa nonribosomal peptide siderophore pyochelin: in vitro reconstitution of aryl-4,2-bisthiazoline synthetase activity from PchD, PchE, and PchF. Biochemistry 38:14941-14954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratjen, F., S. Gartig, H. G. Wiesemann, and H. Grasemann. 1999. Effect of inhaled nitric oxide on pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. Respir. Med. 93:579-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson, D. A., R. Ramphal, and S. Lory. 1995. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa fliO, a gene involved in flagellar biosynthesis and adherence. Infect. Immun. 63:2950-2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder, A. H., M. E. McPherson, J. F. Hunt, M. Johnson, J. S. Stamler, and B. Gaston. 2002. Acute effects of aerosolized S-nitrosoglutathione in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165:922-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallet, I., J. Olson, S. Lory, A. Lazdunski, and A. Filloux. 2001. The chaperone/usher pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of fimbrial gene clusters (cup) and their involvement in biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6911-6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon, S. S., R. F. Hennigan, G. M. Hilliard, U. A. Ochsner, K. Parvatiyar, M. C. Kamani, H. L. Allen, T. R. DeKievit, P. R. Gardner, U. Schwab, J. J. Rowe, B. H. Iglewski, T. R. McDermott, R. P. Mason, D. J. Wozniak, R. E. W. Hancock, M. R. Parsek, T. L. Noah, R. C. Boucher, and D. J. Hassett. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa anaerobic respiration in biofilms: relationships to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis. Devel. Cell 3:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu, H., J. C. Boucher, N. Hibler, and V. Deretic. 1996. Virulence properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lacking the extreme-stress sigma factor AlgU (σE). Infect. Immun. 64:2774-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zumft, W. G. 1997. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:533-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.