Abstract

Objective:

To present a series of 50 consecutive patients with non-metastatic extremity osteosarcoma, and attempt to correlate expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein in biopsy tissue to their prognosis regarding overall survival, disease-free survival and local recurrence.

Methods:

Fifty cases of non-metastatic osteosarcoma of the extremities treated between 1986 and 2006 at Instituto de Ortopedia e Traumatologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, were evaluated regarding expression of the VEGF protein. There were 19 females and 31 males. The mean age was 16 years old (range 5-28 years old) and the mean follow-up was 60.6 months (range 25-167 months). The variables studied were age, gender, anatomic location, type of surgery, surgical margins, tumor size, post chemotherapy necrosis, local recurrence, pulmonary metastasis and death.

Results:

Thirty-six patients showed VEGF expression on 30% or less cells (low), and the remaining 14 cases had VEGF expression above 30% (high). Among the 36 patients with low VEGF expression, nine developed pulmonary metastasis and four died (11.1%). Among the 14 patients with high VEGF expression, six developed pulmonary metastasis and three died (21.4%).

Conclusion:

There was no statistically significant correlation between the expression of VEGF and any of the variables studied. Level of Evidence IV, Therapeutic Study.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma; Prognosis; Neovascularization, pathologic

INTRODUCTION

Osteosarcoma treatment changed dramatically in the 80's with the use of multiagent chemotherapy. Before that, osteosarcoma patients were treated only with limb amputation, when feasible, and experienced a survival rate around 15% in 5 years. With the implementation of postoperative chemotherapy, authors realized that the survival time changed considerably. Stimulated by the brilliant results, preoperative chemotherapy was then suggested in order to try to preserve the affected limb.1 Lots of papers confirmed the excellent results of mutiagent chemotherapy, which usually included high-dose methotrexate and doxorubicin, and the 5-year survival rates jumped from 15% to around 70% in nonmetastatic patients. Surgery also developed considerably and limb-preserving surgeries, which were the exception before preoperative chemotherapy, became the rule. Amputation rates dropped from 100% to around 20%.

However, even with the huge advancements in surgical techniques, about 30% of the patients still develop metastatic disease and perish along the postoperative period. Efforts have been made in the last two decades in attempt to improve the osteosarcoma survival rate. Changes in the drugs, their number, their doses and administration schemes did not have impact on survival. Regarding chemotherapy, we are still in the same situation as 20 years ago.

With that situation in mind, other paths are being tried in order to advance in the osteosarcoma survival rates. One of most promising field is the research concerning angiogenesis. No solid tumor grows over 2mm without angiogenesis because cells must be within a certain distance of a capillary vessel in order to survive. Theoretically, if tumor angiogenesis could be suppressed, the tumor would not grow over 2mm and thus not metastasize and kill the patient.

One of the most potent angiogenic factors is the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). It is a dimeric glicoprotein of wieght around 36-46 kilodaltons (KDa), which acts promoting angiogenesis and vascular permeability.

VEGF levels been tested as prognostic factor in the most frequent cancers, such as breast, prostate, colorectal, lung, renal cell, glioblastoma and ovary. In 1999, Lee et al. 2 were the first to try to establish VEGF expression as a prognostic factor for survival in osteosarcoma patients.

Humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibodies, like bevacizumab (Avastin(r)), which was approved by the FDA in February 2004, or ranibizumab (Lucentis(r)), have proven their effectiveness in some cancers, but still not in osteosarcoma.

The objective of this study is to present a series of 50 consecutive nonmetastatic extremity osteosarcoma patients, and try to correlate the VEGF expression in their biopsy tissue to their prognosis regarding overall survival, disease-free survival and local recurrence.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (0016/2007).

All osteosarcoma patients treated at the University of São Paulo Medical School Hospital das Clínicas had their charts reviewed from 1986 to 2006.

Three inclusion criteria were defined:1) Primary high grade central osteosarcoma, located in the appendicular skeleton, nonmetastatic at diagnosis; 2) Minimum 24 months of follow-up; 3) Complete data, including biopsy paraffin embedded biopsy tissue.

Among the 195 patients with osteosarcoma treated in the period, 50 filled the above criteria. (Table 1) On these 50 charts, the following data was extracted: Register number: Name; Age at diagnosis; Gender; Anatomic location; Biopsy date; Surgery date; Type of surgery; Microscopic surgical margins; Tumor size; Post CT necrosis; Local recurrence; Distant metastasis; Follow-up period; Last oncologic status.

Table 1. Patients data.

| Case # | Age | Gender | Surgery | Final status | OS | DFS | Local recurrence | Metastasis | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | F | 05/05/89 | NED 26/08/2002 | 159 | 159 | - | - | - |

| 2 | 13 | M | 30/11/89 | DOD 20/04/1996 | 77 | 44 | 44 | 47 | 77 |

| 3 | 16 | M | 09/04/90 | AWD 09/03/1999 | 107 | 98 | 98 | - | - |

| 4 | 19 | M | 03/04/91 | DOD 03/10/1995 | 42 | 26 | - | 26 | 42 |

| 5 | 17 | M | 24/10/91 | DOD 08/02/1998 | 76 | 17 | 17 | 22 | 76 |

| 6 | 15 | F | 22/06/1992 | NED 05/05/2006 | 167 | 167 | - | - | - |

| 7 | 12 | M | 26/10/92 | NED 02/03/2004 | 137 | 137 | - | - | - |

| 8 | 24 | M | 21/06/93 | AWD 14/12/1995 | 30 | 23 | - | 23 | - |

| 9 | 18 | M | 27/03/95 | NED 13/01/1998 | 34 | 34 | - | - | - |

| 10 | 8 | F | 05/04/95 | DOD 07/10/2001 | 78 | 35 | - | 35 | 78 |

| 11 | 17 | M | 19/04/95 | AWD 30/04/1998 | 36 | 5 | - | 5 | - |

| 12 | 25 | F | 24/05/95 | AWD 09/12/1997 | 31 | 22 | 22 | 22 | - |

| 13 | 17 | M | 20/11/95 | DOD 03/12/1998 | 37 | 7 | - | 7 | 37 |

| 14 | 7 | F | 27/11/95 | AWD 12/04/2006 | 101 | 2 | 2 | 5 | - |

| 15 | 18 | M | 15/01/96 | NED 08/10/2008 | 105 | 105 | - | - | - |

| 16 | 14 | F | 14/02/96 | NED 02/03/1999 | 37 | 37 | - | - | - |

| 17 | 16 | F | 15/04/96 | AWD 18/05/2000 | 49 | 32 | - | 32 | - |

| 18 | 18 | F | 22/07/96 | NED 29/04/2003 | 81 | 81 | - | - | - |

| 19 | 5 | M | 07/05/97 | NED 20/04/2000 | 35 | 21 | 21 | - | - |

| 20 | 22 | M | 12/05/97 | DOD 10/10/2001 | 53 | 26 | - | 26 | 53 |

| 21 | 19 | F | 11/02/98 | NED 13/02/2007 | 108 | 108 | - | - | - |

| 22 | 22 | F | 10/06/98 | NED 17/09/2008 | 123 | 123 | - | - | - |

| 23 | 13 | F | 03/08/98 | NED 26/03/2002 | 43 | 43 | - | - | - |

| 24 | 24 | M | 02/09/98 | NED 23/09/2008 | 120 | 24 | 24 | - | - |

| 25 | 12 | M | 11/11/98 | NED 16/04/2008 | 113 | 113 | - | - | - |

| 26 | 28 | M | 01/12/99 | AWD 08/01/2008 | 97 | 46 | 62 | 46 | - |

| 27 | 12 | F | 27/09/01 | AWD 29/07/2008 | 82 | 25 | 25 | 59 | - |

| 28 | 17 | M | 16/09/02 | NED 21/05/2008 | 68 | 68 | - | - | - |

| 29 | 19 | M | 02/10/03 | NED 05/12/2007 | 50 | 50 | - | - | - |

| 30 | 15 | F | 24/11/03 | NED 10/04/2007 | 41 | 41 | - | - | - |

| 31 | 14 | M | 27/05/04 | AWD 20/05/2008 | 48 | 29 | - | 29 | - |

| 32 | 19 | M | 14/06/04 | NED 19/08/2008 | 50 | 50 | - | - | - |

| 33 | 19 | M | 06/07/04 | NED 15/07/2008 | 48 | 48 | - | - | - |

| 34 | 21 | M | 17/09/04 | DOD 30/11/2008 | 50 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 50 |

| 35 | 22 | F | 08/11/04 | NED 20/12/2008 | 49 | 49 | - | - | - |

| 36 | 24 | F | 18/11/04 | NED 07/11/2007 | 36 | 36 | - | - | - |

| 37 | 14 | F | 13/01/05 | NED 23/09/2008 | 44 | 44 | - | - | - |

| 38 | 13 | M | 04/04/05 | NED 24/07/2007 | 27 | 27 | - | - | - |

| 39 | 11 | F | 25/04/05 | NED 08/10/2008 | 42 | 42 | - | - | - |

| 40 | 14 | F | 05/05/05 | NED 11/09/2007 | 28 | 28 | - | - | - |

| 41 | 8 | M | 29/08/05 | NED 11/03/2008 | 31 | 31 | - | - | - |

| 42 | 13 | M | 03/10/05 | NED 15/07/2008 | 33 | 33 | - | - | - |

| 43 | 16 | M | 13/10/05 | NED 25/06/2008 | 32 | 32 | - | - | - |

| 44 | 15 | M | 26/01/06 | NED 13/08/2008 | 31 | 31 | - | - | - |

| 45 | 13 | M | 03/04/06 | NED 16/07/2008 | 27 | 27 | - | - | - |

| 46 | 16 | M | 15/05/06 | NED 16/06/2008 | 25 | 25 | - | - | - |

| 47 | 9 | M | 09/06/06 | NED 01/09/2008 | 27 | 27 | - | - | - |

| 48 | 16 | M | 13/07/06 | NED 01/09/2008 | 26 | 26 | - | - | - |

| 49 | 13 | F | 05/10/06 | NED 23/04/2009 | 30 | 30 | - | - | - |

| 50 | 10 | M | 09/10/06 | NED 23/02/2009 | 28 | 28 | - | - | - |

| Total: 50 | Av.:15,96 | 31M - 19F | - | - | Av.:60,6 | - | 10/50 (20%) | 15/50 (30%) | 7/50 (14%) |

OS: overall survival (months); DFS: disease-free survival (months); DOD: dead of disease; NED: no evidence of disease.

Age at diagnosis ranged from 5 to 28 years, averaging 15,96. Mean follow-up was 60,58 months (25-167).

Overall survival was 86%, disease-free survival was 70% and local recurrence rate was 20% in this study.

The remaining variables are described in the following table. (Table 2)

Table 2. Descriptive patients demographic data.

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 31 | 62% |

| Female | 19 | 38% |

| Anatomic Site | ||

| Upper limb | 8 | 18% |

| Lower Limb | 42 | 84% |

| Type of Surgery | ||

| Limb-sparing | 43 | 86% |

| Amputation | 7 | 14% |

| Microscopic surgical margin | ||

| Negative | 44 | 88% |

| Positive | 6 | 12% |

| Tumor size | ||

| < 8cm | 13 | 26% |

| > 8cm | 37 | 74% |

| Post chemotherapy (CT) necrosis | ||

| < 50% | 27 | 54% |

| > 50% | 17 | 34% |

| Do not apply | 6 | 12% |

| Local recurrence | ||

| No | 40 | 80% |

| Yes | 10 | 20% |

| Distant metastasis | ||

| No | 35 | 70% |

| Yes | 15 | 30% |

| Final oncologic status | ||

| No evidence of disease | 35 | 70% |

| Alive with disease | 9 | 18% |

| Dead of disease | 6 | 12% |

| Total | 50 | 100% |

Histologic analysis

Slides were studied by two separate pathologists with extensive experience in musculoskeletal oncology (CRGCMO and RZF).

Osteosarcoma diagnosis was confirmed by both pathologists through hematoxilin-eosin stained slides.

All analized tissue was obtained from biopsy or resection specimens, all neither submitted to chemotherapy nor radiation therapy. Each case was studied and classified by the two pathologists, in a blind fashion regarding patients identity and clinical condition.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Histologic sections (4µm thick) from paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens were submitted to the immunohistochemical study. The following antibody was used:

Anti-human mouse monoclonal antibody (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria CA, USA, clone VG1, isotype IgG1, kappa, VEGF isoforms 121, 165 e 189), with 1:100 dilution.

Specimens were submitted to antigenic recuperation using heat in a pressure cook. The above mentioned antibody was used in previously sylanized slides (3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane, Sigma Chemical CO, EUA, code A3 648) and left in 60°C for 24 hours, for better adhesion to the cuts. The method used was the streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase. DAKO StreptABComplex/HRP kit (estreptavidin-biotin-peroxidase) and LSAB were used in the detection reaction, as the following description:

Incubation with the primary antibody in the previously established dilution, in TBS, for an hour, at 37°C;

Washout in TBS and incubation for 5 minutes;

Incubation with the secondary antibody for 30 minutes at ambient temperature washout with TBS;

Incubation with estreptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex for 30 minutes at ambient temperature;

Washout and subsequent posterior incubação com TBS for 5 minutes;

Incubation with DAB substract (6mg of 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahidrochloride in 10ml of 0,05 M TBS, pH 7.6, and 0,1ml of 3% H2O2) for 5 minutes;

Distilled water washout;

Counter-coloration with Harrys hematoxilin;

Glicerinated jelly mounting.

Positivity of the reaction was seen by the brown color, seen in 200X optic microscopy, representing the antibody-antigen formed complex. The most representative field was selected (with the highest expression). The positive cells in the selected field were counted and their percentage over the total number of cells in that field was calculated. The average percentage of the two evaluations (two pathologists) was considered for statistical purposes.

VEGF expression was classified in two groups, according to the criteria used by Kaya et al.3:

Low VEGF expression (<30% of tumor cells), named Group 1;

High VEGF expression (>30% of tumor cells), named Group 2.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier curves regarding overall survival, disease-free survival and local recurrence were made. Low and high expression groups were compared used the log-rank test.

In order to assess the association between the variables and VEGF expression, Fisher's exact test was used.Significance level was established at 5%.

RESULTS

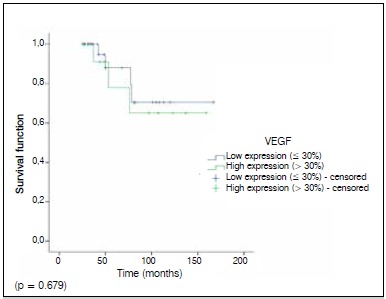

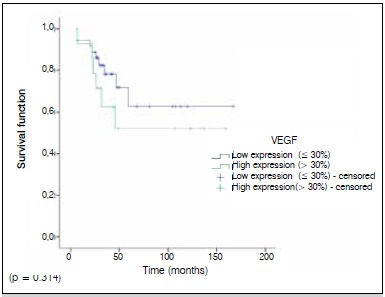

There was no difference in the overall survival between both groups (low and high VEGF expression). For both groups it ranged between 65 and 70% at final follow-up. Figure 1 depicts the Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for groups 1 (low VEGF expression) and 2 (high VEGF expression). There was also no difference in the recurrence-free survival: both groups had aproximately 80% at final follow-up. Figure 2

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for groups 1 (low VEGF expression) and 2 (high VEGF expression).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier local recurrence curves for groups 1 (low VEGF expression) and 2 (high VEGF expression).

shows the Kaplan-Meier local recurrence curves for groups 1 (low VEGF expression) and 2 (high VEGF expression). The disease-free survival in both groups was also statistically similar, as shown in Figure 3. None of the variables studied were significantly related to the VEGF expression. All results are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier disease free survival curves for groups 1 (low VEGF expression) and 2 (high VEGF expression).

Table 3 . Results.

| VEGF expression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 30% | > 30% | p | |

| Age | 0,056 | ||

| ≤ 20 | 32 | 9 | |

| > 20 | 4 | 5 | |

| Gender | 0,55 | ||

| Male | 22 | 9 | |

| Female | 14 | 5 | |

| Anatomical site | 0,14 | ||

| Upper limb | 4 | 4 | |

| Lower limb | 32 | 10 | |

| Type of surgery | 0,084 | ||

| Limb-sparing | 29 | 14 | |

| Amputation | 7 | 0 | |

| Surgical margin | 0,455 | ||

| Negative | 31 | 13 | |

| Positive | 5 | 1 | |

| Tumor size | 0,264 | ||

| ≤ 8cm | 8 | 5 | |

| > 8cm | 28 | 9 | |

| Post CT necrosis (6 patients (12%) did not receive preoperative CT) | 0,528 | ||

| ≤ 50% | 18 | 9 | |

| > 50% | 12 | 5 | |

| Local recurrence | 0,717 | ||

| No | 29 | 11 | |

| Yes | 7 | 3 | |

| Distant metastasis | 0,185 | ||

| No | 27 | 8 | |

| Yes | 9 | 6 | |

| Death | 0,384 | ||

| No | 32 | 11 | |

| Yes | 4 | 3 | |

DISCUSSION

Angiogenesis studies trying to correlate VEGF expression and osteosarcoma patients' survival rates are relatively recent. Lee et al.,2 in 1999, were the first to publish an association between high VEGF expression and bad prognosis for osteosarcoma patients. Since then, many other studies tried to establish a valid association.2 - 23 (Table 4)

Table 4. Literature review on VEGF expression in osteosarcoma biopsy tissue. Oncologic variables: local recurrence, overall survival and disease-free survival.

| Author and publication year | Sample | Local recurrence | Overall survival | Disease-free survival | Tissue | Correlation with bad prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. 2, 1999 | 30 | 20% (6) | 37% (11) | 30% (9) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Kaya et al. 3, 2000 | 27 | ND | 55% (15) | 44% (12) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Sulzbacher et al. 4, 2002 | 57 | 5% (3) | 77% (44) | 65% (37) | Biopsy | Negative |

| Jung et al. 5, 2005 | 25 | ND | 80% (20) | 68% (17) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Ek et al. 6, 2006 | 25 | ND | 84% (21) | 72% (18) | Biopsy | Negative |

| Ek et al. 7, 2006 | 11 | 0% (0) | 54% (6) | 45% (5) | Biopsy | Negative |

| Oda et al. 8, 2006 | 30 | ND | 27% (8) | 23% (7) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Mizobuchi et al. 9, 2008 | 48 | ND | ND | ND | Biopsy | Negative |

| Huang et al. 10, 2008 | 38 | ND | ND | ND | Biopsy | Positive |

| Bajpai et al. 11, 2009 | 31 | ND | ND | ND | Biopsy + Resection | Positive |

| Zhou et al. 12, 2009 | 65 | 26% (17) | 26% (17) | ND | Biopsy | Positive |

| Abdeen et al. 13, 2009 | 48 | ND | 71% (34) | 67% (32) | Biopsy + Resection + Metastasis | Negative |

| Marinho14, 2009 (DT) | 50 | ND | 50% (25) | 44% (22) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Rossi et al. 15, 2010 | 16 | 31% (5) | 69% (11) | 56% (9) | Biopsy + Resection | Positive |

| Lin et al. 16, 2011 | 56 | 20% (11) | 45% (25) | 45% (25) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Lugowska et al. 17, 2011 | 91 | ND | 73% (66) | 56% (51) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Qu et al. 18, 2012 (MA) | 387 | ND | ND | ND | Biopsy | Positive |

| Rastogi et al. 19, 2012 | 40 | ND | ND | ND | Serum + biopsy | Negative |

| Lammli et al. 20, 2012 | 54 | 17% (9) | ND | 59% (32) | Biopsy | Positive |

| Chen et al. 21, 2013 (SR) | 559 | ND | ND | ND | Biopsy | Positive |

| Becker et al. 22, 2013 | 27 | ND | 67% (8) | 40% (11) | Biopsy | Negative |

| Yu et al. 23 , 2014 (MA) | 323 | ND | ND | ND | Biopsy | Positive |

| Present study | 50 | 20%(10) | 86%(43) | 70% (35) | Biopsy | Negative |

ND = not described; DT = Doctorate thesis (unpublished); MA = meta-analysis; SR = Systematic review.

Regarding the local recurrence rate, we had ten cases (20%). Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the two groups did not obtain statistical significance between the VEGF expression and local recurrence (p=0.814). When analyzing by the Fisher's Exact test, we observed that among the ten locally recurred cases, three showed high VEGF expression (30%). In the other 40 patients that did not experience local recurrence, eleven showed high VEGF expression (27%) (p=0.717).

When comparing with the literature, we see that most of the similar studies do not even mention local recurrence as a variable.5 , 9 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 22 In the few studies that mention local recurrence, numbers obtained were similar to the present study. Lee et al. 2 and Lin et al. 16 reported the same 20% of local recurrence of the present series. Zhou et al.,12 presented 26% of local recurrence, and Rossi et al.,15 reported 31%. Only two studies reported unusually low recurrence rates: Sulzbacher et al.,4 with 5% (3/57), and Ek et al.,7 with no case in 11 patients.

When considering disease-free survival, the present series showed a 70% rate (35/50). As in our study only extremity cases were selected, all 10 locally recurrent cases were managed with amputation. Thus, no patient alive with disease had local recurrence: all had metastatic disease.

Kaplan-Meier curves of the two groups regarding disease-free survival did not show any difference regarding VEGF expression (p=0.314). However, when we compare the patients with metastasis with the disease-free patients, we observe a slight trend to metastatic patients present higher VEGF expression (p=0.185). All metastatic cases had pulmonary metastasis, being one case also with soft tissue metastasis. Four of the 15 patients with pulmonary metastasis were submitted to metastasectomies, one of them to three consecutive procedures.

The staining results of VEGF were classified into negative (<30%) or positive (>30%), the same criteria used by Kaya et al. 3 However, there is no consensus on which threshold to use. Huang et al.,10 Rossi et al.,15 Łudowska et al. 17 and Rastogi et al.,19 for instance, used 50% for the threshold value. Qu et al. 18 recommend 25% as a VEGF positive cutt-off value. Lammli et al. 20 used an even lower cut-off value of 20%.

Rastogi et al. 19 found a significant correlation between high serum VEGF and a high percentage of cells showing VEGF expression (p<0.001), when using 50% as a cut-off value. In the study, the patients who developed pulmonary metastasis had a higher baseline mean serum VEGF (p<0,001). The study failed, however, to show correlation between high VEGF serum values and all the others variables including overall survival and tumor staging.

The present study had a high disease-free survival of 70%, while in the literature it ranged from 23% to 72%. One explanation might be that we selected only patients with localized disease, and the majority of the studies with lower disease-free survival did not exclude the patients with metastasis at diagnosis.

Finally, our study showed 86% of overall survival. From the 50 initial cases, 15 developed distant metastasis (30%) and seven died of the disease (14%). We did not obtain statistically significant correlation between the VEGF expression in the biopsy tissue and the occurrence of death in the Kaplan-Meier curves analysis (p=0.679). When observing the Fisher's exact test, we detect a small trend to patinets that died had higher VEGF expression. But no statistical significance was obtained (p=0.384).

When comparing the present study with the literature, we see great variations in survival rates. Rates ranged from 26%12 to 84%.6 There are explanations, though, for this fact.

In the study from Zhou et al.,12 for instance, 28 of the 65 patients (43%) entered the study with metastatic disease. Oda et al. 8 included only patients with pulmonary metastasis, on the contrary to the present study, that selected only nonmetastatic cases. In the thesis from Marinho,14 22 of the 50 patients were metastatic at diagnosis. Ługowska et al.,17 who also selected only non-metastatic patients, also had a relatively high overall survival rate of 73%. These data should be taken in account when comparing the results of each study.

When we take only the studies that used biopsy tissue, we see that, among the 18 (excluding the two meta-analysis and the systematic review) studies, 12 show a positive correlation between high VEGF expression and poor prognosis, opposed to the other six studies. There was also one study that showed no correlation, but the VEGF was measured in the serum.19 The present study did not show significant correlation between the VEGF expression and poor prognosis. Therefore, we have 12 studies that propose a correlation between high VEGF expression and poor prognosis, and eight studies not correlating these variables.

Two meta-analysis18 , 23 and one systematic review21 confirmed the inverse association between the levels of VEGF and survival. The meta-analysis by Qu et al 18 found a positive association of elevated VEGF with the death of patients in the first five years after diagnosis (2.85-fold higher 5-year mortality). This meta-analysis also confirmed through univariate analysis that the higher stage of osteosarcoma, the patients from less developed areas, the lower percentage of osteoblastic histotype, the higher percentage of osteosarcoma located to femur and tibia and the more share of patients underwent neochemotherapy were risk factors of patients' survival. The percentage of VEGF expression, however, meant little. They stated that there is a small inverse relationship between VEGF expression level and the 5-year survival of osteosarcoma patients.

The meta-analysis by Yu et al.23 also found a inverse relationship between the levels of VEGF and prognosis. Interestingly, when grouped according to geographic settings of individual studies, the combined hazard ratio of Asian studies and non-Asian studies were 2.7 (95% CI: 1.35 - 3.39) and 1.51 (95% CI: 0.89-2.14), respectively, indicating that VEGF is an indicator of poor prognosis of osteosarcoma in Asian patients but not in non-Asian patients. This might be another reason for the present study not having reached a significant association between VEGF levels and prognosis, as our population is of non-Asian patients.

Although the present study is among a minority, a global view allows us to assume that VEGF expression seems to be a prognostic factor regarding survival in osteosarcoma patients.

CONCLUSION

VEGF expression in biopsy tissue was not a prognostic factor for nonmetastatic osteosarcoma of the extremities in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen G, Murphy ML, Huvos AG, Gutierrez M, Marcove RC. Chemotherapy, en bloc resection, and prosthetic bone replacement in the treatment of osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1976;37(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197601)37:1<1::aid-cncr2820370102>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee YH, Tokunaga T, Oshika Y, Suto R, Yanagisawa K, Tomisawa M, et al. Cell-retained isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are correlated with poor prognosis in osteosarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(7):1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaya M, Wada T, Akatsuka T, Kawaguchi S, Nagoya S, Shindoh M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in untreated osteosarcoma is predictive of pulmonary metastasis and poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(2):572–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulzbacher I, Birner P, Trieb K, Lang S, Chott A. Expression of osteopontin and vascular endothelial growth factor in benign and malignant bone tumors. Virchows Arch. 2002;441(4):345–349. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung ST, Moon ES, Seo HY, Kim JS, Kim GJ, Kim YK. Expression and significance of TGF-beta isoform and VEGF in osteosarcoma. Orthopedics. 2005;28(8):755–760. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20050801-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ek ET, Ojaimi J, Kitagawa Y, Choong PF. Does the degree of intratumoural microvessel density and VEGF expression have prognostic significance in osteosarcoma? Oncol Rep. 2006;16(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ek ET, Ojaimi J, Kitagawa Y, Choong PF. Outcome of patients with osteosarcoma over 40 years of age: is angiogenesis a marker of survival? Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006;3:7–7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oda Y, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, Matsuda S, Tanaka K, Yokoyama R, et al. CXCR4 and VEGF expression in the primary site and the metastatic site of human osteosarcoma: analysis within a group of patients, all of whom developed lung metastasis. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(5):738–745. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizobuchi H, García-Castellano JM, Philip S, Healey JH, Gorlick R. Hypoxia markers in human osteosarcoma: an exploratory study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(9):2052–2059. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Y, Lin Z, Zhuang J, Chen Y, Lin J. Prognostic significance of alpha V integrin and VEGF in osteosarcoma after chemotherapy. Onkologie. 2008;31(10):535–540. doi: 10.1159/000151685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajpai J, Sharma M, Sreenivas V, Kumar R, Gamnagatti S, Khan SA, et al. VEGF expression as a prognostic marker in osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(6):1035–1039. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Q, Zhu Y, Deng Z, Long H, Zhang S, Chen X. VEGF and EMMPRIN expression correlates with survival of patients with osteosarcoma. Surg Oncol. 2011;20(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdeen A, Chou AJ, Healey JH, Khanna C, Osborne TS, Hewitt SM, et al. Correlation between clinical outcome and growth factor pathway expression in osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 2009;115(22):5243–5250. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marinho LC. Estudo do fator de crescimento endotelial vascular e da densidade de microvasos em osteossarcomas humanos [tese] São Paulo: Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossi B, Schinzari G, Maccauro G, Scaramuzzo L, Signorelli D, Rosa MA, et al. Neoadjuvant multidrug chemotherapy including high-dose methotrexate modifies VEGF expression in osteosarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:34–34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin F, Zheng SE, Shen Z, Tang LN, Chen P, Sun YJ, et al. Relationships between levels of CXCR4 and VEGF and blood-borne metastasis and survival in patients with osteosarcoma. Med Oncol. 2011;28(2):649–653. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ługowska I, Woźniak W, Klepacka T, Michalak E, Szamotulska K. A prognostic evaluation of vascular endothelial growth factor in children and young adults with osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(1):63–68. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qu JT, Wang M, He HL, Tang Y, Ye XJ. The prognostic value of elevated vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with osteosarcoma: a meta-analysis and systemic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138(5):819–825. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rastogi S, Kumar R, Sankineani SR, Marimuthu K, Rijal L, Prakash S, et al. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor as a tumour marker in osteosarcoma: a prospective study. Int Orthop. 2012;36(11):2315–2321. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1663-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lammli J, Fan M, Rosenthal HG, Patni M, Rinehart E, Vergara G, et al. Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor correlates with the advance of clinical osteosarcoma. Int Orthop. 2012;36(11):2307–2313. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1629-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen D, Zhang YJ, Zhu KW, Wang WC. A systematic review of vascular endothelial growth factor expression as a biomarker of prognosis in patients with osteosarcoma. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(3):1895–1899. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0733-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker RG, Galia CR, Morini S, Viana CR. Immunohistochemical expression of VEGF and her-2 proteins in osteosarcoma biopsies. Acta Ortop Bras. 2013;21(4):233–238. doi: 10.1590/S1413-78522013000400010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu XW, Wu TY, Yi X, Ren WP, Zhou ZB, Sun YQ, et al. Prognostic significance of VEGF expression in osteosarcoma: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(1):155–160. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]