Abstract

The Dominant White locus (W) in the domestic cat demonstrates pleiotropic effects exhibiting complete penetrance for absence of coat pigmentation and incomplete penetrance for deafness and iris hypopigmentation. We performed linkage analysis using a pedigree segregating White to identify KIT (Chr. B1) as the feline W locus. Segregation and sequence analysis of the KIT gene in two pedigrees (P1 and P2) revealed the remarkable retrotransposition and evolution of a feline endogenous retrovirus (FERV1) as responsible for two distinct phenotypes of the W locus, Dominant White, and white spotting. A full-length (7125 bp) FERV1 element is associated with white spotting, whereas a FERV1 long terminal repeat (LTR) is associated with all Dominant White individuals. For purposes of statistical analysis, the alternatives of wild-type sequence, FERV1 element, and LTR-only define a triallelic marker. Taking into account pedigree relationships, deafness is genetically linked and associated with this marker; estimated P values for association are in the range of 0.007 to 0.10. The retrotransposition interrupts a DNAase I hypersensitive site in KIT intron 1 that is highly conserved across mammals and was previously demonstrated to regulate temporal and tissue-specific expression of KIT in murine hematopoietic and melanocytic cells. A large-population genetic survey of cats (n = 270), representing 30 cat breeds, supports our findings and demonstrates statistical significance of the FERV1 LTR and full-length element with Dominant White/blue iris (P < 0.0001) and white spotting (P < 0.0001), respectively.

Keywords: White, domestic cat, deaf, white spotting, retrotransposition, FERV1

The congenitally deaf white cat has long been of interest to biologists because of the unusual co-occurrence of a specific coat color, iris pigmentation, and deafness, attracting the attention of Charles Darwin, among others (Bamber 1933; Bergsma and Brown 1971; Darwin 1859; Wilson and Kane 1959; Wolff 1942). Multiple reports support the syndromic association of these phenotypes in the cat as the action of a single autosomal dominant locus, Dominant White (W), with pleiotropic effects exhibiting complete penetrance for suppression of pigmentation in the coat and incomplete penetrance for deafness and hypopigmentation of the iris (Bergsma and Brown 1971; Geigy et al. 2006; Whiting 1919).

This phenotypic co-occurrence of deafness and hypopigmentation has been observed in multiple mammalian species, including the mouse, dog, mink, horse, rat, Syrian hamster, human (Chabot et al. 1988; Clark et al. 2006; Flottorp and Foss 1979; Haase et al. 2007, 2009; Hilding et al. 1967; Hodgkinson et al. 1998; Hudson and Ruben 1962; Karlsson et al. 2007; Magdesian et al. 2009; Ruan et al. 2005; Tsujimura et al. 1991), and alpaca (B. Appleton, personal communication). In humans, the combination is observed in Waardenburg syndrome type 2 (W2), which exhibits distinctive hypopigmentation of skin and hair and is responsible for 5% of the cases of human congenital sensorineural deafness (Liu et al. 1995). Causal mutations for W2 have been characterized in six different genes (MITF, EDN3, EDNRB, PAX3, SOX10, and SNAI2) (Pingault et al. 2010), with most individuals exhibiting mutations in only one of them.

Pigment cells in all vertebrates, with the exception of pigmented retinal epithelia, are derived early in embryogenesis from the neural crest, from which they migrate as melanocyte precursors (melanoblasts), ultimately to differentiate into melanocytes and to reside in the skin, hair follicles, inner ear, and parts of the eye (White and Zon 2008). The eye is largely pigmented by melanocytes residing in the iris stroma (Imesch et al. 1997). Genetic defects impacting the proliferation, survival, migration, or distribution of melanoblasts from the neural crest are readily recognizable in coat hypopigmentation, and thus represent some of the earliest mapped genetic mutations (Silvers 1979). Research of white spotting loci in mice has been instrumental in understanding the molecular genetics underlying melanocyte biogenesis and migration, identifying many of the genes involved in critical early events in pigmentation, including Pax3, Mitf, Slug, Ednrb, Edn3, Sox10, and Kit (Attie et al. 1995; Baynash et al. 1994; Cable et al. 1994; Epstein et al. 1991; Herbarth et al. 1998; Hodgkinson et al. 1993; Sanchez-Martin et al. 2002; Southard-Smith et al. 1998; Syrris et al. 1999; Tachibana et al. 1992, 1994). The role that melanocytes play in hearing is both unique and critical. As the only cell type in the cochlea to express the KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) potassium channel protein, they facilitate K+ transport (Marcus et al. 2002), critical in establishing an endocochlear potential necessary for depolarization and auditory nerve electrical signal transduction.

The cat displays several distinctive white pigmentation phenotypes that have been under selection by cat fanciers (Vella et al. 1999): (1) Dominant White, with uniform white coat, often accompanied by blue irises and deafness; (2) white spotting (or piebald), with variable distribution of white areas on the body; and (3) gloving, with white pigmentation restricted to the paws. Albinism, the complete absence of pigment, is known to be caused by a distinct locus from White, called “C” (Whiting 1918). The C locus mutation implicated in albinism has been identified in the tyrosinase (TYR) gene, which codes for a critical enzyme in melanin synthesis (Imes et al. 2006). Albino cats have normal hearing; thus, pigment itself is not critical for the hearing process (Yin et al. 1990).

Whiting (1919) proposed an allelic series at the W locus controlling white pigmentation in the cat, where White is an extreme of piebald and dominant in the allelic series W (completely white) > wm (much spotted) > wl (little spotted) > w+ (wild-type). White spotting has been reported as linked to the KIT locus, and gloving has been reported as exhibiting a mutation in the KIT locus (Cooper et al. 2006; Lyons, 2010). We report here data implicating two previously unreported but related mutations in KIT as causative of feline Dominant White and white spotting, respectively.

Materials and Methods

Animals

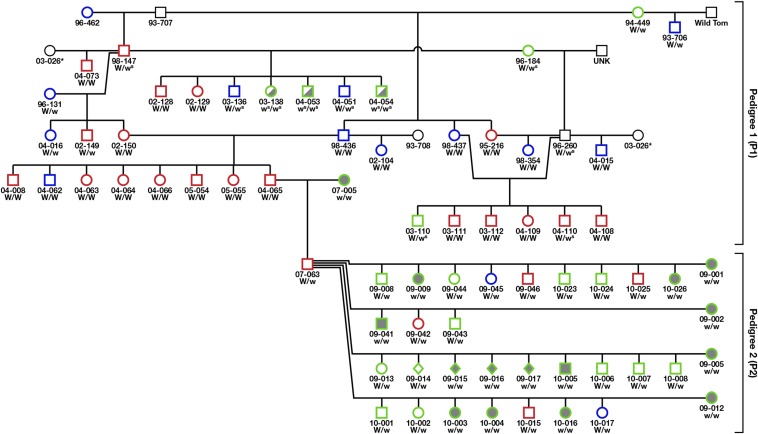

A domestic cat Dominant White pedigree was maintained for approximately 20 years at The Johns Hopkins University to research the physical basis of sensorineural deafness in these animals (Morgan et al. 1994; Saada et al. 1996; Ryugo et al. 2003, 1997, 1998) (Pedigree 1 in Figure 1). The white spotting phenotype was also observed at low frequency in more recent generations of the pedigree. Archival samples of genomic DNA from this pedigree were utilized in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Graphic depiction of JHU Pedigree. Pedigree 1 (PI) illustrates matings of white to white cats in the JHU archival colony. Pedigree 2 illustrates pedigree developed to map the W locus that is segregating for White coat color. Phenotype of individuals is indicated by color symbol and outline. White symbols denote individuals with a white coat; gray, fully pigmented individuals; half and half symbols (gray/white), white spotted individuals). Hearing capacity is indicated by color outline of the symbol: red outline, deaf; blue, partial hearing; green, normal hearing; black, unknown. Genotypes are depicted below symbol: W, White allele (W, insert of solo LTR; ws, White Spotting allele (insert of full-length FERV element); w, wild-type (no insertion).

A second pedigree (P2) segregating for White and sharing one individual with Pedigree 1 was generated at The Johns Hopkins University for mapping of the W locus (Figure 1). The progenitor of the pedigree, a white male (07-063), was generated to be heterozygous at W by mating a white, deaf male (04-065) with a fully pigmented (no white markings) female (07-005) (Liberty Laboratories) with normal hearing (Figure 1). The heterozygous (W/+) male was bred to four fully pigmented females (Liberty Laboratories) to produce 29 offspring, which included 10 pigmented and 19 white individuals. A small kindred from a pedigree of cats reported in an earlier study (Eizirik et al. 2003) was utilized to examine the segregation of white spotting. Genomic DNA from laboratory stocks of the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity was utilized in the study. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with guidelines established by the NIH and the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. When necessary, cats were humanely killed as previously described (Ryugo et al. 2003) and in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols approved at The Johns Hopkins University (#CA10M273).

Population sample of cat breeds

Genomic DNA extracted from whole blood or buccal swab samples from a previous study of cat breeds (Menotti-Raymond et al. 2007) was utilized in a population genetic survey of White and white spotting. The sample set of 270 individuals included 33 Dominant White cats, 94 cats exhibiting white spotting (i.e., either exhibiting white paws or bearing white on additional parts of the body), and 143 fully pigmented cats. The sample set represents individuals from 33 cat breeds, including 12 of 21 breeds that allow Dominant White and 16 of 22 breeds that allow white spotting in their breed standards (Cat Fanciers’ Association; http://www.cfa.org/client/breeds.aspx).

Phenotypes were provided by the owner or from direct observation by MM-R. All cats were assigned a registry (FCA) number, and phenotypic data were recorded in a database at the LGD to preserve the anonymity of individual cats and their owners.

Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood or tissue using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). DNA was quantified using the NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Marker development and genotyping

STR selection:

Primers were designed for amplification of short tandem repeat (STRs) loci selected from the domestic cat genome browser (GARField; http://lgd.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/cgi-bin/gbrowse/cat/) (Pontius and O’Brien 2007) that were tightly linked to eight candidate genes (Supporting Information, Table S1), whose orthologs had previously been implicated in a Dominant White phenotype or white-associated deafness.

Amplification and genotyping of STR loci:

PCR amplification was performed with a touchdown PCR protocol as described previously (Menotti-Raymond et al. 2005). PCR products were fluorescently labeled using a three-primer approach (Boutin-Ganache et al. 2001), and sample electrophoresis was performed as described previously (Ishida et al. 2006). Genotyping was performed using the software package Gene Marker (Soft Genetics, version 1.85). Inheritance patterns consistent with expectations of Mendelian inheritance were checked as described previously (Ishida et al. 2006).

Genetic linkage analysis

Genetic linkage analysis for W:

To identify the W locus, single-marker LOD scores were computed using SUPERLINK (Fishelson and Geiger 2002; Fishelson and Geiger 2004) (http://bioinfo.cs.technion.ac.il/superlink-online/). We modeled W as a fully penetrant, autosomal dominant trait with a disease allele frequency of 0.001. Marker allele frequencies were equal. A logarithm of odds (LOD) score was calculated for each of the markers (Table 1, Table S2).

Table 1. Linkage mapping of the domestic cat WHITE locus.

| Markera | LODb | θb | Position in Santa Cruz Browser (start, Chr.: Mb)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| KIT-A | 6.32 | 0 | B1:161.77 |

| KIT-B | 6.32 | 0 | B1:161.68 |

| KIT-C | 6.02 | 0 | B1:161.64 |

Markers are shown in genomic order along the domestic cat chromosome B1 on the basis of the most recent genetic linkage and radiation hybrid maps and cat genome assembly.

Logarithm of odds (LOD) score and recombination fraction (θ) for linkage between each polymorphic marker and the WHITE locus.

Position in the domestic cat whole genome sequence, UCSC browser, September 2011 (ICGSC Felis_catus 6.2/felcat5) Assembly.

Linkage and association testing for deafness:

In this analysis, the two pedigrees in Figure 1 were combined into one because they share an individual. To test whether the KIT FERV1 variation (see Results), encoded as a triallelic marker (W, ws, w+), is genetically linked to deafness, we also used SUPERLINK (Fishelson and Geiger 2002, 2004). Deaf (D) and partially hearing (PH) individuals were assigned the status “affected”, which by convention is encoded as 2. A range of frequencies (0.001 to 0.05) for the deafness-predisposing allele was tested. We started with an empirically derived penetrance function of 0.00, 0.25, and 0.75, and varied the second number in the range (0.15, 0.35) and the third number in the range (0.30, 0.80) to test the robustness of the LOD scores to misestimation of the parameter values.

To test for association between deafness and the KIT variants, we used MQLS (Thornton and McPeek 2007) because it tests for association while controlling for known pedigree relationships. MQLS requires as part of the input pairwise kinship coefficients and inbreeding coefficients. These coefficients were computed with PedHunter (Agarwala et al. 1998) after modifying the kinship and inbreeding programs of PedHunter to produce their output in the format required by MQLS. The MQLS program also requires as input a prevalence (of deafness), which we varied from 0.001 to 0.05 to test the robustness of the results. We used MQLS option 2, which ignores the individuals of unknown phenotype in estimating parameters. Combined linkage and association analysis was performed with PSEUDOMARKER (Hiekkalinna et al. 2011) with the empirical model.

Amplification and sequencing of KIT exons and 5′ region of intron 1

Primers for PCR amplification were designed in intronic regions flanking the 21 exons of KIT to include splice junction sites and also in the 5′ region of intron 1 using the GARfield cat genome browser (Table S3). The exons and the 5′ region of intron 1 of KIT were amplified using a touchdown procedure and sequenced as described previously (Table S5) (Ishida et al. 2006).

Amplification and genotyping assays developed for FERV1 LTR and full-length FERV1 element

FERV1 LTR (Dominant White) amplification:

Primers tagged with M13 tails were designed within genomic regions flanking the FERV1 LTR insertion site in KIT intron 1 (TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCACCCAGCGCGTTA (7FM13F); CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCCAAATCCTCCTCCTCCACCT (7RM13R). Fragments were amplified using a TaKaRa LA Taq kit (TaKaRa; CloneTech) using GC BufferII following the manufacturer’s suggestion. PCR conditions utilized were as follows: 94° for 1 min followed by 30 cycles of 94° for 1 min, and 57° for 2 min 30 sec, followed by an extension at 72° for 10 min. PCR reaction results were visualized for presence/absence of products by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and, to verify the presence of the FERV1 LTR insertion, by subsequent DNA sequence analysis of amplification products.

Full-length FERV1 (white spotting allele) amplification:

The full-length FERV1 insertion causative of white spotting was amplified using PCR primers designed within genomic regions flanking the FERV1 LTR insertion site in KIT intron 1. Primers were M13-tailed and designed to anneal at 65°: (KIT_65C_F_M13F): TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTATTTTGAGATCTGCAACACCCCTTC; (KIT_65C_R_M13R): CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCTCCTCCACCTTCAGACCTAAGTTCC. PCR conditions were as described above using TaKaRa LA, except that Buffer I and an annealing/extension temperature of 63° for 7 min were used. Individuals carrying the white spotting allele demonstrated a PCR product band in excess of 7 Kbp, as detected by gel electrophoresis.

Three-primer genotyping assay designed for White (FERV1 LTR), white spotting (full-length FERV1 element), and wild-type alleles:

A genotyping assay was developed to distinguish the wild-type, Dominant White, and white spotting alleles in a single PCR reaction. The reaction contained three primers, two in genomic regions flanking the full-length FERV1/FERV1 LTR element and a third located within the full-length FERV1 element. The primers and expected product sizes are presented in Table S7. PCR amplification was performed with TaKaRa LA as described above except that the annealing/extension temperature was 63° for 2.5 min using Buffer I. Products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel.

Identification of the LTR repeat type

After identifying an LTR in white cats, the cat genome (September 2011 ICGSC Felis_catus 6.2 assembly) (GenBank Assembly ID: GCA_000181335.2) was interrogated for sequences homologous to the LTR using BLAT (Kent 2002) at the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). There were 102 highly homologous sequences with BLAT scores >1000. The top hit was on chromosome D1-116687546.0.116694444, which demonstrated 98.4% identity over a span of 6333 bp. RepeatMasker (Smit et al. 2010) identified the repeat element as being part of an endogenous retrovirus (ERV) Class I repeat. The top hit was to ERV1-1_FCa-I (Anai et al. 2012; A.F.A. Smit, R. Hubley, and P. Green, unpublished data) (current version: open-4.0.0; RMLib: 20120418 & Dfam: 1.1).

Sequence analysis of full-length FERV1

To sequence the >7-kbp product, sequencing primers were designed from the previously published FERV1 sequence (Yuhki et al. 2008) (Table S6) and sequenced using standard ABI Big Dye sequencing with 99 cycles of amplification using the primers in Table S6 and the 65F and 65R primers.

RNA extraction and generation of cDNA

RNA was extracted from skin cells of white and pigmented cats using the RNAqueous-4 PCR kit (Ambion). Reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) to generate an amplified cDNA product. RT-PCR products were visualized on 2% agarose gels and sequenced as described above. The PCR primers used for amplification of the KIT cDNA are listed in Table S4. Complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences were aligned in Sequencher version 4.8 (Gene Codes Corp.).

Hearing threshold tests

Hearing thresholds were determined using standard auditory evoked brainstem response (ABR) techniques in a soundproofed chamber, as described previously (Ryugo et al. 2003). Each kitten was tested at 30 d and at 30-d intervals to track the animals’ hearing status over time. For 32 pigmented hearing cats and 44 white cats with varying degrees of hearing loss, repeated threshold measures for individuals varied less than 10 dB from month to month. The final ABR threshold measurements just before euthanasia for both ears were reported (Table S8) because this was the endpoint hearing status of the animals. All procedures were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by The Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) (Protocol #CA10M273).

Case-control analysis

For the population sample case-control analysis, the white cat phenotypes were dichotomized so that we could investigate the effect that each genotype had on the likelihood of a white cat phenotype. White cat phenotypes included coat color (colored, dominant white, or white spotted), blue iris color, and hearing capacity. The data were arranged in two-by-two tables (Table S11). The parameter of interest was the odds ratio measuring association between genotype and phenotype. Exact nonparametric inference was used to test the null hypothesis that the odds ratio equaled 1, i.e., no association between genotype and phenotype. The software used to perform these analyses was the FREQ procedure in SAS (SAS Institute, 2008). The Ragdoll breed was not included in the statistical analysis examining a potential correlation between blue iris and genotype at the W locus as all Ragdolls have blue eyes due to their genotype at the “C” or TYR locus, which results in decreased levels of the enzyme tyrosinase (Lyons et al. 2005b; Schmidt-Küntzel et al. 2005).

Hematopoietic and mast cell analysis

Hematopoietic profiles of two pigmented and two white deaf cats were generated by Antech Diagnostics (Table S11).

Tissues used in this study for mast cell analysis were collected after postmortem perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. To compare mast cell number and general histopathological differences between white (n = 2) and pigmented cats (n = 2), fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks, sectioned, mounted, and stained either with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stain for all tissues or toluene blue when appropriate for mast cell visualization (Histoserv, Inc.) (Table S11).

Results

The characterization of the feline White locus has been complicated by the lack of complete concordance of a white coat with blue irises and deafness (Geigy et al. 2006). Of the three phenotypes, only white coat color exhibits complete penetrance (Figure 1). Thus, we reasoned that mapping W using the segregation of white coat color would be a straightforward approach to identify the W locus in the domestic cat.

A candidate gene approach was utilized to map the W locus in the two-part pedigree described above. Significant linkage to W was established with three STRs tightly linked to the feline KIT locus on chromosome B1 (θ=0, LOD= 6.0–6.3) (Table 1). Negative LOD scores were observed for all STRs linked to the seven other candidate genes. For five of these candidate loci, LOD scores of −2 or less were observed, which are considered exclusionary (Ott 1991) (Table S2).

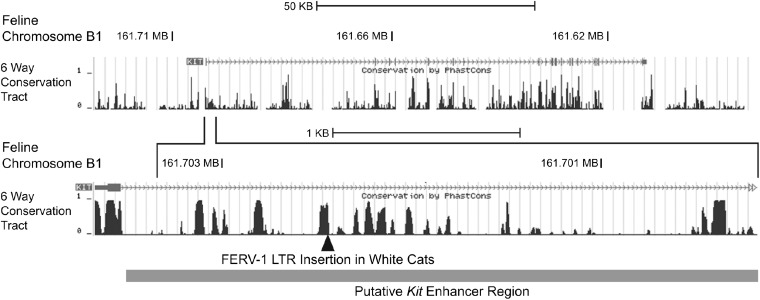

Sequence generated from the 21 exons of KIT and splice junction regions displayed no fixed polymorphisms that distinguished between white and nonwhite individuals. Additionally, sequence of cDNA generated from RNA isolated from skin exhibited no splicing abnormalities (Table S4). We next examined regions reported to impact regulation of KIT. Transcriptional regulation of KIT is highly complex and exhibits tissue specificity (Berrozpe et al. 2006; Mithraprabhu and Loveland 2009; Vandenbark et al. 1996). We identified a 623-bp insertion in KIT intron 1 interrupting the feline region homologous to the murine Kit DNase hypersensitive site 2 (HS2) (Figure 2), which is highly conserved across mammalian species and has been characterized in the mouse as having tissue and temporal-specific regulatory function in hematopoietic, melanocytic, and embryonic stem cells (Cairns et al. 2003; Cerisoli et al. 2009).

Figure 2.

Graphic depiction of feline Chromosome B1 (161.71 Mb-161.62 Mb) (UCSC Genome Browser, September 2011; ICGSC Felis_catus 6.2/felCat5) Assembly. Genomic region of KIT intron1 homologous to murine DNAse hypersensitive site 2 (1) requisite for high-level expression of Kit. Genomic conservation of the region is demonstrated across six mammalian species.

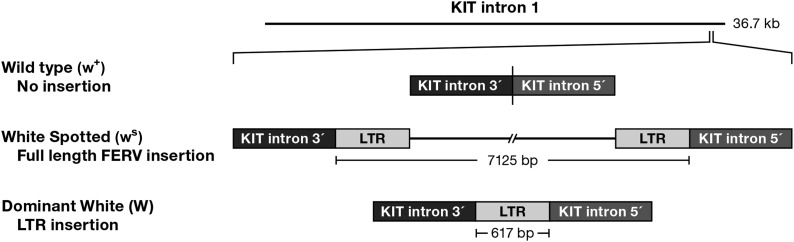

The insertion identified in intron 1 consisted of an element that demonstrated the highest level of identity to a feline endogenous retrovirus 1 (FERV1) family member recently identified in the cat genome, which exhibits similarity to a porcine endogenous retroviral family (Pontius et al. 2007; Yuhki et al. 2008). The inserted fragment comprised an incomplete viral sequence including the long terminal repeat (LTR) with a series of seven repeated sequence blocks 46-bp long. Figure S1 presents a sequence alignment of the feline KIT wild-type intron 1 with the LTR (henceforth the W allele), illustrating insertion breakpoints of the LTR element (GenBank id KC893343).

Primers designed in sequences flanking the W allele demonstrated that W segregated with white in Pedigree 2 (P2) (Figure 1) (P = 0.00014) and was observed in all white individuals of Pedigree 1 (P1) (Figure 1), with many of them demonstrating homozygosity for W (Table S8).

Three white spotted individuals in Pedigree 1 (03-138, 04-053, 04-054) (Figure 1) exhibited “null” alleles for a W genotyping assay, demonstrating neither the presence of the W allele nor the wild-type (w) allele (Figure 3). Analysis of short tandem repeat profiles (Menotti-Raymond et al. 1997) confirmed their parentage (data not shown). Because their parents appeared to be homozygous for the LTR insertion, these spotted individuals posed contradictions of both phenotypic and genotypic expectations. Ultimately, utilizing long-range PCR methodology, we generated a 7333-bp PCR product from the three white spotted individuals spanning the site of the W allele and identified a full-length 7125 bp feline endogenous retroviral sequence. The sequence exhibited highest similarity to the FERV1 element ERV1-1_FCa-I (Anai et al. 2012) on chromosome D1, demonstrating 98.4% identity over a span of 6333 bp (Figure S1) (GenBank submission no. KC893344). The full-length FERV1 insertion element demonstrated identical sequence identity to the LTR insertion of the W allele (Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Graphic depiction of retrotransposition of FERV full element and LTR into feline KIT intron 1 in White Spotted and White Dominant individuals; W, White allele; ws, White Spotted allele; w+, wild-type allele.

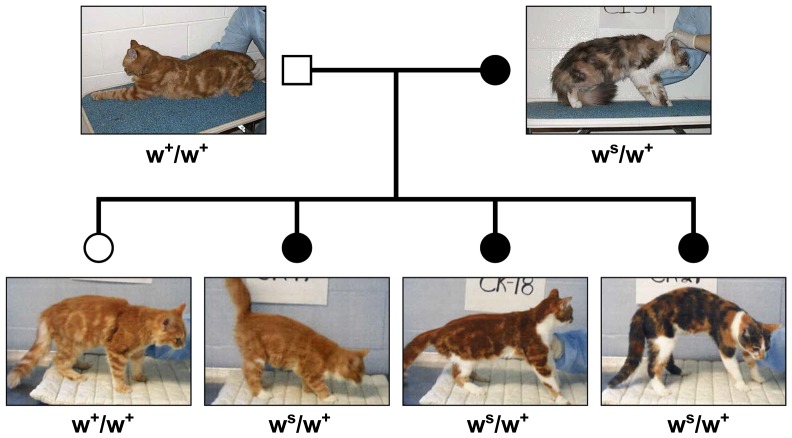

The full-length FERV1 element, henceforth white spotting allele, ws (Figure 3), demonstrated segregation with the white spotting phenotype (Figure 1), both in Pedigree 1 and an independent pedigree (Figure 4), as well as exhibiting recessiveness to the W allele, and dominance to the wild-type allele, White (W) > white spotting (ws) > wild-type (w+) (Table 2). Different degrees of white pigmentation were demonstrated by three progeny (Figure 4) that inherited the identical maternal white spotting allele.

Figure 4.

Family of domestic cats segregating White Spotting demonstrating difference in degree of White Spotting in individuals inheriting ws allele identical by descent. Squares = males; circles = females. Filled symbols, White Spotted individuals; open symbols, fully pigmented cat. ws, full-length FERV element in KIT; w+, wild-type allele.

Table 2. Genotype at White locus as associated with phenotype.

| Genotype | Phenotype/Observed Penetrance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Allelea: (Insertion element) | Coat pigmentf | Deafness | Iris colorg |

| W/W: (LTR/LTRb) | White (CP) | Deaf (IP) | Blue (IP) |

| W/w+: (LTR/no ins.) | White (CP) | Deaf (IP) | Blue, fully pigmentedg |

| W/ws: (LTR/FLd) | White (CP) | Deaf (IP) | No datah |

| ws/ws: (FL/FL) | White spotted (CP) | Normal (CP) | No datah |

| ws/w+: (FL/no ins)e | White spotted (CP) | Normal (CP) | No datah |

| w+/w+: (no ins./no ins.) | Fully pigmented | Normal | Fully pigmented |

W, White allele; ws, white spotting allele; w+, wild-type allele.

LTR: insertion of long terminal repeat of FERV1.

w+: wild-type, no insertion.

FL, insertion of full-length FERV1 element.

CP, completely penetrant; IP, incomplete penetrance.

Fully pigmented iris range from copper to hazel and green (Vella et al. 1999).

We have no phenotype for individuals with this genotype.

We determined that deafness is genetically linked to the triallelic KIT variant, which quantifies the qualitative observation that all deaf cats carry at least one W allele. Distinguishing the two non-W alleles adds informativeness to the marker and hence increases statistical power. For the initial penetrance function and a disease allele frequency of 0.01, the LOD score is +2.67. Varying the model parameter values (see Materials and Methods) caused the LOD score to vary in the range of +2.42 to +2.83. Because linkage was tested to only one marker, these LOD scores are significant at P < 0.0038 for the lowest score of +2.42 and P < 0.0015 for the highest score of +2.83 (Ott 1991). The correction for genome-wide multiple testing implicit in the typically used LOD score thresholds of +3.0 or +3.3 is not applicable in this usage of genetic linkage analysis. Deafness is statistically associated with the genotype of the KIT variant in the combined pedigrees 1 and 2. MQLS estimated P values in the range of 0.007 to 0.010, varying with the input prevalence of deafness and with the method of P value estimation. For the combined hypothesis of linkage and association, PSEUDOMARKER reported a P value of 0.000023.

There appears to be an influence of homozygosity at W relative to hearing capacity. In Pedigree 1, all W/W homozygotes (n = 22) demonstrated some degree of hearing impairment: 73% were deaf and 27% demonstrated partial hearing (Table S8, Table 3). In contrast, individuals that were heterozygous (W/w+) (n= 24) were much more likely to display some hearing capacity: 58% demonstrated normal hearing, 16.7% had partial hearing, and 20.8% were deaf (Table S8). All wild-type individuals demonstrated normal hearing. In individuals exhibiting the white spotting allele, although sample sizes are small, ws/ws homozygotes (n = 3) demonstrated normal hearing and W/ws heterozygotes (n = 6) were equally divided (33%) into hearing, deaf, or hearing impaired (Table S8). There were no ws/w+ individuals in the pedigree (Table 3).

Table 3. Genotype observed with respect to hearing capacity at the White locus, as observed in Pedigrees 1 and 2.

| Phenotypea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype at Wa | Deaf | Partial Hearing | Normal Hearing |

| W/W | 16 | 6 | 0 |

| W/w+ | 6 | 5 | 14 |

| w+/w+ | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| W/ws | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| ws/ws | 0 | 0 | 3 |

W, White allele; w+, wild-type allele; ws, white spotting allele. See Table S8 for hearing thresholds of individual animals that were used to assign phenotype.

We examined the correlation of the W and ws alleles with coat and iris color in a population genetic survey of cats of registered breed (n= 270), including 33 Dominant White cats, 94 white spotted individuals, and 143 fully pigmented cats (Menotti-Raymond et al. 2007) (Table 4, Table S9). All Dominant White individuals demonstrated the presence of the W allele, with six individuals demonstrating homozygosity for W (P < 0.0001). With the exception of one individual, all individuals demonstrating white spotting exhibited the ws allele (P < 0.0001). All but three of the fully pigmented individuals exhibited absence of either the W or ws allele (Table S9, Table 4) (P < 0.0001). Two of these individuals were from a near-hairless breed (Sphynx) in which white pigmentation is difficult to phenotype, often appearing pink (S. Pfluger, The International Cat Association cat breed judge, personal communication). We had no phenotypic information for hearing status in the population sample, except that the one cat that was homozygous for W was reported as both blue-eyed and deaf.

Table 4. Summary of genotypes at the W locus in a population survey of 30 cat breeds.

| Genotype at the White Locusa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/W | W/w+ | ws/ws | ws/w+ | w+/w+ | |

| Coat color phenotype | |||||

| Dominant White | 6 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White Spotting | 0 | 0 | 40 | 53 | 1 |

| Fully pigmented | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 140 |

| Total individuals | 6 | 27 | 42 | 54 | 141 |

W, White allele; ws, white spotting allele; w+, wild-type allele.

In the population sample, we were also able to examine the correlation between genotype at the W locus and iris color (Table S11). An individual that is homozygous W is much more likely to have blue iris, exhibiting odds 77.25-times larger than the odds of having blue irises of a genotype other than W/W (P < 0.0001). An individual that is heterozygous (W/w+) also demonstrates increased odds of having blue iris (OR = 4.667): four-times larger than the odds of having blue irises of a genotype other than W/w+ (P = 0.046). The odds of having blue irises in a wild-type individual is 0 (Table S11).

In humans, mutation of KIT is causative of a heterogeneous disorder, mastocytosis, which exhibits proliferation and accumulation of mast cells in the skin, bone marrow, and internal organs such as the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes (Orfao et al. 2007). A survey for mast cell profiles in tissues of white (n = 2) and pigmented cats (n = 2) revealed no substantive differences in mast cell distribution (Table S10).

Discussion

KIT encodes the mast/stem cell growth factor tyrosine kinase receptor. The heterozygous W mouse phenotype is similar to the human piebald trait, also caused by a KIT mutation, which is characterized by a congenital white hair forelock and ventral and extremity depigmentation (Fleischman et al. 1991). Mutations in coding or regulation of KIT have been characterized in additional species as causative of defects in pigmentation and hearing (Haase et al. 2007; Ruan et al. 2005; Spritz and Beighton 1998). Cable et al. (1995) have demonstrated that mutations in Kit do not prevent early melanoblast migration or differentiation in mice white spotting mutants but severely affect melanoblast survival during embryonic development.

Cairns et al. (2003) described murine cell type–specific DNase I hypersensitive sites that delineated Kit regulatory regions in primordial germ cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and melanoblasts. Genomic regions defined by the hypersensitive sites, once engineered into transgenic constructs driving green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression, demonstrated expression of GFP in vitro and in vivo through development of hematopoietic and germ cell lineages (Cerisoli et al. 2009). The W and ws alleles map within the 3.5-Kb DNase 1-hypersensitive site 2 (HS2) fragment, required for high-level expression of Kit (Figure 2) (Cairns et al. 2003). This genomic region is evolutionarily conserved across a range of mammals (Figure 2), suggesting that it is under selective constraint. We suggest that disruption of this regulatory region in the cat impacts melanocyte survival and/or migration.

Similar to other mammalian species, cats carry endogenous retroviral (ERV) genomic sequences descended from ancestral infections and integrations into the germ line. Approximately 4% of the assembled feline genome consists of sequence segments that are retroviral-like with the FERV1 family comprising approximately 1.05% of the genome (Pontius et al. 2007). The FERV1 integration site in KIT is unusual relative to the pattern of ERV insertions in the human genome, which are generally found in intergenic regions and rarely within an intron or in close proximity of a gene (Medstrand et al. 2002). It is clear from the data (Figure S1) that there was a single episode of insertion. We would envision the integration of the full-length retroelement, the white spotting allele (ws), followed at some point by recombination between the two LTRs of the integrated provirus, generating a single LTR, the W allele. LTR insertions are found for many classes of endogenous retroviruses and outnumber their full-length ancestral progenitors (Jern and Coffin 2008).

Retroviral insertions can be powerful agents for phenotypic change and are reported to impact a host of genetic mechanisms that can impact phenotype, including gene expression, splicing, and premature polyadenylation of adjacent genes (Jern and Coffin 2008; Boeke and Stoye 1997; Rosenberg and Jolicoeur 1997). Other retroviral insertion events have been reported to impact pigmentation (Clark et al. 2006; Jenkins et al. 1981), and there is report of a retroviral insertion that can affect transcriptional regulation of several unlinked loci (Natsoulis et al. 1991).

Why the full-length retroviral element (ws) results in a less extreme phenotype (white spotting) than the LTR (W) element is open for speculation. In the full-length element, a large 4908-bp open reading frame persists that corresponds to the Gag-Pol precursor protein of feline ERV DC-8 of the ERV1-1 family (Anai et al. 2012). However, presence of three stop codons precludes potential translation of a complete Gag-Pol polyprotein.

White cats with blue eyes represent the classic model of feline deafness. The inner ears of such cats exhibit degeneration of the cochlea and saccule, termed cochlea-saccule degeneration (Mair 1973). The cochleae of white kittens do not appear different from those of normal pigmented kittens at birth, with inner and outer hair cells intact in both groups. Within the first postnatal week, the cochleae of white kittens manifest degenerative changes, characterized by a pronounced atrophy of the stria vascularis and incipient collapse of Reissner’s membrane (Baker et al. 2010; Mair 1973). By the start of the second postnatal week, the tectorial membrane and the sensory receptor cells have been obliterated. Perhaps the most economical interpretation of the available evidence is that these latter events are secondary to some primary event involving the KIT mutation and melanocytes.

White cats lack melanocytes in the inner ear (Billingham and Silvers 1960). In contrast, albino cats, which have a normal distribution of melanocytes, are not deaf. Standard cochlear histology may be inadequate to identify the pathology that presumably already exists in the stria vascularis. While clear structural abnormalities are not evident in the cochleae of newborn kittens destined to become deaf, the central axon terminations of spiral ganglion neurons exhibit pathology: the endings are smaller, membrane appositions are shorter and less complex, and the number of synapses is reduced by 50% (Baker et al. 2010). It remains to be determined whether the pathologic changes in spiral ganglion cells represent a primary or secondary consequence to the genetic deafness.

We observed that homozygous (W/W) individuals were more likely than heterozygotes to be deaf (Table 4) and to have blue irises (Table S11). A report in the literature provides compelling evidence addressing the reduced incidence of deafness in W/+ individuals. Aoki et al. (2009) report that melanocytes derive from two distinct lineages with different sensitivity to Kit signaling. “Classical” murine melanocytes that migrate from the neural crest along a dorsal-lateral route to pigment skin and hair are highly KIT-sensitive. However, noncutaneous melanocytes, which travel a dorsal-ventral route to the inner ear and the iris, are less sensitive to KIT signaling, likely a consequence of lower KIT cell surface–receptor density, and are more effectively stimulated by endothelin 3 (EDN3) or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) than by KIT (Aoki et al. 2009). We propose that suppression or availability of KIT may be less severe in heterozygous individuals, allowing for modest survival and migration of noncutaneous melanocytes to the inner ear and iris. While this may explain some of the perceived lack of penetrance for deafness and blue iris coloration at the W locus, we have not observed a complete correlation between genotype for the FERV1 insertion and phenotype, suggestive of additional genetic modifying factors.

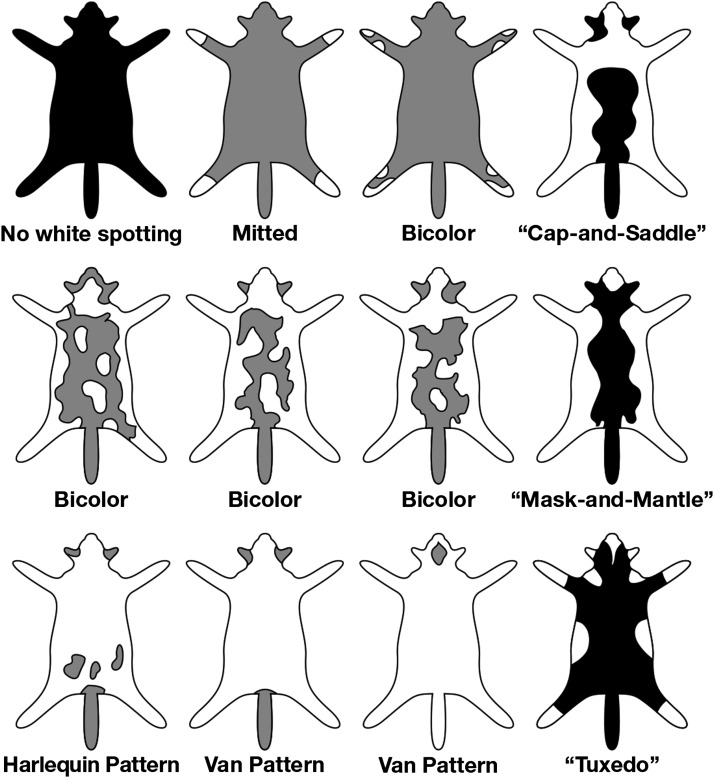

White spotting in the cat is observed as a continuum of white pigmentation from low-grade (face/paws/legs/white stomach) to medium-grade spotting covering 40% to 60% of the body to high-grade spotting (van pattern), with most of the body other than the head and tail being white (Vella et al. 1999) (Figure 5). Homozygosity vs. heterozygosity for the ws allele appears to have an influence on the degree of white pigmentation. In our population survey of two cat breeds that demonstrate a high degree of white spotting (Turkish Van, Japanese Bobtail) (Fogle 2001), 13 of 16 individuals demonstrated (ws/ws) genotypes (Table S9). By breed definition, a Turkish Van may have color on, at most, 15% of its body (http://www.cfainc.org/). Other genetic modifiers appear to influence melanoblast survival and migration as observed by the different degrees of white pigmentation in siblings that inherited the identical ws allele (Figure 4). None of the individuals of the Birman cat breed, which all exhibit white pigmentation of the paws, demonstrated the ws allele, supporting a recent report of Lyons (2010) of an independent mutation in KIT causative of Birman gloving.

Figure 5.

Graphic illustration of common pigmentation patterns in the cat.

The KIT insertion event is likely of relatively recent origin, as demonstrated by the fact that the LTR element exhibits complete sequence identity between the White and white spotting alleles. The cat was domesticated from the Near Eastern wildcat, Felis sylvestris lybica (Driscoll et al. 2007). Similar to other species that have experienced domestication, multiple coat color and hair phenotypes rapidly arose in the cat (Drogemuller et al. 2007; Eizirik et al. 2010, 2003; Ishida et al. 2006; Kehler et al. 2007; Lyons et al. 2005a,b; Menotti-Raymond et al. 2009; Schmidt-Küntzel et al. 2005; Kaelin et al. 2012), likely as the consequence of selection by humans of desirable phenotypes (Cieslak et al. 2011). A white cat, or white spotted cat (females can be calico), would likely have been a prized possession. Our population genetic data suggest that the white spotting and Dominant White phenotypes demonstrate the remarkable impact on phenotype at W by retroviral insertion and evolution, respectively. An allelic series of mutations in KIT has also been observed in the pig for several hypopigmentation phenotypes (Giuffra et al. 1999; Johansson et al. 2005; Pielberg and Olsson 2002) and is proposed in the horse (Haase et al. 2007).

The possibility that the alleles we defined here are not causal illustrates an ongoing issue in disease gene identification by linkage and association analysis, i.e., that a mapped locus will be tracking another causal mutation by linkage disequilibrium, particularly in an inbred cat. If there is an undiscovered causal variant for one or the other phenotype, then there are a few predictions we can assess. If White and white spotting mutations occurred after the FERV-kit and LTR-kit insertions, then FERV and LTR elements should today occur in both fully pigmented and white/white spotted individuals, and this is not the case given the presently available data set. If the White and white spotting mutations occurred before FERV-kit and LTR-kit insertions, then that would presuppose a FERV-kit insertion on one haplotype and a LTR-kit insertion on another haplotype, both at the identical position, which is quite unlikely. Also, in the latter scenario, one might expect some white or white spotted individuals without LTR and FERV insertion elements, but none has been observed. Therefore, given the present data and a comprehensive assessment of their potential historical processes that could have led to the observed patterns, the most plausible explanation is a causal relationship between the FERV1-related variants and the White/white spotted phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Frederickson and Joseph Meyer (Scientific Publications, Graphics & Media, SAIC-Frederick) for rendition of figures. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN26120080001E, the National Library of Medicine, NIH/NIDCD grant DC00232, NHMRC grant #1009482, and the Fairfax Foundation. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and the National Library of Medicine. This research was supported in part by Russian Ministry of Science Mega-grant no. 11.G34.31.0068 (S.J.O., primary investigator).

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available online at http://www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.114.013425/-/DC1

Communicating editor: B. J. Andrews

Literature Cited

- Agarwala R., Biesecker L. G., Hopkins K. A., Francomano C. A. and A. A. Schaffer, 1998. Software for constructing and verifying pedigrees within large genealogies and an application to the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County. Genet. Res. 8: 211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anai Y., Ochi H., Watanabe S., Nakagawa S., Kawamura M., et al. , 2012. Infectious endogenous retroviruses in cats and emergence of recombinant viruses. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 86: 8634–8644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki H., Yamada Y., Hara A., Kunisada T., 2009. Two distinct types of mouse melanocyte: differential signaling requirement for the maintenance of non-cutaneous and dermal vs. epidermal melanocytes. Development 136: 2511–2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attie, T., M. Till, A. Pelet, J. Amiel, P. Edery et al., 1995. Mutation of the endothelin-receptor B gene in Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 4: 2407–2409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker C. A., Montey K. L., Pongstaporn T., Ryugo D. K., 2010. Postnatal development of the endbulb of held in congenitally deaf cats. Front. Neuroanat. 4: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamber R. C., 1933. Correlation between white coat colour, blue eyes and deafness in cats. J. Genet. 27: 407–413 [Google Scholar]

- Baynash A. G., Hosoda K., Giaid A., Richardson J. A., Emoto N., et al. , 1994. Interaction of endothelin-3 with endothelin-B receptor is essential for development of epidermal melanocytes and enteric neurons. Cell 79: 1277–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsma D. R., Brown K. S., 1971. White fur, blue eyes, and deafness in the domestic cat. J. Hered. 62: 171–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrozpe G., Agosti V., Tucker C., Blanpain C., Manova K., et al. , 2006. A distant upstream locus control region is critical for expression of the Kit receptor gene in mast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 5850–5860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingham R. E., Silvers W. K., 1960. The melanocytes of mammals. Q. Rev. Biol. 35: 1–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke J. D., Stoye J. P., 1997. Retrotransposons, endogenous retroviruses, and the evolution of retroelements, pp. 343–436 in Retroviruses, edited by Coffin J. M., Hughes S. H., Varmus H. E.. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutin-Ganache I., Raposo M., Raymond M., Deschepper C. F., 2001. M13-tailed primers improve the readability and usability of microsatellite analyses performed with two different allele-sizing methods. Biotechniques 31: 24–26, 28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable J., Huszar D., Jaenisch R., Steel K. P., 1994. Effects of mutations at the W locus (c-kit) on inner ear pigmentation and function in the mouse. Pigment Cell Res. 7: 17–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable J., Jackson I. J., Steel K. P., 1995. Mutations at the W locus affect survival of neural crest-derived melanocytes in the mouse. Mech. Dev. 50: 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns L. A., Moroni E., Levantini E., Giorgetti A., Klinger F. G., et al. , 2003. Kit regulatory elements required for expression in developing hematopoietic and germ cell lineages. Blood 102: 3954–3962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerisoli F., Cassinelli L., Lamorte G., Citterio S., Bertolotti F., et al. , 2009. Green fluorescent protein transgene driven by Kit regulatory sequences is expressed in hematopoietic stem cells. Haematologica 94: 318–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot B., Stephenson D. A., Chapman V. M., Besmer P., Bernstein A., 1988. The proto-oncogene c-kit encoding a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus. Nature 335: 88–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak M., Reissmann M., Hofreiter M., Ludwig A., 2011. Colours of domestication. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 86: 885–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. A., Wahl J. M., Rees C. A., Murphy K. E., 2006. Retrotransposon insertion in SILV is responsible for merle patterning of the domestic dog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 1376–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. P., Fretwell N., Bailey S. J., Lyons L. A., 2006. White spotting in the domestic cat (Felis catus) maps near KIT on feline chromosome B1. Anim. Genet. 37: 163–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C., 1859. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, John Murray, London: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll C. A., Menotti-Raymond M., Roca A. L., Hupe K., Johnson W. E., et al. , 2007. The Near Eastern origin of cat domestication. Science 317: 519–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drögemuller, C., S. Rufenacht, B. Wichert and T. Leeb, 2007. Mutations within the FGF5 gene are associated with hair length in cats. Anim. Genet. 38: 218–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizirik E., David V. A., Buckley-Beason V., Roelke M. E., A. A. Schaffer et al., 2010. Defining and mapping mammalian coat pattern genes: multiple genomic regions implicated in domestic cat stripes and spots. Genetics 184: 267–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizirik E., Yuhki N., Johnson W. E., Menotti-Raymond M., Hannah S. S., et al. , 2003. Molecular genetics and evolution of melanism in the cat family. Curr. Biol. 13: 1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein D. J., Vekemans M., Gros P., 1991. Splotch (Sp2H), a mutation affecting development of the mouse neural tube, shows a deletion within the paired homeodomain of Pax-3. Cell 67: 767–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishelson M., Geiger D., 2002. Exact genetic linkage computations for general pedigrees. Bioinformatics 18(Suppl 1): S189–S198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishelson M., Geiger D., 2004. Optimizing exact genetic linkage computations. J. Comput. Biol. 11: 263–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischman R. A., Saltman D. L., Stastny V., Zneimer S., 1991. Deletion of the c-kit protooncogene in the human developmental defect piebald trait. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 10885–10889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flottorp G., Foss I., 1979. Development of hearing in hereditarily deaf white mink (Hedlund) and normal mink (standard) and the subsequent deterioration of the auditory response in Hedlund mink. Acta Otolaryngol. 87: 16–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogle B., 2001. The new encyclopedia of the cat, DK Publishing, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- Geigy C. A., Heid S., Steffen F., Danielson K., Jaggy A., et al. , 2006. Does a pleiotropic gene explain deafness and blue irises in white cats? Vet. J. 173: 548–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffra E., Evans G., Tornsten A., Wales R., Day A., et al. , 1999. The Belt mutation in pigs is an allele at the Dominant white ((I/KIT) locus. Mamm. Genome 10: 1132–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase B., Brooks S. A., Schlumbaum A., Azor P. J., Bailey E., et al. , 2007. Allelic heterogeneity at the equine KIT locus in dominant white (W) horses. PLoS Genet. 3: e195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase B., Brooks S. A., Tozaki T., Burger D., Poncet P.-A., et al. , 2009. Seven novel KIT mutations in horses with white coat colour phenotypes. Anim. Genet. 40: 623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbarth B., Pingault V., Bondurand N., Kuhlbrodt K., Hermans-Borgmeyer I., et al. , 1998. Mutation of the Sry-related Sox10 gene in Dominant megacolon, a mouse model for human Hirschsprung disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 5161–5165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiekkalinna T., A. A. Schaffer, B. Lambert, P. Norrgrann, H. H. H. Goring et al., 2011. PSEUDOMARKER: a powerful program for joint linkage and/or linkage disequilibrium analysis on mixtures of singletons and related individuals. Hum. Hered. 71: 256–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilding D. A., Sugiura A., Nakai Y., 1967. Deaf white mink: electron microscopic study of the inner ear. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 76: 647–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson C. A., Moore K. J., Nakayama A., E. Steingrimsson, N. G. Copeland et al., 1993. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell 74: 395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson C. A., Nakayama A., Li H., Swenson L.-B., Opdecamp K., et al. , 1998. Mutation at the anophthalmia white locus in Syrian hamsters: haploinsufficiency in the Mitf gene mimics human Waardenburg syndrome type 2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7: 703–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson W. R., Ruben R. J., 1962. Hereditary deafness in the Dalmatian dog. Arch. Otolaryngol. 75: 213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imes D. L., Geary L. A., Grahn R. A., Lyons L. A., 2006. Albinism in the domestic cat (Felis catus) is associated with a tyrosinase (TYR) mutation. Anim. Genet. 37: 175–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imesch P. D., Wallow I. H., Albert D. M., 1997. The color of the human eye: a review of morphologic correlates and of some conditions that affect iridial pigmentation. Surv. Ophthalmol. 41(Suppl 2): S117–S123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y., David V. A., Eizirik E., Schäffer A. A., Neelam B. A., et al. , 2006. A homozygous single-base deletion in MLPH causes the dilute coat color phenotype in the domestic cat. Genomics 88: 698–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., Taylor B. A., Lee B. K., 1981. Dilute (d) coat colour mutation of DBA/2J mice is associated with the site of integration of an ecotropic MuLV genome. Nature 293: 370–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jern P., Coffin J. M., 2008. Effects of retroviruses on host genome function. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42: 709–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A., Pielberg G., Andersson L., Edfors-Lilja I., 2005. Polymorphism at the porcine Dominant white/KIT locus influence coat colour and peripheral blood cell measures. Anim. Genet. 36: 288–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin C. B., Xu X., Hong L. Z., David V. A., McGowan K. A., et al. , 2012. Specifying and sustaining pigmentation patterns in domestic and wild cats. Science 337: 1536–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson E. K., Baranowska I., Wade C. M., Salmon Hillbertz N. H. C., Zody M. C., et al. , 2007. Efficient mapping of mendelian traits in dogs through genome-wide association. Nat. Genet. 39: 1321–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehler J. S., David V. A., Schäffer A. A., Eizirik E., Ryugo D. K., et al. , 2007. Four separate mutations in the feline Fibroblast Growth Factor 5 gene determine the long-haired phenotype in domestic cats. J. Hered. 98: 555–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W. J., 2002. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12: 656–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-Z., Newton V. E., Read A. P., 1995. Waardenburg syndrome type II: phenotypic findings and diagnostic criteria. Am. J. Med. Genet. 55: 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons L. A., 2010. Feline genetics: clinical applications and genetic testing. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 25: 203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons L. A., Foe I. T., Rah H. C., Grahn R. A., 2005a Chocolate coated cats: TYRP1 mutations for brown color in domestic cats. Mamm. Genome 16: 356–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons L. A., Imes D. L., Rah H. C., Grahn R. A., 2005b Tyrosinase mutations associated with Siamese and Burmese patterns in the domestic cat (Felis catus). Anim. Genet. 36: 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdesian K. G., Williams D. C., Aleman M., LeCouteur R. A., Madigan J. E., 2009. Evaluation of deafness in American Paint Horses by phenotype, brainstem auditory-evoked responses, and endothelin receptor B genotype. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 235: 1204–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair I. W., 1973. Hereditary deafness in the white cat. Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl. 314: 1–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus D. C., Wu T., Wangemann P., Kofuji P., 2002. KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) potassium channel knockout abolishes endocochlear potential. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282: C403–C407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medstrand P., van de Lagemaat L. N., Mager D. L., 2002. Retroelement distributions in the human genome: variations associated with age and proximity to genes. Genome Res. 12: 1483–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti-Raymond M., David V. A., Stephens J. C., Lyons L. A., O’Brien S. J., 1997. Genetic individualization of domestic cats using feline STR loci for forensic applications. J. Forensic Sci. 42: 1039–1051 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti-Raymond M. A., David V. A., Wachter L. L., Butler J. M., O’Brien S. J., 2005. An STR forensic typing system for genetic individualization of domestic cat (Felis catus) samples. J. Forensic Sci. 50: 1061–1070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti-Raymond M., David V. A., Pflueger S. M., Lindblad-Toh K., Wade C. M., et al. , 2007. Patterns of molecular genetic variation among cat breeds. Genomics 91: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti-Raymond M., David V. A., Eizirik E., Roelke M. E., Ghaffari H., et al. , 2009. Mapping of the domestic cat “SILVER” coat color locus identifies a unique genomic location for Silver in mammals. J. Hered. 100(Suppl 1): S8–S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mithraprabhu S., Loveland K. L., 2009. Control of KIT signalling in male germ cells: what can we learn from other systems? Reproduction 138: 743–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Y. V., Ryugo D. K., Brown M. C., 1994. Central trajectories of type II (thin) fibers of the auditory nerve in cats. Hear. Res. 79: 74–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsoulis G., Dollard C., Winston F., Boeke J. D., 1991. The products of the SPT10 and SPT21 genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae increase the amplitude of transcriptional regulation at a large number of unlinked loci. New Biol. 3: 1249–1259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfao A., Garcia-Montero A. C., Sanchez L., Escribano L., 2007. Recent advances in the understanding of mastocytosis: the role of KIT mutations. Br. J. Haematol. 138: 12–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J., 1991. Analysis of Human Genetic Linkage, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD [Google Scholar]

- Pielberg G., Olsson C., A.-C. Syvanen and L. Andersson, 2002. Unexpectedly high allelic diversity at the KIT locus causing dominant white color in the domestic pig. Genetics 160: 305–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingault V., Ente D., Dastot-Le Moal F., Goossens M., Marlin S., et al. , 2010. Review and update of mutations causing Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 31: 391–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontius J. U., Mullikin J. C., Smith D. R., Team A. S., Lindblad-Toh K., et al. , 2007. Initial sequence and comparative analysis of the cat genome. Genome Res. 17: 1675–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontius J. U., O’Brien S. J., 2007. Genome Annotation Resource Fields–GARFIELD: A genome browser for Felis catus. J. Hered. 98: 386–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg N., Jolicoeur P., 1997. Retroviral pathogenesis, pp. 475–586 in Retroviruses, edited by Coffin J. M., Hughes S. H., Varmus H. E.. Cold Spring Harbor Laboraory Press, Plainview, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan H.-B., Zhang N., Gao X., 2005. Identification of a novel point mutation of mouse proto-oncogene c-kit through N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea mutagenesis. Genetics 169: 819–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo D. K., Pongstaporn T., Huchton D. M., Niparko J. K., 1997. Ultrastructural analysis of primary endings in deaf white cats: Morphologic alterations in endbulbs of Held. J. Comp. Neurol. 385: 230–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo D. K., Rosenbaum B. T., Kim P. J., Niparko J. K., Saada A. A., 1998. Single unit recordings in the auditory nerve of congenitally deaf white cats: Morphological correlates in the cochlea and cochlear nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 397: 532–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo D. K., Cahill H. B., Rose L. S., Rosenbaum B. T., Schroeder M. E., et al. , 2003. Separate forms of pathology in the cochlea of congenitally deaf white cats. Hear. Res. 181: 73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saada A. A., Niparko J. K., Ryugo D. K., 1996. Morphological changes in the cochlear nucleus of congenitally deaf white cats. Brain Res. 736: 315–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Martin , M., A. Rodriguez-Garcia, J. Perez-Losada, A. Sagrera, A. P. Read et al., 2002. SLUG (SNAI2) deletions in patients with Waardenburg disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11: 3231–3236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, 2008 [SAS/STAT] software SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC.

- Schmidt-Küntzel A., Eizirik E., O’Brien S. J., Menotti-Raymond M., 2005. Tyrosinase and tyrosinase related protein 1 alleles specify domestic cat coat color phenotypes of the albino and brown loci. J. Hered. 96: 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvers W. K., 1979. The Coat Colors of Mice: a Model for Mammalian Gene Action and Interaction, Springer-Verlag, New York [Google Scholar]

- Smit, A. F. A., R. Hubley and P. Green, RepeatMasker Open-3.0. 1996–2010. <http://www.repeatmasker.org>.

- Southard-Smith E. M., Kos L., Pavan W. J., 1998. Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nat. Genet. 18: 60–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spritz R. A., Beighton P., 1998. Piebaldism with deafness: molecular evidence for an expanded syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 75: 101–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrris P., Carter N. D., Patton M. A., 1999. Novel nonsense mutation of the endothelin-B receptor gene in a family with Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. 87: 69–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M., Hara Y., Vyas D., Hodgkinson C., Fex J., et al. , 1992. Cochlear disorder associated with melanocyte anomaly in mice with a transgenic insertional mutation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 3: 433–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M., Perez-Jurado L. A., Nakayama A., Hodgkinson C. A., Li X., et al. , 1994. Cloning of MITF, the human homolog of the mouse microphthalmia gene and assignment to chromosome 3p14.1-p12.3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 3: 553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton T., McPeek M. S., 2007. Case-control association testing with related individuals: a more powerful quasi-likelihood score test. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81: 321–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimura, T., Morri, M., Nozaki, E, et al., 1991 The dominant white spotting (W) locus of the mouse encodes the c-kit proto-oncogene Blood 78:1936–1941.

- Vandenbark G. R., Chen Y., Friday E., Pavlik K., Anthony B., et al. , 1996. Complex regulation of human c-kit transcription by promoter repressors, activators, and specific myb elements. Cell Growth Differ. 7: 1383–1392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella C. M., Shelton L. M., McGonagle J. J., Stanglein T. W., 1999. Robinson’s Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, Boston [Google Scholar]

- White R. M., Zon L. I., 2008. Melanocytes in development, regeneration, and cancer. Cell Stem Cell 3: 242–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting P. W., 1918. Inheritance of coat-color in cats. J. Exp. Biol. 25: 539–569 [Google Scholar]

- Whiting P. W., 1919. Inheritance of white-spotting and other color-characters in cats. Am. Nat. 53: 473–482 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T. G., and F. Kane, 1959 Congenital deafness in white cats. Acta Otolaryngol. 50: 269–275; discussion 275–267. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wolff D., 1942. Three generations of deaf white cats. J. Hered. 33: 39–43 [Google Scholar]

- Yin T. C., Carney L. H., Joris P. X., 1990. Interaural time sensitivity in the inferior colliculus of the albino cat. J. Comp. Neurol. 295: 438–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhki N., Mullikin J. C., Beck T., Stephens R., O’Brien S. J., 2008. Sequences, annotation and single nucleotide polymorphism of the major histocompatibility complex in the domestic cat. PLoS ONE 3: e2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.