Abstract

The thioredoxin system, composed of thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) and thioredoxin (Trx), is widely distributed in nature, where it serves key roles in electron transfer and in defense against oxidative stress. Although recent evidence reveals Trx homologues are almost universally present among the methane-producing archaea (methanogens), a complete thioredoxin system has not been characterized from any methanogen. We examined the phylogeny of Trx homologues among methanogens and characterized the thioredoxin system from Methanosarcina acetivorans. Phylogenetic analysis of Trx homologues from methanogens revealed eight clades, with one clade containing Trxs broadly distributed among methanogens. The Methanococci and Methanobacteria each contain one additional Trx from another clade, respectively, whereas the Methanomicrobia contain an additional five distinct Trxs. M. acetivorans, a member of the Methanomicrobia, contains a single TrxR (MaTrxR) and seven Trx homologues (MaTrx1-7), with representatives from five of the methanogen Trx clades. Purified recombinant MaTrxR had DTNB reductase and oxidase activities. The apparent Km value for NADPH was 115-fold lower than the apparent Km value for NADH, consistent with NADPH as the physiological electron donor to MaTrxR. Purified recombinant MaTrx2, MaTrx6, and MaTrx7 exhibited DTT- and lipoamide-dependent insulin disulfide reductase activities. However, only MaTrx7, which is encoded adjacent to MaTrxR, could serve as a redox partner to MaTrxR. These results reveal that M. acetivorans harbors at least three functional and distinct Trxs, and a complete thioredoxin system composed of NADPH, MaTrxR, and at least MaTrx7. This is the first characterization of a complete thioredoxin system from a methanogen, which provides a foundation to understand the system in methanogens.

Keywords: thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, methanogen, anaerobe, archaea

INTRODUCTION

Thiol-disulfide exchange reactions are universal among all living cells. The most ubiquitous is the thioredoxin system, composed of thioredoxin (Trx) and the partner enzyme thioredoxin reductase (TrxR). TrxR and Trx are found in species from all three domains of life and the thioredoxin system is well characterized in species from the Bacteria and Eukarya domains, including humans [1]. The thioredoxin system plays a primary role in cellular redox maintenance and reduces disulfides in certain proteins. The two basic functions of the system are to supply electrons to biosynthetic enzymes, including ribonucleotide reductase, methionine sulfoxide reductase, and sulfate reductases, and to reduce inter- and intramolecular disulfides in oxidized proteins. TrxR specifically catalyzes the reduction of the disulfide in oxidized Trx using metabolism-derived NADPH as a source of reducing equivalents. The thioredoxin system also serves a critical role in protection from oxidative stress in many organisms [2]. Trx can reduce deleterious disulfide bonds in oxidatively-damaged proteins and also serve as a reducing partner to peroxiredoxins, which scavenge hydrogen peroxide. In bacteria, plants, and mammals the thioredoxin system plays a role in the regulation of gene expression and cell signaling [3]. The thioredoxin system is also important to the survival of pathogens [4]. Despite the ubiquitous importance of Trx, the properties and role(s) of the thioredoxin system in species from the domain Archaea is far less understood.

TrxR is a member of the dimeric flavoprotein family of pyridine nucleotide disulfide oxidoreductases, which includes lipoamide dehydrogenase, glutathione reductase, and mercuric reductase. Each TrxR subunit contains a FAD molecule and a redox-active disulfide, but two distinct types are currently known, a low molecular weight (L-TrxR) type comprised of ~ 35 kDa subunits and a high molecular weight (H-TrxR) type comprised of ~55 kDa subunits [5]. Both types of TrxR possess a NADPH-binding site and obtain reducing equivalents from NADPH. H-TrxR is found primarily in higher eukaryotes and the protozoan malaria parasite, while L-TrxR is found in archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes. Trxs are small proteins (~12 kDa) that contain a CXXC motif, whereby the two active site cysteines are separated by two amino acid residues. The canonical Trx active site motif is WCGPC, which is present in well-characterized Trxs from Escherichia coli and yeast [1]. Many organisms possess multiple Trxs, which can have distinct or overlapping activities and specificities. For example, E. coli and yeast contain two and three Trxs, respectively [6]. However, plants contain numerous Trxs which function in all compartments of plant cells [7].

Complete NADPH-dependent thioredoxin systems have been characterized from three archaea, Sulfolobus solfataricus, Aeropyrum pernix K1, and Pyrococcus horikoshii [8–10]. All three species are hyperthermophiles, with P. horikoshii being the only anaerobe. However, the target proteins of each system and the importance of the system to the metabolism and oxidative stress response of each archaeon is largely unknown. The methane-producing archaea (methanogens) are strict anaerobes and are the only organisms capable of biological methane production. There are currently four Classes of methanogens, the Methanopyri, Methanococci, Methanobacteria, and Methanomicrobia [11]. Species within the Methanopyri, Methanococci, and Methanobacteria are only capable of producing methane by the reduction of CO2. However, members of the Methanosarcinales, within the Methanomicrobia, are more metabolically diverse, capable of methanogenesis with methylated compounds and acetate. Moreover, only species of the Methanosarcinales possess cytochromes and are capable of producing methane from acetate, which is estimated to account for two-thirds of all biologically-produced methane [11]. Recent evidence revealed the presence of Trx homologues within all methanogens, except the single member of the Methanopyrales [12]. Thus, Trx likely serves a fundamental role in methanogens. Members of the Methanomicrobia are predicted to contain approximately twice as many Trxs as the Methanococci and Methanobacteria (~4 vs 2), which is likely a result of the metabolic diversity and larger genomes of the Methanomicrobia. The majority of species within the Methanosarcinales contain >5 Trx homologues [12]. A few Trxs have been characterized from methanogens, including Methanocaldococcus jannaschii and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus [13–15]. Recent evidence revealed Trx in M. jannaschii targets fundamental processes, including proteins involved in methanogenesis [12]. However, a complete thioredoxin system, in particular, a NADPH-dependent TrxR, has yet to be characterized from a methanogen. Moreover, none of the components of the thioredoxin system from a member of the Methanosarcinales have been characterized. We are particularly interested in deciphering the role of the thioredoxin system in the Methanosarcinales, using Methanosarcina acetivorans as a model system. We report here that M. acetivorans contains seven Trx homologues and a single TrxR homologue. Purification and characterization studies reveal that M. acetivorans contains at least three functional Trxs and a complete NADPH-dependent thioredoxin system.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analysis of methanogen thioredoxins

Recent analysis of the sequenced genomes of methanogens identified 123 Trx homologues [12]. Using E. coli Trx1 (EcTrx1) and M. jannaschii Trx1 (MjTrx1) as BLAST queries, we found seven Trx homologues encoded in the genome of M. acetivorans C2A, which is two more than previously reported [12]. Because of this discrepancy we further searched the genomes of methanogens for additional Trxs, finding another 18 (Table S1). On average one additional Trx homologue was found specifically in some members of the Methanomicrobia. However, four additional Trx homologue were found in the genome of Methanosarcina barkeri str. Fusaro, bringing the total to 9 Trx, the most predicted in any methanogen. All of the sequenced Methanosarcina species contain at least seven Trx homologues (Table S1).

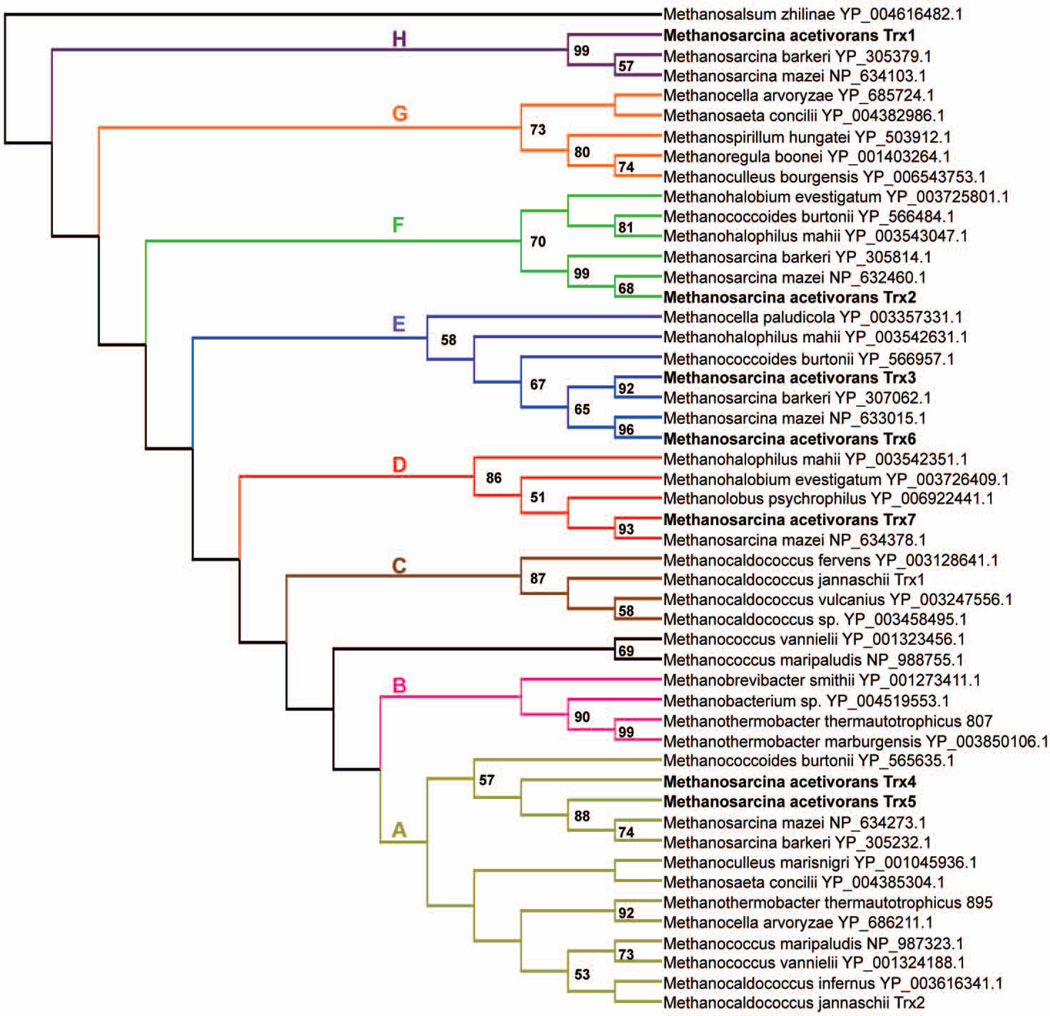

Phylogenetic analysis of the methanogen Trx homologues revealed a relationship between Trxs at the Class and Order levels. Figure 1 is a simplified version of the complete phylogenetic tree (Fig. S1). Based on the phylogeny, we identified at least 8 clades (A–H), recognizing that some of these groupings have more support than others. Clade A contains the largest number of Trxs, including sequences from the Methanococci, Methanobacteria, and Methanomicrobia. M. jannaschii Trx2, which was shown to have limited Trx activity [12], is a member of clade A. Clade A also contains MTH895 from Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus ΔH for which the structure has been determined [14]. Clades B and C only include Trxs from the Methanobacteria and Methanococci, respectively, indicating Trxs within these clades are distinct from other Trxs found in the Methanomicrobia. M. jannaschii Trx1 (MjTrx1), which has Trx activity and was shown to target fundamental processes [12, 15], is found in clade C. Clades D through H contain Trxs that are restricted to members of the Methanomicrobia. All seven Trxs of the well-supported clade D are restricted to the Order Methanosarcinales and are encoded by a gene that is directly upstream of the gene encoding the putative TrxR in each species. This gene location indicates these Trxs likely serve as a substrate for the corresponding TrxR. Clade E contains Trxs that have a predicted N-terminal signal peptide, indicating these Trxs are likely extracellular. Interestingly, many of the genes encoding clade E Trxs are directly upstream of a gene encoding a homolog of CcdA, which functions in transferring electrons to extracellular ResA, a Trx-like protein. CcdA/ResA are components of cytochrome c biogenesis system II [16]. Thus, clade E Trxs may play a role in cytochrome c maturation or in the general reduction of disulfides in extracellular proteins. All clade F Trxs contain the consensus Trx active site motif (WCGPC) and are not located near genes that hint at a particular function or location. Clade G Trxs are distributed within the Methanomicrobia, but are not present in the genomes of Methanosarcina species. However, Trxs within clade H are primarily restricted to members of the order Methanosarcinales. Overall, it appears that the majority of methanogens contain a clade A Trx, but methanogens within the Methanomicrobia have acquired at least five different Trxs that are distinct from the additional Trxs found in the Methanococci and Methanobacteria.

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic analyses of methanogen Trx homologues.

A simplified phylogenetic tree based on the complete tree (Fig. S1). Clades (A–H) are labelled and differently colored. Numbers above nodes represent maximum-likelihood bootstrap values; only values >50% are shown.

Methanosarcina acetivorans thioredoxin homologues

We have named the seven Trx homologues in M. acetivorans C2A MaTrx1-7 based on gene annotation number (Table 1). Overall, the sequence identity between the seven MaTrxs is <40%, with the exception of MaTrx4 and MaTrx5 (~48%) and MaTrx3 and MaTrx6 (~70%). M. acetivorans contains Trx homologues from five of the eight identified Trx clades based on phylogeny (Fig. 1 and Table 1), with MaTrx4/5 and MaTrx3/6 of the same clade. Each MaTrx contains an active site CXXC-motif (Fig. S2) and has 30–40% overall sequence identity to EcTrx1. Of the seven MaTrxs, only MaTrx2 and MaTrx6 have the conventional WCGPC active site motif (Fig. S2). MaTrx1 contains a CPYC motif, typical of glutaredoxins [1]. The genes encoding MaTrx1 and MaTrx2 are likely monocistronic. MaTrx3 and MaTrx6 contain a putative N-terminal signal peptide, including a lipobox (Fig. S2) [17], indicating each is likely targeted across the membrane and function extracellularly. The gene encoding MaTrx6 is adjacent to ccdA encoding a membrane protein predicted to function in cytochrome c maturation [16]. The gene encoding MaTrx3 is downstream of ma3703 encoding a predicted cell surface protein. MaTrx4 and MaTrx5 are the smallest MaTrxs (Table 1) and have the same active site sequence (Fig. S2). The gene encoding MaTrx4 may be co-transcribed with ma3937 and ma3939, each encoding a hypothetical protein. The gene encoding MaTrx5 is likely in an operon, adjacent to maTrx4, which includes hypothetical proteins and a universal stress protein. MaTrx7 is encoded by a gene directly upstream of ma1368, encoding the only predicted TrxR in M. acetivorans. Four (MaTrx1, MaTrx2, MaTrx6, and MaTrx7) of the MaTrxs were detected in previous proteomic analyses [18–20], consistent with each having cellular function.

Table 1.

Thioredoxin system homologues encoded in the genome of M. acetivorans C2A.

| Gene ID | homologue designation |

Predicted location | Trxhomologue clade |

pI/MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA1368 | MaTrxR | Cytoplasm | - | 5.8/34.0 |

| MA0965 | MaTrx1 | Cytoplasm | H | 4.7/15.0 |

| MA3212 | MaTrx2 | Cytoplasm | F | 5.1/10.4 |

| MA3702 | MaTrx3 | Extracellular/membrane | E | 4.7/19.6 |

| MA3938 | MaTrx4 | Cytoplasm | A | 5.4/8.4 |

| MA3942 | MaTrx5 | Cytoplasm | A | 8.5/8.7 |

| MA4254 | MaTrx6 | Extracellular/membrane | E | 4.2/17.7 |

| MA4683 | MaTrx7 | Cytoplasm | D | 5.6/9.2 |

Conserved TrxR in the Methanosarcinaceae

A BLAST with the EcTrxR amino acid sequence revealed the majority of methanogens contain at least one protein with homology to EcTrxR, including conservation of the coenzyme-binding and active site residues (data not shown). Therefore, the majority of methanogens may contain a complete thioredoxin system, composed of a L-TrxR and at least one Trx. Interestingly, Methanopyrus kandleri AV19, which does not contain an apparent Trx [12], encodes a putative TrxR (MK1561) that contains conserved coenzyme-binding and active-site residues. The TrxR in M. kandleri may be linked to proteins other than Trx. The TrxR in seven of the sequenced species of the Methanosarcinaceae (listed in Fig. S3) is encoded downstream of a clade D Trx. The Methanosarcinaceae TrxRs share >50% sequence identity to each other and >35% sequence identity to EcTrxR. Moreover, the FAD-binding, NAD(P)H-binding, and active site cysteine residues are all conserved in the Methanosarcinaceae TrxRs, including the only TrxR from M. acetivorans (Fig. S3 and Table 1). These results indicate that the Methanosarcinaceae have at least one NAD(P)H-dependent TrxR, which likely serves as the reducing partner to at least the clade D Trx in each species.

Purification and biochemical properties of recombinant MaTrxR

To examine the catalytic properties of MaTrxR, His-tagged recombinant MaTrxR was purified to homogeneity as revealed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). Purified MaTrxR was slightly yellow indicative of the presence of flavin. The visible absorption spectrum of purified MaTrxR revealed absorbance maxima at 380 and 460 nm (Fig. 3A), typical for flavoproteins [21]. However, as-purified MaTrxR yielded an A280/A460 ratio of 13.0, higher than the ratio observed for other TrxRs, including EcTrxR [21], indicating recombinant MaTrxR may not have full incorporation of FAD. To determine if as-purified MaTrxR was specific for FAD and had full incorporation, the protein was incubated with excess FAD in the presence of DTT and subsequently re-purified. FAD-reconstituted MaTrxR had a visible spectrum with a substantial increase in absorbance at 380 and 460 nm (Fig. 3A), resulting in an A280/A460 ratio of 3.3 consistent with full incorporation of FAD. FAD-reconstituted MaTrxR was used for all subsequent analyses.

Fig. 2. SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant proteins purified from E. coli.

The purified recombinant proteins (3 µg each) were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE. MW, Marker lane.

Fig. 3. Spectroscopic analysis of MaTrxR.

(A) UV-visible spectrum of 10 µM as-purified MaTrxR (gray line) and FAD-reconstituted MaTrxR (black line). Inset: magnified spectrum of as-purified MaTrxR. (B) Spectrum of 6.3 µM MaTrxR before (black line) and after (gray line) the addition of 70 µM NADPH under anaerobic conditions. (C) Spectrum of 6.3 µM MaTrxR before (black line) and after (gray line) the addition of 110 µM NADH under anaerobic conditions. All spectra were of MaTrxR in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl.

The majority of TrxRs are reduced by NADPH and NADH, but have a strong preference for NADPH [5]. Anaerobic incubation of MaTrxR with excess NADPH or NADH resulted in rapid reduction of the bound FAD, as revealed by the decrease in absorbance at 460 nm (Fig. 3). Exposure of both NADH- or NADPH-reduced MaTrxR to oxygen resulted in a rapid oxidation of the bound FAD and restoration of the absorbance maxima at 380 and 460 nm (data not shown). Similar to TrxR from S. solfataricus [22], MaTrxR exhibited NADPH- and NADH-dependent oxidase activity (Table 2). Although, the majority of L-TrxRs are incapable of direct reduction of DTNB, unlike H-TrxRs, L-TrxRs characterized from some archaea and bacteria have been shown to catalyze the direct reduction of DTNB [9, 23, 24]. MaTrxR also possesses DTNB-reductase activity with both NADPH and NADH (Table 2), similar to L-TrxRs from other archaea [9, 23].

Table 2.

MaTrxR activity with different electron donors and acceptors.

| e− donor | e− acceptor | Specific activity |

|---|---|---|

| NADPH | DTNB | 0.3 ± 0.005a |

| NADH | DTNB | 0.5 ± 0.005a |

| NADPH | O2 | 2.9 ± 0.07b |

| NADH | O2 | 0.13 ± 0.01b |

µmol TNB min−1 mg−1 TrxR

µmol NAD min−1 mg−1 TrxR

To examine coenzyme specificity of MaTrxR, the DTNB reduction assay was used to determine kinetic parameters with either NADPH or NADH as the electron donor. The apparent Km value for NAPDH was 6.3 ± 0.5 µM, with a catalytic efficiency of 6.2 (µM−1 min−1), which was approximately 100 times higher than the value obtained with NADH (Table 3). The apparent Km value for NADPH is similar to those from other TrxRs, including EcTrxR [25]. DTNB reduction activity of MaTrxR with F420H2 as the electron donor was below the detection limit (data not shown). These results are consistent with MaTrxR as a NADPH-dependent TrxR, similar to TrxRs from bacteria, other archaea, and eukaryotes.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of MaTrxR.

| substrate | Km (µM) |

Kcat (min−1) |

Kcat/Km (µM−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NADHa | 736 ± 57 | 49 | 0.067 |

| NADPHa | 6.3 ± 0.5 | 39 | 6.2 |

| MaTrx7b | 86 ± 5 | 70.5 | 0.82 |

Measured using the DTNB assay as described in materials and methods

Measured using the GHOST assay with NADPH as described in materials and methods

Purification and biochemical properties of MaTrx2, MaTrx6, and MaTrx7

MaTrx2, MaTrx6, and MaTrx7 were chosen for initial biochemical characterization, because all three proteins have been detected in the proteome of M. acetivorans [19, 20] and MaTrx2 and MaTrx6 each contain the consensus Trx active site (WCGPC) (Fig. S2). Although, MaTrx7 lacks the consensus Trx active site, it is linked to MaTrxR on the chromosome of M. acetivorans, indicating MaTrxR may be specific for MaTrx7. MaTrx2, MaTrx6, and MaTrx7 were expressed in E. coli with a thrombin-cleavable His-tag. His-tagged MaTrx2 and MaTrx7 were found in the soluble (cytoplasmic) fraction of E. coli, whereas full length MaTrx6 was found in the insoluble (membrane) fraction (data not shown), consistent with the predicted location of each MaTrx (Table 1). However, expression of MaTrx6 deleted of the putative signal peptide (Fig. S2), designated MaTrx6Δsp, resulted in MaTrx6 being found in the soluble fraction of E. coli lysate (data not shown). This result suggests E. coli recognizes full-length MaTrx6 as a membrane-associated protein, consistent with MaTrx6 containing a signal peptide. MaTrx2, MaTrx6Δsp, and MaTrx7, each with the His-tag removed, were purified to homogeneity as revealed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2).

MaTrx2, MaTrx6Δsp, and MaTrx7 were examined for disulfide reductase activity using the insulin reduction assay, with DTT, lipoamide, glutathione, or coenzyme M as the source of reducing equivalents [26]. All three purified MaTrxs exhibited both DTT- and lipoamide-dependent insulin reduction activity (Fig. 4), but no activity was observed with glutathione or coenzyme M (data not shown), typical for Trxs. However, despite both MaTrx2 and MaTrx6Δsp possessing the consensus Trx active site motif, the insulin reduction activity of MaTrx2 was 8–18 fold lower than the activities determined for MaTrx6Δsp (Fig. 4, insets). The insulin reduction activity of MaTrx6Δsp was also approximately 2-fold higher than the activity determined for MaTrx7. The DTT-dependent insulin reduction activity of EcTrx1, assayed under the same experimental conditions, was 785 (ΔA650/min2 × 10−3)/mg, similar to the activity obtained for MaTrx7, but 2-fold lower than MaTrx6Δsp (Fig. 4). These results reveal that MaTrx2, MaTrx6, and MaTrx7 are capable of reducing disulfides in proteins and therefore have the capacity to function as in vivo disulfide reductases. Also, MaTrx6 has the highest disulfide reductase activity of the MaTrxs examined, which could be related to MaTrx6 likely being an extracellular protein.

Fig. 4. Comparison of the reduction of insulin catalyzed by MaTrxs.

(A) DTT-dependent activity: 9 µM MaTrx2 (triangles), 3 µM MaTrx6ΔSp (squares), and 6 µM MaTrx7 (diamonds) were added to 0.33 mM DTT and 0.13 mM insulin in 100 mM KPO4 pH 6.8 under anaerobic conditions. The complete reaction without the addition of thioredoxin was included as a negative control (circles). Absorbance at 650 nm at 2 min intervals is shown. The data are the mean ± SD of triplicate reactions and the specific activity (ΔA650/min2 × 10−3/mg) of each thioredoxin is shown in the inset. (B) Lipoamide-dependent activity: 12 µM MaTrx2 (triangles), 3 µM MaTrx6ΔSp (squares), and 6 µM MaTrx7 (diamonds) were added to 0.33 mM NADH, 4 units lipoamide dehydrogenase, 0.05 mM lipoamide and 0.13 mM insulin in 100 mM KPO4 pH 6.8 under anaerobic conditions. The complete reaction without the addition of thioredoxin was included as a negative control (circles). Absorbance at 650 nm at 4 min intervals is shown. The data are the mean ± SD of triplicate reactions and the specific activity (ΔA650/min2 × 10−3/mg) of thioredoxin is shown in the inset.

Specificity of MaTrxR for MaTrxs

The ability of MaTrxR to serve as a direct electron donor to MaTrx2, MaTrx6Δsp, and MaTrx7 was examined. Initial assays examining MaTrxR-dependent NADPH or NADH oxidation in the presence of each oxidized MaTrx as an electron acceptor indicated MaTrxR is specific for MaTrx7 (data not shown). The ability of MaTrxR to form a complete thioredoxin system with MaTrx2, MaTrx6Δsp, or MaTrx7 was tested using the insulin reduction assay. Of the three MaTrxs, only MaTrx7 catalyzed the reduction of insulin when incubated with MaTrxR and either NADPH or NADH at a concentration above the apparent Km for each coenzyme (Fig. 5). Neither MaTrx2 nor MaTrx6Δsp at twice the concentration of MaTrx7 resulted in reduction of insulin above background. It is not surprising that MaTrx6 is not directly reduced by MaTrxR, since MaTrx6 is probably extracellular. On the other hand, MaTrx2 is likely cytoplasmic, but these data revealed MaTrx2 is not a redox partner to MaTrxR. Interestingly, EcTrx1, at twice the concentration of MaTrx7, exhibited MaTrxR-dependent insulin reduction activity (Fig. 5), albeit 100-fold lower than MaTrx7. The MaTrxR-EcTrx1 activity with NADPH was 2.0 ± 0.26 (ΔA650/min2 × 10−3)/mg compared to MaTrxR-MaTrx7 with NADPH of 223 ± 30 (ΔA650/min2 × 10−3)/mg. The DTNB reductase assay is commonly used to determine TrxR-Trx reaction kinetic parameters; but, since MaTrxR has DTNB reductase activity, this assay could not be used to determine the MaTrxR-MaTrx7 kinetic parameters. However, since MaTrxR could not reduce oxidized glutathione (data not shown), the GHOST assay, which uses oxidized glutathione as a substrate for Trx [27], was utilized to determine the MaTrxR-MaTrx7 kinetic parameters (Table 3). The apparent Km value for MaTrx7 is higher than that observed for E. coli and yeast Trxs [25, 28], but is comparable to Km values obtained for Trxs from other archaea [8, 9]. These results revealed that M. acetivorans contains a complete NADPH-dependent thioredoxin system comprised of MaTrxR and at least MaTrx7. For MaTrx2 and MaTrx6 to function in vivo these Trxs must be linked to a redox partner other than MaTrxR.

Fig. 5. Comparison of the reduction of insulin catalyzed by the M. acetivorans thioredoxin system components.

(A) NADPH-dependent activity: 10 µM MaTrx2, 10 µM MaTrx6ΔSp, 5 µM MaTrx7, or 10 µM EcTrx1 were added to 0.35 mM NADPH, 1 µM MaTrxR, and 0.13 mM insulin in 100 mM KPO4 pH 6.8 under anaerobic conditions. The complete reaction without the addition of thioredoxin was included as a negative control (not shown). Absorbance at 650 nm at 4 min intervals is shown. The data are the mean of triplicate reactions. (B) NADH-dependent activity: 10 µM MaTrx2, 10 µM MaTrx6ΔSp, 5 µM MaTrx7, or 10 µM EcTrx1 were added to 1 mM NADH, 1 µM MaTrxR, and 0.13 mM insulin in 100 mM KPO4 pH 6.8 under anaerobic conditions. The complete reaction without the addition of thioredoxin was included as a negative control (not shown). Absorbance at 650 nm at 4 min intervals is shown. The data are the mean of triplicate reactions.

DISCUSSION

Methanogens are strictly anaerobic prokaryotes that were likely present prior to the appearance of oxygen on earth. Methanogens are specialists, only capable of growth by methanogenesis, which requires unique cofactors, coenzymes, and enzymes. Methanogens lack glutathione [29–31], but contain small thiol-containing coenzymes, such as CoA, coenzyme M, and coenzyme B [11]. Moreover, the primary electron carriers in methanogens are F420 and ferredoxin, instead of NAD/NADP, which are used by the majority of other organisms. Therefore, it is plausible that methanogens may contain variant thioredoxin systems. An understanding of the thioredoxin system(s) in methanogens may provide insight into the evolution and diversification of the thioredoxin system. Recent evidence revealed MjTrx1 from M. jannaschii is capable of reducing disulfides in numerous oxidized M. jannaschii proteins, including enzymes directly involved in methanogenesis and biosynthesis [12]. This result indicates Trx likely played a fundamental role in cells before the rise of atmospheric oxygen levels. MjTrx1 is a member of methanogen Trx clade C and is distinct from Trx homologues found in other methanogens (Fig. 1). The other Trx in M. jannaschii (MjTrx2) is a member of clade A and was shown to have limited insulin disulfide reduction activity [12], indicating it may not function as a true Trx. Thus, M. jannaschii and the majority of the Methanococci may have one primary Trx. In contrast, the Methanomicrobia contain 2–4 times as many Trxs as the Methanococci, all of which appear distinct from MjTrx1 (Fig. 1). For example, M. acetivorans, a member of the Methanomicrobia and the focus of this study contains at least five distinct Trx homologues. Why do some methanogens apparently have a need for additional Trxs?

Members of the Methanomicrobia, specifically the Methanosarcinales, are the most metabolically diverse methanogens, capable of hydrogenotrophic (CO2-reducing), methylotrophic, and aceticlastic methanogenesis [11]. Methanomicrobia typically have larger genomes than the Methanococci and Methanobacteria, which are restricted to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. M. acetivorans possesses the largest genome of any methanogen, and is capable of growing by methylotrophic and aceticlastic methanogenesis [32]. Although, M. acetivorans is incapable of hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, it can conserve energy by CO-dependent reduction of CO2 to CH4 [19, 33]. The growth of M. acetivorans with different substrates (CO, methanol, and acetate) requires large-scale changes in protein and gene expression, including electron carriers, electron transport system components, and methanogenesis enzymes [19, 20, 34]. Thus, M. acetivorans, and other members of the Methanomicrobia may have acquired additional Trxs that rely on different redox partner(s) and are specific for different targets to correlate with changes in electron carriers and enzymes used during growth with CO, methylated substrates, and acetate. For example, F420 is the primary electron carrier used during growth with methanol, whereas ferredoxin is the primary electron carrier during growth with acetate [35].

We show here that M. acetivorans contains a complete thioredoxin system comprised of NADPH, MaTrxR, and at least MaTrx7. MaTrx7 is a member of methanogen Trx Clade D, which contains Trxs only found in the Methanosarcinales. Given the gene location and lack of activity with MaTrx2 and MaTrx6, MaTrxR is likely specific for MaTrx7. MaTrxR-MaTrx7 may have been acquired from bacteria to carry out a function specific to members of the Methanosarcinales. Outside of the Methanosarcinales, the amino acid sequence of MaTrxR has highest identity to TrxR (TOL2_C00640) from Desulfobacula toluolica Tol2 (51%), an anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacterium [36]. Interestingly, D. toluolica Tol2 and several other sulfate-reducing bacteria have the same gene arrangement (trx-trxR) as in the Methanosarcinales. Thus, it is possible MaTrxR and MaTrx7 were acquired from sulfate-reducing bacteria, which is consistent with the previous proposal that gene acquisition from anaerobic bacteria led to the evolution of the Methanomicrobia [37, 38]. Enzyme assays revealed MaTrxR is specific for NADPH and cannot be reduced by F420H2. NADP is not directly reduced by methanogenesis enzymes, signifying reducing equivalents are not directly transferred to MaTrxR from a methanogenesis enzyme. However, methanogens contain enzymes that could mediate electron transfer from F420H2 or reduced ferredoxin to NADP. F420H2:NADP oxidoreductase (Fno) catalyzes the reversible hydride transfer from F420H2 to NADP. Fno functions to produce NADPH for biosynthesis in the majority of methanogens [39, 40], consistent with the primary function of Trx in most cells. The genome of M. acetivorans encodes one Fno (MA4235) that may be responsible for the generation of NADPH from F420H2 needed by MaTrxR in M. acetivorans. Ferredoxin is reduced by carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase with electrons supplied by the oxidation of the carbonyl group of acetate [41]. For MaTrxR to function in M. acetivorans during growth with acetate, reduced ferredoxin would likely need to directly or indirectly supply electrons to NADP. Ferredoxin:NADP oxidoreductases (Fnr) are flavoenzymes that catalyze the reversible transfer of reducing equivalents from ferredoxin to NADP, and are common in plants and bacteria [42]. M. acetivorans contains a homolog of NADH-dependent reduced ferredoxin:NADP oxidoreductase (NfnAB), encoded by ma3786-87. In Clostridia and related anaerobic bacteria, NfnAB catalyzes an electron bifurcation reaction, whereby the endergonic reduction of NADP with NADH is coupled to the exergonic reduction of NADP with reduced ferredoxin [43]. Interestingly, among methanogens, NfnAB appears restricted to the Methanomicrobia [44]. However, NfnAB has not been characterized from a methanogen, so its precise function is not clear. Nonetheless, M. acetivorans would likely not use NfnAB to generate NADP with NADH, since NADH is not directly produced during methanogenesis. In M. acetivorans, and other Methanomicrobia, NfnAB may catalyze the exergonic reduction of NADP with reduced ferredoxin to supply MaTrxR and other NADPH-dependent biosynthetic enzymes with NADPH.

Although only MaTrx2, MaTrx6, and MaTrx7 were tested as substrates for MaTrxR, the lack of activity with MaTrx2 and MaTrx6, along with the conserved trx-trxR gene arrangement in the Methanosarcinales, indicates MaTrx7 is likely the only Trx substrate of MaTrxR. MaTrx7 has a unique active site (CTAC) which likely contributes to specific interactions with MaTrxR. Both MaTrx2 and MaTrx6 have the conventional Trx active site (CGPC), as found in EcTrx1. Thus, it was surprising that MaTrxR was unable to reduce MaTrx2 or MaTrx6, but could reduce EcTrx1, albeit not as efficiently as MaTrx7 (Fig. 5). This result suggests that interaction of TrxR with Trx is controlled by more than just the active site region of Trx. Indeed, examination of the specificity of yeast TrxR for the three yeast Trxs revealed three interaction loops within Trx [28], two of which are found in all MaTrxs. In particular, interaction loop 3 is more similar between MaTrx7 and EcTrx1, than between MTrx7 and MaTrx2 or MaTrx6 (Fig. S2), which may explain why MaTrxR is able to reduce EcTrx1, but not MaTrx2 or MaTrx6. Given the differences in activity of MaTrxR with MaTrxs and EcTrx1, the M. acetivorans thioredoxin system could provide an attractive model to understand the specificity of TrxRs and Trx for redox partners.

MjTrx1 was shown to target a large number of oxidized proteins in M. jannaschii, consistent with MjTrx1 as the primary, if not only Trx, in M. jannaschii [12]. However, the redox partner to MjTrx1 has not been identified, so it is unclear what protein(s) provides reducing equivalents in vivo to MjTrx1. M. jannaschii contains a TrxR homolog (Mj1356), but experiments by Lee et al showed that recombinant Mj1356 was incapable of reducing MjTrx1 with NADPH [15]. However, it was not clear if the lack of reduction was due to the inability of MJ1356 to be reduced by NADPH or the lack of interaction with MjTrx1. Nonetheless, these results indicate that M. jannaschii, and possibly all Methanococci, have a thioredoxin system not dependent on NADPH, unlike members of the Methanomicrobia. In M. jannaschii, the reduction of MjTrx1 may be directly linked to reduction by methanogenesis electron carriers (F420H2 or reduced ferredoxin). Similarly, the reduction of the other MaTrxs could be directly linked to F420H2 or reduced ferredoxin. Overall, linking the reduction of cytoplasmic Trxs in M. acetivorans to different electron carriers may allow M. acetivorans to control the specificity and activity of redox proteins within the cell under different growth conditions. Changes in MaTrx abundance may also provide a mechanism to modulate electron transfer during changing growth conditions. For example, expression of MaTrx2 was shown to be up-regulated in acetate-grown cells compared to methanol-grown cells of M. acetivorans [20].

Interestingly, not all of the Trx homologues in M. acetivorans are cytoplasmic. MaTrx3 and MaTrx6 (clade E Trxs, Fig. 1) contain an N-terminal signal peptide (Fig. S2), indicating each is likely targeted across the membrane. Clade E Trxs are only found in the Methanomicrobia, which contains the only methanogens that harbor cytochromes, including cytochrome c. M. acetivorans in particular has been shown to use a cytochrome c as part of an Rnf complex to facilitate transfer of electrons from ferredoxin to heterodisulfide reductase [45, 46]. However, the machinery responsible for cytochrome c maturation in methanogens has not been identified. The gene encoding MaTrx6 is adjacent to ccdA in the genome of M. acetivorans, suggesting MaTrx6 may receive reducing equivalents from CcdA to reduce disulfides in apo-cytochrome c, similar to the process found in bacteria [16].

Conclusions

Results from this study revealed that methanogens contain Trx homologues distributed within at least eight clades, with the Methanococci and Methanobacteria restricted to Trxs within 1–2 clades, while the Methanomicrobia contain Trxs from >2 clades. The characterization of thioredoxin system components from M. acetivorans, provides the first insight into the role of the thioredoxin system in the metabolically diverse cytochrome-containing methanogens. Importantly, we demonstrate that M. acetivorans contains a complete NADPH-dependent thioredoxin system (MaTrxR-MaTrx7), providing the first experimental evidence for the presence of this system in methanogens. The use of a NADPH-dependent thioredoxin system may be specific to Methanomicrobia, but additional experimentation is needed to understand how widespread the NADPH-dependent system is. M. acetivorans contains at least two Trx homologues not directly reduced by the only TrxR, revealing M. acetivorans has a diverse thioredoxin system, whereby the multiple and differentially-located Trx homologue are likely linked to different redox partners. The detailed understanding of the metabolism of M. acetivorans, combined with its genetic system, makes M. acetivorans a particularly attractive model to investigate what appears to be a complex thioredoxin system network in cytochrome-containing Methanomicrobia, when compared to cytochrome-lacking Methanococci and Methanobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phylogenetic analysis

123 Trx amino acid sequences were obtained from GenBank using their accession numbers provided by Sustani et al [12] and an additional 17 Trx amino acid sequences were included (see Table S1). The 140 Trx amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE [47], and columns in the alignment containing a fraction of gaps of 0.6 or greater were omitted using trimAl [48]. The trimmed alignment file was inputted into RAxML 7.3.1 [49] where a rapid bootstrap analysis was performed using 1,000 bootstrap replicates, 1,070,065 parsimony random seeds, and 3,535,411 rapid bootstrap random seeds. The best scoring maximum likelihood (ML) tree was obtained and bootstrap values greater than 50% were included on the nodes within the tree (Fig. S1). The resulting tree file from RAxML was pruned to 50 taxa using PAUP, and nodes with >50% support were reported (Fig. 1).

Cloning of M. acetivorans thioredoxin system genes

The genes encoding MaTrxR, MaTrx2, MaTrx6, MaTrx6ΔSp (deleted of signal peptide amino acids 1–30), and MaTrx7 (see Table 1 for gene designations) were PCR amplified using chromosomal DNA from M. acetivorans C2A as a template. All forward and reverse primers contained the restriction enzyme sites NdeI and BamHI respectively. Purified PCR products and the pET28a plasmid were digested with Nde1 and BamH1 for 16 hr at 37 °C. Digested PCR products and vector were ligated using T4 DNA ligase for 16 hr at 16 °C. Escherichia coli DH5α cells were transformed with the ligation reactions and cells containing plasmid were selected on LB agar containing 100 µg/mL kanamycin. Plasmids containing matrxR, matrx2, matrx6, matrx6ΔSp and matrx7 were verified by DNA sequencing and named pDL335, pDL331, pDL333, pDL332, and pDL336 respectively.

Purification of recombinant proteins

Proteins were expressed in E. coli Rosetta DE3 (pLacI) transformed with pDL335, pDL331, pDL332, pDL333, or pDL336. Each E. coli expression strain was grown in LB medium containing kanamycin (50 µg/mL) and chloramphenicol (17 µg/mL) at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5–0.7. Protein expression was induced with 500 µM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside and cultures were incubated at 25°C for 16 hr. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C.

For the purification of MaTrxs, cell pellets (2–4 g) were resuspended in 25–30 mL of buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl pH 8.0) containing a few crystals of DNaseI and benzamidine. Cells were lysed by three passes in a French pressure cell at a minimum of 100 MPa. Cell lysate was centrifuged at 41,000×g for 35 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing the expressed protein was filtered (pore size, 0.45 µm) and loaded by gravity flow onto a column containing 5 mL of Ni2+-agarose resin (Genscript). The column was then washed with 25 ml of buffer A three separate times with the second wash containing 10 mM imidazole. The column was then incubated in Buffer A containing 50 U of thrombin at 25 °C for 16 hr. Thrombin-cleaved protein was eluted from the column by the addition of 10 mL of buffer A. The eluate was passed through a 1 mL benzamidine column (GE Healthcare) to remove thrombin. The flowthrough was concentrated using a Vivacell concentrator (Sartorius) with a 5,000-Dalton molecular weight cutoff under nitrogen flow. The concentrated protein was desalted into buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.2) using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare). The desalted protein was stored at −80 °C.

For the purification of MaTrxR, cell lysate was prepared as described above, except that 10% glycerol was added to buffer A. The supernatant containing the expressed protein was filtered (pore size, 0.45 µm) and loaded by gravity flow onto a column containing 5 mL of Ni2+-agarose resin (Genscript). The column was washed with 25 mL of buffer A two separate times with the second wash containing 10 mM imidazole. Total bound protein was eluted from the column by two steps, first the addition of 10 mL of buffer A containing 75 mM imidazole, second by the addition of 10 mL of buffer A containing 150 mM imidazole. The eluates were combined and concentrated using a Vivacell concentrator with a 10,000-Dalton MW cutoff under nitrogen flow. The concentrated protein was desalted into buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol pH 7.2) using a PD-10 column and stored at −80 °C.

Reconstitution of MaTrxR with FAD was carried out by incubation of purified MaTrxR in buffer C containing 1 mM dithiothreitol and a 10 molar excess of FAD at 25 °C for 1 hr. The protein was desalted into buffer C using a NAP-5 column (GE Healthcare). Incorporation of FAD into MaTrxR was monitored by UV-visible spectroscopy and quantified based on the ratio of A280/A460.

Thioredoxin reductase activity assays

The ability of NADH and NADPH to reduce the FAD within MaTrxR was monitored by UV-visible spectroscopy before and after incubation of MaTrxR in buffer B with a >10-fold molar excess of either NADH or NADPH within an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratories). Reduction of DTNB by purified MaTrxR was monitored by the increase in absorbance at 412 nm using either NADPH or NADH as electron donors. The assays were performed anaerobically in buffer B containing 0.5 µM MaTrxR and 1 mM DTNB. The reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH (1–20 µM) or NADH (5–2000 µM). The concentration of TNB produced was calculated using ε412 =14,150 M−1 cm−1 [50]. The apparent kinetic constants were determined by nonlinear regression of Michaelis-Menten plots using Microsoft Excel with the XL_kinetics add-in. Measured activities in all assays were corrected for by subtracting the rates of control reactions without MaTrxR. Three independent assays were performed at each NADPH or NADH concentration.

NADH and NADPH oxidase activity of MaTrxR was measured spectrophotometrically by the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm in the presence of oxygen. Reactions contained 160 µM NADH or NADPH in buffer B. The reactions containing NADH as the electron donor contained 1 µM MaTrxR, while the NADPH-dependent reactions contained 100 nM MaTrxR. Oxidase activity of MaTrxR with each reductant was calculated using ε340 =6,220 M−1 cm−1.

The ability of MaTrxR to use F420H2 as an electron donor was examined with DTNB reduction assays. F420 purified from Mycobacterium smegmatis was provided as gift from Lacy Daniels (Texas A&M University, Kingsville). F420 was chemically reduced to F420H2 using sodium borohydride as previously described [51]. Assays were performed anaerobically in buffer A containing 0.5 µM MaTrxR and 1 mM DTNB, and were initiated by the addition of 50 µM F420H2.

Thioredoxin activity assays

Thioredoxin activity was determined by the turbidimeteric insulin reduction assay using DTT, lipoamide, glutathione, or coenzyme M as potential electron donors as described [26]. The standard assay mixture contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), 1 mM EDTA, 130 µM insulin, and up to 11 µM Trx. Standard assays contained 330 µM DTT, 660 µM glutathione or 660 µM coenzyme M, whereas lipoamide-dependent assays contained 50 µM lipoamide, 0.4 units of bovine lipoamide dehydrogenase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 500 µM NADH. Reactions were initiated by the addition of either reductant. An increase in the absorbance at 650 nm was monitored every 0.5 min. Activity was expressed as the ratio of the slope of a linear part of the turbidity curve to the lag time (reported as ΔA650/min2, 10−3), as described previously [52]. E. coli Trx1 (Sigma-Aldrich) was assayed for comparison.

MaTrxR-MaTrx interaction assays

MaTrxR activity with thioredoxin substrates was assayed using the turbidimetric insulin reduction assay. The assays were performed anaerobically in 400 µL containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), 1 mM EDTA, 130 µM insulin, 0.5 µM MaTrxR, and 5 or 10 µM Trx. Reactions were initiated by the addition of either NADH (1 mM) or NADPH (350 µM). An increase in the absorbance at 650 nm was monitored every 0.5 min.

MaTrxR-MaTrx7 kinetic parameters were obtained with assays that used oxidized glutathione as a substrate for thioredoxin as described [27]. The assays were performed anaerobically in buffer B containing 0.5 µM MaTrxR, 1 mM oxidized glutathione (Sigma Aldrich), and increasing amounts of MaTrx7. The reactions were initiated by the addition of NADPH (100 µM). Activity was monitored by the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm by the oxidation of NADPH (ε340=6,220 M−1 cm−1). The apparent kinetic constants were determined by nonlinear regression of Michaelis-Menten plots using Microsoft Excel with the XL_kinetics add-in.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grant number P30 GM103450 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (DJL), NSF grant number MCB1121292 (DJL), NASA Exobiology grant number NNX12AR60G (DJL), and the Arkansas Biosciences Institute (DJL), the major research component of the Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Proceeds Act of 2000. We thank Dr. Andy Alverson for technical assistance in the Trx phylogenetic analysis and Drs. Mack Ivey and Faith Lessner for critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DTNB

dithionitrobenzoate

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

- Trx

thioredoxin

- DTT

dithiothreitol

Footnotes

Author contribution. ACM, DJL planned experiments; ACM performed experiments; ACM, DJL analyzed data; ACM, DJL wrote the paper.

Supporting information

Table S1. Identification of additional thioredoxin homologues in the genomes of sequenced methanogens.

Figure S1. A phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood analysis of 140 Trx homologue sequences from sequenced methanogen genomes.

Figure S2. Amino acid sequence alignment of MaTrxs with Trx from E. coli (EcTrx1) and S. cerevisiae (ScTrx1).

Figure S3. Amino acid sequence alignment of TrxRs from Methanosarcinaceae with TrxR from E. coli (EcTrx1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyer Y, Buchanan BB, Vignols F, Reichheld JP. Thioredoxins and glutaredoxins: unifying elements in redox biology. Annual review of genetics. 2009;43:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free radical biology & medicine. 2014;66:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arner ES, Holmgren A. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6102–6109. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lillig CH, Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and related molecules--from biology to health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:25–47. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams CH, Arscott LD, Muller S, Lennon BW, Ludwig ML, Wang PF, Veine DM, Becker K, Schirmer RH. Thioredoxin reductase two modes of catalysis have evolved. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6110–6117. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toledano MB, Kumar C, Le Moan N, Spector D, Tacnet F. The system biology of thiol redox system in Escherichia coli and yeast: differential functions in oxidative stress, iron metabolism and DNA synthesis. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3598–3607. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer Y, Verdoucq L, Vignols F. Plant thioredoxins and glutaredoxins: identity and putative roles. Trends in plant science. 1999;4:388–394. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimaldi P, Ruocco MR, Lanzotti MA, Ruggiero A, Ruggiero I, Arcari P, Vitagliano L, Masullo M. Characterisation of the components of the thioredoxin system in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Extremophiles : life under extreme conditions. 2008;12:553–562. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0161-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon SJ, Ishikawa K. Identification and characterization of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase from Aeropyrum pernix K1. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5423–5430. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashima Y, Ishikawa K. A hyperthermostable novel protein-disulfide oxidoreductase is reduced by thioredoxin reductase from hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;418:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thauer RK, Kaster AK, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Susanti D, Wong JH, Vensel WH, Loganathan U, DeSantis R, Schmitz RA, Balsera M, Buchanan BB, Mukhopadhyay B. Thioredoxin targets fundamental processes in a methane-producing archaeon, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2608–2613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324240111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amegbey GY, Monzavi H, Habibi-Nazhad B, Bhattacharyya S, Wishart DS. Structural and functional characterization of a thioredoxin-like protein (Mt0807) from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8001–8010. doi: 10.1021/bi030021g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharyya S, Habibi-Nazhad B, Amegbey G, Slupsky CM, Yee A, Arrowsmith C, Wishart DS. Identification of a novel archaebacterial thioredoxin: determination of function through structure. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4760–4770. doi: 10.1021/bi0115176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee DY, Ahn BY, Kim KS. A thioredoxin from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii has a glutaredoxin-like fold but thioredoxin-like activities. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6652–6659. doi: 10.1021/bi000035b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon J, Hederstedt L. Composition and function of cytochrome c biogenesis System II. FEBS J. 2011;278:4179–4188. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo Z, Pohlschroder M. Diversity and subcellular distribution of archaeal secreted proteins. Frontiers in microbiology. 2012;3:207. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson JT, Wenger CD, Metcalf WW, Kelleher NL. Top-down proteomics reveals novel protein forms expressed in Methanosarcina acetivorans. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2009;20:1743–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessner DJ, Li L, Li Q, Rejtar T, Andreev VP, Reichlen M, Hill K, Moran JJ, Karger BL, Ferry JG. An unconventional pathway for reduction of CO2 to methane in CO-grown Methanosarcina acetivorans revealed by proteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17921–17926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608833103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Li Q, Rohlin L, Kim U, Salmon K, Rejtar T, Gunsalus RP, Karger BL, Ferry JG. Quantitative proteomic and microarray analysis of the archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans grown with acetate versus methanol. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:759–771. doi: 10.1021/pr060383l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams CH, Jr, Zanetti G, Arscott LD, McAllister JK. Lipoamide dehydrogenase, glutathione reductase, thioredoxin reductase, and thioredoxin. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:5226–5231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruggiero A, Masullo M, Ruocco MR, Grimaldi P, Lanzotti MA, Arcari P, Zagari A, Vitagliano L. Structure and stability of a thioredoxin reductase from Sulfolobus solfataricus: a thermostable protein with two functions. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1794:554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruocco MR, Ruggiero A, Masullo L, Arcari P, Masullo M. A 35 kDa NAD(P)H oxidase previously isolated from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus is instead a thioredoxin reductase. Biochimie. 2004;86:883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang X, Ma K. Characterization of a thioredoxin-thioredoxin reductase system from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1370–1376. doi: 10.1128/JB.01035-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obiero J, Sanders DA. Design of Deinococcus radiodurans thioredoxin reductase with altered thioredoxin specificity using computational alanine mutagenesis. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1021–1029. doi: 10.1002/pro.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin catalyzes the reduction of insulin disulfides by dithiothreitol and dihydrolipoamide. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9627–9632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanzok SM, Rahlfs S, Becker K, Schirmer RH. Thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, and thioredoxin peroxidase of malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Methods Enzymol. 2002;347:370–381. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)47037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira MA, Discola KF, Alves SV, Medrano FJ, Guimaraes BG, Netto LE. Insights into the specificity of thioredoxin reductase-thioredoxin interactions. A structural and functional investigation of the yeast thioredoxin system. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3317–3326. doi: 10.1021/bi901962p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fahey RC. Novel thiols of prokaryotes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:333–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McFarlan SC, Terrell CA, Hogenkamp HP. The purification, characterization, and primary structure of a small redox protein from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, an archaebacterium. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10561–10569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ondarza RN, Rendon JL, Ondarza M. Glutathione reductase in evolution. Journal of molecular evolution. 1983;19:371–375. doi: 10.1007/BF02101641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galagan JE, Nusbaum C, Roy A, Endrizzi MG, Macdonald P, FitzHugh W, Calvo S, Engels R, Smirnov S, Atnoor D, Brown A, Allen N, Naylor J, Stange-Thomann N, DeArellano K, Johnson R, Linton L, McEwan P, McKernan K, Talamas J, Tirrell A, Ye W, Zimmer A, Barber RD, Cann I, Graham DE, Grahame DA, Guss AM, Hedderich R, Ingram-Smith C, Kuettner HC, Krzycki JA, Leigh JA, Li W, Liu J, Mukhopadhyay B, Reeve JN, Smith K, Springer TA, Umayam LA, White O, White RH, Conway de Macario E, Ferry JG, Jarrell KF, Jing H, Macario AJ, Paulsen I, Pritchett M, Sowers KR, Swanson RV, Zinder SH, Lander E, Metcalf WW, Birren B. The genome of Methanosarcina acetivorans reveals extensive metabolic and physiological diversity. Genome Res. 2002;12:532–542. doi: 10.1101/gr.223902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rother M, Metcalf WW. Anaerobic growth of Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A on carbon monoxide: an unusual way of life for a methanogenic archaeon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16929–16934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407486101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, Li L, Rejtar T, Karger BL, Ferry JG. Proteome of Methanosarcina acetivorans Part II: comparison of protein levels in acetate- and methanol-grown cells. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:129–135. doi: 10.1021/pr049831k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferry JG. Enzymology of one-carbon metabolism in methanogenic pathways. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:13–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wohlbrand L, Jacob JH, Kube M, Mussmann M, Jarling R, Beck A, Amann R, Wilkes H, Reinhardt R, Rabus R. Complete genome, catabolic sub-proteomes and key-metabolites of Desulfobacula toluolica Tol2, a marine, aromatic compound-degrading, sulfate-reducing bacterium. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:1334–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fournier GP, Gogarten JP. Evolution of acetoclastic methanogenesis in Methanosarcina via horizontal gene transfer from cellulolytic Clostridia. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1124–1127. doi: 10.1128/JB.01382-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson-Sathi S, Dagan T, Landan G, Janssen A, Steel M, McInerney JO, Deppenmeier U, Martin WF. Acquisition of 1,000 eubacterial genes physiologically transformed a methanogen at the origin of Haloarchaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:20537–20542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209119109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berk H, Thauer RK. Function of coenzyme F420-dependent NADP reductase in methanogenic archaea containing an NADP-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:396–402. doi: 10.1007/s002030050514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berk H, Thauer RK. F420H2:NADP oxidoreductase from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum: identification of the encoding gene via functional overexpression in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:124–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terlesky KC, Ferry JG. Ferredoxin requirement for electron transport from the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase complex to a membrane-bound hydrogenase in acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4075–4079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aliverti A, Pandini V, Pennati A, de Rosa M, Zanetti G. Structural and functional diversity of ferredoxin-NADP(+) reductases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S, Huang H, Moll J, Thauer RK. NADP+ reduction with reduced ferredoxin and NADP+ reduction with NADH are coupled via an electron-bifurcating enzyme complex in Clostridium kluyveri. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5115–5123. doi: 10.1128/JB.00612-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buckel W, Thauer RK. Energy conservation via electron bifurcating ferredoxin reduction and proton/Na(+) translocating ferredoxin oxidation. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1827:94–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Q, Li L, Rejtar T, Lessner DJ, Karger BL, Ferry JG. Electron transport in the pathway of acetate conversion to methane in the marine archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:702–710. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.702-710.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang M, Tomb JF, Ferry JG. Electron transport in acetate-grown Methanosarcina acetivorans. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riddles PW, Blakeley RL, Zerner B. Reassessment of Ellman's reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deppenmeier U, Blaut M, Mahlmann A, Gottschalk G. Reduced coenzyme F420: heterodisulfide oxidoreductase, a proton- translocating redox system in methanogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9449–9453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lessner DJ, Ferry JG. The Archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans Contains a Protein Disulfide Reductase with an Iron-Sulfur Cluster. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7475–7484. doi: 10.1128/JB.00891-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]