Abstract

Background

Schwannoma is a tumor that develops on peripheral nerves or spinal roots. Although any part of the body can be affected, axillar and supraclavicular lesions are unusual for schwannoma. We report two cases of schwannoma arising in the brachial plexus, which were detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT).

Case 1

A 75-year-old Japanese woman showed high FDG accumulation in a subclavicular or axillary lesion found by FDG-PET/CT. Axillar-subclavicular lymph node metastasis was suspected and surgical excision was performed. Histological evaluation revealed schwannoma.

Case 2

A 75-year-old Japanese woman was diagnosed with suspected primary lung cancer with brain metastases. She showed high FDG uptake at a subclavicular or axillary lesion found by FDG-PET/CT. Surgical excision was performed to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. The mass was located at the trunk of the brachial plexus and was identified as a schwannoma.

Conclusion

Although schwannoma within an axillar or subclavicular lesion is relatively rare, brachial plexus schwannoma should be considered in the diagnosis of masses detected by FDG-PET/CT.

Keywords: FDG-PET, lymph node metastasis, schwannoma

Background

Schwannoma is a relatively rare neoplasm that arises from Schwann cells of the peripheral nerve sheath [1–3]. Although schwannoma may occur in any organ, including the extremities, trunk and head, it rarely appears as an axillar or supraclavicular lesion.

In recent years, there has been an explosive increase in the use of positron emission tomography (PET) in clinical applications. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET is a noninvasive whole-body imaging technique used to evaluate various kinds of malignancy, including colorectal cancer and lung cancer, as well as for tumor staging, restaging, and detection of recurrence, and for monitoring treatment response [4–8]. The FDG-PET technique also has the potential to detect malignant tumors in asymptomatic individuals [9–11]. However, schwannomas generally show high FDG uptake [12–14]. We report here two cases of schwannoma arising in the brachial plexus detected by FDG-PET and initially suspected to be axillar or subclavicular lymph node metastasis.

Case presentation

Case 1

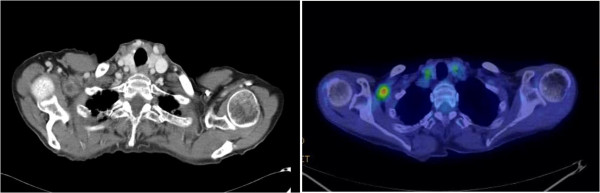

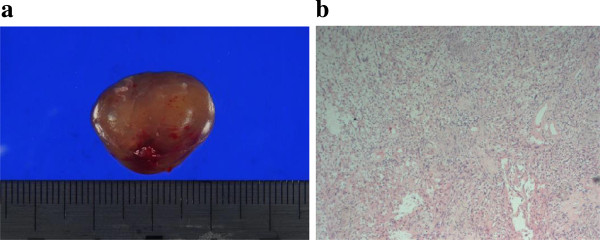

A 75-year-old Japanese woman was referred to our hospital after high accumulation in a subclavicular or axillary lesion was found by FDG-PET and computed tomography (CT) (SUVmax 3.4) (Figure 1). She had been diagnosed with early rectal cancer and a laparoscopic low anterior resection had been performed 14 months previously. Axillar or subclavicular lymph node metastasis from carcinoma was suspected, but the differential diagnosis of a solid mass with FDG uptake by PET/CT in axillar or subclavicular lesions includes malignant lymphoma, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and other infections. For treatment and diagnosis, surgical excision was therefore performed. The tumor was located at the trunk of the brachial plexus, and was identified as a schwannoma. Histological evaluation revealed an encapsulated mass composed of spindle-shaped cells with pointed basophilic nuclei and with nuclear palisading arranged in interlacing bundles known as Verocay bodies (Figure 2). Neither malignancy of the proliferative cells nor invasion was observed. These findings are compatible with schwannoma. Our follow-up of the patient has remained uneventful without postoperative neurological disturbance.

Figure 1.

18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography revealed a mass with abnormal uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose in the right axillary to subclavicular region.

Figure 2.

Histological evaluation. (a) Macroscopic view. The tumor is an encapsulated mass with a soft and elastic consistency. (b) Histological evaluation revealed an encapsulated mass composed of spindle-shaped cells with pointed basophilic nuclei and with nuclear palisading arranged in interlacing bundles known as Verocay bodies.

Case 2

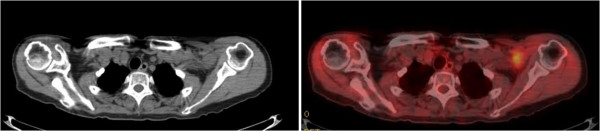

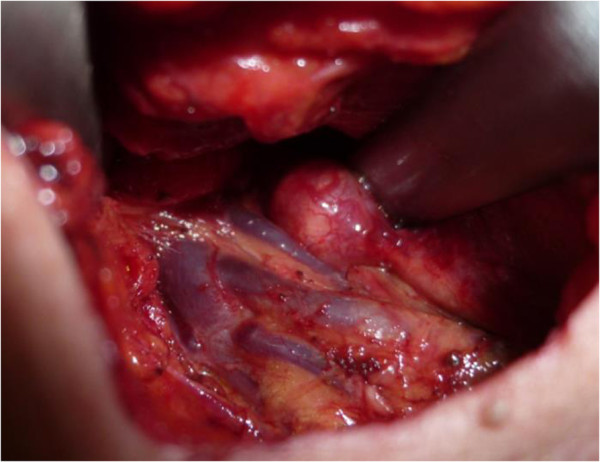

A 75-year-old Japanese woman showed an abnormal shadow in the right lung and multiple masses in the brain, suggesting primary lung cancer with brain metastases. She showed high FDG uptake in a subclavicular or axillary lesion found by FDG-PET/CT (SUVmax 2.6) (Figure 3), and the SUVmax of the lung masses was 2.7. Thus, axillar or subclavicular lymph node metastasis was suspected and surgical excision was performed to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. The mass was located at the trunk of the brachial plexus, and was identified as a schwannoma (Figure 4). Surgical resection was not performed because injury to the brachial plexus sometimes leads to postoperative neurological disturbance. In this case, because findings at the surgery indicated that the mass was located at the trunk of the brachial plexus, strongly suggesting schwannoma, we did not perform resection. The patient was diagnosed with primary lung cancer by thoracoscopic surgery.

Figure 3.

18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography revealed a mass with abnormal uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose in the left axillary to subclavicular region.

Figure 4.

The mass was located at the trunk of the brachial plexus, and was identified as a schwannoma.

Discussion

The FDG-PET technique has been widely used with high accuracy for staging and identifying recurrence in various types of cancer [15, 16]. Ueda et al. demonstrated that the diagnostic accuracy of FDG-PET/CT for axillary lymph node metastasis in cases with breast cancer was 83%, with 58% sensitivity and 95% specificity [17]. Thus, the false-positive diagnostic rate of FDG-PET/CT appears to be low and FDG-PET is useful for the detection and localization of schwannoma [12–14]. Schwannoma is a tumor that develops on peripheral nerves or spinal roots [1]. The most common locations are the neck, head, extensor surfaces of the extremities, posterior mediastinum, and stomach [2, 3], while axillar and supraclavicular lesions are unusual [16, 18, 19]. The differential diagnosis of a solid mass with FDG uptake by PET/CT in axillar or subclavicular lesions includes lymph node metastasis from carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and other infections. The distinction of schwannoma in axillary or subclavicular lesions from lymph node metastasis may be difficult. Previous reports have discussed schwannoma cases misdiagnosed as axillary node metastasis in breast cancer patients [18, 19]. In the present cases, PET/CT also failed to distinguish schwannoma from lymph node metastasis. Schwannoma arising in the brachial plexus should be included in the differential diagnosis of masses in the axillar or subclavicular region detected by FDG-PET. Supraclavicular lymph node metastasis is often encountered in patients with lung cancer; however, axillary lymph node metastasis from lung cancer or colon cancer appears to be very rare [20, 21], and the status of the primary lesion should be taken into consideration for the diagnosis.

In Case 2, we did not resect the mass. In cases of schwannoma, resection is performed only if the lesion is symptomatic, moderately large, or exhibits rapid growth. Furthermore, it is necessary to pay close attention to irreversible complications that may arise from resection in the brachial plexus. In this case, because findings during surgery indicated that the mass was located at the trunk of the brachial plexus, strongly suggesting schwannoma, in conjugation with the findings and experience of Case 1, we did not perform resection. When a connection with the brachial plexus is confirmed, resection should be avoided if there are no symptoms.

Conclusion

We report two cases of schwannoma arising in the brachial plexus and mimicking lymph node metastasis, identified by FDG-PET/CT. Although schwannoma in an axillar or subclavicular lesion is relatively rare, brachial plexus schwannoma should be considered in the diagnosis of masses detected by FDG-PET.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Saitoh Y, Yano T, Matsui Y, Ishida A, and Ishikubo A for their secretarial assistance.

Abbreviations

- CT

computed tomography

- FDG

18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose

- PET

positron emission tomography.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TF designed the study, provided the collection of the data of the patients and wrote the manuscript; RY, HM, SY, ST, TA provided the collection of all the human material; HK involved in editing the manuscript. This manuscript was read and approved the submission by all co-authors.

Contributor Information

Takaaki Fujii, Email: ftakaaki@med.gunma-u.ac.jp.

Reina Yajima, Email: reinawat5507@yahoo.co.jp.

Hiroki Morita, Email: h-morita@med.gunma-u.ac.jp.

Satoru Yamaguchi, Email: syamaguc@dokkyomed.ac.jp.

Soichi Tsutsumi, Email: chuchumi@gunma-u.ac.jp.

Takayuki Asao, Email: asao@gunma-u.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Kuwano, Email: hkuwano@med.gunma-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD, Strong EW, Hjdu SI. Benign solitary schwannomas (neurilemomas) Cancer. 1969;24(2):355–366. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196908)24:2<355::AID-CNCR2820240218>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchida N, Yokoo H, Kuwano H. Schwannoma of the breast: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35(3):238–242. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2904-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dialani V, Hines N, Wang Y, Slanetz P. Breast schwannoma. Case Report Med. 2011;2011:930841. doi: 10.1155/2011/930841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kresnik E, Gallowitsch HJ, Mikosch P, Stettner H, Igerc I, Gomez I, Kumnig G, Lind P. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the preoperative assessment of thyroid nodules in an endemic goiter area. Surgery. 2003;133:294–299. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y. Clinical significance of thyroid uptake on F18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher JW, Djulbegovic B, Soares H, Siegel BA, Lowe VJ, Lyman GH, Coleman RE, Wahl R, Paschold JC, Avril N, Einhorn LH, Suh WW, Samson D, Delbeke D, Gorman M, Shields AF. Recommendations on the use of 18F-FDG PET in oncology. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:480–508. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor OJ, McDermott S, Slattery J, Sahani D, Blake MA. The use of PET-CT in the assessment of patients with colorectal carcinoma. Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:846512. doi: 10.1155/2011/846512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haoping X, Zhang M, Zhai G, Li B. The clinical significance of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in early detection of second primary malignancy in cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:1125–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda S, Ide M, Fujii H, Nakahara T, Mochizuki Y, Takahashi W, Shohtsu A. Application of positron emission tomography imaging to cancer screening. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1607–1611. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen YY, Su CT, Chen GJ, Chen YK, Liao AC, Tsai FS. The value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with the additional help of tumor markers in cancer screening. Neoplasma. 2003;50:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii T, Yajima R, Yamaguchi S, Tsutsumi S, Asao T, Kuwano H. Is it possible to predict malignancy in cases with focal thyroid incidentaloma identified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography? Am Surg. 2012;78:141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohno T, Ogata K, Kogure N, Ando H, Aihara R, Mochiki E, Zai H, Sano A, Kato T, Sakurai S, Oyama T, Asao T, Kuwano H. Gastric schwannomas show an obviously increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in positron emission tomography: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2011;41:1133–1137. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed AR, Watanabe H, Aoki J, Shinozaki T, Takagishi K. Schwannoma of the extremities: the role of PET in preoperative planning. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1541–1551. doi: 10.1007/s002590100584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaulieu S, Rubin B, Diang D, Conrad E, Turcotte E, Eary JF. Positron emission tomography of schwannomas: emphasizing its potential in preoperative planning. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:971–974. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.4.1820971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blodgett TM, Meltzer CM, Townsend DW. PET/CT: form and function. Radiology. 2007;242:360–385. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiuchi N, Saeki T, Takeuchi H, Sano H, Takahashi T, Matsuura K, Shigekawa T, Misumi M, Nakamiya N, Okubo K, Osaki A, Sakurai T, Matsuda H. A false positive for metastatic lymph nodes in the axillary region of a breast cancer patient following mastectomy. Breast Cancer. 2007;18:141–144. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ueda S, Tsuda H, Asakawa H, Omata J, Fukatsu K, Kondo N, Kondo T, Hama Y, Tamura K, Ishida J, Abe Y, Mochizuki H. Utility of 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose emission tomography/computed tomography fusion imaging (18F-FDG PET/CT) in combination with ultrasonography for axillary staging in primary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sohn YM, Kim SY, Kim EK. Sonographic appearance of a schwannoma mimicking an axillary lymphadenopathy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39:477–479. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura M, Akao S. Neurilemmoma arising in the brachial plexus in association with breast cancer: report of case. Surg Today. 2000;30:1012. doi: 10.1007/s005950070023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Kagohashi K, Kurishima K, Sekizawa K. Axillary lymph node metastasis in lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2009;26:147–150. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chieco PA, Virgilio E, Mercantini P, Lorenzon L, Caterino S, Ziparo V. Solitary left axillary metastasis after curative surgery for right colon cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:846–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2011.05869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]