Historically, the hair follicle bulge was thought to contain the sole population of epidermal stem cells. But in recent years, stem cell pools outside the bulge have been identified, and each expresses distinct markers.

Abstract

The epidermis is the outermost layer of mammalian skin and comprises a multilayered epithelium, the interfollicular epidermis, with associated hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and eccrine sweat glands. As in other epithelia, adult stem cells within the epidermis maintain tissue homeostasis and contribute to repair of tissue damage. The bulge of hair follicles, where DNA-label-retaining cells reside, was traditionally regarded as the sole epidermal stem cell compartment. However, in recent years multiple stem cell populations have been identified. In this review, we discuss the different stem cell compartments of adult murine and human epidermis, the markers that they express, and the assays that are used to characterize epidermal stem cell properties.

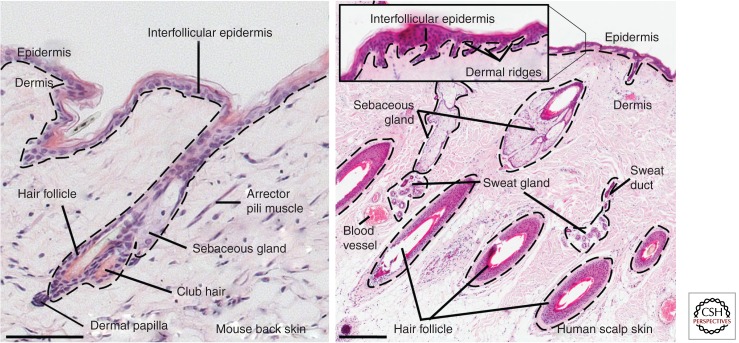

Mammalian skin comprises of two distinct layers—the epidermis and the underlying dermis (Fig. 1). As the skin's outer layer, the epidermis provides the barrier function protecting mammals from environmental influences such as physical, chemical, or thermal stress, and also against dehydration (Proksch et al. 2008; Fuchs 2009). The epidermis is a multilayered epithelium consisting of the interfollicular epidermis (IFE) and associated hair follicles (HFs), sebaceous glands (SGs), and eccrine sweat glands. Keratinocytes are the main epidermal cell type. Several other cell types, such as Merkel cells, melanocytes, and Langerhans cells, are also found in mammalian epidermis. Merkel cells are neuroendocrine cells that lie in so-called touch domes within the IFE and are responsible for the touch sensory function of the skin (Van Keymeulen et al. 2009; Woo et al. 2010). Melanocytes are specialized pigment cells that produce melanin granules, which are taken up by keratinocytes and protect against sunlight-induced DNA damage (Rabbani et al. 2011; Chang et al. 2013). Langerhans cells, which are epidermal dendritic cells, are part of the adaptive immune response and, hence, a critical element of the skin barrier (Romani et al. 2010).

Figure 1.

Histology of mammalian skin. Adult mouse (left) and human skin (right) stained with hematoxylin. Note the absence of eccrine sweat glands in mouse back skin. Dashed lines indicate position of the basement membrane. Scale bars, 100 µm (mouse skin) and 500 µm (human skin).

A basement membrane separates the epidermis from the underlying collagen-rich dermis (Watt and Fujiwara 2011). The dermis plays an important role in epidermal development (Alonso and Fuchs 2006; Blanpain and Fuchs 2009), as epidermal–dermal interactions are, for example, critical for HF formation during embryogenesis (Messenger 1993; Botchkarev and Kishimoto 2003). Each region of the dermis contains fibroblasts, some of which have specialized functions, for example, in the dermal papilla (DP). DP cells stimulate epidermal cells to grow downward and form the HF (Alonso and Fuchs 2006; Driskell et al. 2011). The DP remains an integral part of the HF base throughout the hair cycle (Messenger 1993; Botchkarev and Kishimoto 2003; Alonso and Fuchs 2006). Several other cell types, such as nerves, lymphatic cells, endothelial cells, as well as different types of bone-marrow-derived immune cells (e.g., macrophages, mast cells, T, and B cells), are also present in the dermis (Kalluri and Zeisberg 2006; Arwert et al. 2012). The arrector pili muscle is a smooth muscle resident in the dermis connecting the HF with the IFE and is responsible for piloerection (“goosebumps”) to prevent heat loss (Fujiwara et al. 2011). The subcutaneous fat layer is formed by intradermal adipocytes (Schmidt and Horsley 2012). Skin adipocytes play a role in the regulation of HF cycling (Festa et al. 2011).

Because the differentiated cells of the epidermis are dead, frequently anucleate cells, epidermal maintenance depends on proliferation of stem cells, which are cells with an extensive self-renewal capacity and the ability to produce daughter cells that undergo further differentiation. Stem cells have been identified in human non-hair-bearing skin (Barrandon and Green 1987; Jones and Watt 1993). However, historically, in the mouse, epidermal maintenance was attributed to a single population of epidermal stem cells residing in a compartment of the lower HF known as the bulge (Cotsarelis 2006; Blanpain and Fuchs 2009), where the arrector pili muscle contacts the HF basement membrane (Fujiwara et al. 2011). This view has changed over the last decade as evidence of stem cell pools outside the bulge has accumulated. In this review, we will focus on the different epidermal stem cell subpopulations identified in human and murine skin.

TOOLS TO STUDY EPIDERMAL STEM CELLS

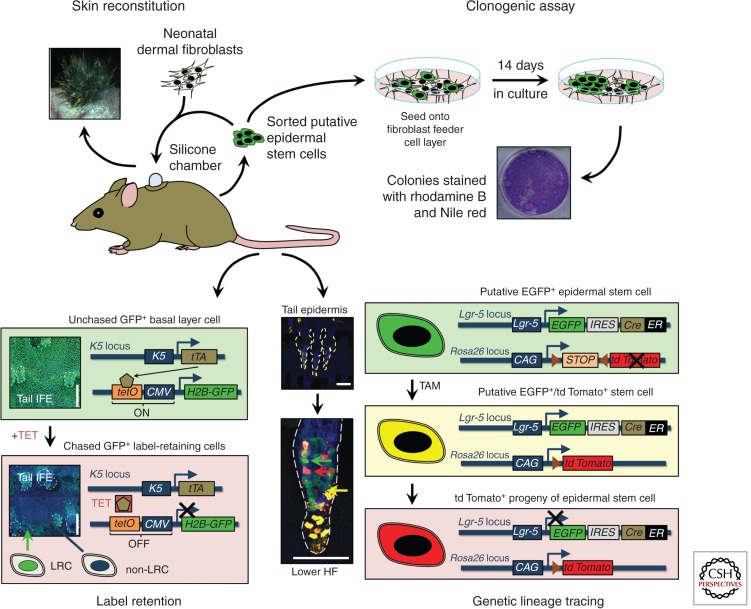

Different assays have been developed to study adult epidermal stem cells. As these tools have recently been extensively reviewed (Fuchs and Horsley 2011; Snippert and Clevers 2011; Kretzschmar and Watt 2012), we will only give an overview of the four major techniques used in epidermal stem cell research (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Strategies to study epidermal stem cells and their markers. Disaggregated epidermal cells can be either mixed with neonatal murine dermal fibroblasts and grafted onto immunocompromised mice to study their skin reconstitution potential in vivo or they can be seeded onto a feeder cell layer to study their clonogenic potential in culture. Slowly cycling cells in vivo can be identified through DNA label retention, either by injecting nucleotide labels such as 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) or by using genetic approaches such as the tetracycline-regulated H2B-GFP system. (Images based on data from Mascre et al. 2012; reproduced, with permission, from C. Blanpain and Nature © 2012, Macmillan.) Genetic lineage tracing enables fate mapping of epidermal stem cells and their progeny during tissue homeostasis. CAG, chicken β-actin promoter with CMV enhancer; CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter; EGFP, enhanced GFP; ER, tamoxifen-inducible mutated estrogen receptor; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HF, hair follicle; H2B, histone H2B; IFE, interfollicular epidermis; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; K, keratin; LRC, label-retaining cell; TAM, tamoxifen; TET, tetracycline; tetO, tetracycline operator; tTA, tetracycline transactivator. Scale bars, 100 µm.

Label Retention

A dogma established by pioneers of hemopoietic stem cell research is that adult stem cells are infrequently dividing (slowly cycling), quiescent cells, which therefore retain radioactively labeled nucleotides, such as tritiated thymidine or 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (Till and McCulloch 1961). In skin, such cells—so-called label-retaining cells (LRCs)—were identified in the HF bulge by DNA-label pulse-chase experiments (Cotsarelis et al. 1990; Braun et al. 2003). A major drawback of this technique is that certain types of postmitotic terminally differentiated cells efficiently retain DNA labels and remain in the tissue for a long period of time (Snippert and Clevers 2011; Steinhauser et al. 2012). To enable isolation of live LRCs using flow cytometry, Fuchs and colleagues elegantly adapted the pulse-chase technique to visualize LRCs using green fluorescent protein tagged histone (H2BGFP), which is tetracycline-dependent and expressed in a tissue-specific manner (Tumbar et al. 2004). This approach has now been used extensively and has generated important insights into epidermal LRC, although one potential caveat—found when using the H2BGFP transgenic mouse model to isolate hematopoietic stem cells—is leaky transgene expression (Challen and Goodell 2008).

Clonogenic Assays

One of the earliest approaches to identify adult human epidermal stem cells was to isolate cells from tissue and culture them in vitro. A subpopulation of the cells that attached proliferated to form large colonies that, at confluence, merged to form a stratified epidermal cell sheet (Rheinwald and Green 1975). Cultured epidermal sheets have been used extensively as autografts to treat burns victims, establishing that stem cells survive in culture (Green 2008). Formation of self-renewing clones has been used as an in vitro readout of stem cells, first in human epidermis and subsequently in mice (Barrandon and Green 1987; Jones and Watt 1993; Morris and Potten 1994).

Skin Reconstitution

Adult stem cells are defined not only by their capacity to self-renew, but also by their potential to produce all types of differentiated cells within their tissue (multipotency). This can be assessed by performing skin reconstitution assays in which repair of a skin wound or reconstitution from disaggregated cell populations is evaluated (Jensen et al. 2010).

Genetic Lineage Tracing

The first description of genetically modified mice laid the foundation for many powerful approaches in stem cell biology (Jaenisch and Mintz 1974). Lineage tracing using the Cre-loxP system (Hoess and Abremski 1984; Kretzschmar and Watt 2012) enables genetic labeling of stem cells and their progeny in intact, undamaged tissue using fluorescent and other reporters (Zinyk et al. 1998).

The first report of lineage tracing in mouse skin involved a transgenic mouse harboring Cre recombinase fused to a tamoxifen-inducible mutated estrogen receptor expressed under the control of the epidermal basal layer-specific keratin 14 promoter (K14CreERt) (Vasioukhin et al. 1999). This mouse line was crossed with a mouse ubiquitously expressing an inactive LacZ reporter flanked by a loxP-STOP-loxP sequence (Rosa26reporter, Rosa26R) (Soriano 1999). On topical application of tamoxifen (or its active metabolite 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen, 4-OHT) to double transgenic mice, Cre recombines the loxP sites thereby excising the STOP sequence and permanently (genetically) activating LacZ expression in K14+ cells. When these cells divide, the genetically recombined and active LacZ reporter is passed onto all their progeny. The label can be visualized by assaying for β-galactosidase (β-gal), and, thus Vasioukhin et al. (1999) were able to show that the K14+ basal layer of murine epidermis contained β-gal+ stem cells that give rise to β-gal+ differentiating suprabasal cells. Subsequently, mice expressing fluorescent reporters, such as enhanced green fluorescent protein (Rosa26EGFP) (Mao et al. 2001), enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (Rosa26EYFP), enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (Rosa26ECFP) (Srinivas et al. 2001), tdTomato (R26tdTomato) (Madisen et al. 2010), and multicolor confetti (Rosa26Confetti) (Snippert et al. 2010b), as well as bicistronic knock-in mice carrying CreERT2 combined with a fluorescent marker (e.g., EGFP) (Barker et al. 2007) have been introduced. These have led to even more sophisticated approaches to fate map epidermal stem cells. However, it is important to carefully assess each mouse model used for lineage tracing to exclude possible compartmental or spatiotemporal misexpression of the promoter driving Cre recombinase (Snippert and Clevers 2011; Kretzschmar and Watt 2012).

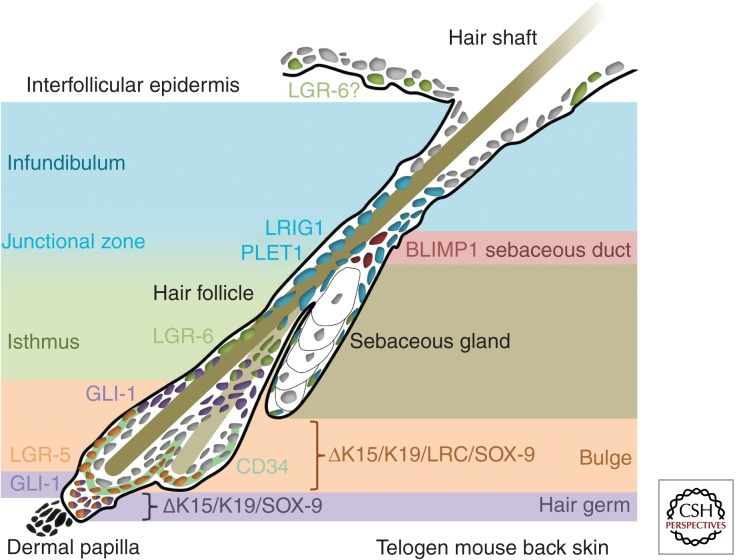

Studies have used a combination of these techniques to define the location and features of adult epidermal stem cells (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Markers of epidermal stem cell subpopulations in murine adult skin. Schematic of epidermal stem cell pools in murine telogen (hair follicle resting phase) back skin.

STEM CELLS OF THE HAIR FOLLICLE BULGE AND GERM

In murine skin, bulge stem cells in the lower HF were initially identified through DNA or histone label-retention studies (Cotsarelis et al. 1990; Braun et al. 2003; Tumbar et al. 2004). Slowly cycling and therefore label-retaining stem cells are almost entirely localized to the bulge region and are only rarely found elsewhere within the epidermal basal layer (Braun et al. 2003). This might reflect the fact that the lower HF compartment is not continuously regenerated, but subject to cycles of hair growth, regression, and rest. In contrast, actively cycling stem cells in the permanent portion of the epidermis (comprising the upper HF, SG, and IFE) are required to ensure a continuous supply of differentiated progeny (Watt and Jensen 2009).

Over the last decade, several groups have identified markers of the HF bulge stem cell niche in mouse and human skin. Clusters of differentiation 34 (CD34) and keratin 15 (K15) are the most widely used markers of murine bulge stem cells. CD34+ bulge cells are infrequently dividing and label retaining as well as able to self-renew in culture to form colonies (Trempus et al. 2003). Significant overlap is found between expression of CD34 and K15 (Lyle et al. 1998), which is expressed at low levels throughout the epidermal basal layer and enriched in the bulge (Troy et al. 2011; Xiao et al. 2013). There are two distinct layers of CD34+ bulge stem cells (Blanpain et al. 2004), one of which expresses high levels of α6 integrin and is attached to the basement membrane, whereas the other, which appears only after the first hair cycle, is suprabasal and expresses low levels of α6 integrin (Blanpain et al. 2004).

A truncated version of the human K15 promoter (K15) has been used to specifically target the bulge stem cell population (Morris et al. 2004). Lineage tracing showed that K15-targeted cells contribute to all epidermal lineages during normal HF cycling. By expressing EGFP under the control of the K15 promoter, it was shown that EGFP+/α6 integrin+ keratinocytes are slowly cycling in vivo and have high proliferative potential in culture (Morris et al. 2004). Also, in skin reconstitution assays, sorted K15EGFP expressing cells were able to generate all epidermal compartments, suggesting that this cell population is indeed multipotent, notwithstanding the caveat that founder line integration site and copy number can lead to nonbulge expression of this promoter (Petersson et al. 2011).

A new transgenic mouse founder line with low expression levels of K15CreERT2 was recently created, which may enable more specific tracking of bulge stem cell progeny (Petersson et al. 2011). In this model, there is labeling of SG and upper HF within 5 d after Cre reporter activation, suggesting a contribution of K15 expressing bulge cells, in agreement with previous studies (Morris et al. 2004). However, no trail of labeled progeny connecting the bulge with the upper HF and SG was observed, and, additionally, Cre expressing cells were found in the isthmus region of the upper HF (Petersson et al. 2011), preventing firm conclusions to be drawn about the contribution of bulge stem cells to the normal homeostasis of the upper HF and SG. Studies using K19CreERT mice to target the bulge have failed to show labeling of the upper HF and SG (Morris et al. 2004; Youssef et al. 2010; Lapouge et al. 2011).

SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 9 (SOX-9) is another marker of the bulge stem cell compartment (Vidal et al. 2005; Nowak et al. 2008). SOX-9 is expressed in the developing hair placodes at embryonic day (E) 15.5 and marks slowly cycling and CD34+ HF stem cells that give rise to the entire pilosebaceous unit (Vidal et al. 2005; Nowak et al. 2008). Using two different transgenic mouse lines expressing epithelial-specific Cre (Y10Cre and K14Cre) transgenes, it has been shown that conditional deletion of Sox-9 causes alopecia and loss of the SG (Vidal et al. 2005; Nowak et al. 2008). Mice with epidermal-specific loss of Sox-9 lack postnatal expression of crucial bulge markers such as CD34 and K15 and show complete loss of label-retaining bulge cells and actively cycling matrix cells during hair morphogenesis in neonates. These data indicate that Sox-9 is a functional stem cell marker that is indispensable for hair homeostasis (Vidal et al. 2005; Nowak et al. 2008).

Over the past decade, several other functional bulge stem cell markers have been described, such as transcription factor 3 (TCF-3) (Nguyen et al. 2006), LIM homeobox 2 (LHX2) (Rhee et al. 2006), and nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic 1 (NFATC1) (Horsley et al. 2008). Recently, Fuchs and colleagues have performed in utero screens for transcription factors that regulate HF stem cells using a knockdown approach with RNA interference (Chen et al. 2012). One of the markers identified is T-box 1 (TBX1), which is highly enriched in the bulge of developing and cycling HFs (Chen et al. 2012). Epidermal deletion of Tbx1 causes loss of the entire lower HF following multiple rounds of hair regeneration, while the IFE, SG, and upper HF remain phenotypically normal, suggesting that only the HF bulge stem cell pool—where Tbx1 is expressed—is exhausted (Chen et al. 2012).

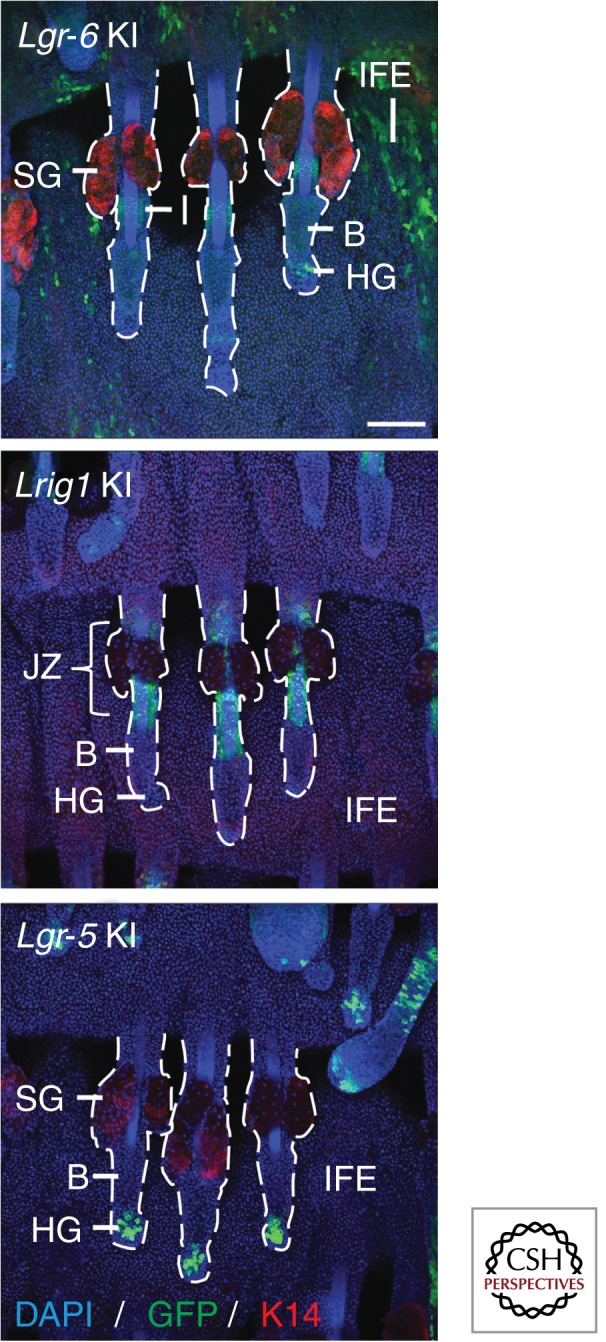

Since its first description as a marker of stem cells in the crypt base of the murine small intestine, leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR-5) has been shown to be a marker of adult stem cells in numerous epithelial tissues (Barker et al. 2007, 2010; Huch et al. 2013). In skin, LGR-5 marks stem cells in the lower HF bulge and hair germ during telogen and in the lower outer root sheath during anagen (Fig. 4) (Jaks et al. 2008). During telogen, the hair germ is quiescent, like the bulge, but at the onset of anagen, it is the first compartment of the lower HF to be triggered to proliferate (Greco et al. 2009; Rompolas et al. 2012). Toftgård and coworkers found that LGR-5+ stem cells are the first HF cells to proliferate upon Wnt-dependent induction of anagen and contribute to HF maintenance during adult homeostasis (Jaks et al. 2008). Interestingly, some LGR-5+ cells in the lower outer root sheath of anagen HFs are not lost during later catagen, but remain in the hair germ and contribute to HF growth during the next anagen, suggesting that these hair germ cells retain stem cell properties similar to conventional bulge stem cells (Jaks et al. 2008; Hsu et al. 2011). One model to explain these findings is that there is bicompartmentalization within the lower HF, whereby the HF bulge contains a pool of quiescent stem cells, which act as a reserve cell population and only become activated to replace the loss of rapidly cycling stem cell residing in the hair germ during periods of hair growth (Jaks et al. 2008; Greco et al. 2009; Greco and Guo 2010; Zhang et al. 2010; Hsu et al. 2011).

Figure 4.

Genetically engineered mice carrying a bicistronic expression cassette containing a fluorescent reporter (such as green fluorescent protein) and a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase under the control of an epidermal stem cell pool-specific promoter—such as the Lgr-6, Lrig1, and Lgr-5 knock-in mice—enable sorting of the stem cells and lineage tracing of their progeny. Whole mounts of murine tail epidermis stained for GFP (stem cell marker), K14 (basal layer marker) and DAPI (nuclei marker) are shown. B, bulge; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HG, hair germ; IFE, interfollicular epidermis; JZ, junctional zone; K14, keratin 14; KI, knock-in; SG, sebaceous gland. Scale bars, 100 µm.

Components of the Hedgehog signaling pathway, such as Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and zinc finger protein GLI-1, are expressed in the hair bulge and germ (Levy et al. 2005; Brownell et al. 2011). Morgan and colleagues showed that SHH+ stem cells are present in the hair placode during embryogenesis and contribute to the establishment of the hair bulge stem cell compartment (Levy et al. 2005). Lineage tracing using ShhGFPCre showed that SHH+ cells in the lower HF do not give rise to IFE cells, suggesting compartmentalization of epidermal stem cells during homeostasis (Levy et al. 2005). In adult skin, SHH is highly expressed in the hair germ (HF matrix during anagen) and SHH expressing cells generate all HF layers except for the outer root sheath (Youssef et al. 2010; Lapouge et al. 2011). GLI-1+ cells are found in the lower bulge and germ, as well as in the upper bulge (Brownell et al. 2011). Interestingly, stem cells expressing Gli-1 not only gave rise to differentiated cells in all layers of the lower HF, but labeled progeny were also found in the isthmus and junctional zone adjacent to the SG (Brownell et al. 2011). Finally, robust contribution to IFE regeneration on wounding has shown that GLI-1+ stem cells are multipotent (Brownell et al. 2011).

Characterizing HF stem cell markers in human skin has been challenging because of the lack of robust tools for lineage tracing (Rochat et al. 1994). Nevertheless, Vogel and coworkers determined the distribution of LRCs in human anagen HF by grafting human skin onto immunocompromised mice and performing BrdU labeling, thereby confirming the existence of LRC in the human HF bulge (Ohyama et al. 2006). The authors subsequently isolated cells from different HF regions by microdissection and performed microarray analysis. This led to the identification of a population of bulge cells with high colony-forming efficiency expressing the marker CD200, which is enriched in stem cells (Ohyama et al. 2006). Using flow cytometry sorting for different putative bulge stem cell markers, Inoue et al. (2009) were able to show that human bulge stem cells are enriched for both CD200 and K15, but negative for CD34 and CD271. Human bulge stem cells are the main focus of studies on hair regeneration defects such as androgenetic alopecia (AGA) (Paus and Cotsarelis 1999). A study by Cotsarelis and colleagues comparing the features of HF cell subpopulations in bald and nonbald scalps from AGA patients indicates heterogeneity within the HF stem cell compartment in human skin similar to mouse skin (Garza et al. 2011). Bulge stem cells enriched for K15 were retained in balding skin, but HF progenitors in the germ expressing CD200 and CD34 were lost, contributing to the defect in hair regeneration (Garza et al. 2011).

STEM CELLS OF THE UPPER HAIR FOLLICLE AND SEBACEOUS GLANDS

Work by Ghazizadeh and Taichmann (2001) initially suggested that epidermal homeostasis in the mouse is mediated by multiple stem cells with restricted lineages. Fate mapping through transfection of murine keratinocytes with a LacZ expressing retrovirus provided in vivo evidence for the presence of long-lived progenitors in SG and IFE, as both showed β-gal labeling solely to their compartment, independent of labeling in the HF bulge.

Placenta-expressed transcript protein 1 (PLET1), the first specific marker of HF stem cells to be described outside the bulge, was identified through antibody labeling (Nijhof et al. 2006). Besides expressing α6 integrin and K14, PLET1+ keratinocytes are negative for the hair bulge markers CD34 and K15 and are infrequently BrdU label retaining (Nijhof et al. 2006). In vitro assays, such as colony-forming efficiency assays and serial passage of colonies, identified PLET1+ cells as stem cells with similar proliferative capacity to bulge stem cells (Nijhof et al. 2006).

Ghazizadeh and Taichmann (2001) initially proposed the existence of a distinct population of SG stem cells. Later, Fuchs and coworkers suggested that a reservoir of cells in the HF adjacent to the SG, marked by the transcription repressor B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (BLIMP1, expressed by the Prdm1 gene), contains sebocyte progenitors (Horsley et al. 2006). Lineage tracing using a constitutively active Cre expressed under the control of the Prdm1 promoter indicated that BLIMP1+ cells give rise to differentiated lipid-producing sebocytes. Also, mice with epidermal-specific deletion of Prdm1 displayed postnatal SG hyperplasia, suggesting a role for BLIMP1 in controlling the transition of quiescent stem cells to proliferative progenitor cells (Horsley et al. 2006). However, this study is controversial because BLIMP1 is expressed in terminally differentiated cells of all epidermal compartments, including the SG (Magnúsdóttir et al. 2007; Lo Celso et al. 2008; Cottle et al. 2013; Page et al. 2013).

Leucine-rich repeats and immunoglobulin-like domain protein 1 (LRIG1) is expressed by actively cycling stem cells in the HF junctional zone (adjacent to the SG and infundibulum) and SG (Fig. 4) (Jensen et al. 2009; Page et al. 2013). LRIG1+ stem cells are enriched for PLET1, but are negative for bulge stem cell markers such as CD34 or LGR-5 and only show low expression of α6 integrin (Jensen et al. 2009; Page et al. 2013). Stem cells enriched for LRIG1 contribute to all epidermal lineages in skin reconstitution assays and feed into the SG and infundibulum in lineage-tracing experiments (Jensen et al. 2009; Page et al. 2013). On wounding, progeny of LRIG1+ stem cells are rapidly recruited to the site of injury and contribute permanently to tissue regeneration (Page et al. 2013).

The isthmus, a region just above the HF bulge, contains another stem cell population marked by the Lgr family member LGR-6 (Fig. 4) (Snippert et al. 2010a). Lineage-tracing experiments have shown that LGR-6+ stem cells maintain adult homeostasis of the upper HF, SG, and IFE (Snippert et al. 2010a). Upon injury, LGR-6 stem cell progeny readily contribute to wound healing, as well as to hair neogenesis when grafted onto nude mice (Snippert et al. 2010a). During postnatal hair morphogenesis, epidermal Lgr-6 expression is mainly detectable in the isthmus region, but LGR-6+ cells are also found in the IFE basal layer, periphery of the SG and the lower HF (Snippert et al. 2010a). Recent work has shown (Page et al. 2013) that this expression pattern is maintained in adult life, which might explain the robust and rapid labeling of IFE and SG during tamoxifen-induced lineage-tracing experiments, as reported by Snippert et al. (2010a). In their 2010 study, Clevers and colleagues concluded that “LGR-6 marks the most primitive epidermal stem cell” (Snippert et al. 2010a). This holds true provided that the scattered LGR-6+ cells within all epidermal compartments (outside the isthmus region) are indeed stem cells. Thus, Lgr-6 expression might mark stem cells that postnatally migrate into all epidermal compartments to maintain adult homeostasis of the entire tissue.

Its remains unclear whether LGR-6+ cells in the isthmus are also enriched for GLI-1, as detection of either endogenous protein has been largely unsuccessful. Given that GLI-1+ cells give rise to progeny in the isthmus and junctional zone, but not to sebocytes, it suggests that both markers are coexpressed at least in some cells in the upper HF (Snippert et al. 2010a; Brownell et al. 2011).

In human skin, no markers of stem cells residing in either the junctional zone or SGs have been described so far. However, in agreement with some work on BLIMP1 expression in mouse SGs (Magnúsdóttir et al. 2007; Lo Celso et al. 2008; Cottle et al. 2013), Sellheyer and Krahl (2010) identified BLIMP1 as a marker of terminally differentiated sebocytes, not as a sebocyte progenitor marker.

STEM CELLS OF THE INTERFOLLICULAR EPIDERMIS

Although the evidence for stem cells in human IFE was established many years ago from clinical applications of cultured epidermis, there has been considerable debate about whether or not there are stem cells in mouse IFE (Jones et al. 2007). Lineage tracing with the AhCreERT transgenic mouse line (where CreER is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues) has been interpreted as evidence for the existence of a single pool of unipotent progenitors. In contrast, lineage analysis using CreER driven by K14 or the promoter of the differentiation marker involucrin (Ivl) argue for the existence of a slow cycling stem cell population that gives rise to a more rapidly cycling progenitor cell population (Clayton et al. 2007; Mascre et al. 2012). The observation that mouse tail IFE is characterized by two distinct differentiation programs (parakeratotic scales and orthokeratotic interscales) that are maintained by distinct populations in the IFE basal layer with different proliferation rates suggests the need to reinterpret the earlier studies (Gomez et al. 2013). One candidate for a marker of mouse IFE stem cells is LGR-6 (Fig. 4) (Snippert et al. 2010a; Sotiropoulou and Blanpain 2012; Page et al. 2013).

Basal layer keratinocytes are not the only IFE cells to express K14. The touch dome is a distinct compartment within the IFE that contains mechanosensory Merkel cells and specialized keratinocytes (touch dome keratinocytes) (Woo et al. 2010). The developmental origin of Merkel cells was long attributed to the neural crest (Szeder et al. 2003), but lineage tracing using epidermal basal layer markers such as K14 has provided evidence that they are of epidermal origin (Morrison et al. 2009; Van Keymeulen et al. 2009; Woo et al. 2010). K17+ stem cells within the touch dome maintain Merkel cell homeostasis and also contribute to the differentiated keratinocytes above the touch dome (Doucet et al. 2013). Differentiated Merkel cells express the transcription factor SOX-2, and epidermal deletion of Sox-2 results in a reduction in Merkel cell number (Lesko et al. 2013).

Because techniques for culturing human IFE stem cells in vitro are available (Rheinwald and Green 1975), flow cytometry combined with clonal analysis can be used to identify stem cell markers. IFE basal layer cells are heterogeneous and some cells differentiate within a few rounds of division, whereas others (the putative stem cells) show extensive self-renewal capacity, both in culture (Barrandon and Green 1987) and following engraftment into immune compromised mice (Barrandon et al. 1988; Jones et al. 1995).

The first in vitro–characterized marker of human IFE stem cells was high expression of β1 integrin ECM receptors (Jones and Watt 1993). These cells are located in clusters in human IFE in vivo (Jones et al. 1995). Human epidermal stem cells are also reported to express high levels of α6 integrin (Li et al. 1998) and low levels of the transferrin receptor (CD71) (Tani et al. 2000) and desmoglein-3 (DSG3) (Wan et al. 2003). Cells expressing high levels of β1 integrin are enriched for other markers, including the Notch ligand delta-like 1 (DLL1) (Lowell et al. 2000) and melanoma chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (MCSP) (Legg et al. 2003).

Single-cell gene expression profiling has been used to identify further markers of human epidermal stem cells, including LRIG1, the scaffold protein FERM domain-containing protein 4A (FRMD4A) (Jensen and Watt 2006; Goldie et al. 2012), and CD46 (Tan et al. 2013). As the sensitivity of the technique has improved, it has been possible to resolve two subpopulations of human IFE basal layer cells and to show that their gene expression profiles alter their interactions with the niche and, in addition, that the genes expressed by each population are not independently regulated (Tan et al. 2013). Cultured human keratinocytes expressing high levels of CD46 are highly adhesive and clonogenic and enriched for mRNA of ITGB1 and DLL1 (Tan et al. 2013).

STEM CELLS OF THE ECCRINE SWEAT GLANDS AND DUCTS

Eccrine sweat glands are essential for thermoregulation and are present in all skin areas of the human body. However, in murine skin, sweat glands are restricted to non-hair-bearing areas such as the footpads. Work from the 1950s suggested that human sweat gland stem cells reside within the basal layer of the sweat duct close to where it becomes contiguous with the epidermis (Lobitz et al. 1954). Later studies showed that human eccrine sweat gland stem cells are capable of reconstituting the entire epidermis on grafting (Biedermann et al. 2010). Porcine skin can also be reconstituted from sweat gland cells (Miller et al. 1998).

In contrast to studies of human skin, murine sweat gland stem cells have remained elusive until recently. Fuchs and colleagues have now provided evidence for distinct stem cell populations residing in sweat glands and ducts, which contribute to tissue homeostasis and wound repair (Lu et al. 2012). All of the epithelial structures of sweat glands and ducts are developmentally derived from K5+/K14+ multipotent progenitors. However, lineage-tracing experiments reveal that during adult homeostasis and on injury, the lineages of the sweat gland and duct are maintained by distinct myoepithelial (K5+/K14+) and luminal (K19+/K18+/K15+) progenitors behaving as unipotent stem cells (Lu et al. 2012). Interestingly, upon skin injury, only SOX-9+ ductal but not glandular progenitors are able to contribute to epidermal wound repair, suggesting a stem cell hierarchy that remains to be explored further (Lu et al. 2012).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Although epidermal stem cells reside in distinct locations and maintain homeostasis in a highly compartmentalized fashion (Watt and Jensen 2009; Greco and Guo 2010; Page et al. 2013), each stem cell population retains the capacity to differentiate into cells of all epidermal lineages, in response to wounding or genetic manipulation (Owens and Watt 2003; Blanpain and Fuchs 2009; Watt and Jensen 2009). This remarkable plasticity of adult epidermal stem cells has become apparent only recently and can be achieved by disrupting normal epidermal organization or by altering key signaling pathways such as the canonical Wnt pathway (Silva-Vargas et al. 2005). A network of intracellular signaling pathways and reciprocal signaling with other cell types, such as melanocytes and dermal fibroblasts, maintain epidermal stem cell homeostasis (Watt and Jensen 2009; Watt and Driskell 2010; Collins et al. 2011; Rabbani et al. 2011). Different epidermal cell subpopulations show differential sensitivity to activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Baker et al. 2010). Stem cell behaviour is thus regulated—in the epidermis, as in other cell types—by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms.

Identifying stem cell subpopulations and their specific markers is of great interest for epidermal stem cell biology, as the stem cell contribution to such diverse skin changes as cancer, baldness, wound repair, and skin aging is barely understood (Paus and Cotsarelis 1999; Perez-Losada and Balmain 2003; Giangreco et al. 2010; Arwert et al. 2012; Plikus et al. 2012).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

K.K. is the recipient of a Ph.D. studentship from the U.K. Medical Research Council (MRC). F.M.W. gratefully acknowledges funding from the MRC, Wellcome Trust, and the European Union Framework 7 program. We thank Denny L. Cottle, Giacomo Donati, and Ryan R. Driskell for their comments and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Alonso L, Fuchs E. 2006. The hair cycle. J Cell Sci 119: 391–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arwert EN, Hoste E, Watt FM. 2012. Epithelial stem cells, wound healing and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 12: 170–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CM, Verstuyf A, Jensen KB, Watt FM. 2010. Differential sensitivity of epidermal cell subpopulations to β-catenin-induced ectopic hair follicle formation. Dev Biol 343: 40–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, et al. 2007. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449: 1003–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, Sato T, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, et al. 2010. Lgr5+ve stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 6: 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrandon Y, Green H. 1987. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84: 2302–2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrandon Y, Li V, Green H. 1988. New techniques for the grafting of cultured human epidermal cells onto athymic animals. J Invest Dermatol 91: 315–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann T, Pontiggia L, Bottcher-Haberzeth S, Tharakan S, Braziulis E, Schiestl C, Meuli M, Reichmann E. 2010. Human eccrine sweat gland cells can reconstitute a stratified epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 130: 1996–2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Fuchs E. 2009. Epidermal homeostasis: A balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E. 2004. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell 118: 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Kishimoto J. 2003. Molecular control of epithelial–mesenchymal interactions during hair follicle cycling. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 8: 46–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun KM, Niemann C, Jensen UB, Sundberg JP, Silva-Vargas V, Watt FM. 2003. Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: Visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development 130: 5241–5255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell I, Guevara E, Bai CB, Loomis CA, Joyner AL. 2011. Nerve-derived sonic hedgehog defines a niche for hair follicle stem cells capable of becoming epidermal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 8: 552–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challen GA, Goodell MA. 2008. Promiscuous expression of H2B-GFP transgene in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS ONE 3: e2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Pasolli HA, Giannopoulou EG, Guasch G, Gronostajski RM, Elemento O, Fuchs E. 2013. NFIB is a governor of epithelial-melanocyte stem cell behaviour in a shared niche. Nature 495: 98–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Heller E, Beronja S, Oshimori N, Stokes N, Fuchs E. 2012. An RNA interference screen uncovers a new molecule in stem cell self-renewal and long-term regeneration. Nature 485: 104–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton E, Doupe DP, Klein AM, Winton DJ, Simons BD, Jones PH. 2007. A single type of progenitor cell maintains normal epidermis. Nature 446: 185–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CA, Kretzschmar K, Watt FM. 2011. Reprogramming adult dermis to a neonatal state through epidermal activation of β-catenin. Development 138: 5189–5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsarelis G. 2006. Epithelial stem cells: A folliculocentric view. J Invest Dermatol 126: 1459–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsarelis G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. 1990. Label-retaining cells reside in the bulge area of pilosebaceous unit: Implications for follicular stem cells, hair cycle, and skin carcinogenesis. Cell 61: 1329–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottle DL, Kretzschmar K, Schweiger PJ, Quist SR, Gollnick HP, Natsuga K, Aoyagi S, Watt FM. 2013. c-MYC-induced sebaceous gland differentiation is controlled by an androgen receptor/p53 axis. Cell Rep 3: 427–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet YS, Woo SH, Ruiz ME, Owens DM. 2013. The touch dome defines an epidermal niche specialized for mechanosensory signaling. Cell Rep 3: 1759–1765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driskell RR, Clavel C, Rendl M, Watt FM. 2011. Hair follicle dermal papilla cells at a glance. J Cell Sci 124: 1179–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa E, Fretz J, Berry R, Schmidt B, Rodeheffer M, Horowitz M, Horsley V. 2011. Adipocyte lineage cells contribute to the skin stem cell niche to drive hair cycling. Cell 146: 761–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. 2009. Finding one's niche in the skin. Cell Stem Cell 4: 499–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Horsley V. 2011. Ferreting out stem cells from their niches. Nat Cell Biol 13: 513–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Ferreira M, Donati G, Marciano DK, Linton JM, Sato Y, Hartner A, Sekiguchi K, Reichardt LF, Watt FM. 2011. The basement membrane of hair follicle stem cells is a muscle cell niche. Cell 144: 577–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza LA, Yang CC, Zhao T, Blatt HB, Lee M, He H, Stanton DC, Carrasco L, Spiegel JH, Tobias JW, et al. 2011. Bald scalp in men with androgenetic alopecia retains hair follicle stem cells but lacks CD200-rich and CD34-positive hair follicle progenitor cells. J Clin Invest 121: 613–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazizadeh S, Taichman LB. 2001. Multiple classes of stem cells in cutaneous epithelium: A lineage analysis of adult mouse skin. EMBO J 20: 1215–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangreco A, Goldie SJ, Failla V, Saintigny G, Watt FM. 2010. Human skin aging is associated with reduced expression of the stem cell markers β1 integrin and MCSP. J Invest Dermatol 130: 604–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldie SJ, Mulder KW, Tan DW, Lyons SK, Sims AH, Watt FM. 2012. FRMD4A upregulation in human squamous cell carcinoma promotes tumor growth and metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis. Cancer Res 72: 3424–3436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez CE, Chua W, Miremadi A, Quist SR, Headon DJ, Watt FM. 2013. The interfollicular epidermis of adult mouse tail comprises two distinct cell lineages that are differentially regulated by Wnt, Edaradd, and Lrig1. Stem Cell Reports 1: 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco V, Guo S. 2010. Compartmentalized organization: A common and required feature of stem cell niches? Development 137: 1586–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco V, Chen T, Rendl M, Schober M, Pasolli HA, Stokes N, Dela Cruz-Racelis J, Fuchs E. 2009. A two-step mechanism for stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 4: 155–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H. 2008. The birth of therapy with cultured cells. Bioessays 30: 897–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoess RH, Abremski K. 1984. Interaction of the bacteriophage P1 recombinase Cre with the recombining site loxP. Proc Natl Acad Sci 81: 1026–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley V, O'Carroll D, Tooze R, Ohinata Y, Saitou M, Obukhanych T, Nussenzweig M, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. 2006. Blimp1 defines a progenitor population that governs cellular input to the sebaceous gland. Cell 126: 597–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley V, Aliprantis AO, Polak L, Glimcher LH, Fuchs E. 2008. NFATc1 balances quiescence and proliferation of skin stem cells. Cell 132: 299–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YC, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. 2011. Dynamics between stem cells, niche, and progeny in the hair follicle. Cell 144: 92–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huch M, Dorrell C, Boj SF, van Es JH, Li VS, van de Wetering M, Sato T, Hamer K, Sasaki N, Finegold MJ, et al. 2013. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature 494: 247–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Aoi N, Sato T, Yamauchi Y, Suga H, Eto H, Kato H, Araki J, Yoshimura K. 2009. Differential expression of stem-cell-associated markers in human hair follicle epithelial cells. Lab Invest 89: 844–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch R, Mintz B. 1974. Simian virus 40 DNA sequences in DNA of healthy adult mice derived from preimplantation blastocysts injected with viral DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 71: 1250–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaks V, Barker N, Kasper M, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Clevers H, Toftgard R. 2008. Lgr5 marks cycling, yet long-lived, hair follicle stem cells. Nat Genet 40: 1291–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Watt FM. 2006. Single-cell expression profiling of human epidermal stem and transit-amplifying cells: Lrig1 is a regulator of stem cell quiescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 11958–11963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Collins CA, Nascimento E, Tan DW, Frye M, Itami S, Watt FM. 2009. Lrig1 expression defines a distinct multipotent stem cell population in mammalian epidermis. Cell Stem Cell 4: 427–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Driskell RR, Watt FM. 2010. Assaying proliferation and differentiation capacity of stem cells using disaggregated adult mouse epidermis. Nat Protoc 5: 898–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Watt FM. 1993. Separation of human epidermal stem cells from transit amplifying cells on the basis of differences in integrin function and expression. Cell 73: 713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Harper S, Watt FM. 1995. Stem cell patterning and fate in human epidermis. Cell 80: 83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Simons BD, Watt FM. 2007. Sic transit gloria: Farewell to the epidermal transit amplifying cell? Cell Stem Cell 1: 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. 2006. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6: 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar K, Watt FM. 2012. Lineage tracing. Cell 148: 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapouge G, Youssef KK, Vokaer B, Achouri Y, Michaux C, Sotiropoulou PA, Blanpain C. 2011. Identifying the cellular origin of squamous skin tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 7431–7436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg J, Jensen UB, Broad S, Leigh I, Watt FM. 2003. Role of melanoma chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan in patterning stem cells in human interfollicular epidermis. Development 130: 6049–6063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesko MH, Driskell RR, Kretzschmar K, Goldie SJ, Watt FM. 2013. Sox2 modulates the function of two distinct cell lineages in mouse skin. Dev Biol. 382: 15–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy V, Lindon C, Harfe BD, Morgan BA. 2005. Distinct stem cell populations regenerate the follicle and interfollicular epidermis. Dev Cell 9: 855–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Simmons PJ, Kaur P. 1998. Identification and isolation of candidate human keratinocyte stem cells based on cell surface phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 3902–3907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobitz WC Jr, Holyoke JB, Montagna W. 1954. Responses of the human eccrine sweat duct to controlled injury: Growth center of the epidermal sweat duct unit. J Invest Dermatol 23: 329–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Celso C, Berta MA, Braun KM, Frye M, Lyle S, Zouboulis CC, Watt FM. 2008. Characterization of bipotential epidermal progenitors derived from human sebaceous gland: Contrasting roles of c-Myc and β-catenin. Stem Cells 26: 1241–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell S, Jones P, Le Roux I, Dunne J, Watt FM. 2000. Stimulation of human epidermal differentiation by delta-notch signalling at the boundaries of stem-cell clusters. Curr Biol 10: 491–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CP, Polak L, Rocha AS, Pasolli HA, Chen SC, Sharma N, Blanpain C, Fuchs E. 2012. Identification of stem cell populations in sweat glands and ducts reveals roles in homeostasis and wound repair. Cell 150: 136–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyle S, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Liu Y, Elder DE, Albelda S, Cotsarelis G. 1998. The C8/144B monoclonal antibody recognizes cytokeratin 15 and defines the location of human hair follicle stem cells. J Cell Sci 111: 3179–3188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. 2010. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 13: 133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnúsdóttir E, Kalachikov S, Mizukoshi K, Savitsky D, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Panteleyev AA, Calame K. 2007. Epidermal terminal differentiation depends on B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 14988–14993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Fujiwara Y, Chapdelaine A, Yang H, Orkin SH. 2001. Activation of EGFP expression by Cre-mediated excision in a new ROSA26 reporter mouse strain. Blood 97: 324–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascre G, Dekoninck S, Drogat B, Youssef KK, Brohee S, Sotiropoulou PA, Simons BD, Blanpain C. 2012. Distinct contribution of stem and progenitor cells to epidermal maintenance. Nature 489: 257–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messenger AG. 1993. The control of hair growth: An overview. J Invest Dermatol 101: 4S–9S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SJ, Burke EM, Rader MD, Coulombe PA, Lavker RM. 1998. Re-epithelialization of porcine skin by the sweat apparatus. J Invest Dermatol 110: 13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RJ, Potten CS. 1994. Slowly cycling (label-retaining) epidermal cells behave like clonogenic stem cells in vitro. Cell Prolif 27: 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RJ, Liu Y, Marles L, Yang Z, Trempus C, Li S, Lin JS, Sawicki JA, Cotsarelis G. 2004. Capturing and profiling adult hair follicle stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 22: 411–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison KM, Miesegaes GR, Lumpkin EA, Maricich SM. 2009. Mammalian Merkel cells are descended from the epidermal lineage. Dev Biol 336: 76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Rendl M, Fuchs E. 2006. Tcf3 governs stem cell features and represses cell fate determination in skin. Cell 127: 171–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhof JG, Braun KM, Giangreco A, van Pelt C, Kawamoto H, Boyd RL, Willemze R, Mullenders LH, Watt FM, de Gruijl FR, et al. 2006. The cell-surface marker MTS24 identifies a novel population of follicular keratinocytes with characteristics of progenitor cells. Development 133: 3027–3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak JA, Polak L, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. 2008. Hair follicle stem cells are specified and function in early skin morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 3: 33–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama M, Terunuma A, Tock CL, Radonovich MF, Pise-Masison CA, Hopping SB, Brady JN, Udey MC, Vogel JC. 2006. Characterization and isolation of stem cell-enriched human hair follicle bulge cells. J Clin Invest 116: 249–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DM, Watt FM. 2003. Contribution of stem cells and differentiated cells to epidermal tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 444–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Lombard P, Ng F, Göttgens B, Jensen KB. 2013. Distinct populations of stem cells maintain the epidermis as a series of autonomous compartments. Cell Stem Cell 13: 471–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus R, Cotsarelis G. 1999. The biology of hair follicles. N Engl J Med 341: 491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Losada J, Balmain A. 2003. Stem-cell hierarchy in skin cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 434–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson M, Brylka H, Kraus A, John S, Rappl G, Schettina P, Niemann C. 2011. TCF/Lef1 activity controls establishment of diverse stem and progenitor cell compartments in mouse epidermis. EMBO J 30: 3004–3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plikus MV, Gay DL, Treffeisen E, Wang A, Supapannachart RJ, Cotsarelis G. 2012. Epithelial stem cells and implications for wound repair. Semin Cell Dev Biol 23: 946–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proksch E, Brandner JM, Jensen JM. 2008. The skin: An indispensable barrier. Exp Dermatol 17: 1063–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani P, Takeo M, Chou W, Myung P, Bosenberg M, Chin L, Taketo MM, Ito M. 2011. Coordinated activation of Wnt in epithelial and melanocyte stem cells initiates pigmented hair regeneration. Cell 145: 941–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee H, Polak L, Fuchs E. 2006. Lhx2 maintains stem cell character in hair follicles. Science 312: 1946–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheinwald JG, Green H. 1975. Serial cultivation of strains of human epidermal keratinocytes: The formation of keratinizing colonies from single cells. Cell 6: 331–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat A, Kobayashi K, Barrandon Y. 1994. Location of stem cells of human hair follicles by clonal analysis. Cell 76: 1063–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani N, Clausen BE, Stoitzner P. 2010. Langerhans cells and more: Langerin-expressing dendritic cell subsets in the skin. Immunol Rev 234: 120–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompolas P, Deschene ER, Zito G, Gonzalez DG, Saotome I, Haberman AM, Greco V. 2012. Live imaging of stem cell and progeny behaviour in physiological hair-follicle regeneration. Nature 487: 496–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B, Horsley V. 2012. Unravelling hair follicle-adipocyte communication. Exp Dermatol 21: 827–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellheyer K, Krahl D. 2010. Blimp-1: A marker of terminal differentiation but not of sebocytic progenitor cells. J Cutan Pathol 37: 362–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Vargas V, Lo Celso C, Giangreco A, Ofstad T, Prowse DM, Braun KM, Watt FM. 2005. β-catenin and Hedgehog signal strength can specify number and location of hair follicles in adult epidermis without recruitment of bulge stem cells. Dev Cell 9: 121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, Clevers H. 2011. Tracking adult stem cells. EMBO Rep 12: 113–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, Haegebarth A, Kasper M, Jaks V, van Es JH, Barker N, van de Wetering M, van den Born M, Begthel H, Vries RG, et al. 2010a. Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science 327: 1385–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, van Es JH, van den Born M, Kroon-Veenboer C, Barker N, Klein AM, van Rheenen J, Simons BD, et al. 2010b. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143: 134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. 1999. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 21: 70–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulou PA, Blanpain C. 2012. Development and homeostasis of the skin epidermis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a008383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. 2001. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol 1: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser ML, Bailey AP, Senyo SE, Guillermier C, Perlstein TS, Gould AP, Lee RT, Lechene CP. 2012. Multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry quantifies stem cell division and metabolism. Nature 481: 516–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeder V, Grim M, Halata Z, Sieber-Blum M. 2003. Neural crest origin of mammalian Merkel cells. Dev Biol 253: 258–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan DW, Jensen KB, Trotter MW, Connelly JT, Broad S, Watt FM. 2013. Single-cell gene expression profiling reveals functional heterogeneity of undifferentiated human epidermal cells. Development 140: 1433–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani H, Morris RJ, Kaur P. 2000. Enrichment for murine keratinocyte stem cells based on cell surface phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97: 10960–10965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till JE, McCulloch EA. 1961. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res 14: 213–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trempus CS, Morris RJ, Bortner CD, Cotsarelis G, Faircloth RS, Reece JM, Tennant RW. 2003. Enrichment for living murine keratinocytes from the hair follicle bulge with the cell surface marker CD34. J Invest Dermatol 120: 501–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy TC, Arabzadeh A, Turksen K. 2011. Re-assessing K15 as an epidermal stem cell marker. Stem Cell Rev 7: 927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbar T, Guasch G, Greco V, Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Rendl M, Fuchs E. 2004. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science 303: 359–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Keymeulen A, Mascre G, Youseff KK, Harel I, Michaux C, De Geest N, Szpalski C, Achouri Y, Bloch W, Hassan BA, et al. 2009. Epidermal progenitors give rise to Merkel cells during embryonic development and adult homeostasis. J Cell Biol 187: 91–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin V, Degenstein L, Wise B, Fuchs E. 1999. The magical touch: Genome targeting in epidermal stem cells induced by tamoxifen application to mouse skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 8551–8556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal VP, Chaboissier MC, Lutzkendorf S, Cotsarelis G, Mill P, Hui CC, Ortonne N, Ortonne JP, Schedl A. 2005. Sox9 is essential for outer root sheath differentiation and the formation of the hair stem cell compartment. Curr Biol 15: 1340–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H, Stone MG, Simpson C, Reynolds LE, Marshall JF, Hart IR, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Eady RA. 2003. Desmosomal proteins, including desmoglein 3, serve as novel negative markers for epidermal stem cell-containing population of keratinocytes. J Cell Sci 16: 4239–4248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt FM, Driskell RR. 2010. The therapeutic potential of stem cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365: 155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt FM, Fujiwara H. 2011. Cell-extracellular matrix interactions in normal and diseased skin. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a005124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt FM, Jensen KB. 2009. Epidermal stem cell diversity and quiescence. EMBO Mol Med 1: 260–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SH, Stumpfova M, Jensen UB, Lumpkin EA, Owens DM. 2010. Identification of epidermal progenitors for the Merkel cell lineage. Development 137: 3965–3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Woo WM, Nagao K, Li W, Terunuma A, Mukouyama YS, Oro AE, Vogel JC, Brownell I. 2013. Perivascular hair follicle stem cells associate with a venule annulus. J Invest Dermatol. 133: 2324–2331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef KK, Van Keymeulen A, Lapouge G, Beck B, Michaux C, Achouri Y, Sotiropoulou PA, Blanpain C. 2010. Identification of the cell lineage at the origin of basal cell carcinoma. Nat Cell Biol 12: 299–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YV, White BS, Shalloway DI, Tumbar T. 2010. Stem cell dynamics in mouse hair follicles: A story from cell division counting and single cell lineage tracing. Cell Cycle 9: 1504–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinyk DL, Mercer EH, Harris E, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL. 1998. Fate mapping of the mouse midbrain-hindbrain constriction using a site-specific recombination system. Curr Biol 8: 665–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]