Background: Characterization of amyloid precursor protein and the mechanism of amyloidogenesis in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis have not been elucidated previously.

Results: Galectin-7 fragments containing β-strand peptides are highly amyloidogenic in vitro.

Conclusion: Galectin-7 is an amyloid precursor protein in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.

Significance: We have proposed the possible mechanism of amyloid deposition in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis.

Keywords: Actin, Amyloid, Apoptosis, Galectin, Keratin, Keratinocyte, β-strand

Abstract

Pathogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA) is unclear, but pathogenic relationship to keratinocyte apoptosis has been implicated. We have previously identified galectin-7, actin, and cytokeratins as the major constituents of PLCA. Determination of the amyloidogenetic potential of these proteins by thioflavin T (ThT) method demonstrated that galectin-7 molecule incubated at pH 2.0 was capable of binding to the dye, but failed to form amyloid fibrils. When a series of galectin-7 fragments containing β-strand peptides were prepared to compare their amyloidogenesis, Ser31-Gln67 and Arg120-Phe136 were aggregated to form amyloid fibrils at pH 2.0. The rates of aggregation of Ser31-Gln67 and Arg120-Phe136 were dose-dependent with maximal ThT levels after 3 and 48 h, respectively. Their synthetic analogs, Phe33-Lys65 and Leu121-Arg134, which are both putative tryptic peptides, showed comparable amyloidogenesis. The addition of sonicated fibrous form of Ser31-Gln67 or Phe33-Lys65 to monomeric Ser31-Gln67 or Phe33-Lys65 solution, respectively, resulted in an increased rate of aggregation and extension of amyloid fibrils. Amyloidogenic potentials of Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 were inhibited by actin and cytokeratin fragments, whereas those of Arg120-Phe136 and Leu121-Arg134 were enhanced in the presence of Gly84-Arg113, a putative tryptic peptide of galectin-7. Degraded fragments of the galectin-7 molecule produced by limited trypsin digestion, formed amyloid fibrils after incubation at pH 2.0. These results suggest that the tryptic peptides of galectin-7 released at neutral pH, may lead to amyloid fibril formation of PLCA in the intracellular acidified conditions during keratinocyte apoptosis via regulation by the galectin-7 peptide as well as actin and cytokeratins.

Introduction

Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA)2 is a skin-limited amyloidosis that is clinically characterized by chronic pruritic papules (lichen amyloidosus) or macules (macular amyloidosis) and histologically characterized by the deposition of amyloid in the superficial dermis (1). PLCA is relatively common in South America and Southeast Asia, and most cases are the acquired type with unknown pathogenesis. The amyloid precursor protein of PLCA has been hypothesized to be cytokeratins based on the immunohistochemical reactivity of amyloid deposit with cytokeratin antibodies (2, 3). The immunohistochemical positivity with cytokeratins in the lesional skin, however, does not always indicate that cytokeratins are amyloidogenic precursor proteins. Because cytokeratins are major intracellular proteins of keratinocytes that are present as a stable form of keratin intermediate filaments (KIF), immunoreactive epitopes of cytokeratins may remain intact even after completion of apoptotic degradation and amyloid accumulation. In addition, it has been demonstrated that KIF and its proteolytic fragments do not react with thioflavin T (ThT) (4). Furthermore, the secondary structure of cytokeratin consisits of α-helical, coiled-coil rod domains (5), whereas more than 20 amyloidogenic proteins that can bind Congo red or ThT share common cross-β sheet structures, which is defined as β-fibrillosis (6). Recently, we identified galectin-7 (Gal-7), actin, and cytokeratins as well as serum amyloid P component (SAP) and apolipoprotein E (Apo E) as the major components of amyloid deposits of PLCA in the water soluble fraction recovered from lesional skin, and we found that all of these proteins were present in the amyloid deposits of PLCA according to immunohistochemical studies (2, 7–9). SAP and Apo E are universal non-fibrillar constituents of amyloid deposits and will therefore be excluded from the candidates for amyloid precursor protein. The next questions are which protein (Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins) is directly related to amyloidogenesis and how the protein aggregates to form amyloid fibrils.

The initial event of amyloid formation in PLCA is thought to be related to keratinocyte apoptosis because 1) TUNEL-positive keratinocytes are commonly detected in the epidermis overlying the amyloid-laden dermis (10), and 2) amyloid deposits are restricted to the papillary dermis just beneath the thinned epidermis, suggesting that a hyperproliferative thickened epidermis undergoes extensive apoptotic cell death (filamentous degeneration) (11) and is then substituted by amyloid materials via an unknown mechanism. Apoptosis of keratinocytes, which is induced by UVB irradiation, reactive oxygen species (ROS), drugs or chemical reagents accompanies the activation of certain proteolytic machinery (12). Three major apoptosis-related enzymes of keratinocytes have been reported, including caspases, cathepsin D (cath D), and trypsin-like enzymes, although their final target molecules and their exact roles in apoptosis are not fully known. Nine caspases are expressed in normal human keratinocytes; of these, caspases 3, 8, and 9 are activated in UVB-induced apoptosis (13); in particular, caspase 3 appears to be important because its activity is enhanced by apoptosis-induced Gal-7 (14). Cath D, a major lysosomal, acidic protease of the epidermis, induces apoptosis via directly priming caspase-8 activation (15, 16). Keratinocytes potentially synthesize multiple forms of trypsin-like serine proteases including trypsinogen 4, 5, and kallikrein-related peptidases (KLKs) (17, 18). A tryptic serine protease secreted by cultured keratinocytes potentially induces keratinocyte apoptosis, which is blocked by soybean trypsin inhibitor, but the precise mechanism is currently unknown (19).

The general mechanism of amyloid fibril formation is not fully understood. A nucleation- dependent polymerization model is proposed for the general mechanism of amyloid fibril formation in several types of amyloidosis, such as β2-microglobulin in dialysis amyloidosis and amyloid-β (Aβ) in Alzheimer disease. Their amyloidogenic models consist of two fundamental phases, nucleation (seed formation), and extension (deposition). Seed formation requires the assembly of monomeric protein into a template, representing the rate-limiting step in amyloid fibril formation. Once the seed has been formed, growth of the template by the deposition of additional monomeric protein becomes thermodynamically favorable, resulting in rapid extension of amyloid fibrils (20, 21).

Galectins constitute a large family of β-galactoside-binding lectins. At least 14 mammalian galectins that share structural similarities in their carbohydrate recognition domains have been reported. Despite the lack of signal peptide, galectins can be secreted by an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi-independent pathway. They can be found both intracellularly (cytoplasmic and/or nuclear) and extracellularly as well as, sometimes, in association with the plasma membrane, although they do not contain a transmembrane domain. From these variable subcellular locations, galectins have been implicated in a wide range of cellular processes, including cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, extracellular matrix remodelling, cell cycle, cancer biology, intracellular trafficking, and apoptosis. Some galectins are pro-apoptotic, whereas others are anti-apoptotic; some galectins induce apoptosis by binding to cell surface glycoproteins, whereas others regulate apoptosis through interacting with intracellular proteins (22, 23). Gal-7 is a prototype galectin, with a molecular weight of 14 kDa (136 amino acid residues), that is expressed only in stratified epithelia (24). Its structure consists of β-sandwich with the packing of two β-sheets (25). Gal-7 is associated with multiple keratinocyte functions including cell migration and apoptosis. Gal-7-deficient mice display reduced reepithelialization potential compared with wild-type littermates (26). Gal-7 expression is markedly induced during UVB-induced apoptotic processes of epidermal keratinocytes, paralleling p53 stabilization (27); the keratinocytes overexpressing Gal-7 undergo apoptosis, indicating that Gal-7 is a pro-apoptotic protein (14, 28).

In the present study, we 1) determine the amyloidogenic potentials of the candidate proteins, Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins; 2) determine which part of Gal-7 is involved in amyloidogenesis; and 3) show whether degraded fragments of Gal-7 produced by keratinocyte apoptosis-related proteases can form amyloid fibrils.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Proteins and Synthetic Peptides

Recombinant human Gal-7 expressed from cDNA clone (29) was purchased from R&D systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). The purity of the sample was more than 97% as determined by SDS-PAGE. The structure of human galectin-7 consists of paired β-sheets, F1-F5 and S1-S6a fragments (see Fig. 2, A and B) (25). The β-strand-containing fragments of Gal-7, Gal S1-F2 (NH2-PHKSSLPEGIRPGTVLRIRGLVPP-COOH), Gal S3-S5 (NH2-SRFHVNLLCGEEQGSDAALHFNPRLDTSEVVFNSKEQ-COOH), Gal S3-S4 (NH2-SRFHVNLLCGEEQGSDAALHFNPRLD-COOH), Gal S4-S5 (NH2-DAALHFNPRLDTSEVVFNSKEQ-COOH), Gal S5-S6a (NH2-SEVVFNSKEQGSWGREERGP-COOH), Gal S6b-S6a (NH2-GSWGREERGP-COOH), Gal F3-F5 (NH2-GQPFEVLIIASDDGFKAVVGDAQYHHFRHR-COOH), and Gal S2-F1 (NH2-RLVEVGGDVQLDSVRIF-COOH) were synthesized with the solid phase method (Filgen, Inc., Bioscience Department, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan). These peptides were designed to contain one extra amino acid residue at both the amino and C-terminal ends of the β-strand domains (see Fig. 2B). Analogs of the Gal S3-S5 (amino acid number Ser31-Gln67) fragment lacking 1–4 residues at the N- or C-terminal end, including Phe33-Lys65, Ser31-Lys65, Arg32-Glu66, Phe33-Ser64, Val35-Lys65, His34-Lys65, Phe33-Asn63, and Phe33-Gln67, and those of Gal S2-F1 (amino acid number Arg120-Phe136) lacking 1–2 residues at the N or C end, including Leu121-Arg134, Leu121-Ile135, Arg120-Ile135, Leu121-Phe136, were also synthesized (See Fig. 2B). The purities of the fragments were more than 85% based on the supplier's HPLC data.

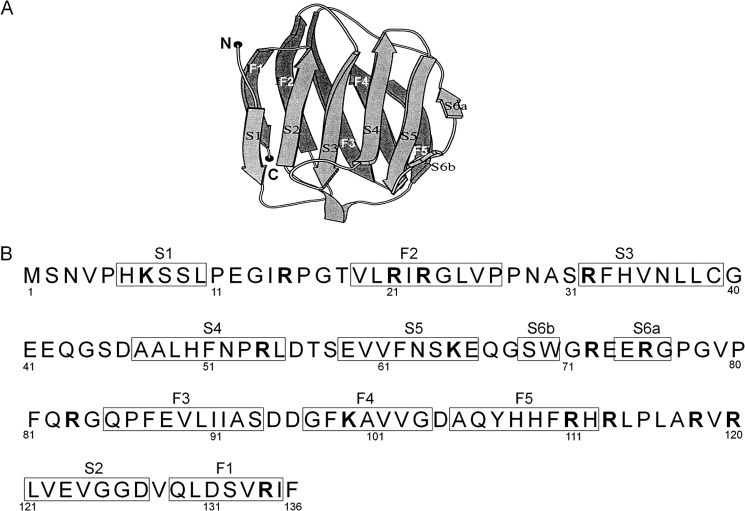

FIGURE 2.

Structure and amino acid sequence of galectin-7. A, tertiary structure of human galectin-7. Pairs of β-strand segments (S1-S5 and F1-F5) are arranged in parallel (cited from Leonidas et al. (Ref. 25) with some modifications). B, primary structure of the galectin-7 molecule. Twelve β-strand segments (S1, F2, S3, S4, S5, S6b, S6a, F3, F4, F5, S2, and F1) are boxed. Putative tryptic sites are indicated in boldface.

Human non-muscle actin (β and γ) purified from platelet was purchased from Cytoskelton, Inc. (Denver, CO), and the purity was >99%. Four species of synthetic peptides of β-actin, which contain an extra amino acid residue at both the N- and C-terminal ends of β-strand domains (30), Leu8-Pro38 (NH2-LVVDNGSGMCKAGFAGDDAPRAVFPSIVGRP-COOH), Val35-Lys68 (NH2-IVGRPRHQGVMVGMGQKDSYVGDEAQSKRGILTLKY-COOH), Gly150-Leu178 (NH2-TGIVMDSGDGVTHTVPIYEGYALPHAILRLD-COOH), and Lys238-Ile250 (NH2-EKSYELPDGQVITIG-COOH) were prepared as described above, and the purities were more than 90%.

Insoluble cytokeratins were extracted from cultured human keratinocytes (HaCaT cells) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.6 m KCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.2 mg/ml DNase I (31). The precipitate was dissolved in an 8 m urea/0.1 m β-ME at room temperature for 4 h and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was dialyzed four times against PBS; then, the resulting aggregates, which largely comprise cytokeratins (referred as insoluble cytokeratins), were redissolved in 8 m urea/0.1 m β-ME solution and reaggregated by dialysis against PBS. The procedure was repeated four times (4). Salt soluble cytokeratins were extracted from the insoluble cytokeratin aggregates using the buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 containing protease inhibitors; 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm NEM, and 1 mm PMSF) (32), which was followed by purification with molecular sieve chromatography. The fractionated proteins with molecular weights of 45–70 kDa were subjected to SDS-PAGE and then confirmed as cytokeratins by immunoblot analysis using anti-pankeratin (polyclonal, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) or cytokeratin-5 antibody (monoclonal, Novus Biologicals Inc., Littleton, CO) (not shown). The average molecular weights of cytokeratin monomers were estimated as 65 kDa.

Amyloid fibrils were sequentially extracted from the lesional skin of localized cutaneous amyloidosis with distilled water as described previously (7). The yield of the protein in the water-soluble fraction was ∼90 μg.

In Vitro Formation of Amyloid Fibril Aggregates

Prior to starting the thioflavin T (ThT) assay, we found that some peptides were easily dissolved in water, but some were difficult. In some experiments, we prepared a stock solution of the peptides with 100% Me2SO (33), and we adjusted the reaction mixtures to give the same final concentration of Me2SO. Proteins or peptides were placed into oil-free PCR tubes and, then transferred into a DNA thermal cycler (TP600, Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). The plate temperature was elevated from 4 °C to 37 °C at a maximal speed. The reaction was stopped by placing the tubes on ice. The buffers we used were 50 mm citrate-HCl buffer (pH 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0), 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), and 50 mm glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 10.0). All buffers contained 100 mm NaCl because well-organized, mature amyloid fibrils were readily formed in the presence of a high dose of NaCl (34). Amyloid fibril formation was measured with the ThT method (35, 36). Proteins or peptides were dissolved in each buffer at various doses and were then incubated at various pH ranges at 37 °C for 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, or 2–7 days. An aliquot (10 μl) was mixed with 1 ml of 5 μm ThT (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) solution in 50 mm glycine-NaOH buffer, pH 8.5. After 1 min, the fluorescence of thioflavin T was determined on a Hitachi F-2000 fluorescence spectrophotometer at an excitation wavelength of 435 nm and emission wavelength at 485 nm. Assays were performed in triplicate, and the values were averaged to provide final data. The error in each data set was below 18%.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

An aliquot was taken from the reaction mixtures, which had been prepared to determine the ThT fluorescence, applied to carbon-coated copper grids, and then subjected to electron microscopic observation by negative staining with 2% phosphotungstic acid, pH 7.0 (37) using a JEM-1010 electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Deposition of Gal-7 Peptides onto Preformed Fibrils

To determine the deposition ability of the Gal-7 peptides, we prepared seeds composed of Ser31-Gln67 or Phe33-Lys65 monomers as previously described (38). Briefly, the solutions of Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 (500 μm each) were centrifuged at 4 °C for 1 h at 15,000 × g to remove preformed aggregates. Both peptides were incubated at 37 °C in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0, containing 100 mm NaCl for 3 h, which was the time required to reach the maximal ThT level. The fibrils formed, designated as f(Ser31-Gln67) or f(Phe33-Lys65) were pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 1 h and suspended in distilled water at the concentration of 25 nmol/100 μl. The recovery of the aggregates was more than 86%, as judged by measurement of the ThT fluorescence before and after centrifugation. The aggregates were sonicated twice (pulse: 1.2 s, output level: 2) for 5 min with an ultrasonic disruptor (UC100-D, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 4 °C. An aliquot of this fibril suspension was added to Ser31-Gln67, Phe33-Lys65, or Gal-7 (50 or 10 μm) in the following buffers containing 100 mm NaCl; 50 mm citrate buffer (pH 2.0 or 4.0), 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) or 50 mm glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 10.0), yielding a final concentration of 2.5 or 5 nmol/100 μl. Low concentrations of monomers (10 and 50 μm) were used in the extension assays to avoid amyloid fibril formation from a monomer alone. The fluorescence was monitored at 37 °C for 0, 3, 6, 12, and 18 h or sometimes 30 and 48 h. Various combinations of seeds and soluble peptides were examined, including the homogeneous combination of f(Ser31-Gln67)/Ser31-Gln67 monomer, f(Phe33-Lys65)/Phe33-Lys65 monomer, or heterogeneous combination of f(Ser31-Gln67)/Gal-7 (Met1-Phe136) monomer.

Modulation of Amyloidogenesis of Gal-7 Fragments

Amyloidogenic Gal-7 peptides, Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65, were incubated at their amyloidogenic dose (200 μm) in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0, containing 100 mm NaCl in the presence of Gal-7 fragments (Gal S1-F2, Gal S5-S6a, and Gal F3-F5) (200 μm each), actin and its β-strand domains (Leu8-Pro32, Val35-Lys68, Gly150-Leu178, and Lys238-Ile250) (200 μm each), and cytokeratin digests (20–200 μm) prepared by 3-h trypsin treatment (see below) for 0, 3, 6, 10, and 18 h.

Amyloidogenic Gal-7 peptides, Arg120-Phe136, Leu121-Arg134, and Leu121-Phe136, were incubated at their poorly amyloidogenic dose (100 μm) in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0 containing 100 mm NaCl in the presence of Gal-7 fragments (Gal S1-F2, Gal F3-F5, and Gal S5-S6a) (100 μm each), actin molecule (100 μm), or cytokeratin digests (100 μm) for 10, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h.

Proteolytic Digestion of Gal-7, Actin, and Cytokeratins

Recombinant Gal-7 (200 μg), non-muscle actin (200 μg) and insoluble cytokeratin aggregates isolated from cultured keratinocytes (300 μg) were digested for 1, 3, and 8 h with trypsin (sequence grade, Promega, WI) (10 μg/ml) in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, at room temperature; cathepsin D (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., MO) (3 μg/ml) in 50 mm acetate buffer pH 4.0 at 37 °C; or caspase 3 (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) (5 μg/ml) in 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1% CHAPS at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of pepstatin A (1 μg) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) in the case of cathepsin D digestion or by the addition of acidic buffer (1 m citrate buffer, pH 2.0) in the trypsin and caspase 3 digestions. An aliquot was dissolved in SDS sample buffer (0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.0 containing 10% SDS) and then subjected to SDS-PAGE to determine the degree of the degradation of the substrates. The reaction mixtures in 100 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0, containing 100 mm NaCl were further incubated at 37 °C for 6, 24, 48, and 72 h to determine the amyloidogenic potentials of the degradation products with the ThT method and electron microscopy.

RESULTS

Fluorescence Spectra of ThT in the Presence of Amyloid Fibrils Extracted from PLCA

Water-soluble amyloid fibrils (fPLCA) (30 μg/ml) were extracted from lesional skin of PLCA as previously described (7) and showed a novel fluorescence at 485 nm with an excitation maximum at 435 nm in the presence of 5 μm of ThT in 50 mm glycine-NaOH buffer, pH 8.5 (Fig. 1A). The excitation and emission wavelengths in the following ThT assays were fixed at 435 and 485 nm, respectively.

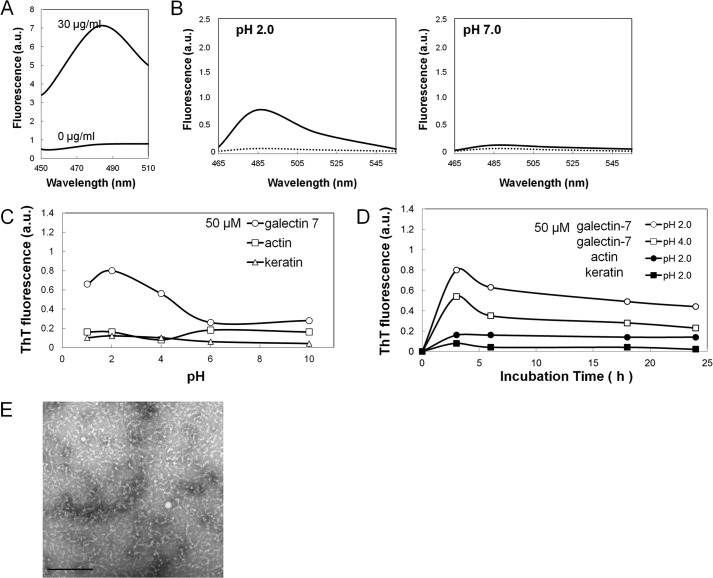

FIGURE 1.

Detection of amyloidogenic potentials of galectin-7, actin, and cytokeratins by ThT method and electron microscopic observation. A, fluorescence spectra of amyloid fibrils (fPLCA) that were isolated from the lesional skin of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA). Amyloid fibrils (30 μg/ml) produced a novel fluorescence at 485 nm with an excitation maximum at 435 nm. B, fluorescence spectra of galectin-7 (50 μm) was monitored before (dotted line) and after 3 h of incubation (solid line) at pH 2.0 (left panel) and pH 7.0 (right panel). C and D, effect of pH or the incubation time on the ThT fluorescence. Galectin-7, actin, or soluble keratin at 50 μm was incubated for 3 h at various pH ranges or for 3, 6, 18, and 24 h at pH 2.0 or 4.0. Values are normalized to those of 500 μm Gal-7 at pH 2.0 after 3 h incubation (see Fig. 3, A and B). E, electron micrographs of the structures appeared after the incubation of galectin-7 at pH 2.0 for 3 h. The bar indicates 200 nm.

Fluorescence of ThT in the Presence of Galectin-7 (Gal-7), Actin, and Cytokeratin Molecules

The emission spectra of the Gal-7, actin and cytokeratin molecules at the dose of 50 μm each were determined with an excitation spectrum at 435 nm. Gal-7 showed a novel peak at 485 nm at pH 2.0 after 3 h, but there was no fluorescence peak at pH 7.0 (Fig. 1B). Actin and cytokeratins showed no fluorescence at both pH 2.0 and 7.0 (not shown).

The effects of pH on ThT fluorescence in the presence of Gal-7, actin and soluble cytokeratins (50 μm each) were examined. ThT fluorescence of Gal-7 was pH-dependent with a maximal fluorescence after 3 h at pH 2.0, while actin and soluble cytokeratins showed no increase in ThT fluorescence in any pH ranges (Fig. 1C).

The effects of the incubation time on the ThT fluorescence in the presence of Gal-7 (50 μm) at pH 2.0 and 4.0, as well as actin and cytokeratins at pH 2.0, were examined. Gal-7 (50 μm) gave a maximal fluorescence after 3 h at both pH 2.0 and 4.0 with a gradual decrease of fluorescence for 24 h, but actin and soluble cytokeratins showed no significant change for 24 h (Fig. 1D).

Electron microscopic observation of Gal-7 after 3 h of incubation at pH 2.0 showed short, curled fibrillar structures that were not consistent with the morphology of amyloid fibrils (Fig. 1E).

In Vitro Amyloidogenesis of Synthetic Peptides for Gal-7 and Actin

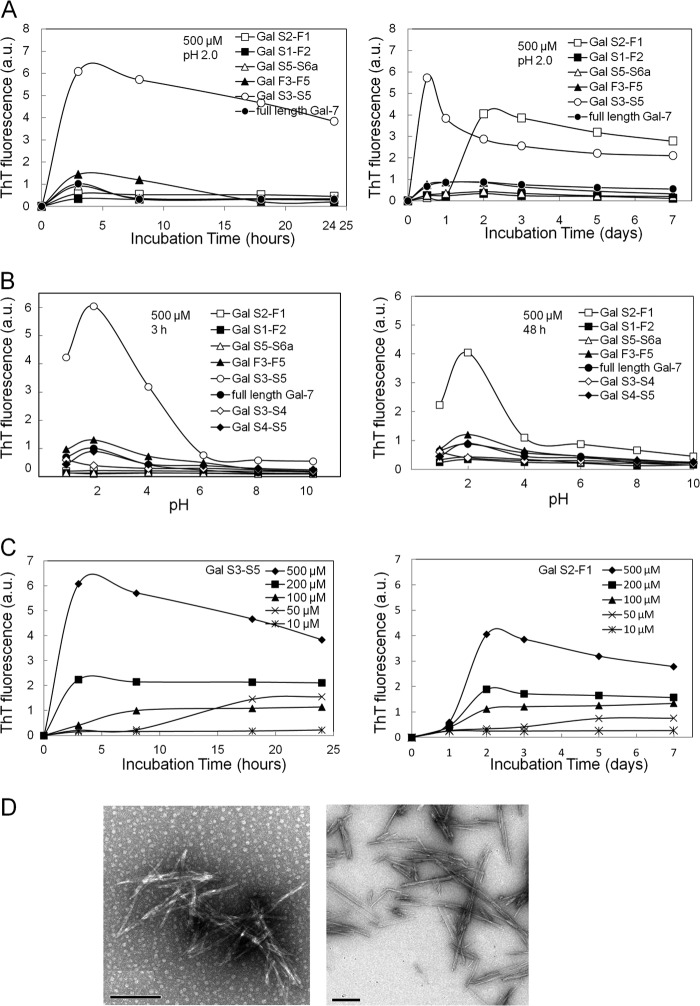

Gal-7 is characterized by 12 β-strand fragments with 5 paired structures (S1/F1, S2/F2, S3/F3, S4/F4, and S5/F5) (Fig. 2A). Seven species of Gal-7 peptides containing two or three sequential β-strand fragments (Gal S1-F2, Gal S3-S4, Gal S4-S5, Gal S3-S5, Gal S5-S6a, Gal F3-F5, and Gal S2-F1) were synthesized (Fig. 2B) and their ThT fluorescence was determined as a function of their incubation times, pH values and doses (μm). Gal S3-S5 and Gal S2-F1 fragments (500 μm each) showed high ThT fluorescence at pH 2.0 after 3 h and 48 h incubations, respectively. After reaching maximal values, Gal S3-S5 and Gal S2-F1 had a gradual decrease during the 24-h and 7-day incubation periods, respectively. Full-length Gal-7 and other fragments, Gal S1-F2, Gal F3-F5, Gal S5-S6a, Gal S3-S4 (not shown), and Gal S4-S5 (not shown) (500 μm each), maintained low values for 7 days (Fig. 3A). The maximal ThT values of Gal S3-S5 and Gal S2-F1 (500 μm each) were obtained at pH 2.0 after 3- and 48-h incubation times, respectively. Other peptides (Gal S1-F2, Gal S5-S6a, Gal F3-F5, Gal S3-S4, and Gal S4-S5), including the full-length Gal-7 molecule, failed to show significant fluorescence in any pH ranges (Fig. 3B). Gal S3-S4 and Gal S4-S5 failed to form amyloid fibrils at pH 2.0 during the 7-day incubation (not shown), indicating that the three β-strand segments (S3, S4, and S5) are essential to forming amyloid aggregates. The dose-dependence of the ThT fluorescence with various doses (10–500 μm) of Gal S3-S5 and Gal S2-F1 fragments at pH 2.0 was determined. Maximal ThT fluorescence levels of both fragments were increased and the times to reaching equilibrium were shortened in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). Incubation of Gal S3-S5 (left panel) and Gal S2-F1 (right panel) fragments at pH 2.0 for 3 and 48 h, respectively, produced uniform non-branching needle-like structures with 15∼20 nm width and varied lengths (mostly ∼300 nm) that were consistent with amyloid fibrils based on the electron microscopy definitions (37) (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Amyloidogenic potentials of synthetic galectin-7 (Gal-7) segments. A, kinetic studies of the aggregation of various Gal-7 segments at pH 2.0. Gal-7 segments (500 μm each) were incubated at pH 2.0 for 3, 8, 18, and 24 h and 2, 3, 5, and 7 days. B, effect of pH on the ThT fluorescence of various Gal-7 segments. Gal-7 segments (500 μm each) were incubated at various pH ranges (pH 1∼10) for 3 h (left) or 48 h (right panel). C, dose-dependence of aggregation of amyloidogenic Gal-7 segments (Gal S3-S5 and Gal S2-F1) at pH 2.0. Gal S3-S5 (left) and Gal S2-F1 (right panel) at the doses of 10, 50, 100, 200, and 500 μm were incubated for 3–24 h or for 1–7 days, respectively. D, electron micrographs of Gal S3-S5 (left) and Gal S2-F1 (right panel) incubated at pH 2.0 for 3 and 48 h, respectively. Bars; 200 nm.

Synthetic peptides containing the β-strand domain (Leu8-Pro38, Val35-Lys68, Gly150-Leu178, and Lys238-Ile250) of the actin molecule did not have a significant elevation of ThT fluorescence at any pH for 48 h (not shown).

Aggregation of Various Analogs of Gal S3-S5 (Ser31-Gln67) and Gal S2-F1 (Arg120-Phe136) Segments

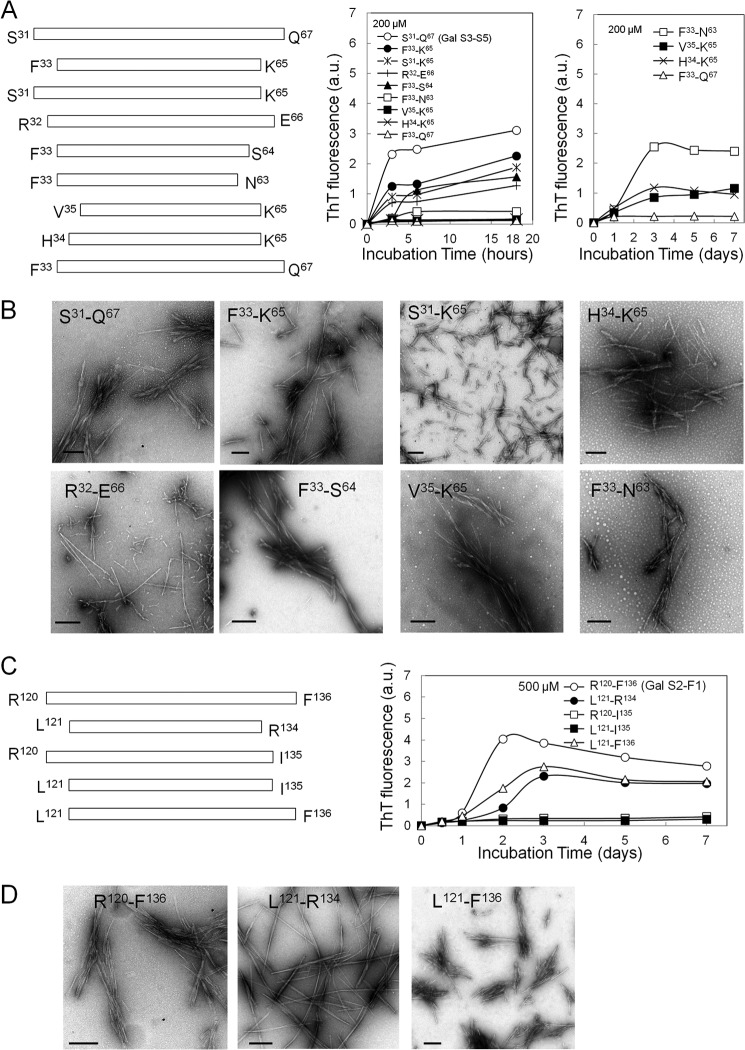

We further prepared various analogs of Gal S3-S5 and Gal S2-F1 fragments to know the sequence required for amyloidogenic potential. The peptides that were analogous to Gal S3-S5 (Ser31-Gln67), Phe33-Lys65, Ser31-Lys65, Arg32-Glu66, Phe33-Ser64, Phe33-Asn63, Val35-Lys65, Val35-Lys65, Phe33-Gln67, and His34-Lys65, and those that were analogous to Gal S2-F1 (Arg120-Phe136), Leu121-Arg134, Arg120-Ile135, Leu121-Ile135, and Leu121-Phe136, were synthesized (Fig. 4, A and C, left panel). Phe33-Lys65, Ser31-Lys65, Phe33-Ser64, and Arg32-Glu66 (200 μm each) showed considerable but relatively lower amyloidogenic potentials than those from the Ser31-Gln67 fragment for the initial 18 h maintaining the high ThT values for 7 days (not shown), whereas Phe33-Asn63, Val35-Lys65 and His34-Lys65 exhibited an increased ThT level for 3, 5, and 7 days after a lag time of 1 day. Phe33-Gln67 had the lowest amyloidogenic potential for the 7-day incubation (Fig. 4A, right panel). The fragments with a high ThT fluorescence were found to have varied appearances that depended on the peptide size and amino acid residues at both the N- and C- terminal ends by electron microscopy (Fig. 4B). The Leu121-Phe136 and Leu121-Arg134 fragments showed considerable amyloidogenic potentials with lower ThT levels than Arg120-Phe136, while Arg120-Ile135 and Leu121-Ile135 had the lowest amyloidogenic activity (Fig. 4C, right panel). Amyloid fibrils with various morphologies that were formed from Arg120-Phe136, Leu121-Arg134, and Leu121-Phe136 were observed on an electron microscope (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of amyloidogenic potentials of Gal S3-S5 (Ser31-Gln67) and Gal S2-F1 (Arg120-Phe136) analogs. A, peptides analogous to Gal S3-S5 (Ser31-Gln67), Phe33-Lys65, Ser31-Lys65, Arg32-Glu66, Phe33-Ser64, Phe33-Asn63, Val35-Lys65, His34-Lys65, and Phe33-Gln67, were synthesized (left panel). The peptides (200 μm) were incubated in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0 containing 100 mm NaCl at 37 °C for 3, 6, and 18 h and 1, 3, 5, and 7 days (right panel). The peptides with rapid increase of ThT at an early time (3–6 h) in the left panel were excluded from the right panel. B, electron micrographs of amyloid fibrils produced by Gal S3-S5 analogs. Bars; 200 nm. C, peptides analogous to Gal S2-F1 (Arg120-Phe136); Leu121- Arg134, Arg120-Ile135, Leu121-Ile135, and Leu121-Phe136 were synthesized (left panel). The peptides (500 μm) were incubated in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0 containing 100 mm NaCl at 37 °C for 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 days (right panel). D, electron micrographs of the amyloid fibrils produced by Gal S2-F1 analogs. Bars indicate 200 nm.

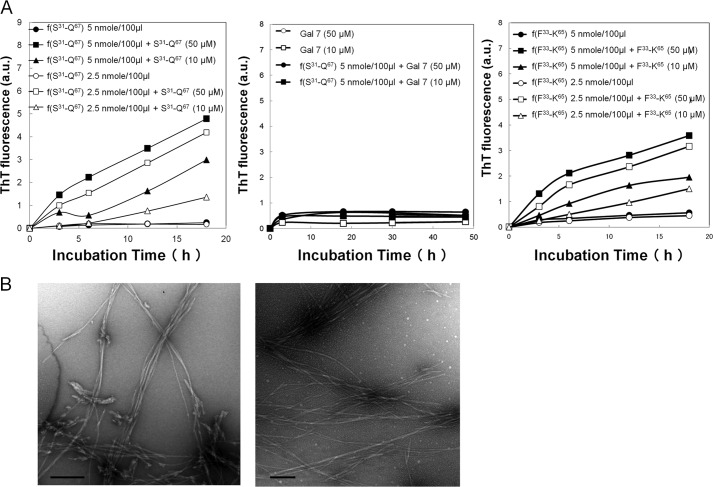

Extension Reaction of Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 Aggregates

Kinetic studies of the extension reaction focused on the Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 peptides. When soluble Ser31-Gln67 (10 or 50 μm) and sonicated Ser31-Gln67 aggregates, f(Ser31-Gln67) (2.5 or 5 nmol/100 μl), were incubated at pH 2.0 for 3, 6, 12, and 18 h, the intensities of ThT fluorescence became higher than those of Ser31-Gln67 alone (see Fig. 3C, left panel) and f(Ser31-Gln67) alone (Fig. 5A, left panel). No significant increase of ThT fluorescence was observed at pH 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, and 10.0 (not shown). When the Gal-7 molecule (10 or 50 μm) was incubated with sonicated f(Ser31-Gln67) (5 nmol/100 μl) at pH 2.0 for 3, 18, 30, and 48 h, no increase in fluorescence was observed (Fig. 5A, middle panel). The combination of soluble Phe33-Lys65 (10 or 50 μm) and f(Phe33-Lys65) (2.5 or 5 nmol/100 μl) at pH 2.0 also gave higher ThT values than the individual soluble or fibril forms (Fig. 5A, right panel). Electron microscopic studies demonstrated that the amyloid fibrils that formed after incubation with the soluble form (Ser31-Gln67 or Phe33-Lys65 peptide) at pH 2.0 appeared to be extended (Fig. 5B) compared with the fibrils that were composed of their respective monomers (See Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 5.

Deposition of soluble Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 peptide onto its respective fibrils (seeds). A, reaction mixtures of Ser31-Gln67 (50 or 10 μm) plus sonicated f(Ser31-Gln67) (2.5 or 5 nmol/100 μl) (left panel), Gal-7 molecule (50 or 10 μm) plus sonicated f(Ser31-Gln67) (5 nmol/100 μl) (middle panel), and Phe33-Lys65 (50 or 10 μm) plus sonicated f(Phe33-Lys65) (2.5 or 5 nmol/100 μl) (right panel) were incubated for 3, 6, and 18 h or 30 and 48 h in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0, containing 100 mm NaCl, and then the ThT fluorescence intensities were measured. B, electron micrographs of reaction mixtures composed of f(Ser31-Gln67) (5 nmol/100 μl) plus Ser31-Gln67 (50 μm) (left panel) and f(Phe33-Lys65) (5 nmol/100 μl) plus Phe33-Lys65 (50 μm) (right panel) after 18 h of incubation. Bars; 500 nm.

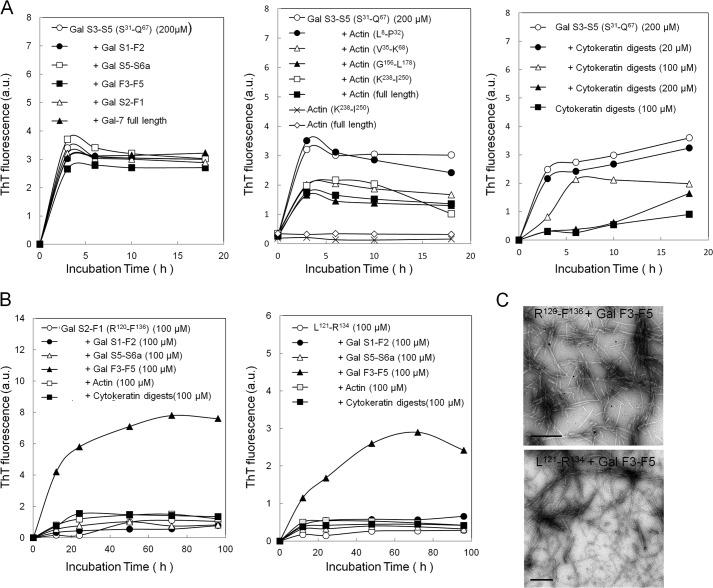

Modulation of Amyloidogenic Peptides of Gal-7 (Ser31-Gln67, Phe33-Lys65, Arg120-Phe136, Leu121-Arg134) by Gal-7 Peptides, Actin, and Cytokeratin Fragments

Because Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins have been identified as the major constituents of amyloid deposits of PLCA, we studied the association of amyloidogenic fragments of Gal-7 with these constituents.

Amyloidogenesis of Ser31-Gln67 at an amyloidogenic dose (200 μm) remained unchanged in the presence of Gal-7 fragments (Gal S1-F2, Gal S5-S6a, Gal F3-F5, and Gal S2-F1) and Gal-7 molecule (Fig. 6A, left panel), but this process was suppressed by some actin fragments containing β-strand peptides (Val35-Lys68, Gly150-Leu178, and Lys238-Ile250) as well as full-length actin, which was not true for Leu8-Pro32 peptide (Fig. 6A, middle panel). The ThT levels of Lys238-Ile250 and the actin molecule as well as other β-strand peptides of actin (Leu8-Pro32, Val35-Lys68, and Gly156-Leu178) were constantly low for 18 h (not shown). Tryptic digests of insoluble cytokeratins (20–200 μm) inhibited the aggregation of Ser31-Gln67 (200 μm) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A, right panel). Phe33-Lys65, an analogous peptide of Ser31-Gln67, gave similar results as Ser31-Gln67 (not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Modulation of aggregation of amyloidogenic Gal-7 fragments. A, amyloidogenic fragment Ser31-Gln67 (Gal S3-S5) (200 μm) was incubated for 3, 6, 10, and 18 h in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0, containing 100 mm NaCl at 37 °C in the presence of Gal-7 fragments (Gal S1-F2, Gal S5-S6a, Gal F3-F5, Gal S2-F1) (200 μm each) and Gal-7 molecule (200 μm) (left panel), synthetic actin fragments containing β-strand peptides (Leu8-Pro32, Val35-Lys68, Gly150-Leu178, and Lys238-Ile250) (200 μm each) and actin molecule (200 μm) (middle panel), and tryptic fragments of insoluble cytokeratins (20–200 μm) (right panel). B, amyloidogenic fragments Arg120-Phe136 (Gal S2-F1) (left panel) and Leu121- Arg134 (right panel) at low amyloidgenic dose (100 μm) were incubated in 50 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0 containing 100 mm NaCl at 37 °C in the presence of Gal-7 fragments (Gal S1-F2, Gal F3-F5, and Gal S5-S6a) (100 μm each), actin molecule (100 μm) and cytokeratin digests (100 μm) for 10, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. C, amyloid fibrils formed in the reaction mixtures composed of Arg120-Phe136 and Gal F3-F5 (upper panel) or Leu121- Arg134 and Gal F3-F5 (lower panel) were observed by electron microscopy. Scale bars indicate 200 nm.

We examined the effects of the proteins (Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins) on the amyloidogenic peptides, Arg120-Phe136, Leu121-Arg134, and Leu121-Phe136, at their non-amyloidogenic dose (100 μm). Amyloidogeneses of Arg120-Phe136 and its analogs Leu121-Arg134 were increased in the presence of the Gal F3-F5 (Gly84-Arg113) fragment, a putative tryptic peptide, but this process was not increased in the presence of other Gal-7 fragments (Gal S1-F2 and Gal S5-S6a) or actin molecule and cytokeratin digests (100 μm each) (Fig. 6B, left and right panels). Amyloidogenesis of Leu121-Phe136 was also increased in the presence of Gly84-Arg113 to the same extent as Arg120-Phe136 and Leu121-Arg134 (not shown). Electron microscopic observation revealed that typical amyloid fibrils with extended filamentous structures, compared with those composed of Arg120-Phe136, Leu121-Arg134, or Leu121-Phe136 alone (see Fig. 4D), were produced by the combinations of Arg120-Phe136/Gal F3-F5 and Leu121-Arg134/Gal F3-F5 (Fig. 6C).

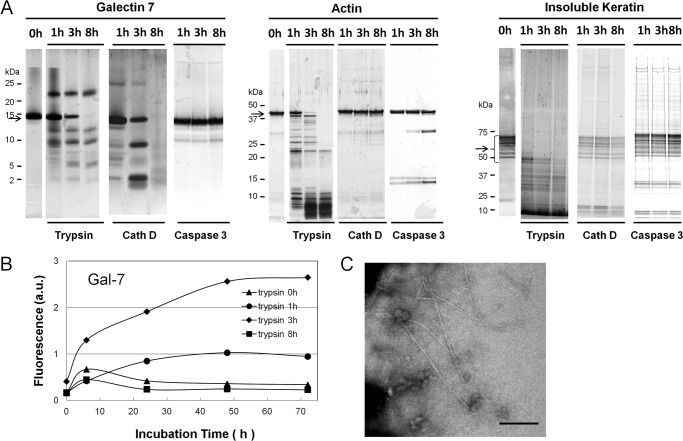

In Vitro Amyloid Fibril Formation of Protease-digested Fragments of Gal-7

Because proteolytic fragments of amyloid precursor proteins such as Aβ and β2-microglobulin have been shown to be more amyloidogenic than intact proteins (39, 40), we re-examined the amyloidogenesis of the degradation products of three candidate proteins (Gal-7, actin, and insoluble cytokeratins) that are produced by the digestion with major apoptosis-related proteases of keratinocytes, including trypsin, cath D, and caspase 3. The degradation patterns of these proteins by trypsin, cath D, and caspase 3 are shown in Fig. 7A. Incubation of the degradation products of Gal-7 at pH 2.0 obtained after 3-h trypsin treatment showed increased ThT fluorescence during the 72-h incubation, but the degraded fragments after 1- and 8-h trypsin treatments did not (Fig. 7B). Gal-7 fragments, obtained by cath D and caspase 3, as well as actin and cytokeratin fragments, obtained by the digestions with three proteases, demonstrated no significant increase in ThT fluorescence (not shown). Electron microscopy of samples taken from 3-h trypsin digests after 72-h incubation at pH 2.0 showed straight non-branching amyloid-like structures (Fig. 7C), which was not the case for other samples from 1- and 8-h trypsin digests (not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Detection of amyloidogenic peptide in proteolytic fragments of Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins. A, proteolytic patterns of Gal-7, actin, and insoluble cytokeratins with trypsin, cathepsin D (Cath D) and caspase 3. Gal-7 (200 μg) (left), actin (200 μg) (middle) and insoluble cytokeratins (300 μg) (right panel) were digested with trypsin, cath D, or caspase 3 at room temperature or 37 °C for 1, 3, and 8 h at their optimal pH. The digests were resolved on SDS-PAGE and then visualized with silver stain. Arrows on the left side of each panel indicate the migration positions of Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins, respectively. B, ThT fluorescence of trypsin digests of Gal-7. Aliquots of 0, 1, 3, and 8 h-tryptic digests were incubated in 100 mm citrate buffer, pH 2.0, containing 100 mm NaCl at 37 °C for 0, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h. C, electron microscopic observation of tryptic digests of Gal-7. Aliquot of 3 h trypsin digests after 72 h incubation was taken and subjected to electron microscopic analysis. Bar; 200 nm.

DISCUSSION

Amyloidogenesis of Gal-7, Actin, and Cytokeratin Molecules

Determination of the amyloidogenic potentials of Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratin molecules in vitro revealed that Gal-7 alone showed an increase in fluorescence at an acidic pH (pH 2.0), and the increase was not enough to form typical amyloid fibrils, which is possibly because of the incomplete steric interaction between the β-strand peptides of the Gal-7 molecule (41, 42). Specific short peptides of amyloidogenic proteins, rather than full-length molecules, easily aggregate to form amyloid fibrils. For instance, in Aβ of Alzheimer disease highly amyloidogenic peptides 1–40 and 1–42 are processed from non-pathological amyloid precursor protein (APP) (43), and, in β2-microglobulin of dialysis amyloidosis, specific peptides (Ser20-Lys41 or Asp59-Thr71) form amyloid fibrils more readily than intact β2-microglobulin molecule (33, 40, 44). This suggests that the fragments of Gal-7, actin, or cytokeratins, even though their full-length molecules have little to no amyloidogenic properties, may exhibit strong amyloidogenesis. To examine this possibility, the amyloidogenic potentials of 1) synthetic peptides with β-strand fragments of Gal-7 and actin, and 2) proteolytic fragments of candidate proteins (Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins) produced by apoptosis-related proteases (trypsin, cath D, and caspase-3) were determined.

Amyloidogenesis of Synthetic Peptides

Of the synthetic peptides of Gal-7 molecule, Gal S3-S5 (Ser31-Gln67) and Gal S2-F1 (Arg120-Phe136) showed strong amyloidogeneses at pH 2.0 with the lag time of 3 h and 48 h, respectively (see Fig. 3C). Kinetic studies on aggregation using various Ser31-Gln67 analogs showed that the Phe33-Lys65 and Ser31-Lys65 variants that lack two amino acid residues at both ends and at the C-terminal end, respectively, were capable of maintaining their amyloidogenic potential, whereas Phe33-Gln67 lacking N-terminal two amino acid residues did not express any amyloidogenesis at least within 7 days (see Fig. 4A). This indicates that 1) Ser31-Gln67 has the highest aggregation activity, 2) Phe33-Lys65 seems to be the minimum sequence required for maintaining a high aggregation potential, because variants of Phe33-Lys65 lacking one or two amino acid residues at N-terminal (His34-Lys65 and Val35-Lys65) or C-terminal end (Phe33-Asn63 and Phe33-Ser64) all show lower aggregation potentials, and 3) the N-terminal two amino acid residues of Ser31-Gln67 (Ser31-Arg32) seem to have a promoting potential whereas C-terminal two residues (Glu66-Gln67) have an inhibiting activity, when variants of Ser31-Gln67 lacking two amino acid residues at N- or C-terminal end (Phe33-Gln67, Ser31-Gln67, and Ser31-Lys65) are compared. Among the analogs of the Gal S2-F1 fragment (Arg120-Phe136), Leu121-Phe136, and Leu121-Arg134 were amyloidogenic, compared with Arg120-Ile135 and Leu121-Ile135, for the 7-day incubation, indicating that the C-terminal amino acid residue of Arg120-Phe136 is important for amyloidogenesis. It is of particular interest that amyloidogenic peptides, Phe33-Lys65, Leu121- Phe136, and Leu121-Arg134, are all putative tryptic peptides (See Fig. 2B); therefore, several amyloidogenic fragments may be released after the digestion of Gal-7 with trypsin-like enzymes, although the tryptic cleavage sites Arg54 and Arg134 are located in the Phe33-Lys65 and Leu121-Phe136 peptides, respectively, and their susceptibilities to the trypsin-like enzymes of keratinocytes are unknown. These in vitro studies using synthetic peptides suggest that tryptic degradation of Gal-7 will play a major role in amyloidogenesis of PLCA.

Amyloidogenesis of Proteolytic Fragments

We next examined whether the mixture of degraded peptides of Gal-7 obtained after trypsin digestion (1–8 h) might be amyloidogenic. Gal-7 fragments produced by trypsin under the restricted condition of 3 h digestion were amyloidogenic. The digestion time-dependent amyloidogenesis suggests that the susceptibilities of the cleavage sites (a total of 16 sites) of Gal-7 to trypsin are not the same. The K and R residues (Lys7, Arg21, Arg23, Arg54, Lys65, Arg75, Lys99, Arg111, and Arg134) located inside the β-sheet domains will be relatively resistant to trypsin because the tertiary structure of β-sheet may inhibit the access of the enzyme compared with Arg83, Arg113, Arg118, and Arg120, which are located outside the β-sheet domains (See Fig. 2B), except Arg15 and Arg72, which are difficult to cleave because their C-terminal amino acid residues are acidic (P and E, respectively) (45). During the short incubation time (3 h), the peptides, Gly84- Arg113 and Leu121-Phe136, of which tryptic cleavage sites are outside the β-sheet domains will be released; the latter peptide is shown to be amyloidogenic and the former peptide, although not amyloidogenic by itself, potentially stimulates Leu121-Phe136 to form amyloid fibrils (see Fig. 6B). As digestion progresses (8 h), the tryptic sites inside the β-sheet domains begin to be cleaved, resulting in the degradation of the Gly84-Arg113 peptide by the tryptic sites (Lys99 and Arg111) located inside the peptide and the production of Leu121-Arg134 peptide with a relatively low amyloidogenic potential (see Fig. 4C). These hypotheses seem to explain well why limited trypsin treatment for 3 h produces amyloid fibrils. Keratinocytes do not express pancreatic type trypsin (trypsinogens 1 and 2), but they do produce trypsinogens 4 and 5 and KLKs. Their functions and substrate specificities have not been fully elucidated, but among them, KLK 4, 5, 6, and 8 are known to exhibit trypsin-like specificity (17, 18). Although the identification of the tryptic enzymes involved in Gal-7 degradation in vivo and the possibility of the involvement of other species of caspases and cathepsins still remain to be determined, the present studies suggest that at least limited degradation of Gal-7 by tryptic enzymes is involved in the production of amyloidogenic fragments in PLCA.

Amyloid Fibril Extension

We used Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 fragments in the extension studies. Amyloidogenic peptides, Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 monomers were both capable of depositing on their respective preformed aggregates and of elongating the amyloid fibrils, suggesting that amyloid fibrils consisting of Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 peptides are formed via two steps, seed formation (the assembly of monomeric amyloid protein into a template) and extension (the growth of the template by depositions of additional monomeric amyloid protein) (20). However, incubation of the intact Gal-7 molecule in the presence of f(Ser31-Gln67) or f(Phe33-Lys65) failed to increase the rate of elevation of ThT fluorescence. This is in contrast with dialysis amyloidosis in which the combination of the K3 (Ser20-Lys41 peptide) seed and intact β2M monomer resulted in the extension of amyloid fibrils (33, 38), suggesting that intact Gal-7 cannot be a promoter for amyloid fibril extension and that degradation of Gal-7 is essential for the extension of amyloid fibrils.

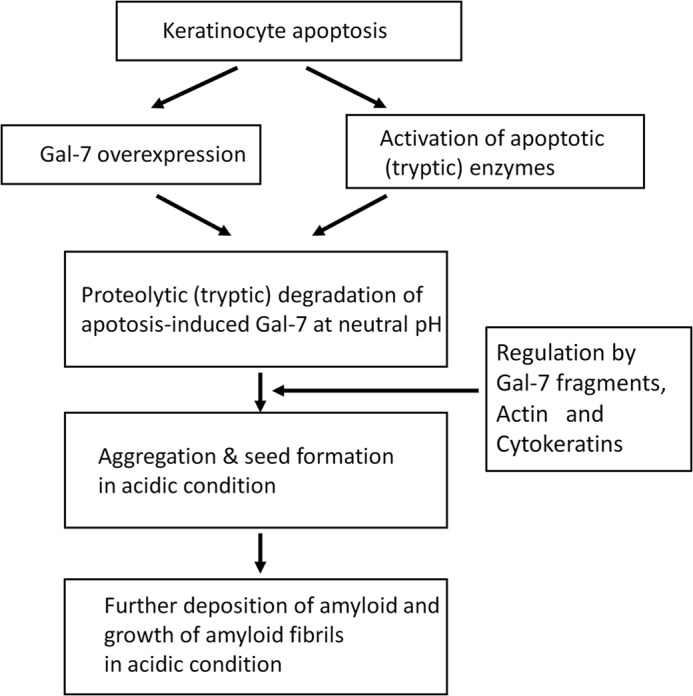

Acidified Condition of Apoptotic Cell

The optimal pH for amyloid fibril formation by galectin-7 segments (Ser31-Gln67, Phe33-Lys65, Arg120-Phe136, Leu121- Arg134, etc.) was acidic (pH 2.0), which is not physiological. However, cytoplasmic acidification is now recognized as a general feature of apoptosis in a variety of cell lines, including neutrophils, T-lymphocytes and leukemia cells. Because intracellular acidification, resulting from pH dysregulation, which is in turn due to dephosphorylation of protein exchangers, occurs at early stages of apoptosis (46–48), amyloidogenic galectin-7 segments should be produced by tryptic enzymes at neutral pH prior to amyloid fibril formation in the intracellular acidified conditions. Previous report that intracellular acidification of apoptosis is preceded by protease (including caspases) activation and that inhibition of the protease activity prevents cytoplasmic acidification in Jurkat T-lymphoblasts (49), strongly suggests a close relationship between apoptosis-induced proteolysis and subsequent cytoplasmic acidification. This supports our hypothesis on the mechanism of amyloid fibril formation in PLCA, which will be discussed for Fig. 8.

FIGURE 8.

Possible mechanisms of amyloid fibril formation in PLCA.

Regulation of Amyloid Fibril Deposit

Apoptotic cells will be replaced by amyloid fibrils via complex and multi-step processes. Apoptotic cell death in the epidermis is frequently detected in skin disorders that are unrelated to PLCA, including lichen planus, lupus erythematodes, drug reaction, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and sun-burn (50). Ovoid, PAS-positive eosinophilic apoptotic bodies of various shapes and sizes that have generally been referred to cytoid bodies or Civatte bodies are often observed close to the epidermis or sometimes in the epidermis of these disorders (51), suggesting that apoptotic changes of the epidermis do not always lead to amyloid fibril deposition, but the conversion from apoptotic keratinocytes to amyloid deposition occurs only in the restricted condition. The rate of amyloidogenesis of Gal-7 fragments (Ser31-Gln67, Arg120-Phe136, etc.) was dependent on the content of each Gal-7 fragment (see Fig. 3C), which is controlled by the degree of Gal-7 induction during epidermal apoptosis. We found that limited trypsin treatment (3 h) of Gal-7 was the best condition for the production of amyloidogenic peptides (See Fig. 7B), indicating that appropriate tryptic enzyme activity is crucial for amyloid fibril formation. Additionally, the amyloidogeneses of Ser31-Gln67 and Phe33-Lys65 fragments were inhibited by other amyloid constituents (actin and cytokeratin fragments) of PLCA, whereas the amyloidogenic potentials of Arg120-Phe136, Leu121-Phe136, and Leu121-Arg134 were stimulated in the presence of the Gal F3-F5 fragment (see Fig. 6). Thus, the aggregation of Gal-7 fragments in PLCA is regulated by many factors, including the apoptosis-induced Gal-7 level, activities of apoptosis-related tryptic enzymes and amyloid constituents (Gal-7, actin, and cytokeratins).

Familial Primary Localized Cutaneous Amyloidosis

Most cases of PLCA are the non-familial, acquired type, but rare cases of familial PLCA (FPLCA) with autosomal-dominant inheritance have been reported (52). Recent genetic analysis has revealed missense mutations in the oncostatin M receptor-β (OSMR) or interleukin-31 receptor A (IL31RA) gene, which can form a heterodimeric receptor together through IL31 signaling. OSMRβ or IL31RA signaling is related to the reduction of signal for keratinocyte apoptosis (53); therefore, genetic defects in the signaling will induce keratinocyte apoptosis. The mechanism by which these mutations are related to Gal-7 is unknown. The subcellular localization of Gal-7 is variable; it can be located in the intracellular or extracellular space and sometimes on the plasma membrane (22), depending on the cellular conditions. Gal-7 may be directly or indirectly involved in the OSMRβ/IL31RA signaling pathway during keratinocyte apoptosis (28), resulting in the abnormal metabolism of Gal-7 in FPLCA keratinocytes.

Finally, the basic mechanism for promoting amyloid fibril formation in PLCA may be summarized as follows (Fig. 8); 1) induction of keratinocyte apoptosis by UV irradiation and more, 2) induction of Gal-7 expression and activation of apoptosis-related proteases, 3) production of amyloidogenic peptides of Gal-7 by apoptosis-related proteases, including trypsin-like enzymes at neutral pH, 4) aggregation of amyloidogenic peptides in the acidic condition, 5) the aggregation is modulated by Gal-7 peptides, actin and cytokeratins, and 6) growth of amyloid fibrils by deposition of additional Gal-7 fragments.

This study is the first step for understanding the pathogenesis of PLCA. To confirm the amyloidogenic mechanism of Gal-7, further studies will be necessary to identify the species of Gal-7 peptides that accumulate in the lesional skin of PLCA. The roles of actin and cytokeratins in amyloid fibril formation of PLCA also should be clarified.

Footnotes

- PLCA

- primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis

- β-ME

- β-mercaptoethanol

- CHAPS

- 3-(3-cholamidepropyl) dimethylammonio-1- propanesulphonate

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- PMSF

- phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

- ThT

- thioflavin T

- TUNEL

- TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hashimoto K. (1984) Progress on cutaneous amyloidosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 82, 1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kobayashi H., Hashimoto K. (1983) Amyloidogenesis in organ-limited cutaneous amyloidosis: an antigenic identity between epidermal keratin and skin amyloid. J. Invest. Dermatol. 80, 66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inoue K., Takahashi M., Hamamoto Y., Muto M., Ishihara T. (2000) An immunohistochemical study of cytokeratins in skin-limited amyloidosis. Amyloid. 7, 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hintner H., Booker J., Ashworth J., Auböck J., Pepys M. B., Breathnach S.M. (1988) Amyloid P component binds to keratin bodies in human skin and to isolated keratin filament aggregates in vitro. J. Invest. Dermatol. 91, 22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steinert P. M., Roop D. R. (1988) Molecular and cellular biology of intermediate filaments. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57, 593–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glenner G. G. (1980) Amyloid deposits and amyloidosis: The β-fibrillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 302, 1283–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miura Y., Harumiya S., Ono K., Fujimoto E., Akiyama M., Fujii N., Kawano H., Wachi H., Tajima S. (2013) Galectin-7 and actin are components of amyloid deposit of localized cutaneous amyloid. Exp. Dermatol. 22, 36–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breathnach S. M., Bhogal B., Dyck R. F., De Beer F. C., Black M. M., Pepys M. B. (1981) Immunohistochemical demonstration of amyloid P component in skin of normal subjects and patients with cutaneous amyloidosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 105, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furumoto H., Shimizu T., Asagami C., Muto M., Takahashi M., Hoshii Y., Ishihara T., Nakamura K. (1998) Apolipoprotein E is present in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 111, 417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang Y. T., Wong C. K., Chow K. C., Tsai C. H. (1999) Apoptosis in primary cutaneous amyloidosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 140, 210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumakiri M., Hashimoto K. (1979) Histogenesis of primary localized amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J. Invest. Dermatol. 73, 150–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhivotovsky B., Burgess D. H., Vanags D. M., Orrenius S. (1997) Involvement of cellular proteolytic machinery in apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 230, 481–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang H. Q., Quan T., He T., Franke T. F., Voorhees J. J., Fisher G. J. (2003) Epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent, NF-κB-independent activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway inhibits ultraviolet irradiation-induced caspases-3, -8, and -9 in human keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45737–45745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuwabara I., Kuwabara Y., Yang R. Y., Schuler M., Green D. R., Zuraw B. L., Hsu D. K., Liu F. T. (2002) Galectin-7 (PIG 1) exhibits pro-apoptotic function through JNK activation and mitochondrial cytochrome c release. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3487–3497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kågedal K., Johansson U., Ollinger K. (2001) The lysosomal protease cathepsin D mediates apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. FASEB J. 15, 1592–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conus S., Pop C., Snipas S. J., Salvesen G. S., Simon H. U. (2012) Cathepsin D primes caspase-8 activation by multiple intrachain proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 21142–21151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Debela M., Beaufort N., Magdolen V., Schechter N. M., Craik C. S., Schmitt M., Bode W., Goettig P. (2008) Structures and specificity of the human kallikrein-related peptidases KLK 4, 5, 6, and 7. Biol. Chem. 389, 623–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakanishi J., Yamamoto M., Koyama J., Sato J., Hibino T. (2010) Keratinocytes synthesize endopeptidase and multiple forms of trypsinogen during terminal differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 944–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marthinuss J., Andrade-Gordon P., Seiberg M. (1995) A secreted serine protease can induce apoptosis in Pam212 keratinocytes. Cell Growth Differ. 6, 807–816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Esler W. P., Stimson E. R., Mantyh P. W., Maggio J. E. (1999) Deposition of soluble amyloid-β onto amyloid templates: with application for the identification of amyloid fibril extension inhibitor. Methods Enzymol. 309, 350–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Naiki H., Gejyo F. (1999) Kinetic analysis of amyloid fibril formation. Methods Enzymol. 309, 305–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu F. T., Patterson R. J., Wang J. L. (2002) Intracellular functions of galectin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1572, 263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu F. T., Rabinovich G. A. (2010) Galectins: regulator of acute and chronic inflammation. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1183, 158–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Magnaldo T., Fowlis D., Darmon M. (1998) Galectin-7, a marker of all types of stratified epithelia. Differentiation. 63, 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leonidas D. D., Vatzaki E. H., Vorum H., Celis J. E., Madsen P., Acharya K. R. (1998) Structural basis for the recognition of carbohydrates by human galectin-7. Biochemistry. 37, 13930–13940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gendronneau G., Sidhu S. S., Delacour D., Dang T., Calonne C., Houzelstein D., Magnaldo T., Poirier F. (2008) Galectin-7 in the control of epidermal homeostasis after injury. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 5541–5549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bernerd F., Sarasin A., Magnaldo T. (1999) Galectin-7 overexpression is associated with the apoptotic process in UVB-induced sunburn keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11329–11334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hsu D. K., Yang R. Y., Liu F. T. (2006) Galectin in apoptosis. Methods Enzymol. 417, 256–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Madsen P., Rasmussen H. H., Flint T., Gromov P., Kruse T. A., Honoré B., Vorum H., Celis J. (1995) Cloning expression and chromosome mapping of human galectin-7. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 5823–5829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi C. Y., Takashima F. (2000) Rapid communication: nucleotide sequence of red seabream, Pagrus major, β-actin cDNA. J. Anim. Sci. 78, 2990–2991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jones J. C., Goldman A. E., Steinert P. M., Yuspa S., Goldman R. D. (1982) Dynamic aspects of the supramolecular organization of intermediate filament networks in cultured epidermal cells. Cell Motil. 2, 197–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Katagata Y., Aso K., Sato M., Yoshida T. (1992) Occurrence of differentiated keratin peptide (K1) in cultured human squamous cell carcinomas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 182, 1440–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ohhashi Y., Hasegawa K., Naiki H., Goto Y. (2004) Optimum amyloid fibril formation of a peptide fragment suggests the amyloidogenic preference of β2-microglobulin under physiological conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10814–10821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sasahara K., Yagi H., Naiki H., Goto Y. (2007) Heat-triggered conversion of protofibrils into mature amyloid fibrils of β2-microglobulin. Biochemistry. 46, 3286–3293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Naiki H., Higuchi K., Hosokawa M., Takeda T. (1989) Fluorometric determination of amyloid fibril in vitro using the fluorescent dye, thioflavin T. Anal. Biochem. 177, 244–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. LeVine H., 3rd (1999) Quantification of β-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 309, 274–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shirahama T., Cohen A. S. (1967) High resolution electron microscopic analysis of the amyloid fibril. J. Cell Biol. 33, 679–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamaguchi I., Hasegawa K., Naiki H., Mitsu T., Matuo Y., Gejyo F. (2001) Extension of Aβ2M amyloid fibrils with recombinant human β2-microglobulin. Amyloid. 8, 30–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jarrett J. T., Berger E. P., Lansbury P. T. (1993) The carboxy terminus of the β amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: Implication for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 32, 4693–4697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kozhukh G. V., Hagihara Y., Kawakami T., Hasegawa K., Naiki H., Goto Y. (2002) Investigation of a peptide responsible for amyloid fibril formation of β2-microgloblin by Achromobacter protease I. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1310–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Krebs M. R. H., Bromley E. H. C., Donald A. M. (2005) The binding of thioflavin-T to amyloid fibrils: localization and implications. J. Struct. Biol. 149, 30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Biancalana M., Koide S. (2010) Molecular mechanism of thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1804, 1405–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reinhard C., Hébert S. S., De Strooper B. (2005) The amyloid-beta precursor protein: integrating structure with biological function. EMBO J. 24, 3996–4006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jones S., Manning J., Kad N. M., Radford S. E. (2003) Amyloid-forming peptides from β2-microglobulin-Insights into the mechanism of fibril formation in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 325, 249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rodriguez J., Gupta N., Smith R. D., Pevzner P. A. (2008) Does trypsin cut before proline ? J. Proteome. Res. 7, 300–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gottlieb R. A., Giesing H. A., Zhu J. Y., Engler R. L., Babior B. M. (1995) Cell acidification in apoptosis: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor delays programmed cell death in neutrophils by up-regulating the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5965–5968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gottlieb R. A., Nordberg J., Skowronski E., Babior B. M. (1996) Apoptosis induced in Jurkat cells by several agents is preceded by intracellular acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 654–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li J., Eastman A. (1995) Apoptosis in an interleukin-2-dependent cytotoxic T lymphocyte cell line is associated with intracellular acidification. Role of the Na(+)/H(+)-antiport. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3203–3211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Meisenholder G. W., Martin S. J., Green D. R., Nordberg J., Babior B. M., Gottlieb R. A. (1996) Events in apoptosis. Acidification is downstream of protease activation and BCL-2 protection. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16260–16262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Elder D. E., Elenitsas R., Johnson B. L., Jr., Murphy G. F. (2005) LEVER'S Histopathology of the Skin, 9th Ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eto H., Hashimoto K., Kobayashi H., Fukaya T., Matsumoto M., Sun T. T. (1984) Differential staining of cytoid bodies and skin-limited amyloids with monoclonal anti-keratin antibodies. Am. J. Pathol. 116, 473–481 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Newton J. A., Jagjivan A., Bhogal B., McKee P. H., McGibbon D. H. (1985) Familial primary cutaneous amyloidosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 112, 201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arita K., South A. P., Hans-Filho G., Sakuma T. H., Lai-Cheong J., Clements S., Odashiro M., Odashiro D. N., Hans-Neto G., Hans N. R., Holder M. V., Bhogal B. S., Hartshorne S. T., Akiyama M., Shimizu H., McGrath J. A. (2008) Oncostatin M receptor-β mutations underlie familial primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 73–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]