Abstract

3D analysis of facial morphology has delineated facial phenotypes in many medical conditions and detected fine grained differences between typical and atypical patients to inform genotype–phenotype studies. Next-generation sequencing techniques have enabled extremely detailed genotype–phenotype correlative analysis. Such comparisons typically employ control groups matched for age, sex and ethnicity and the distinction between ethnic categories in genotype–phenotype studies has been widely debated. The phylogenetic tree based on genetic polymorphism studies divides the world population into nine subpopulations. Here we show statistically significant face shape differences between two European Caucasian populations of close phylogenetic and geographic proximity from the UK and The Netherlands. The average face shape differences between the Dutch and UK cohorts were visualised in dynamic morphs and signature heat maps, and quantified for their statistical significance using both conventional anthropometry and state of the art dense surface modelling techniques. Our results demonstrate significant differences between Dutch and UK face shape. Other studies have shown that genetic variants influence normal facial variation. Thus, face shape difference between populations could reflect underlying genetic difference. This should be taken into account in genotype–phenotype studies and we recommend that in those studies reference groups be established in the same population as the individuals who form the subject of the study.

Keywords: facial morphology, phylogenetics, dense surface models

Introduction

3D analysis of facial morphology using dense surface models (DSMs) has successfully delineated the facial phenotype of a variety of neurodevelopmental conditions and has attained high rates of discrimination between the face shape of affected and unaffected subgroups.1, 2 Using highly sensitive models of facial morphology, it has been possible to detect subtle differences in atypical patients and inform genotype–phenotype studies.3, 4 Advanced molecular genetic techniques have established increasingly detailed correlations between genotype and phenotype. It has been the subject of debate whether it is valid to distinguish ethnic or ancestral categories in such studies.5, 6, 7 Cavalli-Sforza et al proposed a phylogenetic tree dividing the world population into nine subpopulations: New Guinean and Australian, Pacific Islander, Southeast Asian, Northeast Asian, Arctic Northeast Asian, Amerind, European, North African and West Asian, and African.8, 9, 10 This subdivision is based on genetic polymorphism studies in various populations grouped by continental sub-areas. FST statistics compute genetic distance between populations by measuring the portion of total genetic variation attributed to differences between them.6 Smaller genetic distance, or FST, is observed when populations live in closer proximity, but morphological differences are observed even in populations with the same phylogenetic origin or who live in relatively close geographic proximity.8 Few investigators have addressed morphological differences between phylogenetically related populations.11, 12 Here, we aimed to determine morphological differences in the faces of two European Caucasian populations of close geographical proximity.

Materials and methods

Permission to perform the study was obtained from Medical Ethics Review Committees of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam and University College London. Both centers recruited scientific and medical professionals as well as unaffected parents. The scientific and medical recruited professionals were invited through internal ‘advertisement' mailing. Unaffected members of families with children with a genetic condition were recruited at patient meetings and outpatient clinics. The family members had tested negative for the genetic condition of the child. All study subjects received written patient information and subsequently provided written consent. The inclusion criteria were subjects who were from self-reported UK or Dutch descent up until the second degree of relatives. Study subjects who had undergone surgery or other treatments altering facial morphology were excluded. We captured 3D photogrammetric images of 400 Caucasian adults, 200 from the United Kingdom and 200 from The Netherlands (Dutch; Table 1). Eight Dutch adults were excluded (five females and three males) because of image quality or technical issues. The university scientific and hospital medical professionals made up 40% of the study population (157/392) and the unaffected parents of children with a molecularly proven genetic syndrome contributed 60% (235/392).

Table 1. Demographics of 392 recruits.

|

MALE (N=197) |

FEMALE (N=195) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK (N=100) | Dutch (N=97) | UK (N=100) | Dutch (N=95) | |

| Mean age (years) | 39.7 | 38.5 | 38.4 | 35.4 |

| Prof/family | 37/63 | 43/54 | 39/61 | 39/57 |

| Mean age (years) | 39/40 | 33/42 | 33/42 | 31/38 |

Prof=recruits from scientific and medical professionals; Family=recruits from unaffected family members attending clinics and support groups.

A DSM of all faces in the data set was generated as the set of principal component analysis modes covering 99% of shape variation from the overall mean face. DSM construction involved methods described in Supplementary Material. Animated morphs were generated from the face DSM. Mean Dutch male and female faces were normalised with respect to UK faces of the same sex. We investigated face shape discrimination at the individual face level using multi-folded cross-validation. The shape differences identified in the animations and heat map comparisons were also investigated for significance in terms of linear and angular measures (defined in Supplementary Table 2 and derived from landmarks shown in Supplementary Figure 1).

Results

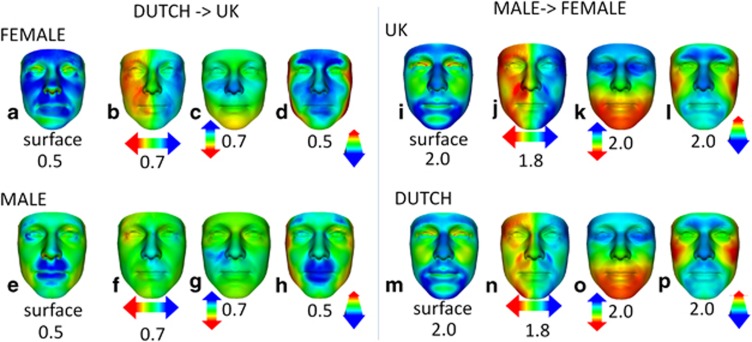

The animated morph between the mean Dutch female and mean UK female faces (Supplementary Movie_1.avi) showed the former to be broader and longer than the latter. Greater separation of outer canthi and nasal alae was noticeable, and the nose was shorter in the mean Dutch female face. The animated portrait morph between mean Dutch male face and mean UK male face (Supplementary Movie_2.avi) suggested the former to be broader at the exocanthi and temples. The profile view showed a more pronounced oral and supraorbital region in Dutch males compared with UK males. To determine the significance of differences visible in the animations, we normalised the mean Dutch male and mean Dutch female faces with respect to UK faces of the same sex (Figure 1). The red/green/blue spectrum of the heat map corresponds to contraction/coincidence/expansion or to translation difference along lateral/vertical/anterior–posterior axes of the surface being compared. The greater width and length of the mean Dutch female face are highlighted, respectively, in the lateral (Figure 1b: opposing red–blue at the left and right exocanthi at 0.7 SD) and vertical heat maps (Figure 1c: yellow on chin at 0.7 SD). The nasal shortness is shown in the vertical heat map (Figure 1b: blue nasal tip). Whereas in the surface normal comparison of the female Dutch and UK mean faces, there is widespread surface expansion reflecting greater face size (blue regions in Figure 1a), in the analogous male comparison, significant regions of expansion are largely peri-oral (Figure 1e). The greater separation of outer canthi in the Dutch to UK male mean face comparison is highlighted by opposing red–blue hues in Figure 1f. The vertical heat mapped comparison (Figure 1g) does not reflect a shorter nose in the mean Dutch male face at the same significance level as in the female comparison.

Figure 1.

Colour-coded heat-map comparisons. Heat-map comparisons showing the shape differences (red–green–blue colour code spectrums) of the Dutch mean female face normalised against all UK female faces (a–d), of the Dutch mean male face normalised against all UK male faces (e–h), of the UK mean male face normalised against all UK female faces (i–l) and of the Dutch mean male face normalised against all Dutch females (m–p). The first of each group of four columns is a heat-map comparison of the raw mean faces, reflecting displacement normal to the face surface. Heat-map comparisons parallel to three orthogonal axes are given in the second (x axis), third (y axis) and fourth (z axis) columns. Colour-coded differences are depicted in standard deviations and correspond to the colour scales at±the range indicated. In the male>female comparisons, the degree and regional location of differences between the Dutch and UK are very similar, except that the former are slightly reduced in degree. In the Dutch>UK comparisons, the differences for the female mean faces are greater and in different locations than those for the male mean faces.

Compared with the mean UK female face, the mean Dutch female face has as significant differences a greater face length, shorter nasal ridge length, greater nose width, greater nares anteversion, and as highly significant differences greater outer canthal separation and longer palpebral fissure width (Table 2). Relative to face length, the reduced nasal ridge and upper face lengths in the Dutch mean female face are both highly significantly different from the UK mean female face. Unlike females, the mean Dutch male face demonstrated an increased length that did not reach significance. In comparing faces of Dutch males to UK males, the anthropometric results confirm a significantly shorter nose relative to face length; greater separation of the outer canthi and both relatively and absolutely broader palpebral fissure width (Table 2).

Table 2. Differences in facial measurements between Dutch and UK.

| Dutch female | UK female | P | Dutch male | UK male | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face length (mm) | 113.7 | 111.9 | <0.05a | 122.8 | 122.4 | 0.68 |

| Nasal ridge length (mm) | 46.4 | 47.4 | <0.05a | 49.6 | 50.5 | 0.10 |

| Relative nasal ridge length | 0.41 | 0.42 | <0.0001b | 0.40 | 0.41 | <0.05a |

| Upper face proportion | 0.46 | 0.47 | <0.001b | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.06 |

| Nares anteversion | 0.82 | 0.83 | <0.05a | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.09 |

| Nose width (mm) | 33.4 | 32.7 | <0.05a | 36.3 | 36.9 | 0.15 |

| Outer canthal separation (mm) | 88.3 | 86.2 | <0.0005b | 92.3 | 90.6 | <0.005b |

| Palpebral fissure width (mm) | 28.3 | 27.3 | <0.001b | 29.5 | 28.8 | <0.005b |

| PBL relative to face length (mm) | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.24 | <0.05a |

Abbreviation: PBL, palpebral fissure width. Anthropometric calculations and t-tests were performed in Excel (Microsoft Office 2010).

Significant (P-value <0.05).

Highly significant (P-value <0.005, including <0.001 and <0.0001).

Subsequently, we investigated face shape discrimination at individual face level using multi-folded cross-validation and the closest mean pattern matching algorithm. To check there were no internal biases in each ethnicity-gender subgroup, we randomly partitioned them into an A and B subgroup and undertook 20-folded discrimination testing between the A and B subgroups. This was iterated five times and in each comparison DSM included principal component analysis modes covering 99% of shape variance from the mean. The area under the corresponding receiver operator characteristic curves and standard error of the mean (SEM) were computed for the 100 comparisons:

UK female A-B: 0.50±0.003 UK male A-B: 0.52±0.008

Dutch female A-B: 0.53±0.007 Dutch male A-B: 0.48±0.007

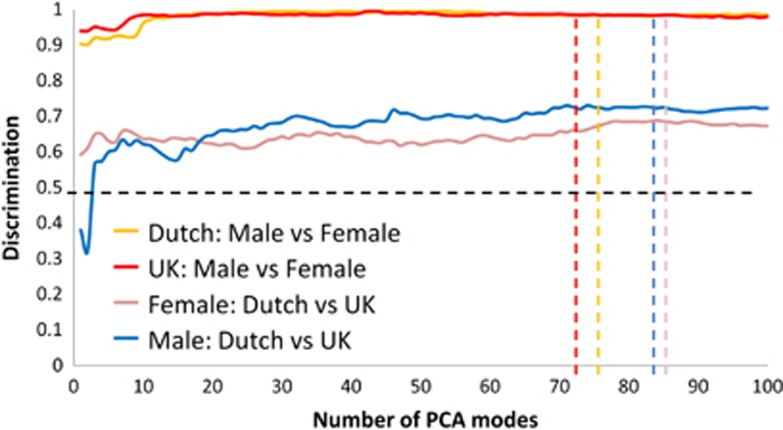

Each result is close to the expected chance rate of 0.5, supporting the hypothesis of lack of bias. As expected, discrimination between UK female and UK male faces and that between Dutch female and Dutch male faces was close to perfection (Figure 2). However, female UK-Dutch and male UK-Dutch comparisons produced much higher discrimination rates of 0.68 and 0.71, respectively, than the expected chance rate of 0.5. This confirmed that the average differences found were reproducible at the individual face level.

Figure 2.

Rates of discrimination between gender-ethnic subpopulations. In order to determine discrimination rates between the faces of particular sex-ethnicity subgroups multi-folded cross-validation was undertaken using closest mean classification. Overall discrimination was calculated as the mean of the AUC estimates for the multiple cross-validation results. AUC corresponds to the probability of correctly classifying a randomly selected pair of subjects, one from each classification subgroup. If there were no significant differences between the face shape of two subgroups being compared, then the expected AUC would be 0.5 as indicated by the horizontal broken line. The vertical broken lines indicate the number of modes in the dense surface models used corresponding to 99% of shape variation from the mean face.

Discussion

Dutch people are significantly taller than the UK population.13 Therefore, it is to be expected that Dutch and UK faces differ dimensionally.14, 15 The differences identified here, however, include differences based on both shape and proportion, and some are contrary to the greater height of Dutch individuals. Dutch women have significantly longer and broader faces compared with UK women; their palpebral fissure and nasal widths are significantly greater, their nasal ridge length and upper face proportion are significantly reduced; and their nares are significantly more anteverted. In particular, the nasal differences from UK women show that the nose in Dutch women is more likely to be shorter and more retroussé. Dutch men did not have significantly longer faces despite their greater height. Their nasal ridge length relative to face length is significantly shorter; and, relative to face length, they have longer palpebral fissures than UK men. Dutch and UK females show significant difference for nearly every measure, whereas for Dutch and UK males few measures show significant difference. This could be explained by sexual dimorphism, which would mean that overall Dutch and UK females differ more from each other than males do. Facial and cranial sexual dimorphism have been observed in many human populations.16, 17

It is unlikely that the differences in facial morphology we find between UK and Dutch populations were influenced by biased composition of the study group. For example, we recruited both medical/scientific professionals and family members covering a range of social backgrounds. The proportion of professionals to family members and the age ranges in both ethnic groups were comparable. Furthermore, we considered normalized mean difference of professionals from family members within ethnic groups. We also normalised the mean of the UK family members against UK medical/scientific professionals and detected no significant difference (Supplementary Figure 3A). We normalised Dutch family members against Dutch medical/scientific professionals producing minimal difference around the lips (especially the lower lips) and zygoma region (Supplementary Figure 3B). Neither of these comparisons shows any nasal bias, which reconfirms the differences we find between our Dutch and UK subgroups as both realistic and generalisable.

In the present study, we describe morphological differences between mean Dutch and UK faces. However, it is unlikely that there is a typical UK or typical Dutch face considering that multiple waves of invasion and immigration in both countries have likely dispersed individual traits. Undoubtedly, there may be regions or subpopulations where less mixing has occurred for geographical or religious reasons, but we have not studied such relatively isolated populations.

Face shape differences are an important determinant of phenotype variation in humans. Craniofacial development is a complex process determined by genetic regulation and genetic variants influence facial morphology in the general population.18, 19 Thus, face shape difference between populations reflects underlying genetic differences. Therefore, our findings indicate that different baselines for face shape norms for individual populations should be applied when considering craniofacial conditions. Genovese et al have shown how differences between populations can help identify genomic ‘missing pieces' in the reference human genome.20 They described the location of these ‘missing pieces' using the patterns of variations in sequences that were a result of the admixture of human populations.

Our findings could have fundamental implications for genotype–phenotype correlation studies: a so-called ‘Caucasian' reference group, encompassing subjects from even close geographical proximity, may not be sufficiently reliable. The morphological differences in phylogenetically related individuals from close geographical proximity described here suggest that in genetic studies reference groups should be established in the same population as the individuals who form the subject of the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants of the study. PH and MS received part funding from the US National Institute on Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) through a CIFASD developmental grant (http://www.CIFASD.org). SMJH was supported by the Tom Voûte Fund.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Hammond P, Hutton TJ, Allanson JE, et al. Discriminating power of localized three-dimensional facial morphology. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:999–1010. doi: 10.1086/498396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond P, Forster-Gibson C, Chudley AE, et al. Face-brain asymmetry in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:614–623. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassabehji M, Hammond P, Karmiloff-Smith A, et al. GTF2IRD1 in craniofacial development of humans and mice. Science. 2005;310:1184–1187. doi: 10.1126/science.1116142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond P, Hannes F, Suttie M, et al. Fine-grained facial phenotype-genotype analysis in Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:33–40. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race, Ethnicity, and Genetics Working Group The use of racial, ethnic, and ancestral categories in human genetics research. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:519–532. doi: 10.1086/491747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorde LB, Wooding SP. Genetic variation, classification and 'race'. Nat Genet. 2004;36:S28–S33. doi: 10.1038/ng1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Burchard E, Ziv E, Tang H.Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease Genome Biol 20023comment, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW. The application of molecular genetic approaches to the study of human evolution. Nat Genet. 2003;33 (Suppl:266–275. doi: 10.1038/ng1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Piazza A. Human genomic diversity in Europe: a summary of recent research and prospects for the future. Eur J Hum Genet. 1993;1:3–18. doi: 10.1159/000472383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Piazza A, Menozzi P, Mountain J. Reconstruction of human evolution: bringing together genetic, archaeological, and linguistic data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6002–6006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gor T, Kau CH, English JD, Lee RP, Borbely P. Three-dimensional comparison of facial morphology in white populations in Budapest, Hungary, and Houston, Texas. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau CH, Richmond S, Zhurov A, et al. Use of 3-dimensional surface acquisition to study facial morphology in 5 populations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:S56–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönbeck Y, Talma H, van Dommelen P, et al. The world's tallest nation has stopped growing taller: the height of Dutch children from 1955 to 2009. Pediatr Res. 2013;73:371–377. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter CJ. The correlation of facial growth with body height and skeletal maturation at adolescence. Angle Orthod. 1966;36:44–54. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1966)036<0044:TCOFGW>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello LC, Wood BA. Cranial variables as predictors of hominine body mass. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1994;95:409–426. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330950405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastir M, Godoy P, Rosas A. Common features of sexual dimorphism in the cranial airways of different human populations. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011;146:414–422. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes P, Walters M, Shriver MD, et al. Sexual dimorphism in multiple aspects of 3D facial symmetry and asymmetry defined by spatially dense geometric morphometrics. J Anat. 2012;221:97–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, van der Lijn F, Schurmann C, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies five loci influencing facial morphology in Europeans. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster L, Zhurov AI, Toma AM, et al. Genome-wide association study of three-dimensional facial morphology identifies a variant in PAX3 associated with nasion position. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Handsaker RE, Li H, et al. Using population admixture to help complete maps of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2013;45:406–414. doi: 10.1038/ng.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.