Abstract

p38 MAPK signaling controls cell growth, proliferation, and the cell cycle under stress conditions. However, the function of p38 activation in tumor metastasis is still not well understood. We report that p38 activation in breast cancer cells inhibits tumor metastasis but does not substantially modulate primary tumor growth. Stable p38 knockdown in breast cancer cells suppressed NF-κB p65 activation, inhibiting miR-365 expression and resulting in increased IL-6 secretion. The inhibitory effect of p38 signaling on metastasis was mediated by suppression of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) migration to the primary tumor and sites of metastasis, where MSCs can differentiate into cancer-associated fibroblasts to promote tumor metastasis. The migration of MSCs to these sites relies on CXCR4-SDF1 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Analysis of human primary and metastatic breast cancer tumors showed that p38 activation was inversely associated with IL-6 and vimentin expression. This study suggests that combination analysis of p38 MAPK and IL-6 signaling in patients with breast cancer may improve prognosis and treatment of metastatic breast cancer.

Keywords: p38 MAPK, Breast cancer, Metastasis, microRNA, IL-6

Introduction

Among all cancer types, breast cancer has one of the highest metastatic rates. Annually, around 1.5 million patients are newly diagnosed with breast cancer, and 30,000 patients die from their disease. Various factors, which include the tumor stromal environment, cytokine secretion, and key signaling transduction events, have been reported to contribute to breast cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis 1. Tumor stromal tissue, a heterogeneous cell population including endothelial cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and myeloid-derived suppressive cells, plays an important role in tumorigenesis and metastasis 2, 3. CAFs regulate these processes through secretion of soluble factors and modulation of immune cell infiltration, and they also inhibit chemotherapy efficiency 4.

p38 MAPK signaling is ubiquitous in normal and malignant cells and is activated in various cancer types 5, 6. Although scientists agree that p38 signaling plays an important role in many cell processes related to cancer development and metastasis 6, 7, the effect of p38 signaling is still heavily debated8. Some studies have shown that the p38 MAPK pathway functions as a tumor suppressor by regulating tumor cell proliferation and transformation 9, whereas others have reported that p38 MAPK activation contributes to tumorigenesis 5, 10. Regardless, how activation of p38 signaling in tumor cells affects tumor metastasis remains unknown.

Tumor secretion of cytokines is key in regulating tumorigenesis and metastasis. IL-6 is secreted by both tumor and immune cells and is involved in tumorigenesis and metastasis through several mechanisms 11, 12. IL-6-induced Stat3 activation has been well characterized in tumorigenesis and metastasis in many types of cancers 13–15.

In this study, we investigated the function of p38 MAPK signaling in breast cancer metastasis. Because p38 is activated in breast cancer cells, we established breast cancer murine (4T1 and EMT6) cell lines with p38 stably knocked down using lentiviral shRNA knockdown and tumor-inoculated mice. We found that p38 signaling activation in breast cancer cells inhibited tumor metastasis. Further investigation showed that p38 signaling activated NF-κB p65, which induced miR-365 repression of IL-6 secretion and inhibited SDF1-CXCR4-mediated mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) migration into metastatic tumors and differentiation into CAFs. In a human breast cancer panel, p38 activation was inversely associated with IL-6 and vimentin expression and tumor progression.

Materials and Methods

Tumor cell culture

Murine 4T1 and EMT6 breast cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). These cells were stably transfected with luciferase vector (Promega, Madison, WI) for in vivo monitoring of tumor growth.

Murine breast cancer models

All animal experiments complied with protocols approved by IACUC committees at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Cleveland Clinic. For the mouse breast cancer model, 4T1 or EMT6 cells were subcutaneously (1 × 105), intravenously (2 × 104), or orthotopically (5 × 103) injected into the lower abdominal fat pad in 6- to 8-week-old Balb/c mice. Primary tumors and metastases were monitored by assessing tumor volume and luciferase activity with an in vivo imaging system (IVIS, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). 150 mg/kg luciferin (Promega, Madison, WI) was administered into mice via intraperitoneal injection. After 15 minutes, the tumor photon flux value was collected with an exposure time of 30 seconds using IVIS imaging system (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). In some experiments, the primary tumor was surgically removed, and tumor metastasis was monitored. For the IL-6 neutralization study, 100 μg IL-6 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was intravenously administered every 3 days after tumor inoculation. For the MSC migration inhibition assay, 150 μg AMD3100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was injected subcutaneously every other day during tumor development into the area surrounding the fat pad where tumor cells had been inoculated 16. Primary tumor and metastasis development was evaluated by assessing tumor volume, lung weight, or H&E staining.

Cancer cell adhesion, invasion, and migration assays

Cancer cell adhesion, invasion, and migration assays were performed as described previously 17. For the adhesion assay, 24-well plates were coated with 10 μg/mL of fibronectin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 24 hr at 4°C. After washing with PBS, 1 × 104 tumor cells were plated for 30 min. The adherent cells were counted after washing 3 times with PBS. For the tumor cell invasion assay, 8-μm transwell plate inserts were coated with fibronectin overnight at 4°C. For the tumor cell migration assay, 8-μM transwell plate inserts were coated with matrigel medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 2 hrs at 37°C. 5 × 103 tumor cells then were plated onto the transwell plate inserts for 24 hr. Cells attached to the lower portion of the transwell were counted as migrating and invasive cells.

Cell proliferation and apoptosis assay

Cell proliferation was analyzed by determining BrdU incorporation. Cultured cells were treated with 10 μM BrdU (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 30 min or 16 hrs when the cells were in exponential growth. Cells were harvested and stained with BrdU-APC/7-AAD (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). To assess cell apoptosis, cells in the exponential growth state were stained with annexin V/PI.

Western blotting

The primary antibodies used were p38/p-p38, vimentin, SOCS3, Twist1, sp1, and p-65/p-p65 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA), and detection was performed with an ECL Plus Western blotting detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA).

qRT-PCR

mRNA was prepared from tumor cells or tissues using a Qiagen RNAeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized using an ABI Biosystem cDNA synthesis kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Quantitative PCR was performed using an ABI7500 thermal cycler and SYBR Green fluorophore (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).

Immunohistochemistry staining

Paraffin-embedded mouse breast cancer tissue and human breast cancer tissue (US Biomax, Rockville, MD, USA) were processed with antigen retrieval, using pH 9.0 antigen retrieval buffer. The slides were blocked with 3% H2O2 and serum from the species of the secondary antibody. Slides were incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight. Slides were washed and then incubated with secondary antibody for 20 min at room temperature. After washing, slides were developed with DAB, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted for microscopy analysis.

Flow cytometry

Cells from tumor, spleen, lymph nodes, and lung were mechanically dissociated, and the red blood cells were removed with ACK lysis buffer (Lonza, Allendale, NJ). Cells were blocked with Fc antibody and then labeled with various antibody combinations (Lin/CD45/CD31, Lin/CD45/Sca-1/CD44, CD45/CD11b) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data were acquired with the BD LSRFortessa (Becton Dickinson) cell analyzer, and analysis was performed using Flowjo software. Cell sorting was performed using a Becton Dickinson cell sorter.

miRNA analysis

Total RNA, including miRNA from breast cancer cell lines and primary and metatstatic tumors, was extracted with a mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion, Grand Island, NY). We used a Mir-X™ miRNA first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Ambion, Grand Island, NY) to synthesize miRNA cDNA. SYBR-based qRT-PCR was used to quantify miR-let-7 and miR-365 (mmu-miR-365-3p). The 5′ primers used for amplification of miR-let-7 and miR-365 were 5′-taatgcccctaaaaatccttat-3′ and 5′-agggacttttgggggcagatgtg-3′. The 3′ primer mRQ was provided by the manufacturer in the cDNA synthesis kit. For miRNA quantification, we used Δ - ΔCt to quantify each miRNA relative to the amount of U6 snRNA.

ELISA and cytokine array

Analysis of cytokine and chemokine secretion from in vivo and in vitro samples was performed using ELISA kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and cytokine array kits (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA).

Oncomine and GEO/NCBI analysis

We used the Oncomine cancer microarray database and data mining platform (Life Technologies) and the NCBI GEO database to assess the differential expression of IL-6 and p38 MAPK levels in human breast cancer.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed Student t-test was used to compare experimental groups. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise indicated, all data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Results

p38 MAPK knockdown in breast cancer cells increases tumor cell invasion, migratory activity, and secretion of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 in vitro

Initially, we verified that p38 activation was present in the murine cell lines 4T1 and EMT6 (Supplemental Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure 2A). To explore the function of p38 activation in breast cancer development, p38 alpha was stably knocked down in 4T1 and EMT6 cells by using a lentiviral vector containing p38 shRNA (4T1-shp38, EMT6-shp38) and a GFP selection marker; control cell lines (4T1-shctl, EMT6-shctl) were established by stable transfection with a control lentiviral vector (Supplemental Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure 2A). Prior research has shown that p38 is important for cell proliferation 18. However, knocking down p38 in 4T1 and EMT6 cells did not significantly affect their proliferation or apoptosis in vitro (Supplemental Figure 1, B and C; Supplemental Figure 2, B and C).

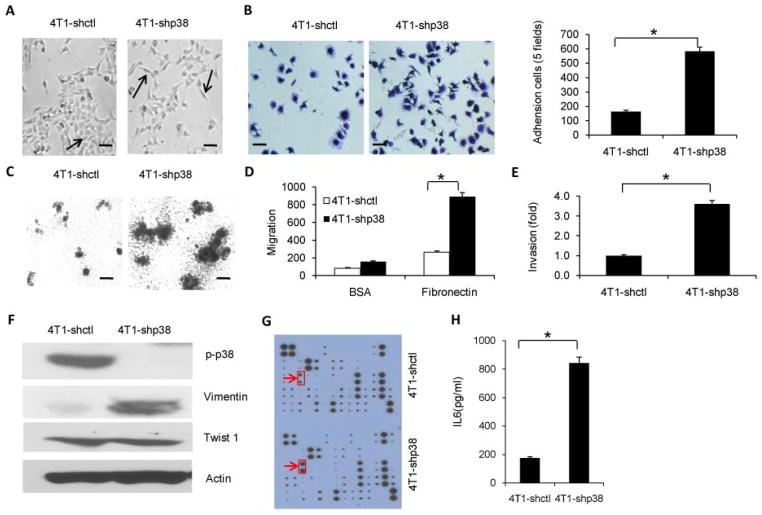

Next, we examined 4T1 cell invasion and migratory ability in vitro after p38 knockdown. Cultured 4T1-shp38 cells showed morphologic changes as compared with 4T1-shctl cells, including scattered distribution in culture and a spindle- or star-like morphology (Figure 1A; 14% in 4T1-shp38 group versus 2.5% in 4T1-shctl group, p < 0.05). Moreover, significantly more 4T1-shp38 cells attached to 24-well culture plates coated with a matrix protein such as fibronectin as compared with 4T1-shctl cells (Figure 1B). 4T1-shp38 cells grown in matrigel-coated plates formed larger colonies than did 4T1-shctl cells (Figure 1C). We also performed a transwell assay to examine cell migration and invasion potential and found that 4T1-shp38 cells migrated more efficiently than 4T1-shctl cells through transwell membranes coated with either fibronectin or matrigel (Figure 1, D and E). Similar results were obtained with EMT6 cells (Supplemental Figure 2, D – H). All these in vitro assays indicated that p38-knockdown breast cancer cells had a greater invasion and migratory capability than control cells. A potential mechanism behind this increased invasion and migration may be that p38 inhibits the ability of these cells to undergo the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), leading to increased metastasis upon p38 knockdown. Western blot analysis of EMT tumor cell markers 19–22 showed that vimentin expression increased after p38 knockdown when compared with 4T1-shctl cells but that expression of twist1, another regulator of the EMT process 23, was not affected (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. p38 inhibition in breast cancer cells increases invasion and migration activity and IL-6 secretion.

(A) Effect of p38α knockdown on 4T1 breast cancer cell morphology as shown with phase-contrast microscopy. The arrows point to cells with normal morphology (4T1-shctl) or a star-like or spindle morphology (4T1-shp38). (scale bar = 10 μm). (B) p38 knockdown increased the number of adherent cells. 4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 tumor cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated plates for 30 min, washed, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. (scale bar = 10 μm). (C) p38 knockdown enhanced the invasive phenotype as indicated by larger colony formation in 3D matrigel-coated plates (scale bar = 100 μm). (D) Migration capability of 4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 tumor cells was analyzed using a matrigel-coated trans-well system. (E) p38 knockdown increased breast cancer cell invasiveness as assessed by cell migration through the fibronectin-coated trans-well plate membrane. (F) Expression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition proteins after p38 knockdown, as analyzed by western blotting. (G) Cytokine array analysis of culture supernatant from p38 knockdown breast cancer cells and control cells. The arrows point to IL-6, the protein with the greatest change in expression between control and knockdown cells. (H) IL-6 secretion in supernatant from 4T1-shp38 cells was significantly greater than that from 4T1-shctl tumor cells as determined by ELISA. 1 × 106 cells were cultured for 48 hours. * p < 0.05.

A cytokine and chemokine array analysis of p38 knockdown 4T1 cell culture supernatant revealed a significant difference in the amount of secreted IL-6 (p < 0.05) between control and knockdown cells (Figure 1G, Supplemental Figure 3). Using ELISA, we confirmed this increase in IL-6 concentration (Figure 1H).

p38 MAPK knockdown in breast cancer cells promotes tumor metastasis

To further investigate whether p38 knockdown in breast cancer cells affects tumorigenesis, we subcutaneously inoculated 4T1-shp38 and 4T1-shctl cells into Balb/c mice to monitor tumor growth in vivo. The primary p38 knockdown tumors grew slightly faster than control tumors (Supplemental Figure 1D).

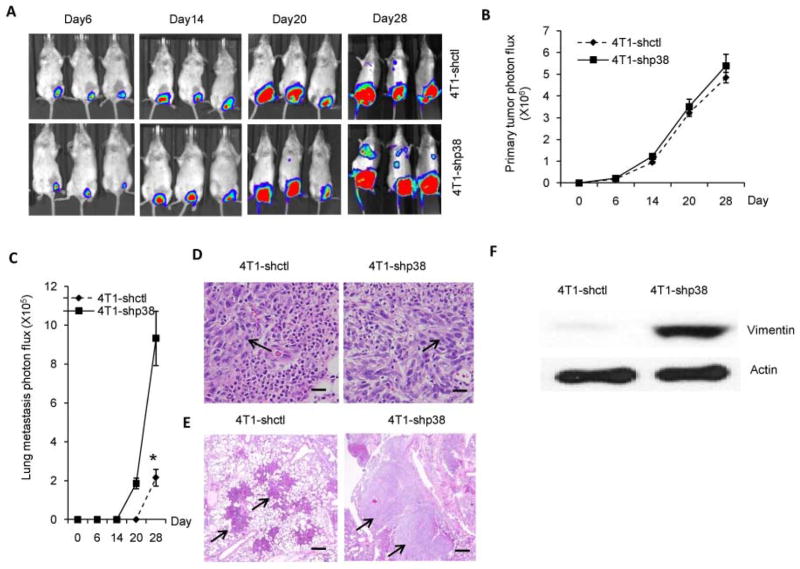

Breast cancer not only has a high metastatic potential, but metastasis often occurs at distant organs, such as the lungs or bones. 4T1-shp38 and 4T1-shctl tumor cells stably transfected with luciferase vector were intravenously inoculated into Balb/c mice. In vivo bioluminescence measurement revealed that the lung metastasis burden was similar between 4T1-shp38- and 4T1-shctl- inoculated mice (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B, p = 0.39). Because inoculation bypasses the invasion and extravasation stages of the metastatic process 24, we also orthotopically inoculated luciferase-transfected 4T1-shp38 and 4T1-shctl tumor cells into the mammary glands of Balb/c mice. Luciferase imaging showed that the primary tumor volume did not differ between the two groups (Figure 2, A and B). However, in animals inoculated with 4T1-shp38 tumor cells, metastasis occurred earlier and the metastatic mass was greater (Figure 2, A and C). H&E staining of primary and metastatic tumors showed that tumor cells were elongated in 4T1-shp38-inoculated mice compared to tumor cells in 4T1-shctl mice (Figure 2D), and 4T1-shp38 metastatic (lung) tumors were larger than those from 4T1-shctl mice (Figure 2E). Western blot assay of primary tumors demonstrated that 4T1-shp38 tumors had increased vimentin expression (Figure 2F). Surgical removal of primary tumor at 2 weeks after tumor inoculation 16 did not prevent lung metastasis in 4T1-shp38-inoculated mice (Supplemental Figure 5). Similarly in the EMT6 model, orthotopic inoculation of EMT6-shp38 did not affect primary tumor growth (Supplemental Figure 6A), but promoted lung metastasis (Supplemental Figure 6, B–D).

Figure 2. p38 knockdown in breast cancer cells promotes tumor metastasis.

4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 cells were orthotopically (5 × 103/mouse) inoculated into 6- to 8-week-old Balb/c mice (n = 5 to 7). The primary tumor (A and B) and metastatic tumors (A, C) were analyzed by in vivo imaging of luciferase intensity. H&E staining of primary tumors (D), showed an elongated cell morphology with p38 knockdown (scale bar = 10 μm). (E) H&E staining of metastatic tumor from orthotopically inoculated mice showed that p38 knockdown increased metastatic tumor cell size (scale bar = 20 μm). (F) Increased expression of the EMT marker, vimentin, was detected by western blotting in primary 4T1-shp38 tumor. * p < 0.05.

p38 MAPK signaling knockdown in breast cancer cells promotes tumor-associated fibroblast accumulation in tumor stromal tissue

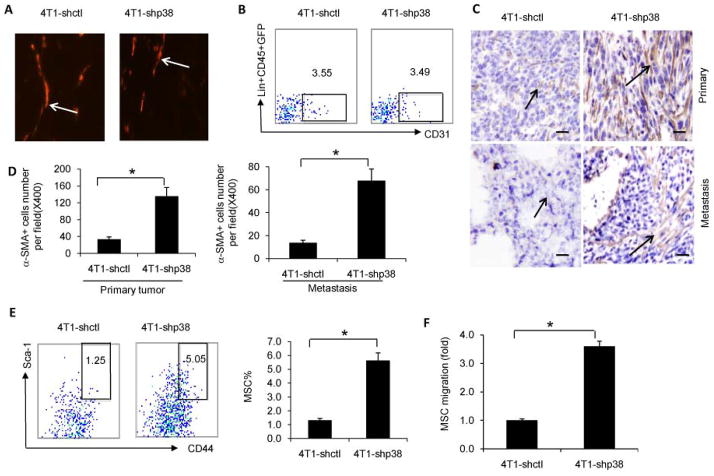

Tumor metastasis develops from interactions between tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment, leading to events that support tumor growth such as angiogenesis, stromal cell development, and CD11b MDSC expansion. We analyzed angiogenesis after p38 knockdown in 4T1 cells. Immunofluorescence staining of primary tumor for CD31 expression, an angiogenesis marker, showed that CD31 expression was similar between 4T1-shp38 tumors and 4T1-shctl tumors (Figure 3A). Flow cytometry analysis showed the percentage of CD31 cells in 4T1-shp38 lung metastasis (3.6%) was similar to that from 4T1-shctl lung metastasis (3.5%) (Figure 3B). These results suggest that p38 inhibition in breast cancer cells does not affect tumor angiogenesis. Tumor stromal cells are another component of the tumor environment and include MSCs and derived CAFs. Immunohistochemical staining for αSMA+ CAFs in 4T1-shp38 or EMT6-shp38 and 4T1-shctl or EMT6-shctl primary tumor and lung metastasis showed greater αSMA+ CAF accumulation in p38-knockdown primary and metastatic tumor than in control tumor (Figure 3, C, and D; Supplemental Figure 4E). Flow cytometry analysis of MSCs in lung metastasis revealed that 4T1-shp38 metastasis had more Lin−CD45−GFP−Scal+CD44+ MSCs than did 4T1-shctl lung metastasis (5.1% vs 1.3%, respectively; Figure 3E). We also found that bone marrow-derived MSC migration was greater toward 4T1-shp38 culture supernatant than toward supernatant from 4T1-shctl cells (Figure 3F).

Figure 3. p38 signaling knockdown in breast cancer cells increases cancer-associated fibroblast accumulation.

(A) Immunoflourescence staining for angiogenesis (CD31) was similar in primary 4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 tumors after orthotopic inoculation. (B) Flow cytometry analysis showed that the percentage of Lin-CD45−GFP−CD31+ cells was similar between 4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 metastatic tumors. (C and D) αSMA immunochemistry staining showed greater cancer-associated fibroblast accumulation (arrows) in primary and metastatic 4T1-shp38 tumors compared to 4T1-shctl tumors (scale bar = 10 μm). (E) Flow cytometry analysis of Lin−CD45−GFP−Sca-1+CD44+ mesenchymal stem cells in metastatic 4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 tumors. (F) Comparison of mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell migration to 4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 tumor cell culture supernatant. * p < 0.05.

p38 MAPK signaling knockdown promotes IL-6 secretion in the breast cancer tumor environment by modulating miR-365 activity

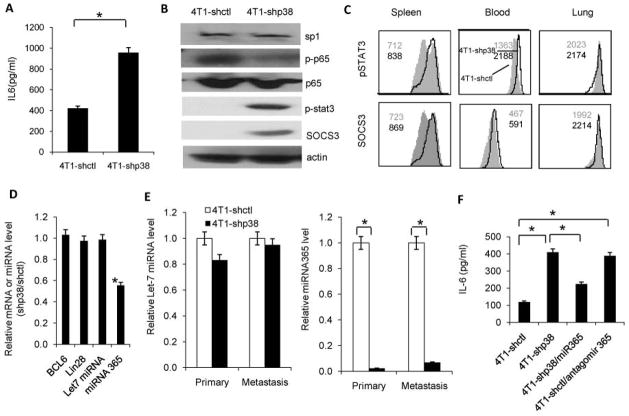

As the increase in IL-6 concentration was greatest among the cytokines measured in 4T1 cells after p38 knockdown in vitro (Figure 1G), we hypothesized that the molecular effectors responsible for p38 signaling in breast cancer metastasis and stromal expansion could be extracellular molecules detectable in p38 knockdown breast cancer cell culture supernatant. We found that IL-6 concentration was also increased in the lysate of lung metastases of 4T1-shp38 tumors in Balb/c mice (Figure 4A). We hypothesized that p38 MAPK might inhibit IL-6 signaling in breast cancer metastasis. IL-6 signaling activation induces Stat3 phosphorylation and regulates downstream targets. p38 inhibition in breast cancer cells induced IL-6 secretion, which allowed autocrine activation of Stat3 and SOCS3 expression (Figure 4B). Also, Stat3 activation and SOCS3 expression were elevated in CD11b myeloid cells from the spleen, blood, and lung of 4T1-shp38 tumor-bearing mice as compared with 4T1-shctl mice (Figure 4C). These results demonstrated that p38 control of IL-6 secretion in breast cancer cells regulates metastasis and may be partially due to signaling to CD11b myeloid cells.

Figure 4. p38 activation in breast cancer cells inhibits IL-6 secretion via p65-mediated miR-365 regulation.

(A) IL-6 concentration was significantly greater in 4T1-shp38 compared with 4T1-shctl metastatic lysate. (B) Western blot analysis revealed that STAT3 and SOCS3 expression increased in p38 knockdown cells whereas phosphorylated p65 decreased. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of STAT3 activation and SOCS3 expression in CD11b cells in metastatic 4T1-shp38 and 4T1-shctl tumors revealed that p38 knockdown increased IL-6 signaling to CD11b cells. (D) qRT-PCR detection of BCL6, Lin28 mRNA, let-7 miRNA, and miRNA 365 in p38 knockdown cells. (E) qRT-PCR analysis of microRNA let-7 and miRNA 365 in primary and metastatic p38 knockdown cells. (F) IL-6 secretion detected by ELISA in culture supernatant from 4T1-shctl and 4T1-shp38 breast cancer cells with ectopic knock in of miR-365 or the miRNA-365 antagonist, antagomir 365. Antagonism of miRNA-365 increased IL-6 secretion.* p < 0.05.

Next, we investigated how p38 signaling in breast cancer cells regulated IL-6 secretion. Microarray analysis suggested that C/EBP, BCL-6, Lin 28, miR-Let7, and miR-365 might be the potential factors. However, qRT-PCR indicated that inhibiting p38 signaling in 4T1 cells did not affect BCL6, Lin28, or Let-7 miRNA expression levels but did reduce miR-365 expression (Figure 4D). To confirm this finding, we analyzed these regulators in primary and metastatic tumors. p38 signaling inhibition did not change BCL6 and Lin28 and Let-7 miRNA expression in either primary or metastatic tissue but significantly inhibited miR-365 activity in both tissues (p < 0.05; Figure 4E and Supplemental Figure 7). Through ectopic knock-in of miR-365 in 4T1-shp38 cells, we confirmed that miR-365 regulated IL-6 secretion in breast cancer cells after p38 knockdown. Decreased IL-6 secretion was detected after knock-in (Figure 4F). Furthermore in 4T1-shctl cells, overexpression of antagomir 365, a miR-365 inhibitor, increased IL-6 secretion (Figure 4F). All these data indicate that miR-365 is critical in p38 regulation of IL-6 secretion in breast cancer.

We postulated that sp1 and NF-κB p65, two transcription factors downstream of p38 signaling, were regulated by miR-365 to control IL-6 secretion. NF-κB could also directly bind to the IL-6 promoter and induce IL-6 transcription 25 or cooperate with other transcription factors such as Stat3 to induce IL-6 secretion, as has been shown in starved cancer cells 26. However, NF-kB activation can also increase Let-7 miRNA, suppressing IL-6 secretion; thus, considering the cellular context of NF-kB activation is extremely important27. In breast cancer cells, p38 knockdown did not affect sp1 expression but reduced p65 phosphorylation (Figure 4B). These results prove that p38 activation in breast cancer cells may activate NF-κB to regulate IL-6 secretion through micro RNA mechanism28.

As p38-knockdown had increased expression of vimentin, which is involved in the EMT, we investigated whether IL-6 was related to this increased expression. After knockdown of Stat3, the key component in IL-6 signaling, vimentin expression was reduced in 4T1-shp38 cells (Supplemental Figure 8).

SDF1-CXCR4 signaling is involved in IL-6 mediated migration of MSCs to metastatic sites

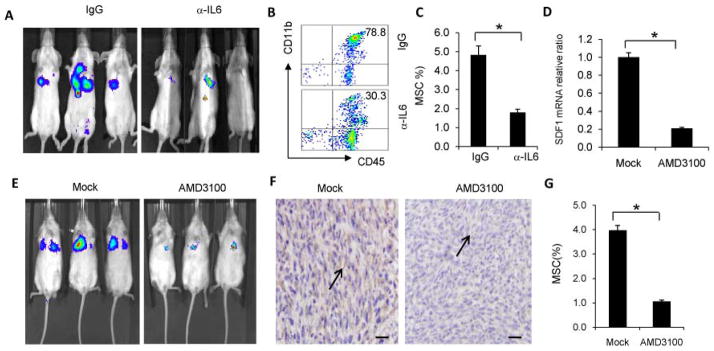

To confirm that IL-6 signaling is important for p38 regulation of stromal expansion in breast cancer metastasis, an IL-6 neutralization antibody was administered intravenously to Balb/c mice after 4T1-shp38 tumor cell inoculation into the abdominal fat-pad. The primary tumor was removed 2 weeks after inoculation. Neutralization of IL-6 inhibited tumor metastasis to lung (Figure 5A), and not only reduced CD11b cell accumulation at metastasis sites (Figure 5B), but also decreased MSC infiltration (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. IL-6 and SDF1/CXCR4 signaling in MSC migration are involved in stromal tissue expansion.

(A) Primary tumors were surgically removed from Balb/c mice 2 weeks after orthotopic inoculation of 4T1-shp38 cells that was followed by injection of IL-6 antibody every 3 days after tumor inoculation. Metastatic tumors in the lungs were monitored by in vivo imaging. CD11b myeloid cell (B) and Lin−Sca-l+CD45−GFP−CD44+ MSC (C) in the lung were analyzed by FACS, revealing that neutralization of IL-6 abrogated CD11b cell and MSC infiltration in metastatic lung. (D–G) The experiment shown here was performed as in A–C, except the inhibitory treatment was the CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling disrupter AMD3100 instead of IL-6 antibody. The control treatment was PBS. SDF1 mRNA in the metastasis lung was analyzed by qRT-PCR (D), and tumor metastasis was monitored by in vivo imaging (E). Immunochemistry staining of α-SMA+ stromal cells in metastatic tumor (F) showed that blocking CXCR4-CXCL12 inhibited stromal cell expansion in metastatic sites (arrows) (scale bar = 10 μm). Flow cytometry analysis showed MSC infiltration into metastatic tumors was inhibited when CXCR4-CXCL12 was blocked (G). * p < 0.05.

Chemokines are a family of small cytokines that mediate numerous cellular functions, such as recruiting immune cells to sites of injury, by driving cellular migration. SDF1 is a member of the of CXC chemokine subfamily and interacts with the seven-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor CXCR4. SDF1-CXCR4 signaling is not only important in maintaining homeostasis for cells, eg, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and MSCs so as to maintain stemness during quiescence before differentiation 29, but also in regulating secretion of cytokines, such as IL-6, in the tumor microenvironment 30, 31. We hypothesized that during breast cancer metastasis, the metastatic environment increases cellular secretion of SDF1, which can induce MSC migration to metastatic sites, leading to MSC differentiation into tumor stromal cells. Specifically disrupting CXC4-CXCL12 signaling with AMD3100 32, 33 significantly reduced SDF1 expression at metastatic sites (Figure 5D), inhibited 4T1-shp38 tumor metastasis (Figure 5E), and decreased αSMA+ stromal cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment (Figure 5F). The percentage of MSCs also decreased at metastatic sites after AMD3100 administration (Figure 5G). Our results showed that disruption of CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling during primary tumor development can inhibit both MSC and stromal cell migration to metastatic sites.

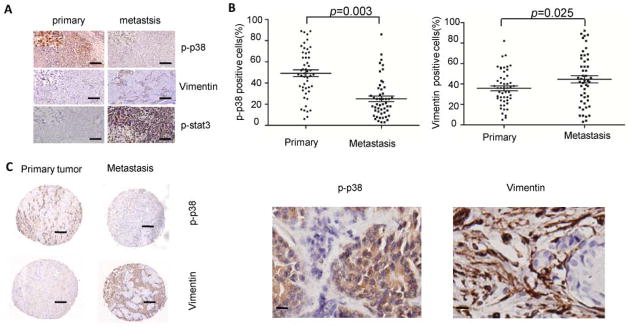

p38 signaling is negatively correlated with vimentin expression in human breast cancer metastasis

Our data showed that p38 knockdown in inoculated breast cancer cells increased tumor metastasis by enhancing tumor stromal expansion; thus, we wanted to explore whether the phosphorylation status of p38 corresponds to vimentin expression in human samples of primary and metastatic breast cancer. p38 activation in human metastatic breast cancers was negatively associated with vimentin expression and Stat3 activation (Figure 6A). The percentage of cells in which p38 was phosphorylated was greater in human primary tumors than in metastatic tumors (48.6% ± 1.4% vs 22.7% ± 2.6%, respectively), whereas vimentin expression in human metastatic tumors was higher than in primary tumors (36.1% ± 1.1% vs 44.7% ± 2.0%, respectively; Figure 6, B and C). To confirm these IL-6 and p38 mRNA differential expression patterns in human breast cancer, we utilized the Oncomine database 34 and found IL-6 and p38 expression to be inversely correlated (Supplemental Figure 9). Further statistical analysis of human breast cancer showed that p38 and IL-6 are differentially expressed in various subtypes of breast cancer and negatively correlated (Supplemental Figure 10). Based on these data, we propose that p38 is initially activated in primary tumorigenesis, but during metastasis, p38 activation is decreased, leading to induction of IL-6 secretion to promote MSC migration to sites where MSCs differentiate into CAFs and promote metastasis.

Figure 6. p38 signaling is inversely associated with tumor stromal tissue expansion in human primary and metastatic tumors, but is associated with decreased IL-6 and STAT3 signaling in human primary and metastatic breast cancer. (A).

Immunohistochemistry staining for p-p38, vimentin and p-Stat3 expression in primary and metastatic human breast cancer tissue (scale bar = 20 μm). (B–C) The relationship between p-p38 and vimentin in human primary and metastatic breast cancer was anlayzed on paired human primary and metastasis in a breast cancer tissue array (n = 50). * p < 0.05 (scale bar, left column = 20 μm, right column= 10μm).

Discussion

In this study, we discovered that p38 signaling activation in breast cancer cells negatively regulates tumor metastasis. In vivo, p38 knockdown in breast cancer cells not only significantly increased tumor cell invasion and metastatic activity by upregulating expression of the EMT protein, vimentin, but also increased tumor metastasis by increasing tumor stromal tissue expansion. p38 activation suppressed IL-6 secretion through modifying NF-κB p65 activation to enhance miR-365 inhibition of IL-6 transcription, leading to SDF1-CXCR4 signaling that mediated MSC migration to metastatic sites, where the cells can differentiate into CAFs 33.

Tumorigenesis is a complicated process that involves several different signal transduction pathways, including the STAT3, p53, and p38 MAPK pathways. The function of STAT3 and p53 in tumor development has been well characterized; however, how p38 signaling affects tumorigenesis and metastasis has remained unclear. p38 signaling can directly affect tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis, but we did not see these effects in breast cancer development. What was surprising was that p38 knockdown in breast cancer cells only modestly increased tumor cell proliferation and primary tumor growth but significantly increased stromal expansion, as assessed by αSMA+ expression, in primary and metastatic tumors.

In this study, we found that p38 signaling regulates IL-6 signaling during tumor metastasis. In some tumors, such as mantle cell lymphoma and myeloma, IL-6 secretion is modest, but its signaling is critical for tumor cell survival and development of chemotherapeutic resistance 35, 36. IL-6 expression in tumor cells can be regulated by conventional transcription factors, such as C/EBP, or microRNAs, such as miR-Let-7 37, 38. IL-6 is also reported to be regulated by miR-365 in HEK293 cells 28. We found that in breast cancer tumor development, miR-365, but not miR-Let-7, regulates IL-6 secretion. On the other hand, miRNA regulation of tumor metastasis occurs through various mechanisms, such as direct regulation of the tumor cell EMT process 39, or modulation of cytokine secretion to indirectly affect tumor metastasis 40.

Tumor stromal cells can arise from MSCs. SDF1-CXCR4 signaling is key in regulating normal HSC and MSC homeostasis but recently has been shown to regulate migration of MSCs from bone marrow or tissue to sites of metastasis 33. Blocking SDF1-CXCR4 signaling could inhibit MSC migration to tumors or metastatic sites to suppress tumor development 16. AMD3100 (plerixafor) is a CXCR4 antagonist that is used to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation in cancer patients. Although some adverse effects are reported, such as nausea, diarrhea, and some teratogenic effects, it is widely used in stem cell transplantation in cancer patients in conjunction with G-CSF 41.Other cytokines in the tumor environment, such as TNF-α, could also direct MSC migration to tumor sites to promote tumor development 42.

In conclusion, we found that p38 signaling activation in breast cancer cells has an important role in repressing tumor metastasis. However, p38 activation is also associated with human breast cancer metastasis through increased miR-365 inhibition of IL-6 transcription. Our study also suggests that analysis of IL-6 levels combined with analysis of p38 phosphorylation status might provide valuable insight in guiding treatment of primary and metastatic breast cancers. Serum IL-6 levels in breast cancer patients have been reported to correlate with metastatic disease prognosis43, 44. Combined detection of p38 activation in the primary and/or metastatic tumor site with serum/primary tumor IL-6 levels could provide valuable prognostic information for patients with breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and impact.

p38 MAPK signaling is upregulated in breast cancer and is important for metastasis. Abolishing p38 signaling in murine breast cancer cells promoted tumor metastasis through stromal expansion controlled by miRNA-365 mediated IL-6 signaling. In human primary and metastatic breast cancer tumors, p38 activation was inversely correlated with IL-6 and vimentin expression. This study suggests that p38 MAPK and IL-6 could be prognostic indicators as well as potential therapeutic targets in metastatic breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by start-up operating funds from the Cleveland Clinic, grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA138402, R01CA138398, R01CA163881, and P50CA142509), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation, and the Betsy B. de Windt Endowment for Cancer Research.

Abbreviations

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- CAF

cancer-associated fibroblasts

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- miR-365

microRNA 365

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressive cell

- SDF1

stromal cell-derived factor 1

- CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chakrabarti R, Hwang J, Andres Blanco M, Wei Y, Lukacisin M, Romano RA, Smalley K, Liu S, Yang Q, Ibrahim T, Mercatali L, Amadori D, et al. Elf5 inhibits the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mammary gland development and breast cancer metastasis by transcriptionally repressing Snail2. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1212–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, Gonda T, Wang SS, Takashi S, Baik GH, Shibata W, Diprete B, Betz KS, Friedman R, Varro A, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang XH, Jin X, Malladi S, Zou Y, Wen YH, Brogi E, Smid M, Foekens JA, Massague J. Selection of bone metastasis seeds by mesenchymal signals in the primary tumor stroma. Cell. 2013;154:1060–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg AK, Basu S, Hu J, Yie TA, Tchou-Wong KM, Rom WN, Lee TC. Selective p38 activation in human non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:558–64. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J, He J, Wang J, Cao Y, Ling J, Qian J, Lu Y, Li H, Zheng Y, Lan Y, Hong S, Matthews J, et al. Constitutive activation of p38 MAPK in tumor cells contributes to osteolytic bone lesions in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2012;26:2114–23. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He J, Liu Z, Zheng Y, Qian J, Li H, Lu Y, Xu J, Hong B, Zhang M, Lin P, Cai Z, Orlowski RZ, et al. p38 MAPK in myeloma cells regulates osteoclast and osteoblast activity and induces bone destruction. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6393–402. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:537–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loesch M, Chen G. The p38 MAPK stress pathway as a tumor suppressor or more? Front Biosci. 2008;13:3581–93. doi: 10.2741/2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng F, Zhang H, Liu G, Kreike B, Chen W, Sethi S, Miller FR, Wu G. p38gamma mitogen-activated protein kinase contributes to oncogenic properties maintenance and resistance to poly (ADP-ribose)-polymerase-1 inhibition in breast cancer. Neoplasia. 2011;13:472–82. doi: 10.1593/neo.101748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesina M, Kurkowski MU, Ludes K, Rose-John S, Treiber M, Kloppel G, Yoshimura A, Reindl W, Sipos B, Akira S, Schmid RM, Algul H. Stat3/Socs3 activation by IL-6 transsignaling promotes progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:456–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynaud D, Pietras E, Barry-Holson K, Mir A, Binnewies M, Jeanne M, Sala-Torra O, Radich JP, Passegue E. IL-6 controls leukemic multipotent progenitor cell fate and contributes to chronic myelogenous leukemia development. Cancer Cell. 20:661–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng J, Liu Y, Lee H, Herrmann A, Zhang W, Zhang C, Shen S, Priceman SJ, Kujawski M, Pal SK, Raubitschek A, Hoon DS, et al. S1PR1-STAT3 signaling is crucial for myeloid cell colonization at future metastatic sites. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:642–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Deng J, Kujawski M, Yang C, Liu Y, Herrmann A, Kortylewski M, Horne D, Somlo G, Forman S, Jove R, Yu H. STAT3-induced S1PR1 expression is crucial for persistent STAT3 activation in tumors. Nat Med. 2010;16:1421–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H, Herrmann A, Deng JH, Kujawski M, Niu G, Li Z, Forman S, Jove R, Pardoll DM, Yu H. Persistently activated Stat3 maintains constitutive NF-kappaB activity in tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Yang P, Sun T, Li D, Xu X, Rui Y, Li C, Chong M, Ibrahim T, Mercatali L, Amadori D, Lu X, et al. miR-126 and miR-126* repress recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells and inflammatory monocytes to inhibit breast cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:284–94. doi: 10.1038/ncb2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H, Radisky DC, Yang D, Xu R, Radisky ES, Bissell MJ, Bishop JM. MYC suppresses cancer metastasis by direct transcriptional silencing of alphav and beta3 integrin subunits. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:567–74. doi: 10.1038/ncb2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulavin DV, Fornace AJ., Jr p38 MAP kinase’s emerging role as a tumor suppressor. Adv Cancer Res. 2004;92:95–118. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)92005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai J, Guan H, Fang L, Yang Y, Zhu X, Yuan J, Wu J, Li M. MicroRNA-374a activates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling to promote breast cancer metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:566–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI65871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kokkinos MI, Wafai R, Wong MK, Newgreen DF, Thompson EW, Waltham M. Vimentin and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human breast cancer--observations in vitro and in vivo. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:191–203. doi: 10.1159/000101320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendez MG, Kojima S, Goldman RD. Vimentin induces changes in cell shape, motility, and adhesion during the epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Faseb J. 2010;24:1838–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-151639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vuoriluoto K, Haugen H, Kiviluoto S, Mpindi JP, Nevo J, Gjerdrum C, Tiron C, Lorens JB, Ivaska J. Vimentin regulates EMT induction by Slug and oncogenic H-Ras and migration by governing Axl expression in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:1436–48. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckert MA, Lwin TM, Chang AT, Kim J, Danis E, Ohno-Machado L, Yang J. Twist1-induced invadopodia formation promotes tumor metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:372–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf MJ, Hoos A, Bauer J, Boettcher S, Knust M, Weber A, Simonavicius N, Schneider C, Lang M, Sturzl M, Croner RS, Konrad A, et al. Endothelial CCR2 signaling induced by colon carcinoma cells enables extravasation via the JAK2-Stat5 and p38MAPK pathway. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Libermann TA, Baltimore D. Activation of interleukin-6 gene expression through the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2327–34. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon S, Woo SU, Kang JH, Kim K, Shin HJ, Gwak HS, Park S, Chwae YJ. NF-kappaB and STAT3 cooperatively induce IL6 in starved cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:3467–81. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garzon R, Pichiorri F, Palumbo T, Visentini M, Aqeilan R, Cimmino A, Wang H, Sun H, Volinia S, Alder H, Calin GA, Liu CG, et al. MicroRNA gene expression during retinoic acid-induced differentiation of human acute promyelocytic leukemia. Oncogene. 2007;26:4148–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Z, Xiao SB, Xu P, Xie Q, Cao L, Wang D, Luo R, Zhong Y, Chen HC, Fang LR. miR-365, a novel negative regulator of interleukin-6 gene expression, is cooperatively regulated by Sp1 and NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21401–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma’ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–34. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang CH, Chuang JY, Fong YC, Maa MC, Way TD, Hung CH. Bone-derived SDF-1 stimulates IL-6 release via CXCR4, ERK and NF-kappaB pathways and promotes osteoclastogenesis in human oral cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1483–92. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Sun Y, Song W, Nor JE, Wang CY, Taichman RS. Diverse signaling pathways through the SDF-1/CXCR4 chemokine axis in prostate cancer cell lines leads to altered patterns of cytokine secretion and angiogenesis. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1578–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, Carey VJ, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, Gonda T, Wang SS, Takashi S, Baik GH, Shibata W, Diprete B, Betz KS, Friedman R, Varro A, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen D, Sun Y, Wei Y, Zhang P, Rezaeian AH, Teruya-Feldstein J, Gupta S, Liang H, Lin HK, Hung MC, Ma L. LIFR is a breast cancer metastasis suppressor upstream of the Hippo-YAP pathway and a prognostic marker. Nat Med. 2012;18:1511–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Yang J, Qian J, Li H, Romaguera JE, Kwak LW, Wang M, Yi Q. Role of the microenvironment in mantle cell lymphoma: IL-6 is an important survival factor for the tumor cells. Blood. 2012;120:3783–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Zaanen HC, Koopmans RP, Aarden LA, Rensink HJ, Stouthard JM, Warnaar SO, Lokhorst HM, van Oers MH. Endogenous interleukin 6 production in multiple myeloma patients treated with chimeric monoclonal anti-IL6 antibodies indicates the existence of a positive feed-back loop. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1441–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI118932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hungness ES, Luo GJ, Pritts TA, Sun X, Robb BW, Hershko D, Hasselgren PO. Transcription factors C/EBP-beta and -delta regulate IL-6 production in IL-1beta-stimulated human enterocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:64–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell. 2009;139:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tao ZH, Wan JL, Zeng LY, Xie L, Sun HC, Qin LX, Wang L, Zhou J, Ren ZG, Li YX, Fan J, Wu WZ. miR-612 suppresses the invasive-metastatic cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2013;210:789–803. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bockhorn J, Dalton R, Nwachukwu C, Huang S, Prat A, Yee K, Chang YF, Huo D, Wen Y, Swanson KE, Qiu T, Lu J, et al. MicroRNA-30c inhibits human breast tumour chemotherapy resistance by regulating TWF1 and IL-11. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1393. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plerixafor: AMD AMD3100, JM 3100, SDZ, SID. Drugs R D. 2007;8:113–9. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200708020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ren G, Zhao X, Wang Y, Zhang X, Chen X, Xu C, Yuan ZR, Roberts AI, Zhang L, Zheng B, Wen T, Han Y, et al. CCR2-dependent recruitment of macrophages by tumor-educated mesenchymal stromal cells promotes tumor development and is mimicked by TNFalpha. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:812–24. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sansone P, Storci G, Tavolari S, Guarnieri T, Giovannini C, Taffurelli M, Ceccarelli C, Santini D, Paterini P, Marcu KB, Chieco P, Bonafe M. IL-6 triggers malignant features in mammospheres from human ductal breast carcinoma and normal mammary gland. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3988–4002. doi: 10.1172/JCI32533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang GJ, Adachi I. Serum interleukin-6 levels correlate to tumor progression and prognosis in metastatic breast carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:1427–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.